Microchip Technology: The 100+ Quarter Profit Machine

I. Introduction & Cold Open

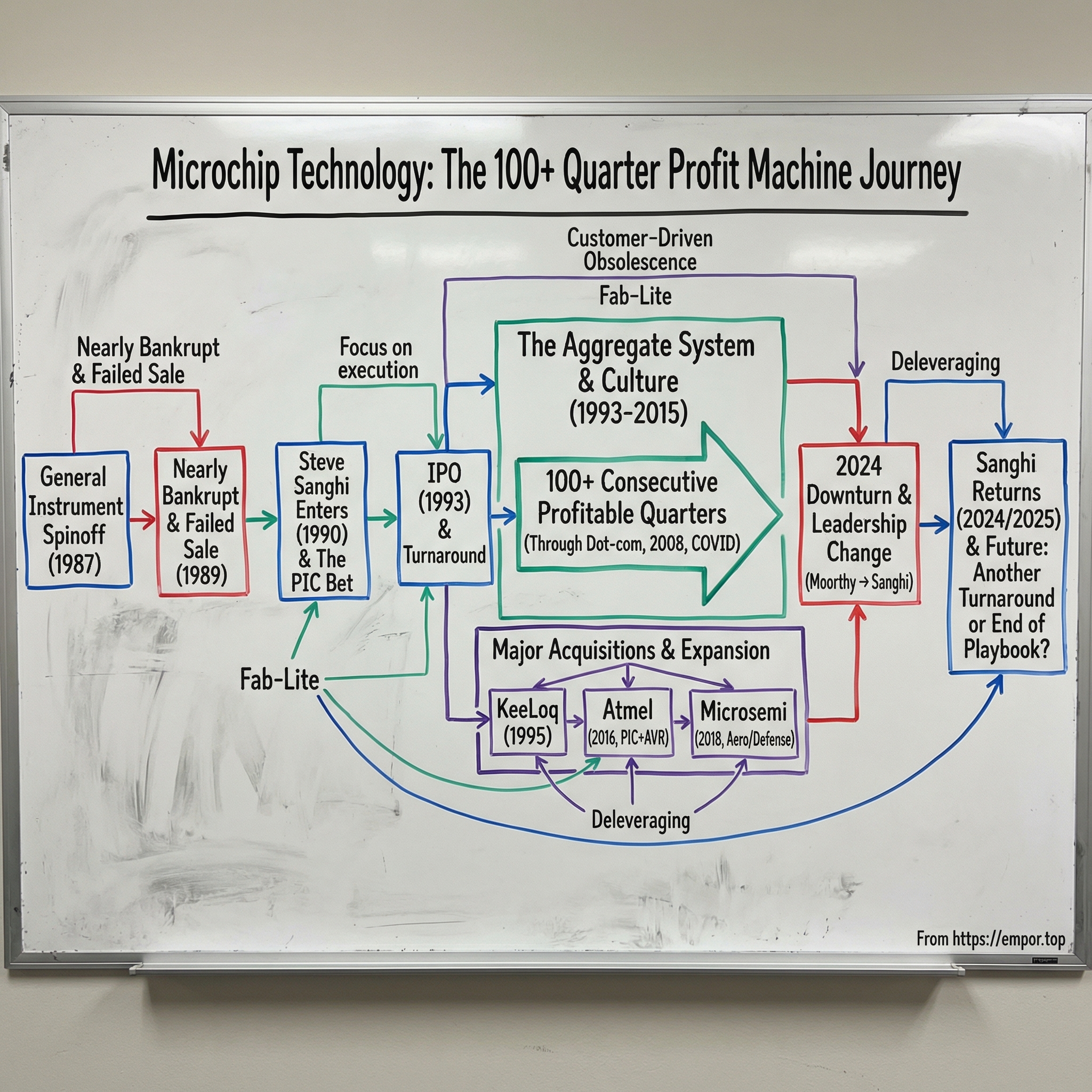

Here’s a riddle for the semiconductor faithful: what chip company delivered 121 consecutive profitable quarters through the dot-com bust, the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-era supply chain shock, and every brutal downturn in between?

It isn’t Intel. It isn’t Texas Instruments. It isn’t one of the names most investors reflexively reach for.

It’s Microchip Technology: a Chandler, Arizona company that many people have never heard of, even though its tiny chips are everywhere—inside car key fobs, garage door openers, factory robots, and medical devices.

Microchip’s rise is one of the most unlikely turnarounds in the industry. In 1989, it was a newly independent castoff from General Instrument—bleeding cash, running on less than six months of runway, and selling a mix of products that wasn’t exactly setting the market on fire. At one point, the whole company nearly sold to a Taiwanese buyer for about fifteen million dollars… and then the deal fell apart at the last moment.

That’s when Steve Sanghi walked into the story: an immigrant engineer from Punjab who’d climbed the ranks at Intel and showed up with a deeply contrarian idea of what a semiconductor company should be.

Over the next three decades, Sanghi turned Microchip from distressed spinoff to a roughly forty-four-billion-dollar powerhouse. The company leaned into its PIC microcontroller franchise—shipping its billionth unit in 2013—then stacked on new capabilities through acquisition after acquisition, including Atmel and Microsemi. And while much of the industry treated parts as disposable, Microchip built a reputation on the opposite promise: if customers designed a chip into their product, Microchip would keep making it. Sometimes for twenty or thirty years.

Then, in 2024, the machine started to sputter. Revenue dropped sharply. The stock had its worst year since the financial crisis. And Sanghi—who had handed the CEO job to his successor in 2021—came out of retirement at sixty-nine to take the corner office again.

So now the question is the one that makes this story feel less like history and more like a live experiment: is this the start of one more classic Sanghi turnaround, or is it the moment the Microchip playbook finally stops working?

This is the story of how a near-bankrupt spinoff became one of the semiconductor industry’s most consistent wealth creators—and what happens when the architect returns to try to save the legacy one more time.

II. Origins & The General Instrument Spinoff

Microchip’s story starts back when the semiconductor industry still felt like the Wild West—when big conglomerates collected chip divisions, then tossed them aside the moment the cycles turned. One of those conglomerates was General Instrument Corporation, a Pennsylvania electronics company best known for cable TV gear and defense work. Over the 1970s, General Instrument assembled a microelectronics division that built programmable memory, digital signal processors, and a quirky little chip called the PIC—short for “Programmable Interface Controller.”

General Instrument introduced the PIC in 1976 as a helper for its CP1600 microprocessor. That’s the key point: the PIC wasn’t designed to be the brains. It was designed to do the boring, essential stuff—simple input and output—so the main processor could focus on “real” computing.

But engineers loved it precisely because it didn’t try to be everything. It was simple. It used a reduced instruction set. It sipped power. And it could be cheap enough to drop into products where a full microprocessor would be absurd. Inside General Instrument, nobody treated that as destiny. It was just a useful peripheral chip. No one was planning a multi-billion-dollar company around it.

By the mid-1980s, General Instrument had bigger priorities and less patience for the chip business. Semiconductor markets were volatile, capital-hungry, and unforgiving—exactly the opposite of what a company focused on cable television and defense electronics wanted to spend its time on. So in 1987, General Instrument carved out the microelectronics division and spun it into a wholly owned subsidiary: Microchip Technology, based in Chandler, Arizona. On paper, it was a real company. It sold programmable non-volatile memory, microcontrollers, digital signal processors, and consumer ICs to whoever would buy them.

In reality, Microchip still needed the one thing every would-be independent chipmaker needs: capital.

The plan was to go public and raise it. An IPO was teed up for late October 1987.

Then October 19 happened—Black Monday. The Dow plunged 22.6 percent in a single day. The IPO market didn’t just cool off; it froze solid. Microchip’s offering was dead on arrival, and the new subsidiary was left stranded: structured like an independent company, but without the financial oxygen to operate like one.

For almost two years, it limped along under General Instrument’s umbrella, stuck in an awkward in-between state—unable to access public markets and without the freedom, or the funding, to invest its way into a stronger product position. By early 1989, General Instrument was ready to be done. It found a buyer: a venture consortium led by Sequoia Capital. On February 14, 1989—Valentine’s Day—the deal closed. Sequoia and its partners put in twelve million dollars of Series A funding, and Microchip became independent for real.

Independence, though, didn’t magically fix the business. Microchip’s revenue mix was brutal. About sixty percent came from components sold into the disk drive industry—famously cyclical, cost-sensitive, and quick to punish suppliers. Much of the rest came from commodity EEPROM memory, a category where Asian manufacturers were relentlessly pushing prices down. And the one product that could have been special—the PIC microcontroller—wasn’t being developed or sold like a franchise. Microchip had a small lineup of 8-bit devices rooted in the original General Instrument design, but it didn’t have the engineering depth or marketing heft to go toe-to-toe with Motorola, Intel, and the Japanese powerhouses that owned the microcontroller conversation.

Then the floor fell out.

Within months of Sequoia’s investment, the disk drive market hit one of its regular slumps. Orders dried up. Cash burned. By early 1990, Microchip had consumed ten million of the twelve million it had raised. The investors wouldn’t put in more. Credit lines were tapped out. And at roughly two and a half million dollars of losses per quarter, the company had less than six months of runway left.

So the board did what boards do in a crisis: it looked for an exit.

A Taiwanese company, Winbond Electronics, offered to buy Microchip for fifteen million dollars—barely above the venture money that had just gone in, and a rounding error for a business with manufacturing assets and at least the outline of a potentially valuable product line. Sequoia didn’t love it, but it was hard to argue with arithmetic. A deal beat a liquidation.

And then, almost as quickly, the deal evaporated. The Taiwanese stock market crashed, and Winbond walked away.

Microchip had been spared, basically by chance. But what came next wasn’t chance. What came next was an engineer named Steve Sanghi—someone who looked at this mess and saw not a dead-end spinoff, but a company that could be rebuilt around a very different idea of how semiconductors should be made, sold, and supported.

III. The Sanghi Era Begins: Crisis & Turnaround (1990-1993)

Picture a small conference room in Chandler, Arizona, in the spring of 1990. The air conditioning fights the desert heat. Around the table, a handful of exhausted executives stare at projections that all point to the same conclusion: in a few months, the money is gone.

Sequoia and the other investors have stopped engaging. The Taiwanese buyer who was supposed to save everyone has walked. Someone cracks a dark joke about polishing a resume.

That’s what Steve Sanghi walked into at Microchip Technology: a company that wasn’t just struggling—it had started to accept the idea that it might not survive.

Sanghi’s story didn’t begin in Silicon Valley. He was born on July 20, 1955, in Sri Muktsar Sahib, a town in Punjab near the Pakistani border. His father was a judge, and his family pushed education hard. Sanghi did what ambitious engineers in India did in that era: he earned his way into one of the country’s top pipelines, graduating from Punjab Engineering College in 1975 with a degree in electronics and communication engineering.

Then he aimed at the U.S. He enrolled at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and earned a master’s in electrical and computer engineering. By 1978, at twenty-three, he landed at Intel as an entry-level engineer.

Intel at the time was the place you went to learn how the modern semiconductor industry was being built—how chips were designed, manufactured, priced, and sold at scale. Sanghi soaked up the mechanics and, just as importantly, the discipline. He moved through engineering and management roles and eventually ran Intel’s Programmable Memory Operations.

That job wasn’t glamorous. Programmable memory was a brutal business, squeezed by competitors who lived on thin margins and constant price pressure. But it was an education in something Sanghi would later treat like a superpower: how to make money in an environment where the product itself didn’t automatically guarantee it. Cost structure, yield, execution, customer relationships—those were the levers.

In 1988, he left Intel to become vice president of operations at Waferscale Integration, a smaller company focused on EPROM and flash memory. It was a step toward running an entire enterprise, but Waferscale had the same structural problem as much of the memory market: limited differentiation and relentless pressure. So when a headhunter called in early 1990 about a troubled company in Arizona, Sanghi listened.

The pitch should have been a warning label. Microchip was bleeding cash. Investors were done. The fallback sale had collapsed. Most people looking at the situation saw a company in its final chapter.

Sanghi saw a single line item that might be a beginning: the PIC microcontroller.

In 1990, conventional wisdom said the future belonged to powerful 32-bit microcontrollers—more performance, more features, more complexity. The industry loved big chips with big price tags. Sanghi’s instinct went the other direction. He believed the real volume would come from cheap, simple, low-power microcontrollers embedded in everyday products: appliances, industrial equipment, automotive accessories, little devices that didn’t need horsepower. They needed reliability, low cost, and battery life.

The PIC’s stripped-down 8-bit RISC architecture fit that world. What it didn’t have was a company organized to turn it into a franchise.

Sanghi joined Microchip in April 1990. By August, he was president. In 1991, he became CEO. He was thirty-five, taking over a business many expected to disappear.

The first phase was triage. Costs came out. Unprofitable lines were cut. Contracts got renegotiated. But Sanghi wasn’t under the illusion that expense reduction could create a future. The company needed a clear bet, and he made it: move away from commodity memory and disk-drive components and build Microchip around the PIC.

That same year, Microchip introduced a family of small, inexpensive 8-bit RISC microcontrollers priced at $2.40. In a market where RISC often meant pricey 32-bit devices aimed at high-end systems, it was a provocation. Sanghi wasn’t chasing the prestige segment. He was chasing the world of “good enough,” where millions of products needed a tiny brain and not much else—garage door openers, toothbrushes, sensors, key fobs.

Getting that bet to work took grinding execution. Sanghi lived on the road, pitching customers and distributors on why the PIC was different and why the low end mattered. He pushed engineering to broaden the lineup. He pushed manufacturing to improve yields and keep driving cost down.

And engineers responded. The PIC was simple enough to design in without weeks of headache, and cheap enough that companies could take risks. It lowered the bar for experimentation. It made “add a little intelligence” feel practical instead of extravagant.

Slowly, then all at once, it started to show up everywhere. Design wins accumulated. Sales stabilized, then rose. By 1992, Microchip had reached breakeven. By early 1993, it was producing consistent profits—the kind that felt almost impossible two years earlier.

Then came the moment that locked in the turnaround.

On March 19, 1993, Microchip went public at $13 per share, raising about $50 million—real capital, finally, to invest in capacity and product expansion. But the bigger signal was what happened next. The market treated Microchip less like a rescued spinoff and more like a company that had found a repeatable formula.

Over the rest of the year, the stock climbed more than 500 percent from the IPO price. By year-end, Microchip’s market cap was over a billion dollars. Fortune called it the best-performing IPO of 1993. Analysts who hadn’t bothered to learn the name started initiating coverage. Competitors took the Arizona upstart seriously.

And the contrast was staggering: not long before, this same company had nearly been sold for $15 million.

For Sanghi, the IPO wasn’t a finish line. It was proof of life—and a chance to build something that could survive the cycle. He’d watched what happened to chip companies that lived and died on a single product wave. So the next question wasn’t “how do we ride PIC?” It was, “how do we build an operating system and a culture that keeps winning even when the market turns?”

That’s where the real Microchip story begins.

IV. Building the Aggregate System & Culture (1993-2000)

The 1993 IPO gave Microchip oxygen. But Steve Sanghi knew something that every long-time chip executive learns the hard way: capital doesn’t equal durability.

He’d watched the same movie play over and over. A company gets a hit product, grows like crazy, attracts copycats, gets squeezed on price, then either sells itself or quietly disappears. The semiconductor graveyard was full of once-legendary names—Mostek, Fairchild, Zilog. Sanghi’s obsession wasn’t just getting Microchip to the next quarter. It was making sure it never ended up on that list.

The problem is structural: in semiconductors, technology is a melting ice cube. Today’s breakthrough becomes tomorrow’s commodity. If your only edge is the chip you sell right now, competitors will reverse-engineer it, poach your people, and undercut you. So Sanghi went looking for an advantage that didn’t expire.

His answer was to build a company that could improve continuously—new products, better costs, tighter execution, stronger customer support—year after year. Not as a series of disconnected initiatives, but as a system.

He partnered with Michael Jones, Microchip’s vice president of human resources, and together they built what they called “The Aggregate System.” The name was intentionally plain. It wasn’t the Sanghi Method or a consulting-firm trademark. It was “Aggregate” because the whole point was progress in aggregate—across every function at once. Getting great at manufacturing while sales stumbled, or pushing R&D while operations fell behind, didn’t create a stronger company. It just shifted the weak spot.

The Aggregate System aligned employees around shared goals and created feedback loops that kept pressure on the organization to get better. It wasn’t a rigid playbook with a thousand checkboxes. It was a philosophy—something you could apply in engineering, in customer support, in factory operations, in finance—without turning the company into a bureaucracy.

At the center of it was culture, but not culture as posters on the wall. Sanghi codified a set of principles and then embedded them into how Microchip actually operated: success, inclusion, shared rewards, innovation, trust, and communication. Hiring. Compensation. Promotions. Day-to-day management. The message was consistent: treat people like partners, give them ownership in outcomes, and create an environment where they can take smart risks without fear.

One of Sanghi’s favorite maxims summed up what he expected from leaders: “When you are successful, look out the window and praise your team. When you fail, look in the mirror and ask what you could’ve done better.” At Microchip, that idea showed up in how rewards were distributed. Bonus programs, stock options, and advancement were structured to share success broadly rather than concentrating it at the top.

And when the cycle turned—as it always does in semiconductors—Sanghi pushed a second, equally important norm: shared sacrifice. Executives took voluntary pay cuts before the company cut deep into the workforce. The point wasn’t symbolism. It was trust. If you want people to commit to the long game, they need to believe leadership is playing by the same rules.

Over time, the payoffs compounded. Microchip earned a reputation as a stable, fair place to build a career in an industry notorious for whiplash. Turnover fell. Know-how stayed inside the building. The company got better at the unsexy stuff that actually decides outcomes in semiconductors: manufacturing discipline, product continuity, and customer relationships that last longer than a single design cycle.

While the culture hardened into something distinct, Sanghi also shaped a business model that made Microchip feel different from most chip companies. Three principles drove it.

First: don’t bet the company on one “killer app.” The disk drive crash had nearly killed Microchip in 1990, and Sanghi never forgot it. As he liked to say, “We’re not a killer application-dependent company.” Microchip spread itself across industrial, automotive, consumer, computing, and communications. The tradeoff was real: the company wasn’t going to ride the hottest trend to eye-popping growth. But in downturns, diversification acted like ballast.

Second: be fab-lite, but opportunistic. Chip companies tend to pick a lane—either fabless, outsourcing everything, or fully integrated, owning massive fabrication plants. Sanghi chose a middle path: keep a handful of smaller, specialized facilities where control mattered, and use outside foundries where flexibility mattered more. That gave Microchip leverage—some control over its destiny, without the crushing capital requirements of trying to stay on the bleeding edge.

And Sanghi had a line that captured the strategy so well it became lore: “We don’t ever build fabs. We buy other people’s mistakes.” When big semiconductor companies overbuilt and then needed to unload capacity, Microchip aimed to be the buyer. The 2002 purchase of a wafer fab in Gresham, Oregon from Fujitsu Semiconductor for over $180 million was a textbook example—Fujitsu had spent far more to build it, and Microchip picked it up at a distressed price as Fujitsu pulled back.

Third: customer-driven obsolescence. In an industry where suppliers routinely discontinued parts to simplify portfolios, Microchip promised the opposite: it would not end-of-life a product without customer consent. If customers were still ordering a part, Microchip would keep making it—sometimes for decades. In some cases, Microchip talked about product lifetimes of twenty to thirty years, far beyond the typical commitments customers got elsewhere.

This wasn’t charity. It was strategy. Engineers hate redesigns. If you build a chip into a product and it disappears, you eat time, money, and risk. Microchip’s promise created trust, and trust created switching costs. Win the design once, and you could keep it for the life of the customer’s product—especially in industrial, aerospace, and defense markets where lifecycles stretch for years and “stable supply” matters as much as the spec sheet.

By the end of the 1990s, Microchip had become something rare in semiconductors: a company built to be boring in the best way. Not the flashiest, not chasing the highest-end performance crown, but steady—profitable, disciplined, and predictable.

And with that foundation in place, Sanghi was ready for the next phase: using acquisitions to expand what Microchip could offer, without breaking what made it work.

V. Major Acquisitions & Strategic Expansion (1995-2015)

For most of the 1990s, Microchip kept its head down and executed. It broadened the PIC lineup, pushed into more end markets, and kept tightening manufacturing. The chips evolved in very practical, engineer-friendly ways: more memory when software got bigger, built-in analog-to-digital converters when sensors mattered, specialized interfaces when connectivity became table stakes. Each new variant wasn’t just another SKU—it was another set of products Microchip could credibly show up in.

But Sanghi also saw the ceiling. Organic expansion could take you far, but semiconductors rewards scale—and the industry was consolidating fast. Bigger rivals could outspend Microchip on R&D, spread manufacturing costs across higher volumes, and walk into accounts with a catalog so broad it naturally pulled in more business. If Microchip wanted to keep pace with companies like Texas Instruments and Analog Devices, it needed a second engine: acquisitions that added capability around the microcontroller, without breaking the discipline that made Microchip work.

The first meaningful proof point arrived in 1995, when Microchip bought the KeeLoq “code hopping” technology for ten million dollars. It was small by later standards, but it set the template: find a specialized technology that makes the core franchise more valuable, pay a rational price, then integrate it tightly.

KeeLoq came out of South Africa—developed by Frederick Bruwer of Nanoteq, with a cryptographic algorithm created by Gideon Kuhn at the University of Pretoria. And it solved a painfully real problem in early remote keyless entry. The first generations of car key fobs often used fixed codes—the same signal every time. Thieves didn’t need Hollywood hacking skills; they could capture the code once and replay it later.

KeeLoq changed that by making the code move. Every button press generated a new transmission based on a cryptographic algorithm. The car’s receiver knew how to validate it, but anyone intercepting the signal would record a one-time code that wouldn’t work again. Suddenly, remote entry was secure enough to scale into mass-market automotive programs.

And because it fit so naturally next to Microchip’s microcontrollers, the technology spread quickly. Within a few years, KeeLoq-enabled chips were showing up not just in key fobs, but in garage door openers and building access systems too. In 1996, Microchip introduced an enhanced version with 60-bit encryption, extending the lead.

Through the 2000s, Microchip kept doing deals in that same spirit—tuck-ins that broadened the portfolio without changing the company’s personality. But by 2012, the backdrop had shifted. Consolidation was accelerating, and staying “small and excellent” wasn’t a safe strategy. Microchip needed to scale—or risk becoming a niche supplier in a world dominated by giants.

So in 2012, Microchip moved fast, closing three major acquisitions in short order. Ident Technology AG, in Germany, added capacitive sensing expertise. Roving Networks, from Los Gatos, brought low-power embedded Wi‑Fi and Bluetooth designed for smartphones running iOS and Android. And then came the biggest step yet: Standard Microsystems Corporation, or SMSC, in a $939 million all-cash deal. SMSC expanded Microchip into USB connectivity, automotive networking, wireless audio platforms, and thermal management.

That SMSC purchase was a tell. This wasn’t just “more PIC.” Sanghi was building outward—toward a broader analog and mixed-signal platform that could stand in the same conversations as Texas Instruments and Analog Devices.

The next leap reinforced that direction. In 2015, Microchip bought Micrel for $839 million. Micrel specialized in analog and mixed-signal chips—the parts that sit at the boundary between digital logic and the physical world. The strategy was simple: microcontrollers rarely win alone. They need power management, signal conditioning, drivers, and interfaces around them. By owning more of that surrounding circuitry, Microchip could offer more complete designs—and make it easier for engineers to standardize on Microchip across the whole bill of materials.

By mid-2015, Microchip had grown well beyond a single-franchise microcontroller story, becoming a more diversified semiconductor supplier with annual revenue approaching three billion dollars and a market cap in the tens of billions. Just as importantly, Sanghi had shown something many acquirers never manage: Microchip could buy businesses, integrate them, and still protect the culture and operating discipline that made the company durable.

But the truly transformational bets were still ahead. In 2016 and 2018, Microchip would swing at two mega-deals that reshaped the company—and put the Aggregate System to its hardest test yet.

VI. The Atmel Acquisition: Changing the Game (2016)

In embedded engineering, few debates were as tribal as PIC versus AVR. These were the two dominant 8-bit microcontroller families, and their fans argued instruction sets, toolchains, and performance like sports radio callers. Forums were full of flame wars. Students picked a side in school and carried it into their careers. And behind the chips sat two companies that fought hard for the same design wins: Microchip and Atmel.

Atmel was, in many ways, Microchip’s opposite. Founded in 1984 by former Intel engineer George Perlegos, it grew up in Silicon Valley with a reputation for innovation and a more “Valley” posture. Its signature product was AVR, a clean 8-bit architecture created by two Norwegian graduate students, Alf-Egil Bogen and Vegard Wollan, at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. AVR became beloved with hobbyists and educators, and it ended up at the heart of Arduino—the platform that made microcontrollers feel accessible to millions of makers, students, and tinkerers.

Atmel wasn’t just AVR, either. It sold SAM ARM-based microcontrollers for higher-performance needs, touch sensing chips used in smartphones and tablets, and secure wireless products aimed at IoT devices. In other words: it was Microchip’s most direct rival in embedded systems, and in some categories, it looked like the company Microchip might have become if it had chased Silicon Valley style instead of Chandler-style discipline.

For years, the fight was straightforward. Microchip kept gaining with reliability, distribution strength, and its customer-driven obsolescence promise. Atmel stayed relevant on the strength of AVR, Arduino, and a broader “innovation” portfolio—but it struggled to produce the same steady operational consistency. By 2015, Atmel’s results were uneven enough that its board started exploring strategic options.

In September 2015, it looked like the story had already ended. Dialog Semiconductor, a European chipmaker known for power management and connectivity, announced an agreement to acquire Atmel for $4.6 billion. Bankers began mapping out the combination. The market largely treated it as done.

Steve Sanghi didn’t.

From his perspective, Dialog faced an uphill climb. Microcontrollers aren’t a product you simply bolt on; they come with long customer lifecycles, deep toolchain dependence, and engineering relationships that can evaporate if the transition feels sloppy. And for Microchip, Atmel represented something far bigger than a portfolio add-on. Buying Atmel would neutralize its most important competitor in 8-bit microcontrollers and put the PIC and AVR ecosystems under the same roof—something Microchip had wanted, in one form or another, for years.

So in November 2015, Microchip jumped in with an unsolicited counteroffer.

That was a bold move in semiconductors, where “hostile” is almost a dirty word and where employees and customers can punish uncertainty. Dialog pushed back and questioned Microchip’s ability to finance a superior bid. But Atmel’s board had a fiduciary obligation to weigh competing offers, and once Microchip put real terms on the table, the situation became a three-way chess match.

Through the winter of 2015 into 2016, it turned into a bidding and negotiation drama: Dialog sweetened its proposal, Microchip improved its terms, bankers ferried between conference rooms, and Atmel’s directors tried to decide which buyer could both pay and execute.

On January 19, 2016, Microchip prevailed. It announced a definitive agreement to acquire Atmel for $3.56 billion, valuing Atmel at $8.15 per share: $7.00 in cash plus $1.15 in Microchip stock—an 85 percent cash, 15 percent stock mix. Dialog walked away, collecting a breakup fee and losing the prize.

Just like that, the PIC-versus-AVR rivalry was effectively over. The two most popular 8-bit microcontroller architectures would now be owned by the same company.

The deal closed in July 2016. Microchip framed the combined business as “a global leader in microcontroller, analog, touch, connectivity, and memory solutions,” and the description wasn’t marketing fluff. Together, the catalogs covered everything from tiny consumer gadgets to complex industrial systems. Customers who had once had to choose a side could now source both from a single supplier.

What surprised people wasn’t just that Microchip won—it was how well it integrated. On paper, the merger was expected to add about $0.33 per share to Microchip’s fiscal 2017 earnings. In reality, it added $0.69 per share—more than double the forecast. The explanation was classic Microchip: Sanghi’s team found more cost savings than even optimistic models assumed. Redundant operations were consolidated. Overlapping sales efforts were streamlined. Manufacturing was rationalized. The operating discipline that had been built through the 1990s and 2000s showed up, at scale, in the numbers.

Still, the integration couldn’t be handled like a simple takeover. Atmel had its own engineering culture and a fiercely loyal customer base. If Microchip tried to “Chandler-ify” everything overnight, it risked talent flight and customer backlash. So the approach was pragmatic: keep the product lines and engineering continuity customers cared about, while aggressively consolidating back-office functions and cutting redundant overhead.

And then Microchip did the most important thing it could do for trust: it extended its customer-driven obsolescence policy to Atmel’s portfolio. If customers were still building products around parts that had been in Atmel’s catalog since the 1990s, Microchip would keep making them. That one promise calmed a huge fear inside the Atmel ecosystem—that an acquisition would be followed by a wave of end-of-life notices.

On the tools side, Microchip began bringing Atmel Studio—later renamed Microchip Studio—into its broader development environment alongside MPLAB. And for the Arduino community, whose projects depended on Atmel’s ATmega chips, the message was simple: keep building. The parts weren’t going away.

For investors, Atmel was the proof point. Microchip didn’t just buy a competitor. It absorbed a complex Silicon Valley company, hit the synergy targets, and did it without breaking the customer promise that made Microchip different.

And with that win on the board, Sanghi was ready to take an even bigger swing.

VII. The Microsemi Mega-Deal (2018)

If you tried to design a semiconductor company that was Microchip’s opposite, you’d end up with something a lot like Microsemi.

Microchip made its money shipping millions of small, low-cost microcontrollers to a sprawling universe of customers. Microsemi, by contrast, sold fewer parts at much higher prices to a far more concentrated set of buyers—government programs, defense primes, telecom infrastructure players. Microchip built a reputation on frugality and operational discipline. Microsemi carried itself like a company that could charge premium prices because, in many niches, customers didn’t have many alternatives. Microchip’s chips lived in garage door openers and coffee makers. Microsemi’s parts went into satellites, secure communications, and the machinery that keeps networks and data centers running.

And that’s why, after Atmel, Microsemi was the deal that changed what Microchip actually was. Atmel made Microchip even more dominant in embedded. Microsemi pushed it into a different class entirely: a diversified analog and mixed-signal company with real weight in aerospace and defense—markets with sticky customers and product lifecycles measured in decades.

Microsemi traced its roots back to 1960, when it was founded as Pacific Semiconductors. Over time—and through dozens of acquisitions—it evolved into a specialist in high-reliability components for applications where “mostly works” isn’t good enough. Its lineup included radiation-hardened field-programmable gate arrays for space systems, timing and synchronization devices used deep inside telecommunications infrastructure, and power-management products for data centers. These weren’t commodity parts. They were engineered to survive extreme conditions and to be supported for a very long time.

Its customer list reflected that: the U.S. Department of Defense, major aerospace contractors like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, telecom equipment makers and carriers, and operators of critical infrastructure. They cared less about shaving pennies off a bill of materials and more about qualification, traceability, and a supplier that would still be there years later when a program needed spares.

On March 1, 2018, Microchip announced it had reached a definitive agreement to buy Microsemi for $10.3 billion, the largest acquisition in Microchip’s history. In scale, it dwarfed Atmel—nearly three times larger—and it would have been unthinkable back in 1990 when Sanghi walked into a company running out of cash.

The terms were all-cash: $68.78 per share. That translated to an equity value of roughly $8.35 billion and an enterprise value of about $10.15 billion once you included debt. To fund it, Microchip used cash, drew on credit lines, added a new three-billion-dollar term loan, and issued two billion dollars of high-grade secured bonds. It was a serious amount of leverage—one that only works if you can generate cash consistently and integrate without losing momentum.

Shareholders approved. Microsemi’s investors, in particular, voted overwhelmingly in favor—99.5 percent—reflecting both the premium and the logic of the combination. The deal closed in May 2018.

Microchip told the market to expect $300 million in synergies by the third year after closing. The pitch was clean: Microsemi’s presence in aerospace, defense, and data centers would complement Microchip’s strength in industrial and automotive. Together, the company would have one of the broadest analog and mixed-signal portfolios in the industry.

But unlike Atmel, this integration didn’t start smoothly. After closing, Microchip’s team found issues that weren’t obvious from the outside.

First was culture. Microsemi had developed a style that clashed with Sanghi’s worldview. There were lavish executive perks—luxury stadium suites, private plane travel, expensive sponsorships—and a level of overhead that looked excessive for a company of its size. Sanghi later described it as “indulgence and extravagance,” and he wasn’t inclined to tolerate it.

Then there was the business reality hiding inside the numbers. Microchip discovered that Microsemi had pushed product into the channel ahead of the acquisition, using discounts to load distributors with inventory. Revenue looked better; the downstream demand hadn’t actually changed. Once Microchip took over, it inherited a bloated channel—and the hangover that comes with it: quarters of weaker sell-through as inventory normalized.

Sanghi responded the way he usually did in a crisis: fast and direct. Much of Microsemi’s executive leadership was removed, including the entire senior management team. Overhead was cut hard. Microchip’s lean operating model was pushed into Microsemi’s facilities and processes. It wasn’t painless—there were layoffs and consolidations—but Sanghi believed the only way to protect the franchise was to reset the culture immediately.

Over time, the strategic value showed up. Aerospace and defense grew from around eleven percent of Microchip’s revenue to roughly seventeen or eighteen percent as military budgets expanded globally. Demand increased across the U.S., among NATO allies responding to security concerns, and in Asia as countries invested in modernization. And that meant more pull for the kinds of parts Microsemi specialized in: secure microcontrollers, high-reliability power devices, and especially radiation-hardened FPGAs.

Those rad-hard FPGAs were a crown jewel. Space is a brutal environment for ordinary silicon—cosmic rays and solar particles can flip bits and cause failures that aren’t just inconvenient, they’re mission-ending. Satellites, spacecraft, and certain military systems need chips designed specifically to survive that. Very few suppliers can do it well, and for the customers who need these parts, switching isn’t simple—or sometimes even possible.

Microsemi’s timing and synchronization products mattered for a different reason: modern telecom networks, particularly 5G, rely on extremely precise timing. The devices that generate and distribute those timing signals sit deep in the equipment carriers deploy, invisible to most people but essential to keeping networks stable. Microsemi had a strong position there, and it became more valuable as 5G rollouts accelerated.

In a single acquisition, Microchip could now credibly claim a span that sounded almost absurd: everything from a couple-dollar microcontroller in a consumer appliance to a multi-thousand-dollar radiation-hardened FPGA riding on a military satellite. That range wasn’t just bragging rights. It was Sanghi’s long-held diversification thesis made real: don’t depend on one application, one cycle, or one customer type.

But there was no free lunch. The Microsemi deal also pushed Microchip’s debt load to levels it hadn’t carried before. The leverage was manageable as long as cash kept flowing and the cycle stayed reasonable. Through 2019 and into 2020, it looked like the bet was working—revenue grew, margins improved, and debt started coming down.

Then the world changed in ways nobody anticipated.

VIII. Modern Challenges & Leadership Transition (2021-Present)

By the end of 2015, Microchip had hit a milestone that almost doesn’t sound real: one hundred consecutive quarters of profitability.

Not “mostly profitable.” Not “profitable except for the crisis years.” Profitable, every quarter, through the dot-com crash, the financial crisis, and the regular gut-punch downturns that have a habit of wiping out less disciplined chipmakers. The streak ultimately ran to 121 quarters before accounting changes made the apples-to-apples comparison harder. But the point stood: Microchip had built a machine that could survive what usually kills semiconductor companies.

It wasn’t magic. It was the model. Diversification meant a slump in one end market rarely sank the whole ship. Fab-lite operations kept fixed costs from ballooning. When the cycle turned, Microchip’s crisis playbook—executive pay cuts, furloughs instead of mass layoffs, tight inventory management—bought flexibility. And the customer-driven obsolescence promise created a kind of loyalty that doesn’t show up on a datasheet, but absolutely shows up in repeat orders.

In March 2021, after three decades in the CEO seat, Steve Sanghi stepped back. He was sixty-five. He’d taken Microchip from a near-liquidation spinoff to a roughly forty-billion-dollar company. He’d codified his management philosophy into books. He’d built the culture and the system. Now came the question every long-tenured founder-CEO eventually faces: can the company run without him?

Sanghi handed the job to Ganesh Moorthy, a 23-year Microchip veteran and the company’s chief operating officer. This wasn’t an outsider brought in with a “transformation” slide deck. Moorthy knew the products, the customers, and the Chandler way of doing things. Sanghi stayed on as executive chairman, a steady hand in the background.

And at first, the timing looked perfect. The semiconductor world was on fire. COVID-era disruptions collided with a surge in demand—more laptops and networking gear, more automation, more medical devices, more everything. Supply couldn’t keep up. Lead times stretched. Customers got desperate.

Microchip felt that desperation directly. Customers signed take-or-pay contracts—commitments to buy chips even if their own demand softened—because the bigger risk was not getting parts at all. Prices rose. Factories ran hard. Analysts talked like the industry had entered a new, permanently tighter era.

But the boom had a hidden poison: panic ordering.

When customers can’t get supply, they don’t order what they need. They order what they fear they won’t be able to get. Purchasing managers hoarded. Distributors hoarded. Contract manufacturers built buffers. Inventory piled up across the supply chain, often well beyond real end demand.

By mid-2023, when the COVID-era surge peaked and started to roll over, the reckoning arrived fast. The artificial demand disappeared. Customers stopped placing new orders and began living off the stockpiles they’d built. Lead times collapsed. Pricing power went with them.

Microchip got hit especially hard because one of its biggest strengths became a weakness. It was deeply exposed to industrial customers—the workhorse markets of factory automation, building systems, and machinery. Those customers had built enormous buffers during the shortage, and when their own end markets softened, they did exactly what you’d expect: they stopped buying and started burning off inventory.

The drop was brutal. Quarterly revenue, which had peaked at levels approaching two billion dollars, fell by more than half.

Throughout 2024, the slide continued. Revenue fell about forty percent for the year. The stock dropped thirty-five percent, its worst annual performance since the 2008 financial crisis. And unlike competitors with meaningful exposure to AI data center demand, Microchip didn’t have much of an AI-driven tailwind to soften the impact. It was stuck in the ugly part of the cycle.

Moorthy, who had managed the upcycle, couldn’t stop the downcycle. Criticism mounted that Microchip had allowed inventory to build too high, leaned too heavily into peak-era take-or-pay dynamics, and lacked a growth engine like AI to counterbalance the downturn. The board grew uneasy.

In November 2024, Moorthy retired around his sixty-fifth birthday. Sanghi—now sixty-nine—came back from the chairman role to serve as interim CEO and president.

The turnaround artist was back in the building.

He didn’t ease into it. In December 2024, Sanghi announced the closure of Fab 2, Microchip’s manufacturing facility in Tempe, Arizona. The shutdown, expected to be completed by September 2025, would affect about five hundred employees and was projected to generate roughly ninety million dollars in annual cash savings. Production would be shifted to Microchip’s facilities in Oregon and Colorado.

Then came the more surprising move: Sanghi paused Microchip’s application for $162 million in CHIPS Act grants, funding the company had sought for expansions in Oregon and Colorado. The CHIPS Act was designed to subsidize U.S. semiconductor manufacturing, and most companies were chasing every dollar they could get. Microchip became the first known company to voluntarily step back.

Sanghi’s logic was straightforward. Those expansions made sense when the industry believed it was short on capacity. By late 2024, the problem wasn’t shortage. It was excess. Taking government money to add capacity you didn’t need—and might not utilize—wasn’t disciplined. It was just optics.

Through the first half of 2025, Sanghi rolled out what he called a nine-point recovery plan. The priorities were the ones you’d expect from Microchip: drive down inventory, protect margins, restore operational discipline. The company worked with distributors and direct customers to clear excess channel stock. It trimmed operating expenses. And it leaned into aerospace and defense, where demand held up better thanks to elevated military budgets.

On July 2, 2025, Microchip’s board made the return official: Sanghi would remain CEO and president permanently, not just as an interim fix. Lead independent director Matthew Chapman said the board was “delighted” that Sanghi had agreed to stay on.

By the end of calendar 2025, there were real signs the cycle was turning. Fiscal third quarter 2026 results, announced in December 2025, reported net sales of $1.186 billion—up four percent sequentially and nearly sixteen percent year-over-year—and above Microchip’s guidance range of $1.109 to $1.149 billion. Management pointed to broad-based improvement across end markets, with the inventory correction advancing at both distributors and direct customers.

Microchip had now logged 141 consecutive quarters of non-GAAP profitability—keeping the streak alive through what it described as the worst downturn in fifteen years. The old playbook, it appeared, still worked.

But the company also faced a new kind of question. Not whether Sanghi could engineer another recovery—he’d done that before—but whether a seventy-year-old CEO could build the next generation of leadership, and whether this rebound would be more than just the cycle turning back in Microchip’s favor.

IX. Playbook: The Microchip Way

Strip away the big acquisitions and the quarter-by-quarter drama, and Microchip’s durability comes down to a handful of operating principles Steve Sanghi reinforced for decades. If you want to judge whether this latest rebound is real, this is the operating system you have to understand.

Customer-Driven Obsolescence: Most chip companies clean up their portfolios by discontinuing older parts—sometimes because the economics get ugly, sometimes to push customers to something newer. Microchip built its reputation by doing the opposite. If customers are still designing a part into products and still ordering it, Microchip’s bias is to keep making it. That’s why some parts in the catalog trace back to the 1990s. For engineers, it’s hard to overstate how valuable that promise is: a forced redesign isn’t just a nuisance, it’s months of work, qualification risk, and surprise costs. Over time, that reliability turns into switching costs—less from contracts, more from trust. And in aerospace and defense, where product lifecycles can stretch for decades, the policy can be the deciding factor.

Fab-Lite Manufacturing: Microchip isn’t fully fabless, but it also doesn’t try to win by building bleeding-edge mega-fabs. It keeps a few specialized internal facilities and uses external foundries for flexibility. The idea is to avoid getting crushed by fixed costs when the cycle turns, while still maintaining enough control to protect supply and margins. Sanghi’s famous line—“we buy other people’s mistakes”—captures the strategy: rather than pouring billions into greenfield capacity, Microchip looks for distressed or underutilized assets it can buy at a discount. The Gresham, Oregon facility acquired from Fujitsu in 2002 became the canonical example.

Acquisition Integration: Microchip has done a long list of deals, and what separates it from many serial acquirers is what happens after the press release. The integration playbook is consistent: go after cost synergies, eliminate duplicate overhead, consolidate where it makes sense, and apply Microchip’s operating discipline. It can be ruthless on back-office and executive excess—as the Microsemi cleanup showed—but it’s careful about what customers actually bought. The products stay supported, and the engineering continuity that matters to the installed base is protected, even as the broader organization gets pulled into Microchip’s model.

Crisis Management: In downturns, Microchip leans on a very specific set of moves: voluntary executive pay reductions, furloughs, and other shared-sacrifice measures before it resorts to broad layoffs. The goal is practical, not sentimental. Semiconductor recoveries tend to reward the companies that can ramp fastest, and it’s hard to ramp when you’ve cut away the people who know how the machines run, how the supply chain works, and how the customers buy. Keeping the institutional knowledge intact is expensive in the moment—but often cheaper than rebuilding it later.

The Aggregate System: This is the internal management framework Sanghi and Microchip’s leadership built to drive continuous improvement across the company. It ties compensation to overall performance, pushes communication down through the organization, and tries to keep every function—engineering, manufacturing, sales, support—moving in the same direction. In an industry famous for churn and cultural whiplash, it’s one reason Microchip developed an unusual reputation for stability and cohesion.

Diversification: Microchip has long avoided betting the company on a single end market, a single customer, or a single wave. That choice caps some upside during booms—Microchip usually isn’t the most exciting story at the peak—but it creates ballast in downturns. When one segment rolls over, others can keep the ship upright. It’s also why Microchip has historically avoided becoming a “killer application” company that lives and dies on one demand surge.

These ideas have been stress-tested across multiple cycles, and they’ve mostly held. The 2024–2025 correction was one of the harshest tests in years, and Microchip still defended its profitability streak and kept its customer promises intact. The open question now isn’t whether the playbook exists—it does. It’s whether it remains enough in a semiconductor industry that’s evolving, and whether Microchip can keep executing it without turning into a company that depends on one person to run it.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case & Industry Analysis

Bull Case:

The optimistic case for Microchip starts with the simplest argument: this is a Steve Sanghi company again. He already pulled Microchip back from the edge once—when it was losing money, running out of cash, and nearly sold for scrap value. Then he spent three decades building a system that could stay profitable through cycle after cycle. If you believe that operating system still works, the 2024–2025 downturn looks less like a permanent break and more like a familiar semiconductor hangover: inventory gets bloated, orders freeze, then the pipeline clears and the machine restarts.

The second bull pillar is breadth. Microchip sells an enormous catalog—tens of thousands of parts across microcontrollers, analog, timing, connectivity, security, and FPGA products. That matters because embedded design is sticky. When an engineer chooses a microcontroller, they don’t just choose a chip. They choose a toolchain, reference designs, software libraries, a support ecosystem, and a supplier relationship that can last the life of the product. Once you’re already in that world, it’s easier—and often safer—to keep pulling adjacent components from the same vendor. Microchip benefits from that “surround the MCU” dynamic, and its development tools add another layer of inertia.

Then there’s the moat that customers actually talk about: customer-driven obsolescence. Most suppliers love to prune older parts. Microchip’s brand promise is that it won’t force you into a redesign just to make its own life easier. In industrial, automotive, and aerospace programs—where qualification is expensive and product lifetimes stretch out for years—that promise can be the difference between “trusted supplier” and “never again.”

Microsemi also gave Microchip something the pure embedded players don’t have: real weight in aerospace and defense, now around the high teens of revenue. Those markets tend to be slower, more qualified, and less price-elastic—and demand has been supported by rising defense spending globally. Within that, radiation-hardened FPGA products are a particularly scarce niche, with high barriers to entry and very few credible alternatives.

Finally, Microchip has an investor-friendly profile in a sector that often doesn’t: a long dividend record, including more than twenty consecutive years of dividend increases and ninety-three consecutive quarters of payments. That doesn’t make the stock cheap or expensive by itself, but it does signal a certain kind of discipline and cash-generation focus.

Bear Case:

The bearish view begins with the same thing the bull case celebrates: Sanghi. He turned seventy in July 2025. After the leadership transition to Ganesh Moorthy and Sanghi’s return, the succession question isn’t theoretical anymore—it’s the central governance risk. Microchip’s culture and execution have been unusually tied to one architect for a long time. If Sanghi can stabilize results but not build the next bench, the company risks repeating the same problem a few years from now.

There’s also real competitive pressure. Microcontrollers and a lot of mainstream analog are not protected markets. Asian competitors continue to improve, and the low end is relentlessly prone to commoditization. Even when Microchip executes well, price pressure never truly goes away.

Microchip’s manufacturing posture is another fault line. The fab-lite approach has historically kept fixed costs under control, but it can leave the company exposed when competitors achieve structural cost advantages through scale. Texas Instruments is the obvious comparison here, with its heavy investment in 300mm wafer capacity. If TI can sustainably produce high-volume analog at lower cost, Microchip may have to defend share with a mix of service, breadth, and longevity promises—advantages that are real, but not always enough in a price fight.

Then there’s the growth narrative of the current era: artificial intelligence. The 2024–2025 downturn made the contrast painfully clear. While some semiconductor peers were buoyed by data center AI spending, Microchip had little direct exposure. If AI continues to be where the industry’s fastest growth and best multiples concentrate, Microchip risks being structurally underrepresented in the market’s most exciting profit pool.

Finally, acquisitions cut both ways. Atmel was a success story. Microsemi was strategically valuable, but it also showed how messy a big integration can get—and it came with meaningful leverage. Deleveraging has progressed, but the balance sheet is still less flexible than it was before the mega-deal era.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Low to moderate. Chips require deep expertise and serious capital. But government-backed efforts—especially in Asia—can change the equation by subsidizing new capacity and new competitors.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Microchip uses external foundries for portions of production and depends on specialized equipment and materials. The 2020–2022 shortage was a reminder that supply constraints can reshape the whole industry overnight.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate. Large customers, especially in automotive and industrial, can negotiate hard. But design lock-in, qualification requirements, and Microchip’s breadth and support reduce how quickly buyers can move.

Threat of Substitutes: Low for embedded applications. Microcontrollers, timing, and analog components are foundational building blocks—there’s no broad substitute for “a small computer plus the circuitry that lets it talk to the real world.”

Competitive Rivalry: High. The competitive set is crowded and world-class: Texas Instruments, Analog Devices, STMicroelectronics, Infineon, NXP, Renesas, and others all fight for overlapping sockets.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: Limited relative to the biggest integrated manufacturers. Microchip’s fab-lite model trades some scale advantage for flexibility.

Network Effects: Moderate. The Arduino ecosystem, long built around Atmel chips, creates real momentum in hobbyist and education channels—less so in industrial procurement, but still meaningful for mindshare.

Counter-Positioning: Strong. Customer-driven obsolescence is hard for many competitors to match because it conflicts with their preference for portfolio simplification and efficiency.

Switching Costs: Strong. Toolchains, software, qualification, and long product lifecycles make switching suppliers expensive and risky.

Branding: Moderate. Microchip isn’t a consumer brand, but among embedded engineers it has a reputation for reliability, documentation, and support.

Cornered Resource: Moderate. PIC and AVR ecosystems have loyal installed bases, and Microchip’s accumulated IP from acquisitions is substantial.

Process Power: Strong. The Aggregate System is a real, institutionalized operating model—one that’s been stress-tested across cycles and integrations, and isn’t easily copied.

Competitive Positioning:

Against Texas Instruments, Microchip is smaller and less manufacturing-scale advantaged, but often stronger in certain embedded niches and in the “we’ll support this forever” promise. TI can win on cost in high-volume analog; Microchip tries to win on breadth, continuity, and customer intimacy.

Against Analog Devices, Microchip overlaps less on the highest-end precision analog and more on embedded breadth. They compete, but they’re not perfect mirrors.

Against European competitors like STMicroelectronics and Infineon, Microchip generally has less automotive concentration but deeper positioning in industrial and aerospace/defense. STMicro, in particular, is heavily automotive-weighted, which creates a different risk and opportunity profile.

Against Renesas and NXP, the overlap is more direct in microcontrollers and automotive-related sockets, with each company strong in different subsegments and customer relationships.

Key Performance Indicators:

If you’re trying to track Microchip’s health without getting whiplash from quarterly revenue swings, two indicators do most of the work:

Non-GAAP Gross Margin: This is the clearest read on whether Microchip is defending its pricing and mix, and whether manufacturing is running efficiently. It’s also a quick check on commoditization risk: revenue can rise for bad reasons, but sustained margin strength is harder to fake. Historically, Microchip has aimed for gross margins in the low-to-mid 60 percent range.

Days of Inventory Outstanding (DIO) in Distribution Channel: After a downturn driven by inventory correction, this is the “is the hangover ending?” metric. It captures how much product is sitting at distributors relative to sales. When channel inventory is elevated, distributors can sell from stock instead of ordering new parts from Microchip, suppressing reported demand. A move back toward more normal levels—often described as roughly four to six weeks of supply—signals the pipeline is clearing and that orders are more likely to reflect real end demand again.

XI. Epilogue: What Would We Do?

Microchip’s story leaves you with a set of investor questions that don’t fit neatly into a model. They’re about leadership, culture, and whether an operating system that worked for three decades can keep working when the architect isn’t the one running it.

Start with the succession problem, because it’s no longer abstract. Steve Sanghi isn’t just “a CEO.” He’s the person who designed the culture, enforced the discipline, and taught the organization how to behave when the cycle turns ugly. He’s the keeper of the playbook that let Microchip grind out profits through crisis after crisis. He has decades-long relationships with customers and distributors. When he shows up, he brings the credibility of someone who has actually lived through the full range of semiconductor disasters and come out the other side.

But nobody does this forever. Sanghi turned seventy in July 2025. He may be healthy and fully engaged, but time is undefeated. And the Moorthy chapter was a reminder that continuity is not guaranteed just because a successor is internal, capable, and steeped in the company’s way of doing things. Moorthy had spent more than two decades at Microchip and still, when the downcycle arrived and the decisions got brutal, the transition didn’t hold.

So what happens when Sanghi can’t, or won’t, do the job anymore?

The board’s real work is to build leadership depth that can preserve Microchip’s discipline without turning the company into a Sanghi-dependent institution. That’s hard. Companies shaped by singular leaders often discover that the most important parts of their advantage aren’t written down. They’re instinct, timing, and judgment—things that don’t transfer cleanly in a handoff memo. You can codify policies. You can teach processes. You can’t easily replicate the feel for the cycle that comes from three decades of making the calls.

Then there’s the strategic tradeoff Microchip has always embraced: profitability over headline growth. That bias built the streak and protected the company in downturns. But the industry is changing. Scale matters more than ever, and some competitors are spending enormous sums on manufacturing and R&D. Meanwhile, AI-centric semiconductor businesses are getting pulled forward by explosive demand. Microchip’s conservatism has historically been a feature, not a bug—but the risk is that “steady and disciplined” becomes “slow and outgunned” if the center of gravity in semiconductors keeps shifting.

Acquisitions are the most obvious lever Microchip can pull. The company has a real track record here, and leverage has come down since the Microsemi peak. If the next downturn creates distressed assets—smaller analog or microcontroller players squeezed by the cycle, specialty component companies in adjacent categories, or underutilized manufacturing capacity available at the right price—Microchip has shown it’s willing to act. The question isn’t whether it can do deals. It’s whether the next deals will strengthen the core without stretching the organization, especially during a leadership transition era.

And then there’s the elephant in the room: artificial intelligence. Microchip has positioned itself as an edge-AI enabler—intelligence pushed out into devices, not concentrated in cloud data centers—but it hasn’t yet become a meaningful AI revenue story. If edge AI actually spreads through industrial equipment, automotive systems, and IoT deployments, Microchip is well positioned to participate. If the industry’s fastest growth remains concentrated in data centers and cloud infrastructure, Microchip risks watching the most exciting profit pool accrue elsewhere.

So if we had to sum it up: Microchip is still a remarkably durable company, with a real operating system and a real culture. But its near-term fate remains tied to Steve Sanghi in a way that’s both reassuring and unsettling. As long as he’s at the helm, you can reasonably expect the familiar playbook: discipline, integration, customer trust, and an almost stubborn commitment to staying profitable.

The open question—the one that will define the next decade—is whether Microchip can turn that playbook into something that outlasts the person who wrote it.

XII. Recent News

Microchip’s fiscal third quarter 2026 results, released in December 2025, landed above the company’s own guidance. Net sales were $1.186 billion, up about fifteen percent year over year. More important than the headline number was the direction: this was the third straight quarter of sequential improvement. Management raised its outlook for the fourth quarter too—a clear signal that, in their view, the inventory hangover was finally easing.

Aerospace and defense kept doing what Microchip bought Microsemi to do: act like ballast when the rest of the ship gets tossed around. The segment sat at roughly eighteen percent of revenue, up from about eleven percent before the Microsemi deal. And this wasn’t just a math trick caused by weaker industrial and consumer demand; Microchip said aerospace and defense revenue continued to grow in absolute terms, supported by elevated global defense spending. NATO countries increasing commitments, ongoing conflicts that forced replenishment, and broad modernization programs all kept demand steady.

Industrial—ground zero for the correction—began to look less dire. Distributors said their inventories were finally moving back toward normal after nearly two years of excess. Some direct customers who’d been living off stockpiles started ordering again. It wasn’t a snapback to boom times, but it matched the “bottoming” process Sanghi had been describing.

The CHIPS Act decision stayed a point of debate. The grant pause Sanghi announced in December 2024 remained in place into early 2026. He repeated the same reasoning: Microchip wasn’t going to take government subsidies to expand capacity in an industry that still looked oversupplied. Some analysts applauded the discipline. Others worried Microchip could end up disadvantaged versus peers using CHIPS funding to build more domestic manufacturing.

On the manufacturing side, the Fab 2 closure in Tempe moved forward, with shutdown completion expected by September 2025. Employees were offered relocation to other Microchip sites or severance. It was a symbolic moment—Tempe had been part of Microchip’s footprint for decades—but in a lower-demand world, the capacity had become redundant.

Outside the company, the argument was still about timing. Some analysts believed the correction was mostly over by early 2026. Others warned that industrial demand could stay weak longer if global manufacturing remained sluggish. Microchip’s own tone was cautiously optimistic, with the familiar caveat that visibility was still limited—because in semiconductors, the signal always arrives late, distorted by distributors, contract manufacturers, and cautious customers.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings: - Microchip Technology SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q reports) - Microchip Investor Relations: ir.microchip.com

Leadership Resources: - "Driving Excellence: How The Aggregate System Turned Microchip Technology from a Failing Company to a Market Leader" by Steve Sanghi and Michael Jones (2006) - "Up and to the Right: How Microchip Went from Nearly Bankrupt to Industry Juggernaut" by Steve Sanghi - "Ask Steve: A Lifetime of Leadership Advice" by Steve Sanghi

Historical and Industry Sources: - "Chip Hall of Fame: Microchip Technology PIC 16C84 Microcontroller" - IEEE Spectrum - "KeeLoq Technology History" - industry publications - "General Instrument spinoff documentation" - historical corporate filings

Acquisition Documentation: - Atmel acquisition proxy statement (2016) - Microsemi acquisition tender offer materials (2018) - Micrel acquisition press releases and filings (2015)

Industry Analysis: - Semiconductor Industry Association reports - IC Insights market research - Gartner semiconductor market analysis - SIA semiconductor market analysis and forecasts - McKinsey: The semiconductor industry in 2025 and beyond

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music