Cheniere Energy: From Import Dreams to Export Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

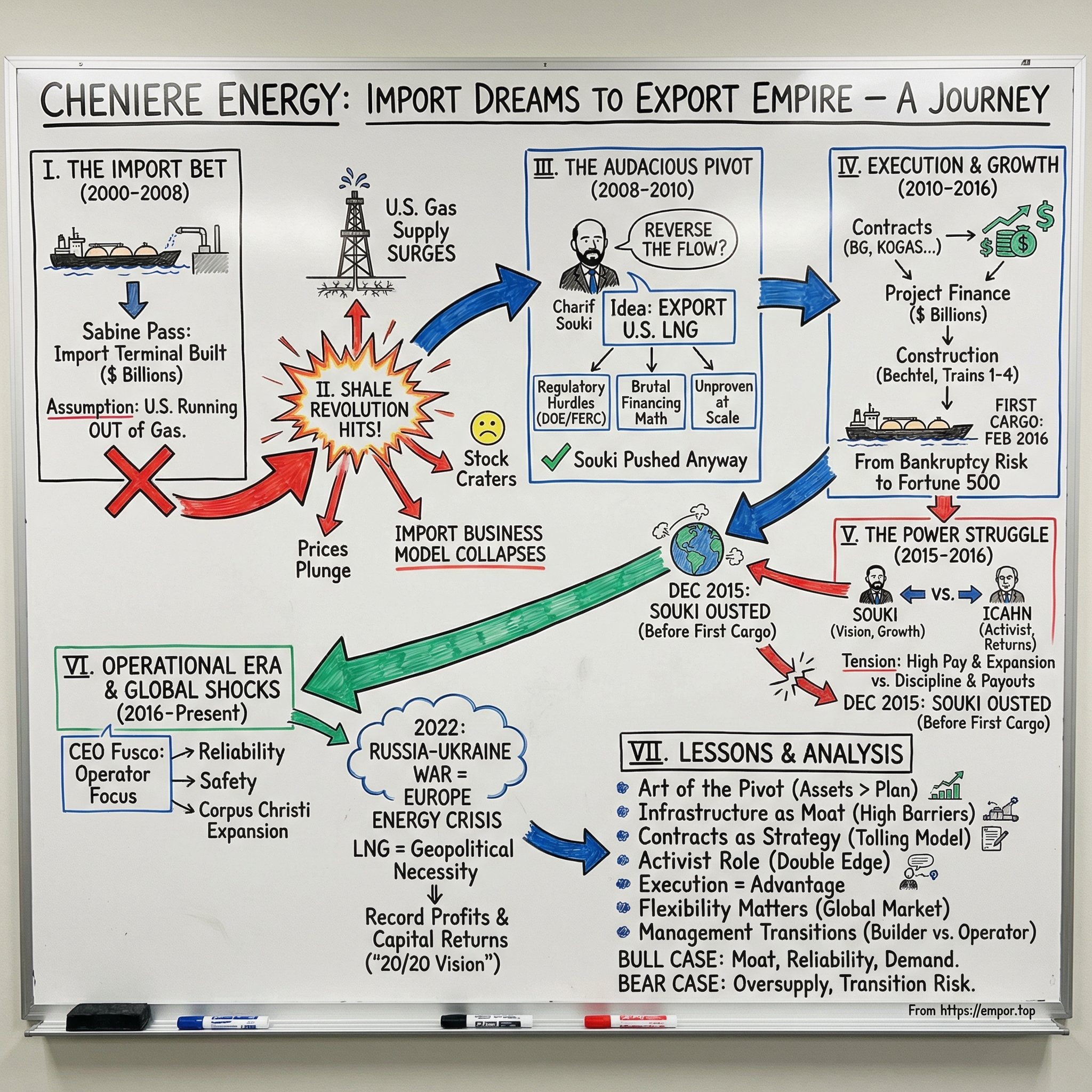

Picture a conference room in Houston, sometime around 2008. Charif Souki is across the table from bankers and board members, trying to defend a multibillion-dollar bet that just went sideways. Cheniere Energy had spent years—and hundreds of millions—building a massive terminal at Sabine Pass designed to receive liquefied natural gas from overseas. The logic had seemed airtight: America was running out of natural gas, the world had plenty, and whoever owned the import gates would print money.

Then the shale revolution hit.

Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling unlocked huge new supplies of U.S. natural gas. Overnight, the story flipped. America wasn’t running out of gas—it was swimming in it. Prices fell. LNG imports dried up. And Cheniere’s gleaming import terminal started to look like a monument to the last decade’s conventional wisdom. Investors bailed. The stock cratered. The obituaries practically wrote themselves.

What happened next doesn’t follow the usual script of corporate collapse. Souki didn’t shut the project down or sell it for scraps. He made a move that, at the time, sounded almost ridiculous: he would reverse the flow. The terminal built to receive LNG would be converted to liquefy U.S. natural gas and export it to the world. The regulatory pathway was murky. The financing math was brutal. And essentially nobody had proven you could do U.S. LNG exports at scale from the lower 48.

Souki pushed anyway—and convinced just enough counterparties, regulators, lenders, and board members to push with him.

Today, Cheniere is the largest exporter of LNG in the United States and the second-largest LNG producer globally. The company that once looked headed for bankruptcy is now a Fortune 500 heavyweight with a market cap approaching $50 billion. Since its first cargo shipped in February 2016, Cheniere has sent nearly 4,000 cargoes to roughly 40 countries.

This is a story about big bets and brutal timing. It’s about an unlikely protagonist—a Lebanese-born former investment banker who built trendy restaurants before building energy infrastructure—and about a pivot that rewired the global gas trade. It’s also about power: who gets to control a company when the stakes are enormous, the cap table is complicated, and activist investors smell blood. Souki would become the highest-paid CEO in America, then get pushed out by Carl Icahn just months before the first exports vindicated the entire strategy.

Here’s how we’ll tell it. We’ll start with Souki: Beirut to Wall Street to Aspen to Houston, and the strange corporate shell that became Cheniere. Then we’ll follow the early years as a struggling oil-and-gas explorer, and the pivot into LNG imports that seemed perfectly timed—until it wasn’t. We’ll walk through the near-death moment when shale made the import business obsolete, and how Cheniere fought its way into becoming America’s first major LNG exporter. Then the drama peaks: Icahn arrives, the boardroom fractures, and Souki loses the company he created. After that, we’ll look at how Cheniere evolved from a builder into an operator, and how global shocks—including Europe’s energy crisis—turned LNG from a niche fuel into a geopolitical necessity. Finally, we’ll pull it all together with what this saga means for investors watching the next chapter of global LNG.

The broader backdrop matters. Cheniere’s rise is inseparable from the shale boom—an industry-wide regime change that upended assumptions across energy. Their advantage wasn’t just having a vision; it was having the nerve, and the timing, to abandon the old one fast enough.

And there’s a warning embedded in the success. Souki saw the turn before almost anyone—and still lost control of the company before his bet fully paid off. His later venture, Tellurian, would fail catastrophically. In energy, genius and hubris can look identical right up until the market decides which one you were.

This is a story about seeing around corners—and what happens when someone else decides you don’t get to be there when the view finally opens.

II. Origins & The Souki Vision (1996–2005)

Charif Souki was born in Cairo in 1953 to a Greek Orthodox family. When he was four, they moved to Beirut, where his father, Samyr Souki, worked as a businessman. In Souki’s early childhood, Lebanon was still sold as the “Paris of the Middle East”: cosmopolitan, affluent, and plugged into Europe. By the time he reached adulthood, the country was sliding into civil war. Like many in his generation, he left.

He landed in the United States and found his way to Wall Street as an investment banker. It was a perfect training ground for what he would later attempt at Cheniere: complicated structures, big capital, high-stakes persuasion. But banking didn’t scratch the itch to build something of his own. So in the late 1980s, he swerved hard into a completely different world: restaurants.

In 1987, Souki invested in the Mezzaluna restaurant chain and opened a location in Aspen, Colorado. The timing couldn’t have been better. Aspen was turning into a magnet for celebrities, financiers, and newly wealthy dealmakers, and Mezzaluna became the kind of place people went to be seen. Souki expanded to Los Angeles, opening three outlets, including a fashionable spot in Brentwood that catered to the upscale yuppie scene of the early 1990s. He seemed to have a real feel for the business: the pacing, the atmosphere, the subtle art of making rich customers feel like regulars.

Then the downsides of hospitality caught up. The restaurant business is unforgiving, and Souki grew disillusioned. Negative publicity hit too, including the Brentwood location’s connection to the O.J. Simpson case—Ron Goldman had worked there. Souki sold the Aspen location in 1993 and, by 1997, had closed the Los Angeles operations. Once again, he was looking for his next act.

Energy came through one of the strangest origin stories in corporate America. The shell that would become Cheniere started life as All American Burger, Inc., incorporated in 1983. By the mid-1990s, it had cycled through multiple identities, including a stint as a Hollywood film colorization company during the brief fad of adding color to classic black-and-white movies. Souki didn’t fall in love with the business. He fell in love with the vehicle: a public-company shell that could be pointed at something far bigger.

In 1996, Souki and his backers transformed that obscure entity into Cheniere Energy, Inc., originally positioned as an oil-and-gas exploration company. The plan was straightforward: go find hydrocarbons along the Louisiana Gulf Coast. He had blue-chip connections from his banking years that helped him raise money. But wildcatting has a way of humiliating ambition. Cheniere drilled and came up empty. By the late 1990s, it was losing money, producing little, and had no convincing path forward.

This is where Souki’s nontraditional background mattered. A career oil-and-gas executive might have doubled down and kept drilling, waiting for the one well that changed everything. Souki had already reinvented himself more than once. Instead of trying harder at the same game, he went looking for a different one. And what he found was LNG.

Liquefied natural gas is natural gas chilled to around minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, cold enough to turn it into a liquid and shrink it to roughly 1/600th of its gaseous volume. That’s the trick that makes intercontinental shipping possible: you can load vast amounts onto specialized tankers and move it across oceans. For decades, LNG had flowed from gas-rich countries to gas-hungry ones, powering places like Japan, South Korea, and parts of Europe.

In the early 2000s, a powerful consensus took hold in the United States: America was running out of natural gas. Domestic production appeared to have peaked, demand was rising, and gas was increasingly important for electricity generation as utilities moved away from coal. The conclusion felt obvious: the U.S. would need to import LNG at scale.

Souki saw the opening immediately. If LNG imports were the future, then the choke point wasn’t the gas itself—it was the gates. Someone would need to build the import terminals: the regasification facilities that could take super-cold LNG, warm it back into a gas, and push it into the pipeline system. These projects would cost billions, take years, and require a regulatory gauntlet. But if you built one, you didn’t just own a facility. You owned essential infrastructure.

So in the early 2000s, Cheniere pivoted away from exploration. Souki announced plans for a massive LNG regasification terminal at Sabine Pass, Louisiana, on the Gulf Coast. In March 2005, construction began. The facility was designed to process 4 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day—enough to serve millions of homes.

For a company of Cheniere’s size, this was audacious. Sabine Pass was the kind of project usually associated with the supermajors or large utilities, not a former wildcatter with little to show for its drilling years. Souki’s job was to convince everyone—investors, lenders, regulators, and would-be customers—that Cheniere could execute a multibillion-dollar infrastructure build. He did it with relentless salesmanship and an almost evangelical belief that he was building what America would soon depend on.

And he had to learn an entirely new business along the way. LNG isn’t just “natural gas, but colder.” It’s its own ecosystem: exotic engineering to handle cryogenic temperatures, specialized shipping, and commercial contracts that often run for decades with take-or-pay commitments. Souki immersed himself. He hired the experts, studied how the global LNG trade worked, visited terminals in Japan and Europe, and built relationships with major LNG players like Qatar, Australia, and Indonesia. What he came to appreciate—deeply—was that once LNG infrastructure is operating, it can throw off stable, predictable cash flows. The challenge is surviving the years of construction, uncertainty, and capital pressure it takes to get there.

The market was willing to give him a shot. Through equity raises and debt financings, Cheniere assembled the resources to build Sabine Pass. Investors weren’t just betting on Souki; they were buying the broader thesis that America needed LNG imports, and that owning the import gate would be a license to win.

By 2005, Cheniere had effectively shed its identity as a failed exploration company and remade itself into a wager on America’s energy future. Sabine Pass was rising out of the marshland. The logic looked solid. And yet, the future Souki was building for was about to vanish.

III. The Import Terminal Era & Near Death (2005–2010)

Sabine Pass rose out of the Louisiana marsh like a statement of intent. Bechtel, one of the most experienced engineering firms on the planet, was the primary contractor. Crews fought through the Gulf Coast’s worst hits: punishing humidity, endless mosquitoes, and hurricane season always lurking in the background. Not long after ground broke in 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated nearby New Orleans and triggered a brutal shortage of skilled craft labor across the region. Even so, Cheniere and Bechtel kept moving, fighting to hold schedule in a construction environment that was anything but normal.

The whole system was built for one job: bring foreign LNG into the United States. Tankers would dock, the super-cooled liquid would be unloaded into massive insulated storage tanks, then warmed back into gas and pushed into the U.S. pipeline grid. It was heavy-duty infrastructure—specialized cryogenic equipment, huge storage capacity, and a maze of pipes and controls designed to handle temperatures that can destroy ordinary steel. In the years leading up to the financial crisis, Cheniere committed to building what it believed would be a set of import gates for an America that “needed” overseas natural gas.

Sabine Pass began operating in 2008.

And that’s when the premise collapsed.

The culprit came down to two words: shale gas. Starting in the mid-2000s, U.S. producers combined hydraulic fracturing with horizontal drilling and began unlocking gas trapped in shale formations that had been uneconomic for generations. One by one, major plays surged: the Barnett in Texas, the Marcellus in Appalachia, and others that quickly followed. Supply didn’t just rise—it flooded the market.

Natural gas prices did what commodity prices do when supply surprises everyone: they fell hard. Before shale, prices had been high enough that importing LNG seemed like a rational solution. By 2009, prices had dropped to a level that made imported LNG—after you paid for liquefaction overseas, shipping, and regasification—look absurd.

For Cheniere, this wasn’t a headwind. It was a broken business model.

They had spent billions building a terminal meant to receive expensive foreign gas into a market that was suddenly full of cheap domestic supply. Cargoes that might have been profitable in the old world no longer penciled out in the new one. Sabine Pass didn’t just become less valuable—it started to look stranded.

Public markets reacted accordingly. After peaking in 2007, Cheniere’s stock collapsed to a fraction of its former value by 2009. The company had never been profitable, and now it carried major debt tied to infrastructure that didn’t seem to have a purpose. Survival itself was in question.

This was the period when the story could have ended. Cheniere could have become a cautionary tale about building giant assets based on a consensus view that changed faster than concrete can cure. The board faced ugly options: sell whatever could be sold, liquidate, or shut down and preserve what little value remained.

But Souki didn’t respond like a man defending a failed bet. He responded like a man looking for the next bet.

While others in the industry backed away from LNG imports and declared the U.S. import era over, Souki started flipping the question. If the United States now had too much gas instead of too little, what if Sabine Pass didn’t need to receive LNG at all? What if it could send LNG out?

The idea sounded borderline insane in real time. An import terminal and an export terminal share some useful pieces—storage tanks, marine berths, pipeline connections—but the heart of the system runs in the opposite direction. Import terminals warm LNG into gas. Export terminals do the hard part: they chill gas into LNG. Liquefaction equipment is complex, expensive, and energy-intensive. And at that moment, the United States didn’t have a modern, large-scale LNG export industry from the lower 48. The regulatory pathway was unclear. The precedent was thin. The capital requirements were daunting.

Still, Souki explored whether Sabine Pass could be retrofitted. Not because it was easy, but because the alternative was watching the company slowly bleed out.

From 2008 to 2010, Cheniere lived in triage mode. Inside the company, people wondered whether their jobs would exist next year. Outside the company, investors questioned whether they’d ever see returns. The conversations in the boardroom weren’t theoretical—they were existential.

What kept Cheniere alive was time, bought in small increments. The regasification terminal generated some fee-based revenue from customers who had reserved capacity, even if the cargoes never showed up. Cheniere cut costs and pulled every lever it could to reduce cash burn. It wasn’t prosperity. It was survival.

But the deeper reason Cheniere made it through was Souki’s refusal to treat Sabine Pass as a tombstone. The site still had real advantages: deepwater access, pipeline connectivity, and a regulatory footprint that would be hard for anyone else to replicate quickly. The tanks worked. The docks were there. The team had learned how to operate cryogenic infrastructure safely. If the direction of flow could be reversed, the “mistake” might become the foundation.

By the end of the import era, Cheniere was still standing—but barely. Sabine Pass had gone from crown jewel to stranded asset in the span of a couple years. And the only thing between Souki and oblivion was an idea that most of the industry still thought was impossible.

What came next would decide whether he’d just delayed the inevitable—or set up one of the most audacious pivots in modern energy history.

IV. The Shale Revolution Pivot (2010–2012)

The conventional response to Cheniere’s predicament would have been to cut losses. Sell Sabine Pass for whatever the market would pay. Shrink the company to nothing. Hand back whatever capital remained and move on.

Charif Souki went the other way. In June 2010, Cheniere announced it would add liquefaction capacity at Sabine Pass—turning an import terminal into an export terminal. The reaction was immediate skepticism. To many on Wall Street, it sounded like throwing good money after bad. To much of the LNG world, it sounded like a science project with no obvious way to get financed.

Souki’s logic was simple, and it hinged on one brutal reality: shale had changed the U.S. from a gas-short country to a gas-long one. If America was going to be awash in cheap natural gas for years, then the opportunity wasn’t importing at all. It was exporting. Overseas—especially in Asia—buyers were paying multiples of U.S. prices. Europe, too. If Cheniere could liquefy U.S. gas and put it on a ship, Sabine Pass would stop being a stranded asset and start being a bridge between two completely different price worlds.

But first Cheniere had to win permission to play. The regulatory path was narrow and, at the time, largely theoretical. The Department of Energy controlled export authorizations. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission would have to approve the actual build-out of liquefaction. Environmental reviews, public comment, politics—any one of these could stall the project long enough to kill it.

Cheniere pushed straight into that maze. In September 2010, it received DOE authorization to export LNG to free-trade-agreement countries—useful, but not the prize, because it didn’t cover many of the biggest LNG markets. The real breakthrough came in May 2011, when the DOE authorized Cheniere to export domestically produced natural gas as LNG to any country with LNG import capacity, whether or not it had a free trade agreement with the U.S. In practical terms, it meant Cheniere had opened the door to the global market.

Then came the next hurdle: proving someone would actually buy. In October 2011, Cheniere signed its first LNG sale and purchase agreement with BG Group. BG agreed to buy 3.5 million tonnes per annum for 20 years. The structure mattered as much as the headline volume. Instead of the traditional oil-linked LNG pricing used around the world, this deal was tied to Henry Hub. BG would pay 115 percent of Henry Hub plus a fixed liquefaction fee of $2.25 per million British thermal units.

That was the innovation: a tolling-style model that flipped risk in Cheniere’s favor. Buyers took the commodity exposure; Cheniere earned a steadier, more infrastructure-like stream of revenue for providing liquefaction. It also offered something international customers rarely got in LNG: transparency. Buyers could see the formula, understand the linkage to U.S. gas, and decide whether they wanted that exposure instead of an oil-indexed contract.

Once BG signed, the tone shifted. The idea didn’t feel theoretical anymore. Other big names followed—Korea Gas Corporation, Gas Natural Fenosa, India’s GAIL. Each long-term contract didn’t just add future revenue; it made the financing story more credible. This was how you built something measured in billions: you stacked up enough durable customer commitments that lenders could believe the plant would run.

In April 2012, FERC granted authorization to construct and operate the first two liquefaction trains at Sabine Pass—Train 1 and Train 2. In LNG, a “train” isn’t a metaphor; it’s the full liquefaction unit: the compressors, heat exchangers, refrigeration systems, and all the supporting equipment needed to turn pipeline gas into a super-cooled liquid.

With that approval in hand, Cheniere made a positive final investment decision and started construction. The race was on. The import dream was dead, but now Cheniere was trying to build the first modern, large-scale LNG export facility in the contiguous United States.

And it wasn’t as simple as “reversing the flow.” Import terminals warm LNG back into gas. Export terminals do the hard part: they chill gas down to around minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit and keep it there through storage and loading. Sabine Pass already had valuable pieces—tanks, marine berths, pipeline connections—but the heart of the export system didn’t exist yet. Cheniere had to add massive new liquefaction equipment, integrate it with what was already built, and do it all while the company was still carrying the scars of the import collapse.

Cheniere chose the ConocoPhillips Optimized Cascade process for liquefaction, a proven technology used elsewhere in the world. That decision reduced technical uncertainty, but it also locked in a specific design philosophy and set of equipment choices—decisions that would ripple through cost, schedule, and how the facility would ultimately run.

The people challenge was just as real. There wasn’t a deep bench of U.S. LNG export operators to hire from because, effectively, this modern industry didn’t exist yet. Cheniere had to recruit and train engineers, operators, and maintenance staff from refineries, petrochemical plants, and overseas LNG projects, then build an organization capable of operating safely at cryogenic temperatures and industrial scale.

What Cheniere accomplished from 2010 to 2012 wasn’t a single lucky break. It was a chain of them—regulatory wins, contract wins, then the permission to build—each one necessary, none of them sufficient on its own. Souki had taken an asset the market had written off and found a way to make it relevant again.

But the bet was still only on paper and in steel. Years of construction, and billions in capital, still stood between Cheniere and its first export cargo. And even before that outcome could be proven, a different fight was starting to form—one that had nothing to do with pipelines or permits, and everything to do with control.

V. Construction & Capital Markets Drama (2012–2016)

Building an LNG export facility sits near the top of the energy industry’s difficulty scale. Each liquefaction train at Sabine Pass required billions in capital and an exacting level of engineering. This wasn’t a refinery or a pipeline. It was a cryogenic machine designed to take ordinary U.S. pipeline gas and chill it to roughly minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, then store it safely and load it onto ships. The tolerances were tight, the risks were real, and mistakes didn’t just cost money—they could be dangerous.

Cheniere tackled Sabine Pass in phases. Trains 1 and 2 got the green light in 2012. Trains 3 and 4 came next. Over time, the site would grow to six trains, and each one was its own mini-bet: another round of approvals, another financing, another construction sprint. Bechtel, the EPC contractor, brought deep LNG experience from projects around the world and became the engine behind the build.

The engineering was hard. The financing might have been harder.

Cheniere still had a problem that no amount of optimism could wish away: it was attempting to borrow tens of billions of dollars while having never posted a profit, and while the U.S. had no modern track record of large-scale LNG exports from the lower 48. The solution was project finance—raise money against the Sabine Pass project itself, not the corporate parent, and let lenders underwrite the cash flows of contracted liquefaction capacity rather than Cheniere’s historical earnings.

That’s where the long-term contracts mattered. The sale and purchase agreements with BG, GAIL, KOGAS, and others weren’t just “customers.” They were the foundation of the capital stack. Those contracts gave lenders something they could model: predictable, long-duration revenue with structures designed to hold up even when commodity markets didn’t cooperate.

With that backdrop, Cheniere pulled together an enormous financing package through bank loans, bond issuances, and equity raises—one of the largest project financings ever assembled in the U.S. energy industry. It was a capital-markets leap of faith that Souki’s reversal would work: that U.S. shale gas could be turned into LNG, shipped overseas, and sold into higher-priced markets at scale.

Then, in the middle of all this, Cheniere picked a fight it didn’t need: executive pay.

In 2013, Charif Souki became the highest-paid CEO in the United States. His compensation reportedly hit $142 million, driven largely by equity awards tied to the stock’s performance and development milestones. The number was jaw-dropping even in a boom year—and especially jarring because Cheniere still hadn’t generated profits. Supporters argued he’d pulled off a rescue and deserved to share in the value he was creating. Critics saw it differently: a company loaded with debt, still in build mode, paying Silicon Valley-style compensation before a single export cargo had sailed.

The optics got worse as the commodity cycle turned. Starting in mid-2014, oil prices collapsed from above $100 per barrel to below $50 by early 2015. Natural gas prices weakened too. Across the sector, budgets were cut, headcounts were reduced, and executive pay came under pressure. In that environment, Souki’s pay package became a magnet for scrutiny—and a convenient symbol for anyone who thought Cheniere was building too much, too fast, with too little regard for shareholder returns.

Souki didn’t back down. His strategy wasn’t simply to finish Sabine Pass—it was to win the category. That meant pushing ahead with additional capacity, including a second liquefaction facility in Corpus Christi, Texas. He saw a narrow window: sign contracts, lock in financing, build quickly, and establish Cheniere as the U.S. export champion before competitors could catch up. If the demand was there and the contracts were there, why hit the brakes?

And on the ground, the execution kept validating the plan. Bechtel delivered in a way megaprojects rarely do. The trains came in ahead of their guaranteed completion dates and within budget. In an industry where delays and overruns are practically expected, that kind of performance wasn’t a nice-to-have—it was strategic advantage. Cheniere wasn’t just financing a bold idea; it was proving it could build.

The project finance structure made that execution existential. In normal corporate finance, lenders look at the company’s overall balance sheet and cash flows. In project finance, lenders look at the project—its contracts, its timelines, its ability to generate cash—and they have limited recourse beyond it if things go sideways.

For Cheniere, that meant the contracts did most of the heavy lifting. Lenders could forecast revenues, stress-test scenarios, and size the debt accordingly. The take-or-pay nature of the agreements offered further comfort: customers were generally obligated to pay even if they didn’t lift every cargo. If global gas markets softened, the contractual cash flows were still expected to show up.

But the structure also sharpened the knife. If construction slipped or costs blew out, the consequences wouldn’t just be embarrassment. Delays could trigger covenants, spook lenders, and put the entire enterprise under pressure. Every milestone mattered not only as an engineering achievement but as a financial requirement.

As Cheniere’s asset base grew, its shareholder base shifted too. You had traditional energy investors who understood the commodity world, infrastructure-minded investors attracted to contracted cash flows, and growth investors captivated by the scale of the global LNG opportunity. And then you had another group arriving with a different agenda: activists who saw a company building an empire but, in their view, not delivering enough to shareholders along the way.

By 2015, that last group had a leader. A new force entered Cheniere’s orbit—less interested in the long-term vision and more interested in what the stock could return, and when. His name was familiar to anyone who followed corporate America: Carl Icahn.

VI. The Icahn Takeover & Souki's Ouster (2015–2016)

Carl Icahn is one of the most successful—and most feared—activist investors in modern American finance. His method is famously direct: take a meaningful stake, demand board influence, and push hard for changes that, in his view, unlock shareholder value. Sometimes that means cost cuts. Sometimes it means asset sales. Often it means new leadership. Over decades, he’d made billions applying that pressure at everyone from TWA to Apple to Hertz.

So when Icahn disclosed a big position in Cheniere in August 2015, it landed like a flare in the middle of the Gulf. This was not a company that screamed “activist-friendly.” Cheniere was still in build mode. It was carrying enormous debt. It still hadn’t reached the moment where the whole export thesis turned into steady cash flow. Why show up now?

Because now was when the leverage was greatest.

Shortly after revealing his stake, Icahn secured two seats on Cheniere’s eleven-member board. He kept buying until he owned 13.8 percent of the company, making him the largest shareholder. And once he was inside the tent, the questions started—about strategy, governance, discipline, and whether Cheniere was building an empire when it should have been preparing to pay investors back.

The clash with Souki wasn’t personal at first. It was philosophical.

Souki’s view was that Cheniere had a narrow window to cement its lead. Finish Sabine Pass, yes—but also push forward aggressively at Corpus Christi. Sign more contracts. Lock up more capacity. Put distance between Cheniere and the copycats that were inevitably coming. In his mind, you didn’t win LNG exports by being cautious. You won by being first, fast, and too far ahead to catch.

Icahn saw the same chessboard and wanted a different endgame. Cheniere had spent years raising and burning capital. At some point, the company needed to stop acting like a developer and start acting like a business: tighten costs, prioritize returns, and show a clearer path to profitability. Shareholders had endured the crash, the dilution, the debt, and the constant financing. Icahn wasn’t there to admire the engineering. He was there to get paid.

By late 2015, the tension had become unavoidable. Souki’s compensation—already controversial after he became the highest-paid CEO in America in 2013—kept attracting headlines. The $54 million he made in his final year at Cheniere, up sharply from 2014, became a symbol for critics: a company still waiting for its first export cargo, paying founder-level rewards before the strategy had fully proven itself in cash.

But the pay fight was really a proxy war. The deeper issue was control of the roadmap: keep building for future dominance, or slow down and optimize for shareholder returns.

On December 13, 2015, the board terminated Charif Souki after 19 years leading the company. The timing was brutal. Cheniere was close to the moment that would validate the entire pivot—its first LNG cargo out of Sabine Pass. The company Souki had dragged from the edge of irrelevance was finally about to do the thing no one thought it could. And he wouldn’t be there to see it.

Souki didn’t pretend otherwise. In later interviews, he made his view explicit. “I didn’t do what Carl Icahn wanted me to do,” he told CNBC. Whatever the internal dynamics, the message to the market was clear: Cheniere was entering a new era, and the founder’s grip on strategy was over.

Souki’s exit package ensured he didn’t leave empty-handed. Reports varied widely, putting his severance somewhere between $54 million and more than $150 million depending on how the pieces were counted. Either way, the golden parachute provisions negotiated years earlier did exactly what they were designed to do: make the founder whole, even in a forced exit.

He also wasn’t the first. Souki was the third energy CEO since 2013 to depart after Icahn got involved, another data point in the activist’s well-earned reputation for turning boardroom pressure into management change.

For Cheniere, the immediate problem wasn’t optics—it was continuity. The company was approaching a historic operational milestone with leadership in flux. The board installed an interim team and moved quickly to stabilize the organization. In May 2016, it selected Jack Fusco as president and CEO. Fusco brought operating and leadership experience from Calpine, and his mandate was straightforward: finish what was already underway, run it flawlessly, and translate megaproject success into shareholder value.

The Souki–Icahn fight is a clean case study in the core tension of public markets. Founder-led companies are often built on conviction and an appetite for reinvestment. Activists are often built on the belief that capital has a cost—and that “someday” is not a strategy. Souki looked at Cheniere and saw a platform still being assembled. Icahn looked at Cheniere and saw a company that had consumed years of capital and needed to start delivering returns.

Both arguments were defensible. Souki was right that first-mover advantage in LNG was real and that the build window wouldn’t stay open forever. Icahn was right that shareholders had waited a long time and that discipline mattered, especially with heavy debt and volatile commodity markets in the background. Once Icahn became the largest shareholder and gained board influence, a collision was almost inevitable.

What made it sting—what gives this chapter its edge—was how close Souki was to vindication. He had conceived the pivot, fought through regulators, stacked the contracts, assembled the financing, and overseen the build. Then, just before the payoff arrived in the form of the first ship, he was out.

Whether Icahn’s intervention was necessary to create the Cheniere that came next is impossible to prove. Would Souki have expanded even faster? Would more leverage have created risk during the commodity weakness that followed? Or would an even bigger buildout have compounded Cheniere’s advantage? We don’t get to run the alternate timeline.

What we do know is this: Cheniere kept executing after Souki’s departure. The construction plan held. The facilities came online. The company became the profitable enterprise investors had been promised for years.

The Souki era was over. The company he built would move forward without him—and the first LNG cargo was finally about to set sail.

VII. First Exports & Operational Transformation (2016–2020)

On February 24, 2016, the LNG carrier Asia Vision pulled away from Sabine Pass, Louisiana, carrying the first cargo of domestically produced liquefied natural gas ever exported from the contiguous United States in the modern era. The tanker—about 160,000 cubic meters, owned by Chevron—was headed for Brazil. Petrobras would take delivery at its Bahia LNG terminal.

For Cheniere, this was the moment the entire saga had been pointing toward. More than a decade earlier, Sabine Pass had been conceived as an import gate. Then shale turned it into a stranded asset. Then Souki made the heretical call to reverse it into an export machine, and Cheniere fought through regulators, contracts, and financing to make that reversal real. Now, finally, a ship was steaming out of Louisiana with U.S. gas in liquid form—proof that the pivot wasn’t just clever PowerPoint.

Souki wasn’t there to watch the ship leave. But the strategy he’d bet the company on had crossed the line from theory to history.

Commercially, the cargo’s path showed how global and flexible LNG had become. Shell purchased the cargo under a contract arrangement and ultimately delivered it to Petrobras in Brazil. Once it was regasified at Bahia, it fed into Brazil’s pipeline network, supplying demand that included thermal power plants.

The symbolism was impossible to miss. For most of the prior century, America had largely thought of itself as an energy importer. Now it had a new export commodity—one that could travel anywhere there was a ship and a terminal. The shale boom didn’t just solve domestic supply. It created surplus. Cheniere was the company that turned that surplus into seaborne exports first.

And Brazil mattered as a destination. It made the point that U.S. LNG didn’t need to be a niche product sold only into one region. It could compete across oceans, in markets far from the Gulf Coast. Europe and Asia would become major destinations too—but this first delivery showed the global map was open.

With exports underway, Cheniere had to become a different kind of company. Development and construction are about contractors, schedules, and constant fundraising. Operations are about the unglamorous grind: reliability, maintenance, safety, and running equipment hard without breaking it. It’s one thing to build an LNG plant. It’s another to operate it like an airline—day after day, with customers depending on every departure.

That shift is where Jack Fusco fit. Under Fusco, Cheniere moved from being a developer with a vision to an operator with a scorecard. The question stopped being “Can you build this?” and became “Can you run it flawlessly, and can you turn it into cash?”

The ramp-up at Sabine Pass came quickly. Train 2 entered commercial operations in September 2016. Train 3 followed in March 2017. Train 4 came online in October 2017. And the pattern became Cheniere’s calling card: each train was completed ahead of schedule and within budget—an almost suspiciously rare achievement in megaproject land. Bechtel and Cheniere had found a rhythm that kept delivering.

At the same time, Cheniere was building its second pillar: Corpus Christi, Texas. The Corpus Christi Liquefaction project launched with three trains totaling about 15 million tonnes per annum of capacity. The site produced its first LNG in November 2018. Train 2 followed in August 2019. Train 3 reached substantial completion in March 2021.

Even with Corpus Christi extending beyond this period, the direction by 2020 was clear: Cheniere wasn’t a one-asset story anymore. It was building a network.

That operational consistency changed how investors talked about the company. Early on, Cheniere had been valued like a high-stakes construction bet: huge upside, huge risk, and a constant fear of delays, overruns, or some regulatory shoe dropping. As train after train turned on, the narrative shifted toward something closer to infrastructure: contracted cash flows, repeatable performance, and an asset base that was very hard to replicate.

The financial transformation followed the steel. The long-term contracts Souki had stacked up years earlier were no longer “future revenue.” They were revenue. The tolling model did what it was designed to do: it made the business less dependent on commodity price swings and more dependent on keeping the facility running. And as the cash flows arrived, Cheniere finally started to look like the major corporation it had been building toward. In 2019, it landed on the Fortune 500 for the first time—an outcome that would have sounded absurd during the import-terminal near-death years.

Internally, the priorities matured too. Cost control tightened. The organization was streamlined. And for the first time, returning capital to shareholders became more than a distant concept. During the Souki years, expansion had been the point—build capacity before the window closed. Under Fusco, the message shifted to operating discipline and shareholder returns: execute, generate cash, and prove the machine works.

By 2020, Cheniere operated the largest LNG export platform in the United States. Between six trains at Sabine Pass and three at Corpus Christi, total capacity was around 45 million tonnes per annum. This was the moat Souki had talked about, now made real: competing projects would take years and billions of dollars to permit, finance, and build. In a capital-intensive business, being first wasn’t a marketing line. It was an advantage you could measure in years.

Fusco’s background helped in exactly the way you’d expect. At Calpine, he ran a fleet of natural gas power plants—industrial assets where reliability is everything and downtime is expensive. LNG liquefaction is the same kind of game. When equipment trips unexpectedly, it doesn’t just hurt production; it can strain customer relationships and cost real money fast.

Over time, Cheniere’s operational culture took shape around the fundamentals: safety, reliability, and efficiency. Safety had to be a non-negotiable in a world of cryogenic temperatures and high-energy industrial systems. Reliability improved as crews gained experience with the equipment. Efficiency climbed as the company learned how to optimize across an expanding fleet.

Commercially, Cheniere stayed close to the playbook that had gotten it here: long-term contracts with strong counterparties, plus enough flexibility to participate in spot market opportunities. That balance kept revenue visibility while preserving upside when global markets tightened.

By the end of the decade, the pivot was complete. Cheniere had gone from a developer with a daring idea to a running system—an operating export platform throwing off real cash flows. The company had survived its own near-death experience, executed one of the most consequential reversals in U.S. energy history, and emerged as the dominant American LNG exporter.

And then the world changed again—this time in a way that would make Cheniere’s position even more valuable than anyone had modeled when that first ship left Sabine Pass.

VIII. Global Energy Crisis & Strategic Position (2020–Present)

At first, COVID looked like it might be the next existential shock. Economic activity froze, global LNG demand sagged, and cargo cancellations jumped. For a stretch in 2020, international gas markets felt like they were in free fall.

Then the world restarted—and energy demand restarted with it. As economies reopened, the rebound came fast. Supply chains were tangled, supply wasn’t keeping up, and natural gas prices began climbing again. By late 2021, Europe was already under strain. Prices surged to levels not seen in years, pushed up by a messy mix of underinvestment, weaker-than-expected renewable output, and rising anxiety about Russia as a dependable supplier.

And then, on February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine.

It was an eerie coincidence: exactly six years to the day after the Asia Vision left Sabine Pass with the first modern LNG export cargo from the lower 48. In 2016, that voyage was proof of a business model. In 2022, LNG became something bigger—an instrument of geopolitics.

Europe’s gas system broke almost overnight. Russia had supplied roughly 40 percent of Europe’s natural gas, much of it through pipelines. As the war escalated, Russia cut about 80 billion cubic meters of pipeline gas to Europe. The gap was enormous, and the stakes were immediate: heat, power, and industrial survival.

That’s where Cheniere suddenly found itself not just well-positioned, but essential. Europe needed molecules, fast, and LNG was the most scalable alternative. According to International Energy Agency analysis, alternative supplies—especially LNG from the United States—covered more than 40 percent of the deficit created by the Russian cuts.

Cheniere couldn’t magically produce more LNG on command. These plants run at designed capacity; you don’t “turn them up” the way you might with a trading desk. But Cheniere could do something almost as valuable: redirect cargoes, optimize shipping, and use commercial flexibility to get supply to the places that were shouting the loudest. The contract structures Souki had helped popularize—less rigid, less destination-locked—gave both Cheniere and its customers options that older LNG deals often didn’t.

The financial impact was immediate. In 2022, Cheniere posted record revenue of about $33.4 billion, more than double the year before. Net income reached $4.5 billion. The company that spent most of its life as a levered construction story had become, very suddenly, a major cash generator.

And that cash forced a strategic pivot of its own: from proving the model to proving the payout. In 2022, Cheniere rolled out its “20/20 Vision” capital allocation plan—continue investing in growth, return meaningful capital through buybacks and dividends, and push toward investment-grade credit metrics. The company initiated its first-ever quarterly dividend. Over the following years, share repurchases retired about 10 percent of shares outstanding.

In a sense, this was the outcome Carl Icahn had pushed for years earlier: a Cheniere that didn’t just build, but returned capital. Even if the timeline was longer than any activist would prefer, the “returns” era had arrived. In June 2022, Cheniere repurchased about $350 million of shares held by Icahn and affiliates, effectively closing the loop on a boardroom relationship that began back in 2015.

Icahn was explicit about how it turned out. “To date, we have made over $1.3 billion in realized and unrealized gains on Cheniere,” he said. The activist who helped push out the founder walked away with a spectacular outcome. Whether Souki staying in charge would have created more value—or more risk—is one of those unanswerable counterfactuals that hangs over energy history.

Underneath the volatility, the long-term contract engine kept humming. In August 2018, Cheniere signed a 25-year agreement with CPC Corporation, Taiwan, worth about $25 billion, to supply around 2 million tonnes per annum—roughly 30 shipments a year. Deliveries began in 2021. Deals like this were the core of the Cheniere model: long duration, creditworthy counterparties, and cash flows you could finance against.

Cheniere kept building, too. On December 30, 2024, it announced the successful production of first LNG from Train 1 of the Corpus Christi Stage 3 expansion. Stage 3 had started construction in mid-2022, again with Bechtel as the primary contractor. The project is designed to add more than 10 million tonnes per annum of capacity across seven midscale trains. When complete, Cheniere’s total operational capacity is expected to exceed 55 million tonnes per annum.

The execution story stayed consistent with what made Cheniere different in the first place. The first Stage 3 train reached substantial completion more than six months ahead of its guaranteed completion date. In megaproject terms, that kind of performance isn’t just operational pride—it’s strategic advantage.

The flood of cash from the crisis years also changed the balance sheet. Cheniere used the windfall to reduce debt and improve credit metrics. Investment-grade ratings—once a distant, aspirational milestone for a company that had lived in project-finance land—started to look achievable. That, in turn, meant lower borrowing costs and less financial fragility for whatever came next.

Stage 3 also reflected an evolution in how Cheniere wanted to build. Instead of only relying on the massive, monolithic trains that defined Sabine Pass and the first Corpus Christi phase, Stage 3 leaned into smaller, modular midscale trains. The idea: reduce construction risk, bring capacity online faster, and gain more operational flexibility.

By this point, the world was treating U.S. LNG as more than a commodity. For Europe, it had become a strategic lifeline. For policymakers, it was a component of alliance management and energy security. For Cheniere, that elevated status brought opportunity—and a tightrope: meet urgent European demand without breaking commitments to long-term customers in Asia and elsewhere. Again, flexibility in the contract book mattered. It allowed supply to move where it was needed most, without tearing up the commercial foundation that made the whole system financeable.

As of early 2026, Cheniere had exported nearly 4,000 cumulative LNG cargoes totaling about 270 million tonnes to roughly 40 markets worldwide. Its market capitalization approached $50 billion. The company that once looked like it might die beside a stranded import terminal had become one of America’s most valuable energy businesses—built on a product that, in a crisis, turned from “fuel” into “security.”

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Cheniere’s journey leaves behind a playbook that’s useful far beyond LNG.

The Art of the Pivot: Souki’s decision to walk away from the import thesis and bet on exports became one of the great pivots in modern American business. The trick wasn’t pretending the original plan hadn’t failed. It was realizing the asset underneath the plan still mattered. Sabine Pass had the location, the permits, the storage tanks, the marine access, and the pipeline connections. Those didn’t lose value just because the direction of global gas flows flipped. Instead of selling a “mistake” at distressed prices, Souki reframed it as a platform. The investor takeaway is uncomfortable but important: when disruption hits, the business model might be broken while the assets are still valuable—and that gap is where turnarounds are born.

Infrastructure as Moat: LNG terminals aren’t features. They’re forts. They take years to permit and build, require enormous capital, and—once operating—can run for decades. That time-and-capital burden becomes a barrier that’s hard to shortcut. Even well-funded competitors have to live through the same multi-year construction window, during which market conditions can change and financing can tighten. Cheniere’s early move into U.S. exports didn’t just give it first cargo bragging rights; it gave it a head start measured in years.

Timing vs. Creating Markets: Was Souki a visionary who saw exports coming, or was he lucky that shale arrived right as he happened to own the perfect Gulf Coast site? The cleanest answer is: both. Cheniere’s story is a reminder that great outcomes often come from the collision of insight and circumstance. Investors should be wary of narratives that credit strategy alone while ignoring timing, macro tailwinds, and regulatory luck. In commodities and infrastructure, those external forces aren’t background noise—they’re the plot.

The Role of Activists: Icahn’s involvement shows the double edge of activism. On the positive side, he pushed capital discipline and helped accelerate the shift from perpetual build mode to a company that returned capital. On the negative side, pushing out the founder months before the first exports forced the question Cheniere will always carry: what value was created, and what value might have been lost, by ending the Souki era right before vindication? Icahn’s eventual $1.3 billion in gains doesn’t settle the debate. It only proves that activism can be lucrative, not necessarily that it’s optimal.

Long-Term Contracts as Strategy: Cheniere didn’t finance Sabine Pass and Corpus Christi on hope. It financed them on contracts. The 20-year agreements created the revenue certainty lenders demanded and, later, the predictability that supported stronger credit ratings. Just as important, the tolling-style structure—Henry Hub-linked pricing plus a fixed fee—pushed commodity risk toward buyers while giving Cheniere a steadier, infrastructure-like stream of cash flow. In other words: in LNG, the contract design is often as decisive as the steel in the ground.

Capital Allocation in Cyclical Industries: Energy forces a permanent argument: reinvest or return? Cheniere lived both extremes—Souki’s push to build aggressively and Icahn’s push to prioritize shareholder payouts. The later “20/20 Vision” framework was essentially an attempt to formalize a truce: keep growing, but also pay. For investors, the lesson is to study capital allocation philosophy the way you’d study a balance sheet. In cyclical industries, how management spends money is the strategy.

Execution as Competitive Advantage: In megaproject businesses, execution isn’t operational hygiene—it’s a weapon. Cheniere’s ability to deliver trains ahead of schedule and within budget did more than save money. It built credibility with customers, lenders, and the market. That credibility lowers the cost of future capital and makes counterparties more willing to sign long-term commitments. If you’re evaluating infrastructure companies, past execution is often the most honest proxy you’ll get for future success.

The Value of Flexibility: Cheniere benefited from contract structures that didn’t lock cargoes into rigid destinations and that tied pricing to Henry Hub. That flexibility looked like a commercial nuance on day one. During Europe’s crisis, it turned into real strategic value. Two contracts can look similar on the surface and behave very differently under stress depending on where the optionality sits. In commodity markets, embedded flexibility can be worth more than the obvious headline economics.

Management Transitions: Cheniere also illustrates a leadership truth most companies learn the hard way: the skills to imagine and finance a transformational build aren’t the same skills required to run, optimize, and return capital once the asset is operating. The company’s shift from Souki’s founder-led, development-first posture to Fusco’s operator-led, returns-and-reliability focus is a case study in matching leadership to the phase of the business.

Regulatory and Political Risk: Finally, none of this happens without permission. DOE export authorization and FERC approvals weren’t paperwork—they were existential gates. A denial, a delay, or a political shift at the wrong moment could have killed the project or made financing impossible. For investors, infrastructure returns are inseparable from regulatory reality. Understanding the rules, the stakeholders, and management’s ability to navigate them is part of underwriting the business.

X. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

To understand Cheniere’s competitive position, you have to zoom out from any single quarter or cargo and look at the global LNG machine: who controls supply, who controls demand, and what actually creates staying power in a market where the molecules are largely interchangeable.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Supplier Power: Cheniere doesn’t produce natural gas. It buys it, and it relies on the pipeline networks feeding Sabine Pass and Corpus Christi. The good news is the U.S. has abundant supply, and these terminals have access to multiple pipeline systems—so no single upstream producer holds the company hostage. Supplier power is moderate.

Buyer Power: Cheniere sells to utilities, national oil companies, and large traders—generally sophisticated, creditworthy buyers with choices. They can sign with other U.S. exporters, Qatar, or Australia. But LNG isn’t like switching phone carriers: long-term contracts, shipping logistics, and downstream infrastructure make switching meaningful and slow. Buyer power is moderate.

Threat of New Entrants: Building an LNG export facility is a high-stakes endurance test: huge capital needs, long lead times, complex engineering, and a heavy regulatory process. That’s a real barrier. Still, the pipeline of U.S. projects shows it’s not impossible—just expensive and time-consuming. The barrier is high, but not insurmountable.

Threat of Substitutes: Depending on the region, LNG competes with pipeline gas (where geography makes it possible), coal, nuclear, and renewables. Over the long arc, the energy transition adds uncertainty around how much gas demand persists. The substitute threat is moderate today and higher over longer time horizons.

Industry Rivalry: Rivalry is rising. Qatar is expanding. Australia remains a heavyweight. New U.S. capacity continues to come online. In a commodity market, more supply usually means more competition, and the LNG industry is moving in that direction.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework:

Scale Economies: Cheniere’s size matters. Spreading fixed costs over large volumes lowers unit costs and supports stronger economics than smaller, less utilized projects. This is a real source of advantage.

Network Effects: LNG doesn’t have classic network effects, but there’s a softer version here: relationships and know-how across shipping, customers, and trading. The better you are at moving cargoes and solving logistics problems, the more valuable you become to counterparties.

Counter-Positioning: The original export pivot was pure counter-positioning—Cheniere moved before the consensus did. Today, the industry has largely adopted the same playbook, so this edge is more historical than structural. The remaining benefit is first-mover momentum: experience and embedded relationships that aren’t trivial to replicate.

Switching Costs: Cheniere’s long-term contracts create real switching costs. Once a buyer commits capacity under multi-year terms, the relationship becomes sticky—commercially, operationally, and often politically.

Brand: In commodities, “brand” usually means “do you deliver when you say you will?” Cheniere’s operational reliability has become part of its reputation with customers and the market, even if it’s not a consumer brand in the traditional sense.

Cornered Resource: The hard-to-copy assets are the sites themselves: existing terminals, permits, pipeline connections, and Gulf Coast deepwater access. Those are scarce, and they’re much easier to defend than they are to create from scratch.

Process Power: Cheniere’s consistent record of delivering projects ahead of schedule and within budget is more than luck. In this business, execution capability compounds. It lowers financing friction, builds credibility with customers, and reduces the odds of the kind of megaproject failure that can permanently damage a developer.

Bull Case: Cheniere has infrastructure that is difficult to replicate and can generate cash for decades if global LNG demand holds. Its operating track record differentiates it in a market where reliability is currency. Europe’s need for non-Russian supply creates structural support for U.S. LNG, and longer-term demand growth in Asia—especially in developing economies—can keep volumes moving. With a stronger balance sheet and clearer capital allocation discipline, Cheniere can pursue growth while returning capital to shareholders. Management has shown it can navigate volatility.

Bear Case: LNG is a cyclical industry with long lead times—which is a polite way of saying it’s prone to oversupply. A large wave of new capacity from Qatar, the U.S., and others could pressure pricing and profitability. Over the longer run, electrification, renewables, and policy shifts could slow or cap gas demand, raising stranded-asset risk for long-lived infrastructure. While Cheniere’s leverage has improved, debt is still meaningful. Geopolitics can also disrupt shipping routes or demand patterns. And the crisis-era pricing environment created by the Russia–Ukraine war may fade, pulling the market back toward more normal conditions.

Competitive Landscape Assessment:

The global LNG market is getting more crowded, and the key question is whose cost structure and execution hold up when the market isn’t tight.

Qatar is the most obvious heavyweight. With some of the lowest-cost gas resources in the world, it’s expanding through the North Field projects and can sit lower on the global cost curve than most competitors. In an oversupply scenario, that matters.

Australia is also a major supplier, and it has deep customer relationships across Asia. Many Australian projects were defined by cost overruns and delays, which hurt competitiveness versus what developers originally promised. But the capacity exists, and the region remains a major source of LNG supply.

In the U.S., competition keeps arriving. Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass began exports in 2022. Freeport LNG resumed operations after a 2022 incident. And a long list of additional Gulf Coast projects sits at varying stages of development, ready to move if contracts and financing come together.

Cheniere’s edge comes down to a handful of things that compound: being early, having real scale already online, a strong operating record, and a customer base built over years of contracting. Whether that edge stays wide depends on how aggressively new supply enters the market and whether Cheniere can keep converting execution into lower costs, higher reliability, and better commercial outcomes.

Key Performance Indicators: Investors tracking Cheniere should focus on:

-

Distributable Cash Flow per Share: The cleanest expression of what the business can actually return to owners, after operating costs and maintenance capital.

-

Contracted Volume as Percentage of Capacity: A simple read on visibility versus exposure. Higher contracted volumes generally mean steadier cash flows; a lower percentage can mean more upside—or more volatility.

-

Liquefaction Margin and Utilization: How much value Cheniere is capturing from its assets, and how consistently the plants are running. Falling utilization or compressed margins can be an early signal of operational issues, market softening, or competitive pressure.

XI. Epilogue & "What Would We Do?"

Charif Souki didn’t fade quietly into retirement after leaving Cheniere. Within months of his ouster, he teamed up with Martin Houston, a former BG Group executive, to found Tellurian Inc. The plan felt like a remix of the playbook that made him famous: build a new LNG export facility—Driftwood LNG—in Louisiana. He raised capital, signed preliminary agreements, and started working the permitting process.

But this time, the terrain was different. Tellurian struggled to reach a final investment decision and, more importantly, to line up the financing. Volatile gas markets complicated the economics. And Souki’s personal finances began bleeding into the public story. He lost 25 million Tellurian shares in a foreclosure tied to a personal loan, and the lender sold the stock into the market. In December 2023, after an investigation into undisclosed personal dealings with a Tellurian lender, Souki was dismissed as executive chairman.

The fallout didn’t stop there. Two companies owned by Souki later filed for bankruptcy, including the family’s Aspen real estate developer and a holding company that owned his luxury yacht. An auction of Aspen properties and the liquidation of other assets weren’t enough to cover debts that were reported to exceed $100 million. The founder who helped set Cheniere’s trajectory ended up in personal financial distress.

Put next to each other, the trajectories are almost too clean. Cheniere—the company Souki built—grew into a cash-generating infrastructure giant. Tellurian—the company he started afterward—collapsed. Whether that contrast comes down to first-mover advantage, the difference between building in a favorable market window versus a punishing one, or simply the brutal variance of megaproject capitalism is hard to disentangle. But the outcome is unambiguous.

Meanwhile, Cheniere kept doing what it has done best: executing. Corpus Christi Stage 3 moved ahead, and management signaled interest in additional growth, potentially including new trains at Sabine Pass. At the same time, the world kept supplying fresh reasons LNG might matter: the AI-driven data center boom pushed electricity demand higher, benefiting natural gas generation and reinforcing the value of reliable supply chains for gas—domestically and globally.

None of this is frictionless. Cheniere still has to navigate shifting regulatory climates, intensifying competition, and the long-run question hanging over all hydrocarbons: what happens to gas demand in a decarbonizing world? Jack Fusco’s job has been to keep the machine running, keep expanding where it makes sense, and keep translating steel and contracts into results—exactly what the board wanted when it chose an operator to follow a founder.

Looking forward, the company’s big decisions are capital allocation decisions. How hard do you push new capacity? How much cash goes back to shareholders versus back into growth? The core tension Carl Icahn identified—build versus return—never really goes away. It just gets managed.

For investors, Cheniere remains a rare case of reinvention at industrial scale. It survived an existential crisis, flipped an entire business model, and matured from a leveraged construction story into an operating platform built to last. Whether that durability holds over the coming decades, as energy systems evolve in ways nobody can fully model, is what will determine how this story ultimately ends.

It’s worth coming back to that first ship out of Sabine Pass in February 2016. It carried LNG, yes—but it also carried proof. Proof that a stranded asset can become a foundation. Proof that contracts and capital markets can be assembled into something real. Proof that abandoning a failing strategy can be the most valuable decision a company ever makes.

And it also carried a question that never fully resolves: who should get to steer once the bet starts paying off?

Cheniere’s history is a reminder that outcomes don’t come from one force. They come from collisions: the visionary founder who saw a path no one else believed in, the activist investor who demanded discipline, and the operating CEO who turned a buildout into a reliable cash machine. The Cheniere that exists today is the sum of all of it—including the parts that ended in boardroom exits.

If you’re looking at Cheniere now, the backward-looking story is fascinating—but the forward-looking questions are what matter: Does global LNG demand keep growing? Can Cheniere defend its position as new supply arrives? Does the energy transition bend the demand curve down faster than expected? And how will management deploy the cash this business generates?

The next chapter won’t be decided by what Cheniere survived. It’ll be decided by how it answers those questions.

XII. Recent News

Cheniere’s latest results show the company doing what it’s built to do: run the machine hard, safely, and profitably. In full-year 2024, revenue was about $15.7 billion and net income was about $3.3 billion. It also shipped a record 646 LNG cargoes while maintaining top-quintile safety performance.

On the growth front, Corpus Christi Stage 3 hit an important milestone: first LNG from Train 1 on December 30, 2024. Substantial completion followed more than six months ahead of the guaranteed date, and the remaining trains continued moving forward on an accelerated schedule.

The other headline is payouts. Capital returns have picked up speed. In mid-2024, Cheniere raised its quarterly dividend by 15 percent to an annualized $2.00 per share. The board also approved an additional $4 billion of share repurchases through 2027, taking total repurchase capacity to about $5 billion. Since rolling out its capital allocation framework in 2022, Cheniere has bought back roughly 10 percent of shares outstanding.

For 2025, Cheniere guided to Consolidated Adjusted EBITDA of $6.5 billion to $7.0 billion and Distributable Cash Flow of $4.1 billion to $4.6 billion. More than 90 percent of forecast operational volumes were expected to be sold under long-term agreements—exactly the kind of contracted base that gives the company revenue visibility even when markets swing.

Management also kept one eye on the next build. Permitting was underway for potential additional trains at Sabine Pass, and the company’s 2026 LNG production outlook was set to benefit as new Corpus Christi Stage 3 capacity continued coming online.

XIII. Links & References

Company Filings: - Cheniere Energy Annual Reports (10-K) on SEC EDGAR - Cheniere Energy Quarterly Reports (10-Q) on SEC EDGAR - Cheniere Energy Proxy Statements (DEF 14A) on SEC EDGAR - Cheniere Energy Partners (CQP) SEC filings on SEC EDGAR

Recommended Long-form Reading: - "The Export King" — Foreign Affairs (November 2013) - "How One Restaurateur Transformed America's Energy Industry" — The New York Times - "Latest Gamble by Restaurateur Turned Gas Baron" — Houston Chronicle / Bloomberg - Cheniere corporate history: cheniere.com/about/history

Key Industry Resources: - International Energy Agency (IEA) LNG market reports - Global Energy Monitor’s LNG project tracker - Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) LNG authorization records - U.S. Department of Energy LNG export authorization database

News Sources Referenced: - CNBC: "Charif Souki: Carl Icahn behind my Cheniere departure" - Institutional Investor: "Activist Carl Icahn Sticks to His Guns with Cheniere Bet" - Energy Intelligence coverage of the first U.S. LNG export cargo - Natural Gas Intelligence industry analysis

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music