Fifth Third Bank: The Story of America's Most Uniquely Named Bank

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

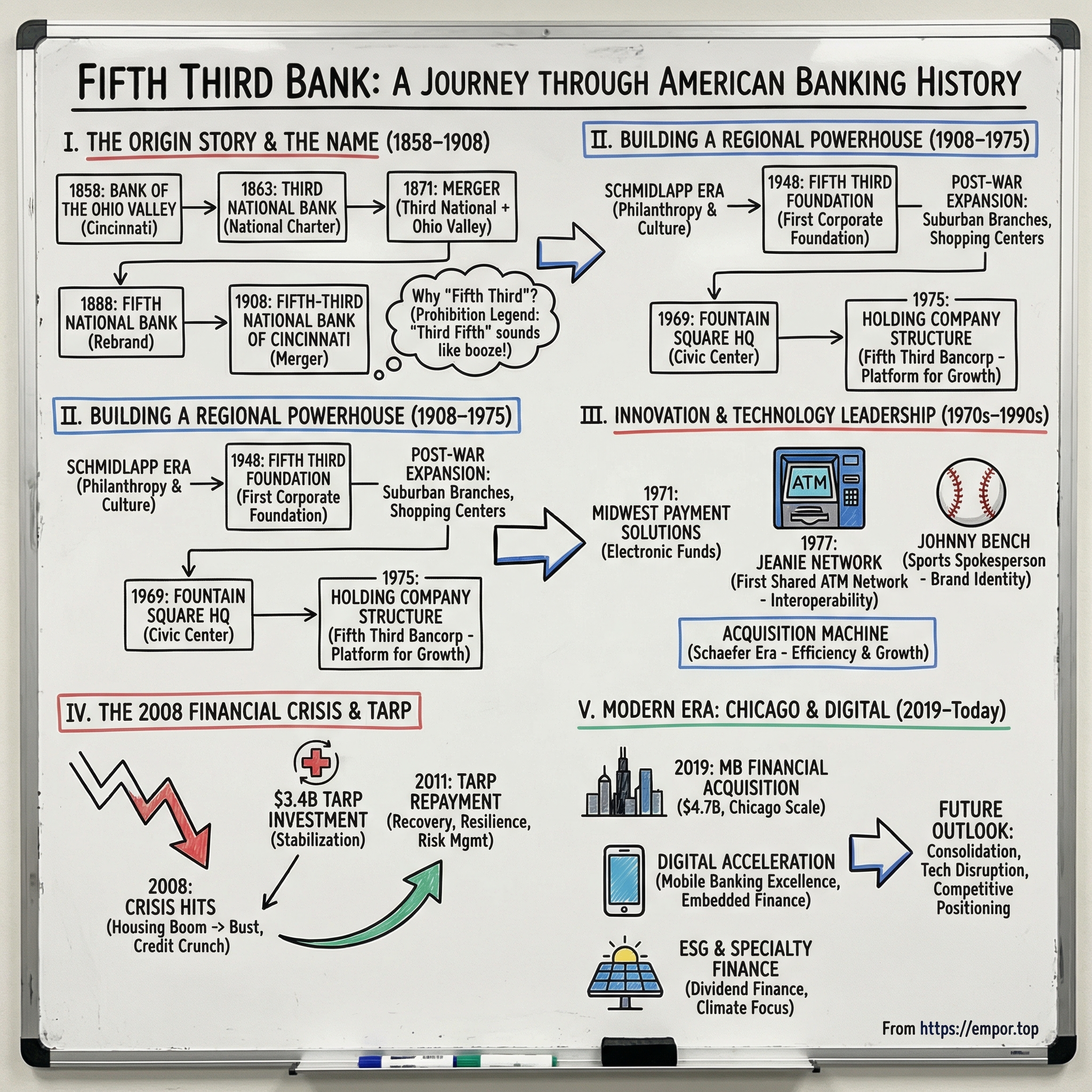

Walk into any of the roughly 1,100 Fifth Third Bank branches across eleven states and you’ll run into one of American banking’s great curiosities: a name that sounds like someone botched a fraction on the chalkboard. Fifth Third Bancorp is headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio, runs more than 2,400 ATMs, and employs nearly 20,000 people. By late 2023 it had over $200 billion in assets and sat at number 321 on the Fortune 500—real scale, real weight, and a name that still makes first-time customers do a double take.

So how did a Civil War–era merger produce one of America’s largest regional banks and the strangest name in finance? That question is the thread we’ll pull through a story that spans 167 years—through the era of wartime bank charters, the Great Depression, two world wars, the 2008 financial crisis, and into the modern age of mobile apps and digital wallets.

This isn’t a balance-sheet tour. Fifth Third’s history is a lens on the evolution of American banking itself: how regulation shaped winners and losers, how regional players fought to grow without losing their roots, and how innovation can come from unexpected places. Along the way, we’ll trace how Fifth Third repeatedly stayed standing when others fell, how it helped push electronic banking forward before most people had ever used an ATM, and how a $4.7 billion deal remade its position in Chicago, the nation’s third-largest city.

A few themes will keep showing up: local identity versus national ambition, the difficulty of moving fast inside a highly regulated business, what it takes to survive a true panic, and the bigger riddle at the heart of banking—how you build lasting advantage in an industry where the core product is money itself.

II. The Strange Name & Founding Story (1858–1908)

The Bank of the Ohio Valley Opens Its Doors

In the summer of 1858, Cincinnati was riding high. More than 160,000 people lived in what they proudly called the Queen City of the West, and the Ohio River made it a commercial superhighway—pulling in farm output from the Midwest and pushing finished goods out to the rest of the country. The city’s slaughterhouses were so prolific it earned the not-so-subtle nickname “Porkopolis,” but it wasn’t just meat. Foundries, breweries, and machine shops were turning Cincinnati into an industrial engine.

That’s the Cincinnati William W. Scarborough bet on when he opened the Bank of the Ohio Valley on June 17, 1858. The logic was simple: rapid growth needs financial plumbing. Merchants needed credit to move goods, manufacturers needed working capital to keep machines running, and farmers needed seasonal loans to survive the long stretch between planting and harvest. Scarborough built his bank to serve the whole ecosystem.

He also picked a brutal moment to start. Only months earlier, the Panic of 1857 had jolted the economy after the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company failed. Across the country, banks were suspending specie payments as depositors demanded gold. Scarborough’s new bank had to earn confidence the hard way—one depositor at a time, one loan at a time—while the public’s trust in the system was still shaken.

The Civil War Creates a New Banking System

Then the Civil War rewired American finance. To fund the Union war effort, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase—a former Cincinnati lawyer and Ohio governor—pushed through the National Banking Act of 1863. It created a new class of nationally chartered banks that could issue a uniform national currency, backed by U.S. government bonds.

Cincinnati moved quickly. On June 23, 1863, not long after Lincoln signed the act, Third National Bank received its charter. Compared to state-chartered banks, the national system offered clear advantages: the ability to issue national bank notes, a stronger stamp of credibility, and a standardized regulatory framework. Third National used that platform to become one of the city’s leading institutions.

Less than a decade later, it made its first defining consolidation move. On April 29, 1871, Third National acquired Scarborough’s Bank of the Ohio Valley—the same bank that had opened in 1858, under the shadow of a panic. It’s a small moment on the calendar, but an important one for the story: even before “Fifth Third” existed, the foundation was already being built through combination.

And Third National kept climbing. By 1882, its capital had reached $16 million, the largest bank capital base in the state of Ohio—an especially meaningful brag in an era when Ohio was one of America’s biggest and most economically vital states.

Fifth National Bank Emerges

While Third National was scaling up, another Cincinnati bank was building its own franchise. Queen City National Bank, formed during the post–Civil War banking boom, operated for years before rebranding in 1888 as Fifth National Bank. The reason wasn’t poetic. It came from its federal charter number in the national banking system—a practical label that would eventually become half of one of the most unusual names in American finance.

Through the 1890s and early 1900s, Fifth National developed its customer base and lending niches, competing hard with Third National and the other Cincinnati banks for commercial business. Cincinnati’s economy was broadening beyond meatpacking into machine tools, printing, soap manufacturing—Procter & Gamble had been founded there—and brewing. In other words, there was plenty of balance-sheet fuel to go around, and both banks learned how to win it.

The 1908 Merger: Birth of a Strange Name

By the early 1900s, American banking was feeling the pull toward consolidation. The Panic of 1907 had shown how quickly fear could spread and how even healthy institutions could get dragged down by a loss of confidence. Bigger, better-capitalized banks looked safer—not just to depositors, but to bankers themselves.

On June 1, 1908, Third National and Fifth National merged, forming the Fifth-Third National Bank of Cincinnati. The hyphen came later and eventually disappeared, but the name itself stuck—and it raised an obvious question: why Fifth Third, and not Third Fifth?

The paper trail for the decision doesn’t survive, but the legend does. The merger happened as prohibitionist sentiment was rising across the country; national Prohibition would arrive in 1919. According to long-running banking folklore, the organizers avoided “Third Fifth” because it could be read like a reference to alcohol—a “fifth,” and specifically three-fifths of one. True or not, the story has been repeated for so long it’s effectively part of the brand.

What isn’t in doubt is what the merger created: a Cincinnati banking heavyweight. Third National brought size and capital; Fifth National brought its own relationships and market position. Together, they had real regional clout in a competitive city.

And that early DNA matters. From the beginning, Fifth Third was not a single clean founding—it was an assembly. A bank formed by absorbing other banks, stitching together systems and customers and cultures. That habit of consolidation, integration, and scaling up would become one of the most consistent through-lines in Fifth Third’s strategy for the next century.

III. Building a Regional Powerhouse (1908–1975)

The Schmidlapp Era and Philanthropic Foundations

After the 1908 merger, the new Fifth Third didn’t just need to get bigger. It needed to get steadier—to become the kind of institution Cincinnati could lean on through whatever came next. And as the bank matured, one name kept echoing through the city’s financial and civic life: Jacob G. Schmidlapp.

Schmidlapp wasn’t simply a banker with good timing. He was a builder of institutions and a model for what corporate citizenship could look like before the phrase existed. In 1890, he organized Union Savings Bank and Trust Company and grew it into a serious player in Cincinnati finance. Over time, Fifth Third would absorb not just pieces of Cincinnati’s banking landscape, but also the culture that leaders like Schmidlapp represented: a belief that a bank’s success and a city’s health are tied together.

That idea became official policy in 1948, when Fifth Third Union Trust created the Fifth Third Foundation—the first corporate foundation established by a financial institution in the United States. At a time when corporate giving was often ad hoc and personality-driven, Fifth Third turned it into infrastructure. It wasn’t just writing checks; it was committing, permanently, to Cincinnati and the communities where it operated.

It also fit the city. Cincinnati had a reputation for companies that played the long game—Procter & Gamble, Kroger, Federated Department Stores—and Fifth Third reflected that same patient, community-minded approach.

World War II and the Home Front

When the U.S. entered World War II after Pearl Harbor, Fifth Third did what banks across the country did: it became part of the machinery of the home front. It sold war bonds, supported local manufacturers shifting into military production, and kept families financially afloat while loved ones shipped overseas.

None of it made headlines the way battlefield victories did, but it mattered. While the fighting raged abroad, Fifth Third handled the transactions that kept Cincinnati moving: payroll for defense contractors, mortgages for workers relocating for factory jobs, and the everyday credit decisions that kept small businesses alive. The war years reinforced what the bank already was becoming—a civic utility as much as a financial one.

Post-War Expansion and Innovation

Then came the postwar boom, and American life reorganized itself around suburbs, highways, and shopping centers. Banking had to follow.

Fifth Third expanded aggressively, and by 1956 it operated 27 offices, including branches located in shopping centers. That seems obvious now; at the time, it was a statement. Banks had traditionally been downtown monuments—marble floors, heavy doors, and architecture designed to signal permanence. Fifth Third’s shopping center branches signaled something else: convenience. Banking wasn’t just a place you went when you had to. It was becoming something that needed to meet customers where they lived and shopped.

Fountain Square: The Heart of Cincinnati

In 1969, Fifth Third doubled down on its identity with a new headquarters on Fountain Square. This wasn’t just prime real estate. Fountain Square had been Cincinnati’s civic center since the Tyler Davidson Fountain was installed in 1871. Putting the bank’s headquarters there was a visible, unmistakable claim: Fifth Third belonged at the center of the city.

It was also a counter-signal to the era. As businesses and families continued pushing outward to the suburbs, Fifth Third anchored itself downtown. The headquarters was a statement of permanence—of being woven into Cincinnati’s story, not simply operating near it.

The Holding Company Structure

By the mid-twentieth century, banking wasn’t just competitive—it was regulated within an inch of its life. Glass-Steagall separated commercial and investment banking. The McFadden Act constrained interstate branching. State rules layered on top of federal ones, creating a maze that shaped where banks could grow and what they could do.

In 1975, Fifth Third made a move that sounded like paperwork but would become strategy: it formed a bank holding company, Fifth Third Bancorp. That structure let the institution own multiple subsidiary banks and pursue certain non-banking activities permitted under the Bank Holding Company Act. Just as importantly, it helped Fifth Third navigate around some of the tightest state-level constraints.

In hindsight, it was a platform disguised as a legal form. When geographic restrictions loosened in the decades that followed, Fifth Third was ready to expand beyond Cincinnati through acquisitions across neighboring states. What looked like a technical restructuring in 1975 became the launchpad for the growth story of the 1980s and 1990s.

By the time Fifth Third reached the mid-1970s, the outlines of its playbook were already clear: stay rooted in Cincinnati and the Midwest, treat community engagement as part of the business—not a side project—keep experimenting with how banking is delivered, and position early for shifts in regulation. The next era would show just how powerful that combination could be.

IV. Innovation & Technology Leadership (1970s–1990s)

The Birth of Electronic Banking

By the 1970s, Fifth Third had built the legal and organizational platform to grow. The next question was what kind of bank it wanted to become. Across the industry, computers were creeping out of the back office and into the customer experience, and a few forward-looking institutions started to imagine something radical for the time: moving money electronically, without paper checks or a teller window.

Fifth Third leaned in early. In 1971, it formed Midwest Payment Solutions (MPS) to provide Electronic Funds Transfer services to other financial institutions. This wasn’t a glossy “innovation lab.” It was an infrastructure play—an early bet that payments processing would become a core utility of modern commerce. And if that future was coming, the smartest place to be was at the center of the network.

At the time, the market was barely there. Most people balanced checkbooks in paper ledgers. “Electronic banking” sounded like science fiction. But Fifth Third’s leadership saw what was hiding in plain sight: once money could move digitally, the institutions that processed those flows would be difficult to replace.

JEANIE: America's First Shared ATM Network

Then, in 1977, Fifth Third made its most famous early tech move: it launched JEANIE, the first online shared network of automated teller machines in the United States. JEANIE stood for “Joint Electronic Access Network: Interbank Exchange.”

That “shared” part mattered. ATMs existed in the late 1970s, but they were islands. A card from one bank often wouldn’t work at another bank’s machine. That limited the customer benefit and made ATMs harder to justify as a big capital investment.

JEANIE flipped the model. By connecting participating institutions into one interoperable network, it let customers withdraw cash and check balances at any JEANIE-enabled machine, not just their own bank’s. Each new member made the network more useful, which made it more attractive to the next member—a classic network effect, showing up years before most people had the language for it.

The shared-network approach JEANIE proved out became the template the industry would follow. For a regional bank in Cincinnati to help set the standard for how ATMs would work is one of the most underappreciated facts in Fifth Third’s history—and a clue that this bank’s ambition often ran ahead of its footprint.

Johnny Bench: Banking's First Sports Spokesperson

Fifth Third wasn’t only innovating in technology. It was also rethinking how a bank could show up in the life of its city.

In 1973, it signed Johnny Bench as a sponsor and spokesperson. Bench—the Hall of Fame catcher for the Cincinnati Reds—was already a superstar, with National League MVP awards in 1970 and 1972, and he would soon become a central figure in the “Big Red Machine” era that delivered World Series titles in 1975 and 1976.

Today, athletes sell everything. In the early 1970s, a bank doing it was unusual. Financial services marketing tended to be all marble columns and serious faces. Fifth Third chose the opposite: it borrowed the city’s most electric symbol and tied itself to the team Cincinnati loved.

It was a savvy regional banking move. Rates and basic products can look the same across competitors. Identity doesn’t. Fifth Third understood that in a city like Cincinnati, “feels like us” could be a real advantage.

Leadership Transitions and Cultural Evolution

The 1980s brought leadership shifts that shaped Fifth Third’s next phase.

In 1981, Clement L. Buenger took the helm and steered the bank through a punishing interest-rate environment. While the industry wrestled with volatility, Buenger kept Fifth Third oriented around disciplined lending and operational focus—less flash, more control.

Then, in 1989, George Schaefer Jr. became CEO at age 44. He would lead Fifth Third for the next eighteen years and define the bank’s reputation as an acquirer and integrator. The approach was simple, even blunt: buy banks, integrate fast, cut redundant costs, and use the improved efficiency to fund the next round of growth.

It wasn’t glamorous work. But it turned Fifth Third into a consolidation machine across the Midwest—and built a culture that paired ambition with a relentless emphasis on execution.

From MPS to Worldpay

Meanwhile, the payments bet Fifth Third placed back in 1971 kept compounding.

Midwest Payment Solutions evolved into Vantiv and, through later transactions, ultimately became part of Worldpay—one of the largest payment processing companies in the world. That arc is worth sitting with. What began as an early move into an “embryonic” business became exposure to a massive, durable industry once electronic payments turned into everyday life.

It also highlights another Fifth Third trait: the willingness to separate a good business from the right business. In 2009, Fifth Third completed the corporate spin-off of Fifth Third Processing Solutions, which was later acquired by Worldpay. Instead of clinging to a payments operation increasingly distinct from being a regional bank, Fifth Third monetized the asset and refocused on its core franchise.

Put it all together and the pattern is clear. Fifth Third wasn’t just adopting technology—it was using it as strategy: build networks early, make bets before they’re obvious, and stay disciplined enough to exit when the fit no longer makes sense. Those instincts would matter even more when the next great test arrived.

V. The 2008 Financial Crisis: Survival & TARP

Pre-Crisis Positioning

In the years leading up to 2008, Fifth Third was on a tear. Under George Schaefer’s acquisition-driven playbook, it stitched together banks across the Midwest and beyond, building a footprint that ran from Michigan down to Florida. It wasn’t just getting larger; it was pushing into more commercial lending and riding the broad optimism that defined mid-2000s banking.

And like just about everyone else, Fifth Third had a front-row seat to the housing boom. It had exposure through traditional mortgages and home equity lines of credit—products that looked safe as long as home prices kept floating higher and borrowers kept paying.

In hindsight, the clues were there. Home prices were outrunning what rents and incomes could justify. Underwriting standards had loosened. And the securitization machine that was supposed to spread risk across the system often did the opposite—moving it into structures few people truly understood. But before the fall, those warnings still felt theoretical to most of the industry.

The Crisis Hits

Lehman Brothers’ collapse in September 2008 turned a housing downturn into a full-blown panic. Credit markets seized up. Banks grew wary of lending to one another. Equity markets plunged. For a moment, it wasn’t clear the financial system would hold.

At Fifth Third, the crisis showed up in the place it always does for a lender: asset quality. Loans that looked fine in 2006 started cracking under stress. Commercial real estate weakened as property values fell and tenants struggled. Residential mortgages performed worse than models assumed they could. And like many banks, Fifth Third took mark-to-market hits in parts of its portfolio as prices reset in a hurry.

The most dangerous part wasn’t any single loss. It was the feedback loop. Losses led to higher reserves. Higher reserves spooked investors and counterparties. That fear made capital harder to raise and confidence harder to maintain—tightening the vise on the whole system. Breaking that loop required outside force.

TARP: The Treasury Intervenes

That force arrived through TARP. In November 2008, the U.S. Department of the Treasury invested $3.4 billion in Fifth Third under the Troubled Asset Relief Program. Like other recipients, Fifth Third took the capital in the form of preferred stock, which paid dividends to the government.

TARP was politically radioactive then, and it’s still debated now. Critics saw it as a bailout of bad behavior. Supporters argued it was triage: stabilize the banking system, keep credit flowing, and prevent a deeper collapse—and structure it as an investment rather than a blank check.

For Fifth Third, the practical effect was clear. The capital provided breathing room at the worst possible moment. It helped the bank keep lending to customers while it worked through problem loans. Without that cushion, Fifth Third could have been forced into a far sharper pullback—or faced heavier regulatory action.

Managing Through the Storm

Survival required choices no bank wants to make. Fifth Third cut its dividend, pushed hard on costs, and dealt with troubled credits one at a time. It also had to confront the uncomfortable internal question the crisis forced on every lender: how did risk pile up in places that looked safe until they suddenly weren’t?

Credit losses kept coming through 2009 and 2010 as boom-era loans deteriorated. Fifth Third responded by building loan-loss reserves and taking the earnings hit that came with it. It was painful, but it moved the problems from “maybe later” to “right now.” Banks that postponed recognition often ended up living with the damage for much longer.

TARP Repayment and Recovery

In February 2011, Fifth Third repurchased the Treasury’s TARP investment. Symbolically, it was a line in the sand: the bank had made it through and was healthy enough to stand without government capital.

The repayment also mattered for the broader TARP argument. The Treasury earned a positive return on its Fifth Third position, reinforcing the case that, at least in this instance, the program functioned as an investment designed to stabilize the system—not simply a transfer.

Coming out the other side, Fifth Third’s posture changed. It pulled back from more volatile activities, strengthened capital beyond bare minimums, and emphasized relationship-based commercial and retail banking. The era of expansion at any cost was over; resilience became part of the strategy.

Lessons Learned

The crisis left scars—and a playbook. Concentration risk matters, whether it’s geography, industry exposure, or a seemingly “safe” product that turns correlated in a downturn. Capital matters even more; in a panic, the banks with real buffers have options, and the ones without them don’t. And government and regulatory relationships matter too, however uneasy that truth may feel—when the system is on fire, credibility can shape outcomes.

For anyone looking at Fifth Third today, 2008 is the key context. The bank that emerged is more conservative, more deliberate about risk, and more focused on durability. Whether that’s a competitive advantage or a constraint depends on what you think the next cycle will demand.

VI. The MB Financial Acquisition: Chicago Ambitions (2018–2019)

A Decade of Recovery and Rebuilding

By 2018, ten years had passed since the financial crisis turned banking into survival mode. Fifth Third had rebuilt its capital, returned to profitability, and regained the confidence to do what it historically did best: grow through acquisition. The post-crisis rulebook had also settled in. Dodd-Frank wasn’t new anymore—it was simply the environment banks operated in.

But the industry had changed. The biggest banks came out of 2008 with even more share, even more scale, and technology budgets that could swallow a regional bank’s entire expense base. For Fifth Third, the question wasn’t whether it could keep competing in the Midwest. It was whether it could stay relevant as banking became more digital, more winner-take-most, and more dominated by giants.

Its answer was to stay true to its Midwestern roots—and make a decisive move into the Midwest’s biggest prize: Chicago.

MB Financial: A Chicago Institution

MB Financial Inc. was a Chicago-based bank holding company with deep ties in the city’s commercial banking scene. With around $20 billion in assets and a strong position in middle-market commercial lending, it looked like the kind of franchise Fifth Third prized: relationship-driven, locally embedded, and built around customers who weren’t looking for Wall Street—they were looking for a bank that understood how business actually gets done.

MB Financial’s sweet spot was Chicago’s entrepreneurs and privately held companies—too big for community banks, often overlooked by the money-center behemoths. Those relationships tended to last, and they tended to produce steady fee income that could help smooth out the ups and downs of a credit cycle.

Just as important, MB Financial offered something Fifth Third didn’t have: real scale in Chicago. Fifth Third had a Midwestern footprint, but it had never been a top-tier player in the nation’s third-largest metro area. This deal wasn’t incremental. It was a step-change.

The Deal Announcement

On May 21, 2018, MB Financial and Fifth Third announced a definitive merger agreement valued at about $4.7 billion. MB Financial shareholders would receive $54.20 per share in total consideration, made up of 1.45 shares of Fifth Third stock plus $5.54 in cash.

The logic was straightforward: buy a meaningful seat at the table in Chicago rather than trying to earn it branch by branch over decades. The combined bank would become the fourth-largest by total deposits in the Chicago metro area, with a 6.5 percent market share. Even more telling was the middle-market angle, where the combined institution would have a 20 percent share in commercial relationships.

For Fifth Third, it was a transformational bet. The price wasn’t trivial, but neither was the opportunity. Chicago wasn’t just another market—it was the market.

Integration Challenges

The acquisition closed in March 2019. And then the real work began.

Bank integrations are famously unforgiving. You can get the strategy right and still destroy value through systems problems, botched customer communication, or cultural misalignment. Fifth Third knew this better than most—its history was built on acquisitions, and that experience came with scar tissue.

So it approached the integration the way seasoned acquirers do: plan the systems conversion carefully, identify branch overlaps early, communicate relentlessly, and focus on the one thing that truly matters—keeping the relationships that made the deal worth doing in the first place.

A key signal of that priority was leadership. Mitch Feiger, MB Financial’s president and CEO, became CEO of the Chicago region for the combined bank. Rather than trying to run Chicago from Cincinnati, Fifth Third kept local leadership in place—an acknowledgement that in relationship banking, credibility is earned on the ground.

Synergies and Scale Benefits

The expected cost benefits came through largely as planned: duplicated functions were removed, technology platforms were consolidated, and overlapping branches were rationalized. By 2020, Fifth Third said it was achieving run-rate expense savings consistent with what it had projected.

But the bigger payoff was strategic, not cosmetic. Fifth Third now owned a Chicago franchise with bankers who already knew the city’s decision-makers—and credit teams who understood local industries. That isn’t something you can will into existence. You either build it over a generation or you acquire it in one swing.

And Chicago gave Fifth Third something else: diversification within a single metro. Manufacturing, logistics, financial services, technology, healthcare—one market, many engines. That breadth created more ways to grow without tying the bank’s fate to one sector or one local cycle. It also made Fifth Third’s position harder for rivals to copy quickly. Once you’ve established a real beachhead, everyone else has to pay up—or start from scratch.

The Shareholder Litigation

Not everyone celebrated the deal. Some MB Financial shareholders filed a class action lawsuit claiming the merger consideration was inadequate and alleging breaches of fiduciary duty by the board. The case lingered for years before settling in September 2023 for $5.5 million—small relative to the transaction, but a reminder that large acquisitions don’t just carry financial and operational risk. They also carry legal and governance scrutiny.

The settlement didn’t indicate a fundamental flaw in the deal, but it underscored a basic truth about M&A: even when you’re right, you still have to prove you were careful.

For investors, the MB Financial acquisition became a marker. It showed Fifth Third was willing to make a bold, market-defining move—and that it believed it could execute the kind of complex integration that separates the serial acquirers from the one-and-done hopefuls. Chicago didn’t become a core market overnight, but after MB Financial, Fifth Third finally had the foundation to make it one.

VII. Modern Era: Digital Transformation & Growth (2019–Today)

The Post-MB Integration World

After the MB Financial deal closed, Fifth Third entered a new phase that was less about bold announcements and more about hard, unglamorous execution. The bank had two jobs: finish turning MB into “one Fifth Third” in Chicago, and keep modernizing how customers actually banked.

Then, in early 2020, COVID-19 hit and turned that modernization from a strategy into a necessity. Branch lobbies emptied. People who liked face-to-face banking suddenly couldn’t, or didn’t want to. Mobile deposits, online bill pay, and digital account opening stopped being “nice to have” and became the default.

For Fifth Third, the advantage was timing. It had been investing in technology for years, and in the pandemic pressure test, that work showed up where it mattered: the mobile app handled the surge in activity, service teams shifted to remote work, and the core operations of the bank kept running through a period that broke a lot of assumptions across the industry.

The Dividend Finance Acquisition

In May 2022, Fifth Third acquired Dividend Finance, a San Francisco-based residential solar power lender. On paper, it looked like a left turn for a Midwestern regional bank. In context, it was Fifth Third doing what it has often done at its best: buying its way into a capability and a growth lane instead of trying to build it slowly from scratch.

Dividend Finance focused on point-of-sale financing for residential solar installations—loans that help homeowners cover the upfront cost of solar panels and then repay over time. The business sat at the crossroads of consumer demand for renewable energy and the incentives pushing solar adoption forward.

For Fifth Third, the appeal was simple: a faster way into a growing market segment, with a platform and expertise already in place.

2023: Rize Money and Big Data Healthcare

In 2023, Fifth Third kept going, acquiring Rize Money and Big Data Healthcare. The common thread wasn’t geography. It was capability.

Rize Money brought embedded banking—tools that let financial features live inside non-financial products. In practice, that could look like a healthcare software platform offering financing options directly inside its workflow, rather than sending customers off to a separate bank portal.

Big Data Healthcare added specialized healthcare expertise, particularly around receivables and revenue cycle management.

Taken together, the message was clear: Fifth Third was increasingly treating banking not just as a destination customers visit, but as infrastructure that can be woven into how other industries operate.

Digital Banking Excellence

Those investments in digital experience added up. In 2025, Fifth Third was ranked as offering the best mobile banking app experience in a J.D. Power survey. In retail banking, that kind of recognition isn’t just a trophy—it’s positioning. As more customers live inside their banking app, the quality of that experience becomes a real competitive moat. People don’t switch banks casually, but they will switch when the digital experience becomes a recurring frustration.

The ranking reflected years of work on usability, reliability, and features customers actually use—mobile deposit, bill pay, transfers—alongside tools that go a step further, like budgeting and personalized insights.

Current Market Position

By the fourth quarter of 2023, Fifth Third had about $205.6 billion in assets and roughly 19,500 employees. It operated across eleven states, with strength in Ohio and Michigan, a meaningfully upgraded position in Illinois after MB, and a footprint that extended into Florida and the broader Southeast.

This version of Fifth Third didn’t look like the bank that entered the 2010s. Chicago had become a major engine. The digital front door had been modernized. And the acquisition strategy had widened—from classic bank consolidation to fintech and specialty finance.

ESG and Community Commitment

At the same time, Fifth Third leaned harder into environmental, social, and governance priorities—financing renewable energy, supporting affordable housing, and expanding economic opportunity in underserved communities.

Some of that is values and legacy. The Fifth Third Foundation dates back to 1948, and the bank has long treated community investment as part of its identity. But it’s also the modern reality: ESG priorities increasingly shape how customers choose brands, how employees choose employers, and how regulators and investors evaluate institutions.

From an investor’s perspective, the modern era is Fifth Third trying to compound three bets at once: a scaled-up Chicago franchise, a bank that can compete on digital experience, and targeted moves into specialty businesses like solar lending and embedded finance. The open question is the one that always matters in banking: will those bets translate into durable, risk-adjusted returns that justify what the market is willing to pay?

VIII. Challenges & Controversies

The Auto Lending Discrimination Settlement

In 2015, Fifth Third agreed to pay $18 million to settle allegations of discrimination in indirect auto lending. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Department of Justice said the bank’s pricing policies in dealer-arranged financing resulted in African-American and Hispanic borrowers paying higher interest rates than similarly qualified white borrowers.

The allegation wasn’t that Fifth Third employees were explicitly choosing to discriminate. The problem was structural. In an indirect model, the dealer originates the relationship, the bank provides the funding, and pricing often includes room for discretion. Fifth Third allowed dealers to mark up the interest rate above the bank’s “buy rate,” and regulators’ statistical analysis found those markups landed more heavily on minority borrowers.

Fifth Third resolved the case without admitting wrongdoing. It also agreed to rein in dealer markup discretion going forward. The episode became a clean illustration of a broader banking lesson: when you outsource part of the customer interaction, you can also outsource risk—especially when incentives and discretion are involved.

The Cross-Selling Scandal

After Wells Fargo’s unauthorized-account scandal blew up in the 2010s, regulators didn’t just focus on one bank. They started pulling on the thread across the industry: how were sales targets set, what behaviors did incentives encourage, and what controls actually stopped bad outcomes?

In 2020, the CFPB charged Fifth Third with illegal cross-selling, alleging employees opened deposit accounts, lines of credit, and credit cards without proper customer authorization. The bureau argued that Fifth Third’s incentive programs created pressure that contributed to the misconduct.

Fifth Third disputed the allegations, but in 2024 it resolved the matter with a $20 million payment. The settlement closed the loop legally, but it left a mark reputationally—and reinforced the uncomfortable truth that sales culture in banking is not a “soft” issue. Incentives are product design. If they’re wrong, the outcomes can be very real.

MB Financial Shareholder Litigation

The MB Financial deal also carried a familiar M&A aftershock: shareholder lawsuits. Some MB Financial shareholders claimed the merger consideration was inadequate and alleged breaches of fiduciary duty. The class action ultimately settled in September 2023 for $5.5 million.

The dollars were small relative to the size of the transaction. The drag wasn’t. Litigation like this lingers, pulls at management attention, and adds friction to a deal long after the integration work is supposedly finished.

Managing Reputation and Rebuilding Trust

None of these issues are unique to Fifth Third. Large banks live under constant scrutiny—by regulators, by plaintiffs’ attorneys, and by customers who tend to trust banks right up until they don’t. What separates institutions isn’t whether problems ever appear. It’s whether the response is superficial or structural.

Fifth Third said it took steps to address the underlying drivers: reforming sales practices, enhancing fair-lending monitoring, and strengthening compliance. For investors, the question isn’t whether those actions look good in a press release. It’s whether they hold up over time—through leadership changes, through the next growth push, and through the inevitable temptation to prioritize revenue over process.

Current Regulatory Environment

The operating environment for regional banks remains intense. Since the financial crisis, capital expectations have risen, stress testing has become routine, and consumer protection enforcement has stayed active. Then the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in 2023 reset the conversation again—bringing renewed attention to interest-rate risk and deposit concentration.

Fifth Third moved through the 2023 turbulence without major disruption, but the episode was a reminder of how quickly the rules and the spotlight can change. Bank regulation isn’t a fixed backdrop. It’s a moving force that shifts when something breaks.

For anyone evaluating Fifth Third, these controversies are part of the mosaic. The bank has shown it can absorb regulatory hits without existential damage, but it hasn’t been spotless. In banking, that record matters—not because mistakes are rare, but because the compounding effect of trust, controls, and culture is often the difference between a temporary problem and a lasting one.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investment Lessons

The Power of Regional Banking Consolidation

If you zoom out across Fifth Third’s history, the pattern is unmistakable: this is a bank built by combining. For more than a century, it grew less by planting flags one branch at a time and more by absorbing existing franchises—each one bringing customer relationships, local knowledge, and a physical footprint that would have taken years to replicate organically.

The business lesson is simple: in modern banking, scale isn’t vanity. It’s survival. Technology spend, fraud prevention, cybersecurity, product development, and compliance aren’t optional—and the bigger you are, the more you can spread those fixed costs across a wider base. Banks that never reach meaningful scale can end up stuck in an uncomfortable middle: too small to be efficient, too big to win purely on “we’re your local bank.”

Fifth Third also highlights the underappreciated part of consolidation: integration is the real product. Deals are easy to announce and hard to make work. Cultures collide, systems conversions go sideways, customers get spooked, and key bankers can walk. Fifth Third’s edge has been repetition. After doing this over and over, integration became a core competency—not a one-time project plan.

Surviving Financial Crises: Capital and Government Relations

The 2008 crisis is the reminder every bank eventually gets, whether it wants it or not: capital that looks “fine” in a calm market can be nowhere near enough in a panic. Fifth Third ultimately needed TARP, which is another way of saying the stress exceeded what its balance sheet could comfortably absorb on its own.

There’s a second lesson here that’s less discussed but just as real. In a systemic crisis, government and regulators aren’t external observers—they become central actors. Access to programs like TARP, and the credibility to navigate the regulatory response, can shape whether a bank stabilizes, is forced into drastic actions, or loses market confidence at the worst possible time.

For investors, the takeaway is to treat capital strength as a cushion, not a checkbox. Regulatory minimums are not a guarantee. They’re a floor, and crises have a way of dropping straight through floors.

Technology as a Differentiator

Fifth Third’s history is a good rebuttal to the idea that only the biggest banks can lead on technology. Building Midwest Payment Solutions in the early days of electronic funds transfer, and launching the JEANIE shared ATM network, weren’t cosmetic upgrades. They were strategic bets on infrastructure—on being part of the rails money would ride on.

The specific frontier changes with each era. Today it might be embedded finance, smarter underwriting via data, or a digital experience good enough that customers stop thinking about their bank at all. But the principle holds: banks that invest early in real capabilities don’t just get features. They get options—and options compound.

M&A Execution: Timing, Integration, and Value Creation

The MB Financial acquisition is a modern case study in what “transformational” M&A actually means. Fifth Third didn’t buy MB to shave a little cost or fill in a few dots on a map. It paid up to buy a seat in Chicago—one of the few U.S. markets big enough to move the needle for a regional bank.

But paying up is the easy part. Whether a premium is smart or reckless comes down to execution: keep the relationships, retain the talent, integrate systems without breaking service, and actually deliver the cost and revenue benefits you promised.

The broader lesson is that M&A isn’t just strategy—it’s a muscle. Banks that have proven they can integrate have access to moves that are effectively off-limits to everyone else. Fifth Third’s long history of acquisitions isn’t just a record of growth; it’s an asset that can enable the next deal.

Building Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Banking is a tough place to build a moat because the core product—money—looks the same everywhere. Fifth Third’s advantages tend to be quiet ones: density in key Midwestern markets, long-standing commercial relationships, and accumulated knowledge of local industries and credit behavior.

They matter, but none of them are permanent. A larger competitor with a lower cost of funds can underprice you. A fintech can out-design you. A bad credit cycle can undo years of careful relationship-building. The job is never “win once.” The job is keep reinvesting so the franchise stays relevant—and resilient.

Corporate Culture in Banking

Finally, Fifth Third’s story makes a case that culture isn’t soft—especially in a business built on trust and judgment. The bank’s long-running community orientation, formalized early through its foundation and reinforced over decades, isn’t just good citizenship. It can translate into stronger employee commitment, deeper customer loyalty, and a more durable local brand.

And because banking is a business of daily decisions—how aggressively you lend, how you treat customers, what incentives you set—culture shows up in outcomes. Over long periods, the banks with aligned incentives and a clear sense of responsibility tend to make better average decisions than the ones that optimize for the next quarter and hope controls catch the rest.

X. Analysis: Bear vs. Bull Case

Competitive Positioning

Fifth Third sits in an awkward but familiar spot in American banking: too big to win purely on “we know everyone in town,” and too small to throw its weight around like the money-center giants. It can’t outspend JPMorgan Chase on technology or marketing, and it can’t out-local the best community banks everywhere it operates.

The bull case is that Fifth Third has carved out real density in the Midwest, and density is where regional banks earn their keep. In markets like Cincinnati, Chicago, and Columbus, the bank has relationships that took decades to build—especially on the commercial side, where winning a client isn’t just about price, it’s about trust, credit judgment, and being useful in good times and bad. Layer on the bank’s long-running tech investments, and bulls see a franchise that can feel “big enough” digitally while still competing like a relationship bank.

The bear case is that this middle position can become a squeeze. Fifth Third may not have the scale to compete on cost of funds, product breadth, and sheer engineering horsepower with the biggest banks. At the same time, it can look slow and regulated compared with the best fintechs, which can pick off profitable product lines—payments, consumer lending, wealth tools—without carrying the full burden of a traditional bank.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Michael Porter’s framework helps explain why this business can feel structurally hard, even when it’s well run:

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate. A full bank charter is difficult and heavily regulated, which protects incumbents. But fintechs don’t need to become banks to compete; they can enter through individual products like payments or lending.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low. Banks fund themselves through deposits and wholesale markets, and there are many sources of funding. Fifth Third has enough scale to access those markets efficiently.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate to high. Commercial customers can shop terms and negotiate, especially when credit is plentiful. Retail customers can switch more easily than they used to, because digital account opening and online alternatives have reduced friction.

Threat of Substitutes: Rising. Fintech products can replace parts of the traditional bank relationship, and embedded finance can make the “bank” invisible by placing financial services inside other software and platforms.

Rivalry Among Existing Competitors: Intense. Banking is crowded, mature, and highly competitive. When deposits get expensive or loan demand softens, competition tends to show up in pricing—and that pressure flows straight into margins.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Framework

Helmer’s Seven Powers asks a different question: what, if anything, can compound into durable advantage?

Scale Economies: Meaningful. Fifth Third can support technology and compliance investments that smaller institutions struggle to afford.

Network Effects: Limited today. JEANIE had real network effects in its era, but Fifth Third’s modern core banking business doesn’t enjoy the same structural flywheel.

Counter-Positioning: Not really. Fifth Third’s model is well understood, and competitors can pursue similar strategies.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Commercial relationships can be sticky because moving loans, treasury management, and operating accounts is disruptive. Retail relationships are easier to move, especially if the primary relationship is just “who has the best app and the best rates.”

Branding: Modest. Fifth Third is well known in its footprint, but it doesn’t have the national brand gravity of the largest banks.

Cornered Resource: Not evident. It doesn’t have unique, exclusive access to talent, technology, or distribution.

Process Power: Plausible. Fifth Third’s long history of acquisition integration and cost discipline may be a real advantage—hard to see from the outside, but valuable if it consistently produces better execution than peers.

Netting it out: Fifth Third’s advantages look real, but not overwhelming. It can have a moat in the places where it has density and relationships, yet that moat is narrow enough that execution and cycle management matter a lot.

Interest Rate Sensitivity

Like every traditional bank, Fifth Third lives and dies by rates. When rates rise, banks often earn more on loans than they pay on deposits—at least at first—so net interest margin tends to expand. When rates fall, that spread usually compresses.

The rate shock of 2022–2023 was a reminder that higher rates aren’t a free lunch. They can help asset yields, but they also intensify competition for deposits as customers demand more yield or move money elsewhere. Managing that tradeoff—especially the timing mismatch between assets and liabilities—is a constant, high-stakes job.

Credit Quality Considerations

Credit is where bank stories go from “steady” to “suddenly not.” One area investors watch closely is commercial real estate, particularly office exposure, given the uncertainty around demand in a post-pandemic world. Fifth Third has historically managed credit well, but this environment is unusual enough that it deserves extra attention. Changes in charge-offs or reserve building can be early signals that stress is spreading.

Key KPIs to Track

If you only watched two numbers to understand the health of the core banking engine, it would be these:

Net Interest Margin (NIM): The spread between interest earned and interest paid. NIM tells you, in one line, how well Fifth Third is navigating rates, deposit competition, and balance-sheet positioning.

Efficiency Ratio: Non-interest expense divided by revenue. It’s the clearest read on whether the bank is running a tight ship or letting complexity and competition erode profitability.

Together, NIM and the efficiency ratio capture the basic bargain of regional banking: earn a healthy spread, don’t give it back in costs.

XI. Epilogue & Future Outlook

The Future of Regional Banking Consolidation

If Fifth Third’s first century was a story of merger and integration, the next decade is likely to be more of the same—just with higher stakes. Compliance keeps getting more expensive. Cybersecurity and fraud prevention are now table stakes. And the digital experience customers expect doesn’t come cheap. In that world, scale isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s how you pay for the fixed costs of staying in the game.

The industry math points in one direction. The number of FDIC-insured banks has dropped from more than 14,000 in 1985 to fewer than 5,000 today. There’s no reason to think that trend is finished.

That leaves Fifth Third in an interesting spot. It’s big enough to be an acquirer that can actually move the needle, but not so big that it’s immune from being looked at as a target by a larger competitor. Whether it keeps shaping consolidation—or gets shaped by it—will matter as much as any quarterly result.

Technology Disruption and Embedded Finance

The next threat to the traditional regional bank isn’t necessarily another bank. It’s the possibility that the “bank” becomes invisible.

Embedded finance is the clearest example: lending offered inside a software product, payments living inside a retailer’s app, accounts opened without a customer ever thinking, “I should go choose a bank.” When financial services show up as a feature instead of a destination, the standalone banking relationship can lose its gravity.

Fifth Third’s acquisitions like Rize Money point to one way to play offense here. Instead of trying to defend the old front door, become part of the plumbing—power the embedded experiences rather than watching them siphon value away. If that works, Fifth Third doesn’t have to win every customer directly. It can win by being the bank behind the scenes.

Climate Finance and ESG Mandates

The shift toward a lower-carbon economy is also, quietly, a financing story. Renewable energy, efficiency upgrades, and new infrastructure all require capital—and banks that build real expertise in funding that transition can find meaningful growth.

Fifth Third’s 2022 acquisition of Dividend Finance gave it a platform in residential solar lending. That’s a start, but it’s not the whole opportunity. The bigger question is whether Fifth Third can turn that foothold into broader capabilities as climate-related investment becomes a more durable, mainstream category of bank financing.

Competitive Threats from Big Tech and Neobanks

Big Tech has been circling finance for years. Apple, Google, and Amazon each have the distribution, the data, and the product design muscle to make financial services feel effortless. And neobanks like Chime and SoFi have shown just how fast a digital-first brand can attract customers when the experience is simpler and the marketing is sharper.

Fifth Third can’t outspend those companies on product engineering. It can’t win by trying to become Apple. Its counterpunch has to be the things those competitors struggle to replicate: deep commercial banking relationships, local market density, and the kind of institutional credibility that matters when the economy turns and risk suddenly stops being theoretical.

In other words, Fifth Third’s job isn’t to win a pure tech arms race. It’s to combine a strong digital experience with the relationship and credit capabilities that still define the hard part of banking.

What Would Success Look Like in 2030?

A Fifth Third that’s winning in 2030 likely looks like this: Chicago is not just a presence but a true core market. Specialty finance platforms like solar lending have expanded into meaningful, well-managed businesses. The bank stays efficient enough to keep investing, even when competition forces pricing tighter. And through whatever rate and credit cycles show up between now and then, it proves it can protect asset quality without giving up growth.

That’s the vision. The real question—investors’ question—is whether Fifth Third has the leadership, culture, and positioning to pull it off, or whether the structural pressures on regional banking will compress the middle until only the biggest players and the most focused niche banks thrive.

XII. Recent News

[Section reserved for recent developments and news updates]

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings and Primary Sources

- Fifth Third Bancorp Annual Reports (Form 10-K)

- Fifth Third Bancorp Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q)

- Fifth Third Bancorp Proxy Statements (DEF 14A)

- SEC EDGAR company filings (CIK 0000035527): https://www.sec.gov/cgi-bin/browse-edgar?action=getcompany&CIK=0000035527

Additional Reading

- The Cincinnati Wing: A History of Fifth Third Bank (Fifth Third corporate archives)

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau enforcement documents

- Federal Reserve resources on bank holding company supervision

- FDIC historical banking statistics

Industry Resources

- American Bankers Association publications

- Federal Reserve economic research

- FDIC Quarterly Banking Profile

- S&P Global Market Intelligence banking analysis

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music