Datadog: The DevOps Monitoring Unicorn That Said No to Cisco

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

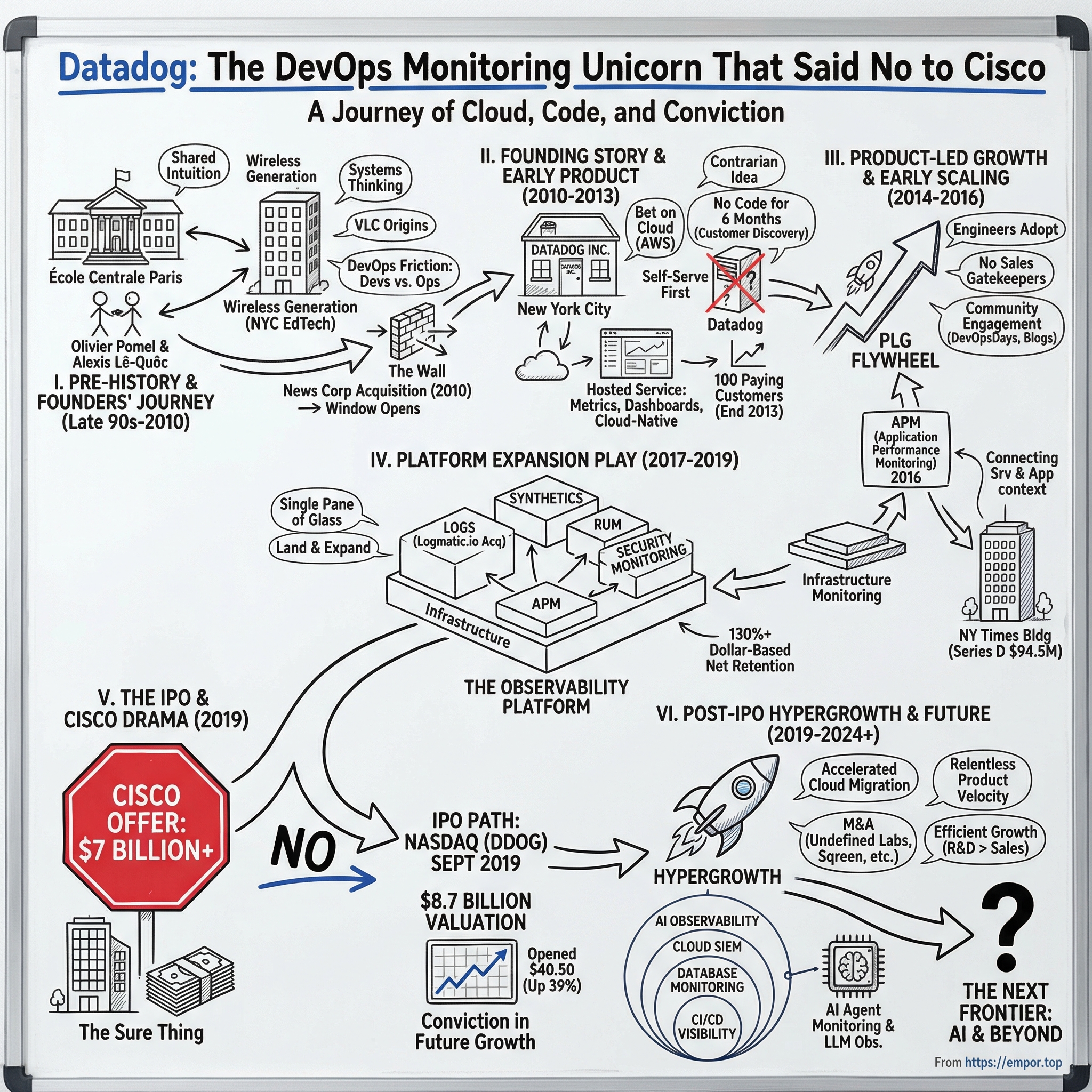

September 2019. Manhattan is slipping from summer into fall, and Datadog CEO Olivier Pomel is staring at the kind of offer that ends most startup stories on the spot. Cisco—one of the giants of enterprise tech—has come knocking with a bid of more than $7 billion to buy Datadog.

For most founders, that’s the finish line: a decade of work crystallized into a single, definitive win. A headline. A payout. Validation.

Pomel said no.

So what makes a French engineer running a monitoring company out of New York confident enough to walk away from a deal that big and roll the dice on the public markets instead? To answer that, you have to understand two things: the founders’ unusually long path to getting here—and the shift in computing they saw early, before it was obvious to everyone else.

Datadog began in 2010, founded by Pomel and Alexis Lê-Quôc. They met as undergraduates at École Centrale Paris, then spent nine years working side by side at an education technology company called Wireless Generation. By the time they struck out on their own, they’d built the kind of shared intuition most co-founders never develop—about products, about systems, and about what breaks when software meets the real world.

Their insight was straightforward, but perfectly timed: companies were leaving on-prem servers for the cloud, and the tools used to monitor those systems were stuck in the old era. Traditional monitoring assumed stability—machines with names, static IPs, and predictable infrastructure. Cloud infrastructure was the opposite: dynamic, ephemeral, constantly changing, and multiplying in complexity as teams shipped faster and architectures went distributed.

Datadog set out to be the new control panel for that world. What started as infrastructure monitoring evolved into the leading platform for what we now call observability: the ability to see what’s happening inside modern software systems as they run, fail, recover, and scale.

Datadog went public in September 2019 at an $8.7 billion valuation. Since then, it has grown to roughly a $45 billion market cap, expanding from infrastructure monitoring into application performance monitoring, log analytics, security monitoring, and, more recently, tools to observe AI systems and large language models.

This is the story of how two immigrants built an enterprise software juggernaut from New York City, turned a simple but contrarian idea into a category-defining platform, and—when the biggest buyer in the room showed up—chose to keep going.

II. Pre-History: The Founders' Journey

Datadog’s origin story doesn’t start in a startup loft. It starts in the hallways of École Centrale Paris, one of France’s elite engineering schools, in the late 1990s—right as the internet was turning from academic curiosity into commercial force. Olivier Pomel and Alexis Lê-Quôc were there at the same time, absorbing the same training: rigorous systems thinking, a bias for first principles, and a comfort with problems that look too big to fit on a whiteboard.

Pomel, especially, didn’t stay inside the lines. While he was still a student, he helped write the early code for a scrappy campus project that turned into something much larger: VLC media player. What began as a way to stream video across the university network became one of the world’s most widely used open-source applications. Pomel was one of the original authors. He eventually stepped away as his career moved on, but the experience was formative—shipping software into the wild, to every kind of machine, under every kind of condition, and watching how reliability becomes a product feature, not just an engineering nicety.

After school, both Pomel and Lê-Quôc spent time at IBM Research, getting a front-row seat to distributed systems and large-scale data. But the chapter that really shaped Datadog came next: Wireless Generation, a New York-based education technology company founded in 2000 to build software for K–12 teachers.

At Wireless Generation, Pomel rose to VP of Technology, scaling the development organization from a small group into nearly a hundred engineers. Lê-Quôc became Director of Operations, responsible for the infrastructure that kept the product running. They worked side by side for nine years as the company grew to serve more than 4 million students across 49 states.

This wasn’t consumer software where a hiccup meant a few annoyed users. These were tools teachers depended on every day. Real classrooms. Real deadlines. Real consequences. When the system went down, it wasn’t just a bad metric—it was a school day disrupted.

Those years also dropped Lê-Quôc into the early current of what soon got a name: DevOps. Around 2008, a small group of engineers started pushing back on the traditional model where developers “build” and operations “runs,” separated by tickets, handoffs, and blame. Lê-Quôc became part of that community—speaking at early DevOpsDays and trading battle stories with people who believed the wall between dev and ops was slowing teams down and making systems brittle.

At Wireless Generation, they lived that problem. Developers shipped features and handed them off. Ops kept the lights on, often without enough visibility into what the software was actually doing. When something broke, everyone could see that it was broken—but not always why. And the monitoring tools of the era didn’t help. They were built for a world of static, on-prem servers: heavy manual setup, poor integration with emerging cloud services, and very little application-level context.

Then came the event that made the next move inevitable. In November 2010, News Corp acquired a 90% stake in Wireless Generation for $360 million. It was a milestone, but it also marked a turning point. The company they’d spent nearly a decade building was now part of a huge conglomerate—with a different pace, different incentives, and a different culture. The window for building the next thing had opened.

Pomel later put it plainly: “After Wireless Generation was acquired by NewsCorp, we set out to create a product that would reduce the friction we had experienced between developer and systems administration teams, who were often working at cross-purposes.”

So what product would actually do that?

Their answer was ambitious and specific: a unified monitoring platform that could show, in real time, what was happening across both infrastructure and applications; that fit naturally with cloud services like Amazon Web Services; and that was simple enough for engineers to adopt on their own—without weeks of professional services and custom configuration.

It wasn’t an abstract startup idea. It was a solution to their own scars, sharpened by the DevOps movement, and grounded in the kind of deep systems experience that comes from building software that has to work—every day, at scale, with no excuses.

III. Founding Story & Early Product (2010–2013)

In the summer of 2010, Olivier Pomel and Alexis Lê-Quôc incorporated their new company in New York City. The bet was simple to explain and hard for most people to believe: the world was moving to the cloud, and the cloud was going to break the old way of monitoring.

Back then, “monitoring” meant big, expensive suites from vendors like CA Technologies, HP, and IBM. They worked—sort of—but they were built for the on-prem era: machines that stayed put, with fixed addresses, slowly changing over time. They also came with the unspoken requirement of professional services to get anything meaningful set up.

The cloud flipped every one of those assumptions. Infrastructure became disposable. Servers came and went. Scale didn’t mean buying bigger boxes; it meant spinning up fleets of instances and tearing them down minutes later. If you tried to monitor that world with old tools, you didn’t just get the wrong answer. You got no answer at all.

The frustrating part was that, in 2010, almost nobody was convinced this mattered. AWS had launched in 2006, but it was still widely dismissed as a playground for startups. Enterprises didn’t trust it. Traditional IT leaders couldn’t imagine running critical workloads “on someone else’s servers.” And when Pomel and Lê-Quôc pitched investors—especially on the West Coast—they ran into a different kind of skepticism: why would anyone start an infrastructure company in New York?

“None of the West Coast investors were listening, and East Coast investors didn’t understand the infrastructure space well enough to take risks,” Pomel recalled. Silicon Valley VCs, he said, “thought it was a form of mental impairment to start an infrastructure startup in New York.” In 2010, Manhattan wasn’t where you went to build a developer-focused SaaS company. The money, the talent networks, and the default pattern recognition were all in the Bay Area.

So for nearly a year, they did what a lot of founders do before the origin story gets polished: they scraped by. “We were surviving on credit cards and in a ‘not funded, oh my god, how are we going to survive’ mode for about a year,” Pomel admitted.

That scarcity shaped the company. With no cushion, they couldn’t afford to disappear into a product cave and emerge months later hoping the market would care. Instead, they went the other direction: intense validation first. “For the first six months, we didn’t write a line of code,” Pomel explained. “We actually spent all that time talking to potential customers and potential users.” The habit stuck, and it became one of Datadog’s defining traits: building by listening, not guessing.

Even the name came from their previous life at Wireless Generation. The team there named production servers “dogs,” and production databases were “data dogs.” One especially terrifying Oracle database—famous for causing chaos—was nicknamed “Data Dog 17.” When Pomel and Lê-Quôc started the new company, they used “Data Dog 17” as a codename, assuming they’d replace it later with something more polished. But it was memorable. People repeated it. So they dropped the “17” and kept the rest. Datadog. Neither founder, for the record, owned a dog.

Funding came in steps. In July 2010, they secured a small seed investment from Genacast Ventures and NYC Seed. The following April, they raised $1.2 million from RRE Ventures, RTP Global, IA Ventures, and Contour Venture Partners. Contour, a New York-focused fund, became the first institutional investor to take the leap—and would keep backing them in every subsequent round all the way through the IPO.

Out of those early customer conversations came a product that was deliberately straightforward. Datadog launched as a hosted service that collected metrics from servers, applications, and cloud services, and then made them legible through dashboards you could actually use. Install a lightweight agent, and within minutes you could see the basics—CPU, memory, network traffic—and then go deeper from there. Most importantly, it spoke the language of the cloud. It integrated natively with AWS and pulled in the metadata that made modern infrastructure understandable, automatically adapting as environments scaled up, down, or sideways.

The go-to-market choice was just as intentional: self-serve from day one. No long implementations. No professional services as a crutch. An engineer could try it, get value quickly, and share it with the rest of the team. Inside organizations, adoption spread the way the best infrastructure tools spread: one group installs it to solve a real pain, and everyone else starts asking for access.

By the end of 2013, Datadog had crossed 100 paying customers. Not a giant number—but enough to prove the wedge. Cloud adoption was accelerating, and Datadog was positioning itself as the monitoring layer built for that new reality.

IV. Product-Led Growth & Early Scaling (2014–2016)

By 2014, Datadog had stumbled into a superpower that most enterprise software companies spend decades trying to manufacture: engineers were adopting it on their own.

The traditional enterprise playbook is familiar. You hire a big sales force. You chase the Fortune 500. You negotiate long contracts. Then you send in consultants to bolt the thing into place. It can work, but it’s slow, expensive, and full of friction.

Datadog went the other way. The product was built for self-service from the start. An engineer could sign up, install the agent, and see what was happening inside their systems in minutes. No mandatory demo. No gatekeeping. No “talk to sales to get a quote.” It wasn’t just a pricing decision—it was a philosophy: if the product is good, it should sell itself.

That same philosophy showed up in how Datadog marketed. Instead of polished campaigns, they leaned into the places their users actually hung out. They hired engineers who could write and had them publish genuinely useful technical content—deep dives, how-tos, and explanations of problems people were actively Googling at 2 a.m. They became regulars on the community circuit—DevOpsDays, AWS re:Invent, Velocity, Monitorama—where Alexis Lê-Quôc and others spoke less like vendors and more like practitioners swapping notes. It didn’t feel like marketing. It felt like Datadog was part of the community.

Investors started to notice. In 2014, Datadog raised a $15 million Series B led by OpenView Venture Partners. In 2015, they followed it with a $31 million Series C led by Index Ventures, alongside existing backers. The capital went straight into building more product—especially integrations and multi-cloud support. AWS was the center of gravity, but Azure and Google Cloud were becoming real options, and customers didn’t want three monitoring tools for three clouds. Datadog leaned into the “single pane of glass” promise: wherever your infrastructure ran, you should be able to see it in one place.

And that’s when the flywheel really started to spin. A team would adopt Datadog for one service and spend a modest amount. Then the dashboards spread. Another team asked for access. Then another. Over time, what began as a small, practical purchase expanded across the organization into serious spend—without Datadog needing to scale sales effort linearly with revenue. Land small. Expand wide. Repeat.

In early 2016, the company made the move that signaled it wasn’t content to be “just” infrastructure monitoring. Datadog decided to build Application Performance Monitoring, or APM.

Infrastructure monitoring tells you the symptoms: CPU is pegged, memory is climbing, the server is unhealthy. APM tells you why: which request is slow, where it’s spending time, which service is failing, which database query is the culprit. It was also a market with heavyweight incumbents like New Relic, AppDynamics, and Dynatrace—companies with years of head start and deep enterprise footholds.

From the outside, it looked like picking a fight you didn’t need. Inside Datadog, the logic was simple: customers didn’t want a pile of tools. They wanted one unified platform that connected what the application was doing to what the infrastructure was doing. If Datadog didn’t fill that gap, someone else would—and that someone else would have a wedge straight into Datadog’s customer base.

So Datadog shipped an APM beta in 2016. Early on, it didn’t match every bell and whistle of the specialist tools. But it had something those tools couldn’t: it snapped directly into the rest of Datadog. Users could follow a slow request from the application layer down into the infrastructure it was running on, and actually see the chain of cause and effect—service to database to network to host—in one place.

That same year, the company’s momentum showed up on the balance sheet. In January 2016, Datadog raised a $94.5 million Series D led by ICONIQ Capital—one of the largest funding rounds for a New York company that year. They moved into the New York Times Building. The team was doubling.

Five years earlier, Pomel had been talking about surviving on credit cards. Now Datadog was starting to look less like a scrappy monitoring tool and more like the platform company it was becoming.

V. The Platform Expansion Play (2017–2019)

By 2017, Datadog’s growth had hit escape velocity. It had more than 4,000 paying customers, passed $100 million in annual recurring revenue, and grown to roughly 600 employees worldwide. But the more important milestone was strategic: the original bet was working. Enterprises were moving to the cloud, and the old, fragmented way of monitoring systems wasn’t keeping up.

Pomel and Lê-Quôc didn’t want Datadog to be “infrastructure monitoring plus a few add-ons.” They wanted it to become the system engineers lived in—a true observability platform that could bring together metrics, traces, logs, and, eventually, security. The kind of place you could go with any question—What’s broken? Where? Why?—and actually get an answer.

To get there, Datadog built fast internally and started buying selectively. The biggest move came in September 2017, when it acquired Logmatic.io, a Paris-based log management company.

Logs were the missing third pillar. Metrics tell you what’s happening. Traces show you how a request moves through a distributed system. Logs give you the gritty, line-by-line story of what your software actually said as it ran. With Logmatic, Datadog gained both the underlying technology and the team to turn log management into a first-class product on the platform.

It also carried a bit of symbolism: a New York company founded by two French engineers buying a French startup to accelerate its next act. Datadog was building globally, and it would source the best pieces wherever it found them.

With each product added, the business model got stronger. A team would start with infrastructure monitoring. Then they’d add APM. Then logs. Each step made Datadog stickier, expanded spend inside the same customer, and reduced the appeal of stitching together a patchwork of point solutions. The land-and-expand motion that worked in the early days now had more surface area to expand into.

The growth numbers reflected that momentum. Revenue surged in 2018 and again in 2019, even as the base got larger—an unusual combination in SaaS, where scale usually forces growth rates to slow.

In 2019, Datadog pushed observability outward, closer to the user. It launched Synthetics, which tests applications by simulating user behavior, and Real User Monitoring (RUM), which captures what actual users experience in web and mobile apps. It wasn’t enough to know that servers were healthy; engineering teams needed to know whether customers were having a good day or a terrible one.

By mid-2019, Datadog looked like an IPO-ready company: real scale, real momentum, and a widening platform. And Pomel’s view was that the opportunity ahead was still bigger than any single acquisition price could reflect. The cloud transition wasn’t over. If anything, it was just getting started.

Which set up the decision that would define the next chapter: take the sure thing—a multibillion-dollar buyout—or step onto the public stage and keep building.

VI. The IPO & Cisco Drama (2019)

In early 2019, Datadog started doing the quiet work that precedes a loud moment: preparing to go public. Bankers were hired, confidential paperwork went to the SEC, and the company began lining up the investor story it would take on the road. The mood in cloud software was optimistic. A wave of high-profile tech IPOs was either happening or about to.

Then Cisco showed up.

Cisco had been watching the cloud era redraw the map. The world was shifting from on-prem infrastructure to AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud, while Cisco’s core business was still anchored in networking hardware—profitable, but not exactly a growth rocket. The company had been pushing hard into software and services, and Datadog offered something rare: a credible, category-leading position in cloud observability, instantly.

According to Bloomberg, Cisco offered “significantly higher than $7 billion” for Datadog. That was real money—especially in context. Datadog’s initial IPO range of $19–21 per share implied a valuation of roughly $5–6 billion. Cisco was effectively saying: forget the market’s first draft, we’ll pay you a premium to skip the whole thing.

It wasn’t even a new move for Cisco. Just two years earlier, in January 2017, Cisco had bought AppDynamics—one of the best-known APM companies—for $3.7 billion in cash. The timing was the point: the deal was announced one day before AppDynamics’ planned IPO. At its expected IPO price, AppDynamics would have been valued around $1.7 billion. Cisco paid more than double, and AppDynamics took the certainty.

So why didn’t the same playbook work again?

Because Olivier Pomel didn’t see Datadog as a company reaching an endpoint. He saw one hitting its stride. Growth was accelerating, not slowing. The cloud transition was still early innings, and Datadog sat right where modern infrastructure was getting more complex, more distributed, and harder to understand. Selling then would mean cashing out before the compounding really began.

Pomel and the board turned Cisco down.

Datadog kept going with the IPO. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, and Credit Suisse led the offering. Demand built. The company raised the range from $19–22 to $24–26. And then, when the final price landed at $27 per share—above even that revised range—Datadog went public at an $8.7 billion valuation.

On September 19, 2019, Datadog began trading on the Nasdaq under the ticker DDOG. The stock opened at $40.50, well above the IPO price. It finished the day at $37.55—up 39%—pushing the market cap toward $10 billion.

In other words: the “no” looked smart immediately.

And the longer arc made it even more consequential. AppDynamics took the guaranteed $3.7 billion and stepped off the field. Datadog chose to stay in the game. Within two years of the IPO, Datadog’s market capitalization would exceed $60 billion—more than eight times Cisco’s offer. One decision, one moment, and a very different kind of outcome.

VII. Post-IPO Hypergrowth & Product Velocity (2019–2024)

The years after Datadog’s IPO made Wall Street look like it had been modeling the wrong company.

When Datadog went public, analysts broadly expected it to be a solid cloud software story—growing, but within the usual bounds. Consensus estimates pegged 2021 revenue at around $610 million. Datadog delivered $1.3 billion. That isn’t “beat and raise.” That’s a reset of expectations.

A few forces collided to make that happen.

First, the cloud migration didn’t just continue—it accelerated. And after COVID pushed the world into remote work and digital-first operations, even the most conservative enterprises moved faster. Workloads that had been “we’ll get to it next year” became “we need this live now.” Every one of those migrations created a new problem: if your infrastructure is changing constantly, you need a way to see what’s happening constantly. Datadog was built for exactly that reality.

Second, the platform expansion play started compounding. Datadog’s customers rarely stayed single-product customers for long. A team might come in for infrastructure monitoring, then add APM, then logs, then synthetics and security—because it all connected, and because the marginal cost of adopting the next module was low once Datadog was already embedded. The proof was in the retention. Datadog’s dollar-based net retention rate consistently stayed above 130%, meaning the average customer spent about 30% more each year before Datadog even counted a single new logo.

Third, the company moved with relentless product velocity. Datadog wasn’t just polishing dashboards—it was widening the definition of what “observability” meant. In 2020, it launched security monitoring and cloud SIEM. Over the next few years came error tracking, continuous profiler, database monitoring, CI/CD visibility, and a steady drumbeat of new features that made the platform broader and harder to replace.

And Datadog didn’t rely only on internal builds. It kept buying to fill gaps and pull forward the roadmap. In 2020, it acquired Undefined Labs to strengthen developer workflow capabilities. In 2021, it bought Timber Technologies (the team behind Vector), Sqreen (application security), and Ozcode (live debugging). The next year brought Seekret (API observability), HDIV (security), CoScreen (collaboration), and Cloudcraft (infrastructure visualization). In 2023, Datadog added Codiga (static code analysis) and Actiondesk (spreadsheet integration). The pattern was consistent: each deal either plugged a missing product surface area or let Datadog ship something years sooner than it could have otherwise.

By 2024, the results looked like a platform business firing on all cylinders. Datadog reported $2.68 billion in annual revenue, up 26% year over year. It served roughly 30,000 organizations, including 45% of the Fortune 500. At the high end, 462 customers were spending more than $1 million annually, and 3,610 customers were spending more than $100,000—about double the number in that $100K+ tier just three years earlier.

One of the clearest signs of how efficiently Datadog was growing showed up in its cost structure. In the early days, like most enterprise software companies, sales and marketing dominated spending. By 2024, Datadog was spending more on research and development than on sales and marketing. That’s the product-led growth model in its purest form: when adoption spreads through engineers, you can put more fuel into building than into persuading.

The team scaled to match. From about 600 employees in 2017, Datadog grew to more than 5,200 by 2023 and roughly 6,500 by the end of 2024—many of them engineers, building the next wave of observability and security tooling.

And in the background, the public market scoreboard kept updating. Datadog’s stock eventually reached an all-time high above $199 in November 2025. The bet Pomel made in 2019—walking away from Cisco’s offer to stay independent—didn’t just work. It became the decision that unlocked everything that followed.

VIII. Business Model & Unit Economics Deep Dive

To understand why Datadog has so often earned a premium in the public markets, you have to look at how the machine actually makes money. On the surface, it’s a straightforward SaaS subscription. In practice, it’s a usage-driven tollbooth on modern software.

Datadog doesn’t primarily charge per seat. It charges for what customers monitor and how much they observe: the number of hosts under infrastructure monitoring, the volume of logs ingested, and the number of APM spans processed for tracing. That detail matters. Seat-based tools eventually run into a ceiling—your headcount only grows so fast. Datadog’s model scales with activity. As a customer’s systems grow, as their traffic rises, as their architecture gets more distributed and chatty, Datadog naturally becomes more valuable—and the bill rises with it.

The economics of delivering that are strong. Datadog’s gross margins have consistently come in around the mid-70s, even at scale. That’s a big deal because it means incremental revenue drops through with real efficiency, giving the company room to keep investing in product while still throwing off meaningful cash.

And it does throw off cash. In 2024, Datadog generated $871 million in operating cash flow and $775 million in free cash flow. It also held about $4.4 billion in cash and equivalents—more than just a safety net. That’s flexibility: for acquisitions, for new bets, or simply for staying aggressive through whatever macro cycle comes next.

Retention is the other pillar. Datadog’s dollar-based net revenue retention has stayed above 110%, which means the existing customer base expands over time even after accounting for churn and contraction. That’s the land-and-expand model expressed in one number. The longer customers stay, the more products they add, the more data they send, and the more central Datadog becomes to how they run software day to day.

There’s also a clean purity to the model that’s easy to miss: Datadog generates no professional services revenue. None. No army of consultants padding out deployments. No bespoke customization as a profit center. The product has to stand on its own—deployable and useful without weeks of hand-holding—which keeps margins cleaner and reinforces the product-led growth engine.

Put it all together—usage-based expansion, high gross margins, strong retention, and a product-only delivery model—and you get the kind of unit economics investors love: customers get cheaper to acquire relative to the lifetime value they generate, and cohorts compound over time without Datadog needing to scale sales and marketing at the same rate. That’s what “premium multiple” actually buys you here: not just growth, but durable, high-quality growth.

IX. Competition & Market Dynamics

Datadog plays in what the industry now calls “observability”: infrastructure monitoring, APM, logs, security, and—more recently—tools for making sense of AI systems in production. It’s a big, fast-growing market, expanding as software stacks get more distributed, more cloud-native, and harder to understand in real time.

And it’s crowded. Datadog doesn’t just compete with one company. It competes with entire eras of tooling.

First, there are the legacy monitoring giants—CA Technologies, HP, and IBM—built for an on-prem world of long-lived servers and predictable environments. Many large enterprises still have these tools, especially where cloud migration is incomplete. But that installed base has been slowly leaking as the center of gravity moves to cloud architectures their products weren’t designed for.

Next are the pure-play observability companies that grew up alongside Datadog. New Relic got an early lead in APM and later widened into a broader platform. Dynatrace, spun out of Compuware, pushed hard on automation and “AI-powered” monitoring. Elastic extended from search into observability and security. All of them have real strengths and real customers. The difference is that none has matched Datadog’s particular combination of breadth across products, speed of expansion, and momentum in the market.

Then come the hyperscalers—the cloud providers themselves. AWS has CloudWatch, Azure has Monitor, and Google Cloud has its Operations Suite (formerly Stackdriver). These products are often the default choice for basic monitoring because they’re already there, tightly integrated, and cheap enough to feel free at small scale. The catch is the lock-in: they’re best inside their own cloud. As more companies run multi-cloud setups—or mix public cloud with on-prem—the value of a vendor-agnostic layer goes up. That’s the lane Datadog has built its business around.

There’s also Splunk, the longtime king of log analytics. Splunk built a huge business on on-prem software for searching and analyzing machine data, then had to fight the hard fight of transitioning to cloud delivery and modern pricing. Datadog’s log management rode the cloud-native wave and took share with the teams moving fastest. And in one of those storybook industry plot twists, Cisco acquired Splunk in September 2024 for $28 billion—the same Cisco that tried to buy Datadog five years earlier.

Finally, the frontier: AI-native monitoring. As companies put machine learning models and large language models into real production workflows, they suddenly need answers to a new set of questions—about drift, cost, latency, hallucinations, and failure modes that don’t look like traditional bugs. Datadog has been pushing into this with offerings like LLM Observability and AI Agent Monitoring, announced at its 2024 and 2025 developer conferences.

So why has Datadog held up so well in a market this competitive?

A big part of the advantage is architectural and experiential: one unified platform instead of a patchwork of point solutions. That makes expansion easier—customers can start with one product and add others without rebuilding everything from scratch. Product-led growth keeps distribution efficient; high switching costs keep retention high. Once teams have wired Datadog into dashboards, alerts, incident workflows, and muscle memory, ripping it out is not a weekend project. And the company’s product velocity forces competitors into a constant game of catch-up.

But none of this is guaranteed forever. Cloud providers could get meaningfully better. A new entrant could change the architecture in a way that makes today’s platform model look dated. And if the macro environment turns, enterprises can and do rationalize spend—even on tools they consider essential.

Observability is a must-have. It’s also a knife fight.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Datadog’s path from maxed-out credit cards to a roughly $45 billion public company isn’t just a great tech story. It’s a clean case study in what works—over and over—in modern enterprise software.

Product-led growth as a competitive advantage: Datadog didn’t win by perfecting the classic enterprise sales script. It won by making adoption easy for the people who actually feel the pain first: engineers. A developer could spin it up on a small service, get value fast, and then pull the rest of the organization in behind them. That bottoms-up motion is efficient, it creates real internal champions instead of reluctant users, and it compounds through word-of-mouth in a way paid marketing can’t fake.

Timing the market: Pomel and Lê-Quôc built for cloud infrastructure in 2010, when plenty of smart people still treated AWS like a toy. They weren’t early because they were lucky—they were early because they’d lived the dev-versus-ops friction firsthand and could see exactly how the cloud would amplify it. By the time the cloud migration became non-negotiable for enterprises, Datadog had already spent years learning from customers and hardening the product. That kind of head start is brutally difficult to claw back.

The power of saying no: Turning down Cisco’s more-than-$7 billion offer in 2019 wasn’t bravado—it was conviction about the size of the opportunity. Most founders would choose certainty: a huge check and a clean ending. Pomel chose the messy, high-variance path of the public markets because he believed Datadog could be worth far more than any strategic buyer would pay. The takeaway isn’t “never sell.” It’s that you have to know what game you’re in, and what your company can become, before you decide where the story ends.

Building a platform, not just a product: Datadog kept widening its footprint—moving from infrastructure monitoring into APM, logs, security, and AI observability. Each expansion made the product more valuable on its own and harder to replace in practice. Point solutions can be excellent, but platforms are what become systems of record. Datadog didn’t just ride the observability wave; it used the platform approach to capture more of the stack than any single-product competitor could.

Capital efficiency: Datadog raised meaningful venture capital, but it carried early-day discipline forward. The scarcity at the beginning forced focus: build what customers need, ship quickly, and avoid business lines that don’t scale well, like professional services. By the time it reached the IPO, it was edging toward GAAP profitability while still growing fast—an unusually strong signal that the fundamentals were real.

Founder-led advantage: Olivier Pomel has stayed CEO more than fifteen years after founding. That kind of continuity is rare, and it matters. It keeps strategy consistent, it preserves technical credibility with the market, and it reflects a leadership team that understands the customer’s reality because they built the product to solve their own.

XI. Analysis: Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

The optimistic view on Datadog comes down to two big ideas: it has real staying power, and it’s riding waves that are still rolling in.

Market leadership that’s starting to look like a moat. If you use Hamilton Helmer’s “7 Powers” lens, Datadog checks a few important boxes. Switching costs are very real: leaving Datadog doesn’t just mean replacing a vendor, it means rebuilding dashboards, alerts, integrations, and incident workflows that teams rely on every day. That’s not a quick weekend migration. There’s also a scale flywheel at work. The more integrations Datadog supports, the more attractive it becomes to customers. The more customers it has, the more it can justify building even more integrations. And then there’s brand: for many cloud-native teams, Datadog has become the default name you think of when you think “observability.”

Digital transformation still has a long runway. Even after years of cloud migration, a lot of enterprise workloads remain on-prem. As those workloads gradually move to the cloud—over many years, not many quarters—the need for modern observability keeps expanding right alongside them. Datadog doesn’t need to invent a new problem to solve; it just needs to keep being the best platform for a problem that’s getting bigger.

AI could be the next growth engine. As companies put large language models, AI agents, and ML pipelines into production, they inherit a new class of operational headaches: monitoring behavior, debugging failures, managing latency and cost, and understanding outputs that don’t fail like traditional software. Datadog has already started planting flags here with LLM Observability and AI Agent Monitoring, giving it a shot at becoming the default platform for AI operations the same way it became the default for cloud operations.

A financial fortress that buys options. With about $4.4 billion in cash, roughly 32% free cash flow margins, and consistent profitability, Datadog has the ability to keep investing through down cycles, make strategic acquisitions, and out-iterate smaller competitors even when markets get choppy.

The Bear Case

The cautious view is less about whether Datadog is a good company and more about how much perfection the stock price demands—and how many strong opponents are on the field.

Premium valuation leaves little room for mistakes. Datadog trades at a meaningful premium to even other high-quality software companies. A price-to-sales multiple around the high teens and triple-digit P/E ratios effectively price in years of strong execution. If growth slows, if a quarter disappoints, or if the macro environment shifts, the multiple can compress fast—even if the underlying business is still healthy.

Competition is coming from every direction at once. The hyperscalers keep improving their native tools and could bundle them more aggressively. Splunk, now owned by Cisco, has deep enterprise relationships and a massive footprint. Startups can attack narrow observability niches and chip away at parts of the stack. And Datadog’s own success has made it a target—competitors know exactly where the money is.

Enterprise spend is real, and it’s not immune to cycles. Datadog serves tens of thousands of customers, but a large share of revenue comes from big enterprises. In downturns, “cost optimization” becomes a mandate, and that often includes scrutinizing SaaS spend—including tools teams consider essential.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for Datadog itself, two metrics do most of the work.

Dollar-based net revenue retention. This is the cleanest signal of whether customers are expanding usage over time. Sustained retention above 120% suggests the platform is still compounding inside accounts. A slide toward 110% or below would be a warning sign that expansion is slowing or customers are tightening usage.

Large customer growth. Watch the count of customers spending more than $1 million a year, and the broader cohort spending more than $100,000. Growth in those tiers is evidence that Datadog is moving upmarket and that the platform strategy is working. If those cohorts stall, it raises the question every great SaaS company eventually faces: where is the ceiling?

XII. Epilogue & Looking Forward

On February 13, 2025, Datadog reported its fourth-quarter and full-year 2024 results, and they looked like the continuation of a very specific pattern: scale, then grow anyway. Revenue for the year came in at $2.68 billion, up 26% from the prior year. Management also guided to about $3.17–$3.20 billion in 2025 revenue—pointing to 20%+ growth even as the company pushed toward the next billion.

On the earnings call, CEO Olivier Pomel didn’t frame this as “we’re mature now.” He framed it as “we’re still shipping.” “We delivered hundreds of new features and capabilities throughout the year,” he said, calling out investment in AI observability, security, and developer tools. The subtext mattered: Datadog might be fifteen years old, but it still wanted to behave like the hungriest product team in the room.

The next frontier is AI, and Datadog has been trying to get there early—just like it did with cloud infrastructure in 2010. At DASH 2024, the company’s annual developer conference, it announced general availability of LLM Observability and previewed tools for monitoring AI agents. At DASH 2025, it unveiled AI Agent Monitoring, LLM Experiments, and an AI Agents Console. Then, in February 2026, it announced an integration with Google’s Agent Development Kit to enable automatic instrumentation of agentic AI systems.

That positioning isn’t a side quest. AI workloads are messier than traditional software: behavior can be probabilistic, outputs can be wrong in strange ways, and failure modes include things engineers didn’t used to debug—like hallucinations, shifting performance, and volatile latency. Datadog is betting that “observability for AI” will become just as non-negotiable as observability for the cloud, and it wants to be the platform teams open when an AI system starts acting weird at 2 a.m.

Meanwhile, the core platform keeps widening. Kubernetes Active Remediation aims to help teams automatically fix issues in containerized environments. Cloud SIEM brings security monitoring into the same workflow as metrics, traces, and logs. GPU monitoring speaks directly to the operational reality of running AI workloads on specialized hardware. None of these products is the story by itself; together, they’re the strategy: expand the surface area, connect the data, and make the platform harder to live without.

From maxed-out credit cards in 2010 to a roughly $45 billion company, Datadog’s arc reads like a playbook for building something durable: see a shift early, build for the practitioners, make adoption frictionless, expand into adjacent categories, and keep the product moving fast enough that the market never catches you.

And for founders wrestling with the sell-versus-IPO decision, Datadog is a reminder of what “no” can buy. The public path is harder and less forgiving, and plenty of companies that reject big offers stumble later. But if you have real conviction in the size of the market—and the ability to execute through cycles—the upside can be far bigger than any acquirer is willing to pay.

Pomel and Alexis Lê-Quôc didn’t just build a successful company. They helped shape how modern software gets operated. If the cloud era made observability mandatory, the AI era may raise the bar again. Datadog is clearly planning to be there for that, too.

XIII. Recent News & Developments

January 2025: Datadog acquired Quickwit, a French startup behind an open-source, cloud-native search engine built for logs. It was a very on-brand deal: pull a proven team and modern indexing tech into the platform to make high-volume log analytics faster and more scalable.

May 2025 and April 2025: Datadog also made two acquisitions that signaled just how wide its definition of “observability” was getting. It acquired Metaplane, a data observability company focused on catching data quality issues, and Eppo, a feature management and experimentation platform. Together, they pushed Datadog further into data operations and product analytics—places where “what’s broken?” isn’t a server, it’s a pipeline or an experiment.

DASH 2025 Announcements: At its annual developer conference, Datadog leaned hard into the next wave: AI in production. It unveiled AI Agent Monitoring to track AI agent behavior in live environments, LLM Experiments to test and evaluate model performance, and an AI Agents Console to manage autonomous systems. It also launched GPU Monitoring for multi-cloud environments and GPU-as-a-Service platforms, including Coreweave and Lambda Labs.

February 2026: Datadog announced an integration with Google’s Agent Development Kit (ADK) for LLM Observability. The goal was simple: make it easier to instrument agentic systems automatically, so teams can see decision paths, tool calls, token usage, and latency—without a bunch of bespoke plumbing.

Leadership Continuity: Through all of it, the company kept the same core leadership structure: Olivier Pomel as CEO and Alexis Lê-Quôc as CTO, continuing the founder-led model that has defined Datadog since 2010.

XIV. Links & References

Primary Sources: - Datadog S-1 Filing (September 2019) — SEC EDGAR - Datadog Investor Relations: investors.datadoghq.com - Datadog Engineering Blog: datadoghq.com/blog/engineering/

Founder Interviews & Talks: - Matt Turck: “Building a $12B Public Company” (mattturck.com/pomel) - RTP Global: “Building Datadog Against the Odds” - SaaStr: “Who is Olivier Pomel, CEO of SaaS and Cloud Leader Datadog” - Alexis Lê-Quôc talks and appearances (AWS re:Invent, Monitorama, DevOpsDays)

News Coverage: - Bloomberg: “Cisco Offered $7 Billion-Plus for Datadog” (September 2019) - CNBC: “Datadog pops 39% in Nasdaq debut” (September 2019) - TechCrunch: “Cisco snaps up AppDynamics for $3.7B” (January 2017)

Industry Analysis: - CB Insights: “Datadog IPO Investor Analysis” - MacroTrends: Datadog financial data and charts - Tracxn: Datadog acquisitions database

Product & Technical: - DASH Conference keynotes (2024, 2025) - Datadog Documentation: docs.datadoghq.com - VideoLAN history and VLC origins

Books on DevOps & Cloud Infrastructure: - The Phoenix Project by Gene Kim, Kevin Behr, and George Spafford - Accelerate by Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim - Site Reliability Engineering by the Google SRE Team

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music