Cognizant Technology Solutions: From D&B Spinoff to Global IT Services Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

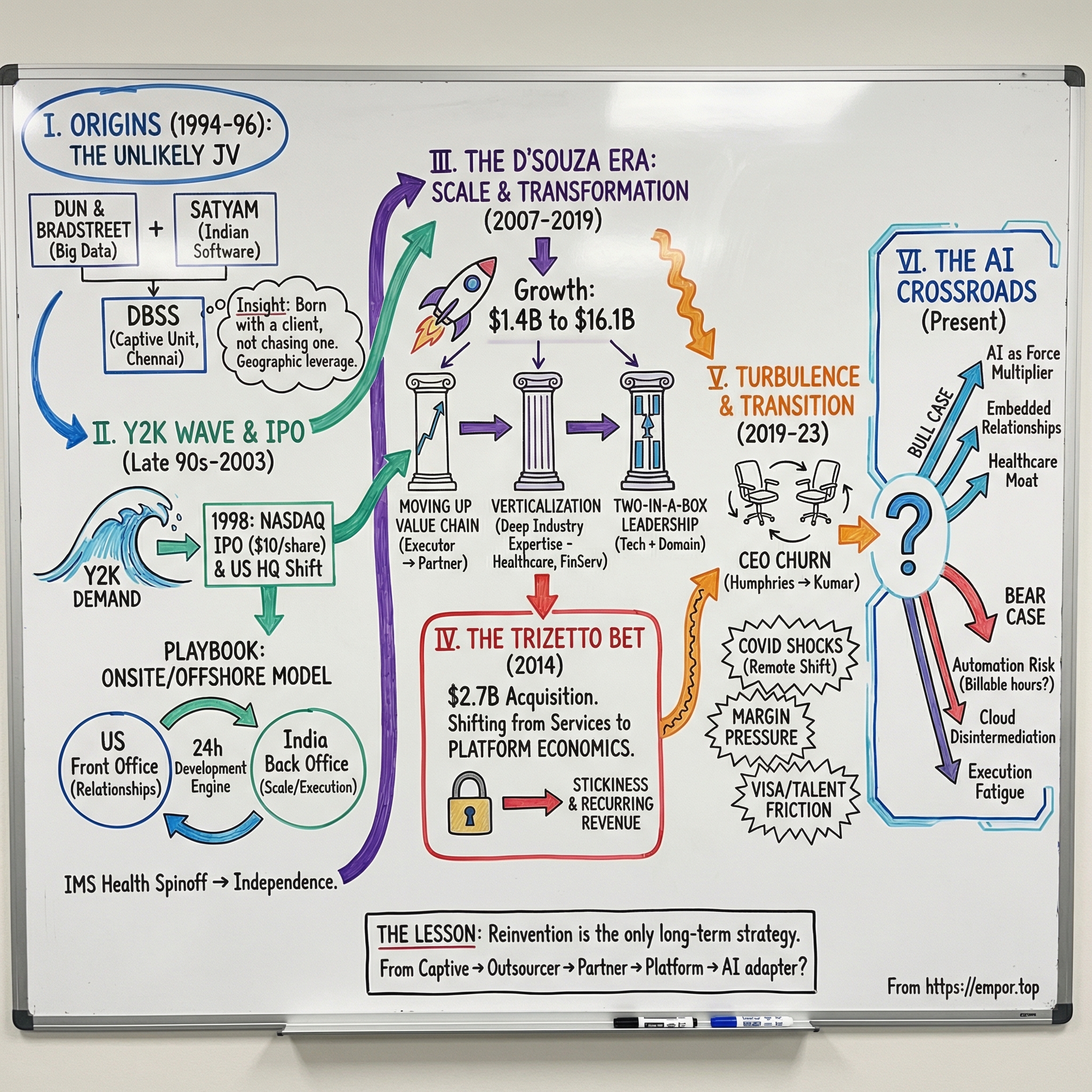

Picture this: it’s 1994 in Chennai, India. A new joint venture is coming to life between an American data heavyweight and an ambitious Indian software company. It looks like a small, practical operation—just an in-house tech team built to serve its parent. Nothing about it screams “global giant.”

And yet, that’s exactly what it became.

Today, Cognizant sits in the NASDAQ-100 under the ticker CTSH. In 2023, it brought in $19.4 billion in revenue. It operates across the world’s major regions, building and running critical systems for some of the biggest organizations in healthcare, financial services, retail, and manufacturing. Its workforce has grown to nearly 348,000 professionals, with delivery centers stretching from India to Eastern Europe to Latin America.

So how does that happen?

How does a captive IT unit—basically a back-office technology shop—turn into one of the largest IT services companies on the planet? How does a business that began life as “Dun & Bradstreet Satyam Software” end up a Fortune 500-scale force, competing with names like TCS, Infosys, and Wipro?

That’s the story we’re telling here. A story about timing and execution—catching the Y2K wave at the perfect moment, and then riding the next waves: the internet boom, enterprise globalization, and digital transformation. A story about turning a 12-hour time difference into an operating advantage, building a machine that could deliver work around the clock. And a story about reinvention: big bets, major acquisitions, leadership transitions, and the constant pressure to stay relevant in an industry that never stops moving.

We’ll go from those early Chennai days through the dot-com era, into the TriZetto acquisition that reshaped Cognizant’s healthcare business, through the Francisco D’Souza years that helped create extraordinary value, and into the modern period—defined by remote work, AI, and CEO turnover. Along the way, we’ll pull out the lessons: what worked, what broke, and what this company’s trajectory teaches founders and investors about building and scaling a services business.

Because Cognizant doesn’t just have a company story. It’s a living timeline of the global IT services industry itself—from scrappy offshore beginnings to today’s crossroads with artificial intelligence.

II. Origins & Founding Context (1994-1996)

Chennai in 1994 wasn’t yet the buzzing tech hub it would later become. The city still went by its colonial name, Madras. Engineering talent was plentiful, but the infrastructure to “ship” that talent to the world was anything but. International phone calls were expensive. Always-on connectivity wasn’t a given. The modern idea of a globally distributed software team still felt far off.

And yet, this is where Cognizant’s story starts.

It began with an unlikely pairing of two very different companies. On one side was Dun & Bradstreet, the American business information institution founded back in 1841. D&B ran on data—huge volumes of it—and that meant constant, growing internal demand for serious technology: systems to collect, store, process, and deliver commercial information at scale.

On the other side was Satyam Computer Services, founded in 1987 by entrepreneur Ramalinga Raju. Satyam was part of the rising wave of Indian software services firms, hungry for credibility and eager to show that Indian engineers could deliver enterprise-grade work.

In 1994, they formed a joint venture: Dun & Bradstreet Satyam Software, better known as DBSS. D&B owned 76%, Satyam 24%—a structure that left no ambiguity about control, while still tapping Satyam for local talent and operational know-how. The venture was led by Kumar Mahadeva and Srini Raju, with Mahadeva as CEO and Raju as Managing Director.

DBSS stood out immediately for one simple reason: it wasn’t built to chase customers. It was built with one already in hand.

Unlike Infosys or Wipro, which were out pitching external clients, DBSS started life as a captive unit—an in-house technology arm with a guaranteed buyer: its parent company. That meant stability, a clear backlog of work, and time to build muscle without the constant threat of “no deal, no company.” Early on, the mission was straightforward: develop and maintain technology systems for D&B’s global operations.

The broader backdrop mattered, too. India’s IT services scene in the mid-1990s was young but accelerating. The 1991 liberalization reforms had opened the economy, and a growing pipeline of technical graduates was ready to enter the workforce. The cost gap was enormous: a software engineer in India might earn around $15,000 a year versus $75,000 or more in the U.S. For American companies feeling crushed by technology budgets, the logic was hard to ignore.

But the founders weren’t just selling cost savings. They understood something more structural: geography could be turned into operating leverage.

The twelve-hour time difference between India and the United States, usually treated as a coordination headache, could become a feature. Work could be handed off from the U.S. at the end of the business day, picked up in Chennai, and returned by the next American morning. That “follow-the-sun” rhythm created a kind of 24-hour development engine—shorter cycles, faster delivery, and a level of responsiveness that felt almost magical at the time.

By 1996, D&B moved to reorganize its technology assets and created Cognizant Corporation as a holding company for technology-focused businesses. A few months later, in early 1997, DBSS was renamed Cognizant Technology Solutions—taking on the name that would eventually become a global brand. This was the beginning of the shift from “internal IT team” to a company that could sell technology services beyond its parent.

The key insight in this founding story is that Cognizant didn’t start like a typical startup. There was no garage, no consumer product, no viral growth loop. It was incubated inside a Fortune 500 environment, with access to enterprise expectations, mature processes, and resources most new companies never touch. That parentage was a huge advantage early on—and it also created a dependency the company would spend years working to outgrow.

III. Early Years & IPO (1996-2003)

The late 1990s handed the global IT services industry a once-in-a-generation tailwind: Y2K.

As the millennium approached, companies realized an uncomfortable truth. For decades, software had stored years as two digits—“99” instead of “1999.” If systems read “00” as 1900, everything from bank ledgers to billing systems could misbehave in ways no one wanted to discover on January 1.

The most dramatic predictions were probably exaggerated. But the corporate response wasn’t. Businesses around the world launched massive remediation programs, and they needed sheer volume: programmers who could dig through old code, spot anything date-related, and fix it fast. Indian IT services firms were perfectly positioned for that kind of work—skilled talent, scalable teams, and economics that made large projects feasible.

Cognizant leaned in at exactly the right moment.

In March 1998, Kumar Mahadeva was formally named CEO of Cognizant Technology Solutions, and the company made a defining move: it shifted its headquarters to the United States. That wasn’t just a paperwork change. It was positioning. Cognizant wanted to show up to Fortune 500 customers as an American company with world-class delivery in India—not as a distant outsourcer asking clients to take a leap of faith.

Then came the next big step. On June 19, 1998, Cognizant went public on the NASDAQ. The stock opened at $10 a share. It was a relatively modest debut, but the timing was superb: demand for Y2K and early web work was exploding, and the IPO gave Cognizant capital and credibility right when both mattered most.

Behind the scenes, the corporate family tree was still complicated. Later in 1998, Cognizant Corporation—the holding company D&B had created—was broken apart, with assets split into IMS Health and Nielsen Media Research. Cognizant Technology Solutions ended up as a publicly traded subsidiary of IMS Health. It was still tethered to its origin story, even as it worked to become something bigger than a corporate offshoot.

Operationally, these years were when Cognizant sharpened the playbook it would become known for: the onsite/offshore model. Client-facing teams stayed close to customers in the U.S., gathering requirements and managing relationships. The heavy lifting—development, testing, maintenance—ran through India, where Cognizant could scale quickly and deliver at a fraction of U.S. costs.

Making that model work took more than cheap labor. It took discipline. Teams had to coordinate across time zones, hand off work cleanly, and keep quality high as projects grew larger and more complex. When it worked, it felt like a cheat code to clients: local responsiveness with offshore economics, delivered in a rhythm that could run nearly around the clock.

By 2002, Cognizant had reached $229 million in revenue. Not huge yet—but clearly no longer a small captive shop. Even more telling was the financial footing: the company had no debt and about $100 million in cash. It had built flexibility and staying power, not just growth.

In 2003, Cognizant hit a leadership and identity inflection point. Mahadeva stepped down as CEO and was succeeded by Lakshmi Narayanan, an executive who had played a major role in scaling the delivery engine. That same year, Cognizant became fully independent from IMS Health—finally cutting the last major cord to the corporate structures that had shaped its earliest years.

This era established the template Cognizant would keep iterating on: win credibility in the U.S., deliver at scale from India, and ride the technology waves as they arrived. Y2K provided the shove. Cognizant’s operating model turned that shove into momentum.

And that $10 IPO price? It was only the beginning.

IV. The Francisco D'Souza Era: Transformation & Scale (2007-2019)

When Francisco D'Souza took over as CEO in 2007, succeeding Lakshmi Narayanan, Cognizant was already on solid footing. Revenue had climbed from $229 million in 2002 to $1.42 billion in 2006. It had made it through the dot-com bust, established itself as a top-tier IT services provider, and built a reputation for doing what it said it would do. But D'Souza’s real achievement was turning “successful” into something much bigger—and much harder to replicate.

He was also, in many ways, built for the job. Born in Nairobi to Indian parents and educated in the United States, D'Souza mirrored Cognizant’s own identity: global by nature, but fluent in the American enterprise world where the biggest customers lived. He’d joined in 1994, the founding year, and moved up through the company—meaning he didn’t just inherit the onsite/offshore machine. He understood every lever inside it. People who worked with him often pointed to the same trait: he could go from a deep discussion on technology with engineers to a strategic conversation with Fortune 500 executives without missing a beat.

Over twelve years, the results were dramatic. Revenue grew from $1.42 billion in 2006 to $16.1 billion in 2018. Headcount expanded from 39,000 to 282,000. Cognizant landed on Fortune’s Most Admired Companies list for eleven consecutive years. And the market value increase since the 1998 IPO was staggering—more than 400x.

But the story of the D'Souza era isn’t just a set of charts trending up and to the right. It’s what changed inside the business.

When he became CEO, Cognizant was still largely defined by sophisticated outsourcing. Companies hired it to build and maintain software for less than they could do internally. It was effective—and it was vulnerable. As more competitors piled into the same model and wages rose in India, the pure labor-arbitrage edge started to fade. If Cognizant stayed only a vendor, it would eventually get priced like one.

D'Souza pushed the company up the value chain: from executor to partner. Not just “tell us what to build,” but “help us figure out what to build, and how to run our business differently because of technology.” That meant investing in capabilities tied to where enterprise IT was heading—cloud computing, mobile, analytics, artificial intelligence—and combining them with something services firms often struggle to scale: real industry depth.

That’s where the vertical strategy became a centerpiece. Cognizant organized around industries and built specialized units for them. Healthcare became a major focus and eventually represented roughly a quarter of revenue. Financial services became another pillar, spanning banking, insurance, and capital markets. Retail, manufacturing, and communications rounded out the mix.

And it wasn’t marketing fluff. Each vertical stocked domain experts and built industry-specific tools and solutions. A bank client wasn’t dealing with a generic IT team—they were talking to people who understood regulations, legacy core systems, and the specific realities of digitizing a bank without breaking it. That kind of credibility made relationships stickier and helped Cognizant earn better economics than commodity outsourcing work.

Geographic expansion followed the same logic. Cognizant broadened its delivery footprint beyond India into Eastern Europe, Latin America, and increasingly into client countries themselves. As political sentiment periodically turned against offshore outsourcing, “we can deliver locally, too” became more than a nice-to-have. By 2011, Cognizant had entered the Fortune 500—an outcome that would’ve sounded absurd back when it was a captive internal unit just fifteen years earlier.

M&A also became a sharper tool during this period. Cognizant did dozens of acquisitions, from small capability tuck-ins to major moves like the TriZetto deal that would later redefine its healthcare position. The playbook was consistent: identify the missing capability, buy it, integrate it, then sell it across the rest of the client base.

Internally, D'Souza reinforced an operating culture built around pairing strengths—what he called “two-in-a-box” leadership. Technologists worked alongside industry experts. Offshore execution was paired with onsite leadership. The model wasn’t just about structure; it was about ensuring Cognizant could speak both languages: the language of business outcomes and the language of software delivery. He also invested heavily in training, because in a services company, the core asset goes home every night.

By the late 2010s, though, the environment started to shift. The cost advantage of India delivery had narrowed as wages rose. Cloud platforms from Amazon, Microsoft, and Google gave customers new options to buy technology capabilities directly, threatening to sidestep traditional services providers. Automation and AI raised an uncomfortable question: what happens to the economics of a model built on large teams if technology reduces the need for those teams?

D'Souza pushed Cognizant harder into “digital”—helping clients move to the cloud, use analytics, and automate operations. But the transition wasn’t frictionless. Growth slowed from the earlier era of 20% to 30% annual increases down to single digits. Activist investors began pressing the company, questioning strategic focus and capital allocation.

In February 2019, Cognizant announced that D'Souza would move from CEO to Executive Vice Chairman. After a remarkable run, the company was entering a different phase—one that would demand new answers to new problems.

The takeaway from the D'Souza era is simple, and it’s not just “scale matters.” Cognizant scaled because it kept redefining what it was selling. It moved from outsourced execution to industry-led partnership, and it used that shift to build deeper relationships and higher-value work. The returns since the IPO show what’s possible when strong operating discipline meets the right technology waves—and when leadership evolves the model before the market forces it to.

V. The TriZetto Acquisition: Healthcare Dominance (2014)

In September 2014, Cognizant announced the biggest acquisition in its history: it would buy TriZetto Corporation for $2.7 billion in cash. This wasn’t a routine “capability tuck-in.” It was a statement—Cognizant was serious about moving from services-only into something closer to platform economics. And it was making that bet in one of the most complicated, high-stakes industries in America: healthcare.

TriZetto wasn’t a household name, but inside healthcare IT it was a linchpin. Founded in 1997, it built the software platforms that power the unglamorous but essential plumbing of U.S. healthcare: claims processing, payer workflows, and the data exchanges that keep money and information moving between insurers, providers, and pharmacies. More than 300,000 providers and about 245,000 pharmacies used TriZetto’s platforms. By volume, it touched more than half of all health insurance claims in the United States.

For Cognizant, the appeal was straightforward: this gave them gravity.

At the time, healthcare made up about 26% of Cognizant’s revenue—but its share of the overall mix was slipping. Cognizant was doing what services firms do best: building applications, maintaining systems, running processes. But it didn’t own the core platforms its clients depended on. TriZetto changed the equation overnight.

Together, the businesses were expected to generate roughly $3 billion in healthcare revenue, instantly making Cognizant one of the largest healthcare IT players in the country. But the bigger shift wasn’t scale—it was stickiness. Platforms create recurring revenue and real switching costs. Once a health insurer has its claims engine built around TriZetto, ripping it out isn’t a weekend project. It’s a multi-year, high-risk surgery.

The timing wasn’t accidental. The Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, was reshaping incentives across the system. Insurers were being pushed to cut administrative costs. Providers were shifting, however unevenly, away from fee-for-service toward value-based care—meaning they needed better data, better systems, and better integration. And the sheer volume of healthcare data was exploding. In that environment, platforms weren’t a nice-to-have. They were the battlefield.

Cognizant’s leadership saw a chance to place the company in the center of that transformation. Instead of being the team you hired to implement someone else’s software, Cognizant could sell its own core healthcare platforms—and then attach the services to configure, integrate, and operate them. The message to clients became sharper and more valuable: we’re not just your outsourcing partner; we’re the technology backbone you run on.

Of course, that kind of move costs real money. The deal priced TriZetto at nearly four times its roughly $700 million in annual revenue—an aggressive multiple for a services company to pay, but easier to justify for platform assets with deep entrenchment. Cognizant also projected $1.5 billion in revenue synergies over five years, largely by cross-selling: TriZetto into Cognizant’s relationships, and Cognizant’s services into TriZetto’s customer base.

Then came the hard part: integration. Product companies and services companies behave differently. TriZetto had its own culture, its own sales motion, and its own development cadence. Cognizant had to keep the product roadmap moving while teaching a massive services organization how to sell, implement, and support platform software without breaking what made TriZetto valuable in the first place.

The industry noticed. Some observers reached for a big analogy: IBM in its prime—hardware, software, and services bundled into one integrated offering. Calling Cognizant the “new IBM of healthcare IT” may have been more ambition than reality, but it captured what the company was trying to become.

In the years that followed, TriZetto largely did what Cognizant bought it to do. Healthcare stayed a major contributor, and the platforms gave Cognizant something services firms always crave: a base of recurring revenue that’s less dependent on the ups and downs of project work. Just as importantly, it proved Cognizant could execute a large, complex acquisition—and use it to reshape a vertical, not just pad out a service line.

For anyone studying services businesses, TriZetto is the instructive moment. It’s a deliberate shift from hourly billing toward platform economics, from project revenue toward something more durable. The premium price only makes sense if you believe switching costs and embedded software deserve higher multiples than labor. Cognizant proved the concept in healthcare. The open question was whether it could do the same anywhere else.

VI. Leadership Transitions & Modern Challenges (2019-Present)

Francisco D’Souza’s handoff was meant to be a reset: new energy, new perspective, and a clearer answer to where IT services was headed next.

In February 2019, Cognizant announced that Brian Humphries would take over as CEO on April 1. D’Souza would move to Executive Vice Chairman. Humphries wasn’t a homegrown services executive. He came from Vodafone Business, where he’d run the enterprise arm of a European telecom giant. The bet was simple: someone who’d lived digital transformation from the buyer’s side could help Cognizant evolve from “great outsourcer” into “modern transformation partner.”

He arrived at a tricky moment. Growth had already slowed to single digits after years of breakneck expansion. Activist investors were pushing for tighter execution and better returns. And the classic offshore model was getting squeezed from all angles: rising wages in India, tougher H-1B visa dynamics in the U.S., and automation tools that promised to do more work with fewer people.

Then the world changed.

COVID-19 hit in 2020 and stress-tested every assumption in the services business. The old rhythm—teams onsite with clients, coordinating with offshore delivery centers—suddenly wasn’t possible. But the pandemic also created an urgent new wave of demand. Companies had to stand up remote work, modernize creaky systems, expand e-commerce, and digitize customer interactions far faster than any “normal” roadmap would’ve allowed.

Cognizant handled the initial shock capably. It proved it could deliver at scale while everyone was remote. And demand surged in exactly the places you’d expect: healthcare clients racing to expand telehealth, retailers upgrading online capabilities, financial services firms pushing more interactions into digital channels.

Even so, the deeper issues didn’t disappear. Growth stayed modest compared to some peers. And Cognizant struggled with a classic problem for large services firms: differentiation. The company had real strengths—strong client relationships and deep domain expertise—but telling a crisp story about why Cognizant over TCS, Infosys, Wipro, or Accenture remained difficult in a market where everyone promised “digital.”

The H-1B environment added another layer of friction. For decades, IT services companies had relied on the visa program to bring skilled workers from India to U.S. client sites. Political pressure to restrict immigration—sharpening during the Trump administration and continuing afterward—put that model under strain. Cognizant responded by hiring more in the U.S. and emphasizing local delivery, but that shift took time and raised costs.

By early 2023, the board decided it had seen enough. In January, Cognizant removed Humphries and named Ravi Kumar S. as CEO. The change came with little warning and signaled frustration with execution and performance. Kumar arrived with the one thing Humphries couldn’t bring: deep, lived experience in IT services. He had been President at Infosys, one of Cognizant’s most direct competitors.

His mandate was straightforward, and unforgiving. Reignite growth. Improve efficiency as margins compressed. And position Cognizant for what suddenly looked like the next platform shift in enterprise technology: generative AI.

That last one is the looming question. A huge portion of traditional IT services is human effort—writing code, testing, maintaining systems, running operations. If AI meaningfully automates that work, what happens to a company built around a workforce of nearly 350,000 people? In the optimistic version, AI becomes a force multiplier: the same teams deliver more value, faster, and at higher margins. In the pessimistic version, clients simply need fewer billable hours—putting pressure on the core economics.

Cognizant’s response has been to invest in AI capabilities and package offerings that help clients adopt AI in real environments. The company’s argument is that AI implementation won’t be plug-and-play; it will require industry context, systems integration, and change management—exactly the kind of work Cognizant knows how to do. Whether the market rewards that positioning is still an open question.

Financially, the business has at least steadied. Cognizant posted $19.4 billion in revenue in 2023 and remained profitable despite margin pressure. The leadership team has framed its direction around fewer, deeper client relationships and faster investment in next-generation capabilities.

But for anyone watching from the outside—especially investors—the leadership churn is hard to ignore. Three CEOs in under a decade suggests a board willing to act when it’s unhappy, and a company still searching for the clearest version of itself. Whether Ravi Kumar can deliver a true turnaround while navigating the AI transition will decide what Cognizant becomes in its next chapter.

VII. Business Model & Competitive Dynamics

To understand Cognizant, you have to understand the basic math of IT services. For decades, the industry ran on a simple idea: the same kind of engineering talent cost far less in India than it did in the United States. If you could reliably deliver enterprise-grade work from India to American clients, the gap between those labor costs—and what clients were willing to pay—created a lot of value.

Cognizant built its engine around that idea, and then refined it into a system: the onsite/offshore delivery model.

Here’s the reality Cognizant designed for: not all technology work can happen remotely. Someone still needs to sit with the client, translate business needs into technical requirements, manage relationships, and handle sensitive coordination. Those “onsite” roles cost more and bill at higher rates, which naturally eats into the labor advantage. But if you can keep the onsite team lean and push the bulk of development, testing, and maintenance to India, the economics can still be extremely attractive.

The catch is that this only works if coordination is airtight. A typical engagement might have a small group in New York embedded with executives, a project leadership layer split between the U.S. and Chennai, and a much larger delivery team in India. For the client, it’s supposed to feel like one team. For Cognizant, it requires constant attention to communication, quality control, and clean handoffs across roughly a dozen time zones and major cultural differences. When it works, the client gets speed and scale without feeling like they’re managing a faraway factory.

As Cognizant grew, it also made a structural choice that shaped how it sold and delivered: it organized the company on two axes at once—verticals and horizontals.

The verticals were industry groups: Banking and Financial Services, Insurance, Healthcare, Manufacturing, Retail, and Communications. The point wasn’t just to have a sales team with a specialized pitch. It was to build real domain knowledge into delivery. Healthcare teams learned the rules and realities of the industry, including HIPAA and electronic health records. Banking teams learned the complexity of core banking systems and the compliance environment that makes change both risky and slow.

The horizontals cut across every industry and focused on specific capabilities: analytics, mobile computing, business process outsourcing, testing, cloud services. So a retailer might hire Cognizant through the Retail vertical, but also pull in analytics specialists for demand forecasting or personalization. The model was designed to let Cognizant show up as both “we understand your world” and “we have the specialists to execute.”

This matrix created a powerful flywheel: once Cognizant was in the door—maybe doing application maintenance for a large bank—it had a clear path to expand into testing, analytics, cloud work, and eventually bigger transformation programs. The goal wasn’t to win one project. It was to become embedded in how the client operated.

That’s also why competition in this market is so unforgiving.

On one side are the Indian majors—TCS, Infosys, and Wipro—fighting on the same terrain: price, reliability, talent scale, and vertical expertise. TCS has sheer size and the Tata Group behind it. Infosys has long leaned into a reputation for innovation and leadership. Wipro competes aggressively across regions and service lines.

On the other side are the global consultancies and incumbents—Accenture, IBM Global Services, Deloitte, Capgemini—often pitching at higher price points with heavier emphasis on strategy and advisory, paired with implementation. In a head-to-head with Accenture, for example, a client might see Accenture as the premium transformation architect, while Cognizant is positioned as the partner that can implement at enormous scale with tighter economics.

Put those together and you get constant pricing pressure. When multiple vendors can credibly deliver similar work, clients push for better value. That drift toward commoditization is the permanent existential challenge of services businesses: if you’re selling hours of skilled labor, what makes you meaningfully different?

Cognizant’s answer—like the best answers in the industry—has been to keep moving up the stack. Less “we’ll staff your project” and more “we’ll own the outcome.” It’s why the company has pushed hard on industry expertise, transformation programs, and platform leverage. TriZetto was a clean example of that strategy: software platforms that create switching costs and recurring revenue, with services wrapped around them to implement, integrate, and run the systems.

This is the shift from staff augmentation to transformation partner. In staff augmentation, the client defines the work and the vendor supplies the people. In the transformation model, the vendor is on the hook for results—redesigning processes, implementing new systems, and driving measurable improvement. The upside is better economics and stickier relationships. The downside is that it requires deeper expertise, more trust, and a willingness to take on more risk.

From an investor’s perspective, the competitive position comes down to a few practical realities. Cognizant’s client base is diversified enough that no single customer defines the business, and large-enterprise relationships tend to be durable once established. Its healthcare depth, strengthened by TriZetto, gives it real differentiation in that vertical. And its global delivery footprint gives it options as labor markets tighten and politics shift.

But the question hovering over all of it is the same one facing the whole industry: can Cognizant keep evolving from labor-driven outsourcing into true value-based partnership?

Because if AI automates more of the work that used to require armies of developers and testers, then the old engine—the one built on scale and billable effort—gets challenged at the core. The companies that win won’t just be the ones with the most people. They’ll be the ones that can translate technology into outcomes, and do it in a way that clients can’t easily replace.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

If you zoom out, Cognizant’s first three decades read like a playbook for scaling a services business—especially one where the “product” is human talent. And while the details are specific to IT, the underlying lessons travel well.

First: timing isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the whole game.

Cognizant was born right as offshore software development was becoming viable. Then Y2K hit just as the company was ready to take on large volumes of work, and that surge helped turn a promising model into a real engine. After that, the industry kept offering new waves—web development, enterprise implementation, digital transformation, cloud migration. The companies that win in services aren’t only the ones that execute. They’re the ones that position themselves so that when the next wave arrives, they’re already in the water.

Second: M&A works best when it’s about capability, not size.

Cognizant’s acquisition strategy matured over time. Early on, it was smaller tuck-ins to add skills or deepen offerings. Later came big, defining moves like TriZetto—less about buying revenue and more about changing what Cognizant could credibly sell. But acquisitions in services are a special kind of hard. The value you buy is often people, and people can leave. Integration has to protect talent, preserve client relationships, and still create a combined go-to-market that makes the deal worth doing. Cognizant largely pulled that off, even if it wasn’t always seamless.

Third: leadership transitions are a core competency, not an HR task.

Cognizant moved from its founding leaders—Kumar Mahadeva and Srini Raju—through Lakshmi Narayanan, then into the Francisco D’Souza era, and eventually to the current leadership team. Every handoff risked disrupting culture, slowing execution, or drifting strategy. The fact that Cognizant navigated multiple transitions and still scaled says something important: succession planning and organizational continuity are strategic assets, especially in a business where relationships and delivery consistency are everything.

Fourth: trust is the real moat in enterprise services.

In the 1990s, many U.S. executives were skeptical of offshore outsourcing. The concerns weren’t imaginary: quality, security, and communication across time zones were real risks. Cognizant earned its way in gradually—project by project—until “offshore” stopped feeling like a gamble and started feeling like an advantage. Moving headquarters to the United States reinforced the story it wanted clients to believe: this is a company that understands American enterprise expectations, with a global delivery engine behind it.

Fifth: geography can be a superpower—until it isn’t.

Being in India in the 1990s and 2000s, as the country produced huge numbers of skilled engineers at modest wages, made the entire model work. But Cognizant also had to recognize when that single-center footprint wasn’t enough. Expanding delivery into other regions as conditions changed wasn’t just operational—it was strategic flexibility in response to cost shifts, client demands, and political realities.

Sixth: capital allocation should evolve as the business evolves.

Early on, the right move was to reinvest—build delivery capacity, hire aggressively, and establish credibility with large clients. Over time, as the company matured and cash generation became more predictable, it made sense to balance growth investment with returning capital to shareholders through dividends and buybacks. The early zero-debt posture mattered, too: it gave Cognizant resilience and optionality when opportunities—or shocks—arrived.

Seventh: talent management is the job.

Cognizant grew from a few hundred employees to nearly 350,000. At that scale, “culture” isn’t a slogan; it’s systems, training, leadership development, and the ability to maintain quality while turnover is always a threat. Sustaining employee satisfaction in IT services is notoriously difficult, but Cognizant’s long run of workplace recognition suggests it invested seriously in people—and treated that investment as foundational, not optional.

For investors, Cognizant also lays bare the trade-offs in services. The upside is attractive: a capital-light model, strong cash generation, and the ability to scale quickly when demand spikes. The downside is structural: labor intensity cuts both ways, differentiation is hard to maintain, and clients never stop pressuring price. The services businesses that endure are the ones that find ways to become more than labor arbitrage—through industry specialization, deeper client partnerships, and, when possible, platforms that create switching costs.

Which leads to the final lesson: reinvention is the only long-term strategy.

Cognizant has already reinvented itself multiple times—from captive unit to independent company, from Y2K workhorse to digital transformation partner, from pure services to services-plus-platforms. Whether it can reinvent itself again for the AI era will determine if the next thirty years look anything like the first.

IX. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

If you’re bullish on Cognizant, the argument starts with a simple observation: the world is still buying a lot of digital change. Companies across industries continue pouring money into cloud migration, data and analytics, cybersecurity, and the slow, messy modernization of legacy systems that were never designed for today’s pace. Cognizant has been selling into that environment for decades, and its core advantage is credibility with large enterprises. When a Fortune 500 company needs something mission-critical delivered at scale, Cognizant is already on the shortlist.

Healthcare is the clearest example of where that advantage becomes structural. TriZetto gives Cognizant something most services firms struggle to build: real switching costs. Healthcare IT is difficult by default—regulatory requirements, interoperability headaches, enormous data volumes, and systems that can’t afford downtime. When a major health insurer or pharmacy benefit manager runs claims processing on TriZetto, it’s not something you casually swap out. Migration can take years, consume huge budgets, and introduce real operational risk. That “pain of leaving” creates durability that pure services contracts rarely match.

Then there’s the less visible asset: relationships. Cognizant’s teams often sit deep inside a client’s operating reality. They know the systems, the workflows, the exceptions, and the political map of how decisions actually get made. That kind of embedded knowledge is hard to replicate, and expensive to replace. In enterprise IT services, winning a new large client can take a long time and cost a lot, so an installed base you can expand within is a powerful starting point.

Cost still matters, too. Even as the classic labor-arbitrage gap has narrowed, Cognizant’s blended delivery model can still come in below what traditional consultancies charge for similar work. For many buyers, especially in a tighter macro environment, “good outcomes at a better price” remains a compelling value proposition.

And finally, there’s AI—the wildcard that could either compress the business or expand it. The optimistic view is that AI doesn’t eliminate demand; it changes what clients need help with. Enterprises still have to integrate AI into messy, real-world environments, with governance, security, data pipelines, and change management. That’s not plug-and-play. Cognizant can credibly position itself as the partner that makes AI usable inside large organizations, rather than the company AI replaces.

The Bear Case

The bear case is less about whether Cognizant is a good company and more about whether the category is getting structurally harder. Margin pressure is the headline risk. Wage inflation in India keeps pushing costs up, procurement teams keep pushing prices down, and automation keeps reducing the amount of human effort required for some of the work that historically generated billable hours. That’s a squeeze from three directions at once.

Then there’s policy risk. The onsite/offshore model has always depended, at least in part, on the ability to move skilled employees to client locations. H-1B restrictions and broader political pressure against offshore outsourcing can raise costs, slow delivery, and force more hiring in higher-cost markets. Cognizant has expanded local hiring and diversified delivery locations, but a major tightening of work visas would still be a meaningful headwind.

A different threat comes from the cloud platforms themselves. AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud aren’t just infrastructure providers anymore. They’re moving up the stack with managed services, higher-level platforms, and increasingly complete “buy instead of build” solutions. That creates potential disintermediation. If a client can adopt a pre-built cloud service rather than commissioning a custom build, the services vendor risks being pulled out of the center of the value chain.

And then there’s leadership. CEO turnover doesn’t automatically mean a business is broken, but in a relationship-driven services company, stability matters. Multiple leadership changes in a relatively short period can signal strategic drift, internal friction, or inconsistent execution—all of which make it harder to hold client trust and employee morale at the same time.

Applying Strategic Frameworks

Through the lens of Porter’s Five Forces, Cognizant sits in an industry with persistent pressure. Buyer power is high: large enterprise clients are sophisticated, price-sensitive, and have plenty of credible vendor options. Supplier power is mixed: top talent matters, but the overall supply of engineers is far broader than in industries constrained by scarce physical assets. New entrants are possible, though scaling to Cognizant’s level takes time and operational maturity. The biggest shift is in substitutes: cloud platforms and AI-driven automation are increasingly real alternatives to traditional labor-based delivery.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers adds nuance. Cognizant clearly has switching costs in pockets—TriZetto and long-running enterprise integrations create meaningful friction for customers who might otherwise switch vendors. There’s also an argument for a network effect around TriZetto’s ecosystem, since healthcare platforms often become more valuable as they connect more parties. Scale helps, but only to a point; services don’t enjoy the same “winner-take-most” economics as software because people don’t scale like code. The rest of Helmer’s powers—counter-positioning, cornered resource, process power, and brand—show up unevenly. Cognizant has strengths, but not an unassailable fortress across the entire portfolio.

Key Performance Indicators

If you want to track whether Cognizant is winning or merely maintaining, a few signals matter more than headline revenue.

Revenue growth by segment shows where the engine is working and where it’s losing torque. Healthcare matters disproportionately because TriZetto was a defining bet; sustained weakness there would be a red flag.

Attrition rate is a fast read on internal health. In IT services, talent churn hits quality first and client satisfaction shortly after. Watching attrition versus peers helps indicate whether Cognizant remains a place people want to stay—and whether delivery risk is rising.

Contract signings and pipeline offer the cleanest forward indicator. Large deal momentum usually shows up in bookings before it shows up in revenue. Softness in signings is often the earliest warning that growth is about to slow.

Taken together, these are the practical scoreboard metrics. They won’t answer every strategic question, but over time they reveal whether Cognizant is executing—and whether its story is strengthening or fading.

X. Epilogue & Reflections

Cognizant’s story leaves you with one big, unavoidable question: what happens to a services giant when the “service” itself gets automated?

For three decades, the company mastered the art of organizing human talent at scale—pairing client-facing teams with massive delivery engines, turning time zones into an advantage, and turning billable effort into reliable growth. Now AI is aiming straight at the heart of that model. If machines can write code, generate tests, and handle routine maintenance, what does a company built around human hours become?

There’s a steady, optimistic interpretation. AI is just the next productivity upgrade. Spreadsheets didn’t eliminate accounting; they changed what accountants did and raised expectations for speed and accuracy. In that view, AI won’t erase IT services work—it will compress the low-end tasks and expand what “good” looks like. Cognizant’s opportunity would be to turn its workforce into AI-augmented delivery teams that can move faster, ship higher quality, and take on more ambitious transformations. The winner wouldn’t be the company with the most people. It would be the one that best equips its people.

Then there’s the more disruptive interpretation: AI doesn’t just improve productivity, it changes the demand curve. If clients can get software built, tested, and operated with far fewer humans in the loop, they won’t buy the same volume of services. That’s not margin pressure—that’s a business model reset. In that world, Cognizant would need to lean harder into being something other than a labor engine: more platform, more IP, more outcome-based delivery, more recurring revenue. Less “we’ll staff the work,” more “we’ll own the system.”

Even geography—the old advantage—still matters. India will likely remain the center of gravity, but the logic of a distributed network hasn’t gone away. Latin America brings closer time zones for North American clients. Eastern Europe brings proximity to European markets. The companies that can flex where work gets done—based on regulation, client preference, cost, and risk—will have more options when the ground shifts.

And that brings us back to the platform-versus-services debate. TriZetto was Cognizant’s clearest proof that owning a platform can create durability that hourly work rarely does. The question is whether that move was a one-off, or a template. Replicating it in other verticals—financial services, manufacturing, retail—could reshape the company’s long-term economics. But it’s not a simple copy-paste. Building and running platforms is a different sport from delivering projects, and it demands different muscles: product roadmaps, ecosystem thinking, and long-term R&D discipline.

Looking back, what’s most surprising about Cognizant is how much hinged on a handful of early choices. Positioning itself as U.S.-centric while building in India. Relentlessly reinvesting to build capability. Taking a bold swing with TriZetto instead of staying purely in services. Those decisions didn’t just improve the business—they expanded what the business could be.

For founders, Cognizant is both inspiration and warning. Inspiration, because it’s proof that services can scale to extraordinary heights. An internal IT unit with no consumer brand and no breakout product still became a Fortune 500 force. Warning, because it only worked through constant reinvention. In this industry, standing still isn’t stability—it’s slow motion decline.

The deeper takeaway is simple: a services company is only as valuable as its relevance to what clients need next. Client expectations evolve. Technology platforms shift. Delivery models get rewritten. The companies that keep earning trust while continuously upgrading what they sell can last for decades. The ones that cling to yesterday’s playbook eventually become footnotes.

Cognizant’s next chapter is still being written. Whether it navigates the AI era as effectively as it navigated Y2K, the dot-com bust, the global financial crisis, and the pandemic will determine what kind of story this becomes: another reinvention worth studying, or a reminder that even giants can get caught flat-footed.

XI. Recent News

In January 2023, Cognizant showed it was willing to make a hard call at the top. CEO Brian Humphries departed, and Ravi Kumar S.—formerly President of Infosys—was brought in to take the helm. The move read as a clear signal from the board: Cognizant needed sharper execution, a tighter story in the market, and a faster path back to stronger growth.

From there, the narrative shifted quickly to the next big technology wave. Through 2023 and into 2024, Cognizant leaned heavily into generative AI, rolling out partnerships and building internal tools aimed at helping clients put AI to work in real enterprise environments. One of the headline efforts was what the company called “Cognizant Neuro AI,” positioned as a way for enterprises to adopt large language models and other generative AI technologies without treating it like a science experiment.

The financial picture reflected the broader industry slowdown. Full-year 2023 revenue came in at $19.4 billion, essentially flat versus the year before, as demand across IT services stayed choppy. Even so, Cognizant continued to return capital—maintaining its dividend and buying back shares—while still funding the capabilities it believes will matter next.

In 2024, the company stuck to a familiar M&A rhythm: smaller, targeted acquisitions designed to add digital capabilities and close specific gaps, rather than another TriZetto-sized swing. It also pushed further into key European markets and made selective investments in healthcare technology, reinforcing one of its long-standing strengths.

Recent quarters have offered some early signs of stabilization, with modest improvement in bookings and revenue trends. Management has struck a cautiously optimistic tone—encouraged by momentum, but clear-eyed about macro uncertainty. The underlying tension hasn’t gone away: Cognizant is still navigating a market defined by intense competition, shifting client priorities, and the open question of how AI reshapes the economics of services.

XII. Links & Resources

Company Filings - Cognizant Technology Solutions SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, 8-K) via the SEC’s EDGAR database - Cognizant annual reports and investor presentations on the company’s Investor Relations site

Historical Coverage - “Cognizant: The Company Everyone Underestimated” (Harvard Business School case study) - Contemporary coverage of the TriZetto acquisition in outlets like The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, and industry trade publications - Profiles of Francisco D’Souza’s leadership era in publications including Forbes and Fortune

Industry Analysis - Gartner and Forrester research on the IT services market - NASSCOM (National Association of Software and Service Companies) reports on India’s IT-BPM sector - Everest Group research on global IT services

Background Reading - The World Is Flat by Thomas L. Friedman, for broader context on the globalization of IT services - Coverage of the Y2K remediation wave in contemporary reporting from the late 1990s - Analysis of how the Affordable Care Act influenced healthcare IT investment and modernization

This story is based on public company filings, earnings-call transcripts, industry research, and contemporaneous news coverage. All financial figures are drawn from publicly disclosed sources. This is for educational purposes only and is not investment advice.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music