Deere & Company: The Green Revolution - From Steel Plows to Smart Farms

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

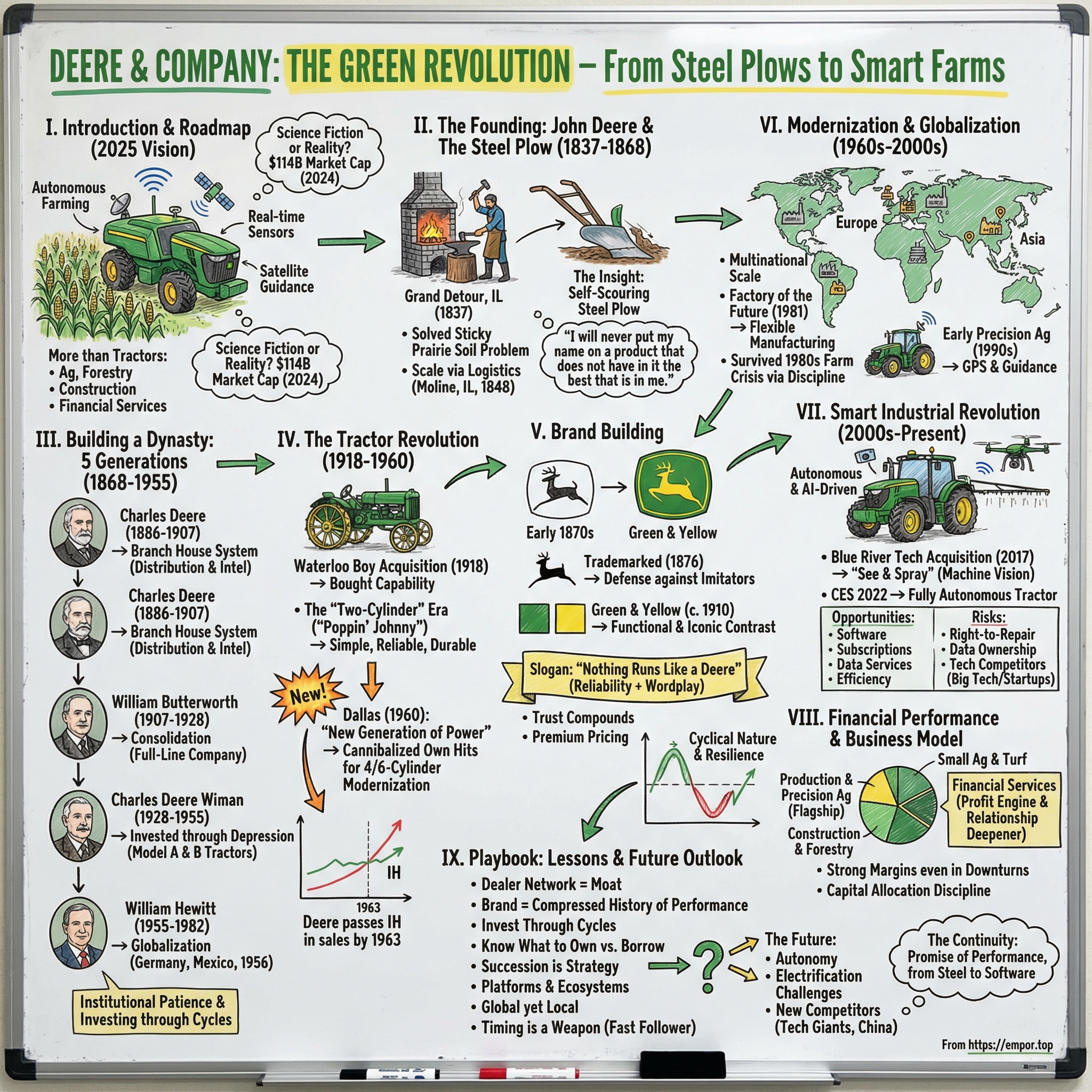

Picture a vast Iowa cornfield at dawn in the summer of 2025. A massive green-and-yellow combine glides through the rows with eerie precision—except the cab is empty. Sensors read the crop in real time. Software adjusts on the fly. Satellite guidance keeps the machine locked to its line, accurate to within a couple of centimeters. It looks like science fiction. It’s also the end of a story that started with a single blacksmith, a hot forge, and one deceptively simple insight about how to cut into prairie soil.

Deere & Company sits at a rare intersection of American history, industrial scale, and cutting-edge technology. With a market cap around $114 billion as of late 2024, it’s one of the world’s most valuable industrial companies. And it’s far more than “tractor company.” Deere builds agricultural machinery, forestry and construction equipment, diesel engines, and it runs a sizable financial services arm that helps move iron off dealer lots and onto farms.

So how did a Vermont blacksmith’s steel plow—hammered out in an Illinois frontier town in 1837—turn into a global manufacturing and technology empire?

That’s the question at the heart of this story. Because the Deere saga isn’t just farming nostalgia. It’s westward expansion and American industrialization. It’s a family business that somehow executed succession across five generations without falling apart. It’s the brutal rhythm of innovation cycles—where the winners keep reinventing themselves, and the also-rans get left in the dust. And it’s the constant tension between tradition and transformation: the things you can’t change without breaking the brand, and the things you must change to survive.

Deere is especially compelling right now because it’s in the middle of a new kind of inflection point. The company that once won by making a better plow and then a better tractor is now wrestling with software, data, subscriptions, and autonomy. The competitive set is shifting too. Yes, Deere still battles the usual suspects like AGCO and CNH Industrial. But increasingly, it’s also staring down technology-first challengers—Silicon Valley ventures and Chinese manufacturers—who think about farming the way software companies think about logistics.

This isn’t just a story about machines. It’s about how a brand becomes shorthand for an industry, how a business survives booms and busts that would wipe out weaker players, and what happens when a century-old model—dealers, parts, service, financing—collides with the digital world. We’ll follow the decisions that made Deere one of America’s great industrial franchises, the moments it nearly lost its way, and the opportunities and risks that define what comes next.

II. The Founding Story: John Deere & The Steel Plow (1837-1868)

The winter of 1836 into 1837 hit Grand Detour, Illinois hard. It was a tiny frontier outpost sitting exposed on the prairie, with winds that had nothing to slow them down. In the middle of it was a small blacksmith shop—hot, loud, and essential—where a 32-year-old newcomer from Vermont named John Deere spent his days shoeing horses, fixing broken tools, and keeping a young settlement functioning.

He hadn’t planned on becoming a legend. He was just trying to start over.

John Deere was born on February 7, 1804, in Rutland, Vermont. When he was four, his father was lost at sea. His mother raised the family in poverty, and by seventeen John was apprenticed to a blacksmith, grinding through four years of hard, precise work that taught him how metal behaves—how it bends, how it breaks, how it can be coaxed into shape. Back in Vermont he built a reputation for craftsmanship, especially for tools like hay forks and shovels—pieces farmers actually trusted because they held up.

But the mid-1830s were rough in New England. Work dried up. Money got tight. So Deere did what so many Americans did: he aimed west.

He arrived in Grand Detour in November 1836, leaving his wife and four children behind until he could get established. The town needed a blacksmith badly, and Deere quickly found plenty of paying jobs. But what he really found was a recurring, maddening failure—one that every farmer complained about and no one could fix.

Illinois prairie soil was fertile, yes. It was also heavy, sticky, and relentless. The cast-iron plows that worked fine in the sandy soils back East were useless here. The black earth clung to the iron moldboard, building up until farmers had to stop every few yards and scrape it clean. Plowing that should have been routine turned into a punishing slog. Some settlers simply gave up, packed up, and moved on.

Deere watched this and saw the problem differently. The farmers weren’t failing. The tool was.

Cast iron was rough. Roughness meant friction. Friction meant soil stuck. So Deere asked a blacksmith’s question: what if the surface were smooth enough—and shaped well enough—that the soil couldn’t grab on in the first place?

The story of what happened next has been told so many times it’s taken on a mythic shine. The commonly repeated version is that Deere got his hands on a broken steel saw blade—some accounts tie it to the local sawmill run by Leonard Andrus—and brought it back to his shop. He heated it, hammered it, and polished it until it gleamed. But the secret wasn’t just the material. It was the geometry. Deere shaped the moldboard so the soil would roll across it in a continuous flow, scouring the surface clean as it worked.

In 1837, he finished the first one and tested it on the farm of Lewis Crandall. The difference was immediate. The plow cut cleanly through the prairie ground, and the soil didn’t cling—it slid. For farmers used to stopping constantly to scrape their plows, it must have felt like someone had quietly rewritten the rules of the landscape.

And on the frontier, results traveled faster than advertising. Word spread. Deere went from being the guy who repaired tools to the guy who made the one tool everyone suddenly needed.

Scaling, at first, meant improvising. Good steel wasn’t exactly abundant on the prairie. Deere sourced what he could—more blades, more scrap—and eventually brought in better material, including steel imported from England. By 1841 he was building roughly 75 to 100 plows a year. Demand kept climbing. By 1843, production had risen to about 400.

At the center of it all was a simple standard Deere refused to compromise on. Later, he would sum it up in a line that became the company’s moral North Star: “I will never put my name on a product that does not have in it the best that is in me.” On the frontier, your name mattered. If your tool failed at the wrong moment, a farmer didn’t just lose time—he could lose the season. Deere built his business around that reality.

Then came the move that showed he wasn’t only a great mechanic—he was becoming a serious operator.

In 1848, Deere dissolved his partnership with Leonard Andrus and relocated to Moline, Illinois. It wasn’t a romantic choice; it was a supply-chain choice. Moline sat on the Mississippi River, with water power available for manufacturing and river transport for shipping finished goods. And the Rock Island Railroad was pushing west. Grand Detour couldn’t compete with that kind of access.

Moline let Deere buy better inputs, ship farther, and produce at a different scale. With improved logistics—and with higher-quality steel coming in from places like Pittsburgh and, again, England—the business expanded rapidly. By the mid-1850s, the operation was producing more than 10,000 plows a year. Deere even imported rolled steel directly from England for plow moldboards, a bold decision for the time that improved consistency and performance.

Even as the factory grew, Deere kept his ear close to the ground. He traveled, talked with farmers and dealers, listened to what broke and what didn’t, and iterated constantly. It wasn’t “customer service” in the modern sense—it was survival-driven product development. The frontier changed fast. The implement that won last year could be obsolete next year. Deere’s advantage was that he kept learning faster than the landscape shifted.

In 1868, the business incorporated as Deere & Company. By then, the steel plow wasn’t just a successful product. It had become an enabling technology for the American Midwest. It helped turn prairie soil from a barrier into an asset—and in doing so, it accelerated the agricultural transformation that made the region a global breadbasket.

And for the rest of this story, the founding era matters because it set the template. Start with a real farmer problem. Solve it with better engineering. Protect the brand by refusing to cut corners. And when the bottleneck is logistics or supply, don’t complain—move. That playbook began in a one-room blacksmith shop in Grand Detour. Everything that comes later is, in some way, an elaboration of it.

III. Building a Dynasty: Five Generations of Family Leadership (1868-1955)

By the time John Deere died on May 17, 1886, at age 82, the handoff had already happened. His son, Charles Deere, had effectively been running the business for years—first as vice president, then formally as president after his father’s death. And with that transition, Deere entered a rare chapter in American industry: nearly a century of family leadership that didn’t just preserve what John Deere built, but repeatedly retooled it for the world as it changed.

Charles Deere was not his father. John was the craftsman-inventor, obsessed with how metal met soil. Charles was an organizer, a builder of systems. Born in 1837—the same year the first commercially successful steel plow appeared—he grew up alongside the company itself, watching it expand from a blacksmith’s shop into a real manufacturing operation. He understood something that would become a Deere hallmark: great products are necessary, but distribution and information decide who wins.

His signature move was the branch house system. In 1869, Charles established the first one in Kansas City. It wasn’t just a sales office. The branch house became a regional nerve center: it handled sales, parts, and credit—and, most importantly, it brought intelligence back to Moline. What was breaking in the field? What were competitors pushing? What did farmers actually want next?

That feedback loop was rocket fuel. While rivals often depended on looser networks of independent dealers, Deere built a direct channel for real-world learning at scale. And over time, that system became its own competitive advantage—hard to see from the outside, even harder to replicate. By the time Charles died in 1907, Deere was firmly established as one of the top implement makers in America, with a distribution machine that made the factory in Moline more powerful every year.

The next leader brought a different kind of upgrade: structure. William Butterworth—Charles’s son-in-law, married to Charles’s daughter Katherine—became president in 1907. Trained as an attorney, Butterworth looked at the farm equipment landscape and saw fragmentation everywhere: many small manufacturers, narrow product lines, duplicated costs, and farmers forced to piece together equipment from different brands.

Butterworth’s answer was consolidation with a purpose. Over his tenure, he brought eleven factories and twenty-five sales organizations under one roof. This wasn’t empire-building for its own sake. He was shaping Deere into a full-line company—one that could meet a farmer’s needs across the operation, not just in one category. Out of that restructuring came something recognizable as the modern Deere & Company: broader product offerings, tighter operations, and a business that was no longer defined by plows alone.

Then, in 1928, leadership passed to Charles Deere Wiman, John Deere’s great-grandson. The timing was brutal. Within a year, the stock market crashed. The Great Depression followed, and agriculture—already under pressure after World War I—fell into a deep, grinding crisis. Farm incomes collapsed. Farmers stopped buying equipment. Competitors either failed outright or scrambled into mergers to survive.

Wiman’s response revealed the kind of long-term posture that the Deere family had been quietly building for decades. Instead of gutting investment in new product development, he kept research and design moving. The logic was simple: the downturn would end someday, and when it did, the company that showed up with better machines would take the field.

In 1934, Deere introduced the Model “A” tractor. In 1935, it followed with the Model “B.” These weren’t minor refreshes. They were tractors designed to fit real farm work: adjustable wheel treads for different row spacings, hydraulic implement lifts, better fuel efficiency. Farmers loved them for the same reason they’d loved Deere plows almost a century earlier—reliability that showed up in the dirt, not on a brochure. The Model B stayed in production until 1952, a long run that says almost everything about how well it landed.

And the timing couldn’t have been better. As agricultural prices recovered and farmers could finally invest again, Deere wasn’t scrambling to catch up. It had new machines ready—machines that helped it gain share while others were still trying to modernize Depression-era lineups.

In 1955, after Wiman’s sudden death, the presidency went to William Hewitt, another family connection through marriage—his wife was Wiman’s daughter. Hewitt’s challenge wasn’t just product or distribution. It was geography. By the mid-1950s, North America mattered enormously—but it wasn’t enough. If Deere wanted to keep growing and reduce dependence on the cyclical U.S. farm economy, it needed to become international in a real way.

Hewitt moved fast. In 1956, Deere bought a share in a tractor company in Mannheim, Germany—an immediate foothold in European manufacturing. That same year, it acquired land in Monterrey, Mexico, signaling that Latin America wasn’t a side project. These weren’t timid experiments. They were commitments—capital, management attention, and a deliberate push toward multinational scale.

Zoom out, and you can see the pattern that made this dynasty unusually effective. Each generation brought a different strength matched to a different era: Charles built the distribution-and-intelligence engine; Butterworth built the integrated company; Wiman invested through the crash and emerged with iconic products; Hewitt began the global expansion that would define the second half of the 20th century.

And that leaves Deere with something that doesn’t show up on a spec sheet: institutional patience. A habit of investing through cycles, protecting the brand, and thinking in decades instead of quarters. That long-term wiring—laid down across five generations—would become essential as Deere moved from steel and gears into an age of electronics, software, and data.

IV. The Tractor Revolution: Waterloo Boy to Industry Leadership (1918-1960)

Deere’s steel plow helped break the prairie. But by the early 1900s, the next great bottleneck on the farm wasn’t cutting the soil. It was power.

Horses were expensive to feed and slow to scale. Steam engines had proved you could mechanize heavy work, but they were bulky, temperamental, and dangerous. Then the internal combustion engine arrived and made the promise real: smaller machines, easier handling, more reliable day-to-day power. Tractors weren’t a niche product anymore. They were the next platform for agriculture. And every implement maker knew it.

Deere knew it too—and it tried to build its own way in. The company experimented with tractor designs, including the Dain All-Wheel-Drive created by board member Joseph Dain. It was innovative, but the broader effort was slow, uncertain, and late for a market that was moving fast.

So Deere did what it had done before when time and logistics mattered: it bought capability.

On March 14, 1918, Deere & Company paid $2,350,000 to acquire the Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company in Waterloo, Iowa. That price tag didn’t just buy factories, employees, and inventory. It bought a proven tractor already in the field, already earning trust: the Waterloo Boy.

The Waterloo Boy wasn’t glamorous. It was simple, with an exposed engine and a workmanlike design. It ran on kerosene and looked almost primitive next to some competitors’ machines. But it had the only feature that really mattered on a farm: it worked. Farmers found it reliable, practical, and within reach. And overnight, Deere had what internal development hadn’t delivered—a production-ready tractor, a manufacturing base, and engineers who had already learned the hard lessons of building machines that survive real field conditions.

The results came quickly. Within three years of the acquisition, Deere had produced more than 5,000 tractors. Waterloo wasn’t just a plant anymore—it became Deere’s tractor headquarters, a role it would hold for more than a century.

What followed turned into a Deere signature: the “two-cylinder era.” While rivals pushed four- and six-cylinder designs, Deere committed to a simpler two-cylinder engine. The sound was unmistakable—slow, rhythmic, a steady pop-pop-pop that earned the tractors the nickname “Poppin’ Johnny.” And the affection was earned. The two-cylinder machines were easier to maintain, fuel-efficient, and famously durable. Simpler parts meant cheaper repairs, and on a farm, that’s not a feature—it’s peace of mind.

That design choice also did something deeper than improve engineering. It anchored loyalty. Farmers learned these machines, built routines around them, taught their kids to fix them. In agriculture, brand preference isn’t a soft concept. It’s often generational.

Then World War II arrived and pulled American manufacturing into a different gear. Deere’s commercial business was disrupted, but its factories stayed busy: military tractors, transmissions for M3 tanks, ammunition, aircraft parts. The war forced scale, discipline, and new production techniques—capabilities that didn’t disappear when peace returned.

After the war, American agriculture entered a boom, and the equipment business turned into a knife fight. International Harvester was the heavyweight—the industry leader with massive scale and deep distribution, born from the 1902 merger of competing harvester companies. For years, IH looked untouchable.

Deere’s answer was to bet against its own success.

Throughout the 1950s, Deere invested heavily in R&D on a new tractor line that would abandon the beloved two-cylinder architecture. It was an enormous risk. The two-cylinder tractors weren’t just profitable; they were the heart of Deere’s identity in the field. Replacing them meant asking loyal customers to fall in love with something new—and asking the company to retool its core franchise on designs that hadn’t yet proven themselves at scale.

The reveal came on August 30, 1960, in Dallas, Texas. Deere invited thousands of dealers and their families to what it billed as “Deere Day in Dallas.” On the surface it felt like a county fair—entertainment, barbecue, a big celebration. But the real point was theater: a dramatic unveiling of what Deere called the “New Generation of Power.”

Deere rolled out four new tractor models with modern four- and six-cylinder engines, fresh styling, meaningfully more power, and features that signaled a new era—power steering, improved hydraulics, a more contemporary operator experience. This wasn’t a tweak. It was Deere publicly retiring an icon and declaring a new standard.

Farmers bought in. The New Generation tractors landed as both more capable and still unmistakably Deere: strong, reliable, built for work. Competitors didn’t just lose a product cycle—they lost momentum. And in 1963, only three years after Dallas, Deere passed International Harvester in total sales to become the world’s leading farm equipment manufacturer.

That moment matters because it explains something investors and competitors still grapple with today: Deere’s leadership wasn’t an accident of history. It was built through a pattern of hard choices—acquire when speed matters, commit to simplicity when it wins loyalty, and, when the technology curve bends, be willing to cannibalize your own hits before someone else does it for you.

Those same instincts—the ones forged at Waterloo and proven in Dallas—are the ones Deere would need again as the next revolution arrived: not just more horsepower, but information, automation, and software.

V. Brand Building: The Leaping Deer, Green & Yellow, and "Nothing Runs Like a Deere"

Walk into almost any rural community in America—and, increasingly, farming regions around the world—and you’ll see it: John Deere green. It’s on combines and caps, on dealer signs and lunchbox stickers, on jackets worn by people who’ve never owned a piece of Deere equipment in their lives. The leaping deer shows up everywhere, from kids’ toys to premium merchandise. That kind of ubiquity isn’t an accident. It’s the result of more than a century of deliberate brand building—starting, fittingly, not from a marketing brainstorm, but from a fight.

The leaping deer began appearing in Deere imagery in the 1870s. The visual pun on the name was obvious, and early ads played with different versions of a deer in motion. But what pushed Deere to get serious about the logo wasn’t creativity—it was defense. As Deere equipment spread across the Midwest, copycats followed. Competitors and imitators used similar deer images to ride Deere’s reputation, often on products that didn’t hold up in the field. For a company built on trust, that was an existential threat.

So in 1876, Deere registered the trademark. In doing so, the company wasn’t just protecting an image—it was defining an identity worth protecting. Over time, the logo evolved through multiple iterations, each one clearer and more recognizable than the last. The modern mark—introduced in the late twentieth century—captures what Deere wants to project: a clean, confident silhouette, mid-leap, unmistakable at a glance.

Then came the other element that made Deere impossible to miss: the colors.

Around 1910, Deere began adopting the green-and-yellow scheme that would become as iconic as the logo itself. And, like so many Deere decisions, it started with practicality. Green made intuitive sense for agriculture, echoing fields and growing crops, but it also worked visually in the environment where the machines lived. Yellow, used for wheels and accents, provided contrast and visibility in the low-light hours when farmers so often work—early mornings, late evenings, dusty harvest days.

What began as functional choices turned into brand signatures. Competitors could copy features. Colors were harder. International Harvester, Deere’s great rival for much of the twentieth century, was firmly red. And that simple visual divide—green versus red—became a cultural one. In many farming communities, your equipment color wasn’t just a preference. It was a statement, sometimes bordering on a family creed.

The slogan tied it all together. “Nothing Runs Like a Deere” worked because it did two jobs at once. The deer/Deere wordplay made it sticky, but the deeper message was the one farmers cared about: reliability. On a farm, timing is unforgiving. Planting and harvest windows are narrow. Weather doesn’t negotiate. If the machine doesn’t run when it needs to, the consequences aren’t an inconvenience—they’re financial. The line promised the thing Deere had been selling since the first steel plow: dependability when it matters most.

Over the decades, Deere’s brand seeped into rural life in a way most companies can only dream about. Deere shows up at county fairs and community parades. Vintage tractors are restored like classic cars and sold at premiums to collectors. The company’s presence runs through agricultural education and youth programs, embedding the brand into the next generation long before anyone buys their first tractor.

And as Deere expanded globally, it carried that identity with it. The green and yellow stayed consistent, giving instant recognition from North America to Europe to Latin America. The local contexts changed—different crops, different farming rhythms, different traditions—but the visual language didn’t. Deere learned how to be both global and familiar: one brand, tuned to many fields.

For investors, this kind of brand strength is a moat that doesn’t always show up cleanly in a spreadsheet. In farm equipment, trust compounds. Farmers who’ve had good experiences—machines that start, parts that arrive, dealers who can fix problems fast—tend to stay loyal for decades. That loyalty supports pricing power, too. Deere has often been able to sell at a premium because customers believe they’re buying fewer breakdowns, faster service, and more certainty in the dirt.

But brand strength also raises the stakes of change. As Deere’s machines become increasingly software-driven, “reliability” isn’t just cast iron and hydraulics anymore—it’s sensors, updates, connectivity, and code. And controversies like right-to-repair don’t just create regulatory headaches; they threaten the company’s farmer-first image. The challenge now is to modernize without snapping the emotional bond that green-and-yellow has spent more than a century earning.

VI. Modernization & Globalization (1960s-2000s)

The Dallas unveiling in 1960 was more than a breakout product launch. It was Deere telling its dealers, its competitors, and its own employees: we’re willing to rebuild the core of this company in public. And that set the tone for what came next—four decades of expansion, reinvention, and a few gut-check moments that could’ve broken a less disciplined business.

First, Deere had to modernize itself, not just its tractors. In 1958, the company incorporated John Deere–Delaware Company, and later that year merged it with the older Deere & Company and its subsidiaries. On paper, it sounds like corporate cleanup. In practice, it gave Deere a simpler structure that made it easier to move capital, manage a growing set of businesses, and execute the international ambitions the company was already leaning into.

With William Hewitt at the helm through the 1960s and into the 1970s, Deere pushed outward. The Mannheim foothold in Germany grew into real European capability. A factory in France came online. Manufacturing extended into places like Argentina and South Africa. Joint ventures followed in Asia. Over time, Deere stopped being an American manufacturer that happened to sell overseas and became something harder: a multinational operator with production and execution spread across continents.

Those moves weren’t happening in a vacuum. Agriculture itself was changing fast. The 1960s and 1970s rewarded scale. Machines got bigger and more capable. Combines could cover more acres per hour. Farms consolidated as operators who could finance modern equipment expanded, while those who couldn’t were squeezed out. Deere made an explicit bet on this new reality: build more powerful, more sophisticated equipment for larger, more professional operations. The product roadmap and the economics of farming were moving in the same direction.

Then Deere doubled down on how it built the machines, too. In 1981, the company opened what it called the “factory of the future” in Iowa—an investment of more than $1.5 billion that leaned heavily on computers, robots, and flexible manufacturing. The pitch was simple and bold: make production adaptable, so Deere could switch what it built without painful, expensive retooling—and respond faster when demand shifted.

And then demand didn’t just shift. It collapsed.

The early 1980s brought a brutal farm crisis. Commodity prices fell. Land values dropped. Farmers who had borrowed against high land prices to buy equipment suddenly found themselves upside down. Bankruptcies spread. Across the industry, equipment sales cratered. Deere had just poured an enormous amount of capital into new manufacturing capacity—exactly the kind of bet that looks brilliant in a boom and terrifying in a downturn.

The pressure showed up everywhere. Production slowed. Employment fell sharply. After decades of steady profitability, Deere recorded losses. The easy move would have been to retreat—freeze technology spending, protect cash, wait it out. Instead, Deere followed a familiar playbook. Much like Wiman had during the Depression, management held onto the idea that surviving the cycle wasn’t enough; you had to come out of it stronger. So the company largely stayed the course on the manufacturing investments, betting that being ready on the other side would matter more than looking conservative in the moment.

Recovery took time. But as conditions improved through the late 1980s and into the 1990s, that manufacturing capability became an advantage competitors couldn’t quickly copy. What had looked like a poorly timed splurge became a long-lived cost and flexibility edge.

And while Deere was reinventing factories, a new kind of technology was creeping onto the farm. In the 1990s, GPS—built for military use—started finding practical agricultural applications. Deere recognized the implication early: if machines could know where they were with tight accuracy, farmers could plant more precisely, apply fertilizer more intelligently, and avoid wasting time and inputs by overlapping passes.

Deere invested heavily in precision agriculture, building internal capabilities and acquiring specialized firms. By the early 2000s, guidance systems were becoming a meaningful part of the Deere experience—machines that could hold a line across a field with minimal steering input. It wasn’t just operator comfort. It translated into real dollars: less wasted seed and fertilizer, fewer mistakes, and better consistency.

Over time, the workforce footprint reflected the shift to global scale and modern productivity. By 2018, Deere employed about 67,000 people worldwide, with roughly half in the United States and Canada—evidence of international expansion, but also of how much output modern plants could produce with fewer hands than earlier eras.

From 1960 to 2000, Deere became something new: not just the leading farm equipment maker, but a diversified, global, technology-forward industrial company. The bets were enormous—international manufacturing, next-generation factories, and early precision tech—and at several points the timing could have been catastrophic. That it wasn’t came down to a mix of strong execution, financial resilience, and a leadership culture that was willing to invest through pain.

And it set the stage for what comes next. Because once you’ve taught your organization to think globally, build flexibly, and compete on technology—not just steel—the next step is almost inevitable: the shift from machines that run on horsepower to machines that run on software.

VII. The Smart Industrial Revolution: Precision Agriculture & Technology (2000s-Present)

In a test field outside Deere’s headquarters in Moline, a tractor makes its passes with no one in the cab. Cameras watch the ground. Software spots weeds and classifies what it sees in real time. Then the sprayer does something that would’ve sounded ridiculous in the two-cylinder era: it treats only the weeds, not the whole field—cutting chemical use by as much as 80 percent versus blanket spraying. The machine doesn’t care if it’s midnight or noon. It doesn’t get tired. It just keeps going. This is the future Deere is chasing—and, increasingly, the future it’s shipping.

For nearly two centuries, Deere’s edge was mechanical: better metallurgy, better designs, better uptime when timing mattered. That still counts. But the center of gravity has moved. More and more of the value now sits in the digital layer—the sensors that capture what’s happening in the field, the algorithms that interpret it, and the automated decisions that turn insight into action.

You can see that evolution in how Deere organizes itself today. The company operates through four segments. Production and Precision Agriculture is the flagship: large tractors, combines, cotton pickers, sprayers, and soil-prep equipment—the heavy iron that modern farms run on, increasingly bundled with guidance, sensing, and automation. Small Agriculture and Turf serves smaller farms and the consumer market for lawn and garden equipment. Construction and Forestry covers equipment for those industries. And Financial Services sits alongside them, helping customers buy and lease equipment, and supporting warranties and related services.

The push into autonomy and AI didn’t happen by accident. A key acceleration came in 2017, when Deere acquired Blue River Technology for about $305 million. Blue River brought machine vision and machine learning into the company’s core, not as a bolt-on, but as a new discipline inside an old industrial giant. The most visible result is See & Spray: systems that can distinguish crops from weeds on the move, applying herbicide only where it’s needed. With chemical costs rising, the savings can be meaningful—and it’s also a glimpse of where this goes next: machines that don’t just follow instructions, but perceive and decide.

Deere made that ambition explicit at CES 2022, when it unveiled its first fully autonomous tractor. The setting mattered. CES isn’t an ag trade show; it’s where consumer tech and the broader software world gathers. Deere was signaling that it doesn’t see itself competing only with other equipment makers anymore. The tractor uses cameras, GPS, and AI to navigate and do work that used to require a skilled operator—turning labor, one of farming’s most stubborn constraints, into a problem software might actually shrink.

But this shift has also created a new kind of friction with Deere’s core customers. Modern machines are packed with electronic systems, and those systems are controlled by proprietary software. When something breaks, farmers can run into a very different reality than the one they grew up with: repairs that used to be handled in the shed now require authorized dealers and proprietary diagnostic tools. Error codes replace obvious mechanical failure. And the feeling, for many operators, is that the product they bought isn’t fully theirs to fix.

That tension has turned into the right-to-repair fight—a reputational and regulatory headache Deere is still learning to manage. Deere’s position is that software controls help protect intellectual property and maintain safety, and that unapproved repairs could create performance issues or liability. Critics—farmer groups, and organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation—argue that the tradition of self-repair is part of farming culture and economics, and that digital locks are less about safety and more about control.

It hasn’t stayed a cultural argument. It’s become a legislative one. In February 2022, the U.S. Senate introduced a bill aimed at protecting farmers’ ability to repair their own equipment, and multiple states have explored similar measures. Meanwhile, some farmers have reportedly used Ukrainian versions of hacked software to work around Deere’s restrictions—an outcome that underscores how demand for repair access will find supply, whether Deere likes the channel or not.

And repairs aren’t the only flashpoint. Data is the next one.

Today’s equipment generates a constant stream of information: yield maps, soil and field condition readings, and machine performance data. That data can improve decisions and outcomes—but it also raises a question that didn’t exist when Deere sold mostly steel and hydraulics: who owns the farm’s operating data, who gets to access it, and what else can be done with it?

Farmers worry that sensitive operational details could be aggregated or shared in ways that disadvantage them—whether with commodity market participants, landlords, or competitors. Deere has put forward data principles and privacy policies to address these concerns, but skepticism remains. Becoming a data-and-software platform requires a different kind of trust than being “the company that builds equipment that doesn’t quit,” and Deere is still working through what that relationship should look like.

Meanwhile, the competitive set is widening. Deere’s traditional rivals—AGCO and CNH Industrial—are pursuing their own precision strategies. But the bigger question is whether technology companies, with deep software benches and massive balance sheets, decide to go from “ag initiatives” to direct competition. Google, Amazon, and Microsoft have all shown interest in agriculture in different ways. Venture-backed startups are building autonomy systems from scratch, without the legacy constraints Deere has to navigate—like existing dealer relationships, existing customer expectations, and a brand built on mechanical serviceability.

For investors, this era is both the opportunity and the risk in one package. The upside is straightforward: there’s enormous global acreage that hasn’t adopted advanced precision tools, and Deere believes fewer than 20 percent of global crop agriculture uses precision technologies today. If that adoption curve steepens, Deere can sell not just machines, but capabilities—and over time, potentially more recurring revenue through software subscriptions and data services that help smooth the cycle of equipment sales.

The downside is just as real. This transformation demands sustained investment with uncertain payoff. Right-to-repair outcomes could force broader access to tools and software. Technology-native competitors could move faster than a century-old industrial can. And the shift from selling machines to licensing software changes the emotional contract with customers—one that, if mishandled, could weaken the brand loyalty Deere spent generations earning.

VIII. Financial Performance & Business Model Evolution

If you want to understand Deere as a business—not just as a brand—you start with a truth every farmer already knows: this is a cyclical world. When farm income is strong, equipment moves fast. When prices fall and uncertainty rises, purchases get delayed, lots fill up, and everyone waits for the weather to change.

Deere’s recent numbers show that pattern in motion. In fiscal 2024, the company generated $51.7 billion in revenue, down from $61.3 billion in 2023—about a 15.6 percent decline. And 2023 had been the opposite story: up 16.5 percent over 2022, which itself was nearly 20 percent higher than 2021. That kind of swing isn’t a one-off. It’s the rhythm of the equipment business.

You could see the downturn showing up clearly in fiscal Q3 2024. Worldwide net sales and revenues fell 17 percent year over year to $13.15 billion. Over the first nine months of the fiscal year, the decline was 11 percent. With lower commodity prices and a shakier economic backdrop, farmers pulled back. Dealers ended up sitting on more inventory. The cycle had turned, just like it always does.

What makes Deere different is how well it tends to hold up when the cycle goes against it. Even with revenue down, profitability stayed strong by industrial standards. Net income for fiscal 2024 was forecast at roughly $7.0 billion. Production & Precision Agriculture—Deere’s core segment—brought in $5.1 billion in net sales in Q3, down 25 percent from the prior year, yet still delivered a 22.8 percent operating margin. In other words: fewer machines sold, but the business didn’t fall apart.

That resilience doesn’t happen by accident. Deere has spent decades building an operating system designed to absorb shocks—adjusting production without letting costs spiral, managing suppliers and capacity, and making footprint and workforce decisions with the next downturn in mind. And it’s been deliberately shifting toward higher-value offerings in precision agriculture, where the economics can be better than steel alone.

Then there’s the piece of Deere most people underestimate: Financial Services.

This segment is effectively a quiet profit engine sitting next to the factories. It finances sales and leases for customers and dealers, offers extended warranties, and supports retail revolving charge accounts. It’s not as visible as a new tractor launch, but it matters because it helps get equipment purchased in the first place—especially when customers are cash-constrained—and it produces income streams that can last well after a machine leaves the lot.

It also deepens relationships. Farmers who finance with Deere tend to come back to the same ecosystem for the next purchase. And in downturns, leasing structures and residual values can help soften the blow versus a pure one-time sales model.

All of this—scale, profitability, and a business model that’s more than manufacturing—is why Deere sits among America’s largest companies, ranking 84th on the 2022 Fortune 500. It’s not just big. It’s structurally built to endure a category that regularly punishes the unprepared.

That cyclicality shows up in how Deere allocates capital. In good years, it doesn’t behave like the boom will last forever. The company maintains financial flexibility for the inevitable downturn, returns capital through dividends and share repurchases without overcommitting, and tends to favor targeted, bolt-on acquisitions—often in precision agriculture and software—rather than betting the company on transformative deals that could look reckless when the cycle turns.

And for anyone trying to read Deere’s financials like a narrative, the headline revenue figure is just the beginning. You watch dealer inventory levels for clues about what’s coming next. You pay attention to the balance between equipment sales and the parts-and-services stream that signals what’s happening in the field. And in the financing business, you keep an eye on the judgment calls—like residual value estimates on leased equipment—that can meaningfully shape reported results.

Finally, Deere isn’t a one-segment story anymore. Construction and Forestry has different demand drivers than row-crop agriculture. Small Agriculture and Turf tends to be steadier, even if margins differ. And geographic spread helps ensure that not every region hits the same trough at the same time.

Put it all together, and Deere’s financial story is exactly what you’d expect from an iconic industrial franchise tied to the farm economy: volatile at the top line, disciplined underneath, and increasingly shaped by a platform model—equipment, parts and service, precision tech, and financing—that’s designed to keep the business standing when the weather inevitably changes.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Nearly two centuries of Deere history leave behind something more useful than nostalgia: a set of repeatable patterns for building durable advantage, surviving brutal cycles, and navigating technology shifts without losing your identity.

Start with the moat most people underestimate: the dealer network.

In plenty of industries, “distribution” means a checkout button or a few resellers. In farm equipment, distribution is a relationship business conducted under extreme time pressure. When something breaks during planting or harvest, the farmer doesn’t need a hotline. They need parts, a technician, and a fix—fast. Deere’s dealer network has been built around exactly that reality, with partnerships that often span generations. Dealer families sell and service Deere equipment for decades, and farming families often buy from the same people across decades too.

That network compounds advantages in a few ways. It’s local service and parts availability when timing matters most. It’s credit—sometimes based on personal knowledge and trust that a purely transactional lender wouldn’t touch. And it’s information. Since Charles Deere’s first branch house, Deere has treated the field as its lab. Dealers are the sensor network: what’s breaking, what competitors are pushing, what farmers are asking for next. For a challenger, copying the machines is hard. Copying decades of embedded relationships is harder. And doing it fast is close to impossible.

Second: brand still matters, even when the product looks like a commodity.

From a distance, tractors can seem interchangeable—steel, engines, tires, horsepower ratings. In theory, price should win. In reality, Deere has long earned pricing power because the brand stands for something farmers can feel: reliability, resale value, service, and the belief that the machine will run when the window is open and the weather is cooperating. That’s the lesson. In industrial markets, brand isn’t decoration. It’s a compressed history of performance, and it changes the buying decision even for practical customers spending serious money.

Third: cycles don’t just punish you. They reveal whether you’ve built a real company.

Agriculture is cyclical by nature, and equipment is cyclical on top of that. When the downturn hits, the instinct is to slash spending and hide. Deere’s more durable pattern has been counter-cyclical: hold onto R&D momentum, keep modernizing manufacturing, and make sure the product lineup is strong when demand returns. That strategy only works if you’re disciplined when times are good—because the ability to invest in bad times is bought with restraint in good times.

Fourth: know what to own, and what to borrow.

Deere’s technology strategy is a constant negotiation between vertical integration and partnership. Some things are core and must be controlled—manufacturing expertise, the dealer channel, and key precision ag capabilities, often built in-house or acquired. Other layers make more sense to source—satellite positioning, cloud infrastructure, specialized components. Get the boundary wrong and you either drown in cost and complexity, or you give away the keys to critical capabilities.

Fifth: succession is strategy.

Deere’s five generations of family leadership gave it an unusual advantage: cultural continuity and long-term orientation. But it wasn’t continuity for continuity’s sake. Leadership changed as the world changed—distribution systems, consolidation, Depression-era product bets, postwar globalization. The broader lesson isn’t “family is better.” It’s that thoughtful succession, deliberate grooming, and values that outlast a single CEO can be a competitive edge.

Sixth: platforms didn’t start in Silicon Valley.

Deere’s modern business isn’t just about selling equipment. It’s equipment plus parts and service, plus precision agriculture tools, plus financing. When a farmer buys Deere, finances through John Deere Financial, services through Deere dealers, and adopts Deere’s precision systems, they’re not just buying a machine—they’re operating inside an ecosystem. That’s sticky. It creates multiple revenue streams and makes switching harder, even if a competitor offers a cheaper initial purchase.

Seventh: go global without losing the core.

Deere expanded around the world while keeping its identity consistent: the green and yellow, the leaping deer, the reputation for quality. But it didn’t try to sell the exact same machine everywhere. Different crops, field sizes, regulations, and farming practices demanded adaptation. The brand stayed stable; the execution localized. That balance—one identity, many realities—is what separates real global operators from exporters.

Finally: timing is a weapon.

Deere’s track record shows a consistent instinct about when to pioneer and when to follow. It didn’t invent the tractor category; it bought its way in with Waterloo. It wasn’t the first to experiment with precision agriculture; it pushed hard once the technology was ready to deliver real field value. It didn’t lead the autonomy narrative early; it moved decisively as the tech approached commercial practicality. In capital-intensive industries, being early can be a great way to be wrong expensively. Deere’s version of “fast follower” has often meant something more specific: wait until the value is real, then bring scale, distribution, and trust to make it inevitable.

Those are the lessons Deere keeps teaching, over and over: build the channel, earn trust, invest through cycles, choose your technology boundaries, and time your reinventions before the market forces them on you.

X. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The investment case for Deere & Company is a balancing act: on one side, a set of advantages that have compounded for generations; on the other, a handful of structural forces that could reshape what “winning” even looks like in farm equipment. Both are real.

Start with the bull case: precision agriculture is still early.

Even after decades of development, most estimates suggest precision agriculture is deployed on less than 20 percent of global crop acreage. That’s an enormous runway. And if adoption keeps expanding—pushed by higher input costs, labor scarcity, and the growing pressure to do more with less—Deere’s head start in hardware-plus-software should matter. Not just in selling machines, but in capturing the attach rates: guidance, sensing, automation, and the tools that turn equipment into a system.

Climate change, for all its disruption, can also reinforce this. More volatile weather, tighter water constraints, and yield pressure make precision less of a “nice to have” and more like insurance. A sprayer or applicator that can put the right amount of input in the right spot isn’t just efficient; it’s a way to protect margins in a world where mistakes get more expensive.

Then there’s farm consolidation. As farms scale up—a decades-long trend across geographies—the equipment they buy tends to scale up too. Bigger operations are more likely to invest in larger, more sophisticated machines, and they’re more likely to standardize around a platform that works across the whole fleet. That has historically played directly into Deere’s strengths, and there’s little evidence the consolidation trend is reversing.

The most important upside, though, is business model evolution. Equipment sales are cyclical and lumpy by nature; farmers buy when both need and cash flow line up. Software subscriptions and data services can smooth that pattern. If Deere can turn more of its technology stack into recurring relationships—services that persist between machine purchases—it doesn’t just add revenue. It potentially changes the risk profile of the entire company.

And underlying all of this is Deere’s embedded position. In much of North America, Deere isn’t just a vendor. It’s the default standard that dealers service, neighbors recommend, and resale markets reward. That kind of trust creates real pricing power and makes displacement slow and expensive for competitors.

If you run Deere through classic strategy frameworks, you can make the bull case feel even sturdier. Porter’s Five Forces generally looks favorable: farmers are numerous and fragmented, substitutes for mechanized agriculture are limited, scale helps manage suppliers, entry barriers are massive, and while competition is intense, the structure still supports profitability. Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers lines up too: brand power is obvious; switching costs are real when you factor in training, parts, and dealer relationships; process power shows up in manufacturing and operations; and network effects show up through the dealer system, where each strong dealer makes the overall ecosystem more valuable.

Now the bear case—and it isn’t just “the cycle might turn,” because the cycle always turns.

Deere will always be exposed to commodity prices and farm income volatility. When prices fall or uncertainty rises, farmers defer big purchases. Deere can manage capacity and costs, but it can’t repeal the underlying economics of agriculture.

Right-to-repair is a more existential kind of risk, because it strikes at how Deere’s modern system works. If regulation forces broader access to diagnostics, repair software, and tools, it could pressure dealer service economics. And more importantly, it could weaken Deere’s ability to control the software layer that increasingly defines the product experience. That’s not just a margin question; it’s a platform question.

Technology-first competitors are another source of discomfort. Companies born in software and autonomy don’t have to retrofit tech onto legacy architectures or navigate the expectations of a century-old dealer model. Deere has been aggressive here, but the risk is that the next leap in autonomy or AI comes from outside the traditional equipment ecosystem—and arrives faster than incumbents can comfortably absorb.

Then there’s geopolitics. Deere is a global manufacturer with global supply chains. Tariffs can hit exports, raise component costs, and inject uncertainty into farmers’ economics. The trade policy volatility of 2018–2019 is a reminder that this risk isn’t theoretical—and it can return.

Over the longer term, lower-cost competitors are a serious watch item, including Chinese manufacturers. In markets where Deere’s brand premium is less entrenched, “good enough” equipment with credible technology at a lower price can take share—especially when customers are more price-sensitive and dealer infrastructure is still developing.

Finally, there’s a paradox at the heart of Deere’s strategy: autonomy could weaken the moat that made Deere so durable in the first place. If machines get better at self-diagnosis, remote support, and modular maintenance, the local dealer’s role could shrink. The more software reduces the need for in-person service, the more the distribution advantage that historically protected Deere could be diluted.

So what should investors watch as this plays out?

A few indicators tend to matter early. Dealer inventory levels can signal demand conditions before they show up in reported results—when lots fill, pricing pressure usually follows. Precision agriculture attachment rates on new equipment show whether Deere is actually converting iron sales into technology adoption. And order trends for large agricultural machinery remain one of the clearest read-throughs on farmer confidence and future production needs.

XI. Epilogue & Future Outlook

The autonomous farming revolution isn’t a PowerPoint vision anymore. It’s happening, quietly, in real fields. Tractors can already handle certain operations without an operator in the cab. Machine vision can pick out individual weeds and treat them with precision. Analytics can flag problems before a breakdown turns planting week into a disaster. Deere has spent years—and billions—building toward this moment, and it’s positioned to be one of the companies that defines what “modern farming” looks like.

But being early, or even being excellent, doesn’t guarantee you win the next era.

One of the biggest transitions ahead is power. For more than a century, farm equipment has been built around diesel for a reason: it delivers sustained, heavy-duty work, far from towns, chargers, and easy refueling. Electric equipment offers real promise, and Deere has introduced electric options in some product lines. Still, the constraints that make electrification hard in cars can be even harder in agriculture. Farm machines need enormous energy density, long runtimes, and practical ways to recharge in places where the grid may be miles away.

Then there’s competition—especially from places Deere hasn’t historically had to worry about.

Technology giants remain a looming possibility. Alphabet has invested in agricultural automation. Amazon has the logistics and data DNA that could, in theory, be applied to farm operations. Microsoft has built cloud services for agriculture. They have software talent and financial firepower that can dwarf even a company as large as Deere. The open question is whether they’ll ever commit to the unglamorous part: building, selling, and supporting physical equipment in an industry that’s brutally seasonal, capital-intensive, and intolerant of downtime.

At the same time, Chinese manufacturers keep getting better. With domestic scale, growing technical capability, and government support, they’re steadily building toward parity with Western competitors in more categories. As China mechanizes further and its equipment makers move up the technology curve, export competition is likely to intensify—especially in markets where Deere’s heritage and dealer footprint don’t automatically translate into trust or pricing power.

So the strategic questions in front of Deere’s leadership are the kinds that define decades. How hard should it push autonomy, given regulatory uncertainty and the reality that customers adopt change at different speeds? What’s the right line between protecting proprietary software and meeting farmers’ demand for more repair access and control? How does Deere keep investing at the frontier while staying resilient through the next downturn in the ag cycle? And should it accelerate the shift with acquisitions, or rely more heavily on building the stack internally?

None of those have clean, obvious answers.

But if Deere’s history teaches anything, it’s that this company has been here before—at least in spirit. John Deere saw a practical problem and solved it with better engineering. During the Great Depression, the company kept investing and emerged with products farmers wanted. In 1960, it bet against its own two-cylinder icon and won with the New Generation. Over and over, Deere has shown a willingness to make uncomfortable calls before it’s forced to.

Which brings us back to the man himself. What would John Deere, the Vermont blacksmith, think of a company that now talks about autonomy and machine learning? He might not recognize the tools. But he’d recognize the mission: make farming work better, in the real world, under real constraints. And he’d probably understand the most important continuity of all—that putting your name on a product is a promise, whether the product is steel or software.

The leaping deer still jumps on hoods on every inhabited continent. The green and yellow still telegraph identity from a mile away. “Nothing Runs Like a Deere” still means something to people whose livelihoods depend on machines starting on the right day, in the right weather, with no excuses.

What Deere builds next—and how it navigates the tension between tradition and transformation—will decide whether this becomes the next great chapter of an American industrial franchise, or the moment it learns the hardest lesson in business: history helps, but it doesn’t protect you.

XII. Recent News & Developments

Agricultural equipment markets ran into a stiff headwind through 2024 and into 2025. Commodity prices cooled, farm margins tightened, and higher interest rates made big purchases harder to justify. Deere’s response was familiar from past down-cycles: pull back production, adjust the workforce, and protect the core. It was a reminder that for all the talk about software and autonomy, this is still a business that has to match factory output to a farm economy that can turn quickly.

At the same time, Deere kept pushing the digital stack forward. The company expanded technology partnerships that strengthen its precision agriculture offering—deeper work with satellite imagery providers, broader cloud computing relationships, and more third-party software integrated into its platform. The goal is clear: make Deere less of a “machine you buy every so often” and more of an operating system for the farm—something that delivers value between equipment cycles, not just at the moment of sale.

Right-to-repair didn’t fade into the background either. It stayed front and center in the regulatory debate, with multiple state legislatures considering bills that would require equipment to be more repairable, and ongoing federal attention as well. Deere has tried to walk a tightrope: acknowledging farmers’ need for access while arguing that software locks protect intellectual property and safety. Critics, though, continue to say the company’s movement hasn’t gone far enough—and that the current model still leaves farmers too dependent on authorized channels when time is the one thing they don’t have.

Globally, the picture was mixed. Strength in parts of Latin America helped cushion softer conditions in North America and Europe. Currency swings added noise to reported results, and trade policy remained an ever-present wildcard—one that can change the economics of both selling equipment and sourcing components faster than most operators would like.

Inside the factories, labor relations demanded careful handling as production slowdowns led to workforce adjustments. Deere’s relationships with unions representing production workers have often been workable, but not without friction. Downturns tend to test that balance: keeping the business flexible without damaging the trust and culture that make it possible to ramp back up when the cycle turns.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings and Investor Relations: If you want the unfiltered version of what Deere is doing and why, start with the primary sources. Deere & Company’s Annual Reports (Form 10‑K) and Quarterly Reports (Form 10‑Q), filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, lay out the financials, the risk factors, and management’s own explanation of what’s working, what’s not, and what’s changing. The company’s investor relations site adds the more “in-the-moment” layer: earnings decks, guidance updates, and strategic framing straight from leadership.

Historical Resources: For the long arc—from a frontier blacksmith shop to a global industrial giant—Deere’s own archives and company-sponsored histories provide the backbone. For a wider lens, the Smithsonian Institution’s agricultural equipment collections include historic implements that help place Deere in the broader mechanization story. And if you want history you can stand next to, regional museums in places like Moline and Waterloo offer grounded context on how the company grew where it grew, and why those locations mattered.

Industry Analysis: To understand Deere’s competitive environment, look beyond the company and into the ecosystem around it. Research from major investment banks and industry firms can help with market sizing, share shifts, and cycle expectations. Trade publications focused on agricultural equipment add another crucial angle: what dealers are seeing, what farmers are asking for, and how the market is behaving before it shows up in quarterly results.

Technology and Precision Agriculture: Deere’s future is increasingly tied to precision ag, autonomy, and the data layer around farming—topics covered both by traditional farm media and tech publications. For more rigorous work, there’s also a deep body of academic research on precision agriculture adoption, economics, and technical performance. It’s useful for separating what’s genuinely changing in farm operations from what’s still mostly marketing.

Regulatory and Policy: Right-to-repair and related regulatory shifts are moving targets, and coverage is spread across legal outlets, advocacy groups, and mainstream media. For the underlying economics that drive equipment demand—farm income, subsidies, crop prices, and policy impacts—government agencies and agricultural economics departments at major universities are often the most consistent sources.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music