Fidelity National Information Services (FIS): The Fintech Infrastructure Giant That Powers Global Commerce

I. Introduction & Episode Setup

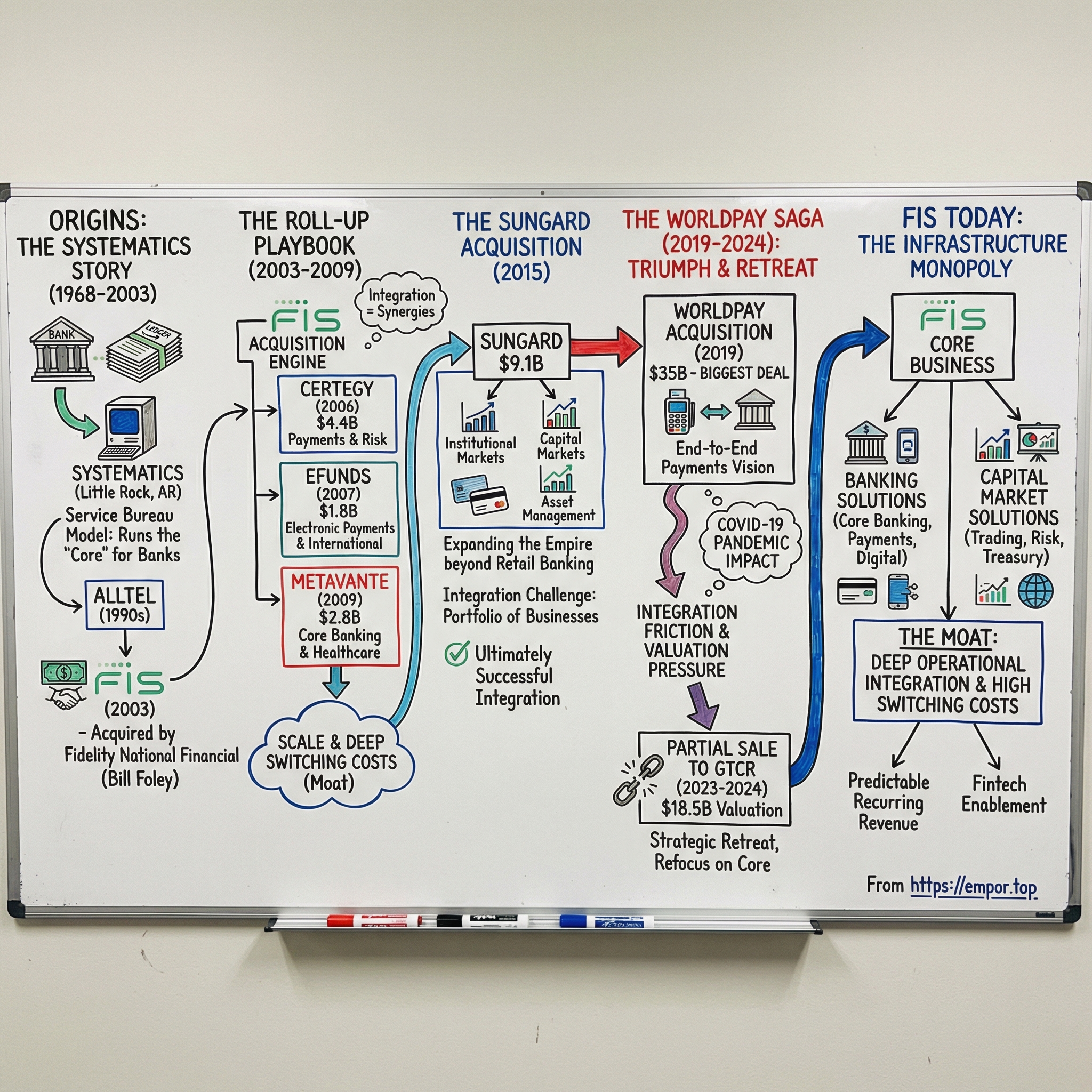

Picture this: you tap your card for a coffee in Seattle, pull cash from an ATM in Singapore, or move money in a banking app in São Paulo. In all three cases, there’s a very good chance the transaction is touching technology run by a company you’ve probably never heard of.

Fidelity National Information Services—FIS—helps move roughly $9 trillion a year and processes about 75 billion transactions globally. For scale, that’s more transaction volume than the entire GDP of Japan.

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the heart of this story: how did a small data-processing startup in Little Rock, Arkansas—one that started out helping regional banks escape the world of paper ledgers—turn into the invisible backbone of modern financial infrastructure?

The answer is part ambition, part timing, and a whole lot of dealmaking: one of the most aggressive acquisition machines fintech has ever seen, capped by a $35 billion wager on payments that would later need to be partially unwound. Along the way, FIS built switching costs so deep that even the slickest fintech upstarts struggle to pry customers away once the plumbing is installed.

This is a story about infrastructure monopolies: the unglamorous businesses that don’t trend on social media but make the economy work. It’s about the roll-up playbook executed at industrial scale, the seductive logic of mega-mergers, and the moment that logic breaks—when integration complexity starts to outweigh the strategy.

And it’s also a cautionary tale. The same acquisition-driven engine that helped push FIS into the Fortune 500 and created enormous shareholder value also set the stage for one of the most dramatic strategic retreats in recent fintech history: selling off a majority stake in Worldpay just a few years after buying it for $35 billion. To understand FIS, you have to understand how both outcomes came from the same playbook.

II. Origins: The Systematics Story (1968-2003)

In 1968, Little Rock, Arkansas was an unlikely place to kick off a financial technology revolution. The city was still living in the shadow of the Central High School desegregation crisis from a decade earlier. The economy ran on agriculture, retail, and state government. The notion that a company founded there would one day sit under a meaningful slice of global commerce would have sounded ridiculous.

And yet, that’s where Systematics began: a scrappy startup built around a simple observation. Banks—especially the small and mid-sized institutions that served rural America—were drowning in paper. Checks were processed by hand. Ledgers were balanced manually. Errors were common, labor was expensive, and growth just meant hiring more people to push more paper.

Walter Smiley, a former IBM systems engineer, saw the opening. Mainframes could do this work better, faster, and more reliably. The catch was that most banks couldn’t afford the hardware, the specialized staff, or the data centers required to run those systems themselves.

Convincing bankers of that was its own battle. Systematics wasn’t selling to early adopters. It was selling to conservative operators who had built their careers on paper trails, personal relationships, and routines that had worked for decades. Smiley and his team drove across the rural South and Midwest, pitching one community bank at a time. They weren’t just offering a product. They were asking banks to hand over the most sensitive, most mission-critical part of their business: the books.

The breakthrough was the service bureau model. Instead of shipping software and leaving the bank to figure out operations, Systematics ran the systems for clients. Banks sent their transaction data to Systematics’ data center. Systematics did the processing, handled maintenance, and pushed updates. In modern terms, it looked a lot like cloud computing—delivered on mainframes and phone lines, decades before anyone called it “the cloud.”

That model did two things at once. It lowered the barrier to adoption, because a small bank didn’t need to build an IT empire to modernize. And it created deep dependence. Once a bank had integrated its workflows, reporting, and staff training around Systematics, switching away wasn’t a vendor change—it was an operational heart transplant.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Systematics quietly became a force in core banking software. Core banking is exactly what it sounds like: the foundational systems that run deposits, withdrawals, loans, and account management. It’s the operating system of a bank. And just like operating systems, it’s painfully sticky. Banks might rebrand, renovate branches, or swap CEOs, but replacing the core system is so risky and disruptive that many institutions stick with the same platform for years—sometimes decades.

By the early 1990s, Systematics was big enough that it stopped being just a vendor and started looking like an asset. ALLTEL Corporation—a telecommunications company that had expanded into information services—acquired Systematics and rolled it into what became ALLTEL Information Services. It’s a pattern you’ll see repeatedly in this industry: critical fintech “plumbing” gets bought by a larger conglomerate for diversification, then later reshuffled as strategy changes.

Then came the dot-com boom and bust. While flashier fintechs raised huge sums on grand promises to disintermediate banks entirely, ALLTEL’s financial services unit kept doing the unglamorous work of processing transactions and keeping bank operations running. When the bubble popped and the funding dried up, many of those would-be disruptors disappeared. The plumbing companies didn’t have the luxury of hype cycles. Banks still needed their systems to work on Monday morning.

The pivotal turn arrived in 2003—from an acquirer almost no one would have predicted. Fidelity National Financial, a Jacksonville-based title insurance company, agreed to buy ALLTEL’s information services division for about $1 billion. Wall Street understandably did a double take. Why would a title insurer want a banking technology business?

The answer was William Foley II, Fidelity National Financial’s chairman and a famed dealmaker. Foley had already built Fidelity National Financial into the largest title insurer in the country through aggressive consolidation. He saw a familiar opportunity in banking technology: a fragmented market full of subscale providers, each strong in a narrow niche, none powerful enough to set the terms of the industry.

In Foley’s view, this was a scale business. The bigger you are, the more you can spread fixed costs across transactions, the more you can invest in product development, and the more services you can bundle into a single relationship. A disciplined roll-up could turn a patchwork of regional vendors into a platform business with real gravity.

The deal also made more sense than it looked at first glance. Title insurance and banking technology share the traits that Foley loved: recurring revenue, high switching costs, and a kind of “must-have” status. Customers don’t buy them because they’re exciting. They buy them because the system fails without them.

After the acquisition, the business was renamed Fidelity National Information Services—FIS—and it became the foundation for what came next.

Because the Systematics story isn’t just an origin tale. It’s the template for FIS’s moat: deep operational integration, switching costs measured in years, and a service model that produces predictable recurring revenue. Those characteristics were forged in the mainframe era—and they remained the bedrock of the company as it entered its acquisition-fueled expansion.

III. The Roll-Up Playbook: Building Through Acquisitions (2003-2009)

FIS didn’t become a global piece of financial infrastructure by patiently compounding organic growth. It got there the way William Foley liked to build: by buying its way to scale, then squeezing value out of what it bought.

The thesis was simple, almost mechanical. Find subscale competitors with sticky client relationships and useful technology. Acquire them. Cut the duplicate costs—data centers, back offices, overlapping products. Then sell the broader menu to the combined customer base. Repeat. In a market where switching vendors can feel like open-heart surgery, every acquired customer relationship wasn’t just revenue. It was a long-lived annuity.

In 2005, FIS went public, giving the company both currency and credibility for what came next. The IPO priced at $12.50 per share and valued FIS at roughly $2.3 billion. Analysts weren’t exactly breathless—this was still “bank back-office plumbing,” a category most of Wall Street ignored. But the public markets did what Foley needed them to do: they funded the machine.

The first big step was 2006, when FIS bought Certegy for $4.4 billion. Certegy had been spun out of Equifax and made its name in check verification, card processing, and payment services. The deal was transformative. It roughly doubled FIS’s revenue and, just as importantly, pushed the company beyond its bank-heavy roots. Certegy brought relationships with retailers and card issuers—adjacent customers who cared about payments and risk, not core deposits and loans.

This was also where FIS proved it could integrate at scale. Management targeted about $200 million of cost synergies, largely by consolidating data centers, eliminating duplicate corporate functions, and rationalizing overlapping offerings. Skeptics called it ambitious. FIS ended up beating those targets, and the market took note. The roll-up wasn’t just a strategy. It was becoming a capability.

A year later, in 2007, FIS added eFunds for $1.8 billion. eFunds specialized in electronic payments, risk management, and prepaid services—categories that were growing faster than traditional check-based systems. It also added international exposure, particularly in emerging markets, and brought more sophisticated tools around fraud detection and authentication. As commerce moved online, those weren’t nice-to-haves. They were quickly becoming table stakes.

Then the world changed.

In September 2008, Lehman Brothers collapsed, credit markets seized, and confidence in the financial system cracked. For most companies, that’s when you slam the brakes. For FIS, it was the kind of environment where Foley’s playbook could get sharper.

The crisis created a strange but powerful dynamic for financial technology providers. Banks were under extreme pressure—but that pressure made them even more dependent on the vendors who kept their operations running. Budgets got scrutinized, sure, but core systems weren’t optional. And while clients clung tighter to proven infrastructure, smaller competitors struggled to raise capital or reassure customers.

In February 2009, in the teeth of that uncertainty, FIS announced its biggest move yet: a $2.8 billion acquisition of Metavante. Metavante was a major rival in core banking and payments, with especially strong positions in healthcare payments and image-based check processing. Put together, the combined company crossed $5 billion in revenue and, by sheer breadth and footprint, established FIS as the largest technology provider to the global financial industry.

The timing was audacious. While others hoarded cash, FIS leaned in—deploying capital when valuations were depressed and when sellers were far more willing to take a deal. In a market where survival mattered more than upside, Metavante’s shareholders accepted terms that might have looked modest pre-crisis, but felt attractive compared to the alternatives in early 2009.

By the time Metavante was folded in, FIS had something close to critical mass. It served more than 14,000 financial institutions around the world. Its core platforms ran daily operations for thousands of banks and credit unions. Its rails processed billions of transactions. The roll-up had turned a once-regional provider into a diversified, more resilient platform—one with real scale advantages.

That scale mattered because financial technology has punishing fixed costs. You pay upfront for software development, security, compliance, and infrastructure, and you earn it back transaction by transaction. The bigger your network, the more efficiently you can spread those costs. Size also buys you credibility: if you’re a bank deciding who should run your most mission-critical systems, “too big to fail” is an attractive feature in a vendor.

But scale has a dark side: complexity. Every acquisition added a new technology stack, a new set of contracts, a new culture, and a new backlog of integration work. Some platforms were hard to modernize. Some customer relationships shifted from personal to bureaucratic. The art of the roll-up isn’t just buying. It’s knowing when you’ve reached the point where the next deal adds more friction than fuel.

Still, by 2009, the results were undeniable. FIS had earned a spot on the Fortune 500. A business acquired for about $1 billion just six years earlier was now valued north of $10 billion. The roll-up playbook had worked—spectacularly.

The open question was whether it would keep working as the market evolved, and as the deals got bigger, riskier, and harder to digest.

IV. The SunGard Acquisition: Expanding the Empire (2015)

When Gary Norcross became CEO in 2015, he inherited a company that had done exactly what it set out to do: it had rolled up huge chunks of retail banking technology and built a fortress of sticky client relationships. But that success created a new problem. Core banking was mature. Banks were steadily digitizing, but they weren’t about to double their tech budgets. Payments growth was real, but it was crowded, competitive, and getting more so.

If FIS wanted to keep compounding like it had in the Foley years, it needed a new frontier.

That frontier was SunGard.

SunGard was a sprawling financial technology conglomerate that lived in a different part of the financial ecosystem than FIS. Where FIS was strongest in retail banking, SunGard sold into institutional markets: asset managers, hedge funds, trading desks, custodians, and corporate treasurers. On paper, it was exactly the kind of adjacency that acquisition strategists dream about—minimal customer overlap, different products, and a chance to expand the addressable market without cannibalizing what you already own.

SunGard also came with a backstory that practically screamed “deal opportunity.” It started in 1983 as a disaster recovery provider for financial institutions—backup computing capacity, built for an industry that cannot afford downtime. Over time, it expanded through acquisition into software for trading, risk management, asset management, and treasury operations. Then, in 2005, a private equity consortium took it private in an $11.4 billion leveraged buyout—one of the biggest LBOs of its era.

By 2015, those owners were ready for an exit. SunGard had grown, but it was still carrying the weight of that leveraged buyout debt. For FIS, this was the classic setup: a valuable franchise, motivated sellers, and a price that could make sense if you believed you could do the hard work after the press release.

The deal closed in November 2015 at an enterprise value of about $9.1 billion. FIS paid $2.3 billion in cash, issued $2.8 billion in stock, and assumed SunGard’s substantial debt. Overnight, FIS’s annual revenue jumped to around $9.3 billion, cementing it as one of the largest financial technology companies in the world.

Strategically, the logic was straightforward. SunGard pulled FIS into faster-growing institutional segments—asset management, capital markets, and corporate treasury—at a time when retail banking was becoming a steadier, lower-growth engine. It also expanded FIS internationally, especially across Europe and Asia, accelerating geographic diversification.

Operationally, though, the real story was integration—because SunGard wasn’t one cohesive business. It was a portfolio, assembled over decades, with wildly different product quality and momentum. Some offerings were clear market leaders with devoted customers. Others were aging platforms that had seen limited investment during the private equity years. FIS had to decide what to modernize, what to maintain for legacy clients, and what to quietly wind down. None of those choices are easy when customers are running mission-critical systems on the software you might want to retire.

And the institutional world demanded a different skill set than retail banking. Trading systems needed extreme performance. Risk platforms depended on sophisticated modeling. Service expectations were different, and so were the consequences of failure. FIS had to build new organizational muscles while also delivering the cost synergies that made the deal financially attractive in the first place.

Even with that complexity, SunGard ultimately did what FIS needed it to do. It gave the company real footing in institutional markets, and it reduced reliance on any single client segment. Cost synergies came in above initial expectations. By 2018, SunGard’s operations were integrated, and the combined platform was throwing off strong cash flows.

But SunGard also signaled something bigger: FIS’s ambitions were expanding. This wasn’t just a company trying to be the best vendor to banks. Under Norcross, FIS was positioning itself as a comprehensive financial technology platform—capable of serving almost any financial institution, across almost any workflow, almost anywhere in the world.

That ambition set the stage for the next move. And the next move would be much bigger—big enough to test whether the roll-up playbook still worked when the stakes, the integration burden, and the market scrutiny all ratcheted up at once.

For investors, SunGard is a reminder of the gap between strategic logic and operational execution. The deal made sense on paper. The value only emerged through years of difficult integration work. The same pattern would reappear—at vastly larger scale—in what FIS did next.

V. The Worldpay Saga: Triumph and Retreat (2019-2024)

In March 2019, FIS made the kind of announcement that forces an entire industry to stop and stare: it agreed to buy Worldpay in a $35 billion deal, the largest acquisition fintech had ever seen. The timing wasn’t subtle. Just weeks earlier, Fiserv—one of FIS’s biggest rivals—had unveiled its own mega-merger with First Data. Payments was consolidating fast, and the message was clear: if you weren’t scaling up, you were about to get scaled over.

The logic behind these tie-ups was straightforward. Merchant payment processing—the behind-the-scenes work that lets a store or website accept card payments—is a brutal scale business. Margins are thin, competition is relentless, and the winners are the ones who can spread tech spend and fraud tools across oceans of transactions, negotiate better economics, and sell merchants more than just “swipe and approve.”

Worldpay looked like the prize. It was a giant in merchant acquiring, built from the combination of Vantiv and the original Worldpay, with reach from global e-commerce platforms all the way down to neighborhood restaurants. Its platform was considered modern by industry standards, its relationships were sticky, and its exposure to e-commerce—the fastest-growing corner of payments—gave the deal a compelling growth story.

The terms were precise and very public: Worldpay shareholders would receive 0.9287 FIS shares plus $11 in cash for each Worldpay share, putting the value at about $35 billion. The combined company was expected to generate more than $12 billion in revenue and to process more payment transactions than any other company in the world. Strategically, FIS was aiming for something bigger than “a larger payments processor.” It was pitching an end-to-end payments infrastructure company—banking technology on one side, merchant acquiring on the other—touching both halves of the same transaction.

The deal closed in July 2019. Months later, the world shut down.

At first, COVID seemed like it might validate the bet. Physical commerce stalled, digital payments surged, and e-commerce adoption leapt forward. Worldpay’s online mix—about 40% of transaction volume—appeared well positioned for that shift.

But the reality didn’t cooperate. Entire merchant categories that mattered to Worldpay—travel and entertainment, restaurants, and large swaths of physical retail—fell off a cliff. E-commerce growth helped, but it didn’t neatly cancel out the damage elsewhere. And as the pandemic dragged on, the hard parts of the deal started to show.

Integration was rougher than expected. FIS was an integration machine by design: disciplined processes, standardized playbooks, a culture built around stitching acquisitions into one operating model. Worldpay operated more like a high-velocity payments company—more entrepreneurial, more local decision-making, faster iteration. Putting those together created friction in the places that matter most: priorities, accountability, and speed.

Then there was the technology. Payments is real time, always on, and unforgiving. You don’t “pause” merchant acquiring while you migrate systems; transactions keep flowing and uptime is existential. FIS ran into technical complexity that slowed the work, delayed synergy capture, and demanded more investment than anticipated.

By 2022, investors weren’t buying the vision. FIS’s share price had fallen substantially from post-deal highs. Activist pressure arrived with a clean argument: the combined company was worth less together than apart. Payments, they said, should command a richer valuation than a steadier, slower-growing banking technology franchise—and keeping them under one roof was dragging the multiple down.

Change followed quickly. In January 2023, FIS announced that Stephanie Ferris would succeed Gary Norcross as CEO. A month later, the company confirmed it was exploring strategic alternatives for its merchant business—the same asset that had been positioned as the crown jewel of the Worldpay acquisition.

The decision landed in July 2023. FIS agreed to sell a 55% stake in Worldpay to GTCR, valuing Worldpay at about $18.5 billion. FIS would receive $11.7 billion in proceeds and keep a 45% stake. It was a stunning reversal: four years after paying $35 billion, FIS was now marking the business at roughly half that value.

The retreat was painful, but it also brought clarity. Separating Worldpay let FIS refocus on its core banking and capital markets technology franchises. FIS said it would use proceeds to reduce debt and repurchase shares, strengthening the balance sheet and returning capital to shareholders. And keeping a sizable minority stake preserved some upside if Worldpay performed better under GTCR’s ownership.

So what actually went wrong? It wasn’t one thing. The price in 2019 was rich, in a market where payments assets were hot and competition was fierce. Then COVID delivered a shock no model captured. Integration didn’t go smoothly, culturally or technically. And as interest rates rose and growth stocks fell out of favor, the market’s appetite for payments valuations cooled dramatically.

But the deeper lesson is about the limits of a playbook. Rolling up banking technology—stable operations, long contracts, similar customer needs—is hard, but it’s a familiar kind of hard. A high-growth merchant acquiring platform is different: faster cycles, fiercer competition, and less tolerance for integration drag. The skills that made FIS great at one game didn’t automatically translate to the other.

For investors, the Worldpay saga is what makes the FIS story so instructive. This was a company that had executed deal after deal successfully for years. The pattern looked proven. And yet the biggest bet—made at exactly the moment the industry was racing into consolidation—became the one that forced a strategic retreat.

VI. Core Business Deep Dive: The Infrastructure Monopoly

To understand FIS after the partial Worldpay exit, you have to look at what’s still standing. What remains is the part of the company that was always the real engine: a global financial technology utility for banks, capital markets firms, and corporations. FIS employed about 56,000 people across 58 countries and served more than 20,000 clients—running systems most consumers never notice, but touch constantly.

Operationally, the company was organized into two main segments: Banking Solutions and Capital Market Solutions. A smaller bucket, Corporate and Other, covered shared functions and the messy, necessary work of transitional and wind-down activities tied to the merchant business separation.

Banking Solutions is the direct descendant of Systematics—the Little Rock DNA. This is where FIS sells core banking platforms: the systems of record for deposits, loans, and accounts. Around that core, it bundles the surrounding layer modern banks need to function: digital banking (mobile and online experiences), bank payment processing, and a long list of adjacent tools like fraud prevention, compliance, and analytics.

This is where FIS’s moat is at its deepest. A bank’s core platform isn’t “software you buy.” It’s the central nervous system. Everything plugs into it. Staff live in it all day. Regulatory reporting depends on it. Changing it is less like switching email providers and more like swapping out the engine mid-flight.

In practice, replacing a core system can take two to five years, cost tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars, and carry real risk of operational disruption. That’s why banks routinely stay on the same core for decades—even when better alternatives exist. The switching costs aren’t theoretical; they’re measured in time, money, and career risk.

FIS serves the full spectrum, from single-branch community banks to multinational institutions operating across continents. Those customers don’t all want the same thing, which is why FIS maintains multiple platform offerings. That breadth adds complexity—more products to maintain and invest in—but it also gives FIS coverage across the market, letting it meet customers where they are instead of forcing a one-size-fits-all platform.

Capital Market Solutions is the other pillar, and it largely traces back to SunGard. Here, the customers are institutional: asset managers, broker-dealers, hedge funds, insurers, and corporate treasurers. The products are the systems that keep markets and money moving—investment management platforms, trading systems, risk tools, and treasury management solutions.

This business looks and feels different from Banking Solutions. Switching costs still matter, but the buyers are typically more sophisticated and more willing to evaluate alternatives. Competition can come from established providers like SS&C Technologies and Broadridge, or from the biggest institutions simply deciding to build more themselves. Success is driven by winning mandates, expanding existing relationships, and riding the underlying activity that pushes volumes—like assets under management and trading activity.

Put the segments together and you get FIS’s signature profile: recurring revenue, long contracts, and customer relationships that often last for decades. Many deals are structured as multi-year commitments with a base fee, plus variable charges tied to transaction volumes or assets. That tends to produce growth that’s steady rather than explosive. This isn’t a “breakout quarter” kind of company. It’s a “still running flawlessly” kind of company.

The cost side rhymes with that. Running data centers, maintaining software, and supporting clients are ongoing, predictable expenses—less prone to sudden swings than businesses that live and die on discretionary spending. That visibility, paired with recurring revenue, is what has historically made FIS a strong free-cash-flow generator—cash it can use for acquisitions, dividends, and share repurchases.

Scale also creates pockets of network effects. As more banks run on FIS payment processing infrastructure, connectivity and capabilities tend to expand. As more institutional clients run workflows through FIS platforms, the ecosystem can become more valuable in subtle ways. These aren’t the massive, winner-take-all network effects of Visa or Mastercard, but they’re meaningful—and they reinforce the basic advantage of being deeply embedded.

Finally, there’s what FIS calls its fintech enablement strategy: the company’s answer to disruption. Instead of treating every fintech startup as an enemy, FIS positions itself as the infrastructure layer that helps banks and fintechs ship products faster. Banks can use FIS platforms and APIs to deliver modern digital experiences without building everything in-house. Fintechs can tap into capabilities like payment processing, compliance tooling, and account management without reinventing the plumbing.

It’s a pragmatic stance, and it reflects a hard-earned reality. FIS can’t out-innovate thousands of startups across every corner of fintech. But it can aim to be the system they all have to connect to—making itself hard to bypass, no matter which front-end brands win the customer relationship.

VII. Business Model & Financial Analysis

At first glance, FIS’s financials can look messy—an artifact of decades of acquisitions, product overlap, and businesses that bill in very different ways. But underneath the complexity, the money-making engine is pretty consistent. FIS gets paid for running the plumbing: long-term software relationships, high-volume processing, and the services required to implement and maintain both.

The revenue comes in a few main flavors: software licensing and maintenance, transaction processing fees, professional services for implementations and customization, and some hardware-related sales. The mix shifts depending on whether the customer is a retail bank, an institutional trading shop, or a corporate treasury team. But the common thread is that once FIS is embedded, it tends to stay embedded.

That’s why recurring revenue is the foundation. FIS has said that about 85% of revenue is recurring, typically locked in through multi-year contracts with built-in escalators. This is the part Wall Street tends to like: it’s visible, it’s sticky, and it turns the business into a compounding machine. Even if growth looks “boring” in any one year, renewals and steady pricing uplift add up over time.

The more variable piece is transaction processing. When consumers spend more and businesses move more money, FIS earns more. When trading activity increases, Capital Market Solutions tends to benefit. That introduces some economic sensitivity—up in strong environments, down in slow ones—but it’s buffered by the recurring base. FIS doesn’t live or die by one quarter of volumes. It’s not a purely cyclical business; it’s a cyclical tail attached to a long-contract core.

Professional services fill in the rest. These are the fees for implementations, integrations, and customization—work that can be substantial when a new client comes on board or an existing client upgrades a major system. This revenue can be meaningful, but it’s generally lower margin than software and processing because it’s labor-intensive. It’s also not the part of the business you want to depend on for growth. Services are often what gets you in the door; the annuity comes after.

The margin profile reflects what FIS is: infrastructure. Once a platform is built, the incremental cost of running more volume through it is relatively low, so gross margins are strong—above 50%. Operating margins have historically been in the 20–25% range, but they’ve been squeezed in recent years by acquisition-related costs, restructuring, and the operational fallout from the Worldpay era. As those integration and restructuring activities faded, management’s pitch has been straightforward: get margins back toward historical levels.

Capital allocation tells the same story of evolution. For years, FIS reinvested cash flow into the next deal, feeding the roll-up machine. More recently—especially after selling a majority stake in Worldpay to GTCR—the emphasis shifted to cleaning up the balance sheet and returning capital. The $11.7 billion in proceeds from that transaction gave FIS room to pay down debt, which matters a lot in a higher-rate environment: less leverage, lower interest expense, and more flexibility.

Shareholder returns have come through a blend of dividends and buybacks. FIS began paying dividends in 2008 and has increased them over time, signaling confidence in the durability of the cash flows. Repurchases have been more opportunistic—accelerating when management believes the stock is undervalued—rather than a perfectly steady program. Together, they create a familiar playbook for mature infrastructure businesses: a reliable payout with room for tactical capital returns.

It’s also helpful to anchor FIS against its closest peers. Fiserv—especially after acquiring First Data—is the most direct comparison: a scaled fintech platform spanning banking and merchant payments. Jack Henry overlaps heavily on core banking technology but leans more toward smaller institutions and a more unified product stack. Broadridge is the outlier in customer overlap but a useful contrast in business quality: it dominates investor communications and parts of wealth tech, with deep regulatory and workflow entrenchment in its niches.

Each has a different edge. Fiserv has meaningful growth exposure through merchant, Jack Henry benefits from a reputation for modern platforms that appeal to banks trying to upgrade, and Broadridge has built formidable moats where regulation and inertia reinforce each other.

FIS’s advantage is breadth—especially after you combine its banking franchise with its capital markets footprint. No competitor matches that exact mix of core banking strength, payment processing infrastructure, and institutional technology offerings under one roof. That breadth can make FIS more than a vendor. It can make it a strategic partner with multiple ways to expand inside an account.

The catch is that the last several years have been anything but smooth. The Worldpay acquisition, pandemic disruption, integration challenges, and the eventual partial divestiture created real turbulence in reported revenue and profitability. Revenue rose above $14 billion when merchant acquiring was included, then fell when that business was deconsolidated. Profitability swung too, weighed down by one-time charges and operational disruption.

So when you look forward, the question isn’t whether the model can generate cash—it can. The question is whether the post-Worldpay FIS can get back to steady execution. The metrics that matter are organic revenue growth in the remaining businesses, operating margin progression as restructuring fades, and free cash flow generation that supports dividends, buybacks, and continued balance sheet strength. Management has outlined targets. Hitting them is what determines whether FIS returns to its old identity: not a deal story, but a compounding infrastructure utility.

VIII. Playbook: Lessons in Building Financial Infrastructure

The FIS story is a case study in both the power and the limits of the roll-up. For nearly two decades, the company bought businesses with discipline, stitched them together with a repeatable integration muscle, and turned a fragmented market into something closer to an operating utility. Then it made one transformative bet where that same playbook stopped working the way it always had.

To see the pattern, look at what the “good” deals had in common. They were priced with at least some margin for error. They were adjacent to what FIS already did—similar customers, similar contracts, similar operating rhythms. And the synergy story was mostly about costs you could actually remove: consolidating data centers, eliminating duplicated corporate overhead, rationalizing overlapping platforms. Less “imagine the cross-sell,” more “we can literally take this expense out.”

Certegy, eFunds, Metavante, and SunGard generally followed that script. Each was meaningful, but none was so large that a stumble could destabilize the entire company. Each expanded the product set and the customer universe without turning the combined organization into a cultural civil war. And each came with integration work that was hard, but legible.

Worldpay was different in the ways that matter. The price was aggressive, set in a market that was paying peak multiples for payments scale. The business itself ran on a different tempo—merchant acquiring is faster, more competitive, and less forgiving than bank core processing. The synergy story leaned more on growth and revenue opportunities that were harder to realize in practice. And the sheer scale meant that if integration slowed down or priorities diverged, it didn’t just bruise one division—it pulled focus and oxygen from the whole enterprise.

The takeaway isn’t “acquisitions are bad.” FIS is proof they can be a compounding machine. The real lesson is that great acquirers have to know where their edge ends. Integration capability isn’t a generic superpower. It’s contextual. What works brilliantly when you’re combining similar plumbing businesses doesn’t automatically translate when you buy a different kind of engine.

The other tension running through FIS’s history is infrastructure versus innovation. Financial infrastructure wins by being boring in the best way: stable, reliable, predictable. Banks don’t want their core systems to be “cutting-edge.” They want them to work perfectly, every day, under regulatory scrutiny, through crises, and across decades.

And yet the industry around that infrastructure keeps changing. Digital banking, real-time payments, open banking APIs, and embedded finance have reshaped customer expectations and forced banks to ship new features faster. Infrastructure providers can’t stay frozen in time. They have to modernize without breaking trust—and without breaking production.

FIS’s approach has been to treat innovation like an overlay rather than a rewrite. New capabilities get built in more focused teams, rolled out carefully, and tested extensively before they touch the systems that run deposits and settlements. The front-end and “edge” products—digital experiences, APIs, analytics, fraud tools—can move faster. The core evolves more cautiously. It’s not glamorous, but it matches what clients are actually buying: progress without drama.

Then there’s the activist chapter. D.E. Shaw and other activists pushed FIS to reconsider the merchant business, arguing the combined company was being valued like a muddled conglomerate instead of two businesses that deserved different strategies and different multiples. Whatever you think of activism in general, the pressure forced a hard conversation the market was already having. And the eventual Worldpay separation reflected the underlying point: sometimes the best strategic move isn’t to integrate harder. It’s to simplify.

That’s a broader warning about mega-mergers in fintech. The industry is full of combinations that looked inevitable in the announcement and messy in the aftermath. The mistake is usually the same: underestimating how hard integration becomes when technology is the product, uptime is existential, and customers can’t tolerate disruption. In these businesses, “synergies” aren’t just a spreadsheet exercise—they’re changes to live systems that move real money.

Finally, the FIS story reinforces the core skill of B2B financial technology: building switching-cost moats. The durability here doesn’t come from any single feature that a competitor can copy. It comes from being embedded in the customer’s operations—customizations, workflows, reporting, training, compliance processes, and a thousand little integrations that accumulate over years. That’s the moat. Protecting it, deepening it, and modernizing around it is what makes an infrastructure company like FIS so hard to dislodge—and so valuable when it’s run well.

IX. Bear vs. Bull Case & Future Outlook

The debate around FIS ultimately comes down to one question: in a world where financial services keeps changing, how permanent is the plumbing?

The bull case starts with a simple reality: FIS runs systems that banks can’t afford to get wrong. Its core platforms sit underneath deposits, loans, account servicing, and payments for thousands of institutions. For those customers, ripping out FIS isn’t a vendor swap. It’s a multi-year, high-risk transformation where a bad cutover can create outages, regulatory issues, and reputational damage. That operational gravity creates a kind of revenue floor that’s hard to find in most software categories.

Layer on the contract structure and the case gets stronger. FIS has said about 85% of revenue is recurring and tied up in multi-year agreements. That kind of visibility doesn’t just make forecasts easier; it gives management real flexibility. It supports the dividend, enables buybacks when the stock is cheap, and cushions the business when the macro environment gets noisy.

Bulls also point to a quieter growth engine: banking digitization. Even in mature markets, banks are still spending on digital channels, real-time payments, fraud tools, and analytics. Those upgrades may not require ripping out the core, but they do create opportunities around the core. And in emerging markets, the runway can be longer as financial inclusion and modernization drive demand for industrial-strength infrastructure.

Finally, there’s the post-Worldpay argument: focus equals execution. With merchant acquiring no longer the center of gravity, FIS can put management attention and investment back into the franchises where it has the deepest moats. The pitch is less about being everything to everyone, and more about being excellent at the mission-critical layers where FIS already wins. A smaller, more focused FIS could end up being a better-run, more consistent FIS.

The bear case begins where most legacy infrastructure stories do: technology debt. FIS is a product of decades of acquisitions, and that history shows up in the codebase. Some platforms are old, complex, and expensive to modernize. As cloud-native competitors push more flexible architectures, faster deployment cycles, and cleaner integration patterns, FIS risks losing deals at the margin and facing gradual share erosion over time.

Bears also widen the lens beyond bank cores. Even if FIS holds onto existing bank relationships, fintech disruption could still matter by changing who owns the customer. If consumers increasingly access financial services through neobanks, embedded finance, or big tech platforms, traditional banks may have less leverage and slower growth. In that world, the core banking systems still run—but the value shifts toward the layers closer to the end user, where FIS may capture less of the upside.

And the integration hangover didn’t disappear with Worldpay. Complexity is still baked in. FIS maintains multiple overlapping products across categories, the natural outcome of rolling up a fragmented industry. Rationalizing that portfolio takes time, money, and hard trade-offs. Left unchecked, it can slow innovation, raise costs, and make the organization harder to operate.

Frameworks help clarify what’s real here. Under Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, FIS clearly has switching costs—arguably its most important and most durable advantage. Scale economies matter too: this is a fixed-cost-heavy business where size helps fund security, compliance, and platform investment. Network effects exist in parts of payments and certain institutional workflows, but they’re not the dominant force in the way they are for consumer networks.

Other “powers” are weaker. FIS doesn’t win because of consumer branding. It doesn’t have a business model that inherently counter-positions competitors. And while it has substantial resources, well-capitalized rivals can often match investment over time.

Porter’s Five Forces tells a similar story. Supplier power is limited; FIS buys talent and technology in competitive markets. Buyer power is constrained by switching costs, but it’s not zero—large banks negotiate hard, and new deals are competitive. New entrants face real barriers in security, regulation, and credibility, but fintech funding has a way of finding routes around traditional gatekeepers. Substitutes are the long-term wildcard: new delivery models for financial services could reduce the importance of the traditional banking stack. Rivalry among incumbents remains intense, even if churn is muted.

For investors, the scoreboard is mercifully small. The first metric is organic revenue growth in Banking Solutions and Capital Market Solutions—the cleanest read on whether the franchise is holding and expanding without relying on deal-making. Consistent mid-single-digit organic growth supports the “durable utility” narrative; slippage is often the earliest sign of competitive pressure.

The second is free cash flow conversion: how much of reported revenue reliably turns into free cash flow that can pay down debt, fund the dividend, and support buybacks. If conversion stays strong, FIS can self-fund modernization and still return capital. If it deteriorates, it suggests the business is being forced to spend more just to stand still.

That’s the future outlook in a nutshell: FIS can absolutely be a compounding infrastructure utility again—but only if it proves it can modernize, simplify, and execute with the same discipline that once made the roll-up machine so formidable.

X. Power Analysis & Final Thoughts

Fidelity National Information Services embodies a particular kind of business power: not the power of a beloved brand, not the power of viral adoption, and not even the classic winner-take-all network effect. FIS’s advantage comes from something more unromantic and, in many ways, more durable: the sheer difficulty of replacing it. This is switching-cost power in its purest form, built over decades of operational integration and reinforced by clients who can’t afford even a few minutes of instability.

The comparison to other infrastructure plays makes the distinction clearer. Visa and Mastercard run global networks with true network effects—each new cardholder and merchant makes the system more valuable to everyone else. Exchanges like NYSE and CME benefit from liquidity and regulation—once the market is there, it’s incredibly hard to dislodge. FIS’s power is different. It’s not that more banks using FIS automatically makes FIS more valuable to every other bank. It’s that once a bank is running on FIS, extracting it becomes a multi-year project with real operational and regulatory risk. In a category where “it works” is the product, that kind of entrenchment is the moat.

That moat creates both an opportunity and a constraint. The opportunity is resilience. FIS can absorb competitive pressure, shifting technology cycles, and even periods of uneven execution in a way that many faster-moving fintechs simply can’t. The constraint is that switching costs mostly defend what you already have; they don’t guarantee what you’ll win next. To grow, FIS still has to compete for new contracts, expand within existing clients, and modernize its stack—without breaking the very stability customers are paying for.

That tension—the infrastructure provider’s dilemma—will define the next chapter. Clients want modern APIs, real-time capabilities, better digital experiences, and smarter fraud tooling. But they want those things delivered like a utility upgrade: quietly, safely, and without drama. Investors, meanwhile, want improvement in growth and margins, but they also prize predictability. Management has to thread that needle, funding modernization while protecting uptime, security, and trust.

The post-Worldpay FIS is also a different company than the pre-Worldpay one: smaller, more focused, less leveraged, and more cautious after seeing how painful a mega-merger can get when integration complexity meets a changing market. The core assets are still there—deep client relationships, mission-critical infrastructure, and recurring revenue. What changes now is the burden of proof. From here, execution matters more than storytelling. The question is whether FIS can rebuild credibility by delivering steady organic growth, cleaner operations, and the kind of reliability that made the franchise valuable in the first place.

For long-term investors, owning FIS is ultimately a bet on the durability of the financial system’s plumbing. The bull thesis says banks will keep outsourcing core infrastructure, switching costs will continue to protect incumbents, and steady cash generation will compound over time. The bear thesis says technology shifts will gradually weaken those moats, traditional banks will lose influence to new distribution models, and legacy platforms will turn from an asset into an anchor.

There are no easy answers in financial infrastructure. These aren’t rocket-ship growth stories, and they aren’t simple “cheap cash flow” situations either. They reward patience, punish complacency, and demand a clear-eyed view of competition. FIS might be one of the best examples of the category’s full arc: the immense value created by building indispensable infrastructure—and the equally real consequences of reaching too far, too fast.

XI. Recent News

By the fourth quarter of 2024 and into early 2025, the story around FIS was less about big, splashy deals and more about whether the company could execute in a post-Worldpay world. Management’s updates centered on the basics that matter for an infrastructure business: modernizing technology without disrupting uptime, and running cost optimization programs that could rebuild margins now that the company was more focused.

Worldpay, meanwhile, didn’t disappear from the FIS narrative just because control changed hands. FIS’s retained stake stayed on the balance sheet, and investors continued to track how the now-majority-private-equity-owned business was performing—because any swing in Worldpay’s results or strategic direction could flow back to FIS through both the equity value and ongoing commercial relationships between the companies.

Outside the company, the backdrop kept shifting. Real-time payments continued to accelerate. Open banking initiatives pushed more connectivity and data-sharing into the mainstream. Regulators stayed active. For FIS, those trends cut both ways: they create demand for new capabilities, but they also raise the bar for speed, security, and compliance. Management commentary on these forces became one of the clearest windows into how FIS planned to allocate investment going forward.

On the Street, the tone after the Worldpay separation was largely about clarity. A simpler FIS was easier to model, easier to compare against peers, and easier to value. Analysts increasingly framed the next chapter around a handful of measurable benchmarks—organic growth in the remaining segments, margin progression as restructuring faded, and capital returns—creating a cleaner scoreboard that would either rebuild confidence or expose lingering execution gaps.

XII. Links & Resources

Company Filings and Investor Materials

- FIS annual reports (10-Ks) via SEC EDGAR

- Quarterly earnings presentations and call transcripts on the FIS Investor Relations site

- Proxy statements for executive compensation, incentives, and governance details

Key Transaction Documents

- Worldpay acquisition materials and agreement (2019)

- GTCR deal announcement and related documents (2023)

- SunGard merger documentation (2015)

Industry Research

- The Federal Reserve Payments Study for U.S. payments data and long-term trends

- Bank for International Settlements (BIS) reports on global payment and settlement infrastructure

- McKinsey Global Payments Report for competitive dynamics and industry growth themes

Further Reading

- Payments: From Cash to Crypto (for the broader arc of how payments evolved)

- Background histories on Systematics and SunGard to trace the roots of today’s FIS

- Analyst research from major investment banks covering the financial technology sector

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music