Keysight Technologies: From HP's Garage to the Future of Electronic Measurement

I. Introduction & Episode Setup

November 1, 2014. Ron Nersesian steps up in front of a packed auditorium at Keysight’s Santa Rosa headquarters, on the same campus that once housed HP’s test-and-measurement division. Behind him, a new logo glows on the screen: a stylized key threaded through a sine wave. “Today,” he says, “we become Keysight Technologies.”

The applause is real. So is the unease. This isn’t a scrappy startup unveiling a first product. It’s a newly independent company—born from a spin-off of a spin-off—carrying DNA that traces all the way back to Bill Hewlett’s workbench in 1939. And now it has to prove it can win on its own.

On paper, the whole thing sounds almost comical: three generations of corporate separations, each one framed as “unlocking focus and value.” Yet Keysight didn’t just survive the churn. It emerged as the leader in electronic test and measurement, with a market cap north of $30 billion.

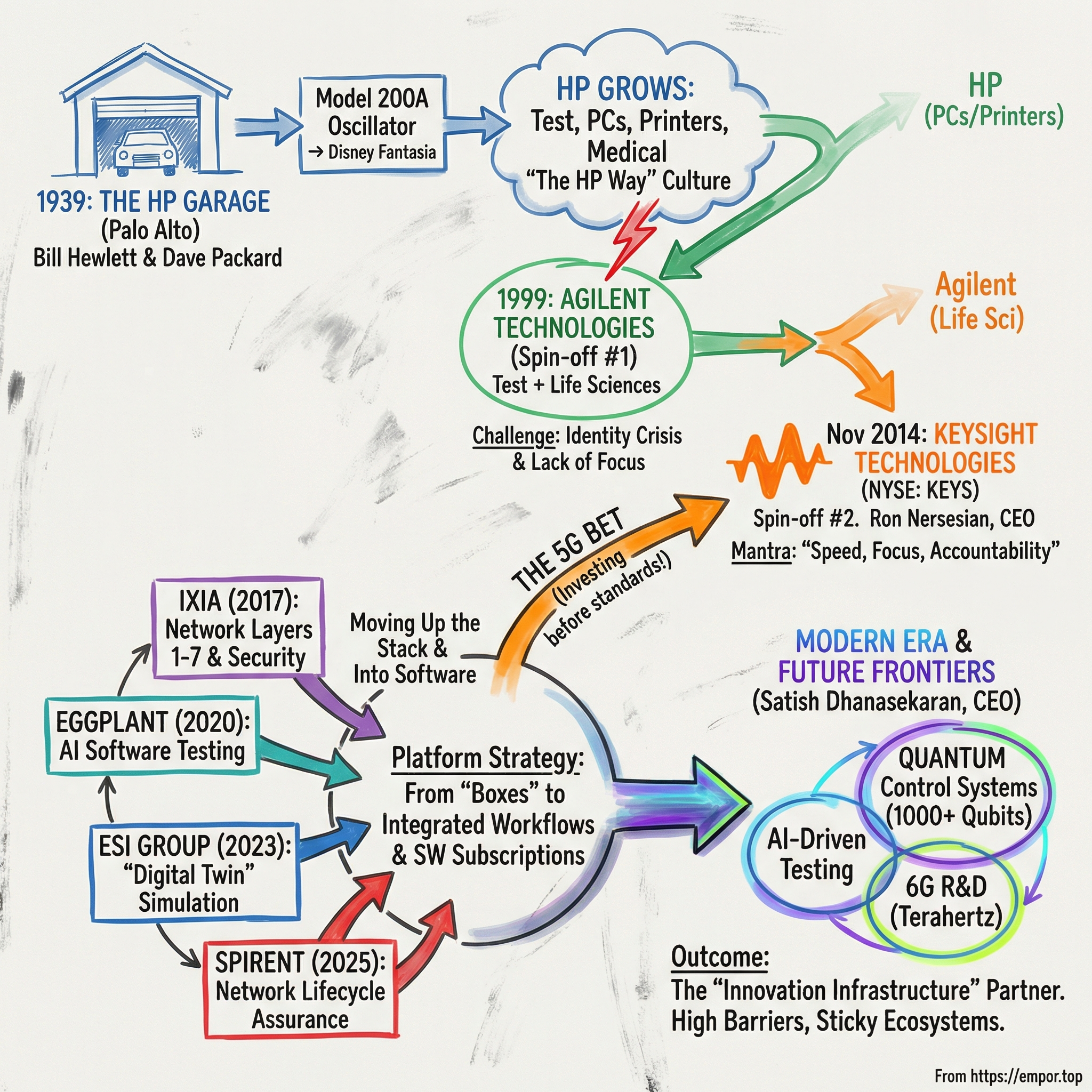

So how did a division buried inside Hewlett-Packard—then shuffled through Agilent—end up setting the pace in 5G test, network visibility, and the bleeding edge of quantum and next-generation research?

The answer turns out to be a playbook on corporate strategy: why focus compounds, why specialization wins, and how breaking up a conglomerate can create something stronger than the original whole. This story starts with an audio oscillator assembled in a Palo Alto garage. It runs straight through Silicon Valley’s rise, multiple reinventions, and into the labs now pushing toward 6G and quantum computing.

And along the way, we’ll see the surprising lesson Keysight embodies: sometimes the fastest way to grow isn’t to add more—it’s to split, sharpen, and become undeniably great at the one thing you do.

II. The HP Origins: Building from the Garage (1939-1999)

The oscillator hummed to life in a cramped garage at 367 Addison Avenue in Palo Alto. Bill Hewlett leaned over the front panel and nudged the frequency dial. Dave Packard watched the needle, scribbling notes as if the whole future depended on it. It was late 1938, and they were dialing in what would become the Model 200A audio oscillator: a machine that could generate clean, precise tones so other engineers could test their equipment.

Even the price was a little bit of theater. They set it at $54.40 on purpose—specific enough to sound like it came from an established catalog, not from two young engineers building their first product.

They didn’t do it alone. Their mentor was Fred Terman, the Stanford professor who would later earn the nickname “the Father of Silicon Valley.” Years earlier, Terman had spotted unusual talent in a small group of undergraduates—Bill Hewlett, Dave Packard, Barney Oliver, and Ed Porter—and he worked hard to keep them close. After Hewlett and Packard graduated and briefly went in different directions, Terman helped pull them back with fellowships. The legend is that he even loaned them part of the $538 they used as starting capital.

On January 1, 1939, Hewlett and Packard made it official. They flipped a coin to decide the company name. Hewlett won—and then insisted it should be “Hewlett-Packard” anyway, because it simply sounded better. It was a tiny act of deference, but it foreshadowed something bigger: a culture that would become known as the HP Way, built around trust, respect, and leaders who stayed close to the work.

Then came the moment every origin story needs: a customer who demanded the impossible.

Walt Disney Studios was deep into making Fantasia, and its revolutionary “Fantasound” system needed a level of audio precision that movie theaters had never attempted—multiple channels, synchronized playback, and stable tones that wouldn’t drift. A Disney engineer saw HP’s oscillator and placed an order, but with modifications. That request led to the 200B Audio Oscillator. Disney bought eight units.

It wasn’t just revenue. It was validation. Hewlett and Packard weren’t merely selling gadgets—they were building instruments so reliable that they let other innovators do things the world hadn’t seen before.

The garage would eventually become a California Historical Landmark, officially designated in 1989 as the “Birthplace of Silicon Valley.” But in 1939 it was just a workshop where two Stanford grads, armed with $538 and a bias toward precision, started turning measurement into a business.

The Measurement Empire Expands

In the beginning, “test and measurement” wasn’t a division. It was Hewlett-Packard.

Through the 1940s and 1950s, HP rolled out oscilloscopes, signal generators, voltmeters, frequency counters—the tools engineers needed to understand what their circuits were actually doing. The pattern was simple: listen closely to customers, find the hard measurement problem, and build the instrument that made it solvable. HP didn’t just ship products. It embedded itself in the workflows and trust of working engineers.

By the 1960s, HP had become the world’s leading electronic test and measurement company. In 1964, it introduced the HP 5060A cesium beam atomic clock, accurate enough to keep time within a second over three thousand years. NASA used HP equipment to monitor Apollo missions. Across the electronics industry, HP instruments became the standard way to prove a design worked—not in theory, but in the real world.

And the culture became as famous as the gear. The HP Way wasn’t a slogan; it was a set of practices. HP established profit-sharing for all employees, and Bill and Dave personally handed out checks well into the 1950s. Leaders were expected to practice “Management by Walking Around,” leaving their offices to spend time on the floor, talking with employees and learning what was actually happening. They pushed “Management by Objectives,” which Dave Packard later said contributed more to HP’s success than anything else.

When the 1970 recession hit, HP chose a different kind of cost-cutting. Instead of layoffs, it implemented the “nine-day fortnight”—a roughly 10% pay reduction paired with a 10% reduction in workload across the board. Shared sacrifice, not panic. It was a stress test for the culture, and the culture held.

While all of this was happening, another thread was forming—one that would eventually reshape the company.

In 1966, HP entered the computer business with the HP 2116A. It was designed to control HP’s own test instruments. This wasn’t HP abandoning measurement; it was measurement pulling the company toward computing. As electronics systems became more complex, testing them demanded more computation. The instrument business and the computer business grew side by side, each pushing the other forward.

The Paradox of Success

By the 1990s, HP was enormous—about a $31 billion company spanning printers, computers, medical equipment, test instruments, and more. The company that started by doing one thing exceptionally well now did hundreds of things pretty well.

That breadth brought a new problem: internal competition for attention and resources. Printers were a cash engine. Computers demanded massive R&D just to keep up with rivals like Dell and Compaq. And the test and measurement business—still innovative, still respected—was no longer the obvious center of gravity. The very thing HP was born doing risked becoming just another line item.

CEO Lew Platt faced the classic conglomerate squeeze. Wall Street wanted focus. Business units wanted investment. Strategy started to feel like compromise.

In March 1999, Platt announced the unthinkable: HP would split in two. The computer and printer businesses would remain Hewlett-Packard. The test and measurement, medical, and chemical analysis divisions would become a new company: Agilent Technologies. HP was going to divide itself in the name of focus—and, in theory, multiply what each half could become.

Inside the company, the announcement sparked an identity crisis. Who would inherit the true HP Way? Where would Bill and Dave’s legacy live? Hewlett, then 86, and Packard, 87, supported the split, but they didn’t crown a successor culture. In reality, both companies would carry the DNA forward—HP through mass-market products, Agilent through precision engineering.

For the test and measurement teams, the emotions were mixed. They were being freed from competing with printers and PCs for capital. But they were also losing the HP name, the one that opened doors everywhere. One veteran engineer captured the feeling: “We went from being the original HP business to being the spin-off. It was like the parents kept the house and we got sent to start over.”

And that was the twist. What felt like an ending was actually the start of a new arc. The business that helped power Fantasia and Apollo was about to step out on its own—beginning a journey that would take two more separations before it finally arrived at its identity as Keysight.

III. The Agilent Era: First Spin-Off and Finding Identity (1999-2014)

November 18, 1999. The opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange had a different kind of charge that morning. Ned Barnholt, Agilent’s first CEO, stood at the podium surrounded by employees dressed in purple—Agilent’s new signature color, picked deliberately to break from HP blue. The IPO priced at $30 a share, raising $2.1 billion and becoming, at the time, the largest Silicon Valley IPO ever. By the end of the day, the stock had jumped to $42.44, valuing Agilent at nearly $20 billion.

Barnholt made the positioning unmistakable. Agilent wasn’t trying to become the next HP. In his view, it was the old HP—especially the measurement side—finally unshackled from the PC and printer battles that were swallowing the parent.

But that first-day pop hid the reality: spinning out is easy on a slide deck. Living through it is something else.

Building Independence

Agilent launched with scale—43,000 employees across 40 countries—and with all the baggage that comes with being carved out of a decades-old institution. It didn’t have fully independent IT systems. It didn’t have clean real estate arrangements. And it didn’t have one shared identity.

Inside HP, these groups had operated like separate worlds: test and measurement engineers in Santa Rosa, medical teams in Boston, chemical analysis groups in Delaware. Now they were supposed to be one company with one set of priorities.

Barnholt, a 30-year HP veteran who had run HP’s test and measurement division, understood the tightrope. Integrate too aggressively and you crush the autonomy that made the divisions great. Move too slowly and you never become a coherent company at all.

Then the market moved faster than anyone’s internal planning.

By March 2000—just four months after the IPO—the dot-com bubble cracked. Many of Agilent’s biggest customers were telecom equipment makers riding the internet buildout. Orders slowed, then stopped. Revenue fell hard, from $10.8 billion in 2000 to $6.0 billion in 2002. The stock, which had touched $70 at its peak, sank below $10.

Agilent tried to fight through the downturn with a big strategic bet: semiconductors. The logic was clean. Chips were getting more complex, which meant testing would only grow in value. If Agilent could become the best chip-testing “arms dealer,” it could ride the next wave of electronics growth.

But semiconductors are cyclical in a way that traditional test and measurement hadn’t been. When the chip industry fell apart in 2001 and 2002, the losses piled up. The company that had once prided itself on stability made painful cuts—18,500 positions by 2003. Barnholt, the careful carrier of HP’s values, had to learn how to run a company in triage mode.

Strategic Divestitures and Pivots

The recovery came through focus—selling what didn’t fit, and investing hard where Agilent believed it could lead.

First came the divestitures. In 2001, Agilent’s healthcare and medical products organization was sold to Philips Medical Systems for roughly $1.7 billion. In August 2005, the semiconductor integrated circuits business went to KKR and Silver Lake Partners for $2.66 billion—an entity that would later become Avago, and eventually part of Broadcom. In 2006, Agilent divested the semiconductor test business as Verigy, which listed on Nasdaq.

At the same time, Agilent leaned into life sciences. It acquired Stratagene in 2007. It bought Varian’s analytical-instruments business for about $1.5 billion in 2010. And in 2012, it acquired Dako, a Danish cancer diagnostics company, for $2.2 billion.

These weren’t random bolt-ons. They reflected a thesis: the next great measurement revolution might not be electrons—it might be biology. The same instincts that had built oscillators and spectrum analyzers could build tools to analyze molecules, genes, and disease.

The Identity Crisis Deepens

By 2010, Agilent had stabilized financially. Strategically, it was still pulled in different directions.

It now contained three very different businesses: electronic measurement (the original HP test business), chemical analysis (spectrometers and chromatographs), and life sciences (genomics and diagnostics). Each wanted different R&D roadmaps, different sales motions, and different capital priorities.

Bill Sullivan, who became CEO in 2005, could see the collision coming. Electronic measurement was staring at a massive investment cycle in next-generation wireless—years before 5G would be mainstream, but already consuming engineering talent and customer mindshare. Life sciences, meanwhile, was pushing deeper into diagnostics and genomics. Trying to fund both at the level required didn’t create balance—it created mediocrity.

So in September 2013, Sullivan announced Agilent’s second split. Agilent would keep life sciences and diagnostics, aiming at what he called “the bio-analytical opportunity of the 21st century.” The electronic measurement business would become a standalone company.

To lead it, Agilent tapped Ron Nersesian, president of the Electronic Measurement Group. Nersesian had started at HP in 1984 as an R&D engineer, built his career through the test and measurement world, left briefly, then returned to Agilent in 2002 and rose to run the business. He knew the tech. He knew the customers. And he understood the emotional reality inside the org: these teams were about to be spun off again.

The story they told themselves mattered. As Nersesian would later put it, they weren’t being discarded. They were being unlocked.

This time, the separation was engineered, not improvised. There were 18 months of planning. New IT systems were built. Supply chains were untangled. And just as importantly, leadership worked to shape a culture that could honor the HP heritage while acting with the urgency of a smaller company in a brutal competitive market.

In January 2014, the new name was revealed: Keysight Technologies. “Key” for unlocking insight. “Sight” for clarity and vision. The logo—a key fused with a sine wave—was a direct thread back to the company’s instrument roots. The tagline, “unlocking measurement insights for 75 years,” tied the moment to 1939.

As November 1, 2014 approached, employees lived in a strange in-between. Same buildings. Same customers. Same products. But the corporate badge was about to change—for the third time in 15 years.

The real question wasn’t whether the test business could survive another spin. It had already proven it could endure.

The question was whether this time, with singular focus, it could finally do what the HP garage had always implied: not just measure the future, but help invent it.

IV. The Keysight Launch: Creating an Independent Company (2014-2015)

The email landed at 12:01 a.m. Pacific on November 1, 2014.

Subject line: “Welcome to Day One.”

Ron Nersesian had written it the night before at his kitchen table, thinking about the time zones. Engineers in Malaysia and China would read it before California even stirred. “Today,” he told them, “we stop being part of something else’s story. Today, we start writing our own.”

By sunrise, he was already in Santa Rosa, greeting early arrivals with coffee and freshly printed Keysight notebooks. The gesture was simple, almost cheesy—and completely intentional. New logo, new name, new tools. Same people. Same mission. Now with nowhere to hide.

Two days later, on November 3, Keysight began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker KEYS. Investors valued the company at roughly $4.74 billion. The market was sending a clear message: test and measurement was respected, but not exactly seen as a rocket ship.

The Competitive Reality

Independence didn’t come with a clean playing field. Keysight was walking into a knife fight.

Tektronix had decades-deep relationships, especially in aerospace and defense. Rohde & Schwarz, the German powerhouse, dominated much of Europe with superb engineering and hard-nosed pricing. National Instruments was winning over engineers who wanted software-defined, programmable approaches to testing. And an increasingly credible set of Chinese competitors, like Rigol, was pushing “good enough” instruments at prices that made procurement teams very happy.

At his first all-hands, Nersesian didn’t pretend otherwise. “We’re not the biggest. We’re not the cheapest. But we’re the most focused.”

He laid out three pillars that would anchor Keysight’s first years: software-centric solutions, deep application expertise, and modular platforms that could evolve as customers’ needs changed.

It all sounded great on a slide. The hard part was doing it while also keeping the lights on.

Keysight started life with about 9,500 employees—and quickly realized it needed more. Not just headcount, but specific talent: software engineers, 5G protocol specialists, and high-frequency RF designers. The recruiting pitch was… complicated. Join a brand-new company that was also a spin-off of a spin-off, or go work at Google, Apple, or Tesla, who were all fishing in the same talent pool with bigger paychecks and shinier stories.

The 5G Bet

Then, barely a month into independence, Nersesian made the kind of decision that either gets you celebrated or fired later.

In December 2014, Keysight committed $200 million—close to a tenth of annual revenue—to building 5G test capabilities. Commercial rollout was still years away. Even the standards weren’t finished. The board had every reason to hesitate.

Nersesian’s logic was simple. “We’re not betting on when 5G arrives,” he argued. “We’re betting that whoever helps create the standards will own the testing market.”

So Keysight didn’t just build products. It embedded itself in the formation of 5G. It worked with chipmakers, network equipment vendors, and carriers to define what “5G” would even mean in practice—and what would need to be measured to prove it worked.

The company also built 5G labs in Santa Rosa, Belgium, and Beijing, opening them up for early experimentation. It was a subtle flex: Keysight wasn’t merely selling instruments. It was positioning itself as the place the industry would come to figure things out.

Cultural Architecture

Culture usually forms over years. Keysight didn’t have that luxury.

Janet Krueger, Keysight’s Chief Human Resources Officer, ran what she called “cultural architecture”—designing values and rituals with the same intentionality the company brought to its instruments. The headline was “Speed, Focus, Accountability.” Less consensus-seeking. More decisions pushed to the edge, closer to customers. And more direct measurement of performance—fitting, in a way, for a company built on measurement.

But culture isn’t what you print on posters. It’s what you do when something goes wrong.

That test arrived in March 2015, when a major aerospace customer found measurement inconsistencies in a batch of signal analyzers. The traditional playbook would have been quiet containment: fix the units, minimize exposure, keep the lawyers comfortable.

Keysight went the other direction. Nersesian personally called each affected customer, explained what happened, and offered immediate replacements and extended warranties. The transparency cost the company about $30 million. It also bought something that doesn’t show up cleanly on an income statement: credibility.

The Modular Revolution

While 5G drew the attention, another shift was happening in parallel—one that quietly changed how Keysight could grow.

For decades, test equipment had been sold as monolithic, expensive boxes—bought, depreciated, then replaced when the next standard arrived. Keysight leaned hard into modular systems: core platforms with swappable modules, upgraded through software or add-on hardware.

PXI and AXIe weren’t just product lines; they were ecosystems. Customers could start small, then expand as requirements changed. More importantly, Keysight could ship software updates that unlocked new capabilities on hardware already sitting in customers’ labs. In other words: a box bought in 2014 could still be relevant years later, simply by upgrading what it knew how to do.

That wasn’t only good engineering. It was business model leverage.

Software revenue, previously almost nonexistent, climbed to about 15% of total revenue within 18 months. Customers who might have hesitated amid a new-company shakeout had a reason to commit: buy the platform now, evolve it later.

As Keysight closed fiscal 2015, the scoreboard was steady, if not yet flashy. Revenue came in around $2.9 billion—down slightly versus the prior year, pressured by currency and softer aerospace and defense spending. But there were two signals that mattered more than the headline number: independence was holding, and demand tied to 5G was starting to build.

Nersesian also knew something else. Focus and execution could take Keysight far—but not far enough, fast enough, to reshape the playing field.

At an October 2015 strategy session, he put a question to his leadership team that hung in the room a little longer than the rest:

What if, while everyone else was distracted, Keysight could buy its way into the next set of markets?

The company’s next chapter—its acquisition era—was already starting to take shape.

V. The Ixia Acquisition: A Transformative Bet (2017)

January 30, 2017, 5:47 a.m. Eastern. Bloomberg hit the tape: “Keysight to Acquire Ixia for $1.6 Billion Cash.”

In the small world of test and measurement, it landed like a thunderclap. Keysight—barely two years into life as an independent public company—was going to buy a business roughly a quarter its size. It would burn through most of Keysight’s cash and add meaningful debt. For a company still proving it could stand on its own, this was not a cautious move. It was a statement.

At Ixia, CEO Bethany Mayer had been taking calls for months. Private equity firms circled, attracted by Ixia’s fat gross margins and its strong position in network visibility. But when Ron Nersesian flew down to Ixia’s Calabasas headquarters for a quiet meeting in December 2016, he wasn’t pitching financial engineering. He pitched destiny: join Keysight, and together they could cover the entire network stack.

The Strategic Logic

Ixia didn’t look like traditional test and measurement. Keysight lived in the physical layer: signal integrity, power, frequency, RF. Ixia lived higher up, in the digital layers: protocol test, traffic generation, application performance, and security validation.

Founded by Errol Ginsberg and Joel Weissberger in 1997, Ixia had grown from an IP/Ethernet testing specialist into a leading provider of network test, visibility, and security tools. Its gear helped companies validate how networks behaved under load, how applications performed, and where vulnerabilities hid. They worked with names like Cisco, Alcatel-Lucent, Verizon, NTT, and Deutsche Telekom. They helped internet platforms keep experiences fast. They helped banks prove transactions were secure.

Nersesian’s framing to analysts was simple: “Keysight measures the physics. Ixia measures the experience.”

Put the two together and Keysight could offer something no one else could: testing from Layer 1 through Layer 7. From the radio waves carrying a 5G signal, to the protocols shaping packets, to the applications running on top. End-to-end.

And the timing wasn’t an accident. 5G wasn’t just “faster 4G.” It was an architectural reset—software-defined, virtualized, increasingly distributed out toward the edge. Testing that kind of network meant you couldn’t stop at RF performance, and you couldn’t start at application behavior. You needed both. Separately, Keysight and Ixia were each missing a crucial half. Together, they had a full story.

Keysight said the deal expanded its served addressable market by about $2.5 billion. It also laid out the kind of synergy math investors demand: roughly $60 million in annual cost synergies, and revenue synergies projected to build to more than $50 million by year three and $100 million by year five.

But the real logic was more visceral than any spreadsheet: Keysight didn’t want to be the company that tested pieces of 5G. It wanted to be the company that tested 5G.

The Negotiation Drama

The press release made it sound clean. It wasn’t.

In January 2017, with diligence nearly done, a private equity consortium dropped an unsolicited offer: $1.75 billion—about $150 million higher than Keysight’s bid. Ixia’s board had to take it seriously.

Nersesian had about 48 hours to decide what to do. If he raised the price, he’d likely need more debt, and that could put Keysight’s investment-grade ambitions at risk. If he walked away, he’d lose the strategic prize—and signal to the market that Keysight couldn’t close when it mattered.

So he did something that didn’t look like a counterbid at all. He invited Ixia’s leadership team into Keysight’s 5G labs.

It was, in a sense, orchestrated proof. Ixia’s executives watched demonstrations of millimeter-wave testing that wouldn’t be commercial for years. They talked with engineers who could go deep on the same protocol problems Ixia wrestled with. And they saw a roadmap where Ixia wasn’t a bolt-on—it was core to where Keysight was going.

That night, Mayer called Nersesian with the line that decided the deal: “The PE firms would make us more profitable. You’ll make us more important.”

Ixia’s board chose strategic fit over the higher number. The acquisition closed on April 18, 2017, at $19.65 per share, a 45% premium to Ixia’s unaffected stock price.

Integration Challenges

The celebration didn’t last long, because the hard part started immediately.

Keysight and Ixia didn’t just run on different IT systems. They ran on different instincts. Keysight was methodical, engineering-first, conservative. Ixia was fast, sales-driven, entrepreneurial.

The first integration meeting nearly went sideways. Keysight proposed bringing Ixia’s sales commissions in line with Keysight’s model—lower rates, more predictability. An Ixia top salesperson stood up, said he had three offers from competitors, and asked, “Who’s coming with me?” Half the room raised their hands.

Nersesian flew to Calabasas to defuse it personally. And instead of forcing a one-size-fits-all plan, he offered a compromise that felt almost like a Keysight product philosophy applied to people: modular, measured, iterative. Ixia salespeople could choose their compensation structure for 18 months. Performance data would determine the long-term approach.

Classic Keysight: don’t argue. Measure.

Then, six months into integration, another surprise surfaced. Ixia’s network visibility tools—built for performance testing—were increasingly being pulled into security use cases. Companies needed to observe encrypted traffic, detect anomalies, and spot threats. It wasn’t just testing anymore. It was defense.

Mark Pierpoint, who had led Ixia’s product development, pushed an idea that would have sounded wild to old-school instrument veterans: create a dedicated network security division inside Keysight, with its own P&L, sales motion, and development priorities. It wouldn’t compete with Tektronix or Rohde & Schwarz. It would show up against security vendors like Palo Alto Networks and FireEye.

Validation and Vindication

By late 2018, the Ixia bet was paying off beyond what skeptics expected. The network security division was producing $200 million in revenue and growing 30% year over year. Ixia’s protocol test business was winning meaningful 5G work with Samsung, Nokia, and emerging Chinese equipment manufacturers. And the combined story—physical layer through application layer—started to matter in a very specific way: it helped Keysight win broader, more comprehensive 5G test engagements.

But the most important outcome wasn’t just on the income statement. It was organizational.

This could have been a culture clash that poisoned the well: Ixia’s urgency versus Keysight’s patience; sales heat versus engineering gravity. Instead, the two sides sharpened each other. Ixia teams absorbed the power of deep technical credibility. Keysight teams picked up speed and a closer-to-the-customer edge.

Keysight turned the integration into a template: not assimilation, but connection. Nersesian called them “cultural bridges”—mixed teams on joint roadmaps, rotating leadership, shared innovation projects. The company that had spent 15 years being carved apart had learned something new: how to bring another company in without breaking what made it valuable.

With Ixia, Keysight stopped being “the box you buy to test a signal.” It started becoming a broader technology enablement platform.

And it was arriving just in time—because 5G was about to leave the lab and hit the real world.

VI. Building for 5G and Beyond (2018-2022)

Barcelona, February 2019. Mobile World Congress—the telecom industry’s annual Super Bowl. In Keysight’s booth, a crowd pressed in around what looked like a tall rack of gear: cables, blinking status lights, and the kind of hardware that only engineers find beautiful.

Then the moment landed. Keysight demonstrated what it described as the industry’s first live 5G New Radio call using commercial chipsets, base stations, and test equipment. This was the subtle but profound shift Keysight had been chasing: it wasn’t just measuring the future anymore. It was helping the industry bring the future into existence.

That same pattern showed up in its partnership with Qualcomm. Keysight had been working closely with the company for more than two years by that point, and the collaboration helped speed up real-world 5G launches in 2019. The company’s role wasn’t just “does it work?” It was “what does ‘working’ mean?”—setting the benchmarks that separated a barely functional connection from one that could actually carry the weight of a new generation of networks.

The Infiniium UXR Revolution

While 5G grabbed the spotlight, Keysight’s oscilloscope team was quietly building a monster.

In 2019, Keysight launched the Infiniium UXR-Series—an aggressive leap in oscilloscope performance, with up to 256 GHz of bandwidth, 10-bit analog-to-digital converters, and noise levels so low they pushed toward theoretical limits. In top configurations, it could cost more than $500,000. That number sounds ridiculous until you understand what the buyers were really paying for: the ability to see a problem that otherwise stays invisible.

An oscilloscope is essentially a camera for electrical signals. Bandwidth is how fast a signal can change before your “camera” starts blurring the picture. At 256 GHz, the UXR could capture signals changing hundreds of billions of times per second. For context, FM radio is around 100 million cycles per second. This was a different universe.

The UXR also reflected Keysight’s evolved approach to innovation. Instead of building a spec sheet in a vacuum, Keysight spent roughly two years embedded with customers working on next-generation semiconductors, optical communications, and early-stage quantum systems. The lesson wasn’t simply “we need more bandwidth.” It was that engineers needed to understand signal integrity in regimes where the signal itself was barely distinguishable from the noise. The UXR didn’t just measure faster. It surfaced behaviors engineers hadn’t been able to reliably observe before.

Intel’s validation labs adopted UXR scopes for 7nm and 5nm process development. One engineer summed up the vibe: “We’re seeing things we didn’t know existed.” The tools were so sensitive they sometimes needed isolation from vibrations as basic as someone walking nearby. It was a strange kind of success—building an instrument whose precision could outstrip the stability of the environment around it—and it spoke directly to Keysight’s moat: when the frontier moves, the company that can measure it gets invited to define it.

COVID's Unexpected Acceleration

March 2020 should have been brutal. Keysight sold premium hardware into labs and engineering teams—exactly the kind of spending you’d expect to freeze when the world shut down. As travel stopped and facilities closed, the old mental model of the business—big instrument sales, hands-on demos, engineers crowded around benches—suddenly looked fragile. The stock fell sharply, dropping from around $110 to $75 in a matter of weeks.

And then the world delivered a twist.

The pandemic didn’t slow the demand for electronics and connectivity. It pulled it forward. Video calls hammered networks. Remote work exposed brittle infrastructure. School, medicine, shopping—everything tilted toward digital, and it became obvious that society was leaning on networks that weren’t built for that level of load.

Keysight adapted faster than most people expected from a company with so much hardware heritage. Within weeks, it stood up remote and “virtual demo” capabilities: customers could control instruments in Keysight labs from thousands of miles away and run their own tests as if they were in the room. PathWave—Keysight’s software platform—went from helpful to essential. Customers could simulate, design, and validate with less dependency on physically being near the equipment.

That shift changed the business. Software and services grew meaningfully as a share of revenue from 2019 into 2021, and the mix mattered: software carried significantly higher gross margins than hardware, which helped lift overall profitability even when parts of the hardware cycle softened.

The results showed up quickly. Fiscal 2020 became a record year for orders, gross margin, operating margin, earnings per share, and free cash flow. Fiscal 2021 followed with strong growth and new highs across orders, revenue, and margins. The crisis that seemed like it could stall Keysight ended up accelerating the company into the next version of itself.

The Eggplant Acquisition

In June 2020, while much of corporate America was still in defensive mode, Keysight leaned forward again. It acquired Eggplant—an AI-powered software testing platform—for $330 million.

At first glance, Eggplant didn’t look like a natural fit for a company famous for oscilloscopes and spectrum analyzers. But the strategic logic was consistent with the Ixia playbook: the world was becoming software-defined. Testing the hardware was no longer enough. The customer experience—what actually happens when a real person uses a system—was increasingly the product.

Eggplant’s CEO, John Bates, brought a software-first sensibility that landed with impact inside Keysight. He framed the difference in plain language: “You test if a 5G signal reaches a phone. We test if grandma can actually make a video call to her grandchildren. Both matter.” It wasn’t just an acquisition of a capability. It was an acquisition of a point of view—moving Keysight’s ambition from measuring signals to validating real-world outcomes.

Automotive's Hidden Opportunity

While the public story centered on 5G, another wave was building quietly—and it turned out to be one of Keysight’s most important growth engines: automotive electronics.

Electric vehicles, advanced driver assistance, and the long push toward autonomy created a testing problem that looked increasingly familiar to Keysight. Cars were becoming rolling computers: software-heavy, sensor-packed, connected, and safety-critical. Every subsystem had to be validated, and the consequences of failure weren’t a dropped call—they were life and death.

Keysight leaned into the opportunity, building tools and solutions for automotive design and validation. Its automotive solutions business grew from about $200 million in 2018 to more than $500 million by 2021. And the value wasn’t only in individual instruments. Keysight helped customers create “digital twins” that could simulate vehicle behavior across huge numbers of scenarios before committing to physical prototypes. As EV makers and autonomy teams pushed faster, the ability to test more, earlier, and with higher confidence became a competitive advantage.

Then came the semiconductor shortage, which revealed another truth about Keysight’s model. When chips were scarce, manufacturers still had to test every unit they could make—and with constrained supply, no one could afford defects. Testing didn’t become optional. It became more central. Keysight’s semiconductor test revenue grew even as the broader chip industry faced pressure.

Preparing for Transition

By early 2022, Ron Nersesian had been leading Keysight for eight years—through the spin-off, the early “prove it” years, and then the push into software, networks, and new end markets. The stock had climbed from around $37 at independence to above $150. The company looked and behaved very differently than it had on Day One.

Nersesian was also realistic about what the next chapter would demand. The center of gravity was shifting further toward software, workflow integration, and industry-wide digital transformation. Keysight needed a leader who could speak the language of measurement and the language of modern computing.

The succession plan reflected that. Satish Dhanasekaran had been brought in and served as Chief Operating Officer since 2020, spending two years getting deep into the business. He had an electrical engineering PhD, deep semiconductor expertise, and a software-oriented view of where the industry was headed. In May 2022, Keysight announced he would become President and CEO, with Nersesian staying on as Executive Chairman.

The handoff wasn’t about fixing a problem. It was about matching leadership to the moment. With 5G deployment ramping, automotive electronics surging, and software becoming central to how testing was delivered and monetized, Keysight was setting itself up for a more ambitious phase—one that would stretch far beyond “instruments” and into the future of how complex systems get designed, validated, and trusted.

VII. Modern Era: AI, Quantum, and Strategic M&A (2023-Present)

The quantum computer didn’t look like a computer at all.

In IBM’s Quantum Network lab in Yorktown Heights, the star of the room was the dilution refrigerator—an intricate tower of metal plates and cables that felt closer to modern sculpture than to Silicon Valley hardware. Somewhere deep inside it, at temperatures near absolute zero, qubits flickered in and out of fragile quantum states. And right next to IBM’s team, Keysight engineers were doing what they’ve always done best: building the measurement and control systems that make the impossible behave like a machine.

Quantum can sound mystical, but the practical challenge is brutally concrete. Qubits are like bits’ strange cousins. A normal bit is either 0 or 1; a qubit can exist in a superposition of states. To do anything useful with that, you have to control qubits with exquisitely precise microwave pulses—timed down to billionths of a second—while the whole system is colder than outer space. For all the quantum weirdness, the work of making it run is a classical problem: generate signals, control noise, verify behavior, repeat. In other words, measurement.

“Classical computing is reaching physical limits,” Satish Dhanasekaran told investors in early 2023, now firmly in the CEO seat. “Quantum computing isn’t just faster—it’s fundamentally different. And every quantum computer needs classical control systems to function. We’re building the bridge between quantum and classical worlds.”

That line mattered because it framed Keysight’s modern era perfectly. The company wasn’t betting on one moonshot. It was positioning itself as the infrastructure layer for multiple frontiers at once: AI, quantum, 6G, and the software transformation that would tie them all together.

The ESI Group Acquisition

In June 2023, Keysight announced it would acquire ESI Group for approximately 913 million euros (roughly $1 billion), paying 155 euros per share.

ESI wasn’t a test-and-measurement company in the traditional sense. Founded in 1973, it built physics-based simulation software that models the real world: how materials bend, where stress concentrates, what breaks first. It could simulate everything from manufacturing processes to vehicle crashes.

The strategic logic was bigger than “add software.” Keysight already had the tools to measure reality with extreme fidelity. ESI could model that same reality before it existed. Combine them, and you start collapsing the boundary between simulation and real-world validation.

Dhanasekaran’s framing was direct: “We’re collapsing the boundary between simulation and reality.” ESI could simulate a car crash down to deformations and stress points. Keysight’s instruments could measure physical crash tests. Together, they could enable digital twins accurate enough that companies could learn faster with fewer physical prototypes. For automakers racing toward electric and autonomous vehicles, that wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was a time-to-market weapon.

The Spirent Acquisition

In March 2024, Keysight announced its boldest move yet: an agreement to acquire Spirent Communications for approximately $1.46 billion (about 1.16 billion pounds).

Spirent was a UK-based testing specialist and, in many areas, a long-time rival. This wasn’t an adjacency play. It was consolidation—an attempt to put two major players under one roof and deepen Keysight’s reach across the networking lifecycle.

Spirent brought capabilities Keysight wanted, including lifecycle service assurance and positioning technologies. Just as important, Spirent brought customer relationships—particularly with hyperscalers and cloud providers—that Keysight had found harder to crack.

But the deal came with a catch: regulators.

Approval wasn’t a single hurdle; it was a gauntlet. The acquisition needed clearances from the US Department of Justice, the UK Competition and Markets Authority, French and German ministries, and China’s SAMR. As antitrust concerns mounted, Keysight agreed—under a DOJ consent decree—to divest significant pieces of Spirent’s business, including high-speed Ethernet, network security, and channel emulation, to VIAVI Solutions. It was a meaningful concession, and a reminder that scale cuts both ways: it creates advantage, and it invites scrutiny.

On October 15, 2025, the acquisition finally closed. Spirent was integrated into Keysight’s Communications Solutions Group, ending an 18-month-plus process that tested Keysight’s patience, deal discipline, and willingness to give up revenue to secure the strategic core.

The AI Testing Revolution

While acquisitions made the headlines, a quieter shift was reshaping the center of the company: AI.

Not AI as something customers were building—though that was happening too—but AI as a new way to test complex systems. Traditional testing is scripted. You define scenarios, run them, and check expected outcomes. That approach breaks down when systems become too dynamic and interconnected for humans to anticipate every failure mode.

Keysight’s AI-driven testing platform, launched in 2023, pushed in a different direction. It could generate massive numbers of test scenarios autonomously, exploring the parameter space far beyond what a team could design by hand. The payoff was speed and coverage. Work that could take months of manual validation could be compressed into days, and the system could surface edge cases humans would never think to look for. In one case, a customer found a critical vulnerability that only appeared when a specific combination of temperature, frequency, and load aligned—exactly the sort of multi-variable coincidence that slips through scripted plans.

Then in December 2025, Keysight brought that AI layer closer to everyday engineering workflows. It introduced AI-powered Chat and Copilot assistants for Advanced Design System (ADS), enabling natural-language interactions and on-premises deployment. Engineers could describe what they wanted to analyze in plain English, and the tools could help configure the workflow.

Quantum Computing’s Classical Challenge

By late 2025, Keysight had also turned quantum into something more than a research collaboration—it had become a product leadership position.

In July 2025, Keysight delivered what it described as the world’s first commercial quantum control system supporting over 1,000 qubits to Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST). The point wasn’t only the number. It was the implication: quantum systems were starting to scale toward commercially relevant sizes, and the bottleneck wasn’t just qubit design. It was control, calibration, measurement, and repeatability.

Keysight’s strategy was to partner broadly—working with IBM, Google, Fujitsu, IQM—while staying technology-agnostic. If the quantum world needed a “Switzerland,” Keysight was volunteering for the job: build the control systems that work across approaches, while others argue over which qubit modality wins.

The company also expanded its electronic design automation offerings for quantum systems. Its Quantum EDA portfolio included Quantum Layout, QuantumPro EM, and Quantum Circuit Simulation—tools intended to bring system-level simulation and optimization discipline to quantum engineering, the same way EDA did for classical electronics.

6G and the Next Horizon

Even with 5G still rolling out globally, Keysight was already busy defining what came next.

The company’s labs in Finland and Japan were exploring terahertz frequencies—regimes where wavelengths become so short they start behaving more like light than radio. 6G, in that vision, wouldn’t just be “faster.” It would open doors to entirely new applications, from richer immersive communications to always-present ambient connectivity.

In December 2025, Keysight and KT SAT demonstrated what they described as the industry’s first live NR-NTN (New Radio Non-Terrestrial Network) multi-orbit handover between commercial GEO (geostationary) and emulated LEO (low-earth orbit) satellites. It was a concrete demonstration of something that will matter deeply as networks extend beyond cell towers into space.

Keysight also signed a memorandum of understanding with Samsung Research to advance 6G R&D. The company was investing heavily—over $500 million annually, as described here—because it understood the playbook from 5G: if you help define the standard, you don’t just sell into the market. You shape it.

Financial Recovery and Momentum

Fiscal 2025, ending October 31, 2025, marked a clear recovery. Revenue rose to $5.37 billion, up from $4.98 billion in fiscal 2024. Fourth quarter revenue reached $1.42 billion versus $1.29 billion the year prior. GAAP net income was $846 million ($4.89 per share), and non-GAAP net income was $1.24 billion ($7.16 per share).

Keysight also announced a new $1.5 billion share repurchase program, signaling confidence in its cash generation. For the first quarter of fiscal 2026, management guided to revenue of $1.53–$1.55 billion and non-GAAP earnings per share of $1.95–$2.01.

But the most telling indicator of where Keysight was headed wasn’t any single quarter. It was the mix. Software and services had grown to about 39% of revenue, up from less than 10% at independence. Annual recurring revenue was approaching $1.5 billion—roughly 30% of total revenue—giving Keysight a steadier base than a pure hardware cycle ever could.

After three corporate lives—HP, Agilent, Keysight—the company had become something new again: not just the best at measuring the world as it is, but increasingly a software-centric platform for validating the world as it’s being built.

VIII. Business Model & Competitive Moats

Walk into a conference room at Keysight’s Santa Rosa headquarters and it feels less like a place for PowerPoints and more like a control tower. Screens track software renewals, R&D milestones, and win rates by region. CFO Neil Dougherty points to the dashboards and makes the case that outsiders keep missing what Keysight actually is.

“People look at us and see expensive hardware,” he says. “They assume we’re a capital equipment company. But look closer. Nearly 40% of revenue is software and services now. And most customers come back fast. This is not a one-and-done purchase. It’s an ongoing relationship.”

That’s the trick: Keysight may be famous for “boxes,” but the business is built like a platform.

The Revenue Architecture

Keysight’s revenue starts with hardware: the oscilloscopes, analyzers, and systems that show up on lab benches and factory floors. Those sales bring in big dollars up front, with gross margins typically in the mid‑50s to around 60%.

Then comes everything wrapped around the hardware—where the economics get more interesting.

Software licenses can run at roughly 85–90% gross margins. Services—calibration, support, and other programs that keep instruments accurate and productive—often land in the 70% range and tend to be steady year after year.

The compounding comes from how customers buy. A semiconductor manufacturer doesn’t just purchase a high-end test system. They add PathWave subscriptions for design validation, calibration contracts to keep measurements certified, and training so their engineers can actually use the capabilities they paid for. The first sale might look like a single transaction. The lifetime relationship looks more like an account with an expanding footprint.

Keysight’s modular platform strategy reinforces that. The old pattern in test equipment was brutal: buy a big box, depreciate it, then replace the whole thing when the next standard arrives. With modular systems, customers can upgrade in pieces—new measurement modules, software updates, expanded frequency ranges. A platform deployed years ago can stay relevant as requirements change, as long as it keeps evolving. And if it keeps evolving, the customer keeps buying.

Customer Lock-in Through Complexity

Keysight’s switching costs aren’t just financial. They’re operational.

Yes, customers may have millions of dollars of equipment installed. But the real lock-in is the infrastructure built around it: custom test scripts, validated workflows, production procedures, documentation, and, in regulated industries, certifications tied to specific instruments and methods.

One aerospace manufacturer put it plainly: “We have thousands of test procedures written for Keysight equipment. Each took months to develop and validate. Switching would mean rewriting everything, retraining everyone, and recertifying with the FAA. The cost isn’t the new instruments. It’s the knowledge base we’d have to rebuild.”

As systems get more complex—5G networks, autonomous vehicles, advanced semiconductor nodes—the lock-in deepens. Testing becomes less about owning equipment and more about having the expertise to use it correctly. Keysight’s application engineers, who specialize by domain, often work side by side with customers. Over time, Keysight stops feeling like a vendor and starts feeling like part of the engineering process.

R&D: The Innovation Imperative

Keysight spends heavily on R&D—roughly the mid‑teens as a percentage of revenue, adding up to more than $800 million a year in recent years. For Keysight, that isn’t a “growth investment” in the abstract. It’s a survival requirement.

Technology moves fast. The uncomfortable reality of the test business is that you need to measure tomorrow’s designs before tomorrow arrives. If your customer is pushing into a new frequency range, a new modulation scheme, or a new packaging method, they need instruments that can see problems that no one has seen before. The test vendor that arrives late doesn’t just miss a product cycle—it risks getting designed out for a decade.

Keysight’s R&D work runs in three lanes at once:

First: fundamental measurement science—pushing the frontier of bandwidth, noise, accuracy, and signal processing. The UXR oscilloscope family is the poster child here: getting to extremes like 256 GHz bandwidth required real breakthroughs in converters, processing, and noise control, developed over years.

Second: market-specific solutions. Dedicated teams focus on major verticals like 5G, automotive, aerospace, and semiconductors. Their job isn’t simply to repackage instruments; it’s to build workflows and systems that match how customers actually develop products. That can mean entirely new approaches and purpose-built setups for a given domain.

Third: software platforms. PathWave is designed to connect design, simulation, and measurement so teams aren’t stuck in a slow, linear “design, build, test” loop. The goal is tighter iteration—where results from the lab feed back into design decisions continuously.

Operating Segments and Geographic Diversification

Keysight runs through two main segments. The Communications Solutions Group serves commercial communications customers alongside aerospace, defense, and government. The Electronic Industrial Solutions Group spans general electronics, automotive, and energy or manufacturing.

Geographically, revenue is spread across the Americas, Asia-Pacific, and Europe in proportions that roughly mirror where technology is being designed and deployed. That balance matters. A slowdown in one region or end market can be offset by acceleration in another—not perfectly, but often enough to dampen volatility.

Keysight also sells to a broad base of customers, with no single customer accounting for more than 10% of revenue. That keeps the company from living or dying by any one relationship, while still allowing large programs to matter.

The Services Transformation

Services have become one of Keysight’s quiet stabilizers.

Calibration is a great example. Measurement equipment only has value if customers can trust it. Many customers can’t afford downtime, and regulated industries often require documented accuracy. That creates an annuity-like motion: recurring service revenue tied directly to the installed base.

Keysight also generates revenue through programs like Keysight Labs, where customers can access cutting-edge setups, and through training and certification, which helps customers deploy equipment effectively while deepening reliance on Keysight’s workflows.

Then there’s KeysightCare: a bundled support offering that combines hardware coverage, software updates, and application support into an annual fee. It’s part insurance, part subscription, part operational dependency. And importantly for Keysight, it’s sticky—renewal rates exceed 90%.

Competitive Dynamics and Differentiation

Keysight competes with familiar names: Tektronix in oscilloscopes, Rohde & Schwarz in RF and spectrum, National Instruments in software-defined and modular approaches, and a growing set of Chinese vendors that win on price.

But Keysight’s advantage isn’t just breadth. It’s the ability to show up at the frontier. In many categories, competitors can produce “good enough” tools for mature needs. Keysight’s differentiation shows up when customers are working on the next standard, the next node, the next architecture—when the measurement problem itself is still being defined.

There’s also a competitor that doesn’t show up on market share charts: customers trying to build it themselves. The largest tech companies sometimes attempt internal test platforms. But keeping pace with standards, building the expertise, and maintaining accuracy over time is expensive. The complexity tends to push many of them back toward specialist vendors.

As one customer put it: “We tried spending tens of millions building our own 5G test platform. It would have been cheaper to buy Keysight’s and have it work immediately.”

Capital Allocation and the M&A Pattern

Keysight’s financial model—strong margins and meaningful free cash flow—gives it flexibility. It can fund R&D, return capital to shareholders, and still have room for acquisitions without turning the balance sheet into a high-wire act.

The acquisition pattern is consistent: buy capabilities that extend Keysight up the stack or earlier in the workflow, then sell them through the same customer relationships. Ixia added network visibility and protocol testing. Eggplant brought software testing. ESI Group added physics-based simulation. Spirent expanded network testing and assurance. Each deal broadened the platform while leveraging Keysight’s credibility in measurement.

The Platform and the Standard-Setter Moat

As PathWave and the broader software ecosystem spread, something subtle happens: customers accumulate shared libraries, procedures, and best practices that make Keysight easier to use—and harder to leave. The ecosystem becomes self-reinforcing, not because Keysight runs a social network, but because engineering workflows get standardized and reused.

Keysight’s partnerships deepen that effect. Its tools integrate with major EDA vendors, manufacturing systems, and enterprise software, which makes Keysight feel less like a product you buy and more like infrastructure you plug into.

And beneath all of it is the deepest moat Keysight has: credibility as a source of measurement truth.

In industries where performance claims get disputed—does the signal meet spec, is the device compliant, did the system fail because of design or environment—someone has to be the referee. Keysight’s instruments and methods often become the reference point. When you’re the one defining what “accurate” means, you’re not just competing on features. You’re competing from the high ground.

IX. Playbook: Lessons in Corporate Strategy

In the years after the spin, Ron Nersesian had a way of reducing messy debates into something you could write on a whiteboard and argue about. The shorthand he came back to, again and again, was simple: focus creates outsized value.

Looking at Keysight’s lineage—HP splitting to create Agilent, and then Agilent splitting again to create Keysight—the result almost feels backwards. The company kept getting carved into smaller pieces, and yet the piece that became Keysight kept getting sharper, more specialized, and ultimately more valuable. The apparent paradox is the point.

“Every corporate strategy textbook says diversification reduces risk,” Nersesian would later reflect as Executive Chairman. “But in technology, diversification often increases risk by diluting focus. Sometimes the best way to grow is to shrink your scope.”

The Power of Focus

Keysight’s three-generation spin story is a masterclass in what focus actually means in practice. HP in the 1990s was trying to be everything at once: computers, printers, test equipment, medical devices. Inevitably, attention and investment chased the loudest, fastest-growing businesses. The quieter, deeply technical instrument work that built HP’s reputation risked becoming “important, but not urgent.”

The first lesson is brutally simple: in technology markets, focus beats diversification—because focus is what allows you to keep up. A focused company makes faster decisions. It allocates resources without internal turf wars. It doesn’t force engineers to compete with unrelated divisions for R&D dollars. It doesn’t ask sales teams to juggle conflicting priorities. It doesn’t spend leadership time refereeing budget battles between businesses that don’t share customers, roadmaps, or learning loops.

But focus by itself isn’t a strategy. The second lesson is choosing the right kind of focus.

Keysight didn’t just inherit “test and measurement.” It narrowed the definition to the hardest, highest-performance parts of the world—high-frequency, high-precision, standards-defining measurement problems where technical barriers are real and credibility compounds. That wasn’t shrinking to survive. It was narrowing the aperture to dominate the frontier.

M&A as Capability Building

Keysight’s M&A strategy breaks the usual stereotype. It isn’t shopping for scale. It isn’t primarily buying cost synergies. It buys time.

Each major deal has the same underlying logic: there are capabilities that would take too long to build internally, and being late is the same as losing. Acquisitions are used to fill specific gaps in the technology stack or the customer workflow—especially as testing moves “up the stack” from pure physics into protocols, software behavior, and system outcomes.

Ixia is the cleanest example. Keysight could have tried to build network visibility and protocol testing on its own, but it likely would have taken years and come with high execution risk. Buying Ixia delivered proven technology, established customer relationships, and immediate credibility in domains Keysight needed to own for 5G and modern networking. The $1.6 billion price tag looked aggressive—until you compare it to the cost, time, and uncertainty of building the same capability from scratch.

The integration approach follows the same philosophy. Keysight doesn’t try to sand down everything that makes an acquired company effective. It preserves the edges. Ixia kept its urgency and sales drive. Eggplant kept its software-first worldview. ESI Group kept its simulation depth. Integration happens where the customer experiences the company: a unified solution assembled from distinct strengths, instead of a forced assimilation that destroys what you bought.

Technology Transition Navigation

Every major transition threatens incumbents: analog to digital, hardware to software, 4G to 5G. Keysight has navigated repeated resets with a consistent playbook: anticipate, invest early, and be willing to cannibalize yourself before someone else does.

The software shift is the clearest proof. Early on, Keysight was still seen as a hardware company with some software attached. The easy move would have been to protect hardware margins and treat software as an accessory. Instead, Keysight invested aggressively—building platforms, adding software capabilities through acquisitions, and pushing solutions that, in some cases, made hardware less central. That’s a hard choice for any instrument company. It worked because Keysight treated it as an evolution of the mission, not a threat to the legacy.

The deeper insight is uncomfortable but useful: transitions are inevitable. The only real decision is whether you shape them or get shaped by them. Keysight’s early 5G investment didn’t just prepare for the market. It helped define what the market would require—and therefore what customers would later need to buy.

Capital Allocation Discipline

Keysight’s capital allocation has a clear order of operations: invest in R&D to maintain technical leadership; pursue acquisitions that expand capabilities and workflows; then return capital to shareholders when there’s excess.

That discipline shows up in the company’s willingness to say no. It walks away from deals that don’t strengthen differentiation, even if the cost synergy story looks tempting. And it has shown a willingness to pay up for assets that change what Keysight can do—because unique capability, in markets defined by standards and credibility, is worth more than cheap scale.

A conservative balance sheet and strong free cash flow make that possible. Financial flexibility becomes its own competitive edge: Keysight can move when an opportunity matters, without turning every bet into an existential one.

Culture as Strategy

Keysight’s cultural shift—from HP’s slower, consensus-driven heritage to “Speed, Focus, Accountability”—wasn’t internal branding. It was strategic positioning.

In fast-moving tech markets, speed is not a nice-to-have. It determines who gets invited into the room when standards are written, reference designs are chosen, and development workflows get locked in. Many of Keysight’s defining moves required acting before certainty arrived: the early 5G investment, the Ixia acquisition, the commitment to quantum control systems before quantum had a commercial market.

But this isn’t speed for speed’s sake. The cultural point is alignment. Keysight’s organization is built around a crisp mission: help customers innovate faster, with measurement they can trust. When that mission is clear, decision-making friction drops. Engineers know why the work matters. Sales teams know what they’re selling beyond specs. Support and services know they’re protecting customer confidence, not just closing tickets.

Ecosystem Orchestration

Keysight doesn’t just sell into ecosystems; it helps convene them.

Its 5G labs, research partnerships, and collaborative environments create neutral ground where customers—and sometimes rivals—work through the messy early problems together. That role is subtle, but it has compounding benefits. Keysight sees requirements before they’re obvious. It influences how standards and specifications are interpreted in practice. It reduces product development risk by learning directly from the frontier.

The best version of this strategy turns Keysight into something more than a vendor: a place where industries go to find the truth early, before reality is standardized.

The Platform Paradox

There’s one more twist in Keysight’s evolution: the move toward platform-style economics in markets that aren’t “internet scale.”

Platforms usually get stronger with millions of users. Keysight doesn’t have millions of users. It has thousands of highly specialized engineers and teams building the most complex systems in the world. So Keysight’s platform advantage isn’t about mass adoption—it’s about depth.

When a platform becomes embedded in an engineering workflow, it accumulates procedures, scripts, compliance artifacts, models, and tribal knowledge. The value isn’t social; it’s operational. These are power users who depend on the platform daily, and who share methods and solutions because their incentives align: ship faster, with fewer surprises.

The overarching lesson in Keysight’s playbook is that focus and flexibility aren’t opposites. They reinforce each other. Focus creates credibility and leadership at the frontier. Flexibility—through M&A, platforms, and ecosystem positioning—extends that leadership into adjacent problems without losing the thread.

Keysight looks like a company that “does measurement.” In reality, it’s a company that keeps expanding what measurement means—while staying obsessively committed to being the one everyone trusts when the stakes are highest.

X. Analysis & Investment Case

An analyst can stare at Keysight’s financials and come away with two completely different narratives.

Fiscal 2024 looked ugly: revenue of $4.98 billion, down 8.9% year over year, with net income of $614 million, down 42.4%. If you stop there, it reads like a company losing momentum.

Then fiscal 2025 showed up: revenue rebounded to $5.37 billion and GAAP net income rose to $846 million. And the forward-looking signals—design win momentum, expanding software annual recurring revenue, deeper 6G engagement—suggested the engine hadn’t stalled. It had been cycling.

That’s the Keysight paradox. In any given year, results can look like “just another hardware cycle.” Over a decade, the compounding tends to come from being early to the next transition—and becoming embedded before everyone else even agrees what the transition is.

“The mistake investors make,” explains a portfolio manager who’s owned Keysight since the spin-off, “is viewing this as a cyclical hardware company. Yes, revenues fluctuate with R&D spending. But the underlying value compounds through technology transitions. We’re not buying this year’s earnings; we’re buying the next decade’s innovation enablement.”

Market Position Dynamics

Keysight’s market position is strongest where performance is non-negotiable.

At the high end, it competes in categories where “good enough” doesn’t exist. In those pockets, Keysight has products that customers treat as reference-grade: the Infiniium UXR at the bleeding edge of scope performance, flagship 5G emulation platforms that show up early in standards work, and quantum control systems that are still a small market but already shaping what “commercial” even means. In those segments, competition thins out fast, and Keysight can sustain premium pricing because the alternative isn’t a cheaper box—it’s not being able to see the problem.

The vulnerability shows up outside that rarified air. In general-purpose instruments, Asian manufacturers can offer acceptable performance for dramatically less money. In software-defined and modular testing, companies like National Instruments can look attractive to teams optimizing for flexibility and cost. The risk for Keysight isn’t losing the frontier. It’s failing to expand profitably into the broader “good enough” middle without diluting what makes it special.

Geography adds another layer. Asia-Pacific, about 35% of revenue, is both the center of gravity for aggressive technology development and a region full of geopolitical and regulatory uncertainty. Restrictions on Chinese customers—particularly in 5G and semiconductors—create real friction. Keysight has to keep leaning into where the innovation is happening while staying resilient to where politics can interrupt demand.

Bull Case: Innovation Infrastructure

The bull case is simple to say and hard to replicate: Keysight is becoming essential infrastructure for innovation.

Every major technology wave—6G, AI data centers, quantum computing, autonomous and electric vehicles—creates systems that are more complex, less forgiving, and harder to validate. As complexity rises, testing isn’t a line item you cut; it’s what lets you ship at all. Keysight’s best positioning is when testing stops being “a tool” and becomes “the gate that determines whether the product is real.”

Software makes that positioning more valuable. Hardware used to be a large, infrequent purchase. Software subscriptions and services turn that into an ongoing relationship: updates, workflows, automation, and support wrapped around an installed base that customers rely on daily. The business becomes less about the initial instrument sale and more about how deeply Keysight is integrated into how the customer builds and proves systems.

The acquisitions are meant to reinforce exactly that. Spirent adds lifecycle service assurance that rounds out network test beyond the lab. ESI Group adds simulation that pushes Keysight earlier in the workflow—before physical prototypes exist. The strategic argument isn’t “more revenue.” It’s more control of the workflow, higher switching costs, and a broader definition of what Keysight can be the system of record for.

From there, the upside scenarios are familiar because Keysight has run this playbook before. 6G could become another multi-year standard cycle where the early enablers take disproportionate share. And quantum, while still emerging, has a very specific angle where Keysight is already relevant: as qubit counts climb, control and measurement doesn’t scale nicely—it gets harder. If quantum systems do move toward commercial viability, the “classical plumbing” around them becomes a real market, not a research accessory.

Bear Case: Cyclical Pressures and Disruption Risks

The bear case starts with the obvious: Keysight still sells a lot of premium capital equipment, and budgets do get delayed.

When macro uncertainty rises, enterprises can push out lab expansions and large instrument refreshes. The semiconductor industry—one of Keysight’s most important customer groups—moves in cycles. Even if long-term trends are favorable, quarter-to-quarter timing can be punishing, and the market rarely has patience for “it’ll come back next year.”

Then there are the disruption angles, some of which are already visible at the edges. Large customers—especially hyperscalers—sometimes build internal test capabilities. AI-driven approaches may reduce the amount of traditional scripted testing required, changing where value accrues. Software-defined workflows can also shift differentiation away from hardware, which cuts both ways for a company with deep instrument heritage.

M&A adds its own risk. Spirent came with regulatory complexity and required divestitures that reduced some of the original scope. ESI Group is a different kind of organization—simulation-heavy, software-centric—and integration takes time and management attention. Keysight’s acquisition strategy has been a strength, but it only stays a strength if the company continues to execute and integrate without losing focus.

Finally, there’s the risk of timing and trajectory. If quantum commercialization takes longer than expected, or if 6G’s technical path changes, Keysight’s “early leadership” could take longer to translate into revenue than the market wants. Concentration in a handful of major technology transitions is powerful when you’re right—and uncomfortable when timelines slip.

Applying Strategic Frameworks

Through the lens of Porter’s Five Forces, Keysight competes in an industry structure that is generally favorable for incumbents.

Supplier power is manageable: Keysight has scale and can source many components across multiple vendors, though high-performance hardware always carries some supply-chain sensitivity. Buyer power is constrained by switching costs, because customers aren’t just buying instruments—they’re buying validated workflows, compliance artifacts, and internal expertise built around Keysight systems. The threat of new entrants is low: the R&D burden, credibility hurdle, certifications, and relationships create real barriers. Substitutes are a mixed bag: some customers do build internal solutions, but complexity often pushes them back toward specialists. Rivalry exists, but it’s concentrated among a small set of global players, and Keysight’s position at the high end supports disciplined pricing.

Through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, Keysight shows multiple “powers” at once. Scale economies show up in R&D leverage—its annual R&D spend is hard for smaller competitors to match. Switching costs are real and compounding, embedded in test procedures, automation, and certifications. Network economies appear in the ecosystem around PathWave and the broader workflow integrations. And there’s an element of counter-positioning as Keysight shifts toward software and services—moves that can be harder for legacy hardware-first competitors to follow without disrupting their own models.

Key Performance Indicators

For investors trying to separate “cycle” from “compounding,” two metrics do most of the work:

Software and Services as Percentage of Revenue: This is the clearest read on whether Keysight is continuing its shift from a primarily hardware business toward a platform model. At the spin-off, software was less than 10% of revenue. It has since climbed to around 40%. If that mix keeps moving up, it typically supports higher margins and smoother results across cycles.

Annual Recurring Revenue Growth: ARR captures how much of Keysight’s revenue is repeatable through subscriptions and service relationships. If ARR grows faster than total revenue, it’s a sign the business is becoming more durable and that customers are staying inside the ecosystem.

Together, they track the core bet: that Keysight is moving from selling instruments to selling ongoing measurement capability—delivered through software, workflow, and support.

The Investment Decision

Keysight doesn’t fit neatly into a single bucket. It’s not pure growth. It’s not deep value. It isn’t “just hardware,” and it isn’t “just software.” It’s a company in the middle of a long transformation, operating in markets where timing is lumpy but leadership can last for years once established.

A rational stance is to treat it like a position you earn over time: build during weakness, stay disciplined about what’s actually improving, and watch whether software mix and recurring revenue continue to strengthen. The strategic position is compelling, but the pathway to value realization still depends on execution—on integration, on staying ahead of standards, and on continuing to convert measurement leadership into workflow ownership.

The real question isn’t whether Keysight can measure the future. It’s whether it can keep turning those measurements into a business the market understands and rewards. That score gets updated every quarter—but the game plays out over decades.

XI. Epilogue & Reflections

The garage at 367 Addison Avenue still stands. It’s quiet now—more shrine than workshop—preserved down to the workbench, the stray components, the hand-drawn circuit sketches. Tourists shuffle through, take photos, and read the plaque that calls it the “Birthplace of Silicon Valley.”

What the plaque can’t capture is the strange truth of this story: the company that began in that garage never really went away. It kept shedding skin.

Ron Nersesian, after handing the CEO role to Satish Dhanasekaran in 2022 and becoming Executive Chairman, has occasionally returned on crisp Palo Alto mornings. Sometimes he brings new engineering graduates. Not for nostalgia, but for orientation—an attempt to connect a company now spanning software platforms, network assurance, and quantum control systems back to the simplest possible origin: two engineers trying to measure something accurately.