JPMorgan Chase: The Empire That Runs Wall Street

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: one institution moving roughly $10 trillion in payments every day, employing more than 300,000 people across 60 countries, and valued at over $800 billion—more than twice its nearest rival. That’s JPMorgan Chase: America’s largest bank, and the most valuable company east of the Mississippi.

But the truly wild part is where it started. Not in a marble lobby or a trading pit—inside a plan for a water company, a political feud that ended in the most famous duel in American history, and a quietly inserted clause that slipped past New York lawmakers in 1799. From that loophole, to the gilded age dominance of J. Pierpont Morgan, to the Rockefeller era at Chase, and finally to Jamie Dimon’s two-decade run as the most powerful banker on the planet, JPMorgan’s story isn’t just corporate history. It’s the story of American capitalism learning—over and over—how to survive.

So how did a water company from 1799 become the fortress of American finance? That’s what we’re here to answer.

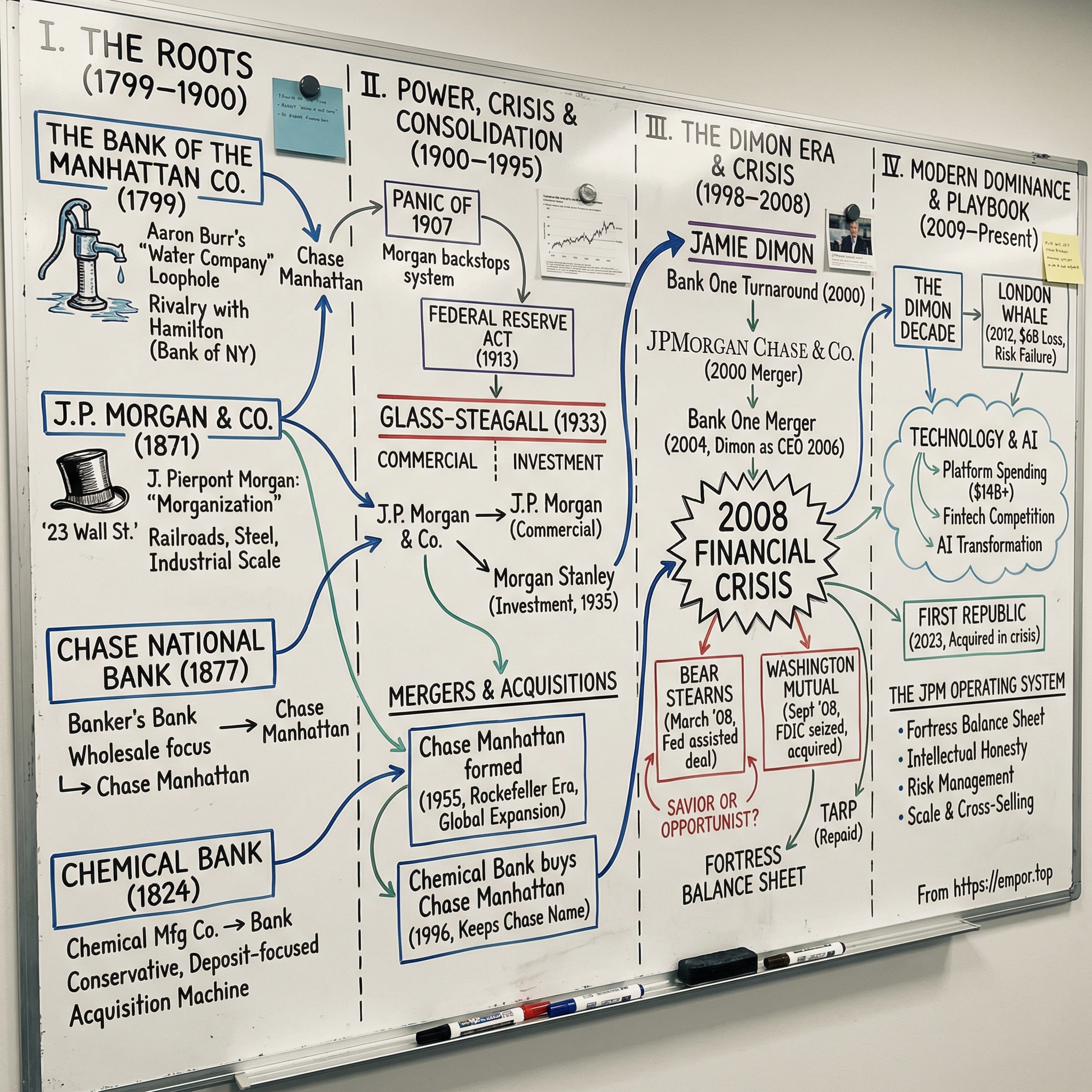

In this episode, we’ll trace the intertwined roots of four banking dynasties—The Bank of The Manhattan Company, Chase National, Chemical Bank, and J.P. Morgan & Co.—that, across two centuries of deals, crises, and reinventions, fused into today’s financial superpower. We’ll go back to the Panic of 1907, when one man effectively backstopped the entire U.S. financial system. We’ll walk through 2008, when JPMorgan emerged as both savior and opportunist—buying Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual in crisis-era transactions that reshaped the industry. And we’ll unpack the Dimon era: the operating philosophy, the culture of risk control, and the “fortress balance sheet” mindset that turned a sprawling bank into the competitor everyone else measures themselves against.

And if you’re listening as an investor, a founder, a policymaker, or just someone trying to understand who really runs the financial world—this isn’t trivia. The path JPMorgan took to become JPMorgan is the playbook. It’s what makes the franchise so hard to copy—and it’s also where the cracks, if they ever appear, are most likely to form.

II. The Roots: From Water Company to Banking Dynasty (1799–1900)

In the spring of 1799, New York City was scared. Yellow fever had been tearing through the city for years, killing thousands, and officials were desperate for an explanation—and a fix. The leading theory was simple: the wells were tainted. Manhattan needed a centralized water system.

Into that public-health emergency stepped two of the most consequential figures in the young republic with a proposal that, on its face, had nothing to do with banking.

Alexander Hamilton—first Treasury Secretary, the architect of America’s early financial system—wanted functional institutions that could stabilize a fragile economy. Aaron Burr, the shrewd New York politician who would soon become Thomas Jefferson’s vice president, saw a different kind of opportunity. These two were already rivals, and within five years they’d meet on a dueling ground. But in 1799 they came to Albany with a charter request for The Manhattan Company: a water utility for New York City.

Here’s the catch. Burr had tucked a clause into the charter so artfully it slipped through without sparking alarm. The company, it said, could use any “surplus capital” for whatever “moneyed transactions or operations” it deemed appropriate. A water company, allowed to do banking.

Hamilton, focused on the water crisis, appears to have missed what that language really enabled. The Legislature approved the charter. And almost immediately, The Manhattan Company opened an “Office of Discount and Deposit.” It was a bank, hiding in plain sight behind a civic project.

The irony was almost too perfect. Hamilton had helped found the Bank of New York back in 1784, and it had become the premier financial institution in the city. Burr’s “water company” had just created a direct competitor with one well-placed sentence.

Their personal feud only deepened. On July 11, 1804, they faced off in Weehawken, New Jersey. Burr shot Hamilton, who died the next day. The duel became legend—but the business move that preceded it was its own kind of victory: Burr had outmaneuvered Hamilton before either man ever raised a pistol.

The Bank of The Manhattan Company, born in controversy, endured. The water business didn’t. It was sold off by 1808. The banking operation kept going for more than two centuries, eventually becoming the “Manhattan” in Chase Manhattan—one of the core ingredients of today’s JPMorgan Chase. And in one of history’s quiet little winks, Chase Manhattan’s headquarters would later sit just blocks from where Hamilton built the Bank of New York, in the financial district Hamilton helped bring into existence.

The House of Morgan Rises

While The Manhattan Company laid roots in New York, another financial dynasty was taking shape an ocean away.

Junius Spencer Morgan, a successful merchant from Hartford, moved to London in 1854 to join the firm of George Peabody. When Peabody retired in 1864, Junius renamed the business J.S. Morgan & Co. and became the preeminent American banker in Europe—positioned exactly where the capital was, in the era when America needed oceans of it.

His son, John Pierpont Morgan—J.P. Morgan to history—was built for scale. Born in 1837 into wealth, he was educated in Boston and across Europe, spoke multiple languages, and developed a taste for art that would later shape one of the great collections in the world. He also carried a physical presence that people remembered: a disfiguring skin condition left his nose permanently misshapen, and his expression—part scowl, part judgment—became its own kind of intimidation.

In 1871, at age 34, Pierpont partnered with Anthony Drexel of Philadelphia to form Drexel, Morgan & Co. at 23 Wall Street. Initially, it was the American outpost for his father’s London house—a bridge for European money into American railroads, steel mills, and industrial expansion.

But Morgan didn’t want to be a middleman. He wanted to be the organizer.

The American economy of the late 1800s was a chaotic sprawl: competing railroads laying redundant track, operators undercutting each other into bankruptcy, booms followed by panics. Morgan saw that chaos as a business model. He developed “Morganization”—take control of a failing railroad, restructure its finances, impose discipline and professional management, and turn a wreck into a stable enterprise. By the 1890s, Morgan effectively controlled about one-sixth of America’s railroad mileage.

When Drexel died in 1893, Pierpont renamed the firm J.P. Morgan & Co. and took full command. 23 Wall Street—later simply “The Corner”—became the nerve center of American finance. Morgan didn’t need to talk much. His reputation did the talking for him. When he moved, markets listened.

Chase and Chemical: The Other Pillars

While Morgan built a power base through industrial reorganization and high finance, two other institutions were quietly laying the groundwork for modern commercial banking.

In 1877, John Thompson—a veteran banker and publisher of financial guides—founded Chase National Bank. He named it after Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary and the man who helped create the national banking system during the Civil War. Thompson had no personal tie to Chase. He simply admired what the name represented. The bank opened with $300,000 in capital—small by New York standards—but Thompson’s credibility drew good relationships and steady growth.

Chase National became a “banker’s bank”: more wholesale than retail, serving other banks instead of everyday depositors. By the early 1900s, it was a preferred correspondent bank across the country, handling transactions and extending credit for smaller institutions nationwide. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was strategically powerful—plumbing that the financial system depended on.

Chemical Bank’s origin story was even stranger, and even older. The New York Chemical Manufacturing Company formed in 1823 to make chemicals, medicines, and dyes. One year later, in 1824, it secured a banking charter—another example of early America’s improvisational approach to regulation. Chemical Bank of New York was born, and by 1844 the chemical business had been sold off. What remained was the bank.

Chemical’s culture was the opposite of Morgan’s. It was conservative and deposit-focused, obsessed with survival rather than spectacle. Through the 19th century’s recurring panics, Chemical built reserves and protected capital. It made it through every panic from 1837 to 1907 without needing outside help. That instinct—never risk the franchise—would echo through the bank’s descendants for generations.

By 1900, the cast was set. Morgan’s house dominated securities and corporate finance. Chase National was emerging as the country’s banker’s bank. Chemical was the cautious, capital-protecting deposit gatherer. And The Manhattan Company was entrenched as a New York retail bank with an origin story that still reads like a political thriller.

None of their leaders were aiming for a single mega-bank. But each was building a capability—and a culture—that, decades later, would click together into the institution we now call JPMorgan Chase.

III. The House of Morgan Era: Power & Influence (1900–1935)

October 1907. The Knickerbocker Trust Company—one of New York’s biggest trust banks—was suddenly on the verge of collapse. Depositors poured into the streets and formed lines that wrapped around city blocks, demanding cash. The New York Stock Exchange started to seize up because brokers couldn’t find enough money to settle trades. Banks across the country failed. And Washington couldn’t do much about it.

Because there was no Fed. No FDIC. No formal lender of last resort.

Except, functionally, there was one.

J.P. Morgan was 70 years old, wealthy beyond measure, and supposedly stepping back from day-to-day work. None of that mattered. When the panic hit, he called the country’s top financiers to his private library at 219 Madison Avenue. In a mahogany room packed with rare books and old-master paintings, Morgan set up what amounted to an emergency command center for the U.S. economy.

For weeks, the rescue effort ran on Morgan’s schedule and Morgan’s judgment. He pored over balance sheets. He decided which institutions were worth saving and which ones were going to be allowed to break. He put up his own money. He leaned on rivals to contribute. He coordinated with the Treasury to move government deposits into New York banks to stabilize cash levels.

And when the Stock Exchange nearly shut down for lack of settlement cash, Morgan did what only Morgan could do. He raised $25 million in about fifteen minutes—by summoning bank presidents to his office and telling them, in no uncertain terms, what their “contributions” would be.

The Panic of 1907 was the high-water mark of Morgan’s power. It was also the moment the country realized what that power implied.

Because here was the uncomfortable truth: the American financial system was being held together by the health, patience, and temperament of a single elderly man. Confidence didn’t return because the underlying problems had magically disappeared. It returned because Morgan made clear he would support solvent institutions—and the market believed him.

Once depositors believed the panic was contained, the runs slowed. Banks reopened. The Exchange kept trading. Morgan had, in effect, backstopped the country.

That outcome didn’t inspire gratitude in Washington. It inspired fear.

Senator Nelson Aldrich launched the investigations that would feed directly into the Federal Reserve Act. Then came the Pujo Committee hearings in 1912 and 1913, which dragged Morgan and other Wall Street leaders before Congress to explain what critics called the “money trust”—a small circle of New York bankers with outsized control over credit and corporate America.

Morgan didn’t apologize. He pushed back. When asked what made him comfortable extending credit to someone, he gave an answer that sounded almost old-fashioned, even then: “The first thing is character.” When pressed on whether he could manipulate markets, he bristled: “I could not do it if I tried. I have never done anything to create a panic.”

But the tide had turned. The same dominance that had steadied the system in 1907 now convinced lawmakers that no private citizen should ever hold that kind of leverage again.

Morgan died in Rome on March 31, 1913—only months before the Federal Reserve Act became law. Control passed to his son, John Pierpont Morgan Jr., known as Jack. Jack lacked his father’s intimidating presence and volcanic certainty, but he was a capable steward of the franchise.

World War I put that to the test. J.P. Morgan & Co. became the sole purchasing agent in the United States for Britain and France, arranging enormous volumes of war supplies and financing. The firm’s role was so central to the Allied effort that, in 1915, German agents tried to assassinate Jack at his Long Island estate.

Then came the 1920s: a decade of growth, speculation, and swagger. Wall Street boomed. Morgan underwrote securities, extended credit, and remained embedded across the commanding heights of American industry. The firm’s influence expanded with the market.

And that influence—along with the structure of banking itself—was about to be rewritten.

Glass-Steagall: The Great Separation

After the stock market crashed in October 1929, the public mood turned from awe to anger. Congressional investigations surfaced ugly realities: commercial banks dabbling in securities speculation, conflicts of interest between deposit-taking and underwriting, and a financial system that looked, to many, like it had been built to enrich insiders while ordinary Americans absorbed the losses.

In 1933, Congress passed the Banking Act—better known as Glass-Steagall. Its core demand was simple: choose a side. Either you were a commercial bank that took deposits and made loans, or you were an investment bank that underwrote securities and advised on deals. You couldn’t be both.

For J.P. Morgan & Co., it was an existential fork in the road. The firm had long combined the two: deposits from corporations and wealthy families on one side, securities underwriting and advisory work on the other. Jack Morgan opted to remain a commercial bank, prioritizing the deposit relationships that had anchored the firm since his father’s era.

So the investment bankers left.

On September 16, 1935, a group of Morgan partners—led by Harold Stanley and Henry Morgan, Jack’s son—walked out to form Morgan Stanley & Co., a separate investment bank. The split was cordial, but the implications were enormous. For the first time in generations, “Morgan” meant two institutions. J.P. Morgan & Co. stayed at 23 Wall Street as a commercial bank. Morgan Stanley opened nearby at 2 Wall Street—steps away, but legally and structurally a different creature.

Glass-Steagall’s wall would stand for more than sixty years, and it reshaped American finance. Commercial banks became tightly regulated, deposit-driven institutions. Investment banks became the market-facing risk takers.

And the separation matters for understanding JPMorgan Chase today. Modern JPM is the product of those two lineages being forced apart, developing their own cultures for decades, and eventually being stitched back together. The conservative, relationship-first instincts that came out of the commercial bank world—think Chase and Chemical—had to coexist with the deal-and-markets DNA of the Morgan tradition.

That integration challenge would become one of the defining management problems of the modern era. And, later, one of Jamie Dimon’s signature accomplishments.

IV. Building the Modern Conglomerate (1935–1995)

By the middle of the 20th century, American banking started to change shape. What had been a patchwork of regional institutions slowly turned into a contest to build national champions. The ingredients of today’s JPMorgan Chase were still separate, but each was evolving in ways that made an eventual combination not just possible, but almost inevitable.

In 1955, The Bank of the Manhattan Company—Aaron Burr’s old “water company,” now a century and a half into its second life—merged with Chase National Bank to form Chase Manhattan Bank. On paper, it was a clean fit: Chase brought the wholesale, institution-to-institution business; Manhattan brought a retail footprint and a deeply embedded New York presence.

But the real story of Chase Manhattan was the man who rose inside it.

David Rockefeller was 40 when the merger happened, and he wasn’t just another fast-rising banker. He was the youngest son of John D. Rockefeller Jr., grandson of the Standard Oil founder, and—through Rockefeller family trusts—the bank’s most important shareholder. He had the résumé too: Harvard, the London School of Economics, and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago, before joining Chase National in 1946. In global finance, his name didn’t merely open doors. It pre-opened them.

Rockefeller became president in 1961 and chairman in 1969. Under him, Chase Manhattan tried to become something bigger than a New York bank with national ambitions. It wanted to be a global institution. Rockefeller traveled relentlessly—more than two million miles over his career—building relationships with heads of state, finance ministers, and business leaders. Chase planted flags across the world, opening offices in more than 70 countries.

The reach was real. The results were messier.

Rockefeller drew criticism for chasing prestige and political relationships more than shareholder returns. Chase’s performance lagged rivals during much of his tenure, and the far-flung empire generated attention without reliably generating earnings. By the time he retired in 1981, Chase Manhattan was huge—but uneven, and increasingly fragile. It had become a collection of businesses that never quite clicked into one machine.

Chemical: The Quiet Accumulator

While Chase expanded outward, Chemical Bank ran the opposite playbook. This was the institution whose defining instinct, dating back to the 1800s, was survival. But Chemical paired that caution with something else: disciplined, repeatable acquisition.

In 1954, Chemical bought Corn Exchange Bank, picking up 98 branches and a meaningful base of consumer deposits. That deal became the template. Chemical didn’t need splashy narratives or celebrity executives. It bought solid franchises, integrated them tightly, and squeezed out costs over time.

In 1986, Chemical’s acquisition of Texas Commerce Bank pushed it into the Southwest and the energy economy. In 1991, it merged with Manufacturers Hanover, a onetime top-tier American bank that had been weakened by Latin American debt exposure and real estate losses. Chemical did what it always did: take control, replace systems, impose cost discipline, and keep moving.

The Manufacturers Hanover deal made the strategy impossible to ignore. “Manny Hanny” was vulnerable; Chemical was methodical. Chemical kept what was strong, cut what was redundant, and emerged larger—without losing its core identity. The playbook worked, and it worked more than once.

The Real Estate Collapse and Chase’s Vulnerability

Then the late-1980s commercial real estate boom rolled over into a brutal bust. Construction loans, development projects, and property bets that had looked safe in the upcycle suddenly turned toxic. Losses spread across the industry, but Chase Manhattan had a particular problem: heavy exposure to New York real estate, right where the downturn hit hard.

By the early 1990s, Chase’s capital position deteriorated sharply. The bank cut its dividend, laid off thousands, and watched its stock price crater. For an institution that had spent decades as a symbol of American banking stature, it was a public unraveling. Rumors swirled: would Chase need government help, or would someone stronger simply take it?

The answer was Chemical.

In 1996, Chemical announced it would acquire Chase Manhattan in a deal valued at about $10 billion. It created the largest bank in America at the time. And then came the most telling move of all: Chemical kept the Chase name.

This was the subtle genius of bank mergers. The buyer doesn’t always win the branding war. Chemical’s leadership understood that “Chase” carried weight with corporate treasurers, international clients, and the broader market in a way “Chemical” never would. So the merged institution became Chase Manhattan—even though Chemical executives ran it, and Chemical’s systems and operating discipline became its backbone.

For the next few years, the new Chase Manhattan digested what it had bought, finished integrating the pieces, and readied itself for the next wave of consolidation that was already building.

J.P. Morgan’s Parallel Evolution

While Chase and Chemical were building scale through commercial banking and mergers, J.P. Morgan & Co. was evolving along a different axis. After Glass-Steagall, it remained on the commercial-bank side of the divide, but it kept pushing toward the edge of what a commercial bank could be—reinventing and adapting as rules and markets changed.

The brand still meant something. Morgan bankers carried themselves like an elite guild. The culture was “white-shoe,” proud of its heritage, and shaped by the old partnership ethos—even after the firm went public in 1942. The internal expectations were strict: professional conduct, restraint, and a sense that the institution’s reputation mattered as much as any single quarter’s results.

By the 1990s, Morgan had real strengths in derivatives, foreign exchange, and emerging markets, plus a research franchise and client relationships that competitors respected. But it didn’t have the sheer scale to go toe-to-toe with the biggest players in underwriting and trading. As the industry consolidated, that became a problem.

Then the wall finally started to come down.

In 2000, J.P. Morgan & Co. merged with Chase Manhattan Company to form JPMorgan Chase & Co. The logic was straightforward: Chase brought the balance sheet and the commercial banking engine; Morgan brought investment banking capabilities and a name that still carried a certain electricity on Wall Street. Chase CEO William Harrison became chairman and CEO of the combined company.

But the integration was anything but smooth. Morgan people often saw Chase as big and blunt—less refined, less “Wall Street.” Chase executives saw Morgan as elitist and insular. The new firm had enormous resources, but it didn’t yet have a single identity or operating system. It needed a leader who could cut through legacy loyalties, unify the cultures, and set a coherent direction.

That leader wasn’t in New York.

He was in Chicago, running Bank One—and he was about to step onto the biggest stage in American finance.

V. The Dimon Era Begins: Bank One & The Modern Chase (1998–2006)

On November 27, 1998, Sandy Weill fired his protégé—the man most of Wall Street assumed would someday inherit the empire. Jamie Dimon, 42 years old and president of Citigroup, was out.

To outsiders, it looked impossible. Weill and Dimon had spent fifteen years stapled together, turning acquisition after acquisition into something that barely existed before them: a modern financial supermarket. Now Dimon was unemployed, publicly dismissed from the institution he’d helped assemble, and suddenly unsure what came next.

The partnership had been one of the defining alliances in late-20th-century finance. Dimon, the son of a Greek-American stockbroker, went from Tufts to Harvard Business School and joined Weill at American Express in 1982. When Weill was pushed out in 1985, Dimon didn’t hedge. He followed.

They resurfaced by buying Commercial Credit, a Baltimore-based consumer finance company, and rebuilding from there. Dimon became CFO at 30—young, relentless, and numbers-obsessed. Over the next decade, the two of them stitched together Travelers, Smith Barney, Salomon Brothers, and ultimately Citibank, creating Citigroup. Dimon rose to president and heir apparent.

And then it ended.

Why the rupture happened was never fully clarified. Some blamed internal politics—especially a clash between Dimon and Weill’s daughter. Others pointed to a simpler cause: Weill didn’t actually want to hand over power. Whatever the truth, the outcome was clean and brutal. Dimon was gone.

He spent the next eighteen months in limbo. He traveled. He read. He worked out relentlessly. He took meetings, listened to offers, and waited. Then, in March 2000, the right kind of problem showed up: Bank One.

Bank One was the fifth-largest bank in America, based in Chicago—and it was unraveling. A 1990s roll-up of mergers, it had all the classic symptoms of a badly digested consolidation: incompatible tech, inconsistent risk controls, internal confusion about what the bank even wanted to be. The stock was down sharply, morale was awful, and customers were leaving.

To plenty of observers, it was a strange match. Why would a high-profile executive, fresh off a public firing, choose a turnaround in the Midwest?

Because Dimon didn’t see a broken bank. He saw raw material.

Under the mess, Bank One had real assets: a strong credit card business, a major retail footprint across the Midwest and Texas, and millions of customers. What it lacked was discipline—one set of systems, one set of standards, and someone willing to make the calls.

Dimon came in and did what he always did. He rebuilt the senior team, pulling in people he trusted. He went after the technology chaos, consolidating platforms and killing redundant systems that had survived because no one wanted the fight. He demanded clean numbers and real accountability, not “close enough.” Bankers quickly learned that if you brought Dimon a report, it had better be right.

The turnaround worked. Earnings steadied, then climbed. The stock recovered. Customer satisfaction improved. The place felt different. In just a few years, Bank One went from a troubled also-ran to one of the best-performing large banks in the country.

The Merger That Made the Empire

In January 2004, JPMorgan Chase announced it would acquire Bank One in a deal valued at $58 billion. The combined company would become the second-largest bank in America, behind only Citigroup. But the real prize wasn’t a balance sheet.

It was Jamie Dimon.

The merger brought him in as president and chief operating officer—and as the designated successor to CEO William Harrison. The terms reflected just how much leverage Dimon had earned. The succession wasn’t implied; it was spelled out. He’d report to Harrison at first, but he would take the top job within two years—an unusually explicit promise in a business that normally avoids promises.

For the next two years, Dimon treated the role like a quiet takeover. He learned the machine, mapped the weak points, and built relationships with the executives who would matter once he was in charge. Bank One hadn’t had a major investment bank; JPMorgan Chase did. Dimon studied it, formed views on its risk appetite, and started shaping what the combined firm would prioritize.

When Harrison stepped down on December 31, 2005, Dimon slid into the CEO seat. In December 2006, he added the chairman title, consolidating control.

At 50—eight years after the Citigroup humiliation—Jamie Dimon was running one of the most powerful financial institutions on Earth.

Building the Fortress Balance Sheet

Dimon’s core idea was simple, almost unfashionable in the mid-2000s: capital and liquidity weren’t dead weight. They were weapons.

A bank with excess capital and deep liquidity could outlast a panic that wiped out thinner competitors. It could buy distressed assets when everyone else was forced to sell. It could keep lending when the system seized up—and win customers for life in the process. In Dimon’s mind, the best time to gain market share was when other banks were too scared, or too broken, to compete.

That worldview put him in direct conflict with the era’s incentives. The mid-2000s credit boom rewarded leverage. Analysts praised “optimized” balance sheets. Investors wanted buybacks, special dividends, and higher returns—now. Conservatism looked like underperformance.

Dimon didn’t play along. He pushed capital up. He kept more liquidity than regulators demanded. He avoided the most aggressive subprime mortgage products that were printing money for competitors. And when people questioned the caution, he answered the way he usually did: bluntly.

When the tide goes out, you’ll see who’s been swimming naked.

The tide was about to go out.

VI. The 2008 Financial Crisis: Savior or Opportunist?

On the evening of March 13, 2008, Jamie Dimon got the call that would come to define his era. Timothy Geithner, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, was on the line with a simple message: Bear Stearns was out of time.

Bear—the fifth-largest investment bank on Wall Street—was facing a classic modern bank run. Not lines of depositors, but counterparties backing away, and repo lenders refusing to roll the overnight funding that kept the firm alive. If nothing changed before markets opened on Monday, Bear could fail. And in a system wired together by leverage and confidence, a Bear failure risked turning panic into cascade.

Geithner’s question wasn’t subtle: would JPMorgan Chase buy it?

Dimon didn’t say yes. He said “maybe,” with conditions. JPMorgan would need immediate access to Bear’s books. It would need speed. And it would need government support—because whatever Bear was hiding, JPMorgan wasn’t going to swallow it raw.

What followed became one of those “where were you that weekend?” moments in Wall Street history. JPMorgan teams poured into Bear’s headquarters to triage a firm in free fall: trading positions, mortgage exposure, derivatives, counterparty obligations. The deeper they dug, the uglier it got. Bear held huge amounts of subprime and mortgage-backed securities that were already collapsing in value. Its derivatives book was sprawling and hard to unwind cleanly. Every hour made the problem larger.

By Sunday, the conclusion was blunt: Bear was worth essentially nothing—maybe less than nothing, once you counted what could blow up after the ink dried. But letting Bear go to zero, in public, on a Monday morning? That was the kind of event that can break a system.

So the Federal Reserve did something that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier. It offered extraordinary support: up to $30 billion in lending to JPMorgan to make the acquisition possible, secured by some of Bear’s worst assets. In practical terms, the Fed was taking most of the downside.

The initial price reflected the diagnosis: $2 per share—down from $170 the year before. For Bear employees and longtime shareholders, it was annihilation. A storied Wall Street name was being sold for less than the rough value of its real estate.

Even in a crisis, though, $2 was hard to land politically and psychologically. Bear’s board threatened to walk away. Shareholders revolted. JPMorgan raised the bid to $10 per share, and the revised structure reduced the Fed’s exposure by expanding JPMorgan’s guarantees. On May 30, 2008, shareholders approved the sale. Bear Stearns was gone—absorbed into JPMorgan Chase.

Washington Mutual: Becoming America's Largest Bank

Six months later, as the crisis intensified, Dimon pulled off an even cleaner deal.

Washington Mutual—the country’s largest savings and loan—collapsed under mortgage losses. On September 25, 2008, the same week Lehman failed and the government rescued AIG, regulators seized WaMu and sold its banking operations to JPMorgan Chase for $1.9 billion.

From a pure “what did you get for what you paid?” standpoint, WaMu was the better trade. JPMorgan picked up about 2,200 branches, $188 billion in deposits, and a major mortgage servicing operation—without taking on the holding company’s liabilities. The FDIC had already wiped out WaMu’s shareholders and bondholders, leaving the pieces JPMorgan actually wanted. The price worked out to roughly a penny per dollar of deposits acquired.

Together, Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual didn’t just make JPMorgan bigger. They changed its shape. Bear brought prime brokerage and a deeper markets footprint. WaMu delivered a massive West Coast retail network and millions of new customer relationships. Coming out the other side, JPMorgan Chase became America’s largest bank by deposits and assets—a position it would not give back.

The Price of Rescue

But crisis bargains have a second invoice. It just arrives later.

Bear had originated and securitized enormous volumes of mortgages with representations and warranties that didn’t vanish in an acquisition. Washington Mutual’s mortgage machine had been even more aggressive. Inherited liabilities—tied to what those institutions did before JPMorgan owned them—followed JPMorgan for years.

The legal bill was enormous. Between 2010 and 2020, JPMorgan Chase paid more than $19 billion in mortgage-related settlements, with about 70% tied to Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual. The bank settled with the Department of Justice, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, state attorneys general, and private plaintiffs. In 2013, one settlement alone totaled $13 billion—then the second-largest corporate settlement in U.S. history.

Over time, Dimon’s tone about the Bear deal changed. He repeatedly argued that JPMorgan had been encouraged to step in, then punished for doing it. In 2015, he put it plainly: “No, we would not do something like Bear Stearns again. In fact I don't think our Board would let me take the call.”

He wasn’t wrong about the sequence. Federal officials did want JPMorgan to stabilize failing institutions, and they did praise Dimon for stepping up. Then, for years, they extracted penalties tied to pre-acquisition behavior. The experience left its mark on Dimon’s posture with regulators: cooperative, but never naïve.

TARP and the Fortress Survives

Unlike almost every other major bank, JPMorgan Chase didn’t need government money to stay standing. It did take $25 billion in TARP funds in October 2008—but Dimon has said it was because Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson wanted all the major banks to participate, so weaker ones wouldn’t be singled out. JPMorgan repaid the funds, with interest, in June 2009 as soon as regulators allowed it.

This is where the “fortress balance sheet” stopped being a philosophy and became a competitive weapon. While Citigroup needed a $45 billion bailout plus government guarantees on $300 billion of assets, and while Bank of America required $45 billion plus guarantees on $118 billion, JPMorgan kept lending, kept operating, and kept shopping. The capital cushion analysts had complained about before the crisis turned into freedom of action during it.

The aftermath reshaped the league tables—and the psychology of the entire industry. Citigroup was effectively on government life support. Bank of America was struggling to absorb Countrywide. Morgan Stanley had to convert into a bank holding company and take capital from Mitsubishi. Goldman faced similar pressures. JPMorgan, alone among the peers, came out of 2008 not merely intact—but larger, more central, and more feared than before.

VII. The Dimon Decade: Consolidating Power (2009–2020)

After 2008, American banking was supposed to enter a long penalty box.

Congress passed Dodd-Frank. Capital and liquidity rules tightened. Proprietary trading was reined in. Regulators got sharper elbows. The public mood stayed ugly. And investors, burned by the crisis, demanded safer banks—while still hoping for pre-crisis returns.

Most big banks responded by shrinking, simplifying, and trying not to make headlines.

JPMorgan Chase did something else: it kept playing offense.

Dimon’s post-crisis formula had three parts. First, keep a hard grip on costs and operating discipline. Second, spend heavily on technology even when everyone else treated it as optional. Third, use JPMorgan’s scale, balance sheet, and breadth to take market share across the entire franchise—consumer banking, cards, payments, corporate lending, investment banking, and markets.

The fortress balance sheet supplied the staying power. Bear and WaMu supplied the size. Dimon supplied the tempo.

And the results were hard to argue with. Over the decade after the crisis, JPMorgan steadily expanded its capital base, generated best-in-class returns, and compounded shareholder value at a pace that didn’t look normal for an institution this large. In a period when “big bank” was practically a punchline, JPMorgan turned itself into the benchmark.

The London Whale: A Fortress’s Only Crack

There was one moment, though, when the story nearly snapped—and the irony was brutal. It didn’t come from the flashy investment bank. It came from inside the part of the house that was supposed to be safest.

In early 2012, traders in JPMorgan’s Chief Investment Office in London built massive positions in credit derivatives. The positions were described as hedges—insurance against credit stress elsewhere on the bank’s balance sheet. But they kept growing. They got complicated. And they got big enough that the market noticed.

A trader at the center of it earned the nickname “the London Whale,” because the trades were so large they seemed to move the ocean around them. Hedge funds smelled blood and started leaning against JPMorgan, betting the bank would be forced to unwind at worse and worse prices.

At first, Dimon waved it off. On an April earnings call, he called the concerns “a complete tempest in a teapot.”

Within weeks, that line aged into a meme.

The bank disclosed that losses had hit $2 billion. Then they kept climbing. By the time JPMorgan fully unwound the positions, the loss topped $6 billion.

For Dimon, it was a personal gut punch. His whole brand—inside the building and out—was control: know the exposures, know the numbers, don’t kid yourself. The London Whale was a failure of oversight, risk reporting, and internal challenge. A blind spot inside the machine he’d built.

He went to Congress, took responsibility, and endured a public grilling that made clear how quickly “best-run bank” could turn into “too-big-to-manage.” He later called it “the stupidest situation I’ve ever been involved in.”

The bank paid more than $920 million in fines. Executives left. Controls were tightened. But the larger truth was this: JPMorgan could absorb the hit. The fortress could take a $6 billion punch and keep standing.

The damage was real, but it was reputational more than existential. The London Whale became a warning—about complexity, about complacency, about how even a discipline-obsessed culture can miss something sitting in plain sight.

Technology as Competitive Moat

If the Whale was the decade’s embarrassment, technology was the decade’s strategic masterstroke.

Dimon didn’t treat tech like overhead. He treated it like the battlefield. While many banks tried to meet the moment with mobile apps and incremental upgrades, JPMorgan aimed to build an advantage that would be hard to catch: better systems, better data, better digital customer experiences, better security, and faster product cycles.

By the late 2010s, JPMorgan was spending roughly $11–12 billion a year on technology. It employed around 50,000 technologists—more akin to a major tech company than a traditional bank. Dimon talked less about beating the bank down the street and more about competing with fintechs and platform companies that wanted to unbundle finance.

The spending wasn’t just about shiny features. It went everywhere the modern bank lives:

Retail: smoother digital banking, more engagement, lower cost-to-serve.

Operations: automation that reduced errors and sped up processing.

Risk: better analytics and stronger controls, designed to spot problems earlier.

Infrastructure: scalability and resilience to keep the plumbing running.

And then there were the long-dated bets—blockchain, AI, even quantum computing—areas that might take years to matter, but could reshape finance if they did. The point wasn’t that every bet would hit. It was that JPMorgan could afford a portfolio of bets, and smaller players couldn’t.

By 2020, the gap was visible. JPMorgan’s digital experience ranked at the top of the industry. Its trading and transaction platforms held their own against specialists. And the bank looked unusually prepared for a world where banking would be less branch-and-paper and more software-and-data.

Compensation: The Price of Leadership

As JPMorgan pulled away from the pack, another storyline became annual tradition: Dimon’s pay.

His compensation kept rising—$34.5 million in 2022, $36 million in 2023, $39 million in 2024—making him, year after year, the highest-paid CEO among major U.S. bank chiefs.

Critics saw it as excessive, especially in an industry still living under the shadow of 2008. Supporters pointed to the scoreboard: performance, stability, and a franchise that had become more dominant, not less, under his watch. In their view, Dimon wasn’t just a CEO. He was a strategic asset—hard to replace, and priced accordingly.

The structure was meant to signal alignment. Much of it was stock-based and vested over time. Dimon also held more than $1 billion in JPMorgan shares personally. Whatever you think of the headline number, it’s clear that this wasn’t a leader optimizing for the next bonus cycle.

It was a leader optimizing for staying in control of the most powerful bank in America—and making it even more powerful.

VIII. Modern Dominance & Strategic Positioning (2020–Present)

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Markets didn’t just wobble; they broke. Stocks sold off, credit spreads blew out, and suddenly the modern economy looked like it might be headed for a long, dark pause. Once again, the question wasn’t whether there would be stress. It was which institutions were built to absorb it—and which would crack.

JPMorgan’s response was the fortress balance sheet in a live-fire drill. While other banks focused inward, JPMorgan kept credit flowing to clients under pressure, leaned hard into the Paycheck Protection Program, and kept paying a dividend that others cut or suspended. During the program’s first phase, the bank processed more than 400,000 PPP loans, putting roughly $35 billion into the hands of small businesses trying to survive the shutdown.

COVID also turned Dimon’s long-running technology thesis into an overnight reality. Years of digital adoption got compressed into months. Customers who preferred branches and paper statements were pushed onto mobile apps and online portals—whether they liked it or not. JPMorgan’s heavy investment over the prior decade meant its systems didn’t buckle under the surge. In the pandemic’s early scramble, “it works” became a competitive advantage.

The other workplace experiment was remote work—and here, Dimon was famously unconvinced. JPMorgan proved it could operate with huge portions of the workforce distributed, but Dimon kept pushing for a quicker, fuller return than many peers. He argued that mentorship, collaboration, and the apprenticeship nature of banking eroded when people stopped bumping into each other. The stance drew criticism, but it fit his worldview: this may be a software-driven business, but it’s still a relationship business.

First Republic: History Repeating

In March 2023, the next stress test arrived—this time in regional banks. After Silicon Valley Bank failed, confidence turned brittle. Deposits moved fast. First Republic, an elite franchise with wealthy customers in major coastal markets, got caught in a classic modern-day run: not depositors lining up at branches, but money leaving with a few taps.

Regulators wanted to stop contagion. And as they had before, they called the one institution everyone believed had the balance sheet, the operational capacity, and the political permission to absorb the shock.

On May 1, 2023, JPMorgan acquired First Republic’s deposits and most of its assets from FDIC receivership. JPMorgan paid about $10.6 billion to the FDIC and took on First Republic’s deposits and loans. The pattern felt familiar: valuable customer relationships, acquired at crisis pricing—another reminder that when the system shakes, JPMorgan tends to get bigger.

Dimon framed the deal as both a stabilizing act and a good outcome for shareholders. Critics saw something darker: JPMorgan’s “too big to fail” status acting like a gravity well. The larger it got, the more it became the default rescuer; the more it rescued, the larger it got. It’s the same argument Americans have been having since 1907—just updated from Morgan’s library to the FDIC’s resolution playbook.

The AI Transformation

In the 2020s, JPMorgan’s technology push intensified, and AI moved from “interesting” to central. Annual technology spending rose above $14 billion, with roughly half aimed at new initiatives rather than simply keeping the lights on. AI wasn’t a single project. It spread everywhere.

In consumer banking, it sharpened fraud detection, tuned customer communications, and improved credit decisions. Machine learning models processed enormous numbers of variables quickly, helping the bank make better approval and loss predictions. Chatbots took routine questions, letting human staff focus on problems where judgment mattered.

In investment banking and markets, AI became an accelerant: faster document review, quicker diligence, better extraction of relevant signals from earnings calls, filings, and news. Traders used AI-generated indicators as one more input. Researchers used large language models to move faster from raw information to written analysis.

JPMorgan recruited AI talent aggressively, built internal teams that published research, and contributed to open-source work. Dimon wrote about AI in shareholder letters with a kind of enthusiasm you don’t usually associate with bank CEOs. He acknowledged the risks—bias, displacement, new systemic vulnerabilities—but his direction was clear: the bank was going to lean in, because AI could reshape finance the way the internet did.

Scale and Scope

By 2025, JPMorgan’s scale had become almost hard to picture. It served about 84 million U.S. consumers and 7 million small businesses. It processed roughly $10 trillion in payments a day. It had more than $4 trillion in assets and employed over 300,000 people worldwide.

That kind of scale compounds advantages. You can spread fixed technology costs across an enormous customer base. You can absorb compliance expenses more easily. You can justify larger R&D bets. And you can cross-sell in a way smaller banks simply can’t: mortgages and credit cards to consumers, treasury services to businesses, investment banking to corporations—all inside one integrated machine.

But scale cuts both ways. When you get this big, organic growth stops changing the story quickly. Regulatory limits make acquisitions harder. Political scrutiny intensifies with every additional inch of market share. JPMorgan was still built to play offense—but it was now playing on a field where the end zones were closer, and the referees were watching every move.

IX. Playbook: The JPMorgan Chase Operating System

By the time JPMorgan hit its modern stride, the “why” behind the outperformance wasn’t mysterious. The bank had an operating system—shaped over decades, sharpened by near-misses, and stress-tested in real crises—that kept producing the same outcome: JPMorgan got stronger when everyone else got weaker.

If you want to understand the moat, you don’t start with a product. You start with the playbook.

The Fortress Balance Sheet: Philosophy and Implementation

At JPMorgan, capital isn’t treated like dead weight. It’s treated like optionality.

Dimon’s core belief was simple: a bank with extra capital and liquidity can do things other banks can’t do when the world gets ugly. That’s why JPMorgan ran with capital levels above the regulatory floor—not because it had to, but because it wanted the freedom to act.

In calm markets, that choice can look boring. A fortress balance sheet can mean slightly lower returns than competitors who squeeze every last drop out of leverage. Investors and analysts will always have a suggestion for what to do with “excess” capital: return it, gear it up, optimize it.

But when conditions flip, the math flips with them. Highly leveraged competitors get forced into survival mode: sell assets, cut credit, take punitive funding, lose clients, lose talent. JPMorgan, by design, gets to be the buyer. It can keep lending. It can take share. It can pick up distressed assets at prices that would have been unthinkable a year earlier. That’s the trade: accept a little less heat in the boom so you don’t die in the bust—and so you can go shopping when everyone else is cornered.

The hard part isn’t the mechanics. It’s the patience. Dimon kept saying no when the market kept asking for more.

Dimon’s Management Principles

Dimon’s style has always been blunt, but the management philosophy underneath it is consistent—and it shows up everywhere from his shareholder letters to how meetings run inside the building.

Intellectual honesty is the table stakes. “Don’t try to use numbers to prove what you think. Try to use numbers to understand what you are doing.” The point isn’t the quote. The point is what it demands: no spin, no “close enough,” no hiding the ball. Bad news is not a career-ender at JPMorgan. Surprise bad news is. The culture rewards people who surface problems early, with the facts intact, before they spread.

Build a real leadership team and keep it intact. JPMorgan’s top bench stayed unusually stable for a company of its size. Dimon picked leaders he trusted, gave them room to run, and expected them to own results. That stability mattered. It meant institutional memory. It meant faster execution. It meant fewer internal knife fights for turf.

Humility and grit, together. Dimon has never tried to pretend the bank is perfect. When it makes mistakes, he’ll usually acknowledge them—sometimes painfully publicly—then push for an autopsy and a fix. The London Whale followed that pattern: own it, explain it, repair the controls, move on. The expectation inside JPMorgan is the same. No excuses, no deflection. Diagnose reality, then do the work.

Risk Management Post-2008

After 2008—and then again after the London Whale—JPMorgan treated risk like a system to be engineered, not a box to be checked.

The bank poured investment into seeing exposures across the whole franchise, not just within individual desks or business lines. Stress testing became a habit. Not only the Dodd-Frank exercises regulators demanded, but internal scenario work designed to answer a more uncomfortable question: what happens if something we consider “unthinkable” becomes Tuesday?

Risk appetite was set at the enterprise level, with explicit limits around concentrations—by counterparty, sector, and geography. Within those guardrails, business heads still had autonomy. That balance was intentional. Too much central control creates bureaucracy and blind spots. Too little creates chaos. JPMorgan tried to build a structure where speed lived inside constraints.

The London Whale also drove a specific lesson home: models can be dangerous when people trust them too much. Sophistication can create false confidence—especially if assumptions drift or markets behave in ways the model was never built to handle. JPMorgan didn’t abandon quantitative tools. It just re-emphasized that human judgment had to remain in the loop. The models inform. They don’t absolve.

Cross-Selling and Integration

JPMorgan’s other structural advantage is that it’s not one business. It’s all of them—under one roof.

Pure investment banks can’t offer a consumer deposit base. Pure retail banks can’t do global markets at scale. Pure asset managers don’t run payment rails. JPMorgan does. And that breadth isn’t just a collection of revenue lines—it’s a machine for compounding relationships.

A corporate client might start with treasury services, then tap JPMorgan for credit, then hand over an M&A mandate. A wealthy household might bank with Chase, move assets into J.P. Morgan’s wealth platform, then use other parts of the firm for lending or liquidity. A small business might begin with merchant acquiring and payments, then grow into loans and cash management. The products differ, but the leverage point is the same: once JPMorgan has the relationship, it has a lot of ways to deepen it.

That kind of integration doesn’t happen automatically in a bank this big. It has to be forced into existence. Business lines naturally want to become fiefdoms. So incentives had to reward referrals, not just local P&Ls. Technology had to connect customer experiences across products. And management had to keep pushing against the gravitational pull of silos.

JPMorgan never eliminated those tensions completely—no large institution does. But it got further than most. And in banking, “further than most” is often the whole game.

X. Analysis & Investment Case

JPMorgan Chase is a rare kind of investment story: the leading financial institution on the planet, valued like it knows it, and built on advantages that look durable—until you remember how quickly finance can change when rules shift, technology jumps, or leadership turns over. To underwrite JPMorgan, you have to hold two ideas at once: this franchise is extraordinarily hard to replicate, and it’s exposed to risks that show up precisely because it’s so big and so central.

Competitive Moat Analysis

Scale economies. JPMorgan’s size turns fixed costs into an advantage. Spending heavily on technology is easy to criticize in a spreadsheet and impossible to ignore in practice—because when you can spread those investments across a $4 trillion balance sheet, you can build systems and capabilities that smaller banks simply can’t afford. The same goes for compliance: in an industry where regulation keeps getting heavier, scale turns what feels like a crushing expense for a regional bank into something closer to a tax the giant can absorb.

Regulatory positioning. JPMorgan’s “systemically important” status cuts both ways, and that’s exactly the point. Yes, it brings extra oversight and higher requirements. But it also raises the walls around the castle. Smaller banks can’t grow into JPMorgan’s position without inviting the same scrutiny, and non-bank entrants face barriers that protect the incumbents. There’s also the uncomfortable reality that “too big to fail” reduces perceived counterparty risk and can lower funding stress in moments when markets start asking who’s safe.

Network effects. Banking isn’t a pure network-effect business like social media, but the effects exist where the plumbing matters. Payments infrastructure becomes more valuable as more participants run through it. Capital markets businesses benefit from liquidity, and liquidity attracts liquidity. The brand compounds too: in finance, reputation travels faster than marketing.

Switching costs. Most banking relationships are sticky because switching is painful. Moving a corporate treasury setup isn’t like changing a SaaS tool. Changing primary consumer banking relationships takes effort. Replacing an investment bank on a complex mandate creates risk—real risk. JPMorgan’s integrated model makes those switching costs even higher, because clients aren’t just leaving a product; they’re untangling a bundle.

Porter’s Five Forces Assessment

Threat of new entrants: LOW. Regulation, capital requirements, and the sheer cost of building modern banking tech stacks keep most would-be challengers in the shallow end. Fintechs have won important niches, but they haven’t broken the core franchise.

Bargaining power of suppliers: LOW. Capital, talent, and technology are available from competitive markets, and JPMorgan’s scale gives it leverage. It can pay for what it needs and still keep the economics attractive.

Bargaining power of customers: MODERATE. The biggest corporate clients can negotiate hard. Retail customers generally can’t. JPMorgan’s breadth complicates the calculus, because alternatives often solve one need, not the full set.

Threat of substitutes: MODERATE. Private credit and non-bank lenders pull activity away from traditional banking in specific areas. Tech platforms compete for pieces of the customer relationship. But core deposit-taking and the payments rails remain harder to substitute than people think—especially at scale.

Competitive rivalry: MODERATE. Competition is fierce in markets and investment banking, and consumer banking is always a fight. But the industry tends to converge on rational pricing over time, and the biggest institutions still find ways to earn strong returns.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies. Clearly present—and one of the main reasons the franchise keeps widening its gap.

Network Effects. Not overwhelming, but real in payments and liquid markets.

Counter-Positioning. Less relevant here. Competitors aren’t missing the playbook; they’re constrained by capital, regulation, and the difficulty of execution.

Switching Costs. Embedded across consumer, corporate, and advisory relationships.

Branding. “Morgan” still signals elite capability in investment banking and wealth. “Chase” signals safety and ubiquity in retail.

Cornered Resource. Jamie Dimon is a cornered resource—rare talent with credibility that matters inside the building, on Wall Street, and in Washington. That advantage eventually flips into a question: what happens after him?

Process Power. This is the quiet one, but it’s real. Risk management, large-scale tech delivery, integration after acquisitions, and running an integrated bank without it tearing itself apart—those are learned capabilities that compound over time and don’t copy-paste well.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re tracking whether JPMorgan’s edge is holding, three metrics do most of the work:

Return on Tangible Common Equity (ROTCE). This is the clearest signal of whether the bank is turning shareholder capital into profit at an elite rate. JPMorgan has delivered mid-to-high teens ROTCE for extended stretches, typically ahead of peers. If that advantage fades for long, it’s a warning light.

Efficiency Ratio. A simple question: how much does it cost to generate a dollar of revenue? JPMorgan has tended to run this better than other major banks, reflecting both scale and operating discipline. If the ratio drifts up without a strategic reason, it usually means complexity is winning.

Credit Costs. Charge-offs and provisions reveal whether risk discipline is actually working. In downturns, credit costs separate the banks with real underwriting standards from the ones that were just riding the cycle.

Bear Case Considerations

Regulatory risk. There’s always political gravity around breaking up large banks or constraining their activities. A full breakup may be unlikely, but incremental rules can still compress returns—especially for the biggest, most visible target.

Size limitations. At this scale, growth is harder. Large acquisitions invite immediate skepticism from regulators. And organic growth, while valuable, doesn’t transform the story quickly. That can push more capital back to shareholders by default, even when management would prefer to reinvest.

Succession uncertainty. Dimon has been the defining variable for two decades. The bench may be deep, but the question isn’t whether JPMorgan can find a competent CEO. It’s whether anyone can replicate Dimon’s combination of operational command, crisis credibility, and political dexterity.

Technological disruption. JPMorgan is a technology leader among banks, but leadership doesn’t make you immune to platform shifts. If money and payments are reshaped by new rails—whether that’s central bank digital currencies, broader crypto adoption, or platform models that rewire distribution—today’s advantages could be pressured in ways that don’t show up in quarter-to-quarter results until they suddenly do.

Bull Case Considerations

Irreplaceable franchise. This is the core bull argument: no one can rebuild, from scratch, the combination of scale, relationships, distribution, and capability JPMorgan has assembled over two centuries. The integrated model creates opportunities that specialists can’t match.

Technology leadership. Spending about $14 billion a year on technology isn’t just defense; it’s a way to widen the gap. Competitors that underinvested now face a catch-up game that may be structurally unwinnable.

Counter-cyclical opportunity. History keeps rhyming: when crises hit, JPMorgan tends to be the buyer, not the forced seller. The fortress balance sheet isn’t just protection—it’s the ability to act when everyone else is cornered.

Shareholder returns. With fewer ways to deploy capital through transformational growth, dividends and buybacks become a larger part of the story. JPMorgan has returned substantial capital over time, and that return engine can be powerful when paired with strong underlying profitability.

XI. Power & Paradox: What JPMorgan Chase Means for America

Jamie Dimon has been called the “least-hated banker” in America—a backhanded compliment that still says a lot. He runs the most powerful bank in the country, earns north of $30 million a year, and leads an institution whose failure would be unthinkable in a true crisis. Yet in public, he comes off as plainspoken: direct, occasionally funny, and willing to say things other CEOs carefully avoid.

That contradiction isn’t just about Dimon. It’s the JPMorgan paradox.

JPMorgan’s success is tightly bound to America’s success. Dimon has said as much, tying the bank’s fortunes to “the health of free and democratic countries.” JPMorgan benefits from the dollar’s reserve-currency status, from U.S. geopolitical power, and from a legal and regulatory system that makes modern finance possible. In return, it supplies the system with what it needs to function: credit for consumers, capital for companies, and liquidity when markets seize up.

It’s symbiotic. It’s also unequal.

Because the systemic-importance question hangs over everything. JPMorgan cannot be allowed to fail. Not because it’s morally special, but because its collapse would be too destructive for any government to tolerate. That reality—whether anyone says it out loud or not—can lower funding costs and deepen customer trust in a way smaller competitors simply can’t match. And that advantage feeds the same concentration that makes the system more fragile in the first place.

It’s a loop that’s hard to break.

Then there’s the moral hazard: if leaders believe the institution will always be rescued, will they take risks they otherwise wouldn’t? Dimon’s “fortress balance sheet” philosophy argues the opposite—run conservatively even when you don’t have to. But the more uncomfortable version of the question is about tomorrow, not today. The backstop that stabilizes one era can tempt a different set of leaders in the next.

The Future of Banking

JPMorgan is also staring down a technological future that could reshape finance more radically than anything since the creation of the Fed. Central bank digital currencies could change the mechanics of deposits. Crypto could reroute payments and custody. Platform companies could own customer relationships and turn banks into utilities sitting behind the interface.

Dimon’s stance often seems contradictory at first glance. He’s dismissed Bitcoin as worthless while investing heavily in blockchain. He’s warned about fintech competitors while copying their features and hiring their talent. But it fits the fortress mindset: don’t bet the company on a single narrative. Prepare for multiple outcomes, keep optionality, and make sure you’re still standing when the world decides which direction it’s going.

That’s where JPMorgan’s technology spending becomes more than a budget line—it becomes strategic positioning. If CBDCs become mainstream, JPMorgan can be the bridge between central bank money and commercial activity. If crypto infrastructure keeps maturing, it can offer custody, trading, and compliance-heavy services at scale. If platform models win distribution, JPMorgan can build its own channels—or pay to buy them. The strategy isn’t prediction. It’s preparedness.

Concentration and Its Consequences

Which brings us to the big, uncomfortable question: what does it mean for a democracy when so much financial power pools inside one institution?

JPMorgan processes around $10 trillion in payments every day. It serves roughly 84 million U.S. consumers and about 7 million small businesses. It sits in the middle of enormous amounts of corporate credit, capital markets activity, and market-making. That kind of concentration can be framed as strength—a national champion that can invest, absorb shocks, and stabilize crises.

And that argument isn’t wrong. Scale does buy capabilities: better technology, deeper security, more compliance muscle, and the ability to keep lending when weaker players have to retreat. In moments like 2020 and 2023, those capabilities can look less like corporate advantage and more like public infrastructure.

But the concerns aren’t wrong either. Concentration creates single points of failure. It amplifies political influence. It raises barriers to entry, sometimes by competing fairly and sometimes simply by being too big to compete with. And it can turn “market discipline” into a slogan, because the market knows the government’s pain tolerance has a limit.

JPMorgan sits at the center of that tension: proof of the efficiencies of concentration, and proof of its dangers.

Dimon won’t run the place forever. He’s 69, still deeply engaged, but succession is no longer an abstract governance topic—it’s one of the most important risk factors in American finance. JPMorgan has credible internal leaders, including Daniel Pinto, Mary Erdoes, and Marianne Lake. But Dimon’s edge has never just been operational competence. It’s accumulated trust—earned with regulators, markets, boards, and counterparties over two decades of high-stakes moments. That’s difficult to hand off.

When that transition comes, it will answer the question that matters most: are JPMorgan’s advantages truly institutional—embedded in the operating system—or were they unusually tied to one extraordinary leader?

For now, JPMorgan Chase remains the defining institution of American finance: built from centuries of compounding history, shaped by crisis, and run with a discipline that has made it stronger in the exact moments the system was supposed to humble it.

XII. Recent News

The fourth quarter of 2024 put an exclamation point on everything JPMorgan had been building toward. The bank posted $14 billion of net income for the quarter, taking full-year earnings to about $58 billion—an all-time high for American banking. A thaw in capital markets helped drive a rebound in investment banking fees after the slow stretch of 2022 and 2023. Trading stayed strong too, even as volatility kept snapping back into the picture.

Looking ahead, management’s 2025 guidance sketched a familiar JPMorgan story: pressure in one place, strength everywhere else. Net interest income was expected to cool as the Federal Reserve moved into a rate-cutting cycle. But the bank expected its fee engines—investment banking, markets, payments, and asset and wealth management—to pick up the slack. And the operating discipline remained a differentiator: JPMorgan continued to run with overhead ratios below major competitors.

Regulation, meanwhile, kept looming as the biggest external variable. The Basel III “endgame” proposals—meant to raise capital requirements for the largest banks—were still being negotiated. JPMorgan pushed back hard on key provisions, with Dimon arguing that overly heavy requirements would reduce lending capacity and weigh on economic growth. With final rules expected in late 2025, the outcome would matter not just for JPMorgan’s capital allocation, but for returns across the entire U.S. banking sector.

Succession moved from background noise to headline risk as Dimon acknowledged that his timeline was now measured in years, not decades. The board raised the profile of several internal leaders, and every organizational move started getting read as a clue. Dimon rejected the idea that an exit was imminent, but investors and analysts watched the bench-building closely—because in a fortress built around process, you still want to know who holds the keys.

And the technology arms race only intensified. JPMorgan announced expanded AI capabilities across customer service, risk management, and trading. The bank emphasized “responsible AI,” publishing governance principles even as it continued to invest aggressively. It was the same posture the firm has taken for years: move fast, but build the controls as you go—because at JPMorgan’s scale, the cost of getting it wrong isn’t a bug. It’s a headline.

XIII. Links & Resources

Annual Shareholder Letters

Jamie Dimon’s annual letters to shareholders are essential reading if you want to understand how JPMorgan thinks. They’re where the bank lays out its strategy in plain English, reflects on what went right and wrong, and frames the macro environment without the usual corporate fog. You can find them on JPMorgan’s investor relations site. The 2023 and 2024 letters are especially useful for getting a clear read on the bank’s current priorities.

Key Regulatory Filings

If you want the unvarnished, comprehensive version of JPMorgan, go to the filings. The 10-K is the yearly deep dive into the business, risks, and financials. The proxy statement (DEF 14A) is where you’ll find the governance mechanics—executive compensation, board composition, and how power is structured at the top. The 10-Qs fill in the quarters between. All of it is accessible through the SEC’s EDGAR database and JPMorgan’s investor relations portal.

Historical Resources

Ron Chernow’s The House of Morgan is still the definitive history of the Morgan dynasty and the culture it stamped onto Wall Street—context that matters if you want to understand why the “Morgan” name still carries weight.

The Last Tycoons by William Cohan is a detailed account of Bear Stearns’ collapse and the weekend that ended with JPMorgan owning it.

David Rockefeller’s Memoirs offers a first-person view into how Chase Manhattan saw itself in the mid-century era, and how Rockefeller’s relationships and worldview shaped the bank’s global push.

Books on Jamie Dimon

Last Man Standing by Duff McDonald follows Dimon’s career through the 2008 crisis and is one of the better windows into his management style and operating instincts.

Academic Papers

For a more analytical lens, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York has published extensive research on systemic risk and the role of large financial institutions—useful framing for understanding why JPMorgan sits where it does in the architecture of the system.

Documentary and Media

Too Big to Fail (HBO, 2011) dramatizes the 2008 crisis, including JPMorgan’s role in the Bear Stearns acquisition.

PBS Frontline’s “The Warning” and “Money, Power and Wall Street” provide a documentary look at the regulatory choices and institutional dynamics that set the stage for the crisis.

Podcast Episodes

Business Breakdowns and Invest Like the Best have both run episodes on banking and financial services that pair well with this story, especially for understanding competitive dynamics and how financial institutions compound—or implode—over time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music