Edwards Lifesciences: The Heart Valve Innovation Story

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

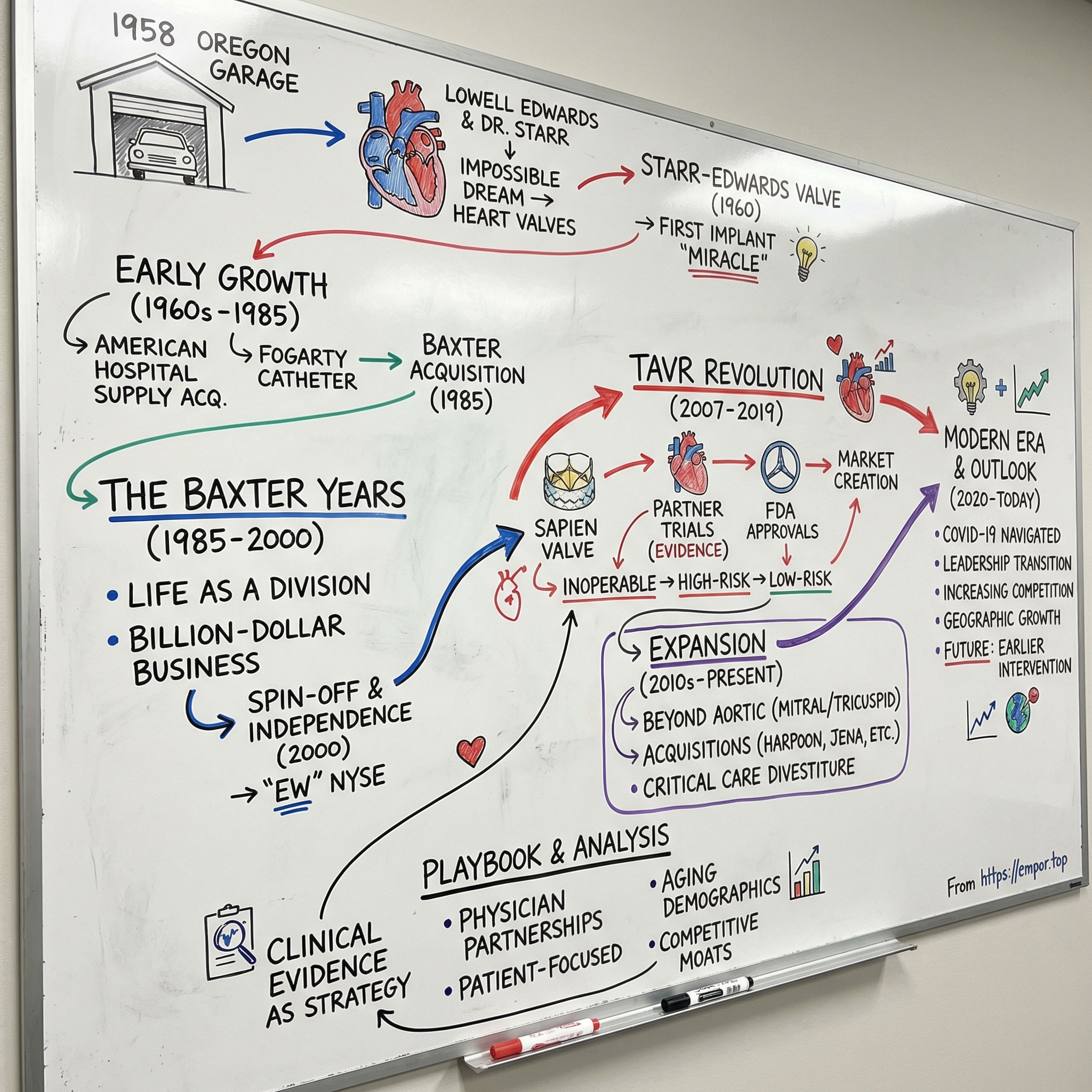

Picture a retired engineer in his sixties, working out of a modest garage in Oregon in 1958, convinced he could build something that had never existed: an artificial heart. While most people his age were settling into golf and fishing, Miles “Lowell” Edwards was sketching pumps, thinking in hydraulics, and obsessing over one question: what if you could keep a failing human heart going with machinery?

Nearly every cardiologist he approached dismissed the idea. It sounded like science fiction—reckless, even. But that stubborn vision didn’t disappear. It evolved. And in time, it became Edwards Lifesciences: a company now worth more than $40 billion, and one that has reshaped the way the world treats heart disease.

In 2024, Edwards generated $5.44 billion in revenue. Its breakthrough technology—transcatheter aortic valve replacement, better known as TAVR—has treated hundreds of thousands of patients who once faced a brutal choice: open-heart surgery or no real option at all.

Today, Edwards is headquartered in Irvine, California. It’s best known for artificial heart valves and hemodynamic monitoring—tools that help clinicians measure what’s happening inside the cardiovascular system in real time, and intervene when it’s going wrong. But this isn’t just a medical device story. It’s a story about how an entire field gets built from scratch—one improbable partnership, one clinical leap, and one decade-long bet after another.

So how did a garage inventor’s impossible dream turn into the foundation of modern structural heart therapy? How did this business survive years inside corporate parents, then emerge in a spin-off to become a category-defining leader? And what does Edwards’ TAVR dominance reveal about the economics—and the grind—of medical innovation?

That’s where we’re going. We’ll trace the arc from that Oregon garage to today’s catheter labs and operating rooms: the early valve breakthroughs, the long middle years under Baxter, the spin-off that created modern Edwards, and the TAVR revolution that changed cardiovascular medicine. Along the way, we’ll pull apart the business model, the competitive landscape, and what the next decade might hold for a company sitting at the intersection of aging demographics and relentless innovation.

II. The Founding Story: Lowell Edwards & Dr. Starr (1958–1960s)

A Retired Engineer's Impossible Dream

In the late 1950s, Miles “Lowell” Edwards didn’t look like the person who was about to change cardiac surgery. He was an engineer—hydraulics, fuel pumps, systems that moved fluid under pressure. In 1958, he’d retired to Oregon. The normal script at that point was quiet days and a comfortable fade-out.

Edwards didn’t fade out. He fixated on an idea that sounded like pure science fiction at the time: building an artificial heart.

He started teaching himself the human body the way an engineer learns a machine. He read anatomy. He dug into medical journals. He filled notebooks with sketches and mechanisms. And he kept coming back to the same simplification that everyone else seemed unwilling to entertain: the heart is a pump. If pumps can fail and be repaired, why not this one?

Medicine, however, didn’t share his optimism. Edwards went from cardiologist to cardiologist, pitching a vision he could already see in his head. Again and again, he got the same response: no. The heart was too complex. The risk was too high. And, unspoken but unmistakable—who was this retired engineer to think he belonged anywhere near the operating room?

The Meeting That Changed Everything

Eventually, Edwards found someone who didn’t dismiss him: Dr. Albert Starr, a young cardiac surgeon at the University of Oregon Medical School. Starr was in his early thirties, early in his career, working at the frontier of open-heart surgery—where the rules weren’t settled and the future still felt up for grabs.

When they met in 1958, Edwards showed up with his drawings and his conviction. Starr listened. Then he did something that ended up being the real breakthrough: he redirected the dream.

A total artificial heart, Starr told him, was out of reach. The surgery was too complex. Materials weren’t good enough. The physiology wasn’t understood well enough. Not yet.

But Starr also saw Edwards’ gift immediately. If Edwards wanted to take on a heart problem that could actually be solved, there was one sitting right in front of them: valves. Valve disease was common and deadly. Valves calcified, leaked, or stopped opening properly—and patients died because of it. Replace the valve, and you could save the patient.

Edwards agreed. On the spot, the mission changed from “replace the heart” to “replace the part that’s failing.” They formalized the partnership with $5,000 in initial capital. Edwards would tackle design and manufacturing. Starr would bring clinical judgment, surgical skill, and access to patients.

It was a simple division of labor. It was also the blueprint for the entire modern medical device industry.

Two Years to a Miracle

What followed happened fast—almost unnervingly fast, given what they were attempting. Within two years, they had a workable device: the Starr-Edwards mitral valve, a ball-in-cage design.

The mechanism was deceptively simple. A silicone ball moved within a metal cage. Blood flow pushed it open in one direction, and pressure sealed it shut to stop backflow. It turned a biological one-way gate into an engineered one.

On August 25, 1960, Starr implanted the first Starr-Edwards mitral valve into a human patient. The surgery worked. The patient lived. And the device performed the job it had been built to do.

For the first time, a mechanical device had successfully replaced a human heart valve.

The story exploded beyond medicine. Newspapers around the world called it “miraculous.” It wasn’t just that the patient survived; it was the implication. A failing part of the heart could be replaced—like a component in a machine. The public couldn’t look away.

Building Edwards Laboratories

Success created its own problem: demand. Surgeons wanted the valve. Hospitals wanted supply. And Edwards’ garage-workshop reality wasn’t going to carry a global medical breakthrough.

So in 1961, he established Edwards Laboratories in Santa Ana, California—built specifically to manufacture artificial heart valves. Now the challenge shifted from invention to execution: producing medical-grade devices consistently, training surgeons on a brand-new procedure, and building distribution channels into hospitals that had never stocked anything like this before.

Through the 1960s, the Starr-Edwards valve became the standard in mechanical valve replacement, used in thousands of procedures. And the durability could be astonishing. One early patient lived 48 years with a Starr-Edwards implant before needing a replacement—an almost unbelievable lifespan for a piece of mid-century engineering inside a beating heart.

Edwards never forgot the original dream, though. Even after the valve took off, he continued working on the total artificial heart. He pursued it until his death in 1982. He didn’t get all the way there—but in chasing it, he and Starr had created something that mattered just as much: the foundation for an industry, and a company that would spend the next six decades turning heart repair from impossibility into routine.

And it started with one unlikely partnership: an engineer who could build, and a surgeon who could see what to build first.

III. Early Growth & Acquisitions Era (1960s–1985)

The Corporate Transition

By the mid-1960s, Edwards Laboratories had done the hard part: it had proved a mechanical heart valve could work, and the Starr-Edwards design was spreading through operating rooms around the world. Now came the part that breaks a lot of young med-tech companies—scaling. Making a few devices for pioneering surgeons is one thing. Building reliable manufacturing, meeting hospital demand, and expanding distribution is another.

In 1966, American Hospital Supply Corporation bought Edwards Laboratories. The company became American Edwards Laboratories, plugged into a parent with deeper pockets and a much wider commercial footprint. Lowell Edwards stayed involved, but the center of gravity shifted: the mission was no longer just invention. It was industrialization.

It’s a familiar med-device arc. The breakthrough tends to come from a small, founder-led team. The next phase—regulatory work, manufacturing discipline, global sales—often takes a bigger platform.

Beyond Valves: Building the Product Portfolio

Inside American Hospital Supply, American Edwards started to look less like a one-product miracle and more like an emerging cardiovascular franchise. The business expanded into balloon catheters for cardiovascular procedures and oxygenators used in heart-lung bypass. It also brought in other catheter technologies, including the Fogarty catheter—a clot-removal device that became a standard tool in vascular surgery.

This wasn’t diversification for diversification’s sake. These products all lived in the same world: the same surgeons, the same hospitals, the same operating rooms. Each addition deepened relationships, widened the catalog, and made the company harder to displace.

The Fogarty catheter was a perfect example of what American Edwards could do well. Dr. Thomas Fogarty—an inventor-physician in the same mold as Lowell Edwards—had created a simple, elegant solution: a balloon catheter that could be threaded through vessels, inflated, and used to pull out clots. Before that, the alternative often meant invasive surgery. American Edwards helped take that invention and scale it into standard practice.

Building Expertise Through Acquisitions

At the same time, the company kept pushing deeper into valves—especially the next major branch of the family tree: tissue-based bioprosthetic valves. Working with pioneering surgeons like Alain Carpentier and Delos Cosgrove, American Edwards developed valves made from animal tissue rather than metal and plastic.

The tradeoff was straightforward, and it reshaped the market. Mechanical valves were durable, but they could trigger clotting, forcing many patients into lifelong anticoagulation therapy and its bleeding risks. Tissue valves were more biocompatible and often avoided the need for long-term blood thinners—but they tended to wear out sooner.

That meant choice. With the Carpentier-Edwards valve line, American Edwards could offer mechanical valves for patients who could tolerate long-term anticoagulation, and tissue valves for older patients or those who couldn’t. This portfolio approach—matching the device to the patient—became a core part of the company’s competitive strategy.

The Baxter Acquisition

Then, in 1985, the corporate story took another turn. Baxter International acquired American Hospital Supply Corporation, bringing American Edwards into the Baxter empire.

For the cardiovascular business, it meant more scale—and more distance from the top. Baxter was building a diversified healthcare products company spanning intravenous solutions, blood products, and broad hospital supplies. American Edwards was important, but it was now one piece inside a much larger machine.

Still, the period from the late 1960s through 1985 had quietly done something crucial. It took Edwards from a garage-born breakthrough and turned it into a global cardiovascular business with multiple product lines, deeper surgeon relationships, and real operating muscle.

And that foundation would matter—because the most transformative chapter was still ahead, first inside Baxter, and then, eventually, back out on its own.

IV. The Baxter Years: Building Under a Conglomerate (1985–2000)

Life as a Division

Inside Baxter International, the Edwards cardiovascular business gained real advantages—and inherited real friction.

The advantages were straightforward. Baxter brought global distribution, seasoned regulatory muscle, and the balance sheet to fund the kind of clinical work and R&D that can overwhelm smaller med-tech companies. If you wanted to run trials, expand internationally, and build manufacturing at scale, being part of Baxter made that easier.

But the constraints were just as real. Conglomerates run on portfolio logic: every division competes for capital, executive attention, and strategic patience. Edwards was profitable and growing, but it wasn’t the whole story inside Baxter—it was one business line among many, and not always the loudest voice in the room.

Still, the cardiovascular division kept building. It advanced surgical valve designs, expanded into hemodynamic monitoring, and rounded out the ecosystem of instruments and accessories that hospitals need to do these procedures safely and consistently. The Swan-Ganz catheter—used in intensive care to monitor cardiac function—became a major product alongside the valve franchise, anchoring Edwards more deeply in the hospital, not just the operating room.

Building Toward a Billion-Dollar Business

By the late 1990s, through leading brands like Bentley, Carpentier-Edwards, Cosgrove-Edwards, Fogarty, Research Medical, Starr-Edwards, and Swan-Ganz, the Edwards business had grown to nearly a billion dollars a year in sales.

That’s enormous—especially for a category built on clinically complex products that require surgeon trust, training, and long-term outcomes data. But within Baxter’s larger portfolio, it still read like “one division,” not “the company.”

And strategically, the mismatch was hard to ignore. Heart valves and monitoring systems are high-margin, evidence-driven, relationship-heavy businesses. Baxter’s historical strengths were closer to the other end of the spectrum: high-volume, disposable hospital products. The cardiovascular unit didn’t fit Baxter’s center of gravity, culturally or operationally, even if it performed.

The Decision to Spin Off

By the end of the 1990s, Baxter started to ask a question that shows up again and again in corporate history: is this business worth more—and better—on its own?

A few forces pushed Baxter in that direction. The cardiovascular device industry was moving fast, with minimally invasive techniques beginning to threaten the old way of doing things. Capturing that shift would take focus, investment, and leadership attention that’s hard to sustain inside a diversified parent.

At the same time, the stock market had started to favor focus. Investors increasingly rewarded “pure-play” companies, where the story was clean and the strategy was singular. A standalone Edwards could be valued differently than the same business tucked inside a conglomerate.

And then there was speed. Big-company process can be an asset for safety and compliance—but it can also become drag. Edwards needed to make decisions quickly in a field where the pace of innovation was accelerating.

So Baxter moved toward separation, ultimately choosing a tax-free spin-off structure—giving shareholders direct ownership in both Baxter and the newly independent Edwards.

V. The Spin-Off & Independence (2000)

A Tax-Free Dividend

The separation became official on March 31, 2000. Baxter executed the spin-off as a tax-free dividend: for every five shares of Baxter stock held on March 29, shareholders received one share in the newly formed Edwards Lifesciences Corporation.

It was designed to be clean. Edwards left with its products, people, and manufacturing operations. Baxter kept the rest. And for the first time in more than three decades—after living inside American Hospital Supply and then Baxter—the business that began with Lowell Edwards’ sketches had its own identity again.

Edwards Lifesciences started trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “EW.”

Michael Mussallem Takes the Helm

A spin-off isn’t just a financial maneuver. It’s a leadership test. Baxter tapped Michael Mussallem as founding CEO, betting that someone who’d grown up inside the Edwards organization could now run it as a standalone public company.

Mussallem joined the Edwards business in 1989 and moved through roles spanning R&D, manufacturing, and divisional leadership. That range mattered. Edwards wasn’t a business you could run from a spreadsheet. Success depended on understanding how engineering decisions ripple into clinical workflows, how regulatory pathways shape timelines, and how physician relationships are earned one case at a time.

Just as important, Mussallem had a point of view about where heart care was going next. He believed transcatheter technologies—devices delivered through blood vessels rather than through an open chest—could change the standard of care. Inside Baxter, that kind of long-horizon bet had to compete with a lot of other priorities. As an independent company, Edwards could finally choose its own constraints.

Early Challenges

Independence also meant exposure. Edwards was now a mid-sized company in a field full of giants, and it had to stand up all the infrastructure that Baxter used to provide—public company governance, investor relations, and standalone systems and processes.

Then came the inevitable messiness of divorce. Edwards and Baxter entered arbitration over separation-related issues, creating distractions for management and uncertainty for investors. Those disputes were resolved over time, but they pulled attention away during a period when focus was at a premium.

And the timing didn’t help. Edwards hit the public markets right as the dot-com bubble peaked. When the market rolled over, skepticism rose across the board—especially toward newly public companies. Edwards had to do two hard things at once: deliver consistent performance quarter to quarter, while still investing heavily in the future.

The Strategic Foundation

Still, the spin-off did what it was supposed to do: it gave Edwards the autonomy to build a strategy around what it did best, rather than what fit inside a conglomerate portfolio.

As an independent company, Edwards could make three bets that would have been harder under Baxter.

First, it could stay tightly focused on structural heart disease and critical care—areas where it had deep expertise and where the patient need was obvious.

Second, it could invest aggressively in transcatheter technology before the market was fully proven. That required patience, risk tolerance, and a willingness to fund years of development and clinical evidence-building.

Third, it could shape a culture purpose-built for med-tech innovation: engineering excellence, close clinical partnerships, and rigorous regulatory execution—all operating in concert.

The March 2000 spin-off was the start of modern Edwards Lifesciences. What came next—the TAVR revolution, the push into mitral and tricuspid therapies, and Edwards’ rise into one of the most valuable franchises in medical devices—traced back to this moment, when the company finally had the independence to place its biggest bets.

VI. The TAVR Revolution: Sapien Changes Everything (2007–2019)

The Big Bet on Transcatheter

To understand why transcatheter aortic valve replacement—TAVR—was such a shock to the system, you first have to remember what “normal” looked like for aortic stenosis.

Severe aortic stenosis means the aortic valve turns stiff and narrow. Blood can’t get out of the heart efficiently. Patients get short of breath, dizzy, exhausted. And without a fix, they decline fast.

For decades, the fix was open-heart surgery. The chest is opened, the heart is stopped, the patient goes on a heart-lung machine, the diseased valve is cut out, and a new one is sewn in. For many patients, that operation worked. But a huge number of aortic stenosis patients weren’t “many.” They were older. Frailer. Burdened with other conditions. And for them, open-heart surgery could be less a cure than a death sentence.

So they lived with it—until they couldn’t. Their valve kept narrowing, their symptoms worsened, and eventually, they died.

TAVR offered a different path. Instead of opening the chest, a physician threads a catheter through a blood vessel—often from the leg—guides it to the heart, and deploys a new valve inside the old one. No stopping the heart. No bypass. A procedure measured in hours, not an ordeal measured in weeks.

The idea had been floating around since the 1980s. But turning that idea into a repeatable, safe therapy meant solving a brutal set of engineering problems all at once. The valve had to collapse small enough to travel through a catheter, then expand perfectly at the target. It had to stay put without stitches. And it had to work immediately, in a beating heart, the moment it opened.

Edwards started working toward that future in the 1990s—first through research partnerships, then through a more focused internal effort. It was a classic Edwards move: make a long, expensive bet before the market is obvious, and then build the evidence to make it inevitable.

The SAPIEN Platform

In 2007, the first SAPIEN transcatheter heart valve received commercial approval in Europe. That matters for two reasons.

First, it marked the moment TAVR moved from experimental to real clinical use. Second, it highlighted a recurring dynamic in med-tech: Europe’s CE marking process generally moves faster than the U.S. FDA, so Europe often becomes the first proving ground for new device categories.

SAPIEN’s design was balloon-expandable. The valve sat crimped down on a balloon catheter. Once it reached the diseased valve, the balloon inflated, expanding the new valve to full size. The old valve leaflets were pushed aside, and blood flow had a new, functional pathway.

Those early approvals were aimed at the only patients where the math was undeniable: people considered inoperable. If the alternative is essentially “we can’t help you,” a risky new procedure can still be the most ethical option on the table.

The PARTNER Trial

But a device category doesn’t become standard of care on clever engineering alone. It becomes standard of care when the data leaves no room to look away.

Edwards sponsored the PARTNER trial—Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves—one of the defining clinical programs in structural heart history. It enrolled multiple patient groups, including people who were inoperable and those considered high risk for surgery.

For inoperable patients, PARTNER compared TAVR against medical management—basically supportive care without valve replacement. For high-risk patients, it compared TAVR directly to surgical aortic valve replacement.

The results landed like a gavel. In inoperable patients, TAVR dramatically improved survival compared to medical therapy at one year—on the order of a 20-point mortality difference. These were patients who previously had no real path forward, now living longer and feeling better. In high-risk patients, TAVR held its own versus surgery, delivering comparable outcomes with a far less invasive approach.

Published in the New England Journal of Medicine and showcased at major cardiology meetings, PARTNER did more than validate a product. It validated a new way of treating heart disease.

FDA Approval and Market Expansion

In November 2011, the FDA approved the Edwards SAPIEN transcatheter aortic heart valve for transfemoral delivery in inoperable patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. It was the first U.S. commercial approval for a transcatheter device that enabled aortic valve replacement without open-heart surgery.

The label was narrow by design. But strategically, it was everything: a beachhead in the United States. Edwards could now scale commercial adoption, build physician experience, and generate the real-world evidence needed to expand into broader populations.

That expansion started quickly. In 2012, the FDA extended approval to high-risk surgical patients. Overnight, the eligible population grew, and the procedure moved from “last resort” to “credible alternative.”

Meanwhile, the technology kept iterating. Edwards rolled out newer generations—SAPIEN XT, then SAPIEN 3—each improving deliverability and sealing and reducing complications like paravalvular leak. Every generation made the procedure more consistent. More predictable. More widely adoptable.

From High-Risk to Low-Risk

The ultimate prize, though, was low-risk patients: the majority of the aortic stenosis population. These were people who could survive open-heart surgery. But if outcomes were comparable, why put anyone through a cracked chest and weeks of recovery when a catheter-based procedure could get them home in days?

To earn that shift, Edwards had to do the hardest kind of work in medicine: prove equivalence, then prove superiority, across broader and broader groups. Trials in intermediate-risk patients showed TAVR could match surgery. Then came the pivotal low-risk studies—head-to-head comparisons in patients who had a legitimate choice.

On August 16, 2019, the FDA approved the Edwards SAPIEN 3 and SAPIEN 3 Ultra Transcatheter Heart Valve systems for patients at low risk for death or major complications from open-heart surgery. With that, TAVR completed one of the most consequential expansions in modern device history: from “too sick for surgery” to “nearly everyone with severe aortic stenosis.”

Building a Billion-Dollar Franchise

Commercially, the TAVR story wasn’t just a hit product. It was market creation.

From its first European approval in 2007, Edwards helped build TAVR into a multi-billion-dollar franchise within roughly a decade. That growth wasn’t simply taking share from surgical valves—it was unlocking treatment for patients who previously never made it to the operating room at all.

It also reshaped hospital workflow. Catheterization labs, long centered on coronary interventions, became the new hubs for structural heart procedures. And it forced a cultural shift in medicine: interventional cardiologists moved into valve therapy, and cardiac surgeons increasingly worked side-by-side with them in the cath lab environment.

Edwards leaned hard into that transition. The company invested heavily in training—building programs, proctoring, and playbooks to help teams do the procedure safely and consistently. That wasn’t just good medicine. It was good strategy. Training created trust, standardized practice, and made Edwards harder to displace.

By the end of the 2010s, TAVR had become Edwards’ defining engine—driving growth, funding the next wave of R&D, and cementing the company’s position at the center of structural heart. The dream that started with a mechanical valve in 1960 had evolved into something bigger: a new default way to fix a failing heart without ever opening the chest.

VII. Innovation Portfolio Expansion (2010s–Present)

Beyond the Aortic Valve

Once TAVR had moved from “breakthrough” to “standard of care,” Edwards did what great category creators do next: it went looking for the next category.

The obvious targets were the heart’s other valves. The mitral valve—between the left atrium and left ventricle—touched an even larger patient population than aortic stenosis. And the tricuspid valve, historically overlooked and under-treated, represented one of structural heart’s biggest pockets of unmet need.

But mitral and tricuspid disease didn’t come with the same clean geometry as the aortic valve. The anatomy is more complex. The mechanics are different. And the clinical playbook is less standardized. If TAVR was hard, transcatheter mitral and tricuspid therapies were harder—and they would demand new technologies, new procedural approaches, and years of clinical proof.

Edwards went after this in two ways at once: internal R&D to extend what it already did well, and acquisitions to bring in capabilities it didn’t have.

The Harpoon Acquisition

In 2017, Edwards acquired Harpoon Medical of Baltimore, Maryland, for $100 million. Founded in 2013, Harpoon had built a minimally invasive surgical system to repair the mitral valve in patients with degenerative mitral regurgitation.

Harpoon’s approach wasn’t “replace the valve.” It was “fix what’s broken.” In many mitral regurgitation patients, the problem is the chordae tendineae—the thin, fibrous “chords” that tether the valve leaflets to the heart muscle. When they stretch or rupture, the leaflets prolapse and blood leaks backward.

Harpoon enabled surgeons to implant artificial chords through a small incision, with the heart still beating. Different procedure, different skill set, different technology stack—but aimed at the same strategic goal: keep Edwards at the center of how structural heart disease gets treated.

Critical Care Divestiture

Edwards also made a big decision about focus—specifically, what it was willing to leave behind.

Its critical care business, built around hemodynamic monitoring and products like the Swan-Ganz catheter, had been part of the company’s identity since the Baxter era. It was real, meaningful hospital infrastructure. But as structural heart became the growth engine, critical care started to look less like a core pillar and more like a side quest.

In 2024, Edwards agreed to divest its critical care business to Becton, Dickinson and Company (BD). The logic was simple: concentrate entirely on structural heart, and free up capital to invest in what Edwards believed would define its next decade. It wasn’t a retreat from profitable products. It was a statement of confidence in where the company thought the future was.

Accelerating Acquisitions

With that focus sharpened, Edwards leaned harder into dealmaking. In 2024, it announced three major acquisitions.

First: Innovalve Bio Medical, for approximately $300 million. Innovalve was developing transcatheter mitral valve replacement technology—an important complement to Edwards’ repair efforts, because not every mitral valve can be repaired.

Then: JenaValve Technology and Endotronix, for a combined $1.2 billion. JenaValve added more transcatheter aortic valve technology, including approaches for patients with pure aortic regurgitation—where the valve leaks rather than narrows. Endotronix brought remote patient monitoring capabilities, aimed at improving how heart failure patients are tracked and managed over time.

Put together, these moves showed where Edwards was headed. Not just “make the valve.” Build the full structural heart toolkit—intervention, adjacent indications, and better follow-up after the procedure.

CAS Medical and Monitoring

This wasn’t a sudden shift. Earlier, in April 2019, Edwards acquired CAS Medical Systems of Branford, Connecticut, for approximately $100 million. CAS Medical specialized in cerebral oximetry—monitoring brain oxygen levels during surgery.

In hindsight, CAS Medical sits at an interesting point in the story. It came before the later decision to exit critical care, reflecting how Edwards’ thinking evolved as structural heart grew larger and more central.

Across these deals, the pattern stayed consistent: Edwards used the cash flows generated by TAVR to buy time, talent, and technology—extending its platform into new valves, new conditions, and new steps in the patient journey. The play wasn’t diversification for its own sake. It was reinvesting a franchise win into the next set of structural heart growth engines.

VIII. Modern Era & Market Position (2020–Today)

Navigating COVID-19

Then the world hit pause.

COVID-19 didn’t just stress hospitals; it reordered them. Elective procedures were delayed or canceled as systems triaged beds, staff, and supplies for the pandemic. Many patients delayed care too—sometimes because their hospital simply wasn’t doing non-emergency cases, and sometimes because the idea of walking into a medical facility felt dangerous.

For Edwards, that translated into a sharp, temporary drop in TAVR volumes in early 2020. Catheter labs went quiet. Schedules cleared. And a business built around procedure growth suddenly faced the opposite problem.

But valve disease doesn’t wait for a better news cycle. Patients who postponed treatment still had the same narrowing valves, the same deteriorating cardiac function, and the same trajectory. As hospitals adapted—and as the initial shock of the pandemic eased—those patients returned. Volumes came back.

COVID also pulled forward a few trends that, over time, played to Edwards’ strengths. Telemedicine moved from novelty to default, opening more room for remote follow-up and monitoring in chronic cardiovascular care. Hospitals doubled down on minimally invasive capabilities, in part because shorter stays and faster recoveries mattered more than ever. In that environment, a therapy like TAVR looked even more attractive than it already did.

By 2021 and 2022, Edwards’ business had recovered and returned to growth. The pandemic created a violent dip—but it didn’t change the underlying story: populations were aging, valve disease was rising, and TAVR had become the modern standard for treating severe aortic stenosis.

Leadership Transition

In 2023, Edwards marked the end of an era and the start of another. Bernard Zovighian became CEO, succeeding Michael Mussallem, who had led the company from the 2000 spin-off through the entire build-out of the TAVR franchise. Mussallem moved into the role of Executive Chairman—still involved, but no longer running the day-to-day.

Zovighian was an inside choice. He joined Edwards in 2007 and held leadership roles across regions and product lines. That mattered because Edwards wasn’t looking for a reinvention story; it was looking for execution. The strategy was already in motion: defend and extend TAVR, expand into mitral and tricuspid therapies, and keep widening the structural heart platform.

The handoff signaled confidence. Edwards believed the franchise was strong, the next pipeline bets were worth funding, and the company’s edge would come from staying disciplined as the market got more crowded.

Competitive Dynamics

Because by now, Edwards was no longer alone.

Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific all built competing transcatheter valve platforms. Medtronic’s CoreValve family leaned on a self-expanding approach, rather than Edwards’ balloon-expandable design. Abbott grew its position through acquisitions, including structural heart assets that came with St. Jude Medical. Boston Scientific entered the category through dealmaking as well, assembling a portfolio to compete in a market Edwards had helped create.

As more credible options reached hospitals, the dynamics changed fast. Pricing pressure increased as health systems gained negotiating leverage. Product cycles sped up as competitors raced to narrow performance gaps and differentiate on deliverability, outcomes, and ease of use. And clinical evidence became a competitive weapon—trials and registries weren’t just about proving safety and efficacy anymore; they were about winning mindshare.

Edwards held leadership through a set of advantages it had spent years compounding. Its clinical evidence base was deep, anchored by the PARTNER program that shaped the category’s adoption curve. Its physician training infrastructure was mature, creating relationships and muscle memory that are hard to dislodge. And it had built a reputation for consistent manufacturing quality—an edge that matters enormously when the product is implanted in a beating heart.

But the key point was this: leadership now had to be defended. Edwards couldn’t coast on being first. In a market full of giants, staying ahead required constant reinvestment.

Expanding Indications

In 2024, Edwards pushed TAVR into a new frontier: the FDA approved TAVR for people with severe aortic stenosis who had not yet developed symptoms.

That might sound like a small nuance, but it’s a major shift. Historically, the trigger to intervene wasn’t just “the valve is severely narrowed.” It was “the patient is severely narrowed and symptomatic”—shortness of breath, chest pain, fainting, clear signs the disease was disrupting daily life.

The challenge is that severe aortic stenosis can be deceptively quiet. Some patients don’t notice symptoms because the decline is gradual, or because they unconsciously reduce activity to avoid getting winded. And when symptoms do show up, they can arrive abruptly—sometimes after the disease has already advanced significantly.

This approval opened the door to treating patients earlier, before that inflection point. Edwards framed it as part of a broader push toward earlier intervention, arguing “there is an urgent need to change practice and TAVR guidelines for the treatment of aortic stenosis patients.” In plain terms: if you can fix the valve safely before the crash, you should.

Geographic Expansion

At the same time, Edwards kept playing the long game geographically. Growth in the U.S. and Western Europe was meaningful, but emerging markets offered the kind of multi-decade runway that can reset a category’s ceiling.

China was a particular focus: a huge population, a rapidly modernizing healthcare system, and millions of patients who could ultimately benefit from valve therapy. Edwards worked to secure regulatory approvals, build local distribution, and train physicians in transcatheter techniques—because in structural heart, adoption isn’t just selling a device. It’s building a capability inside hospitals.

India, Japan, and other Asian markets were also priorities, each with their own obstacles—different reimbursement realities, regulatory processes, and clinical norms. But the common tailwind was consistent: aging populations and a clear clinical advantage for minimally invasive treatment over traditional surgery.

Manufacturing and Supply Chain

None of that expansion works without manufacturing that can scale—and scale safely.

Edwards grew its manufacturing footprint across multiple continents, with major sites in the United States, Europe, and Singapore. That geographic spread added resilience, helped manage supply chain shocks, and positioned production closer to key markets.

But for heart valves, manufacturing isn’t just about capacity. The quality bar is unforgiving. These devices have to perform flawlessly, immediately, and for years. A defect isn’t an inconvenience; it can be catastrophic.

So Edwards kept investing in process discipline: better manufacturing technology, stronger quality systems, and continuous improvement. Decades of operational rigor became a competitive advantage in their own right—one that doesn’t show up in a product brochure, but absolutely shows up in physician trust.

IX. Playbook: Business & Innovation Lessons

Clinical Evidence as Strategy

Edwards’ biggest strategic advantage wasn’t just that it built a better valve. It was that it proved—over and over—that the valve worked.

In medical devices, you don’t win by telling a story. You win by generating data that changes minds, changes guidelines, and eventually changes what hospitals consider “normal.” The PARTNER program took years and cost hundreds of millions of dollars, but it gave Edwards something competitors couldn’t quickly copy: a towering evidence base tied directly to outcomes that mattered.

That evidence did more than satisfy the FDA. It made physicians comfortable putting a brand-new category into real patients. And it didn’t stop at company-sponsored publications. As TAVR volumes climbed, the proof broadened into long-term follow-up, independent academic work, and real-world data from hundreds of thousands of cases. At that point, the argument for TAVR—and for Edwards’ leadership within it—didn’t rely on marketing. It relied on gravity.

The broader lesson: clinical evidence isn’t a box to check. It’s an asset you can build, compound, and defend.

Physician Partnerships

Edwards didn’t treat physicians like a distribution channel. It treated them like co-builders.

From the earliest days of valve innovation, the company worked side-by-side with clinicians on design decisions, supported clinical research, and invested heavily in training so hospital teams could perform complex procedures safely and consistently.

That created a powerful kind of stickiness. When physicians learn on a platform, publish on that platform, and build their practice patterns around it, switching isn’t just a purchasing decision. It’s a workflow decision. It’s a confidence decision. Competitors don’t just have to bring a comparable device—they have to overcome experience, trust, and habit.

Just as importantly, those partnerships fed innovation. Close clinical collaboration gave Edwards a tight feedback loop: what’s failing in the field, what’s slowing procedures down, what complications need better solutions, and what the next generation of devices has to prioritize.

Regulatory Expertise

In med-tech, regulatory strategy is product strategy.

Edwards became exceptionally good at navigating FDA pathways, including designing studies that answered two questions at once: what regulators needed to see for approval, and what clinicians needed to see to change practice.

The stepwise expansion of TAVR—from inoperable patients, to high-risk, to intermediate-risk, to low-risk, and eventually to asymptomatic patients—wasn’t automatic. Each step required evidence tailored to a specific risk-benefit profile. Edwards didn’t just wait for the market to broaden; it engineered the clinical programs that allowed the market to broaden.

That capability became a moat. Rivals could build competing valves, but matching Edwards’ labels meant paying the same toll: years of trials, years of follow-up, and enormous expense. While they worked through that process, Edwards kept moving the frontier.

The Economics of Medical Devices

Edwards is also a clean case study in why the best medical device businesses can be so valuable.

The front end is brutal. Development cycles run for years. Clinical trials can cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Regulatory approvals take time. Manufacturing demands extreme precision and unforgiving quality systems.

But if you get through that gauntlet, the economics flip. Heart valves can deliver gross margins north of 70 percent. Physician training and hospital adoption create recurring procedure-driven demand. And the combination of regulatory approvals and deep clinical evidence makes it hard for competitors to dislodge an incumbent.

That’s the med-device bargain: high risk and high investment upfront, followed by durable margins and defensibility if you become the standard.

Patient-Focused Innovation

For Edwards, “patient first” wasn’t just a slogan—it was a practical strategy that shaped the company’s decisions.

TAVR started where the need was most undeniable: patients who were too sick for open-heart surgery and otherwise had no viable option. That focus made the risk-benefit case clear for regulators, and it made adoption emotionally and clinically compelling for physicians. Doctors weren’t choosing between two good options. They were choosing between a new option and no option.

As outcomes improved and the technology matured, the same patient-centered logic pushed the category outward. If a less invasive procedure could deliver comparable results, why put someone through open-heart surgery and a long recovery? That framing helped drive expansion into lower-risk groups, and eventually into patients who hadn’t developed symptoms yet.

It also influenced how Edwards competed. The company consistently positioned itself as advancing care, not just selling devices—and in a field built on trust, that positioning mattered.

X. Analysis & Investment Case

Total Addressable Market Expansion

The core of the Edwards investment story is simple: the market kept getting bigger.

When TAVR first arrived, it was reserved for the sickest patients—people deemed inoperable. That’s a meaningful population, but it’s not a mass market. The real unlock came as Edwards did the hard, expensive work of expanding indications. Each new label didn’t just add a few patients; it widened the funnel.

Today, in practical terms, nearly every patient with severe aortic stenosis can be considered for TAVR. From here, growth comes less from “new” eligibility and more from two levers: higher penetration (getting more eligible patients treated) and continued geographic expansion into countries where TAVR is earlier in its adoption curve.

And Edwards isn’t trying to stop at the aortic valve. The company is chasing transcatheter therapies for mitral and tricuspid disease—two large patient populations where treatment is often complex, inconsistent, or simply unavailable at scale. If Edwards can do what it did in aortic—build a device that works, prove it with convincing evidence, then train the field and push adoption—the total market expands again.

Overlay all of that with the biggest tailwind of all: demographics. Valve disease rises with age, and the world is aging. In developed markets, more people are living into the years where valve disease becomes common. In emerging markets, improving healthcare means more patients survive long enough to develop these age-related conditions. The pool of patients who need intervention keeps growing.

Competitive Moats

Edwards has built defenses that are hard to copy quickly—even for giant competitors.

The deepest moat is clinical evidence. Edwards generated more TAVR data earlier than anyone else, across broader patient populations and with longer follow-up. That work doesn’t just live in internal slide decks; it’s published, peer-reviewed, and baked into guidelines. Competitors can run their own trials, but they can’t go back in time and recreate Edwards’ head start.

Then there’s training and physician relationships. Edwards trained thousands of interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons on its systems. In structural heart, that matters more than outsiders assume. A hospital can’t just “switch vendors” like it’s buying gloves. A new platform introduces procedural learning curves, new workflow, and new uncertainty. That friction is real.

First-mover advantage also compounds in healthcare. Edwards helped shape the regulatory pathway and the reimbursement framework for TAVR. Competitors entered a market where many of the rules—and many of the expectations—were set by Edwards.

Finally, manufacturing quality and supply reliability are quiet but critical. In heart valves, quality problems aren’t a recall-and-move-on event; they can crater trust. Edwards’ consistent track record here is a competitive advantage precisely because it’s so easy to undervalue until it’s gone.

Bear Case

The biggest risk is competition, full stop. Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific are well-funded, highly capable operators. As the category matures and clinical differences between devices narrow, the fight shifts toward contracting and price. That can pressure margins.

Pricing pressure isn’t just competitor-driven, either. Health systems and payers everywhere are under strain, and TAVR is an expensive procedure. In the U.S., Medicare reimbursement matters enormously because it touches most of the patient population. Any reimbursement cuts would flow straight through to Edwards’ economics.

There’s also the simple math of maturation. The 2010s were a once-in-a-generation growth curve because the market was being created from nearly nothing. Keeping those growth rates as the base gets larger is harder. If penetration improvements slow, or if the next indication expansions don’t deliver as hoped, growth could disappoint.

And then there’s the ever-present med-tech risk: regulation. Edwards’ future depends on continued approvals for new products and new indications. Trial failures, approval delays, or post-market safety concerns could slow growth and weaken competitive positioning.

Bull Case

The bull case starts with an unusually durable tailwind: aging. Valve disease is tightly correlated with age. Unless medicine finds a way to prevent or reverse the underlying degeneration, demand rises as populations get older. That’s a long runway.

Geography is the next leg. The U.S. and Western Europe are relatively penetrated, but many large markets are still early. Countries like China, India, and Brazil have growing elderly populations and healthcare systems that are expanding capabilities over time. As these markets mature, the fastest growth can shift outside Edwards’ original strongholds.

Then there’s the pipeline. Transcatheter mitral and tricuspid therapies represent the next major frontier. If Edwards can establish effective therapies, win approvals, and drive adoption, it can open a second and third act beyond aortic stenosis. The mitral opportunity, in particular, could eventually be even larger than aortic.

Finally, profitability could improve. As Edwards focuses more tightly on structural heart—especially after the critical care divestiture—capital and attention concentrate on the highest-value engine. With scale, manufacturing efficiency, and operating leverage, margins could expand further.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low. Getting into transcatheter valves requires enormous upfront investment in R&D and clinical trials, long regulatory timelines, and years of physician training. The bar is so high that meaningful new entrants are rare, and none have successfully broken into TAVR from scratch.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Edwards depends on specialized components and materials, including tissue for bioprosthetic valves. Some inputs can be concentrated. But Edwards’ scale gives it leverage, and diversified sourcing can reduce single-supplier risk.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate and Increasing. Hospitals and purchasing groups have consolidated, and competition gives them more negotiating leverage. That said, physician preference still carries weight, and comfort with a platform can blunt purely price-driven decisions.

Threat of Substitutes: Low. Severe aortic stenosis ultimately needs a valve intervention. Medications can manage symptoms but don’t solve the problem. Surgery is an alternative to TAVR, but it’s not a substitute that makes valve replacement unnecessary.

Competitive Rivalry: High and Increasing. The market is crowded with well-capitalized competitors. Differentiation is harder than it once was, and competition increasingly shows up in contracts, share battles, and pricing.

Seven Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Edwards benefits from scale, but rivals have scaled too. It’s an advantage, but not a knockout punch.

Network Effects: Limited. This isn’t a platform business where value increases automatically with more users.

Counter-Positioning: Historically, this mattered—Edwards pushed TAVR before others fully believed. Today, the category is mainstream and competitors are positioned similarly.

Switching Costs: Real. Switching platforms means retraining teams, changing workflow, and introducing uncertainty into high-stakes procedures. That friction slows rapid share shifts.

Branding: Moderate. Among physicians, Edwards is the best-known name in structural heart, and reputation matters when outcomes and confidence are everything.

Cornered Resource: Clinical evidence is the closest fit. Edwards’ early data advantage can’t be recreated retroactively, even if competitors have narrowed the gap with their own studies.

Process Power: Strong. Edwards has built repeatable capabilities in trial design, regulatory execution, and training. Others can build these too, but it takes time and focus.

Key Performance Indicators

For investors, two metrics tend to tell the story faster than anything else:

TAVR Procedure Volume Growth: This is the heartbeat of the business. Volumes reflect the overall market’s growth and Edwards’ competitive position inside it. If volumes slow sharply or share erodes, that’s a warning signal. If they stay resilient, it reinforces the durability of the franchise.

Gross Margin: Gross margin reveals pricing power and operational execution. Stable or improving margins suggest Edwards is holding its ground while scaling. Compression can be an early indicator of price competition, mix shift, or manufacturing cost pressure.

XI. Epilogue & Future Outlook

The Next Frontier

Structural heart hasn’t slowed down—it’s just moved the goalposts.

The next battleground is earlier intervention: treating patients before symptoms become obvious, and before the heart accumulates damage that can’t be undone. The FDA’s 2024 approval for TAVR in certain people with severe aortic stenosis who haven’t developed symptoms yet was a clear signal of where practice is heading. Once a therapy is safe and repeatable, medicine naturally starts asking the uncomfortable question: why wait?

That shift likely gets supercharged by better imaging and smarter analysis. Researchers are building machine learning tools to read cardiac scans, flag high-risk patients, and help clinicians decide who benefits from intervention, and when. If that works, valve disease could be detected earlier and more consistently—less dependent on whether a patient notices subtle decline, more driven by measurable risk.

Edwards has also positioned itself for a world where care extends beyond the procedure. With acquisitions like Endotronix, it has invested in monitoring capabilities that fit the broader trend in cardiovascular medicine: identify patients sooner, treat them less invasively, and track them more closely afterward.

Meanwhile, the procedure itself keeps getting more precise. Better imaging, improved delivery systems, and potentially AI-assisted guidance could help operators place valves more accurately, reduce complications, and tighten outcomes. And as techniques become more standardized, access could expand—more hospitals building programs, more clinicians able to treat more patients safely.

Emerging Risks

The same forces that create opportunity also create fragility.

One risk is true technology disruption. If medical science ever produces a drug that can prevent, halt, or reverse valve calcification, it would reshape the entire market. Nothing like that is established today—but healthcare has a long history of sudden breakthroughs that change what “inevitable” looks like.

Competition is another permanent pressure. Structural heart is too large, too profitable, and too strategically important for the big device companies to treat it lightly. Expect constant iteration, aggressive commercialization, and new entrants with novel approaches. Edwards’ position has been earned—and it can be defended—but it’s not guaranteed.

And then there’s economics. TAVR is an expensive therapy delivered inside a healthcare system under constant budget scrutiny. If reimbursement meaningfully tightens, it doesn’t just affect Edwards’ growth rate; it changes hospital incentives and slows adoption, especially in markets where funding is already constrained.

What Success Looks Like

If you fast-forward ten years, “success” for Edwards probably looks less like a single heroic product and more like a reinforced platform.

It would still be a TAVR leader, holding or growing share even as competition stays intense—and benefiting from continued penetration as more eligible patients actually get treated. Growth would also come from geography: markets that were once “emerging” becoming real volume engines as training, infrastructure, and reimbursement catch up.

It would also mean Edwards’ second act is real. Mitral and tricuspid therapies would be contributing meaningful revenue, proving the company can do for other valves what it did for the aortic valve: build a therapy, generate the evidence, train the field, and scale it into standard practice.

Financially, success would show up as the combination investors love but few companies sustain: continued growth while protecting profitability—reflecting both scale and the ability to keep innovating.

And clinically, Edwards would still own what has always been its sharpest edge: an evidence base that shapes guidelines, not just satisfies regulators—especially as the field moves toward treating patients earlier.

Lessons for Healthcare Innovation

Edwards Lifesciences offers a set of lessons that are simple to say, but hard to live:

Long time horizons are essential. TAVR took decades to go from concept to clinical default. In med-tech, “overnight success” usually arrives after years of engineering, trials, and physician adoption.

Clinical evidence is competitive advantage. Trials aren’t just the price of admission. Done well, they become a moat—building trust, expanding indications, and raising the cost for competitors to match your label.

Physician partnerships matter. The best device companies don’t just sell to clinicians; they build with them. That collaboration is where better products come from and where adoption is won.

Independence enables focus. The spin-off from Baxter gave Edwards room to place its biggest bets with intensity and patience—two things that get harder inside a diversified conglomerate.

From a retired engineer’s impossible dream in 1958 to a company worth more than $40 billion, Edwards didn’t just make better valves. It helped create an industry, changed what heart care looks like, and expanded the set of patients who get a real shot at treatment. The next decade will test whether it can do it again—earlier, broader, and beyond the aortic valve.

XII. Recent News

In early 2025, Edwards stayed in execution mode. It worked through the integration of its recent deals—Innovalve, JenaValve, and Endotronix—with the goal of turning those acquisitions into real products and real procedure volume over time, especially in mitral and tricuspid disease. Next-generation programs continued to move through clinical trials, with data readouts and updates expected at major cardiology conferences.

The critical care divestiture to BD closed as planned. That deal didn’t just simplify the company’s story; it freed Edwards to concentrate its capital and management attention on structural heart. Leadership reiterated its expectations for continued growth in the structural heart business, alongside further margin improvement.

Meanwhile, the TAVR arena remained a knife fight. Medtronic and Abbott both pointed to gains in specific segments, a reminder that the market Edwards created is now one of the most heavily contested spaces in med-tech. Edwards said it maintained overall leadership, pointing to strong procedure volumes and ongoing physician enthusiasm for its SAPIEN 3 Ultra platform.

Internationally, Edwards kept pushing its expansion agenda, with China as a key focus. The company highlighted steady progress on regulatory and market access efforts, and positioned the country’s demographics and evolving healthcare infrastructure as long-term tailwinds.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings: - Edwards Lifesciences annual reports and 10-K filings - Quarterly earnings releases and investor presentations - Proxy statements and other corporate governance documents

Clinical Evidence: - PARTNER Trial publications in the New England Journal of Medicine - Long-term follow-up studies on TAVR outcomes - Real-world registries and post-market surveillance data

Industry Resources: - American College of Cardiology guidelines on valvular heart disease - Society of Thoracic Surgeons data on surgical and transcatheter valve procedures - FDA approval letters and summaries of safety and effectiveness

Historical Context: - The Artificial Heart: The Story of the Jarvik 7 and related histories of cardiac device innovation - Academic papers on the Starr-Edwards valve and the origins of heart valve surgery - Interviews with Lowell Edwards and Albert Starr from medical history archives

Competitive Analysis: - Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific investor materials on structural heart strategies - Industry analyst reports on the TAVR market - Academic comparisons of transcatheter valve platforms

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music