Booking Holdings: The Accidental Empire That Conquered Travel

I. Cold Open & Episode Thesis

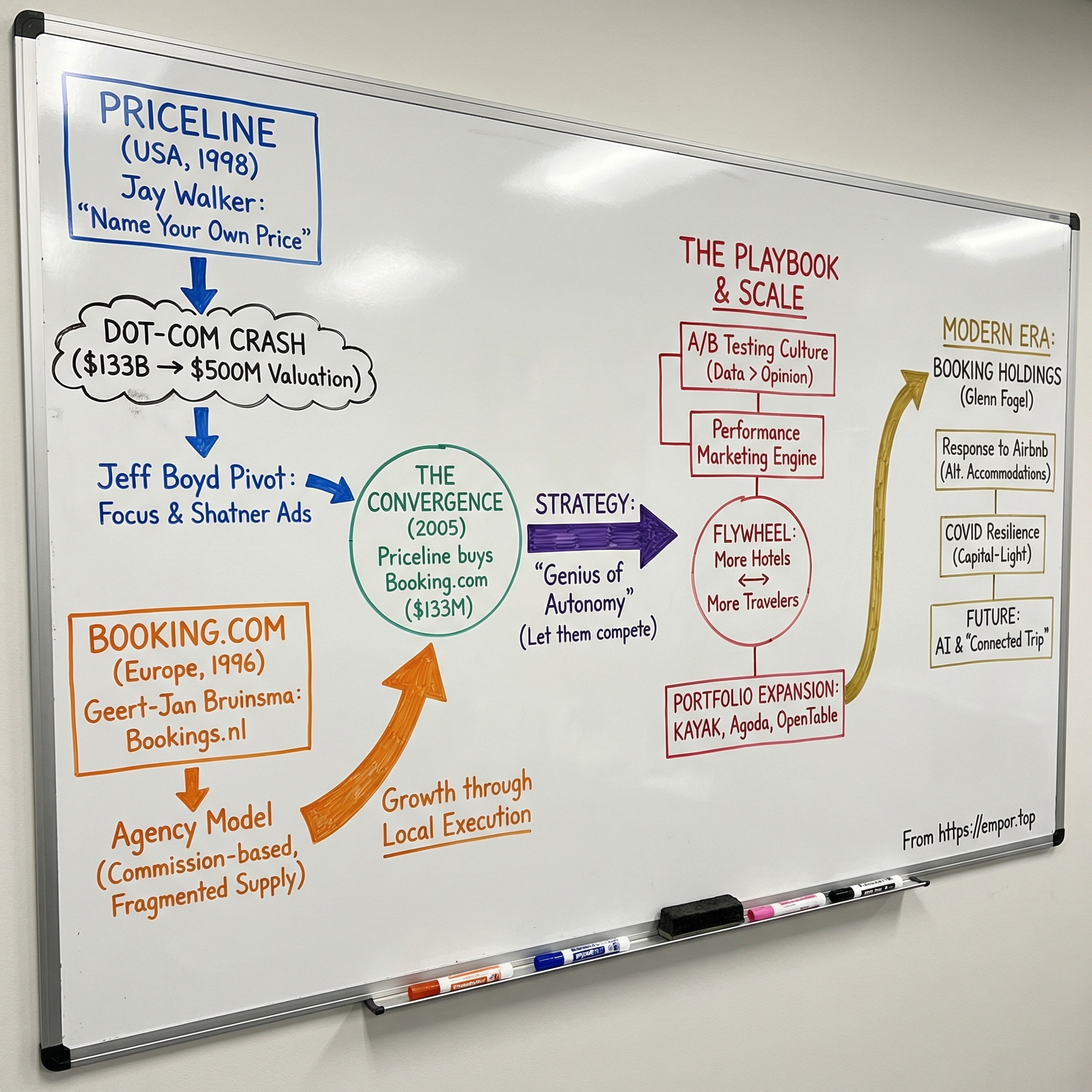

In the annals of internet history, few acquisitions look as obvious in hindsight as the one that closed on a summer day in July 2005. A battered American dot-com survivor—best known for William Shatner hocking oddball “name your own price” travel deals—quietly bought a small Dutch startup for $133 million in cash. Two decades later, that deal would be spoken about in the same breath as the greatest acquisitions the commercial internet ever produced.

The buyer was Priceline. The company was Booking.com. And the way it played out broke almost every Silicon Valley rulebook.

Today, Booking Holdings is the gravitational center of global travel, facilitating more than 1.049 billion room nights of accommodation each year. In 2024, it generated $23.7 billion in revenue, and its market value towered over most travel companies combined. But none of that was preordained. The empire was built through a near-death experience, a contrarian bet on Europe, and a management philosophy that would make many American tech executives wince: buy great teams, then mostly get out of their way—even if that means letting your own businesses compete with each other.

The Booking Holdings story forces a rethink of what actually wins on the internet. While the Valley fixated on viral loops and winner-take-all network effects, a group of Dutch engineers—and the unlikely American parent company that backed them—leaned into something quieter and more durable: a commission-based model that aligned incentives with hotels, a culture that treated A/B testing like religion, and an expansion strategy that turned Europe’s fragmentation into an advantage.

This is the story of how a dorm-room side project became the backbone of modern travel—and what it reveals about how the best businesses really get built.

II. The Priceline Origin Story & Near-Death Experience

The Demand Collection System

Jay S. Walker was not a typical tech founder. He was an inventor and prolific patent collector, and more than anything, a big-idea guy. In 1996, inside his Connecticut think tank, Walker Digital, he fixated on a deceptively simple question: what if customers told businesses what they were willing to pay, instead of businesses telling customers what things cost?

He called it the “demand collection system.” The theory was clean and intuitive. Airlines flew with empty seats. Hotels had rooms that went unfilled. Plenty of travelers were flexible if the price was right. So why not build a marketplace where the buyer named a price first—and the seller decided whether to take it?

Walker believed he’d found a structural inefficiency in how commerce worked. Fix it, and the upside could be enormous.

In 1998, Priceline.com launched with what became its signature: Name Your Own Price. It was a reverse auction for travel. Customers entered a bid for an airline ticket, hotel room, or rental car, and then waited to see if a supplier would accept.

The timing couldn’t have been more dot-com perfect. The internet bubble was inflating fast, and anything novel that lived online could command a premium. Priceline’s model was genuinely different, and Wall Street loved different.

In March 1999, Priceline went public—and for a moment, it looked like the future arriving on schedule. On its first day of trading, Priceline hit a $12.9 billion market value, then the highest first-day valuation ever for a corporation at the time. Walker owned about 35% of the company. Overnight, he became a paper multi-billionaire. The press piled on praise. Analysts floated comparisons to the defining internet winners of the era.

The Crash

But there was a problem at the center of Walker’s elegant idea: in practice, it didn’t really work the way the story sounded.

The Name Your Own Price system tended to pull in a very specific kind of demand—customers who were highly price-sensitive and willing to tolerate a lot of friction. Airlines and hotels, meanwhile, were only eager to accept bids when they had distressed inventory they couldn’t sell any other way. Customers didn’t know if their bid would go through for hours. They couldn’t choose the exact airline or hotel. Premium travelers—people who cared about certainty and control—stayed away.

Walker’s instinct wasn’t to narrow the concept. It was to widen it.

In 1999 and 2000, Priceline tried to stretch Name Your Own Price into a whole catalog of categories: groceries, gasoline, home mortgages, even cars. It acquired WebHouse Club to bring the bidding model to supermarket products. This was peak dot-com era logic: if you can make one market “efficient” with a clever mechanism, why not apply it everywhere?

Because people don’t want to bid on Cheerios. Gas station owners weren’t eager to entertain random offers. Mortgages didn’t fit the model at all. By late 2000, the experiments were shut down, and WebHouse Club was closed.

Then the wider market turned. When the dot-com bubble burst, Priceline’s stock cratered from a peak above $150 a share to under $2. The company that had briefly been worth nearly $13 billion fell to a valuation under $500 million. Walker stepped back from day-to-day operations, and the board brought in new leadership to keep the lights on.

The Turnaround Under Boyd

In 2002, Jeffery H. Boyd was named CEO, and Priceline’s comeback started with a sharp shift in temperament. Boyd was the opposite of Walker: not a conceptualist, but an operator. A lawyer by training, he’d joined Priceline as general counsel. He wasn’t trying to reinvent capitalism. He was trying to build a real business.

Boyd’s plan was straightforward: focus on what actually made money. He cut away the distractions, leaned into the core travel offering, and poured energy into something that, in hindsight, might have been the company’s most durable early advantage: marketing that people remembered.

William Shatner had joined Priceline’s orbit in 1997, playing “The Priceline Negotiator” in TV spots that were equal parts absurd and brilliant. As Boyd stabilized the company, the Shatner ads became iconic. The former Star Trek captain delivered deadpan pitches about saving on hotels, throwing in karate chops and melodrama like he was in on the joke—because he was. The campaign made Priceline a household name even as the company itself was still recovering from the wreckage.

By 2003, Priceline was profitable again. But it was also small—largely U.S.-focused—and its signature model had a ceiling. Name Your Own Price had found a niche: bargain hunters willing to trade control for a deal. It was not, on its own, a platform that could take over global travel.

Boyd and his team needed a second act.

And it was coming from a place Priceline hadn’t originally been built to win: across the Atlantic, where a very different kind of travel company was taking shape.

III. Meanwhile in Europe: The Booking.com Genesis

A Student's Side Project

In 1996, while Jay Walker was sketching big theories about “demand collection” in Connecticut, a student at the Universiteit Twente was tackling a much more concrete problem: helping people book Dutch hotels online.

His name was Geert-Jan Bruinsma. His solution was a simple site called Bookings.nl.

Europe’s commercial internet was just beginning to flicker to life, and the Netherlands was ahead of the curve. Bruinsma’s project wasn’t built to impress investors. It was useful. A straightforward directory of hotels, with pricing and availability, where you could actually make a reservation online. Practical, utilitarian, and quietly ambitious in the way a lot of great internet businesses start.

What Bruinsma couldn’t have fully known then was that Europe itself was the cheat code.

American travel, especially hotels, was dominated by big chains—Marriott, Hilton, Hyatt—companies with distribution muscle and the resources to build their own systems. Europe was different. It was a mosaic of independent hotels, family-run pensions, and small boutique properties. A three-star hotel owned by a local family in Amsterdam didn’t have a tech team, a marketing department, or a clean way to reach travelers from London or New York. It just had rooms to sell.

That gap—between global demand and local, fragmented supply—was enormous. And Bookings.nl was stepping into it.

The Merger

In 2000, Bookings.nl merged with Bookings Online, founded by Sicco and Alec Behrens, Marijn Muyser, and Bas Lemmens. The combined company took a new name: Booking.com. Suddenly it had real scale in the Benelux region, and more importantly, momentum.

The early team had an unusual trait for people building a hotel business: they were technologists who knew very little about the hotel industry. In almost any other context, that would be a disadvantage. Here, it was a feature. They weren’t trying to preserve the way hotel distribution had always worked. They were trying to make online booking work.

Most online travel agencies at the time—including Priceline in the U.S.—leaned on the merchant model. The OTA would negotiate discounted rates, buy or effectively pre-purchase inventory, then resell rooms to travelers at a markup. It took on financial risk and owned more of the customer relationship. Hotels got volume, but they gave up margin and control.

Booking.com went the other way. It embraced the agency model.

Instead of buying rooms, Booking.com simply connected travelers with hotels and earned a commission on completed stays—often in the low-to-mid teens as a percentage of the room rate. The hotel kept control of pricing, handled payment, and bore the inventory risk. Booking.com was a marketplace, not a reseller.

Why the Agency Model Won

On paper, the agency model sounded less powerful. No markup. No inventory control. No “wholesale” leverage.

In practice, it was rocket fuel.

For Europe’s long tail of independent hotels, the pitch was radically easier to say yes to. A family-run property in Barcelona might balk at handing rooms to an intermediary at steep discounts. But paying a reasonable commission for incremental customers—especially international ones—felt like a partnership.

The incentives lined up cleanly, too. Booking.com only made money when a booking actually happened. If guests didn’t show or a stay didn’t materialize, there was no upside. That pushed the platform to focus on generating real demand and real conversions—exactly what hoteliers cared about.

By 2005, Booking.com had opened local support offices across key European markets, including the UK, France, Spain, Portugal, and Germany. The approach was disciplined: build a local presence, sign up supply market by market, and then use performance marketing to bring in travelers who were ready to book.

What many American travel companies saw as Europe’s biggest drawback—fragmentation—became Booking.com’s edge. Every independent hotel was a new piece of inventory that needed distribution. Booking.com was willing to do the unglamorous work of signing them up, one by one.

And as its inventory grew, so did its pull with travelers. More hotels meant more choice. More choice brought more bookings. More bookings convinced more hotels to join.

A flywheel was starting to spin. And across the Atlantic, Priceline was about to discover it.

IV. Active Hotels: The Forgotten Piece

The Cambridge Connection

While Booking.com was stitching together Europe from Amsterdam, a different team was building a parallel business out of Cambridge, England.

Active Hotels, founded in the late 1990s, had built a technology platform that helped hotels manage their inventory and take online bookings. Like Booking.com, it went after Europe’s independent hotels. But culturally, it looked a little closer to what an American buyer would recognize: British entrepreneurs, a more corporate tone, and an easier fit with U.S. dealmaking norms.

This is where Glenn Fogel enters the story.

At Priceline, Fogel was the executive tasked with scouting opportunities outside the U.S. He started making trips across Europe, meeting founders, mapping the competitive landscape, and trying to understand what was actually working on the ground. People who knew him described him as “a hugely personable, well-connected and great guy,” and “very, very well-connected to the European tech scene.” In a market where relationships mattered, that counted for a lot.

Active Hotels, for its part, was looking for a path to scale. And eventually, the outreach became direct. Someone at the company—reportedly Shane Whaley—picked up the phone and called Priceline with a pitch that was almost disarmingly simple: “Oh, do you want to do a deal with us so we can give you all this inventory of independent hotels in Europe?”

The timing couldn’t have been better. Priceline had finally stabilized under Jeff Boyd. The U.S. business was back on its feet. But growth at home was getting harder, and Name Your Own Price wasn’t going to carry the company into the next decade on its own. Europe, with its fragmented supply and exploding online demand, looked like the next battlefield.

In December 2004, Priceline bought Active Hotels for $161 million. It was Priceline’s first major international move—and the opening step in a European expansion that would end up redefining the entire company.

The Strategic Logic

The Active Hotels deal taught Priceline a few things fast.

First: European hotel inventory was unusually valuable. Independent hotels weren’t as plugged into global distribution, which meant the platforms that signed them early could become the default on-ramp for international travelers.

Second: the commission-based agency model was attractive. It threw off strong cash flow without requiring Priceline to take on inventory risk or tie up a lot of capital.

And third—maybe the most important lesson—was the most humbling: the Europeans were ahead. They had built playbooks for online hotel booking that American companies hadn’t fully internalized yet.

Priceline’s leadership also trusted Fogel, and that mattered. As one executive later put it: “Probably, crucially, we trusted him. He’s got very high integrity as an individual.” That trust became a kind of internal permission slip—one that would prove essential when an even bigger opportunity surfaced.

Active Hotels also helped set a template that Priceline would lean on again and again: buy strong local teams, give them resources, and resist the urge to “fix” what’s already working. In Europe, the American way wasn’t automatically the right way.

And now Priceline had a foothold.

Which meant it finally had the vantage point to see the real prize.

V. The $133 Million Deal That Changed Everything

The Announcement

On July 14, 2005, a press release landed with a kind of quiet confidence—and an unusually wide footprint. It went out from three places at once: Norwalk, Connecticut; Cambridge, UK; and Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Priceline.com announced it had acquired Amsterdam-based Bookings B.V., one of Europe’s leading internet hotel reservation services, in an all-cash deal valued at about €110 million, or $133 million.

At the time, it barely caused a ripple. Priceline was still remembered as a dot-com oddity that survived the crash on the back of a quirky bidding model and William Shatner ads. Booking.com was a serious operator in Europe, but not yet a global household name. The coverage that did appear treated the deal like a logical add-on to Priceline’s European push—not the moment a future travel empire snapped into place.

But the really important context wasn’t in the press release. It was in what had happened behind the scenes.

Expedia—Priceline’s bigger, more established rival—had also been in discussions to buy Booking.com. And according to industry accounts, Expedia walked away. In hindsight, that decision didn’t just look like a missed acquisition. It looked like a missed decade.

The Reinvestment Decision

There was one detail in the transaction that revealed how the people closest to the business saw the future: Booking.com’s six top executives reinvested part of their proceeds back into the company.

They didn’t have to. They could have taken the win and moved on, like most founders and early executives do after a sale. Instead, they effectively said: we’re not done. We think this thing can get much bigger, and we want our chips on the table when it does.

That move signaled confidence in two directions at once. The Dutch team believed Priceline could provide the capital and support to accelerate what they’d already built. Priceline, meanwhile, was getting something even more valuable than inventory or software: a leadership group that wasn’t treating the acquisition as an exit, but as a launch.

The Integration Challenge

Of course, buying a company is the easy part. Making it work is where deals go to die.

Priceline now owned two European businesses operating in the same broad space: Active Hotels in Cambridge and Booking.com in Amsterdam. On paper, that sounded like “synergy.” In reality, it meant overlapping teams, different tech stacks, different market instincts, and two proud cultures that had each been winning in their own way.

As one participant later put it, “In the grand scheme of things, the integration went remarkably well,” but it was also “at times a tough marriage between Active and Bookings.” The British and Dutch teams had different working styles and different assumptions about how the product should evolve. Active had built strength in the UK. Booking.com was surging across the Continent. It didn’t take long for the obvious questions to show up: whose systems would become the foundation, whose processes would become standard, and who would ultimately be in charge.

The Genius of Autonomy

What made the situation work wasn’t a perfectly executed integration plan. It was Priceline’s willingness to resist the instinct to over-integrate.

Instead of immediately forcing everything into a single unified platform, Priceline largely let its European companies run. The philosophy was simple: let the constituent businesses execute independently—and, if necessary, even compete with each other.

That’s not how most American acquirers operate. The usual playbook is to centralize, standardize, and harvest “synergies” by eliminating redundancy. Priceline did something closer to the opposite. It recognized that the value it had just purchased was embedded in local knowledge, speed, and culture—and that heavy-handed control from headquarters would be the fastest way to destroy it.

So Booking.com kept operating out of Amsterdam, with its engineering-driven culture and deepening obsession with experimentation. Active Hotels kept going from Cambridge. Over time, brands and operations would increasingly consolidate. But the core insight—local teams understood their markets better than distant headquarters ever could—stuck, and it became one of Priceline’s defining management principles.

In retrospect, the numbers in that press release were almost comical. $133 million for what became the engine of the world’s largest travel platform is why people still talk about this deal the way they do. Some observers have ranked it among the best internet acquisitions ever—often placing it around fifth, alongside transactions like Google buying Android or Facebook buying Instagram.

And the lesson is both simple and painful: sometimes the smartest thing you can do after you buy something great is to not break it.

VI. The Booking.com Playbook: Data, Testing, and Relentless Execution

The A/B Testing Religion

Inside Booking.com’s Amsterdam headquarters, a culture formed that competitors could copy in theory but rarely match in practice. Booking.com didn’t just believe in A/B testing. It built the company around it.

Most tech companies say they’re data-driven. Booking.com behaved like it. At its peak, it ran thousands of experiments at the same time. Button text. Button color. Page layout. The order of filters. The wording of a cancellation policy. If it touched the booking flow, it was fair game.

And the social rule inside the building was even more important than the tooling: opinions didn’t win arguments. Data did. If you thought a change would lift conversion, you didn’t fight it out in a conference room. You designed the test, shipped it, and let real customers decide.

Over time, this created a compounding advantage. The site was never “done.” It was constantly being tuned, week after week, through a process that looked a lot like evolution: changes that improved outcomes survived, and everything else got rolled back. A thousand small wins, stacked for years, turned Booking.com into a machine built to convert intent into bookings.

That mindset shaped the organization itself. People who could frame good questions and run clean experiments gained influence. People who leaned on seniority, gut feel, or loud certainty struggled to move decisions. The culture rewarded results, not rhetoric.

The Virtuous Cycle

The other half of the playbook was the flywheel. Booking.com’s model reinforced itself in a way that got harder and harder to break.

More inventory attracted more travelers. More travelers produced more bookings. More bookings produced more commission revenue. That revenue funded more marketing and more local expansion. Which brought in more hotels. And around it went.

The agency, commission-based model made the whole system unusually easy to scale. Booking.com didn’t need to buy inventory or negotiate wholesale rates to grow. For many properties, joining was simple: list your rooms, set availability, and start getting demand. That low friction let Booking.com add supply quickly, especially across Europe’s huge base of independent hotels.

And once the machine was running, the results showed up at the parent-company level. The combination of Booking.com and Active Hotels was a major driver in Priceline’s transformation—from losing $19 million in 2002 to earning $1.1 billion in profit by 2011. In less than a decade, what started as a European foothold became one of the most powerful profit engines in internet business.

The Power of Performance Marketing

Booking.com also got very, very good at something that isn’t glamorous, but wins wars: performance marketing.

Instead of betting on brand advertising or hoping for viral growth, Booking.com systematically went after travelers with high intent—people already searching for a place to stay. If you typed “hotels in Barcelona” or “Amsterdam accommodation,” Booking.com wanted to be the obvious answer, whether that meant ranking organically or showing up as the paid result at the top of the page.

This wasn’t just “buy some Google Ads.” It was a discipline. Booking.com obsessed over landing pages, search terms, conversion funnels, and attribution. It engineered the site to match the way travelers searched, and then made the experience tight enough that those visitors actually booked.

Behind the scenes, it built systems that could generate enormous numbers of destination and property pages, populated with the exact details travelers cared about—availability, pricing, reviews—kept fresh in a way search engines rewarded. The payoff was scale: a steady stream of organic traffic, plus paid traffic that could be dialed up when the economics made sense.

And because performance marketing is measurable, it fit perfectly with Booking.com’s testing culture. The company tracked acquisition costs in detail, then tuned spend across channels, markets, and timing. The result was growth that stayed tethered to unit economics—something many competitors struggled to pull off once marketing got expensive.

Why Being Dutch Helped

Booking.com’s Dutch roots turned out to be an edge, not a footnote.

The Netherlands is small, outward-looking, and multilingual. Dutch professionals often grow up switching between languages and cultures as a matter of course. That translated directly into how Booking.com expanded: not by treating “international” as a later phase, but by acting like every market mattered from the start.

Localization wasn’t a skin-deep translation job. Booking.com invested in local-language sites, local customer support, and local hotel relationships. It built real experiences for French, German, Spanish, Italian, and then dozens more languages—because in Europe, language isn’t a feature. It’s table stakes.

That’s why Europe’s fragmentation, which many U.S. companies found messy and slow, became Booking.com’s natural habitat. The company was designed to operate across borders, currencies, and cultures. And once it mastered that playbook in Europe, taking it global was less a leap than a repeatable process.

VII. The Portfolio Expansion: KAYAK, Agoda, and OpenTable

Building the Travel Conglomerate

Once Priceline had seen what worked in Europe, it leaned into a repeatable strategy: build a portfolio, not a monolith.

The pattern was consistent. Find a strong brand in a new geography or an adjacent part of the travel funnel. Buy it at a price that didn’t require perfection. Fund it. And then—crucially—don’t smother it. Let the local team keep doing what made them win in the first place.

KAYAK was a perfect example. In 2013, Priceline acquired the meta-search engine for about $1.8 billion. KAYAK didn’t try to be the hotel booking desk itself. It was the comparison layer—the place travelers went to see options across airlines and travel sites, and then clicked out to complete the purchase somewhere else. That made it strategically useful even in the moments when Priceline didn’t “win” the booking directly. It could still participate in the decision, and it could still learn—about pricing, about demand, and about where travelers were headed next.

Agoda was the geographic counterpart to that logic. Priceline initially acquired it in 2007, then expanded it as its spearhead in Asia. Based in Bangkok, Agoda understood realities that Western travel companies often tripped over: different customer preferences, different payment behaviors, and a hotel landscape that didn’t map neatly onto Europe or the U.S. Instead of forcing a one-size-fits-all Booking.com playbook onto Asia, Priceline let Agoda evolve on its own terms.

Then came the detour that made some observers raise an eyebrow: OpenTable. Priceline acquired the restaurant reservation platform in 2014 for $2.6 billion. The bet was intuitive, even if it wasn’t guaranteed. OpenTable had built real network effects in dining, linking restaurants and diners in a way that rhymed with what Booking.com had done for hotels. It was a move toward a broader “travel and hospitality” footprint, not just a place to sleep.

The Rebrands

As the portfolio grew, the corporate name started to look increasingly outdated. Priceline was still a meaningful consumer brand in the United States, but it was no longer the center of gravity.

So on April 1, 2014, priceline.com Incorporated became The Priceline Group Inc.—an acknowledgement that this was now a multi-brand company, with Booking.com and its international businesses driving most of the growth and profitability.

Four years later, the company made the more honest move. On February 21, 2018, it renamed itself Booking Holdings.

It wasn’t just cosmetic. It was an admission of what the last decade had made undeniable: the child had outgrown the parent. Booking.com was the crown jewel, and the corporate identity finally caught up.

The new name also clarified the strategy. This wasn’t a random pile of travel assets. It was a holdings company built around distinct brands serving different markets and customer segments—while sharing the scale advantages of technology, data, and operational know-how. Diversification without centralization. Autonomy without chaos. And a corporate brand that said, plainly, who was really running the show.

VIII. The Modern Era: AI, Alternative Accommodations & The Connected Trip

The Fogel Leadership Transition

Effective January 1, 2017, Glenn D. Fogel became chief executive officer and president of Booking Holdings. In a way, it completed an arc that had started years earlier with his flights to Europe—meeting founders, touring tiny offices, and trying to figure out which teams were building something real. Now he was running the company those bets had built.

But “dominant” didn’t mean “safe.” Travel was changing again, and this time the threat didn’t look like Expedia or another online agency. It looked like Airbnb. Travelers were increasingly drawn to apartments, vacation rentals, and one-of-one stays that didn’t fit neatly into the traditional hotel box. Booking.com was still built on hotels—but consumer expectations were widening fast.

The Airbnb Response

Booking Holdings didn’t treat alternative accommodations as a quirky corner of the market. It treated it like the next major inventory war.

So it went to work signing up vacation rentals, apartments, and unique properties—building supply at scale, the same way it had done with European hotels years earlier. The goal wasn’t subtle: compete head-to-head with Airbnb, while giving travelers a single place to book both hotels and non-hotels.

By a recent count, Booking.com had grown alternative accommodations listings to 7.9 million, up 8% from the prior year. The positioning was different from Airbnb’s. Where Airbnb leaned into hosts and “live like a local” storytelling, Booking.com leaned into what it already knew how to deliver: breadth of selection, a sense of reliability, and the convenience of having everything alongside the hotel inventory travelers already trusted.

The COVID Crisis

Then the floor dropped out.

COVID-19 hit travel harder than almost any other industry. Borders closed, planes stopped flying, and demand evaporated. For a company that only makes money when people go somewhere, the crisis wasn’t theoretical—it was immediate.

Booking Holdings ultimately laid off nearly 25% of its global workforce as the pandemic crushed travel and made the recovery timeline unknowable. The cuts were brutal, and they were a reminder that even the best online marketplaces are not immune to the world.

But COVID also highlighted a structural strength in Booking Holdings’ model. The company didn’t own hotels. It didn’t own airplanes. It wasn’t sitting on physical inventory that still had to be financed and maintained while customers disappeared. When bookings fell off a cliff, many costs fell with them. The commission-based model that had been a growth engine in normal times also acted like a shock absorber in a once-in-a-century downturn.

When vaccines arrived and travel began to return, Booking Holdings still had what mattered: the technology, the relationships with suppliers, and a global customer funnel ready to reopen. Demand came back fast, powered by a huge backlog of people who hadn’t been able to travel. By 2024, the recovery had fully played out, and Booking Holdings posted record financial results.

AI and the Connected Trip

As travel normalized, the next shift arrived: generative AI. Booking Holdings leaned in, framing it as both a product upgrade and an operational lever. It launched tools like Booking.com’s AI Trip Planner and Priceline’s AI-powered travel assistant, Penny.

The pitch is straightforward: let travelers plan in natural language instead of wrestling with filters. You don’t have to click through endless combinations of dates, neighborhoods, and amenities. You can describe what you’re trying to do—like a romantic weekend in Paris with great restaurants nearby—and get tailored recommendations back.

That ties into the company’s bigger ambition: the Connected Trip. Booking Holdings wants to be more than the place you book a room. It wants to handle the whole itinerary—accommodations, flights, ground transportation, activities, and dining—stitched together into one integrated experience.

The company said connected trip transactions grew more than 40% year over year, a sign that the strategy was gaining traction. And the prize is clear. If Booking Holdings can become the platform travelers rely on from inspiration to arrival to the last reservation, it deepens the relationship, raises switching costs, and captures more of the value of each trip—without needing to reinvent the business that got it here.

IX. Financial Analysis & Business Model Deep Dive

The Revenue Machine

By the end of 2024, Booking Holdings was fully through the post-pandemic whiplash and back in its natural state: printing money off global travel demand. For the year ended December 31, 2024, it reported $23.7 billion in revenue. In the fourth quarter, gross bookings grew 17% and revenue grew 14%—a snapshot of a business that wasn’t just riding a recovery, but benefiting from a model built to scale.

To understand why the company is so powerful, you have to understand how it gets paid.

Most of the time, Booking.com isn’t buying hotel rooms and reselling them. It’s acting like an agent. A traveler books a stay, and the hotel pays Booking Holdings a commission—typically in the 12–15% range—after the guest completes the stay. No inventory to warehouse. No rooms sitting on a balance sheet. Just a cut for making the match.

That structure gives the business some very rare traits at global scale. The unit economics are clean. The capital requirements are low. And once the marketplace is built, an additional booking doesn’t require much incremental cost. The company grows by moving more transactions through a system it already owns: software, relationships, and demand generation.

Marketing Efficiency

If there’s one line item that tells you what kind of company this really is, it’s marketing.

Sales and marketing costs were $10.4 billion in the most recent year—about 72% of total expenses. At first glance, that can look scary, like the company is buying its own growth. But the important detail is what kind of marketing this is.

Booking Holdings is not mainly spending on fuzzy brand campaigns where the payoff is hard to measure. It’s spending on performance marketing: search ads and other channels where you can track outcomes, measure conversion, and adjust in real time. In practice, that means marketing isn’t just an expense—it’s more like cost of goods sold for demand. If the return is there, you spend. If the return isn’t there, you pull back.

The flip side is dependency. Google is one of the most important distribution channels in travel, and it has also become one of the most expensive. As Google has expanded its travel offerings, the bidding wars for visibility have intensified. Booking Holdings can still make the math work—better than most—but the relationship is structural enough that investors watch it closely.

Capital Returns

Because the model is so capital-light, a lot of the cash has nowhere to go except back to shareholders.

Booking Holdings repurchased about $6 billion of stock in 2024, and it still had $7.7 billion remaining under its current authorization. That’s the quiet advantage of a marketplace that doesn’t need to build factories, buy fleets, or finance inventory: once you’ve funded the engine, you can return the excess.

The company also maintained investment-grade credit and has used debt strategically at times, giving it flexibility—both for acquisitions and for continuing those returns programs.

And here’s the punchline that captures what Booking Holdings really is: it ranked 243rd on the Fortune 500 by revenue, despite owning no hotels, operating no airlines, and employing no housekeepers. It’s a distribution and conversion machine—an internet marketplace that figured out how to take a small slice of a massive global industry, over and over again, at scale.

X. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

The Power of Focus

Booking.com won by being “just” accommodations first. While competitors spread themselves across flights, cars, cruises, and activities, Booking.com kept coming back to the same question: how do we get more people to book more rooms, more often?

That focus paid off in the unsexy ways that compound. It helped Booking.com build the deepest supply, refine the booking flow until it was ruthlessly efficient, and develop operational muscle in one category before taking on the next.

The takeaway is almost unfashionable in an era obsessed with platforms and ecosystems: sometimes the best strategy is to pick one thing, become undeniably great at it, and let time do the heavy lifting.

Decentralized Autonomy

Priceline’s most underrated move after the acquisition was not a grand integration plan. It was restraint.

Instead of forcing Booking.com into an American operating system—new processes, new culture, new approvals—Priceline largely let the Dutch team keep running the business. That decision was unusual, and it turned out to be the right kind of unusual. Booking.com moved fast because it didn’t have to ask permission. It kept its edge because it didn’t have to “harmonize” it.

This only works if you can tolerate two hard things at once: humility, because the best answers might not come from headquarters; and patience, because autonomous teams will sometimes make choices that look weird up close, until they don’t.

International First

Europe wasn’t a detour on the way to the “real” market. It was the advantage.

The same fragmentation that made Europe feel messy—different languages, currencies, regulations, and a long tail of independent hotels—created an opening for a company willing to do the work. Booking.com built local-market muscle early, and that experience translated into a repeatable expansion playbook later.

For founders, the point isn’t “start in Europe.” It’s broader: start where the conditions are best for the product you’re building, even if it’s not the most obvious place on the map.

The Agency Model

Booking.com’s commission-based agency model did something deceptively powerful: it turned hotels into partners instead of opponents.

Hotels didn’t feel like Booking.com was taking their margin by reselling their rooms. They felt like they were paying for distribution that worked. That alignment made it easier to win trust, sign up more inventory, and build relationships that lasted—exactly what you need when your marketplace is only as good as the supply behind it.

In marketplace businesses, the economic model isn’t just math. It’s strategy. Merchant models can look better on paper in the short run, but they often introduce friction with suppliers. Commission models can give up some margin, but they buy you alignment—and alignment is what lets the flywheel spin.

A/B Testing Culture

Booking.com treated experimentation as a system, not a slogan. The internal rule was simple: data beats opinions.

That created a culture that reinforced itself over time. People who wanted to win arguments with results thrived. People who wanted to win with status or politics didn’t. And because the company kept running experiments, it kept getting better—constantly, quietly, and at scale.

But cultures like that don’t happen automatically. Leadership has to mean it. Executives have to accept that their favorite ideas will lose to the test. The payoff is an organization that improves by default, year after year, without needing a visionary to guess right every time.

XI. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

Booking Holdings sits in a rare spot: right in the middle of the travel transaction, at global scale. It has assembled the largest accommodation inventory in the world, built the machinery to personalize and optimize the shopping experience, and earned brand recognition across continents. And because this is a marketplace, the advantages stack. More supply brings more travelers. More travelers bring more bookings. More bookings fund more marketing and more local execution, which attracts even more supply.

The big question for any category leader is whether it can expand without losing focus. The early signs in flights have been encouraging. The company reported 52% growth in airline bookings, suggesting it can move beyond accommodations without breaking the core engine. Layer on AI—Trip Planner and conversational assistants—and you get a plausible new moat: a product that feels more helpful, more personal, and more “sticky” the more you use it.

Financially, this is still one of the cleanest models in consumer internet. The commission structure can generate strong margins without heavy capital needs. That cash flow gives management options: reinvest through cycles, buy back stock aggressively, and still keep the balance sheet flexible. The COVID period is the case study they’ll point to here—cutting costs when demand vanished, then being positioned to rebound when travel returned.

Alternative accommodations add another leg to the story. Booking.com has pushed hard into the category Airbnb made famous, with listings nearing 8 million. The strategic upside is straightforward: if a traveler can find both hotels and non-hotel stays in one place—and trust the experience—Booking becomes the default starting point, not just an option.

Through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, you can see why the bull case is so durable. There are marketplace network effects: more properties draw more guests, and vice versa. There are scale economies: technology and platform costs spread across an enormous volume of bookings. There are switching costs on the supply side, especially for hotels that have deeply integrated Booking.com into their operations. And there’s brand: a familiar name that reduces perceived risk for travelers in an inherently high-stakes purchase.

Bear Case

The largest threat is also the gatekeeper: Google. It controls the top of the funnel—how travelers discover where to book—and it has steadily pushed deeper into travel products. Each time Google expands hotel listings or flight search, Booking Holdings risks paying more just to stay visible. That dynamic can act like a structural tax on the business, pressuring margins even if demand stays strong.

Europe is another source of risk, but in a different way. Booking’s dominance on the Continent makes it a natural target for regulators. Rate parity clauses—rules that prevent hotels from offering cheaper prices on their own websites—have already come under fire in some jurisdictions. More regulation could limit pricing power, constrain commercial terms, or add operational friction to a model that historically moved fast.

Then there’s the cost structure behind the growth. Marketing is still the heavyweight, at 72% of expenses. That doesn’t automatically mean the model is broken—performance marketing can be rational if the returns are there—but it does create exposure. If customer acquisition gets more expensive, or if the major channels become less effective, profitability can compress quickly.

Airbnb remains a real brand threat, especially with younger travelers. Millennials and Gen-Z often gravitate toward the “authentic experience” framing that Airbnb owns culturally. Booking.com can offer similar inventory, but matching a brand identity is harder than matching a product category. The question isn’t whether Booking can compete in alternative stays—it can. The question is whether it can become the instinctive choice for the next generation of travelers.

AI is also a double-edged sword. Booking Holdings is investing aggressively, but generative AI lowers the barriers for new experiences to emerge. A clean-slate, AI-native entrant could reimagine travel planning in a way that changes consumer behavior—shifting value away from traditional search, filters, and listings. If that happens, incumbent advantages could weaken faster than the market expects.

Look at the situation through Porter’s Five Forces and you get a mixed picture. Supplier power is relatively low: most hotels need distribution, and no single property has much leverage. Buyer power is moderate: travelers can switch in a few taps, even if habits and loyalty create some inertia. Substitutes are real, from direct booking to alternative platforms. Rivalry is intense—Expedia, Airbnb, and Google are all well-funded and fully motivated. And while building comparable inventory at global scale is difficult, entry is still possible in focused niches or through new product paradigms.

Key Metrics to Monitor

For investors following Booking Holdings, three KPIs are especially worth watching:

Room Night Growth Rate: The heartbeat of the business. If room nights keep climbing, the flywheel is still turning. If growth slows meaningfully, it can be an early signal of share loss, market saturation, or weakening demand.

Take Rate (Revenue/Gross Bookings): A read on value capture. It reflects pricing power, the mix of offerings, and how much Booking can earn per dollar of transaction volume. Compression can indicate commoditization; expansion can signal rising leverage and a stronger product mix.

Performance Marketing ROI: The make-or-break efficiency metric. With marketing the biggest cost line, the key question is whether Booking can keep buying demand profitably. Watching marketing spend relative to revenue, and broader customer acquisition efficiency over time, helps reveal whether the growth machine is compounding—or getting taxed.

XII. Epilogue: What Would Geert-Jan Bruinsma Think?

Picture Geert-Jan Bruinsma in 1996: a student at Universiteit Twente, building a simple website so people could book Dutch hotels online. No venture capital. No manifesto about disrupting an industry. No master plan to conquer travel. Just a practical solution to a practical problem.

Fast forward nearly thirty years, and that side project has become the backbone of the world’s largest travel platform: a company that facilitates more than a billion room nights a year, employs thousands of people across dozens of countries, and has grown into a public-market heavyweight.

The arc from Bookings.nl to Booking Holdings can feel like an accident—at least compared to the clean, cinematic stories we like to tell about tech empires. The Priceline acquisition might not have happened at all. Expedia was in the mix. Priceline could have “integrated” Booking.com the way acquirers usually do, smoothing out the edges until the thing that made it special was gone. Booking.com’s experimentation-first culture could have been replaced with hierarchy, politics, and opinion.

Any one of those turns might have produced a very different company.

And yet, when you look back, parts of this story also feel strangely inevitable. The agency model aligned incentives in a way the merchant model struggled to match. Europe’s fragmented hotel market created a massive opening for a platform willing to do the unglamorous work, property by property. And the obsession with execution—testing, iterating, measuring—kept compounding into an advantage that competitors could understand but rarely replicate.

Booking Holdings’ mission today is “to make it easier for everyone to experience the world.” It’s the kind of line a student in Enschede might roll his eyes at. But it’s also not that far from the original impulse. Bruinsma wanted to make booking hotels easier. The company that grew from that idea wants to make the whole trip easier. Same thread, just pulled to a much larger scale.

The future, of course, is not guaranteed. Google keeps pushing deeper into travel. Airbnb still owns a powerful cultural brand, especially with younger travelers. Regulators in Europe keep looking harder at gatekeepers. And AI is rewriting how people search, plan, and decide—potentially shifting value away from the very interfaces Booking.com mastered.

But the underlying principle that built Booking.com still matters: the best marketplaces get built when incentives line up. When suppliers win as the platform wins. When customers get more value as the business grows. When a company chooses relentless execution over elegant theories.

That might be the real lesson of this whole saga. Jay Walker had a sweeping vision that almost drove Priceline off a cliff. Geert-Jan Bruinsma built something small that worked, and it scaled into an empire. Sometimes the businesses that endure aren’t the ones that announce themselves with destiny. They’re the ones that keep solving the next problem—quietly, obsessively—until the world wakes up and realizes what they’ve become.

XIII. Recent News

Booking Holdings entered 2026 with momentum still intact. In the fourth quarter of 2024, gross bookings rose 17% and revenue increased 14%, a sign that demand stayed strong across regions even as the travel market normalized.

The company also pointed to progress on its “connected trip” ambition—getting travelers to book more than just a room. Connected trip transactions grew more than 40% year over year, suggesting more customers were using the platform to stitch together multiple parts of their journey.

On the product front, generative AI moved from buzzword to shipping features. Booking.com’s AI Trip Planner expanded to handle more complex itinerary requests and deliver more personalized recommendations. Priceline’s AI assistant, Penny, kept improving too, with stronger natural-language capabilities aimed at making planning and booking feel more conversational.

And the machine kept doing what it does when it has excess cash: returning it. Booking Holdings reiterated its capital return posture, with $7.7 billion still available under its share repurchase authorization. At the same time, management acknowledged the reality of the competitive landscape—especially as Google continued expanding its travel offerings, raising the stakes for distribution and customer acquisition.

XIV. Links & References

SEC filings: - Booking Holdings Form 10-K Annual Report (2024) - Booking Holdings quarterly earnings reports and investor presentations - Booking Holdings proxy statement

Key sources: - “The Early History of Booking.com” (industry histories and recollections from former employees) - Interviews with Glenn Fogel, CEO, Booking Holdings - Acquired.fm episode archives on travel and marketplace businesses

Industry reports: - Phocuswright research on online travel agency market share - Skift research on global travel trends - Morgan Stanley analysis of online travel competitive dynamics

Academic resources: - Platform economics research from MIT and Stanford - Network effects analysis in marketplace businesses - Hamilton Helmer, 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music