Citigroup: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Financial Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

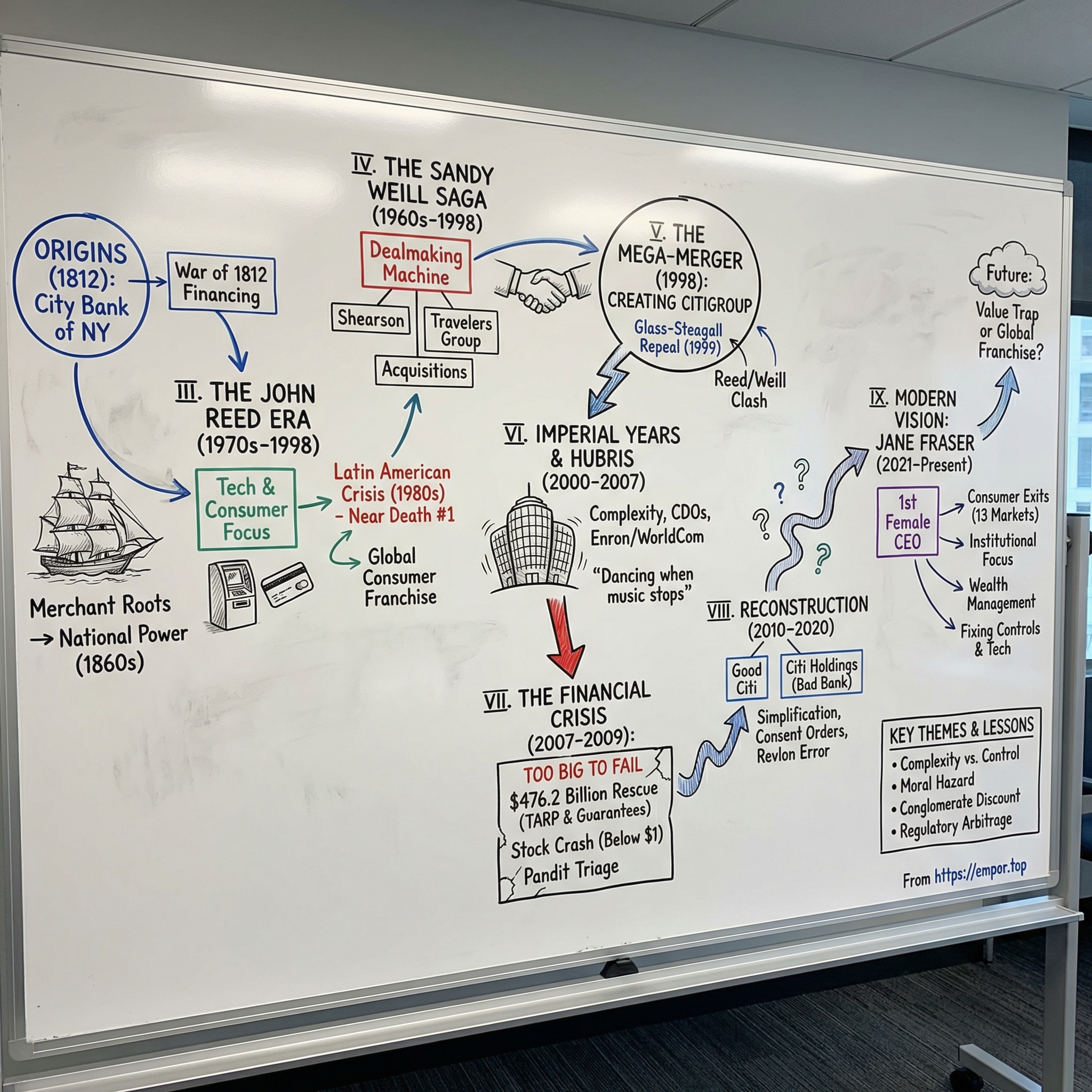

Picture the corner of Wall Street and William Street in lower Manhattan, 1812. The young American republic is weeks from declaring war on Britain. Banks are wobbling. Credit is tight. And yet a group of New York merchants squeezes into a counting house to sign incorporation papers for something called the City Bank of New York.

They think they’re starting a bank to serve a trading city in a fragile country. They don’t realize they’re laying the first stone in what will become, two centuries later, one of the largest and most complicated financial institutions ever assembled. A firm so sprawling it has been called too big to fail, and too complex to run.

Today, Citigroup operates in more than 160 countries. It employs roughly 240,000 people. It moves and safeguards trillions of dollars, sitting at the intersection of everyday consumer banking and the plumbing of global markets. Over its lifetime, it has lived through two world wars, the Great Depression, repeated boom-and-bust cycles, and a 2008 rescue that—counting cash and guarantees—reached nearly half a trillion dollars. It has also accumulated enough scandals to end most corporate legacies.

And still, it persists. Often trading below tangible book value, forever promising that the next reorganization will be the one that finally unlocks what the franchise should be worth.

So how did a 19th-century merchant bank become a modern financial superpower? How did it become so big that the government couldn’t let it fail—and so intricate that leadership struggled to control it? And if the “financial supermarket” has disappointed for decades, why does Citi keep surviving, and why do people keep betting on it?

This is a story about ambition—ambition that built an empire, and ambition that repeatedly drove it to the brink. It’s a story about regulatory chess, about a handful of pivotal deals and power struggles, and about executives who believed they could engineer stability out of complexity. It’s the story of John Reed’s technology-forward vision, Sandy Weill’s acquisition machine, and Jane Fraser’s attempt to unbuild what was built too quickly and held together for too long.

We’ll follow Citi’s arc from the era of sailing ships to the era of derivatives. From early near-death experiences in Latin America and commercial real estate to the ultimate near-death experience of 2008. And then to the present, where Citigroup remains a question investors can’t stop asking: is this a global franchise hiding in plain sight, or a value trap with great branding and stubborn math?

Along the way, a few themes will keep surfacing—ambition versus capability, complexity versus control, and the moral hazard that comes with being systemically important. These aren’t just Citi’s problems. They’re the story of modern finance.

II. Origins: From Merchant Bank to National Power (1812–1960s)

On June 16, 1812—two days before the United States declared war on Great Britain—the City Bank of New York got its charter from the New York State Legislature. The timing wasn’t an accident. A year earlier, Congress had refused to renew the charter of the First Bank of the United States, Alexander Hamilton’s great financial experiment. That decision left a hole in the country’s financial system, and the shareholders of the First Bank’s New York branch moved fast. They pooled their capital—about $2 million, a serious fortune at the time—and reincorporated themselves into a new institution with a simple premise: New York needed a bank, and America needed credit.

The first president was Colonel Samuel Osgood, a name that carried weight. He’d fought in the Revolutionary War, served as the nation’s first Postmaster General under George Washington, and sat comfortably inside New York’s elite circles. He set up shop in his own mansion on Wall Street, and almost immediately the bank was doing what wartime banks do: financing the War of 1812, lending to the federal government and to the merchants supplying the effort.

Then Osgood died within a year. And for decades after, the bank was… fine. A competent, state-chartered commercial bank in a crowded city, one of many serving a growing merchant class. For the first half-century, there was no inevitability to its future. The institution that would one day be Citigroup was, in its early life, easy to overlook.

That changed with Moses Taylor.

Taylor entered the picture in 1837 as a director and rose to president in 1856, a role he held until his death in 1882. He wasn’t just a banker. He was one of the era’s dominant businessmen—and his version of “banking” looked nothing like today’s.

A sugar merchant who expanded into railroads, gas utilities, and mining, Taylor used City Bank as the financial engine of his broader empire. The bank’s biggest depositor was Moses Taylor. Its biggest borrower was Moses Taylor. Its most valuable relationship was, unsurprisingly, Moses Taylor. He packed the board with family members and allies, and he steered the bank’s capital toward ventures he controlled. When he died, his estate was valued at more than $40 million, putting him among the richest Americans of the 19th century. City Bank had grown right alongside its de facto owner.

It was legal—regulation was thin and norms were different—but it left a cultural imprint that would echo through Citi’s history: the line between the institution and the ambitions of powerful individuals could get blurry. Sometimes profit came less from serving the world than from serving the people at the top.

The next great catalyst was the Civil War, which reshaped American finance and forced banks to choose sides—state versus federal, local versus national. In 1865, City Bank converted to a national charter under the National Bank Act and took a new name: the National City Bank of New York. This wasn’t just rebranding. National banks could issue currency backed by U.S. government bonds, and the federal framework gave them a kind of standardized credibility that attracted deposits. In a country still building trust in its financial system, that mattered.

If Moses Taylor defined National City’s power at home, James Stillman pushed it outward. Stillman led the bank from 1891 to 1909 and perfected what we’d now call relationship banking. He built deep ties with the industrial giants of the age—Standard Oil, American Sugar Refining, and the sprawling trusts that were consolidating American commerce. National City became the place where titans parked deposits and raised money, and the bank grew rich on the float and the influence.

But Stillman’s most consequential move wasn’t on Wall Street. It was overseas.

In 1897, National City became the first major American bank to establish a foreign department—an early bet that American business would not stay American for long. Where most U.S. banks saw foreign banking as exotic and unnecessary, National City started building correspondent relationships across Europe, Latin America, and Asia. By 1915, it had become America’s leading international bank.

The logic was straightforward: as American manufacturers sold to the world, they needed letters of credit, foreign exchange, and trade finance that worked across borders. National City positioned itself as that bank, opening branches across Latin America, Asia, and Europe. By the 1920s, it had more foreign branches than any other U.S. institution.

That global DNA became a permanent competitive advantage—and a permanent source of risk. It gave the bank reach that rivals couldn’t match. It also ensured National City would show up, again and again, in the blast radius of currency collapses, sovereign defaults, and emerging-market crises.

Then came the Great Depression, and National City’s earlier appetite for the 1920s boom nearly broke it. Through an affiliate called National City Company, the bank had eagerly packaged and sold securities. After the crash, the stories that surfaced were brutal: executives selling shaky securities, favorable insider loans, stock manipulation. The bank’s president, Charles Mitchell, became a national symbol of Wall Street excess. He resigned under pressure and was prosecuted for tax evasion—ultimately acquitted, but publicly tarnished.

Washington responded with a wall: the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which separated commercial banking from investment banking to prevent exactly the conflicts of interest that had proven so destructive. National City dumped its securities affiliate and retreated into plain-vanilla banking. It would be nearly sixty-five years before Citi found a way to stitch those worlds back together.

The postwar era was steadier, and quieter. The bank grew its branch network, expanded corporate lending, and maintained its international footprint. It also evolved its identity: it began calling itself First National City Bank in 1955, later “Citibank” in 1976, with the holding company taking the name Citicorp in 1974. It was big, respected, and—by the standards of what was coming—conventional.

But as the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, Citibank had a problem that wouldn’t show up on a balance sheet: it didn’t yet have a compelling vision for what modern banking could become.

That was about to change.

III. The John Reed Era: Innovation and Near-Death (1970s–1998)

John Reed joined Citibank in 1965, fresh out of MIT’s Sloan School with a hybrid education in engineering and business. He wasn’t a country-club banker, and he didn’t come up through credit committees or trading desks. He was an operations mind—someone who looked at a bank and saw systems, bottlenecks, and process failures that could be designed away.

His first real test was the back office, which was buckling under its own paperwork. Checks, payments, reconciliations—everything was getting processed too slowly, too expensively, and with too many mistakes. Reed treated it like an engineering problem. He brought in operations research talent, leaned hard into computers, and redesigned workflows that had been patched together over decades. By the early 1970s, a part of the bank most people treated as a cost center had become something closer to an edge.

But Reed wasn’t aiming to be the best-run bank in the back room. He was fixated on the front door: consumer banking.

At the time, big commercial banks mostly saw retail customers as clutter—small balances, lots of service, not enough profit. Corporate lending was where status and margins lived. Reed saw a different equation: millions of customers, recurring needs, and technology that could finally make the economics work at scale.

In 1970, at just 31, he was put in charge of Citibank’s consumer business. He’d spend the next two decades turning it into one of the most advanced retail banking operations in the world.

One early engine was the credit card. Reed understood that cards weren’t just a convenience for payments; they were a standardized lending product. You could extend credit broadly without building a traditional loan operation for each borrower. Citibank pushed aggressively—expanding its card business nationwide and building one of the largest portfolios in the country.

The other engine was the ATM. In the late 1970s, Citibank made a huge bet: it would blanket New York City with machines that dispensed cash around the clock. The price tag—hundreds of millions of dollars—looked absurd for something that, to skeptics, seemed like a fancy vending machine. Competitors rolled their eyes.

Reed wasn’t chasing novelty. He was chasing behavior. Banks, he believed, competed on convenience as much as rates and products. If your bank was the one with an ATM on the corner when you needed cash at 2 a.m., you didn’t just transact with it—you built a relationship with it. Over time, that network became a moat in New York that rivals couldn’t quickly copy.

By the early 1980s, Reed had become a star inside Citicorp. In 1984 he was named president, the clear successor to chairman Walter Wriston. And then, just as the story reads like a clean ascent, Citi walked right up to the edge.

The Latin American debt crisis was the first real signal that Citibank’s global reach was outrunning its ability to measure risk. In the 1970s, the bank had lent heavily to developing countries, especially across Latin America. The assumptions felt reasonable at the time: sovereign borrowers don’t go bankrupt, commodity revenues were strong, and the loan spreads looked great.

Then Mexico announced in August 1982 that it couldn’t service its debts. Panic spread. Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela—one after another, governments looked like they might default. Citicorp’s exposure to the region was larger than its total equity. By any practical yardstick, the bank was staring at insolvency.

Reed became chairman and CEO in 1984 and spent years navigating a crisis that couldn’t be solved with a single write-down. Writing the loans off would have vaporized the bank’s capital. So Citi negotiated restructurings, pressed for government support, and tried to buy time. In 1987, Reed made a move that landed like a thunderclap: Citicorp took a $3 billion reserve against its Latin American loans, the largest loss in U.S. banking history at the time. It crushed earnings, but it signaled the bank was no longer pretending.

Citicorp survived. Latin American economies stabilized. The loans weren’t good, but they weren’t total losses either. Reed came out looking like the rare executive who could face a disaster without flinching.

Then came the second near-death experience.

In the late 1980s, Citicorp expanded aggressively into commercial real estate—office towers, malls, development deals. When that market cracked in 1990 and 1991, the bank was left with billions in troubled loans. A recession hit at the same time, squeezing consumer credit and driving up card losses. Capital ratios sagged below regulatory minimums.

By 1991, Citicorp was weak enough that regulators seriously contemplated forcing a sale or taking the bank over. The stock slid to $8. Analysts started writing the ending in advance. Reed responded with a restructuring as painful as it was necessary: 15,000 layoffs, deep expense cuts, asset sales, and fresh capital raised wherever the market would allow it.

The recovery didn’t happen overnight. But by the mid-1990s, Citicorp had clawed its way back—not just to stability, but to momentum. The consumer machine Reed built threw off profits. Credit cards became a powerhouse. International operations, especially in emerging markets, grew quickly. Years of technology investment began to look less like overhead and more like leverage. From 1991 to 1998, Citicorp’s stock price rose roughly fivefold.

And with survival came ambition.

Reed began reaching for the idea that had been hovering over Citi for decades: a true universal bank, able to offer every major financial service to every kind of customer, anywhere in the world. But Citicorp still lacked key pieces—investment banking, insurance, asset management. To build the whole machine, Reed didn’t just need a strategy.

He needed a partner.

And across town, a very different kind of dealmaker was building his own version of the same dream.

IV. The Sandy Weill Saga: Empire Builder (1960s–1998)

Sanford I. Weill—Sandy to everyone who knew him—was not supposed to end up as one of the most powerful men in American finance. He was born in Brooklyn in 1933 to Polish Jewish immigrants, grew up without much money, and became the first in his family to go to college. After Cornell, in 1955, he landed on Wall Street at the very bottom: a runner, literally carrying securities certificates from one firm to another.

What Weill lacked in pedigree, he made up for in instinct. He could look at a business and see, almost immediately, where the waste was hiding—and how to squeeze it out. Where others saw a venerable institution, Weill saw a collection of departments, expenses, and incentives that could be rearranged. And he had an appetite for deals that never seemed to turn off.

In 1960, Weill and three partners scraped together $200,000 to buy a small brokerage firm. They named it Carter, Berlind, Potoma & Weill. It was a modest start, but the ambition wasn’t modest at all. Over the next two decades, he rolled up firm after firm, turning that little shop into Shearson, one of Wall Street’s major brokerages. The method barely changed: buy franchises with recognizable names, slash costs, consolidate operations, and move on to the next target.

By 1981, Shearson was big enough to be acquired. American Express bought it for nearly $1 billion in stock. Weill became president of American Express and, in his mind, the natural successor at the top.

It didn’t work out that way. American Express’s patrician culture didn’t mix with Weill’s deal-driven, expense-cutting style. He was marginalized, then forced out in 1985. At 52, after building Shearson into a powerhouse, he was suddenly on the outside.

Most people would have walked away—wealthy, angry, and done. Weill treated it as intermission.

In 1986, he took control of Commercial Credit, a struggling consumer finance company that had been part of Control Data Corporation. It wasn’t glamorous. It was the kind of lender that made loans banks didn’t want to make—what the industry would later label subprime. The business was losing money and fading into irrelevance.

Weill saw a platform.

He moved the headquarters from Minnesota to New York, installed his team, and went straight to the operating model. Layers came out. Unprofitable branches closed. Contracts got renegotiated. Within a year, Commercial Credit was profitable again—proof, in Weill’s mind, that the machine worked.

Then he did what he always did next: he started buying.

In 1988, Commercial Credit merged with Primerica, a diversified financial services company that owned Smith Barney. Overnight, Weill was back in the brokerage world. More acquisitions followed, each one widening the footprint: A.L. Williams, a life insurance agency. Travelers, the insurance company. And then the ultimate bit of symmetry—buying back Shearson, his old creation, from American Express.

The pace was dizzying, but the pattern was familiar. Weill bought companies with strong franchises and bloated cost structures, stripped out redundancies, pushed cross-selling across the new portfolio, and demanded results. He didn’t “oversee integration” from a distance. He was known for personally going through budgets line by line and making executives justify expenses down to the smallest items.

By the mid-1990s, the collection of businesses had been welded into something with a name that matched Weill’s ambition: Travelers Group. It had insurance, brokerage, and asset management. It was profitable and growing. It also had a problem—at least, in Weill’s view.

It still wasn’t a bank.

To Weill, the ultimate prize wasn’t just products. It was deposits. A banking charter meant stable, low-cost funding. It meant commercial lending relationships. And it meant a kind of permanence—an anchor for the entire conglomerate.

In 1997, he made another leap, acquiring Salomon Brothers for $9 billion. Salomon brought the prestige and firepower of a legendary bond trading operation, plus real investment banking capability. It also brought a culture of risk-taking that would later come back to haunt the broader enterprise. And even with Salomon, Weill still didn’t have what he really wanted: a commercial bank—and the global brand that came with one.

He had been studying Citicorp for years. He admired Reed’s consumer banking engine. He coveted Citi’s international network. Put Travelers’ insurance and securities businesses together with Citicorp’s consumer and commercial banking, and Weill believed you’d get something finance had never seen: a true financial supermarket, able to serve every major financial need under one roof.

There was, of course, one giant obstacle.

The Glass-Steagall Act—the Depression-era wall between commercial banking and securities—made the combination illegal.

Weill was not the kind of man who let a law decide the size of his next deal.

V. The Mega-Merger: Creating Citigroup (1998–2000)

The dinner happened in late February 1998, in Sandy Weill’s hotel suite in Washington, D.C. Across from him sat John Reed. They’d known each other for years in the way senior finance executives “know” each other: familiar faces, occasional handshakes, mutual awareness. Not partners. Not collaborators.

That night, they finally talked like people plotting a future, not merely comparing notes on an industry. They talked about globalization. About technology. About the way financial services seemed destined to consolidate into a handful of giants. And, inevitably, they talked about what they could build if they stopped circling each other and joined forces.

What they were really discussing was a merger so large it sounded like fiction: a $140 billion combination of Citicorp and Travelers Group, creating a new company called Citigroup. It would fuse consumer and commercial banking with investment banking, insurance, asset management, and consumer finance. In one stroke, it aimed to create the first true American “universal bank” since the Great Depression-era reforms had forced banking and securities apart.

And it had a catch that would have killed a more cautious deal.

The merger, as proposed, was illegal.

Glass-Steagall prohibited a bank from affiliating with insurance underwriting. Citicorp was a bank. Travelers owned major insurance companies. Under the law, they weren’t supposed to live under the same roof. But Weill had found the crack in the wall: the Federal Reserve could grant a temporary waiver—time to divest the forbidden pieces, or time for Washington to rewrite the rules.

Weill wasn’t planning to divest. He was planning to win.

For years, large banks had been pressing Congress to dismantle Glass-Steagall. They argued that the restrictions were antiques—bad for innovation, bad for American competitiveness, and out of step with Europe and Japan, where universal banks were normal. By 1998, the mood in Washington had shifted from “never” to “why not?”

After the merger was announced on April 6, 1998, Reed and Weill went to work on the part of the deal that didn’t show up in the term sheet. They worked the phones. They met with lawmakers and regulators. They unleashed lobbyists and made their case, again and again: this wasn’t a loophole. It was the future. Congress should update the law to match it.

The Federal Reserve granted the waiver. On October 8, 1998, the merger closed. Citigroup was born—operating on a two-year exemption and a breathtaking assumption: that the government would eventually legalize what Citi had already built.

It did. In November 1999, President Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, repealing key provisions of Glass-Steagall and effectively blessing the Citigroup model. Weill hadn’t just assembled a new corporate giant. He had helped reshape the rules of American finance around it.

But inside the newly legalized empire, the seams were already splitting.

Reed and Weill had agreed to a co-CEO arrangement—one of those structures that sounds diplomatic on announcement day and turns brittle the moment real decisions pile up. They were opposites. Reed was a systems guy: operations, technology, process, scale. More engineer than politician. Weill was a force of nature: acquisitions, cost-cutting, and management by presence and persuasion. Reed wanted to build. Weill wanted to buy. Reed delegated. Weill micromanaged.

And their clash was just the top layer. Citicorp’s bankers looked at Travelers’ investment bankers and saw fee-chasers. Travelers’ deal people looked at Citicorp and saw slow-moving bureaucracy. Insurance executives wondered how they fit into a bank at all. The consumer finance employees inherited from Commercial Credit felt like they’d been invited to the party but told to use the side entrance.

Meanwhile, the big promise—the synergies—proved harder than the pitch decks implied. Cross-selling sounded elegant: insurance to banking customers, brokerage to retail depositors, investment banking to corporate clients. In practice, customers didn’t wake up craving a single provider for every financial need. They wanted the best product, with the least friction, at the best price. Integration was expensive. Culture was combustible. The “financial supermarket” was real as an org chart and elusive as a lived experience.

By early 2000, the co-CEO experiment was collapsing under its own weight. The board, packed with directors aligned with Weill after years of dealmaking, moved to end it. On February 28, 2000, Citigroup announced that Reed would retire. The language was polished—mutual agreement, orderly transition. People inside the company described it more bluntly: a boardroom coup.

Reed left with a $30 million golden parachute. Over time, he would express regret, telling interviewers that combining commercial and investment banking had been a mistake. Eventually, he would even argue for bringing Glass-Steagall back.

Weill, now the sole chief of the new empire, had won the most important internal battle. He would soon learn a harder truth: creating a financial superpower is one thing.

Running it is another.

VI. The Imperial Years: Growth and Hubris (2000–2007)

The Citigroup Sandy Weill now commanded was staggering in its scope—and in its complexity. It operated in more than 100 countries. It employed about 270,000 people. It served roughly 200 million customer accounts. It offered nearly everything with a fee attached: commercial banking, investment banking, insurance, asset management, consumer finance, credit cards, mortgages, and a long tail of other products. The organizational chart didn’t read like a plan so much as a tangle. No one person could realistically see all the moving parts at once.

Weill tried anyway. He was famous for being hands-on: personally reviewing results, interrogating executives, pushing for accountability. But even he couldn’t fully master what he’d built. The enterprise was simply too big, too global, and too many businesses had been stitched together too quickly.

So Weill did what had always worked for him: he kept buying.

From 2000 through 2003, Citigroup went on another acquisition run. It bought Banamex, Mexico’s largest bank, for $12.5 billion—at the time, the biggest acquisition of a Latin American company by a U.S. firm. It purchased Golden State Bancorp to expand in California. It picked up European asset managers and Asian insurance businesses. Each deal added scale, but it also added new systems, new cultures, and new points of failure. Integration ate management attention. Governance got harder. The center of the company had to control more and understood less.

The risk piled up quietly, too—especially in the part of Citi that carried the sharpest edges: the investment bank built on Salomon Brothers. It was pushing deeper into structured products: collateralized debt obligations, mortgage-backed securities, and the exotic derivatives that turned housing loans into seemingly high-grade paper. Citi was becoming a major player in markets that were growing faster than anyone’s ability, or willingness, to stress-test them.

And the first cracks showed up early—if you were willing to look.

In 2001, Enron collapsed, and Citigroup was in the blast radius. The bank had financed Enron, helped structure transactions that obscured the company’s condition, and distributed Enron securities to investors. When the fraud surfaced, Citi faced lawsuits, regulatory scrutiny, and reputational damage that cut straight through the “trusted global institution” brand it sold.

Then came WorldCom. Citigroup had been a key banker to the telecom giant—arranging bond offerings, extending credit, keeping the relationship humming. When WorldCom’s accounting fraud exploded, Citi was back in the crosshairs. The bank ultimately paid $2.65 billion to settle an investor lawsuit over its role in the scandal.

These weren’t random bad headlines. They were signals—evidence of a culture that too often prized getting the deal done over asking the uncomfortable questions. Revenue over restraint. Short-term wins over long-term trust. And inside a sprawling conglomerate, the businesses generating the loudest profits tended to get the longest leash. Headquarters didn’t press too hard as long as the numbers kept landing.

By 2003, Weill—under regulatory pressure and worn down by the job—began preparing to hand the keys to someone else. He elevated Charles Prince, Citigroup’s general counsel, to CEO. Prince was a lawyer and a fixer, a corporate diplomat who had helped Weill navigate Washington and the regulators. But he wasn’t a career banker, and he wasn’t built in Weill’s mold of hard-charging operator. He inherited not a single institution, but a stitched-together empire.

Prince’s era would be crystallized by one sentence. In July 2007, with the subprime mortgage market already starting to buckle, a Financial Times reporter asked about Citi’s continued involvement in leveraged lending. Prince answered: “When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing.”

It was an astonishingly candid description of the moment. Plenty of people on Wall Street could feel the room getting hot. The housing boom looked stretched. The structured products looked fragile. Everyone knew that when liquidity turned, things would break. But the fees were enormous, competitors were aggressive, and the industry had convinced itself it could sprint for the exit before the doors narrowed.

Citigroup kept dancing. Inside the investment bank, structured products became a factory. CDOs—those byzantine securities that repackaged subprime mortgages into layers that could be stamped AAA—generated fees for creating them, fees for selling them, and trading profits while Citi held inventory along the way. It was hugely lucrative. It also meant Citi was accumulating more and more exposure, much of it sitting on its own balance sheet.

The people whose job it was to slow things down didn’t have the leverage to do it. Risk management was sidelined. Concerns were brushed aside or overruled. Business heads—paid on volume and revenue—resisted constraints. And the board, filled with Weill-era loyalists and not known for deep financial-services skepticism, didn’t force the hard conversations.

So when the music finally stopped, Citigroup wasn’t just caught on the dance floor.

It was holding tens of billions of dollars in assets that were about to become nearly impossible to price—and it didn’t yet understand how severe the losses could be.

VII. The Financial Crisis: Too Big to Fail (2007–2009)

The unraveling started in the summer of 2007, when the subprime mortgage market finally cracked. Home prices—long treated as a one-way escalator—began to slip. Adjustable-rate mortgages reset. Monthly payments jumped. Borrowers fell behind. Foreclosures surged. And the mortgage-backed securities Citigroup had helped create—and still held in size—started to tumble.

At first, Citi’s leadership tried to frame it as containable. Then, in October 2007, Citigroup reported a $6.5 billion write-down tied to subprime exposure. The market didn’t just flinch; it recoiled. Not long after, Chuck Prince was out. In came Vikram Pandit, a former investment banker who’d arrived at Citi through an acquisition—walking into the job at the exact moment the floor was giving way.

And the losses weren’t a one-time hit. They kept arriving in waves. Roughly $18 billion in the fourth quarter of 2007. Another $15 billion in the first quarter of 2008. The scale became almost hard to process—numbers so big they stopped feeling like accounting and started feeling like weather. Each quarter, Citi told investors it had turned the corner. Each quarter, the corner moved.

A huge part of the problem was epistemic: nobody really knew what the bank owned. Not in a clean, mark-it-and-move-on sense. The structured products Citi had loaded up on—especially CDOs—were layered, interconnected, and dependent on assumptions that only worked in normal markets. Once housing began falling across the country, the models that produced comforting valuations stopped making sense. There wasn’t just uncertainty about losses. There was uncertainty about how to measure them.

Then September 2008 hit. Lehman Brothers collapsed. The financial system seized. And Citigroup—already weakened—started to look existentially fragile.

The stock told the story in brutal real time. From above $50 a share in 2006, it fell below $20 in September 2008, then below $10 in October, then below $5 in November. Confidence evaporated. Depositors pulled money. Counterparties demanded collateral. The short-term funding markets Citi relied on to function day-to-day froze, and the firm’s size—once its badge of dominance—became a source of terror. If Citi went down, it didn’t just hurt shareholders. It threatened the system.

The rescue came in waves.

First, in October 2008, Citigroup received $25 billion from the U.S. Treasury under TARP, structured as a preferred stock investment. It bought time. It didn’t solve the problem.

A month later, with the stock still collapsing and the threat of a bank run growing, Washington came back with something bigger. Treasury injected another $20 billion. And then came the centerpiece: the Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC agreed to backstop more than $300 billion of troubled assets—effectively insuring Citi against further catastrophic losses. In return, the government received more preferred shares and warrants.

By the Congressional Oversight Panel’s later tally, the combined cash and guarantees totaled $476.2 billion. This was too big to fail, no longer as a theory or an argument, but as a policy choice the government made on the fly.

Pandit, less than a year into the CEO role when the crisis hit its peak, moved into triage mode. He cut tens of thousands of jobs. He started selling assets and entire businesses to raise capital. He negotiated constantly—with regulators, Treasury officials, and any counterparty whose continued trust might keep the lights on for another week.

Even with the rescue in place, the public markets kept pressing the panic button. In March 2009, Citi’s stock traded below $1 a share. The company that not long earlier had been valued north of $250 billion now had a market capitalization smaller than plenty of regional banks. Nationalization talk wasn’t fringe—it was part of the daily commentary. Would the government wipe out shareholders and take it over outright?

It didn’t. Citi survived through a combination of government support, aggressive cuts, asset sales, and a financial system that slowly—unevenly—began to thaw.

But the survival came at a steep price for shareholders. By the end of 2009, Citigroup raised $20.5 billion in public equity, issuing shares at distressed prices and heavily diluting existing owners, and used the proceeds to repay the $20 billion in TARP preferred stock with its punitive terms.

The government’s exit took longer. Treasury held common shares, converted from the preferred and warrants, and sold them down over time. By the time the last shares were sold in December 2010, the government had booked roughly $12 billion in profit.

That tidy headline obscured what really happened. The government didn’t just provide capital. It provided belief—the implicit promise that Citigroup would not be allowed to fail. That promise stabilized funding, slowed the flight of customers and counterparties, and kept a wounded institution alive through what should have been a fatal loss of confidence. The private upside had been pursued for years; the systemic downside, in the moment that mattered, was absorbed by the public sector.

And for investors who held Citi stock through the crisis, the lesson was unforgiving. Too big to fail didn’t mean too safe to own. It meant the institution would be saved—not the people who owned it. A share bought around $50 in 2007 was worth roughly $4 in 2010, even after a 1-for-10 reverse split that simply changed the optics. In real terms, the loss was devastating—well over 90% for those who lived through it.

VIII. The Reconstruction: Simplification and Survival (2010–2020)

The decade after the crisis should have been Citigroup’s redemption arc. The firm had survived. It had the government out of the cap table. It had a mandate—really, an order—to simplify. In a normal story, that’s where the hero gets lean, gets focused, and starts winning again.

Citi’s 2010s didn’t read like that. They read like a long, grinding slog: incremental improvements, periodic humiliations, and a stock market that never quite believed the turnaround was real.

The first problem was structural. In the aftermath, Citi split itself in two. Citicorp housed the businesses it wanted to keep. Citi Holdings became the quarantine zone: toxic crisis-era assets and “non-core” operations that were supposed to be sold or run off over time. On paper, it was elegant. Put the mess in one box, keep the franchise in another, and slowly empty the bad box.

In practice, that bad box fought back. The assets were impaired, illiquid, and hard to value. Selling them often meant locking in losses. Keeping them tied up capital and management attention. Citi Holdings did shrink year after year, but it did so the way a glacier melts—slowly, painfully, and at a cost.

And even in “good Citi,” the problem wasn’t just what it owned. It was what it was: a universal bank that promised diversification and scale, but delivered regulatory complexity, operational friction, and a cost structure that peers—especially JPMorgan—seemed far better equipped to manage.

Vikram Pandit stayed in the CEO seat until 2012. Then he was gone, abruptly, in a departure that sounded polite in press releases and looked like a boardroom ambush to everyone watching. However it happened, the signal was unmistakable: patience had run out.

His replacement was Michael Corbat, a Citigroup lifer who had run the Europe, Middle East, and Africa division. Corbat wasn’t there to sell a grand new vision. He was there to do the unglamorous work: cut costs, satisfy regulators, and try to rebuild a bank that could earn its keep.

The regulator piece was relentless. Post-crisis, Citi was operating under multiple consent orders—formal agreements that required specific fixes. The bank needed stronger risk management and compliance, upgraded technology, and detailed “living wills” showing how it could be wound down in an orderly way if it ever failed again. This wasn’t optional. It was a condition of being allowed to stay in business at Citi’s scale.

And Citi kept stumbling in public. The most painful example was the stress tests. In 2014, the Federal Reserve rejected Citigroup’s capital plan, which meant no big dividend increases and no meaningful share buybacks. The Fed pointed to weaknesses in Citi’s ability to project revenues under stress scenarios—a particularly sharp rebuke for a firm that prided itself on sophistication.

For shareholders, it was salt in the wound. While other big banks were steadily returning capital through dividends and buybacks, Citi was stuck on the sidelines, sitting on excess capital it couldn’t fully deploy, still paying for the sins of the last era.

Corbat spent years pushing through remediation: investing heavily in compliance and risk infrastructure and trying to convince regulators that Citi had truly changed. Some consent orders were lifted. Others lingered. The bank stayed under a cloud—never quite free of the sense that the next exam could turn into the next headline.

Then, in 2020, Citi handed the world a case study in operational risk.

During what should have been a routine interest payment, the bank accidentally wired $900 million to Revlon creditors. The mistake was blamed on confusing software and weak controls. Some creditors refused to return the money. The dispute turned into litigation that ran all the way into federal court. Citi ultimately recovered most of the funds, but only after a long, bruising fight.

It was more than an embarrassing error. It crystallized a fear that had been building for years: Citi’s technology and controls weren’t just imperfect—they were patchwork, and they weren’t keeping up with the complexity of the institution they were supposed to govern. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency responded with additional consent orders demanding sweeping improvements.

Through the entire decade, the market delivered its own verdict. Citi’s stock persistently traded below tangible book value—investor shorthand for a brutal idea: the franchise is worth more in pieces than as a whole. The conglomerate premium Sandy Weill had promised had flipped into a conglomerate discount. Complexity wasn’t creating value. It was consuming it.

So by 2020, when Corbat announced his retirement, Citi was still, somehow, a turnaround story. Citi Holdings was largely wound down. The technology investments were in motion. The regulatory remediation was ongoing. But returns remained stubbornly below what shareholders demanded, peers continued to outperform, and the stock still couldn’t escape the basement.

The board decided the next CEO would not be a typical succession. They reached for a different kind of leader—someone who would make history.

IX. Modern Citigroup: Jane Fraser's New Vision (2021–Present)

On March 1, 2021, Jane Fraser became CEO of Citigroup—the first woman to lead a major U.S. bank. The milestone mattered. But inside Citi, the headline came with a far heavier subtext: simplify the machine, fix the controls, and finally produce the kind of returns a franchise this large should be capable of.

Fraser was a Citi lifer, but not a conventional one. She grew up in Scotland, earned an MBA at Harvard, and spent much of her early career at McKinsey before joining Citigroup in 2004. Over the next decade and a half, she ran major parts of the company—Latin American consumer banking, then global consumer banking—before becoming president under Michael Corbat. She knew Citi’s sprawl from the inside. And she’d been trained, almost professionally, to ask the questions big organizations learn to avoid.

Her first big decision signaled she wasn’t going to protect legacy for its own sake. Within weeks, Fraser announced Citi would exit consumer banking in 13 markets—retail franchises across Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Mexico that were too small, too costly, or simply not worth the fight. The list included Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, South Korea, and other countries where Citi had been present for decades.

It was a clean break with a belief that had defined Citi since John Reed: that a global consumer footprint was inherently strategic. Fraser was saying out loud what the numbers had been implying for years. Citi could be global, or it could be a broad retail bank everywhere. It couldn’t be both—at least not with acceptable economics.

In place of the old story, she offered a narrower one. Citi would lean into the parts of the franchise where its international network actually compounded: serving institutional clients—multinationals, governments, financial institutions—whose needs span borders and currencies. It would grow wealth management for clients who wanted global access. And it would keep consumer banking where Citi had enough scale to matter: the United States and Mexico.

The logic was straightforward. The hard part was turning that logic into reality.

Exiting retail banking in a dozen-plus countries isn’t like closing a few branches. Each market has its own regulators, labor rules, and buyer dynamics. Employees have to be transitioned, customer relationships and products moved, and—most painfully—technology untangled. Years into the plan, some exits were still not complete, a reminder that simplification at Citi is never a single decision. It’s a multi-year disentanglement.

And while Fraser was trying to shrink complexity on the front end, Citi still had to fix what was underneath. The Revlon wire mistake in 2020 hadn’t just embarrassed the bank; it triggered consent orders that effectively put Citi on a regulator-supervised rebuild of its risk management, data, and controls. Fraser made clear the remediation would take years and cost hundreds of millions annually—money and attention that couldn’t go to growth, buybacks, or anything else investors like.

Regulators, for their part, kept the pressure on. In 2024, Citi was hit with additional penalties—$136 million in fines—for insufficient progress. The subtext was blunt: effort wasn’t the standard. Execution was. For a company that once sold itself as a technology-forward banking pioneer, it was an uncomfortable position to be in—still struggling with the fundamentals of operational reliability.

The outside world didn’t make the turnaround easier. Higher interest rates, which can be a tailwind for banks, also stressed parts of the system—commercial real estate included. Geopolitics added its own friction. The Russia-Ukraine conflict forced Citi to navigate sanctions and, ultimately, to exit Russia entirely, taking significant losses. And the inherent volatility of emerging markets—always part of Citi’s global bargain—never really goes away.

Still, there were real signs the franchise wasn’t broken. Wealth management showed growth. The institutional business, especially transaction banking—the behind-the-scenes rails that help corporations move money around the world—remained a core strength. The consumer exits moved forward, even if slower than anyone would prefer. And, perhaps most importantly, the company’s direction became easier to explain: fewer countries, fewer moving parts, more focus on the areas where Citi is genuinely differentiated.

By late 2025 and into 2026, the transformation was still unfinished. The stock still traded below tangible book value. Consent orders remained in place. Returns improved but continued to lag top-tier peers. But Citi was no longer pretending there was a quick fix. Fraser’s approach was closer to an overhaul than a slogan—and after two decades of restructurings that promised simplicity while adding complexity, that realism became its own form of credibility.

If you’re looking at Citi today, the scoreboard is fairly simple: whether return on tangible common equity can rise to a level that clears the cost of capital; whether consent order remediation is progressing fast enough to lift regulatory constraints; and whether the consumer exits land cleanly, leaving behind a bank that’s smaller in footprint but sharper in purpose.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Citigroup’s two-century history is a case study in what happens when ambition outruns execution—and in what it takes to survive anyway. The names and acronyms change, the balance sheet shifts, the org chart gets redrawn. But the underlying lessons show up again and again.

The Conglomerate Discount Is Real

Sandy Weill sold Wall Street on a simple idea: bolt commercial banking, investment banking, insurance, and consumer finance together, and the whole will be worth more than the parts. Cross-sell everything to everyone. Smooth earnings through diversification. Build the financial supermarket.

Citi mostly got the opposite. Complexity created opacity—investors struggled to understand what they actually owned. Integration costs ate the “synergies.” And the cultural friction between businesses didn’t just slow execution; it warped incentives.

The market’s verdict has been consistent for most of the last two decades: Citigroup often traded below tangible book value. In plain English, investors valued the company more as a breakup candidate than as a single integrated machine. The financial supermarket may have reshaped the industry, but as a value-creation model, it’s been deeply disappointing.

Regulatory Arbitrage Is a Dangerous Game

Weill made the Citicorp-Travelers merger happen before Glass-Steagall was repealed, then helped push Washington to legalize it afterward. It worked—at least on the timeline that mattered for getting the deal done.

But the win came with a bill. The very combination Glass-Steagall was designed to prevent—commercial banking intertwined with securities and risk-taking—was central to the fragility that exploded in 2008.

You can sometimes outrun regulation. You can even change it. But playing chicken with the rulebook is rarely a permanent edge. Eventually the rules tighten, the scrutiny escalates, and the costs show up—often years later, often all at once.

Too Big to Fail Creates Moral Hazard

Citi’s bailout made one thing brutally clear: too big to fail is not the same as too safe to own. The government rescued the institution, not its shareholders. Citi survived; equity holders were wiped out in all but name.

And the incentives that got the firm there didn’t disappear in the moment of rescue. The executives who built the risk machine didn’t face consequences proportional to the damage. People who questioned the buildup were too often sidelined, while the engines producing short-term revenue got rewarded.

That’s the moral hazard: when markets believe the government can’t let you fail, risk starts to feel cheaper than it really is. Gains are private in the good years; the worst losses get pushed outward in the bad ones.

Cultural Integration Is Harder Than Financial Integration

Financial mergers rarely fail because the spreadsheet math is wrong. They fail because the people don’t blend.

Citicorp’s commercial bankers and Travelers’ investment bankers lived in different worlds—different pay structures, different risk tolerance, different definitions of “a good quarter.” On paper, they were one company in 1998. In practice, the integration never fully finished. Even decades later, Citi has been managing the second-order effects of a cultural collision that started on day one of the mega-merger.

Risk Management Cannot Be an Afterthought

Before the crisis, Citi’s risk function didn’t have enough independence or authority to slow the businesses that were producing the most revenue. Concerns could be overruled. The board didn’t consistently force the hard questions. And the result wasn’t just “some losses.” It was a concentration of exposure that put the entire firm in jeopardy.

The lesson is simple and harsh: risk management has to be structurally empowered. It needs real teeth, and it needs active board engagement. If it becomes subordinate to business-unit profitability, it will eventually be ignored—until the day it’s too late.

Capital Allocation in Financial Services Is Different

For a bank, capital isn’t just something you raise to build factories. It’s the raw material. The core management job is deploying it into businesses that earn above the cost of capital—and pulling it out of the ones that don’t.

Citi spent years allocating capital into areas where it lacked a durable edge, from subscale international retail operations to structured products it didn’t fully understand. The result was predictable: returns that struggled to clear the hurdle rate, and a stock that reflected that skepticism.

Succession Planning Matters

Citi’s leadership transitions have often been abrupt, political, or crisis-driven. John Reed built a world-class consumer franchise and still got pushed out. Weill handed the company to Chuck Prince, a lawyer rather than a banker, at the exact moment the risk machine was accelerating. Vikram Pandit’s exit was sudden and widely read as a boardroom break.

The pattern points to a governance problem: succession that isn’t treated as a core strategic process tends to get decided under stress. And when leadership changes are driven by urgency or loyalty instead of fit and capability, the institution pays for it later.

XI. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

The bear case for Citigroup starts with a blunt pattern: for roughly twenty years, Citi has promised a turnaround, and investors have mostly gotten restructurings instead of sustained outperformance. If you believe history is the best predictor here, the default assumption is that the next chapter looks like the last one—incremental progress, punctuated by setbacks, with peers pulling farther ahead.

The clearest symptom is return on tangible common equity, the number bank investors tend to care about most. In stronger years, Citi has managed something like the low double digits. Meanwhile, JPMorgan has been in a different league, producing meaningfully higher returns with far more consistency. That gap isn’t a trivia point—it compounds into a widening distance in capital generation, buybacks, and ultimately shareholder value.

Then there’s the regulatory overhang. Consent orders that were supposed to fade into the background have remained stubbornly present. Citi has spent heavily on remediation, yet the Revlon wiring error—and the penalties that followed—became the uncomfortable proof that “we’re investing in controls” is not the same as “the controls work.” The longer these orders stay in place, the more they function like a tax on the business: management attention diverted, technology spend forced, and capital return constrained.

You can also argue the Fraser plan is simply moving at Citi speed—which is to say, slower than the competitive environment allows. While Citi works through multi-year disentanglements, competitors keep compounding. JPMorgan continues to extend its lead in multiple businesses. Bank of America’s consumer scale remains a formidable engine. Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have leaned hard into wealth management and fee-based earnings. And outside the traditional peer set, fintechs and non-banks keep picking off specific profit pools, turning parts of “banking” into lower-margin utilities.

Finally, Citi’s global footprint cuts both ways. Operating in more countries than any other U.S. bank is a real differentiator, but it also means more exposure to geopolitics, sanctions, and emerging-market volatility. When the world is calm, diversification looks like resilience. When the world is messy, it can look like a portfolio of unforced errors.

Step back, and the competitive critique is essentially this: Citi has scale, but scale hasn’t reliably translated into superior profitability. It has a real network in transaction banking, but not a monopoly. Its brand exists everywhere, but years of issues have taken a toll on trust. And in a business where confidence and operational excellence are the product, “good enough” doesn’t stay good enough for long.

The Bull Case

The bull case doesn’t deny any of that. It argues something simpler: everyone already knows it, and the stock price reflects it.

Citi trades below tangible book value—investor shorthand for, “we don’t believe this company can earn what its assets should be capable of earning.” If Fraser’s program produces even a modest, durable improvement—higher returns, fewer self-inflicted control failures, and a credible path to getting out from under the consent orders—Citi doesn’t need to become the best bank in America for the equity to re-rate. It just needs to stop being the perennial exception.

The heart of the bull argument is the institutional franchise. Citi’s transaction banking business—payments, cash management, liquidity, cross-border rails for multinationals—has real embeddedness. For large global companies, the winner isn’t the bank with the flashiest app; it’s the bank that can move money safely and predictably across currencies, jurisdictions, and time zones. That network took decades to build, and it’s not something a competitor can replicate quickly.

The consumer exits fit the same logic. They’re painful, slow, and sometimes politically messy, but they’re also a form of discipline Citi hasn’t always shown: walking away from subscale businesses that don’t earn their keep. If simplification reduces cost and reduces operational risk, it can improve returns even without heroic growth.

There’s also a plausible wealth management story. Citi already sits on relationships with many of the world’s most complex clients—executives, entrepreneurs, multigenerational families, institutions operating across borders. If Citi can turn those relationships into a more scaled, more consistent wealth platform, that’s the kind of fee-based revenue mix the market tends to reward.

And then there’s capital. Citi still has the capacity to generate substantial capital organically. If and when the regulatory constraints lift, that capital can turn into dividends and buybacks. For a stock that’s spent years being valued skeptically, the ability to return capital at scale can become the catalyst that forces a re-evaluation.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors following Citigroup, three things matter more than the rest:

First, return on tangible common equity. The question is whether Citi can earn above its cost of capital on a sustained basis, not just in a good quarter. Think low double digits as the minimum for “credible,” and something comfortably above that as evidence the transformation is actually working.

Second, progress on regulatory consent orders. Closures matter. Reduced scrutiny matters. Any signal that regulators see the controls as reliable—not improving, reliable—matters. Until then, Citi is running with a governor on.

Third, execution on the consumer banking exits. The goal isn’t just to announce exits; it’s to close them cleanly, at reasonable valuations, without operational disruption or unpleasant surprises. In Citi’s world, execution is the strategy.

XII. Epilogue & "What Might Have Been"

History gets written by winners. Finance gets picked apart by survivors. Citigroup survived—and that fact alone invites the most dangerous kind of question: what if one or two decisions had gone the other way?

What if Glass-Steagall had never been repealed? In that world, the 1998 Citicorp-Travelers merger wouldn’t have been able to become permanent. Either it gets unwound, or it never closes in the first place. Citicorp stays a global commercial bank. Travelers stays a securities-and-insurance conglomerate. The particular kind of too-big-to-fail complexity that came from welding them together never forms.

The 2008 crisis still might have happened—the housing bubble wasn’t “caused” by Citigroup—but the blast pattern likely looks different. The transmission mechanism changes. The concentration of risk changes. And the scale of the rescue, at least for Citi, may have been smaller.

What if John Reed had won the power struggle? Reed was a builder: systems, technology, operational discipline. Less empire, more machine. A Reed-led Citi likely would have looked smaller and more focused, and it’s hard to imagine it leaning as hard into the structured-products surge that flourished after Weill consolidated power. Would it have outperformed? No one can know. But it almost certainly would have been a different kind of institution—one whose identity was closer to “banking as infrastructure” than “banking as a supermarket of everything.”

And then there’s the darkest counterfactual: what if Citigroup had been allowed to fail in 2008?

An uncontrolled Citi bankruptcy doesn’t just erase shareholders. It threatens the wiring of the global system: counterparties suddenly unsure which trades will settle, depositors panicking about access to funds, institutions around the world losing a critical channel for dollar clearing and cross-border payments. The cascade could have been catastrophic—potentially a full-system collapse, with consequences that might have rivaled or exceeded the Great Depression.

So the bailout wasn’t an obviously wrong choice. But it did something profound. It reinforced a template the world had been sliding toward: some institutions are so large, so interconnected, and so embedded in the everyday functioning of finance that the government can’t credibly let them fail. And that reality—whether you call it a backstop or a guarantee—creates moral hazard and concentrates power. It also keeps the breakup argument alive. Should Citi be shrunk? Split up? Regulated even more heavily? That debate has never really ended.

What does feel clear is that the Citigroup we see today—smaller than its Weill-era peak, more focused than the original financial-supermarket dream, and still paying for decisions made decades ago—stands as a verdict on a particular vision of modern finance. The universal bank promised synergies that didn’t materialize, returns that rarely arrived, and stability that proved far more fragile than advertised.

Jane Fraser’s project is, in that sense, not just a turnaround plan. It’s a quiet reversal of the big bet. The financial supermarket is being dismantled. The sprawling global consumer footprint is being abandoned. What remains is a narrower institution—still huge, still complicated, but no longer pretending it can be everything to everyone, everywhere.

Whether that narrower Citi can finally deliver for shareholders is still the open question. Skepticism is rational; Citi has earned it over decades. But the strategy is clearer than it’s been in a long time, the leadership is more explicit about tradeoffs, and the work—slow, expensive, and unglamorous—is at least pointed in one direction.

Citigroup’s story isn’t over. For a two-century-old institution, it may never be. But the next chapter will be written by different characters, with different ambitions, under a different regulatory regime and a different competitive landscape. Whether it reads as redemption or another cycle of reinvention is what keeps Citi, even now, one of the most fascinating—and frustrating—companies in American finance.

XIII. Recent News

In its most recent quarterly update, Citigroup pointed to steady progress on Jane Fraser’s transformation plan. The story looked familiar by now: the institutional side of the house held up well, the unwind of far-flung consumer businesses kept moving, and management reiterated its medium-term return-on-tangible-common-equity goals. But Citi also acknowledged the condition attached to every promise it makes these days: hitting those targets still depends on finishing the operational fixes demanded by regulators.

That regulatory work remains front and center. Citi has said its conversations with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Reserve are ongoing and intensive, with both agencies closely tracking remediation milestones. The bank expects to keep spending heavily on technology modernization, data infrastructure, and risk and control upgrades through 2026 and beyond—work that is necessary, but that also competes with the faster, more visible payoffs investors usually want.

Strategically, the company has continued to close or advance additional consumer banking exits in recent quarters, while putting more emphasis on wealth management and the institutional franchise. And in the background, Citi’s transaction banking engine has gotten a lift from higher interest rates and steady demand for cross-border payments—exactly the kind of “Citi is differentiated here” business Fraser wants to build around.

XIV. Links & References

Company Filings - Citigroup Inc. Annual Reports (Form 10-K) - Citigroup Inc. Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q) - Citigroup Inc. Proxy Statements (Form DEF 14A) - Federal Reserve stress test results

Books and Long-Form Resources - The House of Morgan by Ron Chernow — essential context on American banking history - Too Big to Fail by Andrew Ross Sorkin — a definitive account of the 2008 financial crisis - Tearing Down the Walls by Monica Langley — Sandy Weill and the dealmaking that created Citigroup - The End of Wall Street by Roger Lowenstein — a crisis narrative with substantial Citigroup material

Regulatory Documents - Congressional Oversight Panel reports on TARP - Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission report - OCC and Federal Reserve consent orders (publicly available through regulator websites)

Academic Resources - Too Big to Fail: The Hazards of Bank Bailouts by Gary Stern and Ron Feldman - Federal Reserve Bank research papers on systemically important financial institutions - NBER working papers on the 2008 financial crisis and bank resolution

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music