M&T Bank: Building a Regional Banking Empire Through Prudence and Partnership

I. Introduction & Cold Open

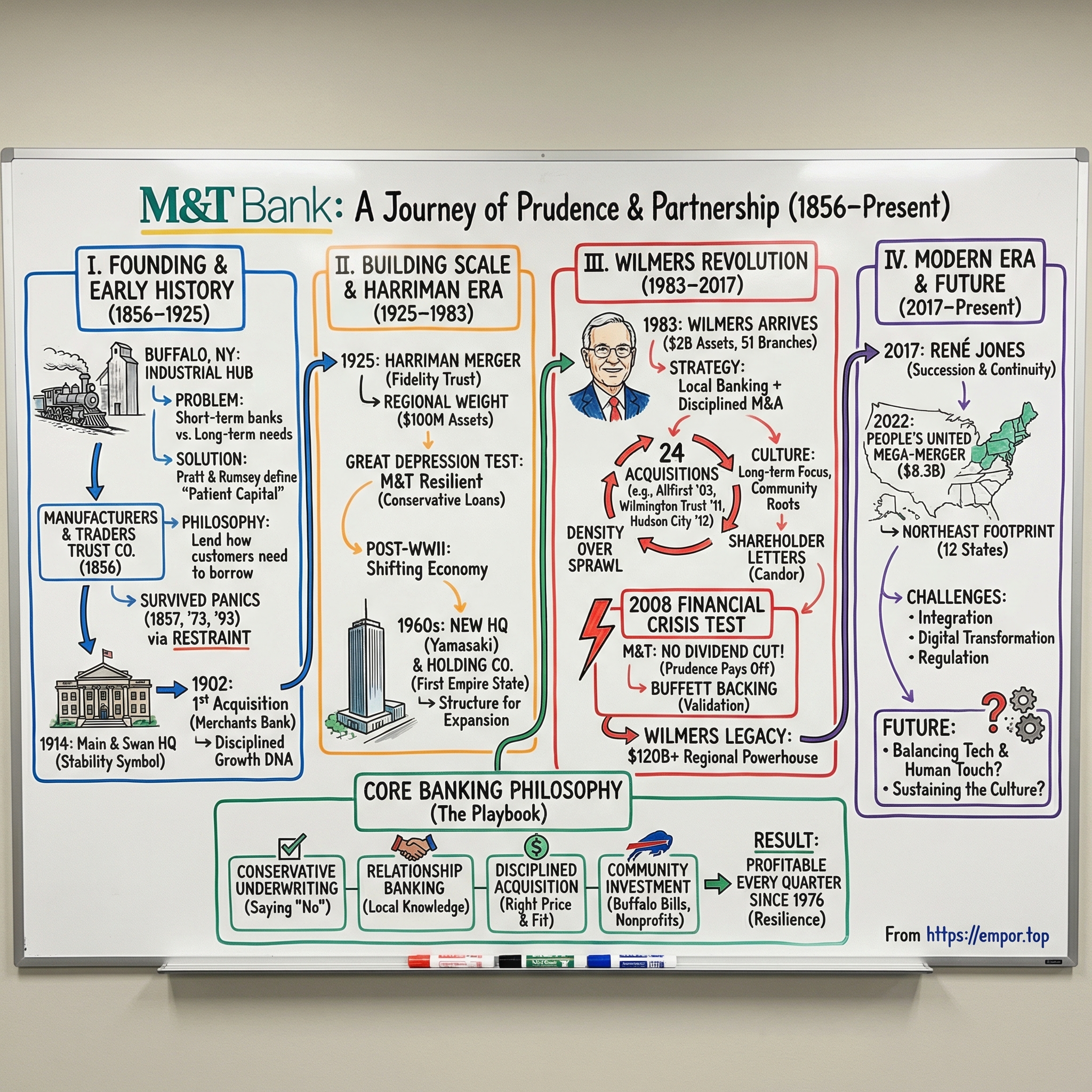

Picture Buffalo, New York, in the winter of 1856. The Erie Canal had turned a lakefront outpost into one of America’s busiest inland ports. Grain elevators lined the waterfront. Iron foundries pushed smoke into the cold sky. Factories making everything from soap to steam engines packed the industrial districts.

And yet, for all that momentum, Buffalo’s entrepreneurs kept running into the same wall: the local banks wouldn’t lend long.

In that era, banks were built for short-term credit—ninety-day notes, seasonal financing, the fast churn of commercial paper. That worked fine if you were moving inventory or bridging a shipment. But if you were a manufacturer trying to buy a steam-powered lathe or expand a foundry, your cash was going to be tied up for years, not months. Buffalo’s industrial economy needed patient capital. Its financial system mostly offered the opposite.

That gap was the opportunity.

Two local businessmen, Pascal Paoli Pratt and Bronson Case Rumsey, saw it clearly. They pooled $200,000 and founded what would become M&T Bank—originally the Manufacturers and Traders Trust Company—built specifically to make the longer-term loans other banks wouldn’t. The insight was almost embarrassingly straightforward: lend the way your customers actually need to borrow, not the way the industry happens to prefer.

Nearly 170 years later, that mindset still shows up in the numbers. M&T operates more than 950 branches across twelve states and Washington, D.C., from Maine down to Virginia. It employs over 22,000 people. It has been profitable in every quarter since 1976—nearly five decades of consistency through oil shocks, recessions, bubbles, crashes, and pandemics. And in 2008, when the financial system nearly broke and big banks rushed to cut dividends, M&T was one of only two banks in the S&P 500 that didn’t.

So how did a regional bank from Buffalo become one of America’s most resilient and admired banking franchises?

The answer is a philosophy—conservative underwriting, deep community roots, and disciplined acquisition—developed over generations and refined into a repeatable playbook. And later, it was scaled dramatically under the leadership of Robert Wilmers, who took a $2 billion local bank and turned it into a $120 billion regional powerhouse.

This is a story about patience in an industry that often rewards speed. About saying “no” when everyone else is saying “yes.” And about what happens when you build a financial institution designed, from day one, to last.

II. Founding & Early History: Manufacturing Trust (1856-1925)

The Buffalo that Pratt and Rumsey looked out on in 1856 wasn’t just growing—it was humming. The Erie Canal, finished a few decades earlier, had turned the city into a critical transfer point: goods flowing out of the American interior moved from canal boats to lake steamers, and back again. By the 1850s, Buffalo handled more grain than any city on earth. Flour mills chewed through wheat shipped in from the prairies. Ironworks pushed out the hardware of westward expansion. Tanneries processed hides arriving from Chicago.

All of that industry had one thing in common: it was expensive. A grain elevator didn’t get built on a handshake. A steam engine wasn’t a quick flip—it was years of capital tied up before you saw the payoff.

But the banking system of the era was still stuck in the rhythms of merchant trade. It was great at short-term lending: financing inventory, discounting bills that came due in weeks, making loans that could be repaid quickly if something went sideways. That model worked for commerce. It didn’t work for manufacturing. Buffalo’s industrialists didn’t need money for ninety days. They needed money for years.

Pratt understood that firsthand. He came from manufacturing, and he knew exactly what it felt like to sink cash into machinery and wait—sometimes a long time—for returns. Rumsey brought relationships and credibility with Buffalo’s commercial leadership. Together, they built a bank to do what others didn’t want to do: make longer-term loans, backed by real property and industrial equipment, aligned with the real timeline of industrial growth. Even the name—Manufacturers and Traders Trust Company—was a mission statement.

Those early decades set the template. The bank grew steadily, relationship by relationship, business by business. It learned the local industries in depth. And it developed a habit that would become one of its defining traits: surviving downturns not through cleverness, but through restraint. It made it through the Panic of 1857, the disruptions of the Civil War, and the crises of 1873 and 1893—emerging intact each time, in large part because it hadn’t chased the excesses of the prior boom.

Then, in 1902, it made its first acquisition: Merchants Bank of Buffalo. The deal wasn’t noteworthy for its size. It was noteworthy for what it signaled. Instead of trying to grow by stretching underwriting or racing into new markets, the bank chose to scale by combining with another institution. The instinct to grow through disciplined M&A—the DNA of the modern M&T story—was already there.

By the early twentieth century, the bank was big enough to start thinking in symbols, not just spreadsheets. In 1914, it moved into a massive white marble building at Main and Swan Streets—an intentional statement of stability in an industry where confidence is the product. That same year, Robert Livingston Fryer took over as president and steered the institution into a new era.

World War I pulled Buffalo even deeper into the center of American industry. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, local manufacturers shifted to producing war materiel—ammunition, aircraft components, and military equipment of all kinds. Manufacturers and Traders Trust financed that surge. And Harry T. Ramsdell, one of the bank’s senior officers, became district chairman for the Liberty Loan program, leading efforts to sell war bonds and fund the national cause.

The war years accelerated Buffalo’s economy, and the bank grew alongside it. By the early 1920s, Manufacturers and Traders Trust had become one of the city’s leading financial institutions—still conservative, still local at heart, but increasingly influential in a Buffalo that remained a serious American industrial powerhouse.

And that meant the next phase was inevitable: scale. The stage was set for a new leader, and a new chapter, that would reshape the institution for the modern age.

III. The Harriman Era & Building Scale (1925-1969)

Lewis G. Harriman was just thirty-six in 1925 when he pulled off the deal that turned Manufacturers and Traders Trust from a dominant Buffalo bank into something with real regional weight. He merged it with Fidelity Trust Company, creating a combined institution with $100 million in assets—huge for Buffalo, and suddenly big enough to matter well beyond city limits.

Harriman didn’t just bring youth and drive. He brought a network that connected Buffalo to the national establishment. His investor group included A. H. Schoellkopf, from the family behind Niagara Mohawk Power and the development of Niagara Falls’ hydroelectric potential. It also included James V. Forrestal, a Wall Street investment banker who would later become the first U.S. Secretary of Defense. These weren’t purely local backers looking for a respectable hometown franchise. They were people who thought in decades and in scale—and they saw Buffalo’s premier bank as worth building.

On paper, the timing looks brutal. The merger came only four years before the Great Crash. But the Depression ended up showcasing the bank’s most valuable trait: restraint. While banks across America collapsed—nearly 10,000 failures between 1929 and 1933—M&T made it through. More than that, it came out the other side stronger relative to the field, in large part because it hadn’t joined the speculative lending that took so many others down.

That wasn’t luck. It was baked in from the beginning. Manufacturers and Traders had been created to make prudent, long-term loans to businesses its people actually understood. That meant knowing borrowers, understanding industries, and being willing to walk away from deals that didn’t fit conservative standards. When the economy broke, that discipline mattered. The bank’s customers tended to be sturdier than average, and the bank held steady alongside them.

After World War II, growth continued, but the world around Buffalo was changing. The city remained an industrial force—steel, auto parts, food processing—but its relative importance slowly slipped as economic gravity moved to the Sun Belt and the suburbs. M&T could grow with its home market, but state banking rules still kept it largely boxed in.

By 1961, the bank was confident enough to make a very public bet on its future. It bought an entire block on Main Street for $12 million to build a new headquarters tower. And it didn’t hire a local architect to play it safe. M&T brought in Minoru Yamasaki, celebrated for his modern designs and later known as the architect of the World Trade Center.

The resulting M&T Bank Building—completed in the mid-1960s—was a glass-and-steel statement in the Buffalo skyline: modern, ambitious, and intentionally on par with what you’d expect from much bigger-city institutions. It still stands today, the downtown landmark where M&T runs an organization far larger than anyone in 1925 could have imagined.

Then, in 1969, came the structural move that set up the next era. M&T reorganized under a bank holding company, First Empire State Corporation. It sounded like paperwork, but it was strategy. The holding company structure created room to acquire banks across New York State—and, eventually, beyond it—working around the geographic restrictions that had kept growth tethered to Buffalo.

The chassis was built. Now it needed a driver.

IV. The Wilmers Revolution: From Local to Regional Power (1983-2017)

Robert G. Wilmers showed up at First Empire State Corporation in 1983 with the kind of résumé that usually ends at the top of something huge, glossy, and headquartered in Manhattan. Harvard. Morgan Stanley. Senior roles at New York City institutions. The sort of career arc that comes with an implied address.

Instead, he took over a $2 billion bank with 51 branches, all in one state, and about 2,000 employees.

To a lot of people, it didn’t compute. Buffalo in the early ’80s wasn’t a city on the upswing. Steel was collapsing. Jobs were leaving. People were leaving. Downtown buildings that had once signaled permanence now signaled vacancy. If you were a well-connected banker with options, this was not the obvious place to plant your flag.

Wilmers saw it differently. Under the chipped paint, he saw a franchise with real value: conservative habits, deep customer relationships, and a culture built to survive bad cycles. He saw the holding company structure—set up years earlier—not as legal plumbing, but as an engine for expansion. And he saw the direction the industry was heading. Banking consolidation was coming. The winners wouldn’t be the flashiest. They’d be the ones who could buy well, underwrite carefully, integrate cleanly, and keep their nerve when the cycle turned.

That was M&T’s lane. Wilmers just decided to run it at full speed.

Over the next three decades, he turned what was essentially a Buffalo institution into a serious regional power up and down the East Coast. By the time he died in 2017, M&T had grown from $2 billion in assets to more than $120 billion. Its footprint went from 51 branches to 783 across eight states plus Washington, D.C. Headcount climbed from about 2,000 employees to nearly 17,000. The engine behind that expansion was a steady drumbeat of deals—twenty-four acquisitions—executed with the same discipline, over and over.

The early transactions set the tone. From 1990 to 1992, M&T absorbed Monroe Savings, acquired deposits from the failed Empire of America and Goldome Bank, and bought Central Trust of Rochester and Endicott Trust. None of these were splashy trophies. They were the kind of opportunities that appear when other institutions mismanage risk, lose focus, or simply don’t have the scale to keep up. M&T would step in, buy selectively, and then do the hard part: integrate, cut duplication, and keep the customer relationships that were actually worth owning.

Underneath the M&A was a philosophy that even then sounded a little out of time, and today sounds almost radical. Wilmers believed banking was a local business. That lending decisions should be made by people who understood borrowers, not just their spreadsheets. That profits were a byproduct of doing right by customers for a long time, not squeezing them for fees in the short term.

He didn’t just write that down. He built it into how M&T operated. Incentives emphasized the long-term performance of loan portfolios, not just the volume of new loans booked. Branch leaders were expected to know their communities, not simply hit sales targets. The bank’s support for local institutions and nonprofits was presented as part of the job, not a marketing program.

In 1998, the holding company renamed itself from First Empire State Corporation to M&T Bank Corporation. It was a recognition that the institution had grown beyond its old corporate shell—and a nod to the heritage embedded in the original name, Manufacturers and Traders.

Then, in 2005, there was a brief plot twist. Wilmers announced his retirement and handed the CEO job to his chosen successor, Robert Sadler. About eighteen months later, Wilmers was back. Sadler stepped down, and Wilmers resumed the role. The specifics were never fully laid out in public, but the takeaway landed anyway: this wasn’t just a bank he ran. It was a bank he shaped, personally.

The industry noticed. In 2011, American Banker named him Banker of the Year, citing his refusal to chase the fee-heavy, product-pushing playbook that had become fashionable—and his proof that a relationship-driven bank could still outperform.

Stephen Steinour, the CEO of Huntington Bancshares, put it even more plainly: “He may be the most successful banker in half a century.” It’s a big statement, but it captured what made Wilmers unusual. M&T didn’t win by taking the most risk or telling the best story. It won by compounding steadily, buying thoughtfully, and maintaining a culture that could outlast the cycle.

Wilmers also became known for his annual shareholder letters. They weren’t the usual corporate gloss. They were long, candid, and specific—part strategy memo, part critique of the industry’s bad habits. He wrote about what he worried about, what he refused to do, and why M&T’s version of banking was designed to endure.

When he died in December 2017 at age eighty-three, it marked the end of an era. Thirty-four years is an eternity in modern corporate leadership. He had taken a small regional bank and built a franchise with real scale and a distinct identity.

Now came the question every founder-like leader eventually leaves behind: could the institution keep winning without him?

V. Major Strategic Acquisitions & Geographic Expansion (2000-2015)

The 2003 acquisition of Allfirst Bank was M&T’s biggest leap yet—and the moment the bank truly planted a flag in the Mid-Atlantic. Allfirst, the American subsidiary of Allied Irish Banks, had real scale in the Baltimore–Washington corridor, with roots stretching back to the nineteenth century. M&T paid in a mix of stock and cash—26.7 million shares plus $886 million—and in return got what it wanted most: a serious foothold in one of the country’s wealthiest, fastest-moving regions.

But the deal didn’t come to market because AIB woke up one morning and wanted to reshape its portfolio. It came to market because Allfirst was in the middle of a scandal. The bank had lost $691 million to fraudulent trading by a currency trader, John Rusnak, who had hidden losses for years. When it finally surfaced, AIB had to act—and selling its U.S. operation became the cleanest exit.

This was exactly the kind of moment Wilmers liked. The franchise wasn’t rotten. The markets were good. The deposits were valuable. The relationships were real. The failure, as Wilmers saw it, wasn’t the customer base—it was controls and risk culture. And those were the areas where M&T believed it could reliably do better than almost anyone.

AIB didn’t walk away entirely. It kept a 22% ownership stake in M&T after the transaction, a large position that lasted until 2010. Then Ireland’s own banking crisis hit, and Irish regulators pushed AIB to sell. In a twist that underscored how well the deal worked out for both sides, that stake—received in distressed circumstances—became a source of much-needed value as Ireland’s system tried to stabilize.

Allfirst also became a template for how M&T integrated acquisitions. The bank didn’t treat every deal like a conquest. It tried to keep what worked—especially local leadership and community ties—while steadily installing M&T’s core operating principles. Relationship banking wasn’t something you could mandate by memo. M&T pushed it through training, incentives, and expectations that compounded over time.

In 2009, M&T bought Provident Bank of Maryland, extending that Mid-Atlantic buildout. Then came a very different kind of acquisition, and a much harder one: Wilmington Trust.

Wilmington Trust was a storied Delaware institution, founded by the du Pont family in 1903. For decades it was known as one of the country’s premier trust companies—managing the affairs of wealthy families and serving as corporate trustee on complex transactions. But the financial crisis exposed a darker side: aggressive commercial real estate lending that hammered capital and left the institution fighting for survival by 2010.

M&T stepped in in 2011, acquiring Wilmington Trust for $351 million in stock. The deal was both rescue and strategy. It kept Wilmington Trust from potential failure while giving M&T a meaningful trust and wealth management platform. It also came with a Delaware banking charter—useful for corporate and legal purposes—and further deepened M&T’s presence along the Mid-Atlantic corridor.

The integration wasn’t smooth. These were different worlds. M&T was a commercial bank built around middle-market lending. Wilmington Trust carried the habits and expectations of a legacy trust company catering to wealthy clients. And the problem-loan cleanup took years. But this was where M&T’s temperament showed: it didn’t try to force quick wins. It worked the portfolio down patiently and built toward something durable.

In 2012, M&T announced an even bigger swing: the acquisition of Hudson City Bancorp for $3.7 billion. Hudson City had 135 branches and $25 billion in deposits, concentrated in New York and New Jersey. Strategically, it offered what M&T wanted most—more presence in and around the New York metro area, one of the largest banking markets on earth.

What followed, though, was anything but routine. Regulatory approval dragged on for three years. Federal regulators flagged deficiencies in M&T’s anti-money-laundering compliance systems and refused to sign off until the bank fixed them. The delay was expensive in every sense: direct costs, management bandwidth, and the simple drag of living in limbo.

M&T could have walked away. It didn’t. Instead, it invested heavily in compliance infrastructure and stayed with the deal until it cleared. The Hudson City saga became a reminder of two realities of modern banking: the regulatory load on regional banks can be crushing—and M&T, when it believes the strategy is right, is willing to do the work and wait.

Through all of these acquisitions, Wilmers kept returning to the same organizing principle: density over sprawl. M&T didn’t want a scattering of branches across the map. It wanted concentrated strength in contiguous markets—enough presence to win commercial relationships, enough local visibility to feel like a community bank, and enough operational overlap to run efficiently. In other words: not just growth, but shape.

VI. The Financial Crisis Test: Strength Through Adversity (2007-2010)

The 2008 financial crisis was the moment the entire industry got graded on the curve—and M&T was one of the very few banks that didn’t need one.

As the system seized up, household-name institutions either failed outright or survived only with extraordinary support. Balance sheets that had looked bulletproof turned out to be brittle. And across the banking landscape, dividends—the ultimate signal of confidence—were cut fast to conserve capital.

M&T didn’t.

Among banks in the S&P 500, only two kept paying their dividends straight through the crisis: Northern Trust, a trust-focused institution with limited exposure to consumer credit, and M&T—a full-service commercial bank that had simply declined to load up on the kinds of risk that were now detonating across the industry.

It wasn’t a miracle. It was the payoff from years of deliberate choices. M&T largely stayed out of subprime mortgage lending. It kept underwriting standards tight while competitors loosened theirs to chase volume. And it carried more capital than it technically needed, giving itself room to absorb losses without panicking.

Just as important: Wilmers treated the crisis as an opportunity to play offense, not just defense. While other banks pulled back, M&T went shopping—carefully. It selectively acquired troubled institutions and, even more importantly, their deposits. The 2009 acquisition of Provident Bank of Maryland fit that pattern: a solid franchise changing hands because the owners were distressed, not because the underlying customer relationships had stopped being valuable.

The crisis also handed Wilmers a bigger microphone, and he used it. He criticized the incentives that pushed banks toward short-term risk-taking, the complexity that made exposures easy to hide, and a regulatory framework that hadn’t kept up with what Wall Street had become. In his shareholder letters, he argued that the biggest banks had grown too large and too complicated to manage well—or regulate effectively—and that compensation systems were rewarding exactly the behaviors that had brought the system to the brink.

Those arguments weren’t designed to win friends in investment banking. But they landed with investors and policymakers looking for someone to explain, plainly, how so much “sophistication” had produced such fragile institutions.

And the crisis strengthened a relationship that mattered in markets: Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway. Buffett had long admired M&T’s culture and Wilmers’ approach to banking. Berkshire owned a substantial stake, and Buffett’s backing served as a kind of external validation: this was what prudence looked like when the cycle turned.

For shareholders, the takeaway couldn’t have been clearer. Owning M&T through the crisis meant coming out the other side with far less damage—and with dividend income uninterrupted—while owners of many competitors absorbed brutal losses. In banking, it turns out, surviving the bad years isn’t just part of the job. It’s the whole job. And M&T had built itself for exactly that.

VII. Post-Wilmers Era & People's United Mega-Merger (2017-Present)

Robert Wilmers’ death in December 2017 closed a defining chapter—but it didn’t leave a vacuum. The succession plan he’d put in place held. Robert T. Brady stepped in as Non-Executive Chairman, keeping steady leadership at the board level. Day to day, operations were managed by three vice chairmen—Richard Gold, René Jones, and Kevin Pearson—in a deliberately collaborative setup designed to preserve institutional memory while the next generation proved itself.

Over time, one name rose to the top. René Jones became CEO, and with him came the most important confirmation M&T could offer the market: the culture wasn’t leaving with Wilmers. Jones had spent his entire career at M&T, rising inside the system and absorbing its operating habits. He wasn’t trying to imitate Wilmers. He didn’t have to. He was, in a very real sense, a product of what Wilmers built—and that DNA turned out to be transferable.

Then came the biggest acquisition in M&T’s history. In 2022, M&T closed its $8.3 billion purchase of People’s United Financial, a New England-based bank founded in 1842 with a footprint across Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and New York. Overnight, M&T’s map filled in. The combined company spanned twelve states, employed more than 22,000 people, and ran over 1,000 branches and about 2,200 ATMs.

Strategically, the logic was classic M&T. People’s United brought sticky deposits in markets that skew stable and affluent—exactly the kind of territory where relationship banking can still compound quietly. It also delivered more scale at a moment when scale increasingly shaped everything from technology spending to regulatory overhead.

But big deals don’t just expand a footprint; they test an operating system. Integration was costly and messy. M&T recorded $580 million in merger-related expenses in 2022, a reflection of how hard it is to combine two large banks with different systems, processes, and habits. The most visible challenge was technology: migrating millions of customer accounts onto a single platform without breaking trust is the kind of work customers only notice if you get it wrong.

All of this was happening as the banking environment got more unforgiving. Rising interest rates helped margins in theory, but they also created mark-to-market losses on bond portfolios across the industry, pressuring capital ratios and investor confidence. The 2023 failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank—driven by deposit flight and unrealized losses—were a fresh reminder that banking is still, at its core, a confidence business. When confidence cracks, fundamentals can become irrelevant in a hurry.

M&T made it through that period without the same public drama that engulfed some regional peers. Its underwriting had stayed conservative, so it wasn’t staring down the same kinds of deteriorating loans. Its deposits were spread across millions of retail and commercial customers, not clustered in a small number of large accounts that could sprint for the exits. And the risk culture that had been drilled into the organization for decades continued to shape decisions after Wilmers, not just before him.

Still, the world M&T is navigating now is different from the one Wilmers inherited in 1983. Digital transformation isn’t optional when customers expect their bank to live on a phone, not just on a corner. Fintechs can offer clean interfaces and low-cost delivery, and they’re happy to cherry-pick the most profitable slices of banking. Meanwhile, the largest banks can spend on technology at a scale no regional bank can realistically match.

And yet M&T has assets that are hard to download. Long-standing commercial relationships create real switching costs, especially for small and mid-sized businesses with complex needs. A dense branch network still matters in the communities M&T serves, particularly when the transaction isn’t just a tap-and-go payment but a relationship decision. And, in an industry where fear can spread faster than facts, M&T’s conservative posture remains a competitive advantage.

The big question going forward is simple: does the model Wilmers built—relationship banking, conservative underwriting, disciplined acquisition—still work under the weight of modern technology and regulation? The early post-Wilmers evidence suggests it does. But in banking, the test is never final. It just keeps coming around.

VIII. Culture & Community Banking Philosophy

Visit Buffalo on a Sunday in the fall and you’ll see something that tells you a lot about M&T without saying a word: its name on the home of the Buffalo Bills. Stadium naming rights are everywhere now, of course. What’s different here is how long it’s been true. M&T’s partnership with the Bills has run since 1985—one of the longest continuous brand relationships in pro football.

That longevity isn’t just a marketing trivia fact. It’s a window into how M&T sees itself. This is a bank that stayed rooted in Buffalo while plenty of companies moved headquarters, moved capital, and moved attention elsewhere. Its leadership has historically lived in the places it serves, not at a remove in distant financial capitals. And it treats civic presence as part of the job, not a side project.

You can see that in the giving. Over the past decade, M&T and its foundation have contributed more than $279 million to more than 7,600 nonprofits across its footprint. And it’s not just checks sent from a corporate office. Employees show up: serving on boards, volunteering, and doing the unglamorous work that makes community organizations function.

That community posture is tightly linked to the thing M&T is best known for: conservative lending. If you expect to be in a city for generations, you can’t make loans that look great this year and implode two years later. If your lenders bump into borrowers at the grocery store—or sit next to them at local events—you get a different kind of information than a centralized model can capture. And when your reputation is local, shortcuts that juice short-term profits come with a real, lasting cost.

In practice, that philosophy often means saying “no” when “yes” would be easier. M&T has repeatedly refused to chase growth by loosening underwriting. It has avoided categories where it doesn’t believe it has an edge, even when competitors are earning attractive returns there. And it has kept concentration limits and collateral discipline that others have relaxed in the name of volume.

The culture shows up internally, too. M&T promotes from within at a level that stands out in modern finance. Many senior leaders have spent decades at the bank. That kind of tenure builds institutional memory and consistency—useful in any business, but especially valuable in one where judgment, cycle awareness, and risk discipline are everything.

Even the shareholder letters reflect the same personality. The tradition Wilmers made famous has continued: substantive, specific discussions of strategy and industry conditions, written as if shareholders are true partners who deserve the real story, not a carefully smoothed-over version.

For investors, that culture cuts both ways. It’s an asset because it has produced unusually durable results and advantages that are hard to copy. But it’s also fragile, because cultures can thin out as organizations get larger and as defining leaders exit. In the end, the post-Wilmers era will be judged less by any single quarter’s performance than by something slower and harder to measure: whether the culture he embedded can survive growth—and still feel like the same bank.

IX. Playbook: M&T's Banking Strategy

Twenty-four acquisitions over thirty-four years sounds like a growth story. For M&T, it was really an operating system: a repeatable way to get bigger without getting reckless, and to expand without losing the culture that made the bank work in the first place.

It started with selection. M&T was never an indiscriminate buyer. It went after banks with strong deposit franchises in markets worth owning—because in banking, deposits aren’t just “funding,” they’re the cheapest, stickiest raw material you can have. And it often looked for situations where something had gone wrong in management, controls, or focus, but the underlying customer relationships were still good. Just as important, M&T cared about price. It was more likely to pursue a troubled or subscale target than to get into a bidding war for a pristine franchise.

Allfirst is the cleanest example: a real Mid-Atlantic franchise made available by a trading scandal, priced accordingly, with problems that M&T believed its risk culture could fix. Wilmington Trust followed the same logic—an iconic name weakened by aggressive lending, available because the cleanup would be hard and public.

Then came the part that separates serial acquirers from serial disappointment: integration. M&T built a playbook it could run again and again. Core systems were standardized. Back-office operations were consolidated. Risk frameworks and credit discipline were pushed into the acquired loan book. But it handled the front end more carefully, because that’s where value lives. Local leadership was kept when it made sense. Brands and branch identities weren’t ripped off overnight. Transitions were staged so customers didn’t feel like they’d been “bought”—they felt like they’d been taken care of.

Underneath all of it was a geographic rule that sounds simple and is surprisingly rare in practice: density over sprawl. M&T didn’t want a national patchwork. It wanted strength you could see on a map—contiguous markets where branch presence, local knowledge, and commercial relationships reinforce each other, and where operating efficiency improves because the footprint fits together.

And tying the whole system together was risk management. M&T’s streak of profitability in every quarter since 1976 didn’t happen because it predicted every downturn. It happened because the bank built a culture that prioritized long-term loan performance over short-term volume, monitored credit early and often, and empowered risk managers to say “no” even when “yes” would have made this quarter look better.

Capital allocation followed the same temperament. Under Wilmers, M&T carried more capital than the minimum—enough cushion to absorb shocks and enough flexibility to act when others couldn’t. Dividends were kept sustainable: meaningful to shareholders, but not so aggressive that they starved the bank of growth capital. Buybacks were treated as opportunistic, not automatic—pressed when shares looked cheap, eased off when they didn’t.

The lessons are easy to state and hard to live: be patient, pay the right price, integrate relentlessly, don’t chase hot business, and protect the culture that enforces those rules. Plenty of banks understand that list. Far fewer can execute it for decades. M&T did—and that’s why it kept compounding while so many others were busy reinventing themselves after every cycle.

X. Analysis: Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

M&T’s case starts with the simplest, hardest-to-fake evidence: it has made money every quarter since 1976. That kind of streak doesn’t happen because a bank gets lucky for fifty years. It happens when underwriting stays disciplined, risk managers are empowered to be unpopular, and the culture treats “don’t blow up” as the first rule of the job.

After the People’s United deal, M&T also has something it didn’t always have: real scale across a contiguous stretch of some of the most attractive banking markets in the country. From Maine down to Virginia, its footprint now overlaps with deep, diversified regional economies and dense corridors of wealth and commerce—places like greater Boston, the New York metro area, and the Baltimore–D.C. region. These are markets where a relationship-driven bank can still win, because the most valuable customers aren’t shopping for the lowest teaser rate; they’re looking for reliability, judgment, and a lender who can stay with them through a cycle.

The deposit base is another quiet advantage. M&T’s funding is spread across millions of retail and commercial accounts rather than a small number of large, fast-moving institutional relationships. That granularity matters. When parts of the industry were rocked in 2023 by sudden deposit runs, the banks that got hurt tended to have concentrated, correlated depositors. M&T’s customer base is less prone to moving in a single herd, which buys time and stability when confidence wobbles.

And while Robert Wilmers is gone, the acquisition machine he built didn’t disappear with him. People’s United was the biggest integration in M&T’s history. It was expensive, and it demanded a lot of the organization, but it also reinforced a core point: M&T still knows how to absorb another bank and come out the other side as one institution. The accumulated muscle memory of doing this two dozen times is a real asset.

The Bear Case

M&T can be well run and still be stuck in a tough neighborhood. Regional banking is facing structural pressure that discipline alone can’t fully neutralize.

Start with technology. The biggest banks can spend at a scale that changes the economics of competition. When a megabank can invest more in tech in a single year than a regional bank is worth in the public markets, it’s not just a budget gap—it’s a different game. The danger isn’t that M&T suddenly becomes irrelevant. The danger is that the “good enough” digital experience that worked for years stops being good enough, and customer expectations keep ratcheting upward.

Interest rates are another two-edged sword. Higher rates can lift net interest margins at first, but they also raise deposit costs as customers demand better yields, and they can create unrealized losses in securities portfolios. In a higher-rate world, balance sheet management gets less forgiving. You have to get more calls right, and you have less time to fix the ones you don’t.

Then there’s fintech. M&T’s commercial relationships are relatively defensible—switching banks is painful for operating businesses, and relationship banking still has real value when credit is the product. But retail is a different arena. Digital-first competitors can deliver slicker experiences, and they’re often willing to use lower fees to buy growth. Younger customers who rarely, if ever, visit a branch may never form the kind of loyalty that used to anchor regional banks for decades.

Finally, regulation. The largest banks can amortize compliance costs across enormous revenue bases, and the smallest banks often get some relief. Regional banks sit in the uncomfortable middle: heavy expectations, expensive oversight, and fewer ways to spread the cost.

Porter's Five Forces Assessment

Through Michael Porter’s lens, M&T’s position is strong in some ways and pressured in others.

Supplier power—meaning depositors—has risen as rate competition intensified, though M&T’s spread-out deposit base provides some insulation. Buyer power—borrowers—depends on the customer. Large corporate borrowers have options and pricing leverage; small and mid-sized businesses often care more about responsiveness and judgment, where M&T tends to compete well. The threat of substitutes is meaningfully higher than it used to be, as fintech and non-bank lenders slice off profitable products. The threat of new entry is still moderated by regulation and how hard it is to build a deposit franchise. Competitive rivalry remains intense, with megabanks, regionals, and fintechs all converging on many of the same customers.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

Using Hamilton Helmer’s framework, M&T’s advantages are real, but they’re not the kind that make a business unassailable.

M&T clearly has Process Power in bank integration—the ability to combine institutions reliably, repeatedly, and without losing the plot. It has Switching Costs in commercial relationships where moving banks means operational disruption, paperwork, and real business risk. It also has a Cornered Resource in experienced relationship bankers whose market knowledge and local credibility can’t be spun up overnight.

It has some counter-positioning, too: M&T has historically leaned into relationship banking while competitors chased scale, complexity, and short-term yield. The risk is that this advantage erodes if technology becomes the primary battleground for winning and keeping customers.

And the gaps matter. M&T doesn’t have Network Effects like payments networks. Its Scale Economies are limited relative to the largest banks. And while it’s respected, it doesn’t have a Brand advantage that lets it consistently charge more than competitors for the same product.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re tracking whether M&T is staying true to what made it work, two measures tell you quickly if something is changing.

Efficiency Ratio: a window into whether M&T is converting its franchise into profit with the operational discipline it’s known for. If this gets materially worse, something is happening—either costs are rising faster than the bank can manage, or revenues are under pressure.

Net Charge-Off Ratio: the cleanest, least-spinnable read on underwriting. If this starts rising meaningfully and persistently, it’s usually a sign the bank has either expanded risk appetite or lost some of its edge in credit judgment. Either way, it would suggest a drift from the very behavior that has historically made M&T different.

XI. Epilogue: The Future of Regional Banking

So what does M&T’s story really tell us about American banking?

Start with this: there isn’t one winning blueprint. The megabanks win with scale, technology budgets that look like small countries, and global reach. Community banks win with intimacy—deep local knowledge, narrow focus, and personal service. M&T built a third model in the space between them: regional scope, relationship-led banking, a conservative risk culture, and growth driven by disciplined acquisition rather than chasing whatever the market is paying for this year.

The question now is whether that middle ground can still hold.

Pressure is rising from both sides. At the top, the largest banks can spread compliance and technology costs across massive balance sheets. At the bottom, fintechs and smaller banks can move faster, specialize more narrowly, and sometimes avoid the same overhead. For regionals, it can feel like being squeezed—too big to get much relief, not big enough to enjoy the same scale advantages as the giants.

And yet, M&T has lived through “this model can’t survive” predictions before. Founded in 1856, it made it through the Civil War, repeated financial panics, the Great Depression, and then the modern stress test of 2008—coming out with its identity intact. Each era had its own version of the argument that banking was changing so fast the old rules didn’t matter anymore. M&T’s history is basically a long rebuttal: cycles change, tools change, but the need for sound judgment doesn’t.

That’s also why the community-banking mission that sparked M&T’s founding still matters. Small businesses still need credit decisions made by people who understand their industry and their local economy. Families still want an institution they can trust with their financial lives. Communities still benefit when a bank is actually embedded—when it shows up, hires locally, and invests locally—rather than treating the market like a set of coordinates on a spreadsheet. Technology can make banking faster and more convenient, but it doesn’t eliminate the human parts. In some ways, the more digital finance becomes, the more valuable genuine relationships can feel.

Which brings the story to its real hinge point: leadership. The handoff from Robert Wilmers to René Jones won’t be judged by any single quarter or integration milestone. It’ll be judged by whether the culture survives contact with scale. Wilmers built a system over thirty-four years, but any institution that depends on one person’s force of will is brittle. The real test is whether M&T’s habits—prudence, patience, and a willingness to say “no”—have become institutional DNA, not just a legacy people talk about.

For investors, that translates to a proposition that’s rarely flashy but has historically been powerful: patient compounding in conservative banking markets, with a bias toward durability over drama. You may not get the highest highs of the most aggressive competitors. But if M&T stays true to what made it work, you also shouldn’t get the catastrophic lows. Over full cycles, that trade has been the point.

Nearly 170 years after two Buffalo businessmen built a bank to fund long-term manufacturing growth, M&T still runs on the same core idea: know your customers, make prudent loans, build relationships that last, and remember that banking is, at the end of the day, a business of trust. In an industry that has never been short on excess—or consequences—that simple philosophy has turned out to be not just admirable, but unusually durable.

XII. Recent News

M&T’s recent results have looked a lot like the environment it’s operating in: steady, but not effortless. Full-year 2025 performance pointed to a bank that kept its footing through a tougher interest-rate backdrop and the lingering, very real costs of digesting People’s United.

On the merger front, the heavy lifting is largely done. The People’s United integration is now substantially complete, and M&T has said it’s capturing most of the cost savings it originally expected. The combined bank is tracking in line with the deal’s projections—though management has also been clear that getting there cost more than hoped. That’s the trade with mega-mergers: you don’t just buy scale, you earn it.

Meanwhile, the regional banking shock of 2023 has faded from panic to posture. Deposit flows across the sector have normalized, and fears around unrealized losses in securities portfolios have cooled. M&T came into that period with two advantages that mattered: a deposit base spread across lots of everyday retail and commercial relationships, and a conservative approach to its securities book. In a confidence-driven business, those “boring” choices again proved to be the point.

The other big story is supervision. After the 2023 failures, regulators have turned up the volume on liquidity planning, interest-rate risk, and commercial real estate exposure across regional banks. M&T has responded by continuing to invest heavily in compliance and risk infrastructure, while emphasizing a constructive, stay-ahead-of-it relationship with its primary regulators.

Finally, there’s the long-term fight every bank is in now: technology. M&T has kept investing in digital capabilities without abandoning the thing that historically differentiated it. The message from management has been consistent—use technology to make relationship banking easier to deliver, not to replace it. Automate the routine, free up bankers for higher-value conversations, and keep the human trust at the center of the franchise.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings and Reports - M&T Bank Corporation annual reports and 10-K filings (SEC EDGAR) - M&T Bank Corporation quarterly earnings and 10-Q filings - M&T Bank Corporation proxy statements - Robert G. Wilmers’ annual shareholder letters (1983–2017)

Historical Sources - “The History of M&T Bank” (corporate archives) - Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society collections - Federal Reserve historical records on Buffalo banking

Industry Analysis - American Banker coverage of M&T and regional banking - Federal Reserve research on regional bank consolidation - FDIC historical statistics on bank failures and consolidation

Academic and Research Materials - “Community Banking in the 21st Century” (Federal Reserve conference papers) - Regional banking research from industry firms - Academic work on bank-merger integration and value creation

Media Coverage - American Banker’s “Banker of the Year” profile of Robert G. Wilmers (2011) - Reporting on the People’s United Financial acquisition and integration - Analysis of M&T’s performance during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2023 banking turmoil

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music