Aflac: The Duck That Built an Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s January 2000. Americans settle in for primetime TV and get hit with something that feels almost… wrong for an insurance company. A small white duck barges into scene after scene, trying to interrupt polite conversations about coverage. “AFLAC!” it quacks—over and over—getting more furious as the humans keep talking as if it isn’t there.

That duck didn’t just become a mascot. It became a lever. Within three years of the first ad, Aflac’s U.S. sales doubled, and brand recognition rocketed from under 10% to above 90%.

But here’s the twist: when the duck first quacked on American television, Aflac was already enormous—just not in America.

While most people in the U.S. still couldn’t pronounce the name, Aflac had spent decades quietly building a power base on the other side of the Pacific. By 2000, it insured one in four Japanese households. It controlled 88% of Japan’s cancer insurance market. It was the largest foreign insurance company operating in Japan—full stop. And that was in a country whose insurance industry had long been considered a fortress, famously difficult for outsiders to enter.

Today, Aflac brings in nearly $19 billion a year in revenue. Since inception, it has paid out more than $200 billion in claims. And remarkably, it’s still the dominant player in supplemental insurance in both Japan and the United States—two markets with totally different cultures, regulations, and consumer habits.

So the question at the heart of this story sounds simple, almost quaint: how did three brothers from Columbus, Georgia, build the largest foreign insurance company in Japan?

The answer runs through a product that didn’t exist until they created it: cancer insurance. It runs through a strange kind of regulatory gift—an opening Japanese policymakers allowed because they assumed nobody would want “dreaded disease” coverage anyway. And it ends with a marketing revolution that proved you could sell a serious financial product with humor, and win.

This is a story about finding a niche so specific the incumbents ignore it—and then scaling that niche until you’re too big to dismiss. It’s a story about distribution, patience, and the rare kind of conviction it takes to play a long game in a business built on promises.

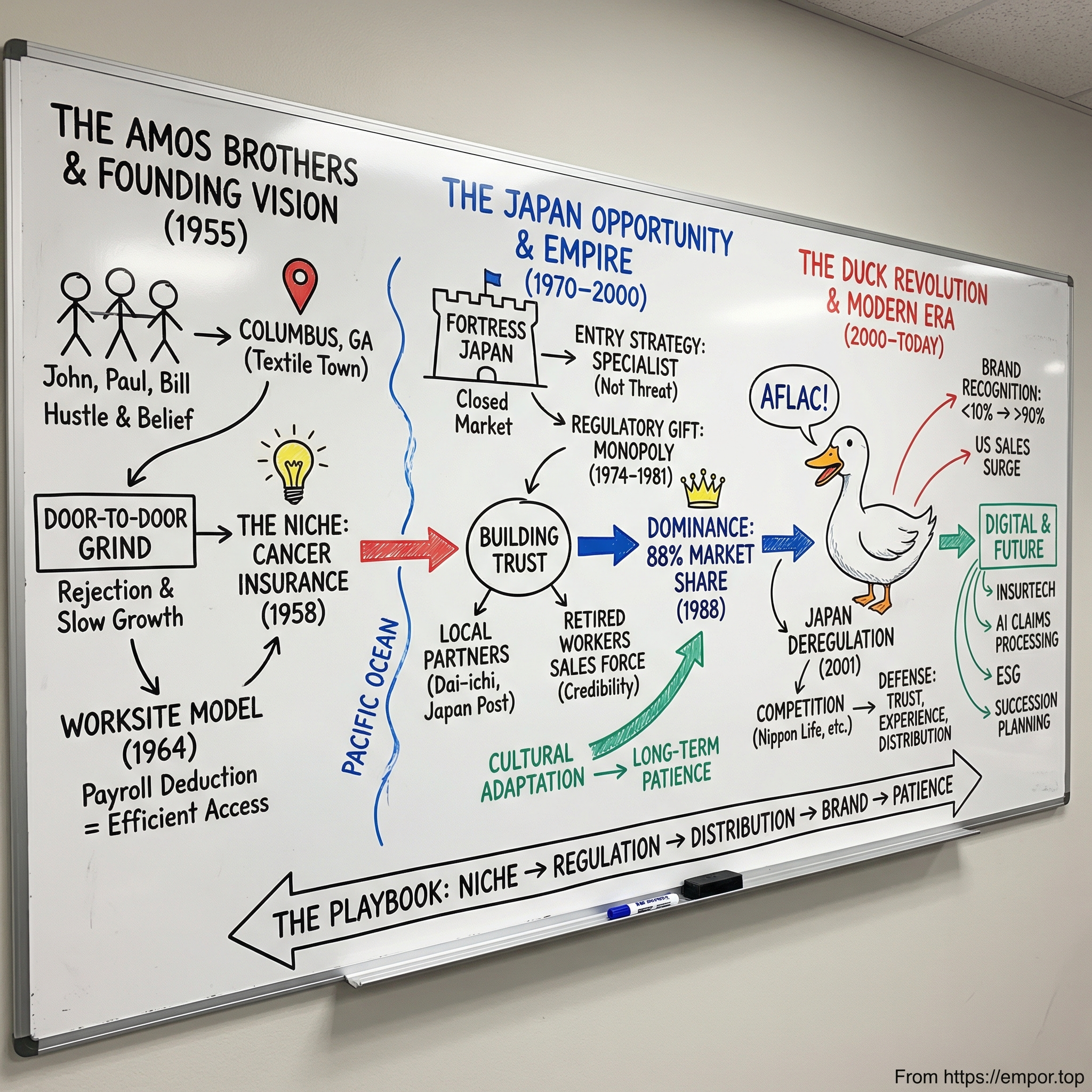

Here’s the roadmap: we’ll start with three brothers selling insurance door-to-door in the American South. Then we’ll follow the invention of cancer insurance, the audacious push into Japan, and the decades-long build that made Aflac a giant there—before the duck ever showed up. From there, we’ll get to the campaign that changed everything in the U.S., and finish in the modern era as Aflac evolves into a digital insurance heavyweight.

And along the way, we’ll pull out the playbook—because Aflac isn’t just a great advertising story. It’s one of the most fascinating business case studies hiding in plain sight.

II. The Amos Brothers & Founding Vision

Columbus, Georgia, in the mid-1950s was a textile town in transition. The mills that had anchored the local economy for generations were starting their long slide, and a lot of ambitious young people were scanning the horizon for something bigger than cotton.

Three of them were brothers: John, Paul, and Bill Amos. They weren’t born into Wall Street connections or a legacy insurance franchise. What they had was hustle, a tight-knit family unit, and a belief that a huge financial problem was hiding in plain sight.

John Amos, the eldest, was the engine. Born in 1924, he grew up in the shadow of the Depression, served in World War II, and came home with the intensity you see in a lot of veterans of that era—impatient with small dreams, allergic to complacency. He’d also watched his father struggle in business, and it left a mark: a fear of going under, and an obsession with the idea that ordinary families needed a better safety net.

To John, insurance wasn’t just paperwork and premiums. It was a promise. And in postwar America—where medical care was getting more expensive and coverage was often thin—that promise mattered.

In 1955, the brothers pulled together their resources and recruited family and friends to back them. Altogether, they raised roughly $300,000 in capital. It was real money, especially for Columbus, but in insurance it was still tiny—nowhere near enough to go toe-to-toe with the big incumbents.

They incorporated with a name that sounded like it belonged on the door of a small-town law office: American Family Life Insurance Company of Columbus. It was long, earnest, and forgettable. Eventually it would be shortened into an acronym. Much later, a duck would turn that acronym into one of the most recognizable brand sounds in America.

At the start, though, there was nothing cute about it.

The early years were pure grind. The brothers and a small team of agents sold life, health, and accident insurance door-to-door across Georgia and Alabama—long days, summer heat, and the kind of rejection that stacks up fast when you’re asking people to pay for something they hope they’ll never use. John later talked about driving hundreds of miles on back roads to reach rural communities where “insurance salesman” was not a compliment.

They weren’t lazy. They weren’t naïve. They were just early—early to the realization that in insurance, it’s brutally hard to win by selling the same thing as everyone else.

The first year showed a flicker of traction: 6,426 policyholders signed up. That was enough to keep moving, enough to prove the company could sell. But the bigger reality didn’t change. Growth was slow. Profitability was elusive. They were working themselves to the bone to win customers, and the business still felt like it was pushing uphill.

By 1958—three years in—John hit a decision point. The company wasn’t collapsing, but it wasn’t breaking out either. In a market dominated by established brands with deep agent networks and decades of trust, they were just another small shop with products that looked like everyone else’s.

If they wanted to survive, “try harder” wasn’t the answer. They needed a wedge: a niche so specific they could own it.

The spark came from an unlikely place: polio. More specifically, from the insurance products that had been designed years earlier to help families deal with the financial aftermath of a polio diagnosis—policies that paid benefits when a catastrophe hit, not when you hit retirement age. John studied how those policies were structured, why people bought them, and what they really sold underneath the fine print: peace of mind.

And then he asked the obvious follow-up question. If polio had an insurance product built around it… what about the disease that now scared people even more?

Cancer didn’t have a vaccine. It didn’t have a cure. It was becoming one of the leading causes of death in America, and even families with “good” coverage discovered how many costs could still slip through the cracks—extended hospital stays, treatments that weren’t fully covered, and the everyday bills that didn’t stop just because life had.

John saw the gap. And he saw a business built around that gap.

What if there were insurance specifically for cancer—not a general health policy that might cover some treatment, but dedicated coverage that paid cash benefits directly to the policyholder after a diagnosis? Money they could use however they needed: to bridge what other insurance didn’t, to replace income, to keep the mortgage current while the family dealt with the unthinkable.

It was a bold idea. It was also the first time American Family Life had something the giants didn’t.

And it was about to define the company’s future.

III. The Cancer Insurance Innovation (1958)

In 1958, the state of Georgia approved something that, in hindsight, feels obvious: the first cancer insurance policy in American history.

At the time, it was anything but.

John Amos and his team were taking the basic logic behind old polio policies—cash benefits for a specific, terrifying diagnosis—and reapplying it to the disease people were even more afraid to name out loud. But the moment you try to turn that idea into an actual product, the easy part ends and the hard questions begin.

How do you price coverage for a disease whose causes weren’t well understood? How do you forecast claims when cancer rates were rising and outcomes were unpredictable? And how do you convince regulators—trained to think in neat, familiar categories—that this thing belonged in the rulebook at all?

Aflac pushed through anyway. About 150 licensed agents fanned out across Georgia and Alabama with a pitch that didn’t pretend cancer was likely. It just acknowledged what people already knew in their gut: if it happened, it could wipe you out financially. The company wasn’t selling doom. It was selling the ability to keep the lights on, pay the mortgage, and stay afloat while life got turned upside down.

The market answered quickly. In the first year, Aflac sold 5,810 cancer care policies. That isn’t a tidal wave—but it was proof. A category the industry had shrugged at was real. People wanted this coverage, and they were willing to pay for it.

What Amos had tapped into was the psychology of supplemental insurance. This wasn’t meant to replace traditional health insurance. It was a second layer—protection for the gaps that only show up when something catastrophic happens. The premiums could be kept relatively affordable because the coverage was narrow. And because benefits were paid in cash, policyholders weren’t trapped waiting for reimbursements or untangling medical billing. They could use the money however they needed, in the moment they needed it most.

Still, the early years were a grind. Some regulators looked at cancer insurance and saw a product that might be exploiting fear. Others questioned whether it duplicated what people already had. Aflac’s leadership ended up doing as much explaining as selling—hours in meetings, endless clarifications, careful relationship-building with the state insurance commissioners who controlled whether this category could expand beyond a few friendly states.

Education mattered on the consumer side too. Most Americans assumed that “good health insurance” meant you were protected. Aflac’s agents had to walk families through the uncomfortable reality: even solid coverage often left meaningful expenses uncovered, and regular household bills didn’t stop just because a diagnosis arrived.

Then, in 1964, Aflac made a decision that changed the trajectory of the entire company: it shifted from door-to-door selling to the workplace.

Instead of hunting for customers one household at a time, Aflac began approaching employers and offering cancer insurance as a voluntary benefit. Employees could opt in, and premiums came straight out of payroll deductions.

It was simple, and it solved everything at once. Aflac gained efficient access to large groups of customers. The employer’s involvement acted as a kind of trust filter. Premium collection became automatic. And the cost of acquiring each policyholder dropped dramatically.

Over time, that worksite engine became the company’s distribution superpower. By 2003, more than 98% of Aflac policies in the United States were issued on a payroll deduction basis. Competitors would eventually copy the approach, but Aflac had years of head start—and a brand built around being the specialist in coverage everyone else ignored.

Cancer insurance, paired with worksite distribution, gave Aflac something rare in insurance: a defensible wedge. They weren’t trying to out-muscle the giants in crowded categories like life insurance. They were expanding a territory the giants didn’t think was worth defending.

And while that territory was growing fast in the U.S., John Amos was already thinking bigger. He’d found a product that could open doors. Now he needed a market where the doors were closed to almost everyone.

He was about to go looking across the Pacific.

IV. The Japan Opportunity & Entry (1970–1974)

When John Amos stepped off a plane in Tokyo in 1970, he walked straight into an industry designed to keep outsiders out.

Japan’s insurance market was a fortress—domestic incumbents, relationship-driven distribution, and regulators who could simply say no without explanation. A few American insurers still operated under old, grandfathered approvals dating back decades. But for more than twenty years, no new foreign insurer had been welcomed in.

Amos looked at that same landscape and saw something else: a wide-open category.

Cancer fear was intense. Health coverage still left meaningful gaps. And despite all of Japan’s sophisticated financial institutions, no one was selling cancer insurance. Japan was industrializing fast, incomes were rising, and a growing middle class was starting to think less about survival and more about security—how to protect a family if something truly catastrophic happened.

Still, wanting in and getting in were two very different things.

Japan’s Ministry of Finance held insurance licensing tightly, and the process was famously opaque. Approval depended on local relationships and cultural fluency—two things foreign companies rarely had. Meanwhile, the major domestic insurers had enormous political influence and little appetite for inviting American competition into their most profitable markets.

And then there was cancer itself. In Japan, the disease carried a stigma that went beyond what Aflac had navigated in the U.S. For years, many physicians routinely avoided telling patients their diagnosis, worried the psychological blow would make outcomes worse. Even in 1992, a survey found only 13 percent of Japanese doctors communicated cancer diagnoses directly to patients. Selling cancer insurance in that environment wasn’t just a regulatory challenge. It was a cultural one.

Amos didn’t try to brute-force the problem. Over the next four years, he invested in relationships, studied how Japanese insurance actually worked, and built a strategy around a simple insight: Aflac wasn’t going to storm the fortress. It needed to be invited in.

So Aflac positioned itself not as a direct threat to Japanese insurers, but as a specialist offering something Japan didn’t yet have. It wouldn’t go after the core life insurance business. It would introduce an entirely new category—cancer insurance—and stay in that lane.

That framing mattered. It gave Japanese regulators a way to approve Aflac without looking like they were undermining domestic champions. In 1974, the Ministry of Finance granted Aflac a license to sell insurance in Japan—making it only the second American insurer allowed in more than two decades. The unspoken understanding was clear: Aflac would focus on cancer insurance, and the traditional strongholds would remain Japanese.

With the license secured, Aflac moved quickly to solve the next problem: distribution.

Instead of trying to build an agent force from scratch—slow, expensive, and likely to hit resistance—Aflac partnered with institutions Japanese consumers already trusted. Dai-ichi Mutual Life Insurance, Japan’s second-largest insurer, became a key ally. Japan Post Holdings, with its unmatched nationwide reach, joined the network.

For Aflac, these partnerships provided immediate credibility and access. For the Japanese partners, they offered something just as valuable: a differentiated product they didn’t have to invent themselves.

Then Aflac made a sales decision that fit Japan better than any American playbook could. Rather than staffing up with young, aggressive closers, the company hired retired workers—people in their fifties and sixties who carried social credibility and knew how to talk about serious subjects with the right tone. They sold less like hustlers and more like counselors, speaking to families about responsibility, stability, and peace of mind.

It worked on multiple levels. It eased recruiting in a market where ambitious young talent preferred prestigious domestic firms. It matched cultural expectations around who should discuss illness and death. And it turned community ties into distribution—people selling to people who already knew them.

The timing, too, was on Aflac’s side. Cancer awareness was rising just as Aflac arrived with a product built specifically around cancer fear. Economic growth was expanding household budgets right as Aflac offered a new way to buy protection. The licensing breakthrough, the partnerships, and the sales model all clicked into place.

What happened next would be even bigger than Amos expected.

V. Building the Japanese Empire (1974–2000)

Aflac’s first decades in Japan look, in retrospect, like one of those growth stories that sounds made up until you see the receipts.

In 1974, Aflac arrived with no customers, no household name, and no history in a market that didn’t exactly roll out the red carpet for foreign financial firms. And yet, just twelve years later, Aflac Japan had grown to 5.4 million policies—up from 731,000 a decade earlier. For a company selling a brand-new category of insurance in a famously closed market, it was staggering.

A big part of that rocket fuel was a regulatory gift—one the Japanese government didn’t fully realize it was handing over.

From 1974 until 1981, Aflac had a literal monopoly on cancer insurance in Japan. No domestic insurer could sell it. No other foreign insurer could sell it. The Ministry of Finance had effectively carved out a protected product category and let Aflac own it, under the assumption it would stay small. The logic, as it was later described, was basically: “Nobody is going to buy dreaded disease insurance, so let the Americans have it.”

Then Japan’s reality changed.

In 1981, cancer became the leading cause of death in the country. The product regulators had treated like a niche curiosity suddenly became the coverage families most wanted—right when Aflac was the only serious option, with distribution in place and a head start measured in years.

Even when the ministry finally allowed domestic competition starting in 1981, Aflac wasn’t a newcomer anymore. It already had momentum, relationships, and millions of policyholders. By 1988, it controlled 88 percent of Japan’s cancer insurance market—an almost absurd figure for any company, let alone a foreign one.

And the oddest part is that the same trade wrangling that was supposed to open Japan’s markets ended up reinforcing Aflac’s advantage. Through the 1980s and 1990s, regulators kept the biggest domestic insurers from entering some supplemental product lines until 2001. Every year the giants stayed out, Aflac dug a deeper moat.

By 1987, Japan wasn’t just a growth market for Aflac—it was the business. The country delivered about two-thirds of total revenues and 70 percent of after-tax earnings. Aflac went to Japan looking for diversification and got something far stranger: an American insurer whose “foreign” operation became the center of gravity.

Milestones started stacking up like a victory lap. In June 1997, Aflac became the first foreign insurer in Japan to exceed ¥2 trillion in gross assets—an unmistakable signal it had crossed from niche outsider to major financial institution. By 1999, it had established policies with employees at 95 percent of the companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. In a corporate culture that prizes institutional legitimacy, that kind of penetration was as close as you get to a stamp of national approval.

So how did Aflac pull it off?

The product fit mattered. Japanese families felt a deep obligation to shield each other from financial hardship, and cancer insurance offered a simple, concrete way to do that. And because benefits were paid in cash, the coverage wasn’t just about medical bills—it was about everything that breaks when life breaks: income disruption, caregiving costs, and the everyday expenses that keep coming no matter what the diagnosis is.

Distribution mattered just as much. Aflac didn’t rely on a single channel; it kept widening the funnel. It built relationships with banks, post offices, and retailers—places people already trusted and already visited. And when a 1996 law opened the door to selling insurance online and by mail, Aflac was among the first to take advantage, experimenting with direct channels while many competitors stayed anchored to traditional agent models.

And then there were the people doing the selling. Aflac’s retired-worker sales force turned out to be a perfect match for the culture. These weren’t slick closers. They were familiar faces with credibility, speaking in the language of responsibility and family duty. In a society where cancer could still be difficult to talk about openly, they weren’t just pushing policies. They were making the topic discussable—and offering a plan.

By the end of the century, Aflac had done what seemed impossible when John Amos first visited in 1970: it became a trusted, mainstream institution in Japanese financial life, standing alongside the domestic giants rather than beneath them. What began as a regulatory experiment turned into something closer to infrastructure—woven into how Japan thought about paying for the financial shock of illness.

And yet, back in the United States, Aflac had the opposite problem. It was massive, profitable, and battle-tested—but most Americans still didn’t know its name.

That was about to change. Dramatically.

VI. The Duck Revolution (1999–2000)

By the late 1990s, Aflac’s U.S. business had a weird problem for a company that was already winning. The products worked. The worksite model was humming. The company was profitable. But ask the average American if they’d heard of Aflac and you got the same response: nothing. After nearly a decade of conventional advertising, brand awareness was still stuck around 6 or 7 percent.

That wasn’t just an ego issue. Aflac didn’t rely on ads to drive direct sales—its agents typically met employees through employers—but awareness still mattered. If you’re choosing a voluntary benefit at work, you’re far more likely to say yes to a name you recognize. And Aflac, for all its scale and experience, still sounded like a typo.

The company had tried to fix that the normal way: nine years, tens of millions of dollars, and a parade of traditional, responsible financial-services campaigns. They explained supplemental insurance. They explained the gaps in coverage. They explained why you should care. The ads were polished. They were also invisible.

So Dan Amos—John Amos’s son, who had taken over as CEO in 1990—decided to throw out the rulebook. In 1999, Aflac hired the Kaplan Thaler Group, a New York agency known for taking creative swings. The assignment was deceptively hard: make Americans remember an odd name attached to an unglamorous product.

The idea that solved it didn’t come from a conference room. It came from a lunchtime walk through Central Park.

One of the agency’s art directors was stuck, turning the problem over and over, when he started muttering the name to himself: “Aflac, Aflac, Aflac.” And then he heard it. The sound wasn’t corporate. It wasn’t financial. It was a quack.

He ran back to the office with a concept that was so simple it felt ridiculous: a duck that interrupts scenes by quacking “AFLAC!” louder and louder, as humans keep ignoring it. It didn’t explain the product. It didn’t teach you about coverage. It just made the name impossible to forget.

The creative team loved it. Aflac’s leadership did not.

“We knew we were making fun of our name and we were not sure how that would turn out,” Dan Amos later said. “Nobody was doing humor in financial services ads to a great degree. There was a dead look on everyone’s faces when we first showed it.”

And you can see why. Insurance is about cancer, disability, death—the stuff you don’t joke about. A quacking duck felt like a risk to the company’s credibility, and maybe even to its agents in the field. How do you sell serious coverage when your brand is suddenly a frustrated waterfowl?

But the numbers were brutal. Aflac had already done “credible.” It had already done “professional.” And it had gotten nowhere. So they took the leap.

On January 1, 2000, the duck debuted. The first spot was almost absurdly plain: two men sit on a park bench, talking about insurance, while a duck waddles nearby, losing its mind because they keep missing the obvious answer. “AFLAC!” it quacks, louder, sharper, more offended each time. The men keep talking, completely oblivious.

America didn’t just notice. It reacted.

In the first two weeks of 2000, Aflac generated more sales leads than it had in all of 1998 and 1999 combined. Phones lit up. Agents suddenly weren’t starting conversations from scratch—prospects were coming to them, asking about “the duck company.”

Then the business followed the brand. Annualized premium sales jumped 28.5 percent in the second quarter of 2000. Name recognition, which had been stuck below 10 percent, surged to 71 percent after the duck arrived. And as the campaign kept rolling—more spots, more scenarios, more quacks—brand recognition climbed above 90 percent.

The duck had done in months what nine years of traditional advertising couldn’t: it made Aflac stick in people’s heads.

And it did it without destroying trust. The ads created attention and affection, but the product experience did the heavy lifting afterward. The duck got you to remember the name; the coverage and service gave you a reason to keep it.

Even Dan Amos, who’d initially worried about the whole thing, became its biggest champion. He’d learned the modern marketing lesson the hard way: in a world overflowing with messages, memorability beats dignity. Being respectable doesn’t help if nobody remembers you exist.

The duck eventually crossed the Pacific too—though not unchanged. Aflac Japan introduced its own version in 2003, but tuned to local sensibilities: softer, more endearing, less aggressively comedic. Same basic idea, different flavor. And it worked there as well, proving the mascot wasn’t a one-country gimmick. It was a brand machine—portable, adaptable, and powerful.

VII. Japan Deregulation & Competition (2001–2010)

In January 2001, the special set of regulatory conditions that had insulated Aflac in Japan finally started to disappear. The moment the market opened, Nippon Life—the domestic giant that had spent years on the sidelines—moved fast, rolling out competing cancer insurance almost immediately. Tokio Marine, MetLife Alico, and others piled in right behind.

For the first time since Aflac’s early run, the company wasn’t competing in a category it essentially owned. The easy story wrote itself: the foreigners had a nice run, but now the home team was here, with deeper relationships, bigger balance sheets, and distribution muscle that seemed impossible to match.

Plenty of observers predicted Aflac’s share would crater.

It didn’t.

Aflac Japan’s grip loosened from its monopoly-era peak, but then it held—settling around roughly half the market, still an enormous lead in a now-crowded field. The company that had used protection to build an empire turned out to be very good at defending one.

Why? Start with trust. Aflac had spent decades becoming a familiar name in Japanese households—not through flashy promises, but through the unglamorous things that actually matter in insurance: policies that worked, and claims that got paid. People who had been paying premiums for years, and had seen Aflac perform when it counted, weren’t eager to jump to a newcomer just because it wore a domestic logo.

Then there was experience. By the time the Japanese giants entered cancer insurance, it was new ground for them. For Aflac, it was the core craft. It had been refining benefits, pricing, and product design for years. In a business where small details determine whether a policy feels trustworthy or frustrating, that learning curve is a weapon.

Distribution held, too. The partnerships Aflac had built across banks, post offices, employers, and retailers didn’t vanish just because competitors arrived. Those relationships kept Aflac’s products in front of customers at the exact moment the category became a battleground. Japan Post, in particular, gave Aflac reach that was hard for anyone else to replicate.

And then, in 2003, the duck arrived in Japan.

It wasn’t the same brash, interrupt-everyone character Americans saw. Japan’s version was tuned to local taste—softer, more reassuring—but it did the same job: it refreshed the brand in the public’s mind. In a down economy, with uncertainty high and options multiplying, that reinforcement mattered. Aflac Japan’s sales rose by 12 percent that year, a reminder that awareness isn’t just for growth markets—it’s also how you defend your base when competitors show up with lookalike products.

By the middle of the decade, Aflac had stacked up proof points that would’ve sounded absurd back in 1970. It insured one out of every four Japanese households. And it took the title of Japan’s largest insurance company from Nippon Life—an incumbent that had held that crown for more than a hundred years.

The company didn’t treat competition as a one-time event, either. It kept pushing on cost and convenience, leaning into channels opened by the 1996 law that allowed policies to be sold online and by mail. It invested in claims-processing technology to keep payouts fast—because in insurance, speed and certainty aren’t features. They’re the brand.

The market stayed tough. Domestic insurers, once inside the category, weren’t leaving. Price pressure increased. Features converged as rivals copied ideas Aflac had pioneered and worked them into their own offerings.

But Aflac’s advantages held up because they were real. The head start was enormous, and it compounded. The cultural credibility that once seemed impossible for a foreign insurer had been built the slow way—through local partners, local hiring, and products designed for Japanese consumers rather than imported from an American playbook.

And that’s the deeper lesson of this era. Regulation helped Aflac get established, and for a while it gave Aflac a wide-open lane. But the reason Aflac stayed on top after deregulation wasn’t because the lane stayed open. It was because, while it had the advantage, it used the time to build something defensible.

When the walls came down, Aflac didn’t disappear.

It fought—and it held.

VIII. Modern Era: Digital Transformation & Evolving Markets (2010–Today)

Dan Amos had taken over as CEO in 1990, as his father’s health declined. By the 2010s, he was staring down a different kind of test: how do you modernize a company built on twentieth-century distribution—agents, worksites, payroll deduction—without breaking the machine that made it great?

And the pressure was coming from Aflac’s most important market.

Japan’s population began declining in 2010, making it the first major economy to cross that line. For insurers, that’s not just a demographic headline—it’s a structural problem. Life insurance economics lean on a steady supply of younger, healthier policyholders to balance the rising costs of older ones. When a country gets older and smaller at the same time, the math gets harder. It also meant fewer working-age people to reach through the worksite channels Aflac had mastered, and fewer fresh households coming into the system.

Aflac’s answer wasn’t to abandon what worked. It was to double down on the part of the portfolio that fit the moment. “We have continued to focus on third sector products as well as introducing these policies to new and younger customers,” Amos said. In industry language, “third sector” is the world Aflac helped popularize: supplemental products like cancer, critical illness, and nursing care—coverage that sits between traditional life insurance and health insurance. If anything, an aging society doesn’t make those products less relevant. It makes them feel more urgent.

At the same time, Aflac Japan worked to stay appealing to younger customers. It introduced updated life insurance products aimed at that audience and drove a sales increase of 12.3 percent. It also kept shifting distribution toward the channels younger consumers actually used—online and mobile—rather than assuming the next generation would buy insurance the way their parents did.

In the United States, Aflac pushed growth in a different way: it widened what it could sell and who it could sell to. The 2009 acquisition of Continental American Insurance Company, for $100 million, helped Aflac operate on both the individual and group platforms. That mattered because it let Aflac serve large employers that wanted supplemental benefits integrated into a broader benefits package—not just offered as a standalone voluntary add-on.

Behind the scenes, the company leaned hard into technology. Claims processing—historically paper-heavy and slow—moved toward digital and automated workflows. Aflac rolled out artificial intelligence to sharpen underwriting and flag potentially fraudulent claims. Customer service expanded beyond phone calls and paperwork into mobile apps and chat-based tools, so policyholders could file claims, check coverage, and update information without waiting on a person.

The goal wasn’t tech for tech’s sake. Insurance is an information business: collect premiums, evaluate risk, pay claims. Technology made those steps faster and cheaper, and at Aflac’s scale, the payoff was real. Millions of policyholders across two countries also meant something else: data—enough to justify big infrastructure investments and to train the systems that made them useful.

Even so, Japan remained the center of gravity. In 2012, Japan still accounted for 77 percent of Aflac’s total revenue—lower than the peak years, but a reminder of just how concentrated the business was in one foreign market. That split moderated further by 2024, though Japan remained the majority contributor.

And the model kept holding up. In 2024, Aflac generated $19.12 billion in revenue, staying firmly in the top tier of global supplemental insurance. Even as InsurTech startups and big tech companies flirted with financial services, Aflac’s mix of scale, brand, and cost discipline kept it resilient.

The duck stayed at the center of it all—still the shorthand for the company in both markets—but it learned new tricks. The campaigns evolved with how people consumed media, expanding beyond traditional television into social platforms, streaming video, and influencer partnerships. What had felt like a risky joke in 2000 had matured into a durable brand asset: instantly recognizable, flexible, and oddly timeless.

By this point, Amos was deep into his fourth decade at the helm. The company that three brothers started in 1955 had become a Fortune 500 institution with a global footprint. But the strategic DNA stayed familiar: find the gap, build a distribution advantage, earn trust through claims-paying performance, and keep playing the long game.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Aflac’s story is a masterclass in how to build an enduring advantage in a business that, on the surface, looks commoditized. Strip away the duck, the slogans, even the geography, and what’s left are a few repeatable moves—executed with unusual patience over decades.

Finding and Dominating a Niche

The Amos brothers didn’t march into the market and try to out-MetLife MetLife. They did the opposite. They found a gap the incumbents weren’t built to care about—and then they built the whole company around that gap.

Cancer insurance was the wedge. It wasn’t a feature upgrade on life insurance. It was a new category. And once Aflac became synonymous with that category, it gained something most insurers never get: a reason to exist that wasn’t “we’re also here.”

What looked like a niche—maybe even a morbid one—turned out to be a platform. From that base, Aflac expanded into broader supplemental coverage, then took the model overseas. But it all traced back to one move: own something specific before you try to own something big.

The Power of Regulatory Arbitrage

Aflac didn’t conquer Japan by force. It got in through a door that was left unlocked because nobody thought it mattered.

Japanese policymakers effectively handed over the dreaded disease market on the assumption it would stay small. And because domestic giants were kept out of key supplemental categories until 2001, Aflac had years—really, decades—to compound its lead before serious competition arrived.

“Regulatory arbitrage” can sound like a cynical trick. Here, it was also a form of innovation. Aflac brought Japanese consumers a product domestic insurers weren’t offering at the time. The loophole created the opening, but Aflac still had to earn the right to stay.

Distribution as Competitive Advantage

Aflac reinvented distribution twice, and both reinventions mattered as much as the product itself.

In the U.S., the move to the worksite—voluntary benefits funded through payroll deductions—turned selling from a slog into a system. It lowered acquisition costs, improved persistency, and turned “insurance shopping” into an opt-in decision made in a trusted setting.

In Japan, the retired-worker sales force wasn’t a gimmick. It was cultural fit as strategy—credibility and comfort in conversations that demanded tact. Put simply: Aflac didn’t just translate its U.S. playbook. It built a new one.

And that’s why distribution became a moat. Competitors can copy policy features. They can’t quickly copy years of employer relationships, partner networks, and trust-based sales channels.

Marketing as Moat

The duck didn’t just make Aflac recognizable. It made Aflac memorable.

Before 2000, the company spent years doing what financial services marketing usually does: explaining, reassuring, sounding responsible. And almost nobody noticed. The duck flipped the equation. It made the name stick first—then let the product experience and agents do the explaining afterward.

The broader lesson isn’t “be funny.” It’s that in categories where products are complex and buying happens infrequently, attention is oxygen. And when attention is paired with a solid product, brand becomes a real competitive asset: people consider you first, trust you faster, and switch away more slowly.

Geographic Diversification—And Its Limits

Aflac went to Japan looking for diversification. It ended up with concentration.

Japan grew so successfully that it became the center of gravity—bringing exposure to currency moves, regulatory shifts, and demographics that a purely U.S. insurer didn’t have to worry about. That’s the tradeoff in international expansion: you can reduce dependence on one market, or you can discover you’ve found your main market.

Aflac managed that reality not by abandoning Japan, but by getting extremely good at operating there—treating the risk as something to manage through execution, not something to wish away.

Family Business Succession

Aflac also shows the upside of long-term stewardship.

The company’s strategy stayed unusually consistent across decades because leadership did. John Amos set the direction. Dan Amos carried it forward and scaled it. That continuity made it easier to do things that don’t pay off quickly—like building Japan over decades, or sticking with a distribution model that compounds slowly but powerfully.

Cultural Adaptation

Finally: Aflac won because it didn’t assume success was portable.

It adapted to Japan with local partnerships, a sales force that fit the culture, and even a duck that changed personality to match local sensibilities. The point wasn’t just respect—it was effectiveness. Aflac understood that what works in Columbus, Georgia might fail in Tokyo, and it built accordingly.

That combination—niche, regulation, distribution, brand, patience, and cultural fluency—is the real Aflac playbook. The duck just made it famous.

X. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

Aflac entered the mid-2020s with its two biggest advantages still standing: it owned the category in Japan, and it was unforgettable in the U.S.

Start with Japan. The same demographic story that’s a nightmare for traditional life insurers can actually help Aflac. An aging population means more years in which illness, incapacity, and serious diagnoses become statistically more likely. Cancer risk rises with age, and that keeps the core promise of Aflac’s supplemental “third-sector” products feeling relevant. In other words: Japan’s demographic headwind for some insurers can look like a tailwind for the kind of coverage Aflac specializes in.

Then there’s the brand. Aflac’s recognition sat above 90 percent in both major markets—an advantage that’s hard to overstate in insurance, where most products look similar and most buying decisions happen in a fog of confusion. You can copy benefits. You can’t quickly copy a household name that took decades and huge ad budgets to build.

Aflac has also proven it can survive rule changes that were supposed to kill it. When Japan deregulated in 2001 and the giants stampeded in, Aflac didn’t fall apart. It took a hit, then stabilized at still-dominant share. That’s a real signal that the moat wasn’t just regulation—it was what Aflac built while regulation bought it time.

Distribution is another quiet strength. Relationships with Japanese banks, post offices, and employers—and with American employers for worksite sales—don’t show up as a line item on the balance sheet, but they behave like one. They took decades to earn, and they’re not easily pried loose by a rival with a slightly cheaper policy.

Finally, digital transformation tends to reward scale. Aflac’s millions of policyholders generate the volume and data that make investments in automation and AI more worthwhile. When the marginal cost to serve the next customer drops, big incumbents can often widen the gap—assuming they execute.

The Bear Case

The risk, though, is that Aflac’s greatest strength is also a structural vulnerability: Japan.

Aflac isn’t “globally diversified” in the way the term is often used. In most years, Japan has produced more than two-thirds of earnings. That means a serious Japanese recession, a regulatory shift that disadvantages foreign insurers, or a major competitive breakthrough by domestic players wouldn’t just hurt results—it could reshape the whole company.

Then there’s currency. Yen weakness has repeatedly weighed on reported financials. Aflac can run a great business in Japan and still show slower growth in U.S.-dollar terms if the yen falls. Hedging can help, but it’s expensive and never perfect. Owning Aflac stock means, whether you intend to or not, you’re taking some exposure to the yen-dollar relationship.

Japan’s shrinking population is another long-term drag that no clever product tweak can fully erase. Fewer people means fewer potential customers. Aflac can raise revenue per customer with new products and pricing, but the total pool is contracting over time.

Competition is evolving, too. InsurTech entrants threaten the very thing Aflac historically used as a moat: distribution. Digital-first players can avoid legacy agent structures and try to reach customers more efficiently online. Aflac has invested heavily in digital tools, but incumbents often carry legacy costs that startups simply don’t.

And both of Aflac’s core markets are mature. In Japan, Aflac already insures roughly one in four households—there isn’t infinite room to push penetration higher. In the U.S., brand awareness is already above 90 percent—the hard work of becoming known is done. That means future growth has to come from product expansion, pricing, and share gains, which tend to be slower and harder than the earlier land-grab years.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: Low. Aflac’s key suppliers are reinsurers and technology vendors. Reinsurance is a competitive market, and Aflac’s scale gives it negotiating leverage. On the tech side, capabilities can be built internally or sourced from multiple vendors.

Buyer Power: Moderate. Individual policyholders don’t have much negotiating power, but large employers do. In the worksite model, employers act as gatekeepers to access individual customers.

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate to high. In Japan, Nippon Life and other domestic giants compete aggressively. In the U.S., the supplemental insurance space is crowded. As products converge, competition can show up through pricing, service, and distribution.

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate. Insurance is heavily regulated and capital-intensive, which creates meaningful barriers. But well-funded InsurTech startups can still enter with novel distribution models and a willingness to operate at thin margins.

Threat of Substitutes: Low to moderate. Japan’s national health system and U.S. employer health plans cover the basics, but they leave gaps. Supplemental insurance exists specifically to fill those gaps—yet in a squeeze, some consumers may decide to self-insure instead.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Present. With millions of policyholders, Aflac can spread fixed costs—especially technology and operations—over a larger base than smaller competitors.

Network Effects: Limited. Insurance doesn’t become more valuable because more people buy it.

Counter-Positioning: Historically important, but weaker today. Aflac’s early focus on supplemental insurance worked because incumbents dismissed the category. Once competitors entered, that specific advantage naturally faded.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Switching insurers is a hassle, and agent relationships can create loyalty. But at the end of the day, policies can be replaced.

Brand: Strong. The duck turned a hard-to-remember name into a reflex. That translates into consideration, trust, and often a willingness to pay. It’s a hard asset to replicate.

Cornered Resource: Limited. Aflac doesn’t rely on a single unique input competitors can’t access.

Process Power: Present. Decades of underwriting, claims processing, and distribution experience have produced operating know-how that isn’t easily copied quickly.

Key Performance Indicators

For anyone tracking how the story develops from here, three metrics matter most:

Japan New Annualized Premium Sales: This is the forward-looking growth engine in Japan. Because demographic trends are tough, holding this steady requires strong product design and distribution. Sustained declines can be an early warning sign of category slowdown or share loss.

U.S. Persistency Rate: This is retention—how many policies stay in force year after year. High persistency means predictable revenue and customer satisfaction. Falling persistency usually signals competitive pressure, pricing stress, or service issues.

Pre-Tax Operating Earnings by Segment: This shows profitability by geography without as much accounting noise. Watching the mix between Japan and the U.S. reveals whether concentration risk is easing—or intensifying—and whether one side of the business is quietly subsidizing the other.

XI. Epilogue & Strategic Outlook

So what comes next for a company that has already pulled off the kind of feats business books are built on? Aflac cracked Japan when Japan was supposed to be uncrackable. It turned a hard-to-pronounce acronym into one of the most recognizable sounds in American advertising. And it helped make supplemental insurance feel less like an afterthought and more like a basic part of financial protection.

The next decade is likely to be less about reinvention and more about endurance.

Japan still sits at the center of gravity. That’s a privilege and a constraint. It means Aflac will keep playing offense on product design—staying relevant in a society that’s aging faster than anywhere else—and defense on competition, where the big domestic players will never stop pressing. The flip side is the strategic imperative Aflac has been living with for years: the U.S. business needs to keep growing its share of the overall mix, not just for growth’s sake, but to reduce how much of the company’s fate depends on one foreign market.

Technology will be part of that. The pandemic proved that insurance doesn’t need to be sold, serviced, and administered face-to-face. Once customers experienced digital claims, digital service, and digital enrollment, they didn’t want to go back. Aflac has been investing in those capabilities, but it’s not alone—today, “digital transformation” is table stakes, not a differentiator.

One way to move faster is to borrow speed from the outside. InsurTech partnerships—and, potentially, acquisitions—offer a path to capabilities that incumbents often struggle to build quickly. Aflac has the cash generation and balance sheet strength to do deals. The harder question is choosing the right ones, and integrating them without smothering what made them valuable in the first place.

Then there’s the perennial question: do you go for a third geography?

China, India, and Southeast Asia are the obvious names—huge populations, growing incomes, insurance penetration that still has room to run. But Aflac’s own history is the cautionary tale. Japan wasn’t a quick win; it was decades of relationship-building, distribution work, and cultural adaptation. Expanding again would demand the same patient, long-horizon approach that made Aflac unusual in the first place.

And even if Aflac did expand, it raises another issue: leadership time horizon. A bet like Japan requires years of compounding before it looks “right” on a spreadsheet. Not every CEO—or board—has the appetite to start something that might not fully pay off on their watch.

The next “duck moment” is another open question. The original campaign worked partly because it was so unexpected: humor in financial services was rare, and mass media was concentrated enough that a single character could become ubiquitous. Today’s media environment is fragmented, and finance brands have learned the lesson—everyone is trying to be memorable. That doesn’t mean Aflac can’t find the next breakthrough. It just means the conditions that made the first one so explosive are harder to recreate.

ESG considerations will keep rising in importance, too. Expectations around sustainability, employee benefits, and governance have intensified across corporate America. Aflac has responded with sustainability initiatives, though its core supplemental niche is less directly exposed to climate-driven catastrophe risk than property and casualty insurers. The bigger ESG pressure may come through reputation, talent, and how benefits evolve as work and healthcare change.

And looming over all of it is the most human strategic question of all: succession.

Dan Amos has led Aflac for more than three decades, a stretch of continuity that’s rare in any public company, especially one operating across two radically different markets. The eventual transition—whether to another Amos or to professional management—will test whether the company’s culture and long-term orientation are truly institutional, or if they’ve been carried by the force of one leader.

If you were advising Aflac’s board, the to-do list would probably sound almost boring: protect the Japan franchise through continued innovation, keep pushing U.S. growth to dilute concentration, invest in technology to defend against digital disruption, and get serious about leadership transition planning. None of that promises another lightning strike like the duck. But that’s what mature excellence looks like—less about chasing glory, more about refusing to lose what you’ve earned.

The Amos brothers who scraped together $300,000 in 1955 couldn’t have imagined what they were starting. The duck that quacked into America’s living rooms in 2000 became bigger than the product it advertised. And the Japan strategy that looked reckless in 1970 became a case study in how to cross cultures, navigate regulation, and build trust the slow way.

Aflac’s story is proof that you can build durable advantage in a business many people write off as commoditized; that cultural barriers can be crossed with patience and partnership; and that marketing innovation can be as powerful as product innovation. For investors, it’s also a reminder that the most impressive compounding often happens quietly—through consistent execution, disciplined capital allocation, and a relentless focus on distribution and claims-paying trust.

The duck that built an empire is still quacking—across two languages, two cultures, and into its seventh decade.

XII. Recent Developments

Aflac’s fourth-quarter 2024 results looked like what you’d expect from a mature leader: not a dramatic reinvention, but steady execution. For the full year, the company reported $19.12 billion in revenue, with strength coming from both sides of the business. Japan still produced the bulk of earnings, while the U.S. segment continued to add a bit more balance to the overall mix.

Management kept pointing to the same levers Aflac has been pulling for years—digital capabilities and distribution partnerships—because, in insurance, those are the compounding engines. In Japan, Aflac refreshed its lineup with updated cancer and critical illness products aimed at customers navigating an aging society. In the United States, the company continued pushing into the small and mid-sized business market, a segment where expanding worksite access can still move the needle.

Investors, meanwhile, stayed focused on currency. A weaker yen against the dollar pressured translated results from Japan, even as performance in local currency held steady. Management highlighted hedging efforts and the built-in partial offset that comes from having both yen-denominated revenues and yen-denominated expenses.

Competition in Japan kept evolving, too—not just through head-to-head product battles, but through consolidation. Smaller domestic insurers merged or stepped back, reshaping the field around a few large players. Through it all, Aflac held its position as the leading name in cancer and supplemental health, with roughly half of the cancer insurance market—essentially unchanged from prior periods.

And the shareholder-return story kept marching forward. Aflac continued returning capital through dividends and share repurchases, and its dividend growth streak moved beyond four decades—one of the reasons it sits in the “Dividend Aristocrat” club, reserved for companies that have raised payouts for at least 25 consecutive years. In plain English: management was signaling it still believed the business could reliably throw off cash, even in a slower-growth, higher-competition world.

XIII. Sources & Further Reading

Company Filings - Aflac Incorporated Annual Reports (Form 10-K), 2020–2024 - Aflac Incorporated Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q) - Investor presentations and earnings call transcripts - SEC filings (EDGAR): sec.gov/cgi-bin/browse-edgar?company=aflac

Long-Form Articles and Research - “How a Georgia Insurance Company Conquered Japan,” Fortune, various issues (1990s–2000s) - “The Aflac Duck at 20: How a Quacking Mascot Transformed an Insurance Company,” Advertising Age retrospective - International Company Histories, Vol. 67: Aflac Incorporated profile - “Supplemental Insurance in Japan: Market Structure and Competitive Dynamics,” academic research papers

Books and Industry References - Industry histories covering the rise of supplemental insurance in the United States - Analyses of foreign-company success in Japanese markets - Marketing case studies on the Aflac duck campaign

Regulatory and Government Sources - Japan Financial Services Agency reports on the insurance industry - National Association of Insurance Commissioners publications on supplemental insurance - Trade agreement documentation covering U.S.–Japan insurance market negotiations

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music