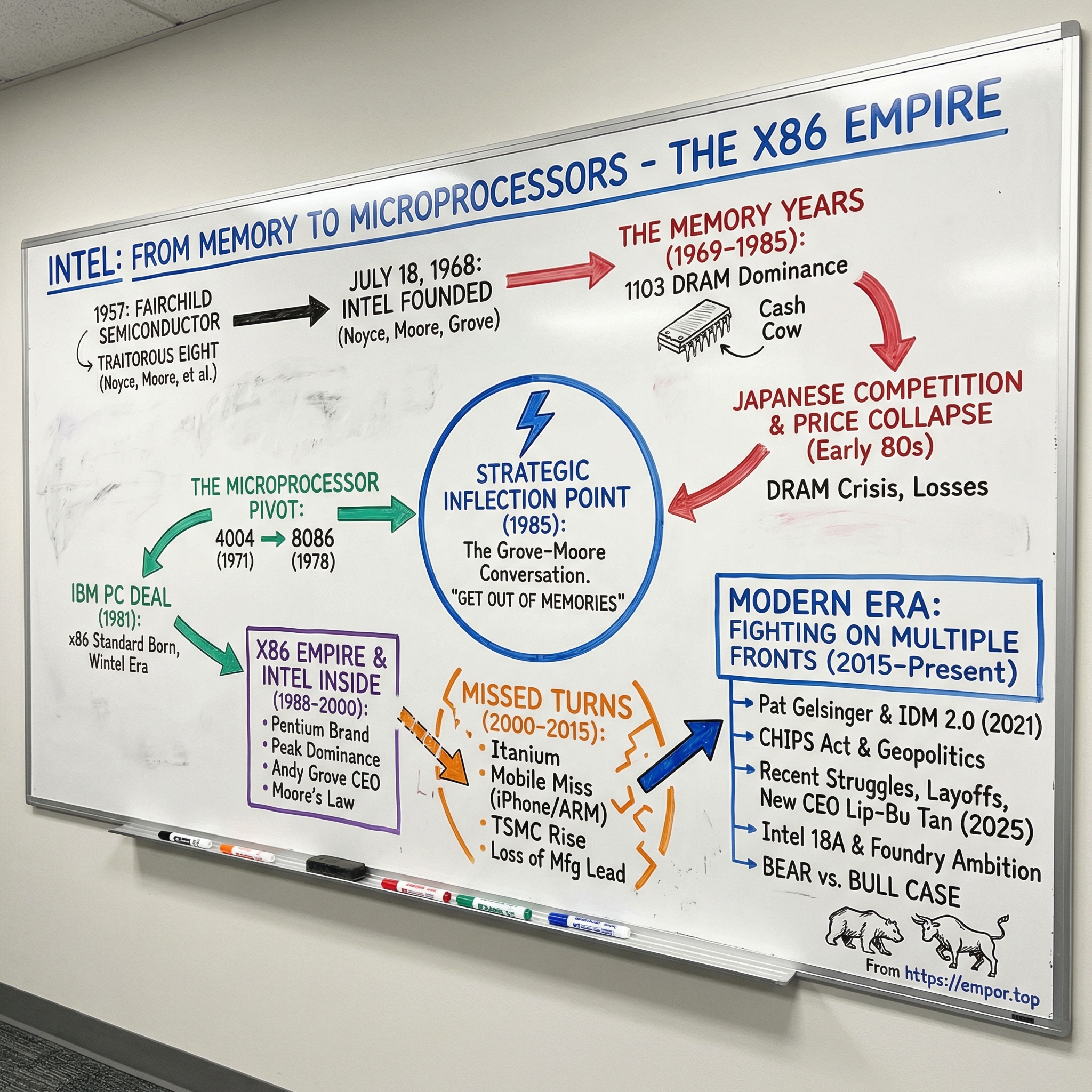

Intel: From Memory to Microprocessors - The x86 Empire

I. Introduction & Cold Open

Picture a cramped office in Santa Clara, sometime in 1985. Andy Grove, Intel’s president, sits across from Gordon Moore, the company’s CEO. Outside that door, Intel’s world is getting uglier by the month. Japanese memory-chip makers are flooding the market. Prices are collapsing. Intel’s core business—the thing it was built to do—is being squeezed toward commodity oblivion. The board is anxious. The numbers are sliding the wrong way.

Grove leans in and asks the kind of question that sounds hypothetical—until you realize it isn’t.

“If we got kicked out,” he says, “and the board brought in a new CEO, what do you think he would do?”

Moore doesn’t even pause. “He would get us out of memories.”

There’s a beat. Grove locks eyes with him and says, essentially: then why are we waiting? “Why shouldn’t you and I walk out the door, come back in, and do it ourselves?”

That exchange became one of the most consequential moments in modern business. Intel was about to abandon the product that had defined it, the product that paid for its factories, its engineers, its reputation—memory—and go all-in on something that, for years, looked like a side hustle: microprocessors.

But to understand how three men ended up making that call—and why it worked—you have to rewind seventeen years, to when two Silicon Valley legends decided to leave the company they’d helped make famous.

Robert Noyce had co-invented the integrated circuit, one of the foundational inventions of the twentieth century. Gordon Moore had articulated what came to be known as Moore’s Law: that the number of transistors on a chip would double roughly every two years, setting the tempo for technological progress for decades. They walked away from Fairchild Semiconductor because they believed they could build something better—faster, bolder, and less constrained by a corporate parent that didn’t want to keep reinvesting in the future.

On July 18, 1968, they founded a company that would go on to define the architecture of personal computing, power the machines that brought the internet to the world, and, for a long stretch, sit at the very center of the technology industry.

It would also make painful mistakes: missing the mobile revolution, losing manufacturing leadership to a Taiwanese rival, and watching as NVIDIA—a company once known for graphics cards—became the defining force of the biggest computing shift since the PC itself: artificial intelligence.

This is the story of Intel. It’s a story about strategic inflection points—the rare moments when the old playbook stops working. It’s about the courage it takes to walk away from your identity. It’s about what happens when a company wins so completely it starts to believe it can’t lose.

And it’s about the question hovering over Intel today: can a fifty-seven-year-old chipmaker reinvent itself for the age of AI?

The stakes go far beyond shareholders. Semiconductor manufacturing now sits at the heart of geopolitics—supply chains, national security, industrial policy, all of it. Intel, with a market capitalization of roughly $241 billion in early 2026, is still one of the biggest chip companies on Earth. But the arc matters. In 1999, Intel’s market cap topped $274 billion. Adjusted for inflation, Intel is worth far less today than it was a quarter century ago. Meanwhile, NVIDIA has surged past $3 trillion, and TSMC—the foundry that now builds the world’s most advanced chips—has climbed to more than $800 billion.

Intel’s rise from memory startup, to accidental microprocessor pioneer, to the backbone of the x86 empire—and then to a company fighting to reclaim its footing—may be the defining corporate saga of modern computing.

And it’s not finished.

II. The Fairchild Eight & Silicon Valley Origins

In 1956, William Shockley—the co-inventor of the transistor—won the Nobel Prize in Physics. Fresh off that validation, he set up a semiconductor lab in Mountain View, California, and began recruiting top young talent. Two of the people he pulled in would later become central characters in the story of Intel: Robert Noyce, a charismatic physicist from small-town Iowa with an effortless way of making hard ideas feel simple, and Gordon Moore, a quiet, methodical chemist from the coastal town of Pescadero who trusted measurements more than charisma.

Shockley’s problem wasn’t his intellect. It was everything else.

He was paranoid, erratic, and famously difficult to work for. He subjected employees to lie detector tests. He publicly humiliated people in meetings. And he insisted on betting the lab’s future on germanium-based semiconductors, even as his own researchers became convinced silicon was where the world was going.

Within a year, eight of Shockley’s best scientists had had enough.

On September 18, 1957, they resigned together—the group that would go down in Valley lore as the “Traitorous Eight.” Quietly, they had already lined up funding from Sherman Fairchild, an East Coast industrialist, and they set up shop in a rented building in San Jose. Fairchild Semiconductor was born.

That move didn’t just create a company. It created a template.

In 1950s corporate America, leaving a prestigious employer to start a rival was close to unthinkable. The Traitorous Eight made it thinkable—and then made it normal. The cultural DNA of Silicon Valley starts here: job-hopping as a virtue, not a sin; loyalty to the mission, not the institution; risk-taking as a career move; and the idea that if your company couldn’t move fast enough, you could simply build a new one—especially if you could persuade a financier to back you.

At Fairchild, Noyce and Moore didn’t just succeed. They helped invent the industry.

In 1959, Noyce independently developed the silicon-based integrated circuit, landing on essentially the same breakthrough as Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments, but with a manufacturing approach that could actually scale—built on the planar process pioneered by Jean Hoerni, one of the Eight. The integrated circuit changed electronics from craftwork to industry. Before it, building complex devices meant stitching together individual components by hand. After it, you could fabricate whole circuits directly onto a slice of silicon.

Moore, meanwhile, led Fairchild’s research and development with his signature calm. In 1965, he published a paper in Electronics magazine that included a simple observation with enormous consequences: the number of components that could be economically placed on an integrated circuit was doubling at a steady pace—roughly every year at first, later revised to about every two years. It became Moore’s Law, and the industry didn’t just admire it. It organized itself around it.

Moore’s Law wasn’t a law of physics. It was more like a drumbeat—an expectation that forced constant reinvention. A goal that became a strategy. A prophecy that engineers made true by sheer will, capital spending, and iteration.

And Fairchild, for a time, was the place where that future arrived first.

But there was a catch: Fairchild Semiconductor wasn’t an independent company. It was a subsidiary of Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corporation, a conglomerate based in Syosset, New York. And this is where a familiar pattern in tech history shows up early: the parent company didn’t fully understand what it owned.

Fairchild Camera treated semiconductors like a cash machine. The chip division generated profits, and those profits got siphoned off to support other parts of the conglomerate—businesses that weren’t growing as fast and didn’t require the same relentless reinvestment. Inside the semiconductor operation, the people doing the inventing watched their work bankroll projects they didn’t believe in.

Noyce, who rose to become Fairchild Semiconductor’s general manager, pushed for more investment in research and development. Again and again, he ran into resistance.

By 1967, Noyce and Moore had a problem that wasn’t technical. It was structural. They had helped create the integrated circuit industry, articulated its governing rhythm, and built the most innovative semiconductor company in the world. But they didn’t control its destiny. The upside of their work flowed to a corporate parent three thousand miles away that saw their division as a line item, not the future.

So they started thinking the way the Traitorous Eight had thought a decade earlier: if you can’t build the future where you are, you leave.

This time, they wouldn’t need to convince a corporate sponsor to fund the dream. They had something even more valuable than a business plan.

They had their reputations. Their names. And a track record that made investors believe the next company wouldn’t just be another semiconductor startup.

It would be the one that mattered.

III. Intel's Founding: The Anti-Fairchild (1968)

Arthur Rock got the phone call in the summer of 1968. A decade earlier, Rock had helped the Traitorous Eight get Fairchild off the ground. In the process, he’d helped invent the modern venture capital model: back exceptional technical talent early, then let the compounding do the work.

This time it was Bob Noyce on the line. He and Gordon Moore were leaving Fairchild to start a new company—one aimed squarely at semiconductor memory.

Rock didn’t ask for a business plan. He didn’t need one. He put together a short, one-and-a-half-page flyer that was basically a statement of belief: Noyce and Moore are doing it again. Within two days, he’d raised $2.5 million from a small circle of investors. The round was oversubscribed; people were scrambling to get a piece. The real equity, as Silicon Valley would later love to say, was in the people.

Noyce and Moore incorporated on July 18, 1968. At first, they called the company NM Electronics—functional, forgettable, and not remotely ambitious enough for what they had in mind. They quickly landed on a new name: Intel, short for “integrated electronics.” Noyce thought it “sounded sort of sexy.”

There was, of course, a catch. A Midwestern hotel chain already held a similar name. So Noyce and Moore did what founders do: they bought the rights. Even the branding required negotiation.

On that same day, a thirty-one-year-old Hungarian-born chemical engineer named Andrew Grove showed up for work. Grove wasn’t a founder, and he didn’t get founder’s equity. He was employee number three, hired as Intel’s director of engineering. But over time, he would become arguably the most consequential leader Intel ever had.

Grove’s story reads like an American epic. Born András István Gróf in Budapest in 1936, he survived the Nazi occupation as a Jewish child by living under false papers. He survived the Soviet takeover, too—and when the 1956 Hungarian Revolution collapsed, he fled on foot across the border into Austria. He arrived in the United States with almost nothing, learned English, enrolled at the City College of New York, finished at the top of his class, and went on to earn a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from UC Berkeley.

By the time he walked into Intel, Grove had already lived through the kind of instability that rewires a person. It left him intense, unsentimental, and allergic to complacency. Years later he would title his book Only the Paranoid Survive, and it wasn’t a metaphor.

Soon after, Leslie L. Vadász—another Hungarian émigré—joined as Intel’s fourth employee. That early Hungarian core mattered. It reinforced a culture where rigor beat rank, and where debate wasn’t a breach of etiquette; it was how you got to the truth.

Together, these leaders formed what would become known as the Intel Trinity, and the division of labor was almost too perfect.

Noyce was the visionary and the face—the person who could sell a future to engineers in the morning and investors in the afternoon. People called him the “Mayor of Silicon Valley,” and he earned it.

Moore was the technologist—the quiet force who understood the underlying science and could translate it into what mattered: a roadmap.

And Grove was the operator—the person who turned ambition into repeatable execution, building the manufacturing discipline and management systems that would let Intel scale.

From day one, Intel set out to be the anti-Fairchild.

Fairchild had become hierarchical and slow. Intel would stay flat and meritocratic. No reserved parking spots. No executive sanctuaries. Executives worked in cubicles. Noyce ate lunch in the same cafeteria as everyone else, because that was the point: the work mattered more than the org chart.

Grove pushed the culture further with a principle he called “constructive confrontation.” Anyone could challenge anyone—provided they brought data. Decisions weren’t supposed to be won by volume or seniority; they were supposed to be won by evidence. This wasn’t feel-good egalitarianism. It was a strategy, learned the hard way from watching Fairchild’s best ideas die in the layers between the lab and the executive floor.

And most importantly, the company’s prime directive was clear: keep pushing. Keep investing. Keep moving the frontier. Intel would bet on next-generation process technology again and again, even when it hurt in the short term.

For decades, that commitment would be a superpower.

Much later, it would also become a risk.

IV. The Memory Years: Early Products & Japanese Competition (1969-1985)

Less than a year after Intel opened its doors, it shipped its first product: the 3101 static random-access memory chip, or SRAM. It stored just 64 bits—sixty-four ones or zeros. By today’s standards, that’s almost comical. But in 1969 it was a statement: solid-state memory could be fast, reliable, and manufactured at scale. And it was good enough to start displacing the magnetic core memory that had dominated computers for two decades.

The real inflection point arrived in 1970 with the Intel 1103: the world’s first commercially available dynamic random-access memory chip, or DRAM.

The difference between SRAM and DRAM is the difference between sturdy and cheap. SRAM hangs on to data using a more complex circuit—several transistors per bit. DRAM stores each bit in a tiny capacitor that slowly leaks, so it has to be refreshed constantly. Like a bucket with a pinhole: it works, but only if you keep topping it off.

That sounds like a downside, but it’s the whole game. DRAM needed far fewer components per bit, which made it dramatically cheaper to manufacture at a given capacity. The 1103 held 1,024 bits—about one kilobit—and it helped kick off a massive shift in the industry as mainframes began moving away from magnetic core memory toward semiconductor memory.

The 1103 didn’t just succeed. It took over. By 1972, it was the best-selling semiconductor chip in the world. DRAM quickly became Intel’s main business, and at one point it generated more than 90 percent of the company’s revenue. Intel wasn’t merely participating in the memory market; it was shaping what the memory market was.

And DRAM did something else that mattered just as much: it trained Intel.

Memory chips are a forcing function. They’re high-volume, brutally cost-sensitive, and they reward whoever can manufacture with the best yields and the tightest process control. Intel’s ability to shrink transistors and pack more density onto a wafer—generation after generation—was powered by DRAM. Memory was the technology driver that pushed the company down the learning curve.

Through the 1970s, Intel expanded its memory lineup and its manufacturing footprint. The company went public in 1971. The industry boomed. Intel’s revenue rose from $4 million in 1970 to $900 million by 1981. From the inside, it looked like the plan was working perfectly: build the best process technology in the world by shipping an ocean of memory chips.

Then the ocean turned.

In the early 1980s, Japanese semiconductor manufacturers—NEC, Hitachi, Fujitsu, Toshiba—came hard for DRAM. They weren’t just competent. They were coordinated. Backed by subsidies and support from Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry, they invested aggressively in modern fabrication capacity and paired it with an intense focus on manufacturing quality. Lower defect rates meant better yields. Better yields meant lower costs. And in a commodity market, lower cost is destiny.

Prices collapsed—by as much as 80 percent. Intel’s DRAM market share, once commanding, fell sharply. By 1984, the DRAM business was losing money, and it wasn’t a contained problem. It was dragging down the whole company. Revenue stopped climbing. Profits thinned. For the first time, Intel had to lay people off.

Inside Intel, the crisis immediately became a fight over identity.

The memory team had built the company. Memory had paid for the fabs, trained the workforce, and generated almost all the revenue for years. Their argument was straightforward: fight. Invest in the next generation of DRAM, regain the lead, and out-engineer the competition. Abandoning DRAM, they believed, wasn’t strategy. It was surrender.

But while that debate raged upstairs, something quietly shifted downstairs—on the factory floor.

By the middle of 1984, some middle managers began steering Intel’s process decisions toward technologies that favored logic chips, like microprocessors, rather than memory. They weren’t staging a coup. They were responding to what the numbers were already saying: microprocessors carried better margins, and the manufacturing choices that made microprocessors shine weren’t the same ones optimized for DRAM.

In other words, the fabs were drifting toward Intel’s future before Intel’s leadership had fully admitted the present was broken.

By the end of 1984, top management couldn’t ignore it anymore. Winning back DRAM leadership would require a major bet: at least $100 million for a new fabrication line to build one-megabit chips. And even if Intel spent it, there was no guarantee it could earn it back under relentless Japanese pricing pressure.

The memory team pushed for the investment. Management agonized. And then they said no.

That single decision effectively ended Intel’s path as a DRAM company. The company that had helped invent the modern memory industry was preparing to walk away from it.

And as brutal as that sounds, it created space for something that had been growing, almost awkwardly, in the background—something that began as a side project, and was about to become the foundation of a computing empire.

V. The Accidental Microprocessor: 4004 to 8086 (1971-1978)

In 1969, a Japanese calculator company called Busicom showed up at Intel with what sounded like a great piece of business: a contract to design a chipset for a new line of desktop calculators. The spec called for a dozen different chips, each one hardwired to do its own job. It was complicated, but it was familiar work.

Then a young Intel engineer named Marcian “Ted” Hoff suggested something that didn’t fit the normal categories.

Instead of twelve custom chips, what if Intel built one general-purpose chip that could be programmed to do all twelve jobs?

That idea seems obvious now, because it’s basically the definition of a microprocessor. But in 1969, it was a leap. Hoff wasn’t proposing a better calculator chip. He was proposing a tiny, programmable computer—logic that lived in software and instructions, not etched forever into specialized silicon. The difference between “this thing can only ever do what we built it to do” and “this thing can do whatever we can imagine, as long as we can code it.”

Inside Intel, the reaction was mixed. The company was a memory business. Microprocessors looked like an engineering detour. But Noyce and Moore saw enough upside to let Hoff run with it.

To make it real, Intel pulled together a small group: Federico Faggin, an Italian physicist who joined Intel specifically to lead the project’s design and implementation, and Stanley Mazor, who helped shape the instruction set. Out of that team came the Intel 4004.

In November 1971, Intel released the 4004: the world’s first commercially available microprocessor. It was a 4-bit chip, running at 740 kilohertz, with about 2,300 transistors—tiny by modern standards, but revolutionary for the moment. And it delivered a mind-bending implication: computing power that had once demanded a room could now sit on a sliver of silicon.

But the story had a catch that could have killed the whole category before it even started: Busicom owned the design.

Intel had built the chip as a custom job. The intellectual property belonged to the customer.

This is where Hoff’s impact went beyond engineering. He pushed Intel’s leadership to buy the rights back. His argument was simple and audacious: the microprocessor wasn’t a calculator part. It was a platform. It could go into traffic systems, industrial controllers, instruments—anywhere electronics needed brains.

Intel agreed, and negotiated with Busicom to reacquire the rights. Busicom, under financial pressure, accepted a deal where Intel lowered the price on the calculator chips, and in return Intel promised not to sell the 4004 to other calculator makers. For everything else, Intel was free to market the chip as its own.

It’s hard to overstate what that meant. Intel had effectively purchased the right to invent an industry.

The 4004 led to the 8-bit 8008 in 1972, and then the far more capable 8080 in 1974. The 8080 went on to power the Altair 8800, the hobbyist machine that inspired Bill Gates and Paul Allen to write their first version of BASIC—and eventually to found Microsoft. In hindsight, that’s a straight line into the personal computer revolution.

Inside Intel, though, microprocessors still weren’t the center of gravity. Memory was. These chips were exciting, but they weren’t yet the thing Intel thought it was building.

Then, in 1976, Intel’s microprocessor roadmap hit a wall.

The company had been working on an ambitious next-generation chip called the iAPX 432, a complex 32-bit processor intended to be Intel’s flagship for the 1980s. It slipped. It got expensive. Technical problems piled up. And customers don’t wait politely while you debug the future.

Intel needed something shippable, fast—something to hold the market until the 432 was ready.

So Intel built a “stop-gap.”

The result was the 8086: a 16-bit processor designed quickly, with an eye toward being somewhat compatible with the 8-bit 8080 so existing customers could migrate without rewriting everything from scratch. Stephen Morse led the design team, which worked under a tight schedule and limited resources. Intel introduced the 8086 in 1978.

At the time, it wasn’t treated like destiny. It was treated like a bridge.

And yet, this is the chip family that would eventually become the foundation of the x86 architecture—the computing standard that would dominate personal computing for decades.

While the engineers were trying to keep the roadmap alive, Intel’s sales and marketing teams were fighting a different war. In the late 1970s, Motorola’s 68000 was gaining momentum, and Intel was losing key design wins. So in 1979, Intel went on offense with an internal campaign called Operation Crush: an all-out push to win two thousand design wins for the 8086 and its companion chips in a single year. The name wasn’t subtle. Intel wanted to crush Motorola.

Operation Crush, led by Intel’s vice president of marketing Bill Davidow, marked a shift in how Intel sold microprocessors. This wasn’t just “here’s a chip.” Intel began pitching a complete solution: development tools, support chips, software, training—everything an engineering team needed to bet their product on Intel.

One of those wins, landed by a field sales engineer named Earl Whetstone in Florida, would end up mattering more than the other 1,999 combined.

VI. The IBM PC Deal: Lightning Strikes (1980-1981)

In 1980, Earl Whetstone was covering Intel’s Florida sales territory when he heard something that didn’t sound like IBM.

An IBM engineer named Philip Donald “Don” Estridge had been authorized to shop outside the company for key components for a new product. For IBM—famous for doing everything itself, from processors to peripherals—that was practically heresy. If IBM was willing to buy an external CPU, then whatever they were building wasn’t just another internal project. It was urgent.

Estridge couldn’t tell Whetstone exactly what he was working on. But Intel’s sales team didn’t need a full briefing to understand the shape of the opportunity. They worked the relationship. And what made it possible was geography.

Estridge’s team was based in Boca Raton, Florida, far from IBM’s headquarters in Armonk, New York. That distance wasn’t accidental. IBM leadership had set this up as a skunkworks: a small group with unusual autonomy, operating outside the normal bureaucracy, with a brutal deadline—about a year—to deliver IBM’s first personal computer. The team started small, roughly a dozen engineers, and they were allowed to do something IBM almost never did: assemble a system using off-the-shelf parts.

Estridge’s logic was simple. If IBM tried to design everything from scratch, it would take years. If they bought proven components, they could ship in months. And in a market that was starting to move fast, speed was the entire point.

IBM ultimately chose Intel’s 8088, a variant of the 8086 with an 8-bit external data bus instead of a 16-bit bus. Technically, that made it something of a compromise. The narrower bus meant it moved data less efficiently than a full 8086.

But this wasn’t a beauty contest. Intel could supply enough chips, and it could do it at the right price. Just as importantly, the 8088’s 8-bit bus let IBM build the rest of the machine more cheaply, using less expensive support chips and simpler circuit boards. It was a decision optimized for cost, availability, and time-to-market—not bragging rights.

On August 12, 1981, IBM launched the IBM Personal Computer, officially the model 5150. It ran on an Intel 8088 at 4.77 megahertz, shipped with 16 kilobytes of RAM expandable to 256 kilobytes, and ran PC DOS—an operating system IBM licensed from a small Seattle company called Microsoft. The base price was $1,565, roughly $5,200 in today’s dollars.

But the processor speed and the price weren’t the part that rewired the industry.

In its rush to ship—and with deep confidence that the IBM logo was protection enough—IBM made the machine “open.” The technical specs were published. The BIOS, the basic input/output system that interfaced with the hardware, could be reverse-engineered and cloned.

IBM assumed no one would dare sell a non-IBM personal computer. That the brand would make the platform uncopyable.

It was wrong.

Within a couple of years, IBM-compatible PCs were everywhere. Companies like Compaq, Dell, and dozens of others sold machines that ran the same software and used the same Intel processors, often at lower prices. “IBM-compatible” became the standard more than the IBM PC itself. And in 1982, Time magazine named the IBM PC “Machine of the Year,” a sign of how quickly personal computing had gone mainstream.

IBM had accidentally created a platform. And the real winners weren’t the companies assembling the boxes. The winners were the companies that controlled what every box had to contain.

Intel controlled the processor. Microsoft controlled the operating system. The clone makers competed on price and distribution, grinding their margins down. But every clone still needed an Intel CPU and a Microsoft OS, and the easiest way to keep customers happy was to preserve compatibility with the growing universe of existing software. Switching processors or operating systems meant breaking that compatibility—and that was a painful tax no one wanted to pay.

That dynamic set the stage for “Wintel,” the Microsoft-and-Intel pairing that would define personal computing for decades. It wasn’t carefully orchestrated. It was the structural consequence of one hurried decision by IBM.

For Intel, this deal changed what the company was. The microprocessor was no longer a promising side business. It was the growth engine. The 8088 led to the 80286 in 1982, the 80386 in 1985, and the 80486 in 1989—each generation pulling more developers, more software, and more customers into the orbit of x86 compatibility.

Intel was building a moat, even if it didn’t fully see it yet.

Because internally, Intel still thought of itself as a memory company that happened to make microprocessors.

That belief was about to break.

VII. Grove's Strategic Inflection Point: Exiting Memory (1985-1987)

That “revolving door” exchange between Grove and Moore didn’t happen in a calm strategy offsite. It happened in the middle of real corporate trauma.

Intel’s memory business—the business that had once been Intel—was bleeding. Japanese manufacturers had pushed quality to a level Intel couldn’t match, with defect rates five to ten times lower. They’d built enormous, modern fabrication capacity with government support, and they were pricing DRAM so aggressively that it sometimes looked like they were willing to lose money just to take the market.

Inside Intel, the argument over what to do next was turning into a slow-motion breakup.

The memory organization—full of early Intel engineers who had lived through the 1103 days and built the company’s manufacturing pride—looked at the microprocessor group as a bunch of overeager newcomers who didn’t understand the “real” Intel. The microprocessor team, newly confident from the IBM PC’s momentum, saw DRAM as a commodity trap and argued the future was logic: higher value, more differentiation, and a clearer path to profit. It wasn’t an abstract debate. It was a civil war fought in meetings, in hallway conversations, and in the quiet politics of who got the best people and the newest tools.

And then there was the hardest part: walking away from memory wasn’t just a portfolio choice. It was an identity crisis.

Intel had been founded to make memory chips. Moore’s Law, in its earliest form, was about density—how many components you could pack onto a chip, a framing that mapped naturally onto memory. The company’s engineering habits, its manufacturing instincts, and its customer relationships had been built around memory. Telling Intel it was getting out of memory wasn’t like dropping a product line.

It was like telling a winemaker the vineyard was switching to corn.

But Grove didn’t lead with nostalgia. He led with the numbers. Memory was losing money, and the losses were getting worse. Intel had already gone through painful layoffs. And the path to “winning back” DRAM meant committing enormous capital to new fabrication capacity with no guarantee Intel could ever beat Japanese pricing in a market that was becoming brutally efficient.

So after that conversation, Grove and Moore did the thing most companies can’t bring themselves to do: they made the call, and they made it real.

Intel would exit DRAM. The company would redeploy its best engineers, its manufacturing capacity, and its capital toward microprocessors. It was a bet-the-company move, made at the exact moment the company least felt like it could afford one.

The transition was ugly. Memory lines were shut down or converted. Engineers who’d spent their careers on memory design were told to retrain for microprocessors or move on. Some left in frustration. Others adapted. And over time—slowly, painfully—the center of gravity inside Intel moved from “memory company that also sells CPUs” to “microprocessor company, period.”

In 1987, Grove became CEO, succeeding Moore. Over the next eleven years, he oversaw Intel’s transformation from a semiconductor company fighting for relevance into one of the most powerful and profitable firms in technology.

Out of the DRAM crisis, Grove also crystallized the management ideas he’d become famous for.

He framed moments like this as strategic inflection points: times when the rules of the game change, and the danger isn’t making the wrong move—it’s acting like the old rules still apply.

He captured his default posture toward success in a phrase that became Intel scripture: “only the paranoid survive.” Not paranoia as panic, but paranoia as vigilance—the discipline of assuming that yesterday’s advantage is already expiring.

And he doubled down on constructive confrontation: the idea that truth comes from vigorous, evidence-based debate, and that the organization should be built to surface disagreement rather than bury it.

He also helped develop and popularize OKRs—Objectives and Key Results—adapting Peter Drucker’s management-by-objectives into a system that forced clarity about what mattered and how progress would be measured. Decades later, companies like Google, LinkedIn, and Twitter would adopt OKRs, and Grove’s influence would quietly spread far beyond Intel.

In May 1998, Grove stepped down as CEO and handed the role to Craig Barrett, after being diagnosed with prostate cancer a few years earlier. He remained chairman until 2005. By then, the transformation was complete: Intel had fully become a microprocessor company—focused, aggressive, and engineered to win.

And next, Intel was about to do something no semiconductor company had ever done before.

It was about to make a component into a household brand.

VIII. The x86 Wars & Intel Inside (1988-1995)

By the late 1980s, Intel had a strange new problem: the biggest threat to x86 was coming from inside the x86 world.

IBM, when it picked the 8086 and 8088 for the first PC, had insisted on a second source. It didn’t want to be dependent on a single supplier. So Intel—grudgingly—agreed to let Advanced Micro Devices, AMD, manufacture Intel-compatible processors under license.

That deal made sense for IBM. For Intel, it was a seed they would spend years trying to uproot.

The breaking point arrived with the 386. Intel didn’t just want the next generation to be better; it wanted to be the only place customers could buy it. So when the 386 launched, Intel refused to license it to AMD.

AMD argued that the old second-source agreement covered future x86 processors too. Intel argued it didn’t. And what followed was a long, grinding legal war that stretched for years and eventually reached the Supreme Court of California.

While the lawyers fought, AMD did what it had to do to survive: it started building its own x86-compatible chips through clean-room reverse engineering. One team documented how Intel’s processors behaved without looking at the original designs. Another team, working from that documentation alone, built a compatible chip from scratch.

And AMD wasn’t the only one taking a swing.

Cyrix, which emerged from a Texas Instruments-owned design shop, entered the market selling 386 and 486 clone processors at steep discounts. Suddenly, Intel wasn’t just defending itself against a rival. It was defending itself against an entire class of competitors—companies that could undercut Intel by copying what Intel had already spent years and billions to develop.

The clone wars were on.

Intel’s response was both ruthless and elegant. It fought in court. It moved faster on product cycles, trying to stay one step ahead so competitors were always cloning yesterday’s chip. But Intel also did something even more important: it changed the battlefield.

In 1991, Intel launched Intel Inside.

The idea was wildly counterintuitive. Intel was a component supplier. It sold to PC makers, not consumers. And now it wanted the average person shopping for a family computer to care deeply about the processor—something they couldn’t see, couldn’t touch, and usually couldn’t explain.

It was like a steel company trying to convince homebuyers to demand a particular brand of rebar.

Intel Inside worked because it wasn’t just a slogan. It was a financial machine.

Intel offered PC manufacturers a deal: if you put the Intel Inside logo in your ads and on your machines, Intel would reimburse part of your advertising spend—sometimes up to half. For PC makers, it was effectively subsidized marketing. For Intel, it was a way to turn its name into a proxy for quality, and to make “Intel” something customers asked for.

And once customers started asking for Intel, the clone makers faced a much harder job. Even if a Cyrix or AMD chip was cheaper, switching away from Intel now carried a new risk: would customers see your computer as the off-brand version?

The campaign landed with extraordinary force. By the mid-1990s, the Intel Inside jingle—those five notes—had become one of the most recognizable sounds in advertising. Consumers developed preferences for Intel-powered PCs even when they couldn’t describe what the processor actually did. Intel was spending more than $100 million a year to make that happen, but it was buying something priceless: leverage over the entire PC industry.

At the same time, the Wintel era locked into place. Windows became the default operating system for the PC universe, and Intel became the default engine underneath it. The two companies reinforced each other in a flywheel: new versions of Windows demanded more computing power, which pushed customers toward new Intel processors, which enabled more ambitious software, which made Windows more valuable.

The business results followed. From 1991 through 1996, Intel’s revenue grew dramatically to $20.8 billion, with profit margins near 25 percent. Intel was no longer just a great semiconductor company. It was becoming one of the most consistently profitable power centers in tech.

Of course, there was a looming intellectual threat, too—one that, in theory, could have broken the spell.

Computer architects were increasingly enamored with RISC, or Reduced Instruction Set Computing, a design philosophy built around simpler instructions that could be executed faster. x86 was CISC—Complex Instruction Set Computing—loaded with more elaborate instructions. If RISC chips were cleaner and faster, why would the world keep dragging around all this x86 complexity?

Intel’s answer was classic Intel: don’t abandon compatibility, absorb the best idea.

Starting with the Pentium Pro in 1995, Intel effectively built a RISC-like core inside an x86 processor. The chip would accept x86 instructions from software, then translate them internally into smaller, simpler micro-operations that could run more efficiently. Backward compatibility on the outside. Modern performance on the inside.

And that, ultimately, was the trick of this entire era.

Intel’s true moat wasn’t that x86 was the most elegant architecture. It was that the world had standardized on it. The growing mountain of x86 software—and the expectation that tomorrow’s machine would still run yesterday’s programs—created switching costs so high that “better” alternatives struggled to matter.

Intel wasn’t just selling silicon.

It was selling permanence.

IX. Peak Dominance: The Pentium Era (1993-2000)

If Intel’s moat in the early 1990s was permanence, the Pentium made that permanence feel like a brand you could hold in your hands.

On March 22, 1993, Intel launched the Pentium processor, and with it, a consumer marketing revolution. The name choice wasn’t cosmetic; it was defensive strategy. Until then, Intel had been marching forward with numbers: 8086, 286, 386, 486. The problem was that numbers can’t be trademarked. AMD could sell a “386” or “486” and, legally, Intel couldn’t stop them.

A word, though? A word could be owned.

“Pentium” was Intel’s first truly trademarkable CPU name—built from the Greek “pente,” meaning five, paired with the “-ium” ending to make it sound like a fundamental element. And that was the point. Intel wasn’t trying to sound like a part supplier anymore. It was trying to sound like the ingredient.

The launch campaign made that unmistakable. Intel went far beyond the Intel Inside stickers and co-op advertising. It ran TV commercials with bunny-suited clean-room technicians dancing to disco music, turning chip manufacturing into something almost glamorous. The subtext was loud: this isn’t a commodity component. This is the beating heart of the most important machine in your life.

Then came the stumble that proved just how well the branding had worked.

In October 1994, Thomas Nicely, a mathematics professor at Lynchburg College in Virginia, discovered the Pentium produced incorrect results for certain floating-point division operations. The flaw became known as the Pentium FDIV bug. It affected only a tiny slice of use cases, with errors occurring extremely rarely—perhaps once in every nine billion random divisions.

But Intel didn’t respond like a consumer brand. It responded like an engineering company.

At first, it downplayed the issue, saying the bug was inconsequential for most users. Replacements would be offered only to customers who could show they were affected. That might have sounded reasonable inside Intel. Outside Intel, it sounded like the world’s most important chip company was telling people to stop asking questions.

And now there was a new accelerant: the internet. Newsgroups and early web forums turned the story into a rolling punchline. IBM announced it was halting shipments of Pentium-based PCs. Confidence cracked in public.

Grove saw the miscalculation for what it was and reversed course. On December 20, 1994, Intel announced an unconditional replacement policy: any customer who wanted a new chip could get one, no questions asked. Intel took a $475 million write-off—enormous at the time—but contained the damage before it became permanent.

Later, Grove acknowledged the real lesson: Intel was no longer selling only to engineers who understood that complex systems sometimes have flaws. It was selling to consumers, who expected their computers to be as dependable as a toaster. And the fact that a processor bug could make front-page news was itself a milestone. A defect in a DRAM chip would’ve been a footnote. A defect in the world’s dominant CPU was a national story.

The product machine kept moving. After the original Pentium came the Pentium Pro in 1995, the Pentium II in 1997, and the Pentium III in 1999, each delivering major performance gains. At the same time, the PC market was exploding—pulled forward by the rise of the internet, Windows 95 and 98, and falling hardware prices that put computers into hundreds of millions of homes.

In 1997, Time magazine chose Andy Grove as its “Person of the Year,” calling him “the person most responsible for the amazing growth in the power and the innovative potential of microprocessors.” During his tenure as CEO, Grove oversaw a 4,500 percent increase in Intel’s market capitalization—from roughly $4 billion to $197 billion—making Intel the world’s seventh-largest company, with 64,000 employees.

Underneath the branding and the product cycles, Intel’s real weapon was manufacturing. One of the most important systems it built in this era was a methodology called “Copy Exactly!” The idea was almost fanatically simple: once a manufacturing process worked in one fab, Intel would replicate it at other fabs with absolute fidelity. Not just the big things—the equipment and process steps—but every detail, down to settings and even the color of the paint on the walls. The goal was to crush variability. If it worked in Oregon, it should work in Arizona, Ireland, or Israel.

Copy Exactly! helped Intel ramp new processor generations faster and more reliably than competitors who struggled with yields and delays when they tried to stand up new facilities.

By the end of the 1990s, Intel was generating more than $29 billion in annual revenue and had a market capitalization approaching $275 billion. From the outside, it looked unbeatable: the PC market was booming, the internet was creating insatiable demand for computing power, and Moore’s Law kept delivering.

Intel wasn’t just dominant. It looked like one of the most successful companies in the history of capitalism.

And that’s usually when the story starts to turn.

X. The Mobile Miss & New Challenges (2000-2015)

The first real warning sign had a name: Itanium.

In the mid-1990s, Intel teamed up with Hewlett-Packard on something radical—a brand-new 64-bit architecture called IA-64, sold under the Itanium name. The ambition was clear: leapfrog x86 and build the future of high-end servers and workstations on a cleaner, more powerful foundation.

But Itanium ran straight into Intel’s own moat.

It wasn’t backward-compatible with the enormous world of x86 software. To run existing programs, customers either had to rewrite them or rely on emulation—and that emulation was painfully slow. Intel was effectively asking the industry to give up the very thing that had made “Intel inside” so sticky: compatibility.

AMD saw the opening and didn’t hesitate. In 2003, it launched Opteron and Athlon 64, extending x86 to 64-bit while keeping full compatibility with 32-bit software. Customers could get the upside of 64-bit computing without ripping up their codebases. AMD’s approach—AMD64—was the pragmatic evolution Intel should’ve shipped first.

Then came the part that stung. Microsoft adopted AMD64 as the basis for 64-bit Windows, and Intel was forced to follow the market—licensing AMD’s extensions so Intel processors could keep up. The company that created x86 had to take marching orders on x86’s future from its biggest rival.

Itanium hung around for years before fading away, quietly discontinued after reportedly costing Intel billions. A massive bet, and a strategic misread of the ecosystem dynamics Intel itself had helped create.

But even that wasn’t the real disaster.

The catastrophe was mobile.

In 2007, Steve Jobs walked onstage in San Francisco and introduced the iPhone. The device that would become the most important consumer computer ever made didn’t run on an Intel chip. It ran on ARM.

And it wasn’t because Apple never asked.

Intel had been offered the contract for the iPhone’s processor and turned it down. Paul Otellini, who became CEO in 2005, later said the decision was one of his biggest regrets. At the time, Intel’s logic was straightforward: Apple’s projected volume didn’t seem worth the investment, and mobile margins looked thin compared to the rich economics of PC and server CPUs.

The problem was that mobile wasn’t a smaller PC market. It was a different planet.

ARM, originally developed by the British company ARM Holdings, was built around power efficiency. If x86 was a big engine designed for a truck—strong, fast, and thirsty—ARM was a small engine designed to sip fuel all day. That tradeoff didn’t matter much on a desktop plugged into the wall. On a smartphone living and dying by its battery, it mattered more than almost anything.

Intel’s chips delivered performance, but they were power-hungry. ARM chips were efficient enough to make a phone feel fast without draining the battery by lunchtime.

And then the market flipped. Within a few years, smartphones outgrew PCs, and smartphones became the center of gravity in consumer computing. The industry standardized on ARM-based designs. Intel was locked out.

Intel did try to fight its way in. It poured billions into mobile-focused efforts, including Atom processors and specialized tablet and smartphone platforms. None broke through. By 2016, Intel had essentially exited the mobile processor market, and the retreat came with a brutal write-off—roughly $10 billion, a very expensive reminder that missing a platform shift isn’t something you fix with effort alone.

Worse, the consequences kept compounding.

Apple had adopted Intel processors for Macs in 2006, but as Intel’s product cadence slipped and performance gains slowed, Apple grew increasingly frustrated. In 2020, Apple announced the M1: an in-house ARM-based chip manufactured by TSMC. The message was unmistakable. Apple could deliver laptop-class performance with far better power efficiency—without Intel.

Apple’s transition to Apple Silicon became a public humiliation for Intel, but the deeper threat wasn’t just Apple leaving. It was who Apple was leaving with.

Because at the same time Intel was missing mobile, a company it once dismissed was becoming the most important manufacturer in the world: TSMC.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, founded in 1987 by Morris Chang, had pioneered the foundry model—build chips for everyone, at world-class scale, without designing them. For decades, Intel looked down on that approach. Intel owned the full stack, and Intel’s manufacturing was typically a generation or two ahead.

Then, around 2015, Intel’s manufacturing engine started to misfire. Its transition from 14-nanometer to 10-nanometer—something that should have taken roughly two years—stretched out to more than five. TSMC, meanwhile, kept marching: 7-nanometer, then 5, then 3, with a consistency Intel used to embody.

For the first time, Intel no longer held process leadership. TSMC did.

And because TSMC built chips for Apple, AMD, NVIDIA, and much of the rest of the industry, Intel’s rivals suddenly had access to more advanced manufacturing than Intel itself. AMD’s Zen processors, built at TSMC, began beating Intel on both performance and power efficiency.

The old Intel playbook—win through manufacturing excellence and lock in the ecosystem—wasn’t just under pressure anymore.

It was starting to run in reverse.

XI. Modern Intel: Fighting on Multiple Fronts (2015-Present)

By 2020, Intel wasn’t just slipping. It was getting lapped.

The stock had gone nowhere while AMD’s surged. NVIDIA had become the most valuable semiconductor company in the world on the back of the AI boom. Apple, once a marquee Intel customer, had left for its own silicon. And TSMC had taken the manufacturing crown Intel used to treat as its birthright.

So in February 2021, Intel made the kind of hire you make when you want the building to stop shaking: Pat Gelsinger. He was a former Intel executive who’d spent nine years running VMware, and he came back with the aura of a missing chapter being restored. Gelsinger had joined Intel at eighteen as a quality-control technician, climbed through engineering, and had been widely seen as a future CEO before being passed over in 2005. Now he was returning as CEO to try to pull Intel out of its skid.

His plan had a name that sounded like a manifesto: IDM 2.0. It had three big moves. First, Intel would win back process leadership by pouring capital into new fabs and aiming to hit five process nodes in four years—an industry pace that many people considered close to fantasy. Second, Intel would open itself up as a foundry, building chips for other companies the way TSMC does. Third, Intel would finally accept a modern reality it had resisted for decades: it would use external foundries, including TSMC, for some of its own products.

The spending that followed was enormous. Intel announced major fab projects in Ohio, Germany, Israel, and Poland, with planned investments totaling more than $100 billion. Then came the policy tailwind. The U.S. CHIPS and Science Act, signed in August 2022, turned domestic semiconductor manufacturing into a national priority—and Intel into the centerpiece of the push. Intel was initially awarded about $8.5 billion in direct grants and up to $11 billion in loans. When the final award was announced in November 2024, it came to $7.86 billion in direct funding, with $3 billion redirected to the Secure Enclave program for trusted defense manufacturing.

The motivation was bigger than Intel’s P&L. American leaders were increasingly alarmed that so much advanced manufacturing capacity sat in East Asia, especially Taiwan. A disruption there could fracture global supply chains overnight. Intel’s pitch—implicitly and explicitly—was that it could become the anchor for reshoring.

But the turnaround didn’t arrive on schedule.

Revenue fell hard, from $79 billion in 2021 to $63 billion in 2022 and then $54 billion in 2023, as the PC market cooled and AMD kept taking share. The foundry effort—rebranded as Intel Foundry in February 2024—lost more than $7 billion on an operating basis in 2023. Intel’s AI accelerator, Gaudi 3, didn’t meaningfully dent NVIDIA’s grip on the market, and Intel acknowledged it would miss its $500 million Gaudi revenue target for 2024.

Then came the belt-tightening that, a few years earlier, would’ve sounded impossible. In August 2024, Gelsinger announced plans to cut about 15,000 jobs—roughly 15 percent of the workforce—aiming for $10 billion in cost reductions. Intel also suspended its dividend.

The Q3 2024 earnings report was where the story turned from “tough” to “violent.” Intel reported a GAAP loss of $3.88 per share, driven by $15.9 billion in impairment charges. Those included write-downs on fab equipment, a $10 billion deferred tax asset impairment, and a $2.6 billion Mobileye goodwill impairment. This is the kind of quarter that doesn’t just reset expectations. It changes careers.

On December 1, 2024, it did. Pat Gelsinger departed as CEO. The announcement said he “retired,” but reporting indicated the board—led by chair Frank Yeary—had delivered an ultimatum: resign or be removed. The board believed the turnaround was moving too slowly, the spending was too aggressive relative to results, and Intel needed a different approach. Gelsinger later confirmed at a conference in Tokyo that his exit was forced by a “third party.” During his nearly four years in the role, Intel’s stock had fallen about 61 percent.

Intel named two interim co-CEOs: CFO David Zinsner and products chief Michelle Johnston Holthaus. The stock, which had traded near $50 in early 2024, fell below $20 by year-end—down roughly 60 percent. And in November 2024, Intel was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average and replaced by NVIDIA. It was a symbolic gut punch, but also a tidy snapshot of where the industry’s center of gravity had moved.

On March 12, 2025, Intel picked its next CEO: Lip-Bu Tan. The sixty-six-year-old, Malaysian-born executive had run Cadence Design Systems from 2009 to 2021, where the stock rose about 3,200 percent and revenue more than doubled. He also knew Intel from the inside: he’d served on Intel’s board from 2022 until resigning in August 2024, reportedly frustrated with how slowly change was happening under Gelsinger.

Tan signaled a philosophical shift almost immediately. Gelsinger’s posture had been capacity-first: build hard, build fast, and trust demand would catch up. Tan came in as a product-first operator, saying there would be “no more blank checks.” He flattened the organization, removed roughly half of management layers, and had key chip groups report directly to him. He also began personally reviewing and approving major chip designs before tapeout—an intensity that’s rare for any CEO, let alone one running a company of Intel’s scale.

The cuts weren’t theoretical. On day one, Tan pointed to more layoffs beyond the 15,000 already announced. In an April 2025 memo, he wrote that Intel was “too slow, too complex and too set in our ways.” By mid-2025, Intel was on track to end the year with about 75,000 core employees, down from 108,900 at the end of 2024—roughly 34,000 jobs eliminated, about a third of the workforce, in a single year. WARN filings recorded thousands of layoffs across California, Oregon, Arizona, and Texas.

Tan also pulled back on the most ambitious capex plans. He canceled the planned fab projects in Germany and Poland, slowed construction in Ohio to match demand rather than aspiration, and sold a 51 percent stake in Altera to Silver Lake. He shut down the automotive business unit entirely. The message was consistent: fewer bets, clearer returns, less romanticism.

But Intel under Tan wasn’t only a story of cutting. It was also trying, once again, to make the manufacturing narrative real.

Intel began shipping chips built on Intel 18A, a 2-nanometer-class process featuring two major innovations: RibbonFET, Intel’s first gate-all-around transistor architecture, and PowerVia, an industry-first backside power delivery system that routes power underneath the transistors instead of through the same metal layers used for data. The intuition is simple: separate the plumbing from the wiring, and suddenly you have more room to optimize the wiring.

At CES 2026 in January, Intel launched Core Ultra Series 3 processors, code-named Panther Lake, the first client chips built on Intel 18A. Tan called 18A “the most advanced semiconductor process ever developed and manufactured in the United States.” Intel also announced Clearwater Forest, a server processor built on 18A with up to 288 efficiency cores, targeted for the first half of 2026.

Investors, at least for the moment, rewarded the shift. Intel shares rose 84 percent in 2025 and climbed again in early 2026 after Q4 2025 earnings suggested stabilization. Full-year 2025 revenue was $52.9 billion, essentially flat year over year, and non-GAAP EPS came in at $0.42, up from a non-GAAP loss of $0.13 in 2024. The GAAP net loss narrowed dramatically, from $18.8 billion in 2024 to $300 million in 2025. By early February 2026, Intel traded around $48, with a market capitalization near $241 billion.

In August 2025, the CHIPS Act arrangement took a turn that would’ve been hard to imagine a decade earlier. Under the Trump administration, the deal was restructured so the U.S. government took a 9.9 percent equity stake in Intel, receiving 274.6 million shares. Intel received about $5.7 billion in cash earlier than planned, and the government also received options to purchase up to 240.5 million additional shares. It was an extraordinary structure—part industrial policy, part bailout mechanics—and it underscored two truths at once: Intel’s strategic importance, and the scale of help required to fund its comeback attempt.

The foundry remains the wild card.

Intel has landed early signals of demand, including a multiyear, multibillion-dollar commitment from Amazon Web Services for custom chips on Intel 18A, and reports that Microsoft signed a contract for 18A manufacturing. But Tan has also been blunt about where the foundry really is today: “primarily making chips for itself.” He has warned that if Intel can’t secure at least one major external customer for Intel 14A—the node after 18A—Intel may have to exit chip manufacturing entirely.

That warning isn’t drama; it’s math. Fabs can cost $20 billion or more, and they only work economically at high utilization. Intel Foundry has been running at meaningfully lower utilization than TSMC, and in Q2 2025 alone it reported a $3.17 billion operating loss on $4.4 billion in revenue.

And even as Intel tries to stabilize its core, it’s still being pulled toward the next battlefield. In February 2026, Intel hired Eric Demmers from Qualcomm as chief GPU architect, with plans to build discrete GPUs. Whether that’s the kind of necessary expansion Intel needs to stay relevant—or another case of spreading itself too thin at exactly the wrong time—is one of the defining questions of the current era.

XII. Playbook: Lessons from Intel's Journey

Intel’s nearly six-decade run is a case study in how competitive advantage gets built in tech—and how it erodes.

First: strategic inflection points are real, and they don’t wait for you to feel ready. Grove’s great contribution wasn’t just coining the term; it was operationalizing it. Intel lived through one of the cleanest examples in business history when it walked away from DRAM and rebuilt itself around microprocessors. That wasn’t a tweak at the edges. It was a recognition that the game had changed, and that playing harder by the old rules would still end in the same loss.

Second: standards beat “better technology” more often than engineers want to admit. x86 was not destined to win on elegance alone. But once enough software, tools, and developer habits accumulated around it, x86 became the safe choice—then the default choice—then the only choice that didn’t come with a compatibility tax. Intel’s moat wasn’t just the chip. It was the ecosystem that expected the chip to be there. And that’s why the rise of ARM—first in phones, then in laptops, and increasingly in servers—hits Intel at the structural level. It’s not just competition; it’s the weakening of the standard that made Intel Intel.

Third: vertical integration is a superpower until it becomes a trap. For years, Intel’s model—design and manufacturing under one roof—was the envy of the industry because Intel also led the world in process technology. When that leadership slipped and TSMC pulled ahead, the same model turned into a constraint. Fabless rivals like AMD could take great designs to the best factory on Earth. Intel, committed to its own fabs, had to fix manufacturing while also fighting product wars with competitors who didn’t have that burden. The lesson isn’t “never integrate.” It’s that integration only works if you can stay world-class at every layer you’ve chosen to own.

Fourth: the most dangerous misses are platform shifts, because you can’t patch them with effort. Intel missed mobile. It missed the GPU-centered wave that powered modern AI. And it underestimated how quickly ARM-based computing would move from “phones” to “everything.” Each miss followed a familiar logic: the core business was throwing off so much profit that it was hard to justify diverting resources to uncertain markets with lower margins. That’s the innovator’s dilemma in its purest form—rational decisions that compound into strategic irrelevance.

Fifth: culture can be a moat, but it can also rust. Early Intel ran on constructive confrontation, meritocracy, and a kind of bracing honesty that made the company faster and sharper. Over time, scale and success have a way of dulling that edge. What begins as a culture that rewards dissent can quietly become one that rewards alignment. And when the environment changes, a conformity-driven culture is exactly how you miss the early signals.

Finally: in semiconductors, capital is strategy. Leading-edge fabs cost sums that only a handful of companies can even attempt, and the payoff horizon is long. Intel’s willingness to spend aggressively on manufacturing—over and over—was one of its great historical advantages. Today, that same capital intensity is the center of the modern story: can Intel fund a turnaround, regain process leadership, and build a foundry business that attracts real external customers, all without being crushed by the economics of underutilized factories?

That’s Intel’s recurring theme, from memory to microprocessors to foundry ambition: in this industry, you don’t get to be right once. You have to keep being right—expensively—at the exact moments when the future still looks optional.

XIII. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

Intel’s challenges aren’t just cyclical. They’re structural. Look at the battlefield and you see pressure coming from almost every direction at once.

Start with what used to protect Intel: the difficulty of entering the chip business. Building leading-edge factories is still brutally expensive, so “new entrants” in manufacturing remain rare. But the center of gravity has shifted. The fabless model has lowered the barrier where it matters most: chip design. Today, companies like Apple, Amazon, and Google can design their own processors—often on ARM—and send them to TSMC to manufacture. They don’t need Intel’s chips, and increasingly, they don’t even need Intel’s category.

That shift matters because it changes the semiconductor value chain. Intel spent decades as the default provider of compute for the PC era. Now, more of the industry is choosing to be its own compute provider.

Next: customer power. For years, Intel’s customers complained, but they didn’t have credible alternatives at scale. That’s no longer true. AMD is now a real option in PCs, servers, and the cloud, and the biggest buyers have shown they’ll switch when performance, price, or efficiency demands it. AMD’s server share has climbed past 25 percent in some segments after being essentially nonexistent a decade ago, and the trend has been moving in one direction. When hyperscalers can choose between Intel, AMD, their own ARM-based chips, and even NVIDIA’s Grace processors, Intel’s old pricing power starts to look like a historical artifact.

Then comes the most dangerous force: substitutes.

ARM has already won mobile. It’s pushing into laptops via Apple Silicon and Qualcomm’s Snapdragon X series. In data centers, it’s gaining credibility through Amazon’s Graviton line and NVIDIA’s Grace. And on the horizon, RISC-V—open, flexible, and backed by a growing ecosystem—looms as a longer-term threat in embedded and edge computing.

This is the quiet erosion of Intel’s greatest moat. For decades, x86 wasn’t just an architecture. It was the default. Now it’s a choice, and choice is the enemy of monopoly economics. And even if Intel catches up in manufacturing, that doesn’t automatically mean it wins customers. Apple and Qualcomm reportedly declined to use Intel’s 18A technology, a reminder that “having a competitive node” and “winning major designs” are two separate battles.

Competitive rivalry is also as fierce as it has ever been. AMD, led by Lisa Su, has executed one of the strongest turnarounds the semiconductor industry has seen, repeatedly delivering chips that are competitive on performance and attractive on price. NVIDIA has consolidated an extraordinary grip on AI training and inference with its GPU platforms, and its market value has climbed past $3 trillion—roughly twelve times Intel’s. And TSMC’s manufacturing leadership has created an uncomfortable inversion: Intel’s rivals can often access more advanced production technology than Intel can.

Put it into Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers terms, and the bear case is that Intel has lost—or is losing—most of the durable advantages that once made it feel inevitable. Process power slipped to TSMC. Scale economies get harder when PCs stagnate and the foundry business runs far below TSMC’s utilization. Switching costs weaken when ARM and RISC-V keep improving. The x86 ecosystem still has momentum, but it’s no longer expanding as the unquestioned center of computing. Even brand power has faded: consumers care less about an “Intel Inside” sticker than about the lived experience—battery life, responsiveness, AI features—that Apple Silicon and Qualcomm can deliver.

And there’s a human cost that becomes strategic. Intel eliminated roughly a third of its workforce in about two years. Many of those departures included experienced engineers, and in a business like semiconductors, you don’t replace that kind of institutional knowledge on a hiring plan and a slide deck.

The Bull Case

The bull case rests on three pillars: foundry upside, geopolitics, and Lip-Bu Tan.

If Intel Foundry works, it has the potential to become one of the most valuable businesses in semiconductors. TSMC generates more than $80 billion a year with operating margins above 40 percent. Intel doesn’t need to replicate that to matter—capturing even a meaningful fraction, especially from customers who want geographic diversification away from Taiwan, would be transformative. The multiyear, multibillion-dollar AWS commitment, plus reports of an 18A contract with Microsoft, are early signals that real customers are at least willing to test Intel’s pitch.

The second pillar is 18A itself. With Panther Lake shipping on Intel 18A, the company has something it hasn’t had in years: a credible story of manufacturing progress that’s real, not aspirational. RibbonFET and PowerVia are legitimate architectural changes, and Intel claims they offer density and performance advantages versus competing nodes. If outside customers validate 18A at scale, it could kick off the kind of flywheel foundries live on: more volume leading to better yields, leading to better economics, leading to more investment. Intel has also laid out follow-on variants—18A-P and 18A-PT—suggesting it’s building not just a one-node comeback, but a roadmap.

The third pillar is geopolitics—and it may be Intel’s strongest.

The U.S. government taking a 9.9 percent equity stake and committing more than $11 billion in total support isn’t just financing. It’s a declaration that domestic leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing is a national strategic priority. The push to diversify capacity away from East Asia gives Intel a tailwind that isn’t captured in product benchmarks or quarterly margins. Western governments have reasons to want Intel to succeed that go beyond shareholders.

That said, “too important to fail” is not the same thing as “guaranteed to be a great investment.” It means Intel has more runway and more support than most companies would ever get.

Finally, there’s Lip-Bu Tan. His tenure at Cadence—where the stock rose about 3,200 percent and revenue more than doubled—built his reputation as a product-and-execution operator. At Intel, he immediately signaled a different posture from Gelsinger’s build-first approach: cancel projects, flatten management, and enforce what he called “no more blank checks.” The early financial results suggest that discipline is taking hold: the narrowing of losses from $18.8 billion in 2024 to $300 million in 2025 reflects a company that has stopped bleeding at the same rate.

Through Helmer’s lens, the bull case says Intel still has meaningful strategic assets: a deep patent portfolio, x86 intellectual property, and a form of counter-positioning rooted in reality—Intel is uniquely positioned as the only Western company with both the ambition and the existing infrastructure to manufacture leading-edge chips domestically, plus explicit government backing. No startup, and no typical competitor, can recreate that mix.

KPIs to Watch

If you’re tracking whether Intel’s turnaround is real, two metrics matter more than almost anything else.

First, foundry external customer revenue. This is the proof point that separates a manufacturing comeback story from a marketing one. TSMC became TSMC by winning outside customers and running fabs at high utilization. Intel has to show it can do the same—at meaningful scale—and that it can move the foundry business toward breakeven. Tan’s own warning that Intel may have to exit manufacturing if it can’t secure a major Intel 14A customer makes this the single most important KPI on the board.

Second, data center market share versus AMD. Intel’s server dominance has already eroded—from over 90 percent historically to roughly 70 percent in recent years, with AMD above 25 percent in some segments. Whether Intel can stabilize and then claw back share will largely determine if its core franchise remains intact. This is where Intel’s best margins live. Losing share here is far more consequential than a few points of consumer PC share—especially as Clearwater Forest Xeon 6, built on 18A, is targeted for the first half of 2026.

XIV. Recent News

Intel’s Q4 2025 earnings, reported on January 22, 2026, offered a snapshot of a company that had stopped spiraling and started, cautiously, to stabilize. Revenue came in at $13.7 billion, with non-GAAP EPS of $0.15. For the full year, Intel posted $52.9 billion in revenue and non-GAAP EPS of $0.42—an unmistakable improvement versus 2024’s loss. On a GAAP basis, the net loss narrowed sharply, from $18.8 billion in 2024 to roughly $300 million in 2025. One of the brighter spots was the data center business, with Q4 DCAI revenue reaching $4.7 billion, up 9 percent year-over-year. Looking ahead, management guided Q1 2026 revenue to a range of $11.7 billion to $12.7 billion.

The most important corporate development over the past year wasn’t a product launch or a quarterly print. It was the leadership handoff. After Pat Gelsinger’s departure on December 1, 2024, Intel ran under interim co-CEOs David Zinsner and Michelle Johnston Holthaus before naming Lip-Bu Tan as permanent CEO on March 18, 2025. Holthaus departed in September 2025 after more than three decades at Intel, and Tan began reshaping the bench with outside hires, including Kevork Kechichian from Arm for the Data Center Group, Srini Iyengar from Cadence to lead a new Central Engineering Group, and Eric Demmers from Qualcomm, hired in February 2026 as chief GPU architect.

Tan’s overhaul has shown up most visibly in the org chart and the cost structure. Core headcount fell from around 109,000 to about 75,000 through 2025, and Intel eliminated roughly half of its management layers. The company also sold a 51 percent stake in Altera to Silver Lake, shut down its automotive business unit, and canceled planned fab projects in Germany and Poland.

On the product front, Intel used CES 2026 to launch Panther Lake, its first client chips built on Intel 18A. The 18A-based Clearwater Forest server processor is expected in the first half of 2026, and Intel launched Xeon 600 workstation processors in February 2026.

Meanwhile, Intel’s relationship with the U.S. government moved into territory that would’ve sounded implausible just a few years ago. In August 2025, the CHIPS Act arrangement was restructured, with the U.S. government taking a 9.9 percent equity stake in Intel in exchange for about $5.7 billion in accelerated cash funding—bringing total government investment to $11.1 billion.

Customer traction for the foundry effort has begun to materialize, at least in early signals. Intel has pointed to a multiyear, multibillion-dollar AWS engagement for custom chips on Intel 18A, and there have been reports of a Microsoft contract for 18A manufacturing. But the central issue hasn’t changed: Intel still doesn’t have a major anchor external foundry customer, and it has warned it may exit manufacturing if it can’t secure one for Intel 14A.

As of early February 2026, Intel traded around $48 per share, with a market capitalization near $241 billion. The stock rose 84 percent in 2025 after losing nearly 60 percent in 2024—a reminder of how violently sentiment can swing when the market starts believing, even briefly, that the floor has been found.

XV. Links & Resources

- Only the Paranoid Survive by Andrew S. Grove (1996). Grove’s classic book on strategic inflection points and why companies die when they pretend the world hasn’t changed.

- The Intel Trinity by Michael S. Malone. A deep history of Noyce, Moore, and Grove—and how the chemistry between visionary, technologist, and operator shaped Intel.

- Moore’s Law: The Life of Gordon Moore, Silicon Valley’s Quiet Revolutionary by Arnold Thackray, David C. Brock, and Rachel Jones. The best window into Moore as a person and as the industry’s metronome.

- Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology by Chris Miller. Essential geopolitical context for why manufacturing scale, Taiwan, and the TSMC–Intel rivalry now sit at the center of global strategy.

- The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen. A useful lens for understanding how Intel could make “rational” decisions that still led to missing mobile—and later, the GPU-and-AI wave.

- Computer History Museum oral histories with Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, Andy Grove, Ted Hoff, and Federico Faggin. First-person accounts that bring the engineering and internal politics to life.

- Intel Corporation SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, proxy statements), available at investor.intel.com. The primary source for financial and strategic disclosures.

- Swimming Across: A Memoir by Andrew S. Grove. Grove’s personal story—from Hungary to Silicon Valley—and the worldview behind “Only the paranoid survive.”

- The Man Behind the Microchip: Robert Noyce and the Invention of Silicon Valley by Leslie Berlin. A definitive biography of Noyce and the early Valley culture he helped define.

- Intel Q4 2025 and full-year 2025 earnings report (published January 22, 2026). A key checkpoint for the “stabilization” narrative under the post-Gelsinger leadership transition.

- The U.S. CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (Public Law 117-167) and related Department of Commerce announcements on Intel funding. The policy backbone behind Intel’s modern manufacturing push.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music