Agilent Technologies: From HP's Instruments Division to Life Sciences Leader

I. Introduction & Episode Setup

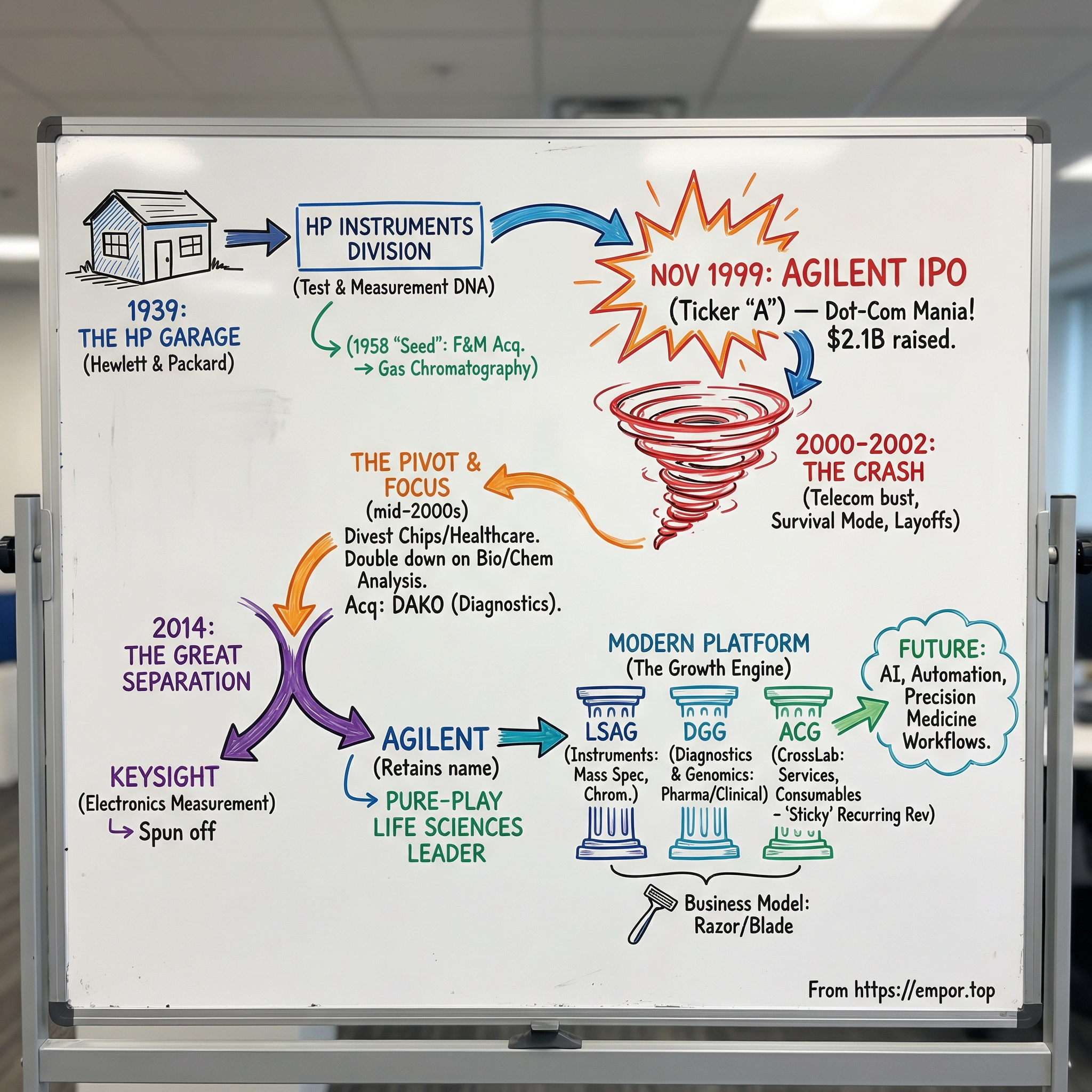

Picture the morning of November 18, 1999. Nasdaq is humming with that late-’90s kind of adrenaline—the sort reserved for companies everyone wants a piece of. At the opening bell, 65 million shares of a newly minted name, Agilent Technologies, hit the market at $30. Almost immediately, the price jumps into the low forties. By the close, Agilent has pulled in $2.1 billion, the biggest Silicon Valley IPO to that point.

But the real headline wasn’t just the cash raised or the day-one pop. It was what that ticker symbol represented: Hewlett-Packard, the legendary engineering company, carving out the business that looked most like its original self—the instruments, the measurement tools, the lab gear. In a sense, it was HP’s earliest DNA being spun into its own standalone organism.

Fast-forward to today, and Agilent is a roughly $6.5 billion revenue company with about 18,000 employees worldwide. Yet outside of labs and boardrooms, the name barely registers. That’s because Agilent isn’t on your desk or in your pocket. It’s in the places where modern science actually happens: pharmaceutical R&D labs, hospital pathology departments, food safety facilities, and environmental testing stations. Agilent sells the picks and shovels behind the breakthroughs—and behind the regulations that keep water clean and food safe.

So here’s the question that makes this story worth telling: how did a company born out of HP’s test-and-measurement heritage—the oscilloscopes and signal analyzers that helped build the telecom era—become a life sciences and diagnostics leader, tied to cancer testing, genomics, and drug development?

To get there, Agilent had to survive the dot-com crash, make brutal cuts, sell off beloved businesses, and—most importantly—walk away from what many people thought the company was. Along the way came not one, but two major separations, plus a steady drumbeat of acquisitions and divestitures that rewired the portfolio from the inside out.

At its core, this is a story about focus. About the courage to let go of the past—and the discipline to build a future that doesn’t look like the company you started with.

II. The HP Legacy: Origins & DNA (1939-1999)

The Garage and the Oscillator

In 1938, two Stanford electrical engineering graduates—William Hewlett and David Packard—scraped together $538 in working capital and started building products in a one-car garage at 367 Addison Avenue in Palo Alto.

Their first hit was an audio oscillator, a device that generates precise electronic tones for testing. They called it the Model 200A and priced it at $54.40, a number chosen to sound exacting and “engineer-approved.” The first marquee customer was Walt Disney Studios, which bought eight units to help tune the sound system for Fantasia.

But the bigger thing taking shape in that garage wasn’t just a box of circuits. Hewlett and Packard were building a way of running a company—later dubbed “The HP Way”—rooted in respect for engineers, openness, and giving employees real autonomy. This was decades before anyone would call the region Silicon Valley. Still, the culture they created would echo through the valley that formed around them.

On January 1, 1939, they made it official. A coin flip decided whose name came first; Hewlett won. Hewlett-Packard was born. From there, the company grew through World War II contracts and then expanded into oscilloscopes, signal generators, and an increasingly deep catalog of test-and-measurement gear.

Building the Instruments Empire

By the 1950s, HP had become the name in electronic test and measurement. But Hewlett and Packard didn’t want to be locked into a single market forever. In 1958, HP made its first major acquisition: F&M Scientific Corporation, a small Pennsylvania company that built gas chromatographs—machines that separate chemical mixtures so you can identify what’s inside and how much of it is there.

At the time, it may have looked like a side quest. In hindsight, it was the seed of what would eventually become Agilent’s life sciences engine.

The logic wasn’t a leap for HP. A gas chromatograph is, in many ways, a measurement instrument wearing a lab coat. It depends on precision, reliable detection, careful signal processing, and the ability to turn messy real-world data into clean, trusted results—exactly the kinds of problems HP had already learned to love in electronics.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, HP kept widening the aperture. It added mass spectrometers, which identify molecules by their mass-to-charge ratio, and liquid chromatography systems. Separately, HP’s medical products business—built from acquisitions in the 1950s—became the company’s second-oldest division. By the 1980s, HP’s instruments business was a huge operation generating billions in revenue, even if it often lived in the shadow of the company’s computing and printing giants.

The HP Way Under Pressure

For decades, the HP Way was a superpower. By the 1990s, it started to look like a constraint.

HP had become a true conglomerate: computers, printers, scientific instruments, medical devices, semiconductors, and electronic components. The same consensus-driven culture that once unlocked innovation now made it easier to stall. Meanwhile, smaller and more focused competitors were getting faster—across multiple markets at once.

Inside the test-and-measurement business, the pressure was especially intense. Telecom customers needed shorter development cycles as networks digitized. Semiconductor customers demanded more sophisticated equipment as chip geometries shrank. Medical customers needed deeper regulatory expertise. These weren’t adjacent markets anymore; they were increasingly specialized worlds with their own rules and tempos.

That reality pushed HP’s leadership toward a painful conclusion: the company might be too broad to compete at the pace its markets required. The strategic mismatch was hard to ignore. Computing and printing ran on consumer-like timelines and manufacturing economics. Instruments ran on research cycles, high-value engineering, and long relationships built on trust and accuracy. Keeping them bundled together also created what investors call a “conglomerate discount”—the market struggled to value the whole because the whole was too complicated.

By early 1999, HP decided to split in two, spinning out the instruments business as its own public company.

And here’s the twist that only becomes obvious later: even that wasn’t the final form. The instruments legacy would eventually need another separation. And the biggest value to emerge from HP’s measurement DNA wouldn’t be in electronics at all—it would be in the life sciences.

III. The Great Spin-Off: Creating Agilent (1999-2000)

The Announcement and the Name

On March 2, 1999, Hewlett-Packard stopped dancing around the rumors and made it official: it would spin out a big chunk of what made HP feel like, well, HP. Test and measurement. Semiconductors. Chemical analysis. Medical products. The “new HP” would keep computing, printing, and imaging—the businesses that dominated the headlines and most of the revenue.

That decision created an immediate, very human problem: what do you call the thing you’ve just created?

“HP” was one of the most valuable brands in technology, and it wasn’t coming along for the ride. The spin-off needed a name that could carry decades of credibility in precision instruments, but also feel modern—technical without being cold, serious without sounding like a defense contractor, and definitely not something people would mistake for a drug company.

After a branding process that reportedly churned through thousands of candidates, the answer arrived on July 28, 1999: Agilent Technologies. “Agile” signaled speed and adaptability. The “-ent” ending echoed the era’s tech naming conventions, like Lucent, and gave the word a clean, engineered snap. The logo—a kind of abstract starburst—aimed to suggest energy and invention.

HP tapped Ned Barnholt, a two-decade company veteran and leader of the test-and-measurement organization, to be president and CEO. His job wasn’t just to run a business. It was to manufacture identity—fast—while steering toward what would become one of the most closely watched IPOs of the bubble.

The Record-Breaking IPO

The calendar couldn’t have been kinder. Late 1999 was peak dot-com mania: valuations untethered, momentum everywhere, and investors eager to buy anything with a technology pedigree. In that environment, a newly independent HP offspring wasn’t just a story—it was catnip.

On November 18, 1999, Agilent began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under a single-letter ticker: “A.” The symbolism was obvious. The IPO priced at $30 a share, with 65 million shares sold. HP kept the rest—about 85%—with the plan to distribute those shares to HP shareholders the following year in a tax-free transaction.

Trading day felt like a victory lap. The stock climbed throughout the session and closed at $42.44, a 41% jump that valued Agilent at roughly $16 billion. The offering raised $2.1 billion, making it the largest Silicon Valley IPO at the time, topping the previous record holder, Palm Computing.

For Barnholt and his team, it was a clear signal: investors believed a focused instruments company could be worth more on its own than buried inside HP’s complexity. Now came the harder part—earning that confidence quarter after quarter.

Full Independence

On June 2, 2000, HP finished the job. It distributed its remaining Agilent shares to HP stockholders in a tax-free spin-off. Shareholders received about 0.36 shares of Agilent for each share of HP they owned. Agilent was now fully on its own—no longer sheltered by HP’s balance sheet, and no longer constrained by HP’s priorities.

And it launched into independence with a portfolio that looked broad, but—at least on paper—still hung together. Test and measurement was the anchor, selling into telecom, aerospace, and electronics manufacturing. The semiconductor products group supplied chips for communications and computing. Healthcare products covered patient monitoring and cardiac care. And chemical analysis—the lineage tracing back to HP’s F&M Scientific acquisition—served pharma, environmental, and food safety labs.

It was a strong starting lineup. But the world that had cheered Agilent onto the public markets was about to change. The same conditions that made the IPO feel effortless were about to flip—quickly, and painfully.

IV. The Dot-Com Crash & Survival Mode (2000-2005)

The Bubble Bursts

Nasdaq topped out on March 10, 2000—barely four months after Agilent’s IPO. Then the floor gave way. Over the next couple of years, the tech market unraveled, wiping out most of the value investors had just assigned to the “new economy.” Former icons of the boom—Cisco, Sun Microsystems, Lucent—watched their shares crater.

Agilent’s problem was simple: its customers were the boom.

The company had ridden the telecom buildout, selling high-end test gear to the giants of the era—Nortel, Motorola, Ericsson, Nokia. When those companies slammed the brakes on spending, Agilent didn’t just see slower growth. It saw orders vanish. At the same time, semiconductors—another major Agilent exposure—rolled over hard as the industry moved from capacity constraints to a full-blown downturn.

By late 2000, cancellations piled up. Even healthcare, which made up roughly 60 percent of revenue, slowed unexpectedly as hospitals delayed purchases in the fog of economic uncertainty. And in the semiconductor and communications businesses, about $500 million in orders simply disappeared—cancelled outright or pushed out indefinitely.

The stock chart captured the mood shift. After trading above $75 at its peak, Agilent slid below $20 by late 2001. Less than two years after arriving as the biggest Silicon Valley IPO to that point, it was suddenly in survival mode.

Restructuring and Layoffs

For CEO Ned Barnholt, the downturn forced a collision between culture and arithmetic. Agilent had inherited the HP Way’s deep belief in taking care of employees—an almost paternal promise that if you did great work, the company would stand by you. But the business was shrinking faster than costs could.

Headcount tells the story in one brutal sequence. Around the 1999 spin-off, Agilent had about 35,000 employees. By May 2001, it had grown to 48,000—hiring had continued as if the slump would be short-lived. Then the cuts came. By 2003, Agilent had eliminated 18,500 positions, taking the workforce down to roughly 29,000.

These weren’t abstract reductions. They were people who had built careers designing oscilloscopes, tuning spectrum analyzers, and shipping instruments with HP-level craftsmanship. The layoffs didn’t just resize the company. They broke a piece of its inherited identity.

Strategic Divestments

Barnholt and his team also saw what Wall Street saw: trimming expenses wasn’t enough. Agilent had come into the market as a grab bag of businesses—telecom test gear, semiconductors, healthcare products, chemical analysis—held together by history more than strategy. In a world now punishing complexity, that mix was a liability.

The first big move came in 2001, when Agilent sold its healthcare products division to Philips Medical Systems for $1.7 billion. Philips had the focus and scale to compete in global medical equipment. For Agilent, the sale did two things at once: it simplified the story and brought in much-needed cash while the downturn raged.

The most consequential divestment followed in 2005. Agilent sold its semiconductor products group to a private equity consortium led by KKR and Silver Lake Partners for $2.66 billion. That business became Avago Technologies, which went public two years later. In a twist that would look surreal in hindsight, Avago eventually bought Broadcom in 2015 and adopted the Broadcom name—creating one of the world’s largest semiconductor companies.

Also in 2005, Agilent sold its 47 percent stake in Lumileds—its high-brightness LED joint venture with Philips—for about $1 billion. LEDs had real promise, but the market demanded huge, ongoing capital investment to keep up, especially against fast-scaling Asian manufacturers. Agilent didn’t have the scale—or the appetite—to fight that war.

By the end of 2005, the company looked nothing like the portfolio it brought into independence. What remained was far more focused: instruments at the center, with test and measurement still the historic core. But another pillar was becoming more important by the quarter—chemical analysis, the chromatographs and mass spectrometers descended from that old F&M Scientific lineage.

It would have been easy to interpret the early 2000s as Agilent simply retreating. The more accurate read is that it was choosing. In the wreckage of the telecom boom, Agilent began drifting—quietly but decisively—toward markets with steadier demand: life sciences and chemical analysis. That pivot wouldn’t be obvious yet. But it was the start of the company Agilent would eventually become.

V. The Life Sciences Pivot: Finding the New North Star (2005-2014)

The Strategic Inflection Point

By 2006, Ned Barnholt had gotten Agilent through the dot-com wreckage and out the other side of a painful portfolio reset. The company was leaner. The balance sheet was steadier. The bleeding had stopped.

But one question was still hanging in the air: what was Agilent going to be now?

Test and measurement was still a great business. It threw off cash, it had deep engineering talent, and it carried decades of credibility. But the growth engine that powered the 1990s—telecom infrastructure—wasn’t coming back. Defense and aerospace helped, but those were mature categories with entrenched competitors and long cycles.

The more interesting momentum was building elsewhere—in a part of Agilent that, historically, had been treated like a cousin of the instruments business. Chemical analysis, the lineage that traced back to those early gas chromatographs, was seeing strong demand from pharmaceutical companies, environmental testing labs, and food safety regulators. And unlike telecom capex, these markets were being pushed by durable, long-running forces: more drug development, tighter environmental rules, and increasing scrutiny of what ends up in the food supply.

Bill Sullivan, who succeeded Barnholt as CEO in 2005 after a long HP career, inherited a company at a crossroads. Sullivan had run multiple Agilent divisions and knew the guts of the organization. His bet was that chemical analysis wasn’t just a stable line item—it was a direction. Life sciences offered fundamentally better long-term tailwinds than electronics testing, and Agilent already had a foothold. The task was turning that foothold into a platform.

Building the Life Sciences Platform

The pivot didn’t happen with one product launch. It happened with a deliberate build-out—adding capabilities that pulled Agilent further into genomics, molecular biology, and diagnostics.

Agilent made acquisitions of smaller genomics companies to expand into next-generation sequencing and related technologies. But the deal that defined the era came in 2012, when Agilent bought Dako A/S for $2.2 billion in cash.

Dako, based in Denmark, specialized in cancer diagnostics—especially tissue-based tests used by pathologists to understand what kind of tumor they’re looking at and how it’s likely to respond to treatment. And the strategic impact was enormous.

First, it pushed Agilent squarely into clinical diagnostics, a regulated market with real barriers to entry. Second, it brought recurring revenue dynamics through consumables tied to ongoing testing. Third, it fit with what Agilent was already building in genomics and molecular analysis, turning separate toolsets into a more complete offering. Most importantly, it made the message unmistakable—inside the company and on Wall Street: life sciences was no longer “one of the businesses.” It was the future.

The Decision to Split

By 2013, Mike McMullen had risen to lead Agilent’s life sciences business, and a familiar pattern started to reappear. The more Agilent leaned into life sciences, the more obvious it became that it was really running two different companies under one roof.

On one side: life sciences and diagnostics—selling to pharma companies, clinical labs, and research institutions, navigating regulation, and building workflows that lived inside laboratories.

On the other: electronic measurement—selling oscilloscopes, signal analyzers, spectrum analyzers, and related tools to semiconductor manufacturers, telecom companies, and aerospace contractors, competing in a world defined by design cycles and capex budgets.

The customer lists barely overlapped. The sales motions were different. The regulatory environments were different. The R&D roadmaps were different. Even the way investors tried to value the company was different.

So in September 2013, Agilent announced it would split into two separate publicly traded companies. The life sciences and diagnostics business would keep the Agilent name. The electronic measurement business would be spun out as Keysight Technologies.

The irony was hard to miss. Agilent itself had been born from HP’s instruments division, and test and measurement had been framed as its “historic core.” Now, just fourteen years later, Agilent was preparing to spin off that core so it could fully commit to the business that had once entered HP as a relatively small acquisition in the 1960s.

The rationale was straightforward. Life sciences had stronger secular growth drivers: expanding pharmaceutical R&D, diagnostics getting more sophisticated and personalized, and environmental and food safety standards tightening globally. Those trends weren’t tied to a single boom cycle.

Electronic measurement was still profitable, but it was facing mature end markets and intense competition. And investors had long struggled to value one company straddling two industries with such different economics.

The split, Agilent argued, would let each business sharpen its strategy, invest appropriately, and attract shareholders who wanted that specific exposure—without the conglomerate discount.

VI. The Keysight Spin-Off: Completing the Transformation (2014)

The Mechanics of Separation

All through 2014, Agilent and its advisors worked through the unglamorous reality of turning one company into two. It wasn’t just a legal filing and a new logo. They had to split manufacturing footprints, sort out intellectual property, negotiate who would keep which internal systems, and put new financial reporting in place so each business could stand on its own.

One move in particular helped clean up the portfolio before the final break. On October 14, 2014, Agilent exited the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) business, selling it to Bruker Corporation. NMR spectroscopy—using magnetic fields to determine molecular structures—fit under the broad umbrella of analytical instruments, but it demanded specialized expertise and meaningful capital investment. In the context of a company trying to sharpen around life sciences and diagnostics, it was one more complexity to shed. The sale simplified the carve-out and added cash to the new Agilent’s balance sheet.

Then came the moment the strategy became irreversible. On November 1, 2014, the separation was complete. Keysight Technologies began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “KEYS,” and Agilent kept the “A” ticker it had carried since the IPO. Agilent shareholders received one share of Keysight for every two shares of Agilent they owned.

The Market's Verdict

The market liked what it saw. Together, Keysight and Agilent were valued more highly than the combined company had been before the split—exactly the outcome Agilent’s leadership had been arguing for when they talked about the conglomerate discount. In the weeks that followed, investors bought into the company they actually wanted: electronic measurement on one side, life sciences and diagnostics on the other.

For Agilent, the split was more than a financial unlock. It was a release valve. Now every dollar of investment could go toward life sciences and diagnostics—chromatography, mass spectrometry, genomics, and pathology—without having to defend priorities for oscilloscopes and signal analyzers at the same time. Future acquisitions could be chosen with a single lens: does this deepen the lab and diagnostics platform?

Leadership snapped into focus, too. Ron Nersesian, who ran the electronic measurement business, became CEO of Keysight. Mike McMullen, the internal champion of the life sciences pivot, became CEO of the new Agilent. Two different playbooks, two different markets, two teams finally optimized for what they actually sold.

And with that, the transformation was complete. The company that had been spun out of HP’s instruments legacy in 1999 had finished its second metamorphosis—into a pure-play life sciences and diagnostics business. The oscilloscopes and signal analyzers that once defined Agilent were now someone else’s job.

VII. Modern Era: Building the Life Sciences Platform (2015-Present)

The Acquisition Engine

With Keysight now out in the world, Mike McMullen could finally run Agilent with one thesis and one scoreboard: become a deeper, broader life sciences platform. The path there wasn’t mysterious. Agilent would keep buying capabilities it didn’t have, slot them into its existing strengths, and then use its global sales and service machine to scale them.

In 2015, Agilent bought Seahorse Bioscience for $235 million in cash. Seahorse made instruments that measure cellular metabolism in real time—essentially letting researchers see how cells produce and use energy as conditions change. That capability mattered more and more in drug discovery, particularly in areas like cancer and immunology. For Agilent, it was an immediate expansion into cell analysis with a distinctive technology and a customer base that overlapped neatly with pharma and academia.

A year later, Agilent added Cobalt Light Systems, a U.K. company focused on Raman spectroscopy. Raman uses laser light to identify materials by their molecular “fingerprint,” which makes it useful in places where you need answers quickly and non-destructively—like pharmaceutical quality control and raw material verification. The £40 million deal didn’t just widen Agilent’s spectroscopy portfolio; it also brought in a team with deep applied optics expertise.

Then came the biggest post-separation move. In 2019, Agilent acquired BioTek Instruments for $1.165 billion. BioTek was well known for microplate readers, automated cell imaging systems, and other workhorse lab instruments that sit at the center of day-to-day biology workflows. Strategically, it doubled down on cell analysis and broadened Agilent’s reach in routine, high-frequency lab work. Financially, it brought meaningful scale, including roughly $180 million in annual revenue, plus a strong brand and long-standing customer relationships.

Put together, these deals had a pattern. Each one added a capability that complemented what Agilent already did well. Each brought specialized talent that knew its niche cold. And each could plug into Agilent’s distribution and service footprint quickly—turning a good product line into a global one.

The Three-Segment Structure

By 2025, Agilent’s business was organized into three reporting segments that made the new identity legible.

Life Sciences and Applied Markets (LSAG) was the biggest. This is the analytical engine room: chromatography, mass spectrometry, spectroscopy, and the software that turns samples into usable data. The customer set is broad but consistent—pharma R&D, environmental testing labs, food safety operations, and academic research groups—anyone whose work depends on getting precise, trusted measurements.

Diagnostics and Genomics (DGG) included Dako, plus genomics tools used across clinical and research settings. This segment served clinical labs diagnosing disease and pharma companies developing companion diagnostics that match patients to targeted therapies. In practical terms, it helped pathologists classify cancers more precisely, which in turn helped oncologists choose treatments with a better chance of working.

Agilent CrossLab (ACG) was the part that looked less like “sell an instrument” and more like “run the lab with the customer.” CrossLab sold the services and consumables tied to the installed base—maintenance, columns, reagents, lab software, and workflow consulting. It brought in recurring revenue, tended to carry higher margins than one-time instrument sales, and increased switching costs over time.

The logic was simple: instruments can be compared feature-for-feature. But the ecosystem around them—consumables that fit, service teams that keep uptime high, software that stitches workflows together—is harder to displace. Once a lab standardizes on a chromatography setup, it often keeps buying the columns and consumables that make that setup work. CrossLab was how Agilent captured that long tail while embedding itself deeper into customer operations.

Leadership Transition

In May 2024, Agilent announced that Padraig McDonnell would succeed Mike McMullen as president and CEO, effective September 2024. McDonnell had joined Agilent in 2002 and moved up through a long series of roles, most recently as president of the Diagnostics and Genomics Group.

This was designed as continuity, not a course correction. McDonnell knew the business, the regulatory realities of diagnostics, and the integration demands that came with building the portfolio. McMullen, the architect of Agilent’s life sciences transformation, would stay on as executive chairman through a transition period.

The timing mattered. By the mid-2020s, the acquisition-heavy build phase was largely done. The pieces were in place. The next test was whether this platform—now spanning instruments, diagnostics, and a growing services-and-consumables engine—could produce the kind of organic growth that life sciences investors expected.

VIII. Business Model & Competitive Dynamics

Technology Platforms Explained

To understand Agilent, you have to understand what it actually sells. This isn’t consumer tech where the value is obvious in ten seconds. Agilent’s products live in labs, and their job is to turn messy reality—blood, water, soil, drug compounds—into clean, defensible data.

Chromatography is the workhorse. It separates a complex mixture into its individual components so you can see what’s in a sample and how much. A useful mental model is a race: different molecules “move” through the system at different speeds based on how they interact with the materials inside the instrument. Gas chromatography uses a gas to carry the sample and works best for volatile compounds. Liquid chromatography—often in high-performance form, HPLC—uses liquids and handles a broader range of molecules. Chromatography does the separating; downstream detectors do the identifying and quantifying.

Mass spectrometry is what you use when you need certainty. It identifies molecules by their mass-to-charge ratio. The instrument ionizes molecules, pushes them through electric and magnetic fields, and measures how they behave on the way to a detector. Because different molecules produce distinct signatures, you can identify compounds with extreme precision, often at very low concentrations. In many real-world workflows, chromatography and mass spec come as a pair: first separate, then identify. Agilent sells systems across that range, from routine lab setups to higher-end instruments built for demanding research and regulated environments.

Spectroscopy is the broader family of techniques that read how matter interacts with light. Different molecules and elements absorb, emit, or scatter electromagnetic radiation in their own characteristic ways—creating a kind of fingerprint. Agilent’s lineup includes atomic spectroscopy for elemental analysis, molecular spectroscopy for compound identification, and Raman spectroscopy, which can characterize materials quickly and often without elaborate sample prep.

Genomics and diagnostics tools push Agilent from “what’s in this sample?” toward “what does this mean for a human being?” These products span research and clinical settings: microarrays, sequencing sample prep kits, and, via Dako, pathology tools used to diagnose disease. Dako’s antibodies and detection systems help pathologists visualize specific proteins in tissue samples—work that can be critical in identifying cancer types and determining whether a tumor is likely to respond to a targeted therapy.

The Razor/Blade Model

Agilent’s economics look a lot like the classic razor-and-blades model—except the “razor” is a six-figure instrument, and the “blades” are the consumables and services that keep it running.

The initial sale is the chromatography system, the mass spectrometer, the spectroscopy setup. That’s the big capital purchase. But once the instrument is installed, the lab needs a steady stream of columns, reagents, and sample prep materials, plus service contracts to keep uptime high and performance within spec.

That recurring layer matters because it tends to be higher-margin and more predictable than instrument cycles. And it’s sticky. Labs can, in theory, buy third-party consumables, but in practice they’re cautious—especially in regulated environments—because a small change can affect data quality, method validation, and compliance.

CrossLab takes this from “repeat purchases” to “embedded relationship.” By wrapping consumables, maintenance, and software into service agreements, Agilent gets recurring revenue, real visibility into day-to-day lab operations, and a much harder-to-replace position inside the workflow.

Competitive Landscape

Agilent plays in crowded markets with serious opponents—companies with scale, focus, or both.

Thermo Fisher Scientific is the giant of life sciences tools, at roughly four times Agilent’s revenue. Thermo wins with breadth and scale: massive distribution, deep R&D budgets, and the ability to be a one-stop shop for many labs.

Danaher Corporation competes through a portfolio of life sciences and diagnostics businesses, including Beckman Coulter and Leica Microsystems, and it has a long track record of disciplined M&A and operational execution (with Veralto recently separated). Danaher isn’t just competing product-to-product; it’s competing with a system.

Waters Corporation is a direct rival in Agilent’s core analytical heartland—chromatography and mass spectrometry—with particularly strong positions in pharmaceutical quality control and research.

PerkinElmer—now Revvity after its 2023 split—serves life sciences, diagnostics, and applied markets with instruments and reagents, with notable strength in areas like genetic screening and environmental testing.

Agilent doesn’t have Thermo’s scale. Its edge is different: deep credibility in chromatography and mass spec, decades-long customer relationships, a large services and consumables engine through CrossLab, and a diagnostics and genomics foothold that has grown more meaningful since Dako.

Geographic Dynamics

Agilent’s business is global, but the drivers vary by region.

The United States is the largest single market, supported by pharmaceutical R&D, major university research ecosystems, and the steady drumbeat of environmental and food safety testing. Public funding also matters here—NIH budgets can ripple through academic labs and research activity.

Europe tends to be steady: pharma, clinical labs, and regulators that take environmental and food safety standards seriously. Stringent requirements create consistent demand for testing—and therefore for the instruments and workflows that make testing possible.

China is the swing factor: huge opportunity, real risk. Investment in pharma and research capacity has been growing, environmental regulation is tightening, and government stimulus programs can create sudden surges in demand for lab equipment. At the same time, geopolitics adds uncertainty—especially around market access and technology restrictions.

In the most recent quarters, Agilent has done well in China, winning about half of competitive tenders tied to government stimulus programs. Whatever the broader tensions, the takeaway is simple: customers there still buy based on performance, trust, and support—and Agilent continues to show up on the short list.

The PFAS Opportunity

One of the clearest examples of how Agilent benefits from regulation-driven demand is PFAS—per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, often called “forever chemicals.” These compounds, used in products ranging from non-stick coatings to firefighting foams, persist in the environment and can accumulate over time. As concern about health effects has risen, governments have responded with stricter testing requirements for water, soil, and consumer products.

That is exactly the kind of problem Agilent is built for. PFAS detection and quantification fit naturally into chromatography and mass spectrometry workflows, and Agilent has invested in specialized methods and consumables to make those tests easier to run and easier to defend. Management has said PFAS-related revenue contributed about 75 basis points to overall growth—meaningful impact from something that barely existed as a market a decade ago.

The bigger point is the pattern. When standards tighten, labs don’t just need more testing—they need more reliable testing. And that creates durable demand for instruments, consumables, and service support that can meet the new bar.

IX. Financial Analysis & Performance

Fiscal 2024 Overview

Agilent runs on a fiscal year that ends in October. Fiscal 2024 closed on October 31, 2024, and it captured the company in a very Agilent kind of moment: the long-term thesis still intact, but the short-term environment choppy.

For the full year, Agilent generated $6.51 billion in revenue, up modestly from the prior year. Under that calm surface, though, the currents ran in different directions. Pharma and biotech—Agilent’s biggest end market—went through a destocking phase as customers worked down inventories built up during the pandemic. At the same time, academic and government labs pulled back amid budget uncertainty, with particular concern around National Institutes of Health funding.

In the fourth quarter, revenue came in at $1.70 billion, about 0.8% higher than the year before. Earnings per share were $1.22 on a GAAP basis and $1.46 on a non-GAAP basis. The non-GAAP number backed out items like amortization of acquired intangibles and restructuring charges—adjustments management argued made it easier to see the underlying operating picture.

Margin Profile

Agilent’s margin structure is one of the clearest tells of what the company really is: not just an instrument maker, but a premium tools-and-workflow business with a meaningful recurring layer.

Gross margin consistently sat above 50%, supported by differentiated instruments and the steady pull-through of consumables and services. Operating margins in the mid-20% range reflected a company that could manage costs without starving the engine—Agilent still had to fund R&D and support the installed base globally.

Within the portfolio, CrossLab tended to be the margin leader, because service contracts and consumables are both recurring and operationally efficient at scale. Diagnostics and Genomics could be attractive too, but it came with ongoing costs for regulatory compliance and clinical validation. Life Sciences and Applied Markets, meanwhile, carried the realities of the instrument battlefield: competitive wins, pricing pressure, and more cyclical buying patterns.

Capital Allocation

Agilent also benefited from a classic advantage in this industry: strong free cash flow. That gave management room to keep playing offense even when customers were cautious.

Historically, capital allocation followed a familiar playbook. First: acquisitions that expand the technology portfolio or deepen positions in key workflows. Second: share repurchases to return capital to shareholders. Third: dividends for a steadier, long-term payout.

Importantly, the M&A approach aimed to be selective rather than splashy. Management positioned the program as disciplined—paying up when an asset mattered strategically, but trying to avoid the kind of overreach that can haunt serial acquirers. A strong balance sheet and investment-grade credit ratings reinforced that flexibility, keeping Agilent ready for opportunities without forcing it into them.

China Opportunity and Risk

China remained the clearest example of Agilent’s “opportunity with an asterisk” dynamic.

On the upside, government stimulus programs boosted procurement of lab equipment, and Agilent was competitive. Management said that in the first quarter of fiscal 2025, China revenue included about $35 million from stimulus-related orders alone, and that Agilent was winning roughly half of the relevant tenders.

But the other side of the coin never disappears. Trade tensions, technology restrictions, and potential localization rules all add uncertainty. China can also tilt toward domestic suppliers when credible alternatives exist. For now, Agilent’s technology leadership and installed relationships kept it in the game—but it was a market where execution mattered and assumptions could change quickly.

X. Playbook: Key Business Lessons

The Art of the Corporate Spin-Off

Agilent’s story is a case study in the rare spin-offs that actually do what they promise. The 1999 separation from HP and the 2014 Keysight split both aimed at the same target: stop forcing unrelated businesses to live under one ticker, and let each one run with a strategy that fits its market.

The lesson isn’t that spin-offs are automatically good. Plenty of them destroy value—through sloppy execution, confused positioning, or spinning a weaker business that can’t stand on its own. The lesson is narrower, and more useful: separations tend to work when the businesses are fundamentally different in what they sell, who they sell to, how they invest, and how they win.

Test and measurement and cancer diagnostics can both be called “instruments.” In reality, they’re different worlds. One lives and dies by design cycles, engineering roadmaps, and capex budgets. The other is shaped by clinical workflows, regulation, reimbursement, and consumables pull-through. In that context, focus isn’t a slogan—it’s a competitive advantage.

Knowing When to Divest

Agilent’s divestitures—healthcare to Philips, semiconductors to the business that became Avago and later Broadcom, LEDs back to Philips—show a different kind of discipline: knowing when something no longer belongs.

The semiconductor sale is the one people love to second-guess. Agilent sold that unit for $2.66 billion in 2005. Years later, it sat inside a company that would be worth well north of $200 billion. On paper, that looks like leaving a fortune on the table. In practice, it’s a reminder that great outcomes require the right owner. Agilent didn’t have the scale, the capital appetite, or the strategic focus to fight at the top of semiconductors. Holding on would have been a bet against its own reality.

The investing takeaway is simple: watch whether leadership can let go. Companies that cling to legacy businesses out of nostalgia or inertia often wind up with a muddled strategy and mediocre returns. The hard call—divest the non-core asset, even if it’s “cool”—is often the value-creating one.

Platform Transition

Agilent also followed a classic B2B evolution: from selling products to building a platform. Pure hardware businesses eventually run into commoditization, pricing pressure, and lumpy purchasing cycles. The way out is to wrap the instrument in everything that makes it useful day after day—consumables, service, software, and workflow support—so the relationship compounds over time.

CrossLab is the clearest expression of that shift. By bundling maintenance, consumables, and lab software, Agilent turns an installed base into an annuity-like stream. It’s higher-margin, more predictable, and harder for a competitor to dislodge. A rival can undercut on the initial instrument sale; it’s much harder to replace the whole operating system of a lab.

Building Moats in B2B Scientific Markets

Agilent’s advantages don’t look like consumer moats. There’s no viral growth loop, no network effects you can see on a chart. The defensibility is quieter—and in regulated scientific markets, often stronger.

Some of it is accumulated technical depth: decades of engineering know-how that shows up as performance, reliability, and trust in data. Some is regulatory competence, especially in diagnostics, where the path to credibility is long and expensive. And a lot of it is relationships—the unglamorous work of keeping instruments running, helping customers validate methods, and supporting workflows that labs depend on.

Once a pharmaceutical company has built and validated quality-control processes around Agilent systems, switching isn’t just a purchasing decision. It can mean re-validating methods, retraining staff, and taking on compliance risk. Even in academia, where budgets are tight, researchers who have spent years building protocols and expertise on a specific instrument line rarely jump ship for marginal improvements.

Managing Cyclicality

Finally, a reality check: scientific instruments are still capital equipment. Capital equipment is cyclical. Customers pause purchases when budgets tighten and rush them when money loosens up. Agilent has lived through that repeatedly—most painfully in the dot-com crash, but also through the 2008 financial crisis and pandemic-era disruptions.

The lesson is to hold two ideas at once. Yes, life sciences and diagnostics benefit from long-term secular growth. And yes, even great businesses in great markets get hit by downcycles. The difference-maker is whether management can absorb the удар—cut costs without gutting the capabilities that matter, protect the installed base, and come out of the downturn positioned to take share when spending returns.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

Cyclical exposure hasn’t gone away. Even after the shift toward life sciences, Agilent is still, in large part, a capital equipment business. And capital equipment follows budgets. Pharma companies can push out instrument purchases when spending tightens. Academic labs live and die by grant cycles and government priorities. You could see that dynamic in fiscal 2024: pharma destocking hit demand, and NIH budget uncertainty weighed on the research customer base.

China is both a growth engine and a risk concentration. China has become a meaningful and rising piece of Agilent’s revenue, which is great—until it isn’t. U.S.–China tensions introduce multiple ways for the relationship to sour: restrictions on trade or technology, pressure to localize sourcing, informal favoritism toward domestic competitors, or supply chain complications. Agilent has managed through this so far, but the risk is that the rules change faster than a global manufacturer can adapt.

Bigger competitors can play a different game. Thermo Fisher and Danaher operate at a scale that lets them spend more on R&D, cover more of the lab’s shopping list, and stay active in M&A without betting the company on any one deal. In an industry that keeps consolidating, that matters. Agilent doesn’t have to be the biggest to win—but it does have to be sharper, faster, and more selective.

Academic and government customers are under pressure. Universities and government labs are a crucial part of the ecosystem, but they’re also vulnerable to funding slowdowns. Management indicated the academic and government segment declined by roughly 7% due to NIH budget uncertainty. If that environment persists, it doesn’t just reduce near-term instrument demand; it can also drag on the broader research pipeline that eventually flows into pharma and clinical testing.

Biotech sensitivity cuts both ways. Agilent benefits when biotech is booming, because fast-growing labs buy instruments, expand workflows, and consume more consumables. But smaller and mid-sized biotech companies depend on capital markets. When venture funding dries up or IPO windows close, spend gets delayed, and in the worst case customers disappear—creating both demand volatility and pockets of concentrated credit risk.

The Bull Case

Agilent sits in markets with real secular tailwinds. Life sciences research, clinical diagnostics, and environmental testing aren’t fads. Aging populations drive more drug development and more diagnostic testing. Food safety expectations don’t loosen over time; they tighten. Environmental monitoring doesn’t get simpler; it gets more comprehensive. Agilent doesn’t need a telecom-style boom to grow—these markets tend to expand through steady, structural demand.

Regulation can be a feature, not a bug. A big chunk of Agilent’s demand is tied to testing that isn’t optional. Requirements around PFAS, pharmaceutical quality control, and clinical diagnostics create work that has to be done, and done in a defensible way. That kind of demand is typically less discretionary than pure research spend, which helps in downcycles.

CrossLab makes the revenue stream stickier. The CrossLab model is the quiet stabilizer: service contracts, consumables, and lab support tied to an installed base that customers rely on every day. Even when labs delay big instrument purchases, they still need uptime, replacement parts, columns, reagents, and method continuity. That recurring, higher-margin layer makes Agilent look less like a one-time equipment seller and more like a workflow partner.

Sharper strategy, tighter execution. At the December 2024 Investor Day, Agilent laid out strategic initiatives aimed at improving execution and accelerating growth. Padraig McDonnell taking over as CEO brought fresh leadership energy while keeping the same overall direction. And the market-focused organizational structure announced at the event was designed to bring Agilent closer to specific customer needs—less “one-size-fits-all,” more targeted playbooks by end market.

A portfolio that’s finally had time to settle. Over the past decade, Agilent assembled major building blocks—Dako, Seahorse, BioTek, and others. The bull argument is that the heavy integration work is now largely done, and the payoff is a more complete set of workflows that can win larger shares of customer spend. It’s broad enough to offer real solutions, but not so sprawling that it turns into a conglomerate again.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of new entrants: Low. High-end scientific instrumentation isn’t a “two engineers and a prototype” category. It requires years of R&D, deep applications expertise, regulatory capabilities in certain segments, and a global service footprint. And even if a new product works, customers still have to trust it—often in regulated environments where mistakes are expensive.

Bargaining power of suppliers: Moderate. Agilent buys components from many suppliers, but some parts have limited substitutes. The 2021–2022 semiconductor shortages highlighted how supply chains can become a constraint. Still, Agilent’s scale gives it leverage in many procurement relationships, even if it can’t fully eliminate single-source risk.

Bargaining power of buyers: Moderate. Large pharma companies can negotiate hard and use volume to push pricing. Academic customers are more price-sensitive, but they’re fragmented. And switching costs—especially where methods have been validated and audited—give Agilent some protection. It’s not frictionless to swap out the system that a regulated lab has built its workflow around.

Threat of substitutes: Low to Moderate. Some applications have alternative techniques, but chromatography, mass spectrometry, and established analytical methods remain the gold standard for most lab measurements. True substitution would require a step-change breakthrough, and those don’t arrive on a predictable schedule.

Competitive rivalry: High. Agilent faces strong competitors across its categories: Thermo Fisher and Danaher with scale; Waters and others with intensity in specific analytical segments. Price competition shows up most where instruments become more standardized, and that can compress margins if differentiation weakens.

Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale economies: Moderate. Agilent benefits from scale in manufacturing, R&D, and service—but it’s not the kind of scale that makes competition impossible. Thermo Fisher’s size is proof that bigger players can push cost and breadth advantages.

Network effects: Limited. These aren’t products that get better simply because more people use them. Each lab’s value is mostly self-contained, unlike software ecosystems.

Counter-positioning: Moderate. Agilent’s focus—deep instrumentation, diagnostics, and lab workflows—can be an advantage versus competitors trying to span the entire life sciences value chain. It can stay narrower, closer to the instrument-and-lab customer, and avoid diluted priorities.

Switching costs: Moderate to High. In regulated environments, validated methods are a moat. Changing instruments can mean revalidation, retraining, and risk—costs that go far beyond the purchase price.

Branding: Moderate. Agilent’s name carries real weight with lab professionals, even if branding matters less here than in consumer markets. Trust in data is the brand.

Cornered resource: Limited. Agilent has talent and know-how, but no single input is truly exclusive or impossible to replicate over time.

Process power: Moderate. Decades of building precision instruments, running global service operations, and supporting customer workflows create institutional muscle memory that’s hard to copy quickly—especially the parts that live in field support, applications expertise, and reliability.

Key Performance Indicators

For investors watching whether the story is strengthening or cracking, two metrics are especially useful:

Book-to-bill ratio. Orders versus revenue. Above 1.0 suggests demand is building; below 1.0 can signal contraction. Because instruments are cyclical, book-to-bill often gives an earlier read on the direction of the next few quarters than revenue does.

CrossLab revenue growth. CrossLab is the highest-quality stream: recurring, stickier, and tied to the installed base. Sustained growth here suggests customers are staying engaged and the platform is deepening. If CrossLab slows materially, that’s a louder warning sign than an instrument downcycle—because it can indicate weakening usage, competitive displacement, or stress in the customer base.

XII. Epilogue: The Path Forward

The December 2024 Investor Day

On December 17, 2024, Agilent gathered investors for a look at what comes next—and, just as importantly, how it planned to run the company next. It was the first full strategy presentation since Padraig McDonnell took over as CEO in September 2024, and it signaled a shift in emphasis.

The headline idea was simple: stop organizing the company around the tools, and start organizing around the jobs customers need done.

Instead of leading with internal technology silos—chromatography here, genomics there—Agilent leaned into a market-focused structure built around the end customers it serves: pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, food, environment, chemicals, and academia. The logic was almost obvious once stated out loud. Labs don’t wake up wanting “more mass spec.” They wake up needing to release a batch, prove compliance, validate a method, detect contamination, or figure out why an experiment failed. The technology is the means. The problem is the product.

McDonnell also highlighted a second theme: labs are becoming software-driven and increasingly automated. Modern workflows produce oceans of data, and the winners won’t just be the companies with the best instruments—they’ll be the ones that help customers manage, connect, and act on all that information. Agilent pointed to investments in lab informatics and workflow automation as ways to expand the value it delivers beyond the hardware itself.

AI and Laboratory Automation

The next wave pushing that shift is AI—less as a sci-fi replacement for scientists, and more as a practical layer that makes labs run faster and more consistently.

Machine learning can help optimize chromatography methods, flag anomalies in quality-control runs, and speed up analytical workflows that would otherwise depend on deep, hard-to-find expertise. Agilent has been investing in those capabilities with a clear point of view: AI doesn’t replace instruments. It makes instruments—and the people using them—more effective.

The demand driver here isn’t just “technology progress.” It’s labor. Labs have real staffing constraints, with experienced analysts retiring faster than new ones are trained. Automation can help fill that gap, boosting throughput and reducing variability at a time when many labs are being asked to do more with the same headcount.

Agilent’s advantage is distribution. When you already have the installed base, the service relationships, and the trust, you have a natural channel to introduce new software and automation layers into workflows customers already run every day.

Precision Medicine Evolution

Diagnostics, meanwhile, sits right at the crossroads of two powerful trends: precision medicine and the expansion of biomarker testing.

The direction of travel in oncology is toward therapies that are narrower, more targeted, and more dependent on selecting the right patients. That selection requires sophisticated diagnostic testing—often tissue-based, often highly regulated, and often integrated into the drug development process itself through companion diagnostics.

This is exactly where Dako fits. Dako’s pathology tools help pathologists characterize tumors and guide treatment decisions. As pharma develops more targeted therapies, the need to identify which patients are likely to respond doesn’t shrink—it grows. And the more central diagnostics become to treatment decisions, the more valuable reliable, validated testing workflows become.

The Journey Complete

From a coin flip in a Palo Alto garage to a roughly $6.5 billion life sciences company, Agilent’s story runs across nearly nine decades and, effectively, three identities. The audio oscillator that helped launch Hewlett-Packard in 1939 has little in common with the chromatography systems and cancer diagnostics Agilent sells today. And yet the connective tissue is real: engineering rigor, trust in measurement, and the belief that better instruments enable better decisions.

The most distinctive feature of Agilent’s journey might be its willingness to let go. Over and over, it divested businesses that once looked central—healthcare products, semiconductors, LEDs, and eventually the electronic measurement division that became Keysight. Those weren’t just financial transactions. They were identity changes, each one requiring the company to admit that what made it successful yesterday didn’t have to define it tomorrow.

For other conglomerates staring down their own portfolio questions, Agilent offers lessons in both mechanics and mindset. The mechanics: structure separations carefully, maintain operational focus through upheaval, and integrate acquisitions without losing the thread. The mindset: be honest about where you truly have the right to win—and have the courage to build around that, even when it means walking away from legacy pride.

Agilent began as HP’s instruments division, evolved through a volatile era as a diversified electronics company, and emerged as a life sciences and diagnostics platform. What comes next will depend on whether it can turn automation, software, and market-focused execution into durable growth—while competing against larger, well-funded rivals chasing the same prize.

The measurement company Hewlett and Packard started in 1939 has transformed beyond recognition. But the purpose that started it all—enabling discovery through precision measurement—still holds.

XIII. Recent News

In December 2024, Agilent held its Investor Day, where new CEO Padraig McDonnell put a finer point on the strategy: organize around the markets customers live in, not the technologies Agilent sells, and use that shift to accelerate growth.

A few weeks earlier, the company reported fiscal Q4 2024 revenue of $1.70 billion, a small year-over-year increase in a quarter that still reflected a tough environment—especially in pharma and in academic labs.

To match the strategy to the org chart, Agilent also announced restructuring aimed at getting closer to customer workflows. The company began moving away from a technology-first setup and toward market-focused groups spanning pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, food safety, environmental, chemicals, and research.

Agilent continued investing in PFAS testing solutions as regulators around the world expanded requirements for detecting and quantifying per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. It’s exactly the kind of regulation-driven demand that plays to Agilent’s strengths in chromatography and mass spectrometry—and it’s become a meaningful growth lever as the “forever chemicals” issue moves from public concern to enforceable standards.

And in the background, the leadership handoff that had been planned for months became official: McDonnell took over as CEO in September 2024, with Mike McMullen staying on as executive chairman through the transition.

XIV. Links & Resources

Company Filings: - Agilent Technologies Form 10-K Annual Reports (SEC EDGAR) - Agilent Technologies Form 10-Q Quarterly Reports (SEC EDGAR) - Agilent Technologies Proxy Statements (SEC EDGAR) - Agilent Technologies Investor Day 2024 presentation materials

Historical Context: - Hewlett-Packard Company archives and historical materials - The HP Way by David Packard - Keysight Technologies Investor Relations (for the electronic measurement timeline)

Industry Analysis: - Thermo Fisher Scientific annual reports (competitive context) - Danaher Corporation annual reports (competitive context) - Waters Corporation annual reports (competitive context)

Regulatory and Market Background: - Environmental Protection Agency PFAS testing guidelines - FDA companion diagnostics guidance documents - National Institutes of Health budget and funding reports

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music