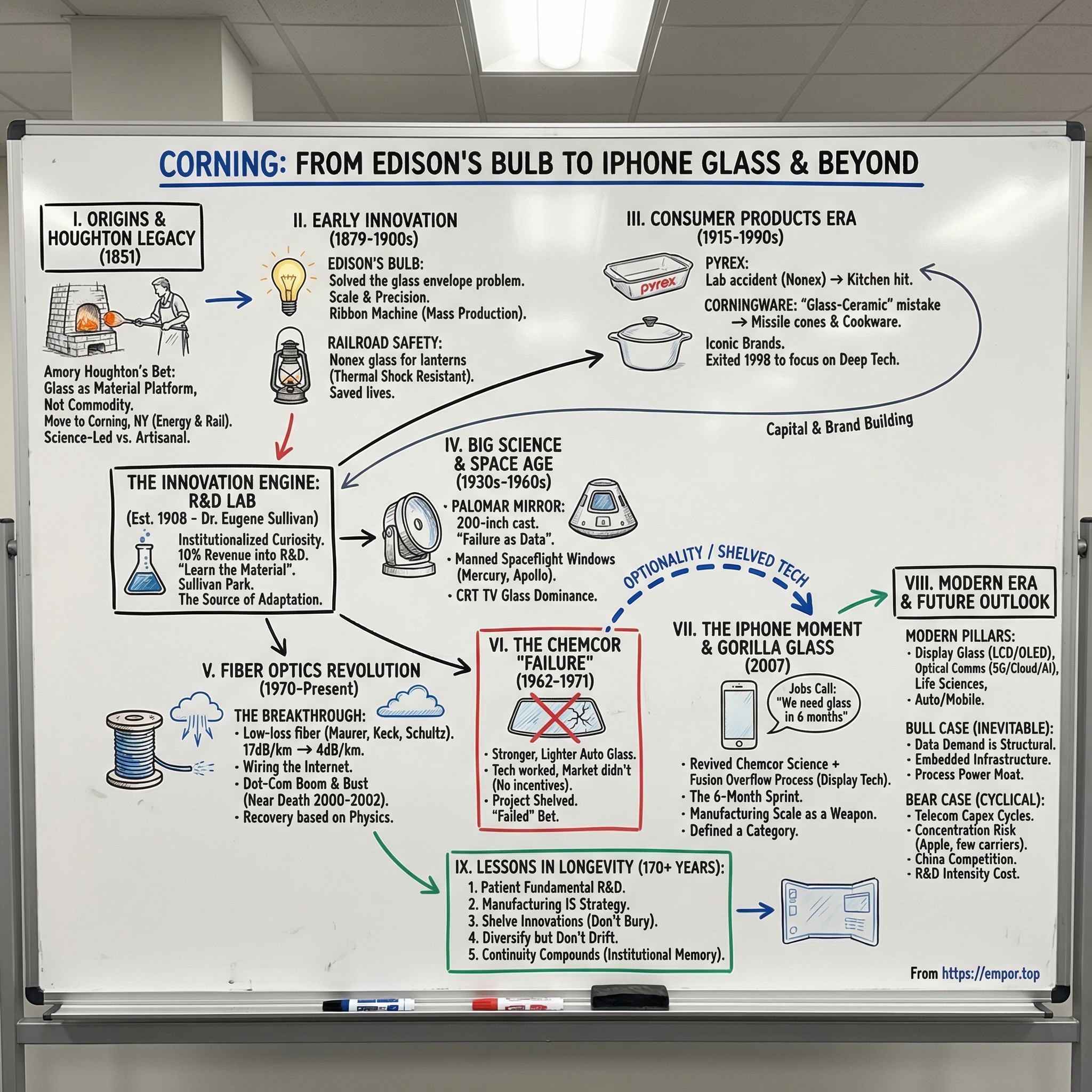

Corning: From Edison's Bulb to iPhone Glass

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a material so versatile it has cradled Thomas Edison’s first practical light bulbs, helped astronomers peer into the universe from a mountaintop in California, carried the world’s data through hair-thin strands of light, and now protects the device you probably have in your pocket. That material is glass. And one company has spent more than 170 years learning how to make it do things glass was never supposed to do.

Corning Incorporated sits at a strange intersection in American business: a materials science powerhouse most people can’t name, even as they touch its innovations dozens of times a day. With $13.1 billion in GAAP sales in 2024 and $1.25 billion in free cash flow, Corning isn’t a quirky relic from the industrial age. It’s a hidden giant—quietly underpinning huge pieces of modern life.

So here’s the question that makes this story worth telling: how did a company known for Pyrex casserole dishes and railroad lanterns become essential to the iPhone and the fiber optic networks that run the internet? The answer isn’t one breakthrough. It’s a pattern—of reinvention, of compounding scientific advantage, and of betting, again and again, that the next era of technology would need a better kind of glass.

We’re going to follow Corning from its beginnings in 1851, when Amory Houghton made a bet on glass as America industrialized. We’ll watch it win Thomas Edison’s trust, build iconic consumer brands, attempt the seemingly impossible with the Palomar telescope mirror, and then reinvent itself yet again—this time as a backbone supplier to global telecommunications. Along the way, we’ll hit the dot-com boom and bust that nearly broke the company, and the improbable comeback kicked off by a now-legendary phone call from Steve Jobs.

At its core, this is a story about what happens when a company treats research and development not as overhead, but as identity. When curiosity becomes strategy—and when that strategy is pursued long enough, it turns into a moat.

II. Origins & The Houghton Legacy

In 1851—the same year Herman Melville published Moby-Dick and London hosted the first World’s Fair—a businessman named Amory Houghton made a wager on America’s industrial future. The country was speeding up. Railroads were pushing outward, cities were swelling, and factories were multiplying. And all of it demanded the same unglamorous input, in enormous quantities: glass.

Houghton started Bay State Glass Company in Somerville, Massachusetts, stepping into a crowded, brutally competitive trade. American glassmaking was still largely artisanal then: craftsmen shaping molten material by hand, quality varying from batch to batch, and “innovation” mostly meaning a tweak in technique rather than a leap in understanding. Most makers competed on price, on access to fuel, and on closeness to customers—not on chemistry or physics.

Houghton saw something different. To him, glass wasn’t just a commodity you turned into jars and windows. It was a material platform—something you could study, improve, and tailor to specific jobs. That idea sounds obvious now. In the mid-1800s, it was a genuinely contrarian way to run a manufacturing business.

The early years were hard. Margins were thin, competitors were everywhere, and the Panic of 1857 hit American industry like a trapdoor opening. Bay State Glass never quite found stable footing in Massachusetts. The inflection point came in 1868, when Amory Houghton Jr. took over and made the decision that effectively created the Corning we know today: move the operation to upstate New York, to a small town with two assets that mattered more than prestige—ready energy for furnaces and rail access to ship product.

That town was Corning, New York. The company became Corning Glass Works. And what had been a struggling manufacturer started to look like a generational institution.

The Houghtons’ real differentiator wasn’t a secret recipe or a clever sales strategy. It was a near-religious commitment to science. From the beginning, they treated research and development as the way out of a crowded market. While rivals chased cost cuts and output, Corning aimed to win by understanding glass itself—its composition, its behavior under heat and stress, its limits, and how to push past them.

This wasn’t a slogan. It became the family’s operating system. They hired scientists when others hired only craftsmen. They put money into experiments when others put money only into more furnaces. And they developed a habit that would define Corning for the next century and a half: don’t just make glass—learn it.

That continuity lasted an almost absurdly long time in American business terms. James R. Houghton, the founder’s great-great-grandson, served as chairman from 2001 to 2007—more than 150 years after the company’s start. Most family firms sell, fracture, or fade long before they reach a fifth generation. Corning didn’t. The mission stayed steady even as the products would change again and again.

Over time, the family’s ownership diluted to about 2%. But the culture they built—patient, science-led, and willing to invest in research without guaranteed payoffs—stuck. The equity shrank; the philosophy didn’t.

Being based in Corning, New York mattered too. The company and the town grew up together, intertwined in a way that’s hard to replicate in a major financial hub. That rootedness helped insulate Corning from the constant pull of short-term thinking and gave it something many industrial companies lack: institutional memory. When you’re trying to compound technical advantage over decades, that stability is not a nice-to-have. It’s a weapon.

By the 1870s, Corning Glass Works was a credible force in American glassmaking—but still, in many ways, just one of many. The event that would catapult it from regional manufacturer to national significance would come from outside the company: a partnership with another ambitious innovator, a 32-year-old inventor who needed a very particular kind of glass.

III. Early Innovation: Edison's Light & Railroad Safety

In 1879, Thomas Edison was in a sprint against rivals on both sides of the Atlantic to build a practical incandescent light bulb. He’d cracked plenty of the puzzle—vacuum, filament experiments, electrical math—but one problem refused to cooperate. It wasn’t theoretical. It was material.

He needed glass that could do a very specific, very unforgiving job.

The bulb had to protect a delicate filament, hold a vacuum without leaking, survive the heat of operation, and resist the everyday knocks that would happen once light bulbs left the lab and entered homes. And it couldn’t be a bespoke curiosity. Edison needed it in volume—enough to make electric lighting a business, not a demo.

So he came to Corning. And Corning, unusually for a glassmaker of the era, had spent decades building real expertise in specialty glass. By 1880, Edison designated Corning as his sole supplier for the glass envelopes used in his lamps.

That choice mattered. For Edison, it removed a production bottleneck that could have slowed his entire rollout. For Corning, it was something even more valuable than revenue: a forcing function. Supplying Edison meant learning precision at scale—tight tolerances, consistent quality, relentless iteration. It also validated the Houghton bet that science-led glassmaking could open doors that commodity producers would never even see.

The results showed up fast. Corning’s bulb-shaped glass became so central to the company that by 1908, light bulb envelopes accounted for about half its business. In less than thirty years, a company founded to make everyday glassware had become an essential supplier to the electrification of the modern world.

But keeping up with Edison’s demand required more than good chemistry. It required a breakthrough in how glass could be made.

Enter William Woods, a former glassblower who understood the old craft and the new industrial reality. Alongside engineer David E. Gray, Woods created the high-speed ribbon machine—an innovation that turned bulb production into something closer to a continuous process than a series of hand operations. It could produce roughly 400,000 bulb blanks in a day, about five times what earlier methods could manage.

The ribbon machine’s genius was its flow: molten glass formed into a ribbon, then shaped again and again as it moved through a coordinated system of molds and air. Less artisanal. More engineered. And the impact was exactly what you’d expect when you unlock manufacturing scale: costs fell, supply surged, and light bulbs became cheaper—helping push electric lighting from novelty to infrastructure.

Corning later adapted the same approach to a new mass-market product. In 1933, the ribbon machine was used to manufacture radio bulbs, helping bring down the cost of radio sets and accelerating the rise of radio as America’s dominant medium before television.

And while Edison made for a great headline, Corning’s early identity wasn’t built only on famous partnerships. It was also built on solving problems most people never noticed—until they went catastrophically wrong.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, America’s railroads had a dangerous issue. Signal lanterns were crucial for safe operation, but their glass globes sometimes shattered from thermal shock. A lantern could burn hot through a freezing night, then crack or burst when hit by rain or snow. When signals failed, trains didn’t just get delayed. They crashed.

Corning scientists William Churchill and George Hollister went after the problem the Corning way: start with the physics, then engineer the material. They developed a glass called Nonex—short for non-expansion—designed to withstand rapid swings in temperature. With an extremely low coefficient of thermal expansion, it barely changed size with heat or cold, which meant far less cracking. It also improved visibility at longer distances, making signals clearer for locomotive engineers.

The outcome was simple and enormous: fewer failures, fewer accidents, and lives saved. A humble glass globe became a safety technology—and another proof point that Corning wasn’t competing like a traditional glassmaker. It was engineering glass to specification, then producing it reliably, at scale.

Put the Edison bulbs next to the railroad lanterns and you can see the pattern forming early. Find customers with hard technical constraints. Solve the constraint with materials science. Then make the solution manufacturable enough to matter.

By 1908, Corning had grown into a specialized powerhouse. But leadership understood something that would define the company for the next century: staying ahead couldn’t depend on one-off heroics. If scientific advantage was going to be the strategy, it needed a permanent home inside the company.

IV. The Research Laboratory & Scientific Foundation

In 1908, a chemist named Dr. Eugene Sullivan stepped off the train in Corning, New York, with a mandate that would quietly determine what this company could become. He was there to build one of the first industrial research departments in the United States—an idea so new that, in most boardrooms, it would’ve sounded like paying people to think.

At the time, corporate research labs were the rare exception. General Electric had started one in 1900. DuPont followed in 1903. But most American companies still treated discovery as the job of universities. Businesses made, marketed, and sold. They didn’t run experiments for their own sake.

Corning chose a different path. Sullivan assembled a small internal brain trust—chemists, physicists, and engineers—focused not on cranking out incremental product tweaks, but on understanding glass at the fundamental level. What happens when you change the recipe? How does it behave under heat, shock, pressure, time? And, just as important: what could glass do that nobody had asked it to do yet?

This lab turned the Houghton family’s instincts into an institution. Instead of relying on a few gifted individuals or occasional bursts of invention, Corning built a repeatable engine for innovation. The scientists had permission to go deep—often without immediate commercial pressure—because management believed the payoff would come, even if it took years.

That patience shaped the company’s strategy in the decades that followed. After World War II, Corning’s leadership leaned explicitly into research-driven product innovation—building materials to meet emerging needs, sometimes before customers fully knew how to describe them. It wasn’t innovation as a marketing line. It was innovation as the operating model.

And Corning backed it with real money. Over time, the company invested roughly 10% of its revenue into research and development. In more recent years, it also put $300 million toward expanding its Sullivan Park research facility near headquarters in Corning, New York—named for the chemist who started the whole thing.

This is where Corning’s advantage starts to compound. Each decade of research didn’t just produce new products; it produced deeper understanding, more specialized processes, and institutional memory. Experienced scientists trained the next generation. Manufacturing techniques became proprietary and hard to copy. Competitors could see the end product, but they couldn’t easily replicate the know-how required to make it reliably, at scale.

Just as importantly, the lab made Corning adaptable. When one market matured, or got disrupted, Corning didn’t have to reinvent itself from scratch. Its core asset wasn’t a single product line—it was a growing body of materials science capability. That meant it could move from one industry to another without losing its identity.

The research culture also became a magnet. Top scientists wanted to work at Corning because they could do serious work with real resources and long time horizons—conditions most corporate employers couldn’t offer. That created a loop: great talent produced breakthroughs, breakthroughs produced commercial wins, and wins funded the next wave of research.

In the chapters ahead, that lab will show up again and again—behind heat-resistant cookware, space-age glass-ceramics, and the fiber that carries the internet. But its biggest legacy wasn’t any single invention. It was making R&D non-negotiable—turning research from a cost center into Corning’s core advantage, the foundation everything else was built to protect.

V. Consumer Products Era: Pyrex, CorningWare & Innovation

In 1913, Corning hired a physicist, Dr. Jesse Littleton, to do the kind of work Sullivan’s lab was built for: explore what heat-resistant glass might be good for beyond the factory floor. It sounded like a routine research brief. It turned into one of the most famous product launches in American kitchen history—and the spark didn’t come from a lab bench. It came from Littleton’s home.

Bessie Littleton had the same problem countless home cooks had: her earthenware casserole dish cracked in the oven. Cookware then wasn’t designed for repeated cycles of heat and cooling. It broke, and you replaced it, and everyone accepted that as normal.

Jesse didn’t. He brought home the sawed-off bottoms of two glass jars made from Corning’s heat-resistant Nonex formula—the same low-expansion glass that had made railroad signal lanterns safer. It wasn’t elegant. It was an experiment you’d do when you work at a glass company and you can’t stop thinking about materials.

Bessie baked a sponge cake in the improvised dishes. The glass didn’t crack. So she pushed it further: steaks, French fries, more cooking, more heat. It kept holding up. Jesse brought the results back to Corning, and suddenly the lab had a new answer to a very old consumer problem: what if cookware didn’t have to be fragile?

Two years later, in 1915, Corning launched Pyrex, the first consumer cooking products made from temperature-resistant glass. Pyrex quickly became more than a brand—it became shorthand. People didn’t just buy Pyrex; they started calling the category Pyrex.

The origin story matters because it’s pure Corning. The company already had the scientific breakthrough. The world already had the need. The leap was connecting the two in a way that worked in real life. A kitchen became the proving ground for a lab material, and Corning got something most industrial companies never manage to build: a household name.

Pyrex also pulled Corning into an entirely different kind of business. Selling to consumers meant packaging, retail distribution, merchandising, and marketing—muscles you don’t develop selling glass components to industrial customers. But the payoff was visibility and a durable profit stream, all built on the same core strength: invent a better material, then make it manufacturable.

Then, decades later, Corning stumbled into lightning twice.

In the 1950s, a researcher named S. Donald Stookey was experimenting with photosensitive glass when a furnace malfunction sent a sample far beyond its intended temperature. This was the kind of mistake that usually ends with a puddle on the bottom of the furnace and a bad day in the lab.

Instead, Stookey opened the furnace and found the sample still intact—milky white from crystallization. Then he dropped it. It didn’t shatter. It bounced.

What he’d accidentally created was a new family of materials: glass-ceramics—substances with the formability of glass and the toughness and temperature resistance of ceramics. Corning commercialized the breakthrough as CorningWare: cookware that could handle dramatic temperature swings without cracking.

And as with so many Corning inventions, the technology didn’t stay in the kitchen. Glass-ceramics were used by the military in guided missile nose cones. NASA used ceramic glass components on the space shuttle. Same underlying material science—two wildly different use cases. That’s the Corning pattern in its purest form: consumer product on the surface, deep-tech platform underneath.

For years, Pyrex and CorningWare anchored Corning’s public identity. They were profitable, beloved, and tangible proof that the company’s research culture could produce products ordinary people cared about.

But by the 1990s, Corning was increasingly pulled toward markets where its science advantage mattered even more—places where performance, not branding, determined winners. Consumer products demanded constant retail execution and marketing spend, and they faced punishing price competition. Meanwhile, Corning’s research engine was opening doors in advanced materials for communications and displays—categories where customers paid for capabilities that were genuinely hard to replicate.

So in 1998, Corning exited the kitchen. It sold its Corning Consumer Products Company—home to CorningWare, Visions Pyroceram-based cookware, Corelle Vitrelle tableware, and Pyrex glass bakeware—to Borden. (That business would later become Corelle Brands and move through other ownership structures.)

For many consumers, that split was surprising. The Pyrex in the cabinet still said Corning, but it was no longer part of Corning Incorporated. Strategically, though, the move was consistent: Corning wasn’t abandoning innovation. It was concentrating it—choosing to put its research, capital, and attention into markets where its long-term technical edge could translate into long-term dominance.

The consumer era proved two things at once. Corning could turn lab work—even accidents—into iconic products. And it could also let icons go when they stopped fitting the future it was building.

VI. Big Science: Palomar Telescope & Space Age Glass

In 1932, a renowned astronomer named George Ellery Hale walked up to Corning with a request that sounded less like a purchase order and more like a dare.

Hale was building the most ambitious telescope anyone had ever attempted: a 200-inch reflecting telescope that would eventually sit at Palomar Observatory in California. But before any of that could happen, he needed the one part you couldn’t improvise later—the mirror blank. Not a finished mirror, not something you could patch or laminate. A single, flawless, low-expansion slab of glass, bigger than any ever cast.

The requirements were brutal. Any bubbles, voids, or subtle variations in the glass would warp the images. And the piece had to be enormous—about 20 feet across and around 20 tons. A previous attempt to make the optic from fused quartz had already failed. Hale was running out of options, and there weren’t many companies on Earth that even had a shot at pulling it off.

Corning said yes.

Its scientists developed a special low-expansion borosilicate glass and then had to invent the process around it: the molds, the controls, the whole choreography of casting something that didn’t fit the existing playbook. The first pour didn’t make it. The blank came out with voids—fatal for precision optics.

So Corning did what it had been training itself to do for decades: treat failure as data. The team adjusted the process and tried again. On December 2, 1934, Corning poured molten glass into a massive mold in a carefully controlled operation that took hours and demanded total precision.

And then came the hard part: waiting.

To avoid internal stresses, the blank had to cool painfully slowly. The cooling took a full year. During that year, the Chemung River flooded, and the blank was nearly lost. Workers fought to keep the water back—building barriers and pumping frantically—because there was no replacement. There was only this.

In 1935, the blank finally finished cooling. Corning had produced the largest piece of glass the world had ever seen. The successful blank was shipped cross-country to California for grinding and polishing, and the trip turned into a kind of rolling spectacle. People gathered just to watch this impossible cargo move through their towns.

The first, flawed blank didn’t get scrapped. It ended up in Corning’s Museum of Glass, where it still sits—a reminder that the second casting only existed because the first one failed.

The telescope itself, the 200-inch Hale Telescope, was completed in 1948 after years more work. It helped astronomers determine that the universe contains billions of galaxies, and it remained the world’s largest effective telescope for decades. Corning didn’t just supply a component. It enabled a leap in how humanity understood the cosmos.

That Palomar project was big science in the purest sense: not incremental improvement, but a one-time, frontier-of-physics problem where nobody could hand you a manual. Corning proved it could take on jobs like that—and survive the consequences when the first attempt went sideways.

That same capability mattered even more as America moved into the space age. When NASA’s Mercury program aimed to put the first Americans into orbit, it needed windows that could withstand the extremes of spaceflight: the vacuum of space, thermal cycling between sunlight and shadow, and searing heat during reentry.

Corning developed the heat-resistant windows used on Mercury spacecraft, which carried astronauts into successful orbital flights beginning in 1962. And it didn’t stop there. Corning went on to make window glass for every manned American spacecraft—from Gemini and Apollo to the space shuttle. When Neil Armstrong looked out at the lunar surface, he was looking through Corning glass.

If space was the prestige project, another mid-century wave was the volume business—and it was transforming American living rooms: television.

TVs relied on cathode ray tubes, and CRTs were, at their core, specialized glass systems. You needed the right properties. You needed consistency. And you needed an industrial machine capable of producing them at scale. Corning leaned in hard. By the 1950s, it was the world’s top supplier of CRT glass. By the 1960s, Corning was producing all of the world’s TV glass, including replacement bulbs.

It was the same pattern, just expressed in different arenas. A new technology creates a new set of material constraints. Corning’s research culture figures out the glass. Corning’s manufacturing turns it into scale. And once you can do both—better than anyone else—you don’t just participate in the market. You become the market.

From Palomar to Mercury to the television sets humming in homes across America, the mid-twentieth century cemented Corning as an indispensable enabler of technological progress. It had moved far beyond lantern globes and light bulb envelopes. Now it was working with astronomers, astronauts, and consumer electronics at industrial scale.

And yet, the most transformative shift—the one that would define Corning’s modern identity—was still forming inside its labs. A small team of researchers was chasing a question that sounded almost academic: could light travel through a thin strand of glass over meaningful distances?

VII. The Fiber Optics Revolution

In late 1970, Corning made an announcement that barely registered outside a small circle of physicists and telecom engineers. Four researchers—Robert D. Maurer, Donald Keck, Peter C. Schultz, and Frank Zimar—had demonstrated an optical fiber with an optical attenuation of 17 decibels per kilometer by doping silica glass with titanium.

On paper, that reads like lab-speak. In reality, it was a starting gun.

For years, researchers had dreamed about using light to carry information through hair-thin strands of glass, replacing copper wires for long-distance communication. The concept was elegant: if you could send signals as light, you could unlock far higher bandwidth over far longer distances. The problem was brutally practical. Light didn’t travel very far through early glass. It faded—fast. That fading, called attenuation, made fiber optics feel like a science fair project, not infrastructure.

Many believed the loss couldn’t be pushed low enough to matter. Corning proved otherwise. Getting down to 17 decibels per kilometer wasn’t a nice improvement; it was a break from the assumptions that had kept the field stuck. It meant light could travel far enough to start building real systems.

And then Corning did what it tends to do after the first breakthrough: it kept going. A few years later, the team produced a fiber with only 4 decibels per kilometer, this time using germanium oxide as the core dopant. That step change is what moved fiber optics from “promising” to commercially viable for long-distance telecommunications and networking.

Maurer, Keck, and Schultz would later be inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1993 and receive the 2000 National Medal of Technology. And their invention became foundational to modern communications—fiber optics now carry essentially all of the world’s long-distance voice, video, and data traffic.

What’s striking is how un-mysterious the source of the breakthrough is once you zoom out. It didn’t come from nowhere. It came from Corning being Corning: decades of accumulated expertise in glass chemistry, process control, and optical physics, all sitting inside the research culture that Eugene Sullivan had institutionalized back in 1908. When the fiber moment arrived, Corning was already one of the few places on Earth with the scientific depth—and manufacturing discipline—to actually capture it.

So Corning leaned in. It invested aggressively in manufacturing and grew into the world’s leading optical fiber producer. And it didn’t just sell strands of glass. It built a broader optical communications business around what telecom operators needed to deploy networks: fiber, cables, connectors, and related components.

Through the 1980s and early 1990s, the growth was steady, as telephone companies gradually replaced copper with fiber. Then the late-1990s dot-com boom hit, and “steady” turned into a stampede. Internet traffic surged. Carriers raced to lay capacity. And that capacity was, very literally, mile after mile after mile of fiber.

Corning’s profits soared. It expanded by acquiring Oak Industries and building new plants. It also pushed into photonics, aiming to become a full-system provider, not just the company that made the glass.

For a while, it worked—at least in the way it looked from the outside. Corning became a market darling. Its valuation went vertical. Analysts modeled endless demand for bandwidth and treated fiber capacity like a one-way bet.

Then, in 2000, the dot-com bubble burst.

The downturn wasn’t gentle. It was a trapdoor. Telecom companies realized they had overbuilt. Orders evaporated. Bankruptcies rolled through the sector. Customers that had been placing massive contracts canceled them—or disappeared entirely.

At the same time, Corning’s photonics push never reached the position the company wanted. The combination—telecom collapse plus photonics underperformance—hit like a meteor. Corning’s share price fell to around $1, and a company that had looked untouchable was suddenly fighting for its life.

What followed was the grim side of industrial reality: restructuring. Plants closed. Thousands of jobs were cut. Corning exited businesses that no longer penciled out. The company that had expanded so aggressively in the boom had to contract just as aggressively in the bust.

But Corning had something most dot-com wreckage didn’t: a real, enduring advantage. Fiber optics weren’t hype. The physics were undeniable. Oversupply could crush pricing and cash flow for years, but it couldn’t change the fact that fiber was the best way to move information over distance.

As the industry stabilized and data demand kept compounding, fiber orders slowly returned. By 2007, Corning had posted five straight years of improving financial performance—surviving the worst crisis it had faced since the Great Depression and emerging leaner, more focused, and far more disciplined about capital.

Corning had invented low-loss optical fiber more than fifty years ago. And ever since, it kept pushing the technology forward—helping build the networks behind broadband, cloud computing, and now 5G.

The fiber chapter is the full Corning experience in one arc: a world-changing materials breakthrough, a massive wave of adoption, an overexuberant capital cycle that nearly breaks the company, and a recovery grounded in the fact that the underlying invention was not just useful—it was inevitable.

VIII. The Chemcor Story & Failed Auto Glass Gambit

In 1962, Corning developed something that looked, at least on paper, like it should change the auto industry overnight. It was called Chemcor: a toughened glass meant for windshields that could be thinner and lighter than what cars used at the time. More importantly, it promised a safety upgrade. When it broke, it fractured into small granules instead of the long, dangerous shards people associated with broken glass.

The science was classic Corning. Using an ion-exchange process, the company put the surface of the glass into compression—basically pre-loading it with strength—so a thin sheet could take far more abuse than it had any right to. If Chemcor worked at scale, it offered a three-for-one: lighter vehicles, improved fuel efficiency, and fewer severe injuries in accidents. And for Corning, it offered something else: a path into one of the biggest manufacturing markets in the world.

Corning went after it seriously. It built capabilities, chased automakers, and got early traction. Chemcor showed up as side glass in a limited run of 1968 Plymouth Barracudas and Dodge Darts. Then it graduated to windshields, debuting on the 1970 model year Javelins and AMXs made by American Motors Corporation.

Technically, it did what Corning said it would do. The problem wasn’t performance. The problem was incentives.

At the time, there were no mandatory safety standards for motor vehicle windshields. The big automakers—General Motors, Ford, Chrysler—could stick with cheaper, established laminated glass that was already integrated into their plants and supply chains. Switching to Chemcor meant new tooling, new processes, and new risk. And consumers weren’t walking into dealerships demanding “ion-exchanged windshields,” so there was no obvious upside for the manufacturers.

So the majors passed. And without their volume, Corning couldn’t get the economics to work. In 1971, the company shut down the windshield project—later calling it one of its “biggest and most expensive failures.”

It’s a painful lesson, but a common one: technical superiority doesn’t guarantee commercial success. Corning had built a better windshield. But “better” wasn’t enough in an industry where supply chains were entrenched, switching costs were real, and nobody wanted to pay extra for an improvement they didn’t have to make.

It also exposed a mismatch. In aerospace, telecommunications, and later consumer electronics, Corning often worked with customers who obsessed over performance and were willing to pay for it. Auto manufacturing, by contrast, was a world of relentless cost pressure and deep resistance to supplier-driven change. Chemcor wasn’t just a product bet. It was a bet on an industry’s willingness to adopt—and Corning misread the timing.

But this is Corning, and the story doesn’t end with the failure. Because Corning rarely builds a technology that can only do one thing.

The ion-exchange strengthening process behind Chemcor didn’t vanish when the windshield project died. It went onto the shelf—proven science waiting for a market that would value it.

And at the same time, Corning scientists Stuart Dockerty and Clint Shay were inventing another manufacturing breakthrough: the fusion overflow process for making flat glass. Molten glass flowed down both sides of a tapered trough and rejoined at the bottom into a single sheet. The magic was that the glass surfaces never touched forming equipment, so they came out pristine—smooth enough to skip polishing entirely.

That “overflow glass” would become the precursor to Corning’s liquid crystal display glass substrates: the thin, flawless sheets that made flat-panel TVs and monitors possible, and eventually helped enable the modern smartphone era.

Chemcor itself would sit dormant for decades. But it wasn’t forgotten. Like many Corning inventions that miss their first market, the underlying capability eventually came roaring back in a context no one in 1971 could have predicted—and it would become central to one of the most important product launches of the 21st century.

That opportunity was waiting out in the future, in the pocket of a man about to place a very urgent phone call.

IX. The Steve Jobs Phone Call & Gorilla Glass Revolution

By now, the story is corporate legend—told so many times it risks sounding like folklore. But the core details are real, and they’ve been repeated on the record by Apple executives themselves.

When Steve Jobs unveiled the original iPhone in January 2007, the prototype didn’t have glass on the front. It had a hard plastic screen. The world was dazzled. The phone looked inevitable. Then Jobs did something simple: he put it in his pocket.

The screen scratched almost immediately.

Jobs called Jeff Williams—Apple’s operations chief at the time, and later its Chief Operating Officer—and got straight to the point. “We need glass,” Williams later recalled, telling the story to a crowd at Corning’s Harrodsburg, Kentucky facility. Williams tried to manage expectations. Maybe, he suggested, in three to four years glass technology would evolve far enough.

Jobs wasn’t buying “three to four years.” He wanted glass for the phone that would ship in June. Six months.

That deadline wasn’t just aggressive. It was the kind of request that turns into a nervous laugh in most manufacturing organizations: a new material, in production quantities, for a product about to define an entire category—on a timeline that barely allows for mistakes.

Jobs didn’t just make the demand over the phone. He flew to Corning, New York, to see CEO Wendell Weeks. He laid out what Apple needed: a cover material for the iPhone that was thin enough for touch, tough enough for daily abuse, and available in huge volume—fast.

Weeks told Jobs Corning had something promising: strengthened glass based on ion-exchange technology that traced back to the company’s earlier work on Chemcor in the 1960s. The science existed. The know-how existed. What didn’t exist was a production machine behind it. Corning wasn’t set up to mass-produce this specific glass for consumer electronics. There was no dedicated plant, no tuned process window, no established supply chain.

Jobs pushed anyway. He reportedly placed an order for a ton of the glass on the spot. Weeks objected that Corning couldn’t do it. Jobs kept pressing. “Don’t be afraid,” he told Weeks. “You can do this.”

Inside Corning, the request landed like a fire drill and a moonshot at the same time. John Bayne, a VP in Corning’s Gorilla Glass business, later said Corning typically needs close to two years of R&D to bring a new product to market. Apple was asking for six months—and not for a minor tweak, but for a rapid scale-up of a technology that hadn’t been produced commercially in decades.

The only reason it was even conceivable was that Corning had already done the slow work. Chemcor had provided the foundational strengthening science. That work had later been rolled into glass used for TVs and laptops. The pieces were there, scattered across time.

Now Corning had to assemble them at full speed.

The company repurposed a facility in Kentucky that had been designed for LCD-related manufacturing and reconfigured it for the new mission. Teams worked relentlessly to dial in glass chemistry, forming, strengthening, and quality control—simultaneously, at scale, under the kind of schedule pressure that leaves no room for “we’ll fix it in the next revision.”

They hit the date. When the first iPhone shipped in June 2007, it shipped with Corning’s strengthened cover glass—what the world would soon come to know as Gorilla Glass.

Gorilla Glass is a high-strength alkali-aluminosilicate thin sheet glass designed for scratch resistance and durability in touchscreens. And according to Walter Isaacson’s Steve Jobs biography, Gorilla Glass was used on that first iPhone.

Once Apple proved a glass-front smartphone could survive the real world, the rest of the industry followed. Competitors moved from plastic to glass, and Gorilla Glass became a default choice across smartphones and beyond.

Since 2007, Corning says it has delivered the equivalent of 58 square miles of Gorilla Glass—about 28,000 football fields’ worth. The product evolved through multiple generations, improving scratch resistance and durability, and spread into tablets, laptops, wearables, and automotive displays.

It’s a perfect Corning story because it’s not really about a single heroic six-month sprint. It’s about optionality created by decades of research that looked, at the time, like it might never matter. It’s about manufacturing as a competitive weapon—the ability not just to invent, but to scale. And it’s about the rare customer who doesn’t accept the supplier’s timeline and forces a company to find out what it’s actually capable of.

Chemcor’s ion-exchange chemistry. The fusion overflow know-how. The display-era manufacturing muscle. None of those alone would have been enough. Together, under pressure, they turned a failed automotive bet from the 1960s into the front face of the most important consumer device of the century.

X. Modern Era: Display Technologies & Telecom Dominance

The iPhone didn’t just give Corning a hit product. It pulled the company into the center of the modern consumer tech stack. But Corning’s present-day story is bigger than smartphone glass. Today it’s a diversified materials science company with leadership positions across display glass, optical communications, life sciences, environmental technologies, and specialty materials.

Start with displays—because in many ways, that’s where Corning’s manufacturing genius became impossible to ignore. Corning is one of the key suppliers of the glass substrates that make liquid crystal displays work: the flat, nearly flawless sheets that sit inside TVs, computer monitors, tablets, and other screens. And the reason Corning can do this at the quality and scale the industry demands goes back to a very Corning kind of breakthrough: the fusion overflow process developed by Stuart Dockerty and Clint Shay. By letting molten glass flow and fuse into a single sheet without the surfaces ever touching forming equipment, Corning could produce glass with pristine surfaces and tight thickness control—exactly what display makers require.

Over time, Corning pushed the material itself forward too. It developed extremely low-density glass compositions that helped LCDs go places they simply couldn’t before. The EAGLE glass product line, for example, paired lighter weight with high resolution and helped accelerate the proliferation of LCD TVs. As screens grew larger and thinner, Corning’s ability to reliably produce defect-free substrates at ever-larger sizes remained a differentiator—one that’s hard for competitors to match, because it’s as much about process discipline as it is about chemistry.

But if display glass is a pillar, optical communications is the engine room.

This is the segment that turned Corning’s 1970 fiber breakthrough into a long-duration growth business—selling fiber and related solutions to network operators building the physical infrastructure of the internet. In 2021, optical communications was about 31% of Corning’s revenue, making it the company’s largest segment. That year, sales in the segment grew 22% year over year, driven by investment in broadband, cloud computing, and 5G. Growth continued afterward as carriers kept spending to meet demand—at one point showing a 28% year-over-year jump to about $1.2 billion in a single quarter.

The surprising part, if you haven’t been watching Corning closely, is just how big this business has become. The company that once made glass for lanterns and casserole dishes now makes extraordinarily precise glass fiber—thin strands that carry data as pulses of light—and it does so at massive scale. When telecom companies upgrade networks, connect data centers, or push fiber deeper into neighborhoods for residential broadband, they need fiber. And Corning, built on the work of Maurer, Keck, and Schultz, still sits in an advantaged position more than five decades later.

The tailwinds here are structural. Global data traffic keeps growing. Cloud computing keeps pulling more of the world’s activity into data centers that must be connected by fiber. 5G increases the need for fiber backhaul compared to prior wireless generations. And rural broadband initiatives extend fiber into areas that used to rely on copper or fixed wireless. Different programs, same physical requirement: more glass, more miles, more connections.

Corning’s other segments round out the portfolio—and they’re not random. They’re the same core capability, expressed in different end markets.

Life sciences sells laboratory products and technologies to pharmaceutical and biotechnology customers, tracing back to the laboratory glassware roots that paralleled Pyrex. It’s less splashy than phones and fiber, but it provides steadier demand and ties Corning to the long-term growth of biomedical research and production.

Environmental technologies produces ceramic substrates and filter products used in emissions control systems for gasoline and diesel vehicles. It’s another example of Corning’s knack for turning deep materials expertise into industrial-scale components that quietly sit inside huge markets. As emissions regulations tightened across regions, demand for sophisticated substrates stayed resilient.

Specialty materials includes Gorilla Glass and other advanced materials applications—the high-margin cover glass business catalyzed by Apple, plus newer uses in areas like automotive and aerospace.

Across all of it, the through-line hasn’t changed in 170-plus years. Corning wins when it can do two things at once: invent materials competitors can’t easily copy, and manufacture them at a level of quality and scale that’s equally hard to replicate. The products have changed—from Edison’s bulbs to Jobs’s iPhone—but the advantage is the same.

That advantage shows up in the company’s financial profile. With $13.1 billion in revenue in 2024 and strong free cash flow, Corning has the capacity to keep funding research and development while also investing in growth areas like fiber manufacturing and new product development.

If you want a simple way to track whether the Corning machine is still working, two metrics tell much of the story. First: optical communications growth, because it’s the biggest and most strategically important business and a direct read on the pace of global fiber buildouts. Second: R&D intensity—the roughly 10% of revenue Corning has historically put back into research. That number isn’t a footnote. It’s the cultural promise Corning has kept for more than a century: keep learning the material, and the markets will keep coming.

XI. Bull Case: The Inevitable Bandwidth Future

The optimistic thesis for Corning starts with a pretty simple premise: the world’s appetite for moving data isn’t slowing down. If anything, it’s accelerating. Every trend that dominates the tech conversation—AI, cloud computing, autonomous systems, virtual and augmented reality, the Internet of Things—ultimately cashes out in the same requirement: more information moving faster, more reliably, across greater distances.

And when it comes to moving information, physics has favorites.

Fiber optics carries data as pulses of light through glass strands thinner than a human hair. Compared to copper, fiber loses less signal over distance and can move vastly more data in the same physical footprint. These aren’t features that come and go with product cycles. They’re structural advantages rooted in the underlying behavior of light and glass. That’s why the bull case treats fiber’s dominance as less of a “trend” and more of an inevitability.

Seen through that lens, Corning looks less like a component supplier and more like infrastructure. A kind of quietly embedded toll booth for the information economy: when network operators, cloud providers, and governments expand connectivity, a meaningful share of that build-out runs through Corning’s core products.

You can see the demand vectors stacking up. As 5G expands, the wireless part is only the last few hundred yards. The rest is fiber backhaul connecting towers to the network. As data centers proliferate, they need dense fiber inside the facilities and high-capacity fiber links between them. As broadband reaches deeper into suburbs, small towns, and rural regions, it requires fiber to neighborhoods, businesses, and homes. Different projects, different budgets, same recurring need: more glass in the ground and more connections lit up.

The bull case doesn’t stop at fiber. Gorilla Glass sits on its own, more consumer-facing demand curve—but it’s still driven by durability and platform spread. Smartphones remain a massive installed base with regular upgrades. And the surface area for toughened glass is expanding beyond phones: foldables and flexible designs, automotive infotainment displays, and AR headsets all pull for stronger, thinner, more damage-resistant materials. Corning’s head start in ion-exchange strengthened glass—and the manufacturing scale it built to serve customers like Apple—remains a real advantage as those categories evolve.

From a competitive strategy perspective, Corning also maps neatly to several of Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers—the kinds of advantages that can persist for a long time.

Process Power is the obvious one. Corning doesn’t just know the chemistry. It knows how to manufacture at extreme tolerances, at high yield, at massive scale—whether that’s optical fiber, display substrates, or cover glass produced under brutal timelines. Competitors can understand the principle. Reproducing the capability is the expensive, time-consuming part.

Counter-Positioning shows up in who would have to chase Corning to compete. Traditional glassmakers built for commodity volume would need to remake themselves to win in high-spec, high-purity, process-sensitive markets. That kind of shift isn’t just difficult. It threatens existing profit pools and demands organizational muscle memory they may not have.

Cornered Resource is Corning’s institutional knowledge—concentrated in places like Sullivan Park and reinforced by continuity. The teams that built expertise in one era trained the teams that defined the next. That kind of accumulated, intergenerational know-how is not something a competitor can simply buy with a hiring spree.

Scale Economies matter too. In businesses like optical fiber and display glass, unit costs improve with volume. Corning’s leading positions let it run larger production footprints and spread fixed costs across more output, reinforcing its ability to price competitively while still funding the R&D engine.

Finally, the bull case leans on something Corning has demonstrated repeatedly: it can survive transitions. This is a company that moved from railroad lantern globes to Edison bulbs to TV glass to fiber optics to smartphone cover glass—and stayed relevant in each era. So the optimistic view is that whatever the next materials constraint turns out to be, Corning’s playbook—deep science plus hard-to-copy manufacturing—gives it a credible shot at being the one to solve it.

XII. Bear Case: Cyclicality, Competition & Concentration Risk

The skeptical thesis for Corning is that the very qualities that make it great—big bets on capacity, deep exposure to tech build-outs, and a handful of enormous customers—can also set it up for sharp drawdowns. This company has created incredible value over the long arc. But along the way, it has also proved it can destroy shareholder value fast when a cycle turns.

Start with the core issue: telecom infrastructure spending is famously cyclical. Corning lived the nightmare version of that in the early 2000s, when the dot-com bust helped drive its stock to around $1 per share. Demand didn’t glide down; it fell off a cliff as network operators slammed the brakes. The worry is that today’s enthusiasm—5G rollouts, cloud growth, broadband upgrades—can eventually run into its own saturation point. And when telecom capex cycles down, Corning’s Optical Communications segment, now the company’s largest, is the one that tends to feel it first and feel it hardest.

Then there’s concentration risk. Gorilla Glass is a Corning success story, but it’s also tied to Apple’s choices. If Apple ever moved to alternative materials, shifted volumes to another supplier, or simply ran into a period of weak iPhone demand, Corning would feel it in a very real way. The same pattern exists in fiber: optical communications depends on the capex decisions of a relatively small set of large network operators. When a few big customers pause spending at the same time, it doesn’t matter how good your product is—your quarter just got rough.

You can also see the tension in Porter’s Five Forces. On the supplier side, Corning isn’t boxed in—many raw inputs are widely available, and the company’s real edge is process and know-how. But on the buyer side, power is substantial. In display glass and cover glass, customers are huge, sophisticated, and price-sensitive, with plenty of incentive to negotiate aggressively.

Substitutes depend on the segment. In fiber, there’s no real replacement for moving massive bandwidth over distance; physics is doing Corning a favor there. In displays, though, the picture is murkier. Glass is still the standard, but the category is more vulnerable to material shifts and changing manufacturing approaches over time.

New entrants are constrained by complexity—these are hard businesses to learn—but they’re not impossible. Well-capitalized Asian competitors have steadily improved their capabilities. And that leads to the most visible competitive pressure point: display technologies. Chinese and South Korean manufacturers have built serious capacity. Corning still has a lead, but the gap has narrowed, and pricing pressure has periodically squeezed profitability. If the display market stays oversupplied, or if competitors keep closing the quality and yield gap, Corning’s economics can get worse even if demand remains healthy.

There’s also geographic and geopolitical risk. Corning’s manufacturing footprint and many customer relationships are tied to specific regions. Trade policy shifts, political tensions, or localized disruptions can hit both supply chains and end-market demand in ways that are hard to hedge—and often impossible to time.

Another bear argument goes straight at the heart of the Corning identity: R&D. Spending roughly 10% of revenue on research is extraordinary for an industrial company. The bull case calls that the moat. The bear case asks what happens if the returns fade. If competitors can replicate innovations faster than they used to, or if incremental progress in materials science becomes harder and less commercially meaningful, then that R&D intensity starts to look less like an advantage and more like a structural cost problem.

And finally, there’s the reminder that Corning’s near-death experience isn’t some distant, academic case study. The company that looked unstoppable in 2000 was scrambling to survive by 2002. Management has been more disciplined since then, but the underlying exposure hasn’t disappeared: Corning still invests heavily in capacity to serve markets that can swing from boom to bust. If you’re underwriting Corning, you’re underwriting not just the brilliance of its science—but the volatility of the cycles it serves.

XIII. What Corning Teaches About Corporate Longevity

Corning has survived and stayed relevant for more than 170 years—long enough to span the Civil War, two World Wars, the Great Depression, the rise of the automobile, the space race, the internet, and the smartphone. Plenty of companies have lasted that long on paper. Almost none have done it while repeatedly ending up at the center of whatever technology wave came next.

So what’s the trick? Corning’s history doesn’t give you one magic answer. It gives you a playbook.

First: patient investment in fundamental capability. The Houghton family’s early conviction—that understanding glass would matter more than simply producing it—became a permanent advantage once Corning formalized research in 1908. Year after year, the company kept funding R&D at a level that signaled commitment, not experimentation. That created something that could outlive any one product cycle: a growing base of materials knowledge that could be applied again and again. When one market matured, Corning didn’t need a brand-new identity. It needed a new application for the same underlying competence.

Second: manufacturing is not an afterthought. Corning didn’t just discover low-loss optical fiber; it learned to make it at scale, with consistency, and with yields that competitors struggled to match. And in the Steve Jobs moment, the challenge wasn’t merely “can you make a strong glass?” It was “can you make an ocean of it, quickly, and without defects?” In Corning’s world, discovery creates the possibility. Manufacturing turns the possibility into a business.

Third: let innovations sit on the shelf until the world catches up. Chemcor is the perfect example. As an automotive windshield, it was a costly failure—killed not by physics, but by industry incentives and timing. A different kind of company might have buried the entire line of work and moved on. Corning kept the knowledge. Decades later, when consumer electronics needed thin, tough, scratch-resistant glass in huge volumes, that “failure” turned into the foundation of Gorilla Glass. Optionality is hard to value in a spreadsheet. Corning built a culture that treated it as an asset anyway.

Fourth: diversify, but don’t drift. Corning has operated in a lot of markets, but it hasn’t wandered randomly. It stayed anchored to what it’s uniquely good at: advanced materials, engineered for demanding use cases, produced with difficult-to-copy processes. That focus also made it willing to exit even beloved or high-profile businesses when they stopped fitting. It sold off consumer products when retail brands were no longer the best home for its advantage. It backed away from photonics when the market and the strategy didn’t align. Entering new arenas is important. Knowing when to leave is just as important.

Fifth: continuity compounds. Corning has stayed headquartered in Corning, New York for more than 150 years. That kind of geographic stability is rare—and it’s not just sentimental. It helps preserve institutional memory: the process tricks, the hard-won lessons, the quiet expertise that never makes it into documentation but shows up in yields and reliability. When companies constantly reshuffle leadership, locations, or organizational structure, they often shed the very knowledge that makes them good.

The iPhone story compresses all of this into one clean snapshot. Steve Jobs demanded a material that wasn’t sitting in mass production. Corning could say yes because it had decades of relevant science to draw on, because it could translate lab work into manufacturing reality under pressure, because it had kept “failed” technology alive long enough for the right market to arrive, and because its R&D culture stayed aimed at fundamentals rather than one-off product hacks.

None of this guarantees the next 170 years. The products that drive Corning today—optical fiber, display glass, Gorilla Glass—will mature. Some will be disrupted. The real question is the same one it has faced repeatedly since the 1800s: can Corning spot the next materials constraint early, and can it build the manufacturing to meet it before someone else does?

History argues for cautious optimism. Corning has already proven it can pivot across eras, not once, but repeatedly—because it never stopped compounding the underlying advantage. From Amory Houghton’s early bet on specialty glass, to Edison’s bulbs, to Pyrex, to Palomar, to fiber optics, to the iPhone, the pattern holds: deep materials understanding opens doors that shallow competence can’t even see.

In a world where technology cycles keep accelerating and advantages decay faster, that depth may be the most durable moat of all.

Sources

- Corning Incorporated annual reports and SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q)

- Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson (Simon & Schuster, 2011)

- Corning Museum of Glass historical archives

- The Palomar Observatory by Ronald Florence (Penguin, 1994)

- National Inventors Hall of Fame inductee profiles: Robert D. Maurer, Donald Keck, and Peter C. Schultz

- Corning company presentations and investor day materials

- Industry publications on fiber optics and telecommunications infrastructure

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music