NRG Energy: The Power Player's Reinvention Story

I. Introduction & Opening Hook

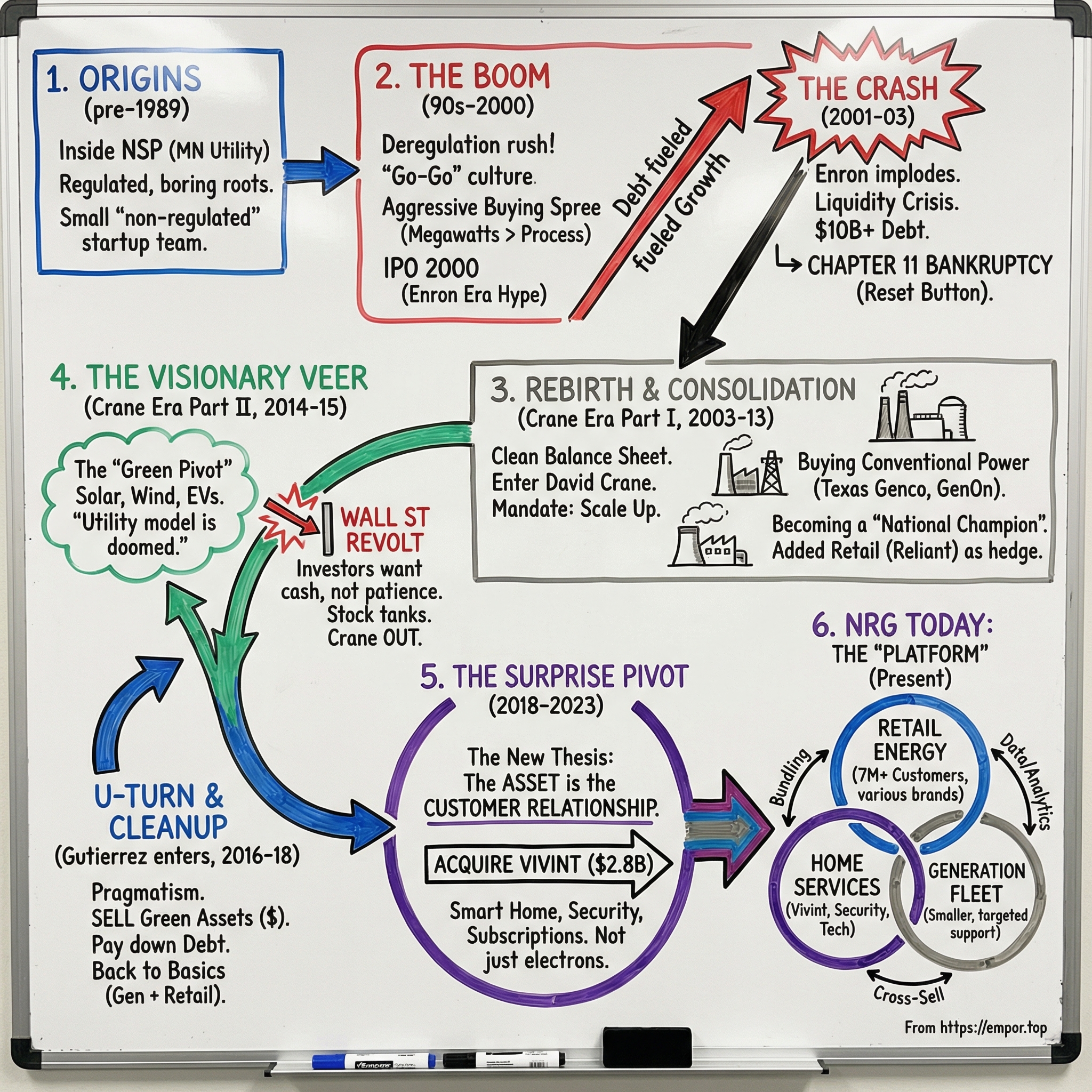

Picture this: December 2015. David Crane is packing up his office at NRG Energy’s headquarters in Princeton. For a decade, he’d tried to will a traditional power company into a clean-energy pioneer. Now the board has pushed him out. The stock is down more than sixty percent from a year earlier. Big investors are furious. And the grand vision of leading America’s energy transition looks, at least in that moment, like a failed experiment.

Now jump to today, and NRG looks like a different kind of success story. The company sits at roughly a $30 billion market cap and nearly $30 billion in annual revenue. But the twist is what would’ve been hardest to predict in 2015: NRG didn’t get there by becoming the renewable darling Crane wanted it to be. It got there by pivoting into something that barely sounds like a power company at all—an essential home services platform that sells electricity alongside security systems and smart home technology to more than seven million customers.

That’s the heart of this story. How does a coal-heavy power producer—born out of a Minnesota utility’s deregulation play—race through a boom, slam into bankruptcy, get rebuilt, then swing for the fences on a green revolution… only to reverse course and re-emerge as a consumer-facing services business? Along the way you’ll find the Enron-era hangover, debt-fueled consolidation, boardroom fights, and, eventually, a very modern wager: a $2.8 billion bet on smart-home subscriptions—doorbell cameras, sensors, and the idea that the most valuable asset isn’t the power plant. It’s the customer relationship.

NRG matters right now because it captures the dilemma facing nearly every legacy energy company in America. Do you chase the renewable future—and risk shareholders who want cash flows and discipline today? Or do you squeeze the existing fleet while the world changes around you? NRG tried both. Not subtly, either. And the whiplash is exactly what makes this such a useful case study in how corporate reinvention actually happens: messily, publicly, and under relentless pressure.

And here’s the most intriguing part: NRG’s end-state so far—owning the customer, bundling services, becoming a platform instead of just an asset owner—might be one of the smartest answers to an industry that’s being remade in real time.

So let’s rewind. Back to a small subsidiary inside a Minneapolis utility. Then forward through an IPO, a collapse, a comeback, a near-reinvention, and finally the pivot that turned NRG into something its founders never could’ve imagined.

II. Origins: The NSP Spinout Story (1989-2000)

NRG’s origin story doesn’t really start in 1989, when the company is formally created. It starts almost a century earlier, with a young electrical engineer named Henry Marison Byllesby.

Byllesby came up in the very first wave of American electrification. He worked with Thomas Edison in those early, chaotic days of building electric companies from scratch, and later with George Westinghouse during the industry’s defining tug-of-war over current systems. Watching all of that up close, he took away a simple, powerful insight: the future wouldn’t belong to a patchwork of tiny operators. It would belong to the companies that could consolidate them.

In the early 1900s, Byllesby moved to Minneapolis and began stitching together small electric and gas utilities across the Upper Midwest. These weren’t glamorous businesses. They lit streetlamps, powered streetcars, and kept small towns running. But Byllesby understood what scale could do—more customers, more predictable cash flow, more leverage to build bigger infrastructure. In 1916, his consolidation drive culminated in the formation of Northern States Power Company, or NSP, which went on to become one of the region’s dominant utilities.

For the next seven decades, NSP lived the classic utility life: steady, regulated, and predictable. It served Minnesota, Wisconsin, and the Dakotas with electricity and natural gas. Regulators set rates. Returns were constrained but reliable. And “strategy” mostly meant doing the utility basics well—build plants, extend lines, and keep up with growing demand.

Then the rules started changing.

The 1980s brought a policy shift that would eventually remake the industry. The Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 had already opened the door to independent power production. By the late ’80s, states were pushing further—experimenting with deregulation and competitive generation markets. The idea was clean on paper: separate generation from the wires, let generators compete on price, and customers would benefit from efficiency and lower costs.

For NSP, that wasn’t just an opportunity. It was a threat. If new competitors could build plants and sell power into markets that NSP had historically “owned” by virtue of regulation, then NSP needed a way to compete outside the old playbook. So in 1989, NSP formed NRG Energy as a wholly owned subsidiary with a very specific job: acquire, build, own, and operate nonregulated power businesses.

To run it, NSP picked Dave Peterson, a seasoned executive, and handed him what amounted to a startup inside a utility—ten people, modest offices in downtown Minneapolis, and a mandate to go find growth that the regulated parent couldn’t pursue. The early work was unglamorous but essential: take minority stakes in independent power projects, learn how development and competitive markets worked, and build muscle in places that looked nothing like Minnesota.

By the mid-1990s, NRG had put together a respectable portfolio—plants and investments spread across the U.S. and abroad. And then, in 1998, the pace changed completely.

Utilities around the country were divesting generating assets to comply with deregulation orders, and NRG was ready to buy. What followed was an acquisition spree that, in hindsight, looks less like a cautious subsidiary and more like a deal machine. NRG bought plants from big names—Niagara Mohawk in New York, San Diego Gas & Electric on the West Coast, Consolidated Edison in New York City—plus a long list of smaller transactions in between. The company was expanding fast, across geographies and technologies, essentially trying to become a major independent power producer in real time.

The culture shifted with it. People inside the company later described this period as a “go-go, entrepreneurial culture”—the opposite of the slow, process-heavy utility mindset at NSP. Deal teams chased everything. The scorecard was simple: megawatts acquired, markets entered.

By 1999, NRG had become a serious player. It held interests in more than eighty generating facilities and had built a footprint of over 20,000 megawatts of capacity, spanning the United States, Latin America, Europe, and Asia.

NSP decided it was time to turn that growth into a public story. In June 2000, NRG went public in what was then the largest IPO in Minnesota history. It raised $423 million. NSP kept majority ownership, but now NRG had a public stock—currency it could use to keep buying.

And on the surface, the timing looked flawless. Deregulation was gaining momentum. Electricity trading was becoming the hot new corner of the market. California’s early competitive-market experiment was producing both chaos and opportunity. And companies like Enron had convinced Wall Street—at least for the moment—that energy trading could mint extraordinary returns.

NRG stepped into the new millennium feeling unstoppable. Revenue had grown from $104 million in 1996 to nearly $3 billion by 2001. The company had thousands of employees, assets on multiple continents, and the swagger of a business riding a once-in-a-generation industry shift.

But the same strategy that powered that growth had quietly loaded the company with risk. The debt used to fund the buying spree had ballooned—from $212 million in 1996 to $8.3 billion by 2001. NRG was now heavily dependent on strong power prices and flawless operations to keep servicing its obligations.

And in markets like this, when conditions turn, they don’t tap you on the shoulder. They pull the rug out.

III. The Enron Effect: Bankruptcy & Phoenix Rising (2001-2003)

In the autumn of 2001, Enron’s seemingly invincible machine started to wobble. First came the murmurs about off-balance-sheet partnerships. Then the story accelerated into something uglier: systemic fraud. By December, Enron filed for bankruptcy—at the time, the biggest in U.S. history—and the energy-trading markets it helped popularize didn’t just cool off. They froze.

NRG wasn’t accused of wrongdoing. But it lived in the same world Enron had defined: a world built on confidence, liquidity, and cheap credit. When Enron collapsed, counterparties pulled back. Banks tightened terms. Suddenly, the financial engineering that had made leveraged power companies look brilliant started to look reckless.

NRG was particularly exposed because its growth had been financed the old-fashioned way: by piling on debt. The acquisition spree of the late ’90s worked as long as power prices stayed high and refinancing stayed easy. When wholesale power prices slid from their peaks and lenders turned cautious on anything energy-related, NRG got squeezed from every side at once—lower cash flow, fewer financing options, and an unforgiving debt load that didn’t care about market cycles.

Its parent company, Northern States Power, had just become part of Xcel Energy after a 2000 merger. Xcel’s regulated utility business was steady. But owning NRG was becoming an anchor. Quarter after quarter, the story was the same: write-downs, covenant problems, and emergency talks with creditors. What had looked like a brilliant deregulation-era growth engine was now threatening to contaminate the entire enterprise.

By 2002, the situation was unraveling. NRG missed debt payments. Asset sales didn’t bring in enough to matter. Leadership churned as executives looked for lifeboats. And by early 2003, the only real uncertainty was timing.

On May 14, 2003, NRG filed for Chapter 11 protection in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York. It was one of the largest power-company bankruptcies in the country. The filing listed more than $10 billion of debt, and while NRG still owned real, productive plants, the market value of those assets in that moment simply wasn’t enough to cover the stack of claims above them.

For Xcel, the bankruptcy was brutal—but it also drew a clean line. The parent relinquished its ownership stake and wrote off billions. If NRG was going to survive, it would do it without its former owner. The company’s path forward ran through restructuring, and the prize on the other side was independence.

That’s what Chapter 11 gave NRG: a reset button. Painful for the old equity and plenty of creditors, yes—but transformational for the operating company. When NRG emerged from bankruptcy in December 2003, it had wiped out $5.2 billion of corporate debt and another $1.2 billion in claims. The new NRG was smaller, simpler, and—most importantly—no longer suffocating under leverage that assumed boom times would last forever.

It also needed a new captain.

David W. Crane arrived as CEO in December 2003, right as the company was stepping out of Chapter 11. He came from International Power PLC, where he ran North American operations, and he walked in with something NRG badly needed: credibility as an operator, plus distance from the decisions that had led to the collapse.

Crane inherited roughly 15,000 megawatts of generating capacity and a balance sheet that had been dramatically cleaned up. The company still had plants across the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, South Central U.S., and California. Most of the international footprint was gone—sold off in bankruptcy, a forced retreat that, in hindsight, also removed a lot of complexity.

And almost immediately, the turnaround showed up in results. In 2004, NRG generated $2.36 billion in revenue and $185.6 million in net income—far better than many expected from a company that had just been written off as another deregulation-era blowup.

For investors who owned the new equity, the message was clear: stripped of its crushing debt, NRG’s core assets could actually throw off real cash. The old NRG had been a casualty of the Enron-era energy bubble. The new NRG was something else entirely—a rebooted power producer with a second chance.

And David Crane now had a platform to build on. The question was what he’d build—and whether Wall Street would let him.

IV. The David Crane Era: Traditional Power Consolidation (2003-2010)

David Crane stepped into NRG in late 2003 with a freshly reorganized balance sheet and a simple mandate: make sure the company never ended up in Chapter 11 again. Over the next several years, he did that by doing something very old-school for a power company—getting bigger, fast.

One of his first moves made that intent obvious. Crane relocated NRG’s headquarters from Minneapolis to Princeton, New Jersey. On paper, it was practical: closer to key Northeast power markets where NRG already owned major assets. In reality, it was also a statement. This wasn’t going to be a Midwest utility offshoot anymore. It was going to be a national competitor.

Not everyone loved it. NRG had grown up inside Northern States Power, steeped in Midwestern utility culture. Princeton felt like a different worldview—more deal-driven, more East Coast, less sentimental. Crane didn’t spend much time trying to soothe the transition. He was building a different company, and he was going to build it at scale.

That mattered because independent power is a commodity business. There’s no brand loyalty to a power plant. If you’re not big enough to buy fuel efficiently, run plants with discipline, and matter to the market operators, you get squeezed—caught between larger fleets with better economics and smaller developers with lower overhead.

So NRG started consolidating.

In 2005, the company added roughly 7,600 megawatts of domestic capacity through acquisitions, including Dynegy’s fifty percent stake in California generation. These weren’t moonshot assets. They were the workhorses of the grid—dispatchable plants that could run when demand surged and prices spiked.

The biggest step-change came a year later. In 2006, NRG acquired Texas Genco, vaulting itself into the top tier of generators in ERCOT, the Texas grid. Texas was the crown jewel of deregulation: fast population growth, real retail choice, and a wholesale market where efficient generation could make real money. Texas Genco also brought a large fleet of coal and natural gas plants—exactly the kind of conventional capacity that, at the time, looked like a foundation you could build on for decades.

Just as important, it planted NRG in what would become its most strategically important battlefield.

Then Crane widened the aperture from megawatts to customers. In 2009, NRG acquired Reliant’s retail electricity business. This was a different kind of asset entirely. Power plants generate electrons; retail businesses own relationships. Reliant brought NRG millions of them—households and businesses buying electricity by choice in competitive markets.

Crane saw the logic immediately. Owning both generation and retail created a built-in hedge. When wholesale prices rose, generation margins expanded but retail got pressured. When wholesale prices fell, retail could hold up better. Either way, the combined company was less exposed to the brutal volatility that had helped break NRG in the first place. And the retail side offered something wholesale generation rarely did: steadier, more recurring cash flow.

In 2010, NRG leaned further into that consumer-facing strategy by acquiring Green Mountain Energy, a Texas-based retailer built around renewable power and environmentally minded customers. Green Mountain was smaller than Reliant, but it gave NRG a foothold in a segment that was starting to matter more—customers who wanted clean energy and were willing to pay for it.

By 2011, the results of Crane’s consolidation era were clear. NRG had grown from roughly 15,000 megawatts when it emerged from bankruptcy to more than 25,000. The company had also simplified dramatically, focusing almost entirely on the U.S. instead of the pre-bankruptcy sprawl across multiple continents. And the generation-plus-retail model was beginning to look like the kind of stabilizing engine public-market investors could understand.

Then Crane decided stability wasn’t enough. He wanted to build a giant.

In 2012 and 2013, NRG swung through two mega-deals. First, it acquired GenOn Energy in a transaction valued at about $1.7 billion, adding a major fleet in the Mid-Atlantic and California and dramatically expanding NRG’s footprint. Then, in 2014, NRG bought Edison Mission Energy’s Midwest generation assets for roughly $2.6 billion—substantial coal-heavy capacity in Illinois and surrounding states, purchased out of another company’s bankruptcy.

When the dust settled, NRG controlled about 46,000 megawatts of generation capacity, making it one of the largest independent power producers in the country. In a little over a decade, the company had gone from bankruptcy to behemoth. Crane had built the national power champion he’d promised.

But even as NRG was stacking up conventional plants, Crane’s focus was drifting toward a very different ambition—one that would define his legacy far more than any acquisition, and eventually cost him the job.

V. The Renewable Revolution Attempt (2010-2015)

By 2010, David Crane had done what he’d been hired to do: he’d rebuilt NRG into a conventional power heavyweight. But the more successful the consolidation got, the more Crane seemed to look past it. The CEO who had spent years buying coal and gas plants started saying, out loud, that the future might not need them.

The timing wasn’t random. The energy world was changing fast enough to feel like a threat, not a trend. Solar costs were dropping hard, pushing rooftop panels from fringe experiment toward something that could actually compete with retail power. Electric vehicles were graduating from novelty to legitimate product category. Smart meters and home energy management were creeping into the mainstream, hinting that the customer might one day manage electricity the way they managed their phone plan. To Crane, the old utility logic—build huge plants, push electrons one way, send a bill—was heading for disruption.

So he set a new target: NRG would lead in renewables and distributed energy. In Crane’s version of the future, solar panels would spread across rooftops, electric cars would charge in garages on clean power, smart meters would enable dynamic pricing and demand response, and—eventually—American transportation would run on renewable electricity.

This wasn’t just talk. By 2013, NRG had developed at least twenty-one clean energy assets totaling more than 2.5 gigawatts. These weren’t symbolic projects designed for a sustainability report. They included utility-scale solar in the Southwest, wind across multiple states, and early moves into distributed solar.

In 2014, Crane made the strategy structural, reorganizing NRG into three divisions. NRG Energy would hold the traditional fleet—about 49,400 megawatts of conventional generation. NRG Renew would house the renewable buildout—roughly 1,300 megawatts of solar and 3,200 megawatts of wind. And NRG Home would bundle the retail electricity business with the newer consumer-facing bets: solar installation services, EV charging, and smart home products.

The reorg was meant to do a few things at once. It would make performance more transparent. It would help investors see that the “new” NRG could be valued differently than the legacy fleet. And it created optionality—if the growth businesses earned it, NRG could potentially spin them out or finance them separately.

Crane described the plan as “positioning to succeed during prolonged period of traditional grid coexisting with distributed generation.” In his mind, the transition would be long and messy: old and new would overlap for decades. NRG would harvest cash from the legacy plants while building the next system in parallel.

But on Wall Street, “both” often sounds like “neither.” The problem wasn’t that the story lacked logic. It was that it demanded two incompatible investment mindsets at the same time. The legacy fleet rewarded tight operations, cash generation, and capital returns. Renewables and home-focused tech demanded constant investment, near-term pain, and patience for payoffs that could take years. Crane was effectively asking shareholders to underwrite both sets of risks, without offering the clean, easy-to-understand thesis of a pure-play in either camp.

The business reflected that strain. Traditional generation still threw off meaningful cash, but renewable returns lagged, and the home initiatives consumed capital to chase growth. And looming over everything was the leverage NRG had accumulated during its deal-heavy expansion, which limited flexibility just as Crane wanted to spend into a new future.

Then came the part that matters most in public markets: the stock. As Crane pushed the transformation narrative harder through 2014 and 2015, skepticism turned into open resistance. Analysts questioned capital allocation. Large shareholders began to lose patience. Activists started paying attention.

Crane, meanwhile, leaned in. His public remarks took on a more urgent, almost missionary tone. He warned about stranded assets and climate risk, criticized the industry’s slow pace of change, and framed the shift as inevitable. It may have been a defensible long-term argument—but it was a tough sell to the institutional investors who owned NRG for stability and cash flow.

By 2015, the revolt had a clear endpoint. The board would have to choose between the visionary strategy and the visionary CEO. And as the stock slid and pressure mounted, that choice was closing in fast.

VI. The Fall of David Crane & Strategic Reversal (2015-2018)

By late 2015, NRG’s stock had fallen more than sixty percent from where it had been a year earlier. Some of that pain came from a rougher energy market. But investors were making something else clear too: they weren’t just worried about the cycle. They were worried about David Crane’s direction. What had sounded like bold leadership now sounded, to them, like overreach.

NRG was spending heavily on renewables and home-focused bets without delivering returns that felt proportionate to the investment. Meanwhile, the core generation business was running into its own reality check—low natural gas prices and weak demand growth squeezing the economics that had once made big thermal fleets look like sure things. On top of all of it sat the debt NRG had taken on to buy GenOn and Edison Mission, limiting flexibility at the exact moment Crane wanted to keep investing in a future that required patience and capital.

Crane’s message was essentially: this takes time. Trust the long view. But public markets don’t award points for vision alone, especially when the share price is collapsing.

That gap between management’s story and investor expectations created an opening for activists. Their argument was straightforward and familiar: NRG wasn’t being valued because it was trying to be too many things at once, and spending like a growth company while carrying the obligations of a leveraged asset owner. Their fix was equally classic—sell what isn’t core, cut costs, pay down debt, and return capital through dividends and buybacks. Stop trying to reinvent the grid. Start maximizing what you already own.

For the board, it was a brutal tradeoff. Crane had undeniably rebuilt NRG after bankruptcy and turned it into a national powerhouse. But the stock chart had become a referendum, and large shareholders were no longer buying the transformation pitch.

In December 2015, NRG announced Crane would step down as CEO. The market’s reaction was immediate: the stock jumped about six percent. It was a clean, harsh signal about what investors wanted—less ambition, more discipline.

Crane’s farewell letter to employees put the emotion on the page: “I did not succeed in leading you... to making NRG that shining city on the hill.” He had believed NRG could be both a major power producer and a pioneer of the energy transition. The market, at least then, wasn’t willing to fund that experiment.

The board turned to Mauricio Gutierrez, NRG’s Chief Operating Officer, as CEO and President. Where Crane had been expansive and evangelical, Gutierrez came in as a pragmatist. His priorities were operational performance, financial simplicity, and credibility with investors.

The first order of business was debt. Gutierrez made paying it down the company’s top priority, because until leverage came down, every strategic option—growth, transformation, even basic capital returns—came with handcuffs.

What followed was a deliberate unwind of Crane’s clean-energy buildout. In 2017, NRG sold its majority stake in NRG Yield, the renewables-focused yieldco Crane had created. The deal brought in more than $1 billion and signaled an unambiguous step back from utility-scale renewables.

Then, in 2018, NRG went further, selling its remaining clean energy assets—solar, wind, and electric vehicle charging—to Global Infrastructure Partners for over $1.3 billion. Much of what Crane had assembled was, in effect, packaged up and handed off.

By the end of the reversal, NRG’s generation portfolio had been reduced to roughly 16 gigawatts. And the composition told the story: nearly ninety percent coal and natural gas, with renewables down to about one percent.

From a market perspective, Gutierrez’s reset worked. The stock stabilized and later recovered as the balance sheet improved and cash went back to shareholders. NRG, it turned out, could be rewarded for picking a lane—even if that lane looked like a retreat from the future.

And yet, the irony lingered. Crane’s timeline had been wrong, and his capital allocation had tested investor patience, but his diagnosis wasn’t fantasy. Solar kept getting cheaper. EVs kept gaining share. Distributed energy kept spreading. The future he’d been trying to position NRG for was still arriving—just with different winners.

So Gutierrez now had to answer the question the divestitures didn’t solve: if NRG wasn’t going to lead with clean generation, what would it become?

The answer would be NRG’s strangest pivot yet.

VII. The Pivot to Essential Home Services (2018-2023)

With the clean energy assets sold and the balance sheet on steadier ground, Mauricio Gutierrez still had the hardest part in front of him: answering the question Crane left behind. If NRG wasn’t going to be the company that led America’s renewables buildout, what exactly was it going to be?

The generation fleet could still make money. But the long-term picture wasn’t comforting. Wholesale power prices were pressured by cheap natural gas and a rising tide of renewable supply, and a portfolio dominated by coal and natural gas came with an obvious shadow: stranded-asset risk.

NRG’s most interesting asset wasn’t a plant. It was people.

Through Reliant and Green Mountain, NRG already had millions of customer relationships—homes and businesses paying monthly bills. Those relationships were expensive to win, hard to replace, and, if you believed the thesis, expandable. If you could sell a customer electricity, why not sell them other recurring services too? Security. Automation. Smart home tech. Make the customer relationship the product—not just the kilowatt-hour.

The idea of turning an energy retailer into a consumer platform had been floating around the industry for years. The problem was that utilities and power companies weren’t built for it. Home services require consumer marketing, subscription retention, and high-touch support—muscles most energy companies simply didn’t have.

Gutierrez’s move was to buy those muscles.

In December 2022, NRG announced it would acquire Vivint Smart Home for $2.8 billion, paying $12 per share for the Utah-based smart home security and automation provider.

Vivint wasn’t a tiny adjacency play. It came with roughly two million subscribers paying monthly fees for things like security monitoring, video doorbells, smart thermostats, and home automation. Vivint installed the hardware, monitored the systems, and handled customer support. In other words: a full-service subscription business with relationships designed to stick.

NRG sold the deal on three core points. First, it would combine NRG’s energy customers with Vivint’s subscribers into a single base of about 7.4 million customer relationships—big enough to matter for cross-selling and to spread customer acquisition costs. Second, Vivint’s subscription model brought predictable monthly revenue, with average customer tenure around nine years—the kind of durability investors tend to reward. Third, it would speed up NRG’s shift from a commodity energy company into something more differentiated: a consumer services platform.

Wall Street hated it. NRG shares fell about sixteen percent on the announcement. Investors questioned the strategy, the price, and the complexity. What does a power generator know about home security? Would management get distracted? Was this another reinvention attempt that sounded better in a deck than in real life?

And honestly, the skepticism had context. NRG’s history was full of bold pivots and mixed results. The Crane-era clean energy push had ended in a sell-off. Retail energy was stable, but it hadn’t been the kind of breakout growth engine that transforms a company’s identity. Adding home security risked looking like one more “convergence” bet.

Gutierrez went ahead anyway. The acquisition closed on March 10, 2023, and the integration started immediately—consolidating back-office functions, merging customer data, and launching cross-sell efforts.

Early signals weren’t uniformly clean. Vivint’s subscriber count dipped slightly as sales practices shifted after the acquisition. And energy-market shocks still had a way of dominating the narrative—Texas’s 2021 winter storm was a recent reminder that the core business could deliver sudden, outsized risk no matter what else you owned.

Still, by late 2024 and into 2025, the strategy began to show traction. NRG reported that customers who took both energy and home services stayed longer and were worth more over time than single-product customers. Cost synergies from combining operations came in better than expected. And Vivint’s technology platform gave NRG new capabilities it could potentially push across a much larger customer base.

In a way, the Vivint deal was Gutierrez’s answer to the same existential question that had driven Crane: what’s a power company’s durable advantage when the industry won’t stop changing? Crane bet on being a leader in distributed clean energy. Gutierrez bet on owning the customer relationship—and staying largely agnostic about where the electrons came from.

It wasn’t guaranteed to be the right answer. But it came with one big feature that Crane’s plan never could: it looked, to investors, like a path to more predictable earnings now—not a request for patience while the future arrived on its own schedule.

VIII. Modern NRG: The Multi-Business Platform (2023-Present)

Modern NRG barely resembles the company that crawled out of bankruptcy in 2003, and it’s a long way from the ten-person deal shop Dave Peterson ran out of Minneapolis in 1989. Today, NRG is less a single “type” of company and more a stitched-together platform: energy retail on the front end, home services alongside it, and a still-meaningful generation fleet underneath—tied together by one unifying asset it’s learned to protect and monetize: the customer relationship.

That platform now spans twenty-four U.S. states and eight Canadian provinces. Roughly seven million retail customers buy electricity through NRG’s collection of brands—Reliant in Texas, XOOM in parts of the Northeast and Midwest, Green Mountain for customers seeking renewable sourcing, Stream and Discount Power for more price-focused shoppers, and Cirro Energy for commercial accounts. On top of that, about two million households subscribe to Vivint’s home services, from security monitoring to smart-home automation and related devices.

What’s notable is that NRG hasn’t tried to collapse everything into one master brand. It runs a portfolio on purpose, using different names to compete in different lanes. Reliant plays big and premium in Texas with heavy marketing and broad awareness. Green Mountain wins customers who will pay more for the promise of renewable power. Discount Power goes straight for the commodity buyer who just wants a lower bill. The point is coverage: NRG can fight across segments without forcing one brand to mean everything to everyone.

Meanwhile, the generation side has been trimmed down from the Crane-era peak. NRG now operates about 13 gigawatts of capacity—still large, but nowhere near the scale it once controlled. The fleet is concentrated in core markets, especially Texas and the Mid-Atlantic, and it plays a strategic role beyond just selling power into wholesale markets. Those plants help support the retail business and act as a physical hedge when power prices swing, smoothing out some of the volatility that can punish a pure retailer or a pure generator.

The other ingredient NRG is leaning into is data. The company has invested in analytics tools like SpaceTag, which uses artificial intelligence to help optimize distributed energy decisions for commercial buildings. In practice, that means analyzing usage patterns, local options, and grid conditions, then recommending the most cost-effective mix of efficiency upgrades, onsite generation, and utility power purchases.

It’s an attempt to evolve the relationship from “we sell you electrons” to “we help you manage energy.” In a commodity business, that kind of positioning matters—especially as customers face more choices, from rooftop solar to demand-response programs to increasingly complex rate structures. Whether this becomes a meaningful new revenue stream or simply a way to keep customers from churning is still an open question. But the direction is clear: differentiation through insight and service, not just price.

All of this works best in deregulated markets, where customers can actually choose their provider. That’s NRG’s arena—and it comes with sharp edges. The company has to keep winning customers through marketing, service, and pricing discipline. There’s no guaranteed return, no captive territory. But if you do it well, success compounds: stronger brands reduce acquisition costs, better retention lifts lifetime value, and scale makes it easier to invest in systems and service that smaller competitors can’t match.

This is the bull case for NRG today: the platform is worth more together than in pieces. Retail energy provides recurring relationships. Generation supports those relationships and can earn wholesale returns. Vivint adds another subscription layer and a cross-sell engine. Data and technology investments offer a path to better retention, smarter pricing, and, ideally, higher margins.

The bear case is just as straightforward. Maybe it’s still a bundle of unrelated businesses with only PowerPoint-level synergies. Maybe the company is still carrying baggage from years of deal-making. Maybe energy volatility and competitive pressure in home services make the earnings stream less “platform-like” than the story implies.

Both can be true at once. NRG has unquestionably pulled off a rare reinvention—from bankrupt generator to consumer-facing services platform. The part that decides the outcome now isn’t the narrative. It’s execution, quarter after quarter, in two unforgiving markets at the same time.

IX. Playbook: Strategic Lessons & Business Model Analysis

NRG’s three-decade arc reads like a field guide to reinvention in a brutally unforgiving industry. It shows what happens when you move too early, too late, or just in a direction your investors didn’t sign up for. A few lessons jump out.

First: the conglomerate curse. This is what happens when management’s vision outpaces investor patience.

David Crane was directionally right about where energy was going. Solar costs kept falling. Electric vehicles kept gaining adoption. Distributed energy did start to nibble at the old, centralized utility model. But in public markets, being right about the future isn’t enough. You also have to survive the present long enough to get there—and convince shareholders to fund the bridge. At NRG, they didn’t. The stock kept sliding, pressure built, and eventually the board chose a different path.

The deeper lesson isn’t “don’t be visionary.” It’s that visionary strategies have to be paired with stakeholder management and clear structure. Crane might have had a better shot with a slower investment ramp, a sharper story, or a cleaner separation between growth businesses and the legacy fleet. Instead, NRG tried to be a clean-energy future company while still operating a large conventional portfolio. That hybrid satisfied almost no one and left investors unsure what they were actually owning.

Second: capital allocation matters more in commodity businesses than almost anywhere else.

Power generation is a commodity business. Electrons don’t carry a logo. That means cost position and balance-sheet resilience are everything. If you’re high-cost, you get squeezed when supply is plentiful. If you’re highly levered, you can get forced into bad decisions at exactly the wrong time. NRG’s bankruptcy was the extreme version of that lesson: heavy debt plus falling power prices plus tightening credit, and suddenly the math just stops working.

After bankruptcy, NRG acted like a company that had learned it. But later, big acquisitions like GenOn and Edison Mission rebuilt leverage, and the Vivint deal layered on more complexity and capital commitment. The tension never really goes away: growth through deals can be tempting, but it can also reintroduce the same fragility that nearly killed the company the first time.

Third: retail energy can be an arbitrage business, but only if you’re great at the mechanics.

In deregulated markets, retailers can profit from the spread between wholesale power costs and what customers pay at retail. NRG’s combined generation-and-retail model also gives it a built-in hedge: when wholesale prices spike, the generation side benefits even as retail margins get pressured; when wholesale prices fall, retail tends to improve even as generation weakens. In theory, that offset should reduce volatility—and investors usually pay more for smoother earnings.

But the catch is execution. Retail margins get eaten alive by customer acquisition costs, credit losses, and service expenses unless you have enough scale and discipline to manage them. NRG’s multi-brand strategy helps it target different customer segments, but it also creates complexity. The open question is whether the retail business consistently earns returns that justify the effort and capital required to keep winning customers.

Fourth: the Vivint deal puts “platform economics” and “generation economics” side by side—and forces NRG to prove the difference.

A power plant is straightforward economics: revenue from selling electricity minus fuel and operating costs, with plenty of exposure to commodity price swings. A platform business is different: customer lifetime value minus customer acquisition cost, where the payoff comes from retention, recurring revenue, and cross-sell over time.

NRG’s Vivint bet was essentially a bet that platform-style economics—sticky subscriptions and higher lifetime value—will be more durable than pure generation economics. If customers who buy both energy and smart home services stay longer, buy more, and cost less to serve, then the deal creates real synergies. If the two businesses mostly coexist without meaningful cross-sell or retention benefits, then NRG didn’t buy a platform—it bought diversification, and paid platform prices for it.

Fifth: in the energy transition, flexibility can matter more than being “right.”

The industry is changing on multiple fronts at once: renewables, batteries, electric vehicles, demand response, and distributed generation. NRG has already tried several strategic identities—Crane’s push to lead the transition, Gutierrez’s pullback to simplify and de-lever, and now a consumer platform approach that’s more agnostic about where the electrons come from. None of these fully resolves what the power company of the future looks like. The best you can do is build a position that can adapt as the ground shifts.

Finally: in energy, regulation and policy aren’t background noise. They’re part of the business model.

NRG plays mostly in deregulated markets, but even “deregulated” doesn’t mean ungoverned. Environmental rules, renewable mandates, capacity market structures, and reliability standards can change the economics of assets quickly—especially for coal-heavy fleets. That means NRG competes not just on operations and marketing, but on navigating a regulatory and political landscape that can swing with elections and public sentiment.

So for investors, the real question isn’t whether NRG has a coherent strategy on paper. It does. The question is whether the integrated generation-retail-home services platform becomes a durable advantage—or whether it’s another waypoint in a company that keeps reinventing itself because the industry refuses to sit still.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Valuation

Understanding NRG means sitting with two very different, very plausible futures. The bull case and the bear case can both be argued convincingly from the same set of facts—which is exactly why the stock tends to stay a live debate.

The bull case starts with the simplest reframe: NRG isn’t trying to be “just” a generator or “just” an energy retailer anymore. It’s trying to look like an essential services platform with subscription-like characteristics.

In that story, the most valuable thing NRG owns is its customer base—millions of households already paying a monthly bill. If you can attach a second and third service to that same relationship—home security, smart home tech, monitoring—you don’t have to re-buy the customer from scratch. You raise revenue per customer without taking on proportional acquisition cost. And if the Vivint integration works the way management says it can, it turns cross-sell from a slide-deck promise into a real engine: more products per household, longer retention, higher lifetime value.

Bulls also point to a tailwind that’s hard to ignore: electricity demand is back in the conversation as a growth market. Data centers and AI workloads are power-hungry. Electric vehicles shift transportation demand onto the grid. Building electrification pushes heating and appliances in the same direction. After a long stretch where demand looked flat, the narrative has changed to: we may need a lot more power, and we may need it faster than the system can comfortably build it.

That matters because new generation takes time—permitting, interconnection queues, construction timelines. In a tighter supply environment, existing plants can become more valuable than people expect. Whatever you think about the long-term environmental trajectory, in the medium term a fleet that’s already online can earn strong returns when the grid is stressed.

The home electrification trend also fits neatly into NRG’s platform pitch. As households add heat pumps, EV chargers, batteries, and smart devices, electricity becomes a bigger share of the home’s budget and a bigger part of daily life. The more complex the home becomes, the more valuable a provider that can bundle service, equipment, monitoring, and support—rather than selling a commodity and leaving the customer to coordinate the rest.

The bear case is anchored in the opposite reality: NRG still has a lot of exposure to fossil fuel generation, and the value of those assets depends on a set of assumptions that could break quickly.

A portfolio dominated by coal and natural gas can print cash in the right market. But its long-term worth is highly sensitive to carbon policy, renewable economics, and storage deployment. If regulation tightens materially, or if clean energy plus batteries keeps getting cheaper and more scalable, then fossil assets can face a double hit: lower utilization and faster obsolescence. In that world, “today’s cash flow” doesn’t translate cleanly into “tomorrow’s durable value.”

Bears also worry about disruption from the edge of the grid. Rooftop solar, community solar, behind-the-meter batteries, and demand response don’t have to replace the grid to cause problems—they just have to reduce how much customers rely on buying commodity electricity from a retailer. NRG’s retail model assumes customers keep purchasing power the old way, even if they switch providers. If more customers start producing, storing, and managing their own energy, the pool gets smaller and the competition for what remains gets nastier.

Then there’s policy and market-design risk. Even in “deregulated” markets, the rules matter, and the rules can change. Environmental regulations, renewable mandates, capacity market reforms, and reliability requirements can reshape economics quickly—especially for coal-heavy fleets. A single shift, like a meaningful carbon price or an accelerated retirement schedule, could force write-downs or compress returns far faster than a spreadsheet assumes.

Execution risk is the other big bear argument, and it’s personal to the current strategy. Vivint is the centerpiece of the platform bet. If customer synergies don’t show up, if subscriber trends keep slipping, or if competition in home security intensifies, NRG risks ending up with an expensive asset that doesn’t actually change the trajectory of the core business. In that scenario, the deal isn’t a platform move—it’s diversification, and not the cheap kind.

Finally, there’s leverage. NRG has a long history of using acquisitions to reshape itself, and acquisitions tend to bring debt with them. Even if the company can service it, leverage reduces strategic freedom at exactly the wrong times—when the industry shifts, when volatility spikes, or when a great opportunity shows up and you can’t pounce. A more flexible balance sheet can buy options; a more levered one forces priorities.

If you run NRG through Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers framework, the picture comes back as mixed. There are some scale economies in running large retail operations—marketing, customer service, billing platforms spread better over a bigger base. Switching costs exist, but they’re not ironclad: energy customers can often change providers without much friction, and home security has real alternatives.

Network effects, in the classic sense, are minimal. One household signing up doesn’t automatically make the service better for the next. Brand power exists, but it’s split across multiple brands rather than concentrated into one dominant identity. And counter-positioning isn’t really NRG’s advantage; if anything, new entrants with simpler models can sometimes position against NRG’s complexity.

The most plausible “power,” if it exists, is process power: hard-earned operational capability in managing a combined generation, retail, and home-services model. If NRG can truly run this integrated machine better than pure-play competitors—pricing energy intelligently, retaining customers, cross-selling services, and coordinating operations—then the advantage compounds over time. The catch is that process power is the hardest to see from the outside, and the easiest for management teams to overestimate.

Porter’s Five Forces also points to a business that’s workable but not cozy. Buyer power is meaningful because electricity is still a commodity for most customers, and retail markets are competitive. Supplier power is moderate. Substitutes are growing as distributed energy and efficiency improve. New entrants face real friction from regulation and capital needs, but competition is still intense—both in retail energy and in home security.

So if you’re watching NRG as an investor, two signals matter more than almost anything else. First: customer economics across the bundle. Do multi-product households actually stay longer and become more valuable, or is the cross-sell story mostly noise? Second: free cash flow relative to the debt load. NRG’s success ultimately depends on whether it can keep paying down obligations, investing enough to make the platform real, and still returning capital—without getting boxed in the next time the industry lurches.

Those two measures—customer lifetime value and cash generation—tell you whether this is becoming a durable platform, or just another clever reinvention that looks better in theory than in the numbers.

XI. Epilogue: What Would We Do?

NRG is staring at the same problem every legacy company faces when its industry starts shifting under its feet: how do you squeeze value from what you already own without missing what comes next? There isn’t a clean playbook for that. There’s only tradeoffs.

On paper, Mauricio Gutierrez’s platform strategy fits what NRG actually has. Not just power plants, but customer relationships at scale, billing infrastructure, and brands that already win in deregulated markets. If you believe the customer relationship is the scarce asset, then expanding from “we sell you electricity” into “we run more of your home” is a logical next step. The alternative—living and dying by generation economics while technology and policy keep rewriting the rules—can look less like a strategy and more like waiting to be commoditized.

But this entire bet collapses if execution doesn’t show up. NRG has to prove the Vivint deal creates value, not just a more complicated org chart. It has to turn “cross-sell” into something you can see in retention, revenue per customer, and margins. And it has to manage the transition risk on the generation side with real timing discipline: retire assets too early and you destroy cash flow; hang on too long and you risk being the last one holding the bag.

The capital allocation posture, at least as described, points in the right direction: reduce debt, keep investing in the platform, and avoid repeating the company’s historic pattern of levering up for the next big narrative. That’s the scar tissue talking. NRG has lived through the downside of leverage-driven expansion, and it has lived through what happens when a bold strategic swing loses investor support. Markets don’t just dislike fragility in commodity businesses—they punish it.

The tension between innovation and optimization is the through-line of this whole story. Crane leaned hard into innovation and got pushed out when the stock collapsed. Gutierrez leaned into optimization and earned back credibility. The platform push is an attempt to blend the two: innovate, but in a way that produces more predictable earnings and doesn’t require shareholders to fund a long, uncertain bridge.

Whether that balance holds is the real question. Maybe it becomes a durable model: a multi-product essential services platform with improving customer economics. Or maybe it’s simply the most recent version of a company that keeps reinventing itself because the industry never stops moving.

Either way, NRG is a reminder of something that’s easy to forget when we talk about “transformation” like it’s a choice. Reinvention at scale is messy. It’s contested. It creates new capabilities and new failure modes. And it rarely ends with a neat, final form.

For investors, NRG is exposure to a bundle of themes that don’t usually sit in the same stock: energy market volatility, a subscription-style home services business, the economics of retail choice, and the always-underestimated importance of capital allocation. The outcome will be driven less by the elegance of the strategy and more by whether the company can execute it while the energy world keeps changing.

One thing does feel safe to say: this story isn’t over. The grid will evolve. Customer expectations will evolve. Policy will evolve. And NRG will be forced to keep making choices—about risk, about investment, and about what kind of company it wants to be. Whether that leads to a lasting end-state or another painful pivot will depend on the same variables that have always governed NRG’s fate: discipline, timing, and the ability to earn the right to keep changing.

XII. Recent News

NRG entered the last couple of years trying to prove a pretty simple point: that “platform” isn’t just a strategy slide—it shows up in retention, cross-sell, and steadier earnings even when energy markets get chaotic. Recent quarterly results have generally supported that direction. Management has pointed to continued progress integrating Vivint, with early signs that bundled customers stick around longer and that cross-sell is starting to move from concept to real behavior.

Texas remains the company’s most important arena, and it’s still a place where the upside and the risk arrive together. The ERCOT market has offered meaningful opportunity when demand tightens and prices rise, but it has also stayed intensely focused on reliability as the system works through the aftermath of the 2021 winter storm. For NRG, that means operating in a market that can reward readiness—and punish mistakes.

On the strategy front, the updates have been less about splashy new pivots and more about sharpening execution. NRG has continued investing in technology, including expanding its SpaceTag analytics platform and building more customer-facing digital tools aimed at improving service while lowering cost-to-serve. The message is consistent: if the customer relationship is the asset, then the experience around it—pricing, support, data, and ease of use—has to get better, not just bigger.

Financially, the tone has stayed disciplined. Debt reduction remains a stated priority, with management emphasizing leverage targets designed to keep the company flexible rather than boxed in.

And the broader environment keeps pushing and pulling at NRG’s portfolio. Regulation remains a constant variable—environmental rules for fossil generation, renewable mandates across states, and changes to capacity market structures all shape the economics around NRG’s fleet and retail offerings. The company has tried to thread the needle publicly: supportive of an orderly energy transition, while arguing that the grid still needs dispatchable generation during the in-between years.

Market demand has also been a tailwind. Rising electricity needs—driven by data centers and broader electrification—have helped strengthen the case for existing generation. Meanwhile, retail customer counts have held steady in a competitive landscape, and the home services business has looked better as integration work has matured.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings

- NRG Energy’s SEC filings on EDGAR, including annual reports (10-Ks) and quarterly updates (10-Qs)

- NRG Energy’s investor relations site for earnings presentations and call transcripts

- Archived filings related to NRG’s Chapter 11 process and its emergence from bankruptcy (2003)

Industry Reports

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reporting on generation, pricing, and U.S. retail electricity markets

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) materials on wholesale market design and regulation

- ERCOT reports and market analyses focused on grid reliability and Texas market dynamics

Further Reading

- Houston Chronicle and Wall Street Journal reporting on NRG’s major strategic shifts over time

- Academic research on U.S. electricity deregulation and how it reshaped market structure

- Industry analysis on the home security and smart home market, including competition and business-model dynamics

Historical Context

- Northern States Power Company historical archives covering the pre-NRG era

- Enron bankruptcy case studies for the broader context of the early-2000s energy-market fallout

- Acquired.fm episodes on adjacent energy and utility stories for useful parallels

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music