D.R. Horton: Building America, One Home at a Time

I. Introduction & Cold Open

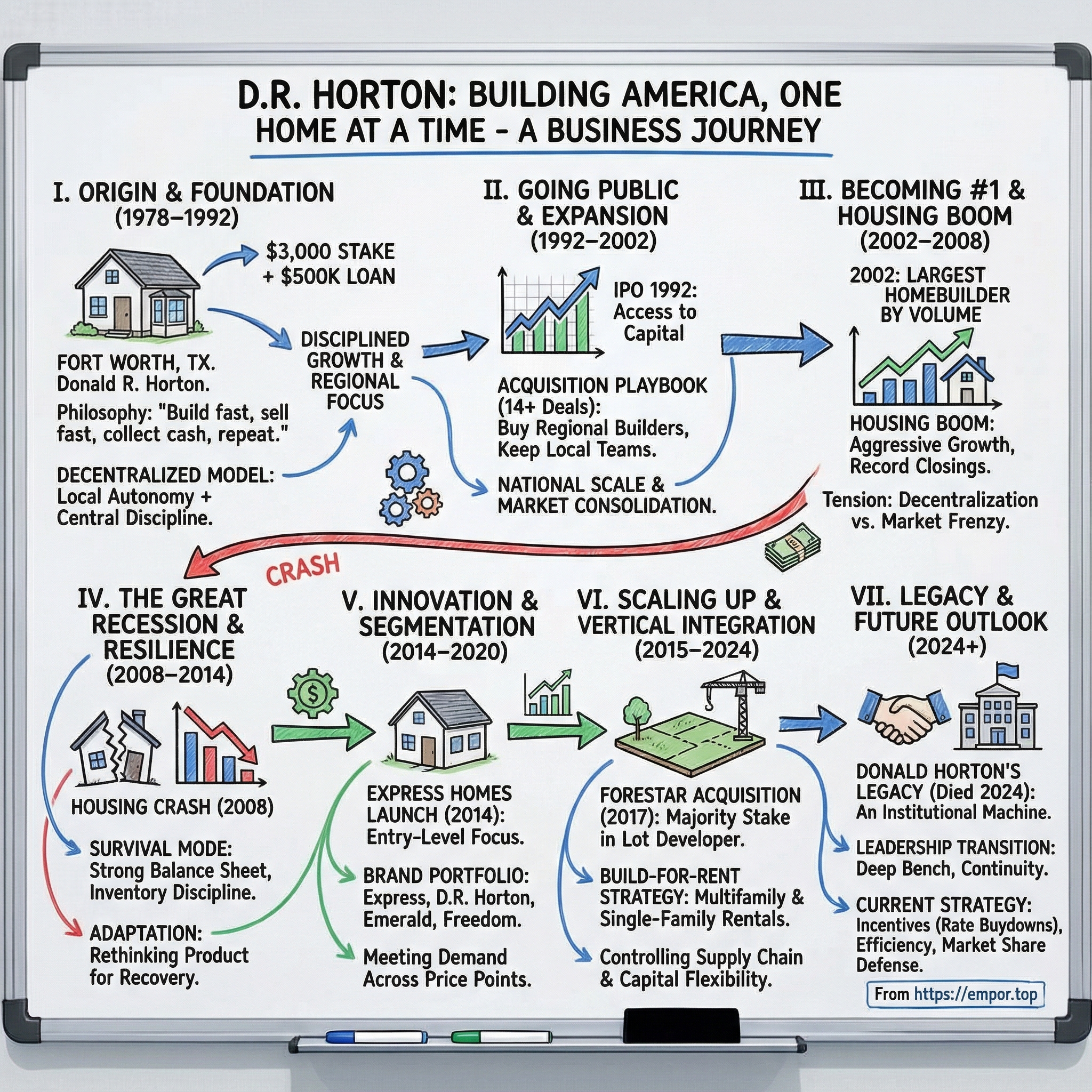

In the early hours of May 16, 2024, Donald R. Horton suffered a heart attack at his home in Fort Worth, Texas. He was 74. The man who had started with a $3,000 stake and a borrowed half-million dollars in 1978 left behind something almost impossible to build in a cyclical, brutally competitive business: America’s largest homebuilder, a Fortune 500 giant that had delivered more than a million homes and was generating nearly $37 billion a year in revenue.

Horton was the son of an Arkansas cattleman and part-time realtor. He didn’t inherit a construction empire. He built one—lot by lot, plan by plan—until D.R. Horton became a machine for turning empty dirt into neighborhoods, and lumber and drywall into the physical infrastructure of the American Dream.

Since 2002, D.R. Horton has held an unbroken reign as the largest homebuilder by volume in the United States. That’s more than two decades on top of an industry where the ground is always shifting—interest rates swing, land costs surge, labor comes and goes, and consumer confidence can evaporate in a quarter.

The company’s fiscal 2024 results show what that kind of dominance looks like in practice: $36.8 billion in revenue, $4.76 billion in net income, and 89,690 homes closed. Pre-tax profit margins held at 17.1%. Return on equity came in at nearly 20%. This wasn’t a legacy company drifting on reputation. It was a scaled operating system still running at full speed.

But the point of D.R. Horton isn’t just that it’s big. Plenty of companies reach scale and then collapse under their own complexity. The story here is how Horton got big—and how the company stayed big through booms, busts, the 2008 crash, and the most volatile interest-rate environment in forty years.

D.R. Horton built a decentralized operating model that gives local teams real autonomy—finding land, designing product, building, and selling—while the center enforces financial discipline and provides the muscle. It developed a portfolio of brands, from entry-level Express Homes to the luxury Emerald line, so it could meet buyers across the income spectrum without reinventing itself every cycle. And it created an acquisition playbook that absorbed regional builders into a national platform without killing the entrepreneurial energy that made them valuable in the first place.

By 2024, D.R. Horton operated in 125 markets across 36 states. It owned a majority stake in Forestar Group, one of the country’s largest residential lot developers—an advantage that helped with both vertical integration and lot supply. And it carried a balance sheet with roughly $3 billion in cash and a debt-to-capital ratio below 20%, giving it the flexibility to play offense when others are forced into defense.

This is the story of how a pharmacist-turned-homebuilder from a small Arkansas town built the most dominant force in American residential construction. It’s a story about operational discipline, strategic patience, and a relentless focus on giving customers what they can actually afford—often before the rest of the industry catches on.

Homebuilding doesn’t get the glamour of software or biotech. But what D.R. Horton has accomplished is extraordinary by any standard: surviving the worst housing crash in modern American history, executing acquisitions at a pace most private equity firms would envy, adjusting its product strategy to meet the market without sacrificing efficiency—and delivering consistent returns to shareholders while widening an already formidable moat.

And the lessons travel well. The importance of operational discipline. The power of patient, cycle-aware capital allocation. The advantage of meeting customers where they are instead of where you wish they’d be. D.R. Horton just happens to have written that playbook in concrete, framing nails, and front doors.

II. The Donald Horton Origin Story & Early Years (1978–1992)

Picture Marshall, Arkansas, in the 1960s: a small town in the north-central part of the state where everybody knows everybody, and the local economy runs on practical things—cattle, land, and relationships. Donald Ray Horton grew up watching his father work two jobs that, in a place like Marshall, were two sides of the same coin: cattleman and realtor. One taught you what things were worth. The other taught you how deals got done.

Don didn’t follow him into either line of work. He left Marshall, enrolled at the University of Central Arkansas, and set out to become a pharmacist. Later he transferred to the University of Oklahoma to finish his degree. Pharmacy was the sensible route: stable, respectable, predictable. No boom-and-bust cycles. No sleepless nights wondering if the market would turn before you got paid.

But predictability wasn’t what Horton was wired for.

By 1978, he had made his way to Fort Worth, Texas—and did the kind of thing that only looks obvious in hindsight. With about $3,000 of his own money and an empty lot, he walked into a bank and borrowed $500,000 to build his first house. No long résumé in construction. No multigenerational building business. Just a conviction that he could make it work and sell what he built.

What happened next was the first clue that Horton wasn’t just building houses. He was building a model.

During framing, a potential buyer stopped by and asked for a bay window. Horton didn’t run it up a chain of command or tell the buyer to take it or leave it. He said yes, and told them it would cost $500. The buyer agreed immediately. Horton later remembered the moment clearly: “I sold that house, then went back to the bank for the money to build two, then four, then eight more.”

That bay window was more than an upgrade. It revealed the opportunity Horton had found.

Homebuilding at the time tended to split into two camps. On one end were custom builders: anything you want, as long as you can pay for it and wait. On the other were production builders: efficient, standardized, and inflexible. Horton slid right into the middle. He could run the repeatable processes of a production shop, but still give buyers a sense of control—small changes, personal touches, the feeling that this wasn’t just another unit off a line.

And in housing, that feeling sells.

The early results came fast. He built 20 houses in 1979 and 80 in 1980. The next years kept stacking on top of each other, and throughout the 1980s the company essentially doubled in size year after year. That’s an extraordinary trajectory in any industry, but especially in one that lived through serious turbulence: the early-’80s recession and the real estate wreckage that hit Texas later in the decade.

Yet Horton kept growing. Quarter after quarter, revenue rose, profits rose, and the number of homes built rose.

A big part of the explanation was discipline. Horton didn’t treat land as a trophy or inventory as a badge of ambition. He treated both as working capital. Keep the cycle tight. Build efficiently. Sell quickly. Get paid. Repeat. While other builders got stuck with too much unsold inventory or overextended land positions when conditions turned, Horton stayed focused on turning capital into closed homes and cash as fast as he responsibly could.

For the first decade, D.R. Horton stayed close to home, operating in the Dallas–Fort Worth area. Horton knew the market block by block—the neighborhoods where families wanted to be, the schools that mattered, the price points that moved. But he also knew something else: staying regional meant staying exposed. Texas could be a rocket ship on the way up, and a trapdoor on the way down—often depending on forces no homebuilder could control.

By the late 1980s, Horton could see consolidation starting to reshape housing. Smaller builders were getting swallowed, starved, or wiped out. Capital was concentrating. Scale was beginning to matter more. And if you wanted to build something durable, you couldn’t bet the entire company on a single regional economy forever.

So the company began preparing to expand beyond Texas.

By 1991, as D.R. Horton incorporated in Delaware in preparation for going public, the business had already proven the hard part. It had a playbook that worked. It had survived downturns that killed competitors. And it had a founder who wasn’t chasing growth for the sake of growth—he was chasing velocity.

That operating philosophy became the company’s DNA. Horton cared intensely about how quickly capital moved through the system: from dirt to lumber, from lumber to a finished home, from a finished home to a closed sale, from a closed sale back to cash that could fund the next set of starts. Every day a house sat unsold was capital trapped. Every week a build dragged was risk creeping in.

So the organization oriented itself around disciplined speed. Standardized designs that subcontractors could execute predictably. Sales teams that understood momentum mattered. Processes that compressed timelines without turning quality into an afterthought.

And that’s why this early chapter matters. The “customization within standardization” insight shows up later in product strategy. The cash-flow obsession becomes a survival trait in the next crisis. The instinct for diversification and consolidation becomes a full-blown acquisition engine.

Before D.R. Horton became a national machine, it was one builder in Fort Worth learning, quickly, what actually makes homebuilding work.

III. Going Public & Early Expansion Strategy (1992–2002)

In the spring of 1992, D.R. Horton’s stock began trading on the New York Stock Exchange. For Don Horton, it was a line in the sand: the company was no longer just a fast-growing Fort Worth builder. It was now playing on a national stage—with quarterly expectations, public scrutiny, and, most importantly, a new kind of fuel.

The IPO gave Horton access to capital at a scale banks simply couldn’t match. And he didn’t raise it to let it sit. He raised it to expand—quickly, deliberately, and in a way that didn’t depend on guessing the next hot neighborhood in Dallas–Fort Worth.

What emerged in the mid-1990s was the acquisition playbook that would define the company for decades. Beginning in April 1994, D.R. Horton started buying regional builders—one after another. The names add up to a map of American homebuilding: Joe Miller Homes, Arappco Homes, Regency Homes, Trimark Communities, SGS Communities, Torrey Homes, C. Richard Dobson, Continental Homes, Mareli Development, RMP Properties, Cambridge Homes, and others. Fourteen acquisitions in the span of a few years, each one bringing what mattered most in this business: local land knowledge, subcontractor networks, relationships with sellers and municipalities, and teams who already knew how to operate in their market.

The defining deal of the decade came in 1997 with Continental Homes. D.R. Horton paid $305 million and assumed $278 million in debt to buy one of the country’s premier builders, with real presence in fast-growing Western and Sunbelt markets and a strong reputation for quality.

But the real value wasn’t just in the balance sheet. It was in what the deal compressed. Building that footprint organically would have meant years of buying lots, learning municipal processes, recruiting talent, earning the trust of subcontractors, and fighting incumbents on their home turf. Instead, Horton got operating divisions, management, and market share in one move. The acquisition turned what could have been a decade-long slog into an instant platform.

Continental also changed the way the industry viewed D.R. Horton. This wasn’t a regional builder dabbling in expansion. It was a consolidator with the appetite—and the operational competence—to absorb meaningful players and keep them producing. For founder-led regional builders, it created a credible exit: sell to Horton, get paid fairly, and keep building under a stronger umbrella instead of watching your business get squeezed by bigger competitors and cost inflation.

And that’s where Horton’s approach differed from the typical roll-up. Management put it plainly at the time:

"Our acquisition strategy is simple: We want to be the number one builder in every market we serve. The way to accomplish this is to grow with the best and give them the tools and resources to achieve more. We've been the acquisition leader for a couple of simple reasons: We do our homework and we allow those acquired to run their own business and continue to be successful."

They weren’t just saying that. D.R. Horton’s model was decentralized in the places where decentralization matters most. Local teams kept control of land decisions, product choices, construction execution, and sales—because those are market-by-market games. Meanwhile, the corporate center took over what the acquired leaders called “the job functions that aren’t fun”: lining up capital, running payroll, administering benefits, and handling the administrative weight that slows smaller operators down. The message was simple: keep doing what you’re great at, and we’ll remove the friction and give you more resources.

That combination—entrepreneurship at the edge, discipline at the center—solved the usual acquisition trap. Most big companies buy smaller ones and then bury them in process. D.R. Horton did the opposite: it tried to protect the speed and local instincts that made those builders valuable in the first place, while adding scale advantages they could never achieve on their own.

The results showed up quickly. By 1993, sales had reached $190 million, and D.R. Horton ranked as the 24th largest builder in the country. Over the rest of the decade, it vaulted into the top tier. The company expanded its product range along the way—moving beyond detached single-family homes into townhouses, condominiums, and a wider spread of price points, from entry-level to luxury.

Yes, the late-1990s housing environment helped. But D.R. Horton wasn’t just riding the market—it was gaining share. The acquisitions were sticking. The operating model was replicating. And the culture Horton built in Fort Worth—disciplined, aggressive, relentlessly focused on what sells—was traveling with the company into new regions and new teams.

By the time the 1990s closed, D.R. Horton had built the infrastructure for national scale: capital markets access, a repeatable M&A engine, operating divisions in multiple geographies, and enough management depth to run a much bigger machine. It was no longer a question of whether Horton could be national.

The question was whether it could be number one.

IV. Becoming America's Builder (2002–2008)

In 2002, D.R. Horton hit the milestone that would come to define it: it became the largest homebuilder by volume in the United States. And it didn’t just catch the crown in a good year and hand it back when the cycle turned. More than two decades later, it still hasn’t been knocked off the top spot.

That kind of staying power is rare in homebuilding, where leadership usually rotates with the market. But Horton held on through everything that came next: the biggest housing boom the country had ever seen, the crash that followed, and the whiplash of multiple cycles after that. The key point isn’t that the company got big. It’s that it built a system that kept it big.

The climb accelerated with more acquisitions in 2001 and 2002—Emerald Builders and Fortress Homes and Communities of Florida in 2001, then Schuler Homes in 2002. These weren’t random additions. They were the same playbook Horton had been refining since the mid-1990s: buy strong regional operators, keep their local decision-making intact, and give them the capital and back-office support to do more of what already worked.

Then came the boom.

From roughly 2003 through 2006, the housing market turned into a tailwind so strong it pulled almost everyone forward. Interest rates stayed low after the dot-com bust, credit got easier and easier to access, and home prices rose with a kind of momentum that made people believe the rise was permanent. In many markets, buying a home didn’t just feel like shelter—it felt like a trade.

D.R. Horton leaned in, as you’d expect the most aggressive scaled operator to do. It ramped volume, pushed into more communities, and rode the surge in demand. Closings climbed past 50,000 homes a year. Revenue swelled. Margins expanded as prices rose faster than costs. The stock followed the euphoria.

But those years also exposed the tension inside Horton’s model. Decentralization was a competitive advantage because local teams could move quickly and stay close to their markets. In a boom, though, that same autonomy can create heat: divisions chasing land at the same time, competition for the best parcels, and a natural urge to press harder because every quarter seems to reward growth. Horton generally held tighter controls than many peers, but nobody was fully immune to the psychology of a market that only appeared to go one direction.

It’s easy, with hindsight, to say everyone should have been more cautious. In the moment, the incentives were brutal. If you didn’t grow, you lost market share. If you didn’t grow, Wall Street punished you. And if you didn’t grow, you risked becoming the one that got acquired. The entire industry was being pushed to run faster, and D.R. Horton—disciplined as it was—still operated inside that environment.

Still, even in the middle of the frenzy, the company made a few choices that mattered when the music stopped. It stayed focused on entry-level and move-up buyers instead of shifting heavily toward the most speculative, highest-end product. It avoided some of the most extreme land bets—far-flung exurban positions that required years of investment before producing a single closing. And, relative to many competitors, it kept a more conservative posture on the balance sheet.

Geographic diversification helped too. By this point Horton wasn’t a Texas story anymore. It was operating across Texas, Arizona, California, Florida, the Carolinas, Nevada, and many other markets. When one region cooled, another could keep producing. That hedge didn’t save builders who were concentrated in the hottest bubble markets. It did give Horton more ways to maneuver.

And then there was something less visible but arguably more important: memory. D.R. Horton had been forged in earlier boom-and-bust cycles, especially the brutal swings Texas experienced in the 1980s. Donald Horton and his team didn’t have to imagine what a housing downturn felt like. They’d lived it. That history showed up in the company’s habits—how it thought about land, how it managed inventory, how quickly it tried to turn capital back into cash.

By 2006, D.R. Horton was closing more than 53,000 homes a year and had become the template for a national homebuilding platform. Competitors tried to copy the scale. The industry continued consolidating. But the foundation underneath the boom was starting to crack. Credit markets were getting fragile. Prices in many places had drifted far from what underlying incomes could support. It was becoming less a question of whether housing would correct and more a question of when—and how hard.

The warning signs weren’t subtle. Loans were being made to borrowers who couldn’t realistically repay them. Those mortgages were being packaged and sold around the world. In markets like Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Miami, prices had surged in just a few years, and speculative flipping started to look less like an edge case and more like a national hobby. “Housing bubble” wasn’t a fringe phrase anymore—it was moving into the mainstream.

D.R. Horton kept building through 2006, and it wasn’t immune to the optimism of the era. But its earlier discipline gave it at least some insulation. It hadn’t built its business around subprime lending through a captive mortgage operation the way some others did. It hadn’t loaded up on the most speculative land positions. And by homebuilder standards, it remained relatively conservative financially.

For anyone watching from the outside, 2002 to 2008 is the perfect setup for what comes next. Horton’s rise to number one was real—driven by strategy, operating execution, and a repeatable acquisition engine. But it also happened during one of the most distorted markets in modern American history. Separating true advantage from a roaring tide is almost impossible in real time.

The test was about to arrive.

V. The Financial Crisis & Recovery (2008–2014)

Then the test arrived, and it hit like a demolition ball.

D.R. Horton closed 53,410 homes in fiscal 2006. By 2010—the industry’s bottom—that number had fallen to 18,983. Revenue slid from a peak above $15 billion to roughly $4 billion. Cancellations surged. Prices dropped hard. Land that had looked like a growth engine suddenly behaved like an anchor. This was the deepest, longest housing downturn since the Great Depression, and it broke a lot of builders.

Across the industry, the casualties came in every size. Smaller regional companies disappeared entirely. Public builders that had looked like sure things in 2005 found themselves fighting for survival. Leverage that seemed manageable when home values were rising turned toxic when asset prices collapsed. And the most aggressive land bets—especially in places like Las Vegas, Phoenix, and South Florida—were the ones that blew up first and worst.

D.R. Horton didn’t escape unscathed. But it did survive. And by the time the smoke cleared, it was in a stronger competitive position than many peers who had once looked just as formidable.

Start with the balance sheet. Horton went into the crash with less leverage than a lot of the industry. It had cash. It had avoided the most speculative land exposure. That meant that when impairments came—and they did—it had the flexibility to absorb the pain, work through bad projects, and keep operating without living on the edge of a liquidity crisis or stumbling into covenant problems.

Next was the operating model. A decentralized structure isn’t just a cultural preference; in a crash, it’s a control system. Local teams could react immediately—slow starts, cut inventory, renegotiate with subcontractors, adjust pricing—without waiting for a centralized command to catch up to reality. And the company’s long-standing obsession with inventory discipline, that “build fast, sell fast” mentality Horton had baked in from the beginning, meant it didn’t enter the downturn with the same level of finished homes sitting unsold.

The most important move, though, was more subtle: even while the industry was still in triage, D.R. Horton was already looking for the shape of the recovery.

Leadership concluded that whenever demand returned, it wouldn’t start at the top of the market. It would start with the true entry-level buyer—young families and first-time homeowners who’d been priced out during the boom and then battered by the recession. That insight became the seed of Express Homes, which would later prove to be one of the most consequential strategic shifts in the company’s history. But during the crisis itself, the work was less about bold announcements and more about execution: protecting liquidity, keeping key talent, maintaining relationships with subcontractors and land sellers, and staying ready for the turn.

And the turn, when it came, was slow.

Housing starts didn’t snap back to pre-crisis levels for years. Lending standards tightened dramatically. The easy-credit era was over. Many would-be first-time buyers had damaged credit from foreclosures and short sales. Affordability became a real constraint, not a talking point. The post-crisis market wasn’t going to reward the same playbook that had dominated the boom.

D.R. Horton recognized that early and adjusted accordingly. Instead of waiting for the market to become 2005 again, the company started reshaping its product and processes for the market that actually existed. That willingness to meet buyers where they were—rather than where you wish they’d be—became the bridge from survival to the next growth chapter.

The contrast with less adaptable competitors was stark. Some builders kept pushing larger, higher-finish homes at price points the market couldn’t support. Others pulled back so far—exiting markets, dismantling teams—that even when demand returned, they couldn’t ramp without rebuilding from scratch. D.R. Horton took a different path: preserve the organization, but rethink what that organization should be building. It’s one thing to cut costs. It’s another to change the product strategy without breaking the operating machine.

By 2012 and 2013, as housing began to stabilize, Horton was already testing the ideas that would become Express Homes. The crisis years weren’t just a period to endure; they were a period to learn. The company watched which buyer segments came back first, where velocity returned, and what price points moved. It experimented with simpler offerings and more streamlined sales. While much of the industry was still recovering from the last cycle, Horton was quietly laying track for the next one.

If you want the lessons of 2008 through 2014, they’re not complicated—but they’re hard to live by in a boom.

Balance sheet strength matters in cyclical businesses. Excess leverage doesn’t just reduce flexibility; it removes your ability to choose. Culture matters too. Inventory discipline and cash-flow focus can’t be improvised when the crisis hits; they have to already be in the organization’s DNA. And finally, great companies don’t just survive downturns—they use them. D.R. Horton came out of the crash with a bigger share of a smaller market, with many weaker competitors gone and many surviving competitors diminished.

When housing finally did recover, Horton wasn’t simply still standing.

It was ready to accelerate.

VI. The Express Homes Revolution & Market Segmentation (2014–2020)

By the time the recovery finally had its footing, D.R. Horton wasn’t looking to rebuild the old playbook. It was looking to rewrite it.

In early 2014, the company launched Express Homes, a brand that quietly did something the post-crisis industry had been avoiding: it went straight back to the true entry-level buyer. The premise was almost aggressively simple. Homes priced around $120,000 to $150,000. Turnkey. And, most importantly, no options—no upgrades, no finish selections, no drawn-out design meetings. Just a well-built house you could buy, close, and move into.

That simplicity was the point. In production homebuilding, options are a profit center—but they’re also a complexity machine. Every buyer choice adds friction: new materials to order, different subcontractors to schedule, new points of failure that stretch timelines and inflate costs. Express stripped that all out. Efficient floor plans. Standardized materials. Faster builds. Lower prices. Sell to the customers everyone else had effectively left behind.

The strategic logic started with a very specific bet about who would lead the next phase of housing demand. Then-CEO Donald Tomnitz said it plainly: “The next leg of the recovery will be led by the true entry-level buyer.” At the time, that wasn’t the consensus. Plenty of people assumed first-time buyers were sidelined for years—tight lending, scarred confidence, weak savings. The expectation was that the recovery would come from move-up buyers with pristine credit and bigger down payments.

Horton’s team saw the pressure building in the opposite direction. They watched the demographics: a massive millennial cohort moving into household-formation years. They watched the affordability math: wages weren’t rising fast enough to support the kind of upgraded, option-heavy homes the industry loved to sell. And they concluded that the first-time buyer wasn’t gone. The market just wasn’t offering them a product that fit.

So Express Homes offered that product. Typically smaller, efficient homes—often around 1,000 to 1,500 square feet—built with durable, standardized finishes instead of premium upgrades. The company compressed construction cycles by standardizing processes and eliminating customization. And by removing buyer selections entirely, it cut a whole category of delays that regularly slow production builders down.

The early results came in stronger than Horton expected. Express drove a meaningful portion of a big jump in sales orders, and it quickly became a material share of total homes sold—evidence that the demand wasn’t theoretical. It was sitting there, waiting for a builder to take it seriously.

What made Express powerful wasn’t just the pricing. It was the operating leverage. With standard plans and standard materials, procurement could buy at scale and negotiate better pricing. Crews could move faster because every home looked familiar. Sales moved quicker because there was nothing to customize and nothing to upsell. And the whole system—design, purchasing, construction, and closing—ran with less variance. In homebuilding, variance is where cost hides.

Express also clarified something bigger: D.R. Horton wasn’t going to be a single-brand company trying to stretch one product identity across every buyer type. It was building a portfolio.

By this point, Horton operated four distinct brands aimed at four different segments. The D.R. Horton name stayed focused on move-up buyers. Emerald Homes served the luxury end. Express Homes captured entry-level demand. Freedom Homes targeted active adults and empty nesters. Instead of forcing one label to mean everything, the company could compete across the spectrum with offerings designed for each customer.

That architecture mattered for more than marketing. It acted like a built-in hedge. When one segment cooled, another could hold up better. When affordability tightened, entry-level product often mattered more. When higher-end buyers pulled back in uncertainty, buyers frequently traded down. Horton didn’t have to guess which segment would lead—it could watch the data across all of them and shift emphasis.

By 2020, Express Homes—and homes priced at or below $350,000—made up more than half of D.R. Horton’s delivered homes. The company had repositioned itself as a scale leader in affordability, not just a scale leader in volume. And that distinction would become increasingly valuable as affordability pressure returned to the center of the housing conversation.

For investors, Express is a good lens on how Horton thinks. This wasn’t a minor tweak or a new floor plan series. It was a deliberate trade: accept that you might cannibalize some higher-margin sales in order to win share, build a durable cost advantage, and own the segment that ultimately sets the tempo for the entire market.

And in hindsight, that bet looks less like a gamble and more like timing. Horton built the Express machine—the standardized designs, the streamlined sales process, the cost structure—before most competitors fully recognized how large the entry-level gap had become. In homebuilding, that kind of head start compounds. It’s hard to copy quickly, because it’s not a marketing decision. It’s an operating system.

VII. Recent Acquisitions & Scale Economics (2015–2024)

The acquisition machine Donald Horton built in the 1990s never really shut off. Even as D.R. Horton pushed organic growth and scaled brands like Express, it kept doing what it does best: picking up strong local operators, in the right markets, at sensible prices—and then letting them run.

In April 2015, D.R. Horton bought Pacific Ridge Homes, a Seattle-based builder, for $72 million. The deal came with a ready-made footprint: hundreds of lots, homes already in inventory, and a backlog of sold homes waiting to be built—plus control of additional lots through option contracts. Seattle was one of the country’s most competitive housing markets, fueled by tech-driven job growth and constrained supply. For Horton, the point wasn’t just “enter Seattle.” It was to enter with instant scale—something that would have taken years to build from scratch.

In 2016, the company followed with the acquisition of Wilson Parker Homes for $90 million, strengthening its presence in Georgia and the Carolinas. The integration looked familiar: keep the local leadership close to the market, plug them into Horton’s capital and back-office platform, and avoid smothering the entrepreneurial operating rhythm that made the business worth buying in the first place.

Then 2018 brought a burst of deals. Terramor Homes, based in Raleigh-Durham, joined for $62 million in cash—one of three private homebuilder acquisitions Horton announced within a single month. Classic Builders and Westport Homes added more scale in other markets. None of these were headline-grabbing on their own, but that’s the point. Horton doesn’t need one giant swing. It stacks small, disciplined moves that steadily widen its footprint in high-growth regions.

The most strategically important transaction of the era, though, wasn’t another homebuilder. It was land.

In 2017, D.R. Horton announced it would acquire 75 percent of Forestar Group for $17.75 per share. Forestar is a lot developer: it buys and entitles land, turns it into finished residential lots, and sells those lots to builders. With Forestar as a majority-owned subsidiary, Horton gained a built-in pipeline of developed lots—while Forestar still sold to third-party builders, too.

That relationship created a different kind of advantage. In homebuilding, land is the constraint that quietly controls everything: cost, pace, and how fast you can grow when demand shows up. But land development is also capital-intensive, slow, and full of entitlement risk—local approvals can delay a project or kill it entirely. By pairing the homebuilding machine with a controlled lot-development engine, Horton gave itself more control over supply and better flexibility on how and when it deploys capital into land.

The logic is subtle, but powerful. Homebuilding is a conversion business: turn land into homes, then turn homes into cash. The earliest part of that cycle—entitlement and lot development—soaks up time and capital long before a closing happens. With Forestar, Horton could scale that capability while also preserving flexibility: buy lots when it makes sense, without being forced to take every lot Forestar produces. Meanwhile, Forestar’s third-party lot sales help support the business on its own, and its public reporting gives investors a clearer window into the lot pipeline that can eventually feed Horton’s starts.

Builders without a structure like this face a tougher trade-off. They either carry more land and development risk directly on their own balance sheets, or they rely more heavily on buying finished lots from independent developers at market prices. Forestar gave Horton advantages in both availability and economics—an edge that’s hard to replicate without major capital commitments and years of execution.

All of this fit the broader consolidation moment. As one observer put it: "Overall, the things D.R. Horton is doing are what you would want from a homebuilder right now. It's using its size and strength to acquire smaller companies and consolidate the market, but it's also allocating lots of cash to preserve its balance sheet. Should the market hit a swoon now, a strong balance sheet could give it the flexibility to make more of these opportunistic acquisitions down the road."

That’s the through-line from the 1990s to the 2020s: grow, but don’t get reckless. Keep powder dry. Use scale to play offense when others can’t.

For investors, this period reinforces something easy to underestimate: acquisition skill is a core competency at D.R. Horton. The company doesn’t just buy businesses. It buys them without breaking what made them work—then gives them the tools to grow faster under a larger platform. Do that well, consistently, across decades, and it becomes its own kind of moat.

VIII. Financial Performance & Operating Model

By 2024, D.R. Horton’s finances looked like what you’d expect from a company that’s been tuning its machine for decades. Fiscal 2024 brought in $36.8 billion in revenue, up modestly from the year before. Net income was $4.76 billion, and earnings per diluted share came in at $14.34 for the year. Pre-tax profit margins held at 17.1%, and return on equity reached 19.9%—a standout result for a capital-intensive business that lives and dies by interest rates and consumer confidence.

But the more interesting story isn’t the scoreboard. It’s how Horton keeps putting those numbers up.

The operating model is built around a simple idea: push decisions to the edge, keep discipline at the center. Local teams run the core work—finding land, developing it, building homes, and selling them—because that’s where local knowledge matters. Corporate headquarters steps in where scale matters: capital allocation, financial oversight, and shared services. The result is a company that can move fast in individual markets without losing control of the balance sheet.

That structure matters even more because of Horton’s footprint. It operates in 125 markets across 36 states, which gives it a built-in hedge against regional slowdowns. When one market softens, another can carry the load. And when a region offers unusually attractive returns, Horton can shift capital quickly. Smaller builders don’t have that option; they’re tied to whatever their home market gives them.

That same discipline shows up in how the company thinks about cash. In fiscal 2024, D.R. Horton generated $3.4 billion of cash from operations after investing $8.5 billion in lots, land, and development. It also returned $4.8 billion to shareholders through repurchases and dividends, and raised its quarterly dividend to $0.45 per share, up 13% year over year. The headline takeaway is that Horton doesn’t just grow—it throws off cash while it does.

And it does it with a balance sheet that leaves room to breathe. Roughly $3 billion in cash. A debt-to-capital ratio below 20%. In an industry where downturns routinely turn leverage into a death sentence, Horton’s conservatism isn’t timid—it’s strategic. It means the company can keep building, keep buying, and keep playing offense while others are negotiating with their lenders.

You can see how that mindset plays out when conditions get harder.

The fiscal 2025 results and fiscal 2026 guidance showed a company operating in a higher-rate world, where affordability becomes the battleground. In the fourth quarter of fiscal 2025, net sales orders rose 5% year over year to 20,078 homes, valued at $7.3 billion. Consolidated pretax income was $1.2 billion on $9.7 billion in revenue, with a pretax profit margin of 12.4%. That margin compression—versus the prior year—was largely the cost of keeping demand moving: more incentives, especially mortgage rate buydowns.

Horton’s response to affordability pressure was straightforward and unapologetically practical. It offered mortgage rate buydowns that could take an effective rate down to about 3.99% when market rates were closer to 7%. In fiscal Q4 2025, 73% of buyers used a mortgage rate buydown. That spending hit profitability—gross margins on home sales fell to 20% from 23.6% a year earlier—but it kept sales velocity intact.

CEO Paul Romanowski summed up the logic: “The most attractive monthly payment we can put them in is with a lower rate.” That line captures what Horton understands about the buyers it’s built its system around. Especially at the entry level, buyers don’t buy a price tag. They buy a monthly payment. If incentives protect volume and keep communities absorbing, Horton can live with lower margins in the short run.

And there’s a second layer here: competitive intent. Horton is willing to give up near-term profitability to defend—and potentially expand—market position. Not out of generosity, but because market share in homebuilding has compounding effects. More volume keeps sales teams sharp, keeps subcontractors working, and keeps supply chains warm. Those relationships and that momentum are hard to rebuild once you lose them.

In practice, this also pressures the rest of the industry. Smaller builders often can’t afford to match the same incentives without breaking their economics or stressing their balance sheets. That leaves them with two unpleasant choices: hold price and lose volume, or chase volume and risk financial strain. Either way, Horton’s relative position improves. It’s the same consolidation dynamic Horton has used for decades—just executed through operating strength instead of M&A.

For investors, the scoreboard isn’t complicated, but it does require context. Watch closings volume to understand whether Horton is holding or gaining share. Watch gross margins on home sales to see pricing power and cost control. And watch absorption—sales per community per month—because it’s a clean read on community-level demand and execution.

The real insight comes from how those metrics move together. Volume gains driven purely by aggressive incentives can be fragile. Margin protection achieved by pulling back too hard can quietly hand share to competitors. Absorption helps reveal whether demand is truly there, independent of the pricing levers being pulled.

One more metric adds color: the backlog conversion ratio, or how much beginning-of-quarter backlog actually closes during the quarter. High conversion points to smooth construction and clean closings. Low conversion can signal build delays, supply chain issues, or financing friction. Historically, D.R. Horton’s conversion has tended to run better than industry averages—another reflection of a culture built around operational cadence, not just growth.

IX. The Donald Horton Legacy & Leadership Transition

On Friday, May 17, 2024, D.R. Horton announced that its founder and Chairman, Donald R. Horton, had died suddenly. He passed in the early morning hours of May 16, apparently from a heart attack. He was 74. It was the closing chapter on an era that began almost five decades earlier, when Horton borrowed $500,000 to build a single house in Fort Worth—and then just kept compounding that first bet into a company that would come to define modern American homebuilding.

Over time, Horton’s role shifted from operator to architect. He served as President and CEO from the company’s incorporation in 1991 until 1998, when he moved into the Chairman role and focused more on long-term direction than day-to-day execution. By 2020, he owned about 6% of the company—still a meaningful stake, still very much aligned with shareholders, but no longer the kind of ownership that makes a company feel like it lives and dies with one person.

That evolution mattered, because the leadership transition at D.R. Horton wasn’t abrupt. It was slow, intentional, and designed to hold up under stress. The company built real management depth—people who had spent decades inside the system, learned the culture, and been tested through multiple cycles.

Donald Tomnitz ran the company through the financial crisis years, when stability wasn’t a nice-to-have; it was survival. David Auld succeeded him and kept the strategy moving forward. Today, Paul Romanowski leads as CEO, with Jessica Hansen as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer. Beneath them is a deep bench of division presidents and operational leaders who run the business where it’s actually run: in local markets, community by community.

That depth speaks to something distinctive about Horton’s legacy. He didn’t build a company that required him to be the hero every day. He built an organization—systems, habits, incentives, and a culture that could scale beyond any one person. If the founder’s absence doesn’t change how the machine runs, that’s not luck. That’s design.

You can still see his fingerprints in the way the company behaves. The fixation on inventory turnover and cash flow. The refusal to overcomplicate the product when simplicity sells. The decentralized structure that trusts local teams to make market calls, paired with financial accountability from the center. The acquisition approach that keeps entrepreneurial talent in place instead of burying it under corporate process. These aren’t slogans. They’re defaults.

For investors, founder deaths often create a moment of real uncertainty. If a company’s edge is mostly personal—relationships, instincts, force of will—then losing the founder can expose how fragile the advantage really was. D.R. Horton’s steadiness after Horton’s passing suggests the opposite: the competitive advantage is institutional. The playbook holds because it works, not because one person is there to enforce it.

Horton’s own journey offers the cleanest proof of what he built. By the time he died, his roughly 6% stake was worth several billion dollars—wealth created the old-fashioned way, not through financial engineering or a single lucky break, but by turning a hard, cyclical business into a repeatable operating system. He built homes for American families at scale, at prices they could afford, more efficiently than anyone else. That’s the legacy: not just a company with his name on it, but a machine that keeps building.

X. Current Strategy & Market Position

By early 2026, the housing market had settled into a tough, uneven equilibrium. Mortgage rates stayed well above the pandemic-era lows that supercharged 2020 and 2021. Affordability got tighter, not just because rates were higher, but because prices didn’t fall enough to offset them. And resale inventory remained unusually scarce, because millions of homeowners were sitting on sub-4-percent mortgages and had no interest in swapping them for a much more expensive loan.

That “lock-in effect” changed the flow of demand. Total transactions stayed muted, but the demand that did exist shifted toward new construction. If you wanted to move, a new home was often one of the few viable options. That dynamic has been a quiet tailwind for large builders like D.R. Horton, even in a market that otherwise feels constrained.

Horton’s response has been exactly what you’d expect from a company built around pragmatism and volume. It leaned hard into incentives—especially mortgage rate buydowns. Management disclosed that about 73 percent of fiscal Q4 2025 buyers used buydowns that brought effective mortgage rates to around 3.99 percent. It’s not free. Those incentives squeeze margins in the near term. But Horton is making a deliberate trade: protect sales velocity, defend share, and keep the machine running.

At the same time, the company kept refining the product itself to meet buyers where they are. Express Homes, in particular, has continued to evolve around efficiency and affordability. Floor plans were redesigned to use space better, with many models now averaging roughly 1,400 to 1,600 square feet—enough home to feel livable, without paying for wasted corners. That design discipline helps Horton hit price points many competitors struggle to reach, and it’s one reason homes priced at or below $350,000 still make up more than half of deliveries.

Another lever Horton has been pulling is build-for-rent. The company began its multifamily rental operations in 2016 and by this point had projects in 20 markets across 11 states. The model is straightforward: build single-family detached rentals, townhomes, and apartment communities, then typically sell the finished properties to institutional investors. It’s a way to keep crews busy and monetize construction capacity even when the retail buyer gets squeezed.

Recent transactions show how it works in practice. Horton sold a community of 100 detached single-family build-to-rent homes in Leesburg, Florida, for $27.2 million. It also sold a 147-unit rental home community in Houston for $36 million, or about $245,000 per unit. In these deals, Horton captures development fees and construction profits, then hands off the long-term ownership and operating risk to investors built for that job.

Forestar remains another structural advantage in this environment. As a majority-owned lot development subsidiary, it gives Horton more control over its lot pipeline. The company can scale Forestar’s development activity alongside its own building volume, supporting lot availability without forcing Horton to carry as much land directly. More importantly, it adds flexibility. When the market is strong, Horton can push. When conditions soften, it can pull back. Builders without that kind of optionality often end up stuck—either overinvested in land at the wrong time or scrambling for supply when demand returns.

All of this is anchored by a balance sheet built for cyclicality. With around $3 billion in cash and a debt-to-capital ratio below 20 percent, Horton has room to maneuver. If conditions deteriorate, it can absorb a long stretch of weakness without turning into a distressed seller. And if opportunities open up—distressed acquisitions, attractive land, or simply the chance to take share from weakened competitors—it has the capital to act.

Management’s fiscal 2026 outlook reflected that same posture: steady, controlled, and designed to avoid the classic homebuilding sin of building too far ahead of demand. Community count was expected to rise 13 percent year over year, creating a broader platform for sales, but the approach to starts stayed measured—aggressive enough to stay relevant in every market it cares about, conservative enough to avoid getting caught with excess inventory if buyers pull back again.

The bigger takeaway is that Horton is widening the number of ways it can win. Incentives keep buyers moving. Smaller, smarter plans keep the product within reach. Build-for-rent adds a second customer base when retail affordability tightens. Forestar supports lot supply and capital flexibility. And the balance sheet keeps all of it from turning into a gamble.

For investors, the question is the same one Horton has been answering for decades: does accepting margin pressure today buy a stronger position tomorrow? The company’s history suggests that, more often than not, it does.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Three decades of D.R. Horton’s history offer lessons that go well beyond homebuilding—really, they apply to any capital-intensive, cyclical business where the penalty for getting timing wrong can be existential.

Scale matters, but only when it turns into structural advantage. Horton’s size buys it things smaller builders can’t easily touch: better terms from national suppliers, cheaper and more reliable access to capital, geographic diversification that softens regional downturns, and a brand that reduces friction in selling. But scale isn’t automatic strength. It only works because Horton built an operating system—especially the decentralized model and the acquisition playbook—that lets the company get bigger without getting slow.

Operational excellence compounds. The inventory discipline and cash-flow focus Don Horton baked in from the beginning weren’t one-time insights; they became habits, and then they became culture. Every cycle added more reps: where mistakes happen, what breaks first, what to tighten when demand cools, and what to press when others retreat. Over time, that operational learning turns into a kind of institutional asset—one that’s hard to copy even if you have the money.

Acquisition integration is a learnable skill, and Horton learned it the hard way—by doing it over and over. A lot of companies buy growth and then suffocate it with process. Horton’s philosophy is more surgical: preserve the entrepreneurial energy and local market instincts, and centralize the parts that are pure overhead or friction. That approach requires patience, a consistent operating doctrine, and the humility to trust the people who actually know the market.

Product segmentation expands the playing field. By running four brands across price points and buyer types, Horton isn’t forced to bet the company on a single demographic or a single “right” product cycle. When affordability tightens, the entry-level offering matters more. When move-up demand returns, the core brand benefits. When one segment stalls, another can carry. The portfolio isn’t just marketing—it’s risk management and growth optionality.

Capital cycle awareness is non-negotiable in a cyclical industry. Horton’s long-running conservatism in good times—protecting the balance sheet, avoiding overreach—creates the ability to act in bad times. It’s counterintuitive, because booms tempt you to believe the party is permanent. Horton’s history shows the opposite mindset wins: keep flexibility when things are easy so you can be aggressive when things are hard.

Meeting customers where they are beats hoping they’ll become someone else. Express Homes worked because it accepted a basic truth: entry-level buyers buy a monthly payment, not a Pinterest board. Horton built for the market that existed—simpler, more standardized, more affordable—rather than waiting for buyers to magically regain the purchasing power and confidence of a different era.

Long-term thinking creates room for short-term flexibility. Horton’s willingness to accept margin compression from incentives in 2024–2025 wasn’t a sign of weakness; it was a sign of position. If you believe your competitive advantage is durable, you can trade some near-term profitability to protect volume, defend share, and keep the machine running. That’s a multi-decade mindset, not a quarter-to-quarter one.

Vertical integration can create strategic optionality. The Forestar relationship is a good example of how corporate structure becomes strategy. With a majority-owned lot development engine, Horton gets better visibility into its land pipeline, more security of supply, and more flexibility in how it deploys capital into land. Competitors can try to replicate that, but it takes time, expertise, and significant capital—meaning the advantage tends to persist.

Culture travels—or it doesn’t. Horton’s ability to execute consistently across 125 markets and through multiple cycles says something deeper than process. It suggests a culture that has been deliberately built, reinforced, and handed down: local autonomy with accountability, speed without chaos, discipline without paralysis. In a business where small mistakes get amplified by leverage and cycles, that cultural durability may be the most valuable advantage Horton has—and the hardest for anyone else to steal.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case

Bear Case

Interest rate sensitivity remains the most obvious risk. D.R. Horton’s business ultimately runs on affordable monthly payments, and that means it runs on mortgage rates. If rates stay elevated—or move higher—for longer, demand could weaken more than the market currently expects. The company’s heavy use of mortgage rate buydowns is revealing here: it’s proof that affordability is stretched. If Horton has to keep spending at that level to keep orders flowing, margins get squeezed and earnings power comes down.

Land cost inflation is another structural pressure. Buildable lots in the right places are scarce, and scarcity has a price. Forestar helps, but it doesn’t repeal the fundamentals: land is one of the biggest inputs in homebuilding, and in many markets it has inflated faster than what buyers can comfortably pay for the finished home. If land keeps getting more expensive while affordability caps how much Horton can raise prices, the math points to more margin compression.

Labor shortages are a third constraint, and they’re not new—but they haven’t gone away. Skilled construction workers are aging out, and the pipeline of younger workers hasn’t fully replaced them. Horton can blunt the impact with more standardized builds and prefabricated components, but it can’t eliminate it. Tight labor markets push wages up, slow construction schedules, and increase the risk of quality issues when crews are stretched.

Then there’s the risk you can’t diversify away: cyclicality. Homebuilding is one of the most cyclical businesses in the economy. Even the best operators see sharp drops in revenue and profits when demand breaks. D.R. Horton proved it could survive 2008 to 2010, but that doesn’t guarantee the next downturn will look the same—or that the playbook will translate perfectly if the shock comes from a different direction.

Margin compression could persist even without a classic recession. Between higher land costs, elevated incentives, and an affordability-constrained buyer, the industry’s economic engine has already shifted. Horton’s gross margins have moved down from the mid-20s to around 20 percent. If those pressures become the new normal, earnings can decline even if volumes don’t collapse.

Regional concentration adds another layer of exposure. Horton is national, but it still leans heavily on big Sunbelt markets like Texas, Florida, and Arizona. If those regions hit a tougher patch—whether from local economics, rising insurance costs, water constraints, or other long-term frictions—Horton would feel it disproportionately. The same migration patterns that helped demand could also slow or reverse.

Regulatory and political risk is always in the background in housing, because so much of the industry is governed locally. Zoning, building codes, impact fees, and permitting timelines can swing project economics. Immigration policy influences the construction labor pool. Federal Reserve policy shapes mortgage affordability. Environmental regulation can change what’s buildable, how fast it can be entitled, and at what cost. These forces can create opportunity, but they can also quietly erode returns.

Finally, Horton’s competitive environment has changed because it won. Consolidation means the company increasingly competes against other well-capitalized national builders—Lennar, PulteGroup, and others—that can match incentives, pursue the same land, and scale similar operating improvements. Competitive escalation matters in homebuilding because price wars and incentive battles don’t just shift share; they can reset profitability for everyone.

Put differently, the bargaining dynamics have become less friendly. Buyers are more price-sensitive, which forces concessions. Suppliers of scarce inputs—labor and prime land—have leverage. And while the barriers to entry remain high, the relevant competition is no longer a fragmented field of local builders. It’s a smaller set of powerful peers with the balance sheets to fight.

Bull Case

D.R. Horton has been the largest homebuilder by volume in the United States for more than two decades. That kind of sustained leadership in a cyclical industry isn’t an accident, and it isn’t just a function of catching a lucky wave. Horton has held the crown through wildly different environments—the subprime boom, the financial crisis, the slow recovery, COVID-era disruption, and now a high-rate market. The consistency suggests there’s something real underneath: a repeatable operating system.

The structural housing shortage is also real, and it’s not something the country fixes in a year or two. The U.S. underbuilt for much of the post-2008 era, and construction hasn’t fully closed the gap versus household formation. That deficit doesn’t guarantee smooth quarters, but it does create a backlog of demand that tends to reassert itself when affordability loosens even a little.

Demographics support that story. Millennials are in peak household-formation and homebuying years. Even if the first purchase gets delayed, the underlying demand doesn’t disappear—it stacks up. Horton’s emphasis on entry-level and affordable product puts it in a strong position to capture that release of demand when financing conditions improve.

Operational excellence and scale are where Horton’s advantage compounds. Bigger isn’t automatically better in homebuilding, but Horton has translated size into a real cost and execution edge: more purchasing power, more consistent processes, and an operating model that lets local teams adapt quickly while the corporate center enforces financial discipline. That efficiency can show up as better margins, or it can be reinvested into price and incentives to win share. Either way, the system improves with volume.

Balance sheet strength adds another kind of edge: optionality. With about $3 billion in cash and low leverage, Horton can withstand weak demand for longer without becoming a forced seller. And when the industry gets stressed—when smaller builders run into financing problems, or landowners get more flexible—Horton can play offense. In a cyclical industry, the ability to act when others can’t is often where long-term returns are made.

Consolidation continues to work in Horton’s favor. Smaller builders tend to struggle the most when affordability is tight and financing is expensive, because they can’t match incentives or carry inventory risk the same way. Each cycle tends to concentrate share with the strongest operators, and Horton has consistently been a primary beneficiary.

You can also describe the bull case in the language of durable advantage. Horton benefits from scale economies: national procurement, shared services, and spreading fixed costs over a massive base. It has process power: deeply embedded disciplines around inventory turns, cash flow management, and construction cadence that aren’t easy to copy quickly. Express Homes is a form of counter-positioning: it captured entry-level buyers with a stripped-down, efficient model that others were slower to embrace because it conflicted with higher-margin, higher-complexity approaches. And there are relationship dynamics—especially with subcontractors—where reliable volume makes Horton a preferred partner, and that preference becomes a subtle but meaningful advantage over time.

There’s also a capital-cycle advantage built into the business. Homebuilding requires large upfront investment—land, development, construction—long before the cash comes back at closing. Horton’s access to capital markets, combined with the Forestar structure, helps it fund that cycle more efficiently than smaller competitors who depend on local banks and tighter credit. In a capital-intensive industry, cost and availability of capital become competitive weapons.

Finally, industry structure is quietly improving for large players. The top builders now control roughly 30 percent of new home production, and that share has been rising. As the largest builder, Horton tends to benefit disproportionately. When smaller regional builders stumble or exit, their lots, subcontractor capacity, and customer demand don’t vanish—they get absorbed. Horton has proven, repeatedly, that it can take those opportunities and scale them without breaking its operating model.

XIII. Final Analysis

D.R. Horton isn’t a glamorous company. It doesn’t show up in conversations about artificial intelligence or the next wave of technological disruption. It doesn’t inspire cult-like founder mythology. It builds houses—and for more than twenty years, it has built more houses than anyone else in America. Boring, maybe. But in housing, boring is often another word for durable.

That’s the real punchline of this story. The great businesses aren’t always the ones that make the most noise. They’re the ones that execute relentlessly, stack small advantages until they become structural, and come out of each cycle with more share and more capability than they had going in. D.R. Horton fits that pattern as cleanly as almost any company in the public markets.

Looking forward, the opportunity set is familiar—but still meaningful. There’s room for continued geographic expansion in the markets where population and jobs keep moving. There’s upside in construction process innovation, especially anything that helps with labor constraints and cycle-time compression. There’s the steady drumbeat of market share gains, whether through acquisition or simply outlasting and out-executing smaller competitors when conditions get tight. Build-for-rent adds a second demand channel that can complement the traditional for-sale business. And Forestar remains a structural edge: more control and visibility into lot supply, and more flexibility in how capital gets deployed into land.

If we were advising D.R. Horton’s management, the priorities would be less about reinvention and more about protecting what already works while pushing the system forward. Keep investing in construction process innovation that reduces labor dependency and variability. Expand build-for-rent with discipline—treat it as a strategy, not a land-grab. And keep the balance sheet strong enough to play offense when the next downturn creates forced sellers and cheap land. Above all, resist the classic temptation in this industry: chasing growth so aggressively in good times that you give back the company in bad times.

Donald Horton built something that outlasted him. He started with $3,000, a borrowed half-million dollars, and the conviction that he could sell what he built. What he left behind wasn’t just a big company with his name on it. It was an institution: a set of cultures, systems, and competitive advantages that don’t require the founder in the room to keep working.

The American housing market will keep cycling. Rates will rise and fall. Land and labor will get cheaper and then more expensive. Confidence will come and go. But the underlying need doesn’t change: people need places to live. Through all of it, D.R. Horton will be there, turning land into neighborhoods.

Maybe that’s what Horton understood earliest—probably before the IPO, before the acquisitions, and long before Wall Street cared about quarterly absorption rates. Housing is fundamental. It doesn’t go away in recessions. It doesn’t become obsolete. Demand shifts and pauses, but it doesn’t disappear. A builder that can produce homes efficiently, keep them within reach of real buyers, and stay financially conservative enough to survive the bad years will keep finding opportunity.

The philosophy is deceptively simple: build fast, sell fast, collect cash, repeat. The hard part is doing it consistently across 125 markets, through multiple cycles, with the discipline to avoid boom-time overreach and the flexibility to adapt when the market changes underneath you. D.R. Horton has done that for nearly five decades. The founder is gone. The machine is still running.

XIV. Recent News

In early 2026, the housing market still felt tight—but for D.R. Horton, it was the kind of “hard, but workable” environment the company has been built to operate in.

In late October 2025, Horton reported fiscal Q4 2025 results that underscored that point: sales pace held up even with mortgage rates still elevated. Net sales orders rose 5% year over year to 20,078 homes. Management also raised the quarterly dividend 13% to $0.45 per share, a signal that—despite the noise in the market—the company believed its cash generation remained durable.

The centerpiece of Horton’s playbook in this cycle has been incentives, especially mortgage rate buydowns. About 73% of recent buyers used buydowns that brought the effective rate down to roughly 3.99% even as market rates hovered near 7%. The trade-off is exactly what you’d expect: demand stays moving, but profitability takes a hit. Gross margins on home sales fell to 20% from 23.6% a year earlier as the company effectively “spent” margin to protect volume.

Horton has also been expanding its footprint. Management guided to about 13% year-over-year growth in community count for fiscal 2026, setting up a larger platform to capture demand as it appears. At the same time, the company emphasized a measured approach to construction starts—keeping enough inventory to sell, without getting caught with too many finished homes if buyers hesitate.

Build-for-rent remained active as another outlet for the machine. Horton continued developing projects across multiple markets and has been selling completed communities to institutional investors, including recent sales in Florida and Texas. The structure is consistent: Horton earns development fees and construction profits, then transfers long-term ownership risk to buyers designed to hold and operate rental assets.

Wall Street has framed fiscal 2026 as another test of Horton’s adaptability: mortgage rates that won’t come down easily, more cautious consumers, and affordability constraints that don’t go away just because builders want them to. Management has been clear it’s willing to keep spending on incentives to defend volume and market position, even if that means living with margin pressure. The planned community-count growth reinforces that they believe demand will show up as new communities open and marketing ramps.

Competition is tightening at the top end of the industry, too. Lennar, the second-largest homebuilder in the U.S., has also leaned into aggressive incentives, setting up a market where the biggest, best-capitalized players fight hardest for available demand—while smaller builders struggle to match the offers. That dynamic tends to accelerate consolidation and, over time, strengthen the position of the leaders.

Horton’s stock reflected that push-and-pull. Shares have remained volatile as investors weigh near-term margin compression against the company’s long-term structural advantages. Even the valuation has looked like a market in waiting—neither cheap enough to scream “deep value,” nor expensive enough to signal broad confidence. For investors, that kind of ambiguity is often where the real decision gets made: whether you believe Horton’s operating system will turn today’s pressure into tomorrow’s share gains.

XV. Links & Resources

Company Filings - D.R. Horton annual reports and 10-K filings on SEC EDGAR - Quarterly earnings releases and investor presentations on D.R. Horton Investor Relations

Industry Research - National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) Housing Market Index - U.S. Census Bureau data on new residential construction - Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) on housing starts and permits - Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies research reports - Urban Land Institute housing market analyses

Key Metrics to Track If you’re following D.R. Horton as a business—or as an investment—the story usually shows up in three metrics: 1. Net sales orders (units and value) — the cleanest read on demand momentum 2. Gross margin on home sales — a window into pricing power, incentives, and cost control 3. Absorption rate (sales per community per month) — how efficiently each community converts traffic into contracts

The most useful way to read these is in combination: quarter over quarter and year over year, and side-by-side against peers like Lennar and PulteGroup. That’s where you see whether Horton is simply riding the market, or quietly taking share.

Long-Form Articles Referenced - “The Great Recession: Builders Look Back” — Builder Magazine - “History of D.R. Horton, Inc.” — Funding Universe - “D.R. Horton, Inc.” — Encyclopedia.com company profiles - “Why D.R. Horton’s Express Homes are a Success” — Builder Online - “What D.R. Horton’s dominance means for every U.S. homebuilder” — HousingWire

Industry Context - Housing Industry Association economic analysis and forecasts - Moody’s and S&P homebuilding sector research - Academic research on housing economics and construction cycles - Federal Reserve speeches and research on housing market dynamics - Congressional Budget Office analysis of housing policy impacts

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music