KKR & Co.: The Evolution of Private Equity

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

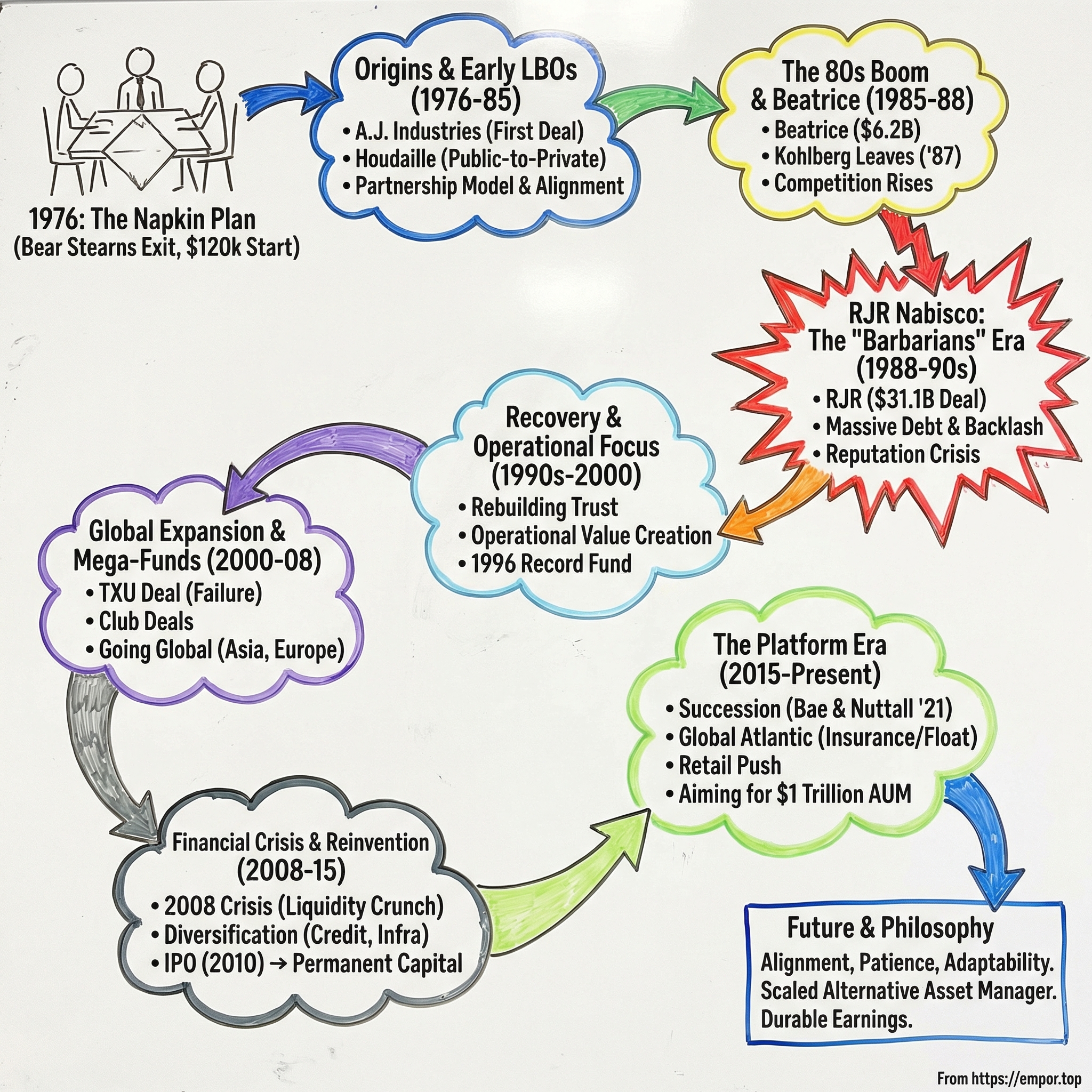

Picture this: three men in rumpled suits, huddled around a table at a Manhattan restaurant in 1976, scribbling numbers onto a cocktail napkin. They’d just walked away from stable jobs at Bear Stearns. No clients. No fund. No back office. No safety net. What they did have was an idea—simple on the surface, revolutionary in practice—that would rewrite corporate finance.

That idea became KKR & Co. By December 31, 2024, KKR had completed 770 private-equity investments representing roughly $790 billion of total enterprise value. The firm managed $553 billion in assets under management, with $446 billion of that fee-paying. The napkin math turned into a blueprint—and then into an industry that now moves trillions of dollars worldwide.

But this isn’t just a story about financial innovation. It’s a story about trust—earned the hard way, damaged in full public view, then rebuilt deal by deal. It’s a story about a partnership powerful enough to build a new asset class, and complicated enough to strain under ambition and pressure. And it’s the story of private equity itself: how it went from villain to institution, from “barbarians” to boardroom partners, from leverage-first to operations-driven.

So here’s the question we’re answering: how did Jerome Kohlberg Jr., Henry Kravis, and George Roberts build the firm that pioneered modern private equity? How did they live through the RJR Nabisco backlash, the early ’90s downturn, and the 2008 financial crisis—and still emerge as one of the world’s biggest alternative asset managers?

We’ll follow three big arcs. First, the invention and evolution of the leveraged buyout. Second, the shift from feared corporate raiders to value-creating partners. And third, KKR’s transformation from a tight-knit buyout shop into a global platform spanning private equity, credit, infrastructure, and more.

Along the way, we’ll get into what makes great dealmaking, why reputation is a form of capital, and what it takes to build an institution that can outlast the people who started it.

This is the story of KKR—and the industry it helped create.

II. Origins: Bear Stearns and the Birth of an Idea (1960s–1976)

Jerome Kohlberg Jr. wasn’t supposed to invent leveraged buyouts. He was supposed to be a lawyer. After graduating from Harvard Law School in 1955, Jerry—as everyone called him—joined a law firm and looked headed for a safe, conventional career advising wealthy clients.

But “safe” never quite fit.

By the early 1960s, Kohlberg had pivoted to Wall Street, landing at Bear Stearns in corporate finance. At the time, Bear wasn’t Goldman or Morgan Stanley. It was a hungry, scrappy shop—exactly the kind of place where an unconventional thinker could try something new without getting suffocated by tradition.

What Kohlberg kept running into, deal after deal, wasn’t just a financing problem. It was a human one: succession. America was full of family-owned businesses built over decades, sometimes generations. The founders were aging out. The kids often didn’t want the job, or couldn’t do it. An IPO was usually unrealistic. Selling to a strategic buyer could mean layoffs, culture shock, and the end of the family legacy.

Kohlberg’s idea was deceptively simple. What if you could buy these companies with mostly borrowed money, keep management in place, and align everyone’s incentives through shared ownership? The business’s own cash flow would pay down the debt. Management would get meaningfully wealthy if they executed. And the investor could earn outsized returns without putting up much equity.

Debt-financed acquisitions weren’t new. What was new was the way Kohlberg shaped the approach into something repeatable—pairing leverage with a partnership mindset, and building the lender and management relationships to make the machine run again and again. Inside Bear Stearns, through the late 1960s and early 1970s, he started doing transactions that would later get a name: leveraged buyouts.

Two younger cousins at Bear noticed what was happening. Henry Kravis joined in 1969. George Roberts followed in 1970. Kravis—educated at Claremont Men’s College and Columbia Business School—was intense, persuasive, and built for closing. Roberts, who attended the same schools but worked out of San Francisco, was the counterweight: calmer, more analytical, always thinking a few moves ahead. Together, they were a match.

Under Kohlberg, the cousins learned the craft: how to pitch founders, how to win management teams, how to talk to the insurance companies and pension funds that could write the big checks. Bear Stearns was content to take the fees. But it didn’t see—or didn’t care—that Kohlberg’s group was quietly assembling something bigger than a series of one-off deals.

And that came down to culture. Bear ran on an “eat what you kill” model: individual producers got paid for their own output, not for building an institution. Collaboration was optional. Long-term investment in a new practice was hard to justify. For Kohlberg, Kravis, and Roberts, it meant their wins flowed to Bear’s bottom line while they captured limited upside. Worse, Bear’s leadership didn’t want to create a dedicated buyout business around what the trio was proving could work.

By 1975, the tension had become impossible to ignore. They had a model. They had momentum. But they didn’t have a home that wanted to nurture it. So in early 1976, they made the leap: they would leave Bear Stearns and build their own firm.

The break wasn’t a screaming match, but it wasn’t warm either. Bear’s leadership was skeptical that three men—no fund, no committed investors, no infrastructure—could turn leveraged buyouts into a real business. The prevailing view was that these were quirky, occasional transactions, not a firm-defining strategy.

KKR began the way so many pivotal businesses begin: with conviction and very little else. On a spring evening in 1976, the three sat at a restaurant table and sketched the plan on a napkin. Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. officially began operating on May 1, 1976.

They didn’t have much capital. Kravis and Roberts each scraped together $10,000—essentially their life savings. Kohlberg, 51 years old and nineteen years older than his partners, was in a different financial position and put in $100,000. Total: $120,000.

They also did the uncomfortable math of survival. To keep the lights on while they built a business, they estimated they needed $500,000 a year for at least five years. Instead of raising a formal fund—something that would have been a stretch for an unproven, three-person spinoff—they engineered a workaround. They went to eight wealthy individuals, many from Kohlberg’s Bear Stearns network, and asked for $50,000 per year for five years. In return, those backers would see every deal and have the right to invest alongside the partners, transaction by transaction.

It was a clever solution to two problems at once. It covered operating expenses without a traditional fund. And it created a tight circle of aligned supporters who were financially and emotionally invested in the firm’s success. Those early backers didn’t just provide money—they helped validate the model and, over time, opened doors to larger pools of capital.

From day one, the partnership also had a clear division of labor. Kohlberg was the senior figure—the credibility, the judgment, the steady hand. Kravis, in New York, became the East Coast spearpoint. Roberts, three thousand miles away in San Francisco, built relationships and sourced opportunities in the West. The bi-coastal setup was unusual for Wall Street, but it gave them reach, speed, and a built-in check against the tunnel vision that can come from a single office.

So that was the starting line: three partners, a napkin plan, and $120,000 of their own money.

Now they needed their first real proof point.

III. Early Years: Building the LBO Playbook (1976–1985)

In the beginning, KKR didn’t feel like a firm so much as a traveling sales pitch.

Kohlberg, Kravis, and Roberts spent their days in conference rooms and factory parking lots, sitting across from founders and executives who’d never heard the phrase “leveraged buyout,” let alone considered one. They knocked on doors and made the same case over and over: to private owners, that KKR could help unlock value without handing the company to a strategic buyer; to public-company boards, that going private could give management room to build for the long term.

Their first buyout came quickly. A.J. Industries—a small industrial conglomerate—became the early proving ground. It wasn’t a headline deal, but it mattered for a different reason: it showed that the team’s approach could stand on its own, outside Bear Stearns’ shadow. KKR could find a deal, finance it, and manage through it as principals.

From there, a pattern started to emerge. KKR gravitated toward businesses with steady cash flow, often in unglamorous corners of the economy—manufacturing, industrial services, consumer products. The structure was the point: use the company’s own cash generation to service the acquisition debt, while giving management a meaningful equity stake. If the company performed, everyone won. If it didn’t, everyone felt it.

That ownership mindset was the real break from the past. Most private investing at the time was passive—buy, hold, collect, and wait. KKR was building something more involved. Henry and George pushed into the details with management teams, questioning plans, tightening capital allocation, and looking for practical operational improvements. They weren’t trying to run the businesses day-to-day, but they also weren’t content to be distant financiers. The pitch was partnership, and they acted like it.

As the early deals stacked up, so did the capital relationships. Insurance companies—always searching for yield—found LBO debt attractive. Pension funds, under pressure to generate returns for millions of retirees, started paying attention to the equity upside. By the late 1970s, KKR had assembled a growing base of institutional support that could back bigger swings.

Then came the deal that put the model on the map.

In 1979, KKR completed the $380 million leveraged buyout of Houdaille Industries. It wasn’t the biggest buyout ever, but it was something new and far more visible: a major public-to-private transaction, taking a New York Stock Exchange-listed company off the market and into private ownership.

That leap raised the stakes. Public companies came with boards, shareholders, disclosure rules, and scrutiny that family businesses didn’t. The Houdaille transaction demanded new legal and financing choreography—and a willingness to fight through skepticism from people who didn’t like the idea of a public company being bought with heavy leverage.

Kohlberg led the negotiations with Houdaille’s leadership and offered something that, for many executives at the time, felt almost unheard of: they wouldn’t be pushed aside. They’d become owners alongside KKR, with real upside tied directly to performance. And without the constant pressure of quarterly expectations, they could manage for a longer horizon.

The deal closed. Houdaille went private. And Wall Street noticed.

From that point on, the Houdaille playbook became KKR’s template. Find durable cash flows and capable management. Use debt efficiently, but not recklessly. Make management owners. Stay engaged. Improve the business. Exit when value had actually been built.

Inside the firm, the economics and structure also began to harden into something repeatable. KKR earned management fees—typically 1 to 2 percent of committed capital—to keep the operation running. The real prize was carried interest: 20 percent of the profits above a hurdle rate. The “2 and 20” model didn’t start with KKR, but KKR helped make it the language the industry would eventually speak.

But the most persuasive piece wasn’t the fee structure. It was alignment. KKR put its own capital into every deal alongside investors. The partners weren’t just collecting checks for deploying other people’s money; they were tying their own net worth to the same outcome. For institutions with long memories and a low tolerance for misaligned incentives, that mattered.

By the mid-1980s, KKR had become the reference point in a fast-growing field. They’d closed dozens of transactions, built a reputation for working with management rather than against it, and proven that leveraged buyouts could be more than opportunistic one-offs. Competitors were showing up—Forstmann Little, Clayton Dubilier & Rice, and others—but KKR set the pace.

What the market was beginning to understand was that KKR hadn’t simply gotten good at transactions. They were systematizing a new model of ownership and governance—one built on concentrated control, aligned incentives, and the freedom to think longer-term than public markets often allowed.

And in the right economic environment, that model was about to explode.

IV. The 1980s Buyout Boom: From Niche to Mainstream (1985–1988)

By the mid-1980s, leveraged buyouts stopped being a weird corner of corporate finance and became the main event. Wall Street didn’t just notice the LBO—Wall Street wanted in.

A few big forces hit at once. Interest rates came down from the brutal highs of the early part of the decade, which made borrowing less punishing. Michael Milken and Drexel Burnham Lambert built the high-yield bond market into a financing engine that could fund acquisitions at a scale traditional banks didn’t want to touch. And just as important: executives were watching peers at buyout-owned companies make real money through equity. Once that idea spreads—that you can be both an operator and an owner—it’s hard to put back in the bottle.

Deal size followed the momentum.

In 1985, KKR bought Beatrice Companies for $6.2 billion, the largest leveraged buyout ever done at the time. Beatrice was a classic 1980s conglomerate: a huge mix of food and consumer brands that had grown fat and unfocused in public markets. KKR’s bet was straightforward: simplify the portfolio, sell what didn’t belong together, and make the remaining businesses run like owners actually cared where the cash went.

Beatrice also marked a shift in how KKR operated. This wasn’t a cozy transaction with a founder looking for succession planning. It was competitive and contested—an acquisition that required beating other bidders and persuading a wary board. In the public eye, Henry Kravis became the face of that new KKR: hard-charging, relentless, and perfectly matched to an era that rewarded aggression.

Inside the partnership, though, the same shift created real strain.

Jerry Kohlberg had always been the most cautious of the three. He preferred smaller deals with willing sellers. He saw buyouts as a partnership with management, not a campaign to win an auction at any cost. As Henry and George pushed into larger, more confrontational territory, Jerry grew increasingly uneasy—not just about risk, but about what the firm was becoming.

In 1987, at age 61, Kohlberg resigned. Publicly, health was part of the story—he had suffered a brain hemorrhage years earlier. But the deeper issue was philosophical. Jerry believed KKR was drifting away from the principles he’d built the model on, and that the chase for ever-bigger deals was turning partnership capitalism into something sharper and less personal.

Henry Kravis became senior partner. In practice, he and George Roberts continued to operate as a two-headed leadership structure: Henry driving from New York, George balancing the machine from San Francisco. Jerry went on to found Kohlberg & Company, deliberately returning to the quieter, relationship-driven style of buyout he’d always favored. The separation stayed civil, but it was still a rupture—one that split the founding team of the entire industry.

And the timing mattered. Because the industry was getting crowded, fast.

Forstmann Little, led by Ted Forstmann, carved out a brand as the principled “white knight” alternative to the harder edge of the market. Blackstone, founded in 1985 by Pete Peterson and Steve Schwarzman, was building its own buyout ambitions. And Drexel’s junk-bond machine kept feeding capital to anyone with the nerve to swing.

With more capital and more competitors, everything ratcheted up. Prices rose as auctions got hotter. Leverage climbed as bidders stretched to win. The old world—where these deals were sourced through relationships and done with a handshake-like tone—gave way to bidding wars, brinkmanship, and late-night renegotiations.

Wall Street itself changed along with it. Banks that once lived off advising on transactions wanted to own the transactions, too. Morgan Stanley, First Boston, Merrill Lynch—everyone launched buyout efforts. The fees were too big, the prestige too intoxicating, and the deal flow too public to ignore.

By 1988, the market had all the ingredients for something massive: cheap-ish money, new financing tools, too many ambitious players, and a growing belief that any company could be bought if you piled on enough debt.

The stage was set for a single transaction that would come to define the era—and, for KKR, would turn everything they’d built into a public spectacle.

V. RJR Nabisco: The Deal That Changed Everything (1988–1989)

In October 1988, Ross Johnson made a move that didn’t just shake up his company—it shook up American business.

Johnson was the president and CEO of RJR Nabisco, a tobacco-and-food giant that owned Winston cigarettes, Oreo cookies, and a deep bench of household brands. He was charismatic, ambitious, and convinced the market didn’t understand what RJR was worth. In his mind, the solution wasn’t to wait for Wall Street to come around. It was to take the company away from Wall Street entirely.

So Johnson proposed a management buyout, partnering with Shearson Lehman Hutton. They announced an offer of $75 per share, pitched as a premium for shareholders and a fresh start for the company. For Johnson and his team, it also promised a life-changing payday—and a chance to run RJR without the glare of quarterly earnings calls.

Henry Kravis saw the announcement and read it differently. KKR had spent years building a relationship with RJR Nabisco. And Johnson had launched the biggest deal on the board with Shearson—without so much as a heads-up to KKR. In Kravis’s world, that wasn’t just competitive. It was personal.

Within days, KKR signaled it was preparing a competing bid. And just like that, the fight was on.

What followed became the most public, most bruising takeover battle of its era. For roughly six weeks, from late October through late November 1988, RJR Nabisco turned into an arena where nearly every major private equity player and Wall Street bank wanted a seat. Forstmann Little jumped in, casting itself as the “friendly” option against KKR’s harder edge. First Boston assembled a group of its own. And the press treated every twist like a sporting event—new bids, new leaks, new drama, day after day.

The numbers climbed fast. The $75 offer didn’t last. KKR came in at $94. Forstmann countered. Johnson raised again. Each round pushed the price higher—and dragged more of the deal’s guts into public view.

And then the story stopped being only about price.

Johnson’s conduct during the process became its own subplot, and eventually the punchline. Stories circulated about extravagant corporate spending: a fleet of company aircraft nicknamed the “RJR Air Force,” lavish entertainment, and buyout plans that would hand management enormous payouts. Whether every detail was fair or not, the narrative hardened: this was 1980s excess, fully weaponized.

By late November, the board gathered to weigh the final choices. Three serious bidders remained: Johnson’s management group with Shearson, Forstmann Little, and KKR. The negotiations stretched deep into the night—advisers shuttling between rooms, figures recalculated, terms adjusted, and tempers tested.

When it ended, KKR won.

KKR’s final offer was $109 per share, valuing RJR Nabisco at $25 billion of equity. Including assumed debt, the transaction totaled $31.1 billion—by far the largest leveraged buyout ever done at the time. The previous record was KKR’s own Beatrice deal, and this was on a completely different scale.

KKR also earned a $75 million fee for the takeover. Henry Kravis landed on magazine covers. The firm had captured what people were already calling the deal of the century.

But the win came with a price tag that didn’t show up on the term sheet.

The sheer size of the transaction—and the fact that it played out under a national spotlight—triggered a backlash. To critics, it looked like a frenzy of leverage, ego, and fees. Journalists, politicians, and regulators dissected the details. The story was no longer just that KKR bought RJR Nabisco. It was what that purchase supposedly said about capitalism.

Then came the hard part: living with the deal.

RJR Nabisco was saddled with roughly $26 billion of debt, and the interest burden devoured cash flow. KKR now had to oversee a sprawling business spanning tobacco and packaged food while managing obligations that left little room for disappointment.

They went to work the only way you can in a situation like that: sell assets, tighten operations, refinance where possible, and keep the whole structure standing long enough to stabilize it. Pieces of the food business were divested to raise cash. Operating changes rolled through the company. For years, KKR was effectively managing a slow-motion balance-sheet rescue.

The ultimate financial result became debated for decades. By KKR standards, the returns were positive but far from spectacular. Some argued the firm barely profited. What wasn’t debatable was the opportunity cost: RJR demanded enormous attention and capital—resources that could have gone into other investments.

But the biggest bill from RJR Nabisco wasn’t financial.

It was reputational.

VI. The "Barbarian" Years: Reputation Crisis and Recovery (1989–2000)

The RJR Nabisco deal didn’t just leave KKR with a mountain of debt to manage. It left them with a nickname.

In 1989, Bryan Burrough and John Helyar published Barbarians at the Gate, a blow-by-blow account of the RJR bidding war—vivid, entertaining, and often unflattering. It became a worldwide bestseller, later adapted into an HBO movie, and it did something no balance sheet ever could: it fused private equity, in the public mind, with greed, excess, and corporate raiding. The “barbarians” label stuck.

For KKR, the damage was immediate. Every meeting with a potential portfolio company turned into a reputational negotiation before it could become a business one. Where KKR once led with strategy and partnership, now they had to lead with reassurance: we’re not here to strip the place down, we’re here to build. Executives who might have taken their call hesitated. Boards that had flirted with going private pulled back.

Then the cycle turned against the whole industry.

The early 1990s recession hit, and leveraged companies—built for steady growth and predictable cash flow—suddenly had to operate in a harsher reality. Deal activity dried up. Several late-1980s buyouts, not just RJR, strained under heavy debt. The LBO model itself became the target, blamed for corporate fragility at exactly the wrong moment.

So KKR went into repair mode.

Throughout the early 1990s, they worked through RJR Nabisco the only way it could be worked through: asset sales, restructuring, and relentless focus on paying down obligations. The food businesses were spun off. The tobacco side was rationalized. In 1994, KKR began reducing its ownership stake, and by 1995 it had divested the remainder—closing out what became one of the most consuming and difficult investments in the firm’s history.

But while RJR demanded the spotlight, KKR was changing in the background.

The firm absorbed the lessons of the 1980s. Henry Kravis, who had been the hard-charging face of the era, became more deliberate about how KKR showed up in public and in boardrooms. The emphasis began to shift away from pure financial engineering and toward operational improvement—helping companies perform better, not just carry more leverage.

You could see it in what they pursued next. Deals became smaller on average and more relationship-driven, closer to the original spirit Jerry Kohlberg had championed. KKR also started investing in real operating capability: people who could work with management teams on performance, not just capital structure.

The comeback wasn’t quick. Reputation doesn’t reset with one good quarter. It gets rebuilt the slow way—one meeting, one deal, one board decision at a time. The partners traveled constantly, speaking with institutional investors, corporate leaders, and the press, making the case that private equity could create value rather than destroy it.

In 1996, they got their proof.

KKR raised a $6 billion private equity fund, a record at the time. For the pension funds, insurance companies, and endowments that wrote those checks, it was a vote that mattered: not just in the returns KKR could generate, but in the franchise itself.

That fund marked the turning point. KKR had made it through the RJR backlash and the early ’90s stress test. The firm was still standing—wiser, more disciplined, and newly focused on earning trust as deliberately as it earned returns.

Because if RJR taught them anything, it was this: in this business, reputation is capital. And once you’ve spent it, the only way to get it back is to earn it—slowly, consistently, and in full view of everyone watching.

VII. The Second Wave: Mega-Funds and Global Expansion (2000–2008)

As the new millennium arrived, private equity slipped into a second boom. The late-’80s trauma felt like old history. Institutions—still nursing scars from the dot-com bust and looking for something that didn’t move in lockstep with public markets—leaned back into alternatives. And with interest rates staying relatively low, leverage started to look like a tool again, not a weapon.

KKR was ready. The 1996 fund had delivered, which mattered for a firm that had spent years rebuilding trust. With that credibility restored, fundraising got easier, checks got bigger, and the deal market came back to life.

The 2000s wave wasn’t just a repeat of the ’80s. It was bigger, more institutional, and increasingly global. By 2006 and 2007, buyouts were swallowing companies that would’ve seemed untouchable a decade earlier—often through consortiums, because even the biggest firms didn’t want to carry the whole load alone.

KKR’s defining swing of that era came in 2007: the buyout of TXU Energy, a roughly $45 billion transaction done with TPG and Goldman Sachs. When it closed, it was the largest leveraged buyout ever completed. TXU wasn’t a simple business. It was a Texas electricity powerhouse with coal-fired plants, natural gas assets, and a retail operation serving millions of customers.

The logic, at the time, sounded clean. If natural gas prices kept rising, coal generation would look more attractive by comparison. Improve the company, reshape it, and eventually bring it back to the market at a higher value.

Instead, the world changed. The shale boom flooded the market with cheap natural gas, hammering coal economics and undermining the very premise of the deal. TXU—renamed Energy Future Holdings—spent years struggling under its debt burden before filing for bankruptcy in 2014. It became one of private equity’s most notorious losses.

Still, TXU didn’t define the whole decade. In many ways, the bigger story was how KKR used the 2000s to become something more than a U.S. buyout partnership.

They expanded across Europe, Asia, and other emerging markets, building local teams that could operate on the ground rather than trying to “fly in” from New York. At the same time, KKR pushed harder into operational value creation. The firm built Capstone, an internal group dedicated to working with portfolio companies on performance—everything from supply chains and sales effectiveness to technology implementation. This was KKR making a statement: the era of relying primarily on financial engineering was over.

The investor base evolved, too. The largest institutions wanted more exposure than a standard fund commitment allowed. Co-investment became a major part of the toolkit—letting sovereign wealth funds, endowments, and pension systems put additional capital to work alongside KKR. It strengthened relationships with the biggest limited partners and gave KKR more firepower when the right deal appeared.

And because deal sizes kept climbing, “club deals” became normal. Multiple private equity firms would team up on a single transaction—sharing risk, pooling equity, and making the impossible doable. KKR sometimes led these groups and sometimes joined as a partner, but the underlying point was the same: private equity had become a scale game.

With scale came a new intensity of competition. Blackstone, led by Steve Schwarzman, was no longer an upstart—it was a peer, and a rival. Apollo, Carlyle, TPG, and others built serious franchises of their own. The industry KKR had helped invent was now crowded with firms that had the capital, talent, and ambition to take any deal to the mat.

If the 1990s were about survival and reputation repair, the 2000s were about building a platform. Private equity was becoming global, institutional, and operationally hands-on. And firms that couldn’t match that breadth—capital, capabilities, and reach—were going to get left behind.

VIII. Financial Crisis and Reinvention (2008–2015)

Then the music stopped.

When the 2008 financial crisis hit, it didn’t just slow private equity down—it attacked the one thing the whole model needed to function: credit. Lending markets froze. Banks pulled back. New deals became almost impossible to finance, and existing portfolio companies—many carrying meaningful leverage—stared straight at refinancing cliffs. For a moment, it wasn’t crazy to ask whether the modern LBO had finally met its match.

KKR got through it better than many expected, but “better” still hurt. A number of investments made at the 2007 peak struggled as the economy tightened. TXU continued to deteriorate. Fundraising got tougher as institutional investors dealt with losses and liquidity pressure of their own.

But the crisis also did something clarifying. It accelerated changes KKR had already started—changes that would end up defining the next chapter of the firm.

Before 2008, KKR had begun pushing beyond classic buyouts. After 2008, that push became a necessity. Credit investing, infrastructure, and real estate weren’t just “adjacent strategies”—they were new engines that could keep capital working across different market environments. If the crisis proved anything, it was that betting the franchise on one cycle-sensitive playbook was a risk KKR didn’t want to keep taking.

That strategic shift showed up most visibly in a decision that would have been unthinkable for the napkin-era partnership: going public.

In March 2010, KKR filed to list its shares on the New York Stock Exchange. Trading began on July 15, 2010. With that, KKR moved from a private partnership to a publicly traded company. Part of the timing was practical—the window was open. But the deeper motivation was structural: a public listing gave KKR permanent capital, a more durable balance sheet, and a currency it could use to build.

It also signaled a change in identity. Henry and George weren’t just running a buyout shop anymore. They were building an alternative asset manager.

That distinction matters. A buyout firm raises a fund, buys companies, sells them, and returns capital. An alternative asset manager builds a broader, more permanent franchise: multiple strategies, multiple products, and recurring fee streams that don’t depend on whether the M&A market is hot this year.

Post-crisis, KKR leaned into that model. The credit platform became a core business, investing up and down the capital structure—from senior loans to mezzanine to distressed situations. Infrastructure grew into its own focus, with investments in long-life assets like utilities and transportation. Real estate developed as a dedicated vertical with specialized teams and its own capital.

At the same time, KKR expanded its capital markets business. KKR Capital Markets didn’t just help finance KKR’s own deals; it increasingly arranged and syndicated financing for others, too. That brought in additional fee income—and just as importantly, it kept the firm close to the pulse of market conditions in real time.

Inside portfolio companies, the operating playbook kept evolving. Leverage alone wasn’t going to carry returns the way it sometimes had in earlier eras. Businesses needed to perform. KKR’s Capstone team grew, and the firm brought in more executives with real industry and operational experience—people who could sit with management and help drive strategy, execution, and improvement.

KKR also began investing more actively in public markets through hedge fund partnerships, applying private-equity-style research to publicly traded companies. The old boundary between “public” and “private” started to soften. The common thread was the same: KKR wanted more ways to deploy capital, in more market conditions, without being captive to the buyout cycle.

By the time the post-crisis era matured, KKR had come out the other side looking meaningfully different. It still did buyouts. But it no longer depended on them. Credit, infrastructure, real estate, and public market strategies broadened the revenue base. The public listing added permanence and resilience. And the firm that had pioneered the leveraged buyout was now building something closer to a financial institution—designed to endure through cycles, not just win them.

IX. The Platform Era: Becoming an Alternative Asset Manager (2015–Present)

By the mid-2010s, Henry Kravis and George Roberts were nearing their eighties. They’d built KKR from a napkin plan into one of the world’s biggest investment firms. But the question that had powered so many early KKR deals—succession—was now staring back at them from inside their own walls.

In 2021, Henry and George handed over their CEO roles, aiming to pass along lessons accumulated over half a century. The message was consistent with how they’d rebuilt KKR after RJR: collaborate, stay entrepreneurial, and never assume the current formula will keep working. Companies have to evolve to survive. Notably, the transition was smooth—an outcome many financial dynasties don’t manage.

Joe Bae and Scott Nuttall stepped in as co-chief executives, taking over a firm already in motion. Bae had built KKR’s Asia private equity business into a major franchise and brought a global lens. Nuttall had helped drive KKR’s expansion into credit and capital markets and understood the power of diversification. Together, they weren’t just caretakers of a legacy—they were positioned to push KKR further into its next identity.

That next identity crystallized around a big idea: insurance.

KKR acquired Global Atlantic Financial Group, which became a wholly owned subsidiary. Global Atlantic, a major annuity and life insurance company, brought something private equity firms always crave: permanent capital. The deal followed a path Apollo had shown with Athene, but this was KKR making its own, very direct bet on the insurance-alternatives model.

The logic was straightforward and powerful. Insurance companies collect premiums and hold capital to pay future claims. In the meantime, that pool can be invested. With Global Atlantic inside the house, KKR could invest that capital across its credit and alternative strategies, aiming to earn investment returns while also generating fee streams. Done well, it becomes a flywheel: performance supports the insurance business, the insurance business grows the capital base, and the bigger capital base fuels more investing.

The scale story kept moving in the same direction. As of the most recent reporting, KKR’s assets under management reached $638 billion, up 15% from the prior year. In 2024, the firm raised $114 billion in new capital and deployed a record $84 billion. It wasn’t just markets lifting valuations; it was new money flowing in, and then getting put to work.

With that momentum, the targets got bigger too. KKR laid out a plan to reach at least $1 trillion of assets under management within five years. It also set a goal of generating annual adjusted net income of more than $15 per share within a decade. For a firm that once measured itself primarily by whether the last deal worked, this was a different language: institution-building, expressed in durable earnings power.

Another shift defined this era: bringing alternatives to individuals.

For most of its history, private equity was an institution-only club—pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth, and the ultra-wealthy. But regulatory changes and product innovation started to open new doors. KKR made private wealth distribution a strategic priority, building teams and channels to work with broker-dealers, wealth managers, and financial advisors. The prize was obvious: the pool of capital held by individuals is vast, and historically underpenetrated by alternative managers.

To operate at that scale, KKR also leaned harder into technology. The firm invested in technology companies, brought technologists into the organization, and modernized how it ran. Data and analytics supported sourcing and portfolio monitoring. Digital tools improved how investors interacted with the firm. The contrast was almost surreal: KKR began as three men and a phone. Now it employed thousands and ran on sophisticated systems designed for a global platform.

And that’s the through-line of the platform era. Institutions that built KKR—pensions and endowments—have real constraints on how much more they can allocate. Individuals don’t, at least not in the same way. If KKR could earn trust there, at scale, the firm’s growth ceiling would look nothing like the one it lived under for the first few decades.

X. Investment Philosophy & Operational Playbook

Walk into any KKR office and ask about alignment, and you’ll hear the same refrain: KKR invests alongside its clients. The firm puts money to work from its own balance sheet, and it won’t ask outside investors to commit to something KKR isn’t willing to back with its own capital. Almost everyone who works at KKR is also a shareholder.

That idea isn’t a modern branding exercise. It’s a through-line from the beginning. Jerry Kohlberg insisted the partners co-invest in their deals. Henry Kravis and George Roberts kept that practice as KKR scaled. Over time it hardened into culture—and into compensation—so that employee outcomes were tied to the same outcomes investors experienced.

But alignment, by itself, doesn’t produce returns. The bigger shift is how KKR’s value-creation model evolved.

Early leveraged buyouts leaned heavily on financial structure. Buy a company, use a lot of debt, let cash flow pay it down, and sell at a higher value. Operational improvement helped, but it wasn’t always the main engine. That formula worked best in eras when debt was cheap and market multiples were rising.

The modern KKR playbook puts operations at the center. The goal is to build a better business—grow revenue, expand margins, improve working capital discipline, and reposition strategically. Leverage can still amplify results, but it can’t replace real improvement. In this model, management teams aren’t passengers. They’re co-pilots.

To make that repeatable, KKR built the ability to assemble and upgrade leadership. The firm maintains relationships with thousands of executives who could run or support portfolio companies. When KKR buys a business, it can help fill leadership gaps, strengthen the board, and add expertise where the current team is thin.

In 2021, KKR became a founding partner of Ownership Works, a nonprofit designed to help companies implement broad-based employee ownership. It took KKR’s alignment principle and pushed it beyond executives and investors to frontline employees, with equity grants tying worker upside to company performance.

ESG moved from something firms claimed to something KKR tried to systematize. Environmental, social, and governance factors were incorporated into due diligence and ongoing portfolio management. Part of the motivation was values-driven, and part of it was practical: businesses that manage these risks well can be stronger operators—and, often, more attractive assets when it’s time to exit.

As KKR accumulated more permanent capital through insurance and longer-duration structures, patience became a weapon. With the ability to hold assets for longer, KKR could justify investments in technology, expansion, and transformation that are harder to make when you’re optimizing for a faster exit.

That longer-term mindset also began to shape how KKR thought about the portfolio. Deals weren’t treated as isolated bets. Portfolio companies could share best practices, learn from one another, and sometimes even do business together—plugging into the broader KKR network.

And if you’re trying to understand KKR as a business—not just as a dealmaker—the metric to watch is fee-related earnings (FRE). FRE captures the recurring earnings power of the platform: management fees, minus what it costs to run the machine, before you count the unpredictable highs and lows of investment performance. When FRE is growing, it’s a signal that KKR’s platform is compounding in a durable way.

XI. Competitive Analysis & Industry Position

In June 2022, KKR reached the top of Private Equity International’s PEI 300 ranking for the first time, knocking Blackstone off the number-one spot as the world’s largest private equity firm. It slid back to second in 2023 and 2024, then reclaimed the top position on the 2025 list. Those flips matter less than what they represent: the modern alternatives business has increasingly been defined by a small set of scaled platforms, and the KKR–Blackstone rivalry sits at the center of it.

The two firms took different routes to the same destination. Blackstone, led by Steve Schwarzman, pushed earlier and harder into real estate and credit, and it went public in 2007—years before KKR—giving it a head start on permanent capital and the ability to use its public currency for strategic growth. Just as importantly, Schwarzman treated brand as a core asset. Blackstone didn’t just build an investment business; it made itself synonymous with alternative assets.

KKR’s edge looks different. Its deep private equity roots still carry weight with sellers and management teams, especially in situations where trust and partnership are part of the underwriting. Its geographic reach is another advantage—particularly in Asia, where Joe Bae built a leading franchise that opened doors many competitors couldn’t. And while plenty of firms talk about “operational value creation,” KKR has spent decades building real capabilities to support portfolio companies, making operations a meaningful differentiator rather than a slogan.

Then there’s Apollo—the third name that consistently shows up in any “Big Three” conversation. Apollo, built under Leon Black and later leadership, leaned heavily into credit and carved out a reputation for thriving in distressed and complex situations. Its merger with Athene became the template for the insurance-and-alternatives model—one KKR later echoed through Global Atlantic.

Beyond those three, the next tier has its own distinct shapes. Carlyle has long been associated with its Washington network and defense expertise. TPG developed a strong position in growth equity and impact investing. And across the industry, what used to be a world of generalist LBO firms has fractured into more specialized strategies, products, and channels—partly by choice, and partly because specialization is how you stand out when everyone has capital.

The hottest battlefield is private credit. After 2008, banks retreated under new regulations and scar tissue. Private credit managers stepped in to fund loans and financings banks no longer wanted to hold. The space has grown rapidly, drawing intense competition from KKR, Blackstone, Apollo, and a long list of other managers all fighting for the same borrowers, terms, and relationships.

So what determines who wins? A few factors keep showing up. Scale, because bigger platforms can pursue larger opportunities, spread fixed costs, and meet the needs of the biggest institutional clients. Diversification, because multi-strategy firms can keep earning fees and deploying capital even when one market slows. Geographic reach, because deal flow is increasingly global. And talent, because in the end, this is still a decision business.

Viewed through that lens, KKR sits in a strong—but not invulnerable—position. Its private equity heritage is an advantage with certain sellers, but it can also box perception in when the firm is trying to be understood as a fully diversified platform. The insurance integration provides a powerful capital base, while also introducing balance-sheet complexity and risk. And its global footprint is real, but every market comes with formidable local competitors who know the terrain just as well.

XII. Bear & Bull Cases for the Future

The bull case for KKR starts with the simplest advantage in asset management: scale tends to compound. As the firm pushes toward—and potentially beyond—$1 trillion in assets under management, it can spread fixed costs across a bigger base, invest more in sourcing and operating capabilities, and show up credibly in the largest, most complex situations. Scale also feeds fee-related earnings, giving KKR more predictable cash flow to keep building the platform. Layer on a global footprint, and KKR can chase opportunities that smaller or regional players can’t reach. Layer on diversification—private equity, credit, infrastructure, real estate, and insurance—and the franchise becomes less dependent on any single market or strategy having a great year.

Private wealth could be the accelerant. For decades, alternatives were mostly an institutions-and-ultra-wealthy game. If KKR can broaden access through wealth managers and advisor channels, the pool of potential capital gets dramatically larger. The firm has already built meaningful distribution here, suggesting execution is real—but it’s still early, and early is where a lot of strategies look good on paper.

Then there’s insurance: a structural advantage that changes the shape of the business. With Global Atlantic, KKR has a source of long-duration, relatively stable capital and a business that can smooth earnings across cycles in a way pure-play asset managers often can’t. As Global Atlantic grows, KKR’s investment capacity grows with it, and the platform collects both investment opportunity and fee income. Done well, it’s a flywheel—one that’s hard for firms without an insurance affiliate to fully replicate.

The leadership transition is another part of the bull story. Handing the CEO reins from founders to a new generation is where plenty of financial firms wobble. So far, KKR hasn’t. Joe Bae and Scott Nuttall have carried forward the culture Henry Kravis and George Roberts built while continuing to push the firm toward a broader, more durable identity.

If you apply Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, KKR checks several boxes that can be genuinely durable. Scale economies show up in the ability to compete for larger transactions and fund the infrastructure required to operate them well. There are real network effects in relationships with management teams, lenders, and limited partners, plus the compounding knowledge that comes from overseeing a huge portfolio over decades. Process power is perhaps the most underrated: KKR’s institutional muscle in sourcing, executing, financing, and improving companies. And brand power, while arguably less consumer-visible than Blackstone’s, still carries real weight with boards, founders, and investment committees who care about certainty of closing and competence under pressure.

The bear case is equally real, and it starts with a basic truth: the industry KKR helped invent is now crowded. Competition has intensified as every major financial institution builds, buys, or partners its way into alternatives. As more capital pours into the same strategies, fee rates and returns both come under pressure. The old playbook of “buy, lever up, and ride multiple expansion” stopped being reliable years ago. The next era depends more on operational improvement—harder to do, harder to standardize, and harder to scale than financial engineering.

Cycle risk never goes away in private markets; it just changes forms. Private equity tends to work best when credit is available and exits are open. A prolonged credit contraction, or a sustained downturn in equity markets, would slow new deal activity and stress parts of the existing portfolio—especially businesses that need refinancing at the wrong time. KKR doesn’t need another TXU to be reminded that even elite firms can be right on the spreadsheet and wrong about the world.

Regulation is the ever-present overhang. Private equity’s fees, disclosures, and portfolio company practices regularly attract political scrutiny. The tax treatment of carried interest could change, directly hitting economics. ESG-related rules and expectations could also constrain strategy choices or add compliance friction—regardless of where you stand on the merits.

Fee pressure, meanwhile, is structural. The largest institutions increasingly demand better terms as a condition of big commitments. The classic “2 and 20” economics have already softened for many large accounts, and further compression would pressure margins even if headline assets keep growing.

Succession, too, isn’t a box you check once. While the transition to Bae and Nuttall has gone smoothly, Henry and George remain involved as executive chairmen. The final test comes when the founders are no longer part of the firm’s day-to-day identity at all.

And there’s a valuation risk that hangs over the entire alternatives industry: future returns may have been pulled forward. As capital has flooded into private markets, purchase prices have risen, and private equity entry multiples can at times exceed public market equivalents. If the “private premium” has shrunk or disappeared, then sustaining historical outperformance becomes harder.

You can map much of this onto Porter’s Five Forces and get a picture that’s mixed at best. Rivalry is intense and rising. The threat of new entrants is real, especially as sovereign wealth funds and large institutions build in-house capabilities. Substitutes are growing as public markets, venture, and other strategies compete for allocation. Sellers have options in competitive auctions. And while capital is abundant—reducing supplier power—abundant capital is exactly what compresses returns.

So what should you watch? One important signal is whether growth in assets translates into durable earnings power. And the other is more fundamental: can KKR keep deploying capital at a healthy pace while maintaining return on invested capital? If deployment rises but returns fade, scale becomes a headline rather than an advantage. If KKR can do both—put money to work and still create value—then the bull case starts looking less like a narrative and more like a machine.

XIII. Lessons & Legacy

What KKR taught the world about private equity goes well beyond clever financing. The firm showed that private ownership—when it’s built on aligned incentives and a longer time horizon—can produce outcomes public markets often struggle to support. Free from the churn of quarterly expectations, companies can make investments that take years to pay off. Managers with real equity don’t just “run the plan”; they think like owners. And investors willing to lock up capital can earn returns that reflect that patience.

You can trace a meaningful portion of modern corporate finance and governance back to the model KKR helped popularize. Leveraged buyouts imposed discipline on sprawling, unfocused conglomerates. Equity-based incentive structures—once novel—became standard operating procedure across both private and public companies. Even the possibility of an LBO changed behavior: it made it harder for managers to hide behind complacent boards and underperforming balance sheets, and it pushed directors to take shareholder value more seriously.

KKR has also tried to tell a broader story about what all of this is for. The firm’s stated belief is that capitalism can bring prosperity to companies and people, and that business can be a force for good. Whatever you think of the industry’s critics and defenders, the historical point is clear: KKR helped pioneer the buyout fund model—what we now call private equity—and those early principles, first articulated by Jerry Kohlberg and carried forward by the firm’s later leadership, became the scaffolding for an industry that today manages trillions of dollars.

If you boil the KKR playbook down into lessons, three keep showing up.

First: alignment. Make sure the people making the decisions win and lose alongside the capital providers—not just through slogans, but through actual ownership and incentives.

Second: patience. Private equity works best when it’s not pretending to be fast money. The real value comes from holding long enough to improve the business, not just the balance sheet.

Third: adaptability. KKR survived because it kept evolving—out of the 1980s reputation crater, through the early ’90s recession, through the 2008 crisis, and into a world where credit, insurance, infrastructure, and technology matter as much as traditional buyouts.

That evolution is still underway. The lines between public and private, between equity and credit, and between investing and operating keep blurring. The firm that began with three men and a napkin now runs a global platform across multiple strategies and hundreds of billions of dollars.

And the legacy isn’t finished. Henry Kravis and George Roberts, now in their eighties, handed operational control to a new generation. The institution they built faces a different set of risks and opportunities than the ones that shaped its early decades. But the core ideas they embedded—alignment, operational focus, and long-term thinking—remain the foundation for whatever KKR becomes next.

XIV. Recent News

KKR’s most recent chapter reads like a firm leaning into the thing it has spent two decades building: a platform that can keep moving even when one part of the market slows. In late 2024 and early 2025, it completed several significant transactions, putting money to work from its latest flagship fund. Infrastructure stayed active as KKR positioned around the energy transition and the buildout of digital infrastructure. And in credit, the engine kept running, with strong origination as traditional lenders continued to pull back from certain parts of the market.

On the capital-raising side, momentum held. KKR attracted new commitments across multiple strategies, reflecting the advantage of being able to offer investors more than just buyouts. The private wealth push also continued to build, with new distribution partnerships and growing allocations from individual investors. Meanwhile, Global Atlantic kept expanding its insurance business, writing new policies that added to the pool of long-duration capital KKR can invest.

In recent investor presentations, management reiterated the same north star it has been pointing toward: reaching $1 trillion of assets under management, and delivering on the earnings objectives they’ve laid out. The message wasn’t about one blockbuster deal. It was about the durability of fee-related earnings—and the flexibility that comes from having multiple ways to deploy capital across cycles.

Their market view has been consistent, too: they’ve highlighted opportunity in private credit, infrastructure, and Asia, while acknowledging that competition is intense across the alternatives landscape. The posture is confident but measured—emphasizing discipline on entry price and deal structure, and avoiding the kind of “growth at any cost” mentality that has burned even the best firms in past cycles.

XV. Links & Resources

Primary Sources: - KKR & Co. Inc. annual reports and SEC filings (10-K and 10-Q, available at sec.gov) - KKR investor presentations and earnings call transcripts - Private Equity International’s PEI 300 rankings (2022–2025 editions)

Books: - Barbarians at the Gate by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar (1989) — the definitive account of the RJR Nabisco takeover - King of Capital by David Carey and John Morris — a comprehensive history of private equity and KKR’s role in shaping it - The New Tycoons by Jason Kelly — a look at the modern private equity industry and the firms that built it

Industry Research: - Preqin private equity reports - Bain & Company Global Private Equity Report - McKinsey Global Private Markets Review

Historical Archives: - Bear Stearns corporate histories - SEC filings tied to key transactions (RJR Nabisco, Beatrice, Houdaille, TXU)

Academic Research: - Harvard Business School case studies on KKR transactions - Journal of Financial Economics research on leveraged buyout returns

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music