Netflix: The Story of How the Algorithm Ate Hollywood

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 1998, and a red envelope slides through a mail slot in suburban America. Inside is a DVD—maybe The Matrix, maybe Saving Private Ryan. It’s a tiny object carrying a very un-tiny idea: that entertainment could be ordered like a product, delivered like a utility, and chosen with the help of software.

Fast forward to today. Netflix has 301.6 million paid memberships in more than 190 countries. Wall Street values it at roughly $392.68 billion—more than Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount Global, and Comcast combined. The same company that once sent executives to Walmart and Costco to buy DVDs at full price just to keep inventory stocked is now one of the most powerful forces in global storytelling.

So how did a DVD-by-mail startup—founded by two guys carpooling through Silicon Valley—turn into the company that rewired the entertainment business?

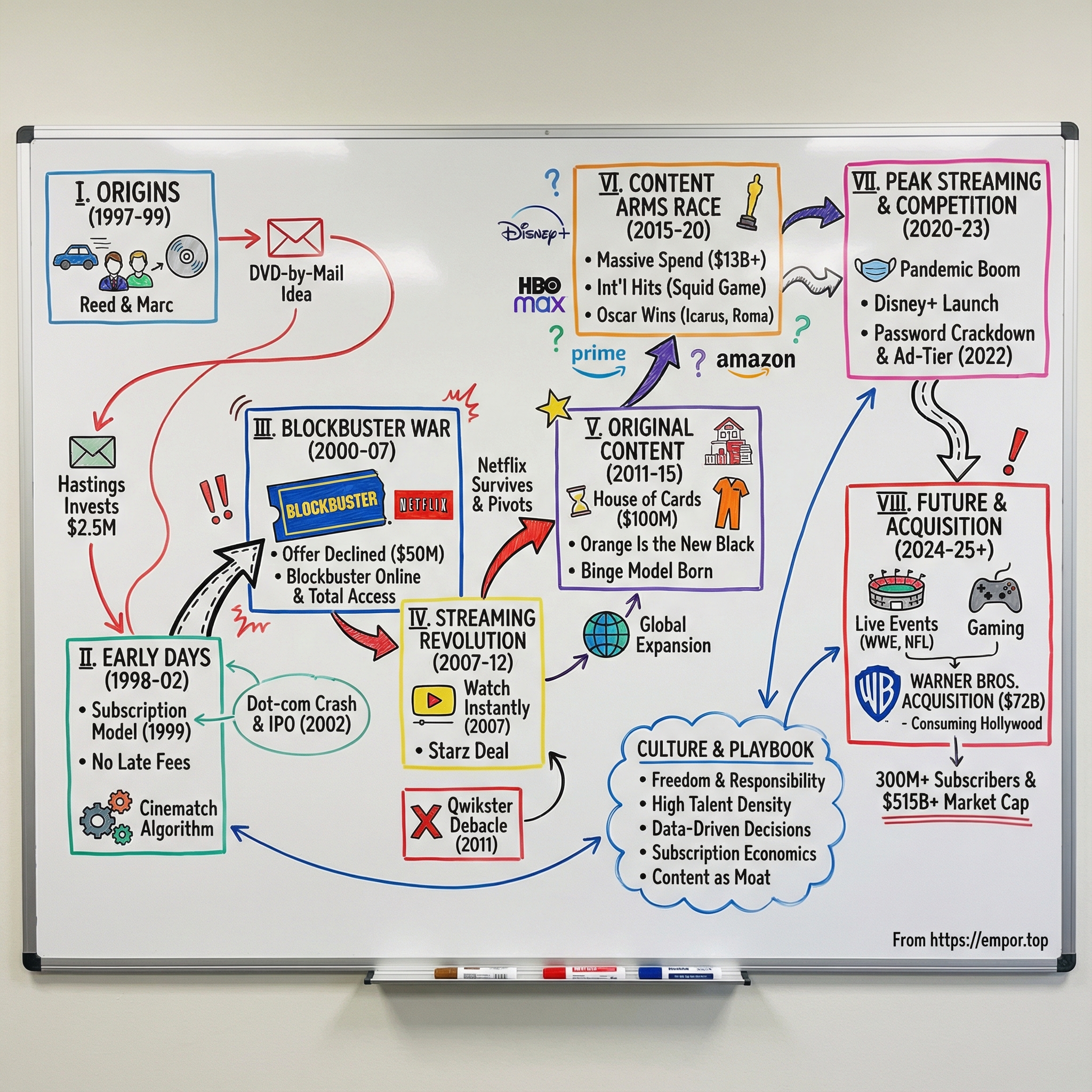

The answer is a chain of bold bets and uncomfortable pivots. A legendary acquisition offer that didn’t happen. A war with Blockbuster that, for a while, Netflix looked like it might lose. A decision to abandon “atoms” for “bits” and bet the company on streaming before streaming was obvious. And then the ultimate power move: not just distributing Hollywood’s content, but making it—at scale, globally, guided by data, and financed with a playbook that looked nothing like the old studio system.

This isn’t disruption as a buzzword. This is disruption as survival strategy: choosing to cannibalize your own business before someone else does it for you. Reed Hastings didn’t build a better video store. He helped make the video store irrelevant. Then Netflix did the same to cable TV. And eventually, it started reshaping the economics of Hollywood itself.

Here’s how we’re going to tell this story. We’ll start at the beginning: 1997, a commute, and a new format called the DVD. Then we’ll move through the early years—subscription, the Queue, and the recommendation engine that quietly became the company’s nervous system. From there: the Blockbuster wars, the leap to streaming, the Qwikster faceplant, and the original-content gamble that began with House of Cards and turned Netflix into a studio. We’ll hit the content arms race, the pandemic surge, and the era of peak competition—Disney+, Amazon, Apple, everyone showing up with deep pockets and famous IP.

Along the way, we’ll also unpack the part of Netflix that rarely shows up on-screen: the culture. The “Freedom and Responsibility” ethos. The management ideas that Silicon Valley copied. The internal logic that made Netflix unusually fast at reinventing itself—and unusually willing to do things that looked reckless from the outside.

And yes, we’ll talk investing. Netflix is a case study in subscription economics, platform dynamics, and what happens when technology meets a traditionally fragmented industry and starts consolidating attention. Since its May 2002 IPO, Netflix has returned 33,668%—turning a $10,000 investment into nearly $3.4 million.

But this isn’t a victory lap. Streaming has matured. Growth is harder. Content is expensive. Password sharing crackdowns and ad-supported tiers are signals that the industry has moved from land-grab to optimization. The question isn’t whether Netflix won. The question is what kind of company Netflix becomes now that everyone understands the game it invented.

So let’s start where every great origin story starts: with two people, a commute, and an idea that sounded almost too simple to work.

II. Origins: Reed Hastings, Marc Randolph, and the DVD Experiment (1997–1999)

Reed Hastings was born in Boston in 1960 into a family with a foot in the American establishment and a streak of rebellion against it. His father served as an attorney in the Nixon administration. His mother came from Boston Brahmin roots, but she taught her kids to roll their eyes at high society, not chase it. That mix—access to elite institutions, paired with disdain for their rituals—would show up later in how Hastings thought about status, hierarchy, and how companies should run.

After high school, Hastings zigged where most of his peers zagged: he joined the U.S. Marine Corps. It gave him discipline and a higher tolerance for discomfort, even if it didn’t exactly turn him into someone who loved being told what to do. After his discharge, he joined the Peace Corps and spent two years in Swaziland teaching high school math. That’s Reed Hastings, former Marine, trying to make algebra click for teenagers half a world away. It’s not a straight line to Netflix, but it’s where you can see an early version of the skill he’d later lean on: taking something complex and making it usable for regular people.

Back in the U.S., Hastings headed to Stanford for a master’s in computer science, right as Silicon Valley was accelerating into its modern form. In 1991, he founded Pure Software, which built debugging tools for developers. Not glamorous, but essential—one of those “boring” products that quietly wins because it solves a real pain. Pure grew into a successful company. In 1997, it merged with Atria Software to form Pure Atria, which was later acquired by Rational Software. Hastings walked away with real money—and, just as importantly, the freedom to pick his next obsession.

That’s where Marc Randolph enters.

Randolph was a direct marketing and mail-order veteran, the kind of guy who understood fulfillment, customer acquisition, and the unsexy mechanics of getting physical stuff into people’s hands. He also had the restless energy of a serial entrepreneur—always scribbling ideas, trying angles, searching for something that could be big.

Around the time the Rational deal was settling, Hastings and Randolph both found themselves in a weird in-between: technically employed during the transition, but not exactly busy. For about four months, they carpooled between Santa Cruz and Silicon Valley—an hour-long drive that turned into a rolling idea lab. Randolph wanted to take the Amazon model—browse online, order, ship to your home—and apply it somewhere new. They threw out all kinds of possibilities: customized baseball bats, personalized shampoo, even surfboards. Nothing quite snapped into place.

Then Randolph latched onto DVDs.

In 1997, DVDs were brand new. Almost no one had a player—roughly 300,000 U.S. households. But the format had two properties that mattered more than hype: it was small and it didn’t break like VHS. A movie could be shipped like a letter.

So Randolph ran a test. He bought a compact disc—music, not video, since DVD players were still rare—and mailed it to Hastings in Santa Cruz in a standard greeting-card envelope. Stamp. Drop it in the mail. The disc arrived the next day, intact.

“If there was an aha moment,” Randolph later said, “that was it.”

Because that tiny experiment quietly blew up the assumptions of the entire video rental business. If a disc could survive the postal system, you didn’t need stores on every corner. You didn’t need aisles and end caps and late-fee policing. You needed inventory, software, and the U.S. Postal Service.

Hastings put in $2.5 million from his Pure Atria windfall to get it off the ground. The ownership split reflected the imbalance of inputs: Hastings held 68% and Randolph 30%. Randolph brought the concept and the operational know-how; Hastings brought the capital and the kind of technical credibility that helped attract real engineering talent. People would later debate titles and “who really founded what,” but the practical truth is simpler: without Hastings’s check—and his conviction that this could be more than a quirky mail-order experiment—Netflix never leaves the carpool.

On April 14, 1998, Netflix launched as the first DVD rental and sales website. Thirty employees worked out of a small office in Scotts Valley, California. The catalog offered 925 titles—tiny compared to Blockbuster’s wall of tapes, but for DVDs it was enormous. Customers browsed online, paid per rental plus shipping, and waited a few days for discs to arrive by mail.

The operation was scrappy in the most literal way. Popular releases would run out constantly, because in 1998 there just weren’t that many DVDs in circulation. So executives did what they had to do: they drove to Walmart or Costco and bought discs at full retail price just to keep orders moving. The margins were awful. But early on, Netflix wasn’t optimizing for margin—it was optimizing for trust. If you’re asking customers to believe in a completely new way to rent movies, you cannot miss shipments.

At this point, Netflix was still basically an online video store—convenient, broader selection, no trip to the strip mall. Better, sure. But not yet inevitable. The move that would define Netflix—the model that turned “mailing DVDs” into a machine—was still ahead. For now, they had what every future juggernaut starts with: a working product, a small but real customer base, and a willingness to keep tinkering until they found the version that truly changed the game.

III. Early Days: Building the Machine (1998–2002)

Netflix’s first year was controlled chaos. In 1998 it did just $1 million in revenue—pretty good for a company built around a shiny new disc format most Americans still hadn’t touched, but nowhere near “changing Hollywood.” Then the line started to bend. Revenue climbed to $5 million in 1999, then kept compounding—$35 million in 2000, $75 million, $150 million, and nearing $300 million by 2002.

That curve wasn’t luck. It was Netflix finding the model that turned a quirky DVD-by-mail idea into an actual machine.

At launch, Netflix looked like the existing video-rental business, just with a website and the Postal Service. You paid per disc, got the movie, returned it, paid again. Fine. But also… why bother? Blockbuster gave you the movie instantly, and most people weren’t exactly itching to plan their Friday night three days in advance.

So Netflix changed the game in September 1999: monthly subscriptions. For a flat fee—initially around $15.95 a month—you could rent DVDs with no due dates, no late fees, and no per-rental charges. Watch when you wanted. Send it back when you were done. And then, crucially, Netflix would automatically send the next movie you wanted.

By early 2000, they dropped the pay-per-rental option entirely and went all-in on subscriptions. That was the bet. Not “we’re a slightly better video store,” but “we’re a different category.”

What they removed mattered as much as what they added. Due dates vanished. Late-fee dread disappeared. So did the little internal negotiation every time you considered renting a movie: Is it worth it for just a couple nights? Subscriptions replaced all of that with a much more powerful feeling—unlimited access. Heavy users felt like geniuses. Light users didn’t have to think.

And underneath the customer experience, subscriptions did something even more important: they rewired the business. Blockbuster had to win you back every single transaction. Netflix got paid every month, whether you watched two movies or twenty. That recurring revenue made the company easier to plan, easier to finance, and easier to scale—because the economics weren’t tied to one disc, one weekend, one trip.

Then Netflix stacked on the rest of the system.

The Queue let customers build a list of movies they wanted, turning “what should we watch?” into a plan instead of a browsing session. Serialized delivery meant the next disc shipped automatically as soon as the previous one was returned, keeping a steady rhythm without customers having to remember to reorder. And Cinematch, the early recommendation engine, helped people discover what to watch next—especially important when your catalog was bigger than any physical store and choice could become paralyzing.

To make all of that feel seamless, Netflix had to become a logistics company too. It opened distribution centers around the country and got obsessive about shipping times. The dream was one-day delivery: put a disc back in the mail today, get another one tomorrow. That meant constantly predicting demand, positioning inventory, and optimizing around postal routes—basically doing “analytics” before anyone was calling it that.

Around this time, another moment happened that became Netflix lore. In early 2000, Hastings and Randolph went to Seattle to meet Jeff Bezos. Amazon was the e-commerce giant; Netflix was a fast-growing specialist in DVDs. An acquisition made perfect sense on paper.

Bezos offered between $14 million and $16 million.

Hastings, who owned about 70% of Netflix, said no.

With hindsight, it looks like a supernatural call: passing on a deal that would have turned his stake into roughly $10 million, in exchange for a future that would be worth billions. But in the moment—still unprofitable, still young, still tied to a niche format, with the dot-com boom wobbling—turning that down took real conviction that the machine they were building was bigger than the market could see.

That conviction got tested fast. The NASDAQ collapsed in 2000. Then the September 11 attacks hit in 2001, and the economy sagged further. Netflix had been planning an IPO to fund growth, but the window slammed shut. The company laid off one-third of its roughly 120 employees just to make sure it stayed alive.

And yet, even in the worst of it, DVDs kept taking off. Demand was “growing like crazy,” as Hastings later put it. When people cut back on vacations and nights out, they still wanted entertainment at home. Movie night is cheap comfort, and Netflix was quietly becoming the easiest way to supply it.

By early 2002, Netflix had stabilized. Subscriptions were working, the fulfillment operation was getting smoother, and the path to profitability was no longer a fantasy. On May 23, 2002, Netflix went public on the NASDAQ at $15 a share, raising $82.5 million and valuing the company at around $300 million—already a world away from the Amazon offer two years earlier.

Inside the company, the leadership structure had also settled. Randolph had handed the CEO job to Hastings back in 1999 and moved into product development. It was a clean division: Randolph’s instincts helped shape the experience; Hastings’s discipline and long-term vision drove the company forward. It also meant something important for Netflix’s next era: from here on out, the business would increasingly reflect Hastings’s personality—restless, analytical, and unusually willing to torch yesterday’s success to build tomorrow’s.

Netflix still wasn’t a household name. Blockbuster still owned the landscape with thousands of stores and millions of customers. To most people, Netflix was either unheard of or a niche service for movie obsessives.

But the machine was built. And once you have a machine like that—recurring revenue, a self-perpetuating delivery loop, and software that learns what people want—eventually you start looking at the giant and thinking: why can’t we take this whole thing?

IV. The Blockbuster Wars: David vs. Goliath (2000–2007)

In the summer of 2000, with Netflix still small enough to feel fragile, Hastings and Randolph flew to Dallas for a meeting that would turn into one of business history’s great what-ifs. Blockbuster’s headquarters sat on a polished suburban campus—the kind of place that radiated certainty. This was the king of video rental: thousands of stores worldwide, billions in revenue, and a brand that, for most Americans, was basically synonymous with “movie night.”

Netflix came with a blunt proposal: buy us for $50 million.

But it wasn’t just a sale. It was a partnership pitch. Netflix would run the online business—the website, the fulfillment, the technical infrastructure—and Blockbuster would keep doing what it did best: operating stores. “We would join forces,” Randolph remembered. “We’d run the online business, they’d run the stores.” In other words: you have the customers and the real estate; we have the software and the model. Let’s not pretend we’re going to out-Blockbuster Blockbuster.

John Antioco, Blockbuster’s CEO, listened. Netflix laid out the growth, the early traction, the logic of DVD-by-mail. And when they finished, the room went quiet.

“We’ll consider it,” someone finally said.

But it wasn’t the thoughtful silence of executives weighing strategy. The founders could tell people were trying not to laugh. The meeting went downhill from there.

From Blockbuster’s point of view, Netflix looked like a niche. A clever service for early adopters and movie die-hards, sure—but not the mainstream. The mainstream liked browsing the aisles, grabbing snacks, and taking home the new release right now. Why pay $50 million for a money-losing upstart when the current model was printing cash?

It’s tempting to frame this as obvious corporate blindness, but Antioco wasn’t an idiot. Netflix had proven DVDs could travel through the mail. It hadn’t proven most people would choose that over instant gratification. Blockbuster also had a machine that did more than rent tapes: the stores drove impulse buys and turned physical presence into habit. Netflix, at that moment, still looked like an experiment running alongside the real business.

What Blockbuster missed was the direction of travel. Netflix wasn’t standing still. Subscriptions were rewiring the economics. The Queue and Cinematch were making a large catalog feel navigable. Distribution got faster. And the DVD player base—tiny in 1997—was swelling rapidly as the format went mainstream.

The rejection didn’t kill Netflix. It clarified the mission. If Blockbuster wouldn’t buy them, Netflix would have to out-evolve them.

What followed was an asymmetric war. Blockbuster had money, stores, brand, and a massive customer base. Netflix had focus, speed, and the kind of desperation that makes you relentlessly inventive. When you’re the smaller player, you don’t get to be sloppy. Every decision has to compound.

Blockbuster finally counterpunched in 2004 with Blockbuster Online, a direct shot at Netflix’s subscription-by-mail model. And then, in 2007, it escalated with Total Access: customers could rent online and swap mailed DVDs for free in-store rentals. It was a genuinely strong idea—taking Netflix’s convenience and stapling it to the one thing Netflix couldn’t replicate: instant pickup through thousands of storefronts.

For a moment, it worked. Total Access pulled in about 2 million online subscribers in its first year. Netflix, which had been climbing steadily, suddenly felt the ground shift. In one quarter of 2007, Netflix lost 55,000 subscribers—the first net decline in its history. Randolph later said it plainly: things got “very scary.” “They were hurting us.”

But the numbers underneath the numbers were uglier for Blockbuster. Total Access was losing money—about $2 on every disc rented. Blockbuster was basically funding a price war using profits from the very stores the new strategy was undermining. It was the innovator’s dilemma in real time: the thing that could save the company was also cannibalizing the thing keeping it alive.

And then the deciding blow didn’t come from customers. It came from the boardroom.

Carl Icahn, the activist investor, took a significant stake and got board representation. He went to war with Antioco over compensation—specifically, Antioco’s bonus—arguing it was unjustifiable given Blockbuster’s performance. The conflict dragged through 2006 and into early 2007, until Antioco stepped away in March.

His replacement was James Keyes, a retail executive best known for running 7-Eleven. He didn’t come in as a digital insurgent. He came in as a store operator. With Total Access bleeding cash, Keyes made the fateful choice: pull back the online subsidies and refocus on brick-and-mortar, betting the legacy business could be stabilized.

It was exactly the wrong retreat at exactly the wrong time. As Blockbuster eased off, Total Access lost its punch. Customers who’d tasted convenience looked elsewhere—many of them to Netflix. Meanwhile, the store business kept eroding as habits shifted and DVD demand eventually peaked. Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy in 2010 and, over time, shrank into something like a cultural artifact—eventually reduced to a single franchise store in Bend, Oregon, where people rent physical media with a wink.

Netflix didn’t just survive this era; it came out tougher. The scare of 2007 proved the model could take a direct hit from a far larger rival and keep going. It also burned something into Hastings’s operating system: the biggest threat isn’t the competitor you can see. It’s the next platform shift.

Even as the DVD war raged, Hastings was already preparing Netflix’s next reinvention: streaming.

V. The Streaming Revolution: From Atoms to Bits (2007–2012)

Reed Hastings had always wanted Netflix to end up as a streaming company. Even the name hinted at it. It wasn’t DVDflix or Mailflix. It was Netflix—an internet company hiding inside a logistics business.

But in 1998, that future was science fiction. Broadband barely existed in most homes. Compression was clunky. Streaming a full movie meant watching a loading bar for what felt like a geological era. So DVDs-by-mail weren’t the endgame. They were the bridge: build the brand, build the subscriber relationship, and wait for the world’s bandwidth to catch up.

By the mid-2000s, it finally started to. Tens of millions of households had broadband. Codecs got better. And then YouTube arrived in 2005 and taught everyone the same lesson: people would watch video online even when it looked terrible and buffered constantly. If audiences would tolerate grainy clips with shaky audio, Hastings figured, they’d absolutely show up for real movies the second it became feasible.

Netflix’s first instinct was to meet the living room head-on with hardware. The team built a “Netflix box,” a set-top device that would connect to your TV and download movies overnight so you could watch them the next day. It worked. The prototypes were real.

Then Hastings watched YouTube take off and changed his mind. YouTube was the opposite of polished: low resolution, constant buffering, and still wildly addictive. The takeaway wasn’t “wait until the tech is perfect.” It was “convenience beats perfection.” Netflix killed the hardware project and decided to stream through the internet directly.

In January 2007, Netflix launched streaming on its website. The library was small—around 1,000 movies—and it was included at no extra cost for existing DVD subscribers. The selection leaned older and less prestigious, because studios weren’t about to hand over the good stuff to an unproven platform that might implode.

But the move that mattered wasn’t the catalog. It was the packaging.

Netflix didn’t force customers to make a new decision or pay a separate fee. Streaming was just there, quietly bundled into what people already had. Try it or ignore it. The DVD business kept funding the company while streaming slowly trained customers to expect instant delivery.

Of course, streaming without content is just a technology demo. So in 2008, Netflix landed the deal that made streaming feel real: a pact with Starz. For a reported $30 million a year, Netflix got streaming rights to a much larger slate—thousands of movies and shows, including newer releases like Ratatouille, Superbad, and No Country for Old Men. Overnight, streaming stopped being a curiosity and started looking like a legitimate alternative to cable and the video store.

Inside Netflix, though, Ted Sarandos—by then the company’s chief content officer—treated Starz as borrowed time. The economics were favorable because the industry hadn’t fully internalized what streaming would become. Once it did, the price would go up. Or the door would close entirely. The studios would either demand far more money, or pull their libraries back to build their own services.

Sarandos looked at HBO and saw the real endgame. HBO didn’t win because it had more movies. It won because it had shows you couldn’t get anywhere else—The Sopranos, The Wire, the kind of programming that turned into weekly cultural events and justified a monthly bill. Sarandos started pushing the idea internally: Netflix needed its own “watercooler” content. That sounded ridiculous for a company best known for red envelopes. But it was also the only long-term solution to a future where Netflix didn’t control the thing it was selling.

Meanwhile, the physical-media clock was ticking. DVDs peaked in 2006 and then began their long decline. Retailers cut shelf space. Consumer habits started shifting. Even the Starz deal, as valuable as it was, underlined the core weakness: Netflix’s streaming future depended on licensing content it didn’t own.

Then came 2011—the moment Netflix managed to set itself on fire in public.

Facing rising content costs and wanting to separate the economics of DVDs and streaming, Netflix announced a major price change and a restructuring: the DVD business would be spun out into a separate service called Qwikster. If you wanted both DVDs and streaming, you’d now have two subscriptions, two accounts, and two different user experiences.

Customers revolted. Some bills jumped by roughly 60%, and people didn’t just dislike the increase—they felt tricked. Qwikster became a punchline almost immediately, especially when it turned out the Twitter handle was already taken and was being used to post about smoking marijuana. Netflix’s stock collapsed, dropping from around $300 to below $70. And in a single quarter, Netflix lost 800,000 subscribers.

Hastings went into public apology mode and admitted the Qwikster announcement was badly handled. The spin-off plan was scrapped. The price changes largely stayed, but Netflix reunited the product under one roof. For a while, the narrative was simple: Netflix got arrogant, and the market punished it.

But the deeper story is that 2011 forced clarity. Streaming was no longer an add-on. It was the company. DVDs were still throwing off cash, but they were now visibly the past. The backlash hurt, but it also stripped away the illusion that Netflix could glide into the future without upsetting anyone. If the company was going to win streaming, it would have to embrace the uncomfortable truth: it couldn’t serve two masters equally, and it couldn’t build a durable future on content it didn’t control.

Netflix came out of that year bruised, chastened, and more focused. And it was about to place the biggest bet in its history: becoming not just a distributor of Hollywood, but a studio.

VI. Original Content: The House of Cards Gambit (2011–2015)

The room was full of Hollywood people doing what Hollywood people do best: politely smiling while silently thinking, Who do these guys think they are?

On one side of the table were the incumbents—HBO, AMC, Showtime—networks that had already built reputations on ambitious, expensive television. On the other side was Netflix, still widely viewed as a tech company that mailed DVDs and happened to be experimenting with streaming. And Netflix wasn’t there to license a show. It was there to make one.

The project was House of Cards: a political thriller based on a British miniseries, adapted by Beau Willimon, with David Fincher attached as executive producer and Kevin Spacey set to star. For the old guard, this was their territory. For Netflix, it was a declaration of war.

Netflix didn’t have decades of relationships with agents, nor a legacy of shepherding scripts through development, nor a shelf full of past hits to reassure talent. What it did have was something the networks didn’t: a mountain of viewing data.

Netflix could see, in its own subscriber behavior, that people showed up for Fincher. They showed up for Spacey. They showed up for political drama, British originals, and morally slippery antiheroes. The algorithm couldn’t tell you if a show would be great—but it could tell you, with unnerving clarity, that the ingredients had demand.

Then Netflix did the truly radical thing: it removed the pilot.

Traditional TV ran new shows through a gauntlet. Pitch, pilot, test, rewrite, maybe a short first season if the internal politics lined up and the early numbers didn’t disappoint. It reduced risk, but it also sanded off ambition. You couldn’t build a long arc when you might die after episode one.

Netflix offered something creators almost never got: certainty. Two full seasons upfront. Twenty-six episodes guaranteed before a single frame was shot. The total commitment was over $100 million—an enormous bet for a company that had never produced prestige television at this scale.

The networks couldn’t—or wouldn’t—match it. Their structures were built around gatekeeping and incremental commitments. Netflix’s structure let it make one big swing.

And Netflix didn’t just change how shows got made. It changed how they got released.

On February 1, 2013, Netflix dropped all thirteen episodes of House of Cards at once. No weekly drip. No cliffhanger scheduling. Just: here’s the season, enjoy.

Even inside Netflix, it was controversial. Would people binge in a weekend and cancel? Would the cultural conversation burn hot and fast, then disappear? Netflix’s bet was that the product was the habit. Give people the control, and they’d never want to go back. Binge-watching wouldn’t be a gimmick—it would become the default.

The bet worked. House of Cards landed with critics, with viewers, and with the broader industry’s attention. It brought in waves of new subscribers who wanted to see what Netflix had built. And in July 2013, the Emmys did the thing that really mattered: they legitimized it. House of Cards earned nine nominations at the 65th Primetime Emmy Awards, becoming the first original online-only streaming series to receive major nominations. For the first time, the establishment had to treat Netflix like it belonged.

Then Netflix proved it wasn’t a one-off.

In July 2013, it released Orange Is the New Black, a comedy-drama set in a women’s prison. Netflix didn’t publish traditional ratings, but it said the audience was comparable to successful cable and broadcast shows—and the industry believed it, because the cultural footprint was obvious. Orange didn’t just perform; it signaled breadth. Netflix could do prestige political drama, but it could also do big, bingeable, addictive entertainment.

That’s when Ted Sarandos put the ambition into one sentence: “Part of our goal is to become HBO faster than HBO can become Netflix.”

It wasn’t just a quote. It was a strategy. HBO had spent decades training audiences to pay a monthly fee for a brand defined by must-watch originals. Netflix was going to compress that timeline by using its advantages: global distribution, fewer legacy constraints, and a willingness to spend before it had “proof” in the traditional sense.

Talent noticed. For filmmakers and showrunners used to navigating network notes, advertiser sensitivities, and cautious greenlights, Netflix felt different. The pitch was simple: more creative freedom, big checks, and a global stage. And behind the scenes, Netflix could point to something else—its data—arguing that an audience existed even when conventional wisdom said it was “too niche.”

The flywheel started turning. Creators followed the opportunity, which created hits, which attracted more creators.

Over the years that followed, the original engine only sped up. Stranger Things arrived in 2016 and became a cultural phenomenon. The Crown delivered glossy prestige. Narcos brought international scale. Each success tightened Netflix’s grip on its own future: less dependency on licensors, more control over what made people subscribe and stay.

And eventually, the awards followed too. In 2018, Icarus won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature—Netflix’s first Oscar. The following year, Roma won three Academy Awards, including Best Director. Netflix wasn’t just competing with TV networks anymore. It was walking into the film industry’s most sacred rooms and taking trophies off the mantle.

For investors—and for every media company watching—this was the real transformation. Netflix had moved from distributor to creator, from a platform that delivered entertainment to a studio that owned it. That shift would reshape its economics, its competitive position, and the scale of the fight to come.

VII. The Content Arms Race: Scaling the Mountain (2015–2020)

Once Netflix proved it could make hits, it did what it always did next: it scaled.

And the scale was hard for the traditional media brain to even process. In 2018, Netflix produced 240 new original shows and movies. In 2019, that climbed to 371. The content budget hit $13.6 billion in 2021, with projections pointing to $18.9 billion by 2025. This wasn’t “we’re making a few prestige shows.” This was industrialization—Netflix building an always-on factory for global entertainment.

By August 2022, originals made up 50% of Netflix’s overall library in the United States. That wasn’t a side hustle anymore. It was the point. Netflix was steadily moving from renting other people’s stories to owning the thing it sold.

The other multiplier was international expansion—and Netflix didn’t treat it like an export business. Instead of just dubbing American shows and calling it global, it started funding local-language originals with local talent, built for home audiences first. Then something interesting happened: those shows traveled.

Money Heist (La Casa de Papel) came out of Spain and turned into a worldwide obsession. Dark from Germany built a cult following far beyond its borders. Sacred Games showed that Indian originals could be must-watch television for people who’d never set foot in Mumbai.

That global reach wasn’t an accident. Netflix poured money into dubbing and subtitling so the “friction” of foreign-language viewing all but disappeared. And it used its most underrated weapon—the recommendation system—to make international titles feel like personal discoveries, not art-house field trips. You didn’t have to go looking for a German sci-fi thriller; Netflix could put it in front of exactly the kind of viewer who would love it.

Underneath all of this, the technology kept evolving into a competitive advantage. Netflix’s recommendation engine—the descendant of Cinematch—grew far beyond star ratings and genre tags. It tracked behavior: what people finished, what they replayed, where they paused, when they dropped off. That data didn’t just influence what Netflix surfaced on your homepage. It fed decisions up the chain: what to buy, what to greenlight, and how to package it.

It also let Netflix try things that weren’t possible on traditional TV. Black Mirror: Bandersnatch, released in December 2018, turned a hit show into an interactive “choose your own path” experience. The story itself got headlines, but the real flex was infrastructure. Supporting branching narratives smoothly at massive scale wasn’t just a creative trick—it was platform capability. Competitors could imitate the idea, but they couldn’t just license the tech.

Meanwhile, the competitive field was getting crowded. Amazon Prime Video was bundled with Prime shipping, racking up viewers almost by default. Hulu offered current-season TV that Netflix couldn’t replicate. And then there were the rumors: the big legacy giants were coming.

In 2017, Bob Iger made it official. Disney was launching its own streaming service—eventually Disney+. “This is an extremely important, very significant strategic shift for the company,” he said. And the subtext was unmistakable: Disney would pull its content from Netflix. Marvel. Star Wars. Pixar. The animated classics. Titles that Netflix had licensed, promoted, and used as subscriber magnets would soon live somewhere else.

That announcement changed Netflix’s math. Licensed content was no longer just expensive—it was unstable. A hit could disappear when the contract ended, taking some portion of demand with it. In a world where every major studio wanted to be a streaming platform, Netflix couldn’t build its future on being the middleman.

So Netflix accelerated everything. More originals. Faster output. Wider geographic coverage. The company raised prices, raised debt, and shoved billions more into the content engine, because owned content was the only defensible content.

Even the awards push had a business purpose. Prestige helped attract talent that might otherwise stay loyal to the old system. Roma’s Oscar attention signaled that Netflix could be a serious home for filmmakers. Martin Scorsese brought The Irishman to Netflix after other studios balked at the cost and length. Funding auteur visions—without being boxed in by theatrical constraints—became a recruiting strategy.

By the end of the decade, Netflix wasn’t just a streaming service with a few originals. It was a full-blown production apparatus: studios and soundstages across continents, big deals with creators from the Obamas to Shonda Rhimes to Ryan Murphy, and a library sturdy enough that, in theory, it could survive even if every licensed show disappeared.

The only question left was the one that always shows up when a company scales this aggressively: could the spending keep going, and could the content keep earning the right to exist?

VIII. Peak Streaming: The Pandemic & Competition (2020–2023)

The pandemic hit like gasoline on a fire that was already burning. Overnight, billions of people were stuck at home. Movie theaters went dark. Productions shut down. And the center of gravity in entertainment snapped straight into the living room.

Netflix was the biggest beneficiary. In 2020, it added 36 million subscribers—an acceleration so sharp it made a two-decade-old company look like a brand-new breakout. Whole households fell into the same rituals: Tiger King became group therapy, kids ran Cocomelon on a loop, and adults binged comfort TV like The Office and Friends—especially as the industry’s licensing clock ran out and those shows started migrating to rival platforms.

Of course, COVID didn’t just change demand. It broke supply. Sets closed, schedules slipped, insurance got complicated, and safety protocols became their own production line item. But Netflix had an advantage that only shows up when the world gets weird: it was already operating at such scale, with so much in the pipeline, that it could keep feeding the machine. While smaller services stared at thinning slates, Netflix could keep shipping. And it made that promise explicit: an original film every week of 2021. An audacious cadence—part marketing, part muscle-flex, part necessity. In a world where everything felt uncertain, Netflix wanted your Friday night to be predictable.

Then came the real competitive shockwave.

Disney+ launched in November 2019, just before the world locked down, and the timing couldn’t have been better. Stuck-at-home families didn’t need to be convinced to pay for a service that bundled Disney’s library with The Mandalorian and a steady drumbeat of Marvel series. Disney+ hit 100 million subscribers faster than any streaming platform in history, and it sent a message to every boardroom in entertainment: this isn’t a side project anymore.

The result was the streaming gold rush Netflix had been predicting for years. WarnerMedia rolled out HBO Max. NBCUniversal launched Peacock. Paramount+ emerged from CBS All Access. Apple TV+ went small-but-prestige. The future arrived exactly as Sarandos feared: the studios stopped licensing and started competing. The old Netflix library era—when you could rent Hollywood’s back catalog at scale—was closing.

For consumers, it was a mixed blessing. More services meant more choice, but it also recreated the thing people thought they were escaping. The cable bundle didn’t die; it just got rebuilt with new logos and new monthly charges. “Peak TV” started to feel like “too much TV,” and discovery became its own problem. When there’s endless content everywhere, attention is the scarce resource.

For Netflix, the pressure showed up on multiple fronts. Subscriber growth slowed in mature markets like the U.S. because there were simply fewer new households to win. Content costs kept climbing as every competitor tried to buy the same talent and the same IP. And the password-sharing habit Netflix had long tolerated—sometimes even treated as free marketing—started to look less like a quirk and more like a leak.

Inside the company, leadership evolved to match the new reality. In July 2020, Netflix appointed Ted Sarandos as co-CEO alongside Reed Hastings, effectively putting content on equal footing with technology at the very top. Then, in January 2023, Netflix reshuffled again: Greg Peters and Sarandos became co-CEOs, while Hastings moved to Executive Chairman. Hastings was stepping away from day-to-day operations, but not from the long-term chessboard.

That transition paired with strategic shifts that would’ve sounded heretical in earlier Netflix eras. In November 2022, Netflix launched an ad-supported tier—breaking with its long-held identity as strictly ad-free. The cheaper plan, priced around $6.99 a month, was a signal that the company was entering a different phase of the game. When growth gets harder, you don’t just fight for new viewers; you widen the funnel.

And then came the move customers least wanted and Wall Street most needed: the password-sharing crackdown. Through 2023, Netflix started requiring household verification and charging for sharing accounts outside the home. The backlash was loud. But the outcome was hard to argue with. Many people who’d been freeloading either started paying or lost access, and the feared wave of permanent churn didn’t materialize the way critics predicted.

By the end of 2023, the scoreboard looked different than it had in the euphoric early days of streaming. Disney stopped publicly reporting subscriber numbers—an unspoken admission that “subs at any cost” was no longer the clean victory metric it once was. Many competitors were still burning money in streaming while their legacy businesses shrank, trapped in a brutal transition with no obvious end.

Netflix, meanwhile, had moved from land-grab to discipline. It was still the scale leader by a wide margin, with more than $30 billion in annual revenue and improving margins. The content factory kept running. The streaming wars weren’t over—but Netflix had made it through peak chaos looking less like a disrupted video store and more like what it had been building toward all along: the default global entertainment subscription.

IX. Culture & Management Innovation

The Netflix culture deck became Silicon Valley gospel. Posted publicly in 2009, viewed millions of times, and passed around like contraband in HR circles, the 127-slide presentation laid out a philosophy that people tended to describe in one of two ways: either radically modern, or quietly terrifying.

The core idea was “Freedom and Responsibility.” Netflix said it would hire exceptional adults and then actually treat them that way. No vacation tracking—take what you need. No sprawling expense rules—spend company money like it’s your own. Fewer approval layers—use your judgment and make the call. Netflix also pushed top-of-market compensation, aiming to pay the best salaries available for a given role so people didn’t have to leave just to feel valued.

But the freedom came with a very sharp edge. Netflix didn’t celebrate “good enough.” Its line was explicit: “adequate performance gets a generous severance.” Managers were taught the “keeper test”: if this person told you they were leaving for a competitor, would you fight hard to keep them? If the honest answer was no, Netflix’s view was that you shouldn’t be carrying the role at all.

In practice, that combination produced both speed and controversy. On the upside, it attracted driven, ambitious people who thrived with autonomy. Decisions didn’t crawl up and down org charts. Teams moved quickly, and the company avoided the kind of bureaucracy that turns talent into ticket-submitters. The lack of rules also created a strange kind of accountability: when there isn’t a policy to hide behind, you own the outcome.

On the downside, critics argued it could feel like a culture of fear. The keeper test can live in the back of your mind even if you’re performing well: is my manager fighting for me, or just not annoyed enough to replace me yet? Severance made exits less financially catastrophic, but it was still a system built around continuous evaluation and frequent churn. And it could tolerate “brilliant jerks,” at least for stretches, because the culture elevated performance above harmony.

Hastings later put the philosophy into a book, No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention, co-authored with Erin Meyer. It expanded on how the culture evolved and how it worked day to day, including the “sunshine” principle: bring problems into the open, give feedback directly, assume good intent, and insist on transparency. Internal memos and decision rationales were shared unusually broadly, creating a level of information symmetry most companies only talk about.

A big part of the operating system was what Netflix called “context not control.” Leaders weren’t supposed to micromanage decisions. They were supposed to give people the context—what the company was trying to do, what constraints mattered, what tradeoffs were acceptable—and then let strong decision-makers execute. That only works if you hire for judgment and initiative, and if you invest constantly in alignment so teams are solving the same problem even when they’re acting independently.

This culture wasn’t just a management flex; it enabled the company’s biggest pivots. Moving from DVDs to streaming required fast, coordinated reinvention without waiting for permission. Building an original-content machine meant hiring into areas where Netflix had little institutional muscle, and the compensation philosophy helped pull in talent from Hollywood—people used to different norms, but not allergic to clear leverage and big responsibility.

Whether it was replicable was always the question. Netflix was operating with clean scoreboard metrics—subscribers, engagement, revenue—and it employed people who could work independently. That template may not translate to companies that require tighter coordination, heavy regulatory compliance, or large customer-facing workforces where consistency matters as much as creativity.

From an investor perspective, the culture was both moat and hazard. The moat was speed powered by talent density. The hazard was dependence: as Netflix scaled, could it keep the “Netflix way” intact without it curdling into politics, anxiety, or bureaucracy? Because at this point, the culture wasn’t just how Netflix worked. It was part of what Netflix was.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

If you strip away the red envelopes and prestige TV, Netflix is a case study in subscription economics done at full volume. Most businesses have to “win” the customer over and over, transaction by transaction. Netflix wins once, then earns again every month. That turns customer acquisition from a one-time expense into an upfront investment you recover over years, not days. It also creates what Wall Street loves: recurring revenue you can plan around. And because every play, pause, and finish is a signal, subscriptions produce a steady stream of behavioral data—fuel for both product decisions and content decisions.

The second lesson is the classic build-versus-buy call, played out in public. Early Netflix was largely a distributor: license a lot of other people’s movies and shows, package them in a better experience, and scale fast. It worked—until it didn’t. The moment studios truly understood what streaming was becoming, they raised prices and then started pulling content back to launch their own services. Netflix’s supply chain wasn’t stable, and the company was too big to be at the mercy of suppliers.

So Netflix built. Original production was expensive, risky, and required muscles the company didn’t have yet. But it created something licensing could never guarantee: permanent assets. A hit like Stranger Things doesn’t rotate off the service when a contract expires. And Netflix’s data advantage became far more valuable in a world of originals than in a world of rentals. When you’re the platform, you don’t just know what people say they want—you see what they actually watch, how they watch it, and what makes them come back.

Then there’s platform dynamics. Netflix got to scale before competitors fully mobilized, and that early lead mattered. More subscribers funded more content. More content attracted more subscribers. The flywheel wasn’t theoretical; it was the company. Even when Disney+ launched with some of the strongest intellectual property on earth, Netflix’s advantage was volume and cadence—its ability to keep a steady drumbeat of new releases that was hard for anyone to match.

International expansion added another layer: geographic leverage. Netflix could fund production in lower-cost markets and distribute globally through the same product. A Korean drama could cost far less than a comparable U.S. production and still reach a worldwide audience. The economics are powerful: make it once, ship it everywhere, with marginal distribution costs that trend toward zero.

Technology, meanwhile, wasn’t just “streaming works.” Netflix turned recommendation into a distribution system of its own—one traditional media companies couldn’t easily copy. It used A/B testing to keep improving the product, from what you see on the homepage to how titles are presented. And its production and collaboration tooling—virtualized workflows, cloud-based editing, remote coordination—became especially important when COVID disrupted the industry.

Capital allocation ties all of this together. Netflix funded its content build-out by borrowing heavily for years, stacking debt while cash flow was negative. It was a gutsy bet that today’s spending would become tomorrow’s library—and that the library would eventually throw off real free cash flow. It worked, but it only worked because management believed, early and loudly, that scale in streaming would be decisive.

Finally, the Netflix disruption pattern shows up far beyond TV. It found an industry built on physical distribution, improved the physical model (DVDs by mail), then made the physical model irrelevant (streaming). You’ve seen the same arc in music, books, and software. The investing question is always the same: where is the “DVD-by-mail” phase happening right now—and which companies are building the bridge to “bits” before the rest of the market accepts that the bridge is necessary?

XI. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

To understand Netflix’s position today, you have to separate two things: what the streaming industry structurally looks like now, and what Netflix specifically has that others don’t.

Start with the industry. If you run it through Porter’s Five Forces, the picture is a lot less dreamy than it was in the 2010s. Supplier power has risen as studios, producers, and top talent have realized just how valuable streaming distribution is—and how many bidders there are. Substitutes are everywhere, and they’re not just other TV apps: gaming, social media, and short-form video are all fighting for the same evening hours. Rivalry is intense, with deep-pocketed competitors willing to burn cash for relevance. Buyer power is complicated: it’s easy to cancel, but hard to replace a specific show everyone’s talking about, and that “content lock-in” still matters.

Now look at Netflix through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens and you can see why it keeps coming out on top anyway.

Scale economies are the obvious one. Netflix can spend huge sums on content because it can spread those costs across a global subscriber base that’s now over 300 million. That’s an advantage smaller services can’t manufacture quickly—if you spend like Netflix without Netflix’s scale, you just lose money faster.

Network effects show up in a more subtle way. Netflix doesn’t have the classic “users attract users” dynamic of a social network. But its recommendation system improves as more people watch, pause, abandon, and finish. That feedback loop makes the product better at matching viewers to titles, which improves satisfaction, which reduces churn, which supports more investment. It’s not flashy, but it compounds.

Brand power is also real. “Netflix” isn’t just a company name; in many households it’s the default verb for streaming. That reduces friction when people decide what to pay for, and it supports pricing power—up to a point.

And counter-positioning is baked into the company’s origin story. Netflix beat Blockbuster partly because Blockbuster couldn’t fully match Netflix’s model without undermining the economics of its stores. That same pattern has echoed across the industry: legacy players often have to protect old cash flows while trying to build the new thing.

Against specific rivals, the tradeoffs are clear. Disney+ has arguably the strongest IP portfolio in the world—Marvel, Star Wars, Pixar, the animated classics—but it doesn’t match Netflix’s release cadence, genre breadth, or global production footprint. Apple TV+ has essentially unlimited capital, but a comparatively thin library and a strategy that still feels more curated than comprehensive. Amazon Prime Video is powerful, but it’s bundled with Prime shipping, which makes it both harder to compare directly and, in some ways, less singularly focused—streaming is one piece of a much larger value proposition.

The big financial question sitting under all of this is content spending. Netflix’s content budget has climbed toward $20 billion a year. At Netflix’s scale, you can rationalize that as roughly the cost of keeping a global entertainment subscription fresh—something like $60 per subscriber per year in content investment. The model can work. But it only works if engagement stays high and the service keeps either adding members or extracting more value from the ones it already has.

That’s why international growth remains the clearest runway. The U.S., Canada, and much of Western Europe are mature. There’s growth, but it’s incremental. The next wave is India, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa—huge populations with different price sensitivity and different viewing tastes. The constraint isn’t demand; it’s affordability. A $15 monthly subscription doesn’t translate cleanly in markets where incomes are far lower, so Netflix has leaned into mobile-only plans and cheaper tiers—giving up revenue per subscriber in exchange for reach and volume.

Then there’s advertising, which would have sounded like heresy in earlier Netflix eras. For years, Netflix argued that ads were incompatible with the premium experience. But the ad-supported tier creates a new on-ramp for price-sensitive viewers—people who might otherwise pirate, share passwords, or pick a cheaper competitor. Early signs pointed to incremental revenue potential without blowing up the premium tier, though the long-run balance is still playing out.

Bull case: Netflix has built durable advantages—especially scale—that are extremely hard to replicate. Its subscriber base funds a content engine that keeps the service feeling alive, and that engine, in turn, protects the subscriber base. The brand is synonymous with streaming. International markets offer long runway. And recent moves—ads and password enforcement—suggest management can still adapt the model when the environment changes.

Bear case: Content costs keep rising as the talent market gets more competitive and every platform chases breakout hits. In wealthy markets, saturation limits growth and turns the game into churn management. Streaming may not be winner-take-all; households often subscribe to multiple services, which caps pricing power. The ad tier could dilute revenue if it pulls customers down from premium plans. And the biggest threat might not even be another streamer—time is finite, and gaming and short-form video are brutally effective competitors for attention.

Key Performance Indicators: If you want to track whether Netflix is strengthening its position or just spending to tread water, three indicators matter most: (1) Average Revenue Per Membership (ARM), which reflects pricing power and tier mix; (2) subscriber growth, especially in international markets, which shows whether the addressable market is still expanding for Netflix; and (3) content cost as a percentage of revenue, which reveals whether the content machine is gaining leverage or getting heavier over time. Together, they tell you whether Netflix is widening the moat—or paying more each year just to stand still.

XII. Epilogue & "If We Were CEOs"

Jake Paul versus Mike Tyson didn’t look like a typical Netflix swing. It was live boxing: an aging legend against a social-media provocateur, streaming in November 2024 to a huge audience—and a wave of technical complaints. Buffers. Wavering quality. A very public reminder that “press play” is a different beast when the event is happening right now.

But that’s also why it mattered. The fight telegraphed Netflix’s direction more clearly than any shareholder letter. Live is one of the last places traditional television still has a structural edge. You don’t binge-watch the Super Bowl. Live creates appointment viewing, real-time conversation, and ad inventory that’s worth more because people can’t skip it and spoilers don’t exist.

Netflix was stepping into that arena.

On Christmas Day 2024, Netflix streamed NFL games—its first real shot at America’s most-watched sport. Then, on January 6, 2025, it made the bigger, longer-term commitment: Netflix became the new home for WWE Raw, a weekly institution that had lived on cable television for three decades. The deal was reportedly worth more than $5 billion over ten years.

These aren’t random experiments. They’re calculated bets on what’s scarce in a streaming world. Sports rights are expensive because they deliver the exact thing advertisers pay up for: large audiences watching at the same time, fully aware they’re watching something that’s only happening once. If Netflix wants its ad-supported tier to become a truly meaningful business, live content is the straightest line.

Gaming is the other frontier Netflix keeps poking at. It has acquired game studios, released titles connected to its IP, and bundled mobile games into the subscription at no extra cost. It’s still small compared to the TV-and-film engine, but the intent is clear: test whether Netflix’s brand, distribution, and subscription relationship can stretch into interactive entertainment—another category where time spent can be as valuable as time watched.

So where does it all go from here? Streaming looks like it’s entering a consolidation era. Smaller services that can’t fund content and tech at scale will merge, sell, or shut down. Netflix, with its size and profitability, is more likely to be a buyer than a target. The bigger question is whether streaming stays a high-growth business—or settles into something more like a mature utility, where the wins come from pricing, bundling, and efficiency instead of constant subscriber fireworks.

If we’re taking “founder lessons” from Netflix, one stands out: business model innovation beats product novelty more often than people want to admit. Netflix didn’t invent DVDs. It didn’t invent streaming. It didn’t invent subscriptions. It combined familiar pieces into a new system, then kept rewiring that system as technology improved and consumer habits shifted.

For investors, Netflix is also a lesson in duration and conviction. Buying at the 2002 IPO and holding through the gut-punch moments—the market crashes, the 2011 Qwikster fiasco, the 2022 growth scare—produced returns that are almost absurd in hindsight. The hard part wasn’t identifying the opportunity. It was staying in the trade when, more than once, it looked like the story might be over.

And maybe the biggest surprise is that Netflix’s most copied innovation isn’t a feature—it’s a philosophy. The culture deck. Freedom and Responsibility. The keeper test. Radical candor and transparency. Netflix is remembered as the company that taught the world to stream, but it may end up just as influential for how it taught a generation of companies to hire, pay, and run fast.

Netflix started as two guys in a car, driving through the mountains, wondering if a disc could survive the mail. It ended up reshaping how the world experiences stories—then forcing Hollywood to reorganize itself around a new reality.

The algorithm ate Hollywood. And eventually, Hollywood learned to live with it.

XIII. Recent News

Netflix’s Q4 2024 earnings were another reminder that the company has learned how to win in a slower-growth world. Subscriber additions came in ahead of expectations, and Netflix raised prices across most major markets without triggering the kind of churn that used to terrify the industry.

The ad-supported tier, once treated as a reluctant concession, started to look like a real second engine. Growth and engagement came in faster than skeptics expected—evidence that Netflix can widen the funnel without breaking the premium experience.

On the content side, early 2025 brought new seasons of the big, familiar franchises that keep people subscribed, plus several high-profile film acquisitions meant to own weekends and headlines. And the WWE Raw debut delivered meaningful viewership, validating the live strategy—while also surfacing the same reality the Paul–Tyson event did: live is unforgiving, and the product bar is higher when you can’t buffer your way out of trouble.

Netflix also kept pushing distribution as quietly as it pushes content. New integrations with additional smart TV manufacturers expanded its default presence in the living room, and extended airline entertainment agreements put the app in more “found time” during travel. Behind the scenes, international production hubs in London, Madrid, and Seoul continued to scale up, increasing capacity for local-language hits designed to travel globally.

Meanwhile, the competitive picture started to look less like a gold rush and more like a shakeout. Disney’s move to bundle Disney+, Hulu, and ESPN+ was an open acknowledgment that consumers are hitting subscription fatigue. And Warner Bros. Discovery’s struggles with Max underscored what’s becoming the industry’s central truth: competing with Netflix at Netflix’s scale is brutally hard. The streaming wars aren’t ending—but they do appear to be entering the consolidation phase.

XIV. Links & References

Company Filings: - Netflix Annual Reports (10-K) on SEC EDGAR - Netflix Quarterly Reports (10-Q) on SEC EDGAR - Netflix Proxy Statements (DEF 14A) on SEC EDGAR

Recommended Long-form Reading: - No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention by Reed Hastings and Erin Meyer - That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea by Marc Randolph - Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America’s Eyeballs by Gina Keating - Acquired podcast episode on Netflix - Stratechery analysis by Ben Thompson on Netflix’s strategic evolution - Harvard Business School case studies on Netflix and disruption

Key Interviews: - Reed Hastings interviews with Charlie Rose, Reid Hoffman, and Kara Swisher - Ted Sarandos on content strategy at various industry conferences - Marc Randolph on founding Netflix and the company’s early decisions

Industry Analysis: - PwC Global Entertainment & Media Outlook - Parrot Analytics streaming demand data - Antenna subscriber tracking reports - MoffettNathanson media sector research

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music