Chevron: From Standard Oil to Energy Supermajor

I. Cold Open & The Big Picture

Picture a boardroom in San Ramon, California, early 2023. Chevron CEO Mike Wirth is sitting across from John Hess of Hess Corporation. Two leaders, two legacy companies, both descended from the titans who built America’s oil business. On the table is a deal big enough to redraw Chevron’s future: an all-stock acquisition of Hess, priced at $53 billion.

When it finally closed in 2025—after a long, high-stakes arbitration fight with ExxonMobil over preemption rights in Guyana—the transaction landed as more than a headline number. It was Chevron’s playbook in its purest form: buy scarce, high-quality resources that can carry the company through the next cycle, and the next decade after that.

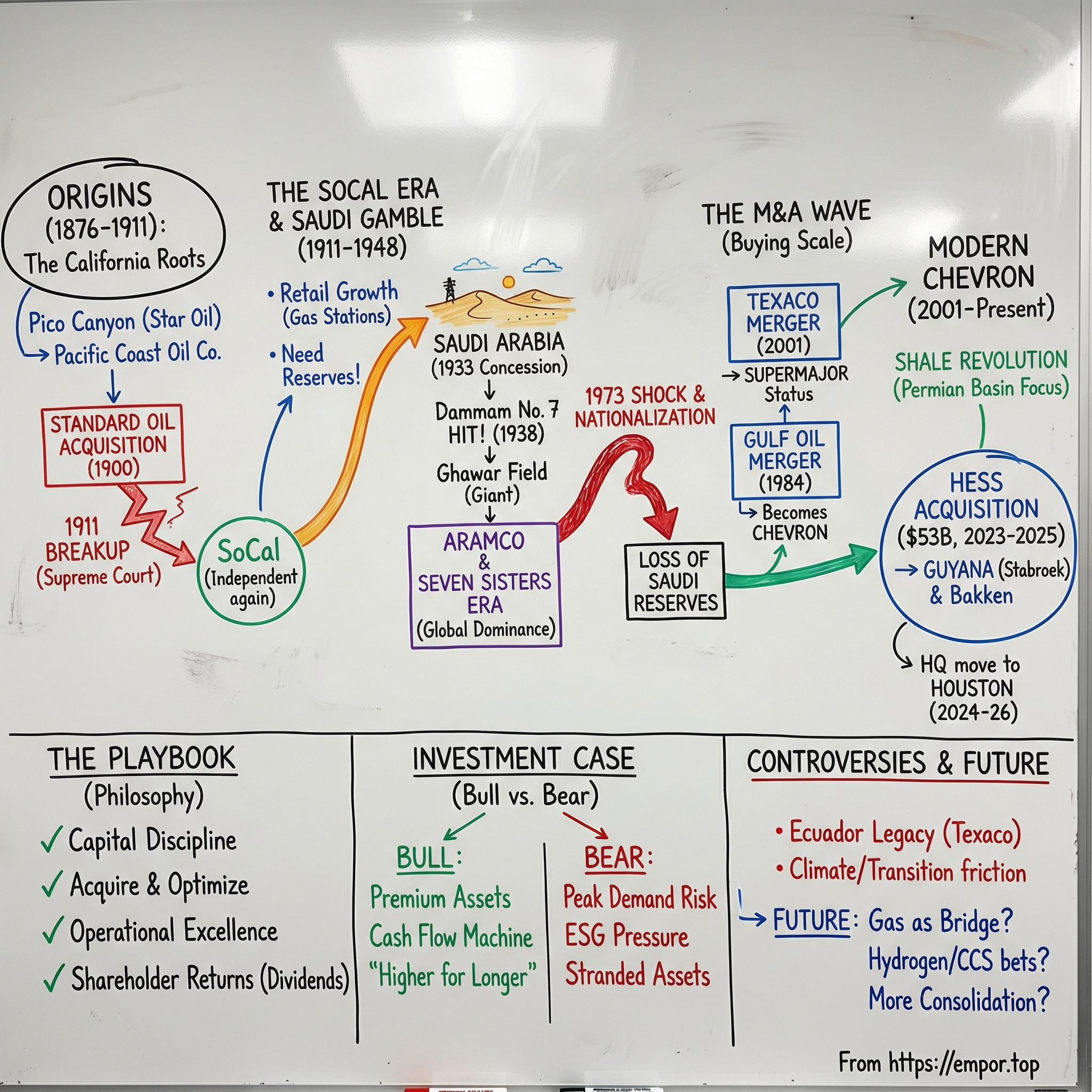

Chevron is the second-largest surviving descendant of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil empire, behind only ExxonMobil. For most of its life it wasn’t even called Chevron. It was Standard Oil of California—SoCal—and its roots run all the way back to the earliest days of oil on the American West Coast.

By 2023, Fortune ranked Chevron tenth on the Fortune 500, with annual revenue north of $200 billion. And in a small but telling bit of symbolism, Chevron remained the last oil-and-gas company in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, a spot it has held since 2008, when it replaced Altria Group. In an index now dominated by tech and healthcare, Chevron’s presence is a reminder that the world still runs on molecules as much as microchips.

This is a 150-year story told through reinventions: three names, dozens of major acquisitions, and a footprint that stretches across more than 180 countries. It’s California wildcatters drilling in dry canyons. It’s geologists grinding through years of failure in the Saudi desert before hitting some of the richest petroleum reserves ever found. It’s executives steering through OPEC shocks, price collapses, and courtroom battles—sometimes all at once.

To understand Chevron is to understand the modern energy era itself: from kerosene and early refineries to today’s arguments over electrification, emissions, and what comes next.

So that’s the journey. We’ll start in the aftermath of the Gold Rush, when the hunt for fortune shifted from precious metals to black gold. We’ll follow SoCal into Rockefeller’s orbit, then out again when antitrust laws shattered Standard Oil. We’ll spend time on the Saudi gamble that remade both a company and a kingdom. And we’ll track the megamergers—Gulf Oil, then Texaco—that forged the supermajor we know today, before landing back in the present, where Chevron is still making bets measured in decades, even as the world debates how quickly it can move beyond oil.

II. Origins: The Pacific Coast Oil Story (1876-1911)

California’s oil story didn’t start with a legendary gusher. It started with a middleman who’d had enough.

In 1875, Demetrius Scofield—a former Union Army officer turned kerosene dealer in San Francisco—was sick of being at the mercy of Standard Oil. Lamp fuel was being shipped all the way from Pennsylvania, around Cape Horn, and by the time it reached the West Coast, the price was punishing. The transcontinental railroad existed, but moving oil was still expensive. Scofield was convinced there had to be a better answer. Californians had known about tar seeps for years. If oil was here, someone just had to go find it.

Scofield found his way into a small network of believers through Charles Alexander Mentry, an early oil producer in Ventura County. The group included Frederick Taylor, a Philadelphia businessman who’d seen the Pennsylvania oil fields up close. Taylor would become the central figure in what eventually became Chevron.

In 1876, the Star Oil Works Company started drilling at Pico Canyon, in the hills north of Los Angeles—land where the Indigenous Tataviam people had long gathered tar from natural seepage. On September 26, 1876, a driller named Alex Mentry (no relation to Charles) hit oil with Pico Well No. 4. It was only about 300 feet deep and produced roughly 30 barrels a day. By later standards, that’s modest. For the Pacific Coast in 1876, it was proof: California wasn’t just a place with tar bubbles. It could produce commercial petroleum.

Taylor moved fast. In 1879, he rolled several small operations into a single company: the Pacific Coast Oil Company, headquartered in San Francisco. It controlled production at Pico Canyon and built out the basic machinery of an oil business—getting crude out of the ground, turning it into products, and getting those products to customers.

The refining piece mattered most. Pacific Coast Oil’s refinery at Alameda Point on San Francisco Bay—operating since 1880—helped turn local crude into kerosene for lamps, lubricants for the railroad boom, and fuel oil for coastal steamships. By the standards of the day, it was a serious West Coast enterprise.

But it was also sitting in the path of a steamroller.

Back east, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil had spent the previous two decades consolidating the American oil business—buying competitors, squeezing margins, controlling distribution, and wielding relationships with railroads and pipelines like weapons. By 1890, Standard dominated American refining and had built a national system designed to make independent rivals feel permanently outgunned. California, still distant and developing, was one of the last meaningful territories it hadn’t fully absorbed.

The fight played out across the 1890s in ways that looked familiar wherever Standard went: price wars, exclusive arrangements with retailers, and quiet stock accumulation. Pacific Coast Oil could drill and refine, but it couldn’t match Standard’s ability to starve competitors in the market and wait them out. By 1900, Frederick Taylor was aging, shareholders were worn down, and the pressure to stop bleeding in a prolonged conflict was intense. Taylor finally folded.

Standard Oil bought Pacific Coast Oil Company for about $761,000 in cash plus Standard Oil stock. For Standard, it was a bargain. For Pacific Coast Oil, it was the end of independence—and the beginning of something bigger.

The acquisition gave Standard exactly what it wanted: an integrated West Coast platform—production, pipelines, refining, and distribution—already operating at scale. In 1906, Standard reorganized the business as the Standard Oil Company (California). Because California was so far from Standard’s eastern hub, the subsidiary ran with a degree of autonomy, but it grew quickly: new fields, especially in the San Joaquin Valley, and more refining capacity to serve the West Coast and Pacific trade.

And then the whole Standard Oil machine cracked.

On May 15, 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States that the trust violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. The Court ordered Standard Oil to be broken into 34 independent companies. It was the defining antitrust action of its era—and a decision that shaped the oil industry for the next century.

Standard Oil Company (California) came out the other side not as a weak orphan, but as one of the strongest descendants. Unlike some successors that leaned heavily toward refining or marketing, SoCal had the full stack: productive California oil fields, pipelines across the state, refineries capable of making finished products, tanker ships to move them up and down the coast, and retail outlets selling directly to customers.

Just as important, SoCal carried forward a particular kind of DNA: a comfort with exploration risk, born from wildcatting in California’s geologically messy basins. That identity—integrated, operationally hands-on, and willing to hunt for new reserves far from the traditional centers of power—was set in 1911. Chevron would keep returning to it, again and again, as the industry’s center of gravity shifted around the world.

III. The SoCal Era: Building an Empire (1911-1933)

When Standard Oil of California emerged from the 1911 breakup, it inherited a rare advantage: it wasn’t just a refiner or a marketer. It had California oil in the ground, pipes to move it, refineries to turn it into products, and outlets to sell it. And it was operating in the right place at the right time. California production surged through the 1910s and 1920s as cars multiplied, industry expanded, and ships and railroads consumed more fuel. SoCal held the biggest position in the state.

But the breakup also changed the rules. No longer sheltered by Rockefeller’s scale, SoCal had to stand on its own. That meant getting bigger, faster—or risking being boxed in, or bought out, by rivals with deeper pockets.

Its first post-breakup president, William S. Rheem, set about making the company feel less like a collection of inherited assets and more like a unified machine. He standardized operations across SoCal’s California footprint, modernized the Alameda Point refinery, and—crucially—leaned into retail. Rheem could see what was coming: the automobile was going to pull oil demand away from lamps and lubricants and toward transportation. Gasoline, once treated as an annoying byproduct that refiners sometimes dumped, was becoming the main event.

In 1914, SoCal made a move that hinted at how seriously it took that future. In Seattle, Washington, the company opened what many historians consider the world’s first purpose-built automobile service station. The idea came from John McLean, SoCal’s sales manager in the Pacific Northwest, who saw the problem every driver faced: buying gasoline in cans from general stores, hardware shops, and stables—an awkward, often hazardous routine. McLean’s station changed the experience. A dedicated location. A pump. An attendant. A simple promise: pull in, fill up, move on.

That concept spread fast. By 1920, SoCal operated hundreds of branded stations across California, Oregon, and Washington. They carried the company’s red chevron emblem, a symbol that reached back to SoCal’s early California operations and would eventually lend the corporation its modern name. These stations did more than sell fuel. They put SoCal directly in front of the customer, turning a commodity into a relationship and locking in demand for the company’s refineries.

But there was a hard limit to how far retail could take you without secure crude. California was prolific, yet many of its early fields were already maturing. New barrels were still there, but they were harder won—tucked into complicated structures in the San Joaquin Valley or offshore in the Santa Barbara Channel. SoCal’s geologists and engineers kept pushing into California’s famously twisted geology, building the technical confidence that would later matter far from home.

Then, in 1926, SoCal made its biggest leap since independence. It bought the Pacific Oil Company from the Southern Pacific Railroad for about $47 million. Pacific Oil brought major production in California’s Kern River field, pipelines, and a refinery in El Segundo near Los Angeles. The deal roughly doubled SoCal’s production and handed it a refinery complex perfectly placed to supply a booming Southern California market.

The more important part sat in the fine print: Pacific Oil wasn’t only a California story. It also held producing properties and refining interests in Texas—territory shaped by the Spindletop-era boom. For the first time, SoCal had a meaningful foothold beyond the West Coast. And it revealed a pattern that would keep repeating over the next century: when the next chapter required scale or a new map, SoCal would buy its way into it.

By the late 1920s, Standard Oil of California had grown into a major American oil company. But inside the success was a looming problem. However large California seemed, it was still one state’s reservoir—and SoCal’s own geologists believed the domestic reserve base, at prevailing production rates, would run down within decades. If SoCal wanted to keep growing—or even keep steady—it would have to find oil somewhere else.

That realization set up a pivot that would define the company. Going international wasn’t just a strategy shift; it demanded a cultural one. SoCal’s veterans knew every folded ridge and fractured formation of their home basins. Abroad, they’d be starting cold—new geology, new laws, new governments, and risks that didn’t exist in Kern County or Santa Barbara. The company that had learned to win in California was about to take its biggest gamble yet.

IV. The Saudi Gamble: Discovery That Changed Everything (1933-1948)

By the late 1920s, the oil industry was staring at an uncomfortable truth. Most of the world’s proven reserves seemed to cluster in just a few places: overwhelmingly the United States, with meaningful but smaller pools in Mexico, Venezuela, and the Dutch East Indies. America could still satisfy its own demand and export the excess, but plenty of geologists were already warning that the easy domestic fields wouldn’t last forever. If you were a serious oil company planning for decades, “go abroad” wasn’t a growth strategy. It was survival.

And the biggest prize on the map was the Middle East.

The region wasn’t an empty mystery. British geologists had proven the concept in Persia in 1908, when commercial oil turned up and Anglo-Persian Oil Company—later BP—began pulling serious volumes out of the ground. After that, seep reports and rumors piled up: Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain, the Arabian Peninsula. But exploration lagged because the terrain was brutal, politics were fragmented, and Britain’s influence over much of the region made it hard for American companies to get a seat at the table.

SoCal’s opening came through a small island just off the Arabian mainland: Bahrain.

In 1928, SoCal picked up an exploration concession there from a British firm that couldn’t raise financing. The company sent in a team led by geologist Fred Davies. They drilled through thick limestone and, in 1932, hit oil—the first discovery on the Arab side of the Persian Gulf. Bahrain itself wasn’t going to remake the world. But it did two things that mattered immensely: it proved SoCal could operate in the Gulf, and it suggested the real story might be across the water on the Arabian mainland.

That mainland was Saudi Arabia, and in 1933 it was not yet the Saudi Arabia the world recognizes today.

The kingdom had only recently been unified by King Abdulaziz ibn Abdul Rahman Al Saud—better known in the West as Ibn Saud—who had spent decades fighting to bring the peninsula’s tribes under one rule. He declared the modern Saudi state in 1932. Then almost immediately he ran into a crisis: the Great Depression crushed the country’s traditional income streams. Revenues from Mecca pilgrimages fell, trade slowed, and the young kingdom’s finances tightened to the point of danger. Ibn Saud needed a new source of cash to hold his fragile state together.

Oil looked like the only plausible answer. Ibn Saud had watched petroleum wealth transform neighboring Iran, and he understood what it could do. But he also distrusted the British, whose colonial presence ringed his region. Americans, by contrast, came without the same political baggage. So when SoCal approached in early 1933, the king listened.

The bargaining was intricate and, at times, tense. SoCal sent lawyer Lloyd Hamilton to handle its side. The Saudis leaned on St. John Philby, a British Arabist who had converted to Islam and become an adviser to Ibn Saud. Competitors circled too, including the Iraq Petroleum Company—backed by BP, Shell, and American majors—making rival pitches. In the end, SoCal won with a package built around immediate cash, ongoing financial support, and royalties that would kick in if oil was found. The headline detail was memorable: 30,000 British pounds paid in gold up front, plus similar annual loans and royalty payments once production began.

On May 29, 1933, Saudi Arabia signed a 60-year concession granting SoCal exclusive rights to explore and produce oil across roughly 930,000 square kilometers of eastern Saudi Arabia—about the size of Texas and New Mexico combined. SoCal formed a new subsidiary to run the effort: the California Arabian Standard Oil Company, or CASOC.

At the time, hardly anyone noticed. The world economy was still deep in depression, and Saudi Arabia didn’t look like the kind of place that would anchor global energy supply.

On the ground, it looked even less plausible.

Eastern Saudi Arabia was largely empty desert. Summer temperatures could top 120 degrees Fahrenheit. There were no roads to speak of, no industrial base, and almost no infrastructure beyond Bedouin caravan routes. CASOC had to ship equipment from California through the Suez Canal, then build everything it needed—camps, roads, storage—from scratch. Water was scarce. Disease was common. And the nearest workable port facilities were across the Gulf in Bahrain, about 20 miles offshore.

On September 23, 1933, two geologists—Robert Miller and Schuyler Henry—arrived at the port of Jubail to begin the search. They were young, American-trained, with little field experience and no Arabic. And unlike California, where seeps and stained outcrops could point you toward a prospect, eastern Saudi Arabia gave almost nothing away on the surface. The job became a test of fundamentals: walking the land, mapping subtle folds and domes, reading gentle anticlines, and using gravity surveys to infer what might be hiding under all that sand.

Then came the long stretch that breaks most exploration stories.

For five years, CASOC drilled and came up empty. Wells that looked promising turned out dry, or water-bearing. Back in San Francisco, patience began to thin. The company had poured millions into a desert concession and had nothing to show shareholders but invoices and disappointment. By 1936, the pressure was high enough that SoCal did the sensible thing: it brought in a partner.

Texaco—SoCal’s closest major counterpart after years of cooperation—agreed to buy a 50% stake in CASOC for $21 million, along with commitments for future exploration spending. The deal brought fresh capital and, just as important, access to Texaco’s overseas marketing network—something CASOC would need if it ever found oil in quantities worth exporting.

Even with Texaco on board, the project still nearly died.

Through 1937 and into 1938, the drills kept turning up frustration. Inside CASOC, the debate turned existential. Maybe the oil-bearing formations that made Iran and Iraq so productive didn’t extend under Saudi Arabia at all. Maybe the concession was simply the wrong geology. Some argued it was time to walk away.

And then, on March 3, 1938, Dammam Well No. 7 hit.

The well had been drilled into a large dome structure that CASOC’s geologists had identified years earlier. At 4,727 feet, it struck oil—and not the kind of teasing “show” that fades. This was a sustained flow. Dammam No. 7 initially produced over 1,500 barrels per day, later rising to 3,810 barrels per day. Follow-on drilling confirmed what the team had almost stopped believing: they weren’t sitting on a small pocket. They had tapped a major accumulation beneath the sands.

For Saudi Arabia, it was the beginning of a national transformation. Ibn Saud, who had watched the effort with growing anxiety, now had access to a revenue stream that would eventually eclipse anything the kingdom had ever known. The first payments helped fund roads, schools, and the early scaffolding of a modern state. A society whose economy revolved around pilgrimage and pastoral life began shifting toward oil infrastructure, exports, and global leverage.

For SoCal, Dammam was vindication—and a new problem: how do you develop something this big, this remote, in a place with almost no industrial footprint?

The answer started arriving quickly. In 1938, CASOC identified the Abqaiq field. Then, in 1948, it found the one that changed the scale of the entire story: Ghawar, the largest conventional oil field ever discovered, with recoverable reserves exceeding 70 billion barrels.

SoCal had gone looking for the next barrel. It found a kingdom’s future—and the resource base that would carry the company into the top tier of global oil for generations.

V. Aramco & The Seven Sisters Era (1944-1973)

By 1944, CASOC had outgrown its original mission—and its original name. What started as a risky exploration outpost had become an industrial system in the desert. At Ras Tanura on the Persian Gulf, the company built a major export terminal capable of loading the largest tankers of the era. Pipelines cut across hundreds of miles of sand, linking fields to processing, refining, and shipping. A growing workforce of American engineers, geologists, and managers lived and worked alongside Saudi nationals, creating something that looked less like a remote oil camp and more like a purpose-built company community on the Arabian Peninsula.

That same year, CASOC rebranded as the Arabian American Oil Company—Aramco. The new name signaled a shift in identity: this wasn’t just a SoCal subsidiary hunting for oil anymore. It was a producing giant—and a joint venture. Texaco already owned half, and the scale of what Saudi Arabia appeared to hold meant Aramco would need even more capital, more refining capacity, and more routes to market.

Those partners arrived in 1948. SoCal and Texaco sold stakes in Aramco to Standard Oil of New Jersey (later Exxon) and Socony-Vacuum (later Mobil). The end result was roughly a four-way split, with each company holding about a quarter (the exact percentages shifted with later adjustments). The logic was simple: SoCal brought exploration know-how and the original concession, Texaco brought marketing reach, and the other Standard Oil successors brought deep pockets and major refining systems. Together, they could develop Saudi oil at a pace no single company was likely to manage alone.

Aramco’s owners also sat at the center of a new world order in oil. Journalist Anthony Sampson later dubbed the biggest global majors the “Seven Sisters”: Jersey Standard (Exxon), Socony-Vacuum (Mobil), SoCal (Chevron), Texaco, Gulf Oil, Royal Dutch Shell, and British Petroleum. Through the postwar decades, they dominated the industry—shaping production, moving crude and products through their own pipelines, tankers, and refineries, and exerting geopolitical influence that sometimes rivaled governments. Collectively, they controlled the vast majority of the world’s known oil reserves outside the United States and the Soviet Union.

For SoCal, this era delivered the kind of growth that rewrites a company’s center of gravity. Saudi production surged from the late 1940s into the early 1970s, eventually reaching more than 8 million barrels per day. Aramco kept adding to the map of giant fields, including Safaniya, the world’s largest offshore field, and Shaybah, a huge accumulation in the Empty Quarter. Compared to that, SoCal’s California business—once the whole story—started to look small. The cash flowing from its Aramco stake dwarfed what the company could generate at home.

The financial transformation showed up fast. By 1949, SoCal was one of the few American industrial companies with more than $1 billion in assets. Revenues topped $1 billion in 1951. By 1957, it was selling $1.7 billion of petroleum products a year, making it the world’s seventh-largest oil concern. The company that began with a modest California well in the 1870s was now a global heavyweight.

SoCal used its Saudi windfall to widen its U.S. footprint, too. In 1961, it bought Standard Oil Company of Kentucky, another Standard Oil descendant with a strong regional presence in the Southeast. The deal pushed SoCal’s retail reach far beyond the Pacific Coast, stretching its station network across the South and helping the Chevron brand—already established in the West—show up in a whole new part of the country.

Internationally, the company broadened its reach through Caltex, the joint venture with Texaco that built refining and marketing positions across Asia, Africa, and Australasia. Through Aramco and Caltex, SoCal also took part in projects like the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, or Tapline, a roughly 1,700-kilometer line carrying Saudi crude across the desert to the Mediterranean. It invested in tanker fleets, refineries, and petrochemical plants—locking in the full chain from wellhead to end customer on multiple continents.

But even at its peak, the Seven Sisters era had a built-in fault line. Oil-producing countries increasingly viewed the old system as lopsided: foreign companies controlled operations and captured most of the upside, while host governments received limited royalties. In 1960, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Venezuela formed OPEC to coordinate policy and push for better terms. At first, the majors treated it like a talking shop. It wouldn’t stay that way. The balance of power in oil was already shifting—and the next chapter would prove just how much.

VI. The Gulf Merger & Becoming Chevron (1973-1984)

1973 didn’t just rattle the oil business. It rewrote the rules.

On October 6, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel, igniting the Yom Kippur War. The U.S. responded with an airlift of military supplies to Israel. In retaliation, OPEC’s Arab members imposed an oil embargo on America and other countries seen as Israeli supporters. Saudi Arabia—the world’s largest exporter, and the country at the center of SoCal’s most important overseas relationship—cut production and halted shipments to the United States.

The shock hit fast. Gasoline prices jumped, and Americans found themselves idling in long lines at service stations, hoping the pumps wouldn’t run dry before their turn. Washington scrambled: rationing plans, lower speed limits, even calendar tweaks meant to shave consumption. The crisis made one thing undeniable: the U.S. economy had been built on the assumption of plentiful, cheap oil—and that assumption could be weaponized.

For Standard Oil of California, the immediate effects were strangely mixed. The embargo created shortages and anger, but it also sent prices soaring—roughly quadrupling from pre-crisis levels by early 1974. With production still coming from non-Arab sources, and some Saudi oil continuing to move through Aramco’s complex arrangements, SoCal’s profits surged. It was the kind of moment that turned oil companies into political targets. Congress held hearings. Demonstrators showed up outside SoCal’s San Francisco headquarters. The industry looked less like an engine of progress and more like a suspect.

The longer-term outcome was far more consequential for SoCal’s future: the balance of power in Saudi Arabia shifted permanently. Starting in 1973, the Saudi government began buying equity in Aramco from its four American parents. Step by step, it took ownership. By 1980, nationalization was complete. Aramco was no longer a Western-controlled joint venture; it was a Saudi national oil company. SoCal and its partners still had management roles and purchase arrangements, but they no longer owned the reserves that had defined their rise.

For SoCal, this was an identity-level rupture. For nearly forty years, Saudi Arabia had been its growth engine—its biggest wins, its largest production base, its most lucrative cash flows. Now that foundation belonged to someone else. If SoCal wanted to remain a top-tier oil company, it needed new barrels, preferably outside OPEC’s grip. The hunt for non-OPEC reserves wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was survival.

That’s what made acquisition suddenly feel like strategy, not opportunism. The late 1970s and early 1980s became a period of consolidation as majors chased scale, geographic diversification, and reserves they could actually control. In 1984, SoCal made the biggest move of its life to that point: it agreed to buy Gulf Oil for $13.2 billion, the largest industrial merger in history at the time.

Gulf wasn’t just any target. It was one of the original Seven Sisters, with roots in the 1901 Spindletop gusher that helped launch the Texas oil boom. It brought meaningful reserves and production, including a major position in the Gulf of Mexico—an offshore frontier that had become one of America’s most important sources of new supply—plus assets in places like the North Sea and Nigeria. In a world where Saudi ownership was gone, Gulf’s portfolio offered SoCal something it urgently needed: replacement scale.

The deal was also defensive—just not for SoCal. Corporate raider T. Boone Pickens had built a significant stake in Gulf and was pushing for a breakup or sale. Gulf’s leadership, eager to avoid being dismantled on Pickens’ terms, went looking for a friendly buyer. SoCal stepped in as the white knight, paying a premium that rewarded shareholders and cut off Pickens’ endgame.

When the merger closed in 1984, it also closed a chapter in corporate identity. Standard Oil of California formally became Chevron Corporation, taking the name it had used on service stations for decades. Around the same time, the company shifted its headquarters from downtown San Francisco to San Ramon, California—part of the era’s broader move toward suburban corporate campuses. The old name, the one that tied the company directly to Rockefeller’s empire, finally faded into history.

But the new Chevron didn’t arrive fully formed. Integrating Gulf was messy and painful. The two companies had overlapping assets and different cultures, and regulators demanded changes. Chevron cut thousands of jobs and sold billions of dollars in businesses to satisfy antitrust requirements and streamline the combined operation. The pattern was set: go big, then spend years digesting—selling what you don’t need, keeping what makes you stronger.

And it wouldn’t be the last time Chevron followed that script.

VII. The Texaco Acquisition: Creating a Supermajor (1999-2001)

The oil industry rolled into the 1990s with a brutal contradiction. The world kept using more oil—especially as emerging markets industrialized—but the price didn’t cooperate. The Soviet Union collapsed, Russian barrels surged back onto global markets, and OPEC’s quota system weakened as members quietly produced above their targets. By 1998, crude fell below $15 a barrel—cheaper, in inflation-adjusted terms, than at any point since before the 1973 embargo.

For oil companies, low prices weren’t an inconvenience. They were an existential stress test. Projects that penciled out at $25 oil turned ugly at $12. Budgets got cut, exploration slowed, layoffs spread, and the industry did what it always does under pressure: it consolidated.

In 1998, BP bought Amoco, creating BP Amoco. Then Exxon and Mobil—two of the biggest Standard Oil descendants—announced a merger that would create ExxonMobil, instantly the largest oil company on earth. A new tier was forming, and if you weren’t in it, you risked getting pushed out of the biggest opportunities.

Chevron wasn’t standing still. After Gulf, it had built serious positions in deepwater Gulf of Mexico, Indonesia’s gas business, and Kazakhstan’s giant Tengiz field. But compared to the emerging supermajors, Chevron was still smaller—and CEO Kenneth Derr worried that size would become strategy. The next generation of mega-projects demanded enormous capital, political leverage, and global operating scale. Being “very good” wasn’t enough if you couldn’t write the biggest checks.

That made Texaco the obvious partner.

The relationship went back decades. The two companies had been tied together since Texaco bought into the Saudi venture in 1936, and they still shared ownership of Caltex, their international marketing business across Africa and Asia-Pacific. They knew each other’s people, they understood each other’s systems, and on paper the overlap promised the holy grail of merger logic: cut duplicative costs, simplify a sprawling footprint, and come out with a stronger portfolio.

But the first attempt went nowhere. In 1999, when Chevron approached Texaco, Texaco’s board reviewed the offer and rejected it as “unacceptable for complexity, feasibility, risk and price.” Texaco CEO Peter Bijur preferred staying independent and wasn’t convinced the disruption was worth it. Chevron backed off—but it didn’t stop thinking about what scale would require.

Meanwhile, the consolidation wave kept rising. TotalFina combined with Elf Aquitaine in Europe. BP Amoco bought ARCO and deepened its U.S. presence. Every deal reset the bar. Chevron and Texaco—both big, both proud, both suddenly looking mid-sized—felt the squeeze.

By mid-2000, the conditions changed. Oil prices had recovered, which made the economics of a merger easier to justify. Leadership dynamics at Texaco shifted toward a more consolidation-friendly posture. And after watching regulators approve other megamergers, some of the antitrust fog looked more navigable than it had a year earlier.

On October 16, 2000, Chevron and Texaco announced a definitive agreement: Chevron would buy Texaco in a stock deal initially valued at $36 billion, ultimately landing around $45 billion by the time it closed as Chevron’s share price rose. The combined company would be called ChevronTexaco, and it would slot in as the second-largest U.S. oil company—behind only ExxonMobil.

Regulators, unsurprisingly, had conditions. The Federal Trade Commission required major divestitures, including Texaco’s stakes in two big downstream joint ventures, Equilon and Motiva, which ran refineries and service stations across the U.S. Those assets went to Shell, easing market-share concerns and, in the process, strengthening Shell’s position in American refining and retail.

The merger closed on October 9, 2001—less than a month after the September 11 attacks rattled markets and injected a new kind of geopolitical uncertainty into the system. ChevronTexaco went forward anyway. Dave O’Reilly, Chevron’s CEO who took the helm of the combined company, framed the mission clearly: this wasn’t about empire-building for its own sake. It was about efficiency, focus, and extracting more performance from the portfolio.

Execution was harder than the press release. Texaco—founded in 1902 as The Texas Company—didn’t naturally enjoy being absorbed. Overlapping functions had to be cut, duplicate roles eliminated, and offices consolidated across cities where both companies had long maintained large operations. The work was expensive, disruptive, and culturally abrasive—the standard cost of becoming a supermajor.

By 2005, the integration was largely done. ChevronTexaco dropped “Texaco” from the corporate name and returned to Chevron Corporation, even as the Texaco brand lived on at thousands of service stations.

That same year, Chevron made another decisive move: it bought Unocal for $17 billion after outbidding China National Offshore Oil Corporation, whose competing offer had triggered a political firestorm in Washington. Unocal brought valuable assets in Thailand, Indonesia, and the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, plus an important natural gas position in Bangladesh. After spending the early 2000s building scale through merger, Chevron used 2005 to sharpen what that scale was for: securing long-lived international resources and gas—fuel for the next era of the business.

VIII. Modern Chevron: Shale, Sustainability & Strategy (2001-Present)

The twenty-first century did something the oil business had spent decades insisting wouldn’t happen: it made the United States a growth story again.

For a long time, the script seemed set. America’s big conventional fields were aging. Production would keep sliding. Imports from the Middle East, Venezuela, and anywhere else with spare barrels would keep rising. “Energy security” would mean managing dependence.

Then hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling upended the plot. Starting in the late 2000s, producers proved they could pull oil and gas out of shale formations that had been mapped for generations but written off as uneconomic. The Bakken in North Dakota. The Eagle Ford in Texas. And above all, the Permian Basin spanning West Texas and New Mexico. Suddenly, “tight rock” wasn’t a curiosity. It was the engine of a new boom.

U.S. production, which had fallen to about 5 million barrels a day in 2008, climbed hard over the next decade. By 2019, it had pushed past 12 million barrels a day—more than Saudi Arabia or Russia, and the highest level in American history. The United States became a net petroleum exporter for the first time since the 1940s. The shale revolution didn’t just change a supply curve; it rearranged geopolitics.

Chevron didn’t rush in as a born-again wildcatter. Its instincts—and its strengths—were built around giant conventional projects: deepwater platforms, LNG plants, and overseas developments designed to run for decades. Shale is the opposite kind of machine. Wells decline fast, and you have to keep drilling to keep production flat. It’s less a handful of monumental bets and more a relentless manufacturing process.

But the economics left little room for nostalgia. Shale offered faster paybacks and, in the right basins, lower costs. Capital across the industry flowed toward it, and Chevron adapted. It leaned into the Permian, where it already had a substantial legacy position going back to the early twentieth century, and it expanded that footprint with targeted acquisitions. By the mid-2020s, the Permian had become Chevron’s largest and most profitable production engine—throwing off the cash that funded dividends, buybacks, and the rest of the portfolio.

That pattern showed up in Chevron’s dealmaking. In 2020, it bought Noble Energy for $13 billion, adding scale in the DJ Basin of Colorado and gaining Eastern Mediterranean natural gas fields offshore Israel that Noble had developed. In 2023, Chevron bought PDC Energy for $6.3 billion, bolstering both Permian acreage and DJ Basin production. The common thread wasn’t a love of exploration risk. It was Chevron’s preference for buying proven positions, then operating them hard and efficiently.

Then came the biggest swing since Texaco: Hess.

Announced in October 2023 and closed in 2025, Chevron’s acquisition of Hess brought two crown-jewel assets. First, a dominant position in the Bakken formation in North Dakota, one of America’s most productive shale plays. Second—and more strategically—the prize offshore Guyana: Hess’s 30% stake in the Stabroek Block, where ExxonMobil, as operator, had announced more than 11 billion barrels of recoverable oil discoveries since 2015.

Guyana was the magnet, and it was also the trapdoor.

ExxonMobil, with a 45% stake and operatorship of Stabroek, argued it held preemption rights over changes in ownership. In Exxon’s view, Chevron buying Hess triggered those rights, meaning Exxon could buy Hess’s Guyana interest instead. Chevron disagreed, and the dispute went to arbitration.

The fight stretched the timeline well past expectations. When arbitrators ruled in late 2024 that Chevron could proceed without triggering Exxon’s preemption rights, the path cleared. The deal closed in early 2025, and Chevron walked away with a major position in what many analysts see as the most attractive new oil development in the world: fast-growing production, low costs, and fiscal terms set before the scale of the discoveries was fully understood.

All of this was happening as Chevron made another shift—this one more cultural than geological. In 2024, the company announced plans to relocate its global headquarters from San Ramon, California, to Houston, Texas. The reasoning was practical: Houston is the center of the U.S. oil and gas industry, and many Chevron employees were already there. Texas also offered a regulatory and tax environment more aligned with Chevron’s core business than California. But it was also symbolic. After a century and a half, Chevron was leaving the state where its corporate lineage began.

Over the same period, Chevron’s stance on the energy transition hardened into a clear identity: cautious, disciplined, and unapologetically centered on oil and gas.

While European peers like BP and Shell made ambitious announcements around carbon targets and renewables investment, Chevron emphasized that global energy demand would keep rising—and that oil and gas would remain essential for decades. CEO Mike Wirth argued that Chevron’s job was to produce those hydrocarbons more responsibly than many competitors, and to avoid chasing lower-return projects simply to follow a narrative.

That approach bought Chevron credibility with investors who wanted capital discipline and cash returned, not grand reinvention. It also made the company a frequent target for critics who argued that modest commitments to lower-carbon technologies exposed Chevron to long-term risk as the world pushed to decarbonize.

The argument isn’t settled. Chevron’s strategy amounts to a high-conviction bet: that the world will keep needing large volumes of oil and gas longer than many forecasts assume—and that the best way to win that future is to own the best barrels, run them efficiently, and return the proceeds to shareholders.

IX. Playbook: The Chevron Management Philosophy

Chevron’s longevity—from a modest California well to the Hess acquisition—doesn’t come from one genius move or one lucky strike. It comes from a set of management habits the company has repeated across wars, oil shocks, booms, busts, and technological revolutions. If you want to predict what Chevron will do next, this is the closest thing to a map.

First: capital discipline through commodity cycles. Oil is a business where the ground doesn’t move nearly as much as the price does. When prices spike, it’s tempting to spend like the good times will last forever. When prices crash, the companies that loaded up on debt suddenly have to sell their best assets just to survive. Chevron has generally tried to live on the other side of that mistake: keeping the balance sheet conservative, protecting its credit quality, and resisting the urge to overbuild at the top. The payoff is optionality. When the cycle turns and others are forced into fire sales, Chevron can step in and buy. That pattern shows up again and again in its biggest moments—Gulf, Texaco, and later Hess.

Second: an “acquire and optimize” mindset. Chevron can explore, and it has—Saudi Arabia is the proof. But over time, the company increasingly preferred a different way to grow: buy resources that are already proven, then apply Chevron’s operating system to squeeze more value out of them. Exploration is a high-variance business; most wells don’t become commercial successes, and even a great discovery can take years to turn into cash flow. Acquisitions, by contrast, can deliver producing assets immediately. Over the decades, Chevron’s mix shifted accordingly: less emphasis on swinging for brand-new finds, more emphasis on purchasing established positions and running them harder and cleaner.

Third: technology and operational excellence. In oil and gas, small differences in cost, uptime, and recovery rates become enormous over the life of a field. Chevron’s advantage has often been less about owning a unique idea and more about executing consistently—safety systems that prevent disruptions, maintenance discipline that keeps assets running, and engineering that improves performance year after year. Its research base in Richmond, California, has contributed innovations from enhanced oil recovery to deepwater capabilities that make previously unreachable barrels economic. The result is simple: from the same asset base, strong operators can produce more, for longer, with fewer costly surprises.

Fourth: geopolitical risk management—hard-earned, and never perfect. Saudi nationalization taught the whole industry a blunt lesson: reserves you don’t control can disappear with a signature. Chevron still operates around the world, often in places where politics and contracts are as important as geology. That requires a specific playbook: structuring agreements to withstand policy shifts, building local relationships, and staying as neutral as possible when the political ground moves. It doesn’t always work. Chevron’s assets in Venezuela were effectively nationalized during the Chávez era, and its involvement in Myanmar has drawn human rights criticism. But compared to many peers, Chevron has shown a repeated ability to operate in complex environments without losing the plot.

Fifth: shareholder returns as a core promise, not a leftover. Chevron has increased its dividend for 37 consecutive years through early 2025, spanning recessions, oil price collapses, and industry restructuring. When cash flows are strong, buybacks add another layer of return. Management has been unusually explicit about the hierarchy: returning capital comes first, and growth spending has to earn its place. That posture is one reason Chevron attracts investors who want reliability more than moonshots—especially in a sector where fortunes can turn fast.

Finally: a cultural DNA that still traces back to Standard Oil, even after more than a century on its own. Chevron remains, at heart, an engineering-led organization. Leaders tend to come up through operations, not from Wall Street. The company favors analysis, planning, and repeatable processes over dramatic reinvention. To outsiders, that can look cautious or even slow. But it’s also a major reason Chevron has endured while flashier strategies—big bets at the top of the cycle, empire-building without discipline, growth for growth’s sake—have wrecked plenty of rivals.

X. Bull vs. Bear: Investment Analysis

Chevron’s investment case turns on a few deceptively simple questions: How long will the world keep consuming large volumes of oil and gas? How quickly will alternatives scale? And in a commodity business where prices swing and politics intrudes, which companies have the assets and operating discipline to stay profitable through whatever comes next?

Reasonable people look at the same facts and land in different places. That’s what makes Chevron such a clean “bull vs. bear” story: both sides have real arguments.

The Bull Case

Start with the obvious advantage: Chevron owns some of the most attractive hydrocarbon real estate on the planet.

In the Permian Basin, Chevron has a legacy position that traces back generations, and it’s exactly the kind of asset Wall Street loves in the shale era: large scale, repeatable drilling inventory, and costs low enough to keep working even when oil prices fall. Offshore, its Gulf of Mexico portfolio sits in one of the world’s most productive deepwater basins—high-output wells and long-lived platforms that can generate cash for years once built.

And then there’s Guyana, acquired through Hess. It’s hard to overstate how rare it is for a major to buy into an offshore development that’s both massive and fast-growing, with economics that still work at prices that would break many projects. Bulls point to breakevens below $30 a barrel and see a decade-plus runway of advantaged barrels—exactly what supermajors compete for.

The second pillar is operational discipline. Chevron’s reputation—fairly or not—is that it’s less flashy than some peers, but more consistent. In a business where small differences in cost and uptime compound into enormous differences in long-term value, Chevron’s edge is execution: strong operating performance in the Permian, high reliability in deepwater, and a tendency to prioritize projects that can clear internal return hurdles without heroic price assumptions. When that machine is running well, it tends to convert barrels into free cash flow more efficiently than the average major.

Then there’s the shareholder proposition. Chevron has increased its dividend for 37 consecutive years through early 2025, including through downturns that forced others to cut. Add buybacks on top, and the bull view is straightforward: if you want energy exposure with a relatively predictable capital return policy, Chevron is one of the cleanest options.

Finally, bulls argue that “higher for longer” oil prices are not just possible—they’re plausible. Since 2014, the industry has spent years underinvesting in new supply relative to what long-cycle depletion demands. OPEC+ has shown more willingness to manage supply. And while demand growth is slowing in some developed markets, it continues in many developing economies. If those forces keep the market tighter than many forecasts assume, Chevron’s advantaged cost structure becomes a lever: strong cash generation at high prices, and resilience when prices soften.

Applying Porter’s Five Forces

The threat of new entrants stays low. Building meaningful oil and gas production at scale takes huge capital, specialized talent, and years of execution—plus the ability to navigate regulation, permitting, and geopolitics. Most “new entrants” in energy are showing up in renewables and storage, not in deepwater or global upstream.

Supplier power is real but cyclical. When drilling activity heats up, service companies can raise prices, and shortages in skilled labor can slow work. But there are multiple service providers, and a company of Chevron’s size can negotiate and plan in ways smaller operators can’t.

Buyer power is limited because oil is a commodity. Chevron can’t negotiate a special price for a barrel of crude. Where it gets some insulation is integration: refining, marketing, and branded retail can capture downstream margin that pure producers never see.

The threat of substitutes is the energy transition, plain and simple. Electric vehicles pressure gasoline demand. Renewables and storage compete in power generation. Efficiency reduces energy intensity. The key uncertainty isn’t whether substitution is happening—it is—but how fast it spreads globally, and whether demand declines in rich countries outweigh growth elsewhere.

Competitive rivalry is intense. The majors and large independents are chasing a relatively limited set of top-tier opportunities, which can push up acquisition prices and project costs. Meanwhile, national oil companies increasingly compete directly instead of partnering. In that environment, bulls argue that the winners will be the companies with the best assets and lowest costs—precisely where Chevron wants to position itself.

Applying Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers

Scale economies are a clear advantage. Chevron’s size improves purchasing power and lets it spread overhead across a larger base. Shared infrastructure—pipelines, processing, export capacity—adds leverage that smaller operators struggle to match.

Network effects don’t map neatly onto commodity production. But Chevron’s integrated chain, from upstream through refining to retail, does create coordination benefits that a pure-play driller doesn’t have.

Counter-positioning shows up in Chevron’s contrast with some European peers. While BP and Shell leaned harder into renewables and broader “energy company” repositioning, Chevron stayed more centered on oil and gas, with smaller bets on lower-carbon technologies. If the transition moves slower than the most aggressive scenarios, Chevron’s strategy could look disciplined rather than behind. If it moves faster, that same choice becomes a risk.

Switching costs matter in pockets: refinery configurations, product supply relationships, specialized logistics, and technical expertise can create stickiness. But crude itself is still traded in a global market.

Branding matters most at the pump. Chevron and Texaco are recognized names, which can help at the margins, even if gasoline is largely undifferentiated.

Cornered resources may be Chevron’s strongest “power”: scarce, hard-to-replicate positions like its Permian footprint, deepwater discoveries, and its stake in Guyana. Competitors can’t simply recreate those assets with effort alone; many are effectively irreplaceable.

Process power is the quieter edge: the accumulated operating capabilities—deepwater execution, project management, enhanced recovery techniques, and safety and reliability systems—that help Chevron get more value out of similar rocks than a weaker operator.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a different framing: the big risk isn’t running out of oil. It’s demand rolling over.

If EV adoption keeps accelerating, if renewable electricity continues to outcompete fossil generation in more markets, and if policy pressure keeps tightening—unevenly, but persistently—then global oil demand could peak and decline. In that world, the key question becomes not “how many reserves do you have,” but “how quickly can you produce the best ones before the market turns against you?”

That’s where stranding risk enters the picture. Reserves expected to generate cash for decades are dramatically more valuable than reserves that are forced to shut in earlier than planned. Bears argue that markets still underprice how quickly demand could shift, and that long-dated hydrocarbon portfolios are more vulnerable than traditional valuation models admit.

Capital markets are another pressure point. ESG constraints have already pushed some institutional money away from fossil fuels, and that exclusion could widen. The direct impact on Chevron’s valuation may be hard to isolate, but bears argue the long-term consequence is clear: a higher cost of capital and a smaller pool of natural buyers.

Then there’s regulation and litigation. Chevron faces a growing menu of risks: lawsuits tied to climate impacts, stricter permitting and emissions rules, and the possibility of carbon pricing that raises costs or changes project economics. Because Chevron operates across many jurisdictions, compliance is complicated—and policy shifts can create real stranded-asset exposure, especially in markets that tighten faster than expected.

Finally, the competitive landscape is changing. National oil companies like Saudi Aramco and ADNOC are increasingly willing to compete head-on, and they often don’t play by the same financial rules. Because they serve national strategic priorities, they may accept lower returns than public shareholders would tolerate. Bears argue that in a world with fewer attractive growth opportunities, that competition compresses returns for everyone else.

KPIs That Matter

If you’re tracking Chevron as an investor, three metrics tell you more than most headlines:

First, return on capital employed (ROCE). It’s the clearest single read on whether Chevron is actually turning its asset base into attractive profits, or simply getting bigger without getting better. Chevron has historically posted ROCE in the low-to-mid teens in strong price environments; sustained erosion would be a warning sign on asset quality or capital allocation.

Second, upstream unit costs—what it costs Chevron to find, develop, and operate each barrel. In any future where demand growth slows or declines, the lowest-cost barrels win, because they can keep producing profitably long after higher-cost supply gets forced out.

Third, free cash flow yield. It’s the simplest way to ask: what are you paying for the cash Chevron generates? The sector often trades at elevated yields because the market worries about durability. Watching Chevron’s yield versus peers and versus its own history is a good proxy for how optimistic—or skeptical—investors are becoming about the company’s future.

XI. Power & Greed: The Darker Chapters

No company survives 150 years in a business as essential—and as politically charged—as oil without leaving scars. Chevron’s history has them. Depending on who’s telling the story, they’re either evidence of corporate wrongdoing or the ugly, recurring side effects of operating at scale in a hard industry.

Start with a nickname: the “terrible twins.” For decades, SoCal and Texaco carried reputations for being especially ruthless competitors. Both were Standard Oil descendants, and both inherited more than assets from the Rockefeller era—they inherited a mindset. Through the mid-twentieth century, critics accused them of tactics like predatory pricing, exclusive dealing, and carving up markets in ways that made it harder for smaller rivals to survive. Whether you see that as smart competition or anti-competitive behavior, the outcome was the same: they became powerful, and they became feared.

Chevron’s most famous—and most bitterly contested—controversy came through Texaco: the Ecuador litigation tied to oil operations in the Amazon.

Between 1964 and 1992, Texaco operated a consortium that developed production in Ecuador’s rainforest, near Lago Agrio. Local communities and environmental groups alleged widespread contamination from the work—spills, toxic waste disposal, and long-term damage to land and water that harmed Indigenous populations and degraded ecosystems.

When Chevron bought Texaco in 2001, it didn’t just acquire assets and brands. It acquired that fight.

Ecuadorian courts ultimately issued a $9.5 billion judgment against Chevron, one of the largest environmental verdicts ever. Chevron refused to pay, arguing the judgment was the product of fraud and corruption, including fabricated evidence and bribery. Courts in the United States largely sided with Chevron on enforcement, blocking collection of the Ecuadorian judgment and finding misconduct by the plaintiffs’ lawyer. The case stretched into a multi-decade global legal war, with both sides pointing to different rulings as proof they were right. And underneath all of it sat the human reality: parts of the Ecuadorian Amazon remained polluted, communities remained affected, and the question of accountability never found an ending that satisfied everyone.

Chevron has also faced criticism for operating in countries where the politics are ethically fraught. Work in Myanmar during military rule. Operations in Nigeria where security forces protected facilities. Investments in places like Kazakhstan and Angola, where corruption has long been a concern. Critics argue that doing business under authoritarian governments can mean enabling them, directly or indirectly. Chevron’s response has been consistent: operating responsibly can bring jobs and development, engagement is better than isolation, and if Western companies leave, others with fewer standards will take their place. It’s a familiar argument in global energy—and an unresolved one.

Then there’s climate.

Like other oil majors, Chevron funded research and advocacy groups that questioned or downplayed climate science and opposed carbon regulation. Litigation and document releases have suggested that company scientists understood climate risks long before public messaging fully reflected them. Today Chevron acknowledges climate change and supports some emissions-reduction policies, but critics argue the industry—including Chevron—spent decades slowing action while continuing to profit from fossil fuels.

Finally, there are the impacts closer to home: labor, safety, and community health. Heavy industry is unforgiving, and Chevron’s record includes accidents, spills, and occupational hazards. One of the most consequential incidents in recent memory was the August 2012 fire at Chevron’s Richmond, California refinery—one of the oldest in the country, operating since 1902. The event sent roughly 15,000 residents to hospitals reporting respiratory symptoms, and it intensified long-running complaints from local community groups about pollution and oversight.

None of these controversies belong to Chevron alone. They’re part of the oil industry’s broader legacy: enormous benefits paired with real harm, spread across decades and jurisdictions. But Chevron’s scale and longevity mean more exposure—more places where things can go wrong, and more history for critics to point to. For investors, that translates into a different kind of risk: not just commodity prices and drilling results, but legal liabilities, regulatory pressure, and reputational damage that can shape what Chevron is able to do next.

XII. Epilogue: What Does the Future Hold?

Chevron entered the second half of the 2020s caught between two forces that don’t like to share the same room. On one side: the physical reality of climate change, now impossible to ignore, pushing governments, companies, and consumers toward decarbonization. On the other: global energy demand that keeps climbing, powered by developing economies where billions of people are still chasing the basic comforts that reliable, affordable energy makes possible. Reconciling those truths—human flourishing without blowing past planetary limits—may be the central challenge of the century. And as one of the world’s largest energy producers, Chevron doesn’t get to sit it out. Whatever the solution looks like, Chevron is going to be part of it.

Chevron’s most straightforward bet has been natural gas: the “bridge fuel” that can cut emissions versus coal while still keeping grids stable. Its LNG footprint, including major projects in Australia and gas positions in the Eastern Mediterranean, is designed to feed Asian demand as countries try to clean up power generation without risking blackouts. In many transition scenarios, gas holds up better than oil, especially as passenger vehicles electrify faster than heavy industry and power systems can fully decarbonize. But the bridge metaphor comes with a catch. A bridge is supposed to lead somewhere. If the world ends up relying on gas for decades longer than hoped, it may blunt emissions rather than solve them.

Chevron’s clearest lower-carbon moves sit in hydrogen and carbon capture. The company has invested in hydrogen production facilities, carbon capture and storage projects, and research aimed at reducing the carbon intensity of its operations. Relative to the size of its oil and gas business, these efforts are still small—supporters call that disciplined; critics call it window dressing. Either way, the strategic logic is real: it’s an options portfolio. If policy tightens faster, or technology improves quicker, Chevron wants a foothold in the parts of the transition that still look adjacent to its strengths: large-scale projects, molecules, infrastructure, and long-life industrial systems.

Another thing that seems likely: more consolidation. The post-1990s merger wave created today’s familiar lineup—ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, TotalEnergies—and the pressure that drove those deals hasn’t vanished. As growth opportunities narrow and scale becomes even more valuable, the industry could keep compressing. Chevron has historically played offense, buying when the moment is right. But speculation persists in the other direction too: in a world of fewer, bigger players, even giants can become chess pieces. Whether Chevron ends up as acquirer, target, or both—potentially circling mid-sized producers like ConocoPhillips and Occidental Petroleum—will depend on commodity cycles, politics, and what regulators will allow.

Looking back over 150 years makes one lesson hard to miss: the oil industry has a talent for humiliating forecasters. The crew at Pico Canyon in 1876 couldn’t have imagined Saudi Arabia becoming an energy superpower. The executives who signed the 1933 concession couldn’t have predicted nationalization. The leaders who bought Gulf couldn’t have seen shale turning the U.S. into a production powerhouse again. The next era will likely bring its own plot twists—new technologies, policy shocks, wars, breakthroughs, and failures that don’t fit neatly into today’s models.

Still, some things are stubborn. Oil and natural gas aren’t disappearing on any timeline that looks “foreseeable” in the practical sense. The world runs on hydrocarbons not just because of cars, but because of industrial heat, aviation, shipping, petrochemicals, and power systems that still need reliable backup. Replacing all of that takes more than ambition—it takes an extraordinary buildout of infrastructure at a scale and pace that most countries have barely begun.

For investors, Chevron remains a concentrated wager on that durability. The bull case—premium assets, operational excellence, capital discipline, shareholder returns—depends on oil and gas demand staying high enough, long enough, to justify continued investment. The bear case—peak demand, stranded assets, ESG pressure, regulation and litigation—assumes the transition accelerates in ways that compress the life of hydrocarbon portfolios. Both contain real risk. The question is which force wins the timeline.

What’s undeniable is the arc. A company born from California wildcatters became a global operator spanning every inhabited continent, shaped by Standard Oil’s breakup, Saudi Arabia’s rise, OPEC’s leverage, and shale’s resurgence. Chevron has never been static; it has been re-formed again and again by the world around it. Whatever the energy system becomes next, the record suggests Chevron will try to do what it has always done: adapt, scale, and place bets meant to pay off over decades.

XIII. Recent News

The first weeks of 2026 brought a quick reminder that Chevron’s story doesn’t pause just because the Hess headlines have faded. The company wrapped up the Hess acquisition in early 2025, after arbitrators rejected ExxonMobil’s claim that it had preemption rights in Guyana. With that final obstacle cleared, Chevron officially added two assets it had been chasing for more than a year: Hess’s Bakken position and its stake in Guyana’s Stabroek Block. In the early innings, Chevron said integration was going smoothly—and kept the message simple: more high-quality barrels, more reserves, and more cash flow capacity.

When Chevron reported fourth-quarter 2025 results in late January 2026, the tone stayed upbeat. Results came in ahead of what analysts expected, helped by continued growth in Permian production, ramping volumes from Guyana, and commodity prices that remained supportive. Management used the moment to reinforce the promises Chevron investors care about most: continued dividend growth and an ongoing share buyback program. And despite the scale of Hess, Chevron emphasized that the balance sheet remained conservative.

Operationally, another long-telegraphed shift kept moving forward: the headquarters relocation to Houston. Through 2025, more corporate functions transitioned to Texas, leaving San Ramon with a reduced—though still present—set of operations. The move didn’t land as a major flashpoint, largely because Chevron had laid out the timeline well in advance and the logic was straightforward. The company’s center of gravity had moved to the capital of the U.S. energy industry.

On the policy front, the backdrop remained unsettled. Federal leasing on public lands, methane emissions rules, and the possibility of carbon pricing were all active topics, with the incoming administration’s direction still unclear. Chevron acknowledged the uncertainty in earnings calls, but avoided forecasting specific outcomes—sticking to what it could control: operating performance, capital discipline, and returns to shareholders.

XIV. Links & References

Company Filings

Chevron’s annual reports and SEC filings—its Form 10-Ks and quarterly 10-Qs—are available through the SEC’s EDGAR database and Chevron’s investor relations site. They’re the most direct source for financial statements, risk factors, and management’s explanation of what’s driving results.

Chevron’s proxy statements (DEF 14A filings) are the go-to documents for executive compensation, board and governance structure, and shareholder proposals.

Historical Sources

Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (1990). A definitive global history of the oil industry, with extensive coverage of Standard Oil, the Saudi discovery story, and the Seven Sisters.

Sampson, Anthony. The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Shaped (1975). A classic account of the majors’ dominance in the mid-twentieth century and how oil power translated into geopolitical power.

Stegner, Wallace. Discovery! The Search for Arabian Oil (1971, reprinted 2007). A detailed narrative of CASOC’s early years in Saudi Arabia—commissioned by Aramco, but written with the craft of a major American novelist.

Industry Reports

International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook. Annual assessments of global energy supply-and-demand trends and forward-looking projections.

Wood Mackenzie and Rystad Energy publish detailed research on company operations, asset economics, and competitive positioning across the oil and gas industry.

Long-Form Journalism

Bloomberg, Reuters, and the Financial Times cover Chevron’s strategy, earnings, and industry context as the story develops. The Wall Street Journal’s energy reporting often goes deeper on major M&A, regulatory moves, and competitive dynamics.

The New Yorker, ProPublica, and other investigative outlets have produced extensive reporting on the Ecuador litigation, climate lobbying, and environmental controversies.

Documentaries and Media

"Crude" (2009) documents the Ecuador litigation largely from the plaintiffs’ perspective.

PBS Frontline, the BBC, and other documentary series have covered the modern history of oil—and Chevron’s place in the global energy system.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music