Ecolab: The Clean Water, Clean Business Story

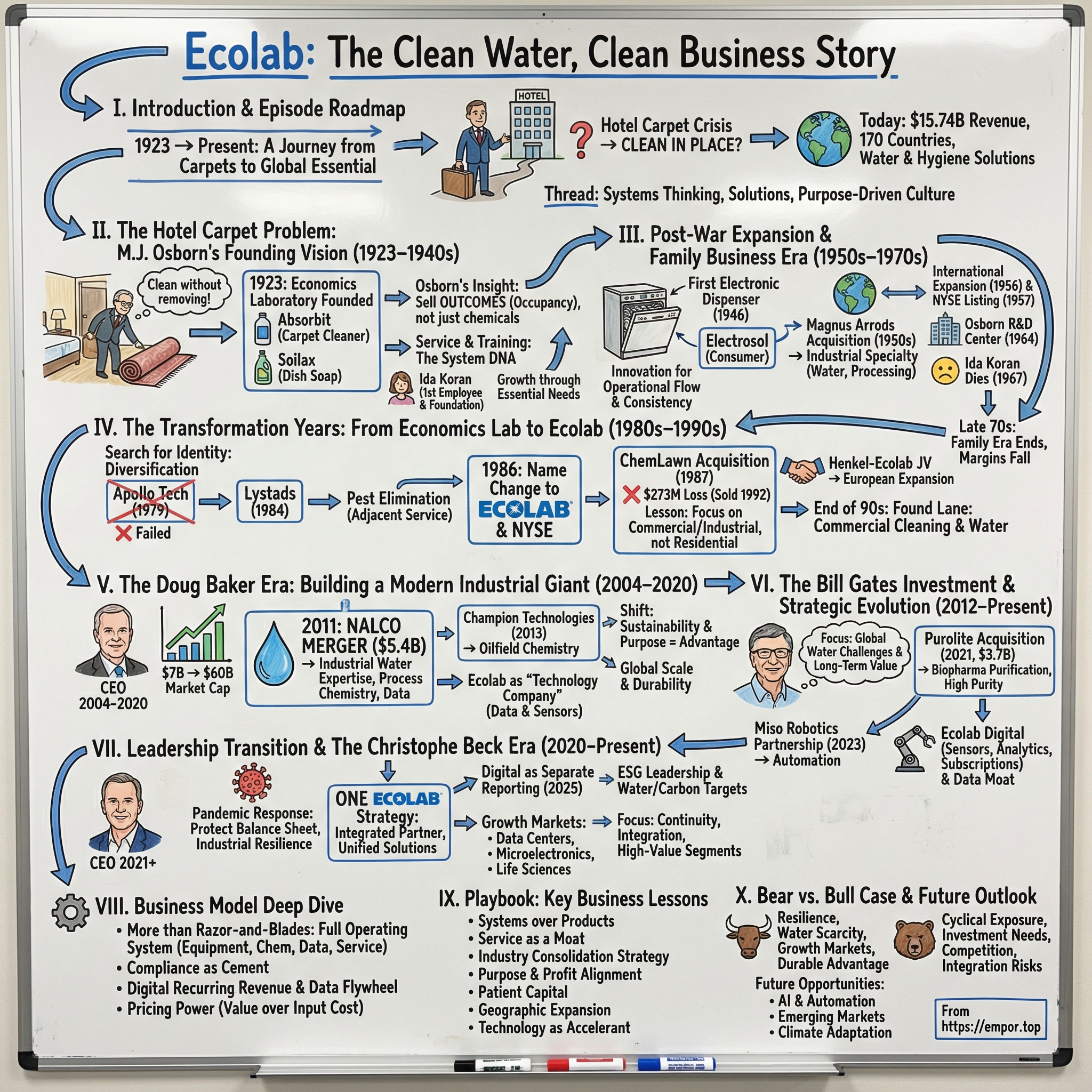

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: Minnesota, 1923. A 44-year-old traveling salesman is running out of runway. Two sons are nearing college age, and he needs a business idea that actually works. On the road, he keeps seeing the same small crisis play out in hotel after hotel: carpets get hauled out for cleaning, sometimes for a week. Rooms sit empty. Revenue disappears. Managers fume. Guests complain.

Then the obvious question hits him: what if you could clean the carpet without removing it, and have the room ready again by tonight?

That one question kicked off what would become one of the most essential business-to-business companies in the world. Today, Ecolab Inc., headquartered in Saint Paul, Minnesota, helps customers treat, purify, clean, and manage water in an enormous range of settings. In 2024, it generated $15.74 billion in revenue and $2.11 billion in earnings—putting it firmly in the top tier of industrial services companies.

What’s remarkable is what this story isn’t. Ecolab didn’t win by dropping a single breakthrough invention or “disrupting” an industry overnight. It won the hard way: by building a company that becomes part of the customer’s operation. Customers don’t just buy chemicals or equipment. They buy outcomes—clean water, safe food, fewer shutdowns, smoother audits, protected brands.

That’s the thread we’ll follow: systems thinking over product thinking; the shift from selling stuff to delivering solutions; and how a purpose-driven culture—where operational performance and environmental stewardship can reinforce each other—turned a scrappy Midwestern business into a global essential.

From one salesman’s carpet problem to a company operating in roughly 170 countries—and, at one point, a major holding for Bill Gates—this is how Ecolab became the quiet infrastructure behind clean water and clean business.

II. The Hotel Carpet Problem: M.J. Osborn's Founding Vision (1923–1940s)

Merritt J. Osborn wasn’t a young man with time to experiment. He was 44, a traveling salesman, and he could see two college tuitions coming fast. Most people in his position would’ve played it safe. Osborn did something more useful: he paid attention.

His job kept him on the road across the upper Midwest, night after night in hotels. And once you’ve slept in enough of them, you start to notice the machinery behind the scenes: housekeeping racing the clock, managers protecting occupancy like it’s oxygen, front desks dealing with the mess that comes from a building full of strangers. Osborn kept seeing one operational headache in particular: carpets.

When hotel carpets got too dirty for a quick vacuum, they didn’t get cleaned—they got removed. Sent out. And the turnaround could be a week or more. In the meantime, the room was effectively dead inventory. No guest, no revenue. For hotels, that wasn’t an inconvenience. It was a slow bleed.

Osborn’s leap was simple and practical: what if the carpet could be cleaned in place, right in the room, and the room could go back on the market that same evening?

In 1923, he built a company around that idea. He called it Economics Laboratory—“economics” on purpose—and launched with a single product: Absorbit. It was made to pull dirt and stains out of carpets quickly enough that hotels could stop choosing between cleanliness and occupancy. The pitch wasn’t “better chemistry.” The pitch was: keep your rooms open.

And from day one, it wasn’t just Osborn. He hired one employee to run the office: Ida Koran. She stayed with the company for decades, and when she died in 1967, she left her estate to create The Ida C. Koran Foundation to support employees. That kind of legacy doesn’t happen by accident. It says something about the culture that formed early.

Absorbit worked—but it was only the opening move. Soon after, Osborn introduced Soilax, a dishwashing soap. And this is where the story starts to sound like modern Ecolab. Soilax wasn’t just a product tossed onto shelves. By 1928, Osborn had developed a chemical detergent specifically for mechanical dishwashers, and with it, a new way of doing business: not selling a chemical, but delivering a system.

Because a restaurant owner didn’t actually want “soap.” They wanted clean dishes, smoother operations, and fewer ugly conversations with health inspectors. Osborn built the business around that outcome. Economics Laboratory didn’t just provide Soilax; they helped get it into the operation, trained people to use it, and kept showing up to make sure it worked as promised. The chemical opened the door. The ongoing service created the relationship.

That systems mindset became the company’s DNA. Competitors sold products and fought over price. Osborn sold results and competed on value—the total benefit to the customer in labor saved, consistency gained, and headaches avoided.

Through the 1930s, even as the Great Depression crushed American businesses, Economics Laboratory kept expanding across the United States. Its customers—hotels, restaurants, food service—couldn’t opt out of cleanliness, even in hard times. By the end of the 1940s, the company had grown to $5.4 million in sales, a meaningful platform for what came next.

Just as important as the growth was the formula behind it: continuous innovation in formulations, paired with expert service delivered by people who understood how the customer’s operation actually ran. Osborn wasn’t building a chemical company. He was building a repeatable way to embed into essential workflows.

By the time the 1940s closed, he’d created something more durable than a hit product. He’d created a template—sell outcomes, wrap them in service, and become hard to replace.

III. Post-War Expansion & Family Business Era (1950s–1970s)

The post-war boom hit like a tailwind. America was building again—more restaurants, more hotels, more everything—and Economics Laboratory was perfectly positioned. But the company’s momentum didn’t come just from being in the right place at the right time. It came from doing what Osborn had baked into the culture: keep innovating, and keep tying that innovation to real operational outcomes.

In 1946, Economics Laboratory introduced the first electronic dishwashing dispenser. On paper, that sounds like a small add-on. In practice, it was a strategic shift. The company was moving from selling consumables to placing equipment inside the customer’s workflow. Once a dispenser was installed, it didn’t just dispense soap—it anchored an ongoing relationship. The chemistry, the service, the refills, the performance. It was the early blueprint of what would later be called a razor-and-blades model, long before anyone turned it into a slide deck.

In 1948 came the first rinse additive, designed to make dishes come out spotless and streak-free. Again, it wasn’t innovation for its own sake. It was innovation aimed at the thing customers actually cared about: consistent results that made the dining experience better and the operation easier to run.

The company also pushed into the consumer world with Electrosol, a home dishwasher detergent that became an immediate hit. For the first time, Economics Laboratory wasn’t only serving institutions and businesses—it was entering American kitchens. Electrosol would stick around as a consumer staple for decades.

Then came the leadership handoff. In 1950, M.J. Osborn stepped down as president but stayed on as chairman, and his son Edward Bartley Osborn took over day-to-day leadership. It was a classic mid-century transition: the founder remains the steady presence, the next generation runs the machine. Under E.B., the company’s ambitions expanded from regional dominance to becoming a broader, more complex corporation.

The biggest step-change in that era was the acquisition of the Magnus Company in the early 1950s. Magnus pulled Economics Laboratory beyond hotels and restaurants and into industrial specialty businesses—pulp and paper, metalworking, transportation, petrochemical processing. These were environments with different equipment, different failure modes, and different stakes. But they shared something crucial: water, cleaning, and chemical management were mission-critical.

And that’s when a bigger truth emerged. The company’s core strength wasn’t “hospitality chemicals.” It was the ability to understand an operation deeply and improve it with a combination of chemistry, equipment, and service. That playbook traveled well—across industries, not just across cities.

International expansion followed. In 1956, Economics Laboratory established its first overseas subsidiary in Sweden, its first real foothold in Europe. In 1957, it became a publicly traded corporation, opening up access to capital markets that could fund more growth, more R&D, and more acquisitions.

The 1960s were about scale and institutionalization. In 1964, the company acquired Magnus Chemical Company, reinforcing and formalizing the industrial push that had begun earlier. That same year, it opened the Merritt J. Osborn Research & Development Center in Mendota Heights, Minnesota. Putting the founder’s name on the R&D center wasn’t just sentimental. It was a statement: as the company grew up, innovation would stay at the center of the identity.

In 1967, the company lost one of its quiet anchors. Ida Koran—the first employee, the person who ran the office in the earliest days—died and, in her will, created The Ida C. Koran Foundation to provide assistance to employees. It was a rare kind of corporate artifact: proof that the culture wasn’t only about customers and growth. It was also about loyalty, and taking care of the people who made the system run.

But by the late 1970s, the family-era model started showing strain. Competition was intensifying, complexity was rising, and by 1978 profit margins had fallen to ten percent. That year, E.B. Osborn ended his tenure as CEO, and the Osborn family stepped away from management of the company they had built.

It was a painful pivot, but it was also the start of a new chapter. Economics Laboratory had outgrown the instincts that built it—relationships, craftsmanship, founder-led judgment. The next phase would demand professional management, tougher capital allocation decisions, and a clearer sense of what the company should be as it scaled globally.

The template was still there. The leadership model was about to change.

IV. The Transformation Years: From Economics Lab to Ecolab (1980s–1990s)

When the Osborn family stepped away in 1978, the company didn’t just lose a CEO. It lost its north star. Professional managers moved in, but for a while the strategy was fuzzy. Economics Laboratory was big enough to have options—and that was the problem. In the late 1970s and 1980s, it went looking for a new identity the way many companies did in that era: by diversifying and hoping the pieces would add up.

One of the first bets was Apollo Technologies, acquired in 1979. It was a step into a business that simply didn’t rhyme with what the company had been built to do. By 1983, Apollo was shut down. The message was clear: growth for growth’s sake was expensive.

A year later came a deal that did fit. In 1984, the company acquired Lystads, Inc., a pest elimination business. Pest control wasn’t a random adjacency—it was another “must-have” for the same customers already buying cleaning and sanitation. If you’re already the trusted partner in the back of the house at a restaurant or hotel, adding pest elimination doesn’t dilute the relationship. It deepens it.

Then came the moment the company made its break with the past. In 1986, Economics Laboratory changed its name to Ecolab Inc. and listed on the New York Stock Exchange. This wasn’t a cosmetic swap. “Economics Laboratory” sounded like a niche Midwestern supplier. “Ecolab” sounded like a global company—science-forward, cleanliness-forward, and ready to sell outcomes at a premium. It was the public declaration that the business was moving from a family-built institution to a modern industrial platform.

But the era’s defining lesson came the very next year, and it came the hard way.

In 1987, Ecolab bought ChemLawn for $376 million. The logic wasn’t crazy. Lawn care looked like it had the ingredients Ecolab understood: recurring service, chemical know-how, a route-based model. On paper, it resembled what had worked in restaurants and hotels.

In reality, it was a different universe. ChemLawn was a residential business, and homeowners don’t buy like institutions do. Commercial customers care about uptime, compliance, and consistency. They stick with what works, and they pay for reliability. Residential customers are more price-sensitive, more transactional, and far less loyal—especially when the “buyer” is making decisions in the driveway, not the boardroom.

Ecolab spent five years trying to make it work. Then, in 1992, it sold ChemLawn to ServiceMaster for $103 million. The financial loss was brutal—roughly $273 million—and the distraction was worse. But the takeaway was invaluable: Ecolab’s edge wasn’t “chemicals plus service” in any setting. It was chemicals, equipment, and expertise delivered into complex commercial and industrial operations where performance actually mattered enough to pay for it.

Not everything in the 1990s was retrenchment. One move in particular aged well. In 1991, Ecolab formed a 50:50 joint venture with Henkel KGaA called Henkel-Ecolab. It was a pragmatic way to expand into Europe and Russia without pretending Ecolab could instantly navigate every local market on its own. Ecolab gained distribution and on-the-ground capability through a partner with deep regional roots. Henkel gained Ecolab’s institutional playbook. And the joint-venture structure gave both sides a way to learn while keeping risk contained.

By the end of the 1990s, Ecolab had finally solved its identity crisis. It would stay in its lane: cleaning, sanitizing, and water treatment for commercial and industrial customers. It would sell outcomes, backed by service, and build relationships that were hard to unwind once embedded in operations.

The company had stopped trying to be everything. Now it was ready to become dominant at something.

V. The Doug Baker Era: Building a Modern Industrial Giant (2004–2020)

Douglas Baker Jr. arrived at Ecolab in 1989, a young marketing executive walking into a company that had finally found its lane—but still hadn’t fully scaled it. Over the next decade-plus, he rotated through marketing and leadership roles that put him close to the real engine of the business: the day-to-day customer relationships that made Ecolab hard to replace. In 2002, he became president and COO. In 2004, CEO. In 2006, chairman. And then he went on a run that, in hindsight, looks almost unreal.

Baker didn’t inherit a broken company. He inherited a good one: profitable, well-positioned, with sticky customers and a service model that already worked. What he built on top of that was something different—an industrial giant with global reach and a moat that kept widening. Over his 16 years as CEO, Ecolab’s market capitalization grew more than eightfold, creating roughly $50 billion in shareholder value.

From 2004 to 2019, the company’s growth wasn’t subtle. Sales climbed to $14.9 billion. Net income rose to $1.6 billion. The share price went from $27.50 to $225. Market value grew from around $7 billion to more than $60 billion. That kind of performance is rare in any era, especially for an industrial company built on chemicals, equipment, and field service.

But the real story wasn’t the scoreboard. It was the move that changed what Ecolab was.

In 2011, Ecolab announced a merger with Nalco, a leader in water treatment and process chemicals. The $5.4 billion deal closed in December 2011, and it was the biggest acquisition in company history—by far. More importantly, it was the most strategically defining.

Nalco expanded Ecolab well beyond its traditional strongholds in cleaning and sanitizing. It brought deep industrial water expertise, process chemistry, and energy-facing services—capabilities designed for complex, high-stakes environments where water isn’t a utility bill. It’s a constraint. The deal also added significant technology and data analytics capability, which helped push Ecolab’s value proposition from “chemistry plus service” toward “systems optimization.”

The strategic logic was straightforward and timely. Water was becoming harder to take for granted. Regulation tightened. Supply risks rose. Public scrutiny increased. Industries that once treated water as an unlimited input were being forced to manage it as a scarce resource. If Ecolab could help customers use less water, treat it better, and prove it with data, it wouldn’t just be a vendor. It would be infrastructure.

Nalco also fit Ecolab’s core playbook: embed in the operation, measure performance, and keep delivering outcomes. Ecolab brought the relationship-driven service machine; Nalco brought industrial water systems expertise at scale. Together, they could become indispensable to customers in a way neither could alone.

After Nalco, Baker pushed further into energy services with the acquisition of Champion Technologies for $2.2 billion in 2012, which closed in April 2013. Champion specialized in oilfield chemistry—products and services used in oil and gas production. It was another step into heavy industry, and another way to diversify beyond the hospitality roots that once defined the company.

Across these moves, Baker was consistent about the message inside Ecolab and out: the company wasn’t selling chemicals. It was selling total value—water savings, energy efficiency, labor reduction, and compliance. The product was just the delivery mechanism. The thing the customer paid for was the outcome. That framing did two things at once: it justified premium pricing, and it raised switching costs for anyone trying to compete on cheaper chemistry alone.

If Nalco reshaped the portfolio, Baker’s other defining contribution reshaped the company’s identity. He pushed sustainability and purpose from the edges to the center of the strategy. Not as a branding exercise, and not as a cost. As an advantage. Customers didn’t just want to run cleaner operations; they increasingly had to. Water reduction saved money and reduced environmental impact. Better chemical efficiency meant less waste and lower cost. Stronger food safety protected public health and brand equity. Ecolab could deliver the operational win and the sustainability win in the same project—and that made it a partner customers could take to their CFO and their board.

Under Baker, Ecolab became a recognized sustainability leader, frequently showing up on lists of the world’s most ethical and most admired companies. That reputation mattered. It attracted customers who were under pressure to improve, and it attracted employees who wanted to work on problems that were both practical and meaningful.

Baker also liked to describe Ecolab as a “technology company,” which sounded strange if you pictured it as just trucks, test kits, and chemical drums. But the label captured where the value was heading. Ecolab was using sensors, automation, data analytics, and software to monitor water quality, adjust dosing, and show customers—often in real time—how their performance compared with targets and benchmarks. Chemistry remained the foundation. Data increasingly became the differentiator.

In 2019, Harvard Business Review ranked Baker 38th on its list of the world’s best-performing CEOs, a nod not just to the returns but to the durability of what he’d built.

When Baker stepped down as CEO at the end of 2020, he left a very different company than the one he’d taken over in 2004: bigger, more global, more technology-enabled, and increasingly aligned with the long arc of the next few decades—water scarcity, sustainability, and the growing premium on doing essential things reliably.

VI. The Bill Gates Investment & Strategic Evolution (2012–Present)

By the early 2010s, Ecolab had become the kind of company that doesn’t usually show up in cocktail-party conversations, but does show up in serious long-term portfolios. And no investor made that more visible than Bill Gates.

Through Cascade Investment and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Gates built a position that at one point made him Ecolab’s largest individual shareholder. In 2012, he already owned 10.8% of the company. Ecolab even amended its stockholder rights plan to allow Gates’ entities to acquire up to 25% of the outstanding shares—an unusual move for any company, especially one with a poison pill. Gates increased his stake toward that cap, a strong signal that he saw something enduring here.

In 2018, he bought another $230 million of shares. By 2022, his stake had fallen to roughly 11%—still enormous, just down from its peak. That drop reflected normal portfolio management and personal circumstances, including Gates’ divorce, rather than any sudden change in how he viewed the business.

So why would Gates, with access to essentially any investment on the planet, concentrate so heavily in what many people would still describe as a cleaning-and-chemicals company?

Water.

Gates has spent years focused on global water challenges: access to clean water, the pressure water scarcity puts on agriculture and industry, and the infrastructure required to treat and distribute water safely. Ecolab sits right in the middle of that. It helps customers use less water, treat it more effectively, and prove safety and performance—often with data, not just promises.

That last point mattered to the investment thesis too. Ecolab wasn’t a commodity chemical supplier waiting to be undercut. It was increasingly a technology-enabled services business with high switching costs and recurring revenue—the kind of durable compounding machine that patient capital tends to love.

And Ecolab kept evolving its portfolio to match that story.

In 2021, it acquired Purolite for approximately $3.7 billion. Purolite makes ion-exchange resins used in biopharmaceutical purification—deep inside life sciences manufacturing, where purity standards are unforgiving and contamination is not an option. That put Ecolab further into a world where “clean” isn’t a preference; it’s a prerequisite. It also fit the company’s long-running pattern: become mission-critical in the customer’s process, and you become very hard to replace.

The Purolite deal pointed to a broader shift. Hospitality and food service would always be core, but some of the biggest growth opportunities were in higher-value, higher-stakes environments—pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and data centers—where water quality and process purity can be existential.

In 2023, Ecolab partnered with and invested in Miso Robotics, which develops automated robotic arms for restaurant kitchens. It was a small bet, but a telling one: if kitchens automate, cleaning and sanitizing have to adapt too. Ecolab wanted a seat at that table early.

Meanwhile, the digital side of the business kept gaining momentum. Ecolab Digital grew to several hundred million dollars in revenue through digital equipment leases, software subscriptions, and data consumption fees. The company’s One Ecolab initiative aimed to spread those capabilities across the entire portfolio, so customers experienced one integrated platform—not a set of disconnected product lines.

And with that came a new kind of moat. Every sensor installed, every water-quality measurement captured, every dosing decision optimized added to Ecolab’s data advantage. The more it operated, the smarter it got. Competitors without that feedback loop weren’t just missing a feature—they were missing the flywheel that kept Ecolab’s outcomes improving.

VII. Leadership Transition & The Christophe Beck Era (2020–Present)

Christophe Beck became Ecolab’s CEO on January 1, 2021, taking over from Doug Baker after one of the strongest runs in the company’s history. Beck wasn’t an outsider—he’d joined Ecolab in 2007 and moved up through the organization—but his roots were different from the classic Ecolab path. Before Saint Paul, he spent 16 years at Nestlé, which meant he arrived with muscle memory for global operations, disciplined execution, and the realities of serving massive customers across international markets.

He also arrived at the most awkward possible moment.

COVID didn’t just rattle Ecolab’s customer base; it pulled it in opposite directions. Hotels closed. Dining rooms went dark. Two of Ecolab’s most iconic end markets—hospitality and restaurants—fell off a cliff almost overnight. At the same time, the world’s obsession with hygiene went into overdrive. Every business, everywhere, suddenly needed to prove it could clean, sanitize, and operate safely.

Ecolab’s response was pragmatic: protect the balance sheet first. The company built a bigger financial cushion, pushing cash reserves up to $1.25 billion to ride out the uncertainty. And this is where the decades of diversification started paying back. Nalco, Champion, and the broader industrial portfolio helped stabilize demand even as restaurants and lodging took the hit. The company wasn’t immune—but it also wasn’t a one-market story anymore.

The leadership handoff kept tightening. On May 5, 2022, Baker stepped down from Ecolab’s board at the company’s annual meeting, closing the loop on the transition and leaving Beck fully responsible for what came next.

Beck’s strategy coalesced around a simple idea with a hard implementation: “One Ecolab.” The premise was that customers don’t experience Ecolab as a set of business units. They experience it as a set of problems—water quality, cleaning and sanitizing, pest pressure, compliance, operational uptime. Under One Ecolab, the company aimed to stop acting like separate product lines and start showing up as one integrated partner. A hospital, for example, shouldn’t have to coordinate multiple Ecolab teams that don’t talk to each other. The goal was a single team that understood the full operation and delivered a unified solution.

That sounds obvious. It’s also brutally difficult when you’ve grown through major acquisitions. Nalco, Purolite, Champion, and a long tail of smaller deals brought valuable capabilities—but they also brought different cultures, systems, and ways of selling. One Ecolab meant doing the unglamorous work of integration: not just trimming costs, but actually getting the organization to operate as one company.

At the same time, Beck leaned harder into the digital direction Baker had set. Ecolab began planning to report digital sales separately in 2025—less a reporting tweak than a signal that “digital” was becoming big enough to stand on its own. Sensors at customer sites, software that analyzes water quality and chemical usage, dashboards that give managers real-time visibility—this wasn’t just modernization. It was recurring, high-margin revenue tied tightly to performance, and it raised switching costs by embedding Ecolab deeper into daily operations.

The growth targets followed the economy’s next wave. Data centers—massive cooling needs, huge water implications—became a clear opportunity. Microelectronics manufacturing, where ultra-pure water and contamination control are non-negotiable, kept expanding. Life sciences continued to demand the purification capabilities that came with Purolite, especially in a world newly sensitized to the importance of pharma supply chains.

As the pandemic shock receded, the business started to show what it can do when volumes normalize. In the fourth quarter of 2024, Ecolab expanded organic operating income margin by 150 basis points. The underlying dynamic was classic Ecolab: the service infrastructure is already built, so when revenue comes back, more of it drops through.

ESG leadership also moved from “nice to have” to a central part of the pitch. Ecolab set targets around water conservation and carbon reduction—not only in its own footprint, but in what it could enable customers to achieve. In a world where companies were being pressed by regulators, investors, and customers to prove environmental responsibility, a partner that could quantify water savings and emissions reductions became not just helpful, but strategically valuable.

In other words, the Baker-to-Beck transition was continuity, not reinvention. The direction stayed the same: technology-enabled services, sustainability as advantage, global reach, relentless focus on outcomes. Beck’s imprint was in the emphasis—tighter integration, clearer digital accountability, and an even more deliberate push into high-value industrial segments where Ecolab can become truly indispensable.

VIII. Business Model Deep Dive: The Power of Recurring Revenue

People love to describe Ecolab as “razor-and-blades.” It’s not wrong—but it misses what makes the model so durable. Ecolab doesn’t just sell chemicals that fit a dispenser. It sells a full operating system: equipment, chemistry, data analytics, and on-the-ground expertise. Each piece makes the others more valuable, and harder to replace.

Take a typical relationship with a hotel chain. Ecolab might handle dishwashing systems in the kitchen, laundry chemistry for housekeeping, pool and spa treatment programs, kitchen hood cleaning, pest elimination, and water treatment for HVAC systems. On the org chart, those are separate product lines. In real life, the customer experiences one partner—one relationship—with someone who understands how hospitality actually runs.

The equipment is usually the first anchor. Once dispensers and monitoring systems are installed, switching isn’t just a new invoice. It’s ripping out infrastructure and retraining staff. The chemicals then become the steady, recurring flow—month after month, year after year. And the service layer is what turns all of that into reliance: a cadence of visits, problem-solving, and constant tuning that makes the customer feel like the system is being managed, not merely supplied. When everything is working, switching providers doesn’t feel “cost-effective.” It feels reckless.

Then there’s compliance—the quiet force that cements the relationship. Health departments inspect restaurant kitchens and hotel pools. Food safety audits scrutinize manufacturing facilities. Environmental regulators watch industrial discharges. Ecolab customers can point to documentation, calibrated equipment, and established protocols. Changing vendors introduces uncertainty at exactly the wrong moment: when you’re trying to prove you have things under control.

Put those together—equipment, chemicals, service, and compliance—and you get retention that’s remarkably resilient. Hotels change owners. Management companies rotate. Procurement teams show up looking for savings. And yet the Ecolab relationship often survives, because the true cost of switching is operational risk, not just higher or lower chemical prices.

Over the last decade, digital has layered on new revenue streams and a new kind of lock-in. Ecolab Digital has grown to several hundred million dollars in revenue through digital equipment leases like connected sensors and dispensers, software subscriptions for analytics platforms and dashboards, and data consumption fees for benchmarking and optimization insights. These tools tie directly into the One Ecolab push: instead of isolated programs, customers get a more unified view of what’s happening across their operations.

Something else starts to happen once you have enough connected sites: a compounding advantage that looks a lot like a network effect. Every site generates data. That data improves Ecolab’s algorithms and recommendations. And that means the next customer benefits immediately from lessons learned across thousands of similar environments. It’s not a social network—but it is cumulative. Competitors without that data can copy the chemistry or the service calls. They can’t easily copy the learning loop.

All of this translates into pricing power. Ecolab isn’t really competing on the cost of chemicals. It’s competing on outcomes where the stakes dwarf the inputs: avoiding a health code violation, preventing contamination, keeping systems running, getting through audits cleanly. When the value delivered is many multiples of the chemical spend, Ecolab can price to that value.

And once the flywheel is spinning, it reinforces itself. Better data enables better service. Better service earns more trust and supports premium pricing. Premium pricing funds more R&D, more sensors, and more data. The system gets smarter. The relationship gets stickier. The cycle tightens.

Looking ahead, Ecolab anticipated around 2% volume growth in 2025, with value pricing adding another 2% to 3%. That’s the tell. The engine isn’t just selling more units—it’s a model where revenue can keep outpacing volume because the company is selling outcomes, not inputs.

IX. Playbook: Key Business Lessons

Ecolab’s story reads like a century-long case study in how to build an indispensable B2B company. Not flashy. Not viral. Just relentlessly focused on becoming part of the customer’s operation.

Systems Thinking Beats Product Thinking. Osborn’s original insight still explains the whole company: customers don’t want chemicals. They want clean carpets, safe kitchens, stable water systems, fewer shutdowns, and an easier time with regulators. The moment you sell outcomes instead of inputs, you stop living and dying by price sheets. You can charge for the value you create—because that’s what the customer is actually buying.

Service as a Moat. Ecolab’s biggest advantage isn’t a secret formula. It’s people. With more than 25,000 field associates around the world, the company has a service footprint that’s extremely hard to recreate. Competitors can copy a detergent. They can’t quickly match a trained, distributed network that knows how a particular hotel’s laundry room runs, how a specific food plant passes audits, or how an industrial site keeps systems in spec. That operational knowledge, delivered on a schedule, turns into trust. And trust turns into switching costs.

Industry Consolidation Strategy. Industrial services are naturally fragmented: local providers, regional specialists, niche technical firms. Ecolab treated that fragmentation like a map of opportunities. The pattern repeated over and over: acquire, integrate, cross-sell, and then apply Ecolab’s broader platform—R&D, procurement scale, and service density—to the acquired customer base. Over time, the compounding effect is powerful: the bigger the platform gets, the easier it becomes to make the next deal work.

Purpose and Profit Alignment. Under Doug Baker, Ecolab leaned into a simple but potent idea: sustainability isn’t separate from performance. It is performance. Helping customers use less water reduces costs and environmental impact. Better chemical efficiency means less waste and lower spend. Stronger food safety protects public health and brand equity. Because the same projects could deliver both economic and environmental wins, Ecolab could pursue ESG goals without trading off returns—and its reputation for that attracted customers and investors who cared about the long game.

The Power of Patient Capital. The company learned two opposite lessons from two very different moves. Henkel-Ecolab showed what patient expansion looks like: partner with a local powerhouse, learn the market, build capability, and only then push toward full ownership. ChemLawn showed what impatience looks like: stepping into a business that didn’t fit, burning time and money trying to force it, and exiting with a painful loss. Together, those experiences helped harden Ecolab’s discipline about where it plays—and how fast it moves.

Geographic Expansion Playbook. That joint-venture-first approach became a repeatable method: enter new regions with a partner, build relationships and local knowledge, and consolidate when the business is proven. It’s slower than charging in alone, but it lowers risk while keeping strategic flexibility.

Technology as an Accelerant. When Ecolab calls itself a technology company, it’s pointing to the next layer of advantage. Chemistry can be matched. What’s harder to match is an integrated digital system: sensors in the field, analytics that turn readings into actions, and software that makes performance visible and defensible. That digital layer doesn’t replace the service model—it supercharges it. And it raises the bar for competitors, who now have to compete not just on formulations and service calls, but on data, insight, and proof.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Future Outlook

The Bull Case

Ecolab sits in a sweet spot that’s rare for an industrial company: it sells things customers can’t afford to “pause.” Cleanliness, food safety, safe water, and compliance aren’t lifestyle choices. They’re table stakes. In a downturn, restaurants will cut advertising before they cut sanitation. Manufacturers will delay expansion plans before they gamble on a water issue that could shut a line down or trigger a regulatory problem.

That “must-have” positioning is why Ecolab can look more resilient than most cyclical industrials. It’s also why management has been willing to put real numbers behind the ambition: confidence in reaching a 20% operating income margin by 2027, with expectations to cross 18% in 2025. The claim isn’t that Ecolab becomes magically immune to gravity—it’s that the model has leverage. Once the service network and installed base are in place, improvements in mix, pricing, and productivity can push profitability upward.

Then there’s the biggest tailwind of all: water scarcity. As fresh water becomes harder to access, more expensive, and more regulated, companies are forced to treat water like a constraint, not a utility. That plays directly into Ecolab’s wheelhouse—helping customers reuse water, optimize it, and document performance. In a world where water gets more complicated, Ecolab gets more valuable.

The growth markets Ecolab is leaning into are also the kinds that don’t tolerate mistakes. Data centers need massive cooling, and that means huge water implications with tight quality requirements. Microelectronics manufacturing depends on ultra-pure water and contamination control. Biopharmaceutical production keeps expanding, and purification standards are unforgiving. These are high-stakes environments where Ecolab’s combination of chemistry, systems expertise, and service can become deeply embedded—and therefore difficult to displace.

If you like mental frameworks, Ecolab checks a lot of the “durable advantage” boxes. Its scale supports large R&D budgets and a dense service network that’s hard to replicate. The installed equipment and operational integration create real switching costs. And while it’s not a social network, there is a compounding effect from data: the more sites Ecolab monitors, the more it learns, and the better it can make recommendations across the fleet. Layer on a century-long reputation in hygiene and safety, and the trust gap versus new entrants is meaningful.

A Porter's Five Forces view points the same direction. Inputs are largely commoditized, so suppliers don’t hold the keys. Buyers have procurement departments, but they’re constrained by compliance requirements and the operational risk of switching. Substitutes are limited because the underlying needs don’t go away. New entrants face a brutal chicken-and-egg problem: you need scale and relationships to win the work, but you need the work to justify building the scale. Rivalry exists, but in many categories Ecolab competes from a leadership position.

The Bear Case

The biggest risk is that Ecolab is not purely a “defensive” story. Its industrial exposure still ties parts of the portfolio to economic cycles. Segments serving manufacturing, oil and gas, and construction can slow sharply in a recession. Nalco and Champion broadened the platform, but they also increased exposure to heavy industry’s ups and downs.

Another pressure point is investment. Capital expenditure is expected to rise to about 7% of sales in 2025, higher than historical levels. That spending supports digital infrastructure and expansion, but it can also compress near-term free cash flow. Even if the investments are smart, the timing can matter for investors used to strong cash generation.

Competition is also real—especially in narrow, high-value verticals. A specialist focused solely on semiconductor water treatment or pharmaceutical purification can sometimes go deeper than a broad platform like Ecolab. The One Ecolab push creates integration advantages, but it also creates a constant balancing act: unify the customer experience without flattening the expertise that wins in technical niches.

And like any company that operates at industrial chemical scale, environmental liabilities are a permanent background risk. Historical issues, changing regulation, or a high-profile incident can bring unexpected costs. Insurance and reserves help, but they don’t erase tail risk.

Finally, there’s integration complexity. Nalco, Champion, Purolite, and many smaller acquisitions created a company with multiple legacy systems and cultures. Making “One Ecolab” real requires sustained, disciplined integration. That work can be value-creating—but it can also distract leadership attention at the wrong time if competitive dynamics shift.

Future Opportunities

AI and automation could meaningfully change the economics of field service. If sensors and algorithms can handle more diagnostics, tuning, and preventative interventions, Ecolab could expand coverage and improve margins at the same time. The Miso Robotics partnership is a small signal, but it points toward an interest in what automation could look like in real customer environments.

Emerging markets remain another long runway. As developing economies industrialize, their hygiene expectations and regulatory regimes often move toward developed-world standards. Many of those same markets also face acute water stress, which creates urgent demand for water-efficiency and treatment capabilities—exactly where Ecolab tends to win.

Life sciences and semiconductors also look structurally durable. Purolite strengthens Ecolab’s position in biopharma purification. Semiconductor manufacturing growth—driven by AI computing demand, reshoring pressure, and electrification trends—continues to pull investment into new fabrication capacity, and that in turn drives demand for ultra-pure water and contamination control.

Climate adaptation is the emerging meta-opportunity. As climate volatility disrupts water availability and industrial operations, companies will need partners that can help them plan, mitigate risk, and operate through constraints. Ecolab’s credibility in water efficiency and resilience positions it as a natural advisor—and potentially a critical operator—in that shift.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For anyone tracking Ecolab going forward, three metrics matter more than the rest:

Organic Revenue Growth is the cleanest read on the underlying engine, separate from acquisitions and currency. If Ecolab can keep posting steady organic growth, it suggests both market demand and the ability to price to value. A meaningful slowdown would be a warning sign—either macro weakness or competitive pressure.

Operating Income Margin is where the model’s promise shows up. The company’s target of 20% by 2027 is a clear scoreboard. Progress toward that goal will reveal whether One Ecolab integration, digital expansion, and mix shift are actually translating into operating leverage.

Customer Retention Rates are the heartbeat of the recurring-revenue story. Ecolab doesn’t provide this in fine detail, so the signal often comes indirectly—management commentary on renewals, customer relationships, and contract dynamics. If retention weakens, it would undermine the switching-cost foundation that makes the whole model so powerful.

XI. Recent News

As of February 2026, the story around Ecolab isn’t a sudden reinvention. It’s continuation—execution, line by line, on the strategy it’s been building toward for years.

Management has kept pointing to the same scoreboard: margins. The company has continued to talk confidently about reaching an 18% operating income margin during 2025, and it has held up the fourth quarter of 2024 as proof of momentum, when organic operating income margin improved by 150 basis points.

Another theme that’s moved from “interesting” to “hard to ignore” is data centers. As AI-driven computing demand ramps, hyperscale facilities are running into a very physical constraint: water and cooling. That dynamic has put Ecolab’s data center services in the spotlight with investors, and management has increasingly framed the category as a meaningful growth vector in recent communications.

The digital narrative is also getting more measurable. Ecolab has signaled that digital revenue reporting would become clearer in 2025, giving investors a more direct window into what “technology transformation” actually means in practice—connected equipment in the field, software subscriptions, and analytics services layered on top of the installed base. The point isn’t that Ecolab is abandoning chemistry and service. It’s that it’s wrapping them in data and proof, and turning that into a bigger, more visible business.

Underneath all of that is capital allocation: the choice to keep investing while still returning capital to shareholders. The planned lift in capital spending to roughly 7% of sales reflects management’s conviction that there are enough high-return opportunities—especially in digital infrastructure and expansion—to justify leaning in now.

XII. Links & Resources

Company Filings - Ecolab Inc. Annual Report (Form 10-K), filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission - Ecolab Inc. Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q), providing interim financial updates - Ecolab Inc. Proxy Statement, detailing executive compensation and governance

Historical References - "Ecolab: A Century of Clean" — company historical materials tracing the evolution from Economics Laboratory - Harvard Business Review CEO rankings (2019), including Doug Baker’s tenure assessment

Industry Analysis - Water scarcity and industrial water treatment market analysis from environmental consultancies - Specialty chemicals industry reports from major investment research providers

Sustainability Documentation - Ecolab Corporate Sustainability Report, published annually with environmental and social metrics - Third-party ESG ratings and assessments from major rating agencies

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music