Bumble: From Heartbreak to IPO—The Whitney Wolfe Herd Story

I. Introduction: A Billionaire in Tears

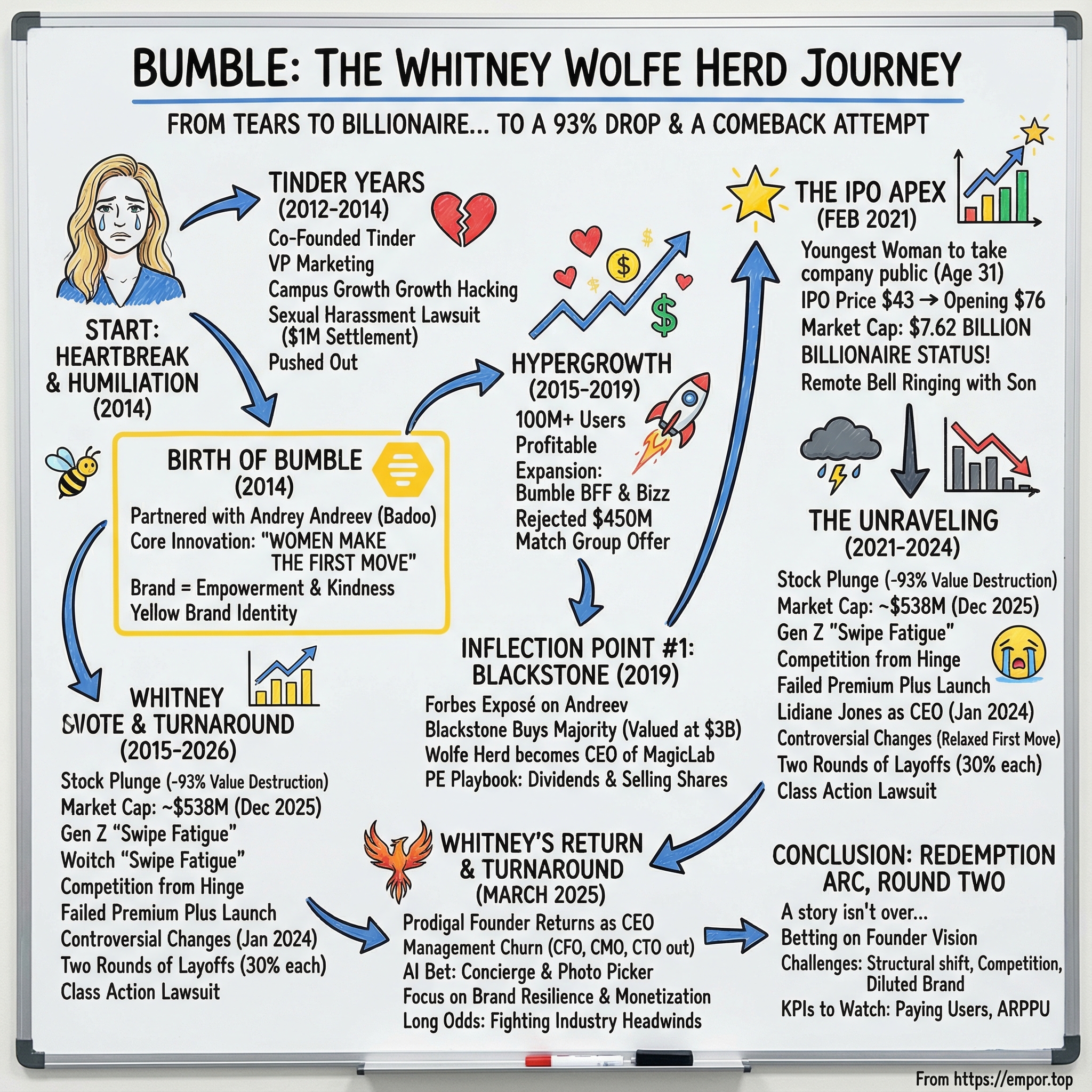

About four hours after she became the youngest woman ever to take a company public—and barely two hours after Bumble’s first-day surge made her a billionaire—Whitney Wolfe Herd sank onto a pink velvet couch in a canary-yellow office at Bumble’s Austin headquarters and fought back tears.

It was February 2021: the pandemic was still dictating the rules of life, and even the most symbolic moments in business were happening through screens. Wolfe Herd rang the Nasdaq bell remotely with her 18-month-old son on her hip. At 31, she became the youngest woman to lead an IPO in the United States—and, for a moment, the world’s youngest female billionaire.

And the market couldn’t get enough of it.

Bumble priced its IPO at $43 per share, above its expected range of $37 to $39, and sold 50 million shares. On day one, the stock ripped: it opened up nearly 77% at around $76 and closed the session up 63.5%. By the end of trading, Bumble sat at a market cap of $7.62 billion.

Investors weren’t just buying a dating app. They were buying a narrative: a founder who’d built one of the biggest platforms in modern dating out of the ashes of very public humiliation—and wrapped it all in a mission-driven brand that felt like feminism with a glossy, millennial sheen.

Even the mechanics of the offering became part of the legend. The $1.37 billion in foregone cash ranked as the eighth-largest of all time. Wall Street loved the story. The market loved the moment. Bumble had arrived.

Fast forward to December 2025, and the glow has faded into something much harsher. Despite occasional pops in the stock—shares rose 19% on recent news—Bumble’s value has cratered since its debut. The company’s market cap has fallen from $7.62 billion in 2021 to roughly $538 million as of Wednesday’s close: more than 93% of shareholder value erased. That kind of collapse makes even the post-pandemic tech wreckage look tame.

So what happened? How does a company with product-market fit, a powerful brand, and one of the most compelling founder arcs in Silicon Valley lose almost everything? And can Wolfe Herd—who returned as CEO in March 2025—pull off a comeback for the ages?

This is a story about founder redemption arcs (plural), the brutal economics of dating apps, brand as moat, private equity’s playbook in its most clinical form, and the existential challenge of sustaining network effects when your users’ ultimate goal is to delete you.

Oh—and it’s also a Hollywood story now. Swiped, a 2025 American biographical film starring Lily James as Wolfe Herd, with Dan Stevens, Myha’la, and Jackson White, directed by Rachel Lee Goldenberg and distributed by Hulu, turned Bumble’s origin into entertainment. Which is usually a sign you’ve either made it… or become a cautionary tale.

Maybe both.

II. Whitney Wolfe: Origin Story & Early Entrepreneurship

A Utah Girl With Bigger Dreams

Whitney Wolfe Herd didn’t come out of the usual Silicon Valley factory.

She was born Whitney Wolfe in Salt Lake City, Utah, to Kelly Wolfe and Michael Wolfe—raised between her father’s Jewish background and her mother’s Catholic one. She attended Judge Memorial Catholic High School, then headed to Southern Methodist University, where she studied international studies and joined Kappa Kappa Gamma.

No Stanford. No hoodie-and-hackathons mythology. No “I built the prototype in my dorm room.”

Wolfe Herd has been blunt about how un-credentialed her path looked on paper:

“I didn’t go to business school to take a formal job at a formal company, nor did I code a brand-new product in my dorm room…. I don’t come from the kind of background that would ever lead me, from a historical standpoint, to the career I’m in. Credentials don’t always define who someone is.”

And here’s the irony that makes the whole story feel pre-written: she wanted to go into marketing and advertising, but her university wouldn’t let her into that course—so international studies became the backup plan. The woman who’d later become one of the most influential marketers in consumer tech got rejected from learning marketing the traditional way.

The Do-Gooder Phase

What she did have early was an instinct for something most tech founders learn late—if they learn it at all: people don’t fall in love with features. They fall in love with stories.

While at SMU, Wolfe Herd partnered with celebrity stylist Patrick Aufdenkamp to start the “Help Us Project,” selling bamboo tote bags to support areas affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The effort pulled in celebrity attention—names like Rachel Zoe and Nicole Richie—an early signal that she understood how to package a mission, recruit tastemakers, and create momentum.

She and Aufdenkamp also launched a clothing line called “Tender Heart,” aimed at raising awareness about human trafficking and promoting fair trade practices.

After graduation, she traveled through Southeast Asia and volunteered at orphanages. Around that time, she started openly questioning the standard scoreboard of business. ROI and traditional measures of success, she said, felt “exceptionally dull.”

This wasn’t just idealism. It was the early blueprint of the Bumble playbook: values-forward branding, emotional resonance, and a knack for turning a mission into a movement.

The LA Dinner That Changed Everything

Then came the kind of turning point that sounds made up—until you realize how often real careers hinge on a single room, a single introduction, a single yes.

“I serendipitously ended up at a dinner in Los Angeles and met a couple of individuals who were working out of an incubator under the wings of Match.”

They were building something that would soon detonate across college campuses and rewrite the rules of dating for an entire generation. In 2012, it wasn’t yet called Tinder.

And Wolfe Herd—fresh out of school, with a cause-marketing background and a hunger to get into tech—felt the pull.

“When I completed my degree, I had no intention of building a dating app... I went to South East Asia, and whilst I was there, I had this a-ha moment! If you don’t have access to technology, you have nothing – that’s when I decided to go work in the tech space.”

She joined a prototype app called Matchbox inside Hatch Labs, an IAC-funded startup incubator. Her title: Vice President of Marketing.

Her impact: far bigger than the title suggested—and, soon enough, far more controversial than anyone at that dinner could’ve predicted.

III. The Tinder Years: Co-Founding the Dating Revolution (2012–2014)

Building Matchbox into Tinder

In 2012, Wolfe Herd was 22 and suddenly inside the blast radius of something new: a prototype called Matchbox being built at Hatch Labs, IAC’s startup incubator. She took the title Vice President of Marketing. But in a product like this—where growth is the product—marketing wasn’t a department. It was the engine.

Tinder didn’t become Tinder because of a clever ad campaign. It became Tinder because someone figured out how to kick-start a two-sided marketplace—fast. Wolfe Herd was there from the earliest days, and in her later lawsuit she would claim she played a pivotal role, including helping choose the name “Tinder” and focusing early growth on U.S. college campuses.

The “college strategy,” in hindsight, reads like a case study in marketplace ignition: don’t try to win everyone. Win one dense micro-network where social proof travels at the speed of gossip.

One retelling in connection with the film Swiped captures the vibe:

“Whitney brings this energy and passion to this pitch… and then gets herself in trouble and has to run around.”

That “trouble” was the hustle required to manufacture momentum. She’d pitch sororities first—often starting with her own Kappa Kappa Gamma network—then walk straight across campus to fraternities with the implied promise: the women are already on it. Classic chicken-and-egg solved with sequencing, social currency, and sheer force of personality.

It worked. Growth went vertical. By April 2014, Tinder was reported to have 10 million daily active users.

The Relationship, the Culture, the Collapse

But Tinder’s early rocket-ship phase had a dark gravity: a startup culture so young, so intense, and so blurred between work and life that professional lines didn’t just fade—they basically didn’t exist.

Wolfe Herd’s romantic relationship with Justin Mateen began in February 2013—while he was her direct supervisor. And when that relationship soured, her role at the company unraveled with it.

In what reads now like a #MeToo case before #MeToo had a name, Wolfe Herd filed a lawsuit on June 30 alleging sexual harassment and discrimination. She accused Mateen—Tinder’s co-founder and chief marketing officer—of sending “a barrage of horrendously sexist, racist, and otherwise inappropriate comments, emails and text messages.” She also alleged that Mateen and CEO Sean Rad stripped her of the “co-founder” title because of her gender.

That word—co-founder—became the fight. The lawsuit claimed the men wanted her minimized for optics. In court filings, Mateen was quoted saying:

“Facebook and Snapchat don’t have girl founders, it just makes it look like Tinder was some accident.”

And that, he allegedly argued, a “girl founder” devalued the company.

In September 2014, the case settled. Forbes reported Wolfe Herd netted “just over” $1 million. The settlement included stock and also barred her from speaking publicly about her experiences at Tinder. What she couldn’t be protected from was the aftermath: an online mob, a torrent of harassment, and the kind of public humiliation that makes most people disappear.

Some would’ve left tech entirely.

Wolfe Herd didn’t. She walked out of Tinder convinced she’d just seen the problem up close—and that she knew exactly what she wanted to build next.

IV. The Birth of Bumble: From Merci to “Women Make the First Move” (2014)

The First Draft: A Compliment Network, Not a Dating App

Right after the Tinder settlement, Wolfe Herd was wrecked—emotionally exhausted, professionally untethered, and trying to figure out what next even looked like.

Her first idea wasn’t another dating product. It was an antidote to what she’d just lived through: a women-only social network called Merci, built around something radically simple—compliments. Not the flirty, appearance-based kind, either.

“No compliments on physicality,” she told Forbes. “Compliments about who they are.”

In other words: build a platform where women could be seen and affirmed without being evaluated. She began sketching it out—features, flows, the tone of the community. Merci was supposed to be a new kind of social space entirely.

Then someone with a very different background—and a very different asset base—entered the picture.

Enter Andrey Andreev (and Badoo’s Machine)

Andrey Andreev, a Russian-born British entrepreneur, had already built a global dating giant: Badoo. In the U.S., Tinder was becoming the default. But in Europe and South America, Badoo had long been the frontrunner—one of the most downloaded dating apps in the world, with more than 400 million registered users.

Badoo had also been through multiple evolutions, including a stretch in the early 2010s as a social games and quiz app riding the Facebook Games wave. What it hadn’t been able to do was crack the United States in a meaningful way.

In 2014, Andreev reached out to Wolfe Herd after her exit from Tinder. He liked her original Merci vision—but he pushed her to apply it to the category he knew best. Not a compliments-only network.

A dating app. With the compliments network’s DNA.

Andreev didn’t just offer advice. He offered infrastructure. The partnership brought Wolfe Herd into his umbrella company, MagicLab (later renamed Bumble Inc.), and the deal they struck was unusual—and would shape Bumble’s governance for years.

Andreev retained 79% ownership in exchange for a $10 million investment, plus additional funding, consulting services, and access to Badoo’s existing tech. Wolfe Herd became CEO and received a 20% ownership stake.

The tradeoff was stark: Whitney didn’t truly control her own company at the beginning. But she gained what most first-time founders can only dream about—capital, a proven growth machine, and Badoo’s London engineering team to power the product from day one.

Austin, a Naming Problem, and One Rule That Changed Everything

There was also a practical reset. Wolfe Herd planned to call the app Moxie, but the name was already taken. So she moved on—and moved out. In December 2014, she relocated to Austin, Texas, and brought former Tinder colleagues with her to build what would soon become Bumble.

She later described the partnership with Andreev in almost perfectly complementary terms:

“At Tinder, I’d been a big part of engineering network effect and I knew how to do it, and understood how to speak to a consumer and build an authentic brand – that said, I had the perfect partner, because Andrey brought everything to the table that I didn’t have; a robust infrastructure, 12 years of user data points, and the incredible technology he had spent so many years building.”

And then came the defining product decision—the one that turned Bumble from “Tinder, but yellow” into something with an identity.

Wolfe Herd framed it as a cultural mismatch she couldn’t unsee:

“When I founded Bumble, it was because I saw a problem I wanted to help solve. It was 2014, but so many of the smart, wonderful women in my life were still waiting around for men to ask them out, to take their numbers, or to start up a conversation on a dating app. For all the advances women had been making in workplaces and corridors of power, the gender dynamics of dating and romance still seemed so outdated. I thought, what if I could flip that on its head? What if women made the first move?”

Bumble launched in

V. Scaling the Yellow Brand: Hypergrowth (2015–2019)

Early Traction—and the Quiet Superpower of Brand

Bumble launched in December 2014. A year later, it already looked less like an experiment and more like a category force.

By December 2015, Bumble had racked up more than 15 million conversations and 80 million matches—absurd numbers for a one-year-old dating app.

And yes, the headline mechanic mattered: women message first in heterosexual matches, which dramatically reduced the volume of unsolicited garbage that had become synonymous with online dating. But Bumble’s real differentiator wasn’t just a rule. It was the way the company packaged that rule into an identity people wanted to wear.

Wolfe Herd didn’t talk about Bumble like it was a product. She talked about it like it was a brand—the word she returned to over and over. Alex Williamson—her sorority sister, best friend, and Bumble’s former chief brand officer—put it plainly: “Whitney was a big believer that branding is everything.”

The positioning was calibrated and confident. Bumble planted itself inside what critics dubbed the “Empowerment Industrial Complex”—more youthful than Lean In, less combative than Time’s Up. It wasn’t a movement built on outrage; it was a friendly, upbeat, Sadie Hawkins-style feminism built on vibes: confidence, optimism, self-respect. The bold yellow palette made it instantly recognizable. The messaging was relentlessly positive.

It worked so well that Bumble’s branding became something you’d see dissected in marketing and MBA classrooms. In an industry where features copy fast, brand doesn’t. Tinder may have had more users—but Bumble had a cleaner story, and a clearer place in the cultural imagination. That clarity became a moat.

Platform Expansion: BFF and Bizz

Once Bumble proved it could win in dating, Wolfe Herd started asking a bigger question: what if Bumble wasn’t just for romance?

The company expanded beyond dating with Bumble BFF (for platonic friendship) and Bumble Bizz (for professional networking). This wasn’t random feature sprawl—it was a strategic bet that Bumble’s core promise and tone could travel. If “women make the first move” could reset the dynamics of dating, maybe it could also reshape how people find friends in a new city, or build a career network without the usual creep factor.

Safety wasn’t just a policy choice—it was part of the product’s identity. Zero Tolerance for Harassment became a core pillar, backed by stricter rules designed to keep the community respectful. Wolfe Herd also pushed beyond the app itself, advocating for tougher legal consequences online and championing the passage of Texas House Bill 2789, which made sending unsolicited explicit images a punishable offense.

The Numbers Tell the Story

By 2020, Bumble had crossed a milestone that signals true global scale: more than 100 million users worldwide. In roughly six years, it went from zero to nine figures in users—and it did it while remaining profitable, which is almost unheard of in the venture-fueled startup playbook.

Wolfe Herd’s profile rose alongside the company’s. She was named to Forbes 30 Under 30 in 2017 and 2018—a founder-celebrity now building a founder-company with real momentum.

And the old world came knocking. Match Group, Tinder’s parent company, reportedly offered to buy Bumble for $450 million, and possibly as much as $1 billion or more. Bumble said no. Wolfe Herd and Badoo believed the company was worth far more—and, more importantly, they believed it was still early.

VI. Inflection Point #1: The Blackstone Acquisition (2019)

The Forbes Exposé—and Andreev’s Exit

By 2019, the road map looked almost too clean: keep growing, keep printing cash, and take Bumble public as the feel-good counterweight to the rest of dating-app hell.

Then Forbes dropped an exposé that threatened to turn Bumble’s origin story into a punchline.

The allegations centered on Badoo’s headquarters in London—Andrey Andreev’s operation—and described a sexist, toxic culture that clashed violently with everything Bumble marketed itself to be. The irony wasn’t subtle: the company built on the premise of protecting women from harassment was still majority-owned by a man whose organization was accused of enabling the very behavior Bumble claimed to be fighting.

Wolfe Herd’s response whiplashed in real time. She initially defended Andreev, telling Forbes, “He’s become my family and one of my best friends.” But one day after the article ran, she issued a new statement: she was “saddened and sickened to hear that anyone, of any gender, would ever be made to feel marginalized or mistreated in any capacity at their workplace.”

And suddenly, the IPO narrative wasn’t “mission-driven tech company goes public.” It was: Can you take this to Wall Street with this cap table—and this baggage?

The Blackstone Solution

Enter Blackstone.

The private equity giant announced it would buy a majority stake in MagicLab—the parent company of Bumble and Badoo—in a deal valuing the business at $3 billion. Andreev would sell his stake and step down.

For Bumble, it was an elegant corporate reset: new majority owner, old majority owner gone, and a cleaner story for public markets.

For Wolfe Herd, it was also a power shift. She held roughly a 19% stake, and as part of the transaction she was named CEO of MagicLab, overseeing both Bumble and Badoo. Andreev relinquished his shares of both companies, and Wolfe Herd became the face—and operator—of the entire portfolio.

But this is where the private equity playbook starts to show through. MagicLab wasn’t some cash-burning science project. It was profitable, and growing fast—reportedly 40% annually at the revenue line. That’s exactly the kind of machine PE loves: steady cash flows, clear levers, and the option to refinance or extract value.

And Blackstone did what Blackstone does. It pulled out a $300 million special dividend from the company.

Then came the bigger payday: the public markets. During Bumble’s IPO in February 2021, Blackstone sold a chunk of its position for $2 billion, leaving it with 98.23 million shares. In September 2021, in a secondary offering, it sold another 20.7 million shares for about $1 billion—bringing Blackstone’s total haul to roughly $3.3 billion from share sales and dividends.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The IPO (February 2021)

Going Public During a Pandemic

On paper, February 2021 looked like the worst possible moment to take a dating company public. The pandemic had made “meeting strangers” feel like a health policy debate, not a Friday night plan. Bars were closed. Offices were empty. Even seeing friends came with caveats.

And yet, the exact thing that made offline dating harder made online dating more central. Dating apps were one of the few places where you could still meet someone new without leaving your couch—and that virtual layer didn’t just sustain demand; it arguably intensified it.

Bumble filed to go public in mid-January. On February 2, it floated an initial price range of $28 to $30 per share. The market shrugged. So Bumble raised the range to $37 to $39 earlier that week—then, on February 10, priced above even that.

Per the company’s IPO announcement, Bumble priced 50,000,000 shares of Class A common stock at $43.00 per share, with an additional 30-day underwriters’ option for up to 7,500,000 more shares. The stock was set to trade the next day on the Nasdaq Global Select Market under the symbol BMBL.

In total, before counting the underwriters’ option, Bumble raised $2.15 billion by selling those 50 million shares.

The First-Day Pop and the Historic Moment

The next day, Wall Street did what it often does when a clean story meets a hot market: it bid the thing into the stratosphere.

Bumble opened around $76, surged more than 80% in the first minutes of trading, and closed at $70.31—up roughly 63% from the $43 IPO price.

For Wolfe Herd, it was also a milestone that became part of the company’s brand mythology. At 31, she was the youngest female CEO to take a large U.S. company public. And she leaned into what investors were really buying: not “another dating app,” but a broader consumer internet platform with an identity.

As she told Yahoo Finance Live, the reception reflected Bumble’s ambition to stretch beyond romance:

“The world has recognized the power of online dating, and the world is about to recognize the power of finding community and connections around whatever you’re looking for on the internet. We have been meticulous about building a brand that protects women and engineers accountability and kindness into the internet.”

The Financials at IPO

Under the hood, Bumble’s S-1 showed a business with real scale—and the messy accounting reality of going public.

In the first nine months of 2020, Bumble generated $376.6 million in revenue and posted a net loss of $84.1 million. In the same period in 2019, it brought in $362.6 million and reported a net profit of $68.6 million. The swing from profit to loss was attributed to IPO-related expenses and investments in growth.

With more than 40 million active users worldwide, Bumble had proved something important to the public markets: Match Group didn’t have a monopoly on investable dating. For years, Match was treated as the only “public dating company” that could exist at scale. Bumble’s debut was the counterargument—in bright yellow, with a mission statement attached.

VIII. The Unraveling: From Billionaire to Struggling (2021–2024)

The Post-IPO Reality

The IPO was the apex. What came next was a long slide that ultimately wiped out more than 90% of Bumble’s market value. To understand the unraveling, you have to hold two truths at once: dating apps are structurally hard businesses, and Bumble also made some very specific, very painful execution calls.

Start with the competitive picture. Bumble is still Tinder’s closest rival—but over time it lost relative momentum. Over the past year, that showed up in the places that matter: market share, investor confidence, and a stock chart that kept making new lows.

Underneath that, the problems stacked up from multiple angles:

The Core Business Challenge: Dating is a consumer internet category with a built-in contradiction: your happiest users are the ones who churn. When Bumble works, couples form—and then they leave. Bumble acknowledged this dynamic in its prospectus, arguing that online dating “is not a ‘winner-take-all’ market,” and noting that most people keep about two dating apps on their phones. True—but “not winner-take-all” doesn’t mean “easy.” It means you’re constantly fighting for attention, habit, and wallet share in a market where switching costs are basically zero.

Gen Z Swipe Fatigue: By the early 2020s, the vibes shifted. A 2024 Forbes Health survey found that 79% of Gen Z users reported some degree of fatigue with dating apps like Hinge, Tinder, and Bumble—tons of time spent, too few real connections made.

As dating coach Rae Weiss put it to Newsweek: “Gen Z is moving away from dating apps because swiping often feels transactional, laborious and scripted.”

And the data suggested Gen Z wasn’t just complaining—they were participating less. A 2023 Statista survey found that in the U.S., users ages 30–49 (mostly millennials) made up 61% of dating app users, while Gen Z accounted for only 26%. For a category that’s supposed to renew itself with each new cohort, that’s not a warning light. That’s the dashboard going dark.

Competition from Hinge: Meanwhile, Hinge was doing something that looked almost boring—but worked: it leaned into intentionality. Gen Z made up 56% of Hinge’s user base, and the app reported a 17% increase in paying users. Strong prompts and a product designed to create better conversations helped Hinge feel less like an endless slot machine and more like actual dating.

The Premium Plus Failure: Bumble also stumbled on monetization. In December 2022, the company launched a Premium Plus subscription tier that management later admitted “did not have a clear enough market fit at launch.” The moment the market really absorbed that reality was February 27, 2024, when Bumble reported disappointing Q4 2023 results. On the earnings call, management said Premium Plus would be revamped as part of a broader Bumble app relaunch—because the tier simply wasn’t landing.

The CEO Transition

Then, the founder stepped back.

Whitney Wolfe Herd announced she would step down as CEO and be succeeded by Lidiane Jones (then the CEO of Salesforce’s cloud-based messaging platform Slack) on January 2, 2024. When the news hit, Bumble shares closed down more than 4% that day and were down 38% year-to-date.

Wolfe Herd framed it as a deliberate, considered handoff:

“It’s a monumental moment, one that has taken a great deal of time, consideration and care, for me to pass the baton to a leader and a woman I deeply respect.”

She moved into the role of executive chair as Jones took over.

Jones didn’t inherit an easy job—and she didn’t tiptoe around it. In her short tenure, she pushed through an overhaul that changed how conversations start on Bumble, a meaningful shift for an app built on one defining premise: women make the opening move.

The overhaul didn’t land the way Bumble needed it to. The stock fell further in August after quarterly revenue and Q3 2024 guidance came in below estimates, and shares ended 2024 down roughly 54% from the time Bumble began allowing men to message first.

Strategically, it was controversial for a simple reason: it blurred Bumble’s sharpest edge. The “women make the first move” mechanic wasn’t just a feature—it was the brand. Diluting it felt less like iteration and more like giving up the one thing competitors couldn’t easily copy.

The Layoffs

Cost cuts followed.

In February 2024, Bumble announced plans to lay off about 350 employees—roughly 30% of its workforce—as part of a restructuring. The company said the goal was to centralize engineering and product teams into fewer locations, accelerate decision-making, and prioritize investments in artificial intelligence and safety features. Jones communicated that plan on a call with analysts.

Then came another blow. More than a year later, Bumble disclosed another major reduction: about 240 employees would be let go—again, about 30% of the workforce—according to an SEC filing. The company said the aim was to realign its operating structure and “optimize execution” against strategic priorities.

Two 30% cuts within roughly 18 months isn’t a tidy restructure. It’s triage.

The Securities Litigation

And then came the lawsuits.

Rosen Law Firm announced the filing of a class action on behalf of investors who purchased Bumble securities between November 7, 2023 and August 7, 2024 (the “Class Period”). The release noted that a class action had already been filed and that any motion to serve as lead plaintiff was due by November 25, 2024.

The complaint alleges that on August 7, 2024, Bumble reported mixed Q2 2024 results and disclosed that the app relaunch wasn’t going to plan. Bumble said it would need to “reset” its outlook and “rebalance Bumble subscription tiers,” including pausing the revamp of the poorly received Premium Plus tier. The suit also alleges Bumble cut full-year guidance for a second time. On that news, Bumble’s stock price fell more than 29%, according to the filing.

IX. Whitney’s Return—and the 2024–2025 Turnaround Attempt

The Prodigal Founder Comes Back

By early 2025, Bumble had started to feel like a company in motion without a driver.

Lidiane Jones—the outside CEO hired in early 2024—was out after roughly a year. Bumble announced that Jones would resign for “personal reasons” and officially depart in March. Founder and executive chair Whitney Wolfe Herd would step back into the CEO role in mid-March 2025.

In the company’s statement, Wolfe Herd credited Jones for steadying the business through a turbulent stretch: “I am deeply grateful for the transformative work Lidiane has led during such a pivotal time for Bumble, and her leadership has been instrumental in building a strong foundation for our future.”

But the subtext was hard to miss. During Jones’s brief tenure, Bumble pushed through an overhaul that changed how conversations begin—touching the most sacred mechanic in the product: the app was built on the premise that women make the opening move. The change was controversial, and the results didn’t give Bumble much cover.

And the CEO change wasn’t happening in isolation. Bumble was also staring down senior leadership churn: CFO Anu Subramanian and CMO Selby Drummond had already announced plans to leave in early 2025. According to Bumble’s latest annual report, the company had cut about 30% of employees in 2024, and in 2025 it lost multiple executives, including its chief financial officer, chief business officer, and chief technology officer.

Meanwhile, Bumble began unwinding bets it had made to stay relevant with younger users. It shut down Fruitz, the Gen Z-focused dating app it acquired in 2022, and Official, an app it acquired in 2023.

The stock chart captured the mood. Bumble went public in 2021 with shares trading around $75 at the highs. By March 2025, the stock had fallen below $5 per share—an all-time low.

So Wolfe Herd’s return wasn’t just a founder victory lap. It was an emergency recall.

The Financial Picture Now

Even as the company’s story unraveled, the top line didn’t collapse overnight.

For full-year 2024, Bumble reported:

- Revenue up 1.9% to $1,071.6 million (including an unfavorable $7.3 million impact from foreign currency moves year over year)

- Bumble App revenue up 2.5% to $866.3 million (including an unfavorable $5.6 million FX impact)

- Badoo App and Other revenue down 0.8% to $205.4 million

Usage and monetization told a more mixed story:

- Total Paying Users up 11.5% to 4.1 million (from 3.7 million)

- Total ARPPU down to $21.23 (from $23.03)

Profitability, though, is where you see the damage:

- Operating loss of $700.5 million, or (65.4)% of revenue—driven by $892.2 million of non-cash impairment charges

- Adjusted EBITDA of $304.1 million, or 28.4% of revenue (up from $275.6 million, or 26.2%)

That $892.2 million impairment charge is the tell. A write-down that large is management acknowledging that assets it bought—and the goodwill it carried on the books—aren’t going to produce the future cash flows once assumed. It’s less “temporary turbulence” and more “we overestimated what these moves would become.”

As of December 31, 2024, Bumble reported $204.3 million in cash and cash equivalents and $617.1 million of total debt.

The pressure continued into 2025. Bumble reported a difficult Q2 2025, with total revenue down 7.6% to $248.2 million. The Bumble App declined 7.6% to $201.4 million, and Badoo App revenue fell 7.5% to $46.8 million.

The AI Bet

Against that backdrop, Bumble started leaning hard into a new pitch: AI as the antidote to modern dating burnout.

The company increased investment in AI and teased a slate of features designed to reduce friction—especially for newer, younger users who increasingly describe dating apps as exhausting. At Goldman Sachs’ annual technology conference, Jones laid out upcoming AI capabilities including a photo selection tool, plus AI help with profile creation and conversation support. She framed it as confidence-building infrastructure:

“We will also introduce new AI-driven features, including an AI-assisted photo picker to ease the profile creation process and conversation support that will help our customers gain confidence to be their best selves. We have an ambitious view of how AI will enhance the value we deliver to our customers in each step of the dating journey.”

Wolfe Herd went even further at the Bloomberg Technology Summit in San Francisco, arguing AI could compress the entire funnel—less swiping, fewer dead-end chats, more real-world matches. In a speculative aside to host Emily Chang, she painted a world where your “AI dating concierge” could do the sorting for you:

“If you want to get really out there, there is a world where your [AI] dating concierge could go and date for you with other dating concierge. Truly. And then you don’t have to talk to 600 people. It will scan all of San Fransisco for you and say: ‘These are the three people you really outta meet.’”

Whether that’s the future of romance or a dystopian nightmare is an open question. What isn’t: Bumble is betting that AI can blunt “swipe fatigue,” make the experience feel less laborious, and pull the product back into relevance—especially with younger users who are increasingly opting out.

X. The Hollywood Chapter: Swiped and the Biopic Treatment

Art Imitates Business

At a certain point, a startup story stops being a startup story and becomes IP.

In 2025, Wolfe Herd’s arc officially made that leap. Swiped—a biographical film distributed by Hulu and starring Lily James as a fictionalized “Whitney Wolfe”—packages the Bumble origin as modern myth: a recent college graduate fights her way into a male-dominated tech world, survives sexism and industry resistance, and then builds a dating app that rewrites the rules of connection. In the movie’s telling, she doesn’t just launch Bumble—she launches “two, actually”—and winds up the youngest female self-made billionaire.

It’s a clean, cinematic version of a story that, in real life, was messier and far more costly.

What’s most striking isn’t that Hollywood showed up. It’s that Wolfe Herd didn’t.

She told CNBC she still hasn’t watched the full film and isn’t involved with it. In fact, she said that two years earlier her first instinct was to try to stop it: she asked her lawyer to “shut it down.” By the time she learned it was happening, it was already moving fast.

“So, I can’t make it through the whole trailer; it’s too weird for me,” she said. “No, I’m not involved in it. Frankly, I was informed about this movie after it was already off to the races. I think they had already written the script and done all these things.”

The film’s closing credits make the separation explicit: “Whitney Wolfe Herd did not participate in the making of this film. She remains under a non-disclosure agreement.”

That last line is the quiet gut punch. Even as her story gets turned into entertainment, Wolfe Herd is still constrained by the NDA from her Tinder settlement—still living with a legal boundary around what she can publicly say about the event that set this entire second act in motion. The biopic may feel like a victory lap. But the fine print is a reminder: for all the reinvention, the origin trauma never fully disappears.

XI. Industry Landscape: The Dating App Wars

The Competitive Battlefield

Dating apps aren’t a niche anymore—they’re infrastructure. Today, more than 364 million people worldwide use them, and the category generated $6.18 billion in revenue in 2024.

But the industry isn’t evenly distributed. One company towers over the rest: Match Group. With marquee brands like Tinder and Hinge (plus a long tail of other apps), Match generated $3.5 billion—more than half the entire market’s revenue.

Here’s how the leaderboard shakes out:

- Tinder (Match Group): The undisputed heavyweight, with 31.4% market share and $1.94 billion in 2024 revenue.

- Bumble (Bumble Inc.): The clear #2, defined by “women make the first move,” with 14.0% market share.

- Hinge (Match Group): The fast-growing challenger in “serious dating,” reaching $550 million in 2024 earnings and an 8.9% market share.

- Grindr (public company): The category leader for LGBTQ+ dating, with 5.6% market share and $345 million in revenue.

This is not a pure winner-take-all market—most people keep multiple apps on their phones—but it is a market where network effects matter inside specific lanes. Tinder dominates casual dating. Hinge has momentum in relationships. Bumble has historically lived somewhere in the middle: less hookup-forward than Tinder, less “delete the app” earnest than Hinge.

And that middle is a tough place to defend.

The Gen Z Problem

Now add the bigger shift: the next generation is getting tired of the whole format.

A Forbes Health survey found 79% of Gen Z reported “dating app burnout.” And it shows up in behavior, not just vibes. According to mobile analytics firm AppsFlyer, 65% of dating apps downloaded in 2024 were deleted within a month. This year, that figure climbed to 69%, AppsFlyer told Fast Company.

Gen Z’s preference is increasingly explicit: meet people offline. A nationwide survey from the Kinsey Institute and DatingAdvice.com found that 90.24% of Gen Z respondents would rather meet through real-world settings—social gatherings, bookstores, classes, clubs—than through an app.

That’s an existential threat to the entire industry. But for Bumble—whose cultural sweet spot has long been millennial women—the generational shift hits especially hard. If the market’s growth engine is cooling, then the game stops being “who wins the next cohort?” and starts being “who can keep anyone from leaving at all?”

XII. Bull and Bear Cases: Investment Analysis

After all the narrative—mission, marketing genius, private equity engineering, pandemic timing, and a founder boomerang—the question becomes unglamorous and unavoidable: what kind of business is Bumble now?

One useful way to answer that is to run Bumble through two classic strategy lenses: Porter’s Five Forces (how tough is the battlefield?) and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers (what, if anything, is durable about Bumble’s advantage?). Then we’ll lay out the bull and bear cases—and the only two metrics that really matter if you’re watching for a turnaround.

Porter’s Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants (MODERATE–HIGH): Building the app is easy; building the marketplace isn’t. Network effects and brand take time. Still, newcomers can break in by going niche. Feeld is a good example of a differentiated entrant finding its lane. The Czech company FlintCast has also gained traction with a portfolio approach—apps like Evermatch, SweetMeet, Maybe You, and iHappy—showing that new supply keeps coming.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (LOW): Bumble’s “suppliers” are mostly the mobile platforms—Apple and Google—who take a 15–30% cut of in-app purchases. It’s a real tax on the business, but it’s not a Bumble-specific disadvantage; everyone pays it.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (HIGH): Users have all the leverage because switching costs are basically zero. Most people keep multiple dating apps installed and reallocate attention instantly based on vibes, novelty, perceived match quality, or whatever their friends are using this month.

Threat of Substitutes (HIGH): This is the big one. Bumble isn’t just competing against Tinder and Hinge—it’s competing against everything else people use to meet people: Instagram and TikTok, DMs, in-person social scenes, matchmaking, and the growing cultural push toward “touching grass” and meeting offline. For many Gen Z users, commenting and DM’ing feels more natural than swiping.

Competitive Rivalry (HIGH): The space is a knife fight. Match Group’s portfolio is the gravitational force, independent scale players like Grindr defend strong niches, and new apps constantly try to siphon off specific communities. Attention is scarce, and the product experience is easy to replicate.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Framework

1. Scale Economies: Limited. Bumble can get some efficiency from scale, but dating apps don’t get the kind of runaway unit-cost advantages that define true scale-economy businesses.

2. Network Effects: Real, but messy. Dating apps have same-side network effects (social proof) and cross-side effects (you need the other side to show up). But those network effects are local—not global—and the best-case outcome (matching and leaving) actively erodes the network over time.

3. Counter-Positioning: This used to be a core advantage. “Women make the first move” was a differentiated stance that Tinder couldn’t easily copy without breaking its own brand. But Bumble’s decision under Jones to relax that mechanic weakened this power—because you don’t get credit for differentiation you no longer enforce.

4. Switching Costs: Almost nonexistent. People multi-home across apps with zero penalty and little lock-in.

5. Brand: Still the strongest “power” Bumble has. The yellow identity, the empowerment positioning, and Wolfe Herd’s founder story create real differentiation. But brand is a living asset: it depreciates without continuous investment and clarity.

6. Cornered Resource: None obvious. Bumble doesn’t appear to control exclusive technology, uniquely scarce talent, or proprietary data others can’t replicate.

7. Process Power: Not evident. There’s no clear sign Bumble has internal operating processes that reliably compound into advantage.

The Bull Case

-

Founder Return: Wolfe Herd has already built Bumble from nothing once. Her return restores the high-conviction, brand-first leadership that originally made the company feel inevitable.

-

Brand Resilience: The stock has been crushed, but the brand remains widely recognized. Even with the mechanic loosened, Bumble still occupies a distinct identity in the category.

-

AI Upside: If AI meaningfully reduces “swipe fatigue”—better profiles, better conversations, better matching—Bumble could improve retention and monetization by making the product feel less like work.

-

Valuation Reset: At current levels, Bumble trades at roughly 0.5x trailing revenue—cheap if the business stabilizes and the turnaround shows evidence of working.

-

Restructuring Is (Mostly) Done: Two rounds of layoffs suggest the cost base is now sized for a leaner company, potentially giving margins room to expand if revenue stops sliding.

The Bear Case

-

Structural Industry Headwinds: Swipe fatigue isn’t a Bumble problem—it’s a dating-app problem. If culture keeps shifting toward offline meeting, no feature bundle will save the category.

-

Hinge Is Winning the “Intentional Dating” Lane: Match Group’s Hinge is growing with the demographic Bumble historically leaned on, and it’s positioned precisely where Bumble wants to be: serious-but-not-stuffy.

-

Brand Dilution Is Hard to Undo: Letting men message first didn’t just tweak onboarding—it blurred Bumble’s signature. Rebuilding a brand edge is far harder than protecting one.

-

Management Churn: Two CEOs in 18 months, two 30% workforce cuts, and senior departures (CFO, CMO, CBO, CTO) creates instability—exactly when execution discipline matters most.

-

Litigation Overhang: Securities class action litigation brings both direct financial risk and a persistent distraction for leadership.

-

PE Exit Gravity: Blackstone has been steadily selling shares—down from roughly 98 million at IPO to 50+ million by 2024. When the biggest holder is a consistent seller, it can create ongoing pressure on the stock.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you’re tracking Bumble’s turnaround, a lot of metrics are noise. Two are signal:

1. Bumble App Paying Users: This is the clearest read on whether product changes are working. The absolute number—and, more importantly, the quarter-over-quarter trend—tells you if Bumble is regaining momentum. Currently around 2.5–2.8 million paying users for the Bumble app specifically, this needs to meaningfully inflect upward for any durable recovery.

2. Average Revenue Per Paying User (ARPPU): This is monetization quality. ARPPU fell to $21.23 from $23.03, signaling pricing pressure and/or a mix shift toward lower tiers. Stabilization—or a sustained move back up—would suggest users are seeing enough incremental value to pay more, not just showing up.

XIII. Conclusion: Redemption Arc, Round Two

Whitney Wolfe Herd is now attempting something very few founders ever face—let alone survive: a second redemption arc, in the same category, in full public view.

The first one is already business folklore. After leaving Tinder under a cloud of humiliation and harassment, she turned the experience into a thesis: online dating didn’t have to feel like the internet at its worst. Bumble wasn’t just a product response—it was a cultural rebuttal. And it worked. A woman allegedly told she couldn’t be a “co-founder” because she was a woman went on to lead a company to the public markets at a $7.62 billion market cap.

This second arc is different—and harder.

She isn’t building a new brand from scratch. She’s trying to restore sharpness to one that’s been blurred. She isn’t exploiting a clean competitive opening. She’s fighting a category-wide shift: Gen Z swipe fatigue, falling tolerance for transactional matching, and a broader push toward meeting offline. And she’s doing it with the constraints of a mature public company—activist investors, quarterly expectations, a bruised workforce, and a balance sheet with meaningful debt and shrinking cash.

The odds are long. Dating apps may be structurally tougher businesses than investors wanted to believe in 2021. Bumble’s differentiation narrowed the moment it loosened the “women make the first move” mechanic. And the company’s financial posture—debt on the books, impairment write-downs, and declining revenue—doesn’t give leadership infinite time to experiment.

But one lesson from this story keeps repeating: counting out Whitney Wolfe Herd has historically been expensive. She’s been dismissed before, written off before, and underestimated before—only to come back with a bigger outcome than anyone expected.

Now she’s back again. Not to reinvent online dating, but to prove Bumble can still matter in a world that’s increasingly tired of the entire format.

The story isn’t over.

It’s just entering its second act.

Material Legal and Regulatory Overhangs:

- Securities class action lawsuit covering the period November 7, 2023 through August 7, 2024, alleging misleading statements related to the Premium Plus subscription tier and the app relaunch strategy

- Illinois biometric privacy settlement (Howell v. Bumble) involving the use of facial recognition / photo verification technology

- Ongoing regulatory scrutiny in EU markets around data privacy and app store commission structures

Accounting Considerations:

- The $892.2 million impairment charge in 2024 suggests substantial write-downs tied to prior acquisitions (including Fruitz and Official, and potentially other goodwill)

- Bumble reports both GAAP losses and Adjusted EBITDA; the gap between them (a $700.5 million operating loss versus $304.1 million Adjusted EBITDA) reflects significant non-cash items, including impairment and stock-based compensation

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music