FICO: The Hidden Operating System of American Credit

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

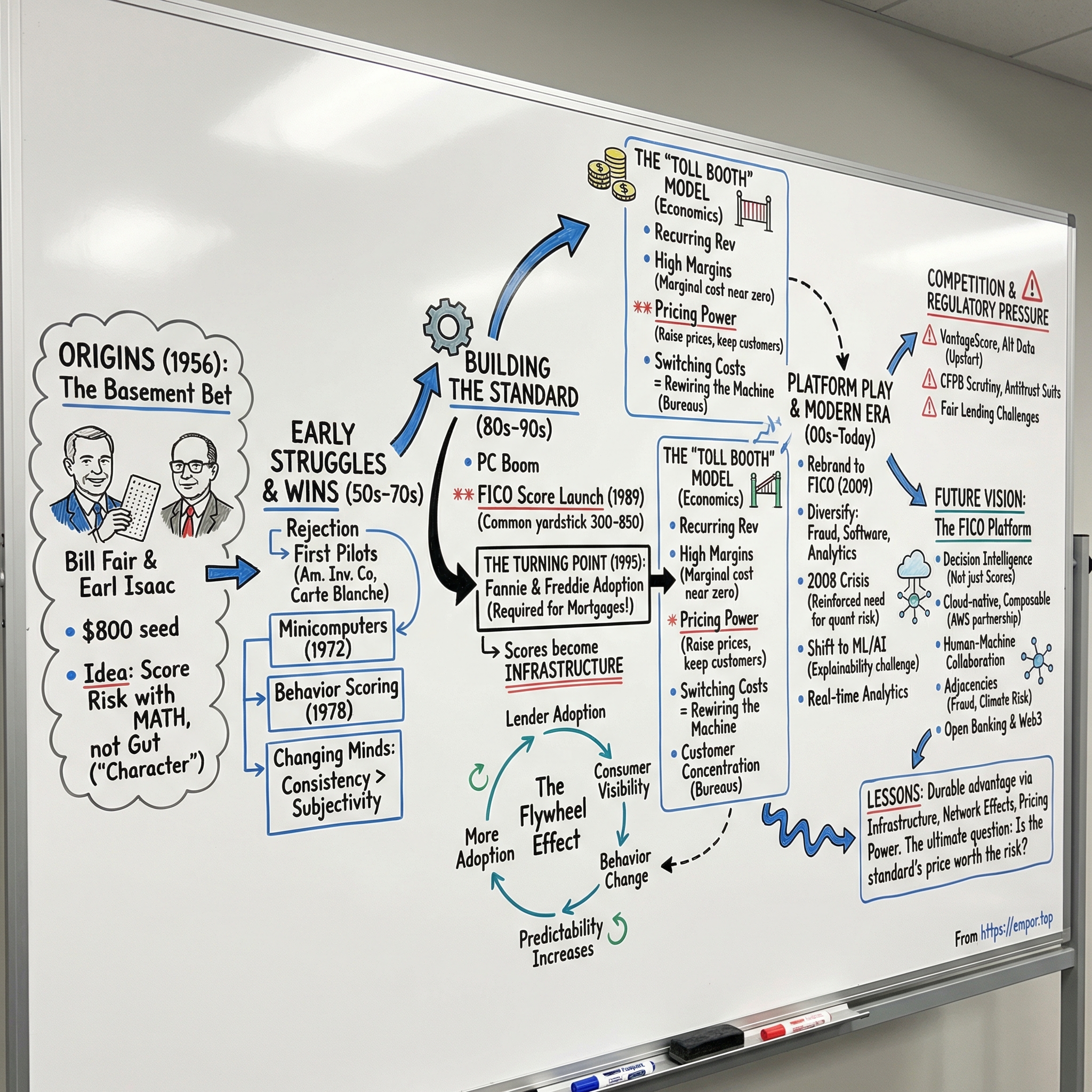

In 1956, in the basement of a modest office building in San Rafael, two men sat surrounded by punch cards and statistical tables, trying to turn a contrarian idea into a business. Bill Fair, a Stanford-trained engineer with a systems mindset, and Earl Isaac, a mathematician who could pull signal from noise, scraped together $800—$400 each—and took a swing at a problem most lenders didn’t even agree was solvable.

Their question was simple, almost naïve: what if credit decisions weren’t made by loan officers trusting their gut, scanning a file for “character,” and—too often—letting bias do the rest? What if you could score risk with math, consistently, at scale?

Nearly seven decades later, that tiny experiment has grown into a roughly $32 billion company that functions like invisible infrastructure for consumer finance. When someone applies for a mortgage, opens a credit card, or finances a car, FICO’s models are usually somewhere in the plumbing. The output—three digits—has become so embedded in American life that people talk about their FICO Score the way they talk about a vital sign, a number that seems to summarize financial health in an instant.

And that’s what makes FICO such a fascinating business. Credit is an enormous market, packed with smart incumbents, hungry startups, and constant regulatory scrutiny—exactly the kind of place you’d expect disruption to thrive. Yet FICO has held on to something that looks a lot like monopoly power for decades. In U.S. mortgages, it’s effectively the standard. So the real question isn’t whether FICO is important. It’s how it became unavoidable.

That’s the arc of this story: from punch cards to cloud software; from subjective, character-based lending to automated decisioning; from a single scoring model to a broader platform that helps companies manage fraud, optimize customer decisions, and run analytics across an entire lifecycle. Along the way we’ll hit the forces that actually built the moat—standardization, network effects in a B2B2C market, and a regulatory environment that, paradoxically, helped lock the whole system in place.

II. Origins: The Mathematical Revolution in Credit (1956–1970s)

Picture America in 1956: Eisenhower in the White House, the interstate highway system just getting underway, and consumer credit still run like a small-town club. If you wanted a loan, you didn’t get “evaluated” so much as judged. A loan officer would flip through your application, maybe call a reference, maybe size you up across the desk, and then make a decision based on what the industry politely called “character.”

In practice, that word covered a lot of sins. The process was slow, inconsistent, and too often discriminatory—shutting out minorities, women, and anyone who didn’t match the loan officer’s mental picture of a “safe” borrower. It also wasn’t great business. When decisions are subjective, you don’t just reject good borrowers. You approve bad ones, too.

Bill Fair had a hard time tolerating that kind of fuzziness. Born in 1922, he trained as an engineer at Stanford, the kind of person who wanted systems to be measurable and repeatable. Earl Isaac brought the complementary superpower: a mathematician’s belief that if you could measure a thing, you could model it—and if you could model it, you could predict it. The two met at Stanford Research Institute, where they worked on operations research projects for corporate clients. They helped companies optimize production and logistics with mathematics.

Eventually the obvious question surfaced: if models could improve factory throughput, why couldn’t they improve lending decisions? Why couldn’t you use data to predict who would pay back a loan?

Their conclusion wasn’t that it was impossible. It was that almost no one had seriously attempted it. The credit industry had grown comfortable with a craft approach. Fair and Isaac saw that complacency as an opening.

So in 1956, in San Rafael, California, they incorporated Fair, Isaac and Company—funded the old-fashioned way, with $400 each. Then they did what founders do when they have an idea the market hasn’t priced in yet: they started dialing.

Their pitch was straightforward. Give us your historical lending data. We’ll build a statistical scoring system that evaluates applications faster and more consistently than a human—and, we think, more accurately.

The early market reaction was brutal. They approached roughly fifty finance companies. Almost all of them ignored the calls or dismissed the premise entirely. To many executives, the idea that a formula could replace a seasoned loan officer wasn’t just wrong—it was insulting.

But one firm said yes. American Investment Company, a small consumer finance outfit, agreed to run a test. The pilot worked. Default performance improved enough to give Fair and Isaac the only thing that really matters in an early market: proof.

From there, the wins started to compound. In 1957, Conrad Hilton’s Carte Blanche credit card operation became a client—an early vote of confidence in the emerging world of general-purpose credit cards. In 1963, Montgomery Ward signed on and used Fair and Isaac’s Credit Application Scoring Algorithms to evaluate store credit for its massive catalog business. This wasn’t an academic exercise anymore. This was math making real decisions at scale.

What made the models useful was also what made them controversial: they didn’t care about vibes. Fair and Isaac leaned into a counterintuitive truth that feels obvious now but wasn’t then—past behavior predicts future behavior better than anyone’s impression of “character.” If you looked back at thousands of borrowers who repaid and thousands who didn’t, patterns emerged. Variables like income stability, existing debt burden, and payment history could be measured and weighted. The score wasn’t magic. It was statistics, applied with discipline.

Then the technology caught up, and the whole thing got more powerful. In 1972, Fair Isaac adapted its products for minicomputers, making it possible to process applications automatically. Instead of a file moving across desks, a lender could input the data and get a score back quickly—turning credit decisions from a slow, human workflow into something that started to resemble a system.

In 1978, Fair Isaac took another step: behavior scoring. Rather than only scoring someone at the moment they applied, lenders could score existing customers based on how they were actually paying over time, and predict who was drifting toward delinquency. Risk wasn’t a one-time judgment anymore. It was something you could monitor continuously across a customer relationship.

By the end of the 1970s, Fair Isaac had done something rare: it had changed minds. It had shown that mathematics could make lending decisions more consistent—and, importantly, less dependent on who you were or how you looked to the person across the desk. That wasn’t just a moral improvement. It was a commercial one, too, because it helped lenders extend credit profitably to people they might have ignored under the old regime.

The world around them was shifting as well. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 prohibited discrimination in lending, and that made objective, defensible scoring systems more attractive to institutions increasingly wary of fair-lending challenges.

And yet, for all the conceptual progress, Fair Isaac was still, at its core, a modest consulting business—building custom models client by client, bringing in only a few million dollars a year. They had proven the idea. They just hadn’t found the lever that would turn a good product into a default standard.

That lever would be standardization. And in American credit, the biggest machine that runs on standards is the housing market.

III. Building the Standard: From Software to Score (1980s–1990s)

The 1980s personal computer boom hit Fair Isaac like a wave. Cheaper computing meant more companies could run statistics, which threatened to turn analytical know-how into a commodity. But it also meant something else: models could be built, shipped, and updated faster than ever. Fair Isaac’s response was the move that changed everything. It stopped being primarily a bespoke consulting shop and started turning its expertise into products—standardized tools that could scale.

In 1989, it launched the thing that would define the company: the general-purpose FICO Score. Instead of building a custom scorecard for each lender, Fair Isaac offered one common yardstick the whole industry could use. A single number, on a simple range—300 to 850—where higher meant lower risk. That simplicity wasn’t dumbing it down; it was the point. If credit was going to become automated and interoperable, lenders needed a shared language. FICO gave them one.

The business impact showed up fast. Revenue rose from $31.8 million in 1991 to $114 million by 1995. But the real inflection point wasn’t a revenue line—it was a rule change.

In 1995, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began using FICO scores in mortgage underwriting. That decision is hard to overstate. Fannie and Freddie weren’t just big customers; they were the pipes that moved mortgages through the American financial system. If a bank wanted to sell loans into the secondary market—which, in practice, meant most banks making conforming mortgages—it now needed a FICO score attached to the file.

In other words: the score didn’t just become helpful. It became required. Almost overnight, FICO went from being a vendor to being a standard.

Once that happened, the flywheel started turning. As lenders adopted the score, it became more visible to consumers. As consumers learned the score existed, they started changing their behavior around it—pay on time, keep balances down, manage credit carefully. That made outcomes more predictable, which made the score more useful, which encouraged more adoption. The value of the system increased with every new participant, and the moat deepened quietly in the background.

There was also a psychological shift. Before the 1990s, most people had no clear idea what a lender saw when they evaluated an application. The FICO Score turned an opaque process into something that felt legible: a number you could track, a target you could improve. FICO didn’t have to convince consumers to love being measured. It framed the score as a tool—almost a personal dashboard—and people responded because the rules suddenly seemed knowable.

Plenty of others noticed the opportunity. Credit bureaus, in particular, had a reasonable thought: we already control the data, so why shouldn’t we own the scoring model too? They tried. And they mostly failed, for reasons that reveal why FICO’s position became so durable. Lenders didn’t want to bet their portfolios on an unproven alternative when FICO had a track record. The system—especially the mortgage system, with Fannie and Freddie’s influence—was nudging everyone toward the same standard. And switching wasn’t just flipping a software setting. It meant rebuilding risk models, retraining teams, changing processes, and then defending that change to regulators and internal risk committees.

By the end of the 1990s, FICO had pulled off something every enterprise software company dreams about: it stopped being a product and started being infrastructure. The score was embedded so deeply in American lending that replacing it would mean rewiring the machine around it. That’s not just competitive advantage. That’s what it looks like when a company becomes part of the operating system.

IV. The Platform Play: Beyond Scores (2000s–2010s)

The new millennium brought Fair Isaac a strange mix of validation and anxiety. They had won credit scoring. But they also knew the trap: when one product becomes your identity, it also becomes your single point of failure. What happens if regulators push the market toward alternatives? What if the credit bureaus finally land a real competitor? What if new technology makes a three-digit score feel like a relic?

So FICO went on offense—by getting bigger than the score.

In 2003, the company renamed itself Fair Isaac Corporation, a subtle way of telling the market it was more than a scoring vendor. Then in 2009 it did something even more revealing: it rebranded to just FICO. The acronym had become the brand, the shorthand, the thing people recognized. And more importantly, it marked a shift in how the company wanted to be perceived—not as a model-builder, but as a platform.

That platform strategy came in two moves. First, FICO pushed outward into adjacent analytics problems that looked a lot like credit risk, just wearing different clothes: fraud detection, customer acquisition, collections, and pricing. Same core capability—finding patterns in messy data—applied across more of the financial stack. Second, it pushed downward into software: tools that didn’t just generate insights, but actually embedded them into day-to-day operations, so decisions could be automated, tracked, and improved over time.

Over time, that diversification showed up in how the company described itself. By the mid-2020s, FICO’s business grouped into three segments: Scores, Software, and Services. The score still mattered enormously—but it was no longer the whole story.

Then came the ultimate real-world test: the 2008 financial crisis. In the wreckage, critics went looking for culprits, and FICO wasn’t immune. The accusation sounded intuitive: if millions of borrowers defaulted, didn’t the scoring system fail?

The postmortem was less clean—and more telling. FICO scores did distinguish between borrowers more likely to repay and those more likely to default. The problem was that many lenders chose to lend further down the risk curve anyway, essentially deciding that higher default rates were acceptable if higher interest rates came with them. The score didn’t force anyone to take risk. It quantified it. And like any instrument, it could be used responsibly or abused.

In a twist, the crisis ended up reinforcing FICO’s position. Underwriting standards tightened. Regulators demanded more rigor. Banks, burned by losses, became more dependent on quantitative risk measurement. In an environment that prized validation and defensibility, a standardized score with a long track record didn’t look like a nice-to-have—it looked like a safety rail.

At the same time, the moat kept thickening. FICO amassed more than 200 patents tied to scoring methods, adding legal friction to would-be imitators. It locked in long-term relationships with the three major credit bureaus—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—ensuring ongoing access to the data that made its models valuable. And as customers integrated FICO deeper into their workflows, switching stopped being a procurement decision and became an organizational upheaval.

But dominance has a cost: attention. Between 2020 and 2023, at least ten antitrust class action lawsuits were filed against FICO. Plaintiffs alleged that FICO maintained monopoly power through anticompetitive agreements with the credit bureaus—contracts designed, they claimed, to keep alternative scores from ever gaining real distribution. FICO denied wrongdoing, but the message was clear: when a company becomes infrastructure, even ordinary business arrangements start to look suspicious through a regulatory lens.

V. The Business Model & Economics

If you want to understand why FICO has been such a durable winner, you have to look at the economics. This is a business with recurring revenue, minimal capital needs, and the kind of pricing power that shows up only when you’ve become a de facto standard. It’s the “toll booth” model: the traffic keeps coming, and you get to set the toll.

Start with the core Scores business, the engine that still produces roughly half of FICO’s revenue. When a lender pulls a consumer’s credit report, it typically buys a FICO Score right alongside it. FICO earns a royalty each time that happens, with the price depending on the use case. Mortgage scores can cost several dollars; a credit-card decision score costs less. On any single transaction, it doesn’t sound like much. Across billions of pulls, it becomes a machine.

What makes that machine so powerful is the marginal cost. Scores are delivered electronically through the credit bureaus’ existing pipes. Once the model is built and distributed, selling one more score costs FICO essentially nothing. So as revenue rises, a huge share of each incremental dollar drops straight to profit. That’s why FICO’s gross margins have consistently run above 80%—software-company territory, but with even more “toll booth” characteristics than most SaaS businesses.

Then there’s Software, which works differently but fits the same underlying pattern. Here, FICO sells analytics and decision-management tools—think platforms that help banks and insurers make and automate decisions, plus systems for things like fraud detection. These products are typically sold as subscriptions, which means recurring revenue that builds over time. FICO has reported Software Annual Recurring Revenue growing year-over-year, with the core FICO Platform growing much faster, and a Dollar-Based Net Retention Rate of 106%—a simple signal that existing customers, on average, keep spending more each year.

But the most revealing part of the story is pricing power. For the past decade, FICO has been able to raise prices on scores—sometimes by 10% or more annually—and not watch customers walk away. In most markets, that kind of increase would trigger switching. In FICO’s world, switching isn’t a procurement decision. It’s a rewrite of underwriting policies, risk models, compliance documentation, and operational workflows—inside institutions that are built to avoid change.

And in mortgages, the constraint is even harder: FICO scores are required in underwriting by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. That one fact turns “preferred vendor” into “default infrastructure.” It’s the reason FICO can push price and, while customers may complain, they still pay—because the alternative is worse.

You could see this dynamic in stark form recently, when the Scores segment posted 38% growth in a period driven mostly by higher unit prices, not more volume. That’s the clearest test of a moat: can you charge more for the same thing and keep the business? In FICO’s case, the answer has been yes. The closest analogy is when Visa or Mastercard change economics: merchants grumble, but they keep taking the cards because opting out isn’t realistic.

There is one real wrinkle in the model: customer concentration. The three credit bureaus—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—are the main distributors of FICO scores, and they represent a meaningful share of revenue. If one bureau truly replaced FICO and stopped carrying the score, it would matter. But the practical barriers are high. The bureaus have tried to compete before and haven’t displaced FICO, and they also make attractive margins distributing FICO scores to their own customers.

All of this sets up the bet FICO is making next: the platform strategy. The FICO Platform, launched in recent years, is designed to become an enterprise intelligence network for decisioning across the full customer lifecycle—from acquisition to account management to collections. The ambition isn’t just “sell more products.” It’s to become the layer where decisions happen. The more of a customer’s workflows run through FICO, the more embedded FICO becomes, and the harder it is to unwind.

If you’re tracking the health of the franchise, the scoreboard is pretty simple. Watch pricing in Scores, because that’s the purest read on moat strength. Watch Platform ARR growth, because that tells you whether diversification is working. And watch net retention, because that tells you whether customers are expanding their relationship or quietly pulling back.

VI. Modern Era: AI, Competition, and Regulatory Challenges (2010s–Today)

Walk into FICO’s San Jose headquarters today and you’re not seeing the punch-card world Bill Fair and Earl Isaac started in the 1950s. You’re seeing a modern software-and-models company: more than 2,000 employees, over 10,000 clients across 100 countries, and more than $1 billion in annual revenue. The whiteboards aren’t covered in hand-tuned scorecards anymore. They’re filled with machine learning diagrams, deployment pipelines, and debates about model governance.

Under the hood, the biggest shift has been the move from rules and classic statistical scoring into machine learning. For decades, credit scoring leaned heavily on logistic regression: a workhorse technique that’s stable, relatively simple to validate, and—crucially—easy to explain. It’s also constrained. It struggles to capture messy, non-linear relationships in real consumer behavior. Machine learning can, in theory, find signal that traditional methods miss and squeeze more predictive power out of the same inputs.

But lending isn’t a sandbox. It’s a regulated environment where “because the model said so” isn’t an acceptable answer. When a lender denies you credit, it has to provide a reason—what the industry calls adverse action reasoning. That requirement collides with black-box models that can be accurate but opaque. FICO has tried to thread the needle by developing interpretable machine learning: techniques designed to deliver more sophisticated predictions without sacrificing transparency. The company has patented work in this area, reinforcing the same pattern we’ve seen throughout its history—turn the hard part into IP, and make the moat a little steeper.

Another major frontier is speed. Traditional scoring is, by design, a snapshot—built on bureau data that can lag reality. But modern risk doesn’t always wait for the next reporting cycle. Real-time analytics aims to incorporate fresher signals, like recent transactions, current balances, or fraud indicators, and update risk assessments continuously. FICO has invested to support this kind of decisioning infrastructure—systems designed to handle enormous volumes with very low latency—because in many financial products, milliseconds now matter.

Meanwhile, the competitive landscape has gotten louder. VantageScore, created by the three major credit bureaus in 2006, is the most credible direct alternative to the FICO Score. It uses the same familiar 300–850 scale and argues it can score more consumers who don’t fit neatly into traditional models—often described as the “credit invisible.” VantageScore has found adoption in areas like credit-card marketing and tenant screening, but it still hasn’t broken into the mortgage pipe, where Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac continue to require FICO.

The more destabilizing threat may come from outside the traditional bureau system entirely: alternative data and new underwriting models. Companies such as Upstart and Petal have pushed approaches that lean on bank transaction data, employment information, and other non-bureau signals, with a straightforward pitch to lenders: you’re turning away good borrowers because your inputs are too limited. If these methods continue to gain traction and, importantly, regulatory comfort, they could chip away at FICO’s grip—especially with younger consumers who have thin files and different financial footprints.

All of that pressure is happening while scrutiny ramps up. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has examined FICO’s market power and the downstream impact of pricing on consumers, who ultimately absorb higher assessment costs through the system. The antitrust class action lawsuits filed between 2020 and 2023 remain unresolved, keeping a cloud of legal uncertainty overhead. And fair-lending advocates continue to press a deeper critique: even if scoring is consistent and “objective,” it can still reflect the inequities embedded in historical data—because variables correlated with income and race can shape outcomes without explicitly using prohibited attributes.

Internationally, there’s growth—but also friction. FICO has expanded across Europe, Asia, and Latin America, yet credit markets outside the U.S. don’t share the same centralized bureau infrastructure. Data can be thinner, norms differ, and regulations swing from GDPR-level privacy constraints to far looser regimes in developing markets. FICO has responded with localized products and partnerships with regional data providers, but international revenue remains a relatively small slice of the whole.

So the modern question is not whether FICO is still powerful—it is. The question is whether the moat is getting deeper or starting to look more contestable. Pricing power suggests the core franchise is intact. But the list of forces pressing in—AI disruption, alternative data, and regulators taking a harder look—keeps growing. And the next chapter depends on whether FICO can extend “the score” into a broader decisioning platform without losing the thing that made it indispensable in the first place.

VII. The FICO Platform & Future Vision

The future bet FICO is making can be summed up in two words: decision intelligence. Instead of staying the company behind a three-digit credit score, FICO wants to be the system that sits underneath every high-stakes choice an institution makes—who gets approved, which transaction gets flagged, what offer gets shown, how collections gets prioritized.

The FICO Platform, introduced in recent years, is the vehicle for that ambition. It’s built as an open-architecture platform with composable building blocks spanning what FICO calls the “applied intelligence value chain.” In plain terms, it’s a cloud-based environment where customers can build, deploy, and govern decision models across the business. A bank might run loan origination, fraud screening, marketing optimization, and collections strategies in one integrated setup—less a point tool, more a decisioning layer that can be reused everywhere.

A key design idea is human-machine collaboration. The platform is meant to automate the routine calls, then escalate the hard ones. FICO describes this as “automatic intervention”: models make the fast, repetitive decisions, while ambiguous or high-impact cases get routed to people. It’s a pragmatic stance in a regulated world—drive efficiency without pretending you can remove accountability.

Beyond credit, FICO has also leaned hard into fraud. The company says its Falcon Fraud Manager protects 2.6 billion payment cards worldwide, analyzing billions of transactions each year to spot suspicious patterns. It’s a natural adjacency: fraud is the same kind of problem FICO has always been good at—pattern recognition, huge scale, constant tuning—and it comes with the same sticky dynamic. Once a fraud system is wired into real-time operations, swapping it out is painful.

You can see the platform strategy most clearly in the partnerships FICO has chosen. One is with Tata Consultancy Services, focused on climate risk assessment models—an attempt to extend FICO’s modeling DNA into ESG-driven risk analytics. With more than $23 trillion in assets managed under ESG mandates, the prize is real. The open question is fit: credit risk has decades of standardized data behind it; climate risk is messier, newer, and harder to measure with confidence.

Then there’s the AWS partnership, which may matter even more. By embedding FICO’s tools into Amazon’s cloud ecosystem, FICO effectively turns itself into a service that can be provisioned rather than procured. That’s a big deal for mid-sized lenders and fintechs: instead of a long enterprise sales cycle, they can access FICO capabilities through the infrastructure they already run on. For FICO, it’s not just cloud hosting—it’s distribution.

All of this is happening while the definition of “credit data” is expanding. Open banking—especially in Europe and the UK—makes it easier for consumers to share bank-account and transaction data with third parties, opening the door to new scoring approaches that don’t rely solely on the traditional bureau file. In the background, Web3 advocates keep pitching decentralized reputation systems built on on-chain history. And real-time payments push the whole market toward instant assessment, where risk is measured using current signals, not just historical ones.

FICO’s public posture has been to lean in: open-banking integrations, alternative-data pilots, real-time scoring capabilities. Whether that becomes a true second act—or a set of defensive experiments meant to protect the core—will determine how the next decade reads. Platform transitions are notoriously hard. The companies that look inevitable in one era often discover that inevitability doesn’t automatically transfer to the next.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

FICO’s seven-decade run isn’t just a story about credit. It’s a case study in how durable advantage gets built—and why it’s so hard to unseat once it’s in place.

First: the peculiar power of becoming infrastructure. Once your product is embedded deep enough in an industry’s daily operations, “better” stops mattering as much as “standard.” FICO earned that status most visibly when Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac required its scores in mortgage underwriting. After that, ripping FICO out didn’t look like swapping a vendor. It looked like rewiring an entire system. And the key insight here is coordination: replacing infrastructure usually requires multiple parties to move at once, and most of them have no incentive to be the first mover.

Second: network effects can show up in places that don’t look like networks. FICO isn’t Facebook; users don’t “join” because their friends did. The loop is more subtle. As more lenders adopted FICO, the score became a de facto standard. As it became a standard, regulators and institutions built processes around it. As it got woven into the system, even more lenders adopted it because that’s what the ecosystem expected. And as the footprint expanded, the models improved, reinforcing the score’s usefulness. It’s a flywheel across lenders, regulators, and consumers—not a single two-sided marketplace, but a reinforcing system that’s proven stubbornly durable.

Third: the B2B2C dynamic is more powerful than it looks. FICO sells to lenders, but its product lives in the minds of consumers. People track their FICO score, worry about it, and make decisions around it—despite having no direct relationship with FICO itself. That consumer awareness becomes its own kind of moat. Even if a lender wanted to switch to a competitor, it would have to explain to customers why the number they’ve been trained to care about suddenly matters less. In credit, trust and familiarity aren’t marketing nice-to-haves; they’re friction in the switching process.

Fourth: pricing power is the clearest signal that the moat is real. Lots of companies can grow by discounting. Far fewer can raise prices year after year and keep customers anyway. FICO has done exactly that—pushing through aggressive price increases with minimal attrition—because the alternatives are costly, uncertain, and in some parts of the market, not really alternatives at all.

Fifth: the regulatory moat paradox. Regulation is usually framed as a tax on business. But for incumbents, it can harden the playing field into concrete. FICO’s privileged position in mortgage lending was effectively cemented by the rules of the system. Changing it doesn’t just require a competitor with a better product; it requires regulators and institutions to accept a new standard. That creates an asymmetry: challengers have to win a public, procedural battle, while FICO benefits from inertia.

Sixth: switching costs don’t just exist—they compound. Over time, lenders bake FICO into underwriting policies, model validation processes, compliance documentation, operational workflows, training, and vendor relationships. Each year adds more dependencies. A lender that’s used FICO for decades isn’t just paying for scores; it’s carrying a mountain of accumulated “this is how we do it” that would be expensive and risky to unwind. The longer the relationship lasts, the harder it gets to leave.

And finally: boring can be beautiful. Credit scoring isn’t glamorous. It doesn’t dominate consumer headlines or inspire cult-like fandom. But the underlying economics—recurring revenue, high margins, minimal capital needs, and proven pricing power—are exactly the ingredients that tend to compound into long-term shareholder value. Sometimes the best businesses are the ones that feel too unsexy to start a stampede.

IX. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

FICO trades at a valuation that assumes a lot will keep going right. The stock sits at roughly 51x earnings versus an estimated “fair” multiple closer to 39x, and intrinsic value work implies the market price may be 30% or more above fair value. That sets up the whole investment debate in one line: is FICO’s moat so deep that it deserves premium pricing, or is the market paying up for yesterday’s certainty while tomorrow’s threats get louder?

The bull case starts with a simple observation: FICO is still the standard. It controls about 90% of the credit scoring market and has close to a complete grip on mortgages. That kind of share doesn’t happen by accident, and it hasn’t been easy for competitors to budge. The argument is that FICO’s advantages are structural, not cyclical.

Then comes the second engine: the platform. If FICO can successfully expand from “the score” into an enterprise decisioning system, it becomes bigger than credit risk and more embedded in day-to-day operations. In that world, the company isn’t just collecting tolls on score pulls; it’s sitting inside underwriting, fraud, marketing, and collections workflows across a bank. That both expands the opportunity and raises switching costs even further.

AI is the other pillar of the bull thesis. Credit decisioning is moving toward machine learning, real-time analytics, and explainable models that can survive regulatory scrutiny. Those are precisely the areas where FICO has been investing, backed by a large patent portfolio and deep research capability. And unlike a pure software entrant, FICO already has relationships with essentially every major lender—distribution that’s hard to recreate from scratch.

The bear case is basically the inverse: what if the infrastructure gets regulated, or the standard breaks?

The antitrust lawsuits—still unresolved—put a spotlight on how FICO maintains power, particularly through its arrangements with the credit bureaus. An adverse outcome could force changes to business practices and pricing mechanics that have been central to the “toll booth” model. Layer on top the CFPB’s scrutiny, and you have a realistic pathway to tighter oversight, whether that looks like constraints on pricing, changes in required disclosures, or pressure to open the system to competing scores.

Competition is the other pressure point. VantageScore and alternative-data approaches haven’t meaningfully displaced FICO in the places that matter most, but they’re credible enough to be a risk. The biggest single “what if” is mortgages: if Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were to accept VantageScore for underwriting—a shift that’s been discussed but not implemented—FICO’s near-monopoly in that channel would weaken dramatically. At the same time, open banking and real-time data could push the market toward new credit assessment methods that don’t map neatly onto a traditional bureau-based score at all.

Zoom out and the strategy frameworks mostly confirm what your instincts already tell you. Under Porter’s Five Forces, entry barriers are extremely high: regulation, entrenched relationships, and technical complexity all stack the deck. Supplier power is moderate because FICO relies on the bureaus for distribution, but the relationship is mutually beneficial. Buyer power is low; lenders can complain, but alternatives are limited and switching is painful. Substitutes are the growing threat, and rivalry remains muted because FICO is so dominant. That mix supports durable profitability—but it doesn’t automatically justify paying any price.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers gets at the same thing in a different way. FICO clearly has Network Effects, Switching Costs, a Cornered Resource in the form of mortgage-system requirements, and Branding via consumer awareness of the FICO Score. The other Powers are murkier: FICO is the incumbent, so “counter-positioning” doesn’t really apply; competitors can replicate analytics with enough talent and time; and while scale helps, it’s not the decisive weapon by itself. Four meaningful Powers still adds up to a formidable franchise—just not an invincible one.

If you want a practical scoreboard going forward, there are three signals that matter most. First, Scores pricing: if FICO keeps raising prices without meaningful pushback, the moat is intact. Second, Platform ARR growth: that’s the clearest read on whether the second act is working. Third, regulation—especially anything that changes Fannie and Freddie’s scoring requirements. Watch those, and you’ll have the best real-time view of whether FICO’s franchise is strengthening, holding steady, or starting to crack.

X. Epilogue & Final Reflections

Pull back from the spreadsheets and the market structure for a second and look at what FICO built in human terms. A three-digit number—born from two engineers, a small office basement, and an unfashionable belief in math—now helps shape the economic lives of hundreds of millions of people. It influences who gets a mortgage, who gets a credit card, who can finance a car, and who gets shut out when life gets expensive. For better or worse, the FICO Score has become one of the most consequential numbers in American life.

That’s why the financial inclusion debate around FICO has always been complicated. Supporters argue that scoring helped democratize lending by replacing opaque, inconsistent loan-officer judgment with a system that was at least measurable and repeatable. Someone without the “right” connections but with a solid payment history could finally be evaluated on something concrete. Critics counter that the score can echo the inequities baked into history: if entire communities were denied fair access to credit for generations, then “past behavior” isn’t just personal behavior—it’s a record shaped by unequal opportunity. Both of those things can be true at the same time.

A useful thought experiment is the simplest one: what happens if FICO disappears tomorrow?

Mortgage lending would seize up, because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac require FICO scores for underwriting. Credit card issuers would lose the industry’s most common tool for instant approvals. Auto lenders, personal loan providers, and even landlords would scramble to replace a shared yardstick with something else. The disruption wouldn’t be measured in days or weeks. It would take years—because the hard part wouldn’t be building a new score, it would be getting the entire ecosystem to agree on it, validate it, integrate it, and trust it.

That’s also the founder lesson hiding in plain sight. FICO didn’t just build a good product. It became the standard. Fair and Isaac didn’t win because they were the only people who could model risk. They won because their score became the metric the system coordinated around. In markets with network effects and regulation, “better” doesn’t automatically win. “Default” does.

Looking forward, the next era of credit decisioning won’t be set by FICO alone. AI is improving fast, unlocking new ways to assess risk that may rely less on traditional bureau files. Open banking is pushing more control of financial data toward consumers, which could make it easier for new scoring approaches to compete on fresh inputs. And younger generations—raised on real-time everything—may be less willing to accept that a score built on lagging data should define their financial options.

FICO’s challenge, then, is the challenge of every company that becomes infrastructure: staying essential as the surrounding system evolves. The business Bill Fair and Earl Isaac founded in 1956 survived the shift from punch cards to minicomputers to PCs to cloud software. Whether it navigates the transition to AI, open data, and real-time decisioning will decide what the next seven decades look like.

What began with $800 and a long string of rejection letters became one of the most profitable and durable franchises in American business. The FICO Score isn’t just a product. It’s part of the machinery. And when something becomes that embedded, the ultimate question—especially for investors—stops being “Is this a great business?” and becomes “Is the price worth the risks that come with being the standard?” That’s the bet each investor has to make for themselves.

XI. Recent News

The back half of 2025 delivered a familiar message for anyone watching FICO closely: the core machine kept working. In its fiscal 2025 results, the company showed continued strength in Scores, with growth driven more by price than by an explosion in credit volume. Management also held to guidance for high-single-digit revenue growth in fiscal 2026—an implicit statement that it believes it can keep pushing pricing, even with regulators circling.

That regulatory attention didn’t go away. The CFPB issued new guidance on credit scoring practices that leaned hard on transparency in algorithm-driven lending decisions. It didn’t force changes to FICO’s model or its commercial setup, but it did underline the direction of travel: more scrutiny, not less. Meanwhile, the antitrust class actions continued to grind through the courts, scattered across different stages of litigation, with no resolution expected before late 2026.

On the product front, FICO kept investing in the “platform, not just the score” story. The FICO Platform gained expanded capabilities, including additional integrations aimed at fraud detection and customer lifecycle management. The company also announced multiple enterprise deals with large financial institutions, though it didn’t disclose specific terms.

And distribution—always the quiet power behind FICO—kept expanding. The AWS partnership deepened, with FICO’s tools rolling out to additional AWS regions, making it easier for more customers to deploy without heavy infrastructure lift.

Competition remained active, but the center of gravity didn’t move. VantageScore continued pressing for acceptance in the mortgage market, but Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac still had not approved it for conforming loans. Alternative data providers kept gaining share with fintechs and non-bank lenders, but they remained on the margins of traditional banking—at least for now.

XII. Links & References

Primary Sources and SEC Filings: - FICO annual reports and 10-K filings (SEC EDGAR) - FICO quarterly earnings releases and 10-Q filings - FICO investor presentations and earnings call transcripts - FICO proxy statements (DEF 14A)

Industry Reports and Analyses: - Consumer Financial Protection Bureau reports on credit scoring - Federal Reserve research on credit access and credit scoring - Moody’s and S&P industry analysis on credit bureaus and credit infrastructure - Trade coverage: American Banker, Risk Magazine

Academic and Research Papers: - Fair Isaac Corporation historical archives - Stanford Business School case studies on credit scoring - Research on the impact of credit scores and predictive validity

Regulatory Documents: - Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac selling guides (scoring requirements) - Equal Credit Opportunity Act and Regulation B - Fair Credit Reporting Act and related guidance - CFPB guidance on adverse action notices

Legal Filings: - Antitrust class action complaints (2020–2023) - Court filings and documents related to credit bureau litigation

Company Resources: - FICO official website and investor relations materials - FICO patent filings (USPTO database) - FICO research publications and technical papers

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music