Illinois Tool Works: The Decentralized Conglomerate

I. Introduction

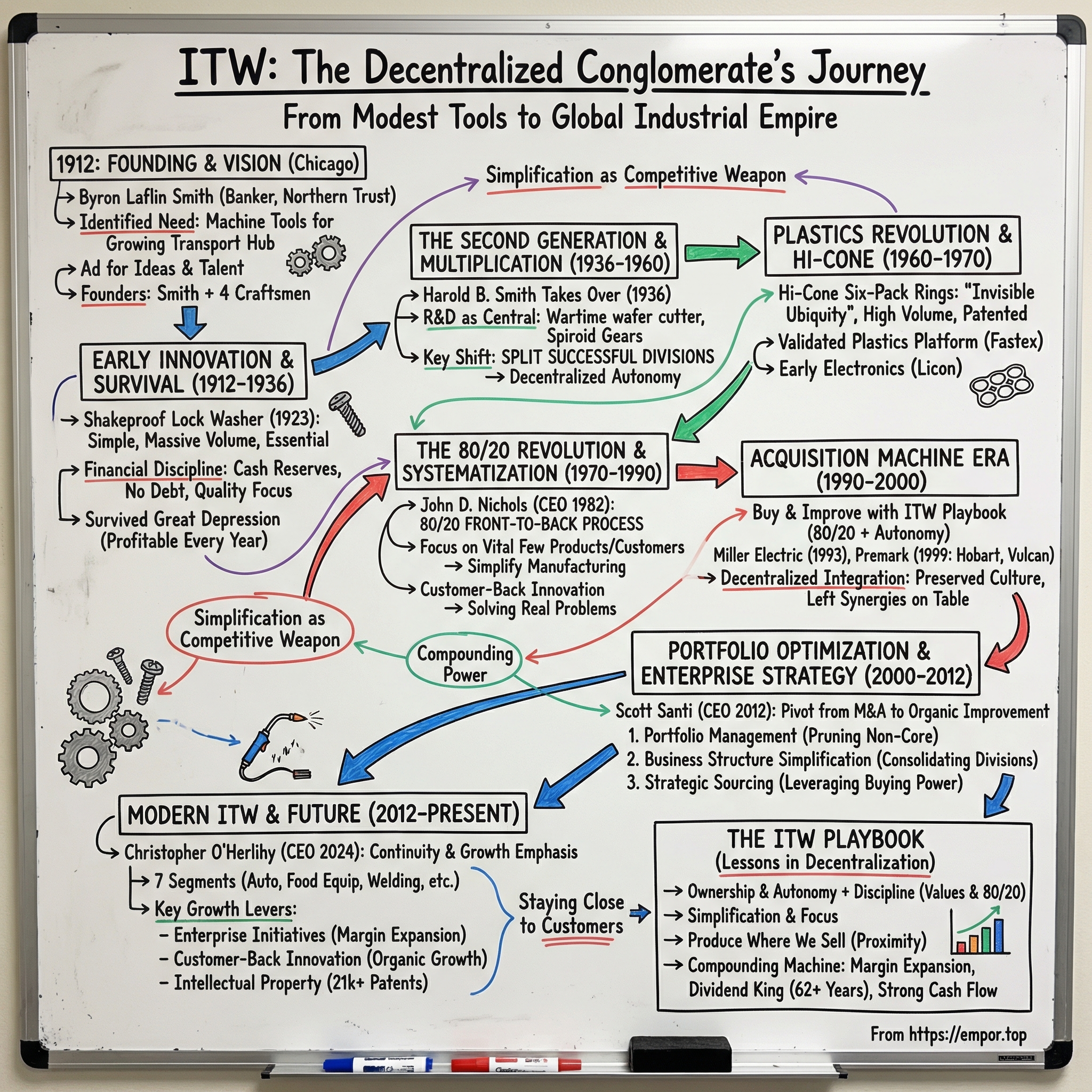

In 1912, in the polished Chicago offices of Northern Trust Bank, a wealthy banker named Byron Laflin Smith sat with a stack of letters and a problem to solve. He’d run an unusual advertisement—one that appeared in The Economist and in trade publications—asking manufacturing workers and inventors to bring him ideas for improving gear grinding and metal-cutting tools. Smith wasn’t looking for a side project. He was looking for a company.

He’d spotted a shift that was hiding in plain sight. Chicago was rapidly becoming America’s transportation crossroads. Rail lines, freight, factories—everything was converging there. And with that came an exploding need for machine tools and industrial parts. The country didn’t just need more steel and more trains; it needed the less glamorous stuff that made the whole system run. Someone had to manufacture it, reliably and at scale.

Out of that one classified ad would grow Illinois Tool Works—a company that now operates in 51 countries, employs about 44,000 people, holds nearly 21,000 patents, and brings in $15.9 billion in annual revenue. But the truly interesting part isn’t the size. It’s the method.

Because ITW didn’t become a Fortune 300 industrial giant by doing what most giants do.

The central question of this story is deceptively simple: how did a modest metal-cutting tool business turn into a sprawling, decentralized empire? The answer runs through three generations of Smith family leadership, a near-obsessive focus on the vital few customers and products that matter most, and a management philosophy that’s so counter to corporate instinct that most companies wouldn’t dare try it.

ITW is a strange kind of conglomerate. While most conglomerates chase scale by centralizing—shared services, big headquarters, uniform processes—ITW went the other direction. It broke itself into smaller and smaller businesses, pushed authority down, and asked each division to act like an owner. But it wasn’t chaos. Alongside that freedom came a disciplined set of tools and expectations. That combination—autonomy plus rigor—helped drive one of the most consistent margin-expansion stories in industrial history, with operating margins rising from the mid-teens to nearly 27% over the past decade.

To understand ITW, you have to follow a few ideas that keep showing up, decade after decade: simplification as a competitive weapon, decentralization as a force multiplier when paired with discipline, and the compounding power of staying close to customers for generations.

We’ll trace the company from its Chicago beginnings in the age of steel and steam, through war and depression, into plastics and electronics, and finally to the modern ITW—a precision-engineered portfolio that makes everything from automotive fasteners to commercial ovens to arc welding equipment.

This is a story about the unglamorous, brutally important components that hold the industrial world together—and the company that learned how to build a business around them better than almost anyone else.

II. Byron Smith's Vision and The Founding Years (1912-1936)

Byron Laflin Smith was not a typical manufacturing founder. He was a banker—born in 1853 in Saugerties, New York—who grew up around finance and institutions. His father, Solomon Smith, had helped establish Merchants’ Loan & Trust as Chicago’s first resident-owned bank. Byron attended the University of Chicago, worked briefly in the family business, and then made his real mark in 1889, when he founded Northern Trust at age 36.

Northern Trust didn’t begin as a towering presence. It opened in a single room in the Rookery Building in The Loop, with just six accounts totaling $137,981. Smith’s style showed up immediately: he refused a salary for the bank’s first six years, working for free until the operation turned profitable. It was conviction, yes—but it was also a philosophy: build carefully, protect the downside, and earn the right to grow.

By 1912, Northern Trust was one of Chicago’s premier financial institutions. But Smith’s attention was pulled by something banking couldn’t fully touch: the industrial machine that was forming around him.

Chicago had become America’s transportation hub. More than 30 railroad lines ran into the city, and the Chicago & North Western Railway alone operated over 10,000 miles of track. Grain markets, meatpacking, and steel were booming. The city’s population surged as workers arrived in waves, chasing opportunity and wages. And every one of those trains, factories, and workshops depended on a quiet, relentless requirement: machine tools—the gears, cutters, and precision components that kept everything moving.

Chicago’s advantage was that it was still new. Unlike older eastern industrial centers, it wasn’t locked into entrenched systems. Its manufacturers could adopt the latest methods and equipment without the drag of legacy processes. The machine shops were among the most modern anywhere, and demand for tooling and parts kept rising.

So Smith did something that only a banker with patience and capital would do: he ran an advertisement. He asked inventors and experienced manufacturing workers to bring him ideas for improving gear grinding and metal-cutting equipment. From the responses, Smith and his four sons—Solomon, Harold C., Walter, and Bruce—chose four men with real shop-floor credibility: Frank W. England, Paul B. Goddard, Oscar T. Hegg, and Carl G. Olson. They were veterans of Rockford, Illinois’s tool-and-die scene, a place known for turning practical know-how into hardware that worked.

With that team in place, Illinois Tool Works launched in a facility at Huron and Franklin Streets in Chicago. The initial capital was just $22,500—small enough to feel almost absurd given what ITW would become. But the recipe was powerful: the Smith family’s financial resources and business discipline, paired with four craftsmen who understood how to build products people would actually pay for.

In the first year, the company posted a profit of $42.94. Not exactly a victory lap. But it was a start—and more importantly, it established a pattern that would run through ITW’s DNA: stay profitable, stay disciplined, and let compounding do the heavy lifting.

Then, in March 1914, Byron Smith died. Leadership at Northern Trust remained with his son Solomon, while Harold C. Smith stepped into ITW. When the company incorporated in 1915, Harold became president—and he turned out to be exactly what the young business needed.

Harold wasn’t a swashbuckling industrialist. He was a careful builder. He expanded beyond metal-cutting tools methodically, pushing into truck transmissions, pumps, compressors, and automobile steering assemblies. The product lineup widened, but the posture stayed the same: deliberate, practical, and anchored in quality.

The most important thing Harold put in place wasn’t a product. It was a financial creed. He insisted on meaningful cash reserves. He avoided debt even when growth would have been easier with leverage. And he invested heavily in modern equipment without compromising on quality. It could look cautious, even stubborn—until the world changed.

The Great Depression broke a huge portion of American industry. ITW didn’t just survive it; the company posted a profit every single year of the 1930s. The cash Harold had insisted on keeping became a shield. It helped ITW maintain a workforce of about 500 workers in Chicago, even as unemployment in the city reached 50% by 1933. That was the lesson ITW would keep relearning: conservatism wasn’t timidity. It was resilience—the ability to keep operating, keep investing, and come out stronger when others were forced to retreat.

World War I had already boosted ITW’s profits and validated the business model, giving the company more resources to expand. By the time Harold C. Smith died in 1936, he had taken ITW from a $22,500 experiment to a respected player in metal-cutting tools, manufacturing components, and industrial fasteners. He’d also earned standing across the broader industrial establishment, serving as a director of both the Illinois Manufacturers Association and the National Association of Manufacturers.

The base was poured. The next generation wouldn’t have to invent stability. They could use it to build something much bigger.

III. The Second Generation and Early Innovations (1936-1960)

When Harold Byron Smith took over as president in 1936, Illinois Tool Works was thriving—but in a fairly traditional way. It was a well-run machine tool company with a strong balance sheet and a reputation for quality. Smith, a Princeton graduate who’d joined the business in 1931, kept the discipline. But he changed the trajectory. Under him, ITW started to look less like a single company and more like a repeatable system for building many companies.

One of the clearest early signals of what that system could become had actually shown up years earlier, in 1923, with the purchase of the Shakeproof Screw and Nut Lock Company. Shakeproof’s hero product was almost insultingly simple: a twisted-tooth lock washer, invented by Richard T. Hosking, that sat under a screw head and kept it from backing out. As the fastener tightened, the washer twisted and flattened like a spring, creating tension that resisted loosening from vibration and corrosion.

Simple product. Massive problem solved.

Early automobiles rattled their way over rough roads, and the industry had a maddening reliability issue: screws worked themselves loose. Shakeproof fixed it. And even though each washer cost less than a penny, the volumes were extraordinary. Every car, truck, and tractor needed dozens of them. Shakeproof grew so fast that it eventually generated more revenue than ITW’s original tool division.

The lesson landed hard: in industrial markets, the biggest businesses can hide inside the smallest parts—especially the ones customers can’t afford to have fail.

That insight guided ITW through the 1930s. The company stayed profitable through the Great Depression while competitors collapsed, leaning on the conservative financial culture Harold C. Smith had established and his son maintained. ITW held the line on quality, avoided layoffs when it could, and came out of the decade with its workforce and reputation intact.

Then came World War II, and ITW’s engineering muscle got a national stage. The company developed an innovative wafer cutter that sped up the rifling process for heavy artillery barrels—cutting the spiral grooves inside gun barrels that make projectiles spin for accuracy. The improvement saved time and accelerated production. ITW produced components for a wide range of wartime equipment, and the company even had representation on the federal War Production Board.

The war also tested operations. Labor was tight. Materials were constrained. And yet ITW increased its cash reserves anyway—another proof point that the culture wasn’t just conservative; it was operationally effective. More importantly, the war years convinced Harold B. Smith that research and development shouldn’t be occasional. It should be central. He began plowing wartime profits into R&D, setting up the postwar expansion into new categories.

In the late 1940s, Smith introduced the organizational move that would become ITW’s signature. When a division worked, he didn’t simply make headquarters bigger to manage it. He split it. The company began breaking successful operations into smaller, autonomous units—each focused on a particular niche, with its own leadership and direct accountability. Instead of scaling with hierarchy, ITW scaled with multiplication.

By the late 1950s, the shift was visible even in the company’s name. “Illinois Tool Works” no longer captured what it had become. So the company started going by its initials: ITW. It was a subtle admission that it was now much bigger than tools.

And the pipeline of new divisions kept coming. In 1955, ITW formed the Fastex Division to produce plastic and metal-plastic fasteners, betting that emerging plastic materials could do things metal couldn’t. In 1959, it created the Licon Division to make electric switches and electromechanical products. Licon’s miniaturization capabilities opened doors to defense work and to the early computer market.

That same year, ITW launched Spiroid, built around the work of a young engineer named Oliver Saari. Saari’s path to ITW was anything but linear: born in Helsinki in 1918, he emigrated to the United States, wrote and published science fiction novels, learned tool-and-die making, and studied mechanical engineering at the University of Minnesota before joining ITW in 1945. His Spiroid gear tackled a classic engineering tradeoff, blending advantages of worm gears and bevel gears while reducing their downsides. The result delivered higher tooth engagement, more torque, tighter packaging, and easier assembly. Spiroid gears ultimately found their way into everything from naval weapons handling systems to commercial jet wing flap actuators.

In 1958, ITW also opened the Illinois Tools Division Gear School, training engineers—including engineers from customer companies—in the intricacies of gearing. It wasn’t just education; it was relationship-building. By teaching customers, ITW embedded itself deeper into their design process and surfaced needs that a conventional sales approach would miss. It was an early glimpse of what ITW would later formalize as customer-back innovation.

By 1960, ITW looked nothing like the $22,500 experiment started on Huron and Franklin. It was a growing collection of focused, autonomous businesses—held together not by a giant central bureaucracy, but by a shared culture of engineering, discipline, and a knack for finding big markets in small parts.

And the next innovation would take that playbook somewhere no one expected.

IV. The Plastic Revolution and Six-Pack Innovation (1960-1970)

Picture a supermarket in 1960. Beer and soda didn’t arrive in the familiar plastic rings we take for granted today. They showed up in heavy paperboard carriers—bulky, costly to produce, and awkward to ship. Beverage companies wanted something better. ITW’s engineers thought the answer wasn’t a new box. It was no box at all.

In the company’s polymer labs, they developed a flexible plastic collar that could hold cans together by their tops. The result was the Hi-Cone carrier: a set of interconnected rings that stretched over can rims, gripped tight, and—almost surprisingly—could handle the weight of a full six-pack. It was simple, light, and strong. It also stacked flat and shipped cheaply, which mattered just as much as the engineering.

For beverage makers, the economics were hard to ignore. Compared to paperboard, Hi-Cone could cut packaging costs by 40% to 60%. And it didn’t take long for the design to spread everywhere. The carrier became so common that it faded into the background of daily life—an object you barely noticed, which is exactly what you want from packaging.

That “invisible ubiquity” was ITW’s sweet spot. Not consumer branding. Not advertising. Just a small, essential component that manufacturers needed in huge volumes—made better, made cheaper, and protected by patents. Once a customer retooled a line around a solution like Hi-Cone, the relationship tended to stick, not because switching was impossible, but because ITW had delivered real, measurable value.

Hi-Cone also did something else: it validated plastics as a platform. The same know-how that produced those rings spilled into other businesses. Fastex, originally built around plastic and metal-plastic fasteners, expanded beyond automotive into markets like packaging, furniture, and appliances. Each new application created tweaks, variants, and improvements—and each improvement was a chance to file another patent. In the 1960s, that flywheel spun faster and faster.

At the same time, ITW kept pushing into categories that looked nothing like its tool-and-fastener roots. Licon’s miniaturization capabilities opened doors to defense, where compact and reliable electronic switches weren’t a nice-to-have—they were mission-critical. The early computer industry needed similar components. These were smaller markets than beverage packaging or automotive, but they rewarded precision and reliability, the kind of manufacturing ITW had been training itself to do for decades.

By the time Harold B. Smith stepped down in 1970, the transformation was unmistakable. What began as a regional machine tool business had become an internationally recognized, diversified industrial manufacturer—still held together by a shared culture, but increasingly powered by autonomous divisions that could find a niche, innovate quickly, and run like owners.

The deeper lesson of the decade wasn’t that ITW invented six-pack rings. It was that ITW had learned how to win with repeated, practical innovation. Not moonshots. Not headline-grabbing products. Just a steady stream of better fasteners, more efficient carriers, more reliable switches—each one patentable, each one defensible in a narrow slice of a market. Multiply that across dozens, then hundreds of product lines, and the competitive advantage started to compound.

ITW now had something more valuable than a hit product. It had a model. The next question was whether that model could scale—and what it would look like once ITW turned it into a machine.

V. The 80/20 Revolution and Decentralization (1970-1990)

Every company that scales runs into the same trap: the bigger you get, the easier it is to lose the scrappy, entrepreneurial edge that got you there. Most businesses respond by building layers—more process, more oversight, more headquarters gravity.

ITW went the other way. It doubled down on small, accountable businesses, and then added something most decentralized companies never manage to build: a shared operating discipline that actually made decentralization work.

That discipline really took shape after John D. Nichols became CEO in 1982. He inherited a company that was already comfortable letting divisions run themselves. Nichols’s contribution was turning that loose philosophy into a repeatable system—what ITW called the 80/20 Front-to-Back Process.

The idea starts with a familiar observation from economist Vilfredo Pareto: most results come from a small number of inputs. Nichols pushed it beyond a nice-to-know statistic and made it an operating mandate. In ITW businesses, it often showed up the same way: a small slice of products drove most sales, a small slice of customers drove most profits, and a small slice of SKUs created most of the manufacturing headaches.

Plenty of executives nod at that… and keep doing everything anyway. Nichols insisted ITW would act on it. The goal wasn’t to grow by adding complexity. It was to grow by eliminating it—so the company could put its best people and resources on the few things that truly mattered.

The 80/20 process wasn’t a slogan; it was work. Divisions built cross-functional teams and went line by line—product by product, customer by customer—to understand real profitability. Then came the hard part: shifting attention and investment toward the best customers and products, while the rest got repriced, simplified, or exited.

Manufacturing felt the impact immediately. Instead of running plants that changed over constantly to accommodate endless variety, ITW pushed for long, efficient runs. Production lines were dedicated to just a handful of products—sometimes only three or four—so changeovers dropped, quality improved, and costs followed. In one documented consolidation, what had been tens of thousands of SKUs was cut down to a fraction of that. The headline wasn’t the exact count. It was the effect: less clutter, more focus, and a business that ran cleaner.

But simplification alone doesn’t win unless you keep innovating. Nichols paired 80/20 with another concept that became core to ITW: Customer-Back Innovation. Instead of starting with a lab project and hunting for a market, divisions started with the customer’s pain. The organization trained itself to listen, to spot recurring problems, and to co-develop solutions with the customers that mattered most.

This is where the structure mattered. ITW’s divisions weren’t waiting for corporate approval or competing for attention inside a giant centralized R&D machine. Each unit could stay close to its market, make decisions quickly, and be judged on results. Division leaders were expected to act like owners: accountable, fast, and practical. That autonomy became a recruiting tool, too—ITW attracted people who wanted to run something real, not manage PowerPoints.

The acquisition strategy fit neatly into this model. In 1976, ITW acquired Devcon, known for wear-resistant coatings and maintenance, repair, and operations solutions—another specialized business in an industrial niche. The playbook was becoming clear: buy companies with strong positions in narrow categories, keep what made them work, and apply ITW’s operating discipline to sharpen margins and focus.

Under Nichols, the compounding was dramatic. Over his thirteen years as CEO, ITW’s revenue increased roughly tenfold. The company also became publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange—giving shareholders liquidity and giving ITW a powerful new tool for growth.

By the end of the 1980s, ITW didn’t just have decentralization. It had decentralization with a system—a set of tools, habits, and expectations that could be taught, repeated, and transplanted into new businesses. ITW treated those tools as proprietary, even trade-secret, because they were becoming more than management theory.

They were becoming an acquisition engine waiting to be fed.

VI. The Acquisition Machine Era (1990-2000)

The 1990s turned ITW from a highly successful industrial company into something closer to an industrial private equity firm. Over the decade, it bought roughly 100 companies—and in the process, it more than doubled revenue and sharply increased profits.

The logic was almost irresistible. ITW believed it had built a transferable operating system. Take 80/20 discipline, pair it with customer-back innovation, wrap it in decentralization, and you could improve the performance of just about any well-positioned industrial business. If that was true, acquisitions weren’t merely a way to get bigger. They were an arbitrage: buy a solid company earning mediocre returns, apply the ITW playbook, and lift the profit engine.

The 1993 acquisition of Miller Electric showed what that could look like in the real world. Miller, based in Appleton, Wisconsin, was a leading U.S. manufacturer of arc welding equipment with a proud engineering heritage—including the world’s first high-frequency-stabilized AC industrial welder and the Millermatic line of semi-automatic MIG welders. After the death of Miller’s heir, ITW acquired the Miller Group for about $250 million in stock.

ITW didn’t swallow Miller into a big corporate structure. It kept Miller as an autonomous business, applied 80/20 thinking, and protected the engineering culture that made the products great in the first place. Over time, welding became one of ITW’s standout segments, eventually producing operating margins above 30%.

As the decade went on, the tempo picked up. By 1995, ITW was growing fast—revenue rising about 20% annually, profits up 40%. That combination is rare in industrials. Many companies can buy growth. Far fewer can buy growth and expand margins at the same time.

Then came 1999 and the crown jewel: Premark International, acquired for roughly $3.4 billion in stock. It was a very different kind of move for ITW—less bolt-on, more “giant leap.” Premark added $2.7 billion in revenue and brought a set of premium commercial food equipment brands including Hobart, Vulcan, Wolf, and Traulsen. Hobart, in particular, came with deep roots going back to 1897, with staple products like commercial dishwashers and meat slicers that lived in restaurant and institutional kitchens around the world.

Even with a deal this large, ITW ran the same playbook. Instead of consolidating Premark into existing divisions, it broke the business into smaller, focused units—each aligned to a category, a customer set, and a clear P&L. The brands mattered precisely because they served distinct niches with specialized needs, and ITW didn’t want that specificity blurred by corporate standardization.

By 2000, ITW had grown into a sprawling confederation of nearly 600 divisions. The small size was intentional. Average division revenue hovered around $25 million—big enough to matter, small enough to keep leaders close to customers and to keep the entrepreneurial pressure on.

ITW’s approach to integration was also unusually hands-off. One executive later noted that doing 50 or 60 acquisitions a year had an obvious side effect: the company didn’t really “integrate” in the traditional sense at all. Instead, ITW brought a toolbox—80/20, customer-back innovation frameworks, and incentives aligned to those behaviors—then left most operational decisions with the people running the business.

That created real advantages. It was fast. It preserved culture. And it made ITW an attractive buyer, because sellers didn’t have to assume their company would be carved up or their teams cut to the bone. Customer relationships and institutional knowledge—the stuff that tends to get destroyed in heavy-handed integrations—often stayed intact.

But there was a tradeoff. ITW knowingly left classic synergies on the table. Most acquirers chase cost savings by combining purchasing, manufacturing footprints, and back-office functions. ITW largely rejected that logic. It accepted some inefficiency as the price of decentralization.

By the end of the decade, the question wasn’t whether ITW could acquire and improve businesses—it had proved that. The real question was whether the machine could run forever. How many deals could management oversee without losing control of the system? And what happened if the supply of attractive acquisition targets dried up?

VII. Portfolio Optimization and Enterprise Strategy (2000-2012)

When the dot-com bubble burst and the economy rolled into recession, ITW finally hit something it hadn’t faced in a long time: a real, sustained slowdown. After years of expansion—helped along by an almost nonstop acquisition cadence—the early 2000s brought softer demand, declining revenue, and an uncomfortable question hanging over the whole model.

Had the deal machine gone as far as it could go?

ITW’s response was classic ITW. No dramatic reinvention. No desperation pivot. It leaned on the operating discipline it already believed in and worked its way through the cycle. By 2003, the company crossed two symbolic thresholds—$10 billion in revenue and $1 billion in profit—proof that the core engine still worked even when the environment didn’t cooperate.

But inside the company, the conversation was changing. The more ITW looked at what it owned, the clearer it became that not everything fit.

Premark had delivered exactly what ITW wanted—great industrial brands and durable positions in commercial food equipment. It also delivered some baggage. West Bend appliances, Precor fitness equipment, and Florida Tile were far more consumer-oriented than ITW’s industrial sweet spot, and they demanded different muscles: different channels, different product cycles, different brand dynamics. Over the following years, ITW sold these non-core businesses and recycled the capital into areas where its 80/20 and customer-back approach could actually create an advantage.

At the same time, ITW kept expanding globally, pushing deeper into Brazil, Russia, India, and China—markets where industrial activity was growing faster than in the U.S. and Western Europe. Decentralization helped here. Local leaders could adapt products, pricing, and go-to-market tactics to local realities without waiting for corporate permission. ITW didn’t need a single monolithic global plan; it needed lots of good local ones.

Still, the biggest shift of the era arrived at the end of the period. In 2012—ITW’s 100th anniversary—the company named E. Scott Santi CEO. Santi was an ITW lifer. He knew the culture from the inside, which also meant he could see the downside of what decades of success had produced: a company that had become sprawling, complex, and, in places, less sharp than the ITW playbook demanded.

Santi’s answer was the Enterprise Strategy, launched in late 2012. It was a meaningful pivot in emphasis. Instead of relying primarily on acquisitions to drive growth, ITW would simplify, focus, and improve what it already owned—with the stated goal of delivering solid growth with best-in-class margins and returns.

The strategy rested on three moves.

First was Portfolio Management. ITW would actively prune the tree—selling businesses that were commoditized, lower quality, or simply didn’t have durable differentiation. Over time, ITW divested about $5 billion of revenue, roughly a quarter of the company, including the 2015 sale of Signode Industrial Group for $3.2 billion.

Second was Business Structure Simplification. The extreme version of decentralization had created close to 800 autonomous units—entrepreneurial, yes, but also fragmented. ITW consolidated those units into about 84 divisions. The idea wasn’t to kill autonomy; it was to keep decision-making close to the market while giving businesses enough scale to run more efficiently than a $25 million mini-company could.

Third was Strategic Sourcing. For decades, ITW had intentionally left classic corporate “synergies” on the table. Under the Enterprise Strategy, it finally pulled one of the biggest levers available: purchasing power. Without lowering quality standards, ITW began coordinating sourcing in a way the old model simply didn’t. The effort generated more than $900 million in cumulative savings.

What made the Enterprise Strategy so important is what it proved. ITW could create enormous value without leaning on acquisitions. By simplifying the portfolio, reducing internal complexity, and applying 80/20 with renewed intensity, the company found margin and return expansion opportunities sitting inside the businesses it already owned. In a way, it was also an acknowledgement: the acquisition boom years had created clutter, and disciplined focus could now unlock it.

For investors, that was the real takeaway. ITW wasn’t just a good dealmaker. It was a compounding system—one that could keep producing strong, predictable outcomes even when the acquisition pipeline slowed.

VIII. Modern ITW: The Next Phase (2012-Present)

When Christopher O'Herlihy became ITW's eighth CEO on January 1, 2024, he took over a company that had already been refit by the Enterprise Strategy. O’Herlihy was a 34-year ITW veteran and had been Vice Chairman, so this wasn’t a “new sheriff in town” moment. It was continuity—E. Scott Santi moved to Non-Executive Chairman—paired with a clear handoff in emphasis. The heavy lifting on simplification was largely done. Now the question was: could ITW lean less on reshaping the portfolio and more on growing what it already owned?

Modern ITW is organized into seven segments that touch almost every corner of the industrial economy. Automotive OEM, about a fifth of revenue, supplies fasteners, components, and fluids to vehicle manufacturers around the world. Food Equipment, at 17%, is home to the Premark-era brands—Hobart, Vulcan, Wolf—making the ovens, dishwashers, and prep equipment that quietly power restaurants and institutional kitchens. Test & Measurement and Electronics, roughly 18%, serves markets like semiconductors, electronics, and aerospace with specialized testing systems and components.

Construction Products, at 12%, sells fastening systems and tools into commercial and residential construction. Welding, at 11%, includes Miller Electric and other brands in industrial welding. Polymers & Fluids, also 11%, covers adhesives, sealants, and fluids used across automotive, industrial, and consumer applications. And Specialty Products, another 11%, includes Hi-Cone beverage packaging alongside a mix of other specialized industrial offerings.

The 2024 results showed what ITW looks like when the model is fully matured. Revenue was $15.9 billion, down modestly year over year as some end markets softened. But profitability moved the other direction: operating margin hit a record 26.8%, rising 170 basis points even as sales dipped. Operating income grew 6% to $4.3 billion. Six of the seven segments expanded margins, and Welding and Specialty Products both topped the 30% mark.

That kind of margin performance in a down revenue year doesn’t happen by accident. ITW credited it to what it calls Enterprise Initiatives—the continued, systematic application of 80/20 and continuous improvement across the portfolio. In 2024, those initiatives contributed 130 basis points of margin improvement, and ITW said they have delivered at least 100 basis points of annual margin expansion for more than a decade.

Customer-Back Innovation, once more philosophy than metric, has also been turned into an explicit growth lever. In 2025, ITW reported that innovation contributed 2.4 percentage points to organic growth, up from 2.0% the year before. The target is 3% or more by 2030, reflecting a deliberate push to invest in R&D while using the decentralized structure to stay embedded with the customers that matter most.

Underneath all of that is a large and growing intellectual property base. ITW’s patent portfolio has climbed to roughly 21,000 granted and pending applications worldwide. It’s a quiet moat: across diverse niches, patents and proprietary trade secrets help protect positions that might otherwise be competed away on price. ITW has said more than half of its revenue is covered by patents or proprietary trade secrets.

Financially, the company behaves like what it is: a mature, cash-generating compounding machine. ITW has raised its dividend for 62 consecutive years, earning “Dividend King” status. It has also been a steady buyer of its own stock, with repurchases running around $1.5 billion a year, contributing about 2% to earnings-per-share growth. Free cash flow conversion has regularly exceeded 100% of net income, funding dividends and buybacks while keeping the balance sheet strong.

The operating model has also aged well in a world of geopolitical friction. ITW’s “produce where we sell” approach means more than 90% of its production serves local markets, limiting exposure to tariffs and trade barriers. When tariff concerns rose in 2025, the company said it offset the impact through pricing and supply chain adjustments without materially affecting margins or guidance.

Looking ahead, ITW’s 2026 guidance called for 2% to 4% revenue growth, including 1% to 3% organic growth, operating margins of 26.5% to 27.5%, and earnings per share of $11.00 to $11.40—about 7% growth at the midpoint. It also expected to return roughly $3 billion to shareholders through dividends and buybacks while continuing to invest behind organic growth opportunities.

IX. The ITW Playbook: Lessons in Decentralization

ITW’s story is useful not because it’s exotic, but because it’s repeatable. It shows that decentralization can work at enormous scale—if you’re willing to pair freedom with real discipline. Not “we trust our people” as a vibe, but a clear operating system that divisions are expected to run.

Start with ownership. ITW division managers aren’t caretakers waiting for headquarters to tell them what to do. They hire, they set pricing, they decide where to invest, and they’re accountable for the results. That autonomy makes responsibility unavoidable—there’s no hiding behind corporate mandates when a decision turns out wrong. It also turns ITW into a magnet for a specific kind of leader: someone who wants to run a business, not manage a slice of one.

But ITW’s decentralization isn’t a free-for-all. Autonomy without a framework just creates noise. So ITW draws the lines clearly: the business model revolves around 80/20 focus, the growth engine is customer-back innovation, and the cultural guardrails are the same values the company has repeated for more than a century—integrity, respect, trust, simplicity, and shared risk. Inside those boundaries, divisions can adapt to their markets without waiting for permission.

Operationally, the sharpest weapon is simplification. Dedicating a production line to only three or four products can sound restrictive, but it’s the opposite. It enables long runs, fewer changeovers, higher quality, and lower costs. The hard part isn’t the manufacturing math. It’s the discipline to say no—to marginal products, to tiny customers, and to the complexity that sneaks in one exception at a time.

ITW also sticks close to where it sells. Making products near the customer reduces supply chain risk and makes the business more responsive. If a division serving Japanese automakers needs to handle a spec change quickly, it can—because the plant and the people are local. That proximity tightens relationships, too. Engineers don’t have to collaborate through late-night calls across time zones; they can work side by side.

The talent model reinforces all of this. ITW tends to hire people who want autonomy and accountability, and then it actually gives them both. It also promotes heavily from within, which is how you end up with CEOs like Christopher O’Herlihy—someone who spent 34 years inside the system before taking the top job. That kind of continuity matters in a company where the culture is the strategy.

When ITW does acquisitions, it runs a consistent playbook. It brings in the toolbox—80/20 analysis, customer-back innovation methods, incentives that reward focus—and it resists the urge to “integrate” through disruption. The acquired company isn’t dismembered or swallowed into a centralized machine. That approach makes ITW a more attractive buyer: sellers can believe their teams and customer relationships will survive the transaction.

All of it ladders back to the values. They aren’t slogans on a lobby wall; they show up as operating principles. Simplicity is the most visible one. ITW treats complexity like an enemy that’s always trying to sneak back in—through extra SKUs, one-off customer requests, sprawling org charts—and the company fights it continuously.

Add it up and you get something that doesn’t feel like a typical conglomerate. ITW operates like a collection of focused businesses that can move fast, stay close to customers, and innovate without bureaucratic drag—while still benefiting from a shared model that keeps everyone pointed in the same direction.

X. Analysis and Investment Case

ITW sits in a very specific lane in industrials. It isn’t the biggest conglomerate—peers like Honeywell and 3M are larger. It isn’t the fastest grower, either; plenty of smaller industrial companies can outpace it in any given year. What makes ITW stand out is something rarer: the ability to run the same playbook, over and over, through good markets and bad, and keep producing dependable results.

If you run ITW through Porter’s Five Forces, you can see why the model holds up.

The threat of new entrants is real but contained. Many of ITW’s businesses aren’t “hard” because of a single breakthrough; they’re hard because they require specialized manufacturing, credibility with demanding customers, and deep integration into how those customers design and produce their own products. Patents and proprietary know-how add another layer of protection, even if the strength of those barriers varies by segment.

Buyer power depends on the end market. Automotive OEMs are huge, sophisticated negotiators—and they can push on price. But they also care intensely about engineering support, reliability, and consistency at scale. In food equipment, the customer set ranges from major chains to independent operators, but the value proposition is the same: when a kitchen goes down, revenue goes down. Uptime matters, and that shifts the conversation away from lowest price.

Supplier power is limited by ITW’s size and its willingness, especially post-Enterprise Strategy, to flex purchasing leverage. Strategic sourcing has delivered more than $900 million in cumulative savings, and the company manages supplier relationships to avoid getting boxed in by any single dependency.

Substitutes exist in pockets—paper carriers could replace plastic rings, for example—but in many ITW categories the product is embedded in the customer’s process. And “embedded” is one of those words that sounds soft until you live it: switching often means re-engineering, re-qualifying, re-training, and taking risk on something that wasn’t broken. The switching costs are often higher than they look from the outside.

Competitive rivalry is the force you feel most. ITW doesn’t compete against a single giant across the portfolio; it fights focused specialists in each niche, plus diversified industrial peers that overlap in specific segments. Danaher is the closest philosophical comparison: another company with a famous operating system and a long history of buying businesses and improving them. Depending on the category, ITW also runs into companies like Dover, Parker Hannifin, and Rockwell Automation.

Look at ITW through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens and the picture gets even clearer.

The heart of ITW’s advantage is Process Power. The 80/20 discipline isn’t a clever insight; it’s an operating system that’s been taught, reinforced, and applied for decades. Competitors can see the outcome, and they can try to copy the tools—but the hard part is the cultural commitment to simplification and focus, especially when it requires saying no to complexity that feels like “growth.”

Scale Economies show up more within divisions than at headquarters, because decentralization limits the classic corporate synergy story. But scale still matters where it counts—welding is a good example, where distribution reach and sustained product development can be difficult for smaller competitors to match.

Switching Costs are another quiet strength. They show up when ITW components are engineered into a platform—fasteners specified for a vehicle program, commercial kitchen equipment that fits workflow and service routines, test-and-measurement systems configured into a manufacturing process. Once ITW is designed in, it tends to stay in unless something breaks.

From there, the investment debate becomes a question of what can go wrong, and what can keep going right.

The bear case starts with cyclicality. Automotive, about a fifth of revenue, moves with production cycles and faces ongoing disruption as electric vehicles change designs and supply chains. Construction cycles with interest rates and broader economic activity. Currency translation can move reported results around, even if ITW’s “produce where we sell” approach reduces transactional exposure. And skeptics will argue that many of ITW’s end markets are mature—good businesses, but not naturally high-growth ones.

The bull case is basically the company’s track record, plus the claim that there’s still runway left. ITW has repeatedly expanded margins even when revenue was flat or down—2024 is the clean example, with a meaningful jump in operating margin despite negative organic growth. The innovation engine is more measurable now, and management is explicitly pushing it harder. The balance sheet is strong, incentives are aligned, and capital allocation has been consistently shareholder-friendly.

If you’re watching ITW as an investor, two signals matter most.

First is operating margin progression. ITW’s Enterprise Initiatives have produced at least 100 basis points of annual margin expansion for more than a decade. Whether that continues tells you if the system is still finding simplification and productivity gains inside the portfolio—or if the easy wins are gone.

Second is organic growth. ITW has deliberately shifted emphasis away from acquisitions and toward growing what it already owns. That’s the real test of the “Next Phase.” Customer-Back Innovation contributed 2.4 percentage points to organic growth in 2025, up from 2.0% the year before. If ITW can push that to its 3%+ goal by 2030, it will be strong evidence that the model isn’t just good at improving businesses—it’s still capable of creating new growth inside them.

XI. Future Outlook and Closing Thoughts

ITW’s 2026 guidance pointed to more of what the company has been built to deliver: modest revenue growth, incremental margin expansion from its enterprise initiatives, and meaningful cash returned to shareholders. There’s no promised breakout year, no dramatic reinvention. That’s the bet. ITW is designed to compound, not sprint.

Electric vehicles sit right at the intersection of risk and opportunity. Automotive OEM is still a major segment, and ITW supplies many of the traditional automakers navigating an uneven transition. Volumes and platforms will shift, and that can create pressure in the short term. But EVs still need fasteners, fluids, and engineered components—and in many cases, the specs get tighter, not looser. ITW has been investing in EV-relevant applications, even if it hasn’t broken out the revenue specifically tied to them.

Sustainability has also moved from side conversation to core expectation, especially in businesses like Hi-Cone. For decades, plastic ring carriers drew criticism over waste and wildlife impact. ITW’s response has been to redesign the product and the materials system around it, including RingCycles carriers made with more than 50% post-consumer recycled content, and a commitment to move its entire portfolio toward recycled or recyclable materials. The company has also pointed to life cycle analysis showing its carriers can have materially lower greenhouse gas emissions, energy use, water use, and landfill waste than paperboard alternatives.

Then there’s the harder-to-measure issue that might matter most: succession and cultural preservation. ITW’s operating model is distinctive, and distinctive models only work as long as leadership keeps reinforcing them. Christopher O’Herlihy’s rise from within the organization fits the ITW pattern—leaders shaped by the system before they’re asked to steward it. The company’s ability to carry its culture across eight CEOs and more than a century may be its most durable competitive advantage.

Zoom out, and the broader lesson is almost unfashionable: manufacturing, done exceptionally well and managed with discipline, can still produce extraordinary outcomes. ITW doesn’t rely on network effects or software scalability. It competes in physical markets where rivals can, in theory, copy products and fight on price. The differentiation comes from doing the basics systematically better—simplifying, focusing, staying close to the customer, and repeating that cycle year after year.

It’s worth going back to the beginning. Byron Smith’s 1912 newspaper advertisement—looking for shop-floor talent and practical inventions—sparked something no one could have forecast. A $22,500 start became a company worth tens of billions, employing tens of thousands, operating in 51 countries. Conservative finances, engineering excellence, and a counterintuitive commitment to decentralization weren’t just principles; they were compounding decisions, reinforced over generations.

And ITW will probably always be that kind of company: everywhere, but rarely noticed. Most people don’t realize they run into ITW constantly—in the welded seams of their cars, the fasteners inside appliances, the carriers at the grocery store, and the ovens and dishwashers in restaurant kitchens. That invisibility isn’t a weakness. It’s the strategy. ITW wins by being essential rather than famous, indispensable rather than glamorous.

For investors, the appeal is straightforward: a proven system, strong margins, and a long track record of disciplined capital allocation. The real debate isn’t whether ITW can execute—it has for more than a century. The debate is whether steady execution in mature end markets can produce returns that justify the price you pay for that reliability. If your time horizon is long and you value predictability, ITW offers something increasingly rare: a business you can understand that tends to do what it says it will do.

XII. Recent News

In early February 2026, ITW reported fourth quarter and full-year 2025 results that beat expectations—and, more importantly, kept the company’s core story intact: modest growth, steady execution, and margins that keep creeping higher. Full-year revenue came in at $16 billion, with operating income of $4.3 billion. Operating margin expanded slightly to 26.3%, and ITW again pointed to its enterprise initiatives as the engine behind the improvement, contributing 125 basis points. Welding was the standout, posting margins above 33%—the highest profitability of any segment.

That consistency also shows up at the top. The CEO transition from E. Scott Santi to Christopher O’Herlihy, completed in early 2024, has looked less like a regime change and more like a relay handoff. O’Herlihy’s 34-year career at ITW meant he didn’t need to learn the operating model—he helped build it. And the results since the transition have continued along the same Enterprise Strategy trajectory: simplify, focus, and expand margins.

Capital allocation stayed on script, too. ITW repurchased $1.5 billion of shares in 2025 and raised its dividend by 7%, extending its streak of consecutive annual dividend increases to 62 years.

ITW also spent much of 2025 proving out a claim it’s been making for years: that its supply chain is structurally built to handle geopolitical friction. With more than 90% of operations aligned to its “produce where we sell” approach, tariff exposure was limited. And where tariffs did hit, ITW said pricing actions more than offset the costs—contributing positively to both earnings per share and margins.

Looking ahead, management guided for 2026 earnings per share of $11.00 to $11.40, about 7% growth at the midpoint. It also called for revenue growth of 2% to 4%, including organic growth of 1% to 3%. Operating margin guidance of 26.5% to 27.5% implied further expansion, with enterprise initiatives once again expected to do much of the work.

XIII. Links and Resources

Company Filings and Investor Relations - ITW annual reports and 10-K filings (SEC EDGAR) - ITW quarterly earnings releases and 10-Q filings - ITW Investor Day presentations (2023, 2024) - ITW Investor Relations website: investor.itw.com

Company Resources - ITW corporate website: www.itw.com - ITW Business Model overview: www.itw.com/about-itw/itw-business-model - ITW Enterprise Strategy overview: www.itw.com/about-itw/enterprise-strategy - ITW company history: www.itw.com/about-itw/history

Historical Resources - “Illinois Tool Works Inc. History” — FundingUniverse - “The Shakeproof Success of ITW at 100 Years” — Global Fastener News (2012) - Encyclopedia.com company profile - Company-histories.com historical narrative

Industry and Competitive Analysis - “Illinois Tool Works: Extreme Decentralization” — Harvard D3 Platform - “The 80/20 Principle: Implementing ITW’s Iconic Best Practice” — Stranberg Associates - Comparison with the Danaher Business System — In Practise - Industrial conglomerate sector analysis from major investment banks

Related Company Histories - Northern Trust company history (Byron Smith’s bank) - Miller Electric Manufacturing history - Hobart Corporation history - Spiroid Gearing company history and Oliver Saari biographical materials

Books on Related Topics - “The 80/20 Principle” by Richard Koch (background on Pareto analysis) - Books on decentralized management and industrial strategy - Business histories of Chicago’s industrial growth

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music