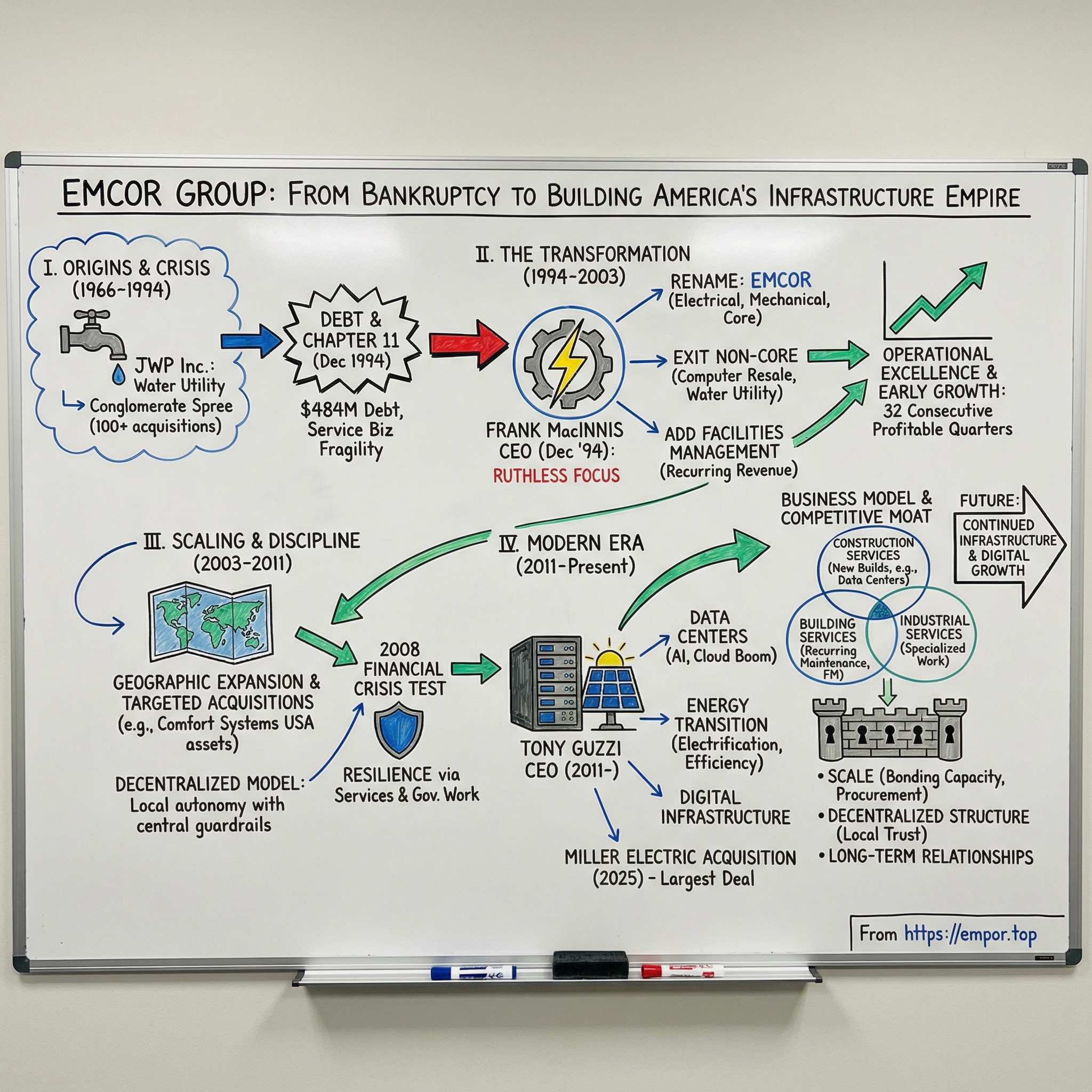

Emcor Group: From Bankruptcy to Building America's Infrastructure Empire

I. Cold Open & Episode Roadmap

Picture the scene: December 15, 1994. In a cramped conference room in the financial district, lawyers slide signature pages across the table while bankers trade tight, exhausted looks. A company that once sprawled across water utilities, electrical contracting, and even computer reselling—a corporate octopus stitched together from more than a hundred acquisitions—is about to re-enter the world.

Not as the same company. More like a patient coming out of surgery: smaller, focused, and alive.

Frank MacInnis, a 54-year-old Canadian with 25 years in construction, had stepped into the CEO role only weeks earlier. What he inherited was brutal: a business buried under $484 million of debt, out of credibility, and on the edge of the kind of collapse that service companies rarely survive. In a manufacturing bankruptcy, you can still point to factories and inventory. In a service business, the real assets are fragile: accounts receivable, customer trust, and the know-how in people’s heads. Once bankruptcy hits, those can disappear fast. MacInnis didn’t just understand that risk. He was staring straight at it.

That day, JWP Inc. officially emerged from Chapter 11 protection. Soon after, MacInnis would rename what remained EMCOR Group—short for electrical, mechanical, and core—and start one of the more improbable turnarounds in American industrial business.

Now jump ahead three decades. EMCOR Group ranks 324th on the Fortune 500, with 2024 revenue of $14.6 billion. Engineering News-Record lists it as the #2 specialty contractor in America. It operates through more than 100 subsidiaries across roughly 180 locations, building and maintaining the systems modern life quietly depends on—data centers running AI workloads, the electrical backbone of hospitals and airports, the mechanical guts of factories and labs.

The question here isn’t just how a failed water utility-turned-conglomerate dodged the graveyard. It’s the more useful one: how did a near-death crisis become the spark for building one of America’s most resilient infrastructure franchises?

The answer runs through ruthless focus, operational discipline, and acquisitions used as a machine—not an ego trip. It’s also about something subtler: turning a cyclical construction business into something that, in its best moments, behaves more like an infrastructure utility.

That’s the story we’re telling—how a company almost died, and chose instead to become something entirely different.

II. Origins: Water, Ambition, and the Road to Disaster (1966-1993)

This story doesn’t start with data centers or power stations. It starts with water.

In 1966, Jamaica Water Supply Company was created to deliver water to Nassau County on Long Island and parts of Queens, New York. It was the kind of business you could build a life around: regulated, steady, and predictably profitable. It didn’t need to be flashy. It just needed to work.

The Dwyer family became central to the company’s early evolution. They also saw the limitation baked into the model: utilities are stable, but they don’t grow fast. If you wanted to build something bigger, you had to use that stability as fuel—cash flow that could bankroll expansion into higher-growth businesses.

The first big leap came in 1971, when the company acquired Welsbach Corp., a Philadelphia-based electrical contractor. On paper, it looked like a smart adjacency. Water, electrical, infrastructure—different pipes, same idea: essential services, built project by project. More importantly, it proved the company wasn’t content to remain a small regional utility.

But the 1970s were messy. By 1978, the company was financially struggling, and Andrew T. Dwyer stepped in to restructure it. The turnaround work stabilized the business. It also seemed to unlock a new mindset: if you could fix a troubled operation, why not buy more of them? Why not keep scaling?

That thinking accelerated through the early 1980s. The rationale sounded elegant: diversify so you’re not dependent on one market, use acquisitions to grow faster than you ever could organically, and blend stable utility economics with the earnings potential of contracting and services.

In 1986, the company made the identity shift official by adopting a new name: JWP Inc. Whatever the initials stood for, the message was clear. This wasn’t a water company with a side hustle anymore. This was a conglomerate.

Then came the binge. Between 1986 and 1992, JWP acquired more than 100 companies. The collection ballooned into a grab bag of businesses with little connective tissue—electrical contractors, mechanical firms, and, most ominously, a computer resale business. The buying had become the strategy.

The clearest example of how far the logic had drifted arrived in 1991, when JWP bought Businessland, a computer reseller. It was framed as a bold step into technology distribution. In reality, it dropped JWP into a brutally competitive market just as the personal computer industry was getting squeezed by commoditization and collapsing margins. Businessland’s model—buy from manufacturers, resell at a markup—was being compressed from every angle.

And while leadership chased new deals, the core business began to fray. Each acquisition came with its own management team, its own systems, its own culture. Integration was inconsistent, and sometimes nonexistent. JWP wasn’t building a stronger organization—it was collecting logos.

By late 1993, the math stopped working. Debt piled up from the buying spree, and operating income wasn’t enough to cover the interest. The instability started to show in the places that matter most for a service business: customers got nervous, talent started leaving, and the company’s most valuable “assets”—relationships and trust—began to evaporate.

JWP’s ambition had been to assemble a diversified infrastructure empire. Instead, it buckled under what one observer called “an acute case of acquisition indigestion and a crushing load of debt.” The company that once kept Long Island’s taps running couldn’t keep its own finances from running dry.

At this point, there were only two possible endings: extinction, or a complete reinvention.

III. The Crisis Years: Bankruptcy & The Search for a Savior (1993-1994)

In 1993, JWP’s board ran out of options. The debt was unpayable, confidence was draining out of the business, and the company’s sprawl—water utilities on one end, a computer reseller on the other—didn’t add up to a strategy anymore. So they did the thing boards wait too long to do, right up until they can’t avoid it: they launched a “major restructuring effort.”

In plain English, they filed for Chapter 11.

That filing kicked off the real fight: a negotiation with JWP’s creditors, a coalition of about 50 bankers, insurers, and equity funds holding $484 million of the company’s debt. They weren’t sentimental, and they weren’t passive. They understood the basic math of a busted conglomerate: liquidate it and everyone loses; reorganize it and there’s at least a chance to save something.

The deal they struck reflected that reality. Creditors swapped the $484 million they were owed for $180 million of new debt and, critically, 100 percent of the equity. The old shareholders didn’t get diluted—they got erased. JWP, for all practical purposes, now belonged to its lenders.

But ownership doesn’t keep the lights on. Leadership does.

And bankrupt service companies are uniquely fragile. A manufacturer can point to factories and inventory. A service business is different. The assets that matter are people, customer relationships, and accounts receivable. Bankruptcy threatens all three at once: good employees leave for safer paychecks, customers move their work to firms that feel stable, and receivables get harder to collect the moment counterparties sense weakness.

The new owners needed someone who understood that clock was ticking. They turned to Frank MacInnis.

MacInnis was 54, Canada-born, and a 25-year veteran of the construction world, much of it in oil and gas—an environment where execution, safety, and logistics aren’t nice-to-haves, they’re survival skills. He was hired about a month after the Chapter 11 filing, which tells you how urgent the situation had become. And he was clear-eyed about what he’d walked into. Later, he put it bluntly: “I don't know of a larger service company that's ever survived Chapter 11 reorganization. The financial assets of a service organization consist predominantly of their accounts receivable, and those tend to decline in quality very quickly.”

That wasn’t drama. It was the playbook for how these stories usually end.

MacInnis’s real problem wasn’t just getting JWP through court. It was deciding what, exactly, was worth saving. Years of acquisition had left the company bloated, incoherent, and impossible to manage as one organism. Bankruptcy didn’t merely allow a rethink—it demanded one. What gets sold? What stays? What’s the core business that can still win customers and keep crews busy?

By late 1993 and into 1994, the pieces for a turnaround were finally on the table: radically reduced leverage, new owners who’d already taken their losses and now needed a survivor, and an operator with enough industry credibility to make painful calls fast.

Now it came down to execution.

IV. The MacInnis Transformation: Phoenix from the Ashes (1994-1995)

Frank MacInnis spent his first months as CEO the way you’d expect an oil-and-gas construction veteran to: with a hard hat mentality and a scalpel approach. He wasn’t trying to “optimize” JWP. He was trying to save what could be saved.

Over the next year, he sold off dozens of businesses—starting with the distractions and moving quickly to anything that didn’t fit a tight definition of what the company could be. The computer reseller was out. Peripheral operations were out. And in the most symbolic move of all, he effectively jettisoned JWP itself—the corporate shell that had enabled the acquisition spree—along with the rest of the conglomerate baggage.

On December 15, 1994, the company reached the “Effective Date” and officially emerged from Chapter 11. On paper, that meant the court process was done. In reality, MacInnis knew it only bought them the right to attempt a second act.

By early 1995, the second act had a name: EMCOR Group Inc. It wasn’t chosen to sound aspirational. It was chosen to be limiting. EMCOR—electrical, mechanical, and core—was the company announcing, in three words, what it would do and what it would not do. No more water utility identity. No more dabbling in unrelated industries. No more “diversification” for its own sake.

This wasn’t just a rebrand. It was a strategy reset built around a simple observation: if you want to be essential to the built world, electrical and mechanical systems are where the action is. Every major facility depends on them. And while construction is cyclical, the expertise is scarce—and valuable. MacInnis wasn’t trying to own a random collection of businesses. He was trying to own a position in projects that had to get done right.

The company also moved its headquarters from Rye Brook, New York, to Norwalk, Connecticut. It wasn’t a dramatic distance change. It was a psychological one. Rye Brook belonged to the old story. Norwalk would be where the new one started.

Then came the move that would make the model more resilient: MacInnis added facilities management to the mix. The logic was straightforward. New construction can swing from boom to bust. But buildings don’t stop needing to run. They still need maintenance, upgrades, and ongoing operation. Facilities management created a steadier stream of work—a counterweight to the construction cycle.

It also changed the customer relationship. Construction could win you the job. Facilities services could win you the next decade.

In 1996, EMCOR completed the clean break with its origin story by selling Jamaica Water Supply—the water utility that had launched the entire enterprise back in the 1960s. With that sale, the last vestige of “Jamaica Water” as a corporate identity was gone. EMCOR was now what MacInnis said it was: an electrical-and-mechanical services company, built for the long haul.

What MacInnis pulled off in 1994 and 1995 wasn’t a gentle turnaround. It was controlled demolition. And bankruptcy, for once, helped. In normal times, every legacy business has a constituency. Every bad acquisition has an internal defender. In Chapter 11, the debate ends. Survival becomes the strategy.

MacInnis succeeded because he didn’t try to preserve the old company’s shape. He kept what was valuable—capabilities, operating talent, real customer-facing work—and cut the rest until the organization could actually function. And that focused combination—electrical and mechanical construction, plus recurring facilities services—became the foundation EMCOR would build on for decades.

V. Building the Machine: Operational Excellence & Early Growth (1995-2003)

What came next was almost hard to believe. After emerging from Chapter 11 in December 1994, EMCOR went on a run of quarter after quarter where income beat the same quarter the year before—27 straight at first, eventually stretching into the early 2000s. From 1995 through 2003, the company stacked 32 consecutive profitable quarters. For any contractor, that kind of consistency is rare. For a company that had just crawled out of bankruptcy, it bordered on surreal.

The obvious question is: how?

MacInnis didn’t “turn things around” with a slogan. He built a system. The core idea was simple: keep the company focused, run it with operational discipline, and make the revenue mix less fragile.

Facilities management did a lot of the heavy lifting. Construction is lumpy—jobs start, jobs finish, budgets get frozen, cycles turn. But buildings don’t stop existing in a downturn. Hospitals still need their HVAC maintained. Corporate campuses still need systems kept running. Those service contracts created a steadier base of recurring work that helped EMCOR ride out the natural volatility of construction.

He also widened the map. Geographic expansion wasn’t about planting flags—it was risk management. If one region slowed, another might still be hot. The more national the footprint became, the more EMCOR could lean into stronger markets without being trapped by weaker ones.

The United Kingdom became an early test of that playbook. EMCOR built facilities management operations there, learning how to operate in a different regulatory and customer environment while developing muscle it could apply across the broader business.

Then, in 1998, EMCOR made a move that looked less like contracting and more like platform strategy: it formed a special purpose entity with CB Richard Ellis, the world’s largest seller, broker, and manager of real estate. The logic was elegant. CB Richard Ellis had the buildings. EMCOR could help keep them running. Instead of fighting for the same customer relationship, the two companies could bring a combined offering that was stronger than what either could deliver alone.

Importantly, acquisitions returned—but with a completely different posture than the old JWP days. These weren’t grab-bag deals to chase growth. They were targeted additions meant to deepen the core.

In 2002, EMCOR bought 19 companies from Comfort Systems USA, a move that gave it meaningful presence in the Midwestern construction and services market. Later that year, it added Virginia-based Consolidated Engineering Services Inc. The pattern was clear: expand geographically, add capabilities, and do it without overwhelming the organization or stretching the balance sheet beyond what the business could actually support.

By 2003, the industry had stopped viewing EMCOR as a reorganized survivor and started treating it like a first-tier operator. That year, it was named one of “America’s Most Admired Companies” by Fortune, ranked 37th on Barron’s “Top 500 Best Performing Companies,” and received the Frost & Sullivan Competitive Strategy Award. Less than a decade after Chapter 11, the comeback wasn’t just real—it was widely acknowledged.

MacInnis described the approach as “growth through diversity.” But this time, diversity didn’t mean unrelated industries. It meant diversification inside the core: different geographies, end markets, and customer types, all anchored to the same electrical, mechanical, and facilities-services foundation.

That 1995–2003 stretch mattered for more than bragging rights. It proved the new EMCOR wasn’t a one-time bankruptcy rescue—it was a repeatable machine. Acquire smart. Operate tightly. Balance project work with recurring services. And keep the whole thing centered on what the company could actually be great at.

Even the bankruptcy stakeholders learned the lesson in real time. The creditors who took control in the reorganization—trading down their debt in exchange for ownership—ended up holding equity in a business that became worth far more than the obligation they’d written down. That’s what happens when the turnaround isn’t cosmetic. It’s structural.

VI. The Scale Game: Acquisitions & Geographic Expansion (2003-2011)

By 2003, EMCOR had stopped being “the company that survived bankruptcy” and started being something more dangerous: a repeatable operator with a formula. But having a formula and scaling a formula are two different things. MacInnis’s “growth through diversity” strategy—expand services, widen geography, push into new end markets—only worked if EMCOR could get bigger without drifting back into the sloppy, deal-chasing habits that killed JWP.

So the next eight years became a test of discipline.

Acquisitions kept coming, but the posture was completely different from the old days. EMCOR wasn’t buying companies to tell a growth story; it was buying to fill in a map and deepen a capability set. Each deal had to earn its place. Did it strengthen EMCOR in a market where it was underweight? Did it add a service the company could scale across the rest of the network? Did it come with a proven track record of profitability—and leadership that fit EMCOR’s way of operating?

That last part mattered because EMCOR’s real edge wasn’t just what it did. It was how it was organized.

Instead of trying to mash every new business into one corporate machine, EMCOR ran a decentralized model built around operating subsidiaries. They kept their local brands, their customer relationships, and meaningful autonomy. Norwalk’s role was different: financial oversight, capital allocation, strategic guardrails, plus the kind of support smaller contractors can’t easily create on their own—things like bonding capacity and procurement leverage. The work, the relationships, and the day-to-day judgment stayed close to the field.

That structure did a few important things at once. It protected the entrepreneurial DNA that makes good contractors win. It avoided the most common M&A failure mode—breaking what you just bought by “integrating” it to death. And it made the company easier to scale, because EMCOR didn’t need to reinvent itself every time it acquired another specialized operator.

Then came 2008.

When the financial crisis hit, commercial construction didn’t just slow down—it seized up. Credit tightened, customers froze capital spending, and new project starts collapsed across much of the industry. Contractors that lived and died by new builds suddenly found themselves staring at an empty pipeline.

This was exactly the scenario MacInnis had been preparing for since the mid-1990s. EMCOR’s facilities management business kept producing revenue when new construction disappeared. Geographic spread helped, too; some regions got hit harder than others, and the company wasn’t trapped in any single local economy. And it had exposure to government and institutional customers—hospitals, universities, federal facilities—places that still had to operate, still had systems that needed to run, and couldn’t simply shut down because the economy was ugly.

MacInnis didn’t use the crisis as an excuse to abandon the strategy. If anything, the downturn reinforced it. While weaker competitors struggled, EMCOR had the stability to keep moving—and the opportunity to pick up assets at more attractive prices. Coming out the other side, it was stronger relative to the field than it had been going in.

By 2011, MacInnis had been at the helm for nearly 17 years. He was 71, and the next question wasn’t whether EMCOR could survive a recession. It was whether the company he built could outlast him.

In January 2011, MacInnis retired as CEO, staying on as chairman until 2015 to provide continuity. Tony Guzzi—who had joined EMCOR in 2004 and served as Chief Operating Officer—stepped into the CEO role. The handoff was quiet by design. Guzzi wasn’t a departure from the playbook; he was proof the playbook had been institutionalized. He’d spent years inside the system, learning the culture and operating philosophy that made EMCOR work.

For investors, the 2003–2011 stretch answered the big scaling question. EMCOR stayed disciplined through an economic shock, stuck with the acquisition approach without turning reckless, and preserved the decentralized model that kept local operators sharp. And when the founder of the turnaround stepped aside, the company didn’t wobble. It kept going—because it wasn’t just a MacInnis story anymore. It was an EMCOR story.

VII. The Modern Era: Data Centers, Energy Transition & Digital Infrastructure (2011-Present)

Tony Guzzi took over a company that had already survived the worst-case scenario and proven it could scale without losing control. But the world EMCOR was built to serve was changing again—this time in a way that played directly into its strengths. Computing moved to the cloud. AI drove demand for ever-more processing power. Buildings got retrofitted for efficiency. The grid began a long upgrade cycle. And across all of it sat the same bottleneck: the electrical and mechanical systems that make modern infrastructure actually work.

The clearest tailwind was the data center boom. Hyperscalers like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud started building huge campuses to support cloud computing, AI workloads, and an economy that was rapidly going digital. Data centers aren’t just big buildings. They’re reliability machines. They need electrical systems that can deliver massive loads with near-zero tolerance for failure, cooling systems that can manage constant heat, and layers of backup, fire protection, and controls that all have to function perfectly, all the time.

That is exactly the kind of work EMCOR was designed for. Under Guzzi, more of the company’s big projects clustered around data centers, along with similarly demanding facilities like semiconductor plants, biotech and life sciences labs, and pharmaceutical manufacturing—places where electrical and mechanical expertise isn’t a commodity, it’s the difference between operating and going dark.

At the same time, the energy transition opened another lane. Solar, battery storage, EV charging, and grid modernization all require the kind of electrical capability EMCOR had been building for decades. The construction services division expanded its role in power infrastructure, including work at power stations and sustainable generation such as photovoltaic systems.

And once again, acquisitions stayed central—just calibrated to the moment. In July 2023, EMCOR announced an agreement to acquire ECM Holding Group, Inc., an energy-efficiency specialty services firm. ECM’s focus was retrofit work—HVAC, lighting, water systems, weatherization, airflow management—the practical, payback-driven projects building owners pursue when energy costs rise and emissions targets get real. With estimated 2023 revenue of $60 million, it wasn’t a “bet the company” swing. It was EMCOR adding capability right where demand was building.

The biggest move came in January 2025: EMCOR announced a definitive agreement to acquire Miller Electric Company for $865 million in cash. Miller Electric was a leading electrical contractor across the fast-growing Southeastern U.S.—a region benefiting from population growth, manufacturing reshoring, and a surge of data center development. It was EMCOR’s largest deal ever, and it sent a clear message: electrical infrastructure wasn’t just a good business line. It was becoming the business line.

By mid-2025, the numbers showed the strategy wasn’t theoretical. In second quarter 2025 results reported July 31, EMCOR posted a 17.4% year-over-year revenue increase to $4.3 billion. The engine was U.S. electrical construction and facilities services, up 67.5% versus the prior-year quarter. HVAC aftermarket work also grew strongly, helped by energy-efficiency retrofits, building controls upgrades, and the simple reality that climate systems don’t get optional when budgets tighten.

Step back and you can see the pattern: multiple trends reinforcing each other. Data center construction stayed hot as AI workloads ramped. Energy-transition spending was supported by incentives and corporate commitments. And the country’s aging building stock kept demanding upgrades and maintenance—work that doesn’t disappear just because the economy gets nervous.

Scale mattered more in this era, too. EMCOR’s bonding capacity helped it qualify for the biggest projects, the kind that smaller contractors can’t even bid. Its purchasing power improved economics on equipment and materials. And its national footprint let it chase work across the country while still showing up with local operators who understood their markets.

By the time investors looked at EMCOR in the 2010s and 2020s, it wasn’t just “a contractor.” It was a platform sitting at the intersection of data centers, electrification, energy efficiency, and industrial build-outs. The real question wasn’t whether these forces would keep compounding. It was whether EMCOR could keep doing what it had done since Chapter 11: stay disciplined, allocate capital intelligently, and capture the upside without relearning the painful lessons of its past.

VIII. Business Model & Competitive Moat

EMCOR’s business looks complicated from the outside—more than a hundred subsidiaries, dozens of end markets, work that ranges from brand-new builds to keeping 30-year-old systems alive. But underneath, it’s a deliberately balanced machine built around three segments.

Construction services generate about two-thirds of revenue. This is the high-profile work: electrical and mechanical scope on new buildings, expansions, and major renovations. Building services bring in roughly a quarter, covering the ongoing operation, maintenance, and upgrades that start the day the ribbon gets cut. Industrial services make up the rest, focused on specialized work for manufacturing and industrial customers.

Construction services is where EMCOR installs the stuff you don’t notice unless it fails. On the electrical side: power distribution, lighting, and fire alarm systems—and, increasingly, the complex infrastructure inside data centers and technology-heavy buildings. On the mechanical side: HVAC, plumbing, and the kind of precise climate control demanded by labs, hospitals, and advanced manufacturing. This segment will always rise and fall with capital spending and the economy. The way EMCOR reduces that risk is by not being a one-trick contractor. It’s spread across healthcare, education, government, commercial, industrial, and more—so a slowdown in one pocket doesn’t automatically mean the whole engine stalls.

Building services is the stabilizer. Buildings age. Systems drift out of spec. Efficiency standards change. Controls get upgraded. Equipment wears out. Even in a downturn, the work doesn’t disappear—it just shifts from “build the new thing” to “keep the existing thing running.” Facilities management contracts also tend to be multi-year, and that recurring revenue matters. If a hospital hands over operations and maintenance to EMCOR and the relationship works, it can last a very long time—through budget cycles, leadership changes, and construction booms and busts.

Industrial services adds another layer of diversification. Manufacturing plants and industrial facilities have their own maintenance needs, shutdown schedules, and specialized requirements. Those cycles don’t always line up with commercial construction, which gives EMCOR a different demand curve to lean on when one market softens.

Then there’s the operating model—one of the most important parts of the moat. EMCOR runs through more than 100 operating subsidiaries across roughly 180 locations, and that decentralization isn’t a quirk. It’s the system. Each business keeps its local identity, relationships, and operational autonomy. To customers, it still feels like dealing with a trusted local contractor—because, in practice, they are. But behind that local face is a much larger company that can provide financial strength, support, and staying power.

Government relationships deepen that advantage. EMCOR serves agencies including the National Archives and Records Administration, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Government Accountability Office. Federal work tends to be less sensitive to the ups and downs of private development, which adds stability. And it’s not easy work to win: it demands compliance muscle, security protocols, and credibility earned over time—barriers that naturally keep out a long tail of smaller competitors.

Scale brings two more structural edges: bonding capacity and procurement.

Big projects require performance bonds—essentially a guarantee that the contractor will finish the job as promised. Bonding companies cap how much exposure they’ll take on any one contractor, which means bonding capacity can limit what you’re even allowed to bid. EMCOR’s size and financial strength let it pursue projects that smaller contractors can’t touch, regardless of talent.

Procurement works the same way. When EMCOR negotiates with equipment makers and materials suppliers, it does so as a massive national buyer. Those price and availability advantages don’t show up as a single dramatic moment. They compound—job after job, year after year—into real margin and execution benefits.

Put it together, and the most important takeaway is coherence. After bankruptcy, EMCOR didn’t just simplify—it aligned the business so each piece feeds the others. Construction wins the customer and builds the installed base. Building services monetizes that installed base for years. Industrial services adds specialized capability and a different demand cycle. And the decentralized structure keeps the company close to local markets while still capturing the advantages that only scale can buy.

That’s the post-Chapter 11 lesson, made permanent: not diversification for its own sake—but a focused portfolio that makes the whole stronger than the parts.

IX. Playbook: Lessons in Corporate Turnarounds

EMCOR’s arc—from a bankrupt conglomerate to a Fortune 500 infrastructure platform—reads like a turnaround case study. But the reason it’s useful isn’t because it’s tidy. It’s useful because the lessons were learned under pressure, with real consequences, not in a classroom.

First: a crisis creates permission for radical action.

In normal times, big companies almost never make clean breaks. Every business line has internal champions. Every legacy decision has a story attached to it. And even when the numbers are screaming, inertia wins—especially when acquisitions become a habit. That’s what happened at JWP. The buying continued even as the debt load became dangerous, because stopping would have meant admitting the strategy was wrong.

Bankruptcy ended the debate. Once the old order collapsed, MacInnis could do what would’ve been politically impossible before: sell entire divisions, exit business lines, and shrink the company back to something coherent.

Second: focus isn’t a slogan; it’s the foundation.

JWP tried to be everything at once—a water utility, an electrical contractor, a computer reseller, plus dozens of other unrelated operations. The result wasn’t diversification. It was confusion. EMCOR worked because MacInnis narrowed the identity to what the company could actually be great at: electrical, mechanical, and facilities services. That focus made it possible to build real expertise, create a consistent operating culture, and make decisions that reinforced the core instead of diluting it.

Third: M&A isn’t the villain. Undisciplined M&A is.

Both JWP and EMCOR used acquisitions as a growth tool. The difference was intention and restraint. JWP bought indiscriminately, piling up more than 100 companies in six years without a coherent strategic logic or the ability to integrate what it owned. EMCOR bought with a purpose—adding specific capabilities, filling geographic gaps, and expanding the core, while structuring deals to preserve what made the acquired businesses valuable in the first place.

The lesson isn’t “don’t do deals.” It’s “only do deals you can absorb and that make the core stronger.”

Fourth: decentralize the work, centralize the guardrails.

One of EMCOR’s most durable advantages is its hybrid structure. Operating subsidiaries keep real autonomy, so they can stay close to customers, move fast, and retain the entrepreneurial energy that makes contractors win locally. But headquarters holds tight control over what can sink the enterprise: financial standards, bonding relationships, and strategic direction. It’s a model built to scale without losing discipline.

Fifth: build in revenue that doesn’t vanish when the cycle turns.

Construction is volatile. You can be executing perfectly and still get hit by a downturn that freezes project starts. EMCOR’s addition of facilities management—recurring work tied to operating and maintaining buildings—gave the business a stabilizer. When new construction dried up, the installed base of buildings still needed to run. The 2008 financial crisis made that trade-off impossible to ignore.

Sixth: in service businesses, culture is an asset.

In manufacturing, value can sit in plants and equipment. In services, the real assets are people, know-how, and trust. That’s why EMCOR’s approach to acquisitions mattered so much: preserving local cultures wasn’t just about being nice. It was about protecting the relationships and expertise that customers were actually paying for.

Seventh: long-term thinking compounds.

MacInnis led EMCOR for 17 years, long enough to execute a multi-decade strategy instead of chasing quarterly reinventions. And the succession to Tony Guzzi wasn’t a scramble—it was planned, staged, and steady, designed to keep the operating system intact. In a world where CEO tenures have shortened, that continuity became part of EMCOR’s competitive advantage.

Put together, those principles explain how a bankrupt roll-up became a resilient infrastructure franchise. And they offer a filter for spotting other real turnarounds: a moment of crisis that forces truth, a strategy that narrows to what can actually win, operational discipline, and leadership with the patience to let the transformation stick.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Competitive Analysis

The bull case for EMCOR is basically a pile-up of long-duration tailwinds—all of them pointing straight at electrical and mechanical work.

Start with data centers. As AI workloads ramp, the world needs an astonishing amount of new computing capacity, and that doesn’t magically appear in the cloud. It gets built in the physical world, in facilities that demand relentless uptime, massive power delivery, redundant systems, and sophisticated cooling.

Layer on the energy transition. Grid modernization, renewable generation, and electric vehicle charging all translate into one core requirement: more electrical infrastructure, built and maintained by firms that can execute at scale.

Then add manufacturing reshoring. When production moves back to the U.S., it brings with it new plants, expansions, and retrofits—exactly the kind of complex industrial environments where electrical and mechanical systems are mission-critical.

EMCOR doesn’t just benefit from these trends; it has a way to compound them. Its M&A playbook has been tested across cycles: buy businesses that strengthen the core, keep what makes them successful locally, and use the larger platform—bonding, procurement, capital—to help them grow. In an industry that’s still fragmented, that combination of scale and discipline makes EMCOR a natural consolidator.

The bear case is less about whether EMCOR is well run and more about the realities of the business it’s in.

Construction is still the majority of revenue, and construction spending can drop hard in recessions. Facilities management helps smooth the ride, but it doesn’t repeal the cycle. The 2008 financial crisis showed both sides of that coin: services can hold up, while new project work can suddenly get scarce. A severe downturn would likely pressure results, even if it didn’t threaten the company’s long-term viability.

Labor is another structural risk. The skilled trades—electricians, HVAC technicians, pipefitters—are in tight supply, with experienced workers aging out and fewer younger workers entering the field. EMCOR competes for the same talent as everyone else in construction and industrial services. If wages and training costs rise faster than pricing power, margins get squeezed.

And then there’s execution risk on large projects. Fixed-price contracts can punish contractors when materials spike, labor gets scarce, or site conditions surprise you. In this business, a small number of badly estimated jobs can erase the profits from a lot of well-run ones. EMCOR’s history suggests strong estimating and controls, but the risk is never fully gone.

Competition is real, and the big names have different angles. Quanta Services is heavily oriented around utility and telecommunications infrastructure. MasTec plays across communications and energy. Comfort Systems USA overlaps directly in HVAC and mechanical services. EMCOR’s differentiation is the combination: broad geography, real scale, and a mix that balances construction with recurring services.

If you run the industry through Porter’s Five Forces, the structure is generally attractive. Barriers to entry are high—bonding capacity, technical expertise, track record, and relationships take years to build. Supplier power is meaningful but not overwhelming, since no single vendor controls the ecosystem. Buyer power varies: government and institutional customers can be stickier, while commercial customers can be more price-driven. And substitution is minimal. There’s no workaround for needing electrical and mechanical systems installed and maintained by professionals.

Using Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, you can see why EMCOR has held up so well. Scale shows up in procurement and bonding capacity. Process power shows up in its repeatable acquisition-and-integration muscle. Switching costs show up in facilities management—changing providers is disruptive and risky for customers. And there’s a subtle reinforcing loop between construction and services: build the systems, then stay in the account maintaining and upgrading them.

Wall Street’s view reflects that logic. As of early 2026, eight analysts covered EMCOR, with five buy ratings and two holds, and an average target price of $681.7. Their models anticipated roughly high-single-digit annual revenue growth from fiscal 2024 through 2027, with operating income growing faster and margins expanding modestly—essentially a bet that scale, mix, and execution continue to translate into operating leverage.

For investors watching EMCOR, two signals matter more than most. First, how the mix shifts over time—specifically, whether building services grows as a share of total revenue, which would usually mean steadier, higher-quality earnings. Second, whether the electrical construction business is growing organically, especially in end markets like data centers and energy infrastructure. Track those consistently, and you’ll see the real story: whether EMCOR is capturing the secular wave without sacrificing the discipline that turned a bankruptcy survivor into a compounding infrastructure platform.

XI. Epilogue: What's Next for America's Infrastructure Play

The data center boom that powered EMCOR’s recent growth hasn’t faded. If anything, AI has raised the stakes. These facilities don’t just need more servers; they need an entirely more demanding layer of support around them—power delivery built for extreme density, cooling systems engineered for relentless heat, and an electrical backbone designed to fail never. That sits right in EMCOR’s wheelhouse, and it puts the company in the flow of what could become the biggest infrastructure buildout since the internet era went physical.

Running alongside it is a second wave with similar gravity: the energy transition. Electrifying transportation, heating, and industrial processes doesn’t happen with policy memos. It happens with substations, upgraded distribution networks, and years of real work in the field. Renewable generation adds another hard requirement: new transmission to connect remote solar and wind projects to where people actually live and consume power. And battery storage—critical to smoothing the intermittency of renewables—brings its own set of complex electrical and mechanical demands, the same kinds of systems EMCOR has spent decades installing and maintaining.

Then there’s the industry structure itself. Specialty contracting is still highly fragmented, filled with strong regional players that hit natural ceilings: they can’t bid the biggest jobs without more bonding capacity, they can’t always serve major institutional clients at scale, and many face a looming succession problem as founders and longtime owners look to step back. That’s where EMCOR’s acquisition machine keeps finding fuel. When it buys well-run operators, it can expand geography and capability without smothering what made them successful—because the model is designed to keep decisions close to the local business while the parent provides the financial strength and guardrails.

The Miller Electric deal announced in January 2025 is a clean example of that playbook. By bringing in a leading Southeastern electrical contractor in an $865 million all-cash transaction, EMCOR deepened its presence in one of the country’s fastest-growing regions—right where data centers and industrial buildouts have been accelerating.

Zoom out, and EMCOR’s arc remains one of the more useful turnaround stories in modern American industry. It didn’t go from bankruptcy to the Fortune 500 through a single clever move. It did it through crisis-forced clarity, years of disciplined execution, and the patience to let a strategy compound. Frank MacInnis led for 17 years, then handed off to Tony Guzzi without drama—exactly the kind of continuity most roll-ups and turnarounds never achieve.

In the end, EMCOR is a story about building through crisis. Not just surviving a near-fatal collapse, but using it as the trigger to become something sturdier than what came before. A small water utility became a sprawling conglomerate, the conglomerate imploded, and what emerged was a focused infrastructure services platform that now sits in the middle of America’s biggest build cycles. Whatever the next decade brings, the foundation laid in those desperate months of 1994 and 1995 has already proven it can carry a lot of weight.

XII. Recent News

EMCOR’s biggest headline in the last year came on January 14, 2025: the company announced a definitive agreement to acquire Miller Electric Company for $865 million in cash. Miller Electric’s footprint sits in the fast-growing Southeastern U.S., a region that’s been pulling in exactly the kinds of projects EMCOR has been built to win—data centers, new manufacturing capacity, and major infrastructure work. It was EMCOR’s largest deal ever, and it read like a straightforward statement from management: electrical demand isn’t a spike. It’s a wave they expect to keep riding.

A few months later, the operating results backed that up. In its second quarter 2025 earnings, reported July 31, EMCOR posted revenue of $4.3 billion, up 17.4% from the prior-year quarter. The standout was U.S. electrical construction and facilities services, which surged 67.5% year over year—lifted by large data center work and energy-related projects. HVAC aftermarket work also held up well, supported by the unglamorous but durable drivers that keep showing up in this story: energy-efficiency retrofits, building controls upgrades, and customers investing to make existing facilities run better.

Meanwhile, the earlier ECM Holding Group acquisition—announced in July 2023—kept moving from “deal” to “capability.” Through 2024 and into 2025, EMCOR continued integrating ECM’s energy-efficiency retrofit operations, expanding what it could offer customers who were increasingly prioritizing sustainability-driven upgrades across HVAC, lighting, water, weatherization, and airflow management.

XIII. Links & Resources

If you want to go straight to the source, start with EMCOR’s SEC filings. The annual 10-Ks are where the full story lives: how each segment performed, what got acquired, what got sold, and what management says could go wrong. The quarterly 10-Qs fill in the cadence—how the year actually unfolded, quarter by quarter. And the proxy statements are the closest thing you’ll get to the company’s internal wiring: executive compensation, governance structure, and the kinds of shareholder issues that surface as a business gets bigger and more institutional.

For industry context, Engineering News-Record’s annual Top 600 Specialty Contractors list is the scoreboard. It’s where you can see, in plain terms, how EMCOR stacks up against peers in specialty contracting. Fortune’s annual ranking is the broader lens—less about the trade and more about EMCOR’s place among America’s largest companies.

For the origin story—the collapse of JWP and the early days of the EMCOR reboot—the most revealing material comes from contemporary trade and business press coverage from 1993 to 1995. Those articles capture what hindsight tends to smooth over: the uncertainty, the credibility gap, and the very real skepticism that a service-heavy contractor could survive Chapter 11 and come out stronger.

To understand the market forces EMCOR operates inside, construction-sector research and industry commentary help frame the basics: labor availability, pricing dynamics, backlog trends, and how competition actually plays out in electrical and mechanical contracting. Trade associations like Associated Builders and Contractors and the National Electrical Contractors Association also publish regular updates on industry conditions and workforce development—critical context in a business where the limiting factor is often skilled labor, not demand.

And for the modern growth engine—data centers—technology and infrastructure research is the bridge. Analyst coverage of hyperscaler capex, regional data center development, and the infrastructure demands of AI workloads helps explain why “electrical and mechanical” has become one of the most strategically important layers of the digital economy.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music