AppLovin: The AI-Powered AdTech Giant That Nobody Saw Coming

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

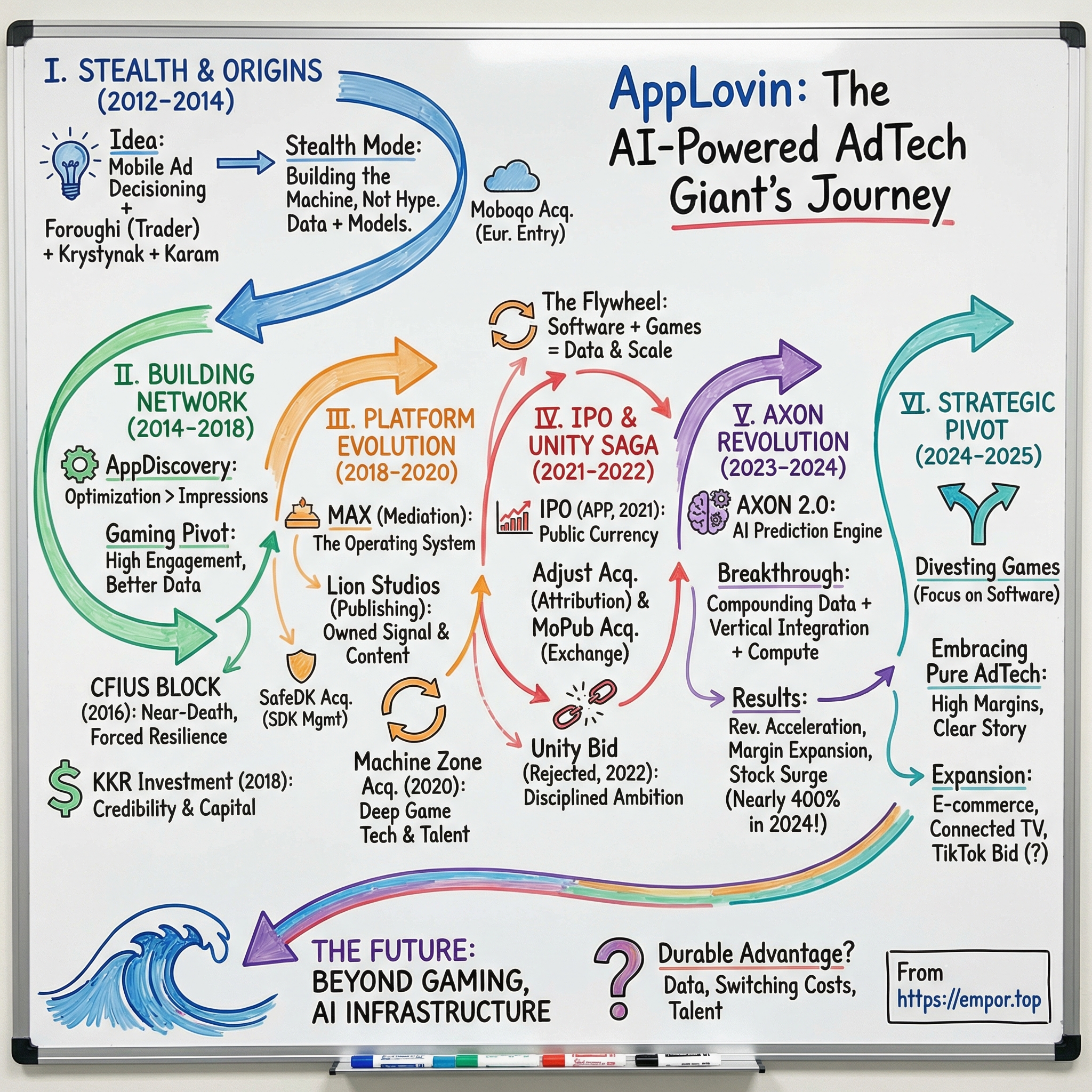

Picture this: it’s late 2024, and a company most people outside Silicon Valley couldn’t pick out of a lineup has just topped $4.49 billion in trailing twelve-month revenue. Its stock is up nearly 400% in a year. And suddenly, a whole lot of very serious analysts are trying to explain how a mobile advertising business—about as unglamorous as tech gets—became one of the biggest AI success stories outside of Nvidia.

That company is AppLovin. And its rise is one of the strangest, quietest, most consequential ascents in modern tech.

The question that’s been nagging Wall Street and Sand Hill Road is deceptively simple: how did a stealth-mode mobile ad company—founded by a former derivatives trader with no obvious advertising pedigree—turn into a force in AI-powered marketing?

The answer is a mix of patient capital, relentless dealmaking, and a genuine technical breakthrough called AXON that competitors still struggle to match. It’s also a story about timing: betting big on mobile when people still argued whether apps were a fad, then betting even bigger on AI before it became fashionable.

This is the untold story of adtech’s quiet revolution. We’ll follow AppLovin from its secretive origins in 2012, through a regulatory near-death experience when a Chinese acquisition was blocked, to its IPO, then the audacious (and rejected) bid for Unity—and finally the AXON-powered transformation that flipped skeptics into believers. Along the way, we’ll meet the founders who built the machine, unpack the business model that throws off enormous margins, and ask the big forward-looking question: can AppLovin keep winning as it pushes beyond mobile gaming into e-commerce and connected TV?

Because what’s most fascinating here isn’t just the numbers—though they’re hard to ignore. It’s the pattern. While others chased scale, AppLovin kept building technology. While competitors diversified, AppLovin leaned harder into what worked. And when AI arrived, AppLovin wasn’t scrambling. It was ready—almost hiding in plain sight.

So let’s start where great origin stories usually start: with an idea that, at the time, sounded just a little bit crazy.

II. The Stealth Mode Years & Origins (2012–2014)

In the spring of 2012, Silicon Valley had one big obsession: Facebook’s impending IPO, the largest tech debut since Google. But in a nondescript office in Palo Alto, three founders were aiming at something far less headline-friendly. Adam Foroughi, John Krystynak, and Andrew Karam were building an advertising company for mobile apps.

At the time, that sounded almost… small. The smart money chased social networks, e-commerce, and anything that looked like the next platform shift. “Mobile advertising” felt like plumbing. Which, of course, is exactly why it ended up being so powerful.

Even the name came from an unexpected place. AppLovin was inspired by Bloglovin’, a Swedish service that helped people organize and follow blogs back in the RSS era. Foroughi liked the tone—playful, human, a little disarming. “Lovin’” softened what was, underneath, a hard-nosed technology business. It hinted at connection and discovery. In hindsight, it fit perfectly: AppLovin would make its living helping users find apps they’d stick with, and helping developers turn that attention into revenue.

Foroughi’s route to advertising wasn’t the typical “worked at an agency, then started a startup” path. He began as a derivatives trader, a world built on probability, edge-finding, and making decisions with imperfect information. That mindset maps unusually well to advertising. In both, you’re trying to answer the same question, over and over: given what you know right now, what’s the value of this moment?

After trading, Foroughi founded Lifestreet, an adtech company focused on social games on Facebook. That gave him a front-row seat to the shift that mattered most: users leaving the desktop behind and moving into apps. The App Store had turned distribution into an algorithmic marketplace. Developers could reach anyone, anywhere—but only if they could get discovered. By 2012, Foroughi’s thesis was clear: apps were going to become the default way people used software, and the companies that helped developers grow and monetize would end up owning a tollbooth on the new economy.

The team ran AppLovin in stealth from 2012 to 2014—an unusually long time to stay quiet in Silicon Valley. During that period, they raised roughly $4 million from early backers including Streamlined Ventures and the Webb Investment Network, plus angel investors who bought into the vision early. Stealth did two things for them: it kept competitors from paying attention, and it gave the team space to iterate without performance being judged in public. They could build, break, rebuild, and only emerge once the product actually worked.

The timing mattered. In 2012, the mobile app economy was just tipping into its growth curve. The App Store was only four years old. Google Play was still maturing. In the U.S., smartphone adoption was crossing the halfway mark for the first time, and globally it was just beginning to accelerate. Developers were shipping into a market that was exploding—but also getting noisier by the week.

That created a painful new problem: discovery. Thousands of apps were launching constantly. You could build something genuinely great, but if you couldn’t climb the rankings or get noticed in the store, your app might as well not exist. Developers needed distribution, and the platforms weren’t going to hand it to them.

AppLovin’s first job was simple to describe: connect advertisers—usually other app developers—with publishers who had users and could show ads. A developer pays to place an ad inside another app. If someone clicks and installs, the advertiser gets a user, the publisher gets paid, and AppLovin takes a cut for making the match.

But the difference was never the mechanics. The difference was the decisioning.

Instead of treating inventory as interchangeable—just show ads to whoever happens to be there—AppLovin started building systems to predict which users were most likely to engage with which ads. That’s where Foroughi’s trading instincts showed up. In markets, you estimate value under uncertainty. In mobile ads, you do the same: what’s the expected return of showing this ad to this user, right now?

By the time AppLovin emerged from stealth in 2014, it was more than an ad network. It had the beginnings of the machine-learning foundation that would, years later, evolve into AXON. Those two quiet years weren’t about hype or distribution deals—they were about data, models, and infrastructure. Training on real traffic. Learning what converted and what didn’t. Building the plumbing to operate at massive scale.

And when they finally stepped into the light, they walked into a market that was both crowded and unsettled. Google and Facebook dominated digital ads broadly, but the specific world of app-to-app marketing was still messy. Smaller players like Chartboost, AdColony, and Vungle fought aggressively for developers. AppLovin entered that chaos with a sharp focus: outperform on the metric developers actually cared about—return on ad spend—and pay enough to win the inventory needed to keep improving.

The stealth years reveal the pattern that would define AppLovin for the next decade: the founders believed advertising wasn’t won by branding or relationships alone. In this business, technology is destiny. If AppLovin could consistently make each advertiser dollar work harder than a competitor’s, everything else—scale, margins, leverage—would follow.

III. Building the Mobile Ad Network (2014–2018)

When AppLovin finally stepped out of stealth, it didn’t do it with a splashy launch or a big marketing campaign. It did it the way it would do almost everything: by quietly expanding the machine.

In October 2014, AppLovin acquired Moboqo, a German mobile ad network. The terms weren’t disclosed, and the deal didn’t make headlines. But it was the first clear sign that AppLovin wasn’t trying to be just another scrappy ad network fighting for scraps in the U.S. Moboqo brought European inventory, talent, and on-the-ground experience in a market where American adtech companies often struggled with local norms and regulation. It was small, but it was strategic. And it kicked off an acquisition habit that would become core to AppLovin’s playbook.

From 2014 through 2018, AppLovin wasn’t simply growing. It was assembling a platform—piece by piece—while the mobile economy exploded around it.

The product that would eventually be called AppDiscovery evolved from basic matchmaking into something closer to a demand-side platform. Advertisers could define what they wanted—new users, purchases, whatever actually mattered to their business—and AppLovin’s system would optimize toward that outcome. In other words: less “buy some impressions,” more “spend this budget and hit this goal.” It was another expression of the same idea the company was built on: in ads, the edge comes from decisioning.

One shift in this era shaped AppLovin more than most people realize: the company’s move from the broad world of apps into the concentrated, high-octane universe of mobile gaming.

In the early years, mobile ads were spread across everything—productivity tools, social apps, utilities, games. But as the market matured, gaming emerged as the category where advertising simply worked best. Sessions were longer. Engagement was deeper. Monetization was clearer. And crucially, games trained users to accept ads as part of the experience—especially if the ad came with a reward.

Foroughi saw that pattern early and leaned into it. AppLovin built formats designed for games: rewarded video, interstitials between levels, playable ads that let users test-drive a game before installing. These weren’t just new ad units; they were a better trade. Users got value, publishers earned more, advertisers got stronger performance. That feedback loop pulled more gaming developers onto the platform, which produced more data, which improved optimization, which attracted more spend. The flywheel started to spin.

By 2016, the growth was impossible to ignore. AppLovin ranked number ten on Deloitte’s Technology Fast 500 in North America—a list built on revenue growth over four years. AppLovin’s growth rate cleared 4,000%, the kind of number that usually sounds fake until you realize the company had picked the perfect market at the perfect moment and executed with obsessive focus.

And then, in the same year, AppLovin ran headfirst into its first real brush with disaster.

A Chinese private equity firm, Orient Hontai Capital, agreed to acquire AppLovin for $1.42 billion. It would have been one of the biggest Chinese takeovers of an American tech company at the time—and it immediately triggered scrutiny from the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS.

CFIUS’s job is to ask a blunt question: does this deal create a national security risk? By 2016, the U.S. government was increasingly wary of Chinese access to American technology and, just as importantly, American data. And mobile advertising runs on data. Not just abstract “audience segments,” but real behavioral signals: which apps people use, when they use them, what they click, what they buy. In the wrong context, that kind of information can be sensitive.

After months of review, CFIUS effectively ended the deal. There was no dramatic public explanation—just the reality that it wasn’t going to get approved. For Orient Hontai, it was a dead end after an expensive process. For AppLovin, it was a near-exit that turned into a near-death experience.

Because internally, the company had been preparing for liquidity. Suddenly, there was none. Employees who thought they were approaching a payday were staring at paper value again. The founders had to steady the company, refocus, and convince everyone that AppLovin wasn’t a story that ended with a sale—it was a story that could keep compounding.

That reset set up the next chapter. In August 2018, KKR bought a minority stake in AppLovin for $400 million, valuing the company at about $2 billion—higher than the price in the abandoned Chinese deal. The capital mattered, of course. But the credibility mattered just as much. When KKR steps into your cap table, customers take you more seriously. Partners pay attention. And potential acquisition targets suddenly see you as a buyer who will actually close.

KKR’s bet also signaled something bigger: AppLovin didn’t look like the adtech businesses private equity traditionally avoided—volatile, low-margin, easily disrupted. It looked like a platform with sticky customers, strong economics, and technology that was getting better with scale. KKR was effectively underwriting the idea that AppLovin wasn’t “an ad network.” It was a technology company that happened to sell advertising.

Looking back, the 2014–2018 era is where AppLovin proved it could survive turbulence that would have broken weaker companies. The Moboqo deal showed the company could expand tactically. The pivot into gaming gave it a high-performance engine. And the CFIUS rejection forced AppLovin to build as if no savior was coming—no quick exit, no shortcut, just durable advantage.

Sometimes the deals that don’t happen end up shaping the company more than the ones that do.

IV. The Platform Evolution: MAX & Lion Studios (2018–2020)

By the time KKR came in, AppLovin had proved it could grow. Now it needed to become harder to displace. And in September 2018, it made a move that pushed it from “ad network” toward “core infrastructure”: it acquired MAX, a small startup built around in-app bidding.

To see why MAX mattered, you have to understand how mobile ads actually got sold. For years, most apps ran on something called a waterfall. When an app had an impression to fill, it would offer it to one ad network, then the next, then the next—usually based on who historically paid the most. It was orderly, familiar… and wildly inefficient. The market price for an impression changes constantly. The third network in line might be willing to pay the most in that moment, for that user, in that context—but it would never even get a shot.

In-app bidding—often compared to header bidding—flipped that. Instead of a slow, sequential process, multiple networks could bid at the same time, impression by impression. The publisher got a more competitive auction. Advertisers got cleaner access to inventory. The system, overall, got a lot closer to “the right price, right now.”

That’s what MAX brought: a mediation layer that let developers plug in dozens of networks, including AppLovin’s own AppDiscovery, and run real-time competition for every impression. And here’s the strategic unlock: even when AppLovin didn’t win the auction, it could still make money because it owned the rails the auction ran on.

This was AppLovin quietly stepping into a higher-leverage position. It wasn’t just fighting to be the best bidder. It was moving upstream to become the operating system for a developer’s monetization stack. Integrate MAX, and AppLovin wasn’t just a vendor anymore—it was embedded in your business. Better yet, because MAX was designed to work with everyone, publishers didn’t have to “choose” AppLovin. They could adopt MAX simply to earn more from competition—and AppLovin would gain visibility into what the entire market was willing to pay.

Around the same time, AppLovin made a move that looked, on the surface, like it was heading in the opposite direction. In July 2018—just two months before MAX—it launched Lion Studios, a mobile game publishing arm.

An adtech company publishing games sounds like a distraction until you look at what AppLovin had spent years learning. It was already exceptionally good at user acquisition for mobile games. Running campaigns across thousands of titles teaches you patterns most studios only learn the hard way: which genres pull which audiences, what drives retention, what monetization loops actually work. Lion Studios was a way to turn that knowledge into owned outcomes.

The model was straightforward. Independent developers brought games to Lion Studios. Lion provided marketing, distribution muscle, and monetization expertise. In return, it took a share of the revenue. For smaller developers, it was a compelling trade: they got access to AppLovin’s growth engine without having to front huge marketing budgets.

And for AppLovin, Lion Studios did something even more valuable than generating game revenue. It created a proving ground. Every title produced fresh data. Successful launches sharpened the company’s instincts about what “a winner” looked like. And the feedback loop tightened: better data improved AppLovin’s ad systems, which improved performance, which made Lion a more effective publisher, which attracted more developers.

In 2019, AppLovin added another piece to the platform puzzle by acquiring SafeDK, an Israeli company focused on SDK management. SDKs are the Lego bricks of modern app development—analytics, ads, attribution, crash reporting, payments, and more. But they can also be a source of pain. A buggy or poorly behaved SDK can slow the app, hurt battery life, or introduce privacy and security risk.

SafeDK gave developers a way to monitor how SDKs behaved inside their apps and catch problems before users did. For AppLovin, it was another step toward becoming indispensable. The more of the workflow AppLovin touched—monetization, mediation, tooling—the more deeply it was woven into the developer’s day-to-day reality, and the harder it became to rip out.

Meanwhile, the owned-content side expanded fast. AppLovin invested in PeopleFun, the studio behind word games including Wordscapes. It acquired Firecraft Studios. It bought Belka Games, known for casual and midcore titles. Each deal brought games, teams, and IP—but from AppLovin’s perspective, the recurring prize was learning. Every player action was signal. Every cohort was a lesson. All of it fed back into the advertising machine.

Then came the biggest swing of the era. In February 2020, AppLovin acquired Machine Zone (MZ) for an undisclosed sum.

Machine Zone was famous—almost infamous—for breakout hits like Game of War: Fire Age and Mobile Strike, titles that generated billions in lifetime revenue. At its peak, MZ was one of the most valuable private gaming companies in the world, reportedly valued at over $5 billion. By 2020, the studio wasn’t at that height anymore, but it still had valuable technology and battle-tested teams.

For AppLovin, MZ was a statement. Lion Studios was publishing leverage—finding promising titles and scaling them. Machine Zone was deeper capability: real, large-scale game development experience. AppLovin wasn’t just powering the gaming ecosystem. It was increasingly participating in it at the highest level.

Put it all together, and the 2018–2020 stretch reads less like a shopping spree and more like architecture. MAX became the infrastructure layer. AppDiscovery brought demand. Lion Studios and the growing portfolio of games brought first-party content and an ocean of behavioral data. Each part strengthened the others, making the flywheel harder for competitors to copy.

And just as importantly, AppLovin was building a business with two engines. The software platform could throw off strong, scalable economics. The games could generate meaningful revenue and, critically, more signal for the platform. That combination—software plus owned content—gave AppLovin flexibility and resilience heading into the next milestone: becoming a public company.

V. Going Public & The Unity Saga (2021–2022)

On April 15, 2021, AppLovin began trading on the Nasdaq under the ticker APP. The IPO priced at $70 a share, putting the company’s valuation around $24 billion. Overnight, AppLovin went from “well-known in mobile gaming circles” to a company that public-market investors now had to have an opinion on.

The timing was a gift and a test.

Early 2021 was peak growth-stock mania. The pandemic-era flood of liquidity had investors reaching for anything with a convincing chart and a big addressable market. Tech IPOs were getting welcomed like rock stars.

But adtech didn’t have a clean reputation in the public markets. Wall Street had seen this movie before: companies with slick decks and “proprietary” buzzwords go public, hit a wall, and then watch margins and growth get squeezed by competition. Investors had learned to be suspicious of businesses that looked like they were one pricing war away from mediocrity.

AppLovin’s pitch was that it wasn’t that kind of adtech company. It wasn’t just selling ads; it was building a system. An integrated platform. A machine-learning-driven decision engine trained on enormous volumes of activity. And—crucially—first-party signal from a portfolio of owned mobile games. In other words: not a commodity network, but infrastructure with an edge.

In the months around the IPO, AppLovin also started rearranging the chessboard with acquisitions that widened its footprint and tightened its grip on the ecosystem.

In February 2021, just weeks before going public, AppLovin announced it would acquire Adjust, a mobile measurement and attribution platform, for $1 billion in cash and stock. Attribution is the unglamorous but essential question behind every ad budget: did this campaign actually work? Which spend drove installs, purchases, and retention—and which spend just lit money on fire?

That problem was about to get harder. Apple was preparing to roll out App Tracking Transparency, forcing apps to ask users for permission before tracking them across other apps and websites. Advertisers worried they were losing the map. Adjust’s value was that it helped measure performance in a more privacy-constrained world, giving marketers a way to keep steering even as visibility shrank.

Adjust also pulled AppLovin closer to advertisers. If you used Adjust to understand performance, AppLovin’s network was a natural place to buy. And Adjust’s international footprint—based in Germany with strong European relationships—expanded AppLovin’s reach beyond its U.S.-centric roots.

Then, six months after the IPO, AppLovin made an even louder move. In October 2021, it announced it would buy MoPub from Twitter for $1.1 billion. Twitter was exiting the mobile ad exchange business; AppLovin was happy to pick up the assets.

MoPub overlapped with MAX in key ways—mediation and exchange plumbing for mobile publishers. By buying it, AppLovin didn’t just add supply and demand to its platform; it removed a meaningful rival. It was consolidation as strategy: fewer credible alternatives for publishers and advertisers, more leverage for AppLovin.

Critics called that anti-competitive. Supporters called it inevitable. Either way, it fit AppLovin’s pattern: control more of the stack, get closer to the transaction, and make the platform more essential.

And then came the swing that would have changed everything.

In August 2022, AppLovin made a proposal to acquire Unity for roughly $20 billion. Unity wasn’t an ad company—it was the game engine. The toolset thousands of developers used to build games and interactive experiences. If MAX was infrastructure for monetization, Unity was infrastructure for creation.

Put the two together and you can see the ambition: a full-stack gaming empire. Unity on the front end, powering development. AppLovin on the back end, powering monetization and user acquisition. Plus AppLovin’s studio portfolio producing first-party content. A closed loop where the company could help build the game, fund the growth, serve the ads, and measure the results.

AppLovin offered $58.85 per Unity share, pitching a stock-based merger. The storyline was straightforward: Unity had enormous reach but had struggled to monetize consistently. AppLovin had the monetization engine but depended on a broader ecosystem it didn’t control. Together, they could own more of the value chain.

Unity said no. Its board rejected the proposal, saying it wasn’t “in the best interests of Unity shareholders.” Unity was already moving in a different direction—toward building its own advertising business—and it had announced a merger with IronSource, one of AppLovin’s competitors in mobile advertising.

AppLovin didn’t turn it into a drawn-out public fight. In September 2022, it withdrew the proposal and moved on, saying its “path as an independent market leader is better.” It was a clean exit from a deal that had become increasingly unlikely. But it also marked something important: AppLovin was ambitious, but it wasn’t going to bet the company on a hostile integration it couldn’t control.

In hindsight, the Unity deal failing may have saved AppLovin from a world of pain. Combining two huge platforms—with different cultures, different products, and different incentives—can turn into a years-long distraction. And AppLovin was heading into a period where focus would matter more than grand theory.

That’s the real takeaway from 2021 and 2022. The IPO gave AppLovin the currency and credibility of a public company. The acquisitions tightened its position in the ecosystem. And the Unity saga revealed the company’s personality: aggressive enough to attempt a category-defining merger, disciplined enough to walk away.

Because the next chapter wouldn’t be won by dealmaking. It would be won by the thing AppLovin had been quietly building all along: the engine.

VI. The AXON Revolution: AI Changes Everything (2023–2024)

The breakthrough didn’t arrive with fireworks. In 2023, AppLovin rolled out AXON 2.0—an upgraded version of its AI advertising engine. From the outside, it could’ve looked like just another adtech “algorithm update,” the kind of thing every company claims will change everything.

Wall Street’s default reaction to those announcements is an eye roll.

But AXON 2.0 didn’t deliver a slight bump. It changed the slope of the business.

Here’s what AXON is actually doing. Imagine you’re a mobile game developer and you want new players—specifically the kind of players who won’t just install, but will stick around and spend. You hand AppLovin a budget and a goal, and AXON goes hunting.

It looks at mountains of signals—what users have installed, how they behave inside apps, what they’ve responded to before, when they’re active, what kinds of creatives they engage with. Then it makes a prediction about value: not just “will this person click,” but “what is this user likely to be worth over time?” Based on that, it decides how much to bid for a given impression. Then it learns. Constantly. The more outcomes it sees, the sharper the predictions get.

AXON 2.0’s edge came from a deeper change in how it processed information and made decisions. AppLovin didn’t spell out the technical blueprint—this is the crown-jewel IP—but industry observers believed the upgrade reflected advances in deep learning, especially around understanding sequences of user behavior and forecasting longer-term value.

Whatever changed under the hood, the results were loud.

After AXON 2.0, AppLovin’s software platform revenue—meaning advertising, not games—started accelerating in a way that didn’t look like normal “optimization.” In the first quarter of 2024, software platform revenue jumped 91% year over year to $678 million. The momentum continued. By Q3 2024, total revenue was $1.2 billion, up 39% from the year before, with the software platform segment up 66% to $835 million.

Growth like that is impressive anywhere. At AppLovin’s scale, it’s the kind of performance that forces people to update their mental model of what the company is.

Even more surprising: profitability rose alongside it. Gross margin improved from 67.74% in 2023 to 75.22% as the mix shifted toward higher-margin software revenue. AXON’s improved efficiency meant the platform could turn the same underlying machinery into more output. The unit economics got better while the company got bigger, which is the opposite of how a lot of ad businesses behave.

The market responded fast. After the tech selloff of 2022 and the Unity drama, AppLovin had been easy to dismiss as “just another adtech name.” In 2024, that narrative broke. The stock climbed nearly 400% over the year as investors re-rated the company around a new idea: maybe this wasn’t a commodity ad network at all. Maybe it was an AI-driven performance engine with real separation.

So what powered AXON 2.0’s advantage? AppLovin never reduced it to a single bullet point, but the ingredients were there.

First: compounding data. AppLovin had been collecting behavioral signals for more than a decade. Every day added more training data. And in machine learning, that history matters. Newer competitors can’t simply “catch up” with a better sales team; they need years of comparable feedback loops.

Second: vertical integration. Because AppLovin owned studios and published games through Lion Studios, it could see what happened after the install—how users behaved, what they engaged with, how much they spent. That downstream visibility made the system better at predicting long-term value, not just short-term clicks.

Third: talent concentration. AppLovin had built a serious machine learning bench, and its relative obscurity helped: engineers who might have been one of thousands at a mega-cap could join AppLovin and move the core model that drove the business.

Fourth: compute investment. Training and running sophisticated models isn’t free. AppLovin invested in the infrastructure required to operate at that level, creating a real barrier for smaller competitors who couldn’t afford the same scale of experimentation and iteration.

And then came the strategic unlock that made all of this bigger than mobile games: expansion.

AppLovin began pushing AXON 2.0 beyond gaming into e-commerce advertising and connected television. Same core idea—predict value, bid intelligently, learn from outcomes—but applied to categories with much larger pools of spend. If AXON could translate its performance gains into those markets, AppLovin’s addressable opportunity would expand dramatically.

Which leads to the real question investors were left with after 2024: is this advantage durable?

Tech history is full of companies that looked unstoppable—until competitors cloned the product, copied the playbook, and ground the edge down to zero. But AppLovin’s case had some defenses that are hard to hand-wave away.

The data advantage deepened over time instead of fading. The longer the system ran, the more it learned, and the further out the “catch up” timeline moved for everyone else.

Switching costs were real. Advertisers don’t just buy traffic; they build a working system—campaign setups, bidding strategies, creative learnings, internal processes—that takes time to develop. Starting over elsewhere is painful if performance is already strong.

And the talent war tends to reward incumbents with live, large-scale systems. For engineers, there’s a difference between working on an AI demo and working on AI that changes outcomes in production, at scale, with measurable results. AppLovin could offer the latter.

AXON 2.0 wasn’t just a better algorithm. It was the moment AppLovin stopped being a roll-up of adtech and gaming assets and started looking like what it had been trying to become all along: a decision engine that could keep getting smarter—and keep getting paid for it.

VII. Strategic Pivot: Divesting Games, Embracing Pure AdTech (2024–2025)

By early 2025, AppLovin’s transformation was starting to look less like a pivot and more like a verdict. In February, the company announced it would divest its mobile games business—selling off studios and titles it had spent years assembling—for about $900 million.

At first glance, it looked like a reversal. For years, AppLovin had told a compelling story about synergy: own games to generate first-party signal, then use that signal to make the ad system smarter, then use the smarter ad system to scale the games. But with AXON 2.0 now driving the business, the message got simpler—and sharper. Wall Street had been waiting for AppLovin to choose its best business and commit to it.

The reason was basic math: margins. AppLovin’s software platform—the advertising engine built around AXON—was producing gross margins above 75% and EBITDA margins approaching 80%. Games, even when they worked, carried the more normal economics of the gaming industry. Profitable, yes. But nowhere near as lucrative as software. In a world where every dollar of capital and every hour of executive attention has to compete, advertising won.

A few months later, in May 2025, the shift became even more concrete. Tripledot Studios acquired Lion Studios, effectively closing the chapter on AppLovin as a first-party game publisher. For Tripledot, Lion brought proven titles, publishing infrastructure, and talent. For AppLovin, it meant something just as valuable: fewer distractions, more focus, and more capital to pour into the platform that was compounding fastest.

There was also a quieter lesson embedded in the decision. Game studios run on creative bets, long timelines, and a tolerance for failure—because most games don’t hit. AppLovin’s edge wasn’t creative production. It was technology: data, models, and optimization. Exiting games was, in a way, AppLovin admitting what it truly was.

With games on the way out, the expansion efforts got louder.

E-commerce was the most important. AppLovin began signing major retail brands as advertising clients, bringing AXON’s optimization playbook into a category far larger than mobile games. The early logic was straightforward: the outcome changed, but the problem didn’t. Whether the goal is an install or a purchase, you’re still trying to predict which user will take an action—and how much that action is worth.

Connected TV was another frontier. AppLovin had acquired Wurl, a CTV advertising platform, and started integrating AXON’s decisioning with streaming inventory. As viewers shifted from cable to streaming, CTV was becoming one of the fastest-growing ad markets. Advertisers wanted the emotional punch of television with the targeting and measurement of digital. AppLovin’s bet was that it could deliver that combination—and use the same machine that worked in mobile to make CTV inventory perform like a performance channel, not just a brand channel.

And then, in April 2025, AppLovin took a swing that turned heads: it submitted a bid for TikTok’s U.S. operations.

ByteDance faced mounting regulatory pressure to divest its American subsidiary amid national security concerns. The symmetry was hard to miss. In 2016, AppLovin had been the company whose deal got blocked by CFIUS concerns. Now it was the American buyer looking at assets from a Chinese owner, in a politically charged process.

The TikTok move was aggressive—and a long shot. TikTok’s U.S. business was valued in the tens of billions, with multiple deep-pocketed buyers circling. But the interest itself was revealing. TikTok had what every ad platform wants: massive engagement, especially among younger users who are notoriously difficult to reach elsewhere. If AppLovin believed AXON could monetize attention better than the market expected, TikTok was the ultimate test case.

Whether that acquisition happened ultimately mattered less than what it signaled. AppLovin was no longer presenting itself as “mobile gaming adtech.” It was positioning as something broader: a technology platform for monetizing attention, wherever that attention lives. E-commerce, CTV, TikTok—different surfaces, same core capability.

For investors, the 2024–2025 shift also said something about management. Selling the games business meant walking away from a strategy the company had spent years building. But it also meant choosing the higher-return path with clear-eyed discipline. And the financial profile on the other side was hard to ignore: a pure-play advertising technology business with software-like margins and the ability to generate enormous free cash flow—cash that can fund growth, buy back shares, or finance the next opportunistic acquisition.

After years of building a two-engine company, AppLovin was making a clean bet on the one engine that now looked unstoppable.

VIII. Business Model & Technology Deep Dive

To understand how AppLovin makes money, you have to see it for what it really is: a two-sided marketplace with a very opinionated referee in the middle.

On one side are advertisers—companies trying to acquire users or drive sales. On the other side are publishers—app developers who have attention to monetize. AppLovin connects the two, runs the auction, decides who wins, and takes a cut for making the whole system work.

AppDiscovery is the front door for advertisers. A game studio looking for new players can launch a campaign, tell AppLovin what success looks like—installs, purchases, return on ad spend—and let AXON go to work. Instead of buying a pile of impressions and hoping for the best, advertisers are typically paying for outcomes: per install or per action. The promise is simple: you don’t just get reach, you get performance.

MAX is the publisher-side counterpart. If you’re a developer trying to monetize your app, MAX is the mediation layer that makes the chaos manageable. It plugs into your app, connects you to a long list of demand sources, and runs a real-time auction for every impression so you’re not relying on the old “waterfall” guesswork. When money moves through that auction, AppLovin takes a percentage.

Here’s how the loop closes in practice. A user opens an app. There’s an ad slot to fill. MAX sends out an auction request to multiple buyers, including AppDiscovery. AXON decides, in a blink, whether this impression is worth bidding on—and how much it’s worth. If AppDiscovery wins, the user sees an ad from one of AppLovin’s advertiser clients. The advertiser pays AppLovin, AppLovin pays the publisher minus its fee, and the machine moves on to the next impression.

You’ll often hear two metrics in this world: CPI and CPM. CPI—cost per install—is what advertisers pay to acquire a user. CPM—cost per thousand impressions—is how publishers typically think about what they earn by showing ads. AppLovin sits between those two numbers and keeps the spread. Its take rate—how much of the advertiser’s spend it retains instead of passing through to the publisher—generally lands in the 20% to 30% range, varying by product and client.

Now for the part AppLovin is the least eager to fully explain: AXON itself.

The architecture is intentionally opaque. In adtech, if you fully disclose how the model works, you’re effectively handing competitors the blueprint. But the broad shape is clear enough, and it helps to think of AXON as a system with three jobs.

First, it turns messy behavior into usable patterns. AXON processes huge volumes of signals and learns what tends to happen next: users who behave like this often install that kind of game, and a subset of them go on to spend at these levels. Modern privacy rules mean this isn’t about knowing who someone is. It’s about learning what certain kinds of behavior usually lead to.

Second, it makes real-time predictions on individual opportunities. When an ad request comes in, AXON has milliseconds to decide: do we bid, and if we do, what’s the right price for this user, in this context, right now? That’s not a “nice to have.” It’s the whole business. And doing it at scale demands serious infrastructure, because you’re running constant, high-speed inference while traffic never stops.

Third, it learns from what happens after the ad. Did the user install? Did they purchase? Did they stick around or churn immediately? Those outcomes flow back into the model, tightening the feedback loop and improving the next round of decisions. Tomorrow’s AXON is trained by today’s results.

This is where AppLovin’s compounding advantage starts to look less like marketing and more like physics. The company has been collecting and learning from mobile advertising outcomes for more than a decade. It sees billions of impressions every day, and each one is another training example. A new competitor can build software. They can raise money. They can hire smart people. But they can’t manufacture years of outcomes data overnight.

Historically, AppLovin also benefited from first-party signal from its owned game portfolio. Most ad platforms only see the user up to the click or the install. AppLovin, through its ecosystem, could often see what happened next—whether the user became valuable over time, not just whether they converted in the moment. That downstream visibility is gold for a model trying to predict lifetime value instead of short-term engagement.

Then there are the reinforcing loops that make platforms so hard to unseat. More advertisers can mean better demand and higher prices for publishers. Better publisher monetization attracts more supply. More supply improves reach and performance for advertisers. As the platform grows, it gets more valuable to both sides, and the “default” position gets stickier.

Scale piles on top of that. Running sophisticated AI on global ad traffic isn’t just a software problem; it’s a capital problem. Compute, storage, and the engineering talent to keep the system improving are expensive. And the uncomfortable truth of AI-driven advertising is that as models matter more, the market can get more concentrated, not less—because the biggest players can afford to iterate faster, test more, and learn from more outcomes.

So if you’re trying to judge how durable AppLovin really is, this is the crux: can it keep its edge as AI techniques spread and competitors get smarter?

Technology moats can evaporate. But AppLovin’s defenses aren’t only about clever code. The data advantage deepens with time. The product integration creates real switching costs—publishers and advertisers don’t just swap vendors without friction, rework, and short-term performance pain. And the talent loop is self-reinforcing: the best people want to work on models that run at real scale, on real money, with real feedback. AppLovin can offer that, and each improvement makes the platform more attractive to the next wave of talent.

In other words, AppLovin isn’t just selling ads. It’s selling a prediction engine—and charging a toll every time that engine makes the market a little more efficient.

IX. Playbook: Lessons from AppLovin's Journey

AppLovin’s rise isn’t just an adtech story. It’s a case study in how to build an enduring advantage when the market is changing underneath you. If you’re a founder, investor, or operator looking for patterns you can reuse, a few lessons keep showing up.

Timing did a lot of the heavy lifting. AppLovin was founded in 2012, right as smartphones crossed from “nice-to-have” to default, app stores started to mature, and mobile advertising was still more concept than infrastructure. Start too early and the ecosystem isn’t ready. Start too late and the best distribution gets locked up. AppLovin hit a narrow window where the market was big enough to matter, but still open enough to win.

But plenty of companies were founded in that same window. What separated AppLovin was the bet it made on the thing that actually decides winners in performance advertising: the decision engine. While other networks leaned heavily on sales relationships and expansion, AppLovin poured effort into data systems and machine learning. That foundation didn’t just help them compete—it compounded. Each cycle of traffic and outcomes made the system smarter, which made performance better, which brought more spend, which produced more data.

The company also ran a very intentional build-versus-buy playbook. AppLovin bought aggressively—MAX, Adjust, MoPub, Machine Zone, and a long list of studios—but the purchases weren’t random. Each one filled a missing piece: mediation rails, measurement and attribution, exchange supply, content and data, or simply removing a competitor from the field.

What it didn’t outsource was the core. AXON—the algorithms and systems that actually decide what to bid, when to bid, and how to optimize—stayed internal. Everything else could be acquired if it accelerated the roadmap. That’s a useful blueprint: buy the edges to move faster, build the center so you control the advantage.

Patient capital mattered more than most people want to admit. Two years in stealth gave AppLovin room to iterate without the pressure to look successful before it was. Later, KKR’s investment gave the company flexibility to make longer-term moves without living and dying by the next quarter. Even after the IPO, management kept spending on AXON improvements that didn’t always pay off immediately.

That patience wasn’t free. It required investor trust, and trust had to be earned through consistent execution. AppLovin built credibility the boring way: by delivering results and sticking to a coherent strategy long enough for the compounding to show up.

Another repeatable pattern: platform transitions create opportunity—if you’re willing to move early. AppLovin rode multiple shifts: desktop to mobile, basic ad networks to more programmatic markets, rules-based optimization to AI-driven decisioning. Each shift reshuffled the leaderboard. AppLovin’s instinct was to accept near-term pain to be positioned when the new system became the default.

The push beyond gaming into e-commerce and connected TV followed that same muscle memory. The outcome is still uncertain, but the logic is consistent: take the engine that works, apply it where budgets are larger, and try to become indispensable before the category fully settles.

The AXON moment also clarified something important about AI moats: AI by itself isn’t the moat. The moat is AI plus data plus scale, reinforcing each other. Competitors can copy ideas and hire smart teams. What they can’t quickly replicate is years of feedback loops, the infrastructure to run at massive throughput, and the integrated position in the ecosystem that keeps the data flowing.

Finally, AppLovin’s decisions showed that capital allocation is often the clearest signal of management quality. Over time, leadership made a series of choices that weren’t all “growth at any cost”: buybacks when the stock was depressed, debt paydown to strengthen the balance sheet, M&A that built platform leverage, and then the willingness to divest games once the higher-margin advertising engine proved it could stand on its own.

Taken together, the playbook is less about any one trick and more about a worldview. Find a market with a real inflection. Build the core advantage in-house. Use acquisitions to accelerate the rest. Let data compound. Be willing to change your mind when the evidence changes. And treat capital like strategy, not like fuel.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Competitive Analysis

The bull case for AppLovin is simple, and it’s powerful: AXON works, it’s getting better, and it’s doing so at margins that look more like software than advertising. If you believe AppLovin has built a real, durable performance advantage, then the rest follows—more advertiser demand, more publisher yield, more data, better models, and a compounding loop that throws off enormous free cash flow.

On top of that, the company’s growth story is no longer confined to the world that made its name. Mobile gaming was the training ground. The prize is what comes next.

E-commerce is the centerpiece. AppLovin’s historical stronghold—mobile gaming advertising—is big, but it’s still a slice of the broader performance marketing universe. E-commerce advertising is simply larger. And the key question isn’t whether the budgets exist; they do. The question is whether AXON’s core skill—predicting who will take an action, and what that action is worth—translates cleanly from “install this game” to “buy this product.” If it does, AppLovin expands its addressable market dramatically without needing to reinvent the business model.

Connected television adds a second, very different growth vector. As viewers move from linear TV to streaming, ad dollars have been following them. But CTV has a problem: advertisers want TV’s reach with digital’s targeting and measurement. If AppLovin can apply its decisioning and optimization to streaming inventory in a way that feels more like performance marketing and less like old-school brand buys, it gives the company another path to grow beyond mobile.

The bear case is just as clear: advertising is a knife fight, platforms change the rules whenever they want, and AppLovin’s edge will be attacked from every direction.

Start with competition. Unity’s merger with IronSource created a meaningful rival with real assets on both sides of the ecosystem: tools used by developers and technology used to monetize. Meta and Google remain the gravity wells of digital advertising, and either could lean harder into app advertising if the incentives were strong enough. The Trade Desk is a major player in programmatic—especially CTV—and while it doesn’t mirror AppLovin’s mobile roots, it competes for many of the same budgets as channels converge.

Then there’s platform risk—especially Apple. App Tracking Transparency, introduced in 2021, already made targeted advertising harder across the industry. Future privacy changes could further restrict the signals that models like AXON learn from. AppLovin has navigated shifts so far, but the underlying risk never goes away: the rules of the road can change overnight, and the companies that control the road don’t have to ask permission.

Finally, there’s saturation. Mobile gaming is mature in developed markets, and user acquisition has gotten more expensive as competition intensified. If AppLovin can’t keep expanding into new verticals, growth eventually compresses toward the pace of the underlying ad market.

Applying Porter’s Five Forces framework:

Supplier power is moderate. AppLovin relies on publishers for inventory, and the largest publishers do have leverage. But publishers are also fragmented, and performance tends to win. If AppLovin drives higher yield, most publishers will keep it in the mix.

Buyer power is moderate to high. Large advertisers can negotiate and diversify spend. Smaller advertisers have fewer credible alternatives if AppLovin is delivering superior performance, which limits their leverage.

Threat of new entrants is low. This is a scale-and-data business with real infrastructure requirements. Getting to parity isn’t just building a product; it’s building feedback loops over time.

Threat of substitutes is moderate. Budgets can shift to other channels—social, search, traditional media—but performance marketers follow what works, and mobile advertising still offers a level of measurement and optimization many channels can’t match.

Competitive rivalry is high. Meta, Google, Unity-IronSource, The Trade Desk, and a long tail of players all want the same dollars. AppLovin’s defense is differentiation through performance, not a race to the bottom on price.

Applying Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework:

Scale economies show up in the cost of running the system—compute, infrastructure, and R&D spread over massive volume.

Network effects come from the two-sided marketplace: more demand tends to increase yield for publishers; more supply improves outcomes for advertisers.

Counter-positioning was AppLovin’s early willingness to lean into AI-driven decisioning while others emphasized relationships and distribution.

Switching costs are real. Advertisers don’t just “turn on” a new platform; they rebuild playbooks, creatives, and optimization strategies, often at the cost of near-term performance.

Branding matters inside the industry—among developers and performance marketers—but it’s not consumer-facing brand power.

Cornered resource plausibly includes AppLovin’s accumulated data assets and specialized talent—both hard to replicate quickly.

Process power is the organizational ability to iterate, ship, and improve models in production, continuously.

Zooming back out, the landscape stays fluid. Unity-IronSource is the closest direct competitor, but integration has been challenging. Meta’s scale is unmatched and its AI investment is relentless. Google has structural advantages across the mobile ecosystem. The Trade Desk is strongest in CTV and broader programmatic, but as channels blur, the budget competition is real.

Valuation is where the story gets interesting. Even after the stock’s massive run, AppLovin traded around 18x forward earnings in early 2025—hardly a bubble multiple for a business that had been growing quickly with extremely high EBITDA margins. If growth holds up, that could look conservative in hindsight. If growth falls back to industry rates, the multiple can compress fast.

For long-term investors, the scoreboard isn’t complicated. Two KPIs do most of the talking:

Software Platform Revenue Growth Rate — This is the clearest signal of whether AXON is still pulling away. Staying above roughly the 30% range suggests a persistent advantage; a slide toward industry growth suggests the edge is narrowing.

Software Platform Gross Margin — This is the tell on pricing power and efficiency. Expansion implies strengthening leverage and differentiation. Compression is often the first sign the market is getting more competitive.

Together, those two numbers answer the only question that really matters: is AppLovin’s AI advantage still turning into sustained, profitable growth—or is it getting competed away?

XI. Looking Forward: The Next Chapter

E-commerce is AppLovin’s most important near-term expansion. Early tests with retail brands looked encouraging, but turning “promising” into “material” is a very different job. It means building new relationships, learning new buying cycles, and retraining the system on different user behavior than mobile gaming. It also means picking a fight with the incumbents. Meta and Google aren’t just competitors here—they’re the default pipes for a huge share of e-commerce advertising.

That’s why the timeline is still murky. Management has framed e-commerce as a multi-year push, not a quick pivot. The tells to watch are simple: named or clearly described e-commerce wins, evidence that non-gaming verticals are contributing in a meaningful way, and any signals that AXON’s performance is transferring effectively—because if the model advantage travels, the market gets much bigger.

International expansion is another obvious lever. AppLovin has historically been strongest in North America and Western Europe. Meanwhile, regions like Southeast Asia, Latin America, and India are seeing rapid growth in smartphones and mobile advertising. If AppLovin can replicate its playbook there—without getting tripped up by local market structure, competition, or regulation—it extends the runway and diversifies the business away from its most mature geographies.

Beyond that sits a longer-term opportunity: advertising outside of mobile apps entirely. In theory, the same core capability—predict outcomes, price inventory correctly, and optimize in real time—could be applied to desktop web, browser-based games, or web applications. AppLovin has stayed mobile-first, but the underlying idea behind AXON isn’t inherently limited to app installs.

The bigger strategic question is what comes after AXON 2.0. Machine learning doesn’t stand still. The techniques that look world-class today can look dated in a few years. AppLovin’s edge depends on continuing to invest in research, keeping the right talent, and being willing to rebuild parts of the system when the next approach is clearly better—even when the current one is working.

Generative AI cuts both ways. On the upside, creative generation—images, video, copy—could make AppLovin more valuable by helping advertisers iterate faster and find winning messages with less effort. On the downside, it could flatten parts of the ecosystem that used to be differentiators, making it easier for everyone to produce “good enough” creative and pushing more competition back into the auction.

Then there’s the TikTok wildcard. If AppLovin ever succeeded in buying TikTok’s U.S. operations, it would be acquiring one of the most engaging media properties on earth and a massive advertising surface to optimize. If it doesn’t, the core story doesn’t break—AppLovin keeps compounding on the trajectory it’s already on. The challenge is that TikTok’s outcome is tied up in shifting regulatory pressure, so forecasting it with confidence is closer to guesswork than analysis.

And finally, there’s the big framing question: can AppLovin become the “Google of mobile”?

It’s a tempting comparison, but it’s also an imperfect one. Google’s power comes from owning the intent graph—people telling it, directly, what they want. AppLovin’s position is different. It doesn’t own a primary consumer destination like search. Its strength is prediction and optimization: taking the opportunity that exists in front of it and being better than everyone else at deciding what to show, to whom, and at what price.

A more useful way to think about AppLovin is as infrastructure: the system that advertisers and publishers rely on even if they also use other platforms. That’s a less singular form of dominance than Google’s in search, but it can still be extremely durable—especially if performance keeps separating.

The next few years are the test. E-commerce needs to prove the AXON advantage travels across verticals. Connected TV needs to translate a growing budget pool into real share. International expansion needs to work across wildly different regulatory environments. And the AI lead needs to hold against competitors with massive resources and strong incentives to close the gap.

For investors, that’s the trade: a business with exceptional economics and a management team that’s shown it can execute, set against the usual adtech risks—competition, regulation, and the possibility that the edge narrows. If you believe the engine keeps learning faster than the market can copy, the runway is long.

It’s worth zooming out to appreciate how strange this arc really is. What started in a nondescript Palo Alto office in 2012—driven by a derivatives trader’s obsession with predicting value under uncertainty—turned into a company that survived a blocked Chinese acquisition, walked away from a bid for Unity, and then remade itself around an AI decision engine that changed the slope of its business.

AppLovin’s story is still being written. And if the last decade is any guide, the next chapter probably won’t look like the one most people are expecting.

XII. Recent News & Developments

Q3 2024 put an exclamation point on what AXON 2.0 had already been signaling: AppLovin was no longer just growing, it was accelerating. The company posted record quarterly results, with total revenue of $1.20 billion, up 39% year over year. The software platform did most of the heavy lifting—$835 million in revenue, up 66%—and profitability stayed unusually strong, with adjusted EBITDA of $722 million, a 60% margin.

Then came the simplification of the business.

In February 2025, AppLovin announced it would divest its mobile games portfolio for roughly $900 million. A few months later, in May 2025, Tripledot Studios acquired Lion Studios—closing the loop on a strategy that had once been central to AppLovin’s identity, and underscoring that the company now wanted to be judged primarily as an advertising and software platform.

At the same time, AppLovin kept pushing AXON into bigger pools of spend. Through 2024 and into early 2025, the company continued expanding its e-commerce offering and signed several major retail brands as new clients—an important signal that the performance engine it perfected in gaming was starting to translate.

And in April 2025, AppLovin reminded everyone it still had an appetite for big swings, submitting a bid for TikTok’s U.S. operations during ByteDance’s regulatory-driven divestiture process. Whether or not the deal ever had a realistic path, the message was clear: AppLovin was thinking beyond “mobile ads” and aiming for whatever surfaces hold the most valuable attention.

The market, meanwhile, had already rendered its verdict on the AXON era. AppLovin’s stock rose nearly 400% in 2024, turning a once-under-the-radar adtech name into one of the year’s standout large-cap technology stories.

XIII. Sources & Resources

SEC Filings & Investor Relations - AppLovin Form 10-K annual reports (2021–2024) - AppLovin Form 10-Q quarterly reports - AppLovin investor relations presentations and earnings call transcripts - S-1 registration statement (April 2021 IPO)

Key Management Commentary - Adam Foroughi interviews discussing technology strategy and AXON’s development - Quarterly earnings calls, including management Q&A

Industry Research - Mobile advertising market reports from eMarketer and App Annie - Gaming industry research from Newzoo and Sensor Tower - Connected TV advertising projections from industry analysts

Regulatory Filings - CFIUS materials related to the 2016 Orient Hontai transaction - FTC and antitrust filings tied to major industry acquisitions

Company Announcements - Press releases on the MAX, Adjust, MoPub, and Machine Zone acquisitions - Unity merger proposal materials and withdrawal statements (August–September 2022) - Mobile games divestiture announcements (February–May 2025)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music