IBM: The Story of Big Blue's Century-Long Transformation

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

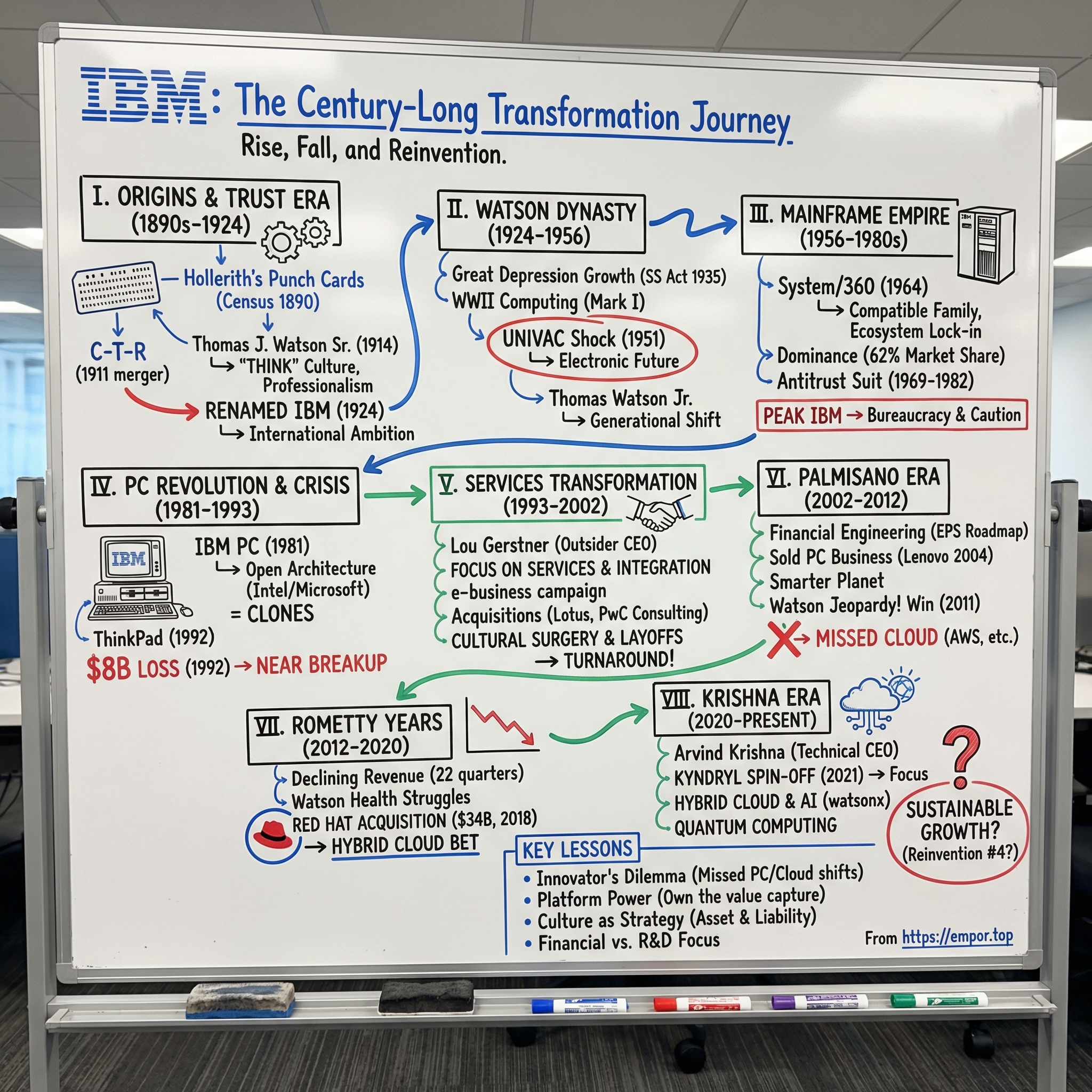

Picture a company that once owned the center of the computing universe. At its peak, IBM controlled roughly 70% of the global mainframe market, employed more than 400,000 people, and loomed so large that the U.S. government spent thirteen years trying to break it up. Its three-letter logo didn’t just represent a vendor. For decades, it practically meant “computing.”

Fast-forward to today: IBM is a $223 billion market cap business doing $62.75 billion in annual revenue, once again pitching a new identity—this time around hybrid cloud and artificial intelligence.

So how did a punch-card tabulator company become the architect of modern computing? And, more importantly, can it pull off one more reinvention?

Because IBM isn’t just a corporate biography. It’s a guided tour through the last century of information technology. From Herman Hollerith’s breakthrough Census Bureau contract in 1890, to Watson beating human champions on Jeopardy! in 2011, to the present-day race in quantum computing, IBM has shown up at nearly every major inflection point.

But showing up isn’t the same as winning. IBM’s story is as much about what it missed—personal computing, cloud infrastructure, mobile—as what it pioneered.

This is a story of rise, fall, and reinvention. Of a family dynasty and an outsider savior. Of world-class engineering—and strategic decisions that aged horribly. And of a company that may have reinvented itself more times than any other icon of American business, now staring down the question of whether it has one more transformation left.

In this episode, we’ll trace the arc from mechanical tabulators to AI and quantum computing—following the decisions, personalities, and market forces that shaped Big Blue. And along the way, we’ll pull out the lessons that matter most for anyone trying to answer the investing question at the heart of IBM today: is this comeback real, or are the glory days permanently in the rearview mirror?

II. Origins: Hollerith's Punch Cards & The Trust Era (1890s–1924)

The story begins not in a garage or a dorm room, but inside the U.S. government—where a young engineer named Herman Hollerith ran headfirst into a problem that was quickly becoming unmanageable. The 1880 U.S. Census had taken eight years to tabulate. America was growing so fast that officials feared the 1890 census might not be finished before the 1900 census even began.

Hollerith’s spark came from an everyday system hiding in plain sight. Watching a train conductor punch tickets in specific patterns to encode passenger information, he saw the outline of a machine-readable language. If holes in paper could represent facts, then a machine could read those facts—count them, sort them, and produce results at speeds humans simply couldn’t match.

His Tabulating Machine Company won the contract for the 1890 Census, and the impact was immediate: what had taken eight years dropped to about one. The punch card—just cardboard with holes in certain positions—became one of the first practical ways to store and process data at scale.

Just as important, Hollerith didn’t sell his machines. He leased them. That choice planted an early version of a business model IBM would perfect for decades: keep control of the platform, charge for ongoing use, and make switching away painful.

But Hollerith was an engineer first. When he lost the 1910 Census contract to a cheaper competitor, the limits of his business instincts showed. In 1911, he sold the company to Charles Ranlett Flint, a Wall Street dealmaker widely known as the “Father of Trusts.” Flint didn’t invent products; he assembled industries. He had already rolled up businesses in everything from rubber to shipbuilding to chewing gum. What he saw here was a fragmented “business machines” world that could be consolidated.

Flint combined four companies: Hollerith’s Tabulating Machine Company; the International Time Recording Company, maker of employee time clocks; the Computing Scale Company, which produced commercial scales; and Bundy Manufacturing. The result was the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company—C-T-R—a name that sounded exactly like what it was: a stitched-together portfolio of time clocks, meat scales, and tabulators with no obvious story holding it together.

The real breakthrough wasn’t the merger. It was who Flint hired next.

In 1914, Thomas J. Watson Sr. arrived to run C-T-R with both enormous talent and a very public stain. At National Cash Register, Watson had been a star salesman and executive—and had helped drive aggressive tactics meant to crush competitors. He was convicted of antitrust violations, though that conviction was later overturned on appeal. When Flint handed him C-T-R, Watson was forty years old, newly humbled, and intensely motivated to rebuild his name.

Watson didn’t begin by reinventing the machines. He reinvented the company around them.

He believed selling business equipment wasn’t about specs; it was about trust, relationships, and conviction. He built a culture that turned sales into a disciplined craft and employees into believers. He put THINK signs on walls as a constant prompt that work should be intellectual, not mechanical. He introduced company songs, loyalty rituals, and strict standards of appearance and behavior—dark suits, white shirts, clean-cut professionalism. IBM’s workforce became a kind of uniformed sales and service army.

That culture became a weapon. It would help IBM rise, contract after contract, into the center of American business. And later, when the world changed faster than IBM could, it would also become a weight.

In 1924, Watson gave the company a new name: International Business Machines.

It was ambitious bordering on audacious. C-T-R was still largely domestic, still selling time clocks and scales alongside its tabulating equipment. But Watson understood something that great company-builders always do: the name isn’t just what you are—it’s what you intend to become. “International Business Machines” sounded like the future, and Watson meant to grow into it.

By the mid-1920s, the pieces were in place: a company with a cohesive identity, a disciplined culture, a leader with a singular drive, and a core technology—punch cards and tabulating machines—that would become a ramp into the information age.

III. The Watson Dynasty: Building the Foundation (1924–1956)

Thomas Watson Sr. didn’t just run IBM. He was IBM. Tall, severe, and intensely charismatic, he blended revival-meeting conviction with command-and-control discipline. Inside the company, his worldview was everywhere—none more so than in the slogan he loved to repeat and display: “World Peace Through World Trade.” Watson meant it. He believed commerce could knit nations together strongly enough to avoid another catastrophic war. But it also doubled as a mission statement for IBM itself: be global, be indispensable, and sit at the center of how modern organizations were managed.

Then came the Great Depression, and with it the kind of decision that separates cautious managers from empire builders. While other business machine companies cut production and shed workers, Watson kept IBM’s factories humming. He built inventory on purpose, betting that the economy would eventually turn—and that when it did, customers would want machines immediately. IBM would be the only one able to deliver.

That gamble found its moment in 1935. The Social Security Act created an administrative problem unlike anything the U.S. government had ever attempted: tracking earnings and benefits for millions of people, year after year. The federal government needed a data-processing engine. IBM had the punch cards, the tabulators, and—thanks to Watson’s Depression-era stockpiling—the capacity. Winning that work didn’t just bring revenue. It cemented IBM as a partner to government at a scale no competitor could match. IBM wasn’t merely selling equipment anymore; it was becoming part of the infrastructure of modern society.

But the same closeness to state power also produced one of the darkest chapters in the company’s history. Through its German subsidiary, Dehomag, IBM’s technology was used by the Nazi regime for censuses and administrative tracking—tools that supported the machinery of persecution and, ultimately, the logistics of the Holocaust. Watson himself accepted a medal from Hitler in 1937 and returned it in 1940 as war approached. How much IBM leadership understood about the end uses, and when, remains debated by historians. What isn’t debated is the uncomfortable lesson: information technology is not morally neutral once it’s embedded in systems of power.

World War II pushed IBM further, faster, toward computing. Militaries needed calculation at scale—ballistics tables, logistics planning, and other problems where speed and accuracy mattered. IBM engineers helped build the Harvard Mark I, an electromechanical computer completed in 1944. Watson Sr. remained skeptical about computers as a commercial market—he’s often credited with predicting demand for “maybe five computers,” a line that may be apocryphal—but whether he said it or not, the sentiment fit. His engineers, however, were quietly learning what the next era would require.

IBM’s wake-up call arrived in 1951, and it came on live television. Remington Rand’s UNIVAC correctly predicted Dwight Eisenhower’s landslide election-night victory, turning electronic computing into a public spectacle. America watched a machine do something that felt impossible—take messy, real-world data and produce a correct outcome in real time. And it wasn’t an IBM machine. For the punch-card giant, it was an alarm: the future had arrived, and IBM was late to the party.

The person who refused to let IBM miss it was Watson’s son. Thomas Watson Jr. grew up under the pressure of his father’s legend, wrestling with depression and self-doubt, never entirely convinced he could measure up. But he saw what his father didn’t want to: electronic computers weren’t scientific curiosities. They were the next platform. Junior pushed IBM to commit, to build its own computer line, and to modernize how the company thought about technology and competition.

That generational shift was anything but smooth. Father and son collided over strategy, culture, and who truly controlled the company. IBM had been built around Watson Sr.’s force of personality; it now had to become an institution that could operate without him at the center. In 1956, Watson Sr. handed the CEO role to Watson Jr.—just six weeks before his death. Along with the title, he passed down a deeper challenge: could IBM’s discipline and loyalty, the very traits that made it great, flex enough to survive an era changing at electronic speed?

IV. The Mainframe Empire: System/360 and Total Dominance (1956–1980s)

In the spring of 1964, Thomas Watson Jr. stepped in front of reporters and industry leaders and made a claim that sounded like pure CEO bravado: this was “the most important product announcement in company history.” He wasn’t selling hype. He was unveiling the IBM System/360—and with it, a new definition of what a computer was.

Up to that point, computers were basically bespoke machines. Each model was its own island. Software written for one IBM system wouldn’t run on the next one, even if it also had an IBM badge. If a customer wanted to upgrade, they weren’t upgrading so much as starting over: new hardware, new software, new training, new processes. The friction wasn’t a bug. It was the industry.

Watson Jr. decided to blow that up with a radical idea: a family of compatible computers, spanning everything from smaller departmental machines to massive enterprise systems, all able to run the same software. Start small, grow over time, and keep your investment. In other words: a platform. The System/360 wasn’t just a product line—it was the template for the ecosystems that would define modern computing.

It was also an all-in bet. Development cost around $5 billion—roughly on the order of IBM’s annual revenue at the time. If it failed, IBM likely failed with it. Thousands of engineers were pulled into a program so sprawling and so interdependent that IBM had to develop new ways of coordinating work at scale—early versions of what we’d now call modern project management—just to keep the whole thing from collapsing under its own weight.

And then the gamble hit.

System/360 didn’t merely sell; it rewired the industry around IBM. By 1981, the company held 62% of the global mainframe market. But the number undersells what IBM had really built. System/360 created lock-in the old-fashioned way: through everything wrapped around the machine—software, training, procedures, and the sheer risk of switching. Corporate IT departments internalized the conclusion as a proverb: “Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.” It wasn’t about loving IBM. It was about choosing the safest possible answer.

This was also peak IBM culture—the era people still picture when they hear “Big Blue.” White shirts and dark suits weren’t a style choice; they were a signal of discipline and reliability. The company ran like an institution. Employees were expected to be professional, controlled, and loyal. In return, IBM offered something that now feels almost mythical: de facto lifetime employment. Layoffs were rare enough to be shocking. IBM poured money into training and groomed leaders by rotating them through divisions, creating general managers who understood the whole machine.

Power like that tends to invite a response. In 1969, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust suit accusing IBM of monopolizing the computer industry. The case would hang over the company for thirteen years before it was dismissed in 1982. Even without a verdict, the threat mattered. IBM learned to move carefully, to document everything, to build layers of process and review—a kind of institutional self-protection. Some historians argue that the long antitrust shadow made IBM more cautious and bureaucratic right as the wider industry was about to enter a period of explosive experimentation.

Competitors, meanwhile, started to attack where they could. Gene Amdahl, one of IBM’s star engineers and a key figure behind System/360, left to build “plug compatible” mainframes—machines designed to run IBM software for less money. Storage Technology pulled a similar move in disk drives. These challengers exposed an uncomfortable truth: part of what customers paid for with IBM was the comfort of the IBM name. And under the right circumstances, they were willing to trade some of that comfort for savings.

Still, for a long stretch, IBM looked untouchable—the most valuable and admired technology company in the world. But the very things that made this era so dominant also set the trap. IBM became huge, process-heavy, and intensely focused on defending its mainframe franchise. And that made it dangerously hard to see the next revolution coming from below.

The twist? That revolution would be sparked, improbably, by IBM itself.

V. The PC Revolution: Triumph and Tragedy (1981–1993)

In August 1981, IBM did something almost unthinkable for a company built on control: it shipped a product it didn’t fully own. The IBM Personal Computer, unveiled at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, would reshape the tech industry—just not in the way IBM intended.

The PC wasn’t born from confidence. It was born from fear.

Inside IBM, planners were watching Apple, Commodore, and a growing swarm of upstarts sell personal computers by the millions. Mainframes were still throwing off cash, but the center of gravity was shifting toward smaller machines, spread across departments and desks. IBM needed an answer—and it needed one fast. The problem was that “fast” and “IBM” didn’t belong in the same sentence. A normal IBM product cycle could stretch to four years. The personal computer market was changing in months.

So IBM did an end run around itself.

It set up a skunkworks in Boca Raton, Florida—far from headquarters and far from the immune system of committees and approvals. A small team of a dozen engineers, led by Don Estridge, got a mandate that came with unheard-of freedom: build a personal computer in a year, and do whatever it takes to get it out the door.

They broke rules that had defined IBM for decades. Instead of building proprietary hardware, they assembled the machine from off-the-shelf components. Instead of writing their own operating system, they licensed one from a tiny company in Seattle called Microsoft. And instead of selling through IBM’s traditional channels, they put the PC into retail stores.

It worked—spectacularly. The IBM PC took off, selling about 750,000 units in its first year, blowing past expectations. But the bigger win wasn’t the unit count. It was what the three letters on the front meant to corporate America. Businesses that had treated personal computers like toys suddenly had a safe choice. If it was IBM, it must be real. “IBM compatible” quickly became the new shorthand for the standard.

And that’s where the tragedy starts, because the same shortcuts that made the IBM PC possible also made it copyable.

Since the machine relied on standard parts and a licensed operating system, rivals could build something functionally identical. In 1982, Compaq reverse-engineered the BIOS—the layer that helped the hardware talk to the operating system—and shipped the first major “clone.” Then came dozens more. They all ran the same software, and many were cheaper.

IBM had ignited a platform it didn’t control.

Microsoft kept the right to license DOS to other manufacturers, turning IBM’s breakthrough product into the launchpad for Microsoft’s software dominance. Intel, selling processors to anyone with a purchase order, became the other pole of power. In the PC world, the value pooled around the operating system and the chip—not the logo on the beige box. IBM had legitimized the market, but Microsoft and Intel captured the economics.

IBM still had flashes of brilliance. The ThinkPad, introduced in 1992, proved the company could build an iconic personal computer product: the sleek black design, the red TrackPoint, and the sturdy, business-first feel made it a status symbol in corporate IT. But even ThinkPad exposed the underlying problem. It was a premium machine in a market racing toward commodity pricing. IBM could win on engineering. It couldn’t win on the brutal math of scale and cost.

By the early 1990s, the bill came due. Mainframes were under pressure as customers shifted toward smaller, networked systems. PCs were a knife fight IBM was losing to leaner competitors. Revenue slid from $65 billion in 1990 to $63 billion in 1992, and the company posted an $8 billion loss—then the largest in American corporate history.

For IBM, the crisis wasn’t just financial. It was existential. And it forced a decision that would have been unthinkable in the Watson-era playbook: the board went outside the company for a CEO.

For decades, IBM had been a closed loop, promoting insiders who spoke the language and lived the culture. Now the board decided the culture itself was part of the problem. They needed someone who could look at IBM without the inherited assumptions—and make changes that an insider might never survive.

They chose Lou Gerstner, then CEO of RJR Nabisco and previously a senior partner at McKinsey. He wasn’t a technologist. He hadn’t run a tech company. But he saw what many inside IBM had stopped seeing: IBM’s most valuable asset wasn’t any single machine. It was the trust—and the deep relationships—with the world’s largest organizations. If IBM had a future, it would be built on that foundation.

VI. The Services Transformation: Gerstner's Revolution (1993–2002)

Lou Gerstner walked into IBM in April 1993 and found a company that didn’t just look sick—it looked breakable. The board was openly weighing a breakup: split IBM into a PC company, a mainframe company, a software company, and hope the pieces were worth more than the whole. Wall Street was already drafting the epitaph. Inside the company, the mood was worse. People who’d spent their careers inside an institution built on certainty were suddenly staring at the possibility that IBM might not make it.

At his first press conference, Gerstner delivered what sounded like heresy for a company that had always run on grand pronouncements: “The last thing IBM needs right now is a vision.” It wasn’t evasive. It was the point. IBM didn’t need another moonshot or a sweeping technical manifesto. It needed to stop bleeding, get brutally honest about what it still did better than anyone, and execute.

So he did the simplest thing—and in IBM’s case, the most revealing: he went to customers. He listened. And what he heard didn’t match the breakup logic. Customers weren’t begging for a smaller IBM. They were begging for a more useful one. Their environments were turning into a messy mix of mainframes, PCs, networks, and software from a dozen vendors. What they wanted wasn’t another box. They wanted someone to make the whole thing work.

That became the core of the turnaround: IBM would sell integration. Not just products, but the ability to design, build, and run an entire IT environment. A shift from shipping machines to delivering systems. From transactions to long-lived relationships. From “Here’s our hardware” to “Here’s the outcome you need, and we’ll get you there.”

But becoming a services-led company meant building muscles IBM didn’t yet have. In 2002, IBM made that commitment unmistakable by acquiring PricewaterhouseCoopers Consulting for $3.5 billion. Overnight, IBM added roughly 30,000 consultants and a much bigger footprint in advising executives on technology strategy. It was controversial—an engineering-driven company absorbing an army of consultants—but that was exactly why it mattered. IBM wasn’t dabbling in services. It was betting the company on it.

The late 1990s internet boom then handed IBM the perfect narrative moment. While dot-coms chased consumers, IBM positioned itself as the grown-up at the table: the company that could help established enterprises become digital without breaking what already worked. Its “e-business” campaign—one of the era’s defining marketing successes—made IBM synonymous with the enterprise internet. IBM wasn’t trying to sell pet food online. It was helping the Fortune 500 rewire how they operated.

Gerstner also understood a hard truth about services: the margins look a lot better when you’re implementing your own software. So he pushed software aggressively, including acquisitions that expanded IBM’s reach. The 1995 purchase of Lotus Development for $3.5 billion brought Notes, a leading collaboration platform. IBM also built up DB2, developed WebSphere into a major application server platform, and added key capabilities through deals for Tivoli in systems management and Rational in software development tools. The pattern was consistent: more software meant more pull-through for services—and a stronger claim to being the vendor that could provide an integrated solution.

And then there was the cultural surgery. IBM had become a federation of fiefdoms—divisions optimized for their own scorecards, not the company’s survival. Gerstner went after that. He broke down internal walls, pushed accountability, and did what had once been unthinkable inside the IBM covenant: he normalized layoffs, executing painful workforce reductions to reset the cost structure. He brought in outside talent, elevated leaders willing to challenge legacy assumptions, and forced IBM to look outward again. The uniforms and formality didn’t vanish overnight, but the self-contained certainty that had helped IBM miss the PC shift started to give way to something more competitive and customer-driven.

By the time Gerstner retired in 2002, IBM had pulled off a genuine reinvention. Services and software—once supporting characters—were now driving most of the profits. IBM had survived, and in doing so, had changed what it was.

But that change carried a trade-off. The company that once defined the frontier of computing was increasingly becoming the company that helped everyone else use it. IBM was back on its feet. The question was what kind of giant it would be in the next era—and whether the strategy that saved it would also, quietly, limit it.

VII. The Palmisano Era: Financial Engineering & Early Cloud (2002–2012)

Sam Palmisano was pure IBM. He joined in 1973 as a salesman, climbed through the ranks, and ultimately ran the server business that helped power the Gerstner-era turnaround. So when he became CEO in 2002, he didn’t inherit a sinking ship. He inherited something arguably harder: a stabilized IBM that didn’t have an obvious next act. Healthy, respected, and cash-generative—but not exactly a growth story.

Palmisano’s answer was a promise Wall Street could measure.

In 2007, he unveiled “Roadmap 2015,” a commitment to hit $20 in earnings per share by 2015—about double the level at the time. It was bold, simple, and easy to model. The stock popped. Investors love a clear target.

The catch was hidden in what the roadmap didn’t say. It was an earnings plan, not a revenue plan. And if your top line isn’t expanding, there are only a few levers left to pull. IBM pulled all of them: relentless cost cutting, repeated rounds of layoffs that became grimly routine, a steady shedding of lower-margin businesses, and aggressive share repurchases. Over the long arc from 2000 to 2020, IBM spent more than $200 billion buying back its own stock, shrinking the share count by about half.

The divestitures extended the logic Gerstner had started: exit the commoditized stuff, double down on higher-value work. In 2002, IBM sold its hard disk drive business to Hitachi. In 2004, it did something that felt almost symbolic: it sold the PC business to Lenovo for $1.75 billion. The company that had legitimized the personal computer was conceding that it could no longer compete in the market it helped create—and the ThinkPad, IBM’s crown jewel in PCs, went with it. IBM executives weren’t wrong about the economics; PCs had become a brutal, thin-margin commodity. But the steady shedding of product categories also sent a message about ambition. IBM was becoming better at managing maturity than inventing the next platform.

Palmisano tried to give IBM a future-facing narrative with “Smarter Planet,” a push to apply analytics and optimization to big, real-world systems—traffic, energy, healthcare, education. It was a compelling idea, and IBM did invest heavily in analytics. But Smarter Planet often functioned more like a positioning campaign than a sharp product strategy, especially in a decade when Google, Apple, and Amazon were capturing the public imagination and defining what “technology company” meant.

The era’s most visible burst of innovation came from IBM Research. In 2011, Watson beat human champions on Jeopardy!, a made-for-TV demonstration that machines could parse natural language, search huge bodies of information, and respond in something close to real time. It was a cultural moment and a marketing triumph, and IBM poured effort into turning Watson into a commercial product line. But translating a tightly scoped game-show system into repeatable, practical solutions for messy enterprise environments proved far harder than the demo made it look.

And then there was the miss that mattered most—one that didn’t fully register in real time. IBM missed the cloud revolution.

While Amazon was quietly turning its internal infrastructure into AWS, IBM stayed oriented around selling and servicing enterprise data centers, along with the hardware that filled them. Technically, IBM had plenty of the ingredients: deep experience with large-scale computing, enterprise reliability, virtualization, and the operational know-how to run complex systems. Strategically, though, cloud was a direct threat to the model IBM still depended on. Cloud shifted spending away from owned hardware and toward on-demand infrastructure. It didn’t just create a new market—it cannibalized the old one. Like so many incumbents, IBM struggled to fully embrace a future that would eat its present.

So by the time Palmisano retired in 2012, the scoreboard looked good—financial targets were being hit. But the foundation was thinning. R&D spending as a share of revenue had declined. Top engineering talent was drifting to Google, Amazon, and fast-growing startups. IBM was getting better at winning the quarterly game, even as it fell behind in the race for technological relevance.

VIII. The Rometty Years: Struggling for Relevance (2012–2020)

When Ginni Rometty became IBM’s first female CEO in January 2012, she inherited something deceptively dangerous: a company that still looked like it had a plan. “Roadmap 2015” was in full effect, with its crisp earnings-per-share target and its implicit marching orders—keep cutting costs, keep buying back stock, keep squeezing the machine.

Rometty leaned into that discipline at first. In a company as sprawling as IBM, a hard target can feel like clarity. But the business underneath the spreadsheet kept deteriorating. Revenue fell quarter after quarter, until the streak reached 22 consecutive quarters of decline. At that point, the roadmap wasn’t a plan so much as a constraint—one that pushed IBM to optimize the old model while the market moved on.

The problem was structural. IBM’s legacy pillars—mainframes, middleware, and consulting—were mature at best and shrinking at worst. The would-be growth engines—cloud, analytics, security, mobile—weren’t scaling fast enough to cover the slide. By then, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google had opened up massive leads in cloud infrastructure. Enterprise software was shifting toward SaaS models that IBM had been slow to embrace. And services faced pressure from both low-cost offshore providers and sharper, specialized firms.

Watson became the symbol of the era: breathtaking promise, messy reality. After the Jeopardy! win, IBM pushed Watson into nearly every boardroom conversation—Watson for healthcare, Watson for finance, Watson for legal research. The underlying technology was real, and it arrived early in what would become the modern AI wave. But turning a headline-grabbing demo into dependable, repeatable enterprise products proved far harder than the marketing suggested. Watson Health, the biggest swing, absorbed billions in acquisitions and development, yet never delivered the widely promised breakthrough in cancer treatment and clinical decision-making.

To speed up the transformation, Rometty went shopping. In 2015, IBM bought The Weather Company’s data assets to strengthen its data and IoT ambitions. In 2016, it acquired Truven Health Analytics for $2.6 billion, intended as a core data foundation for Watson Health. But the deals struggled to integrate—and the expected synergies were elusive.

Then came the move that defined her legacy. In 2018, Rometty announced IBM would acquire Red Hat for $34 billion, the largest software acquisition in history at the time. Red Hat wasn’t just the leading enterprise Linux company; it was one of the most trusted names in open source. And crucially, it had built real traction in hybrid cloud—helping enterprises run applications across their own data centers and across multiple public clouds. IBM didn’t just buy revenue. It bought credibility in the market that mattered most.

But the deal also underlined how far IBM had fallen behind. The company was paying a huge premium—over $190 per share when Red Hat had been trading around $116—for capabilities IBM arguably should have built years earlier. And the integration challenge was obvious from day one: Red Hat’s open-source, developer-first culture was the mirror image of IBM’s traditional enterprise sales machine. Keeping Red Hat’s momentum—and spirit—would require restraint and patience IBM hadn’t always shown with past acquisitions.

Rometty retired in April 2020 with the Red Hat integration still underway and a pandemic about to scramble enterprise priorities. Her tenure was defined by declining revenue, a falling stock price, and a lingering question IBM couldn’t quite outrun: was this still a company that could reinvent itself, or just one that could manage decline?

Still, she left IBM with something it badly needed—a new cornerstone. The hybrid cloud and AI bet was now in motion. The next CEO’s job would be simple to describe and brutally hard to execute: turn that bet into a real comeback.

IX. The Krishna Era: Hybrid Cloud & AI Renaissance (2020–Present)

Arvind Krishna became IBM’s CEO in April 2020, with the world sliding into lockdown and the global economy wobbling. Unlike many of his predecessors, Krishna was both an IBM lifer and deeply technical. He’d run the company’s cloud and cognitive software business, and he’d been one of the key internal champions of the Red Hat deal. His mandate was straightforward to describe and painfully hard to deliver: simplify IBM, focus it, and make it move like a company that still had urgency. The strategy was equally clear: hybrid cloud and AI, with a portfolio that finally fit the story.

The first big move was also the most symbolic. In November 2020, Krishna announced IBM would spin off its managed infrastructure services business into a new public company: Kyndryl. This was the part of IBM that ran and managed other companies’ data centers and infrastructure—roughly $19 billion in annual revenue, dependable in the way legacy businesses often are, but also a drag on growth and margins. Classic old IBM: big, complex, and slowly declining. The logic of the spin was ruthless. IBM couldn’t keep telling the market it was a modern software-and-cloud company while carrying a massive infrastructure outsourcing unit that pulled the narrative—and the financials—backward.

Kyndryl officially separated in November 2021, in what IBM described as the largest corporate spinoff in technology history. Critics saw it as IBM shrinking itself into better-looking metrics instead of truly growing. But strategically, it gave IBM something it hadn’t had in years: a cleaner identity. Post-Kyndryl, the company could center itself around three pillars—Red Hat and hybrid cloud, data and AI, and consulting—while pushing the infrastructure-heavy work offstage.

With the portfolio slimmer, Krishna leaned hard into buying capabilities rather than waiting to build them. IBM picked up Turbonomic for about $1.5 billion in 2021 to bring AI-driven application resource management. It acquired Instana for application performance monitoring. In 2023, it bought Apptio for technology business management software. And the dealmaking continued with acquisitions such as Seek, DataStax, and Hakkoda. The pattern was consistent: find the gaps in IBM’s hybrid cloud and AI stack, and fill them through M&A when internal development would take too long. In total, IBM has completed about 195 acquisitions—less a shopping spree than an operating model.

Then generative AI detonated into the mainstream in 2023 and 2024. For IBM, it was both a second chance and a new kind of pressure test. The company had spent years talking about AI, and Watson had made IBM look early—almost prophetic. But the commercial payoff never matched the promise. Now the market had changed overnight: competitors were racing to ship generative AI features, and IBM’s customers were suddenly demanding real deployments, not demos.

IBM’s answer was watsonx, a platform designed to build and deploy AI models inside enterprises. IBM didn’t position it like a consumer chatbot. Instead, it leaned into the things large organizations obsess over—governance, security, and integration with existing systems. In other words, IBM played to its home field. The company said its generative AI book of business exceeded $3 billion, a sign that customers were engaging in a way Watson, historically, struggled to sustain.

Through it all, Red Hat remained the brightest spot. OpenShift and the broader Red Hat portfolio kept delivering consistent double-digit growth, powered by enterprises that wanted modern application platforms without committing their entire future to one cloud provider. That’s the enduring appeal of “hybrid cloud”: run workloads across your own data centers and multiple public clouds, and keep leverage. For customers wary of being boxed in by AWS or Azure, Red Hat’s positioning made intuitive sense—and gave IBM a credible engine at the center of its strategy.

Krishna has also kept IBM pushing in quantum computing, where the company operates the largest fleet of quantum systems available for commercial and research use. IBM has continued to hit milestones on its quantum roadmap, increasing qubit counts and improving error rates. Whether quantum becomes broadly commercial anytime soon is still an open question. But IBM is positioned to benefit if and when “quantum advantage” moves from lab milestone to practical reality.

The early result of all this has been something IBM hadn’t seen in a long time: stability. Under Krishna, IBM delivered the first sustained stretch of steadier revenue after years of erosion. The company also continued investing heavily in R&D, spending more than $5 billion annually—though, as a share of revenue, still less than what hyperscaler competitors put to work.

Now comes the real test. Is IBM’s simplification and focus the start of a durable return to growth and relevance? Or is it simply a more elegant version of the old playbook—shedding weight, polishing the metrics, and hoping the market rewards the story?

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

IBM’s century-long journey isn’t just corporate history. It’s a repeatable set of patterns—how great companies build moats, how they get trapped by them, and how hard it is to reinvent when your past success becomes your operating system.

The Innovator's Dilemma, Personified

If you wanted to illustrate Clayton Christensen’s thesis with a single company, IBM would do the job. Mainframes threw off enormous profits, so minicomputers looked like a low-end distraction. The IBM PC took off, but clones forced a choice between defending margins and defending the standard—and IBM couldn’t bring itself to win a race to the bottom. Then cloud showed up and did what every true disruption does: it didn’t just create a new market, it threatened the economics of the old one.

The point isn’t that IBM’s leaders were blind. In many cases, they could see the shift coming. The problem was that the business model, the customer base, and the org chart all leaned in the wrong direction. When you’re optimized to protect the current engine, you struggle to fund the next one—especially when the next one cannibalizes the first.

Platform Power: When to Own the Ecosystem

IBM’s masterpiece was System/360: a platform so sticky that customers could upgrade without starting over, and so integrated that leaving felt reckless. IBM’s heartbreak was the PC: a platform it helped define, but didn’t control—where the profits flowed to Microsoft and Intel.

The lesson isn’t “always build a platform.” It’s that platform architecture decides who captures the value. IBM chose speed in 1981—off-the-shelf components, licensed software, an open-ish design—and that was exactly what the moment demanded. But that same choice meant that as the market scaled, IBM’s role became optional.

The Services Pivot: Trading Margins for Stability

Gerstner’s shift into services saved IBM. It also changed what IBM was. Services can be steadier than product cycles, especially when customers want one accountable partner to make complex systems work. But services also tend to scale with people, not code. That usually means lower margins and slower growth than great product businesses.

So the pivot was both an advance and a retreat: it kept IBM alive and relevant in the enterprise, while quietly pulling the company away from being the place that defines the next computing platform.

Corporate Culture: Asset and Liability

Watson Sr. built a culture of discipline, loyalty, and professionalism that became a competitive advantage—IBM felt safe, reliable, inevitable. But the same culture could be insular and hierarchical, and those traits don’t age well in periods of rapid technological change.

IBM’s history makes the uncomfortable point that culture isn’t decor. It’s a strategy amplifier. It can help you dominate one era—and make it brutally hard to adapt to the next.

Acquisition Strategy: Building vs. Buying Innovation

Over time, IBM increasingly used acquisitions to buy capabilities it struggled to build internally. Some deals—like Lotus and Red Hat—were genuinely consequential. Many others faded into the product catalog without changing the company’s trajectory.

The pattern suggests IBM became strong at spotting innovation and integrating it into an enterprise sales motion. But it also created a dependency: if the future arrives faster than you can acquire it, you’re stuck.

Financial Engineering vs. R&D Investment

The Palmisano and Rometty years exposed the limits of optimizing the spreadsheet. Buybacks and cost cuts can lift earnings per share, but they can’t will new platforms into existence. IBM still spent heavily on R&D in absolute dollars, yet over time that investment became smaller as a share of revenue—especially compared with the hyperscalers reshaping the industry.

That’s the trade-off mature companies face: returning cash to shareholders is rational. But it’s not the same thing as building the next engine of growth.

XI. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case for IBM

The optimistic case for IBM starts with a simple idea: the company has finally aligned its story with a real product engine. Red Hat has genuine momentum, and it sits in a strategically useful place—hybrid cloud. Most large enterprises don’t want to bet their entire future on a single public cloud. They want the freedom to run workloads in their own data centers, in multiple clouds, and at the edge, and to move between them when economics, regulation, or strategy changes. Red Hat’s OpenShift is built for that reality, and its consistent double-digit growth suggests the demand is real, not just marketing.

The second pillar is IBM’s relationships. For decades, IBM has been embedded inside the world’s biggest organizations. It knows how these customers buy, how they think about risk, and what it takes to pass compliance and security gates. Those relationships are hard to replace. Even when a competitor has a better point product, displacing IBM inside a mission-critical environment often means taking on operational risk most CIOs would rather avoid.

Third, the economics of the business are improving—at least in the segments IBM wants to emphasize. IBM’s software segment generates gross margins above 80%, which puts it in the company of elite software businesses. If IBM can keep shifting its mix toward software and away from lower-margin work, the overall model gets stronger: more recurring revenue, better profitability, and less dependence on labor-heavy consulting.

Fourth, IBM still has credible chips on the table in emerging technologies. Quantum computing may be years away from broad commercial impact, but IBM’s long-term investment has produced genuine technical leadership. And in AI, IBM is leaning into what enterprises actually care about: governance, security, and integration with existing systems. That angle could age well as regulation tightens and companies move from experimentation to real deployment.

Finally, IBM still funds that future. The company has continued to invest more than $5 billion annually in R&D—enough to keep producing real technology, even if it’s not spending at hyperscaler scale.

The Bear Case for IBM

The bearish view is that IBM’s reinvention is still fighting gravity. Consulting, one of IBM’s largest businesses, is vulnerable when customers tighten budgets and delay discretionary projects. Infrastructure is also in long-term decline; revenue in that segment fell 7% in recent quarters as the mainframe installed base continues its slow, structural erosion. The concern is that the growth engines simply aren’t growing fast enough to offset what’s shrinking.

Then there’s the competitive landscape, which is unforgiving. IBM is trying to win in cloud and AI while competing against AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud—companies with enormous scale, vast ecosystems, and R&D budgets IBM can’t match. Hybrid cloud is a compelling positioning wedge, but the bear case says it may not be enough if enterprises ultimately standardize on one or two hyperscaler platforms anyway.

The final worry is execution, and it’s partly cultural. IBM still struggles to attract top engineering talent, especially compared with Google, Amazon, or well-funded startups. Krishna has improved focus and urgency, but decades of bureaucracy and defensive behavior don’t disappear quickly. Even with the right strategy, IBM has to prove it can consistently ship, sell, and deliver at the pace the market now demands.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

This is a brutally competitive arena. Rivalry is intense and getting tougher: IBM faces hyperscalers in cloud, Accenture and Deloitte in consulting, and a long list of pure-play software vendors across its product lines. Barriers to entry are low in many categories of enterprise software, even if they’re high in cloud infrastructure. Buyer power is strong—large enterprises have sophisticated procurement teams and plenty of alternatives. Supplier power is moderate. And substitutes exist for nearly everything IBM offers, which means IBM has to win not just on capability, but on trust, integration, and total cost of ownership.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

IBM’s defensible advantages are narrower than they once were, but they aren’t zero. Network effects are weak; IBM’s products generally don’t become more valuable simply because more customers use them. Scale economies exist in R&D and go-to-market, but the hyperscalers operate at a much larger scale.

The strongest “power” IBM still has is switching costs. Customers with deep IBM deployments—especially in mission-critical environments—face real friction, risk, and expense in moving away. Counter-positioning is possible through hybrid cloud: IBM can credibly serve customers who don’t want to be dependent on hyperscalers, but only if those customers consistently value independence over the simplicity and native tooling of a single-cloud standard.

IBM also has cornered resources—its research organization and patent portfolio—but those strengths haven’t reliably translated into durable market power. Process power and branding still exist, but they’re fading relative to a world where developers, not procurement departments, increasingly shape technology decisions. IBM’s reputation for reliability remains an asset; its brand, especially with younger technical talent, carries less pull than it once did.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

If you want to cut through IBM’s complexity, two metrics do most of the work:

-

Red Hat and hybrid cloud growth rate: This is the engine of the strategy. Sustained double-digit growth supports the transformation thesis. A meaningful slowdown would raise the question of what, exactly, replaces it.

-

Software segment gross margin and revenue mix: Watch whether software keeps delivering 80%+ gross margins and becomes a larger share of the business. If the mix shifts the right way, IBM’s financial profile improves. If it doesn’t, the transformation may be more narrative than reality.

These KPIs won’t answer every question, but they’re the cleanest signal of whether IBM’s comeback is compounding—or stalling.

XII. Epilogue & "If We Were CEOs"

IBM is staring at the kind of question only a handful of companies ever have to answer: can you reinvent yourself a fourth time?

It has already survived three transitions that killed or humbled almost everyone around it—mechanical tabulators to electronic computers, mainframes to distributed systems, and a product business to a services-led enterprise. None of those shifts were clean. Each one was painful. And each time, IBM came out the other side a little less dominant than before. But it did come out the other side. And that alone puts it in rare company.

So if we were sitting in the CEO chair today, what are the real options?

One path is to double down on the big frontier bets: AI and quantum. That means sustained, heavy investment—and the patience to wait for markets that may take years to fully mature. The payoff could be enormous. The risk is just as obvious: you can spend a lot of money being early and still end up being irrelevant when the ecosystem consolidates around someone else’s platform.

Another path is to become the enterprise Switzerland: the neutral, trusted layer that helps large organizations run across on-prem and multiple clouds without getting trapped by any single hyperscaler. That story is credible precisely because Red Hat is credible. But it only works if Red Hat keeps its momentum—and if IBM can stay competitive while AWS, Microsoft, and Google keep pouring resources into the same customers and workloads.

A third option is to keep buying the future. IBM can pursue major acquisitions, and it has done so repeatedly. But acquisitions don’t just cost money—they cost attention. And IBM’s history here is uneven: some deals became real pillars, while others dissolved into the catalog without changing the trajectory. “Buy” can be a strategy, but it’s not a substitute for consistent execution.

And then there’s the hardest problem, the one that doesn’t show up cleanly in quarterly reporting: culture.

The traits that made IBM a safe, durable partner—bureaucracy, conservatism, hierarchy—are exactly the traits that can make it feel like the wrong place for ambitious builders. The best engineers want to ship, iterate, and win markets, not just manage complexity and protect legacy revenue. IBM understood this tension clearly in the Red Hat deal: it kept Red Hat’s culture separate because it knew that absorbing it into traditional IBM process could kill what it bought.

Which leads to the bigger identity question. What is IBM now?

It’s not the mainframe-era empire. It’s not the company that set the PC standard. It’s a roughly $60 billion enterprise technology business with deep customer relationships, serious technical capability, and a permanent burden of proof when it comes to growth. For investors, the upside case is straightforward: the Red Hat thesis keeps working, and AI efforts turn into durable, repeatable revenue. The downside is equally clear: legacy declines accelerate, or the hyperscalers turn “hybrid cloud” into just another feature of their platforms.

In the end, IBM’s arc is the arc of technology capitalism itself: innovation and obsolescence, dominance and disruption, reinvention and decline. No company—no matter how storied—gets permanence. The only question is whether IBM has one more chapter left to write, or whether its best days are finally, definitively, behind it.

A century of history says betting against IBM is dangerous. But that same history also says every reinvention leaves less of the original company behind.

XIII. Recent News

In IBM’s most recent quarterly results, the story looked a lot like the strategy: software led the way, with Red Hat once again doing much of the heavy lifting. Consulting, meanwhile, ran into a softer demand environment as enterprises pulled back on discretionary spending and slowed the pace of new projects.

IBM also kept doing what it’s increasingly done to move faster than its internal product cycles allow: buying missing pieces. The latest deals added capabilities in AI-powered talent intelligence and real-time data processing—tightening the stack around hybrid cloud and AI, and giving IBM more to sell alongside Red Hat and watsonx.

On the AI front, the company said its generative AI book of business has now surpassed $3 billion, a sign that enterprises are moving beyond curiosity and into real budgets and deployments around watsonx. Quantum progress continued as well, with IBM hitting additional milestones on its roadmap—even if truly broad commercial use still looks early and experimental.

And with Kyndryl now fully separated and absorbed into the market’s mental model, IBM’s remaining business is easier to judge on its own merits: a slimmer company, more software-weighted, and more directly accountable to whether hybrid cloud and AI can deliver durable growth.

XIV. Links & Resources

Company Filings - IBM annual report and 10-K filings (via SEC EDGAR) - IBM Investor Relations quarterly earnings materials and presentations - Red Hat financial disclosures from before the acquisition, plus IBM’s post-deal integration updates

Essential Reading - "Who Says Elephants Can't Dance?" by Louis V. Gerstner Jr. — the definitive, inside account of IBM’s 1990s turnaround from the CEO who led it - "Father, Son & Co." by Thomas J. Watson Jr. — a firsthand memoir of the Watson dynasty and IBM’s rise to dominance - "The Maverick and His Machine" by Kevin Maney — a biography of Thomas J. Watson Sr. and the culture he built - "IBM and the Holocaust" by Edwin Black — the most cited, and most debated, examination of IBM’s German subsidiary in the Nazi era - "Computer: A History of the Information Machine" by Martin Campbell-Kelly and William Aspray — a broader history of computing that puts IBM in context

Industry Analysis - Gartner and IDC research on hybrid cloud and enterprise infrastructure trends - IBM presentations from investor conferences (archived on IBM’s Investor Relations site) - Red Hat Analyst Day materials and strategy decks

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music