Kroger: From Corner Store to Grocery Giant

I. Introduction & Cold Open

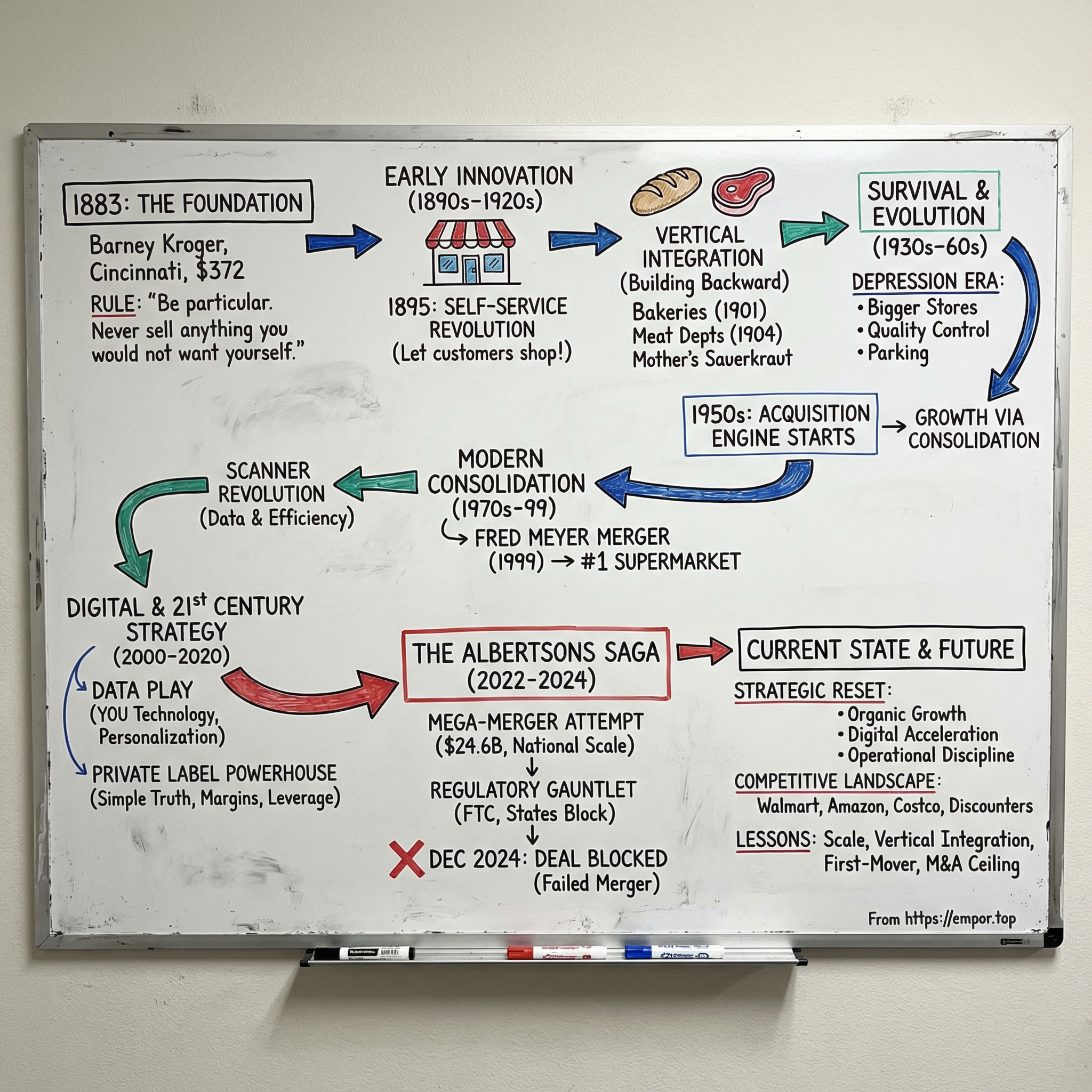

In 1883, a twenty-three-year-old son of German immigrants stood on Pearl Street in downtown Cincinnati and counted out $372—every dollar he had. Barney Kroger didn’t have a business degree. He didn’t have wealthy backers. He didn’t have a family fortune to cushion a bad month. What he did have was a rule, sharpened by years of scraping by: "Be particular. Never sell anything you would not want yourself."

That one line—simple, stubborn, and intensely practical—became the operating system for a company that would help define American grocery retail. Today, Kroger runs 2,719 stores across 35 states, employs about 430,000 people, and brings in roughly $150 billion a year. It’s the largest pure-play supermarket chain in the United States: a survivor of the Great Depression, a builder through the suburban boom, and a heavyweight that learned to compete in the age of Walmart and Amazon.

But this isn’t just a story about getting big. It’s a story about how you win in a business where the economics are brutal—where margins are thin, customers are fickle, and the only way to stay alive is to keep getting better. Kroger became a master of vertical integration, an early adopter of new retail formats, and, more recently, a case study in how far consolidation can go before regulators slam on the brakes. From pioneering self-service shopping in 1895 to the failed $24.6 billion Albertsons merger in 2024, Kroger’s history is basically a guided tour through the fight to feed America at scale.

This is the story of how a German immigrant’s son built a grocery empire—one hard-earned lesson and one innovation at a time—and what that journey says about the future of food retail in the United States.

II. The Barney Kroger Story & Founding Context

A Boy's Education in Hardship

Bernard Henry Kroger was born on January 24, 1860, in Cincinnati, Ohio—the fifth of ten children of Johan Heinrich Kroger and Mary Gertrude Kroger. His father had come from Westphalia, his mother from Oldenburg, part of the wave of German immigration that made Cincinnati so heavily German it earned the nickname “Over-the-Rhine.”

The family ran a small dry goods store and made a modest living—until the Panic of 1873. The crash kicked off the deepest depression the young country had ever seen, and it wiped out small businesses by the thousands. Johan Kroger’s shop didn’t make it. Barney was thirteen, old enough to understand what it meant when the doors closed: no income, no safety net, no time for school.

So he quit. Not as a dramatic choice, but as the only available one. He took work on a nearby farm for room and board and 25 cents a day. It was hard, monotonous labor, and the kind that doesn’t care how old you are. A year later, at fourteen, he got malaria—common in the river valleys then—and suddenly he couldn’t even do that.

The 37-Mile Walk

When the farm let him go, Barney had no paycheck, no strength, and no plan—except to get back to Cincinnati. So he walked the 37 miles, sick and broke, putting one foot in front of the other until the city finally came into view.

It’s the kind of story companies love to tell later, and for good reason: it captures the trait that would define Kroger from the start. In grocery, you don’t get rescued. You endure. You figure it out.

Back in Cincinnati, he recovered and went to work at the Imperial Tea Company, then later the Great Northern and Pacific Tea Company. These were early chain retailers, the training grounds for modern American merchandising. Kroger learned the trade the unglamorous way: by selling, stocking, buying, tracking what moved, and discovering just how thin the line is between profit and failure.

By his early twenties, he’d saved enough to take a swing at ownership.

He teamed up with a fellow grocer, B.A. Branagan, and together they scraped together $722—$350 from Kroger and $372 from Branagan. In 1883, they opened a small grocery at 66 Pearl Street in downtown Cincinnati.

Building the Foundation

The partnership didn’t last long, but it did its job. Within a year, Kroger bought out Branagan and began running the business on the principles he’d earned the hard way.

His stores were going to be clean. They were going to be orderly. They were going to sell solid goods at fair prices. And they were going to stand behind a simple promise: he wouldn’t sell anything he wouldn’t want in his own home.

That wasn’t just a nice line. It was a differentiator. In an era when adulterated food was common—when flour could be cut with sawdust and milk chalked to look richer—quality was a competitive strategy. Customers noticed. Trust spreads fast when it’s rare.

By 1885, just two years after that first opening, he was already operating four stores. The corner grocery was turning into something bigger: a repeatable model.

Personal Tragedy and Professional Triumph

Then came the kind of blow that doesn’t show up on growth charts. In 1899, Barney’s wife, Mary, and their oldest son died of diphtheria. It was a brutal, common killer at the time, especially among children. Kroger remarried in 1900, to Alice C. Saunders, but the loss didn’t just vanish because life kept moving.

And life did keep moving—fast. The business expanded. The scale increased. Kroger pushed harder. By 1900, the chain had grown to 40 stores. By 1910, it would be nearing 100.

Kroger’s origin story isn’t a tale of genius arriving fully formed. It’s a story of pressure: poverty, sickness, and grief, all funneling into an obsession with doing the basics better than anyone else. Quality. Value. Discipline. In a business where margins are thin and mistakes are expensive, that mindset wasn’t branding. It was survival—and it became Kroger’s permanent operating system.

III. Early Innovation & Vertical Integration (1890s-1920s)

The Self-Service Revolution

Picture the typical American grocery store in the 1890s. A clerk stands behind a counter. Customers line up and recite a list. Every item—flour, sugar, coffee—has to be fetched from shelves the shopper can’t touch. If you want to compare options or prices, you don’t browse. You ask.

Barney Kroger looked at that setup and saw a bottleneck. In 1895, he tried something that, at the time, felt almost backwards: he let customers into the store to shop for themselves. Prices were marked. Goods were within reach. Shoppers could move through the aisles, choose what they wanted, and bring it to the register.

Today, that’s just called “a grocery store.” Back then, it was a structural change to the business. Self-service meant fewer hands needed per sale, faster throughput, and more impulse buying because the products weren’t hidden behind a counter. It also shifted power toward the customer: they could see, compare, and decide.

Kroger wasn’t alone in the broader movement—Piggly Wiggly would later popularize self-service in 1916—but he was early enough that you can see a pattern forming. Over and over, Kroger would make bets on new retail mechanics before they were widely proven.

Building Backward: The Vertical Integration Strategy

By the early 1900s, Kroger’s chain had grown large enough to run into a new problem: dependence. Every supplier decision—price hikes, inconsistent quality, delayed deliveries—landed on Kroger’s balance sheet and, worse, on Kroger’s reputation. He had built trust with customers by being “particular,” but he didn’t fully control what he was selling.

So he started building backward into production.

In 1901, Kroger became the first grocer in the country to establish its own bakeries. That wasn’t a cute side project; it was a strategic lever. Owning the baking meant better control over freshness and consistency, fewer middlemen taking margin, and a product—bread—that pulled customers back in regularly.

Then in 1904, Kroger went further, acquiring Nagel Meat Markets and creating what’s credited as the first in-store meat departments in grocery retail. At the time, food shopping was fragmented: bakery here, butcher there, grocer somewhere else. Kroger pushed toward a one-stop shop, where a household could handle the weekly run in one place.

Mother’s Kitchen: The Sauerkraut Story

And sometimes “vertical integration” wasn’t a boardroom concept. It was family.

Cincinnati’s German-American community knew what good sauerkraut was supposed to taste like, and the commercial versions often didn’t measure up. Kroger began making sauerkraut using his mother’s recipe, producing it himself and selling it through his stores.

It’s a small story, but it reveals the bigger one. Kroger had a repeatable insight: if you could make a staple product yourself—better, more reliably, and at a lower cost—you could protect the brand promise and improve the economics at the same time.

Over the decades, that instinct expanded dramatically. Kroger would grow into a company with dozens of manufacturing plants producing everything from dairy to pet food. But the strategic logic stayed the same: in a low-margin business, controlling more of the chain can be the difference between surviving and getting squeezed.

The Explosive Growth Years

With self-service improving store efficiency and vertical integration strengthening margins and quality control, Kroger’s growth accelerated. By 1920, the company was no longer just a Cincinnati story. It was spreading through the region, expanding into broader Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky markets.

The 1920s were rocket fuel for chain retail: rising incomes, swelling cities, and the automobile changing how people shopped. Kroger leaned in. By 1929, the company reached a peak of 5,575 stores.

That number sounds surreal today, but these weren’t modern supermarkets. They were small neighborhood groceries—often under 2,000 square feet—packed densely into communities. Individually, they were modest. Together, they created scale that few retailers in America could match.

The Founder’s Exit

In 1928, as his health declined, Barney Kroger stepped away. He sold his shares for $28 million and retired at 68, leaving behind the company he’d spent nearly half a century building.

He died in 1938 at age 78. By then, Kroger had already become bigger than its founder: a public corporation with professional management and institutional momentum.

The pre-1930 Kroger playbook is striking in its clarity—innovate the format, control the supply chain, expand relentlessly. It built a foundation strong enough to create a national giant. Now it faced the real test: whether those advantages could hold when the Great Depression arrived and the entire economy turned against retailers.

IV. Depression Era to Post-War Evolution (1930s-1960s)

Surviving the Unthinkable

The stock market crashed in October 1929 almost perfectly on cue with Kroger hitting its all-time high-water mark in store count. Then the floor fell out of the economy. Over the next few years, unemployment surged, consumers stopped spending, and retailers across the country disappeared.

Kroger made it through—but it didn’t glide through. The company pulled back hard, shutting down large numbers of small neighborhood locations that couldn’t generate enough volume to justify their rent, inventory, and labor. That peak of 5,575 stores was gone for good. In its place, Kroger began shifting toward a new idea: fewer stores, but bigger ones. The supermarket era was starting to take shape.

The Depression also forced Kroger to professionalize something Barney Kroger had built more on instinct: trust. In the 1930s, Kroger became the first grocery chain to systematically monitor product quality and test foods before they hit the shelves. This wasn’t a warm-and-fuzzy initiative. It was a defensive move in a world where customers couldn’t afford to take chances. One bad purchase wasn’t just a complaint—it was a lost household.

And then there was a retail innovation that sounds almost boring until you realize what it signaled: parking on all four sides. As more Americans relied on cars, the store stopped being a place you walked to and started being a place you drove to. Designing around that shift—easy access, easy loading, space to move—gave Kroger a quiet but real edge as shopping habits changed.

The Billion-Dollar Milestone

When World War II ended, the country didn’t just recover—it surged. Suburbs spread. Families bought cars. Weekly grocery runs became bigger, more routine, and more centralized. The supermarket model—large footprint, wide aisles, full self-service, huge assortment—became the default.

Kroger was built for that world. In 1952, the company crossed a symbolic line: more than $1 billion in annual sales. Less than seventy years after Barney Kroger put $372 into a single store, Kroger had become a true national-scale retailer—no longer a collection of neighborhood shops, but a machine.

The Acquisition Engine Starts

By the mid-1950s, Kroger’s leadership made a decision that would shape the next half-century: growth wouldn’t come primarily one new store at a time. It would come by buying other chains.

Starting in 1955, acquisitions became the accelerant. Instead of slowly building presence market by market, Kroger could purchase a regional player and instantly inherit its stores, customers, and local know-how—then plug that network into Kroger’s larger purchasing and distribution system.

The 1963 acquisition of Market Basket, a 56-store chain in California, showed the logic. One deal, and Kroger had a foothold in the biggest state in the country. It was the start of a pattern Kroger would repeat again and again: find a strong regional operator, buy it, integrate it, and try to win on scale.

But the story also came with a warning label. The California push didn’t ultimately stick. Kroger exited the state by 1982, an early reminder that grocery is brutally local. Scale helps, but it doesn’t erase differences in real estate costs, competition, supply chains, and shopper behavior. Sometimes the right strategic move is retreat.

Diversification Experiments

Kroger was also testing what else could live under the same roof—or at least under the same corporate umbrella. In 1961, it opened its first SupeRx drugstore in Milford, Ohio. Pharmacy brought higher margins than groceries and a powerful behavioral hook: people come back regularly for prescriptions, and when they do, they tend to buy a few staples too.

That instinct—to pair grocery with adjacent, stickier categories—would only grow more important as food retail stayed a low-margin grind. Kroger’s modern footprint includes 2,254 pharmacies, a reminder that the company’s definition of “the grocery business” expanded long ago.

The arc from the Depression through the 1960s is where Kroger starts to look like the Kroger we recognize today. It proved it could endure a full economic collapse, then capitalize on a historic boom. It moved from tiny storefront density to bigger formats built for cars. And it discovered a scalable growth engine in acquisitions—while learning, sometimes painfully, that even giants can’t win everywhere.

V. The Modern Consolidation Era (1970s-1999)

The Scanner Revolution

The 1970s opened with an operational breakthrough that sounds mundane now, but at the time was a seismic shift. Kroger became the first grocer to test electronic scanners. Barcode tech didn’t just speed up checkout; it rewired how a grocery business ran.

Before scanners, stores lived in a fog. Inventory was managed by intuition and aisle-walking. Prices changed slowly because every item needed a sticker. Cashiers keyed in numbers by hand. Mistakes were common, lines were long, and managers didn’t really know—day to day—what was selling and what was quietly expiring on the shelf.

Scanning flipped that. Suddenly, checkout was faster and cleaner. Prices could update centrally. And most importantly, the system generated a new asset: data. Not anecdotes, not hunches—actual, item-by-item purchase behavior. Kroger leaned into that shift early, formalizing consumer research so it could study buying patterns, tune assortments, and refine store operations. Long before “analytics” became a buzzword, Kroger was building the muscle to run grocery like an information business.

Second Largest in America

By 1979, that mix—operational discipline, steady growth, and a willingness to buy rather than slowly build—pushed Kroger into rarefied air. It became the second-largest supermarket chain in the United States, behind only Safeway.

For a company that started as a single storefront in Cincinnati, it was a stunning marker of how far the model had traveled. But grocery doesn’t hand out trophies for second place. The next chapter was about one thing: getting bigger, faster, and smarter—because in a thin-margin industry, scale isn’t a flex. It’s oxygen.

The Dillon Deal

In 1983, Kroger made a move that changed its shape. It merged with Dillon Companies, a western operator with strong regional banners: King Soopers in Colorado, Fry’s Food Stores in Arizona, City Market in mountain communities, and Gerbes in Missouri.

The deal didn’t just add stores; it expanded Kroger’s map and its playbook. Kroger could now call itself a coast-to-coast operator for the first time, with meaningful presence well beyond its Midwestern roots.

It also reinforced an approach Kroger would keep using: don’t bulldoze what’s working. The Dillon banners had local loyalty, supplier relationships, and market knowledge that couldn’t be replicated from Cincinnati. Kroger’s move was to keep the names customers trusted, while integrating the machinery behind the scenes—purchasing, distribution, and back-office operations—where the scale advantages lived.

Fighting Off the Raiders

Then came the late-1980s leveraged buyout wave, when American companies started getting treated like financial puzzles to be rearranged. In 1988, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts—KKR, fresh off the RJR Nabisco takeover—targeted Kroger.

KKR saw a retailer with assets to monetize and costs to cut. Kroger’s management saw something else: a business that could not afford to be strapped to a mountain of debt. In grocery, cash flow is steady but margins are thin, and too much leverage can quickly force ugly decisions—store closures, layoffs, underinvestment—just to keep up with interest payments.

So Kroger fought back with a defensive recapitalization: effectively leveraging itself to buy back shares and make a hostile takeover uneconomical. KKR backed off. Kroger stayed independent.

But the escape came with a price. The company emerged with heavy debt, which limited flexibility for years. Kroger learned an expensive lesson that would linger in the company’s DNA: leverage can protect you in the short term, and still haunt you later.

The Fred Meyer Mega-Merger

By the late 1990s, consolidation in grocery wasn’t optional. Regional chains were being snapped up, and the biggest players were building purchasing and distribution advantages that smaller competitors couldn’t match. In 1999, Kroger made its boldest bet yet: a $13 billion merger with Fred Meyer.

Fred Meyer wasn’t just another supermarket chain. It was a Pacific Northwest retail powerhouse and a pioneer of the hypermarket concept in the U.S.—huge stores that blended groceries with general merchandise, plus pharmacy, jewelry, and home goods. Fred Meyer’s boxes averaged over 150,000 square feet, a different species from the traditional supermarket. The company also brought additional banners, including QFC (Quality Food Centers), a premium grocer, and Smith’s Food & Drug, a major Southwest operator.

The merger vaulted Kroger past Safeway to become the largest supermarket operator in the United States—a position it has held ever since. It also broadened Kroger’s competitive toolkit. With more exposure to general merchandise and larger formats, Kroger was better positioned for the next threat on the horizon: Walmart’s expanding grocery ambitions.

For Kroger, the Fred Meyer deal captured the double-edged nature of transformational M&A. The upside was immediate: scale, geography, and new formats overnight. The downside was real too: integration complexity and years of management attention absorbed by the work of making two large organizations function as one. Kroger pulled it off—but not for free.

By the time the 1990s ended, Kroger’s modern strategy had snapped into focus: use consolidation to build scale, keep strong local brands, centralize the invisible plumbing, and be willing to walk away from markets where you can’t win. That discipline—grow where you have an edge, retreat where you don’t—set Kroger up for the twenty-first century, when the competition stopped being just other grocers and started becoming the largest retailers and tech companies in the world.

VI. Digital Revolution & 21st Century Strategy (2000-2020)

The Acquisition Drumbeat Continues

The calendar flipped to 2000, but Kroger’s instincts didn’t change. In a business where scale buys you better prices, better logistics, and more room to invest, the fastest way to grow was still the same: buy density.

Between 2001 and 2015, Kroger kept absorbing regional chains, one after another—each one bringing not just stores, but local customer loyalty and a foothold in markets that would take years to build from scratch.

A clean example is Harris Teeter. In 2014, Kroger bought the Charlotte, North Carolina-based grocer for $2.5 billion. Harris Teeter ran 227 stores across eight states and leaned upscale—exactly the kind of banner that could pull in affluent suburban shoppers and complement Kroger’s broader, mass-market base. The deal pushed Kroger deeper into the Southeast and added a higher-end format to the portfolio.

Then came Roundy’s in 2015, which brought Pick ’n Save, Metro Markets, and Mariano’s into the fold. That mattered because it strengthened Kroger in and around Chicago and reinforced the same M&A playbook Kroger had been refining for decades: keep the names customers already trust, but fold everything behind the curtain—purchasing, distribution, systems—into Kroger’s larger machine.

The Data Play

But the bigger shift in this era wasn’t on the map. It was in the data.

In 2014, Kroger acquired YOU Technology, a platform built around digital coupons and personalization. This wasn’t a “nice to have” add-on. It was a signal that Kroger saw the next battleground clearly: knowing customers better than anyone else, and turning that knowledge into loyalty and margin.

With YOU Technology, Kroger gained tools that used artificial intelligence to predict preferences and tailor offers. And those tools landed on top of an unusually rich foundation—decades of scanner data, plus information from tens of millions of loyal households. For a grocery chain, that combination is powerful: you can’t win every price war, but you can get better at offering the right deal to the right shopper at the right time.

That same year, Kroger also merged with Vitacost.com, an online retailer focused on natural and organic products. The point wasn’t simply to tack on e-commerce sales. It was to get ahead of a fast-growing, health-conscious segment—before Amazon and Whole Foods could own the narrative.

The Private Label Powerhouse

If data was Kroger’s digital advantage, private label was its structural one.

By the 2010s, roughly 40% of the products in Kroger stores came from its own manufacturing operations. That’s vertical integration at a level few major competitors could match, and it turned the store shelf into something more than a place to resell national brands.

Kroger ran private label as a ladder. There were budget “Value” products for price-sensitive shoppers, mainstream “Kroger” branded staples meant to go head-to-head with national brands, and premium lines like “Private Selection” and “Simple Truth” for customers who wanted better ingredients and were willing to pay for them. Simple Truth, in particular, became a monster in the organic category, generating billions in annual sales and ranking among the largest organic food brands in the U.S.

Strategically, private label did three things at once. It improved margins. It differentiated Kroger—because you couldn’t buy those products at Walmart or Amazon. And it gave Kroger leverage with suppliers: when negotiations got tense, national brands knew Kroger had credible alternatives ready to slide into their shelf space.

Building the Modern Infrastructure

All of that—digital offers, premium brands, bigger baskets—only works if the plumbing holds.

Behind the scenes, Kroger kept investing in the hard, unglamorous infrastructure that turns a grocery chain into a system. By 2020, it operated 33 manufacturing plants producing categories like dairy, bakery, grocery, and pet food. Its distribution network fed stores across 35 states. And fuel became a surprisingly important part of the flywheel: by 2024, Kroger had 1,642 fuel centers, pulling customers onto the property for gas and often converting those stops into grocery trips.

Pharmacy scaled the same way. With 2,254 in-store pharmacies, Kroger became one of the biggest pharmacy operators in the country. Prescriptions drive repeat visits; repeat visits drive the rest of the basket. In a low-margin business, that kind of built-in frequency is gold.

The Omnichannel Imperative

Then the threat profile changed. Grocery wasn’t just competing against other grocers anymore. Amazon was coming.

As Amazon’s ambitions sharpened—especially after its 2017 acquisition of Whole Foods—Kroger pushed harder into digital. Pickup expanded, letting customers order online and collect without walking the aisles. Delivery partnerships with Instacart and others extended Kroger’s reach to shoppers who might never set foot in a store. And ship-to-home filled the gaps for specialty products.

By the end of the 2010s, Kroger had built a true omnichannel model: stores, pickup, delivery, and direct shipping, all running in parallel. The open question wasn’t whether customers wanted these options—they did. It was whether the economics would work at scale, and whether Kroger could move fast enough to keep Amazon from redefining the category.

By 2020, Kroger’s modern shape was clear: massive purchasing power, deep private label and manufacturing capabilities, and a growing digital stack built on data. But scale has limits—especially when the next big move depends on regulators saying yes. That’s exactly what the Albertsons saga would expose.

VII. The Albertsons Mega-Merger Saga (2022-2024)

The Biggest Deal That Never Was

On October 14, 2022, Kroger announced what would’ve been the largest supermarket merger in American history: a $24.6 billion acquisition of Albertsons Companies. If it had gone through, the combined business would have looked less like a grocery chain and more like national infrastructure—nearly 5,000 stores, roughly 710,000 employees, and revenues nearing $200 billion.

From Kroger’s perspective, the logic was straightforward. It had spent decades stitching together regional champions, but there were still gaps on the map. Albertsons brought exactly the missing pieces: Safeway across the West, Jewel-Osco in Chicago, Acme in the Northeast, and Shaw’s in New England. Put the two together and you’d get something Kroger had chased for a century: a truly national footprint with enough scale to go toe-to-toe with Walmart’s grocery dominance.

But the moment the deal hit daylight, so did the blowback. Consumer advocates warned that fewer competitors would mean higher prices—especially painful in an inflationary moment when food budgets were already stretched. Union leaders pointed to history: consolidation often ends with store closures and jobs lost. And state attorneys general began circling, asking a simple question with a complicated answer: in their state, in their cities, on their blocks—would this merger leave shoppers with fewer real choices?

The Regulatory Gauntlet

If Kroger wanted a temperature check on the era it was operating in, it picked the clearest possible one: the Federal Trade Commission under Chair Lina Khan. Khan’s FTC had been explicit about taking a harder line on horizontal mergers—direct competitors combining in ways that could reduce competition. Kroger and Albertsons weren’t adjacent businesses. They were the same business, often across the street from each other.

To blunt that concern, Kroger and Albertsons offered a remedy: they would divest more than 400 stores to C&S Wholesale Grocers, a large distributor that would step into retail and, in theory, preserve competition in markets where the combined company would be too dominant.

Regulators didn’t buy it. The FTC argued C&S didn’t have the track record to successfully run hundreds of stores, and that grocery divestitures had a history of looking good on paper and breaking down in practice. Meanwhile, state attorneys general—California, Colorado, Washington, and others—filed their own lawsuits to block the merger, adding another set of battlefields and another layer of risk.

December 2024: The Death Knell

By December 2024, the deal was no longer being fought in press releases. It was being fought in courtrooms. And on December 10, 2024, the merger suffered twin blows: judges in two separate courts ruled against it. A federal court blocked the deal on antitrust grounds, concluding it would likely harm competition and raise consumer prices. A Washington State court blocked it as well, citing similar concerns.

At that point, there were only two paths: keep fighting through appeals, or call it. After more than two years of negotiations, litigation, and limbo, Kroger and Albertsons ended the attempt.

Aftermath and Recrimination

What came next looked less like two companies parting ways and more like a breakup with lawyers. Albertsons expected a $600 million termination fee if the deal collapsed due to regulatory opposition. Kroger disputed that, arguing Albertsons hadn’t sufficiently supported the push to win approval. Lawsuits followed, with each side blaming the other for why the merger died.

Under the legal fighting was something more revealing: the cost of being stuck in merger purgatory. Albertsons had spent heavily preparing for a combined future, and for two years its stock traded in the shadow of merger math. When the deal fell apart, the shares dropped sharply—and the company was forced back into the market as a standalone operator, facing renewed scrutiny about what its next chapter looked like without a buyer.

Kroger didn’t come out unscathed either. It had poured management focus, time, and legal resources into a transaction that ultimately delivered no new stores, no new markets, and no new capabilities—just bills and a couple of years where “what happens if the deal closes?” competed with the day job of running a sprawling grocery empire.

What the Failed Merger Reveals

For anyone watching the industry, the collapse clarified a few things fast.

First: regulatory risk for horizontal mergers had meaningfully changed. Deals that might have been negotiated into approval in an earlier era now faced an FTC willing to litigate and a coalition of states willing to pile on.

Second: divestitures were no longer the get-out-of-jail-free card they’d been in past grocery mergers. Regulators weren’t just asking, “Are you selling stores?” They were asking, “Will the buyer actually be a durable competitor?”—and they were increasingly skeptical.

Third: grocery consolidation may have hit a hard ceiling. Kroger was already the largest supermarket operator in the country, and the broader food market was dominated by Walmart. Trying to merge two of the biggest remaining traditional grocers looked, to regulators, less like efficiency and more like a step toward reduced competition.

And most importantly for Kroger, the failed deal forced a strategic reset. If transformational M&A was going to be blocked, then what was the next growth engine? More organic gains in existing markets? New formats? Even heavier investment in digital and technology?

Whatever the answer was, it wouldn’t come from buying Albertsons. Kroger was going to have to earn it the old-fashioned way.

VIII. Current State & Competitive Position

The 2024 Financial Picture

Even after the Albertsons deal collapsed, Kroger didn’t suddenly become small. In fiscal 2024, it generated about $150 billion in revenue—enough to make it the largest supermarket operator in the United States by store count, and the second-largest food retailer overall, behind only Walmart.

It employed roughly 430,000 people across 2,719 stores in 35 states, with its strongest positions concentrated in the Midwest, the South, and the Mountain West. Kroger is still, at its core, what it’s always been: a scale business that shows up week after week in millions of households’ routines.

And the digital side—once the big question mark for every legacy grocer—kept moving in the right direction. In the fourth quarter of 2024, digital sales grew 11%, a sign that pickup and delivery weren’t just pandemic-era conveniences anymore. Kroger’s omnichannel model had real momentum, even as the entire industry adjusted to the post-COVID “new normal.”

The Competitive Landscape

To understand Kroger’s current position, you have to understand what it’s up against—because grocery isn’t a market with one enemy. It’s a market with five.

Walmart is the gravity well. Its grocery operation is massive, and its purchasing power, logistics, and technology budget are on a different plane. When Walmart leans into price, it drags the whole market down with it—and Kroger has to decide how much margin it’s willing to give up to keep customers from drifting.

Amazon is the shape-shifter. It’s not just Whole Foods; it’s Amazon Fresh, it’s logistics, it’s Prime, it’s the ability to trade profit today for position tomorrow. Amazon doesn’t have to “win grocery” all at once to be disruptive. It just has to keep getting better at convenience until weekly shopping habits start to change.

Costco comes at the same household wallet from a different angle: bulk, value, and a membership model that makes customers feel committed. Even if a Costco isn’t on the same corner as a Kroger, it can still siphon off a meaningful share of a family’s grocery spend—especially for staples.

Then there are the discounters. Aldi and Lidl don’t win with variety; they win with simplicity and price. Limited assortment, heavy private label, lean staffing, and relentless efficiency—exactly the kind of model that pressures everyone else’s pricing, whether they want to match it or not.

Geographic Strengths and Gaps

Kroger’s map tells the story of a company built through a century of expansion—and selective retreat.

It’s dominant in its traditional Midwestern base, including Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Michigan. It’s also strong in the Mountain West through banners like King Soopers, Fry’s, and Smith’s. And the Harris Teeter acquisition gave it a meaningful presence in parts of the Southeast, adding exposure to faster-growing metro areas.

But the gaps are just as important. Kroger has little presence in the Northeast, where regional operators and long-entrenched competitors still hold the ground. California—the biggest state in the country—remains largely off the board after Kroger’s exit by 1982. And Florida, despite its size and growth, is still an underdeveloped market for the company.

Those holes matter. They limit how much Kroger can look like a truly national chain, and they cap some of the leverage that comes with being everywhere when negotiating with large suppliers. The Albertsons merger would have filled in many of those blanks. Its failure left Kroger with the same strategic reality it had before the deal: huge scale, but not a complete national footprint.

Labor Relations and Workforce Dynamics

Kroger also competes with a structural difference that shapes everything from costs to culture: it has a heavily unionized workforce. The United Food and Commercial Workers represents a significant portion of Kroger employees, and contract negotiations can become flashpoints.

That relationship cuts both ways. On one hand, labor is a major cost in a business where margins are already thin, and union contracts can reduce flexibility compared to non-union competitors like Walmart. On the other hand, longer tenure and more stable staffing can translate into better operations—less churn, less constant retraining, and, ideally, better service in the aisles.

Zooming out, Kroger’s position is both strong and exposed. It’s big enough to be a national force, but it’s surrounded. Walmart attacks with price and scale. Amazon attacks with convenience and technology. Discounters attack with value. And local competitors attack with market-by-market knowledge. Staying on top doesn’t come from one big move anymore. It comes from constant investment, tight execution, and winning a thousand small decisions, every day, across thousands of stores.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Vertical Integration as Competitive Advantage

Kroger’s most distinctive asset isn’t a flashy app or a single blockbuster acquisition. It’s the unglamorous stuff: control.

Over time, Kroger built a vertically integrated engine—manufacturing plants producing private label goods, in-house bakery operations that trace back to 1901, and meat capabilities that reach all the way back to Barney Kroger’s early push into in-store departments. The point of all that backward integration is simple: in grocery, the money is made in the seams.

When Kroger manufactures products itself, it keeps margin that would otherwise go to suppliers. It can enforce consistency and quality in a way a pure reseller can’t. And it can build real differentiation—Simple Truth, Kroger-brand staples, Private Selection—products customers can only get by choosing Kroger.

The broader lesson travels well: in a thin-margin business, owning adjacent parts of the value chain can be the difference between durable profitability and constant vulnerability.

First-Mover Advantage in Retail Innovation

Kroger has a long history of spotting mechanics that change retail and leaning in early—self-service in 1895, scanners in the 1970s, digital personalization in the 2010s.

The barcode era is a perfect example of why that matters. Scanning wasn’t just about faster checkout. It created a new kind of asset: clean, item-level data on what customers actually bought. That data then fed Kroger’s next wave—loyalty programs, targeted offers, and the personalization tools it gained through the YOU Technology acquisition.

This is what retail first-mover advantage looks like in the real world. It’s not one big breakthrough. It’s a series of early bets that stack on top of each other, compounding into capabilities that are hard to recreate later.

Of course, moving early means accepting that not every experiment pays off. But the companies that wait for proof give up something just as valuable: the learning curve.

Geographic Expansion and Strategic Retreat

Kroger’s history is a reminder that expansion isn’t the same thing as progress.

The company pushed aggressively into new markets over the decades—but it also proved willing to retreat when the economics didn’t work. The cleanest example is California: despite entering through the Market Basket acquisition in 1963, Kroger ultimately exited the state by 1982.

That kind of discipline is rarer than it sounds. Many businesses treat retreat as failure and keep throwing resources at bad positions because they’ve already spent so much to get there. Kroger’s willingness to walk away—prioritizing returns over ego and sunk costs—helped it survive long enough to win elsewhere.

For investors, it’s a useful filter: when a market isn’t working, does management double down and hope? Or do they redeploy capital to where they have an edge? Kroger often chose the second path—though the Albertsons saga is a reminder that even disciplined companies can get overconfident when the prize is big enough.

M&A as Primary Growth Strategy

From 1955 onward, Kroger used acquisitions as its main growth accelerant. Deals like Fred Meyer and Harris Teeter didn’t just add stores—they added ready-made customer bases, local expertise, and market presence that would have taken years to build organically.

But the Albertsons failure exposed the ceiling on that approach. In concentrated industries, horizontal mergers face heavier scrutiny. Remedies that once smoothed approvals—like divesting stores—no longer automatically satisfy regulators. And for the largest players, there’s a simple reality: eventually, you can’t buy your way to the next level without tripping antitrust wires.

That leaves Kroger at a strategic inflection point. If transformational M&A is effectively off the table, growth has to come the hard way: gaining share in existing markets, improving formats, expanding digital commerce, and pushing further into adjacent categories. None of those are as fast—or as clean—as buying a competitor.

Private Label as Margin Driver

Private label is one of Kroger’s quiet superpowers. With around 40% of products sold coming from its own brands, Kroger isn’t just stocking shelves—it’s competing directly with national manufacturers for consumer preference and for shelf space. That shifts bargaining power toward the retailer, where it rarely sits in grocery.

It also creates something grocery usually lacks: stickiness. If a household is loyal to Simple Truth or Private Selection, switching to Walmart or Amazon isn’t frictionless—they’d be giving up products they can’t get anywhere else. In a category where shopping is often interchangeable, that’s a real advantage.

For investors, private label penetration is a useful signal. It usually means the retailer has invested in product development, quality control, and brand building—not just buying inventory and reselling it. In other words, they’re not merely operating stores. They’re building a portfolio.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case for Kroger

Kroger’s biggest advantage is still the oldest one in retail: scale. When you buy for thousands of stores, you get terms that smaller chains simply can’t. Sitting across from suppliers like Procter & Gamble or Coca-Cola, Kroger isn’t negotiating for a handful of locations. It’s negotiating for an entire national footprint. That leverage can show up in lower shelf prices, better promotions, or a little more margin to reinvest back into the business.

Kroger’s omnichannel setup is also a real strategic asset. The stores aren’t just places to shop; they double as the distribution network for pickup and delivery. That gives Kroger something pure e-commerce players spend years and billions trying to build: proximity. And unlike old-school grocers that stayed analog for too long, Kroger has put real muscle behind digital capabilities so customers can shop in the way that fits their lives—aisles, curbside, or delivery. It’s not glamorous, but it’s hard to replicate at scale.

Then there’s private label—one of Kroger’s quiet power moves. Simple Truth has become one of the largest organic brands in the country, and Kroger’s premium lines give it a way to win customers who might otherwise drift toward Whole Foods or other specialty players. More importantly, private label tends to carry better economics than reselling national brands. In a business where pennies matter, that margin cushion creates options: sharpen prices, fund technology, or absorb shocks when costs rise.

Finally, Kroger’s strength in key regions gives it defensible ground. In much of the Midwest, the Mountain West, and parts of the South, Kroger isn’t just “a store.” It’s the default. Habits form around the local banner, distribution routes get optimized over decades, and competitors can’t just drop in without spending heavily to match price, convenience, and consistency. Grocery is local—and in the markets where Kroger is strongest, it’s deeply local.

The Bear Case for Kroger

The first problem is that Kroger’s toughest competitor isn’t another grocery chain. It’s Walmart. Walmart’s grocery business is bigger, and its cost structure is hard to match. If Walmart decides to get aggressive—trading margin for share—Kroger gets pulled into a fight where the bigger player can usually last longer. In grocery, that’s not just uncomfortable. It can be dangerous.

The second problem is Amazon, because the threat is less predictable. Amazon has shown, repeatedly, that it’s willing to run businesses at razor-thin margins while it builds a position. Its logistics network, capital base, and technology stack are in a different league than traditional grocers. If Amazon ever finds a version of grocery that truly works at scale on its terms, it could reshape shopping behavior the way it reshaped books and general merchandise.

The failed Albertsons deal adds another weight: fewer obvious growth levers. For decades, Kroger’s fastest path forward was consolidation. If transformational M&A is effectively blocked, the company has to do it the hard way—win share store by store, market by market, against sophisticated competitors. That’s possible, but it’s slower, messier, and offers less “step-change” upside.

Labor costs are another persistent pressure point. Kroger’s workforce is heavily unionized, and contracts typically lock in wage increases. On top of that, rising minimum wages in many states push costs higher. Labor is the biggest expense line in grocery, and when it rises in a business with thin margins, there isn’t much room for error.

And then there’s the treadmill of technology. E-commerce, personalization, self-checkout, automated warehouses—none of it is optional anymore, and the list keeps getting longer. Kroger has to keep spending to stay competitive, even as it competes with companies like Walmart and Amazon that can fund massive tech budgets from much larger cash engines.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: Moderate. Big consumer brands have leverage, but Kroger’s scale and credible private label alternatives prevent suppliers from fully dictating terms.

Buyer Power: High. Switching is easy, and shoppers compare prices constantly. Grocery loyalty is real in habit, but fragile under pressure.

Threat of New Entrants: Low to moderate. Building a grocery network is capital-intensive, but well-funded players can still push in if they’re willing to lose money long enough.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate. Restaurants, meal kits, and convenience food all compete for the same “what’s for dinner” decision, especially for younger consumers.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. Kroger faces pressure from Walmart, Amazon, Costco, discounters, and strong regional chains. The category is defined by frequent price and promotion battles.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Strong. Kroger’s purchasing, manufacturing, and distribution create real per-unit advantages.

Network Effects: Weak. Grocery doesn’t naturally compound value with more users the way software platforms do. Customer data helps, but it’s not a classic network effect.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate. Kroger’s physical network and manufacturing base would take enormous time and capital for a digital-first competitor to replicate.

Switching Costs: Low. Consumers can shift baskets quickly. Loyalty programs add some friction, but not much.

Branding: Moderate. Kroger’s regional banners matter in their markets, and private label creates differentiation, but grocery brands don’t usually command the kind of pricing power seen in categories like luxury or consumer tech.

Cornered Resource: Limited. Kroger benefits from good locations and infrastructure, but it doesn’t control unique assets that competitors categorically can’t access.

Process Power: Moderate to strong. The know-how embedded in Kroger’s manufacturing, private label development, and operational systems is difficult to copy quickly.

Put together, the picture is clear: Kroger’s advantages are real—especially scale and operational process—but they aren’t unbreakable. With low switching costs and relentless competition, Kroger doesn’t get to win once. It has to keep winning, every week, aisle by aisle.

XI. Power & Strategy Analysis

The Scale Economy Question

Kroger’s most cited advantage is scale: thousands of stores throwing off enough volume to negotiate hard with suppliers, run a massive distribution network efficiently, and spread fixed costs—technology, systems, analytics—across millions of weekly transactions.

That advantage is real. In grocery, scale is often the difference between earning a thin profit and earning no profit.

But it also has a ceiling. Once you’re already one of the biggest buyers in the country, each additional turn of the crank delivers less. Kroger is likely already close to the “best available” supplier terms a traditional grocer can get. Adding more stores wouldn’t magically unlock a whole new tier of discounts. The Albertsons deal would have made Kroger larger, but the incremental purchasing benefit was probably smaller than the headline suggested.

And then there’s the inconvenient truth: scale only wins if you’re the biggest player in the fight that matters. Kroger is bigger than most regional grocers. But Walmart is bigger than Kroger. In the most important mainstream battle—winning the weekly basket of the average American household—Kroger is often defending against a competitor with even more leverage, and an even larger budget to invest in price, logistics, and technology.

Data and Personalization

If scale is Kroger’s old-school advantage, data is the newer one. Kroger tracks purchasing behavior across about 60 million households and uses that history to power personalized offers and recommendations. This is the modern version of being “particular”: not just selling quality goods, but getting smarter about which household wants which deal, and when.

The moat here is time. Decades of scanner adoption and loyalty program history created a dataset that can’t be spun up overnight.

But it’s not a set-it-and-forget-it advantage. Data only stays valuable if you keep investing—better models, better tools, better execution in the app and at checkout. And the competition isn’t standing still. Amazon’s view of consumer behavior is different from Kroger’s, but it’s vast in its own right. Personalization in retail doesn’t crown a winner. It creates a permanent arms race.

Loyalty and Switching Costs

Grocery has a brutal truth baked into it: switching is easy. If the parking lot is crowded, if the produce looks tired, or if prices feel off, customers can change stores next week with almost no friction.

Kroger’s answer has been to manufacture a little friction—especially through fuel rewards. Shoppers earn points on groceries and redeem them at Kroger’s fuel centers. It’s a clever linkage: turn the weekly grocery run into savings on a cost people feel constantly.

It does create stickiness. But it’s not a deep lock-in. Competitors have their own loyalty hooks, including fuel programs. These switching costs are real, just shallow—helpful at the margin, not a guarantee.

Counter-Positioning Against E-Commerce

Kroger’s physical footprint is also a form of defense—what strategy people call counter-positioning. Thousands of stores, manufacturing plants, and distribution assets represent a level of infrastructure that a pure e-commerce competitor would have to spend years and enormous capital to replicate. Even Amazon, with all its resources, has found that grocery is hard to scale profitably in the real world.

But there’s a mirror image to that advantage: those same assets can slow you down. Kroger can’t simply pivot away from stores the way a digital-native company can change a product roadmap. The company has to keep its stores staffed, supplied, and modernized while also building pickup, delivery, and personalization on top. The physical network is both shield and weight.

The Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to know whether Kroger is actually winning—not just existing—two indicators tell you most of what matters:

Identical Store Sales Growth: Often called same-store sales or comps, this measures how stores that have been open for at least a year are performing. It filters out the noise of new openings and acquisitions and answers the key question: are Kroger’s existing stores getting stronger, or are they leaking share?

Digital Sales Growth: Grocery’s future is hybrid. Pickup and delivery aren’t side channels anymore; they’re part of the default expectation. Kroger’s 11% digital growth in Q4 2024 showed the engine was still moving forward. Going forward, this metric is the tell for whether Kroger’s omnichannel model is holding up as competition intensifies.

Together, these two numbers act like a dashboard. Identical sales tell you whether the core business is healthy. Digital growth tells you whether Kroger is building relevance for the next version of grocery. In this industry, you need both—because you don’t get to choose between the present and the future.

XII. Epilogue & Recent News

Life After Albertsons

When the merger collapsed in December 2024, Kroger had to snap back to a reality it hadn’t been planning for. For more than two years, so much of the narrative—internally and externally—had been built around what the combined Kroger-Albertsons would look like. Suddenly, the message had to change: this was still Kroger’s story, on Kroger’s terms.

Management pointed to the same levers it had been pulling all along: keep investing in digital, keep expanding and improving private label, and keep squeezing more efficiency out of a massive, complex store and supply network.

The legal fight didn’t disappear, though. The termination fee dispute with Albertsons threatened to drag on, absorbing attention and resources and keeping the failed deal in the headlines. But the core business kept moving. No matter what happened in court, Kroger still opened its doors every morning and fed millions of households—because in grocery, the week doesn’t pause for strategy resets.

Leadership and Governance

At the center of the post-merger chapter was Rodney McMullen, Kroger’s chairman and CEO. His story is almost too on-brand: he joined Kroger as a part-time clerk in 1978 and climbed through the organization over decades. It’s the clearest embodiment of Kroger’s promotion-from-within culture—and also a reminder of what the company values most: operational fluency, discipline, and a long memory for what does and doesn’t work in the aisles.

Now the job was harder in a different way. Without Albertsons, there was no step-change growth button to press. Kroger had to earn its progress through execution—improving the business it already had, rather than buying the one it wanted.

In that environment, governance matters more than usual. With strategic options constrained, the board’s oversight around capital allocation and realism—what’s worth funding, what’s not, and what tradeoffs are unavoidable—becomes a competitive variable of its own.

Digital Acceleration

In the wake of the failed merger, Kroger doubled down on a simple premise: the future customer expects flexibility. Pickup and delivery continued to expand. Third-party partnerships extended reach. And behind the scenes, Kroger kept investing in automation and operational improvements designed to make digital orders less expensive—and less painful—to fulfill.

But grocery tech is a treadmill, not a finish line. Kroger could spend heavily and still lose if the execution didn’t hold up at the point of truth: when a customer places an order, expects it to be right, and decides whether to do it again. In digital grocery, the margin for error is thin, and the penalty is immediate—because switching stores is always just one more tap away.

Looking Forward

Kroger entered 2026 as what it has been for decades: America’s largest supermarket operator—profitable, scaled, and constantly under pressure from competitors with different advantages and, in some cases, deeper pockets.

The contrast is staggering. Barney Kroger started with $372 in 1883. The company that grew out of that first storefront became a $150 billion enterprise employing hundreds of thousands of people. And yet the strategic problem looks familiar: how do you keep winning in a business that gives you so little room for mistakes?

Organic growth is tough in mature markets. Transformational M&A now comes with a regulatory wall. Amazon keeps raising the bar on convenience. Labor costs rise. Margins stay thin.

What Kroger still has is what it started with: a culture built around operational discipline, vertical integration, and a particular obsession with the customer experience—plus the accumulated learning of more than a century of adaptation. Whether that’s enough for the next chapter won’t be decided by one heroic move. It’ll be decided the way grocery always decides: week by week, store by store, trip by trip.

The grocery business has never been easy. Barney Kroger knew it when he opened on Pearl Street. His successors know it now. The question is whether they can match his mix of innovation and perseverance in an industry that remains, as it always has been, brutally demanding of anyone who wants to feed America.

XIII. Links & References

Primary Sources

- Kroger Company annual reports and SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q)

- Federal Trade Commission v. Kroger Company court filings

- Washington State v. Kroger Company court filings

Historical Sources

- Kroger Company corporate history archives

- Cincinnati Historical Society collections

- The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America by Marc Levinson

- Harvard Business School case studies on grocery retail consolidation

Recent Coverage

- Financial Times reporting on the Albertsons merger proceedings

- Wall Street Journal reporting on grocery industry consolidation

- Bloomberg analysis of Kroger’s competitive positioning

- Progressive Grocer industry coverage and analysis

Industry Analysis

- Food Marketing Institute annual reports

- USDA Economic Research Service research on grocery retail and food markets

- Nielsen/IRI analysis of grocery scanner data

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music