LPL Financial: The Independent Broker-Dealer Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Setup

Picture this: it’s 2024. In a modest office park in San Diego, a financial advisor sits down with a retired schoolteacher to review her portfolio. The advisor doesn’t work for Merrill Lynch. She doesn’t report to Morgan Stanley. She runs her own practice, sets her own hours, and chooses the products she believes are right for her client.

And yet, behind that independence sits something that looks an awful lot like Wall Street—just without the marble lobby. A massive platform handling custody, compliance, research, and technology at a scale that can go toe-to-toe with the giants. That platform is LPL Financial.

Today, LPL is the largest independent broker-dealer in the United States, supporting more than 17,500 financial advisors. It oversees over one trillion dollars in advisory and brokerage assets and generated about $10.3 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2023. It’s also, quietly, one of the most important companies in American finance—because its rise rewired how financial advice gets delivered.

What makes this story so interesting is where it didn’t happen. Not in the gleaming towers of lower Manhattan. Not inside the famous wirehouses that dominated the second half of the 20th century. LPL grew from two small firms founded in the late 1960s and early 1970s—companies most people on Wall Street barely noticed—into a Fortune 500 powerhouse that now competes for the same advisors those wirehouses used to own.

So here’s the central question: how did two obscure firms on the fringes of a wirehouse-dominated industry build the infrastructure that made independence not just possible, but scalable?

The answer runs through founders who recognized the conflicts baked into the wirehouse model, years of technology investment that turned “going independent” from a career risk into a competitive advantage, and an almost stubborn focus on the people who actually sit across the table from clients.

At its core, this is a story about independence—what it really means, what it costs to build, and why it ends up winning. It’s about scale economics Wall Street didn’t fully appreciate until it was too late. It’s about navigating regulation so well that compliance stops being a tax and becomes a moat. And it’s about a quiet revolution that shifted incentives, bringing the advisor and the client closer to the same side of the table.

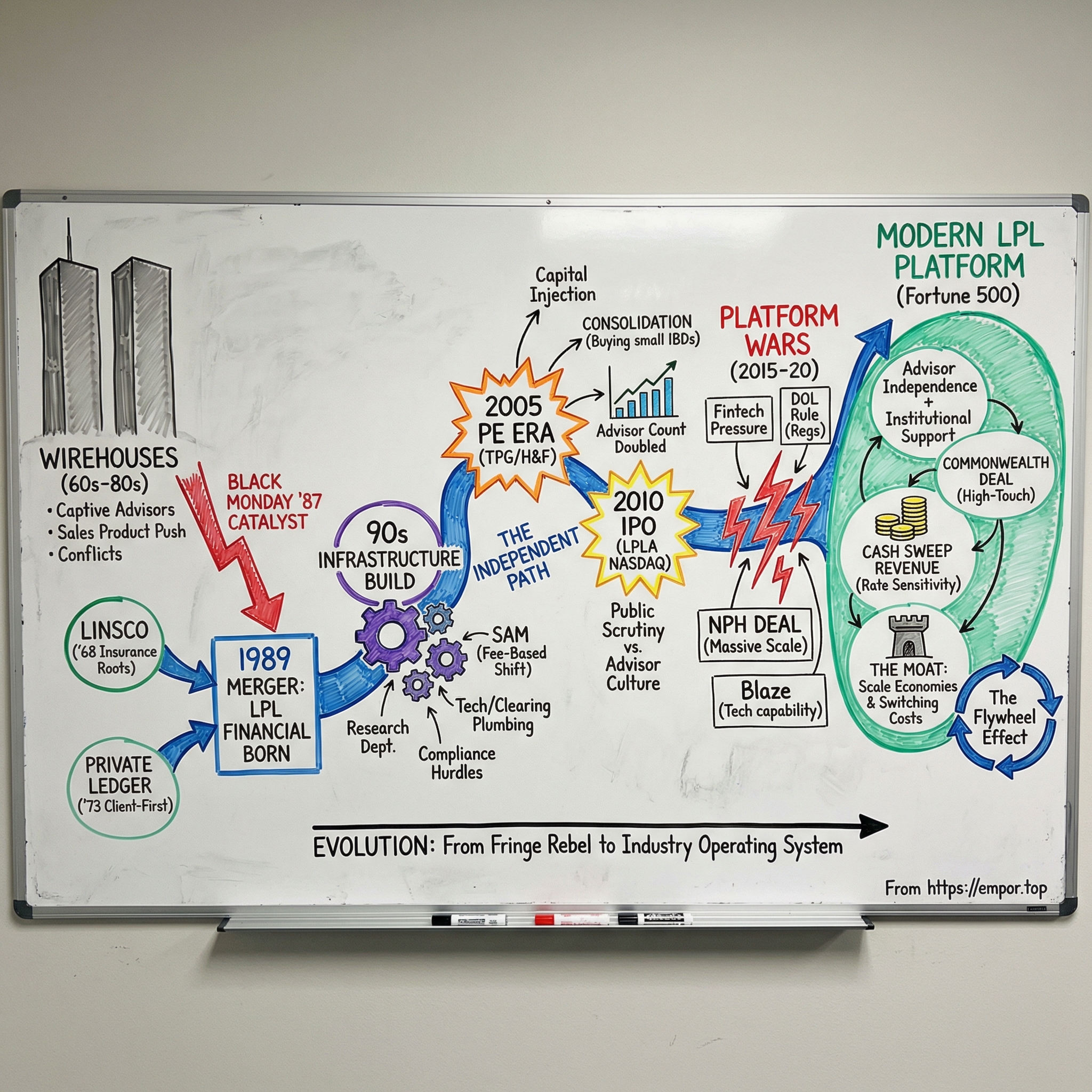

From post-1960s disruption, through the chaos of Black Monday, all the way to Fortune 500 dominance, LPL’s journey reveals something bigger than one company’s success: in financial services, infrastructure eventually beats distribution—and the most powerful revolutions are often the ones built patiently, out of sight.

II. Origins & The Anti-Wirehouse Thesis (1968-1989)

To understand what LPL’s founders were rebelling against, you have to picture the wirehouse world of the 1960s and ’70s. The term “wirehouse” came from the telegraph wires that once tied far-flung branches back to headquarters. But by the post-war era it meant something much bigger: the dominant American model for advice—huge, vertically integrated firms where advisors were employees, products were often proprietary, and loyalty flowed up to the firm far more than out to the client.

Inside Merrill Lynch or Dean Witter, a financial advisor was, at heart, a salesperson. The firm designed and packaged the products—mutual funds, annuities, structured notes—and the advisor’s job was to move them. Pay made sure everyone understood the assignment. Sell what the firm wanted sold, and you earned more. Sell an outside product, and you earned less. The math was simple. The conflict was the point. And the client, by design, sat at the very end of a value chain optimized to extract revenue from every relationship.

Branch offices could feel like a strange mix of boiler room and country club. There were quotas, contests, leaderboards, and a steady drumbeat to push whatever headquarters was promoting that quarter. Advisors who wanted to do real planning—who measured success in client outcomes, not transaction volume—ran into a hard wall: the system didn’t reward that kind of work. Many adapted. A few couldn’t stomach it. And some of those people started building an alternative.

The “anti-wirehouse” thesis was straightforward: if you gave good advisors the freedom to choose what was best for clients—and the infrastructure to run a real business—they wouldn’t just survive outside the wirehouses. They’d outperform them.

The rest of LPL’s story starts with two separate bets on that idea.

The Birth of Private Ledger

Bob Ritzman was one of the early dissidents. In 1973, far from Wall Street’s gravitational pull, he founded Private Ledger around an idea that sounded almost radical for its time: advisors should be able to recommend what they believed was best for the client, not what was best for the home office.

Ritzman saw an opening the big firms had obscured. True financial planning—holistic advice that went beyond the sale of a single product—was largely absent, not because clients didn’t need it, but because the incentive system made it irrational for advisors to offer it. If you got paid for transactions, you built a business around transactions.

Private Ledger flipped the relationship. Ritzman equipped his advisors with a broader menu of investment options and, crucially, empowered them to choose based on client needs rather than firm economics. And he treated advisors less like a captive salesforce and more like independent professionals. In the wirehouse model, the firm “owned” the client relationship; if the advisor left, the book stayed behind. Under Ritzman’s approach, the advisor built something portable—something that belonged to them.

It wasn’t just a different payout grid. It was a different answer to the question, “Who is this business for?”

Linsco and the Insurance Connection

At the same time, another strand of independence was forming through a very different channel: insurance.

In 1968, Life Insurance Securities Corp—later known as Linsco—was established to serve insurance agents who wanted to expand into securities. That detail matters. Insurance agents already understood how to operate independently. They weren’t employees sitting in a branch office; they built their own practices, owned their own client relationships, and served families for decades. When they wanted to add investments to their toolkit, they needed a broker-dealer that spoke their language.

In 1985, Todd Robinson bought Linsco with a view that turned out to be perfectly timed. He believed a wave was coming: more advisors would want to run their own practices and escape the wirehouse production culture. If someone could provide the plumbing—custody, compliance, product access, basic support—advisors would choose freedom.

Then the market gave him a catalyst.

Black Monday as Catalyst

October 19, 1987: Black Monday. The Dow plunged almost 23 percent in a single session. The shock wasn’t just the number—it was the speed and violence of it. On Wall Street, the response was immediate and predictable: panic, retrenchment, and layoffs.

For Robinson, it was a brutal confirmation of his thesis. Advisors inside the big firms had traded independence for the promise of stability, a brand name, and resources. Now, in a single day, many saw how conditional that deal really was. When the firms needed to cut risk and cut costs, loyalty disappeared. Careers built inside “someone else’s house” suddenly looked fragile.

In the wake of Black Monday, a pool of experienced advisors—many with real client relationships—found themselves disillusioned, displaced, and open to a different model. The moment created supply. Robinson’s bet was that independence, with the right platform behind it, could capture it.

The Merger and the Founding Vision

By 1989, it was becoming obvious that Private Ledger and Linsco were solving adjacent halves of the same problem. Private Ledger had proven that open-architecture advice and advisor autonomy could work. Linsco had built a home for independent-minded professionals who wanted access to securities. Together, they could create something neither could fully build alone: a scaled platform designed for independence.

So Ritzman and Robinson merged their firms to form LPL Financial.

The founding vision was crisp: the client’s best interests wouldn’t just be “a priority,” they’d be the cornerstone of every decision. Not as a slogan, but as a design principle—baked into incentives, product access, and the way the firm would support advisors.

Even the name reflected the ethos. LPL didn’t try to borrow Wall Street prestige. It was simply the combination of Linsco and Private Ledger—two firms that believed the future of advice belonged to independent advisors, as long as someone built the infrastructure to let them operate at scale.

That anti-wirehouse origin story matters because it created something hard to copy: trust. Wirehouses couldn’t pivot into “independence” without undermining their own model. And new entrants would learn that independent advisors don’t switch platforms because of a clever pitch. They switch when years of consistent behavior prove the platform is truly on their side.

III. Building the Independent Platform (1990s)

After the 1989 merger, LPL faced the question that separates a nice idea from a durable business: how do you support thousands of independent advisors spread across the country without turning them into employees?

Independence was the pitch. But independence without support is just being alone. Advisors still needed research. They still needed compliance help. They needed systems to open accounts, place trades, produce statements, and solve problems quickly when something inevitably broke. In a wirehouse, all of that came bundled with the marble lobby. In the independent world, someone had to build the bundle from scratch.

So the 1990s became LPL’s infrastructure decade. No splashy acquisitions. No grand rebrand. Just years of unglamorous, foundational work—back-office operations, technology, and regulatory plumbing—designed to make independence not only possible, but better.

Creating Strategic Asset Management

The first big swing came in 1991 with Strategic Asset Management, or SAM. The idea was deceptively simple: put multiple mutual funds into one convenient account, and pay the advisor an annual fee based on assets rather than commissions on each trade.

That change wasn’t just operational. It was philosophical.

Commissions created a built-in temptation to trade—because trading is when you got paid. A fee tied to assets moved the advisor’s incentives closer to the client’s reality. If the portfolio grew, both benefited. If it shrank, both felt it. And the ugliest part of the old system—the constant pressure to “do something” just to generate revenue—started to fade.

But SAM only worked if LPL could run it at scale. That meant building the machinery: billing and reporting, performance tracking, client statements, and the compliance frameworks that come with ongoing advisory relationships. It was the kind of work no client ever sees. It’s also the kind of work that, once done, makes the whole platform stronger with every new advisor who joins.

Research as a Competitive Weapon

SAM created another problem: if you’re going to shift advisors toward ongoing portfolio management, they need serious investment support. Wirehouses could point to their analyst benches and say, “We have the research. You don’t.”

So in 1992, LPL built its own research department.

That mattered for two reasons. First, it gave independent advisors institutional-grade resources they could put in front of clients—actual perspectives on markets, asset allocation, and manager selection. Second, it helped define what an LPL advisor was supposed to be: not a product salesperson taking marching orders from headquarters, but a professional equipped to explain why a portfolio was built the way it was.

Over time, LPL Research would grow into one of the larger, more tenured research groups in the independent brokerage world. But even early on, simply having it changed the conversation. Independence no longer meant giving up sophistication.

Technology as a Competitive Advantage

Then came the internet—and with it, a chance to rewrite what “small” could look like.

LPL saw early that technology could be the great equalizer for independent advisors. A solo practitioner might never have the IT budget of a major wirehouse branch. But if the platform could deliver the right tools—reliably, and at scale—an independent advisor could feel just as modern, just as capable, and often more client-focused.

So LPL invested in the digital backbone of an advisory practice: portfolio reporting, trading interfaces, client communication tools, and research access. Each improvement reduced the friction of running an independent business. And with every workflow that moved onto LPL’s systems, the platform became stickier. Switching firms wouldn’t just mean a new payout grid—it would mean migrating data, retraining staff, and disrupting the client experience.

That’s a subtle but powerful kind of lock-in: not contractual captivity, but operational gravity.

Clearing and Custody Infrastructure

If research and technology made independence attractive, clearing and custody made it viable.

Every trade has to settle. Assets have to be held properly. Records have to be accurate. Statements have to go out on time. Wirehouses had built these capabilities over decades. Independent advisors still needed them—but they couldn’t build them individually.

LPL built the clearing and custody infrastructure that let an advisor operate with the same basic reliability clients expected from the big firms. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was existential. And doing it at scale created a barrier that was hard for smaller competitors to match.

This infrastructure also set up an economic engine that would matter more later: cash in client accounts had to be swept somewhere—into bank deposits or money market funds—and LPL could earn a spread. When interest rates were low, it was a quiet line item. When rates rose, it would become far louder.

The Fee-Based Revolution

All of this fed into a broader shift across the industry: the move from transaction-driven brokerage to ongoing advice.

LPL leaned into that change throughout the 1990s. Not just with SAM, but by building the systems and culture that made fee-based relationships the default. The practical effect was that advisors could spend less time hunting for the next commissionable event and more time doing what clients actually wanted: planning, explaining, adjusting, and staying accountable over years—not days.

It also reframed the advisor’s identity. Under commissions, you’re paid like a salesperson. Under fees, you’re paid like a steward. That shift didn’t eliminate conflicts, but it materially improved alignment—and made the independent model feel like the future, not a fringe alternative.

Regulatory Navigation

And then there was the hardest part to scale: compliance.

An independent broker-dealer lives inside a maze—FINRA (and before it, the NASD), the SEC, and a patchwork of state rules. For an individual advisor, navigating that complexity can become a full-time job. For a platform, handling it well can become a superpower.

LPL invested heavily in the machinery of supervision: monitoring systems, training programs, and legal resources to interpret rules as they evolved. Compliance was certainly a cost of doing business. But it also became a reason advisors joined—and stayed. LPL was building a world where independence didn’t mean living in fear of a regulatory misstep.

By the end of the decade, LPL had assembled something the wirehouses had always taken for granted: an institutional-quality platform. Technology. Research. Clearing. Custody. Compliance. The unsexy essentials.

And that’s why the 1990s mattered so much. LPL wasn’t just adding advisors. It was laying track—so that when the next wave of industry disruption arrived, independence wouldn’t feel like a leap. It would feel like the smart, supported choice.

IV. Private Equity Era & Scaling Up (2005-2010)

By the mid-2000s, LPL had done the hard part. It had proven the independent model could work at real scale, and it was supporting just under 6,000 representatives. The platform was credible. The infrastructure was there. The question now was less “Can this work?” and more “How big can this get?”

To truly compete with the Wall Street incumbents, LPL needed speed and scale. And in 2005, it found both in a place you might not expect for a company built on advisor independence: private equity.

That year, Hellman & Friedman and Texas Pacific Group (now TPG Capital) acquired a majority stake in LPL. The deal valued the company at about $2.5 billion—roughly 2.5 times gross revenue. Analysts at the time called it the richest price ever paid for an independent broker-dealer. Translation: these investors weren’t buying a steady cash-flow business. They were buying a category winner.

The PE Thesis

So why pay a premium for a broker-dealer that, to most of the public, barely had a brand?

Because the ground under financial advice was shifting. The wirehouse model was starting to show real stress. More advisors were frustrated with being employees, with pressure to sell certain products, and with building client books they didn’t truly own. At the same time, the industry was moving toward advice that looked more like stewardship and less like transaction-driven selling, with the fiduciary standard gaining momentum. And looming over everything: demographics. Baby boomers were nearing retirement with unprecedented accumulated wealth, and demand for planning and guidance was only going one direction.

Hellman & Friedman and TPG saw LPL not as a broker-dealer, but as the picks-and-shovels platform for that shift. If independence was the destination, LPL was building the roads. And once the fixed costs of technology, compliance, and operations were in place, every incremental advisor made the whole machine more profitable.

They also saw a second, equally powerful dynamic: fragmentation. The independent broker-dealer market was full of smaller firms that couldn’t keep up—too little scale to invest in modern tech, too little budget to handle rising regulatory complexity, too little leverage to compete for talent. In that kind of market, the leader doesn’t just grow. The leader consolidates.

The Professionalization Playbook

Private equity didn’t just bring capital. It brought an operating agenda.

Under PE ownership, LPL accelerated investment in technology and the less-glamorous capabilities that make scaling possible: integration, onboarding, and the ability to migrate accounts and systems without creating chaos for advisors and clients. What had been built steadily through the 1990s now had to be upgraded and standardized so it could support a much larger organization.

The company’s internal expectations shifted too. Governance strengthened. Reporting got tighter. Controls improved. LPL began to look and run more like a public company, even while it was still private. That wasn’t a cosmetic change—it was a deliberate setup for the next step in the playbook.

Building Critical Mass Through Consolidation

The centerpiece of the PE era was consolidation.

For smaller broker-dealers, selling to LPL offered a clean exit for principals, relief from operational and regulatory burden, and a chance for their advisors to land on a platform they couldn’t realistically replicate. For LPL, each acquisition brought immediate scale—more advisors, more assets, more revenue—without waiting for recruiting to play out one advisor at a time.

And the economics were exactly what the investors had underwritten. The expensive parts of the business—technology, compliance, clearing and custody infrastructure—didn’t have to be rebuilt for each new advisor group. They could be spread across a larger base. As LPL grew, the machine got more efficient.

The Numbers Tell the Story

The results were hard to miss. In 2005, around the time the PE firms bought in, LPL supported just under 6,000 representatives. By March 2010, it had grown to more than 12,000 advisors—more than doubling the network in about five years.

That expansion wasn’t just a headcount flex. It validated the platform thesis: more advisors meant more assets and more revenue flowing through systems whose costs didn’t rise nearly as fast. The bigger LPL got, the more its scale advantages showed up where it mattered—support, economics, and staying power.

Preparing for Public Markets

By 2010, the private equity playbook had largely done what it came to do. LPL had reached a new tier of scale. It had the systems and governance to operate like a major institution. And it had established itself as the clear leader in the independent broker-dealer space.

So the next question became inevitable: what happens when a platform built for independence becomes big enough to tap the public markets?

For Hellman & Friedman and TPG, the answer was straightforward: an IPO. Going public would provide liquidity, create a publicly traded currency for future acquisitions, and cement LPL’s status as more than a niche player. It would be a statement that the independent model had matured into a heavyweight.

Preparation ramped up accordingly—financial systems built for quarterly reporting, controls tightened for Sarbanes-Oxley, and the organization structured for public-company governance and scrutiny.

And in retrospect, that’s why this era matters. It didn’t just make LPL bigger. It set patterns that would define what came next: a disciplined consolidation strategy, sustained platform investment, and an operating model designed to scale. The independent revolution was no longer a movement. It was becoming a public company.

V. The IPO & Public Company Transformation (2010-2015)

On November 18, 2010, LPL Financial Holdings Inc. went public on the NASDAQ Global Select Market under the ticker LPLA. The IPO raised about $470 million and, in the process, put a public-market price tag on what had become the nation’s largest independent broker-dealer.

For a company born from two small firms arguing that advisors shouldn’t have to work inside a wirehouse to build a real career, it was a surreal milestone. But it was also a fork in the road. LPL had spent decades building a platform for independence. Now it had to prove that platform could thrive under the bright lights of public markets.

Because an IPO doesn’t just change who owns the company. It changes who the company answers to.

Public ownership added a new cast of characters overnight: institutional investors, analysts, and financial media, all with expectations and timelines of their own. The quarterly earnings cycle would add discipline, but it would also add pressure. And the scrutiny that comes with being public would test whether LPL’s advisor-first culture could survive in a world that relentlessly measures everything in 90-day increments.

IPO Dynamics

The structure of the offering made clear what this moment was designed to do. Hellman & Friedman and TPG, LPL’s private equity sponsors, sold down portions of their stakes to get partial liquidity after five years. At the same time, they kept significant positions—an important signal that they still believed the growth story had plenty of runway.

LPL also raised primary capital, giving the company more fuel for what it already knew how to do: invest in the platform and keep consolidating the market.

There was another, more symbolic piece: advisors were able to participate in the equity. LPL had always argued that independence should come with ownership—of your practice, your client relationships, your destiny. Letting advisors share in the company’s upside extended that philosophy upward. It wasn’t charity. It was strategy. When advisors feel like owners, they behave like owners: they stick around, they recruit, and they invest in building within the platform instead of treating it as a vendor.

The market liked what it saw. Investors recognized the same logic the PE firms had underwritten: a platform with scale economics riding a long-term shift toward independent advice, run by a management team with a clear playbook.

Public Company Pressures

Then came the harder part: living as a public company.

Quarterly earnings calls. Annual shareholder meetings. Proxy statements. And analysts who are paid, in part, to find questions—even when the business is doing exactly what it said it would do.

For LPL, the tension was real. The company’s edge came from trust with advisors, and trust is built over years. Public markets, meanwhile, reward short-term cleanliness: higher margins now, faster growth now, tighter expense control now. It’s easy for a public company to start pulling levers that look great in a spreadsheet and terrible to the people who actually generate the revenue.

So the real question wasn’t whether LPL could hit its numbers. It was whether it could keep making decisions that reinforced its founding promise: independence with institutional support.

LPL’s leadership leaned into that tension instead of pretending it didn’t exist. They stayed in regular communication with advisors about strategy and values. They maintained the commitment to open architecture and continued the push toward fee-based business. And rather than squeezing the existing base for quick wins, they emphasized durable growth—recruiting and acquisitions—without breaking the advisor relationship that made the model work in the first place.

Political Engagement and Advocacy

Around the same time, LPL started acting more like what it had become: a category leader with a real voice. In 2010, the company formed a political action committee to lobby Washington on behalf of advisors and their clients.

This wasn’t about picking teams. It was about the rules of the game.

Independent broker-dealers lived in a complicated regulatory world, and they often got judged through a wirehouse lens. Securities regulators could apply frameworks built for employee salesforces to independent practices that looked nothing like them. Insurance regulation layered on additional requirements. And the debate around fiduciary standards had the potential to reshape the entire advice industry.

LPL’s view was straightforward: building a great platform wasn’t enough if the environment around it was hostile or mismatched. Scale gave LPL the ability to show up in policy conversations that smaller firms simply couldn’t afford to join. Using that influence on behalf of the independent channel reinforced advisor loyalty and signaled that LPL intended to lead, not just participate.

Early Acquisitions and Organic Growth

With a public stock and easier access to capital, LPL could push harder on two engines at once: acquisitions and recruiting.

The acquisition pipeline stayed active. Smaller broker-dealers faced the same problem they’d been facing for years, only intensifying: technology expectations were rising, regulatory complexity wasn’t getting simpler, and the cost of staying competitive kept climbing. For many, selling to LPL meant relief—and for their advisors, it meant landing on a platform with the resources to keep up.

But organic growth mattered just as much. Recruiting from wirehouses continued as more experienced advisors did the math and decided they wanted to own their practices. LPL invested in the unglamorous work that makes that leap feel safe: transition teams, technology support, and practice financing to help advisors move without blowing up their client experience.

Together, those two engines created a flywheel. More advisors and assets created more scale. More scale funded more platform investment. More platform investment made LPL more attractive. And that attraction brought in more advisors.

By the early 2010s, the story was no longer “independence is possible.” It was “independence is getting easier—especially here.”

Building Institutional Business

LPL also broadened its reach beyond its core retail advisor base by building an institutional business. Banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions wanted to offer investment services without having to build the infrastructure themselves. LPL could provide the technology and compliance backbone, letting partners deliver investment programs under their own umbrellas.

This channel worked differently than retail. Relationships were negotiated, not recruited. The service model emphasized white-label capabilities so the institution could maintain its brand. Decisions ran through committees instead of individual advisors.

But the core economics rhymed with everything LPL had been building for decades: LPL supplied the infrastructure, partners paid for access, and the platform benefited from scale.

By the middle of the decade, LPL had proven something crucial. It could operate with public-company discipline without abandoning the culture that made the independent model compelling in the first place. Advisor-first values and shareholder returns didn’t have to be at war—as long as the platform kept doing what it promised: making independence work, at scale.

VI. The Modern Platform Wars (2015-2020)

By 2015, independence wasn’t a quirky alternative anymore. It was the industry’s growth engine. And when a channel becomes the growth engine, it stops being polite.

LPL was still the biggest independent broker-dealer, but it was no longer operating in a quiet corner. Raymond James had built a powerful hybrid model spanning employee and independent advisors. Ameriprise had carved out real scale in the independent channel. Commonwealth Financial Network, Cetera, and other platforms fought hard for the same prize: the advisor relationship—and the assets that came with it.

This is when the market turned into platform wars. Not just on recruiting checks or payout grids, but on the real stuff advisors feel every day: technology, service, onboarding, and the confidence that the platform won’t let them down when markets get ugly or regulators come calling.

Technology Arms Race

If the 1990s were about building the basic plumbing, the late 2010s were about turning that plumbing into a modern operating system.

Robo-advisors like Betterment and Wealthfront showed up with sleek interfaces and automated portfolios at very low cost. They weren’t necessarily stealing LPL’s typical high-net-worth clients, but they did something arguably more important: they reset expectations. Investors started to assume their financial life should look and feel digital. Advisors started to demand tools that didn’t make them look behind the times.

LPL responded by pouring investment into the advisor-and-client experience. Portals got better. Mobile access became table stakes. And the platform leaned harder into integrations with third-party vendors—less “one monolithic system” and more an ecosystem advisors could build around.

That investment paid off in three ways. It made advisors more efficient. It strengthened the recruiting pitch—independence didn’t have to mean duct-taped tech. And it increased switching costs. Once an advisor’s workflows, data, and client experience are built around a platform, moving isn’t just a business decision. It’s a major operational migration with real risk.

The National Planning Holdings Acquisition

The competition wasn’t only in software. It was in scale—and scale often came from deals.

On August 15, 2017, LPL Financial Holdings signed and closed the acquisition of National Planning Holdings, Inc.’s independent broker-dealer network. NPH was the holding company for four independent broker-dealer firms, and bringing them in made this one of the biggest acquisitions in LPL’s history.

But it wasn’t a simple “add assets, collect synergies” transaction. It was an integration test.

Four firms meant four sets of systems, processes, and cultures. Advisors had to be kept confident through the transition. Clients had to be moved without service disruptions. Platforms had to be consolidated without breaking the day-to-day mechanics of thousands of practices.

LPL took that complexity on because the payoff was strategic: more advisors on the platform, more revenue running through the machine, and one less major competitor in a market that was still deeply fragmented. Just as importantly, it signaled something to the rest of the industry: LPL wasn’t done consolidating. If there was a category leader here, it intended to stay that way.

Regulatory Challenges and Settlements

With size came scrutiny. During this period, LPL—like every major broker-dealer—faced examinations, enforcement actions, and settlements. Regulators focused on areas like supervisory practices, disclosure, and the sale of certain product types. None of it was optional. Each issue demanded management attention, compliance spend, and sometimes financial penalties.

What mattered was how the organization responded. LPL continued investing in supervision, strengthening systems, and expanding training. The goal wasn’t just to get through the issue in front of them, but to build a compliance apparatus sturdy enough for the next one—because in this business, there’s always a next one.

For anyone trying to evaluate LPL from the outside, the right lens is context. The industry is heavily regulated, and enforcement actions are common across large firms. The key question is whether the problems suggest something systemic or something isolated—and whether the company builds better muscle afterward.

The DOL Fiduciary Rule Battle

The defining regulatory saga of the era was the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule.

In 2016, the Obama administration finalized a rule that would require advisors to act as fiduciaries when advising retirement accounts. In plain terms: it threatened commission-heavy business models and would have forced major changes across the advice industry.

LPL was better positioned than many competitors because it had already invested for years in fee-based capabilities. Still, the uncertainty was destabilizing. Firms and advisors had to plan for a world that might arrive quickly, or might not arrive at all—while clients, regulators, and the media all watched closely.

Then came the whiplash: legal challenges, delays, and ultimately a court decision that rejected the rule. But even though the specific rule didn’t survive, the direction of travel did. Expectations were shifting toward fiduciary standards—whether through future regulation, competitive pressure, or what clients increasingly demanded.

In that sense, LPL’s preparation wasn’t wasted. The company had built itself for a more advice-centric world, and the market kept moving that way.

Fintech Integration: Blaze Portfolio

The period ended with a deal that revealed how LPL’s playbook was evolving.

In late 2020, LPL announced it would acquire Blaze Portfolio, a Chicago-based fintech firm founded in 2010. The transaction was signed and closed on October 26, 2020. Blaze brought trading automation capabilities that LPL planned to roll out across its advisor base.

This wasn’t an acquisition for distribution. It was an acquisition for capability.

LPL said it would keep offering Blaze as a standalone product while also integrating its trading functionality into the broader platform. That “both-and” approach—preserve what works, then scale it—reflected a more mature view of technology M&A.

It also pointed to an emerging pattern. As technology became more central to competitive advantage, fintech acquisitions became a natural complement to broker-dealer consolidation. Building everything internally is slow and expensive. Buying proven capabilities can accelerate the roadmap and reduce execution risk.

Stepping back, the 2015–2020 chapter is where LPL proved it could defend leadership in a market that was no longer giving anyone free wins. Competition intensified, regulation stayed demanding, and technology expectations rose fast. LPL kept growing anyway—by investing in the platform, absorbing complexity through major acquisitions, and treating compliance and technology not as side costs, but as the core of what it sold.

VII. Fortune 500 & Scale Economics (2021-Present)

After decades of compounding quietly in the background of finance, the proof started showing up in places even the wirehouses pay attention to. In 2021, LPL joined the Fortune 500 at number 466. By 2024, it had climbed to 392.

That kind of ranking isn’t a trophy you polish for the lobby. It’s a signal: the independent broker-dealer that began as an alternative to Wall Street had become a major American corporation—big enough that its decisions ripple through the advice industry and into the broader economy.

And the deeper point was this: all of the unglamorous platform work—research, compliance, clearing, custody, technology—had finally produced what it always promised. LPL wasn’t just enabling independence. It had turned independence into an at-scale operating model.

The Commonwealth Acquisition

The biggest move of the era arrived with LPL’s planned acquisition of Commonwealth Financial Network, announced in late 2024. Commonwealth was a very particular kind of prize: a wealth management firm supporting roughly 3,000 advisors overseeing about $305 billion in assets. Founded by Joe Deitch 46 years earlier, Commonwealth built its reputation on premium service—an intentionally high-touch culture that attracted advisors who valued support and attention as much as payouts or platform breadth.

Strategically, this wasn’t just “more advisors, more assets.” It was LPL reaching for a different kind of capability.

It was also a test. Many Commonwealth advisors chose the firm because it felt smaller and more intimate—because it wasn’t a giant platform. Keeping them meant LPL had to do something large companies often struggle with: preserve what made a smaller organization special, while still delivering the benefits of scale that justified the deal in the first place.

In theory, the fit was clear. Commonwealth brought strengths in practice management, advisor development, and white-glove service. LPL brought the industrial-grade platform—technology, integration capacity, and the economics that come with scale. Together, the combination aimed to let LPL serve a wider range of advisor preferences: the advisors who want maximum flexibility and efficiency, and the advisors who want a more premium, hands-on experience.

Business Model Evolution

By this point, LPL’s growth had also made the business itself more layered than people assume when they hear “broker-dealer.” Its revenue came from several sources: advisory fees tied to assets, commissions from transaction activity, asset-based platform fees, transaction and other service fees, and interest income earned on client cash balances.

That last category became especially important as interest rates rose. Client cash in LPL accounts was swept into affiliated bank deposits and money market funds. LPL earned a spread between what clients received and what LPL earned from the banks—an engine that expanded meaningfully as rates climbed from the near-zero world that followed the 2008 financial crisis.

But the same feature that creates upside also creates sensitivity. Higher rates can make earnings jump without LPL having to add a single advisor. Lower rates can compress that income just as quickly, even if the underlying platform continues to grow and perform.

Competition with Wirehouses

The most telling competitive shift in this era was LPL’s increasing ability to pull serious talent straight from the wirehouses.

For years, the wirehouse pitch was simple: independence sounds nice, but you’ll give up too much—technology, research, brand, resources. Over time, LPL methodically stripped those arguments of their power. The platform got stronger, the toolset got deeper, and the institutional support got harder to dismiss.

Meanwhile, the economics of independence stayed compelling for experienced advisors with established client books. They could keep more of the revenue they were already generating. They could own the client relationship instead of renting it. They could build equity in a practice they could eventually sell or transfer. And they could step away from the product pressure that still shaped life inside many wirehouse environments.

LPL made that leap easier with explicit transition support: teams to manage the operational complexity, financing to help cover the costs of moving, and technology designed to keep client disruption low. Each successful move became marketing for the next one—proof, circulating advisor-to-advisor, that leaving was not only possible, but increasingly normal.

Platform Consolidation Thesis

Zoom out, and LPL’s strategy in the 2020s fit a broader thesis: the independent broker-dealer landscape was still fragmented. Hundreds of firms existed across a wide range of scale and quality. Many didn’t have the resources to keep up with technology expectations, absorb regulatory costs efficiently, or deliver the level of service that sophisticated advisors demanded. And in many cases, firm principals were nearing retirement without a clear succession plan.

For LPL, that fragmentation wasn’t noise—it was opportunity. Consolidation could keep running for years: bringing in advisors and assets, removing competitors, and spreading the fixed costs of the platform across an ever-larger base. If that endgame played out, the industry would look less like a long tail of small firms and more like a handful of scaled platforms—with LPL at the center of the picture.

This also reframed how to view the company. LPL wasn’t simply operating a big broker-dealer. It was executing a long-duration consolidation and platform expansion strategy—one that could drive growth beyond what recruiting alone would produce.

By the mid-2020s, the takeaway was hard to miss: LPL had reached a level of institutional scale that its founders could hardly have imagined, while still selling the same core promise—independence, backed by infrastructure. The difference now was that the infrastructure wasn’t catching up. It was the point.

VIII. Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand LPL, you have to look past the label “broker-dealer” and see what it actually is: a platform. Not a single, linear business where revenue comes from one obvious source, but an infrastructure layer that sits underneath thousands of advisory practices—and gets paid in several different ways for doing so.

That mix can make the financials look complicated at first. But once you see how the pieces fit, the logic is straightforward: LPL builds expensive, hard-to-replicate capabilities once, then spreads them across a huge base of advisors and client assets.

Revenue Streams Breakdown

LPL’s revenue comes from a handful of distinct engines, each with its own rhythm.

First are advisory fees—income from fee-based accounts where compensation is tied to a percentage of assets under advisement. When client portfolios rise, those fees tend to rise with them. When markets fall, that revenue gets hit too. It’s the cleanest expression of the fee-based model LPL leaned into early: get paid for ongoing advice, not for generating transactions.

Next are commissions, which come from transaction activity—buying and selling securities, insurance products, and other investments. This line tends to swing with investor behavior and market mood. When clients are active, commissions usually rise. When they’re cautious, commissions typically soften. Over time, as the industry has shifted toward fee-based advice, commissions have become a smaller share of the mix.

Then there are asset-based fees tied to the platform itself: the clearing and custody backbone, access to technology, and other services that scale with assets. Transaction and service fees show up too—things like wires, account services, and similar activity-based charges.

And then there’s the sleeper: interest income on client cash balances.

When clients hold cash in their accounts, that money doesn’t just sit there. It’s swept into affiliated bank deposits and money market funds through cash sweep programs. LPL earns a spread between what those sweep destinations pay and what clients receive. When interest rates are low, that spread can feel like background noise. When rates rise, it can become a meaningful contributor—without LPL adding a single new advisor.

The Advisor Value Proposition

So why does an advisor choose LPL instead of staying at a wirehouse—or picking another independent platform?

Because LPL sells a specific bundle: independence with institutional support.

Independence, in practice, means owning your client relationships and your business. In the wirehouse world, advisors can build a book—but the firm ultimately controls the relationship and the platform. At LPL, advisors run their own practices. They can build equity, sell the business, transition it to a successor, or—if they ever choose—move it elsewhere. That portability is a different kind of career asset than a high payout grid.

Institutional support is the other half of the promise. Advisors get technology, research, compliance, and operational infrastructure that would be unrealistic to recreate as a standalone firm. The compliance systems alone would be cost-prohibitive for most individual practices. Same with the depth of research and the ongoing investment required to keep technology modern.

Put those together and you get the core pitch: keep the autonomy and upside of ownership, while plugging into an industrial-grade platform that removes the heavy lifting.

Technology Platform and Scale Advantages

LPL’s technology stack is the product of decades of accumulation: portfolio management, reporting, trading, compliance monitoring, research distribution, mobile tools—the systems that keep an advisory firm running day to day.

The advantage isn’t just that these tools exist. It’s that LPL can keep improving them because scale funds the roadmap.

Most of the costs of building technology are fixed. Once you’ve built a system, adding another advisor doesn’t require rebuilding it from scratch. The same is true for many operational and compliance capabilities. As LPL grows, it spreads those fixed costs across more advisors and more assets. Vendor pricing improves with volume. Specialized expertise gets deeper with repetition. And the platform gets harder for smaller competitors to match.

Over time, that creates a gap that tends to widen, not narrow. A smaller broker-dealer simply can’t invest at the same level while also keeping economics attractive. And when advisors start comparing platforms, they feel that difference in their workflows, client experience, and support.

Cash Sweep Economics

Cash sweep programs are a clean example of how platform economics can turn “idle” assets into a meaningful revenue stream.

Clients hold cash for all sorts of reasons: waiting to invest, receiving dividends, planning for expenses, or simply keeping liquidity. LPL automatically sweeps that cash into bank deposits and money market funds. Those sweep destinations pay LPL based on prevailing rates. LPL pays clients a rate as well, typically lower than what LPL receives. The spread is income to LPL.

In a low-rate world, there isn’t much spread to earn. But as rates rose substantially after 2022, the economics changed quickly. Cash that used to be a rounding error became real earnings power.

The trade-off is sensitivity. If rates fall, that income can compress even if the core advisory business is still growing. So investors can’t evaluate LPL without understanding that interest income is both a tailwind at times and a source of volatility.

Regulatory Moat and Compliance Infrastructure

For a scaled broker-dealer, compliance isn’t just a cost center. Done well, it becomes a moat.

The regulatory surface area is huge: FINRA supervision, SEC rules, state requirements, anti-money laundering monitoring, recordkeeping, ongoing training, and the reality that examinations and enforcement are part of life at scale.

Building the infrastructure to handle that—systems, people, processes, and legal support—takes serious investment. Smaller firms face a brutal math problem: many compliance costs don’t scale down gracefully. When you spread those fixed burdens across fewer advisors, the cost per advisor rises, and capabilities often get thinner.

That pressure is one reason consolidation keeps happening. Regulation doesn’t just punish bad behavior. It rewards scale.

Network Effects and Switching Costs

Finally, LPL benefits from two reinforcements that don’t show up cleanly on an income statement: network effects and switching costs.

Network effects show up in recruiting momentum. Advisors talk. If a platform is working, satisfied advisors refer peers and former colleagues. The bigger and more established LPL becomes, the more it benefits from that social proof.

Switching costs are more operational. Once an advisor’s practice is built around LPL—its systems, workflows, integrations, and service model—moving isn’t just signing a new contract. It’s migrating data, retraining staff, rebuilding tech connections, and managing client disruption. That friction makes advisors more likely to stay, even when competitors come with compelling offers.

Put it all together, and the model becomes clearer: LPL’s leadership isn’t just a function of being early. It’s reinforced by scale economics, regulatory complexity, and the reality that in financial advice, the platform you build your practice on becomes part of the practice itself.

IX. Playbook: Lessons for Builders

LPL’s path from two scrappy, anti-wirehouse upstarts to a Fortune 500 platform isn’t just a finance story. It’s a repeatable playbook for how platform businesses win: disrupt from the flank, build the marketplace, use capital to reach scale, consolidate a fragmented field, and treat regulation as something you can master—not something you merely endure.

Disrupting from Below

The independent model didn’t try to beat wirehouses at their own game. It didn’t attempt to out-brand Merrill Lynch or out-research Wall Street. Instead, it competed on a dimension the incumbents were structurally bad at: genuine independence and practice ownership.

That’s disruption from below. LPL and the independent channel served advisors—and ultimately clients—who were undervalued by the dominant model. Wirehouses were built to capture advisor production and control the client relationship. Real independence would have meant giving up control, and with it, a meaningful part of the economics. So the big firms had every incentive to dismiss the movement as smaller, scrappier, and lower-end—until it grew large enough to pull in the very advisors they most wanted to keep.

The takeaway for builders is simple: don’t attack the incumbent where it’s strongest. Find the place it can’t go without breaking itself.

Building Two-Sided Marketplaces

Under the hood, LPL is a two-sided marketplace. On one side are advisors. On the other is the infrastructure that makes their practices run—custody, compliance, technology, research, and service. The more advisors the platform supports, the more it can invest in the infrastructure. The better the infrastructure gets, the easier it is to attract the next wave of advisors.

That flywheel sounds obvious once it’s spinning. The hard part is getting it started.

Two-sided marketplaces have a classic chicken-and-egg problem: you need participants to justify investment, and you need investment to attract participants. LPL’s solution was to begin with advisors who wanted independence badly enough to tolerate early limitations, then steadily reinvest platform revenue into capabilities that made the offering more complete—and therefore more attractive to a broader set of advisors.

And once you hit enough scale, platform economics start to dominate. Fixed costs—technology builds, compliance programs, integration capacity—spread across a larger base. Unit economics improve. The product gets better faster. And competitors without scale start to feel permanently behind. LPL’s private equity era poured fuel on exactly that moment: reaching the scale where the platform could compound.

PE to Public Markets Transition

LPL’s time in private equity shows how PE can act like an accelerator for platform businesses—when the fit is right. The firms brought not just capital, but operational discipline and experience scaling through acquisitions. That enabled LPL to grow faster than organic recruiting alone likely could have.

But getting from “scaled private platform” to “public company” is its own project. LPL had to build the systems for quarterly reporting, strengthen controls to meet public-company standards, and evolve governance to satisfy institutional investors. That work takes time and real investment. The payoff was an IPO that delivered liquidity and, just as importantly, a public currency that could support future growth.

If you’re a builder considering private equity, LPL’s story points to a practical filter: the best partners bring capabilities, not just checks. The wrong partner doesn’t merely slow you down—it can pull the company off its cultural and strategic foundation.

Roll-Up Strategy in Fragmented Industries

Independent broker-dealers were a classic roll-up opportunity: hundreds of firms, many too small to keep up with rising technology expectations and regulatory demands. LPL’s strategy was to consolidate that fragmentation into a scaled platform with real advantages—better infrastructure, more efficient economics, and a stronger recruiting position.

But roll-ups aren’t “buy and win.” They’re “buy and integrate.” Success depends on the ability to absorb firms without destroying what made them valuable—keeping advisors confident, migrating technology without chaos, and maintaining service levels through the transition. LPL built that integration muscle over time, learning with each deal what it took to retain advisors and stabilize operations.

Roll-ups also require patience. The benefits of consolidation don’t always show up immediately, and the integration work can be messy. The winners are the ones with aligned expectations—management and investors who understand the time horizon from fragmented acquisitions to durable scale.

Balancing Growth with Regulatory Compliance

Financial services is a regulatory obstacle course, and it’s one where shortcuts tend to show up later as existential problems. LPL’s growth happened inside that constraint, and one of its more important strategic choices was to treat compliance as a capability, not a tax.

That framing matters. If you view compliance as a cost center to minimize, you end up underinvesting in supervision, systems, and training—and eventually you pay for it in distractions, settlements, reputational damage, or worse. If you view compliance as something you can get great at, it becomes an advantage: a reason advisors join, a reason regulators trust your controls, and a burden smaller competitors can’t spread efficiently.

For builders in regulated industries, the lesson isn’t “love regulation.” It’s: respect it early, invest ahead of the minimum, and turn expertise into part of the product.

X. Bear & Bull Case Analysis

To evaluate LPL honestly, you have to be able to hold two ideas at once: there’s a very real case that its platform keeps getting stronger, and there are equally real risks that could interrupt—or even reverse—that compounding. The best investors don’t pick a side and root. They weigh what has to go right, what can go wrong, and how quickly each scenario could show up in the numbers.

The Bull Case

The bull case starts with scale—and not the hand-wavy kind. LPL’s size creates practical advantages that show up in day-to-day execution: it can spread technology spending across a larger advisor base, absorb compliance and supervision costs more efficiently, and negotiate from a position of strength with vendors and partners. As the platform grows, those advantages tend to compound, because the fixed-cost parts of the business don’t rise linearly with advisor count.

Then there’s the tailwind that makes scale even more valuable: the secular shift toward independence. Advisors keep leaving wirehouses in search of ownership, flexibility, and fewer product-driven constraints. LPL captures an outsized share of that migration. And as the independent channel becomes mainstream, the old stigma of “going independent” fades, widening the recruiting funnel even further.

The next leg is consolidation. The independent broker-dealer landscape remains fragmented, with hundreds of smaller firms still in the market. Many of them face the same squeeze: clients want better tech, regulators demand more oversight, and the cost of keeping up keeps rising. LPL has the capital, the integration muscle, and the operating model to keep buying and absorbing that fragmentation—adding scale while shrinking the competitive set.

Finally, there’s operating leverage. As LPL’s technology matures and advisor density increases, each incremental dollar of platform investment can support more revenue. Automation can reduce manual work. Standardized workflows can lower servicing costs. If that plays out, earnings can grow faster than revenue—not because the company “cuts its way to growth,” but because a scaled platform naturally becomes more efficient over time.

If you view it through a Porter’s Five Forces lens, a lot of the structure is favorable. Supplier power is limited because LPL is large enough to have leverage. Buyer power is fragmented because individual advisors typically can’t dictate terms the way a single mega-client could. Substitutes like robo-advisors don’t perfectly map to LPL’s core market. And new entrants face steep barriers: regulation, technology, and the slow work of earning advisor trust.

Under Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, LPL shows multiple “powers” at once. Scale economies appear in tech and compliance. Switching costs show up in how deeply advisors build their practices on LPL’s systems. Counter-positioning helped protect LPL from wirehouses that couldn’t fully embrace independence without undermining their own economics. Network effects show up in advisor referrals and recruiting momentum.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts where it almost always starts in financial services: regulation. Broker-dealers operate in a world where rules evolve, enforcement priorities shift, and supervision mistakes can become very expensive very quickly. A major regulatory action—whether a large penalty, a consent order, or operational restrictions—could hit both reputation and economics, and distract management at exactly the wrong time.

Next is fee compression. For decades, the industry has seen downward pressure on what clients pay as competition increases and technology makes basic services cheaper. If that trend accelerates, LPL could find itself growing assets without seeing the same growth in revenue per advisor.

Then there’s the direct-to-consumer threat. LPL is not built to compete head-on with a robo-advisor for entry-level accounts, but the risk isn’t the bottom of the market—it’s whether technology-driven platforms move upmarket. If digital alternatives become good enough for more affluent clients, they could pressure the broader human-advice model that LPL’s platform depends on.

Interest rates are another source of volatility. LPL’s cash sweep income rises and falls with rate levels. If rates decline meaningfully, that revenue can compress even if advisor count and assets keep growing, creating a gap between “the business is healthy” and “the earnings look weaker.”

And finally, the incumbents fight back. Wirehouses have every incentive to slow defections, and they’ve intensified retention efforts with better payouts, equity participation, and improved technology. If those tactics work, LPL’s recruiting momentum could soften—particularly among the highest-producing advisors.

Key Metrics to Track

If you want to keep score without getting lost in every headline, three indicators do most of the work:

Advisory and Brokerage Assets — The base layer of the whole platform. More assets generally means more advisory fees, more platform-related revenue, and a larger pool of client cash that can generate interest income. If this number is consistently growing, the engine is still running.

Net New Assets — The flow metric that reveals whether LPL is actually winning the fight for assets. Strong net new assets usually reflect a mix of recruiting, advisors bringing over client relationships successfully, and existing clients adding money. Weak or negative net new assets can be an early warning sign that competition is biting.

Advisor Count and Productivity — Growth in advisors matters, but so does what those advisors produce. Watching advisor count alongside assets and revenue per advisor helps separate “bigger” from “better.” Healthy platform economics typically look like advisor growth with stable or improving productivity—while declining productivity can signal fee pressure, competitive intensity, or a platform that’s falling behind on technology and service.

XI. Power & Strategy Assessment

Step back from the headlines and run LPL through the classic strategy frameworks, and a clear picture emerges: its advantages aren’t trendy. They’re structural. And they’ve been accumulating for decades in ways that are hard for competitors to copy quickly—even if they have money and motivation.

Scale Economies in Technology and Compliance

LPL’s biggest costs are also the ones that scale best: technology and compliance.

Building and maintaining a modern advisor platform is expensive whether you serve 5,000 advisors or 20,000. But the revenue that platform generates rises with every additional advisor and dollar of client assets. That’s the math that makes LPL tough to chase: once the core systems are built, the cost per advisor tends to fall as the base grows.

The same dynamic shows up in compliance. If you have the supervision, monitoring, and training infrastructure to support roughly 17,500 advisors, you can often support meaningfully more without anything close to a one-for-one increase in cost. And each year of operating at scale adds something else that’s difficult to buy: institutional muscle memory. The exams you’ve lived through, the edge cases you’ve handled, the patterns you’ve learned to spot before they become problems.

Network Effects in the Advisor Platform

LPL also benefits from a softer—but very real—kind of network effect: advisor-to-advisor momentum.

When advisors thrive on a platform, they talk. They pull in former colleagues. They recommend it to friends weighing a move. LPL can encourage referrals, but it doesn’t have to manufacture them—satisfied advisors naturally become a distribution channel.

There’s also a credibility loop at work. Prospective recruits don’t just ask what the platform says about itself. They look at who’s already there. A roster full of strong advisors serves as validation that the platform is legitimate, durable, and worth betting a career on. Each high-quality recruit improves the platform’s perceived quality, which makes the next recruit easier. Competitors trying to break that cycle face a frustrating problem: they need scale and quality at the same time.

Switching Costs for Advisors and Institutions

Even though LPL’s whole origin story is about independence, the day-to-day reality is that platforms create gravity.

Once an advisor builds a practice on LPL’s systems—workflows, integrations, reporting, service model—moving isn’t just picking a new payout grid. It’s rebuilding the operating system of the business: retraining staff, migrating data, reworking client communications, and updating regulatory and account paperwork.

Those switching costs don’t make departures impossible. Advisors do leave. But friction changes behavior at the margin. It lowers the odds of an impulsive move and raises the price a competitor has to pay to make switching feel worth the disruption.

Brand and Trust in the Independent Channel

LPL’s brand isn’t built for the general public the way the wirehouses’ brands are. It’s built where it matters for this business: inside the independent advisor community.

For advisors considering a leap, LPL is often the “proven path”—a platform with longevity, scale, and a track record of supporting independence. That reputation makes the decision feel less like a gamble and more like a professional, defensible choice.

And it spills over to clients. Many clients don’t choose LPL directly, but they do care about what sits behind their advisor. Size and longevity reduce the fear that an “independent” practice is fragile. Being the largest independent broker-dealer can function as reassurance that the platform is stable and likely to be there for the long haul.

Counter-Positioning vs. Wirehouses

Finally, LPL still benefits from one of the most durable strategic positions in the whole story: counter-positioning against the wirehouses.

To truly match LPL’s value proposition, a wirehouse would need to offer real independence—practice ownership, portability, open architecture—at the core, not as a marketing overlay. But the more they do that, the more they undermine the economics and control their model is built on.

Wirehouses can, and do, respond with hybrid models and richer retention packages. They can copy pieces. What they can’t do—at least not without cannibalizing themselves—is fully become what LPL already is. That structural constraint is part of why the independent channel kept growing, and why LPL’s position inside it has remained so hard to dislodge.

XII. Recent Developments

The biggest headline in the most recent chapter is still the one we ended on: LPL’s planned acquisition of Commonwealth Financial Network, announced in late 2024. On paper, it’s straightforward—roughly 3,000 advisors and about $305 billion in assets coming onto the LPL platform. In reality, it’s a high-stakes continuation of the consolidation strategy that’s powered LPL for decades, with a very specific challenge attached: Commonwealth’s reputation is built on a distinctive, high-touch service culture, and integrating that into a much larger platform is as much about feel as it is about systems.

Underneath the M&A, the day-to-day arms race hasn’t slowed. LPL has kept investing in technology—upgrading digital platforms and advisor tools—because in today’s market, “independence” isn’t the differentiator by itself. The differentiator is whether independence comes with a modern operating system that makes an advisor and their staff faster, more compliant, and easier to do business with.

That matters because recruiting remains the heartbeat of the story. LPL has continued to position itself as a landing spot for advisors leaving wirehouses, even as wirehouses have fought harder to keep their best people with richer retention offers and improved resources. The competitive tug-of-war has intensified, but the underlying migration toward independence has continued to feed LPL’s growth.

Macro has played a role too. Higher interest rates have been a tailwind for cash sweep revenue, turning client cash balances into a more meaningful earnings lever. But that benefit comes with an asterisk: the direction of rates is uncertain, and a different rate environment can change the shape of the income statement even if the platform itself is still doing its job.

LPL has also stayed active in political advocacy, continuing efforts to represent independent advisors in Washington and engage with regulatory conversations that could reshape how advice is delivered and supervised.

Zooming out, the market-share story has remained consistent with the broader thesis: LPL has continued to extend its lead in the independent broker-dealer space, and the distance between LPL and smaller competitors has tended to widen. The reason is the same one that’s been driving the plot for years—technology and regulatory costs don’t scale down well, and smaller broker-dealers keep getting squeezed. In that environment, the platform consolidation playbook still looks very much alive.

XIII. Sources & Resources

Company Filings and Investor Materials - LPL Financial Holdings Inc. Annual Reports (Form 10-K) - LPL Financial Holdings Inc. Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q) - LPL Financial Holdings Inc. Investor presentations - LPL Financial Holdings Inc. earnings call transcripts - SEC EDGAR filings for LPLA

Industry Analysis - Financial Planning Association industry research - Investment News broker-dealer surveys and rankings - InvestmentNews annual broker-dealer ranking reports - Cerulli Associates wealth management industry analysis - McKinsey & Company wealth management reports

Historical Resources - LPL Financial corporate history publications - Industry coverage on the evolution of independent broker-dealers - Research on the rise of fee-based advisory models - Analysis of wirehouse-to-independent transition trends

Regulatory Resources - FINRA regulatory notices and guidance - SEC enforcement actions and releases - Department of Labor fiduciary rule history and analysis - State securities regulatory frameworks

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music