HEICO Corporation: The Aerospace Parts Rebel That Built a $40 Billion Empire

I. Introduction & Cold Open

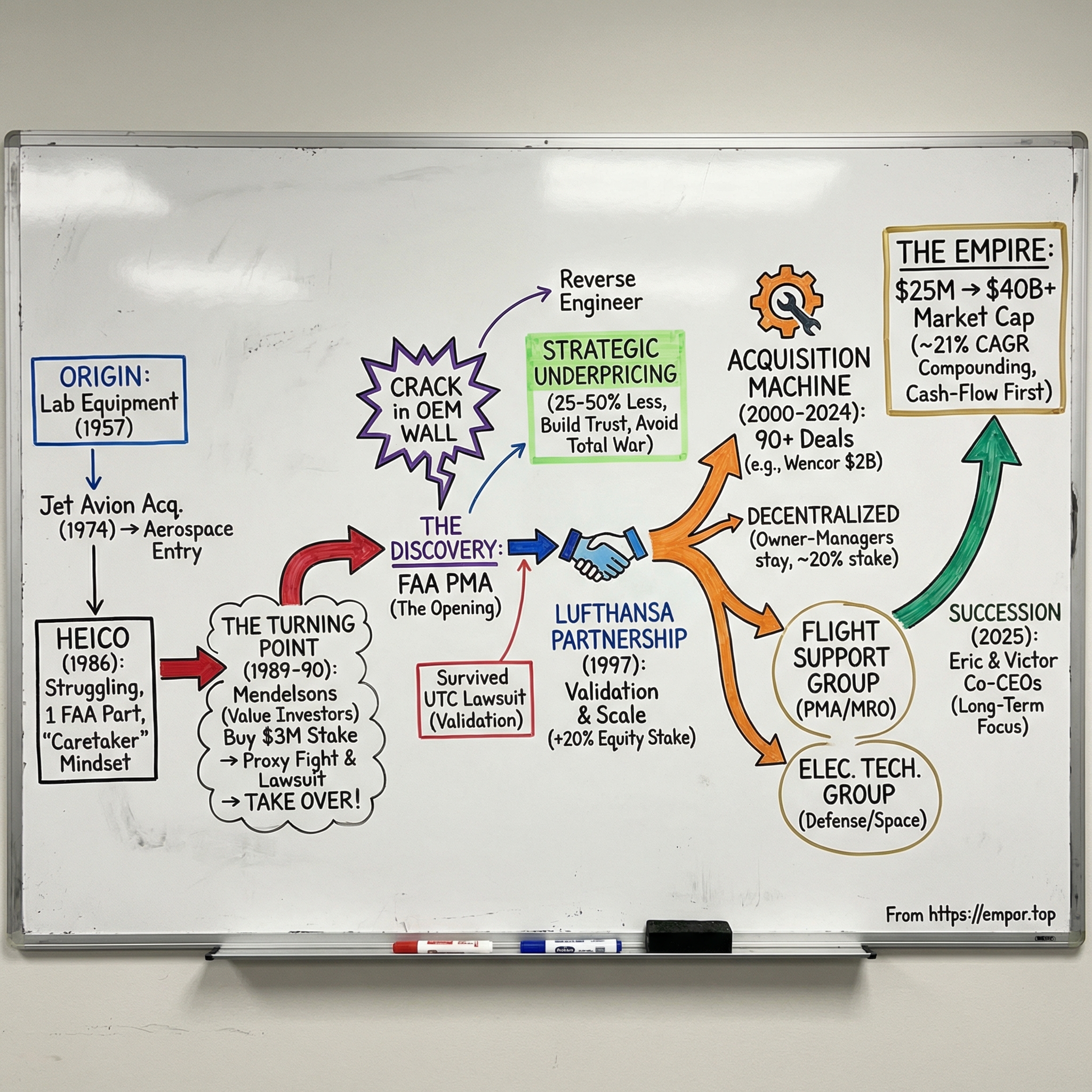

Picture the scene: it’s 1990, and in a modest factory in Hollywood, Florida, a company called HEICO makes exactly one FAA-certified replacement part. One. The business is struggling, the people running it don’t seem particularly invested, and the aerospace giants—Boeing, GE, United Technologies—own the aftermarket with near-total control and all the pricing power that comes with it. Airlines complain about being held hostage to OEM parts, but what are they supposed to do? In aviation, the regulatory walls around safety aren’t just high. They’re the whole game.

Then a family from South Florida shows up—father and two sons, all Columbia University grads—with a value-investing mindset, about $3 million, and a conviction that sounds almost naive: somewhere inside the FAA approval process and the sprawling aerospace supply chain, there’s a small opening. Not a loophole big enough for a quick win. A crack big enough to build a career, a company, and eventually an empire.

Fast forward to today. That single Hollywood factory has turned into dozens of facilities across 19 countries. That one FAA-certified part has grown into more than 200,000 products, with hundreds of thousands more potential parts still sitting on the menu. And that initial $3 million stake has compounded into a company worth more than $40 billion. The Mendelson family—Laurans, and his sons Eric and Victor—didn’t just revive a sleepy manufacturer. They built one of the most remarkable family-controlled compounders in American aerospace.

The question at the center of this story is deceptively simple: how does a family-run company take on the aftermarket dominance of industrial behemoths like Boeing, GE, and Honeywell—and not only survive, but keep winning for more than three decades?

The answer is a mix of regulatory know-how, deliberate underpricing, and a decentralized acquisition engine—plus the kind of patient, cash-flow-first capital allocation that’s become rare in a quarterly-obsessed public market. This is the story of how the Mendelsons turned an obscure company with roots in laboratory equipment into a powerhouse of aerospace aftermarket parts and services, completing more than 90 acquisitions along the way.

What makes this story special isn’t only the numbers—though the numbers are absurd. It’s the philosophy. In an industry where players like TransDigm became famous for aggressive pricing and financial engineering, HEICO took a different route: build trust with customers, price in a way that keeps the ecosystem stable, and buy businesses without smothering what made them great. They left money on the table—and somehow turned that restraint into their most durable advantage.

II. The Origins: Laboratory Equipment to Aerospace (1957-1990)

In 1957, Dwight Eisenhower was in the White House, Sputnik was about to rattle American confidence, and a small manufacturer called Heinicke Instruments Company opened its doors. There was no grand aviation ambition here. Heinicke made laboratory equipment—precise, practical instruments used in research and industrial testing. The kind of business that can run for years without making headlines.

And that’s exactly what it did. For nearly two decades, Heinicke stayed in its lane, selling into a steady, unspectacular market. Then, in 1974, it made a move that—at least on paper—looked like a sharp left turn: it acquired Jet Avion Corporation and stepped into aerospace.

At the time, the connection wasn’t obvious. What does lab equipment have to do with jet engines? But that acquisition mattered. It was the first hint that the company’s future might be bigger than bench-top instruments and testing devices. A seed, planted early, that wouldn’t fully sprout for years.

In 1986, the company renamed itself HEICO Corporation, a public signal that it was leaning into this new identity. The goal was to build a business in the aerospace aftermarket—designing and manufacturing FAA-approved replacement parts, plus repair solutions for aircraft components. The thesis made sense. Airlines spend enormous amounts to keep planes flying, and the original equipment manufacturers had what amounted to a chokehold on replacement parts, with all the pricing power that implies.

But a good thesis doesn’t pay the bills. Execution does. And in the late 1980s, HEICO’s execution was, at best, uninspired. The company stayed small. Results were disappointing. The strategy didn’t turn into momentum.

The core issue was incentives. The leadership team running HEICO didn’t have meaningful ownership in the business. So they behaved like caretakers: keep the lights on, collect the paycheck, avoid big bets that might fail. In companies like this, drift becomes the default strategy.

That caretaker mindset showed up everywhere—in performance, in urgency, and in how the market viewed the company. By the end of the decade, HEICO was modest in scale, low on profits, and completely unexciting to Wall Street. The stock was depressed, ignored, and unloved.

For most companies, that’s the setup for a long, quiet decline.

For HEICO, it was the setup for a takeover—because three Columbia graduates from South Florida were watching closely, and they believed the market was missing what could be built here.

III. The Mendelson Acquisition: Wall Street Meets Miami (1989-1990)

Laurans Mendelson was an accountant by training and an investor by instinct. He’d built a successful career in South Florida, but his investing DNA was forged at Columbia University, where he studied the Graham-and-Dodd school of value investing. Buy businesses for less than they’re worth. Insist on a margin of safety. Think like an owner. And have the patience to wait while everyone else gets bored.

His sons, Victor and Eric, didn’t just pick up the vocabulary. They picked up the mindset. Victor, the older brother, became fascinated with buyouts—the idea that the right company, mismanaged and misunderstood, could be transformed by better leadership and smarter capital allocation. Eric brought a complementary strength: the kind of operational focus that turns an investment thesis into an actual business.

Together, the three operated like a family investment committee, constantly hunting for situations where the market price and the underlying reality had drifted far apart.

In the late 1980s, Victor heard about a small public company called HEICO from a stockbroker. On paper, it fit the Graham-Dodd checklist: a depressed stock, an interesting niche, and a problem that didn’t look structural so much as self-inflicted—management that didn’t seem particularly motivated to build. Victor and Eric brought it to Laurans. He looked at it through the same lens he’d learned at Columbia and agreed: this one was worth pursuing.

So they started buying.

Quietly, over time, the Mendelsons accumulated roughly 15% of HEICO on the open market for about $3 million. That was a real bet for a family, but not nearly enough to control the company outright. If they wanted to change HEICO, they’d need other shareholders to join them. Which meant one thing: a proxy fight.

They went after the board, trying to replace the incumbent leadership and take stewardship themselves. It was the classic small-company control battle—scrappy, political, and personal. And when the votes were counted, it looked like the Mendelsons had lost.

But the family didn’t buy it.

They dug in and found irregularities in the proxy process. And instead of walking away—like most investors would, exhausted by the time, cost, and uncertainty—they escalated. Laurans, Victor, and Eric took the fight to court.

The case dragged on. It burned energy and money. It would have been an easy moment to decide this was becoming more trouble than it was worth. But the Mendelsons weren’t tourists. They had conviction, and they were willing to be uncomfortable if that’s what it took to own something for the long term.

In 1990, they won. The court ruled in their favor, and the Mendelsons finally took control of HEICO.

Step back and appreciate the absurdity of what they’d just fought for: a struggling aerospace company with a single FAA-certified part and a factory in Hollywood, Florida. This wasn’t a glamorous prize. It was a platform—one that would only matter if they could build it into something bigger.

Once they were in, the three Mendelsons set the rules of the game. Major decisions would be unanimous—no one could outvote the others. They would optimize for long-term value, not short-term optics. And they weren’t doing this for a quick flip; they were building for future generations.

That wasn’t a mission statement. It was an operating system. And now that they owned the keys, they faced the real question: what, exactly, was HEICO going to become?

IV. The FAA Aftermarket Discovery: David vs. Goliath (1990-1997)

To see what the Mendelsons saw, you have to understand the strange economics of the aerospace aftermarket.

When Boeing or Airbus sells an airline a plane, that purchase is only the opening act. Over the next few decades, the airline spends far more keeping that aircraft flying—maintenance, repair, overhaul, and a constant stream of replacement parts. And for years, the original equipment manufacturers—Boeing, GE Aviation, Honeywell, and others—captured most of that spend.

That’s where the real pricing power lived. Airlines might negotiate hard on the upfront aircraft deal. But once the plane entered service, options narrowed fast. If you needed a specific engine part—say, a combustion liner for a GE engine—GE was effectively the only source, and it priced like it. Aftermarket margins were often extraordinary, frequently above 50% and sometimes far higher.

Airlines hated it. They complained about being gouged. They organized purchasing groups. They hired lobbyists. But very little changed, because aviation isn’t like consumer goods. You can’t just find a cheaper supplier on the internet and give it a try. Every part that goes on a commercial aircraft has to clear FAA approval, and for a new manufacturer that process was expensive, slow, and uncertain.

And that’s the crack the Mendelsons were looking for.

The FAA had a designation called PMA—Parts Manufacturer Approval. It allowed a company other than the original manufacturer to make replacement parts, as long as it could prove the part was equivalent in form, fit, and function. The requirements were intense: testing, documentation, and a level of rigor that scares off most would-be entrants. But it was doable.

The OEMs had little reason to encourage it; their aftermarket businesses were too profitable. And third-party manufacturers were deterred not just by the regulatory hurdle, but by something else: the expectation that if you started to matter, you’d get dragged into a fight with opponents who had far deeper pockets.

The Mendelsons decided to lean into that fight anyway. They bet HEICO on PMA, starting with a single component: a combustion chamber for jet engines. It wasn’t random. Engine parts were expensive, carried meaningful pricing premiums, and wore out on a predictable schedule. If you could get certified, you didn’t need huge market share to make the effort worthwhile—and demand wouldn’t be a one-time event.

Inside HEICO, the engineers reverse-engineered the part, built the manufacturing process to meet FAA standards, and pushed the application through. It took months. The testing was unforgiving. The paperwork was relentless. But they got their approval. HEICO had its first PMA replacement part.

Then came the moment that would reveal whether this was a clever engineering project or the foundation of a business: what do you charge?

The Mendelsons didn’t do the obvious thing. They didn’t come in 10% or 15% cheaper than the OEM and call it a day. They priced their part at 25% to 50% below the original equipment price.

It sounds like a simple discount. It wasn’t. It was strategy.

At that level, airlines couldn’t ignore it. The savings were too large to wave away with, “We’ve always bought from the OEM.” At the same time, the pricing sent a message to potential PMA competitors: even if you fought your way through FAA approval, the easy money was already gone. And most importantly, the Mendelsons understood they were operating under a ceiling set by giants. If they took too much share too fast, the OEMs would be forced to respond—through lawsuits, lobbying, or pricing tactics designed to crush a newcomer.

So HEICO left room. Airlines got meaningful savings, but the OEMs still owned most of the market. The company positioned itself as a relief valve, not a revolution.

The OEMs noticed anyway.

In the mid-1990s, United Technologies, the parent of Pratt & Whitney, sued HEICO over its PMA business, alleging patent infringement and trying to shut it down. For HEICO, this wasn’t a nuisance. It was existential: a small company staring down an industrial giant with vast resources and an army of lawyers.

The Mendelsons fought back. They argued PMA was a legitimate, FAA-recognized pathway. They defended their engineering work as original. And they insisted the case wasn’t really about protecting innovation—it was about protecting aftermarket pricing power.

The litigation dragged on, draining time, money, and attention. But HEICO prevailed. The suit was resolved in HEICO’s favor, and the company came out the other side with its PMA business intact—and, crucially, with its right to compete validated.

That win did more than save the business. It made HEICO real.

Airlines saw that this new supplier could survive the pressure campaigns. They saw that PMA parts weren’t a regulatory gray area that would disappear after a threatening letter. In an industry where credibility is everything, HEICO was building it the hard way: one part, one approval, one customer at a time.

V. The Lufthansa Partnership: Validation and Scale (1997-2000)

By the mid-1990s, HEICO had shown that PMA wasn’t just a regulatory curiosity. It could be a real business. The catalog of approved parts was growing, customers were buying, and the company had survived a brutal legal test from United Technologies.

But the Mendelsons still faced a bottleneck that wasn’t solved by engineering or pricing: trust.

Airlines didn’t just need to believe a PMA part was cheaper. They needed to believe it was truly equivalent to the OEM component—and that betting their fleet on a new supplier wouldn’t come back to haunt them. In a safety-first industry, credibility is currency. And the fastest way to earn it is to borrow it from someone who already has it.

That’s why they set their sights on Lufthansa.

Lufthansa wasn’t just a big airline. It was a technical authority. Its maintenance organization was world-class, its standards were famously unforgiving, and its reputation for engineering rigor traveled farther than its routes. If Lufthansa validated your parts, the rest of the industry paid attention.

The courtship wasn’t quick. Victor and Eric Mendelson spent years building relationships with Lufthansa’s technical leadership, showing up again and again—Frankfurt, Miami, wherever the next meeting had to happen. They didn’t pitch with hype. They walked Lufthansa through the work: the engineering process, the documentation, the testing, the FAA requirements. They came armed with details, not slogans.

The message was simple and practical. PMA parts could cut maintenance costs materially without compromising safety, because every part still had to clear the same FAA approval bar for form, fit, and function. The difference wasn’t the standard. It was the price.

In 1997, Lufthansa made a move that turned heads across aerospace. It didn’t just agree to buy HEICO’s PMA parts. It bought a 20% equity stake in HEICO’s PMA business.

That single decision changed HEICO’s trajectory.

For one, Lufthansa opened up a level of operational insight HEICO couldn’t have gotten any other way. With access to Lufthansa’s technical priorities and maintenance experience, HEICO could see where the pain really was: which parts drove the most cost, which failed most often, and which ones would matter most if they could be approved. Instead of guessing, HEICO could aim its engineers at the highest-impact targets.

Just as important, the partnership changed the risk profile of product development. FAA approval took time and money, and before Lufthansa, every new PMA project carried a question mark at the end: after all that effort, who would actually buy it? Now HEICO had a committed customer waiting on the other side of certification. That made it easier to invest, plan, and build a pipeline.

But the biggest impact was reputational. Lufthansa’s stake functioned like a seal of approval money couldn’t purchase. Other airlines evaluating HEICO now had to reckon with a powerful signal: if Lufthansa’s engineers trusted these parts enough to invest, why wouldn’t they at least take a serious look?

This also revealed something core about the Mendelsons’ style. They didn’t approach Lufthansa like a vendor trying to close an account. They approached it like a long-term partner, and they structured the relationship to align incentives. Lufthansa wasn’t just buying parts; it had skin in the game. If HEICO failed to deliver, Lufthansa would feel it as an owner.

After the Lufthansa deal, adoption accelerated. The PMA business stopped looking like a scrappy outlier and started looking inevitable. HEICO’s original thesis—there was a crack in the aftermarket wall—was no longer something the Mendelsons had to argue. The industry could see it. And HEICO was already climbing through it.

VI. The Acquisition Machine: Building an Empire (2000-2024)

By 2000, the PMA business had momentum. The flywheel was finally turning: more FAA approvals, more airline wins, more credibility. At that point, the straightforward play would have been to keep doing exactly that—pour money into engineering, expand the catalog, add capacity, and grow the parts business the traditional way.

The Mendelsons didn’t ignore organic growth. They just saw a bigger opportunity.

They believed HEICO’s real edge wasn’t a single part or even PMA itself. It was a repeatable skill set: navigating regulation, earning trust with demanding customers, allocating capital with discipline, and running businesses without strangling them with corporate bureaucracy. If those advantages were real, then HEICO didn’t have to be only a PMA company. It could be a buyer of many great small-to-mid-sized businesses across aerospace, defense, electronics, and adjacent industrial markets—and make them better simply by being the right owner.

So they built an acquisition machine.

Since the 1990s, HEICO completed more than 90 acquisitions. Some were small, targeted purchases that added a specific capability or product line. Others were bigger moves that pulled HEICO into entirely new categories. Together, they transformed the company from a niche aftermarket upstart into a diversified aerospace-and-defense platform.

The dealmaking, though, never looked like the typical roll-up playbook.

The Mendelsons’ Graham-and-Dodd instincts showed up in the kinds of companies they wanted and the prices they were willing to pay. They weren’t chasing flashy trophy assets. They looked for businesses with strong competitive positions, talented management, and solid economics—especially cash flow. They didn’t need heroic synergy forecasts to justify a deal, and they avoided transactions that depended on perfect growth assumptions.

But the most distinctive part of the strategy wasn’t the screening process. It was what happened after the ink dried.

HEICO didn’t buy companies to “integrate” them into some centralized operating system. It bought them to keep them excellent. The acquired businesses usually stayed autonomous. Their management teams stayed in place. Their names often stayed on the door. Decisions remained with the people closest to the products and customers.

And the Mendelsons added an incentive twist that made this model unusually sticky: they typically had the owner-managers keep a 20% stake in the business they sold. So the founder didn’t just take a check and disappear. They stayed on as an operator with meaningful ownership—still motivated, still accountable, and still thinking like a builder.

That structure attracted a very specific kind of seller: not someone desperate to exit, but someone who wanted liquidity and a long-term partner without giving up the thing they’d spent years creating. For HEICO, it meant entrepreneurial energy stayed inside the building instead of walking out on closing day.

Over time, this created something like a federation: dozens of specialized businesses, each running with its own rhythm, but all benefiting from HEICO’s capital, relationships, and long-term mindset. It wasn’t a franchise, and it wasn’t a traditional conglomerate either. It was looser and more trust-based—designed to preserve what made each company work in the first place.

As the portfolio expanded, HEICO organized itself into two major divisions. The Flight Support Group housed the aftermarket roots—PMA parts and related maintenance, repair, and overhaul activity. The Electronic Technologies Group became the home for a growing set of electronic components and subsystems serving aerospace, defense, space, and industrial customers.

This is where the story stops being “HEICO makes cheaper replacement parts” and starts becoming “HEICO quietly touches an enormous amount of modern aerospace.” With each acquisition, the company added technical depth, customer access, and new lanes to grow into. HEICO wasn’t just reverse-engineering parts anymore. It was building electronics and systems that mattered across defense and space, and it was finding more places in the value chain where reliability, certification, and trust created durable advantage.

In 2023, HEICO announced its largest acquisition ever: the $2 billion purchase of Wencor. Wencor was one of the largest independent distributors of aircraft replacement parts, with a broad catalog and deep relationships with airlines around the world. For HEICO, it was a scale move—bringing distribution strength and additional market reach that complemented what the company had already built.

Just as importantly, the Wencor deal was proof that the acquisition engine didn’t slow down as HEICO got bigger. The company still had the balance sheet capacity, the management discipline, and the operating model to take on a transaction of that size without abandoning the decentralized approach that had worked for decades.

Today, HEICO runs manufacturing operations in 19 countries, with facilities spanning places like the Netherlands, Thailand, India, Canada, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. And the product set now stretches far beyond jet-engine parts—into airframe components, avionics, electronic warfare, and space-related applications. The company that once hung its future on a single FAA-certified part became a global industrial empire by doing the unglamorous thing, over and over: buying great businesses, keeping the builders in charge, and compounding patiently.

VII. The Business Model: Pricing, Culture & Capital Allocation

Once you win FAA approval, the temptation is obvious: push price. The barriers are high, switching is painful, and in the aftermarket, urgency is constant. That logic—charge what the market will bear, because customers don’t have great alternatives—is exactly what turned TransDigm, HEICO’s closest public-market comparable, into one of the most profitable businesses in aerospace.

The Mendelsons didn’t run HEICO that way.

From the beginning of the PMA effort, HEICO priced many parts roughly 25% to 50% below the OEM. That was more aggressive than they needed to be to get airlines’ attention, and far below what the regulatory moat might have allowed. With the difficulty of FAA approval limiting competition, HEICO could have aimed for eye-watering margins—40%, 50%, even higher. Instead, they tended to operate with something closer to 15%.

It’s easy to mistake that for leaving money on the table. The Mendelsons saw it as buying something more valuable than margin: a durable position in the ecosystem.

The underpricing did a few things at once. First, it made airlines feel like HEICO was on their side. Not a vendor squeezing them, but a partner helping them take real cost out of maintenance. And in an industry built on long cycles and trust, that matters. If you save an airline meaningful money year after year, you stop being a line item and start being a relationship. When HEICO showed up with a new FAA-approved part, customers listened. And once they’d built confidence, they had less reason to shop around.

Second, it managed the political risk. If HEICO had priced just under OEM levels while taking huge share, it would have forced the giants to respond. OEMs have a lot of tools—legal action, lobbying, bundling, contract pressure—to make life miserable for an upstart. HEICO’s approach kept the temperature lower. They were a competitive nuisance, not an existential threat. In that posture, the cost and distraction of a full-scale counterattack didn’t always pencil out for the incumbents.

Underpricing, in other words, wasn’t charity. It was long-term positioning. The Mendelsons were optimizing for a company that could compound for decades, not for the best possible quarter. They treated reputation and trust as strategic assets—real value creators that simply don’t show up on financial statements.

That same mindset shaped how they allocated capital.

“We don’t target the top line,” Laurans Mendelson has said. “We can do a trillion dollars in sales and make no money. We are focused on the bottom line and particularly cash flow. That allows us to keep low debt and keep compounding the earnings. It’s the power of compounding that has made us.”

It’s almost boring advice—until you notice how rare it is in public markets. Revenue growth is the headline. Cash flow is the engine. The Mendelsons cared far more about the engine, because cash flow is what lets you keep buying great businesses, keep investing through downturns, and keep your options open when the world gets messy.

That cash flow focus also explains HEICO’s conservatism around debt. While other acquirers leaned hard on leverage—either to juice returns or to fund buybacks—HEICO stayed relatively restrained. They carried less debt than they could have, kept flexibility for acquisitions, and avoided the kind of balance sheet that can turn a cyclical downturn into a loss of control.

And the ownership mindset didn’t stop with the Mendelsons. HEICO used equity compensation to spread ownership across the organization, creating thousands of employees with a direct stake in performance. Not symbolic participation—meaningful enough to affect behavior and retention. The point was cultural as much as financial: build a company where people make decisions like owners, because many of them actually are.

Put all that next to TransDigm and you get a clean contrast in philosophies. TransDigm is famous for aggressive pricing, financial optimization, and concentrated equity upside at the top. It produced spectacular shareholder results, but also recurring friction with customers and regulators. HEICO accepted lower margins in exchange for fewer enemies, stronger customer relationships, and a model designed to endure.

Neither playbook is automatically “right.” But HEICO’s track record suggests a counterintuitive lesson: sometimes the money you don’t take—the margin you intentionally give up—is exactly what buys you the longevity to compound into something enormous.

VIII. The Numbers: From $25M to $40B+

Numbers don’t lie. But without context, they can still mislead—especially when the story you’re trying to tell is compounding. HEICO’s results are so outsized that they can sound like a lucky break or a once-in-a-generation fluke. They weren’t. They were the predictable outcome of a very specific way of running a business, repeated year after year.

Start with what the Mendelsons actually bought in 1990. HEICO was doing about $25 million a year in revenue. It was barely profitable, largely ignored by Wall Street, and so small in the aerospace world that it barely registered. It wasn’t an “aerospace powerhouse in distress.” It was a tiny public company with a niche idea and a lot to prove.

Fast forward to fiscal 2024, ending October 31. HEICO reported $3.86 billion in annual revenue, up nearly 30% from the prior year. Profitability hit record levels too. In the fourth quarter alone, net income rose 35% to $139.7 million, or $0.99 per diluted share.

Over the full arc—from the 1990 takeover to today—sales compounded at about 15% per year. Net income compounded at about 18%. And the stock delivered roughly 21% annualized returns. That’s the kind of performance that turns a $3 million stake into something measured in billions—not through a single breakout moment, but through decades of steady execution.

And that’s the key distinction. This isn’t the venture-capital pattern where one huge win makes up for a pile of losses. This is one company, compounding for roughly 35 years across multiple cycles: booms and busts, recessions and recoveries, geopolitical shocks and a pandemic. The headline is the magnitude. The real story is the consistency.

Put it in everyday investor terms and it gets almost absurd. A $10,000 investment at the time of the Mendelson takeover would have grown to more than $4 million. Put that same $10,000 into the S&P 500, and you’d have something closer to $250,000. HEICO didn’t just beat the market. It lapped it—by about sixteen times.

That compounding shows up in the company’s scale too. HEICO’s market capitalization climbed from effectively “small and obscure” to more than $40 billion, making it one of the largest aerospace suppliers in North America. It also earned a spot in the S&P 500—meaning it became a default holding for index funds and institutions, not because it was trendy, but because it got too big to ignore.

So what actually drove the numbers?

At the simplest level, it was three forces working together: organic growth, disciplined acquisitions, and time.

Organic growth came from doing the unsexy work: expanding the PMA catalog, earning repeat business, and riding the long-term tailwind of a growing global fleet. Every plane delivered created decades of future maintenance demand. Every hour flown pulled parts through the system. The aftermarket didn’t need hype—it grew as a function of physics and utilization.

Acquisitions added new products, new customers, and new lanes to grow in. And because HEICO focused on profitable businesses and sensible prices, those deals tended to contribute to earnings quickly. Over decades, the cumulative effect of more than 90 acquisitions turned HEICO into something far larger—and more resilient—than the original PMA play could have become on its own.

But the real advantage, the one that’s hard to copy, was time. Fifteen percent growth in a single year is nice. Fifteen percent sustained over a generation is transformative. The Mendelsons built a structure—family control, conservative leverage, cash-flow-first thinking—that let them stay patient and avoid the kinds of mistakes that break compounding.

That’s how you get from a $25 million business with one FAA-certified part to a $40 billion company. Not by swinging for the fences once. By getting on base for decades.

IX. Leadership Transition & The Next Generation (2020-Present)

If there’s a graveyard for great companies, a lot of the headstones read the same: succession.

The founder builds something extraordinary. The next generation can’t—or won’t—run it the same way. Alignment fractures, culture thins out, and the thing that made the business special gets replaced with politics, entitlement, or short-termism. The statistics are brutal: fewer than 15% of family businesses make it to the third generation.

The Mendelsons have been planning around that problem for a long time. And in 2025, they moved HEICO into its next chapter. Laurans Mendelson—the patriarch who steered the company for 35 years—announced he would step down as Chief Executive Officer effective May 1, 2025. His sons, Eric and Victor, would succeed him as co-CEOs, while keeping their existing roles as co-presidents.

On paper, “co-CEOs” can sound like an awkward compromise. Most companies want a single person at the top, one voice with final authority. Split the role, and you invite the obvious fears: confusion, turf wars, and decision paralysis.

At HEICO, though, it wasn’t a new experiment. It was a formal label for how the company had actually been run.

Eric and Victor had operated as a team for decades. Eric focused on the Flight Support Group—HEICO’s aftermarket roots, including PMA parts and related operations. Victor led the Electronic Technologies Group, the fast-growing portfolio of electronics serving aerospace, defense, space, and industrial customers. They routinely coordinated on major calls, leaned on each other’s domain expertise, and kept faith with the unanimous-decision principle the family set when they took control in 1990.

In other words, the “transition” was less a shift in power than an acknowledgement of reality. Laurans, now in his eighties, had been stepping back from day-to-day involvement. Eric and Victor—seasoned executives in their sixties—had effectively been running the place for years. The title change made it official.

But titles aren’t the hard part. Culture is.

What HEICO is really trying to protect through succession isn’t a job description. It’s an operating system: cash-flow discipline, conservative debt, decentralized autonomy, and the instinct to play the long game—even when the short game looks tempting. The Mendelsons have tried to bake that philosophy into how HEICO hires, pays, promotes, and buys companies so that it doesn’t depend on any single person staying in the building forever.

The third generation is already in the mix. Eric’s and Victor’s children work in various roles across HEICO and its portfolio companies, learning the business from the ground up rather than being dropped into executive chairs. Whether they eventually lead the company is an open question, but the intent is clear: this is a family that’s thinking in decades, not quarters.

There’s also a practical upside to the co-CEO setup. It builds redundancy at the top. If anything happened to either Eric or Victor, the other could keep the machine running without the scramble that can rattle a family-controlled business. For shareholders, that kind of continuity matters—especially in a company where the culture has been as central to the compounding as the strategy itself.

X. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

HEICO’s story is a masterclass in building something that lasts—and the lessons travel well outside aerospace. Strip away the jet engines and the FAA paperwork, and what you’re left with is a repeatable way of creating long-term value.

Finding niches within niches. Aerospace is massive, but the Mendelsons didn’t try to battle the giants everywhere. They picked one narrow wedge—PMA parts—inside one profit pool—the aftermarket—inside one highly regulated industry—commercial aviation. That focus let HEICO build the kind of specialized know-how, credibility, and customer relationships that generalists struggle to replicate. The takeaway for founders: big markets help, but real advantage often comes from being obsessively specific.

The power of patient capital and family ownership. Because the Mendelsons controlled HEICO and thought in decades, they could make moves that would look “wrong” to a quarterly-optimized management team. They could underprice to earn trust. They could invest in regulatory capability that took years to show up in results. They could pass on deals that didn’t meet their standards, even when the market was cheering for growth at any cost. In HEICO’s case, family control wasn’t just a governance detail—it was a strategic weapon.

Decentralized operations with centralized vision. HEICO showed you can build something big without turning it into a bureaucracy. The acquired companies largely kept their autonomy, while corporate leadership stayed focused on the few things that truly benefit from central control: capital allocation, long-term direction, and cultural guardrails. That only works if you genuinely trust the people you buy—and HEICO’s structure, often leaving owner-managers with meaningful ongoing ownership, helped make that trust durable.

Strategic underpricing as competitive moat. HEICO deliberately left margin on the table. Not because it couldn’t charge more, but because it understood what the margin was buying: loyalty from airlines, credibility in a safety-first market, and less incentive for new entrants to fight through the FAA process just to discover the profits had already been competed away. It also kept HEICO from triggering all-out retaliation from OEMs. The broader lesson: sometimes your moat is the profit you don’t take.

Acquisition integration without destroying culture. Many serial acquirers eventually break their own model—either the integration workload becomes unmanageable or the very entrepreneurs they bought lose the energy that made the businesses special. HEICO avoided that trap by keeping management in place and keeping incentives aligned. It gave up some classic “synergies,” but protected the intangible assets—relationships, craft, speed, pride of ownership—that actually drive performance over long periods.

Playing second fiddle strategically. HEICO didn’t need to “win” the aftermarket to thrive in it. It stayed customer-friendly on pricing, kept market share modest, and avoided backing the OEMs into a corner where they’d be forced to respond with everything they had—legal, political, and commercial. It’s a subtle lesson in competitive strategy: sometimes the smartest move is to position yourself so you can compound without ever becoming the main target.

Regulatory expertise as barrier to entry. The FAA approval process is painful. That’s the point. In unregulated markets, anyone can show up and compete on price. In regulated markets, the real competition is capability: documentation, testing, quality systems, and the institutional muscle memory to do it repeatedly. The Mendelsons treated regulation not as a tax, but as a barrier they could learn to climb faster—and more reliably—than others. Over time, that capability became one of HEICO’s most defensible assets.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case & Future Outlook

The Bull Case

The runway in front of HEICO still looks long. Even after three decades of steady expansion, PMA parts remain a relatively small slice of the overall aerospace aftermarket. Airlines are still under constant pressure to cut maintenance costs, and HEICO keeps widening its catalog of approved parts. Every time the FAA signs off on a new component, HEICO doesn’t just add a product—it adds another recurring stream of demand tied to aircraft that will be flying for years.

Beyond commercial aviation, HEICO has built real exposure to defense and space. Military aircraft need the same unglamorous, continuous maintenance as commercial fleets, and the geopolitical environment has pushed defense budgets higher across NATO countries and their allies. At the same time, space launch has moved from rare event to regular cadence, with commercial operators like SpaceX accelerating the need for the kinds of specialized electronics and components that sit inside HEICO’s Electronic Technologies Group.

Then there’s the acquisition engine. Aerospace remains a fragmented industry, full of niche suppliers that are excellent at what they do but would benefit from a long-term owner with capital and patience. The Wencor acquisition showed HEICO could do a deal at meaningful scale without abandoning its disciplined, decentralized model. If anything, it signaled that the company still has room to keep consolidating—possibly with more large transactions over time.

Finally, governance is part of the bull case. Public investors rarely get true long-term alignment, but HEICO has it. Eric and Victor Mendelson have stayed committed to the playbook their father built, and the third generation is already being developed inside the organization. That kind of multi-decade mindset is unusual in public markets—and when it works, it’s a competitive advantage you can’t buy off the shelf.

The Bear Case

The biggest structural risk is still the one HEICO was born into: OEM power. Boeing, GE, and their peers have tolerated HEICO’s rise, but there’s no rule that says they always will. If HEICO pushed too far, too fast, the incumbents have levers—lawsuits, lobbying for regulatory shifts, and commercial tactics like bundling—that could make competing in the aftermarket meaningfully harder. One specific threat is the industry’s move toward longer-term service agreements between OEMs and airlines, which can effectively pre-package maintenance and parts in ways that leave less room for independent suppliers.

Technology is the slower-moving bear case. Newer aircraft and engines tend to be more reliable, which can mean less frequent maintenance and fewer replacement cycles over time. And while electric or hybrid propulsion remains a long-dated scenario for large commercial fleets, any major shift in aircraft architecture would eventually reshape the aftermarket economics HEICO has been compounding within. These are changes that would likely take decades to fully play out—but for long-term investors, they’re not ignorable.

There’s also valuation. HEICO traded at premium multiples relative to the broader market and many aerospace peers, reflecting its quality and its history of compounding. The risk is straightforward: when you pay a premium for a great business, you’re also paying for a lot of future success in advance. If growth slows or margins compress, the market can take some of that premium back, which can weigh on returns even if the business remains strong.

And then there’s succession—beyond the current generation. Eric and Victor have been central stewards of HEICO’s culture and operating model, but no leadership team lasts forever. The third generation hasn’t yet been tested at the very top. Eventually HEICO will face a transition to leaders who weren’t there for the early PMA battles, the Lufthansa validation, or the formation of the acquisition model. That moment will test whether HEICO’s culture is truly institutional—or still, in part, inherited.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

The industry structure that made HEICO possible hasn’t fundamentally changed. Supplier power is moderate: HEICO can source from multiple vendors and generally isn’t hostage to a single critical input. Buyer power is meaningful because airlines are sophisticated and price-sensitive, though the customer base is spread out enough that no single buyer dominates. The threat of new entrants is low because certification and quality systems create real barriers. Substitutes are a longer-term question—more relevant when aircraft technology shifts than in any near-term purchasing cycle. Rivalry is most intense with OEMs, who historically have chosen periods of accommodation rather than all-out confrontation.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

HEICO’s durability shows up in several of Helmer’s power sources. Scale economies matter, especially in manufacturing and in regulatory work, where fixed compliance costs get spread across a broader and broader catalog. Switching costs exist in practice: once an airline has validated parts and built them into maintenance routines, changing suppliers creates friction and risk. Process power is a major advantage—decades of accumulated know-how in FAA approval, documentation, and quality systems compound into a capability that newcomers can’t replicate quickly. And the company’s family ownership and governance create a form of “cornered resource” in the sense that competitors can’t copy that alignment or time horizon.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For investors watching whether the HEICO playbook is still working, a few signals matter most:

-

Organic revenue growth in Flight Support Group. This is the clearest read on the core aftermarket engine: are the PMA and related businesses gaining share and growing on their own, separate from acquisitions?

-

Operating cash flow conversion. HEICO has always emphasized cash flow over accounting optics. Strong conversion supports the story that earnings quality remains high; deterioration is a warning sign.

-

Acquisition pace and post-deal performance. HEICO’s compounding has been heavily acquisition-driven, but only because the deals tend to work. Watch whether deal flow remains steady and whether acquired businesses hold up—especially margins and operational stability—after joining the HEICO umbrella.

XII. Epilogue: What Would You Do?

In 1990, the Mendelsons paid about $3 million for roughly a 15% stake in a struggling aerospace company with one FAA-certified part and a lot more uncertainty than promise. They fought through a proxy battle and then a lawsuit. They built a strategy that deliberately didn’t squeeze every last dollar of margin. They assembled a decentralized empire through more than 90 acquisitions. And over roughly 35 years, they compounded at about 21% annually.

So the question isn’t whether what they did was extraordinary. It’s whether anything like it can keep happening from here.

If you asked the Mendelsons, they’d probably give you the same answer they’ve lived by: don’t get hypnotized by the next quarter. Stay patient. Keep the balance sheet strong. Protect the culture. Keep doing the unglamorous work that compounds. But the uncomfortable truth for any investor is that the future never looks exactly like the past. Technologies shift. Regulations evolve. Competitive behavior changes. And aerospace, for all its conservatism, is still a moving target.

There are obvious reasons for optimism. International expansion remains a real opportunity. HEICO already operates in 19 countries, but the center of gravity for air travel keeps spreading—especially across parts of Asia and the Middle East, and over time, Africa. Airlines there face the same basic math: planes fly, parts wear out, and OEM pricing stings. PMA alternatives can help. The capability exists. The question is execution at scale, across more customers, more regulators, and more operating environments.

There are also new arenas beyond traditional commercial aviation. Urban air mobility—flying taxis and delivery drones—may still be early, but if it matures, it will create an aftermarket of its own. Space launch is already picking up cadence, with commercial demand playing a bigger role than it used to. And defense electronics continue to benefit from global military modernization. HEICO’s portfolio is already positioned in and around several of these currents.

But could HEICO really do another 100x over the next 30 years? That’s the kind of number that sounds fun to say and almost impossible to justify. A 100x from here would imply a roughly $4 trillion market cap—HEICO as one of the largest companies on Earth. A more grounded version of the question is the one that actually matters: can HEICO keep compounding at meaningfully better-than-market rates without breaking the very habits that made the compounding possible?

Because the Mendelsons’ edge was never one trick. It was a way of operating: patience when patience was unfashionable, discipline when leverage was easy, and relationships when squeezing customers would have been the faster path. They proved that in a world optimized for quarterly results, thinking in decades can create remarkable value.

Now comes the part every long-running compounding story eventually faces. As leadership and ownership shift further into the next generation, the test won’t just be whether HEICO finds new markets or new products. It’ll be whether it can keep its operating system intact—and whether the aerospace aftermarket continues to reward the kind of gentle rebels who found a crack in the wall and quietly built an empire through it.

XIII. Recent News

By fiscal 2024, HEICO wasn’t just executing the playbook—it was putting up record results across the board. Net income hit an all-time high, capped by a fourth quarter that grew 35% year over year. Management credited the performance to strong demand in both of its main engines—the Flight Support Group and the Electronic Technologies Group—along with the steady absorption of recent acquisitions, including Wencor.

That Wencor deal, which closed in 2023 for about $2 billion, quickly looked like more than just a “biggest-ever” headline. It gave HEICO real distribution muscle and broadened the catalog—especially in the everyday hardware and consumables that sit right next to the company’s core parts business. Just as notably, management said Wencor was outperforming expectations, the kind of statement that matters when you’ve just spent that much capital.

In early 2025, HEICO also made official what had been true in practice for years: Eric and Victor Mendelson would succeed their father as co-CEOs. Investors took it as continuity, not a shake-up—more a formal handoff than a changing of the guard. Laurans Mendelson stayed involved as Executive Chairman, keeping the family’s long-term stewardship firmly in place.

The broader backdrop has been supportive too. Air travel continued its recovery from the pandemic-era shock, pushing more aircraft hours through the system—and more parts through maintenance cycles. At the same time, rising defense budgets in the U.S. and allied countries created additional demand signals for the Electronic Technologies segment. For HEICO, it’s the kind of environment where the model tends to look obvious in hindsight: planes fly, systems wear, budgets get spent—and the quiet, certified suppliers keep compounding.

XIV. Links & Resources

Company Filings and Investor Presentations - HEICO Corporation SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, 8-K) - HEICO Investor Relations website - Annual reports and proxy statements

Industry Reports and Analysis - FAA Parts Manufacturer Approval (PMA) program documentation - Aviation Week Intelligence Network reports - Oliver Wyman Global Fleet & MRO market forecast

Historical Articles and Profiles - “The Mendelsons: Building an Aerospace Empire One Part at a Time” — Forbes - “HEICO’s Quiet Conquest of the Aerospace Aftermarket” — Bloomberg Businessweek - “Family Business Lessons from HEICO Corporation” — Harvard Business School case studies

Academic Papers - “Family Ownership and Long-Term Value Creation” — Journal of Finance - “Decentralized Conglomerates and Capital Allocation” — Strategic Management Journal - “Regulatory Barriers as Competitive Advantage” — Harvard Business Review

Competitor Analysis - TransDigm Group annual reports - AAR Corp investor materials - Barnes Group aerospace segment analysis

Regulatory Resources - FAA Parts Manufacturer Approval (PMA) advisory circular - Code of Federal Regulations: Title 14, Part 21 - EASA guidance on alternative parts approval

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music