Amgen: The Biotechnology Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

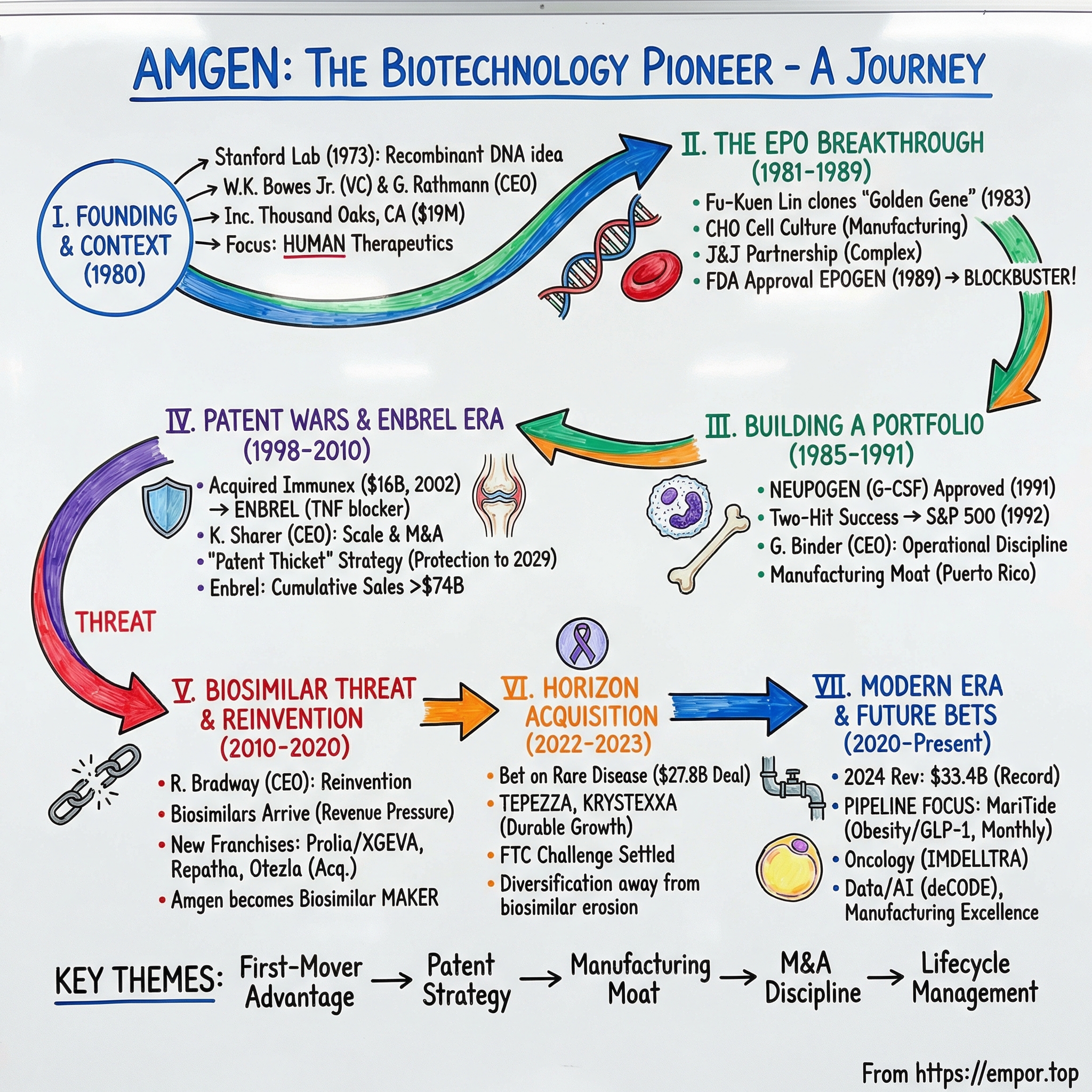

Picture the sun-drenched hills of Thousand Oaks, California. It’s hard to imagine a medical revolution starting here, in what looks more like quiet suburbia than the front line of scientific progress. But this is where Amgen grew from a sketch on a term sheet into one of the world’s most influential biotechnology companies.

By 2024, Amgen ranked as the eighteenth-largest biomedical company globally by revenue, with $33.4 billion in sales. Yet in 1980 it was just a contrarian wager: that recombinant DNA could be turned into medicines the world simply couldn’t make any other way.

If you want proof that bet paid off, start with what’s driving the business today. Prolia and XGEVA, which help protect and strengthen bone in osteoporosis and in certain cancer settings, brought in $6.7 billion in 2024. Enbrel, a cornerstone therapy for rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases, delivered $3.3 billion. And Repatha, which lowers LDL cholesterol by targeting PCSK9, added $2.3 billion.

These aren’t small tweaks to existing drugs. They’re biologics: therapies built from proteins, produced inside living cells, and designed to intervene in human biology in ways traditional chemistry often can’t touch.

So how did a biotech startup become the first to create a blockbuster biologic? How did it survive patent wars where the outcome didn’t just decide Amgen’s future, but who would control entire drug categories? And how did a company that once rode two breakthroughs—Epogen and Neupogen—keep reinventing itself as exclusivity expired and biosimilars threatened to turn yesterday’s miracles into tomorrow’s commodities?

That’s the arc of this story. It’s about first-mover advantage in an industry where being early can mean everything. It’s about a patent strategy so relentless that Enbrel will likely remain protected for more than three decades after its initial approval. It’s about M&A judgment—knowing when to walk away, and when to pay up, including a $27.8 billion deal for Horizon Therapeutics. And it’s about a less glamorous truth: in biotech, manufacturing isn’t a back-office detail. The ability to reliably grow proteins at enormous scale can be as decisive as discovering them.

Amgen’s journey—from a $19 million venture bet to a company with Enbrel sales that could approach $100 billion by 2029—isn’t just a corporate success story. It’s a playbook for building moats in a world where a single molecule can be worth more than entire industries.

II. The Biotech Revolution & Founding Context

This story doesn’t start in Thousand Oaks. It starts in a Stanford lab in 1973, when Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer cracked a problem that instantly changed the ceiling on what medicine could be: they figured out how to splice genes from one organism into another. Recombinant DNA had arrived. And with it came a once-absurd idea that suddenly felt practical—engineer living cells to manufacture human proteins.

A few years later, Boyer and venture capitalist Robert Swanson turned that idea into a company: Genentech. Legend has it the entire industry began with a handshake and $500 each.

By the late 1970s, the implications were impossible to ignore. Genentech showed that bacteria could be taught to produce human insulin. If you could do that, maybe you could do almost anything—make hormones, growth factors, immune signals, proteins that normally exist in the body in vanishingly small amounts. But “maybe” did a lot of work back then. Nobody knew which proteins would become real therapies, how to manufacture them reliably, how to scale production without breaking the biology, or how the FDA would even think about approving a drug made inside genetically engineered cells.

That uncertainty is exactly what attracted William K. Bowes Jr., a San Francisco venture capitalist with a sharp eye for platform shifts. Bowes had missed Genentech’s founding—something he didn’t forget—and he wasn’t going to miss the next wave. So he began assembling the pieces: capital, scientific credibility, and a board of advisors who could separate promising targets from beautiful dead ends.

On April 8, 1980, Applied Molecular Genetics Inc.—AMGen—was incorporated in Thousand Oaks, California. The name was clinical, almost timid. The ambition wasn’t. And the location wasn’t an accident either: nearby sat UCLA, the California Institute of Technology, and UC Santa Barbara—three dense clusters of molecular biology talent within easy reach.

Bowes’ scientific advisory board read like a map of the field’s frontier. Norman Davidson, the Caltech biochemist known for pioneering DNA mapping. Leroy Hood, whose lab would later help usher in automated DNA sequencing. Marvin Caruthers, who invented the chemical synthesis of DNA. Arnold Berk, a leading UCLA virologist. Along with them were John Carbon, Robert Schimke, Arno Motulsky, and Dave Gibson—serious scientific horsepower from day one.

The company launched with $19 million from a private-equity placement backed by venture capital firms and two major corporations. For 1980, that was real runway—enough to hire talent, build labs, and pursue multiple shots on goal before needing to go back to the market.

But money and advisory boards don’t build drugs. Amgen still needed the hardest-to-find ingredient in early biotech: a CEO who could translate molecular biology into approved products, and do it under the unforgiving constraints of regulation, manufacturing, and time.

In October 1980, Amgen found that person in George Rathmann, its first president and chief executive officer. Rathmann wasn’t the archetype of a venture-backed startup leader. He was fifty-three, a seasoned Abbott Laboratories executive who’d spent two decades moving up to vice president for research and development in Abbott’s diagnostics division. He understood what it took to run science like an operating system: pick a strategy, build processes, hit milestones, and scale. He also brought something Amgen desperately needed—instant credibility with scientists, investors, and potential pharmaceutical partners.

Rathmann’s thesis was simple and specific: Amgen would use molecular biology to make human therapeutics. Not research tools. Not industrial enzymes. Not agricultural side quests. Human medicines. That focus mattered, because plenty of early biotechs tried to be everything at once—and ended up spreading themselves thin in an industry where each experiment is expensive and each failure teaches you slowly.

Amgen began operations in 1981 in a small facility near the Conejo Valley. The team was tiny, the projects were many, and the to-do list was endless. Early work ranged from chicken growth hormone—an echo of biotech’s agricultural promise—to hepatitis B vaccines and other human proteins.

But before long, two targets began to dominate the company’s attention. And one of them would become the breakthrough that turned Amgen from a promising startup into the first biotech to produce a true blockbuster.

The timing helped. 1980 was a hinge year for American innovation. The Bayh-Dole Act had just opened the door for universities to patent federally funded discoveries, pulling academic research toward commercialization. The FDA was cautiously receptive to biotechnology’s promise. And investors, coming off the semiconductor boom, were hunting for the next technology that could remake the economy.

Amgen’s founding also offers a few patterns that show up again and again in this industry. Proximity to top universities isn’t a perk; it’s a supply chain for talent and ideas. Management quality often determines whether great science becomes a product. And in high-risk R&D, focus isn’t just strategy—it’s survival.

III. The EPO Breakthrough: Finding the Golden Gene (1981–1989)

In a cramped lab in Thousand Oaks, a young scientist named Fu-Kuen Lin took on a job that bordered on ridiculous. His mission was to find and clone the gene for erythropoietin—EPO—the hormone that tells the body to make red blood cells.

The catch was that EPO barely exists in nature. One way to describe the challenge is almost absurd: there was only about 50 milligrams of EPO in all the blood ever collected by all the blood banks in the world. So Amgen wasn’t trying to purify a protein. They were trying to find the instructions for it—one gene hidden in a vast genome—without a clear map, and with the clock ticking.

Lin had emigrated from Taiwan for his doctorate in biochemistry, and he combined technical creativity with a kind of stubborn endurance that early biotech demanded. The plan was to build a “library” of human DNA fragments, insert those fragments into bacteria, and then screen the resulting bacterial colonies to find the one that carried the EPO gene. That screening step was the killer: no one could simply look for a known sequence, because they didn’t know exactly what they were looking for.

For two years, Lin and his team pushed through the grind—hundreds of thousands of colonies, endless false leads, long stretches where progress felt imaginary. And this wasn’t an academic puzzle. Genetics Institute was chasing the same prize, and the stakes were existential. Whoever got there first stood to control a therapy that could transform care for patients with kidney disease, many of whom suffered debilitating anemia and relied on repeated blood transfusions because there was no good alternative.

In 1983, Amgen hit paydirt. Lin’s team isolated the EPO gene—the critical first step toward producing the hormone at scale. It was the kind of breakthrough that, in hindsight, looks inevitable because the industry was moving in that direction. At the time, it was a moon landing.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Just months earlier, on June 17, 1983, Amgen had gone public, raising nearly $40 million. That IPO money mattered because gene cloning was only the beginning. Turning EPO into a drug would require years of expensive development, process engineering, and clinical work. But the discovery also did something even more important: it made the bet real. Investors weren’t funding a theory anymore. They were funding a specific molecule with a clear medical need and a credible path to a product.

Then came the next hard lesson of biologics: finding the gene doesn’t mean you can manufacture the protein. Bacteria—the early workhorse of genetic engineering—couldn’t do the job. EPO required modifications that bacteria couldn’t reliably produce. So Amgen had to master mammalian cell culture, particularly Chinese hamster ovary, or CHO, cells. Today, CHO is synonymous with biologics manufacturing. In the mid-1980s, it was finicky, temperamental, and far from standardized. Amgen was building the plane while learning how to fly it.

At the same time, the company struck a complex licensing deal with Johnson & Johnson. Amgen kept U.S. rights for dialysis patients. J&J would handle international markets and non-dialysis indications in the U.S. That partnership brought needed resources and deep commercial and regulatory experience—but it also baked in ambiguity. Where, exactly, did one territory end and the other begin? That question would later trigger years of disputes.

And of course, the FDA process was its own crucible. The agency had limited precedent for approving a recombinant protein therapeutic for a major chronic disease. Clinical data were compelling—dialysis patients who had been dependent on transfusions began making their own red blood cells, with meaningful improvements in energy and quality of life. But between those results and an approval letter sat an enormous amount of scrutiny: manufacturing consistency, long-term safety, dosing protocols, and the simple reality that the FDA was writing parts of the rulebook as it went.

While regulators deliberated, the courtroom lights came on. Genetics Institute had also cloned EPO using a different approach, and both companies claimed the intellectual property. What followed became one of biotech’s defining patent fights—less about who had the better science, and more about what it even meant to “own” a recombinant version of a human hormone when multiple teams reached the same destination by different routes.

On June 1, 1989, the FDA approved EPOGEN for anemia associated with chronic renal failure. Amgen had won the race to the market. Genetics Institute’s product did not receive approval, and the patent fight ultimately broke Amgen’s way. Lin’s long, monotonous two-year search had become the foundation of a franchise—and, just as importantly, a proof point that the entire biotech industry could point to when skeptics asked whether recombinant medicines would ever be more than a lab trick.

The EPOGEN saga also revealed the rules of the game investors would come to recognize. In pharmaceuticals, being first to approval can matter more than being merely good—especially when the market rewards scale and trust. Manufacturing is not a detail; it’s a moat. And partnering with a giant like J&J can accelerate you, but it can also bind you into agreements that become battles later.

EPOGEN went on to become the first biotech blockbuster, racing to the billion-dollar sales milestone faster than any drug in history. It validated recombinant proteins as not just medically powerful, but commercially massive. And for Amgen, it did what every great first product does: it didn’t end the story. It funded the next one.

IV. Building a Portfolio: Neupogen and the Second Act (1985–1991)

Even as Fu-Kuen Lin’s team chased EPO, Amgen was already lining up its next big swing. Another early Amgen scientist, Larry Souza, was going after granulocyte colony-stimulating factor—G-CSF—a protein that tells the body to produce neutrophils, the white blood cells that serve as a first-line defense against bacterial infection.

The clinical problem here was brutally clear. Chemotherapy could shrink tumors, but it also wiped out immune cells. Patients would crash into neutropenia—dangerously low neutrophil counts—then end up battling infections their bodies couldn’t fight. Doctors faced an ugly set of tradeoffs: delay chemo, lower the dose, or push ahead and hope complications didn’t turn lethal. A drug that could help the body rebuild neutrophils faster wouldn’t just be helpful. It would change how cancer treatment could be delivered.

Souza’s team cloned G-CSF and turned it into NEUPOGEN (filgrastim). On February 21, 1991, the FDA approved NEUPOGEN to decrease the incidence of infection in patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Amgen now had something no early biotech could take for granted: not one hit, but two. Two major biologics aimed at urgent, high-stakes medical needs—each difficult to make, each hard for would-be competitors to copy.

This second approval also landed in the middle of a leadership handoff that set the tone for Amgen’s next phase. Gordon Binder had joined in 1982 as chief financial officer—one of the early builders who put structure around a company that, like most startups, began as more ambition than infrastructure. In 1988, he succeeded George Rathmann as CEO, taking over just as Amgen’s science started turning into real revenue.

Binder was not the stereotypical biotech chief. He wasn’t a career scientist; he had a Harvard MBA and experience at Ford Motor Company and Litton Industries. Rathmann had been the credibility bridge from pharma into biotech. Binder’s edge was operational discipline—how you scale, how you build systems, and how you turn a breakthrough into a business that can keep delivering products, year after year.

With EPOGEN and NEUPOGEN together, Amgen created a financial flywheel. In 1991, combined sales from the two drugs reached $1 billion, a milestone that didn’t just validate Amgen—it validated the entire biotech model. Soon after, the company was no longer a promising upstart. On January 2, 1992, Amgen was added to the S&P 500, the first pure-play biotechnology company to make it into the index. Months later, it debuted on the Fortune 500 list. Twelve years after starting with $19 million, it had achieved something close to establishment status.

And Binder made a bet that would become one of Amgen’s defining strengths: manufacturing. The company built a major production facility in Puerto Rico, benefiting from tax incentives while adding redundancy to its supply chain. In biologics, manufacturing isn’t a commodity function. It’s a high-wire act—living cells that have to be kept healthy, fed correctly, and protected from contamination. A single batch failure can be catastrophically expensive. Getting consistently good at making proteins at scale is its own form of R&D, and Amgen treated it that way.

NEUPOGEN also showed how to compound a discovery. The initial approval was for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, but additional approvals followed—for patients undergoing bone marrow transplants, patients receiving bone marrow-suppressive therapies, and patients with severe chronic neutropenia. Each new indication expanded the market without requiring a new molecule. It was a portfolio-building tactic hiding in plain sight, and Amgen would lean on it again and again.

None of this meant the company was risk-free. Two-product concentration is great until one product stumbles. The Johnson & Johnson partnership constrained EPOGEN’s market reach. And, eventually, patents expire and competition shows up—especially once biosimilars enter the picture. But in the early 1990s, those clouds were still over the horizon. From the outside, Amgen looked unstoppable: the first biotechnology company to reach sustainable profitability, and the clearest proof that recombinant proteins could become not just medicines, but franchises.

The bigger question was the one that haunts every great first act. Amgen had proven it could discover and launch blockbuster drugs. Could it keep innovating once the obvious targets were taken, the easy growth slowed, and competitors got smarter—both in the lab and in the courtroom?

V. The Patent Wars & Enbrel Era (1998–2010)

On November 2, 1998, the FDA approved Enbrel (etanercept) for moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Mechanistically, it couldn’t have been more different from EPOGEN or NEUPOGEN. Enbrel blocked tumor necrosis factor, or TNF, a key signal that fuels runaway inflammation in autoimmune disease. For patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and later psoriasis and other inflammatory conditions, it wasn’t just another option—it was the first time many people experienced real relief when older therapies had hit a wall.

But here’s the twist: Amgen didn’t own Enbrel.

Enbrel was developed by Immunex, a Seattle biotechnology company that helped pioneer TNF research. Immunex had the science, and it had demand. What it didn’t have was enough product. Manufacturing scale-up proved painfully hard, leading to persistent supply shortages that left physicians and patients waiting.

That gap—world-class biology paired with operational strain—was exactly the kind of situation Amgen knew how to exploit.

In July 2002, Amgen completed its acquisition of Immunex for about $16 billion, the largest biotech merger ever at the time. The deal delivered Enbrel, a manufacturing plant in Rhode Island, and an inflammation-focused R&D pipeline. And Amgen moved fast. Within months, teams secured FDA approval for expanded manufacturing capacity, ramped production across its network, and started clearing the backlog of unmet demand.

Suddenly, Amgen wasn’t a two-franchise company anymore. It had four existing or potential blockbusters in the same lineup: EPOGEN, NEUPOGEN, Aranesp (a longer-acting next-generation erythropoietin), and Enbrel. Just as importantly, Enbrel pulled Amgen into inflammation—an arena with enormous markets, chronic use, and the potential for decade-long patient relationships. The Immunex deal also crystallized a strategy that would define Amgen’s next era: buy proven assets where the science is already validated, then use Amgen’s manufacturing and commercial machine to unlock the value.

This was Kevin Sharer’s moment. Sharer had taken over as CEO in 2000, after joining Amgen in 1992 as president and chief operating officer, with prior experience at MCI Communications and General Electric. He paired Binder’s operational discipline with a bigger appetite for scale—acquisitions, integration, and international expansion.

Still, the most remarkable part of the Enbrel story wasn’t that Amgen bought it. It was how long Amgen managed to keep it.

Through a mix of aggressive patenting, high-stakes litigation, and favorable legal turns, Amgen positioned Enbrel to remain protected until 2029—more than three decades after its first approval. The playbook was the “patent thicket”: not one key patent to challenge, but a layered stack across the drug’s composition, its manufacturing process, formulation, and methods of administration. Any would-be biosimilar competitor didn’t just need to prove similarity in a lab and to regulators; it had to fight its way through a maze of claims, each one capable of dragging disputes out for years. Amgen also added patents tied to later discoveries about Enbrel’s mechanism and uses, extending protection well beyond the original set.

The economic payoff has been enormous. By 2024, cumulative Enbrel sales had topped $74 billion, and projections suggested it could approach $100 billion in lifetime revenue by the time meaningful biosimilar competition finally arrives in 2029. One molecule—discovered by another company—became a generational cash engine, defended as much by legal architecture as by biology.

That success came with a controversy that never really went away. Critics argued these tactics delayed lower-cost alternatives and kept prices higher than they otherwise would have been. Defenders argued that strong IP protection is what makes it rational to fund risky, expensive biomedical innovation in the first place. Whichever side you take, the outcome for Amgen was clear: Enbrel became the company’s longest-lasting, highest-earning product.

Around Enbrel, Sharer built a broader inflammation franchise—investing in TNF biology, related pathways, and the capabilities needed to compete in immunology long term. Amgen also kept expanding the manufacturing footprint, adding major facilities in places like Ireland and Singapore alongside its U.S. operations. Puerto Rico, in particular, grew into one of the world’s largest biologics manufacturing sites—reinforcing the pattern that had been true since EPOGEN: if you can’t make the drug reliably at scale, you don’t really have the drug.

For investors, Enbrel is a masterclass in what “moat” can mean in pharma. A well-managed patent estate can last far longer than the simplistic “twenty years” mental model. Biologics manufacturing complexity can be a barrier even when patents weaken, because biosimilar makers must prove they can match not just the molecule, but the process. And operational excellence—turning scarce supply into steady global production—can create more value than the original discovery itself.

But Enbrel also set a trap. The better Amgen got at extending and monetizing the franchise, the more the company came to depend on it. Even with a patent thicket, 2029 was a date on the calendar. And Amgen would need new engines of growth before the Enbrel era finally ran out.

VI. The Biosimilar Threat & Reinvention (2010–2020)

By the early 2010s, Amgen had a problem that every great biotech eventually faces: time was catching up to its best inventions.

In May 2012, Robert A. Bradway became Amgen’s president and chief executive officer, succeeding Kevin Sharer after a long run of expansion and wins. Bradway was a Princeton-educated MBA who’d joined Amgen in 2006 as chief financial officer, and he stepped into the job with a clear view of what was coming. The patents underpinning the company’s founding franchises—EPOGEN and NEUPOGEN—were aging out. A new U.S. regulatory pathway for biosimilars was now real. And while Amgen still had a pipeline, it didn’t have an obvious “next Epogen” waiting in the wings.

The biosimilar threat wasn’t theoretical. For small-molecule drugs, generics can be chemically identical copies. Biologics don’t work that way. They’re made in living cells, and even tiny changes in process can shift the final product. That’s why biosimilars are approved as “highly similar” rather than identical. But the commercial impact can still be brutal, because the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 created a pathway that let competitors lean on the original drug’s clinical foundation. You didn’t have to re-prove everything from scratch. The barriers were still high—but they were suddenly climbable.

Bradway’s answer was reinvention, not denial. And it happened on several fronts at once.

First, Amgen pushed hard into new franchises with big addressable markets. Prolia (denosumab) and XGEVA, both approved in 2010, went after bone disease by blocking RANK ligand, a key driver of bone breakdown. Prolia targeted osteoporosis, a massive and growing need. XGEVA focused on preventing bone complications in cancer patients. Together, these drugs gave Amgen a new growth engine—one that would eventually become a multibillion-dollar franchise.

Second, Amgen made a major bet on cardiovascular disease by entering the PCSK9 race. Repatha (evolocumab), approved in 2015, aimed at patients who couldn’t get LDL cholesterol low enough with statins alone, or who couldn’t tolerate statins at all. The science was powerful: deep LDL reductions from a novel mechanism. The business story was bumpier at first—pricing controversy, payer pushback, slower-than-hoped adoption—but Repatha kept compounding and grew into a meaningful pillar of the portfolio.

Third—and this was the move that signaled Bradway really understood the new rules—Amgen decided to become a biosimilar company itself. If biosimilars were going to come for Amgen’s older products, Amgen would also compete in the market that was doing the cannibalizing. The company developed biosimilars to blockbuster biologics from rivals, including products like Roche’s Avastin and Herceptin and AbbVie’s Humira. Strategically, it was a hedge and a new revenue stream at the same time: a way to benefit from the biosimilar wave rather than just endure it.

Then, in 2019, Amgen pounced on a rare kind of opportunity: a high-quality asset forced onto the market by industry consolidation. Bristol Myers Squibb, in the process of merging with Celgene, divested Otezla for $13.4 billion. Amgen bought it. Otezla, an oral treatment for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, expanded the inflammation franchise with a mechanism distinct from Enbrel—working inside cells rather than targeting extracellular signals. Just as important, the deal showed Amgen could still move quickly and decisively when the right product appeared at the right moment.

Across the decade, Amgen also broadened its footprint in neuroscience, cardiovascular disease, and oncology through internal R&D and smaller acquisitions. And, quietly but relentlessly, it kept investing in manufacturing—because in biologics, quality and reliability aren’t just compliance issues. They’re competitive advantages. Building biosimilars, in particular, demanded new muscle: the ability to match the intricate characteristics of drugs Amgen didn’t invent, using processes Amgen didn’t design.

Bradway’s style contrasted with the leaders who came before him. Rathmann had provided early biotech credibility and focus. Sharer had leaned into scale and big deals. Bradway brought a CFO’s discipline to a company that now needed to win in a more mature, more competitive industry. He emphasized capital allocation, portfolio prioritization, and returns—being willing to walk away when a deal didn’t fit, and to spend when the strategic logic was strong.

For investors, the 2010s were a live-fire test of Amgen’s business model. Biosimilar competition did arrive for NEUPOGEN and earlier ESAs, and revenue pressure followed. But Amgen proved it could replace what was fading: newer franchises like Prolia/XGEVA, Repatha, and Otezla grew into the gaps. And the biosimilars strategy added a kind of optionality that few incumbents managed well—Amgen could participate in the growth of biosimilars even as it defended its own portfolio.

Still, the reinvention wasn’t the end of the story. Enbrel’s protection, however formidable, had a clock on it. New mega-markets—like obesity—were forming into the industry’s next battleground without Amgen at the center. And larger competitors were doubling down on biologics, raising the intensity across Amgen’s core therapeutic areas.

Amgen had adapted. But it still needed its next truly transformative move.

VII. The Horizon Acquisition: Betting Big on Rare Disease (2022–2023)

In the autumn of 2022, Amgen’s deal team started taking a hard look at Horizon Therapeutics, a Dublin-headquartered biopharmaceutical company that had quietly built something Amgen wanted more of: durable growth, in niches where competition is thin and pricing pressure is often lower.

Horizon’s portfolio was concentrated but distinctive. TEPEZZA treated thyroid eye disease. KRYSTEXXA targeted uncontrolled gout in patients who’d run out of options. UPLIZNA served a rare neurological condition. These were specialized medicines with premium economics and, crucially, limited direct competition. Horizon was growing fast—but it didn’t have the kind of global commercial and operating infrastructure that Amgen had spent decades building.

Amgen also wasn’t the only one who noticed. Johnson & Johnson and Sanofi were circling too. A bidding process followed, and in December 2022 Amgen won with an offer of $116.50 per share in cash—about $27.8 billion in equity value. It was an expensive deal, priced at roughly eight times Horizon’s 2022 revenues. Amgen’s bet was that rare disease assets could deliver long runway growth with less exposure to the biosimilar wave that had been steadily creeping toward its older franchises.

Then the FTC stepped in.

In May 2023, the Federal Trade Commission filed a complaint in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois to block the acquisition. This wasn’t the usual antitrust story about two competitors combining. The FTC’s theory centered on bundling: the concern that Amgen could use its contracting leverage—through relationships and rebate dynamics—to pressure payers in ways that could disadvantage Horizon’s competitors.

The case rattled the industry. If regulators could derail a deal based not on clear overlap, but on predictions about what a buyer might do in the future, it introduced a new kind of uncertainty into large pharma M&A. Amgen pushed back forcefully, arguing the theory was unprecedented and unsupported by evidence.

After months of legal sparring, Amgen and the FTC reached a settlement that let the deal go through—with strings attached. Amgen agreed not to bundle Horizon products with its existing portfolio in ways that disadvantaged competing rare disease treatments, and it accepted contracting and pricing restrictions intended to address the FTC’s concerns. On October 6, 2023, Amgen completed the acquisition of Horizon Therapeutics.

Strategically, the logic was about more than just adding revenue. Rare disease drugs often enjoy longer effective exclusivity because small patient populations can make biosimilar development less attractive economically. TEPEZZA, in particular, stood out: it had no direct competitors and effectively defined a new therapeutic category for thyroid eye disease. KRYSTEXXA, while not entirely alone, dominated a severe corner of the gout market where patients had failed other treatments.

By the next year, the numbers supported the thesis. In 2024, TEPEZZA generated $1.9 billion in sales, KRYSTEXXA brought in $1.2 billion, and UPLIZNA added $379 million. In aggregate, the Horizon portfolio contributed nearly $3.5 billion in revenue—real diversification that reduced Amgen’s dependence on any single product or therapeutic area.

The Horizon deal also showed how Amgen’s M&A playbook had matured. The Immunex acquisition had been about taking a breakthrough product that the seller couldn’t manufacture at scale—and using Amgen’s operational machine to unlock demand. Horizon was different. This time, Amgen was buying commercial-stage assets with built-in competitive advantages and minimal overlap with the existing portfolio. The premium reflected how scarce those assets are, and how many large pharma companies are chasing the same kind of insulation from patent cliffs and biosimilar erosion.

For investors, the deal cut both ways. Paying $27.8 billion was a major capital allocation decision that assumed continued growth and smooth integration. The FTC challenge highlighted a regulatory risk that now has to be part of the M&A calculus, even when product overlap is limited. And the pivot toward rare disease pulled Amgen further from the large-population biologics markets where its scale and manufacturing prowess had historically been the sharpest weapons.

But it also underscored something important about Amgen under Bradway: the company was willing to pay up when it found quality. Rare disease markets can be structurally less vulnerable to biosimilars. Pricing power tends to be stronger when alternatives are limited. And these were still complex, specialty medicines—closer to Amgen’s core capabilities than the commodity dynamics of small-molecule generics.

Amgen had spent a decade learning to live with the biosimilar era. Horizon was the move that tried to outrun it.

VIII. Modern Era: Pipeline & Future Bets (2020–Present)

The 2024 numbers tell a pretty clean story: Amgen was still growing, and it was doing it at scale. Total revenue rose 19% to a record $33.4 billion, fueled by higher volumes across the portfolio. This wasn’t one product suddenly catching fire. It was the compounding effect of a decade of choices—Prolia and XGEVA continuing to expand, Repatha steadily finding more patients, Otezla holding its place in psoriasis, and Horizon’s drugs showing up for a full year under Amgen’s ownership.

But the market’s real obsession sat in the pipeline. One molecule, still unapproved, had the power to reshape how investors thought about Amgen’s next decade: MariTide.

MariTide is an investigational injectable obesity drug designed for monthly—or potentially less frequent—dosing. It targets both GIP and GLP-1 receptors, the same core biology behind today’s category leaders like Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro and Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy. In Phase 2, MariTide showed strong weight loss at 52 weeks, and notably, weight loss that continued rather than flattening into an obvious plateau. Add in the convenience of monthly dosing versus weekly injections, and you can see the appeal: if it works in Phase 3, it’s not just “another GLP-1.” It’s a product with a potential compliance and convenience advantage.

That’s why the stakes feel so high. The obesity and diabetes market is widely expected to become enormous over the next decade, powered by drugs that have proven they can deliver meaningful, sustained weight loss. If MariTide’s profile—continued weight loss, improved cardiometabolic measures, and less frequent dosing—holds up in Phase 3 and clears regulators, Amgen would have a credible shot in what could become the biggest commercial drug market the industry has ever seen.

Obesity isn’t the only frontier. Amgen has also been leaning hard into oncology, especially newer immune-based modalities. IMDELLTRA, a bispecific T-cell engager in small cell lung cancer, is a good example of where the science is going: engineer a protein that effectively links a cancer cell to a T-cell and forces the immune system to pay attention. If the platform works, it’s not a one-off drug. It’s a way to build a pipeline—more bispecifics, more targets, more shots on goal.

Meanwhile, the biosimilars strategy has matured from “defense” into a business line with real weight. Amgen has launched biosimilar versions of major biologics like Humira, Avastin, and Herceptin across multiple markets. The logic is elegant: if biosimilars are going to compress pricing power across the industry, Amgen would rather be one of the companies doing the compressing than only the one being compressed. Decades of manufacturing experience—arguably Amgen’s most durable advantage—translate unusually well here.

On the R&D side, Amgen has also pushed deeper into computation and AI. deCODE Genetics, the Icelandic genetics company it acquired, gives Amgen access to rich datasets linking genetic variation to disease risk—useful for picking better drug targets and designing smarter trials. Machine learning has started to show up across the organization too, from antibody optimization to process engineering to development planning. None of this is a guaranteed revenue driver on its own, but it’s part of a broader shift: drug discovery is becoming more data-driven, and Amgen doesn’t want to be late to that change.

And then there’s the unglamorous engine underneath all of it: manufacturing. Amgen has kept upgrading how it makes biologics—newer bioreactors, more continuous processes, better purification, higher yields. Its global network spans California, Rhode Island, Puerto Rico, Ireland, and Singapore, giving it both redundancy and the capacity to scale as the portfolio grows. In biologics, this isn’t just about cost. It’s about reliability, speed, and the ability to serve demand when others can’t.

Of course, the competitive landscape hasn’t gotten any easier. In obesity, Amgen is up against Lilly and Novo, plus a swarm of companies chasing improved GLP-1s, oral versions, and combination therapies. In inflammation, the long shadow of Enbrel’s eventual competition keeps getting closer, and newer classes like JAK inhibitors have changed how physicians treat rheumatoid arthritis. In oncology, every promising modality attracts a crowd—bispecifics, antibody-drug conjugates, and cell therapies are all packed fields.

So this is the modern Amgen: a company in transition, again. The older franchises still throw off cash, but the long-term direction is down as competition and time do what they always do. The newer pillars—Prolia/XGEVA, Repatha, Otezla, and the Horizon drugs—are growing, but they’re growing in a world that’s more price-sensitive and more crowded than the one Epogen entered. And the future-defining bets—MariTide, IMDELLTRA, and the rest of the pipeline—carry massive upside, but also the basic truth of biotech: until Phase 3 works and regulators agree, nothing is real.

For investors trying to answer whether Amgen is still an innovator at heart or gradually becoming a manager of aging franchises, the most telling thing to watch is organic growth—what happens when you strip out acquisitions and currency noise. That number is the signal. It tells you whether Amgen is still generating new momentum from within, or whether the next chapter will depend on buying it.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Amgen’s forty-five-year run—from a venture-backed experiment in recombinant DNA to a global biotech heavyweight—reads like a field guide for how to build endurance in an industry where yesterday’s breakthrough is always one patent expiration away from becoming a commodity.

First, first-mover advantage in biotech isn’t just a head start. It’s compounding. Getting to EPOGEN and NEUPOGEN early didn’t merely create two products; it created the cash, credibility, and organizational confidence to invest in the next wave—bigger manufacturing, broader R&D, and later, acquisitions like Immunex and Horizon. In markets shaped by physician familiarity, payer contracts, and the practical friction of switching therapies, the company that arrives first often stays in front far longer than you’d expect.

Second, patent strategy is business strategy. Enbrel is the clearest example: the value wasn’t only in the biology, but in how Amgen built and defended a layered IP estate—across the molecule, the manufacturing process, formulation, and methods of use. In pharmaceuticals, it’s not enough to invent. You also have to architect protection in a way that survives real-world challenges from well-funded competitors.

Third, platforms beat one-off wins. Amgen’s real “product,” over time, was capability: mammalian cell culture and large-scale biologics manufacturing that started with EPOGEN and became the foundation for everything that followed. The same is true for repeatable skills like antibody engineering and clinical development know-how. Companies that can reuse a platform across many programs have a much better shot at durability than companies living and dying by a single molecule.

Fourth, M&A discipline matters more than M&A volume. Amgen has made a small number of truly consequential deals—Immunex and Horizon—and the common thread is clarity: buy assets that fit, where Amgen can add value operationally or strategically, and avoid deals that look exciting but don’t clear return hurdles. In pharma, the fastest way to destroy value is to confuse deal-making with strategy.

Fifth, lifecycle management is how franchises become decades long. EPOGEN led to Aranesp with more convenient dosing. Enbrel expanded through additional indications. Prolia and XGEVA used the same molecule to reach different patient populations with different commercial approaches. The drug isn’t “done” at approval; that’s when the work of compounding value often begins.

Sixth, the biosimilar era is both threat and opportunity—the biosimilar paradox. Biosimilars pressure Amgen’s older products, but they also opened a new business line when Amgen chose to launch biosimilars of competitors’ blockbusters. That willingness to compete on both sides of the equation is a sign of institutional adaptability, and it’s rarer than it should be among incumbents.

Seventh, capital allocation is the lie detector. Over decades, Amgen has put money into manufacturing, R&D, and selective acquisitions while also returning capital through dividends and buybacks. The ongoing question for investors isn’t whether Amgen can generate cash—it can—but whether management continues to deploy that cash into projects and deals that earn attractive returns as the company gets larger and the industry gets tougher.

Eighth, manufacturing is not a commodity function in biologics. It is a moat. The complexity of making proteins consistently, safely, and at scale doesn’t disappear when patents do. And for biosimilars, proving comparable quality adds time, cost, and risk. Amgen treated manufacturing as core strategy early, and the payoff has echoed through every era of the company’s growth.

Finally, regulatory expertise compounds the way scientific expertise does. After dozens of programs, a company learns—often the hard way—what regulators expect in trial design, what “good enough” manufacturing looks like, and how to build evidence packages that stand up to scrutiny. That institutional knowledge doesn’t show up in a single press release, but over time it can become a quiet advantage against competitors who have the science, but not the scars.

X. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

Amgen sits in a rare position for a mature biotech: it’s not hanging on by a thread in one therapeutic area. It has real franchises across bone health, inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and now rare disease—enough diversification that a hit in one corner of the portfolio doesn’t automatically become a company-wide crisis.

Yes, Prolia and XGEVA will eventually face biosimilar exposure. But denosumab is a complex, fully human monoclonal antibody, and that complexity matters. It raises the technical bar for competitors and can slow the pace of “me-too” erosion compared to the small-molecule playbook investors are used to. Meanwhile, Horizon’s products live in rare disease niches where patient populations are smaller and the economics often don’t attract a long line of biosimilar entrants. And even with the calendar marching toward 2029, Enbrel is still throwing off billions a year in the meantime—cash that can fund the next wave.

The real upside, though, is MariTide. Obesity has the potential to become the largest drug market the industry has ever seen, and the current leaders have proven patients will show up in massive numbers when the results are real. MariTide’s differentiator is straightforward and patient-friendly: monthly—or potentially less frequent—dosing. In Phase 2, it also showed strong weight loss at 52 weeks without an obvious plateau, alongside meaningful cardiometabolic improvements. If Phase 3 confirms that profile, Amgen doesn’t need to “win” the obesity category to change its own trajectory. In a market that could exceed $100 billion, even a modest share would be transformational.

On capital allocation, Amgen has earned some trust. The Immunex acquisition created huge value by pairing a breakthrough product with Amgen’s ability to scale manufacturing and meet demand. Horizon, while expensive, added differentiated assets that complement the portfolio and reduce dependence on any single legacy franchise. The through-line is not deal volume—it’s a willingness to act when the strategic logic is strong and the assets are high-quality.

And then there’s the advantage that’s hardest to copy: manufacturing. In biologics, “can you make it reliably at scale?” is often the real gate. Amgen’s global network and decades of process experience function like a moat—not just lowering costs, but de-risking launches, smoothing regulatory interactions, and preventing supply constraints that can cripple even great drugs.

Finally, the biosimilars strategy provides a built-in hedge. If biosimilars pressure Amgen’s older products faster than expected, Amgen can still participate on the other side of that trade through its own biosimilar portfolio. That doesn’t eliminate downside—but it can blunt it.

The Bear Case

The biggest risk is also the simplest: the Enbrel era ends. After decades of delay, 2029 is the date that matters. When meaningful biosimilar competition finally arrives, Enbrel’s revenue stream is likely to shrink materially. Given how large Enbrel has been historically, the drop could overwhelm the steady growth coming from smaller or mid-sized franchises.

A second concern is timing. Bulls often assume Prolia and XGEVA erosion is far off, but biosimilar development doesn’t stand still. Multiple companies have denosumab biosimilar programs underway, and the regulatory pathway gets clearer with every new biosimilar approval. If denosumab biosimilars arrive in the late 2020s, Amgen could be staring at overlapping pressure on both Enbrel and its largest current franchise—two big waves hitting close together.

Then there’s Horizon. Amgen paid a premium, and premium deals come with premium expectations. A $27.8 billion price tag only works cleanly if Horizon’s assets keep growing for years as they mature under Amgen. The FTC settlement adds another wrinkle: contracting and bundling restrictions that could reduce commercial flexibility. And while the integration appears to be progressing, the real proof is multi-year performance, not a strong first year.

Obesity is also not a free option. The category is getting crowded fast. Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk have multi-year head starts, deep real-world data, and entrenched prescriber and payer relationships. Even if MariTide succeeds clinically, commercial differentiation may be harder than the Phase 2 charts suggest. Monthly dosing is a real advantage—until competitors launch longer-acting formulations of their own.

Finally, the industry’s pricing environment is tightening. In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act introduced Medicare drug price negotiation. Internationally, reference pricing continues to pressure margins. Political appetite for lower drug prices isn’t fading. If pricing power erodes faster than volume can grow, even well-run portfolios can feel like they’re moving uphill.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of new entrants: Moderate, and rising in specific areas. Creating a novel drug is still slow, expensive, and failure-prone. But for off-patent products, biosimilar pathways lower the barrier. New modalities like gene and cell therapy also create alternative paths that can disrupt traditional biologics over time.

Bargaining power of buyers: High, and increasing. Payers and purchasing groups have consolidated, and they’re more willing to demand rebates, impose step edits, and restrict formularies. The bar is moving from “approved” to “approved and clearly worth it.”

Bargaining power of suppliers: Low to moderate. Many biologics inputs are relatively standardized, but specialized manufacturing services and critical technology providers can have leverage—especially for smaller companies without Amgen’s scale.

Threat of substitutes: Uneven. In some indications, small molecules or newer modalities can compete directly with biologics. In others, Amgen’s drugs remain entrenched standards of care. The substitution risk is real—but it depends heavily on the disease area.

Competitive rivalry: Intense. Big pharma has built serious biologics capability, focused biotechs keep attacking specific niches, and biosimilar manufacturers target every meaningful off-patent product. Competition is constant, and it’s coming from multiple angles at once.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Amgen’s manufacturing footprint provides cost and capacity advantages in biologic production that few peers can match.

Network Economics: Limited classic network effects, but durable relationships with physicians, payers, and key opinion leaders create real-world adoption advantages and inertia.

Counter-Positioning: Amgen’s biosimilar push lets it compete against pure innovators by offering lower-cost alternatives, while also competing against pure biosimilar players with brand credibility and a proprietary pipeline.

Switching Costs: Moderate to high in many biologic categories, where patients and physicians are reluctant to change a stable regimen, and payers weigh clinical comfort alongside economics.

Branding: Strong with clinicians and regulators. In professionalized markets, reputation for quality and consistency can matter as much as marketing.

Cornered Resource: Decades of manufacturing know-how and accumulated process expertise are difficult to replicate quickly. Patents add time-limited protection, but the operational knowledge persists.

Process Power: Biologics manufacturing processes, refined over years, can deliver quality and yield advantages that new entrants struggle to match.

Comparison with Competitors

Amgen’s valuation tends to reflect a push and pull: discounted versus companies like Eli Lilly, where obesity leadership is already real, but stronger than peers viewed as strategically stuck. The market is essentially pricing in the Enbrel cliff and future biosimilar exposure, while giving Amgen credit for diversification, cash generation, and pipeline optionality.

Against Roche, Amgen has less diagnostics integration but a deeper manufacturing identity. Against Novartis, Amgen is more concentrated in biologics and less in small molecules. Against AbbVie, Amgen shares the reality of biosimilar pressure, but has a different mix of franchises and a growing rare disease contribution.

Key Metrics to Monitor

The simplest way to track whether Amgen’s transition is working is to watch two things:

-

Organic revenue growth rate (excluding acquisitions and currency): this shows whether the core engine is actually growing, or whether growth is being bought.

-

MariTide clinical milestones: Phase 3 results and the path to regulatory submission will determine whether Amgen becomes a real obesity competitor or remains on the outside of a market dominated by Lilly and Novo.

Those two signals—organic momentum and MariTide’s outcome—will do more than any narrative to reveal whether Amgen is becoming a company defined by sustainable innovation, or one defined by managing decline until the next acquisition arrives.

XI. Epilogue & "If We Were CEOs"

The first quarter of 2025 kept the narrative intact: the newer engines pulled the company forward while the older ones faded on schedule. Product revenues grew year over year, driven by higher volumes in Prolia, Repatha, and the Horizon medicines. The legacy franchises declined as expected, but the growth portfolio more than made up for it. Management reiterated confidence in full-year guidance and pointed to continued pipeline execution.

MariTide is where the next decade gets decided. The Phase 3 program enrolled its first patients, with pivotal data expected in 2027. Amgen designed the program to do more than chase a single approval—it spans multiple trials in obesity and type 2 diabetes, with the clear intent to support follow-on label expansions if the data cooperate. In parallel, the company is already scaling manufacturing, investing in capacity that assumes commercial success. That’s what conviction looks like in biotech: spending real money before the win is guaranteed. The bet is enormous. The prize is even larger.

If we were sitting in the CEO chair, what would we be wrestling with? A handful of questions will shape whether Amgen can extend its forty-five-year streak of building value through platform shifts, patent cycles, and reinvention.

Should Amgen pursue another large acquisition? Horizon showed Amgen is willing to pay up for differentiated assets. There are always tempting targets in oncology, neuroscience, and beyond. But size cuts both ways. Integration risk rises fast, and after financing Horizon, the balance sheet has less room for error. The next big deal would need to be more than “strategically interesting.” It would need to be unmistakably worth it.

How hard should Amgen lean into next-generation modalities? Gene therapy, cell therapy, mRNA platforms—these are the kinds of technological shifts that can change what “biologics” even means. Amgen has made investments, but the company’s center of gravity is still antibodies and recombinant proteins. Overinvest and you burn capital chasing hype. Underinvest and you risk waking up to an industry that has moved on without you. The right answer is probably not a binary one, but the decision has to be deliberate.

What is the biosimilars business meant to become? As a hedge, Amgen’s biosimilar strategy has been elegant: participate in the very force that threatens older franchises. But biosimilars are a different game. Margins are thinner, competition can be relentless, and success depends on capabilities that don’t perfectly overlap with innovator commercialization. The company has to decide whether biosimilars remain portfolio insurance—or whether it wants to build a second major pillar there.

And then there’s Enbrel. The 2029 sunset is no longer an abstract future risk; it’s a date that shapes planning now. The job is twofold: optimize Enbrel’s cash flows through the remaining protected period, and invest aggressively enough in replacement revenue that the post-2029 step-down doesn’t define the whole company. Management could also explore partnerships or licensing structures that preserve some value as biosimilar competition arrives, but there’s no escaping the core reality: this franchise will eventually face gravity.

Zooming out, Amgen’s story still offers a set of durable lessons for anyone building in biotech. Focus beats sprawl—Amgen won early by committing to human therapeutics rather than dispersing into agricultural or industrial detours. Manufacturing matters as much as discovery—biologics are only “real” when you can make them reliably at scale. And patience isn’t a virtue here; it’s a requirement. Drug development rewards organizations that can compound effort over decades, not quarters.

Forty-five years after Bill Bowes assembled an advisory board and funded a $19 million experiment, Amgen stands as proof that molecular biology could become an industrial engine for medicine. From a lab where Fu-Kuen Lin hunted a single gene among 1.5 million DNA fragments, to a global company generating more than $33 billion in revenue with a pipeline aimed at some of the hardest problems in healthcare, the arc has validated the original bet.

The next era won’t be gentler. Patent cliffs, biosimilars, pricing pressure, and scientific disruption are all baked into the terrain. But so are the opportunities—obesity, rare disease, oncology, and breakthroughs that haven’t been named yet. Whether Amgen thrives in that future will depend on the same fundamentals that carried it here: scientific excellence, manufacturing mastery, regulatory fluency, and the discipline to make big choices at the right time.

The biotechnology pioneer is still, in its own way, pioneering.

XII. Recent News

Amgen’s fourth-quarter 2024 earnings came in ahead of analyst expectations. Revenue reached $9.1 billion, up 23% year over year—helped by a full quarter of Horizon. Those acquired medicines contributed $1.3 billion in the quarter, a quick proof that TEPEZZA, KRYSTEXXA, and UPLIZNA weren’t just “strategic rationale” on a slide deck, but products that could keep growing inside Amgen’s commercial machine. Management pointed to broad strength across the portfolio and reiterated its 2025 guidance.

On the pipeline side, MariTide kept doing the thing that has investors leaning forward: the Phase 2 dataset presented at a major medical conference showed weight loss continuing through 52 weeks, with patients at the highest doses losing about 20% of body weight on average. The more important signal wasn’t just the magnitude—it was the shape of the curve. Rather than flattening into a plateau, weight loss kept progressing. The data also reinforced MariTide’s monthly, or potentially less frequent, dosing profile, with no unexpected safety signals reported.

Amgen also kept leaning into the biosimilar paradox—building the very business that’s reshaping pricing across biologics. In 2024, it launched additional biosimilars including PAVBLU, a biosimilar to Roche’s Lucentis, and BKEMV, a biosimilar to Roche’s Avastin. The launches pushed Amgen further into ophthalmology and reinforced its position in oncology biosimilars. Taken together, the biosimilar portfolio had grown into a business generating more than $1 billion a year in revenue.

In oncology, momentum continued with tarlatamab—now marketed as IMDELLTRA—after positive Phase 3 results in small cell lung cancer led to FDA approval in 2024. Trials continued across a broader slate of bispecific T-cell engagers aimed at other tumor types, as Amgen tried to turn one approval into a repeatable engine. Beyond cancer, the company kept advancing programs in cardiometabolic disease, inflammation, and rare genetic conditions.

Behind the scenes, the global flywheel kept turning. Amgen made regulatory submissions and secured approvals across multiple international markets, including Europe and Japan, widening access to its portfolio. And manufacturing investments stayed on track, with new capacity intended to support both today’s products and the next wave still moving through the pipeline.

XIII. Links & Resources

SEC Filings and Financial Information

If you want the cleanest, most official version of Amgen’s story, start with its Form 10-K annual reports. They’re the definitive source for how the company explains its strategy, risks, and performance in its own words. Amgen’s Investor Relations site also keeps earnings decks, SEC filings, and management commentary in one place.

Scientific and Historical References

The moment the EPO saga becomes “real” on paper is Fu-Kuen Lin’s landmark publication: Lin et al., “Cloning and expression of the human erythropoietin gene,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (1985).

For NEUPOGEN and the underlying G-CSF biology, a key early reference is Souza et al., “Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: effects on normal and leukemic myeloid cells,” Science (1986).

Industry Analysis and Biotechnology History

For broader context on what early biotech felt like—and why it was such a strange mix of science, capital markets, and brinkmanship—Barry Werth’s The Billion-Dollar Molecule is useful background (even though it focuses on Vertex rather than Amgen).

For a more academic, industry-structure view of why biotech companies evolve the way they do, Gary P. Pisano’s Science Business: The Promise, the Reality, and the Future of Biotech is a solid framework for understanding dynamics that show up repeatedly in Amgen’s history.

Patent and Legal Documentation

If you want the “moat-building” details behind Enbrel, the primary sources are the federal court filings from the long-running biosimilar disputes, including cases involving Sandoz, Samsung Bioepis, and other would-be entrants.

For the Horizon deal drama, the FTC’s attempt to block the acquisition is captured in FTC v. Amgen Inc., filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois in May 2023.

Executive Perspectives

To hear how Amgen’s leadership frames the portfolio, the pipeline, and capital allocation in real time, look to executive presentations at major healthcare investor conferences, including JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley. Transcripts are typically available through financial data providers.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music