Norfolk Southern: Rails, Rust, and Resilience

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

On a freezing February night in 2023, a small town in eastern Ohio lit up with fire and a towering plume of black smoke. In a matter of hours, Norfolk Southern went from Wall Street’s steady, workmanlike railroad to a national symbol of corporate failure. What followed was a familiar American cascade: televised hearings, lawsuits, environmental fear, and a crisis that quickly grew into a bill measured in the billions.

The irony is that Norfolk Southern didn’t become a giant by being careless. It became a giant by being relentlessly good at the unglamorous work of moving freight. By the time that train derailed, the company had built one of the most efficient rail networks in North America: about 19,420 route miles across 22 eastern states and the District of Columbia, moving roughly seven million carloads a year. And yet a single overheated wheel bearing on a cold night was enough to put all of that competence—and the company’s credibility—on trial.

Norfolk Southern Corporation is headquartered in Atlanta and trades on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker NSC. It’s one of only seven Class I freight railroads in the United States—the major leagues of freight—defined by annual revenue of at least $900 million. Together, those seven carriers collect the vast majority of freight rail revenue in the country, making them not just transportation companies, but essential infrastructure. Norfolk Southern, in particular, operates the largest intermodal rail network in eastern North America, linking major Atlantic container ports with inland hubs, Great Lakes terminals, and key Gulf Coast connections—right through the densest population and manufacturing corridor in the nation.

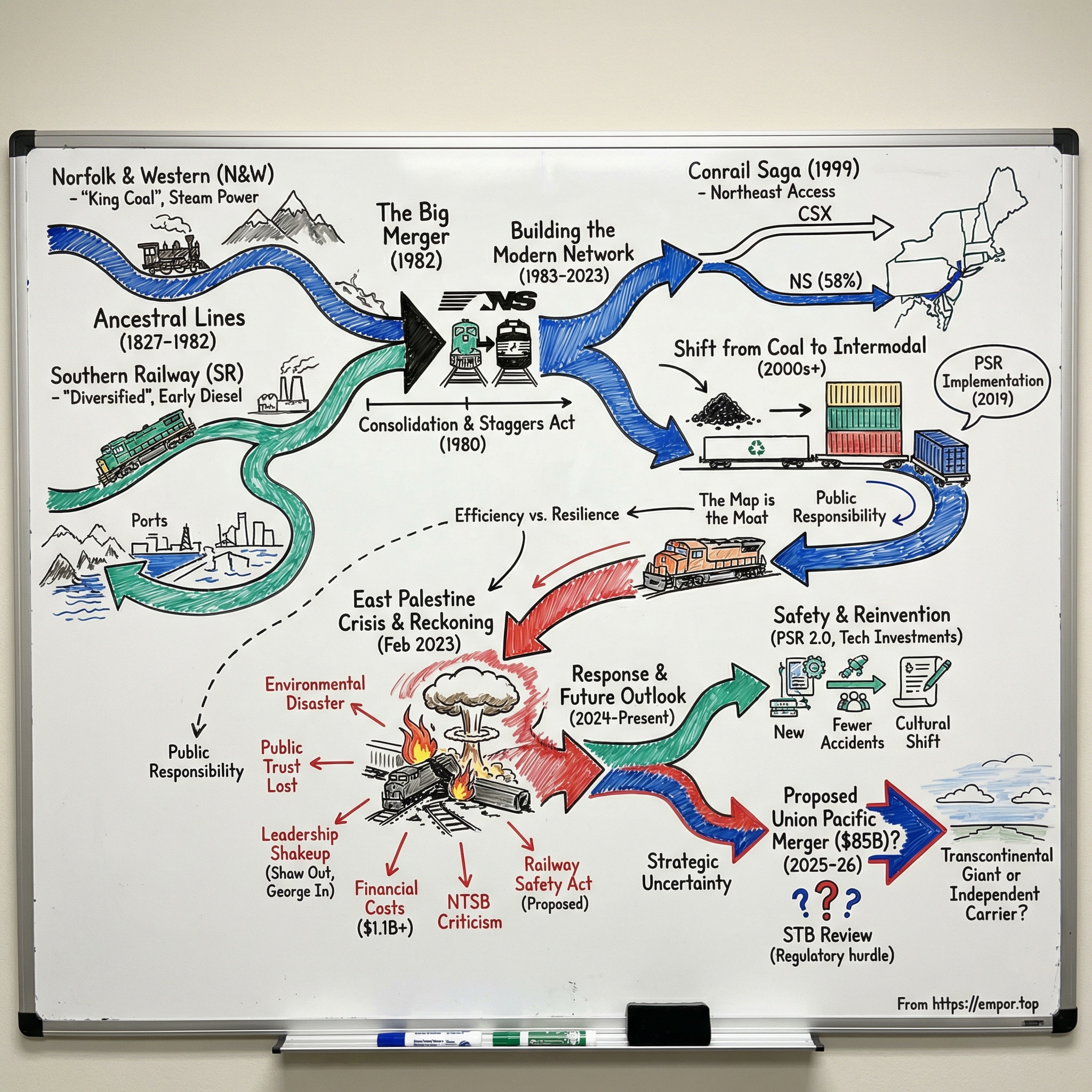

The current Norfolk Southern was created in 1982, when two very different railroads became one. On one side: the Norfolk and Western Railway, a coal-hauling powerhouse forged in the Appalachian mountains. On the other: the Southern Railway, a diversified network across the Southeast with roots stretching back to 1827. Together, they built an Eastern freight machine that would later take a majority stake in Conrail, ride out the long decline of coal, and help turn containerized intermodal shipping into the backbone of modern logistics in the region.

But this isn’t just a story about track miles and throughput. It’s about what happens when the pursuit of efficiency meets the hard edge of public trust. It’s about two railroad cultures forced into a single identity. It’s about deregulation, consolidation, and the hidden systems that make everyday life possible—until they fail in full view.

And now, with Union Pacific proposing an $85 billion acquisition that could create America’s first transcontinental railroad system, the stakes are even bigger. Norfolk Southern’s next chapter might not just determine its own future. It could reshape the entire industry.

So that’s our arc: from nineteenth-century steam to twenty-first-century crisis management, from Appalachian coal to global supply chains stacked in steel boxes. Along the way, the same themes keep returning—consolidation as survival, the tension between shareholder returns and safety, and the question of whether American railroads can reinvent themselves quickly enough to stay indispensable.

How did two regional railroads create an Eastern giant, then nearly destroy their reputation overnight? And can a company with almost two centuries of inherited history rebuild trust while fighting for its independence—or preparing to become part of something even larger? The answers, as always, are in the rails.

II. The Ancestral Lines: Building the Foundation (1827-1945)

On Christmas Day, 1830, a stubby, wood-burning locomotive called the Best Friend of Charleston wheezed its way down six miles of track outside Charleston, South Carolina. People lined up to watch because almost nobody had seen a steam engine move under its own power—let alone carry passengers on a schedule. This was the inaugural run of the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company, chartered on December 19, 1827. And it marked the first regularly scheduled steam-powered passenger train service in the United States.

The idea caught fast. Within three years, the line ran 136 miles to Hamburg, South Carolina—at the time, the longest railroad in the world.

The Best Friend didn’t get to enjoy that legacy for long. Six months later, it met a brutally early lesson in what happens when you treat safety systems like nuisances. According to the period accounts, a fireman—tired of the hiss of the safety valve—sat on it. The boiler exploded, killing him and badly injuring the engineer. American railroading was still an infant, and it was already paying for shortcuts.

That South Carolina railroad is the earliest predecessor of what would eventually become the Southern Railway—one of Norfolk Southern’s two parent companies. But the Southern’s more direct family tree runs through Virginia, starting with the Richmond and Danville Railroad, incorporated in 1847 to connect the state capital to the textile town of Danville.

After the Civil War, the Richmond and Danville did what ambitious railroads did: it expanded hard, stitching together the battered South by buying smaller lines and building new ones. It worked—until it didn’t. By the early 1890s, the system was stretched thin, fragile, and carrying too much debt. Then came the Panic of 1893, the worst financial crisis the country had experienced up to that point. The Richmond and Danville collapsed into receivership, joining nearly 150 other Southern railroads already in bankruptcy.

That’s when J.P. Morgan stepped in.

Morgan didn’t see a graveyard. He saw a blueprint. On July 1, 1894, he organized the Southern Railway, bundling together the Richmond and Danville, the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railway, the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, and dozens of other distressed lines into one coherent system. The new railroad reached across the South and into the Midwest, connecting cities from New Orleans to Cincinnati to St. Louis. It initially owned about two-thirds of the roughly 4,400 miles it operated; the rest ran under leases and working agreements—common practice in an era when railroad maps were as much legal documents as they were transportation plans.

To run it, Morgan turned to Samuel Spencer, a Georgia-born civil engineer who, as The New York Times put it, knew “every detail of a railroad from the cost of a car brake to the estimate for a new terminal.”

Spencer had earned that reputation the hard way. Born in Columbus, Georgia, in 1847, he studied at the University of Georgia and the University of Virginia before his education was interrupted by service in the Confederate cavalry late in the Civil War. He entered railroad work as a surveyor in 1869, rose quickly, and by 1878 was superintendent of the Long Island Rail Road. He later served as president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1887 and 1888. In 1889, Spencer left the B&O to become J.P. Morgan’s personal railroad expert at Drexel, Morgan and Company. Operations, finance, strategy—Spencer could do all three, and in that era, almost nobody could.

From 1894 to 1906, he turned Southern into a disciplined, expanding system. Mileage doubled. Passenger volume climbed to nearly twelve million annually. Earnings tripled, rising from seventeen million to fifty-four million dollars. He pushed the railroad beyond dependence on cotton and tobacco, built modern shops at Spencer, North Carolina—named for him—and poured money into improving track and infrastructure across the network.

Then, on Thanksgiving morning, November 29, 1906, his story ended the way too many railroad stories did: in darkness, on the rails. His private car was crushed in a rear-end collision in Virginia. A coupling failure on the lead car left the train stalled on the track; a following train, in the pre-dawn hours, drove straight into it. Spencer and everyone in his car but one were killed. He was fifty-nine.

Southern Railway employees—thirty thousand of them—contributed to commission a memorial statue by Daniel Chester French, who would later sculpt the Lincoln Memorial. It was dedicated at Atlanta’s Terminal Station in 1910. In the railroad world, that’s what it meant to be a builder: when you were gone, the system kept moving, but the people remembered who made it work.

While Southern was becoming a diversified, modernization-minded network across the Southeast, a completely different railroad identity was forming in the mountains.

The Norfolk and Western Railway traced its roots back to the 1830s, beginning as a short line meant to connect Petersburg, Virginia, to nearby coal deposits. Over the decades, it pushed west into the Appalachian spine of Virginia and West Virginia, following coal seams deeper into the mountains. With financing from Collis P. Huntington in the 1880s and under the leadership of Frederick J. Kimball, the N&W opened the Pocahontas coalfields. Coal didn’t just become an important traffic source—it became the railroad’s personality. Its lifeblood. And eventually, its constraint.

Nowhere was that personality clearer than in the N&W’s devotion to steam power.

As diesel-electric locomotives began to appear in the 1930s, much of the industry leaned into the new technology. Norfolk and Western went the other way. It had an elite mechanical and engineering culture and a belief—supported by years of results—that its steam locomotives were better suited to its terrain, its coal business, and its standards. So instead of buying its future from outside manufacturers, N&W kept designing and building its own steam locomotives at the Roanoke Shops in Virginia, a facility that had been operating continuously since the 1880s and employed thousands of skilled machinists, boilermakers, and engineers.

The masterpiece was the Class J passenger locomotive, introduced in 1941, with fourteen units built through May 1950. They were among the most powerful 4-8-4 steam locomotives ever built, with seventy-inch driving wheels, 300 pounds per square inch of boiler pressure, and about eighty thousand pounds of tractive effort. In theory, they could reach 140 miles per hour. In practice, they were capable of hauling a fifteen-car, 1,025-ton passenger train at 110 miles per hour on level track, producing more than 5,100 horsepower at the tender drawbar.

And N&W treated them like precision instruments. Its engine houses—nicknamed “Lubritoriums”—were famously spotless, more like laboratories than grimy roundhouses. With Timken roller bearings on every axle, the massive J-class engines could be moved by four people pulling a rope. At full output, each locomotive consumed about six and a half tons of coal and nearly 12,000 gallons of water per hour. They carried a Hancock long-bell three-chime “steamboat” whistle whose sound is still instantly recognizable to railfans.

Norfolk and Western held on longer than almost anyone. It wasn’t until 1960 that the railroad retired its last steam locomotives, becoming the last major Class I to complete the shift to diesel-electric power. The lone surviving Class J, No. 611—nicknamed the “Spirit of Roanoke” and the “Queen of Steam”—was donated to the Virginia Museum of Transportation in Roanoke, and later restored for excursion service in 1982 and again in 2015.

Against that, Southern Railway looks like the industry’s early adopter. Southern began dieselization in 1939, ordered its first diesel freight locomotives in 1941, and by June 17, 1953, retired its last steam engine—becoming the first large railroad to convert entirely to diesel.

So by the middle of the twentieth century, the two future parents of Norfolk Southern weren’t just operating in different regions. They were running different philosophies. Norfolk and Western believed in perfecting what already worked, squeezing excellence from proven systems. Southern believed in moving early, embracing what was coming before it arrived. One was forged in coal and mechanical mastery; the other in diversification and modernization.

Eventually, those two cultures would have to become one. And that tension—between tradition and change, between operational perfection and reinvention—would echo through Norfolk Southern for decades.

III. The Great Expansion Era: Norfolk & Western's Growth (1950s-1970s)

In the early 1960s, the boardroom at Norfolk and Western’s Roanoke headquarters revolved around a single, blunt fact: coal paid the bills. N&W hauled more bituminous coal than any other railroad in the country, feeding Midwestern industry and funneling exports through Hampton Roads, Virginia.

But even a coal giant could see the risk in its own success. When one commodity dominates your railroad, it also dominates your destiny. N&W needed reach beyond its familiar north–south coal lanes. It needed access to the Great Lakes and the Midwest’s big industrial markets.

In other words: it needed to stop being only a coal railroad before the coal railroad boxed it in.

In 1964, the opening appeared.

The Nickel Plate Road—officially the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad—ran a fast, well-kept east–west corridor from Buffalo through Cleveland and Fort Wayne to Chicago. It was exactly what N&W didn’t have: a direct, high-quality route into the heart of Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio.

So N&W bought it.

This wasn’t just an acquisition of track and locomotives. It was a ticket into Chicago—the most important rail hub on the continent, where the major freight railroads meet and interchange traffic. With the Nickel Plate, N&W could now carry far more than coal. It could compete for the industrial and merchandise freight that moved between the East and the Midwest. The deal also included the old Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad, which had served Cleveland until 1947, strengthening N&W’s foothold in that Great Lakes orbit.

The network logic clicked immediately. N&W’s coal franchise was enormous, but geographically concentrated—running from Virginia and West Virginia into the Ohio Valley. Nickel Plate gave the system an east–west spine that reached toward Midwestern steel, autos, and agriculture. Together, they could offer something shippers valued more than marketing slogans: a single-line route.

In railroad economics, single-line service is gold. No handoffs to another carrier. Fewer delays. Less paperwork. No haggling over revenue splits. Just one railroad taking responsibility from origin to destination.

But what looked clean on a map was messy in real life. The Nickel Plate had its own culture, its own labor agreements, and its own way of running trains. Integration in railroading isn’t like merging software teams; it’s seniority rosters, union contracts, operating rules, and decades of local practice that don’t budge easily. N&W spent years consolidating duplicate facilities, aligning workforces, and persuading Nickel Plate veterans that the “coal road” out of Roanoke could run an east–west mainline without losing what made it great.

All the while, N&W kept doing what it did best: building a coal empire with the Pocahontas fields of Virginia and West Virginia at the center. Those mines produced some of the highest-quality bituminous coal in the world—valuable for power generation and steelmaking—and N&W’s route to Hampton Roads gave it a direct pipeline to global demand.

Coal wasn’t merely the railroad’s biggest source of traffic. It was the organizing principle. It shaped schedules, locomotive strategy, maintenance priorities, and capital spending. When coal surged, N&W surged with it. When coal cooled, the whole system felt it.

That focus created real strength—N&W’s efficiency moving coal was legendary—but it also created fragility. In the year before the Norfolk Southern merger, N&W earned $291 million, a remarkable result for a regional railroad in the early 1980s. Yet the underlying bet was still the same: that coal would remain the dominant fuel for electricity and steelmaking for the long haul. It was a bet that wouldn’t stay safe forever.

By the mid-1970s, the broader American railroad industry was sliding toward a cliff. Penn Central collapsed in 1970 in what was then the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history, pulling other northeastern railroads down with it. The federal government stitched the wreckage into Conrail and spent billions to keep the region’s freight network alive.

Meanwhile, regulation by the Interstate Commerce Commission left railroads boxed in—unable to adjust rates freely, abandon money-losing lines, or reshape their networks fast enough to fight back against trucks, barges, and pipelines. It was a rulebook built for the monopoly era, now choking an industry in open competition.

N&W stayed profitable, but it wasn’t immune to the direction of the tide. Its leadership came to a hard conclusion: the long-term answer wasn’t just running coal trains better. It was getting bigger—with a partner whose network completed what N&W lacked.

And that partner was close enough to hear the same whistle.

IV. Southern Railway's Parallel Journey (1894-1970s)

If Norfolk and Western was being shaped in the mountains by coal and mechanical perfection, Southern Railway was being assembled like a triage operation for an entire region.

When J.P. Morgan organized Southern in 1894, it wasn’t simply a merger. It was a rescue of Southern transportation itself. Nearly 150 smaller lines—many of them bankrupt or barely functioning after the Panic of 1893—were stitched into one system, run from headquarters in Washington, D.C., and tasked with doing something the old patchwork couldn’t: move people and freight reliably, at scale, across the postwar South.

Southern’s footprint was sprawling. It connected Atlantic and Gulf ports through the Piedmont and the Appalachians and reached into the Midwest, serving major cities like New Orleans, St. Louis, and Cincinnati, plus countless smaller towns that depended on the railroad for everything from mail to manufactured goods. The company also controlled the Alabama Great Southern and the Georgia Southern and Florida, and held an interest in the Central of Georgia. Where N&W built an identity around one dominant product, Southern made its living as a generalist—lumber, textiles, agriculture, finished goods—whatever the economy needed moved.

Leadership mattered, and Southern had a long run of steady hands. After Samuel Spencer’s death in 1906, William Finley led until 1913. Fairfax Harrison followed from 1913 to 1937. Then Ernest E. Norris took over from 1937 to 1951—and under Norris, Southern started to separate itself from the pack with a bet on the future: diesel.

In August 1940, EMC’s new FT freight diesel showed up for demonstration runs, and it didn’t just impress—it rewrote expectations. The four-unit set, rated at 5,400 horsepower, hauled four thousand tons between Cincinnati and Chattanooga, cut an hour off the normal run, and did it with lower fuel costs and far less maintenance than steam. Southern’s leadership had already been leaning that way; the railroad hadn’t bought a new steam locomotive since 1928, an early signal that it believed steam’s best years were behind it.

World War II slowed everything down. The War Production Board restricted locomotive purchases as factories shifted to military needs, forcing Southern to keep its steam fleet going with upgrades and new appliances. But when the restrictions lifted, the pace snapped back. On June 17, 1953, Southern retired its last steam engine, No. 6330, becoming the first large railroad to run an all-diesel fleet—seven years before N&W finally let steam go. It wasn’t just an operational milestone. It was a message to shippers, investors, and competitors: this railroad would spend real money to stay modern.

That identity attracted a particular kind of leader. W. Graham Claytor Jr., president from 1967 to 1977, fit Southern’s culture perfectly. He was a Harvard Law graduate and a decorated World War II naval officer who had served on destroyer escort duty in the Pacific—about as contemporary a résumé as a railroad executive could have. And yet he was also a devoted steam locomotive enthusiast.

That tension—modernizing hard while honoring the romance of rail—showed up in one of Southern’s most famous public-facing choices. In 1966, under president D. William Brosnan, the railroad launched a steam excursion program featuring vintage locomotives including Nos. 630, 722, and 4501. Claytor continued and expanded it, and the program became one of the most beloved railroad heritage efforts in the country. Even more remarkably, the Claytors formed a living bridge between the two future merger partners: his brother, Robert B. Claytor, served as president of Norfolk and Western and later became the first CEO of Norfolk Southern Corporation.

Strategically, Southern’s approach gave it a different kind of strength than N&W. Coal could deliver concentrated revenue and high margins in boom times, but it also tied your fate to one industry. Southern’s diversified commodity mix acted like ballast. When one category sagged, another could pick up the slack.

And its geography turned out to be an even bigger advantage than its product mix. In the 1960s and 1970s, as manufacturing began shifting from the unionized Rust Belt to right-to-work states in the South, Southern found itself sitting on the rails of a growing economy. Auto plants began appearing in Alabama and South Carolina. Distribution centers clustered around Atlanta. Ports like Jacksonville and Savannah surged with imports. Routes that once looked like regional connectors were becoming prime real estate.

Then came a small move that would later matter a lot. In 1974, Southern acquired the original Norfolk Southern Railway, a smaller carrier that had operated in the Carolinas and Virginia since 1942. It wasn’t transformative operationally, but it brought the Norfolk Southern name into the corporate family. Eight years later, when Southern and N&W combined, that name would be pulled off the shelf for the new company—fitting, because it nodded to both parents.

By the late 1970s, Southern was profitable, well-run, and positioned in the country’s fastest-growing region. But management could see what was coming. The industry was consolidating, and railroads that stayed mid-sized risked getting squeezed between larger systems.

When Chessie System and Seaboard Coast Line Industries announced plans in January 1979 to create CSX Corporation, Southern and N&W didn’t wait to see how the chessboard would settle. In April 1979, they announced their own merger plans. The Eastern railroad map was being redrawn in real time—and both companies intended to help draw it.

V. The Staggers Act & The Big Merger (1980-1982)

When President Jimmy Carter signed the Staggers Rail Act on October 14, 1980, America’s railroads finally got something they hadn’t had in decades: room to breathe.

Named for Congressman Harley O. Staggers of West Virginia, the law loosened a regulatory grip that had been tightening since the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. By the late twentieth century, that old system wasn’t just outdated. It was crushing the industry it was designed to oversee.

The long slide was visible in the simplest measure of relevance: railroads’ share of freight traffic, measured in revenue ton-miles, fell sharply from the 1930s to the 1960s. By the 1970s, returns were so thin—around two percent—that raising capital for maintenance, let alone modernization, became a grind. Bankruptcies spread. The Northeast had already required a government rescue in the form of Conrail. The fear in Washington wasn’t theoretical. It was that large parts of the U.S. freight rail network could end up effectively nationalized, not by ideology, but by necessity.

The problem wasn’t that railroads didn’t know what to do. It was that they often weren’t allowed to do it.

Before Staggers, the Interstate Commerce Commission sat in the middle of nearly every business decision. Want to raise prices on a profitable lane to fund repairs elsewhere? You could wait years for approval. Want to abandon a branch line that was bleeding cash? You might be forced to keep running it anyway. Want to offer a big shipper a long-term contract with customized service and pricing? In many cases, you simply couldn’t. The rulebook had been built for an era when railroads were the economy’s bottleneck. By the 1970s, railroads were fighting trucks, barges, and pipelines—and the rulebook hadn’t noticed.

Staggers flipped the incentives. Railroads gained wide latitude to set rates, negotiate private contracts with shippers, and shed unprofitable lines without endless proceedings. It also made consolidation far easier, because once pricing and routing could adapt to reality, scale and network density suddenly mattered even more.

The results were dramatic. In the decades that followed, inflation-adjusted freight rates fell by roughly 44 percent. Market share stabilized and eventually moved back above 40 percent. Returns improved, and investment followed—railroads began pouring billions each year into track, structures, locomotives, and equipment. Even safety metrics moved the right way: train accident rates fell sharply over the long arc from the early 1980s into the 2000s.

This is why Staggers is often described as one of the most successful pieces of transportation deregulation in American history. It didn’t just rescue rail. It turned rail into a modern business again. Warren Buffett’s later view that freight railroads were among the best businesses in the country—and Berkshire Hathaway’s 2009 purchase of BNSF for $44 billion—only made sense in a post-Staggers world.

But deregulation came with a shadow: consolidation.

As railroads got the freedom to rationalize their networks, they did. Class I carriers dwindled from dozens to a small handful. Track mileage shrank as duplicative routes were abandoned. The workforce contracted dramatically. The industry that emerged was leaner, more disciplined, and far more focused on operating efficiency and shareholder returns—the template investors recognize today.

And right as that door opened, Norfolk and Western and Southern were ready to walk through it.

Norfolk Southern Corporation was incorporated in Virginia on July 23, 1980, as the holding company designed to merge the Norfolk and Western Railway with the Southern Railway. The merger officially closed on June 1, 1982, creating the largest railroad in the southeastern United States.

To lead it, the combined company turned to Robert B. Claytor—then president of Norfolk and Western, and brother of Southern’s former president, W. Graham Claytor Jr. It’s hard to imagine a cleaner human symbol for what the merger needed to accomplish. One Claytor had led the coal road. The other had led the diversified Southern carrier. Together, their careers formed a bridge between two proud, very different cultures.

On paper, the strategic logic was almost too neat. Norfolk and Western brought coal expertise and its powerhouse lanes out of the Appalachians, plus expanded reach into Midwestern markets through the Nickel Plate. Southern brought a broad southeastern network, access to ports, and exposure to the South’s growing manufacturing base—along with traffic categories beyond bulk coal. Combined, the new system spanned roughly 18,000 miles of track across 21 states.

In real life, merging railroads is never just connecting dots. It’s operating rules. It’s dispatching philosophies. It’s labor agreements and seniority rosters. It’s which traditions survive and which ones are quietly retired. Norfolk and Western had a reputation for hierarchy, conservatism, and a coal-first mindset. Southern was more diversified and more comfortable with change. Making those approaches coexist—let alone harmonize—required years of careful integration and a lot of political skill.

Even the branding told the story. By 1985, Norfolk Southern locomotives wore a standardized black-and-white paint scheme—a simple, visible declaration that this was now one railroad, even if the people inside it still remembered exactly which side they’d come from.

Claytor also made a quieter but telling choice: he kept Southern’s beloved steam excursion program alive, and he made sure it honored both lineages. Norfolk and Western No. 611 was acquired and overhauled in 1982 for excursion service, and No. 1218 followed in 1987—an olive branch to the mechanical pride of Roanoke and a nod to Southern’s public love affair with its own heritage.

Corporate unification, though, took longer than the celebratory closing date. In 1990, Norfolk Southern Corporation transferred all of Norfolk and Western’s common stock to Southern, and Southern’s name was changed to Norfolk Southern Railway Company. In 1998, Norfolk and Western was formally merged into Norfolk Southern Railway—finally producing one unified railroad. Sixteen years after the merger, the paperwork caught up to the operational reality.

The new headquarters was established in Norfolk, Virginia, and it immediately produced a piece of railroad folklore. When the marble headpiece at the building’s entrance was unveiled—first reported by the Richmond Times-Dispatch on July 12, 1982—people noticed it read “Norfork Southern Railway.” The replacement arrived a few weeks later, but the moment stuck: a billion-dollar merger, and the front door couldn’t spell the company’s name. It was funny. It was humbling. And it was a reminder that integration is won or lost in details.

By the early 1980s, the Eastern rail landscape had effectively narrowed to two giants: Norfolk Southern and the newly formed CSX. Between them, they controlled almost all Class I freight rail service east of the Mississippi.

But the map still had an empty space where the biggest prize sat. The Northeast belonged to Conrail. And the fight to claim it was about to become one of the most dramatic corporate battles in modern American business.

VI. The Conrail Saga: Bidding Wars & Victory (1983-1999)

Conrail was born out of pure panic.

On April 1, 1976, the federal government took the shattered pieces of freight rail in the Northeast—Penn Central plus five other bankrupt carriers—and fused them into the Consolidated Rail Corporation, or Conrail. It was an 11,000-mile system held together with emergency legislation and roughly seven billion dollars in federal support. Plenty of people assumed it would be a permanent ward of the state.

The reason was Penn Central. Its 1970 collapse was, at the time, the largest corporate bankruptcy in American history. The company itself was the product of a “solution” that should have made everyone nervous: forcing together the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central in 1968. They’d competed for a century. Combining them didn’t create a stronger railroad; it created a mess—operationally, culturally, and financially. The network deteriorated, shippers fled, and when Penn Central finally fell over, it threatened to take freight rail service in the entire Northeast down with it.

Conrail inherited that wreckage and then—quietly, relentlessly—pulled off one of the great turnarounds in American industry. Under CEO L. Stanley Crane, the company cut costs, extracted labor concessions, modernized, and by 1981 was profitable.

Once that happened, Conrail stopped looking like a rescue mission and started looking like the best asset on the Eastern chessboard.

In 1987, the government sold its 85 percent stake in what was then the largest initial public offering in U.S. history, raising $1.9 billion. Conrail was no longer a political problem. It was a prize.

Norfolk Southern had been eyeing that prize from the beginning. When the government first moved to sell Conrail in 1984, NS was one of 18 bidders. By February 1985, Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole announced Norfolk Southern as the winning bidder. It looked like NS had pulled off the deal that would finish the Eastern map.

Then the politics hit.

CSX and other competitors fought hard, warning that handing Conrail to a single buyer would create an overwhelmingly powerful railroad in the East. Opposition built, lobbying intensified, and by August 1986, Norfolk Southern walked away. Instead of selling to NS, the government pivoted to privatization via the IPO. Conrail would remain independent—at least for a while.

By 1994, NS was back again, expressing interest. Conrail publicly insisted it wasn’t for sale. Management believed it could grow on its own through a series of expansion initiatives. But those initiatives didn’t produce what they’d promised, and Conrail’s stock lagged its peers. Eventually, the board began to reconsider the obvious: the Northeast was too important, and too contested, for Conrail to stay a standalone forever.

Behind the scenes, confidential talks began. And then the industry got blindsided.

On October 15, 1996, Conrail and CSX announced a surprise merger agreement. CSX Chairman John Snow had gotten there first, offering $92.50 per share in a cash-and-stock deal valued at roughly $8.4 billion, structured as 40 percent cash and 60 percent CSX stock at an exchange ratio of nearly 1.86 CSX shares per Conrail share.

At Norfolk Southern, the reaction wasn’t just anger—it was shock. Chairman David R. Goode later said NS had been in active discussions with Conrail as recently as eleven days before the announcement. In railroad terms, this wasn’t a lost deal. It was an ambush.

Norfolk Southern counterpunched fast. Eight days later, on October 23, 1996, Goode launched a hostile, all-cash offer of $100 per share—about $9.1 billion—beating CSX by nearly a billion. Conrail’s stock jumped 16 percent. Goode made the posture clear: “This proposal is better on every point than the CSX-Conrail proposal announced last week. We are in it to win.”

CSX didn’t fold. It raised its own terms, boosting the cash portion to $110 per share for the initial 40 percent cash component. The bidding war was real, public, and escalating—two Eastern giants trying to keep the other from taking a once-in-a-generation asset.

Then came the twist.

In January 1997, Conrail shareholders rejected the CSX offer and favored Norfolk Southern’s higher bid—a direct rebuke to Conrail’s board, which had unanimously supported CSX. That shareholder revolt forced all three parties back to the table, and what came out of those talks was something corporate America almost never sees: a negotiated draw.

Instead of letting either CSX or Norfolk Southern take Conrail whole, the companies agreed to a joint acquisition and a split. The Surface Transportation Board approved the transaction on June 8, 1998.

The division carved Conrail into two big pieces and a few shared pressure valves. Norfolk Southern took 58 percent of Conrail’s assets—about 7,200 miles of track—most of it tied to the old Pennsylvania Railroad. CSX received the other 42 percent—about 3,600 miles—largely tracing the former New York Central. And in the places where competition was politically non-negotiable, Conrail lived on as a terminal and switching operator through three jointly owned Shared Asset Areas: Northern New Jersey, Southern New Jersey/Philadelphia, and Detroit.

In a strange way, the whole arrangement also symbolically unwound the Penn Central disaster. CSX ended up with one diagonal corridor, and Norfolk Southern with the other: a New York–to–Chicago route anchored by the former Pennsylvania Railroad mainline, plus the New York Central route from Cleveland west to Chicago.

On August 22, 1998, NS and CSX took administrative control. The lines were transferred into two new entities—New York Central Lines leased to CSX and Pennsylvania Lines leased to Norfolk Southern. Full operations began on June 1, 1999, and Conrail’s 23-year run as an independent railroad effectively ended.

Operationally, the transition was brutal. Norfolk Southern wasn’t just absorbing track—it was absorbing different computer systems, different operating rules, different labor agreements, and a Conrail workforce that often felt like it was being carved up rather than welcomed in. Both NS and CSX suffered service disruptions. Trains backed up at terminals. Shipments went missing. The efficiencies everyone modeled on spreadsheets were hard to find in the first messy months of reality.

Strategically, though, it changed everything.

Norfolk Southern suddenly had direct access to the Northeast’s core markets—New York, Philadelphia, and the entire industrial corridor that connects them. Its network now reached from the Atlantic ports and the Southeast up through the Mid-Atlantic and into Chicago and the Canadian border. Including its share of Conrail’s debt and integration costs, Norfolk Southern’s total bill exceeded $6 billion—by far the largest investment it had ever made.

The coal road out of Roanoke had become a true Eastern system.

And the lesson Norfolk Southern carried forward was as clear as it was expensive: when the network-defining asset shows up, you don’t negotiate politely. You fight for it—even if the fight rewrites your company in the process.

VII. Building the Modern Network (1999-2020)

After Conrail, Norfolk Southern entered a long, necessary phase of digestion. The railroad had won the map; now it had to make the map work. The late 1990s and early 2000s became years of optimization—getting terminals humming again, standardizing operations, and smoothing out the rough edges left by a bruising integration.

But the bigger change wasn’t operational. It was existential.

For most of its life, Norfolk Southern’s identity had been coal. At its peak, coal generated more than 60 percent of total revenue. Norfolk and Western’s heritage ran so deep that “King Coal” wasn’t just a nickname; it was practically a business model. Then the twenty-first century arrived with a shift no railroad could dispatch its way around.

Coal’s decline in U.S. power generation accelerated through the 2000s and 2010s. Fracking brought a wave of cheap natural gas. Environmental rules tightened, raising costs for coal-fired plants. Renewables improved and got cheaper. And once utilities began retiring plants, that demand didn’t cycle back. It disappeared.

For Norfolk Southern, the impact landed hard. Coal revenue that had topped $2.5 billion in 2013 began a steady slide. Mines closed across Appalachia, hitting communities that had depended on the mines—and on the railroad jobs that served them.

The coal road had to find a new engine of growth, or accept a smaller future.

That engine was intermodal: moving shipping containers and truck trailers by rail. The concept is simple but powerful. Instead of loading freight into a railcar, you load it into a standardized container or trailer, lift it onto a train for the long haul, then transfer it back to a truck for the last stretch.

Intermodal plays to rail’s fundamental advantage: efficiency over distance. Rail can move a ton of freight dramatically farther on a gallon of fuel than a truck can—roughly 480 miles per gallon per ton for rail, versus around 130 for trucking. As highways clogged, driver shortages worsened, and shippers felt pressure to cut emissions, intermodal went from “nice to have” to strategically essential.

In 2014, Norfolk Southern crossed a symbolic threshold. Intermodal revenue surpassed coal for the first time, reaching nearly $2.6 billion while coal fell by almost $500 million over two years. But this wasn’t just a swap in the revenue pie chart. Intermodal demanded a different railroad.

Coal typically moves in unit trains: long blocks of identical cars going from mine to plant on relatively predictable patterns. Intermodal is a choreography. Many origins, many destinations, tight delivery windows, and constant coordination with trucking at both ends. Different equipment. Different terminals. Different customer expectations. In practice, it’s closer to running a time-sensitive logistics network than a traditional bulk-haul railroad.

Norfolk Southern leaned into that future. It invested heavily in terminals and corridors, including a $60 million expansion of its Rutherford terminal near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. It built out what became the largest intermodal rail network in eastern North America. And it pushed innovations like Roadrailer service, which lets truck trailers ride directly on rail wheels without traditional flatcars, cutting weight and speeding up terminal handling.

Over time, the company’s traffic mix flipped. By 2022, intermodal produced 29 percent of operating revenue; general merchandise—chemicals, automotive, metals, and more—made up 57 percent; and coal had shrunk to 14 percent. The transformation was stark. A railroad once defined by mountains of black coal was now defined by stacks of containers, the visible signature of modern, global supply chains.

That broader mix mattered. Norfolk Southern became a critical conduit not just for consumer goods, but for agricultural exports, automotive supply chains, and chemical distribution. Its major intermodal terminals in Harrisburg, Chicago, Atlanta, and the Crescent Corridor connecting Memphis to New Jersey formed a backbone for containerized freight across the East.

Through all of this, leadership turned over, but the central challenge stayed the same: reinvent the railroad without breaking it. After founding CEO Robert Claytor, Arnold B. McKinnon led from 1987 to 1992. David R. Goode—who had fought the Conrail war—served from 1992 to 2005. Charles “Wick” Moorman took over from 2005 to 2015, followed by James A. Squires from 2015 to 2022. Different styles, different priorities, same underlying reality: the coal era was ending, and the next era would require constant adaptation.

Then, in the late 2010s, another shift swept the industry—one driven less by markets than by management philosophy.

Precision Scheduled Railroading, or PSR, promised a cleaner, leaner railroad. Originated by the influential and polarizing executive Hunter Harrison, PSR emphasized running fewer, longer trains on fixed schedules, reducing the number of railcars, locomotives, and workers needed to move freight.

In plain terms: stop waiting to “build” the perfect train in a yard. Run the railroad like a scheduled network, move cars more directly, and keep assets from sitting still.

Harrison had imposed PSR at Illinois Central, Canadian National, Canadian Pacific, and CSX, and each time it delivered eye-catching improvements in operating ratio—railroading’s favorite efficiency metric, measuring how much of each revenue dollar gets consumed by operating expenses. When Harrison arrived at CSX in 2017, its operating ratio sat in the high 60s; within a year, it was falling toward 60. Wall Street loved the pattern, and the pressure rippled across the industry.

Norfolk Southern embraced PSR in 2019, branding its version as the Thoroughbred Operating Plan, or TOP.

Financially, the story looked compelling. Operating ratios improved. Locomotives were taken out of active service, with 500 eventually placed into storage. Headcount fell. Facilities were consolidated or closed, including the historic Roanoke Locomotive Shop, ending 139 years of operations there, and the Bellevue, Ohio shops.

But the balance sheet wins came with growing unease on the ground. Shippers complained that service deteriorated. Labor unions called the model “unrealistic.” Critics argued the railroad was being tuned for short-term efficiency at the expense of resilience—leaving less slack for disruptions, less tolerance for surges, and less room for maintenance and safety margins.

Those concerns didn’t dominate headlines at the time. They would later. On a cold February night in Ohio, they would come roaring back into view.

VIII. East Palestine: Crisis and Reckoning (2023-Present)

At 8:55 p.m. EST on February 3, 2023, Norfolk Southern Train 32N—a 149-car mixed freight train moving at about 43 miles per hour—came apart on the Fort Wayne Line near East Palestine, Ohio. East Palestine is a village of roughly 4,700 people near the Pennsylvania border. The train had left Madison, Illinois, headed for Conway, Pennsylvania, and the crew had reported for duty in Toledo earlier that afternoon.

Thirty-eight cars derailed. Eleven of them carried hazardous materials. Several cars ignited almost immediately, and the fire spread until it engulfed dozens of railcars, burning for more than two days. The derailment quickly became the most high-profile railroad environmental disaster in the United States in decades—an event that didn’t just scar a community, but forced the entire industry back into the glare of regulators, lawmakers, and the public.

Investigators later landed on a straightforward mechanical cause: a wheel bearing overheated and failed. But the timeline laid out by the Federal Railroad Administration and the National Transportation Safety Board showed how a simple failure became a cascading breakdown in detection and response.

At 7:37 p.m., the train passed a hot bearing detector in Sebring, Ohio, without triggering an alarm. Between 8:11 and 8:14 p.m., a surveillance camera in Salem captured visible fire near the suspect bearing. At 8:13 p.m., a detector in Salem registered a non-critical alert—not a critical alarm. Norfolk Southern’s operating procedures required crew action only on critical alarms.

Nineteen minutes later, the train reached the next detector, in East Palestine, and this time it did trigger a critical alarm. The crew immediately began slowing the train using dynamic braking. But by then, the bearing had already failed catastrophically. The derailment was underway.

The initial damage was severe on its own. Three DOT-111 tank cars—an older design long criticized for poor crashworthiness—were breached, releasing flammable and combustible liquids including butyl acrylates and ethylene glycol monobutyl ether.

But it was a decision made three days later that turned a major accident into a national flashpoint.

Five additional tank cars carried vinyl chloride monomer, classified as a Class 2.1 flammable gas and a known carcinogen. In the days after the derailment, heat from the ongoing fire caused pressure relief devices on those cars to actuate. Norfolk Southern and its contractors became concerned the vinyl chloride was polymerizing.

Polymerization is exothermic—it generates heat—and the fear was of a runaway reaction that could end in an explosion.

The reality, the NTSB later concluded, was far less dramatic. OxyVinyls—the vinyl chloride manufacturer and an affiliate of Occidental Petroleum—sent its own expert to inspect the cars. That expert concluded the probability of polymerization was low, the temperature of the tank car shells was trending downward, and no dangerous reaction was taking place. Laboratory analysis later supported that assessment: none of the twelve residue samples tested showed polymerized vinyl chloride.

Norfolk Southern contractors had recorded a temperature of 58.8 degrees Celsius. In the NTSB’s assessment, that was “not enough to do anything” to the vinyl chloride monomer. Critically, Norfolk Southern did not share the OxyVinyls expert’s dissenting view with local decision-makers.

On February 6, after Ohio Governor Mike DeWine and Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro ordered mandatory evacuations in a one-by-two-mile area around the site, officials chose to conduct a controlled “vent and burn.” East Palestine Fire Chief Keith Drabick, serving as incident commander, was given just thirteen minutes to make the call. He later testified he was “blindsided,” and ultimately agreed after unified command described it as “the least bad option.”

Crews used shaped charges to breach the five vinyl chloride tank cars, drained the contents into a trench, and ignited it with flares. It’s hard to overstate what that moment did to Norfolk Southern. The decision followed the company for years.

The burn produced a massive black cloud visible for miles—the image that defined the disaster. Burning vinyl chloride released hydrogen chloride and phosgene, a chemical used as a weapon during World War I. Hydrogen chloride mixed with water to form hydrochloric acid, and aquatic life in nearby waterways was devastated. An estimated 45,000 animals—mostly aquatic species—died within a five-mile radius. Environmental researchers later reported that chemicals associated with the burn showed up across sixteen states in precipitation and pollution data.

When the NTSB presented its final investigation at East Palestine High School on June 25, 2024, the conclusion was blunt: the vent and burn had been “unnecessary.”

Then came the tone. NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy delivered some of the harshest public criticism a federal safety official has directed at a major railroad in recent memory. She accused Norfolk Southern of “manufacturing evidence” tied to the vent-and-burn decision, threatening the NTSB, and withholding key documents and data from investigators. She said she twice considered issuing subpoenas.

Homendy also described a conversation in which, she said, Norfolk Southern executives told her it was “their hope” the NTSB would “put to rest” the “rumor” that the vent and burn was chosen to speed reopening the rail line—and that the company would “use every avenue and opportunity to vigorously defend their decision making.” People in the room took it as a threat. Homendy called Norfolk Southern’s conduct “unprecedented” and “reprehensible,” and added a line that became its own indictment: “The absence of a fatality or injury doesn’t mean the presence of safety.”

The financial fallout was immense. By January 2024, Norfolk Southern reported more than $1.1 billion in costs tied to the incident—$836 million in environmental expenses and $381 million for community assistance and legal fees. The railroad removed more than 177,000 tons of contaminated soil and 69 million gallons of wastewater. The EPA collected over 115 million air monitoring data points and took more than 45,000 air, water, and soil samples.

In April 2024, Norfolk Southern reached a $600 million class-action settlement with residents and businesses within a twenty-mile radius. Roughly 55,000 claims were filed, with 370 households and 47 businesses opting out. Households within two miles were eligible for about $70,000, with amounts tapering down to $250 for those fifteen to twenty miles away. Of the $600 million, $265 million was designated for direct property damage payments, $120 million for personal injury claims, $25 million for business losses, with the remainder going to legal fees and expenses.

In May 2024, the U.S. Department of Justice and EPA announced a separate $310 million settlement. It included $235 million for cleanup costs, a $15 million civil penalty, $25 million for a twenty-year community health program, and $15 million for private drinking water monitoring. In January 2025, the Village of East Palestine reached its own $22 million settlement with Norfolk Southern.

But the derailment also became a proxy war over the modern railroad model. The public debate quickly widened beyond East Palestine itself: braking technology and regulation, the effects of Precision Scheduled Railroading on staffing and maintenance, reduced crew sizes, and longer trains.

Out of that came the Railway Safety Act, introduced with bipartisan support and backed by figures including then-Senator JD Vance. It proposed, among other measures, wayside defect detectors every ten miles for hazmat trains, a phaseout of DOT-111 tank cars by May 2027, higher fines for safety violations, and a two-person crew minimum. As of early 2026, the bill remained stalled in Congress despite broad support. On the derailment’s third anniversary—February 3, 2026—lawmakers again called for its passage, noting that more than 3,100 derailments had occurred nationwide since East Palestine, but the legislation still had not advanced beyond the subcommittee level.

Inside Norfolk Southern, the crisis didn’t just trigger reforms. It detonated leadership.

CEO Alan Shaw, who had taken the top job in May 2022, was terminated in September 2024 after an internal investigation found he had an inappropriate relationship with the company’s chief legal officer, Nabanita Nag. The board elevated CFO Mark George to the presidency.

The boardroom pressure had already been building. Earlier in 2024, activist investor Ancora Holdings—managing roughly $10 billion, with a 0.15 percent stake in Norfolk Southern—launched a campaign targeting Shaw and calling for an operational overhaul. Ancora nominated seven board candidates, won endorsements from ISS, Glass Lewis, and Egan-Jones, and in May 2024 secured three board seats: Gil Lamphere, Sameh Fahmy, and William Clyburn Jr., a former Surface Transportation Board vice chairman. Longtime board chair Amy Miles was voted out. Shaw’s termination four months later completed the leadership reset that the activist campaign had helped set in motion.

Under George, and with new COO John Orr, the company said it was pivoting to a safety-first culture. Orr is a fourth-generation railroader whose family has more than 400 combined years of railroading service, largely at Canadian National in northern Ontario. He began in 1985 as a brakeman and conductor at CN, served as a local chairman for the United Transportation Union, rose to become CN’s Senior Vice President and Chief Transportation Officer, then later led operations at Kansas City Southern and served as Chief Transformation Officer at CPKC. Norfolk Southern paid CPKC a $25 million transfer fee to release Orr from his non-competition agreement. Railway Age later named him its 2026 Railroader of the Year.

A broader rebuild followed. Jason Zampi joined as CFO, Jason Morris as Chief Legal Officer, and Anil Bhatt as Chief Information Officer, all in the second half of 2024. Norfolk Southern also rebranded its operating philosophy as “TOP|SPG,” for Service, Productivity, and Growth.

By 2025, the company reported its best safety results in more than a decade: a 31 percent reduction in the FRA-reportable train accident rate, a 15 percent reduction in injuries, and zero reportable mainline derailments in the fourth quarter. Site restoration activities in East Palestine were completed in September 2025, with routine monitoring continuing. Norfolk Southern said in January 2026 that it had fulfilled every NTSB safety recommendation from the East Palestine final report.

Even the settlement process, though, became its own slow-moving aftershock. Five residents’ appeals delayed proceedings. The Sixth Circuit dismissed them, but the earliest effective date for direct payments became February 3, 2026—the third anniversary. Initial personal injury claim checks were mailed in late December 2025. Remaining personal injury payments were expected by March 2026, while direct property damage payments were not anticipated until May or June 2026.

And that leaves the question that hangs over every post-crisis turnaround: were these changes structural, or just the inevitable burst of vigilance that follows catastrophe—until attention fades and the railroad, slowly, reverts to the mean?

IX. Playbook: Business & Operating Lessons

The Norfolk Southern story reads like a history of modern American industry in miniature: consolidation, scale economics, and a constant tug-of-war between efficiency and the responsibilities that come with being essential infrastructure.

First, the consolidation playbook. Merging railroads is one of the hardest integration problems in business. You’re not just combining balance sheets or product lines. You’re stitching together operating rules, dispatching habits, labor agreements, equipment standards, yard layouts, customer expectations, and long-standing relationships with the towns along the right-of-way. Norfolk Southern’s 1982 merger took sixteen years to fully unify on paper, and even then, the deeper cultural divide between Norfolk and Western’s coal-and-engineering heritage and Southern’s diversified, modernizer mindset didn’t disappear overnight.

Then, in 1999, Conrail added a third lineage to blend in—at the exact moment Norfolk Southern was trying to prove it could run as one coherent system.

The takeaway is uncomfortable but clear: successful railroad mergers demand patience measured in decades, not quarters. The companies that try to jam cultures and systems together on an accelerated timeline—Penn Central is the cautionary tale—can break the very network they’re trying to “optimize.” That lesson hangs over any future megamerger, including the proposed Union Pacific–Norfolk Southern combination.

Second, network effects and density economics. Railroads are one of the purest businesses on earth for “the map is the moat.” The more connected your network is, the more valuable it becomes, because you can offer single-line service from origin to destination. That means one railroad owns the customer relationship, captures the full revenue, and avoids the delays, finger-pointing, and complexity of interchanges.

Norfolk Southern’s 58 percent stake in Conrail was expensive and operationally painful, but it also removed major interchange friction across the Northeast and opened up new single-line lanes that ultimately improved the economics of the whole system. And because railroads have huge fixed costs, the payoff from scale is brutal in a good way: once the track, terminals, and crews are in place, incremental volume can be highly profitable. That’s why mature railroads can generate operating margins that would look impressive in almost any industry.

Third, the true cost of deferred maintenance and safety shortcuts. Precision Scheduled Railroading produced undeniable near-term financial improvements across North American rail. But East Palestine showed what happens when a system gets tuned too tightly, with too little slack.

Detector spacing. Protocols that treated a non-critical alert as “no action required.” The continued presence of older DOT-111 tank cars with a long record of poor crashworthiness. High-stakes hazmat decision-making under time pressure. None of these issues, by themselves, explain the derailment. Together, they paint the portrait of a railroad—and an industry—where efficiency had been pushed ahead of resilience.

And the bill was enormous. Norfolk Southern disclosed more than $1.1 billion in costs by early 2024, with additional settlements afterward. Whatever PSR saved in the years leading up to the accident, East Palestine made painfully clear how fast one incident can erase those gains. The longer-lasting cost is trust, which can’t be refinanced or bought back.

Any asset-intensive business—railroads, pipelines, chemical plants, airlines—lives under the same rule: you can’t spreadsheet your way out of physics. If you squeeze maintenance and safety margins, eventually reality collects the debt.

Fourth, crisis management. Norfolk Southern’s response to East Palestine was criticized in real time, and the NTSB’s final findings suggested that criticism was earned. Not sharing OxyVinyls’ expert assessment with the incident commander. Proceeding with the vent and burn despite dissenting evidence. And, according to NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy, an adversarial posture toward investigators. Those weren’t simply tactical missteps. They came across as failures of judgment and, worse, failures of values.

The comparison to Johnson & Johnson’s handling of the Tylenol crisis in 1982 has come up for a reason: the first days of a crisis set the story that everyone retells later. Companies can spend years and billions trying to change the narrative, but they can’t rewrite the opening scene.

Finally, the hardest lesson: balancing shareholder returns with public responsibility. In the years before East Palestine, Norfolk Southern and its peers returned billions to shareholders through dividends and buybacks, while critics argued that safety investments and maintenance weren’t keeping pace.

That tension exists in plenty of industries. But it’s sharper in railroading because railroads are common carriers moving hazardous materials through thousands of communities. The people living along those tracks never opted in. They don’t get a vote on detector placement, staffing levels, train length, or operating protocols. Yet when something goes wrong, they’re the ones breathing the smoke, watching values drop, and wondering what’s in their soil and water.

If Norfolk Southern’s story has a single business lesson that transcends rail, it’s this: when you operate critical infrastructure, “externalities” aren’t theoretical. Eventually, they get a name, a place, and a date on the calendar.

X. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

Norfolk Southern’s investment story sits at a rare inflection point. On one hand, it owns infrastructure that can’t realistically be rebuilt or replaced. On the other, it’s still living with the consequences of East Palestine—the kind of event that changes how regulators, customers, and the public look at you for years. Layer on top a proposed $85 billion merger with Union Pacific, and you get a company with unusually high strategic optionality… and unusually high uncertainty.

The bull case starts with the map. Norfolk Southern’s 19,420 route miles across 22 eastern states, anchored by major hubs in places like Harrisburg, Chicago, and Atlanta, are as close to irreplaceable as an asset gets in modern America. Nobody is laying new mainline rail today. Between permitting, land acquisition, environmental reviews, and the simple reality of community opposition, the barriers aren’t just high—they’re functionally prohibitive.

That’s the heart of Norfolk Southern’s moat: a non-replicable network in the country’s densest population and manufacturing corridor. Competitors can price aggressively, invest in terminals, or improve service. But they can’t conjure a parallel Eastern railroad out of thin air.

Rail’s economics reinforce that advantage. A train can move a ton of freight about 480 miles on a gallon of fuel, making rail multiple times more fuel-efficient than trucking. Norfolk Southern says shipping by rail helps customers avoid roughly 15 million tons of carbon emissions each year. As sustainability pressure grows, highways stay congested, and the truck driver shortage persists—estimated by the American Trucking Association at around 80,000 drivers in recent years—rail becomes more attractive on the lanes where it can compete on service.

There’s also a turnaround argument. Under Mark George and COO John Orr, Norfolk Southern’s 2025 results showed improving performance across the operating dashboard: adjusted EPS of $12.49, productivity savings of $216 million (ahead of the company’s $150 million target), and free cash flow of $2.2 billion—the highest since 2021. The adjusted operating ratio improved to 65.0 percent.

Operationally, the railroad reported meaningful gains in 2025: system speed improved 10 percent, merchandise train velocity rose 11 percent, unit train speed jumped 17 percent, and unscheduled stops fell 31 percent. The company also set an annual fuel efficiency record. For a business where small improvements compound across a huge fixed-cost base, those kinds of changes matter.

Norfolk Southern points to growth opportunities beyond pure efficiency, too. In 2025, it reported more than 60 industrial development projects representing $7.7 billion in investment, with more than 500 more in the pipeline. It also cited 30 percent growth in transformer shipments, tied to AI and data center power demand. Reshoring and infrastructure spending could add real momentum to merchandise volumes, and the auto franchise delivered a record year in 2025.

Finally, there’s the less visible moat: institutional know-how. Running hundreds of trains a day over a vast network—safely, reliably, and profitably—isn’t something a new entrant can learn quickly. And for major shippers, switching railroads isn’t like switching vendors. Plants, warehouses, and distribution networks are built around specific rail access. Changing that means years of planning and enormous capital spend.

But the bear case is just as real—and arguably more immediate.

Start with the long, slow headwind: coal. The decline is not a surprise, but it’s still a drag. Export metallurgical coal pricing remained weak, with revenue per unit down 12 percent in Q4 2025. Coal was already just 14 percent of operating revenue in 2022, and it continued shrinking. That forces Norfolk Southern into a perpetual replacement game: intermodal and merchandise have to grow just to keep total revenue from sliding. It’s a treadmill the company has been running for years.

Then there’s competition—especially where Norfolk Southern most needs growth. Intermodal, the company’s modern lifeline, is getting more contested. In summer 2025, CSX and BNSF launched an intermodal alliance aimed straight at Norfolk Southern’s Eastern container franchise. Norfolk Southern said the intensified competition contributed to a 7 percent decline in intermodal volumes in Q4 2025 and a 6 percent revenue decline. The alliance offers coast-to-coast intermodal service connecting Southern California and Phoenix to markets like Charlotte, Jacksonville, and Atlanta, using BNSF haulage rights over CSX. Norfolk Southern estimated the impact as roughly a 1 percent headwind to total revenue—but in a mature, high fixed-cost industry, a “one percent” problem can still bite.

Trucking remains another constant pressure, particularly on shorter-haul moves where rail’s fuel advantage is less decisive and service expectations are tighter. And large customers—major retailers and consumer goods shippers—have real negotiating leverage. They can play carriers against each other, and they do.

More broadly, rail continues to fight for relevance against the highway system. Rail freight’s share has fallen from 51 percent to 37 percent over the last decade, while trucking rose from 49 percent to 63 percent. That’s one reason the proposed UP–NS merger is framed as a strategic response: a transcontinental network that could win freight back.

East Palestine is the other overhang. While major settlements have been announced, the settlement process has moved slowly, and the class-action payment timeline has been delayed—direct payments weren’t expected until mid-2026 after complications with the original payment administrator. Regulatory scrutiny remains elevated, and if the Railway Safety Act eventually becomes law, it could impose meaningful new compliance costs. Even when the legal bills stop rising, reputational damage can linger in ways that are harder to quantify: community opposition, political hostility, and customers who don’t want to be caught in the blast radius of another headline.

Then there’s the Union Pacific proposal, announced in July 2025, which brings both upside and risk. Union Pacific proposed a deal valued at an $85 billion enterprise value, at $320 per share, a premium to roughly $290 as of early February 2026. The combined company would span more than 50,000 route miles, with combined revenues of $36 billion and projected annual synergies of $2.75 billion.

But the regulatory road looks brutal. In January 2026, the Surface Transportation Board unanimously rejected the initial application as incomplete, pointing to missing market share projections, incomplete merger agreement schedules, and a misclassified subsidiary acquisition. Rival Class I railroads and major shipper groups have objected. And the STB’s 2001 merger rules—requiring that major mergers enhance competition—have never been tested in a case like this.

If the deal fails, Norfolk Southern would receive a $2.5 billion reverse termination fee. But it would still face an awkward question: did the merger attempt itself weaken the business by creating uncertainty for customers and inviting competitors to reposition aggressively?

One point in Norfolk Southern’s favor is safety momentum. While derailments rose across the top five freight railroads in 2023 amid heightened scrutiny, Norfolk Southern was the only one to report a decline in accidents—suggesting its post-East Palestine response may have been more substantive than the industry average.

For investors, the signals to watch are straightforward. The adjusted operating ratio remains the central efficiency yardstick, and Norfolk Southern has said it aims to push toward the low 60s. Intermodal volume growth is the clearest read on whether the railroad can replace declining coal with higher-growth container traffic. And the FRA-reportable train accident rate is the leading indicator that matters most: whether the company’s safety push is becoming durable culture, or fading into the background as the crisis moves further into the rearview mirror.

XI. Epilogue & Future Outlook

Union Pacific’s proposed acquisition of Norfolk Southern is the biggest railroad consolidation attempt in decades. If it goes through, it would create the first true transcontinental U.S. freight railroad: one network stretching across more than 50,000 route miles, touching 43 states, and linking around 100 ports. In a business where the map is the moat, this would redraw the map.

On paper, the numbers are meant to speak for themselves. The companies have projected roughly $36 billion in combined revenue, about $18 billion in EBITDA, and $2.75 billion in annual synergies. In November 2025, more than 99 percent of shareholders at both companies voted in favor. Union Pacific CEO Jim Vena committed to lead the combined entity for at least five years, while Norfolk Southern CEO Mark George and director Richard Anderson were expected to join the Union Pacific board.

But the deal doesn’t live or die on a shareholder vote. It lives or dies in Washington.

In January 2026, the Surface Transportation Board rejected the initial application as incomplete. The decision wasn’t necessarily fatal— it was issued without prejudice, meaning the companies could refile—but it was still a clear warning shot. The STB told Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern to respond by February 17, 2026, with their plans for a revised filing. On Norfolk Southern’s Q4 2025 earnings call, George framed the setback as procedural: “They’ve given us the path to completeness. We know exactly what they want, and we’re working on it.” The companies were expected to refile in March 2026, targeting a close in early 2027. The merger agreement ran through January 2028, with automatic extensions.

And the resistance is organized and loud. Rival Class I railroads—CPKC, Canadian National, CSX, and BNSF—have lined up against the deal, along with the National Grain and Feed Association and major unions. Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern argue that a coast-to-coast railroad could reverse rail freight’s long-term market share decline against trucking by removing handoffs and friction across regions. Opponents counter that cutting the number of Class I railroads from seven to six reduces competitive pressure in markets where shippers may already have only two meaningful options.

That argument runs straight into the STB’s merger rules from 2001, which don’t just ask mergers to avoid harming competition—they require major mergers to enhance it. Those rules were written in the aftermath of the last consolidation wave, and they were deliberately designed to make another mega-merger extremely hard to justify.

Whatever the STB decides will echo far beyond these two companies. It will set precedent for what “enhance competition” actually means in modern railroading—and whether the door to another era of consolidation is truly closed.

Meanwhile, the market isn’t waiting. Competitive response has already started. CSX has partnered with both BNSF and CPKC on interline services designed to offer coast-to-coast and U.S.-to-Mexico alternatives. If the Union Pacific–Norfolk Southern merger fails, those alliances may harden into permanent features of the landscape, reshaping intermodal competition and potentially weakening Norfolk Southern’s container franchise regardless of what regulators do.

Still, merger or no merger, Norfolk Southern is in the middle of a forced reinvention. And this time, it’s not just a matter of shifting from coal to intermodal. It’s about proving—to regulators, communities, shippers, and its own employees—that safety and service are no longer negotiable.

On the technology front, the company has been investing aggressively. Ten Digital Train Inspection Portals now scan more than 75 percent of all traffic monthly using AI-powered defect detection, supported by more than 75 algorithms designed to identify mechanical problems before they turn into incidents. Norfolk Southern has deployed more than 1,184 hot bearing detectors across the network, adding 265 over the past three years and shrinking average spacing to a little over eleven miles on core routes.

It’s also rolling out systems meant to catch failures earlier and respond faster when things go wrong. A new Wheel Integrity System in Burns Harbor, Indiana identified a critical external vendor casting flaw that led to an industry-wide recall. Norfolk Southern also became the first railroad to partner with RapidSOS, giving more than 16,000 emergency response agencies real-time access to train consist information. Taken together, these moves aren’t just PR. They’re a shift toward predictive maintenance and faster, clearer emergency coordination.

But the harder work is cultural. Under COO John Orr, Norfolk Southern has talked about a “PSR 2.0” approach: holding onto the efficiency gains of Precision Scheduled Railroading while restoring the slack, maintenance margin, and service quality that critics argue were squeezed out in the first wave. A zero-based operating plan introduced in early 2025 streamlined train plans and resource allocation, cutting more than 100 weekly crew starts and reducing final-mile dwell for more than 600 customers. The company also ran 24/7 “war rooms” focused on velocity and mechanical performance, expanded partnerships with over 40 short-line railroads, and improved locomotive productivity—measured in gross ton-miles per available horsepower—from 94 in mid-2023 to over 130 in 2025.

And the pressure isn’t going away. ESG scrutiny will only intensify, especially after East Palestine. Norfolk Southern said it spent more than $244 million on safety initiatives through 2025 as part of its Six-Point Safety Plan, trained more than 5,800 first responders in 2025, and broke ground on a $25 million first responder training center in East Palestine. Whether those actions can fully rebuild public trust is still an open question. Trust doesn’t rebound on a quarterly cadence.

For anyone following the story—investors, regulators, shippers, communities—the next year is pivotal. The STB’s response to a revised merger application, expected by mid-2026, will shape whether Norfolk Southern’s future is as part of a transcontinental giant or as an independent Eastern carrier facing sharper competition than ever. Either way, the railroad has to show that it truly learned from its worst chapter.

Norfolk Southern is, at once, a cautionary tale and a case study in resilience. Nearly two centuries of inherited history—from the Best Friend of Charleston to the plume over East Palestine—show an industry that repeatedly survives by reinventing itself. A railroad that once defined itself by Appalachian coal now runs on the flow of global trade in steel boxes. A company whose reputation cracked on a February night in Ohio later posted its best safety metrics in more than a decade.

Merger or no merger, that’s the enduring reality: Norfolk Southern’s rails are part of the hidden backbone of the American economy. What happens next—how the company invests, how it operates, how it responds when things go wrong—will matter long after the deal headlines, the hearings, and the news trucks move on.

XII. Recent News

Union Pacific’s proposed acquisition of Norfolk Southern—an $85 billion deal on the headline—remained the near-term story in early 2026. After the Surface Transportation Board rejected the companies’ initial, roughly 7,000-page filing as incomplete on January 16, 2026, regulators told them to come back by February 17 with a plan: would they refile, and if so, when? The expectation was a revised application in March 2026. On Wall Street, the spread told you what investors thought of the odds. Norfolk Southern stock traded around $290 in early February 2026—about ten percent below the proposed $320-per-share price—signaling real uncertainty around approval, timing, or even whether the terms would ultimately hold.

Operationally, Norfolk Southern’s latest results were stronger than the market drama might suggest. In its Q4 2025 report on January 29, 2026, the company posted adjusted earnings per share of $3.22, well ahead of the consensus estimate of $2.77. For the full year, adjusted EPS reached $12.49, up five percent year over year, on railway operating revenue of $12.2 billion. Free cash flow came in at $2.2 billion, roughly $500 million higher than the prior year. The company also declared a $1.35 quarterly dividend, or $5.40 annualized.

But the metric Norfolk Southern wanted everyone to focus on wasn’t earnings. It was safety. The railroad reported zero reportable mainline derailments in the fourth quarter and said its mainline accident rate improved 71 percent versus the prior year. In its 2025 Safety Report, released January 27, 2026, Norfolk Southern said FRA-reportable train accidents fell 31 percent and injuries fell 15 percent. The company also said it had fulfilled every NTSB safety recommendation from the East Palestine final report, which the NTSB confirmed in a January 2026 letter.

The investment push behind those claims was increasingly visible. Norfolk Southern said it had deployed 1,184 hot bearing detectors and 10 Digital Train Inspection Portals, with plans to expand to 20 portals that would cover about 90 percent of the network.