Gilead Sciences: The Antiviral Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

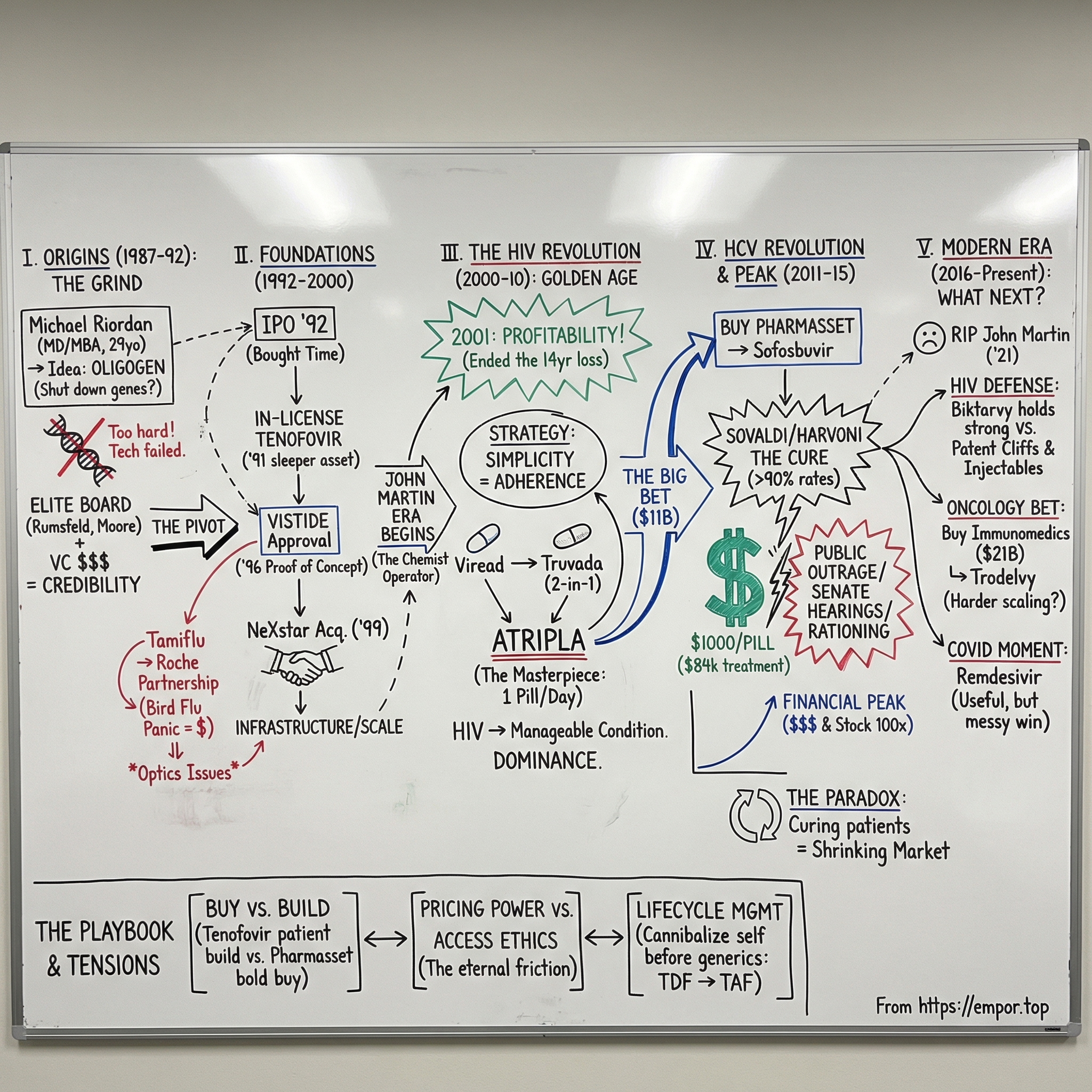

In the biotech belt of the San Francisco Bay Area, where Stanford’s labs feed discoveries into the venture machine of Sand Hill Road, there’s a company in Foster City that has shaped modern medicine more than most people realize. Gilead Sciences built its name—and its fortune—by taking on some of humanity’s most relentless viral threats: HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, influenza, and, most recently, COVID-19.

The question at the heart of this story is simple, and it’s wild: how did a startup founded by a 29-year-old doctor grow into the most valuable pure-play biotech in history? How did a company spend fourteen years grinding along before posting its first profit, and then turn around and pull in tens of billions from a single breakthrough?

Because Gilead isn’t just a success story. It’s a story with sharp edges.

It’s radical science and ruthless execution. It’s brilliant deal-making—and years of decisions that sparked public outrage. It’s a company that helped transform HIV from a death sentence into a manageable chronic condition. It’s also the company that brought a true cure for hepatitis C to market, then launched it at $84,000 for a standard course of treatment and ignited a pricing firestorm that reached Congress.

And the characters feel almost too on-the-nose for a business saga: Donald Rumsfeld in the boardroom as chairman during the Tamiflu era; a CEO who compounded the company’s value roughly 100-fold over two decades; and a final chapter marked by tragedy when that same CEO, John C. Martin, died in 2021 after suffering head injuries from a fall.

Threading through all of it is the central conflict of modern pharma: the collision between innovation and access. What is a cure worth? Who gets it first—and who gets told to wait? Can a company be both enormously profitable and a genuine force for good?

Here’s the roadmap. We’ll start with Gilead’s unlikely origins as a small oligonucleotide startup in the late 1980s. Then we’ll follow the pivot that created an HIV powerhouse in the 2000s, the hepatitis C acquisition that reset the entire biotech M&A market, and the pandemic moment that put Gilead back on the front page. Along the way, we’ll pull out the underlying playbook—how this company built its antiviral platform, how it chose when to build versus buy, and why its biggest wins inevitably came with the biggest controversies.

II. Origins: From Oligogen to Gilead (1987–1992)

In the summer of 1987, a 29-year-old physician named Michael L. Riordan sat in a cramped office in Foster City, California, mapping out an audacious plan. He’d just incorporated a company called Oligogen—a name that wouldn’t last, but an idea that might.

Riordan didn’t look like the stereotypical biotech founder, at least not the scrappy kind. His background was pure institutional elite: Washington University in St. Louis for undergrad, a medical degree from Johns Hopkins, then an MBA from Harvard Business School. He could speak the language of molecular biology and the language of capital. What he didn’t have yet was the hard-earned scar tissue of building and running a company.

The premise was bold for the late 1980s. Riordan believed oligonucleotides—short, synthetic strands of DNA—could be engineered to bind to specific genetic sequences and shut them down. In theory, you wouldn’t have to blast the body with blunt-force drugs. You could aim directly at the mechanism of disease, gene by gene, virus by virus. It was a beautiful idea. It was also an idea that, in practice, would fight back.

Before any of that mattered, he needed a better name. “Oligogen” sounded like a lab reagent. Riordan wanted something that suggested healing—something older than biotechnology, but compatible with it. He landed on “Gilead,” inspired by the Balm of Gilead from the Book of Jeremiah, a legendary remedy. The name also nodded to the natural aspirin-like compounds found in willow trees, one of the earliest examples of medicine pulled straight from nature. Gilead Sciences, then, was meant to sit at the intersection of ancient cures and modern molecular design.

For a company with no products and an unproven platform, what Riordan built next was almost unbelievable: credibility. He assembled a scientific advisory board that read like a roll call of the era’s most respected biologists. Peter Dervan at Caltech, known for pioneering work on DNA-binding molecules. Doug Melton at Harvard, who would later become a star in stem cell science. Harold Weintraub at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, a giant in gene regulation. And then two Nobel-caliber names: Harold Varmus and Jack Szostak. For a brand-new startup, this wasn’t just impressive. It was a signal flare that the underlying ambition had serious people leaning in.

Money arrived behind the talent. Menlo Ventures led an initial $2 million investment—small by today’s standards, but meaningful in 1987, when biotech venture investing was still closer to an experiment than an asset class. Most companies in this category never made it to a first product, let alone meaningful revenue.

Then came the board—appointments that, in hindsight, tell you what kind of company Gilead was trying to become. In 1988, Donald Rumsfeld joined the board of directors. This was Rumsfeld between his stints as Secretary of Defense: after Ford, before George W. Bush. He’d also been CEO of G.D. Searle, so he understood drug development—and the political and commercial realities that come with it. He was followed by Benno C. Schmidt, Gordon Moore of Intel, and George Shultz, Reagan’s Secretary of State. This wasn’t a typical biotech board stacked with scientists and financiers. It was a board built to deal with regulators, governments, and global-scale consequences.

The early years, though, were dominated by the part of biotech that doesn’t make for clean pitch decks: the grind. The oligonucleotide strategy that sounded so elegant kept running into ugly constraints. The molecules could be hard to manufacture, hard to deliver into cells, and prone to breaking down before they ever hit their targets. Riordan later said Gilead’s first decade was “extremely stressful”—a calm phrase for years of technical setbacks, fundraising pressure, and the constant possibility that the whole thing would simply run out of runway.

What kept Gilead alive wasn’t a sudden miracle. It was a pivot—one that would end up mattering far more than Oligogen ever did. Without giving up on antivirals, the company began moving toward nucleotide and nucleoside analogs, a different chemical approach aimed at interrupting viral replication. That shift would quietly set the foundation for everything Gilead became.

III. Going Public & First Products (1992–2000)

By 1992, Gilead had survived long enough to do the thing every venture-backed biotech dreams about: go public. But this wasn’t some victory lap. The company still had no approved products, no reliable revenue engine, and a long list of scientific problems left to solve. The IPO mattered for a simpler reason: it bought time. It put real capital in the bank, and it stamped Gilead as a credible, permanent-looking institution in the biotech ecosystem—one that could recruit, partner, and bargain without sounding like a science project.

A year earlier, Gilead had made a move that would eventually define the company. In 1991, it in-licensed a nucleotide analog called tenofovir. At the time, it looked like one promising compound among many. HIV treatment was still rough. AZT had been approved in 1987, but resistance was rampant, and the idea of durable, modern combination therapy hadn’t yet reshaped care. There was no guarantee tenofovir would be anything special—let alone the backbone of a franchise.

Gilead’s first FDA approval finally arrived in June 1996: Vistide, or cidofovir. It treated cytomegalovirus retinitis, a brutal infection that could steal the sight of AIDS patients. It wasn’t a blockbuster; the population was too small. But inside the company, it was a turning point. Vistide proved Gilead could translate real science into a real drug—and that it could navigate regulators, set up manufacturing, and build the beginnings of a commercial operation. Those muscles would matter far more when the bigger moment came.

That same year, Riordan handed over the CEO job. He’d gotten Gilead through the precarious early decade and to its first approval, but he also recognized the next chapter would demand a different kind of operator—someone who could build not just a lab, but a pharmaceutical company. The role went to John C. Martin, who had joined in 1990 as VP of R&D. Martin was deeply technical—a PhD organic chemist with serious antiviral chops—but he also had the instincts to take a pipeline and turn it into a machine. With him, Gilead began to look less like a research outfit and more like an integrated drug developer.

In January 1997, Donald Rumsfeld stepped up as chairman of the board. He brought pharmaceutical experience and a Washington operator’s feel for how power actually works. That would help in the years ahead—and it would also ensure that Gilead’s successes, when they came, wouldn’t just be judged in the clinic or on Wall Street. They’d be judged in the court of public opinion, too.

Then came the deal that would hang around the story for years: Tamiflu. Gilead scientists had discovered oseltamivir, a compound with strong activity against influenza. But commercializing a flu drug is a strange business. Demand can be unpredictable—until suddenly it isn’t, and the whole world wants supply at once. Gilead didn’t have the manufacturing scale or global distribution to play that game, so it partnered with Roche. Roche would take on late-stage development, manufacturing, and marketing. Gilead would collect royalties. It was a pragmatic choice that would later become very visible during flu scares.

In 1999, Gilead made its biggest swing of the decade: it acquired NeXstar Pharmaceuticals. NeXstar was already doing meaningful business—about $130 million in annual sales, roughly three times Gilead’s at the time. The point wasn’t just revenue. It was infrastructure: commercial capabilities, additional products, and operational scale. The message was clear. Gilead wasn’t content to be a clever R&D shop living deal to deal. It was assembling the pieces to compete like a real pharma company.

As the 1990s closed, Gilead still wasn’t profitable. But it was no longer fragile. Tenofovir was moving through clinical trials. The HIV epidemic remained a global catastrophe, with tens of millions infected worldwide. And the combination-therapy era—multiple drugs used together to suppress the virus over the long term—was taking hold. That shift was about to create massive demand for exactly the kind of antiviral platform Gilead had been quietly building.

IV. The HIV Revolution & Building the Platform (2000–2010)

In November 2001, everything snapped into focus. The FDA approved Viread—tenofovir in pill form—for HIV. It was the same compound Gilead had in-licensed a decade earlier, back when it was just one more long-shot asset on a thin pipeline. Now it was real. And it was about to become the backbone of an empire.

To see why Viread mattered, you have to remember what HIV treatment looked like in 2001. By then, the virus had killed more than 25 million people worldwide. Combination antiretroviral therapy worked, but it was demanding: lots of pills, strict schedules, and rules about food. The penalties for getting it wrong were brutal. Miss doses, and HIV could mutate around the drugs, burning through options and wiping out entire classes of therapy. The goal wasn’t just a new molecule. It was simplicity—regimens people could actually stick with.

Viread delivered on that promise. It was once daily, effective, and generally well-tolerated. Gilead had found a rare balance between potency and usability, and the market moved fast. By the end of 2001—just two months after approval—Gilead turned a corner it had been chasing since the late 1980s: profitability. After fourteen years of losses, it posted $52.3 million in net income on $233.8 million in revenue. For biotech founders, it was the classic lesson in both directions: the timeline can be punishingly long, and then success can arrive in a rush.

That same month, Donald Rumsfeld left Gilead’s board to become Secretary of Defense under George W. Bush. The timing was largely coincidental, but it would put Gilead in an uncomfortable spotlight. Rumsfeld kept his Gilead stock—and the company was about to get a lot more valuable.

The first surprise surge didn’t even come from HIV. It came from bird flu. In 2004, avian influenza spread across Asia, and public health officials warned the world could be staring down a pandemic. Tamiflu—the flu drug Gilead had discovered and licensed to Roche—was one of the few treatments believed to work. Governments began stockpiling. More than sixty countries placed large orders, and Gilead’s royalty revenue from Tamiflu nearly quadrupled to $44.6 million.

Rumsfeld benefited, too. He sold shares during this period and received more than $5 million in capital gains. Critics pounced on the optics: a sitting Secretary of Defense profiting during a public health panic that the U.S. government was taking seriously. Rumsfeld said he had recused himself from any decisions involving Tamiflu, and there was no evidence of wrongdoing. Still, it was an early preview of a theme that would follow Gilead for years: life-saving medicine, massive stakes, and an unavoidable collision between public policy and private profit.

Inside the company, John Martin kept building. The bet wasn’t just on individual drugs—it was on how people actually lived with HIV. If adherence determined outcomes, then making treatment easier wasn’t a nice-to-have; it was the product. Gilead’s strategy became fixed-dose combinations: fewer pills, fewer mistakes, better results.

In 2004, that thinking produced Truvada, which combined tenofovir with emtricitabine in a single pill. Two foundational drugs became one.

Then came the masterpiece. In 2006, Gilead launched Atripla, a once-daily pill that combined Truvada with Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Sustiva. It wasn’t just a convenience upgrade—it was a reframing of what HIV therapy could feel like. Where patients had once managed handfuls of pills across multiple manufacturers, now many could take one pill a day and maintain viral suppression. Atripla became the most widely prescribed antiretroviral treatment regimen in the United States.

By the end of the decade, the company had changed shape. This was no longer a biotech hoping its science would find a partner with distribution. Gilead now had the commercial engine, the manufacturing muscle, and the global reach to dominate markets on its own. The company that had once handed Tamiflu to Roche because it lacked scale had built the scale.

By 2010, Gilead was the defining force in HIV treatment, with revenue above $7 billion. And it had learned something that would become its signature: innovation wasn’t only about discovering powerful molecules. It was about packaging them into products that matched real life—how patients take medicine, how doctors prescribe it, and how health systems pay for it.

The playbook was working. The question was what Gilead would do with it next.

V. The Sovaldi/Harvoni Megadeal & HCV Revolution (2011–2015)

In November 2011, Gilead made a bet that, at the time, looked almost reckless: it paid about $11 billion to buy Pharmasset. Pharmasset had no approved drugs and essentially no product revenue. Gilead’s offer came in at an 89% premium, which made the deal feel less like an acquisition and more like a dare.

Wall Street’s immediate reaction was simple: what could possibly be worth that kind of money?

The answer was a molecule called sofosbuvir. And it would go down as one of the best acquisitions in modern pharma.

To understand why, you have to understand hepatitis C as it existed in 2011. An estimated 150 million people worldwide were infected. It was often a slow-moving disease, quietly damaging the liver for years, then suddenly turning into cirrhosis or liver cancer. The standard therapy was built around interferon injections—months of treatment that could make patients feel like they had the flu, trigger depression, and still fail. Cure rates hovered around 50% for the most common strains, and if you didn’t clear the virus, you were often right back where you started, with few good options.

Pharmasset’s sofosbuvir was different. It was a nucleotide analog that hit hepatitis C where it lived: viral replication. In early trials, the results were startling—cure rates above 90%, sometimes nearing 100%, with side effects patients could actually tolerate. Treatment that once dragged on for months suddenly looked like it could be measured in weeks. This wasn’t a “better” hepatitis C drug. It was the outline of a cure.

John Martin and the team at Gilead saw the possibility clearly. Yes, $11 billion was enormous. But if sofosbuvir held up, the market wasn’t small—it was global, and it was massive. The upside wasn’t a few good years of sales. It was the chance to rewrite the standard of care.

The regulatory path moved fast. Gilead filed the New Drug Application for sofosbuvir, in combination with ribavirin, in April 2013. In October, the FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation. And on December 6, 2013, the drug was approved under the name Sovaldi.

Then came the number that detonated everything else: $1,000 per pill. A standard course ran 84 days, so the sticker price landed at $84,000 per patient.

The industry had seen expensive medicines before, but usually in rare diseases where only a small number of people needed treatment. Hepatitis C wasn’t rare. It was millions of patients. High cost times huge population doesn’t just create a profitable product—it threatens to blow a hole in budgets.

Commercially, it was a phenomenon. In 2014, its first full year on the market, Sovaldi generated $10.3 billion in sales. And when you added Harvoni—the next-generation regimen that removed the need for ribavirin—Gilead’s hepatitis C franchise delivered $12.4 billion in 2014. Forbes called it “one of the best pharma acquisitions ever,” and it wasn’t exaggerating. In effect, the Pharmasset deal paid for itself in about a year.

Politically, it was a firestorm. The Senate Finance Committee opened an 18-month investigation into how Gilead set the price. Internal documents showed the company had debated prices from $50,000 to $115,000 per treatment course and explicitly weighed “predicted activist and public relations blowback.” In plain terms: Gilead expected the outrage, modeled it, and priced anyway.

The company’s argument was straightforward, if unsettling. Sovaldi didn’t just treat hepatitis C—it cured it. Compared with the old interferon-based regimen, it was far more effective and far less punishing. And unlike HIV therapies, which patients might take for life, hepatitis C drugs could be a one-and-done event. From that perspective, Gilead argued, the economics could make sense when you considered the downstream costs of unmanaged hepatitis C: liver failure, cancer, transplants.

Critics weren’t persuaded, because the crisis wasn’t theoretical—it was immediate. State Medicaid programs, in particular, faced impossible tradeoffs. In Oregon, treating just half of roughly 10,000 eligible patients would have more than doubled the state’s total drug expenditures. Across the country, many programs responded by rationing care—requiring advanced liver damage before approving treatment. The bitter irony was hard to miss: the patients who could most easily be cured early were often told to wait until they got sicker.

And there was another layer. Gilead understood competition was coming. High “Wave 1” pricing helped set the benchmark for the entire category. If Sovaldi anchored expectations at $84,000, then rival drugs could show up later, “discount” the price, and still charge sums that would have sounded absurd just a few years earlier.

This was the hepatitis C revolution in a nutshell: a genuine medical miracle, delivered through a business model that made access uneven by design. The science was beyond dispute. The value created for shareholders was enormous. For patients, the outcome depended on where you lived, what insurance you had, and whether the system could afford to cure you now—or only later, after the disease had done more damage.

VI. Peak Performance & The Martin Era (2014–2016)

The hepatitis C windfall didn’t just make Gilead successful. It pushed the company to a peak that almost no one in pharma ever reaches.

John C. Martin had been CEO since 1996, and over his tenure the stock rose roughly 100-fold. Then, in the two years surrounding the Sovaldi and Harvoni launches, the market went into overdrive: from 2013 to 2015, Gilead’s shares climbed 157%. Morningstar named Martin its best CEO of 2015, pointing to a feat that sounded almost made up—Sovaldi going from “zero-to-blockbuster in a couple of months,” with profits topping $10 billion in 2014.

Martin didn’t fit the usual archetype for a pharma kingmaker. He wasn’t a flamboyant deal hype-man, and he wasn’t a distant academic either. He was a chemist who could go deep on the molecules and an executive who understood exactly how to build a business around them. People who worked with him described him as quiet, rigorous, and relentlessly focused on data and execution. He avoided the spotlight, gave few interviews, and seemed content to let clinical results and revenue do the talking. In an industry famous for big promises, that restraint became its own kind of advantage.

By 2015, the numbers were almost surreal. Revenue had grown from $1.6 billion in 2005 to $32.6 billion in 2015. Operating margins topped 60%. Across 2014 and 2015, the company generated more than $20 billion in cash. This wasn’t just “a great launch.” It was a financial ramp that had almost no parallel in large-cap pharmaceuticals.

And yet, even at the top, the next problem was already embedded in the product.

Hepatitis C is curable. Gilead’s drugs didn’t create a chronic customer base the way HIV medicines did—they erased it. Every patient cured was, by definition, one fewer patient left to treat. The miracle was also the market shrinker.

That dynamic showed up quickly. By 2017, Gilead was reporting steep declines in Sovaldi revenue. Competition had arrived, payers pushed hard for discounts, and pricing pressure intensified. But the bigger structural issue was simpler: the pool of treatable patients really was getting smaller. In the U.S., hepatitis C cases were concentrated among baby boomers who’d contracted the virus decades earlier, often through blood transfusions or intravenous drug use. As that population got cured, the remaining cases tilted toward groups the system traditionally struggles to reach and treat—people in prison, people who inject drugs, and the uninsured.

Gilead tried to answer some of the access criticism with a global strategy. It offered tiered pricing, charging far less in developing countries than in the U.S. It also granted licenses to generic manufacturers in India to produce lower-cost versions for poorer nations. The programs helped, but they didn’t erase the controversy. Critics argued the moves came only after intense backlash, and that many middle-income countries landed in an especially painful gap: too wealthy to qualify for broad generic access, too poor to afford rich-country pricing.

In 2016, Martin moved to executive chairman and handed the CEO job to his longtime deputy, John Milligan. The handoff signaled continuity—keep the scientific DNA that had delivered HIV and hepatitis C—while acknowledging that the next chapter would be harder. The hepatitis C surge was fading, HIV was getting more competitive, and Gilead needed a new engine.

HIV, in particular, was entering a more contested phase. Patents on the original tenofovir formulation were expiring, opening the door to generics. Gilead had developed a next-generation version, TAF (tenofovir alafenamide), with improved safety, but critics questioned whether the clinical improvements warranted a reset on patent life and continued premium pricing. In other words, the same argument that had exploded around hepatitis C—value, price, and who gets access—was now echoing through HIV.

For years, Gilead had been able to outrun these questions with growth. Now the company was being forced to face them head-on: what comes after a once-in-a-generation windfall? Should the next leap be built in-house or bought? And could Gilead replicate its antiviral dominance somewhere else—or was the era that defined it already starting to close?

VII. Modern Era: Diversification & New Challenges (2016–Present)

The Gilead that came out the other side of the hepatitis C peak looked, on paper, unstoppable—and in practice, newly constrained. HIV was still a powerhouse, but it was no longer an open field. Hepatitis C was shrinking for the best possible reason: the drugs worked. Meanwhile, Gilead had piled up an enormous cash hoard—at times more than $30 billion—and investors wanted to know the plan. What do you do after you’ve already had the biggest win?

In March 2021, the company lost the figure most associated with that run. John C. Martin died from head injuries after a fall, a tragedy that stunned the biotech world. Martin had taken Gilead from a high-stress, pre-profit research outfit to a global pharmaceutical force. His era included the breakthrough HIV franchise, the once-in-a-generation hepatitis C cure, and the deal instincts that made both possible. Even with the pricing controversies that followed Gilead for years, his strategic calls reshaped the company—and, in many ways, the industry.

The clearest “next act” strategy was oncology. In September 2020, Gilead announced it would buy Immunomedics for $21 billion, its largest acquisition since Pharmasset. The centerpiece was Trodelvy (sacituzumab govitecan), an antibody-drug conjugate approved for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. This was Gilead’s statement that it could take what it had built in antivirals—development discipline, commercial scale, and global reach—and try to build a new franchise in cancer.

A few months later, in December 2020, Gilead also acquired MYR GmbH for €1.15 billion plus up to €300 million in milestone payments. MYR focused on chronic hepatitis delta virus, a rare but severe form of viral hepatitis that often appears alongside hepatitis B. It was diversification, but also a return to the company’s roots: virology, just in smaller and harder corners of the market where big breakthroughs still mattered.

Then COVID-19 put Gilead back on the front page. Remdesivir—originally developed for Ebola—showed activity against SARS‑CoV‑2. In May 2020, the FDA granted emergency use authorization, and remdesivir became one of the few available treatments during the pandemic’s terrifying first wave. The moment looked like another Gilead signature: an antiviral ready when the world needed it. But as more data arrived, the benefit looked more modest than early headlines suggested. Remdesivir didn’t become a clean, universally celebrated triumph the way the hepatitis C drugs had. It became something messier: a widely used therapy, and a continuing scientific argument.

Through all of this, HIV remained both Gilead’s anchor and its lightning rod. Biktarvy, launched in 2018, became a new standard of care: a single-tablet regimen combining bictegravir with the company’s TAF backbone. By 2023, Biktarvy was generating more than $10 billion in annual revenue—one of the best-selling drugs in the world. And yet the pricing debates never really faded. That year, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review criticized a 5.49% price increase, estimating that the increase alone added $815 million in costs to U.S. payers. For a mature drug in a stable patient population, it was the kind of move that reignited the core question Gilead can’t seem to escape: where’s the line between pricing power and public trust?

PrEP—pre-exposure prophylaxis, using Truvada or Descovy to prevent HIV infection—became another front in the same war. Clinically, the impact was extraordinary, cutting transmission risk by more than 90% in high-risk individuals. Public health leaders saw PrEP as a key tool for ending the HIV epidemic. But in the U.S., the annual cost exceeded $20,000, and access lagged. Activists pointed to the role of government-funded research in developing Truvada and argued that a public health necessity was being treated like a luxury product.

At the same time, the competitive environment tightened across the board. In HIV, ViiV Healthcare—majority owned by GlaxoSmithKline—emerged as a serious challenger, especially with long-acting injectable regimens that could shift patients away from daily pills. That’s a direct threat to the very paradigm Gilead helped make dominant. In oncology, the antibody-drug conjugate space got crowded fast, with multiple companies pursuing similar approaches. Trodelvy mattered, but it didn’t come with monopoly-like room to run. And Gilead knew better than anyone how quickly a franchise can go from unstoppable to pressured once competition, pricing, and payer leverage converge.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Gilead’s story is a masterclass in how pharma companies actually win—and why those wins so often come with blowback. The same moves that created enormous value also created unavoidable friction with payers, politicians, and the public.

The Biotech Acquisition Model: When to Buy vs. Build

Pharmasset is the purest version of “buy the science.” Gilead paid about $11 billion for a company with essentially no revenue, on the belief that sofosbuvir’s clinical data was real and durable. It was. And the payoff was historic.

But this play only works if you can do two things at once: pick the right target with near-obsessive discipline, and stomach a premium price before the market has certainty. Get either part wrong, and you’re left holding an overpriced asset that fails late, launches into unexpected competition, or never becomes the franchise you modeled.

What makes Gilead interesting is that it also proved the opposite model can work. With HIV, it in-licensed tenofovir early and relatively cheaply, then spent years building the clinical, regulatory, and commercial machine around it. Same company, two very different paths—one built patiently, one bought boldly.

Pricing Power in Life-Saving Drugs: Ethics vs. Economics

No part of the Gilead saga explains the pharma business better than Sovaldi pricing. The strategy was coherent: when you have a breakthrough, you charge like a breakthrough, because drug R&D is risky, and the winners have to fund the losers. In that framework, high prices aren’t a bug; they’re the incentive system.

The criticism was also coherent: when the “customer” is a patient with a life-threatening disease, there’s no real negotiating leverage. Prices aren’t anchored to R&D costs. They’re anchored to what insurers and governments can be forced to cover, what budgets can absorb, and what public outrage the company believes it can ride out. With Sovaldi, the debate wasn’t whether the drug worked—it clearly did. The debate was who got to capture the value created by a cure.

The Importance of Board Composition

From Donald Rumsfeld to Gordon Moore, Gilead built a board that signaled influence as much as oversight. Those connections mattered. They helped the company navigate regulators, government stakeholders, and strategic partners with a sophistication that many biotechs simply don’t have.

The trade-off is reputational risk. The Rumsfeld-Tamiflu episode showed how quickly a business decision can become a political story. But strategically, the advantage was real: Gilead repeatedly operated like a much larger company long before it actually was one.

Patent Cliffs and Portfolio Management

In pharma, today’s blockbuster is tomorrow’s patent cliff. Gilead’s core skill wasn’t just discovering drugs—it was extending franchises without waiting for competitors to force its hand.

The shift from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate to TAF is the template: improve the profile, move patients over, and refresh the lifecycle before generics eat the base. Layer on fixed-dose combinations, and you don’t just defend a molecule—you defend a product experience, a prescribing habit, and a bundle of intellectual property. That requires sustained R&D and a willingness to cannibalize your own products while you still can.

The Contract Manufacturing Model

Gilead has often leaned on contract manufacturing organizations instead of building huge in-house plants. That keeps capital costs and fixed overhead lower, and it gives flexibility when demand swings—something that mattered enormously when hepatitis C volumes dropped after the cure wave.

But flexibility comes with exposure. You give up some control, and you accept that supply continuity can be vulnerable to third-party constraints and disruptions. It’s a trade: less industrial muscle, more agility.

Global Access Strategies and Tiered Pricing

Tiered pricing—charging wealthy countries more and poorer countries less—sounds simple until you try to implement it. In practice, it’s one of the only workable ways to expand access while keeping the economics of innovation intact. It’s also politically fraught, especially in the countries that fall in between: not poor enough for the lowest prices, not rich enough to pay like the U.S.

Gilead’s hepatitis C licensing strategy, including enabling generic production in India for lower-income markets, became a reference point for the industry. It broadened access, but it didn’t end the argument. It just clarified the reality: global medicine isn’t one market. It’s many markets, with different budgets, different politics, and different ideas of what “fair” should mean.

IX. Analysis: Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

Start with the obvious: Gilead still sits on the most durable franchise in modern pharma—HIV. Even with louder competition, Biktarvy has stayed the default choice for a huge share of patients because it works, it’s tolerable, and it’s simple. And in HIV, “simple” isn’t marketing copy; it’s adherence, and adherence is outcomes. Once someone is virally suppressed on a regimen that fits their life, doctors have every reason to leave it alone. Those switching costs are real.

The long-acting injectable threat matters, but it’s not a guaranteed mass migration. For some patients, monthly injections are a major win. For others, they’re a hassle, a needle, a clinic visit, and a scheduling problem. Daily pills, especially when it’s one pill once a day, remain a pretty compelling baseline.

Then there’s the attempt to build a second act: oncology. Trodelvy gave Gilead something it badly needed—an approved cancer asset with room to expand. The broader bet is that antibody-drug conjugates can become a platform, not just a product. If Trodelvy continues to show strength in additional indications, and if Gilead can use its scale to drive adoption and build follow-ons, the Immunomedics deal could eventually feel less like a splurge and more like a cornerstone—maybe even a Pharmasset-style pivot.

Finally, the company still has what most biotechs chase for their entire existence: cash. HIV continues to generate enormous profits, which means Gilead can fund R&D, pay shareholders, and still have the flexibility to do deals. When the right target appears, it doesn’t need to ask permission.

The Bear Case

The hard truth in pharma is that time always wins. Patents expire. Generics arrive. And even great franchises can get repriced overnight when exclusivity ends. Gilead’s HIV portfolio isn’t immune. Key components have faced, or will face, generic competition, and the TAF-based era has its own clock. When a generic version of a leading regimen eventually hits, the pressure on pricing can be brutal.

There’s also a strange “bear case” that’s morally positive: the hepatitis C pattern could repeat. Gilead cured patients out of the hepatitis C market. In HIV, a combination of better prevention, including long-acting options like cabotegravir, and broader public health execution could reduce new infections over time. That’s the outcome the world should want. But for Gilead, fewer infections ultimately means fewer patients.

And then there’s pricing. Gilead has been in the center of drug pricing politics for years, and the temperature is rising, not cooling. Government payers have more tools, public tolerance for increases is thinner, and every high-profile price move becomes a fresh headline. Over time, that can mean margin compression—either directly through negotiated prices or indirectly through the pressure to restrain increases.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate to low. The barriers are enormous—capital, time, clinical risk, and regulatory scrutiny. But big, well-funded players can still “enter” by buying their way in, just like Gilead did.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Rising. PBMs, governments, and large health systems have consolidated leverage. The era of price setting without serious resistance is fading.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Generally low. Gilead relies heavily on contractors, and for many products the underlying inputs are not unique. That said, outsourcing can also introduce operational dependencies when supply chains get tight.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate. In HIV, long-acting injectables are a true alternative to daily oral therapy. In oncology, substitution is constant because the field is crowded and approaches vary widely across tumor types.

Competitive Rivalry: High, and getting higher. In HIV, rivals like ViiV and Merck keep investing. In oncology, deep-pocketed competitors are everywhere.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers

Scale Economies: Limited. R&D is expensive, but Gilead’s outsourced manufacturing model means it captures less classic industrial scale advantage than a fully integrated pharma giant.

Network Effects: None. Drugs don’t get stronger because more people use them.

Counter-Positioning: Historically meaningful. Gilead was willing to make bold, expensive bets and then price aggressively—moves that competitors couldn’t always mirror quickly. Whether that advantage persists is less clear in today’s environment.

Switching Costs: High in HIV, lower in oncology. Stable HIV patients and their physicians tend to stick with what works. In cancer, treatment choices change faster, and switching is often driven by disease progression.

Branding: Complicated. Gilead has deep credibility with clinicians and scientists, but its reputation with the broader public has been repeatedly scarred by pricing fights.

Cornered Resource: Eroding. Patents are finite, and as expirations approach, the “resource” becomes less cornered by definition.

Process Power: Real. Gilead’s track record suggests it’s unusually good at clinical development, regulatory execution, and scaling a therapy globally once it works.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For long-term investors watching Gilead, two metrics tell you most of what you need to know:

-

HIV franchise trajectory: Not just whether revenue is up or down, but why. Is Biktarvy holding share? Are prices holding? Are volumes stable? Any slippage here matters because HIV is still the core engine.

-

Oncology’s share of the business: The diversification story only becomes real when oncology is big enough that it can carry the company through the next set of antiviral patent cliffs.

Together, they capture the central tension of modern Gilead: defend the cash machine you built, and prove you can build the next one before time runs out.

X. Epilogue: "If We Were CEOs"

So if we were sitting in the CEO chair, with HIV still throwing off cash and the post–hepatitis C hangover still shaping the stock, what would we do next?

The obvious hunting ground is cell and gene therapy. Gilead already dipped a toe in with the 2017 acquisition of Kite Pharma and its CAR‑T platform, but the integration proved difficult and the commercial results have been mixed. Still, the logic hasn’t gone away. The space is fragmented, the science is moving fast, and the biggest bottleneck isn’t always the biology—it’s whether you can make these therapies reliably, at scale. If there’s a truly transformative deal out there for Gilead, it might be less about buying a single asset and more about buying a manufacturing and delivery platform that can turn cell therapy into something closer to a repeatable product.

But any “next act” has to run through the same issue Gilead can’t outrun: the balance between innovation incentives and access. The hepatitis C episode made one thing unmistakable. When Gilead has monopoly-like power over a life-saving therapy, it will price aggressively. That decision created enormous shareholder value—and also a backlash that never really faded. The lesson for the future isn’t just “be nicer.” It’s that pricing is now strategy, politics, and reputation all at once. Future launches and increases won’t be judged only against competitors. They’ll be judged against the precedent Gilead itself set, and against a public that now expects miracles to come with a plan for access.

The other open question is what antiviral leadership even means after COVID. The pandemic validated the importance of antiviral research, and also its limitations. Remdesivir helped some patients, but it wasn’t the kind of clean, transformational moment that hepatitis C was. The next pandemic—and there will be one—will demand faster development and broader availability. Gilead has the expertise to be a central player in that world. The harder decision is whether to invest heavily in preparedness, where the need is enormous but the commercial path is uncertain, or to focus capital on categories with more predictable returns.

In the end, Gilead’s story keeps coming back to the same tension: scientific ambition versus commercial reality. The company has delivered genuine medical breakthroughs—curing hepatitis C, turning HIV into a manageable condition, and giving some COVID-19 patients an option when few existed. Those are not abstract wins; they changed lives. At the same time, Gilead has extracted enormous profits from diseases that often hit vulnerable populations hardest, and it has repeatedly faced criticism that its pricing choices put shareholder returns ahead of patient access.

That tension isn’t going away. The next chapter will be written by leaders operating under tighter competition, tougher payer dynamics, evolving regulation, and constant public scrutiny. For Gilead, the challenge now looks like the classic problem of any empire: not conquest, but maintenance. The question is whether it can keep innovating, acquiring, and executing at the level that built the antiviral empire—while building enough trust to keep the world willing to pay for the next miracle.

XI. Recent News

In the most recent quarters, Gilead has kept pushing the company into its next shape. HIV remains the steady engine: Biktarvy has largely held up in the face of new competition, continuing to post strong prescription trends and reminding everyone why Gilead built its empire on simple, durable regimens.

The diversification story is progressing, but it hasn’t been a straight line. Oncology revenue has grown, yet Trodelvy’s adoption has moved more slowly than the most optimistic expectations that surrounded the Immunomedics deal. That doesn’t make the strategy wrong—it just reinforces how hard oncology is to scale, even with a strong product, once you’re competing in crowded categories and navigating real-world prescribing habits.

Financially, the company has leaned into a familiar move when growth is less explosive: returning capital. Dividends and share buybacks have remained a meaningful part of the story, signaling confidence in the durability of cash flows even as the business matures.

Behind the scenes, the pipeline continues to churn. Gilead has been advancing programs in inflammation and immunology—fields that sit close to its core expertise in serious, complex diseases—while living with the reality that drug development is a probabilistic grind. Some clinical programs have moved forward; others have delivered mixed results or been discontinued. That inconsistency isn’t a surprise. It’s the job.

And hanging over all of it is the same external force that’s shaped Gilead’s public narrative for a decade: pricing politics. Washington’s scrutiny of pharmaceutical costs hasn’t eased, and Gilead still shows up as a reference point in those debates. The company has engaged with policymakers, but it continues to argue that its pricing approach is tied to the economics of innovation—an argument that has always been easier to make on an earnings call than in the court of public opinion.

XII. Links & Resources

Company Materials - Gilead Sciences annual reports and SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q) - Gilead Sciences investor relations presentations - FDA approval letters and drug labels for Viread, Truvada, Atripla, Sovaldi, Harvoni, Biktarvy, and Trodelvy

Government and Regulatory Sources - U.S. Senate Finance Committee report on Sovaldi pricing - FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designations database - Congressional Budget Office analyses of pharmaceutical pricing

Industry and Academic Resources - Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) reports on Gilead products - Nature Biotechnology and Nature Medicine coverage of antiviral drug development - New England Journal of Medicine clinical trial publications for major Gilead drugs

Books and Long-Form Articles - Major business-publication coverage of the Pharmasset acquisition - Profiles of John C. Martin in Forbes and Bloomberg Businessweek - Investigative reporting on pharmaceutical pricing from STAT News and The New York Times

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music