Hilton Worldwide: The Architecture of Hospitality Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Overview

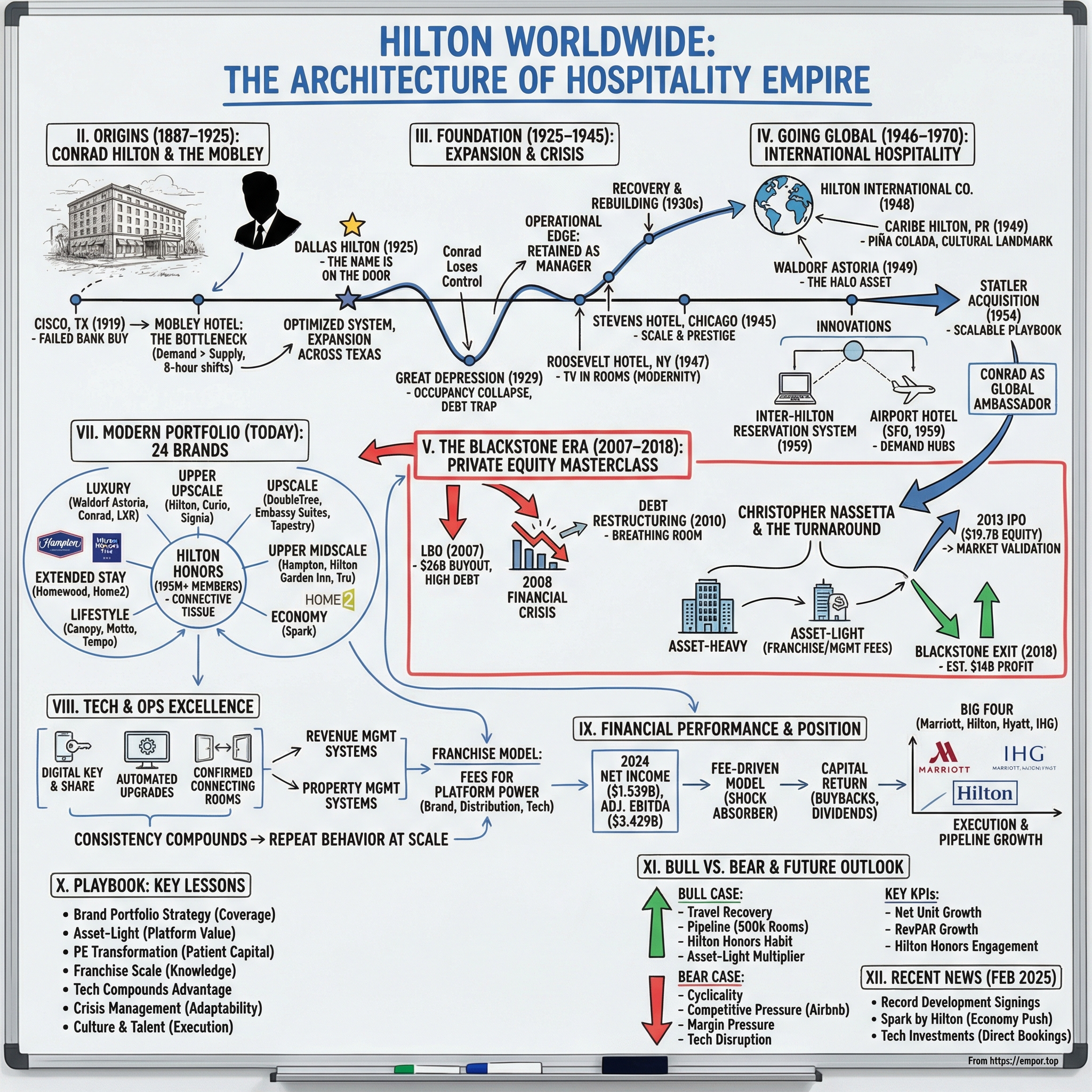

Picture the lobby of the Waldorf Astoria on Park Avenue in 1949: soaring ceilings, Art Deco glamour, and the low, constant murmur of diplomats, dealmakers, and movie stars drifting through what was, for a time, the unofficial palace of New York City. Somewhere in that scene stood Conrad Hilton—a lean, sharp-eyed Texan—fresh off what he considered the most important purchase of his life. He called the Waldorf “The Greatest of Them All.”

Three decades earlier, he’d walked into a dusty hotel in Cisco, Texas, with an entirely different plan. He was there to buy a bank. Instead, he walked out owning a forty-room hotel. That wrong turn became a blueprint.

Today, Hilton Worldwide is one of the defining institutions of global hospitality: 24 brands, more than 8,800 properties, and nearly 1.3 million rooms across 139 countries and territories. In 2024, the company earned $1.539 billion in net income and generated $3.429 billion in Adjusted EBITDA. You can feel the Hilton footprint almost anywhere travel happens—budget road trips, business conferences, airport overnights, once-in-a-lifetime resort splurges.

But the interesting question isn’t “How did Hilton get so big?” It’s “How did Hilton learn to change?”

How did a small-town Texas hotel purchase turn into the modern playbook for hospitality? How did a company that almost got wiped out by the Great Depression—and then nearly got wiped out again in the 2008 financial crisis—come back both times sharper, more resilient, and ultimately more valuable? And how did Blackstone pull off what many view as the signature private equity turnaround of its era—turning a $26 billion buyout into an estimated $14 billion profit?

Hilton is really three stories braided together. First, the origin story of Conrad Hilton: an American saga of ambition, faith, and relentless forward motion. Second, the operational revolution that turned hotels from an art into a replicable science—standardization, systems, and consistency at scale. Third, the financial reinvention that transformed an asset-heavy real estate empire into an asset-light fee machine that others would race to copy.

Along the way, we’ll hit the inventions and inflection points that defined the industry: early reservations systems, televisions in guest rooms, the rise of the airport hotel, and the loyalty engine that keeps customers coming back.

At its core, this is a story about patience. The kind that lets you hold through a crisis. The kind that builds brands over decades, not quarters. And the kind of leadership—most notably under CEO Christopher Nassetta—that understands a simple truth about hospitality: consistency compounds.

II. Origins: Conrad Hilton & The Mobley Hotel (1887–1925)

San Antonio, in Socorro County of the New Mexico Territory, wasn’t exactly the obvious starting line for a future global hospitality empire. But on Christmas Day in 1887, Augustus Halvorsen Hilton—a Norwegian immigrant who’d Americanized his name—welcomed a son into the world. They named him Conrad Nicholson Hilton.

Augustus made his living the way a lot of people did in the Southwest then: by being useful. He ran a general store, and as traffic moved through town—travelers, ranchers, miners—he did what frontier entrepreneurs always did. He added rooms. He let people stay above the store. It was commerce, but it was also hospitality, and Conrad grew up watching the simple mechanics of it: provide shelter, charge fairly, treat people well enough that they’d come back.

His mother, Mary Genevieve Laufersweiler, brought a different force into the home. She was a devout Catholic of German descent, and Conrad absorbed that certainty. For the rest of his life, he credited faith with guiding his decisions. This wasn’t just a public persona; people around him recalled him praying on his knees before major negotiations. In a business built on risk and timing, Hilton moved with the confidence of someone who believed he wasn’t making the journey alone.

Before hotels, though, he tried politics. From 1912 to 1916, Hilton served as a Republican representative in the first New Mexico Legislature—ambitious, young, and convinced he could do something meaningful. Instead, he got a close-up view of how power actually works. The backroom deals and quiet bargaining wore him down. “Politics,” he later said, “was full of inside deals.” He decided he’d rather build something than barter over it.

Then World War I interrupted everything. Hilton served in the Army. And when he came home in 1919, he went looking for his fortune in the place where fortunes were suddenly being made: Texas. He arrived in Cisco with a plan that sounds almost quaint now—he was going to buy a bank. The postwar economy was roaring, oil was remaking the region, and banking felt like the cleanest way to turn growth into wealth.

But Cisco had other ideas. The bank’s owner raised the price beyond Hilton’s reach. Frustrated, he checked into the only real place to stay in town: a forty-room hotel called the Mobley.

And the Mobley wasn’t a hotel so much as a bottleneck. Cisco was jammed with oilmen and workers, and the lobby churned with people begging for rooms. Beds were rented in eight-hour shifts—one man slept, rolled out, and another slid in. The building was throwing off cash, but the owner looked defeated. Demand was relentless. The operation was exhausting. He wanted out.

That moment became the Hilton origin story for a reason. Conrad had come to buy a bank. Instead, he bought the Mobley for $40,000, mostly borrowed. Then he did something that would define him: he treated the place like a system to be optimized. He converted unused space—lobby corners, storage areas—into more rooms. He leaned into the eight-hour cycle and made it part of the business model. The Mobley started earning like a machine.

It also taught him his real edge. Hilton didn’t just spot demand; he spotted mismanagement. The previous owner had the same building, the same crowds, the same boomtown economics. What he didn’t have was the instinct to turn chaos into repeatable process.

Over the next several years, Hilton reinvested and borrowed his way across the Texas oil patch, picking up more hotels and learning fast. Each property sharpened the playbook: location mattered more than charm; occupancy was oxygen; reputation could be leveraged; operations could be standardized.

By 1925, he was ready to put his name on the door. That year, he opened the first hotel formally called a Hilton, in Dallas—a symbolic step that made his ambitions public.

The banker in Cisco who priced Hilton out likely never gave the episode another thought. But that one deal redirected Conrad Hilton from vaults and ledgers to lobbies and guest registers. And once he found the business, he never really left it. The hotel titan era had begun.

III. Building the Foundation: Expansion & Innovation (1925–1945)

The Dallas Hilton in 1925 was more than a name on a marquee. It was Conrad Hilton signaling a shift—from opportunistic buying to deliberate building. Over the next five years, he opened a new Texas hotel every year. By 1930, he’d stitched together eight properties through a mix of acquisitions and new construction, turning “Hilton” into a regional promise: you knew what you were getting.

Then October 1929 hit, and that promise nearly went with it.

When the Great Depression took hold, occupancy collapsed. The debt that had powered Hilton’s expansion—so manageable in boom times—turned into a trap. He surrendered properties to creditors and watched hotels he’d fought to build slide out of his control. At his lowest point, he was borrowing money from bellhops just to eat. For a man wired for momentum, it was a brutal reversal.

But Hilton still had the one thing no lender could repossess: he was the best operator in the room.

Even as ownership changed hands, banks and investors understood that the hotels worked better with Hilton running them than without him. So instead of pushing him out, they kept him on—managing a combined chain of properties he no longer owned. It was humbling, even humiliating. Hilton treated it as tuition. He learned, up close, what happens when leverage turns on you. It’s a lesson that would echo decades later when a different set of owners found themselves staring down their own debt-fueled crisis.

Through the 1930s, he rebuilt the only way he knew how: methodically. He cut costs, tightened operations, and waited for the tide to turn. He leaned hard on faith, later describing those years as a test he intended to pass. By the end of the decade, he had regained control of his remaining hotels—and, more importantly, he’d rebuilt confidence that he could expand again without being wiped out by the next downturn.

The 1940s were the pivot from regional player to national force. As the economy recovered and demand returned, Hilton expanded west to California and east to Chicago and New York. These weren’t small bets. They were statement moves—properties chosen to announce that “Hilton” belonged in America’s most important cities.

The signature acquisition was Chicago’s Stevens Hotel, then the largest in the world, with more than 3,000 rooms. Hilton bought it in 1945 and renamed it the Conrad Hilton. That wasn’t just vanity. It was branding before “branding” was a business obsession: his name was now tied directly to scale, prestige, and a standard he expected to be repeatable.

That repeatability became Hilton’s real differentiator. He began building an operational playbook—standardizing how hotels ran, from front-desk routines to housekeeping rhythms. He wanted a guest to walk into any Hilton and feel the same competence, the same polish, the same reliability. In an era when hotels were often one-off expressions of whoever happened to own them, Hilton was building something closer to a system. The industry would follow.

His New York purchase of the Roosevelt Hotel in 1947 showed the same instinct from a different angle: win by being early. He made it the first hotel in the world to put televisions in guest rooms—an expensive gamble on a technology that was still more novelty than necessity. But guests loved it, and the message landed: Hilton meant modern.

By the end of this stretch, Hilton had done something rare. He’d survived the Depression, clawed his way back, and emerged with a bigger ambition than before—now with a national footprint and a clearer sense of what made his hotels different. The next chapter wasn’t just more hotels. It was a new kind of travel—and Hilton was about to help build its infrastructure.

IV. Going Global: The Birth of International Hospitality (1946–1970)

In 1946, Conrad Hilton incorporated Hilton Hotels Corporation, giving his growing collection of properties a formal engine. Two years later, he took an even bigger swing: he created a separate entity, Hilton International Company, built specifically to plant the Hilton flag outside the United States. It was an audacious move for the era. International leisure travel was still mostly for the wealthy, and cross-border business travel was complicated and infrequent. Hilton was building for a world he believed was coming—before he could fully prove it was.

That world started to take shape with Hilton International’s first property: the Caribe Hilton in San Juan, Puerto Rico, which opened in 1949. It was a beachfront resort, yes—but it also became a kind of cultural landmark. In 1954, at the Caribe’s Beachcomber Bar, bartender Ramón “Monchito” Marrero blended rum, coconut cream, and pineapple juice over ice. He called it the Piña Colada. It would go on to become Puerto Rico’s official beverage and one of the most recognizable cocktails on the planet. In a small way, it captured what Hilton International was trying to do: not just export an American hotel experience, but create moments that traveled.

Back in New York, Hilton landed what he saw as the ultimate prize: the Waldorf Astoria on Park Avenue. He called it “The Greatest of Them All,” and he meant it. The Waldorf wasn’t simply a hotel—it was a stage for power. It was diplomacy and society and American prestige packaged into one address. Every president from Hoover onward kept a suite. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor lived there. When Hilton bought the Waldorf, he wasn’t just buying rooms and ballrooms. He was buying mythology.

And that purchase revealed a pattern Hilton would use for decades: secure an icon that elevates the entire brand, then use that halo to expand. The Waldorf was more than an asset. It was a statement—one that made “Hilton” synonymous with the top tier of hospitality.

Then came the deal that proved Hilton wasn’t only a showman—he was a consolidator. In 1954, he bought the Statler Hotel chain for $111 million, at the time the largest real estate transaction in history. The acquisition was a step-change: it doubled Hilton’s room count and gave the company powerful footholds in major cities like Boston, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C. Just as important, it was a test of whether Hilton’s operating system could travel—whether his playbook could be applied to hotels he didn’t build himself. The bet was that process and standards could unlock performance, even in inherited properties.

This era also produced one of Hilton’s most consequential innovations, even if it didn’t look glamorous from the outside. On August 15, 1959, Hilton introduced the Inter-Hilton Hotel Reservation System—the first multi-hotel reservations system in the industry. For the first time, a guest in one city could book a room in another with a single call and trust that the reservation would actually be there waiting. It’s hard to overstate how radical that was in a world of disconnected ledgers and local phone calls. It was the ancestor of every modern booking system—online travel agencies, brand websites, mobile apps—all of it.

In the same year, Hilton helped invent another travel ritual: the airport hotel. The company opened the 380-room San Francisco Airport Hilton in 1959, recognizing something obvious in hindsight but not at the time—air travel was about to reshape where demand lived. As jet travel expanded, proximity to transportation hubs became its own kind of prime real estate. The airport hotel, now a standard feature of every major city, began as a Hilton idea.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, Hilton’s international growth did more than generate revenue. It gave American companies and travelers a familiar outpost in unfamiliar places. As U.S. corporations expanded overseas and Cold War politics pulled business and diplomacy across borders, Hilton properties became a kind of informal infrastructure—conference rooms where deals got made, lobbies where relationships formed, and hotel bars where travelers found something that felt steady. Staying at a Hilton meant a reliable slice of American modernity, delivered with consistency, almost anywhere.

Conrad Hilton, meanwhile, became a public figure. His marriages—including to Zsa Zsa Gabor—made headlines, and his profile rose with the company. He appeared on magazine covers, testified before Congress about international business, and carried himself like an informal ambassador for American capitalism. The hotel business had made him famous. The international business made him global.

By 1970, Hilton had assembled the building blocks the industry would spend the next half-century copying: global reach, iconic flagship properties, scalable operations, and systems that made the whole thing run. But as the founder aged, a new question began to hover over the empire he’d constructed: could Hilton keep evolving without the man who’d willed it into existence?

V. The Blackstone Era: Private Equity's Masterclass (2007–2018)

By 2007, Hilton had become a strange contradiction: one of the most recognizable names in travel, but not one of the sharpest operators. It owned a lot of real estate, moved slowly, and had watched competitors like Marriott and Starwood win growth in areas Hilton had helped define. Then Blackstone arrived—Stephen Schwarzman’s private equity juggernaut—with a plan that would become either a disaster in the making or the turnaround story of the era.

On July 3, 2007, Blackstone announced it would buy Hilton for $47.50 a share, a 40 percent premium to the prior day’s close. The deal valued Hilton at $26 billion, making it the largest hotel transaction ever completed at the time and one of the biggest leveraged buyouts of the pre-crisis boom. The structure was the tell: about $5.7 billion of equity from Blackstone, and $20.8 billion of debt piled onto Hilton’s balance sheet. This wasn’t leverage as a tool; it was leverage as a thesis.

Then the world broke.

Within about eighteen months of the deal closing, Lehman Brothers collapsed, credit markets seized, and the global economy slid into its worst downturn since the 1930s. Travel dried up. Hotel occupancy fell hard. And that debt—perfectly manageable in a rising economy—started to look existential.

Blackstone ended up writing down its Hilton investment by 71 percent. For critics, it was the textbook private equity comeuppance: a peak-of-the-cycle buyout, financed too aggressively, now headed for the rocks.

But what followed flipped the story.

Instead of capitulating, Blackstone negotiated. In 2010, it executed a debt restructuring that became a case study in how to survive when the math stops working. Blackstone repurchased $1.8 billion of mezzanine debt at a 54 percent discount, effectively paying about 46 cents on the dollar. It also converted junior mezzanine loans into preferred equity, taking roughly $3.5 billion of debt off Hilton’s balance sheet. And as interest rates collapsed, Hilton benefited from the Federal Reserve’s near-zero policy, saving an estimated $700 million a year in debt service.

That bought Hilton breathing room. But breathing room isn’t value creation. It’s time. And Blackstone needed Hilton to do something meaningful with it.

That’s where Christopher Nassetta came in. Blackstone had brought him in specifically to run a turnaround, and he went straight at what he believed was the real problem. Hilton didn’t just have too much debt. It had the wrong business model.

Owning hotels is expensive, cyclical, and slow to scale. Every new property ties up capital and adds operating risk. Nassetta’s answer was to push Hilton toward an “asset-light” strategy—turning the company from a major hotel owner into a brand manager and franchisor. Hilton would still own the relationship with the guest: the brand, the standards, the reservation system, the loyalty program. But other people would own the buildings.

The shift happened fast. In 2007, Hilton owned or leased a meaningful portion of its properties. By 2013, about 92 percent of Hilton’s hotels were operating under franchise or management agreements. The economics changed with the structure: instead of spending billions to add rooms, Hilton could grow by signing owners and collecting fees for the right to fly the flag—plus additional fees tied to marketing, reservations, and loyalty.

The result was a company that could expand without dragging its balance sheet along for the ride.

Nassetta paired that model change with a broad operational tightening: higher brand standards, improved guest satisfaction, a faster development pipeline, and a growing loyalty program. He demonstrated something private equity critics often dismiss: when owners are willing to hold through pain and back a real operating plan, leveraged buyouts don’t have to be financial stunts. They can be catalysts.

Blackstone didn’t flip Hilton. It held for eleven years—through a near-death experience—and worked to turn an iconic but sluggish hotel company into a cleaner, faster, fee-driven platform. And that set the stage for the moment public markets would finally be asked a simple question: do you believe the new Hilton is real?

VI. The 2013 IPO & Public Market Return

On December 11, 2013, Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. returned to the public markets, listing on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker HLT. It wasn’t a quiet homecoming. The IPO was the largest ever for a hotel company at the time: about 117.6 million shares priced at $20, raising roughly $2.35 billion. In the process, it valued Hilton at $19.7 billion in equity value and $33.6 billion in enterprise value.

What made those figures land wasn’t just their size—it was what they said about the arc of the previous six years. Blackstone had bought Hilton in 2007 at a $26 billion enterprise value, then watched the global financial crisis punch a hole through travel demand and the company’s highly leveraged balance sheet. Yet here Hilton was, back in the spotlight, now worth meaningfully more than the price Blackstone paid. The public markets were effectively signing off on the core turnaround idea: the new, asset-light Hilton should be valued higher than the old, asset-heavy one.

Blackstone didn’t treat the IPO as an exit ramp. It treated it as the start of the exit. After the offering, the firm still owned 76.2 percent of the company—enough to keep control, but with a public float that let the stock establish itself. Over the next five years, Blackstone steadily sold down through secondary offerings, stepping back in stages as Hilton’s performance and credibility continued to build.

In May 2018, Blackstone sold its remaining shares and closed the book on an eleven-year hold. The result was the kind of outcome private equity firms pitch but rarely get: an estimated $14 billion profit on a $5.7 billion equity investment—about 2.5x invested capital—even after living through the worst downturn since the Great Depression.

For Wall Street, it forced a reassessment. The 2007 deal had been easy to mock as a peak-of-the-cycle buyout. And the timing really was brutal. But the Hilton outcome made a cleaner point: price matters, but execution matters more. Blackstone’s combination of financial engineering—most importantly the debt restructuring—and operational change created an entirely different company than the one it acquired.

The IPO was also a referendum on Christopher Nassetta’s strategy. Public market investors tend to reward clear, repeatable unit economics, and the franchise-heavy model delivered exactly that: a more capital-efficient Hilton, positioned to grow faster and with a margin profile that compared well to peers. The market wasn’t just buying a hotel operator. It was buying a fee-driven platform with global distribution, brand power, and a long runway for new signings.

And the ripple effects went beyond Hilton. The deal became a template the rest of the industry couldn’t ignore. Asset-light went from “strategy” to default setting. Franchising and management agreements became the core operating model for essentially every major hotel company that wanted scale without a balance sheet full of buildings.

But underneath all the mechanics—IPO pricing, secondaries, multiples—there was a simpler ingredient that made the whole story work: staying power. In 2009 and 2010, the easiest move would have been to concede defeat, hand over the keys, and walk away. Blackstone didn’t. It kept backing the company, kept working the capital structure, and kept believing that Hilton’s brand and operating potential were stronger than the cycle that had knocked it flat.

VII. The Modern Portfolio: 24 Brands & Strategic Positioning

Walk through a major airport, a downtown business district, or a beach destination almost anywhere in the world, and you’ll run into Hilton. Often, you’ll run into several Hiltons—different flags, different price points, different vibes—sometimes on the same block. That’s not coincidence. It’s the product of decades of deliberate portfolio construction, and it’s one of the most important reasons Hilton can keep growing without needing to own the buildings it grows into.

Today, Hilton spans 24 brands. Think of them as tools in a kit: each one designed for a specific traveler, a specific occasion, and a specific owner economics profile. The key to understanding modern Hilton is realizing it isn’t one hotel company. It’s a distribution system—brands, standards, reservations, loyalty—that can be deployed across almost any segment of demand.

At the top sits the luxury tier: Waldorf Astoria Hotels & Resorts, Conrad Hotels & Resorts, and LXR Hotels & Resorts. Waldorf Astoria is the prestige play—iconic, market-defining properties meant to be the signature luxury address wherever they operate. Conrad is luxury with a different posture: built for travelers who want high-end service and design without the pageantry. LXR is the soft-brand approach at the very top of the market, bringing independent luxury hotels into Hilton’s network while letting them keep their own identity.

Just below that is upper-upscale: Hilton Hotels & Resorts, the flagship and most widely recognized name; Signia by Hilton, built around meetings and events; and Curio Collection, another soft brand for upscale independents. These are the big, full-service hotels—restaurants, meeting rooms, and prime locations where both business and leisure demand overlap.

Then you hit the segment where Hilton wins on sheer volume. DoubleTree by Hilton is the most famous example, and yes, the warm chocolate chip cookie at check-in is doing real work. It’s a small ritual that makes the stay feel personal and memorable—an easy-to-repeat signature that turns a mid-tier hotel into something guests talk about. Embassy Suites brings an all-suite format with complimentary breakfast, while Tapestry Collection gives Hilton another way to attract independent upscale hotels that don’t want to be fully standardized.

In upper-midscale, Hilton’s growth engine really shows itself: Hampton by Hilton, Hilton Garden Inn, and Tru by Hilton. Hampton alone has more than 2,500 properties. Its proposition is almost aggressively simple: clean, consistent, reliable, and priced for everyday travel. That consistency becomes a moat. When guests know exactly what they’re going to get, decision-making gets lazy in the best way—people stop shopping and start defaulting.

Hilton also has a full set of extended-stay brands—Homewood Suites by Hilton and Home2 Suites by Hilton—built for trips that last four nights or longer, with kitchens and more residential amenities. Extended stay tends to hold up well because longer stays can be stickier and more predictable than one-night leisure travel.

On the other end of the spectrum are lifestyle and boutique plays—Canopy by Hilton, Motto by Hilton, and Tempo by Hilton—Hilton’s answer to travelers who want design-forward, experience-driven properties and might otherwise choose an independent boutique hotel or Airbnb.

And most recently, Hilton launched Spark by Hilton in the economy tier—an explicit move into a part of the market Hilton historically didn’t dominate. Spark is a bet that Hilton can take what it already does well—standards, distribution, and loyalty—and make it work for more price-sensitive travelers who previously had little reason to care about the Hilton ecosystem.

Holding the whole portfolio together is Hilton Honors. With approximately 195 million members, it’s one of the largest hotel loyalty programs in the world—and it acts like connective tissue between brands. Honors members are more likely to book direct, come back more often, and choose a Hilton flag even when the location or price isn’t perfect. That matters because it reduces reliance on online travel agencies and helps stabilize demand when the cycle turns.

For investors, the portfolio is also a risk-management machine. Different segments behave differently in a downturn, and Hilton operates across the spectrum. Growth opportunities also vary by geography: a brand that’s mature in the U.S. might still be early internationally. With 24 flags, Hilton can meet owners and guests where they are—and keep filling rooms across multiple kinds of travel, no matter what the economy is doing.

VIII. Technology & Operations Excellence

Hospitality has always been a technology business. Conrad Hilton understood that early—first by putting televisions in rooms at the Roosevelt Hotel, then by building a multi-property reservation system that let a guest book across cities with one call. The tools have changed. The job hasn’t. Hilton still wins by removing friction and making “reliable” feel effortless, from the moment you search to the moment you check out.

Start with what guests actually touch. Hilton’s Digital Key lets you skip the front desk and go straight to your room, using your phone as the key. Digital Key Share takes it a step further: you can send a working key to a spouse, your kids, or a colleague, so everyone isn’t stuck coordinating around one plastic card. On paper, that sounds like a convenience feature. In practice, it’s the kind of small, repeatable relief that changes where people prefer to stay—especially travelers who are tired, late, or traveling with others.

Hilton has also pushed into the kind of “quiet automation” guests don’t always notice until it’s missing. Automated complimentary room upgrades use systems to match eligible guests with better rooms when availability allows—without the awkward dance at check-in. And the ability to book confirmed connecting rooms online tackles a classic family headache: no more calling around, no more “we’ll note the request,” no more arriving and hoping the rooms are actually next to each other.

All of that is the front-end. The real advantage is the machinery behind it.

Hilton’s revenue management systems constantly tune pricing based on demand signals, booking patterns, and the competitive set—optimizing rates across an enormous volume of room-nights. Property management systems help standardize how hotels run day to day, so the experience at a Hampton in Omaha lines up with what you expect from a Hampton in Orlando. That consistency isn’t just brand polish. It’s how you earn repeat behavior at scale.

And it’s how the franchise model actually holds together.

When you don’t own most of the buildings, you can’t rely on direct control. Hilton’s hotels are largely owned and operated by third parties who license the brand. So Hilton enforces consistency through systems: required technology, documented operating procedures, and quality standards backed by regular inspections. The promise to the guest is “you know what you’re getting,” and the way you keep that promise—across thousands of owners—is process, measurement, and enforcement.

This is where the asset-light model becomes more than a financial strategy. It’s an operating philosophy.

In the traditional hotel business, growth means deploying massive capital: buy land, build a building, furnish it, staff it. Hilton’s approach shifts that burden to owners. Hilton brings the brand, distribution, technology, and operating playbook. The franchisee brings the capital, runs the property, and uses local market knowledge to make it work.

In return, Hilton collects fees—franchise fees tied to gross room revenue, marketing contributions, and additional fees for reservation systems and loyalty participation. The key point is that these fees aren’t dependent on whether a particular hotel is wildly profitable. Hilton gets paid for powering the platform.

That’s why the development pipeline matters so much. As of December 31, 2024, Hilton’s pipeline stood at 498,600 rooms, up 8 percent from the prior year. In the fourth quarter of 2024 alone, Hilton approved 34,200 new rooms for development. Each one is a future fee stream—another room that, once opened, can generate revenue for decades.

For long-term investors, that creates something rare: visibility. Hilton isn’t waiting on a single blockbuster product cycle. A meaningful portion of its future growth is already under contract and under construction. Even when the economy gets shaky, that pipeline functions like a forward map—showing where the next wave of earnings power is likely to come from, and why Hilton can keep compounding through the cycle.

IX. Financial Performance & Market Position

Hilton’s 2024 results are what the asset-light story looks like when it’s working. For the full year, net income came in at $1.539 billion, and Adjusted EBITDA—the yardstick hospitality investors tend to care about most—reached $3.429 billion. The fourth quarter kept that pace, with net income of $505 million and Adjusted EBITDA of $858 million.

Revenue was $11.2 billion for the year, but the more important point is what that number represents. Hilton isn’t a classic “own the building, fill the rooms” hotel company anymore. A large share of its business is fees from franchisees and managed properties: payments for the brands, the distribution engine, the reservation system, and the loyalty program. That’s why Hilton talks so much about system-wide RevPAR as a pulse check for the network, even though Hilton’s own earnings are driven more by fee streams and the size of the system than by the performance of any single property.

That structure is the company’s shock absorber. When travel demand drops, individual hotel owners take the first hit—occupancy falls, room rates soften, and profitability gets squeezed. Hilton feels it too, because fees are often tied to revenue. But Hilton doesn’t carry the same fixed burden of ownership: the mortgages, the property taxes, the ongoing maintenance capex. The model’s value showed up clearly during COVID-19, when industry conditions were catastrophic, yet Hilton’s earnings held up far better than the economics of owning hotel real estate.

With that steadier cash flow profile, capital return has become a major part of the playbook. In the fourth quarter of 2024 alone, Hilton repurchased 3.1 million shares. Total capital returned to shareholders, including dividends, was $781 million for the quarter and $3.0 billion for the full year. It’s a blunt signal from management: they believe the engine is durable enough to both fund growth and keep sending cash back to owners.

To understand Hilton’s market position, you have to place it in the modern “big four” of global hotel companies: Marriott, Hilton, Hyatt, and IHG. Marriott is the scale leader, and the Starwood merger in 2016 helped it build a portfolio of roughly 1.5 million rooms. Hilton is the clear number two—and the company argues its development pipeline gives it a path to close some of that distance over time. Hyatt is smaller and more weighted to luxury, often trading at higher valuation multiples. IHG—home to InterContinental, Holiday Inn, and Crowne Plaza—competes with Hilton across many of the same demand segments.

Hilton’s edge comes down to execution. It tends to lead or match peers on the measures that matter in an asset-light world: guest satisfaction, development pace, and franchisee retention. Hilton Honors has continued to expand faster than competing loyalty programs, a sign the brand is winning the fight for frequent travelers. And system-wide RevPAR growth has generally kept pace with, or exceeded, peers—evidence that the network is not just getting bigger, but staying relevant in the market.

When investors value hotel companies, they often lean on EBITDA multiples—especially because many traditional hotel owners have heavy capital needs and cyclical earnings. Hilton trades at a premium to most peers, and that premium is basically the market putting a price on the asset-light model: higher capital efficiency, stronger margins, and more visible growth through signings and the development pipeline. The bull case is that those qualities justify paying up. The bear case is simpler: when you’re priced for excellence, there’s not much room for a stumble.

X. Playbook: Key Business Lessons

The Hilton story isn’t just about hotels. It’s a set of business principles that show up everywhere—software, retail, media, even manufacturing. The product happens to be hospitality, but the playbook is broader.

Brand portfolio strategy creates durable advantage. Hilton’s 24-brand lineup isn’t complexity for its own sake. It’s coverage. Different flags let Hilton catch different trips, budgets, and moods—and keep the same customer inside the ecosystem over decades. Someone can start with a lower-cost stay at Tru by Hilton, graduate to DoubleTree for work travel, choose Embassy Suites for a family trip, and eventually book a special occasion at Conrad. One brand sells a room. A portfolio builds a lifetime relationship.

Asset-light beats asset-heavy—when you have the brand. Blackstone’s biggest move wasn’t a clever refinancing. It was pushing Hilton from owning buildings to owning the platform: brand standards, distribution, loyalty, and operating know-how. That shift created enormous value, but it only works if the flag is strong enough that owners will pay to fly it. The lesson isn’t “asset-light always wins.” It’s that asset-light wins when your intangible assets—trust, consistency, demand generation—are more valuable than the real estate.

Private equity creates value when it enables transformation. Leveraged buyouts get criticized for cost-cutting and short-termism. The Blackstone-Hilton deal is the counterexample people point to when they want to argue the best version of private equity: patient capital, a willingness to hold through a crisis, and the financial flexibility to change the business model instead of just trimming around the edges. Not every deal looks like this. But this one shows what’s possible.

Franchise systems scale knowledge. Hilton’s real product to owners is its playbook: the standards, training, systems, and procedures that make a Hampton in one city feel like a Hampton in another. Franchising turns that accumulated knowledge into a scalable engine. Hilton doesn’t need to fund every new building to grow. It gets paid—again and again—for packaging expertise into something other operators can execute.

Technology compounds competitive advantage. Hilton has a long history of using technology as an edge, from early TVs in rooms to digital keys today. The reason this matters is compounding: better digital tools improve the guest experience, increase direct bookings, generate more data, enable better personalization, and strengthen loyalty—which then feeds back into more demand for Hilton-branded hotels. Over time, tech leadership becomes less a feature and more a flywheel.

Crisis management separates survivors from victims. Conrad Hilton made it through the Great Depression by staying indispensable as an operator, even when ownership slipped away. Blackstone made it through the 2008 financial crisis by aggressively restructuring debt while still investing in operations. The common thread is clear: when the cycle turns, survival isn’t luck. It’s disciplined execution paired with the ability to buy time.

Culture and talent determine execution. The capital structure matters, the strategy matters—but it still comes down to people. Christopher Nassetta’s leadership made the asset-light vision operational: aligning franchisees, tightening standards, and communicating clearly with investors. Capital without capable management gets wasted. Capable management without capital gets boxed in. Hilton’s modern era worked because it had both.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case & Future Outlook

The bull case for Hilton starts with a simple idea: travel is still normalizing, and Hilton is built to capture that upside with far less capital than the old hotel business required. Leisure and business demand continued to recover from the pandemic era, and Hilton’s development pipeline—nearly 500,000 rooms—gives the company unusually clear line of sight into where growth can come from over the next several years, even if the near-term economy gets choppy. Layer on Hilton Honors, now approaching 200 million members, and you get something even more powerful than scale: habit. A huge base of travelers who don’t start every trip by shopping every option—they default to Hilton because it’s familiar and it works.

Management’s 2025 outlook reflects that confidence. Hilton projected system-wide RevPAR growth of 2–3 percent on a comparable and currency-neutral basis, with Adjusted EBITDA expected between $3.7 billion and $3.74 billion. The takeaway isn’t the exact range—it’s that Hilton expected to keep growing even as the “easy” post-pandemic rebound comparisons faded.

The asset-light model is the multiplier. As franchised and managed hotels raise rates and fill more rooms, Hilton’s fee income rises with them—without Hilton having to finance a wave of new buildings or take on the same level of property-level risk. In good environments, that structure tends to let earnings grow faster than the underlying system.

If you run Hilton through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, you can see why this machine strengthens as it expands. Scale economies show up in the centralized reservation system, loyalty platform, and brand marketing—capabilities an independent hotel simply can’t replicate cost-effectively. Network effects show up inside Honors: the more properties in the system, the more valuable the membership becomes, which attracts more members, which makes the brand more attractive to owners, which brings in more properties. Switching costs are real for franchisees who’ve invested in Hilton’s systems, training, and standards. And branding does what the best brands always do: it lowers the mental effort of choosing, and it can support rate premiums because the guest trusts the experience. Together, those advantages make Hilton’s platform more defensible at scale than a simple “rooms for rent” business has any right to be.

The bear case is equally straightforward: hotels are cyclical, and Hilton can’t opt out of the macroeconomy. A recession would pressure occupancy and room rates. The asset-light model softens the blow, but it doesn’t eliminate it. Competitive pressure is also relentless. Alternative lodging—especially Airbnb—has permanently changed what many travelers expect, and it has captured real share in certain leisure segments. And margin pressure could show up if owners push for better economics or if the cost of distribution rises.

A Porter’s Five Forces lens highlights the pressure points. Supplier power, including labor, increased post-pandemic, squeezing hotel-level margins and making the franchisee math harder in some markets. Buyer power has grown as online travel agencies like Booking.com and Expedia concentrate demand and charge commissions. The threat of substitutes is higher than it used to be because non-hotel options have proven mainstream appeal. And competitive rivalry remains intense: Marriott’s scale is a constant challenge, while Hyatt’s luxury weighting pulls demand in the high-end segments in a different way.

The technology disruption risk is worth sitting with. Airbnb began as a leisure substitute, but it has expanded into business travel and experiences. And the broader risk isn’t just “Airbnb wins.” It’s that customer loyalty could shift away from hotel brands altogether and toward aggregators and platforms that sit between the traveler and the hotel, turning accommodations into a more commoditized inventory game.

Key KPIs to track: If you want to monitor whether Hilton’s story is staying on track, three metrics tend to matter most:

-

Net Unit Growth: the pace at which Hilton expands its room count, including how well the pipeline converts into openings and how effectively Hilton retains existing properties. This is the clearest signal of brand momentum with owners.

-

RevPAR Growth: revenue per available room captures both demand and pricing power across the system. Sustained RevPAR growth is a sign the brand is staying competitive and the travel environment is healthy.

-

Hilton Honors Engagement: member growth is important, but so is how many members are actually active, and how much booking shifts toward direct channels through the program. That’s where loyalty turns into a real distribution advantage.

XII. Recent News

Hilton’s fourth quarter and full-year 2024 results, announced in February 2025, were essentially management saying: the machine is still working. They pointed to continued execution against their priorities—especially record development signings, a fast-growing pipeline, and demand strength that wasn’t confined to just one corner of the portfolio. Luxury held up, mid-scale kept humming, and international markets continued to show momentum.

The headline for owners and investors stayed the same: growth you can see coming. As of December 31, 2024, Hilton’s development pipeline stood at 498,600 rooms, with about 34,200 new rooms approved in the fourth quarter alone. Management acknowledged the obvious friction—construction cost inflation and tougher financing in some markets—but emphasized that pipeline conversion, the critical step from “signed” to “open,” remained on track.

On brands, the most notable recent push has been Spark by Hilton. It’s Hilton’s move into the economy tier—territory the company historically didn’t cover in a big way. Management described strong franchisee interest and said early properties were outperforming expectations, a signal that Hilton’s distribution and standards can travel down-market as well as up.

On technology, Hilton kept investing in the parts of the experience that remove friction and keep customers booking inside the ecosystem: improvements to the Hilton Honors app and wider availability of Digital Key. Management also said direct digital bookings continued taking share from online travel agencies—important not just for lower distribution costs, but because it keeps the customer relationship, and the data, inside Hilton’s walls.

And the capital playbook stayed consistent. Hilton continued to prioritize organic investment in technology and brand support, while returning significant capital to shareholders through dividends and repurchases. The $3 billion returned in 2024 was framed as a continuation of a simple message: keep funding the engine, but don’t hoard the cash.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings & Investor Materials - Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. annual reports and 10-K filings (SEC EDGAR) - Quarterly earnings releases and investor presentations - Investor Day presentations

Industry Analysis - CBRE Hotels research reports - STR global hospitality data and analytics - Phocuswright travel industry reports

Historical References - Be My Guest by Conrad Hilton (autobiography) - The Silver Spade: The Conrad Hilton Story (biography) - Harvard Business School case studies on Hilton Hotels and the Blackstone LBO

Private Equity Analysis - Blackstone quarterly letters to investors (2007–2018) - PE Hub and PitchBook analysis of the Hilton transaction - King of Capital: The Remarkable Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of Steve Schwarzman and Blackstone by David Carey and John Morris

Trade Publications - Hotel News Now (hospitality industry news) - Skift (travel industry analysis) - Lodging Magazine (hotel operations coverage)

Academic Research - Cornell School of Hotel Administration research on hotel franchising - NYU Stern case studies on hospitality brand portfolio strategy

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music