Baker Hughes: The Energy Technology Transformation Story

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

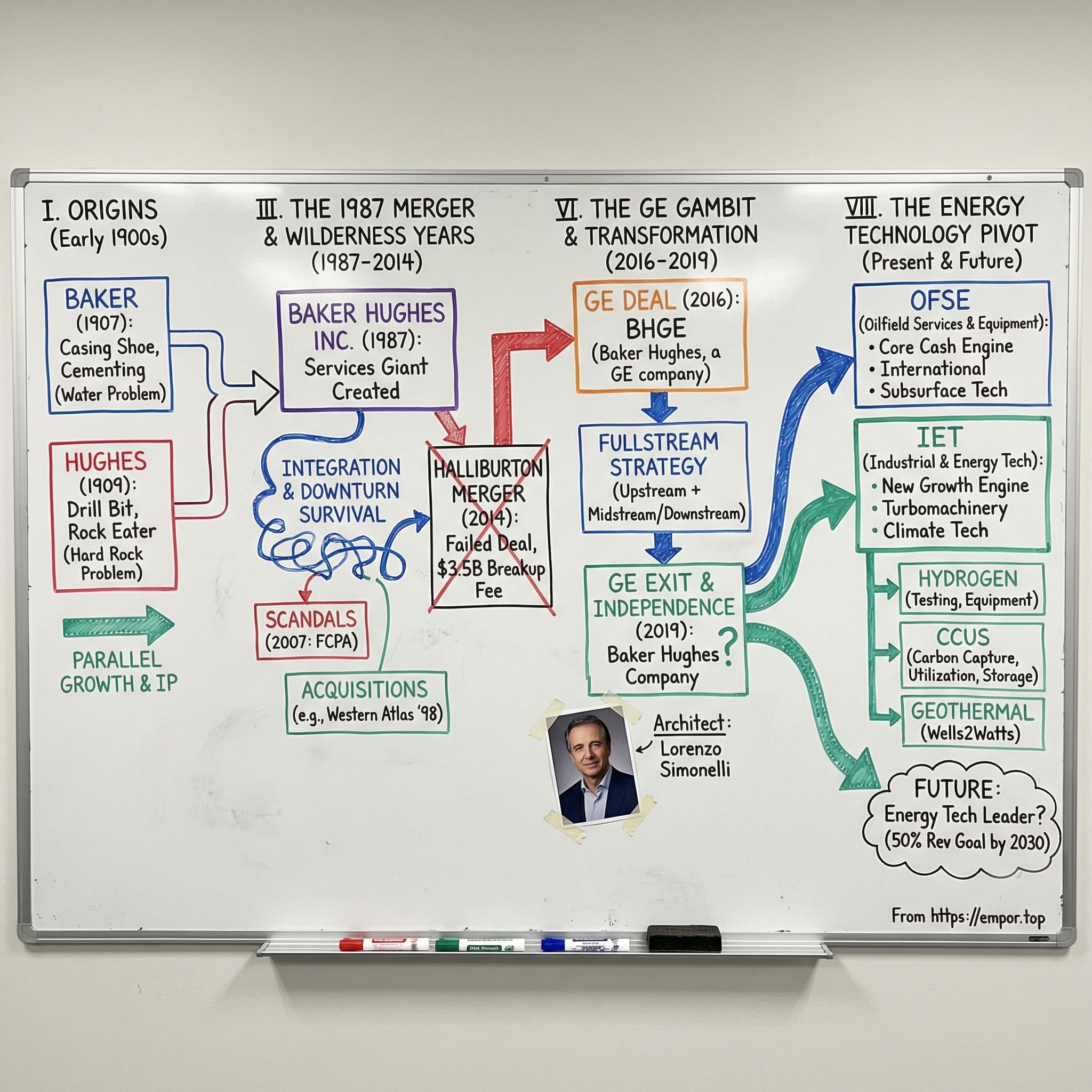

Picture a boardroom in Houston in October 2019. Executives file in to watch something you almost never see in corporate America: a company changing its name for the third time in three years. Baker Hughes, a GE company—BHGE—was becoming simply Baker Hughes Company again.

On paper, that sounds like branding. In reality, it was a flag in the ground. The GE experiment was effectively over, GE was heading for the exits, and what remained was a new kind of Baker Hughes—no longer just an oilfield services heavyweight, but a hybrid built from a century-old drilling-and-services business fused with GE’s industrial turbomachinery DNA. The bet was straightforward: whatever pace the world chose for the energy transition, Baker Hughes would have a way to win.

Today the company operates in two segments: Oilfield Services & Equipment (OFSE) and Industrial & Energy Technology (IET). Together, they generate $27.8 billion in trailing twelve-month revenue. Baker Hughes still sits in the “Big Three” of oilfield services alongside Schlumberger and Halliburton. But the more interesting part of the story is what makes it unlike its two peers: a major industrial equipment franchise—turbines, compressors, pumps—and a growing toolkit aimed at lower-carbon energy, including hydrogen, carbon capture, and geothermal.

That sets up the central question of this story: how did a company born from early-1900s drilling innovations survive a century of booms and busts, mergers and missteps, scandals and strategic drift—and still manage to reposition itself for the biggest shift in energy since the industry began?

To answer it, we’ll follow two origin stories that ran in parallel for decades before colliding. We’ll go through the bruising 1987 merger that created the modern Baker Hughes, then the wilderness years that followed. We’ll unpack the Halliburton deal that almost happened—and the GE deal that did, reshaping the company in ways a traditional oilfield-services merger never could. And we’ll meet Lorenzo Simonelli, the GE lifer who became the architect of Baker Hughes’s reinvention.

This isn’t just a corporate history. It’s a playbook for how a legacy company can survive disruption by leaning into it—turning existential threats into optionality. And by the end, we’ll test the question that matters now: is Baker Hughes’s new positioning as defensible as it looks, or is it simply a clever narrative layered on top of a cyclical, unforgiving business?

II. The Twin Origin Stories: Baker & Hughes

In 1907, the oil business had a problem that sounds small until you realize it was killing wells: water. Underground pressure would push groundwater into the reservoir, flooding out the oil and turning a productive well into a write-off—sometimes in months. Everyone understood what had to happen in theory. You had to seal the space between the steel casing and the rock. In practice, nobody had figured out how to do it reliably.

Reuben Carlton Baker, a California oilman with an engineer’s obsession, focused on that gap.

His breakthrough wasn’t some grand new idea. It was a piece of hardware—and the details were everything. Baker designed a metal shoe that fit on the bottom of the casing and helped place cement exactly where it needed to go. Paired with his “float equipment,” it let cement flow down the casing and out into the annular space without reversing back up the pipe. That one-way control was the difference between “we tried cementing” and “we can cement every time.”

Suddenly, drillers could isolate oil zones from water zones. Wells that might have declined fast could keep producing for years. Baker wasn’t drilling wells; he was selling certainty to the people who did.

In 1913, he incorporated Baker Casing Shoe Company in California—named with the plainspoken confidence of someone who knew he’d built something indispensable. The model was as durable as the invention: be the technology supplier who makes the whole industry work better, without taking exploration risk yourself. That posture—tools, not wildcat bets—would carry through every boom, bust, and reinvention that followed.

While Baker was solving the water problem, another inventor was fixated on a different enemy: rock.

Howard Robard Hughes Sr. had come to the Texas oil fields around 1900. He started as a lawyer, but the machinery of drilling pulled him in. The bits of the day were basically sharpened steel that scraped and gouged their way downhole. They were fine in soft formations and miserable in hard ones. And hard rock stood between drillers and a lot of the most valuable reservoirs.

In 1909, Hughes introduced the first roller cutter bit. Instead of scraping, it used rotating cones studded with hardened teeth—crushing and chipping the formation as it rolled. The motion changed everything. It’s the difference between dragging a sharp point across concrete and using a grinding wheel. Hughes’s “rock eater” could drill through formations that had stalled everyone else.

He incorporated Hughes Tool Company that same year. And because Hughes didn’t just invent the technology—he patented it thoroughly—he didn’t just have a better product. He had a tollbooth. For years, anyone who wanted to sell effective roller cone bits had to license Hughes’s patents or attempt a workaround. But the key ideas were protected so comprehensively that “workaround” mostly meant “inferior.”

Hughes Tool became a machine for printing cash. And that’s where the story swerves from oilfield engineering into American folklore.

When Hughes Sr. died in 1924, his eighteen-year-old son, Howard Hughes Jr., inherited most of the company. The younger Hughes would become one of the century’s most notorious figures—aviator, filmmaker, casino owner, and eventually a recluse. But the money that powered the planes, movies, and Las Vegas ambition didn’t come from Hollywood. It came from drill bits. Those spinning cones chewing through Texas rock funded Hughes Aircraft, TWA, and everything else that made Howard Hughes Jr. a legend.

Over the decades, Baker and Hughes built their power in the same way—through invention and control of critical technology—but they evolved differently.

Baker expanded. It bought its way into adjacent categories and built capabilities in cementing, completion tools, and drilling fluids. By the 1960s, renamed Baker International, it had become a broad oilfield services player with global reach.

Hughes stayed more concentrated, continuing to lead in drill bits. Even after its core patents aged out, the engineering expertise and installed reputation were hard to match. But the company’s ownership story became complicated. Howard Hughes Jr. grew increasingly detached from reality and from management. After he died in 1976, Hughes Tool was no longer guided by the Hughes family at all—still technically strong, but without the kind of clear strategic hand that had built the empire in the first place.

By the early 1980s, both companies had vulnerabilities that the next cycle would expose. Baker International had grown into a patchwork—more a confederation of acquisitions than a single integrated machine. Hughes Tool had world-class products but a drifting sense of what it wanted to be. And the industry was heading into a downturn brutal enough to force consolidation.

That’s the throughline from the very beginning: neither founder made money by finding oil. They made money by making oil possible. Baker and Hughes built moats through engineering and intellectual property, and they positioned themselves as essential suppliers to the entire value chain.

In a century defined by volatility, that DNA mattered. And it’s exactly why, when the industry finally demanded scale and survival, these two pioneers were destined to become one.

III. The 1987 Merger: Creating a Services Giant

By the time the calendar flipped to 1986, the oil industry thought it understood chaos. It had lived through the 1973 embargo. It had watched Iran explode into revolution. It had recalibrated to new supply from the North Sea and Alaska. What it didn’t fully appreciate was how fragile the whole price system was when one player got tired of playing referee.

Saudi Arabia had spent years acting as the swing producer—cutting its own output to defend prices while other OPEC members quietly pumped over quota. In late 1985, it had had enough. Saudi opened the taps, and in a matter of months the market broke. Oil fell from roughly the high twenties to under ten dollars a barrel.

The downstream effects were immediate and brutal. Drilling rigs were stacked. Service fleets built for the early-’80s boom sat idle. Bankruptcies tore through Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. Banks that had lent against reserves and optimism failed. Houston—fresh off a skyscraper boom—watched real estate values crater.

For Baker International and Hughes Tool Company, this wasn’t just a downturn. It was the kind of reset that forces a question every cyclical industry eventually asks: do you want to be big enough to survive the next shakeout, or do you want to be acquired by someone who is?

Both companies watched revenue slide and share prices sink. And at the same time, the logic of combining got harder to ignore. Baker was strong in completion and production services—the work that happens after the hole is drilled. Hughes was the drilling technology powerhouse—the bits and tools that got you there in the first place. Put them together, and you could offer customers something close to end-to-end capability across the well lifecycle. Talks started in late 1986.

The deal, announced in early 1987, was pitched as a merger of equals: Baker International and Hughes Tool would combine in a $728 million stock transaction to form Baker Hughes Incorporated. The story was simple and compelling. Hughes would cut the rock; Baker would cement, complete, and keep the well producing. In an industry suddenly obsessed with efficiency, breadth looked like a weapon.

But in oilfield services, announcing a merger is often the easy part.

Regulators stepped in. The Federal Trade Commission worried the combined company would be too powerful in certain tool categories and demanded meaningful divestitures. Then, as oil prices bounced a bit in early 1987, doubt crept in on the Hughes side. Hughes’s board started questioning whether the terms still made sense. At one point, Hughes formally tried to walk away. Baker responded with a $1 billion lawsuit, and what began as a “strategic combination” turned into a public brawl.

That drama made good headlines, but it didn’t change the underlying reality: both businesses needed scale. Their overlap was limited—Hughes skewed drilling, Baker skewed completion—so there was less obvious redundancy than in many oilfield mergers. Their footprints complemented each other, too, with Baker stronger internationally and Hughes more dominant at home. The industry was consolidating, and neither company wanted to be left on the wrong end of it.

In the end, the consent decree forced divestments, the lawyers got paid, and the core deal went through. Baker Hughes Incorporated officially came into existence on April 3, 1987. Baker’s CEO, James D. Woods, took the chairman role initially as leadership rotated through the messy work ahead. The new company had about 21,000 employees and operations spread across nearly every oil-producing region on earth.

Then came the part that mergers always underestimate: integration.

Hughes Tool, at its core, was a product company—manufacturing, engineering discipline, distribution. Baker had become a services company—field crews, on-site problem solving, and the constant improvisation of operations in harsh environments. Those mindsets didn’t just differ; they collided. Hughes engineers saw Baker’s field culture as loose and undisciplined. Baker’s service leaders saw Hughes as overly rigid, too focused on the factory and not enough on the customer’s emergency at 2 a.m. Middle managers fought over process, territory, and headcount.

And the market didn’t make it any easier. Oil prices stayed weak through the late 1980s and into the early 1990s. The consolidation that drove the merger didn’t stop when the ink dried—it accelerated. Baker Hughes got good at the grim mechanics of survival: layoffs, facility closures, cost cuts, and the constant balancing act of preserving technical capability while shrinking the cost base.

Still, the merger created something neither company could have built on its own: a platform. And Baker Hughes used it.

Through the late ’80s and ’90s, the company bought aggressively to fill gaps and expand its menu. Brown Oil Tools, CTC, EDECO, and Elder Oil Tools strengthened completion offerings. Milchem and Newpark added drilling fluids. EXLOG brought well logging. Eastman Christensen and Drilex expanded directional drilling. Teleco added measurement-while-drilling capability. Wilson and Tri-State bolstered manufacturing capacity.

A few deals were especially consequential. Centrilift, acquired in 1987, brought electric submersible pumps—critical artificial lift technology as fields matured and needed help to keep flowing. Chemlink and Petrolite added chemicals. And in 1998, Baker Hughes bought Western Atlas in a $5.5 billion transaction, adding seismic services, well logging, and more of the high-tech toolkit that oil companies increasingly relied on.

Over time, those moves turned Baker Hughes from “Baker plus Hughes” into something bigger: a genuinely integrated services company. By the mid-1990s, it could provide most of what a customer needed to drill, complete, and produce a well. Only Schlumberger and Halliburton could claim similar breadth, cementing the “Big Three” structure that still defines the industry.

That breadth matched where the customer was going. Oil companies increasingly outsourced technical work to specialists, choosing to concentrate on exploration decisions and portfolio management. And they didn’t just want vendors who showed up with one tool—they wanted partners who could manage larger chunks of a well program. Baker Hughes could now bid on integrated contracts that smaller competitors simply couldn’t.

In hindsight, the 1987 merger didn’t just create a bigger company. It trained Baker Hughes for the next several decades. It learned how to integrate acquisitions, how to operate through brutal cycles without gutting its technical core, and how to build durable relationships with the majors and national oil companies. Those muscles—built in the turbulence of the late ’80s and ’90s—are part of what later made the GE combination possible, and part of why Baker Hughes is still standing as a major player today.

IV. Growth, Scandals, and Near-Death: The Wilderness Years

The 1990s should have been Baker Hughes’s decade. The merger was done. The shopping spree had filled in the product catalog. The company had the scale, the customers, and a seat at the table with Schlumberger and Halliburton.

And yet, instead of a clean march upward, the next twenty years turned into something messier: a strategic fog. Baker Hughes kept shifting its posture—services company one year, equipment manufacturer the next—without a clear, durable identity.

Nothing captures that zigzag better than the BJ Services saga. BJ was the pressure pumping and cementing business—exactly the kind of frontline capability that becomes existential when the industry swings toward shale. But in 1990, Baker Hughes decided it didn’t fit and spun it off. The market liked the “focus” story.

Then, in 2010, Baker Hughes reversed itself and bought BJ back for $5.5 billion. The reaction this time was more skeptical: why pay to reassemble something you chose to dismantle? And then, after the GE merger in 2017, the pressure pumping business was sold again. The pattern was hard to miss. Baker Hughes could execute transactions; it struggled to hold a steady strategy long enough to compound the benefits.

Worse than strategic indecision was the reputational damage that hit in 2007, when Foreign Corrupt Practices Act violations came to light. Investigators found that employees had routed bribes to Kazakh officials to win oilfield services contracts—about $5.2 million in payments funneled through an agent who then passed money along to government officials. The conduct traced back to 2001, before CEO Chad Deaton took the top job, but it landed squarely on his watch.

Baker Hughes pleaded guilty to criminal charges and agreed to pay $44.1 million in fines and penalties—one of the largest FCPA settlements at the time. It entered into a deferred prosecution agreement, accepted oversight requirements, tightened internal controls, and committed to ongoing reporting to the Department of Justice. For years, leadership had to answer a question that’s brutal in any trust-based, relationship-driven industry: why should customers and investors believe this won’t happen again?

The scandal exposed what rapid acquisition had quietly created: a fragmented company. Different units operated with different norms. Field teams faced intense pressure to win in competitive markets. And the compliance function hadn’t scaled fast enough for the geographic sprawl. It wasn’t just a legal issue—it was an operating-system issue.

All of this was happening while the industry itself was being rewritten. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing were turning shale into the growth engine of North America. The winners would be the companies that could do high-volume work, fast—fracturing fleets, crews, pad operations, and an industrial rhythm built for repetition.

Baker Hughes, optimized for complex offshore and international work and built around an integrated-services model, didn’t pivot quickly enough. Halliburton and Schlumberger leaned into the new demand, building capacity and staffing up. Baker Hughes lagged and bled share in the fastest-growing arena. By 2014, North American margins had deteriorated, and the pressure to prove a credible path forward was mounting.

There were real strengths amid the drift. The engineering was still world-class. In 2001, Baker Hughes introduced the largest fracking proppants vessel for deepwater Gulf of Mexico operations—a reminder that the company could still do hard, technical things even when its strategy was fuzzy. And the drill bit franchise, the inheritance of Hughes’s original breakthrough, kept evolving, including through polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) designs that outperformed competing approaches.

Internationally, Baker Hughes also had something valuable: steadier business. Positions in the Middle East, West Africa, and Asia-Pacific provided resilience when North America got brutally competitive. Those customers cared more about technical depth and long-term continuity than about shaving every last basis point off a commoditized service line.

Still, by 2014, CEO Martin Craighead was running a company that was profitable—but lacked a clear claim to leadership. Baker Hughes wasn’t bad at anything. It just wasn’t unmistakably best at anything, either. In a world where Schlumberger and Halliburton were increasingly setting the tempo, Baker Hughes was becoming the odd one out—the Big Three starting to feel like a Big Two plus one.

Something dramatic was needed. And the next chapter delivered it.

V. The Halliburton Merger That Wasn't

November 2014. Oil prices had started sliding hard—off the hundred-dollar highs and heading toward fifty. Plenty of executives treated it like the usual kind of pullback: ugly, but survivable. Martin Craighead at Baker Hughes and Dave Lesar at Halliburton read it as something more structural. If the floor was about to drop out, they didn’t want to be forced into a defensive crouch. They wanted to set the terms of the next cycle.

So on November 17, 2014, they went for the biggest lever available: a merger. Halliburton agreed to acquire Baker Hughes in a deal valued at $34.6 billion. Baker Hughes shareholders would get $19 in cash plus 1.12 shares of Halliburton for every Baker Hughes share they owned. The pitch was straightforward: put two giants together, take out overlapping costs fast, and come out of the downturn with a stronger, more efficient competitor.

The numbers were eye-catching. The combined company would be headquartered in Houston and would have been massive—big enough to reshape the competitive map. In a market long defined by the “Big Three,” this would have effectively turned it into a “Big Two,” forcing Schlumberger to stare down a single, newly consolidated rival with enormous breadth across drilling and completions.

And that, of course, was the problem.

Regulators weren’t looking at the deal as a clever survival move. They saw it as a fundamental reduction in competition across huge swaths of oilfield services. After a long investigation, the Department of Justice concluded the merger would substantially lessen competition in numerous markets—from drill bits and directional drilling to drilling fluids, completion tools, and more. The companies proposed divestitures, but the DOJ didn’t believe the fixes were enough to undo the concentration.

It wasn’t just Washington. Customers didn’t want it either. Oil companies—ranging from supermajors to smaller independents—warned that collapsing three major suppliers into two would leave them with fewer alternatives and more exposure to pricing power, especially in categories where credible options were already limited.

On May 1, 2016, Halliburton and Baker Hughes terminated the merger agreement. Halliburton paid Baker Hughes a $3.5 billion breakup fee—one of the largest ever—as the price of a deal that couldn’t make it through regulators.

Baker Hughes was independent again. But the company didn’t simply rewind to where it had been in 2014. For eighteen months, leadership teams had planned for a future that would never arrive. People had left. Customers had prepared for a world with one fewer major supplier. And Baker Hughes still had the same underlying question hanging over it: if it wasn’t going to outscale Halliburton or out-tech Schlumberger, what exactly was it going to be?

Craighead later said the experience, as painful as it was, forced clarity. Baker Hughes couldn’t win by being a slightly different version of its two larger peers. It needed a real point of differentiation.

And now it had something else, too: time and money. That $3.5 billion check didn’t solve the identity problem—but it gave Baker Hughes financial flexibility at exactly the moment it needed room to maneuver. Because the next merger conversation wouldn’t be about getting bigger. It would be about becoming something else entirely.

VI. The GE Gambit: Transformation Through Merger

After the Halliburton deal collapsed, Baker Hughes didn’t just go back to business as usual. Martin Craighead started taking meetings with a suitor almost nobody would’ve predicted: General Electric.

GE wasn’t an oilfield services company. It was the great American industrial conglomerate—jet engines, power equipment, big machinery. But through a steady run of acquisitions, GE had built a real presence in oil and gas. GE Oil & Gas made the heavy hardware that sits around the well rather than inside it: turbines, compressors, and other equipment used to move, process, and ultimately use hydrocarbons. And running that division was Lorenzo Simonelli, an Italian-British GE executive with bigger ambitions than being a cog inside a sprawling conglomerate.

At the top of GE, CEO Jeff Immelt saw the oil price collapse as an opening. While other companies were cutting back, he believed GE could buy into the cycle at the right moment. Baker Hughes—fresh off a blocked mega-merger and newly funded by that $3.5 billion breakup fee—was suddenly available, motivated, and big enough to matter. But GE didn’t want a plain-vanilla acquisition. It wanted a combination that could plausibly become the long-term leader in energy equipment and services.

The deal they announced in October 2016 was unlike a typical takeover. GE agreed to merge its Oil & Gas division with Baker Hughes to create a new public company. GE would own 62.5%, and Baker Hughes shareholders would own 37.5%. Not quite a merger of equals, not quite an acquisition either—more like a controlled public company with outside shareholders along for the ride, and with the expectation that the market would impose some discipline.

When the transaction closed on July 3, 2017, the new entity had a new name that tried to make the structure legible: Baker Hughes, a GE company—BHGE. GE contributed its Oil & Gas assets, valued at roughly $22 billion, plus about $7.4 billion in cash. The combined business had more than $22 billion in revenue and a footprint that stretched across the hydrocarbon system.

Craighead and Simonelli branded the strategy with a word that sounded like marketing until you mapped it to the industry: fullstream.

Oilfield services had traditionally lived “upstream”—helping customers drill and produce. GE’s turbomachinery and process equipment skewed “midstream” and “downstream”—moving gas, liquefying it, compressing it, powering facilities. Put the two together and, in theory, you could serve a customer from the reservoir all the way to the burner tip. None of the major competitors could offer that breadth in one package.

The practical implication showed up most clearly in projects like LNG export facilities. Those projects can require drilling wells, then compressing and liquefying the gas, and often generating power on-site. Historically that meant coordinating a cast of vendors: drilling and services providers, equipment OEMs, and power suppliers. BHGE could credibly bid into much larger parts of the project, and—at least in the pitch—optimize the system end-to-end instead of treating each component like a separate transaction.

The logic was bold. The execution was going to be brutal.

Baker Hughes was a field-driven services culture—remote locations, crews that prided themselves on improvisation, and leaders trained to solve messy problems fast. GE’s business was factory-centered and process-heavy, built around engineering rigor and repeatable manufacturing. These weren’t just different styles. They were different instincts.

Even the leadership plan signaled the imbalance. Craighead, who had steered Baker Hughes through the Halliburton saga and then negotiated this deal, became vice chairman. Simonelli became CEO. It made sense—GE was the majority owner and wanted its executive in charge—but it demanded careful handling of ego, identity, and the uneasy question of whose company this really was.

Simonelli turned out to be a fit for the moment. He could speak GE internally, and he knew the energy business well, having led GE Oil & Gas since 2013. He moved quickly to unify operations: cutting duplication, stitching together systems, and trying to keep the best technical capabilities from both sides intact.

But BHGE was trying to integrate in the middle of a cycle that offered no forgiveness. Oil prices were volatile through 2017 and 2018, and neither side of the house—oilfield services or industrial equipment—was operating at full throttle. The usual merger promise of easy cost synergies ran into reality: integration is slow, complicated, and expensive, especially when your end markets can whipsaw quarter to quarter.

Then GE itself began to wobble.

GE’s stock plunged as problems mounted across the broader portfolio. Jeff Immelt left, replaced first by John Flannery and then Larry Culp. With each leadership change came a new wave of speculation about BHGE. Would GE sell its stake? Spin it out? Break the company apart?

By 2019, the direction was unmistakable. GE needed cash and simplicity, and BHGE was a large, liquid asset. GE began selling down its ownership. In October 2019, after GE’s stake dropped below 50%, BHGE dropped the awkward middle name and became Baker Hughes Company—signaling, in a single edit, that the experiment was entering its next phase. GE kept selling and ultimately divested its remaining shares by September 2024.

What GE left behind wasn’t a reverted Baker Hughes. It was a fundamentally different company.

Baker Hughes kept the industrial machinery and technology GE had contributed—turbines, compressors, pumps, valves, and process solutions. It also absorbed capabilities that a traditional oilfield services company typically wouldn’t have prioritized, like digital monitoring and emissions management. Most importantly, the merger gave Baker Hughes a new identity to grow into: an energy technology company, not just an oil and gas services provider.

And if the GE gambit looks messy on the surface—because it was—it still offers a clean takeaway. Complex mergers can work even as the original rationale shifts under your feet. Unconventional deal structures can leave behind durable assets. And in this case, GE’s need to exit didn’t unwind the transformation. It forced Baker Hughes to stand on its own—faster than anyone expected.

VII. Lorenzo Simonelli: The Transformation Architect

The person who would end up reshaping Baker Hughes didn’t come out of the oil patch. Lorenzo Simonelli was born in Tuscany, then grew up in England after his family moved to London. He studied at Cardiff University in Wales—about as far, culturally and geographically, from West Texas rig culture as you can get. And that distance mattered. Simonelli didn’t inherit the industry’s reflexes. He arrived without the usual assumptions.

GE spotted his potential early. In 1994, he joined GE’s Financial Management Program, the company’s demanding rotational pipeline for future leaders. It was a crash course in how GE worked: learn the numbers cold, rotate fast, get measured relentlessly, and keep moving upward if you can perform under pressure. Simonelli could.

From there, his career became a tour through the kinds of businesses that train you to run something complicated. He worked in transportation and heavy manufacturing. He ran operations in Central and Eastern Europe as post–Cold War markets opened up. He led logistics businesses where performance depended on squeezing inefficiency out of sprawling supply chains. None of it was oil and gas—but all of it was operationally intense.

In 2008, Simonelli hit a GE milestone: at 42, he became the youngest division chief in the company’s history and the first non-American to run GE Transportation. That job meant big-ticket equipment, long customer cycles, and demand that swung with the economy—exactly the kind of environment where you learn the hardest leadership skill in industrial businesses: how to cut without breaking what you’ll need when the cycle turns.

Then, in 2013, GE put him in charge of GE Oil & Gas as president. The division had grown through acquisitions—Lufkin Industries, Dresser, and others—but the pieces didn’t automatically behave like one company. Simonelli’s assignment was the unglamorous part: integrate, simplify, and make it coherent enough to compete.

He didn’t get a gentle runway. The oil market cracked in 2014 and kept falling into early 2016. For a capital equipment business like GE Oil & Gas—where customers can postpone orders when budgets tighten—that kind of downturn is a gut punch. Simonelli responded with major restructuring, including cutting about 20% of the workforce, while trying to protect the engineering capabilities that take years to build and minutes to destroy.

That experience shaped the way he talked about energy from then on. He came to believe global demand would keep rising, but that the industry needed to be less cyclical and less dependent on a single commodity story. He started looking for ways GE’s industrial strengths could be applied beyond conventional oil and gas, and toward what was emerging as the energy transition opportunity set.

So when GE and Baker Hughes negotiated their combination, Simonelli was the natural choice to run the new company. He understood GE’s equipment businesses because he had been running them, and he had a front-row seat to the market pressures Baker Hughes lived with every day. And his background helped in another way: Baker Hughes was already a global company, with roughly three-quarters of revenue coming from outside North America. A leader shaped by international markets didn’t have to “go global.” He already was.

As CEO of BHGE—and then CEO of Baker Hughes after GE began exiting—Simonelli pushed a bigger identity than “oilfield services.” He framed Baker Hughes as an “energy technology company”: a business built to help customers produce energy more efficiently and, increasingly, with a lower environmental footprint. It wasn’t a slogan designed to impress ESG investors. It was a strategic claim about where the company could play, especially with GE’s turbomachinery and industrial technology now inside the tent.

The industry noticed. Fortune had named him to its “Forty under Forty” list earlier in his career. Petroleum Economist later recognized him as CEO of the Year for steering the GE combination and guiding the company through its aftermath. His pay package—rising to around $20 million a year by the mid-2020s—reflected the board’s view that the strategy, and the execution risk, were inseparable from the person running it.

People who’ve worked with Simonelli describe a leader who runs on data and discipline, someone who expects strategic proposals to come with real justification. But he’s also known for doing the time-consuming parts of the job that many CEOs try to outsource—showing up with customers, walking operations, talking to employees, and listening for the friction that never makes it into a slide deck.

None of this makes him immune to criticism. Simonelli didn’t invent Baker Hughes’s position in oilfield services, and he didn’t originate the GE deal’s basic structure. And while the energy transition narrative is clear, the company’s revenue still comes overwhelmingly from traditional oil and gas. Transformations like the one he’s attempting don’t resolve in a year or two; they play out over decades, and plenty fail along the way.

But his importance to the Baker Hughes story is hard to overstate. He brought the integration muscle to fuse very different businesses. He brought an international perspective to a company that earns most of its money outside the U.S. And he framed the energy transition as a field of opportunity rather than a slow-motion existential threat. Whether that stance ends up looking prescient or premature is the question that will define the next era of Baker Hughes.

VIII. The Energy Transition Pivot: Becoming an Energy Technology Company

In September 2022, Baker Hughes announced a reorganization that was supposed to look like a simple cleanup of the org chart. It wasn’t. By consolidating the company into two segments—Oilfield Services & Equipment (OFSE) and Industrial & Energy Technology (IET)—Baker Hughes was effectively admitting what the GE years had already made true: this was now two businesses under one roof, serving adjacent markets with very different futures.

OFSE was the heritage engine: tools, services, and equipment that help customers drill wells, complete them, and keep them producing. IET was the newer identity: turbomachinery, industrial equipment, and the technologies Baker Hughes wanted to scale in a world that was demanding lower-carbon energy. Both mattered. But they didn’t move to the same rhythm, and they didn’t win in the same way.

The pivot wasn’t framed as an abandonment of oil and gas. It was framed as a refusal to be trapped by it. Simonelli’s bet was that Baker Hughes couldn’t just ride a long, slow decline in oilfield activity and call it a strategy. If the world’s energy mix was going to change, the company needed new growth lanes—hydrogen, geothermal, carbon capture, and emissions abatement—treated not as side projects, but as priorities that could earn real capital and real talent.

Hydrogen was the cleanest example of how Baker Hughes intended to play the transition without pretending it could rewrite physics.

The company had been around hydrogen in some form since the 1910s, when refineries used it in processing. Baker Hughes built equipment that could handle it—compressors, pumps, valves—but for most of the 20th century hydrogen was an industrial input, not a fuel. The “hydrogen economy” idea—hydrogen as an energy carrier that could displace fossil fuels—changed the size of the prize.

Baker Hughes positioned itself across the hydrogen value chain, leaning into what it already knew how to do. Production and liquefaction required compression and pumping. Transport required pipelines, monitoring, and specialized valves. Storage required cryogenic systems. Power generation required turbines that could burn hydrogen, either blended with natural gas or eventually on their own. And hydrogen’s quirks—metal embrittlement, leakage through seals—made those components harder than they sound, which is exactly the kind of engineering difficulty an incumbent wants.

One of Baker Hughes’s strongest proof points came from well before hydrogen was fashionable. In 2009, the company became the first in the world to test turbines at 100% hydrogen at the Fusina Hydrogen Power Project in Italy. It wasn’t a commercial breakthrough—hydrogen combustion didn’t pencil out economically at the time—but it created a credibility marker that’s hard to manufacture later: they had already done the hard test.

That technical story became tangible in Florence, Italy, where Baker Hughes built a hydrogen testing facility that could run equipment at full load on 100% hydrogen, at pressures up to 300 bar, with storage capacity for 2,450 kilograms of hydrogen. For customers, that matters. Hydrogen projects are expensive, politically visible, and operationally risky. A place where you can watch your equipment run in realistic conditions before you bet the farm is a real selling point.

Carbon capture, utilization, and storage—CCUS—was a different kind of opportunity, and arguably even more aligned with Baker Hughes’s DNA.

Some emissions are easy to talk about and hard to eliminate. Refineries, chemical plants, cement, steel—these are processes where electrification often doesn’t solve the core chemistry. Capturing the CO₂, transporting it, and storing it underground (or using it in products) is one of the few credible pathways to cut emissions without shutting down the industrial economy.

This is where Baker Hughes’s oilfield heritage suddenly looked less like baggage and more like a toolkit. A carbon storage well is, mechanically, a well. The company already knew how to drill, cement, complete, and manage subsurface pressure. Technology used to locate and evaluate hydrocarbon reservoirs could also help identify storage reservoirs. Designs that isolate zones in producing wells could isolate injection zones in storage projects. The molecule changed. The workflow didn’t.

In 2022, Baker Hughes acquired Compact Carbon Capture (3C), a specialist in compact carbon capture systems. Beyond the IP and engineering talent, the signal mattered: Baker Hughes wasn’t only repackaging existing equipment and calling it “transition.” It was willing to buy dedicated CCUS capability.

And then the company started adding a digital layer. In September 2024, Baker Hughes launched Carbon Edge, a platform designed to connect subsurface and surface data across CCUS infrastructure and provide real-time monitoring from capture through transport and storage. The pitch wasn’t “we have a dashboard.” It was more practical than that: if CCUS is going to scale, operators and regulators need to know where the CO₂ is, detect leaks or inefficiencies, and produce credible reporting. Carbon Edge was meant to make the system operable, not just theoretically possible.

Geothermal offered a third transition lane—one that, on paper, looked especially natural for an oilfield services company.

The same basic capabilities that get you to hydrocarbons—drilling through hard formations, completing wells in hostile environments, managing flow and pressure—also get you to heat. Geothermal projects still need wells. They still need high-temperature tools. And they still need service companies that can perform reliably in the field.

One of the most interesting ideas was Wells2Watts, a consortium announced with Continental Resources, INPEX, and Chesapeake Energy. The goal: convert existing oil and gas wells to geothermal production. Across North America, there are thousands of wells that were drilled for hydrocarbons and later became uneconomic. Many already reach depths and formations that could be useful for geothermal. If you can repurpose the well instead of drilling a new one, you can dramatically change the economics.

To support this, Baker Hughes built a geothermal test facility at its Energy Innovation Center in Oklahoma City, including a 300-foot wellbore with electric heaters that can simulate geothermal conditions by heating the inner bore to 450 degrees Fahrenheit. The point was straightforward: test equipment designs and validate performance before deploying them into real geothermal projects where failure is expensive.

All of this sat under a corporate umbrella goal: a net-zero commitment by 2050, with an interim target of a 50% reduction by 2030. Baker Hughes also launched Carbon Out, an internal program aimed at engaging its roughly 54,000 employees in finding emissions-reduction opportunities—ranging from simple facility changes to more complex process redesigns.

For investors, this positioning cuts both ways. The upside is obvious: if hydrogen, CCUS, and geothermal scale meaningfully, Baker Hughes wants to be one of the few companies that can sell not just components, but systems. The downside is just as real: these markets are still early, still policy-sensitive, and still full of “promising” technologies that never become profitable at scale. Meanwhile, the cash engine remains traditional oil and gas, which faces long-term structural pressure.

Baker Hughes has been explicit about how ambitious this is. Management has targeted getting to 50% of revenue from energy transition and industrial technology by 2030, up from roughly 15% today. That would require new businesses to grow fast—fast enough to matter—while the core oilfield portfolio likely stops being a rising tide. That’s the trade: the company is buying the option on a very different future, and it has to execute in two worlds at once.

IX. The Two-Segment Strategy Deep Dive

To understand Baker Hughes now, you have to hold two different businesses in your head at the same time. OFSE and IET sit under one ticker, share customers, and increasingly show up together on the same projects. But they behave differently, compete in different arenas, and win for different reasons.

One is a field-first, cycle-driven oilfield services and equipment business. The other is a project-based industrial equipment franchise with a growing set of “climate tech” offerings layered on top. Put differently: one lives and dies by rigs and completions activity. The other runs on multi-year capital projects, manufacturing throughput, and backlog.

OFSE: Oilfield Services & Equipment

Oilfield Services & Equipment is the direct descendant of Baker’s casing shoe and Hughes’s drill bit: the technologies and crews that help customers drill wells, complete them, and keep them producing.

OFSE is organized around four product lines that roughly trace the life of a well. Well Construction covers drill bits, drilling fluids, and directional drilling—getting the hole drilled where it needs to go. Completions, Intervention & Measurements is the set of tools and services that turn a drilled well into a producing well, and then keep it producing: perforating, isolation, downhole monitoring, and workover-type interventions. Production Solutions is the “keep it flowing” business—artificial lift, chemicals, and ongoing wellbore management. And Subsea & Surface Pressure Systems is the high-pressure hardware—valves, wellheads, blowout preventers, and related systems—especially critical in deepwater and other harsh environments where failure is not an option.

What’s easy to miss if you mostly follow U.S. shale is how international this business is. Roughly three-quarters of OFSE revenue comes from outside North America, largely tied to national oil companies and major integrated producers running long-cycle projects. Those customers care about technical differentiation, reliability, and continuity. They’re not immune to price pressure, but they don’t buy the way a shale operator buys, where speed and unit cost can dominate everything.

In terms of competitive set, OFSE is in the ring with the familiar names: SLB and Halliburton. SLB is the technology benchmark, with the deepest portfolio of proprietary tools and the biggest R&D commitment. Halliburton is the North American land powerhouse, built for the shale era’s high-intensity operating tempo. Baker Hughes tends to slot between them—more international than Halliburton, and competing on a mix of technology and breadth.

Financially, OFSE looks like what it is: a cyclical oilfield business. After the 2015–2016 collapse, the segment’s performance steadied and operating margins recovered into the mid-teens. But the basic physics don’t change. When oil prices fall, customers cut drilling and completion budgets, and OFSE feels it quickly.

The twist—and the reason OFSE still matters in the “energy technology” narrative—is that its core capabilities travel better than you’d think. Geothermal still needs drilling and completions, just for heat instead of hydrocarbons. CCUS still needs wells and subsurface integrity, just for injected CO₂ instead of produced oil. OFSE is the part of Baker Hughes that knows how to put steel in the ground, seal it, monitor it, and manage pressure over time. If the transition involves the subsurface, OFSE has a seat at the table.

IET: Industrial & Energy Technology

Industrial & Energy Technology is the GE inheritance—and the platform Baker Hughes is trying to grow into a different kind of company.

At its core is Gas Technology Equipment: turbines, compressors, pumps, valves, and the machinery that moves and processes molecules. This is not “oilfield services” in the traditional sense. It’s industrial equipment that serves energy and industrial customers—utilities, pipeline operators, LNG developers, and plant operators.

That difference matters because the business model is different. OFSE is tied to activity levels: rigs up, revenue up; rigs down, revenue down. IET is tied to projects and manufacturing cycles. Orders can take years to convert into delivered equipment. The revenue cadence is less about next month’s frac spreads and more about project timelines, factory schedules, and long-term service contracts. That’s why backlog is such a big deal in IET. With IET’s backlog currently at a record $32.4 billion, the segment has a level of forward visibility that OFSE simply can’t replicate.

Then there’s Climate Technology Solutions—the bucket that holds Baker Hughes’s newer growth bets: hydrogen, CCUS, geothermal, and emissions monitoring and abatement. It’s still smaller than the gas technology equipment franchise, but it’s where management wants to build a second act, and where Baker Hughes is trying to prove it can sell more than legacy machinery into legacy markets.

The competitive landscape here changes, too. IET doesn’t primarily compete with SLB and Halliburton. It competes with industrial and power equipment heavyweights like Siemens Energy, with GE Vernova in parts of the turbine and power equipment world, and with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and other manufacturers across specific product categories. In climate tech, the rivals can be narrower specialists—companies like Aker Carbon Capture and ITM Power—depending on the project and the technology.

Economically, IET is also the segment with the cleaner margin story. Management has been pushing margins upward toward a 20% target, helped by operational improvements and mix. The manufacturing and backlog dynamics give IET levers—planning, utilization, service attach—that oilfield services rarely gets to pull.

The simplest way to think about the two segments is this: OFSE is the cash-generating, cycle-exposed core. IET is the longer-duration, higher-visibility business that can expand margins and—if the transition markets truly scale—reshape how investors value the whole company. To underwrite Baker Hughes, you have to underwrite both, separately, and then decide whether the combination is a distraction or an advantage.

X. Technology Leadership & Innovation

In a nondescript industrial building on Houston’s west side, Baker Hughes metallurgists are working on a problem that sits right at the center of the hydrogen economy: hydrogen embrittles steel. The molecules are so small they can slip into the metal itself, collect along grain boundaries, and slowly weaken components that look perfectly fine—until they crack. It’s why a pipeline that’s carried natural gas for decades can become a different kind of risk the moment you ask it to carry hydrogen. Baker Hughes’s materials teams have been developing new alloys, coatings, and testing protocols meant to make hydrogen infrastructure durable enough to be trusted.

That work is a good snapshot of how Baker Hughes tends to innovate. The company doesn’t bet the farm on a single moonshot. It builds a portfolio: multiple technical paths, some incremental, some ambitious, spread across the parts of the energy system that are most likely to change. Some of those bets will pay off. Others won’t. The point is resilience—because in energy, the “future” rarely arrives on schedule.

Carbon Edge is the digital layer of that approach. Launched in September 2024, it’s designed to connect subsurface and surface data across an entire carbon capture, utilization, and storage system. Think about what a real CCUS project looks like in practice: capture at an industrial site, compression, a pipeline run, then injection into a storage formation. Historically, each piece comes with its own monitoring tools and its own data silo. Carbon Edge is meant to stitch those together so operators can see, in one place and in real time, where the CO₂ is and how the whole chain is performing.

It also tackles a harder requirement: proving containment. As regulators tighten expectations, CCUS operators have to demonstrate that captured carbon stays captured—that it isn’t leaking from pipelines, escaping at the well, or migrating unexpectedly underground. Carbon Edge is positioned as the measurement, monitoring, and verification backbone for that work. It’s not just software to run operations. It’s software to satisfy oversight.

Flare.IQ goes after a different emissions problem: the methane that can escape during flaring and venting. Facilities have long used flares to burn excess gas—converting methane, which is highly potent as a greenhouse gas, into carbon dioxide, which is less potent but still an emission. Flare.IQ uses artificial intelligence to monitor flare performance in real time, aiming to keep combustion complete and reduce methane slip. When conditions shift—wind, flow, gas composition—the system can adjust operating parameters or alert the operator.

The geothermal test well in Oklahoma City shows the same philosophy in physical form: prove it before you deploy it. The facility simulates geothermal conditions more realistically than a lab setup, giving engineers a place to validate equipment designs, work through operating procedures, and train teams in a controlled environment before real projects put capital—and reliability—on the line.

Partnerships extend that reach. Baker Hughes made a minority strategic investment in GreenFire Energy to get exposure to advanced closed-loop geothermal. In closed-loop designs, fluid circulates through underground heat exchangers without directly mixing with reservoir fluids—an approach that can sidestep some of the scaling and corrosion issues that have challenged conventional geothermal. The appeal is straightforward: it could expand the set of places where geothermal is viable.

The company’s 2019 partnership with C3.ai fits the same pattern on the digital side. The BakerHughesC3.ai platform applies machine learning to industrial operations: optimizing production, predicting equipment failures, and supporting subsurface analysis, including work related to carbon storage. The core idea is that modern energy systems generate too much data for humans to consistently interpret in time. Algorithms can comb through thousands of variables—temperature, pressure, flow rates, equipment health—and surface patterns and optimization opportunities that would otherwise be missed.

Over time, that mindset changes what the company thinks it sells. Equipment becomes a data generator as much as a physical asset. Sensors embedded in machines, monitoring at customer sites, and the operational data flowing through Baker Hughes systems create an information layer that can improve performance. A drill bit isn’t only a cutting tool; it can also be a sensor platform, helping reveal what’s happening in the formation as it drills.

From an investor’s standpoint, the technology story has a few key takeaways. Baker Hughes is trying to hold leadership in legacy franchises—drill bits, cementing, turbomachinery—while building credibility in newer arenas like hydrogen, CCUS, geothermal, and emissions abatement. It’s investing in both hardware and software, because customers increasingly need systems, not components. And it uses partnerships to move faster in areas where it doesn’t want to start from scratch, while keeping core competencies in-house. That portfolio approach may feel less “pure” than a focused specialist, but it’s designed to create optionality in an energy transition that is anything but linear.

XI. Market Position & Competitive Dynamics

Baker Hughes sits in an unusual spot in the energy services world. It’s big enough to matter almost everywhere, diversified enough to play in multiple parts of the energy system, and still the underdog in the category it’s most associated with. That combination creates a tension investors need to understand: Baker Hughes has more ways to win than a pure oilfield services company, but fewer obvious places where it can simply outmuscle the competition.

In traditional oilfield services, Baker Hughes is still the smallest of the Big Three. SLB is the technology benchmark, with the deepest portfolio and the strongest research engine. Halliburton, meanwhile, is built for North American land—especially shale—where scale, speed, and pressure-pumping intensity can decide who takes share. Baker Hughes’s OFSE business is substantial, but it can’t out-SLB SLB on proprietary tech depth or out-Halliburton Halliburton on shale dominance.

So Baker Hughes doesn’t try.

Its play is differentiation. The company leans hard into its international footprint, where relationships, reliability, and integrated capability often matter more than being the lowest-cost provider on a short-cycle job. And it tries to turn what looks like an odd corporate structure—oilfield services plus industrial machinery—into a commercial advantage. If you’re developing an LNG project, for example, Baker Hughes can show up across the value chain: upstream services, compression equipment, and liquefaction turbines. That kind of bundled capability is difficult for a standalone oilfield services competitor to replicate.

The competitive map changes again in IET. Here Baker Hughes is up against industrial and power equipment heavyweights—Siemens Energy in turbomachinery, GE Vernova in parts of power generation, and large Asian manufacturers like Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Hitachi in specific categories. Many of these companies don’t have Baker Hughes’s oilfield-services muscle, but some go deeper in pure equipment manufacturing and have long histories with utilities and industrial buyers.

And in the energy transition categories—hydrogen, carbon capture, geothermal—the battlefield is still being drawn. Baker Hughes is competing not just with incumbents, but with specialists and startups that are often narrower, faster, and more focused. In hydrogen that can mean players like Nel, ITM Power, and Plug Power. In carbon capture it can mean firms like Aker Carbon Capture and Carbon Clean. In geothermal, Ormat has decades of operating experience that Baker Hughes is still working to accumulate.

Baker Hughes’s advantage in these newer markets isn’t that it invented every best-in-class component. It’s that it can integrate the whole system. A startup might have a great capture process; Baker Hughes can pair it with compression, transport know-how, injection infrastructure, and the field capability to run it. For big industrial customers—who often want fewer vendors, fewer interfaces, and one party accountable for performance—that “single throat to choke” can be a powerful value proposition.

Geography is another part of the moat. Baker Hughes operates in more than 120 countries, with real on-the-ground presence in the major energy regions. That matters with national oil companies and industrial customers that value local execution and long-term relationships. It also diversifies the cycle: a downturn in one region doesn’t hit the company as hard as it would a player concentrated in a narrower set of markets.

The market’s mixed view of all this shows up in the valuation. With a market cap around $37 billion, investors are crediting Baker Hughes for being more than an oilfield services company—but they’re also pricing in the reality that this strategy only works if the company executes, and if customers actually buy the integrated story.

That’s the core competitive question: does Baker Hughes’s breadth become a durable advantage, or does it become complexity that customers don’t want to pay for? If the market moves toward integrated, end-to-end solutions, Baker Hughes looks uniquely positioned. If customers keep preferring best-in-class point solutions—assembling their own stack of vendors—then Baker Hughes’s “fullstream” DNA risks turning into a structural handicap.

XII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

If you zoom out far enough, Baker Hughes reads less like a straight-line growth story and more like a survival manual. Over a century, it lived through brutal commodity cycles, stitched itself together through messy mergers, and then tried to reinvent itself right as the world started questioning the long-term future of its core industry. That arc leaves behind a set of lessons that travel well beyond oil and gas.

The Power of Crisis-Driven Transformation

Baker Hughes rarely changed when things were calm. It changed when it had to.

The 1987 merger was born out of the oil glut, when staying independent started to look less like pride and more like denial. The GE combination came out of the 2014–2016 collapse, when scale and differentiation suddenly mattered more than perfect timing. And the energy transition pivot accelerated as climate pressure and policy began reshaping what customers wanted to buy—and what investors were willing to fund.

The meta-lesson is simple: crises break inertia. They create the urgency that makes organizations do what they would never voluntarily do in good times. For investors, that means downturns aren’t just periods to measure damage; they’re stress tests of adaptability. Baker Hughes’s current shape is the cumulative result of repeatedly using the bad moments to force the next evolution.

Managing Complex Mergers

Baker Hughes has spent decades learning the hard skill most companies avoid: integration.

Since 1987, it has navigated the Baker-Hughes merger, the BJ Services acquisition, the attempted Halliburton merger, the GE combination, and then the GE separation. That repetition matters. The institutional capability to combine cultures, strip out duplication, keep critical talent, and avoid breaking customer delivery becomes a competitive advantage in industries that consolidate under pressure.

The Halliburton deal that didn’t happen is the best reminder that “strategically obvious” doesn’t mean “possible.” Regulators can kill the cleanest logic. But even that failure had an aftershock that mattered: the $3.5 billion breakup fee, which ended up giving Baker Hughes flexibility at exactly the moment it needed it—fuel for a different, more transformative move with GE than Halliburton likely would have been.

Portfolio Management in Cyclical Industries

From the outside, some of Baker Hughes’s portfolio moves—especially around BJ Services—look like indecision. Spin it off. Buy it back. Sell it again.

From the inside, it’s also a picture of what cyclical industries force you to do. What’s a competitive advantage in a boom can become a balance-sheet anchor in a bust. The “right” set of assets changes as the cycle changes, and companies that can adjust survive longer than companies that cling to a static identity. The trick is that you can be rational and still look inconsistent—because the environment is inconsistent.

Building New Capabilities While Maintaining Core Business

Baker Hughes is trying to build a lower-carbon growth engine while still relying on traditional oil and gas for the majority of its revenue and profits. That’s not a PR tension; it’s an operating tension.

Every dollar and every engineer pointed at hydrogen, geothermal, or CCUS is a dollar and an engineer not pointed at the next improvement in drilling tools, subsea systems, or production equipment. Pull too hard toward the future and you risk weakening the cash engine that funds the transition. Stay too focused on the core and you risk waking up late to a market that has moved on.

Managing that trade requires a leader—and a narrative—strong enough to justify long-term investment while still delivering quarter-by-quarter execution that shareholders will tolerate.

The Role of Visionary Leadership

Lorenzo Simonelli’s tenure shows how much a single CEO can matter when the strategy is genuinely hard.

His framing—that the energy transition is an opportunity set, not just a threat—pushed Baker Hughes toward offense rather than defense. And his GE background mattered in a practical way: he brought integration and industrial-operating discipline to a company that had spent decades as a field-driven oilfield services business. In stable markets, leadership differences can blur. In transformations, they don’t.

Capital Allocation in Cyclical Industries

Baker Hughes’s capital allocation reflects another balancing act: invest enough to stay technologically relevant, but return enough cash to keep investors engaged through the cycle.

The company continued funding R&D and growth initiatives—roughly $500–600 million annually—while also returning capital through dividends and buybacks. Its roughly 2.4% dividend yield signaled that management wanted to be owned not just as a turnaround or transition story, but as a credible shareholder-return story too. In a cyclical business, that mix—protect the future, reward the present—is often what keeps a strategy alive long enough to work.

XIII. Analysis: Bull vs. Bear Case

Evaluating Baker Hughes means holding two stories in your head at once—and being honest that both can be true. There’s a credible case that this is one of the best-positioned incumbents for an energy system in transition. There’s also a credible case that the transition will take longer, move unevenly, and leave Baker Hughes with most of its earnings still tied to a cyclical business facing long-term pressure.

The Bull Case

Baker Hughes’s bull case starts with something simple: no other oilfield services major looks quite like this. It’s the only one with a large oilfield services franchise and a meaningful industrial equipment business, plus a growing set of energy transition offerings. That structure doesn’t guarantee success—but it does create more paths to winning.

If the energy transition accelerates, the upside sits in IET. Hydrogen infrastructure, carbon capture projects, and geothermal development all demand the kinds of equipment and subsurface know-how Baker Hughes already has. And the company hasn’t treated these as purely theoretical markets. It has built testing capabilities, acquired technology, and formed partnerships that give it real shots on goal—optionality that pure-play oilfield services companies simply don’t have.

If, instead, oil and gas demand persists longer than many expect, OFSE remains a cash engine. A big portion of Baker Hughes’s oilfield business is international, where national oil companies and major producers continue to invest in maintaining and expanding production. Those budgets aren’t driven only by developed-market climate policy; they’re driven by energy security, economic development, and the reality that decline curves don’t care about press releases. Baker Hughes’s positioning outside North America lets it capture that long-cycle, stickier demand.

Then there’s the part of the story that doesn’t fit neatly into “oil” or “transition.” Baker Hughes’s industrial equipment—turbomachinery, compression, valves—serves broader industrial and power-adjacent markets. Data center power, distributed generation, and industrial processes all require equipment like this. And as AI pushes electricity demand higher, power generation equipment becomes relevant regardless of whether the grid is fed by gas, hydrogen blends, or something else. In that scenario, Baker Hughes benefits less from picking the “right” energy source and more from being in the flow of the buildout.

Supporters of the stock also point to the financial setup. A record IET backlog of $32.4 billion gives the company unusual visibility for a business historically tied to short-cycle oilfield activity. IET margin expansion suggests operational progress. And strong free cash flow—$2.7 billion in full year 2025—creates room to fund growth while still returning capital to shareholders.

Finally, there’s a compounding argument. If Baker Hughes becomes an early, credible execution partner for hydrogen, CCUS, or geothermal projects, it benefits from references, learning curves, and switching costs as systems move from pilot to scale. In heavy industry, “we’ve done it before” is a real moat.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a reality check: traditional oilfield services are still the majority of Baker Hughes’s revenue and profit. If oil demand declines over time the way many climate models suggest, the core business faces secular pressure even if management executes well. And in a shrinking market, cost structure and competitive intensity matter more—areas where competitors, including Halliburton, may prove more resilient.

The second challenge is that the transition businesses are still early and, in many cases, not yet proven at commercial scale. Hydrogen economics remain uncertain; green hydrogen, in particular, depends on cost declines and market structures that may take longer than expected. Carbon capture remains expensive relative to carbon prices in many jurisdictions. Geothermal is promising, but it has also had cycles of enthusiasm followed by disappointment.

Competition is another risk. In hydrogen, carbon capture, and geothermal, Baker Hughes isn’t just fighting incumbents—it’s fighting specialists. Pure-play companies can be narrower and faster, and they attract venture capital and strategic funding that can accelerate iteration. The same breadth that makes Baker Hughes compelling could become a handicap if the winning approach in a category comes from focus rather than integration.

Even the GE inheritance cuts both ways. Yes, Baker Hughes gained valuable industrial assets. But much of that equipment was built for a world where “energy” largely meant hydrocarbons. Adapting turbines for higher hydrogen blends or optimizing compressors for CO₂ transport and injection requires sustained R&D, and the returns aren’t guaranteed. In some categories, competitors building purpose-designed equipment could outperform retrofit-heavy approaches.

And then there’s execution. Baker Hughes is trying to run two demanding businesses while building a third set of growth lanes on top. That’s hard even in calm markets. In cyclical, capital-intensive markets, it can devolve into spreading management attention too thin—leading not to leadership, but to “good enough” everywhere.

Framework Analysis

Applying Porter's Five Forces to Baker Hughes:

Supplier Power: Moderate. Baker Hughes relies on specialized components and materials, and input costs can swing with commodity and electronics cycles. But scale and multiple sourcing options help.

Buyer Power: High in oilfield services, where customers are large, sophisticated, and price-sensitive. Lower in industrial equipment, where project integration and long-term service relationships can increase switching costs.

Threat of New Entrants: Low in traditional businesses because of technical complexity, capital intensity, and customer qualification hurdles. Higher in energy transition categories, where startups can enter with focused solutions.

Threat of Substitutes: Rising. Renewables and electrification substitute for some of the hydrocarbons Baker Hughes helps produce and process. Baker Hughes’s transition investments are partly a hedge against that substitution, but they’re not yet large enough to fully offset it.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense in oilfield services, especially among the Big Three. More concentrated in turbomachinery and industrial equipment. Still forming—but heating up—in energy transition markets.

Applying Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers framework:

Baker Hughes has Scale Economies in manufacturing and field operations. Switching Costs can be meaningful in installed equipment bases and digital platforms embedded in customer workflows. Process Power is real—built from decades of subsurface and industrial experience. Network Effects are limited, though they may grow as digital systems connect more assets and customers. Cornered Resources are modest; there’s no single monopoly-like asset. Branding matters in high-stakes projects where customers value supplier credibility. And Counter-Positioning shows up in the portfolio itself: Baker Hughes is placing energy transition bets that pure-play oilfield services companies may be structurally less willing to make.

Key Metrics to Watch

Investors tracking Baker Hughes should focus on two primary metrics:

IET Book-to-Bill Ratio: New orders relative to revenue. Above 1.0 means backlog is growing; below 1.0 suggests backlog is being worked down. It’s a forward indicator for the segment most tied to the transformation narrative.

International OFSE Revenue Share: The share of oilfield services revenue coming from outside North America. International markets tend to be longer-cycle and less commoditized than U.S. shale. Holding or growing that share is a practical signal that differentiation is working where pricing pressure is less brutal.

XIV. Epilogue & Future Outlook

The Baker Hughes story, at its core, is about adaptation. A company that started by keeping water out of oil wells now wants to help keep carbon out of the atmosphere. But whether that arc ends in reinvention or just reinvention talk depends on forces that don’t sit neatly inside a CEO’s control: how fast the energy transition actually moves, whether the economics of hydrogen, CCUS, and geothermal improve on a real-world schedule, and what customers and policymakers decide to subsidize, regulate, or demand.

Over the next decade, a few broad paths are plausible.

In an accelerated transition, hydrogen becomes cost-competitive in more use cases, carbon capture scales from “projects” into “industry,” and geothermal pushes beyond niche deployments. In that world, Baker Hughes’s early positioning starts to look less like optionality and more like inevitability. IET becomes the center of gravity, and the market begins valuing Baker Hughes less like an oilfield services company and more like a technology-and-equipment platform. The 2030 goal of getting to 50% of revenue from energy transition and industrial technology ends up looking conservative.

In an extended hydrocarbon scenario, oil and gas demand persists longer than many climate models assume. Developing economies keep building with the cheapest reliable energy they can access, and energy security remains the dominant political motivator. Here, OFSE keeps throwing off cash, while the transition portfolio grows—but at a pace that feels incremental rather than disruptive. Baker Hughes is still a strong business, just not a radically re-rated one.

Then there’s the fragmented outcome, which might be the most realistic. Different transition technologies work in different places, for different customers, at different times. Hydrogen succeeds in certain industrial processes but stays limited elsewhere. Carbon capture makes sense for some heavy industry applications but doesn’t become universal. Geothermal expands, but unevenly, based on local geology and project economics. In that world, Baker Hughes’s breadth becomes the advantage: it can show up where the transition is actually happening. The tradeoff is that it may participate widely without dominating any single lane.

Geopolitics will shape which path we get. National security concerns about energy dependence can drive investment in domestic production and infrastructure, which plays to Baker Hughes’s global footprint. Climate agreements and carbon pricing can make CCUS economically viable in ways that pure engineering can’t accomplish alone. Industrial policy in the U.S., Europe, and China will keep steering capital toward favored technologies—and, by extension, toward the companies best positioned to deliver them.

For investors, the cleanest way to frame Baker Hughes is as a call option on the energy transition, backed by a legacy business that still generates real cash. If the transition moves slowly or unevenly, the core oil-and-gas portfolio helps cushion the downside. If the transition accelerates and Baker Hughes proves it can execute at scale, the upside comes from a very different earnings mix—and potentially a very different market perception.

The company Reuben Baker and Howard Hughes Sr. built to solve drilling problems has already become something neither would recognize. What it becomes next—an energy technology leader, a durable but cyclical services provider, or some hybrid in between—will be decided not just in Houston, but in the capital budgets and policy choices made around the world. Either way, the transformation isn’t over.

XV. Recent News

Q4 2025 and Full Year 2025 Results (January 25, 2026)

Baker Hughes ended 2025 with what management called record performance—and this time it wasn’t just spin. Fourth-quarter revenue came in at $7.39 billion, ahead of analysts’ expectations of $7.07 billion. Adjusted earnings per share were $0.78, up 14% year over year. For the full year, the company posted record adjusted EBITDA of $4.83 billion and record free cash flow of $2.7 billion.

The clearest momentum was in IET. Full-year bookings hit $14.9 billion, above guidance, and Power Systems orders rose to $2.5 billion. A notable slice of that—about $1 billion—was tied to data center applications, a reminder that Baker Hughes’s industrial equipment franchise can ride demand drivers that have nothing to do with drilling rigs. By year-end, IET backlog stood at a record $32.4 billion, giving the company unusually strong forward visibility for a business with oilfield roots.

For 2026, management guided to mid-single-digit organic adjusted EBITDA growth. The message: IET is still working toward margin expansion toward its 20% target, while OFSE is expected to be relatively steady, reflecting stable global drilling activity.

Chart Industries Acquisition (Announced July 29, 2025)

In July 2025, Baker Hughes announced an agreement to acquire Chart Industries for $13.6 billion, or $210 per share in cash, representing a 22.34% premium to Chart’s pre-announcement price. Chart shareholders approved the deal on October 6, 2025. The acquisition was expected to close in mid-2026, pending regulatory approval.

Strategically, it’s a very on-theme move. Chart brings leading cryogenics and liquefaction technology—capabilities that sit right in the middle of hydrogen and LNG value chains. Baker Hughes pitched the deal as a way to accelerate its energy transition strategy by adding strength in hydrogen liquefaction, LNG processing, and specialty gas handling, while unlocking synergies by pairing Chart’s cryogenic systems with Baker Hughes’s compression and turbomachinery portfolio.

Major Contract Awards

The order book kept getting reinforced through 2025 and into early 2026. Baker Hughes won a major liquefaction equipment contract for Port Arthur LNG Phase 2 with Bechtel and Sempra Infrastructure. Petrobras awarded the company a contract for up to 50 subsea tree systems for offshore Brazil developments. Saudi Aramco expanded its integrated drilling operations contract, adding six underbalanced coiled tubing units.

And in the transition portfolio, one award stood out. In September 2025, Fervo Energy selected Baker Hughes for a geothermal contract covering five Organic Rankine Cycle power plants at Cape Station Phase II in Utah, targeted to generate 300 megawatts by 2028.

Strategic Divestiture

In January 2026, Baker Hughes completed the sale of its Precision, Sensors & Instrumentation product line to Crane Company for $1.15 billion. The rationale was simple: free up capital and redeploy it toward higher-return opportunities that fit the company’s priorities—especially the technologies it believes will matter most as energy systems evolve.

XVI. Links & Resources

Company Investor Relations - Baker Hughes annual reports and SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, 8-K) - Baker Hughes investor presentations and earnings call transcripts - Baker Hughes sustainability reports - Baker Hughes technology whitepapers

Industry Reports and Analysis - International Energy Agency: World Energy Outlook - DNV: Energy Transition Outlook - Schlumberger and Halliburton annual reports (for competitive context) - Deloitte and McKinsey oilfield services industry research