NVIDIA: From Denny's to Dominance - The GPU Revolution

I. Introduction & The Stakes

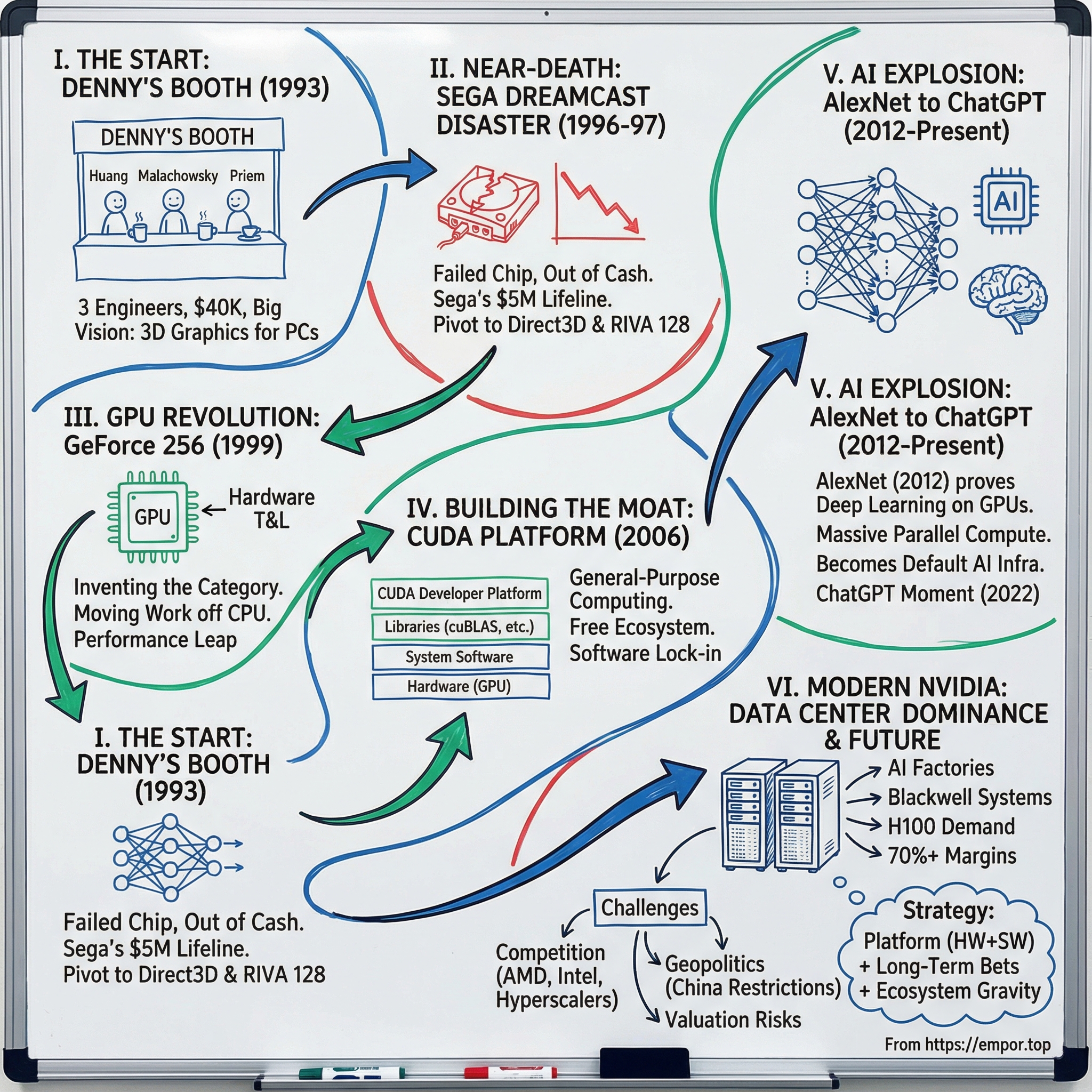

Picture this: it’s January 2025. CES in Las Vegas. Jensen Huang steps onto the stage in his now-iconic black leather jacket. Behind him, giant screens flash NVIDIA’s next big thing: Blackwell. In the room are the leaders of the modern tech economy—CEOs and executives from the companies that increasingly run on NVIDIA hardware.

And it’s hard not to pause on the contrast. The guy who once had just a couple hundred bucks in his pocket to start a graphics chip company is now at the helm of a business worth trillions. His personal fortune sits around $150 billion, putting him in the rarest class of global wealth.

But the wealth isn’t the point. The point is what happened in between.

Because the real story starts much smaller: three engineers in a vinyl booth at a Denny’s in East San Jose, sketching out an idea that would end up reshaping computing.

Today, NVIDIA isn’t just another semiconductor company. It has become the semiconductor company—one of the most profitable, strategically central businesses in the entire tech stack. When Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta want to train frontier AI models, they line up to buy NVIDIA. When scientists push the boundaries in drug discovery or climate modeling, NVIDIA is the workhorse. When autonomous systems learn to interpret the world, NVIDIA is often doing the seeing.

So here’s the question this story answers: how did a company that nearly died more than once—dismissed for years as a video game graphics vendor, underestimated by incumbents like Intel and AMD—end up as essential infrastructure for the biggest platform shift since the internet?

This is a story about surviving crises that should’ve killed the company. About placing a bet that wouldn’t fully pay off for years. And about building not just chips, but an ecosystem—hardware, software, and developers—that competitors still struggle to pry apart.

From a Denny’s booth in 1993 to AI dominance by 2026, this is the NVIDIA story.

II. The Denny's Origin Story & The Three Founders

The Denny’s on Berryessa Road in East San Jose wasn’t anyone’s idea of a glamorous headquarters. Fluorescent lights buzzed over Formica tables. Coffee and hash browns hung in the air. Servers topped off mugs on autopilot. It was anonymous, forgettable—and perfect.

Because that’s exactly what Jensen Huang, Chris Malachowsky, and Curtis Priem needed: a place where three engineers could sit for hours, argue, sketch, and dream out loud without anyone paying attention. Throughout 1992 and into early 1993, they kept coming back, filling napkins with diagrams and “what if” scenarios for a company that didn’t exist yet.

Huang was thirty, a product manager at LSI Logic with time at AMD behind him. Born in Taiwan and raised in the U.S., he’d studied electrical engineering at Oregon State and picked up an MBA at Stanford. Of the three, he was the one who could translate engineering into a business—how to pick a market, raise money, ship product, and survive long enough to matter.

Malachowsky brought heavyweight technical credibility. At Sun Microsystems, he’d worked on graphics systems for high-end workstations—the kind of machines professionals used for serious visualization. He’d watched graphical interfaces take over computing and kept coming back to the same question: if graphics mattered this much, why was so much of it still being shoved through general-purpose CPUs?

Priem was the wild card: brilliant, unconventional, and stubborn in the best way. Also from Sun, he had a reputation for making the impossible work, not by brute force, but by seeing a different path. Business plans didn’t excite him. Elegant solutions did.

Their division of labor snapped into place early. Priem later described it bluntly: he and Malachowsky essentially told Huang, “You’re in charge of running the company—all the stuff Chris and I don’t know how to do.” It was an unusual setup—putting the product guy in charge while the two deep engineers anchored the technology. But Huang’s mix of technical fluency and operating instinct made him the natural CEO.

So what did they want to build?

In 1993, their ambition sounded almost modest: specialized chips for 3D graphics on personal computers and in video games. Gaming was growing fast, PCs were getting more visual, and graphics on the mainstream machine was still… bad. CPUs could do it, but inefficiently. Dedicated graphics existed, but it was either expensive workstation gear or limited consumer hardware. The gap was obvious.

Their thesis was simple and aggressive: 3D graphics was going to become a baseline expectation on PCs, games would be the wedge that forced it into the mainstream, and whoever could deliver great performance at consumer prices would own a huge market.

Even the name was part of that swagger. They started with “NVision,” but it was too generic, too easy to blend into the background. Then Priem reached for a Latin word: invidia—envy. He liked the idea that competitors would turn “green with envy” watching what they built. NVIDIA stuck.

But vision doesn’t pay for silicon.

When they incorporated, Huang reportedly had about two hundred dollars to his name. Together, the founders scraped up roughly forty thousand dollars—enough to form the company and start work, nowhere near enough to design and manufacture chips in the real world.

That meant venture capital. And in 1993, there was no more consequential stamp of approval than Sequoia Capital. They found their champion in Don Valentine—the legendary investor behind Apple, Cisco, and Oracle. Valentine’s style was famously direct, and the lore matches the moment: he told his partners, in effect, “Give this kid money and figure out if it’s going to work.”

Sequoia led a twenty-million-dollar round that gave NVIDIA its first real shot. For a graphics chip startup, that wasn’t just helpful—it was oxygen. It meant hiring, tools, chip fabrication, and the chance to run at the problem instead of crawling.

Why did Sequoia believe? Games were one reason. But the bigger one was staring everyone in the face: Windows was becoming truly graphical. Microsoft was pulling computing into an interface built on pixels, not text. Intel’s CPUs weren’t designed to make that smooth and beautiful. Someone else would have to supply that horsepower. Valentine was betting Huang’s team could be that someone.

NVIDIA’s early days quickly moved from diner napkins to a small office and an even smaller margin for error. The work was relentless: long nights, constant debate, and the steady pressure of a startup burning investor money with nothing to show yet but ambition. Huang set the tone—intensity, precision, and a conviction that graphics wasn’t a feature. It was the future.

In hindsight, the Denny’s booth feels like Silicon Valley mythology: humble beginnings, big vision, a name with attitude. But in 1993, NVIDIA was just another chip startup in a valley full of them—one that could easily have shipped nothing, run out of cash, and disappeared.

The difference was what came next: a near-death experience that should have ended the company, but instead hardened it into something built to survive.

III. Near-Death Experience: The Sega Dreamcast Disaster

Three years into NVIDIA’s existence, the company was dying.

It was 1996, and the early promise of the Denny’s booth wasn’t translating into a business. NVIDIA had shipped its first chips—the NV1 and a follow-on—but they didn’t land. The design was clever in ways engineers could admire and customers could ignore. Game developers didn’t want to build around it, the market was standardizing elsewhere, and NVIDIA was running out of cash.

Then came Sega.

Sega was building its next console, the Dreamcast—its shot at taking on Sony’s PlayStation in the living room. They needed a graphics partner. NVIDIA needed a lifeline. The arrangement looked like salvation: NVIDIA would build the graphics processor, Sega would fund development, and if the console took off, NVIDIA would finally get the scale and credibility that no PC design win could match.

For a brief moment, it worked—at least on paper. The partnership was announced with real excitement. NVIDIA suddenly had a marquee customer. The engineers threw themselves into the project with the kind of intensity you only get when failure means the company doesn’t exist.

And then NVIDIA delivered a chip that wasn’t good enough.

Sega’s requirements were brutal. The Dreamcast had to feel like the future, and it had to do it on a console bill of materials. NVIDIA’s design struggled to hit the specs. The team was still learning what it meant to ship a production-quality semiconductor under a hard deadline, and what came out the other end was later described, even inside NVIDIA, as a “technically poor” chip.

Sega’s engineers weren’t just disappointed—they were angry. The schedule slipped. Performance wasn’t there. After months of trying to salvage the effort, Sega pulled the plug and switched directions, eventually going with NEC’s PowerVR technology instead.

For NVIDIA, it wasn’t a lost contract. It was a trapdoor.

They’d bet what they had left on the Sega deal. The development work had eaten the remaining runway. Now the customer was gone, the product wasn’t shippable, and the bank account was empty. Jensen Huang faced the kind of decision that ends most startups: shut it down, return whatever crumbs were left, and call it.

Instead, Sega did something almost absurdly generous. Rather than walking away clean, Sega invested five million dollars directly into NVIDIA. Part goodwill, part self-interest—Sega had already spent time and money on the relationship, and they still believed the underlying team and technology could turn into something. For NVIDIA, it was oxygen. Not comfort. Just enough to keep breathing.

In one of those strange footnotes that only make sense in hindsight, Sega eventually made roughly ten million dollars in profit on that investment as NVIDIA’s value later soared.

But surviving on a check wasn’t enough. Huang had to make the other move: cut to the bone. More than half the company was let go. People who’d worked nights and weekends, who’d bought into the dream, were suddenly out. The team that remained was smaller, shaken, and intensely aware that the next swing had to connect.

And that’s where NVIDIA finally did the thing it should’ve done earlier: align with where the ecosystem was going, not where they wished it would go.

Instead of building architectures that forced developers to make special accommodations, NVIDIA committed to working with Microsoft’s Direct3D—the standardizing API for PC gaming. It meant abandoning some proprietary ideas. It also meant instant compatibility with the direction Windows gaming was moving. Developers could target one interface, and NVIDIA could win by being fast, reliable, and available.

The product that came out of that decision was the RIVA 128 in 1997. It was, in all the ways that mattered, the opposite of the Dreamcast chip: it worked with existing software, it was priced to compete, and it delivered real performance that gamers could feel.

It sold more than a million units. For a company that had been staring at the end less than two years earlier, it wasn’t just a hit. It was a resurrection.

That period branded NVIDIA’s DNA. Survive first. Standards matter. And crisis has a way of stripping away delusion and forcing focus. The post-Dreamcast NVIDIA was sharper, more disciplined, and far less sentimental about what to cut and what to bet on.

Huang would return to this moment again and again in later years—not as a tragedy, but as the crucible. The company that walked into the Sega partnership was still a talented startup searching for a market. The company that walked out had scar tissue—and a playbook for turning disaster into momentum.

And that momentum was about to be aimed at something bigger than a single product win. NVIDIA was about to invent a category—and then convince the world it needed it.

IV. The GPU Revolution: GeForce 256 & Inventing a Category

On August 31, 1999, NVIDIA pulled off a move that was equal parts engineering and theater. They announced a new graphics card called the GeForce 256. But they didn’t just launch a product—they launched an idea.

“The world’s first GPU,” the press release said. Graphics Processing Unit.

That phrase didn’t exist in the market vocabulary before NVIDIA put it there. And once it was out, it changed the conversation. NVIDIA wasn’t selling “a faster graphics card.” They were telling everyone—gamers, developers, press, investors—this was a new kind of processor. A new center of gravity inside the PC.

Here’s why that claim wasn’t just hype.

Before GeForce 256, most of the real work of 3D graphics still landed on the CPU. Every time a game needed to render a scene, the CPU was the one doing the hard math: taking 3D objects, transforming them into the right perspective for the camera, and figuring out how light should hit surfaces. Only after the CPU finished all that would the graphics card step in to do what people thought graphics cards did: paint pixels.

It was an awkward split. CPUs are built to do a little bit of everything, which is great for general computing and terrible for repetitive, highly parallel graphics math. Meanwhile, the graphics chip—built for exactly that kind of workload—was stuck waiting around for the CPU to catch up.

GeForce 256 flipped the model by adding hardware transform and lighting, or T&L. In plain terms: the GPU started doing the 3D math itself. Transforming geometry. Calculating lighting. Taking a major chunk of the workload off the CPU and doing it where it belonged.

Yes, the specs were big for 1999—about seventeen million transistors, a 139 square millimeter die, a 120 megahertz clock, and support for Microsoft’s DirectX 7.0 standard. But what mattered wasn’t the spec sheet. It was the feeling.

Reviewers dropped the GeForce 256 into real systems and saw something that made the upgrade instantly obvious: on machines with modest, affordable CPUs—the PCs most gamers actually owned—frame rates could jump dramatically, in some cases up to fifty percent. NVIDIA wasn’t just making high-end rigs faster. They were making mainstream computers feel like they’d leapt a generation.

That’s what “GPU” really meant. Not a brand. A shift in who did the work.

When the card hit retail on October 11, 1999, NVIDIA had effectively raised the bar for the entire industry. ATI responded with Radeon and turned the space into a long-running two-player war. But 3dfx—the late-’90s king with its Voodoo cards—didn’t make the transition. It fell behind, then unraveled.

On December 15, 2000, NVIDIA acquired 3dfx’s intellectual property and key patents. The company that had once defined PC gaming graphics became, in a sense, an asset on NVIDIA’s balance sheet. The first era of the graphics wars had a clear winner.

And the GeForce 256’s impact didn’t stop at games.

What NVIDIA proved in 1999 was a broader principle: if you take a workload that’s fundamentally parallel and move it off a general-purpose CPU onto a specialized processor designed for that exact kind of math, you can change the economics of performance. Suddenly, you don’t need a bigger CPU to get a better experience—you need a different kind of chip.

That idea would come back, years later, in a completely different context. Researchers would realize that neural networks had something in common with 3D graphics: massive amounts of parallel computation. And the same architectural bet NVIDIA made for games would become the backbone of modern AI.

But back in 1999, NVIDIA didn’t need anyone to predict the future. They just needed the world to repeat one new word.

GPU.

And they made sure it stuck.

V. Building the CUDA Platform: The Software Moat

In 2004, NVIDIA hired a Stanford PhD student named Ian Buck. He arrived with an obsession that, at the time, sounded like a curiosity—and would later look like prophecy.

Buck had spent years chasing a strange question: could a graphics card do work that had nothing to do with graphics? In his doctoral research, he built Brook, a programming language that let researchers write code for GPUs even when they weren’t rendering images.

The concept was exciting. The reality was miserable.

GPUs in the early 2000s were built to draw triangles, shade pixels, and move textures. If you wanted to do something like scientific computing or financial modeling, you had to disguise your problem as a graphics problem—shove your data into textures, trick the chip into treating your math like shading, then pull results back out. Brook proved it was possible. It did not make it easy.

NVIDIA, though, saw what Buck was really pointing at. They paired him with John Nickolls, a seasoned computer architect who knew how to turn a research demo into something real. The assignment wasn’t subtle: take Brook’s core idea—general-purpose computing on a GPU—and make it usable by normal developers.

That meant building a software stack from scratch.

Graphics APIs of the day assumed the world was vertices and pixels. They weren’t designed for “here’s a big matrix, please multiply it fast,” or “here’s a simulation, run it in parallel.” If NVIDIA wanted the GPU to become a true computing engine, developers needed a way to write C-like code, compile it, run it, debug it, and trust it.

Over the next two years, the team didn’t just ship a language. They built an ecosystem: a compiler to turn code into GPU instructions, a runtime to manage execution, tools for debugging and profiling, and libraries that handled the common building blocks of high-performance computing.

In 2006, NVIDIA launched CUDA—Compute Unified Device Architecture—and called it “the world’s first solution for general-computing on GPUs.” But the most important part wasn’t the tagline. It was the decision that came with it: CUDA would be free.

That wasn’t generosity. It was a moat, poured in wet concrete.

Huang understood what many hardware companies learn too late: performance wins deals, but ecosystems win decades. Intel’s grip on computing wasn’t just about faster chips; it was about the mountain of software written for x86. Switching architectures wasn’t just buying a different processor—it was rewriting the world.

CUDA was NVIDIA’s version of that lock-in. Every lab that adopted it, every developer who learned it, every project built on its libraries raised the cost of choosing anything else later.

And NVIDIA fed that loop. They shipped optimized libraries—cuBLAS for linear algebra, cuFFT for Fourier transforms, and later cuDNN for deep neural networks. Each one saved developers weeks or months. Each one worked best—and often only—on NVIDIA hardware.

Adoption followed a familiar academic pattern. Universities picked CUDA because it was free and well-documented. Researchers published papers showing dramatic speedups over CPU code. Graduate students learned CUDA because that’s what got results. Then they graduated and carried CUDA into industry.

By around 2010, CUDA had become the default platform for GPU computing in scientific research. Alternatives existed. OpenCL offered cross-platform compatibility, but it didn’t have NVIDIA’s depth of tooling, its optimized libraries, or its momentum. Many developers tried OpenCL, hit friction, and came back.

For years, this looked like a strange use of time and money. Gaming still paid the bills, and CUDA-related revenue barely registered. Analysts questioned why NVIDIA was investing so heavily in a niche that didn’t move the financials.

Huang kept giving the same answer: this was the long game. CUDA was a bet that GPU computing would matter far beyond games—and if that future arrived, NVIDIA wanted to be the default.

The punchline is that the payoff did arrive, but not in the form NVIDIA originally pitched. It wasn’t primarily financial modeling or physics simulations that made CUDA indispensable.

It was artificial intelligence—an area that barely touched GPUs when CUDA launched, and then became inseparable from them within a decade.

In hindsight, the years spent building CUDA weren’t a side project. They were NVIDIA quietly constructing its strongest defense: a software platform and developer habit that competitors could admire, but not easily copy.

VI. The AI Explosion: From AlexNet to ChatGPT

The moment that changed everything arrived in October 2012, in a nerdy academic contest most of the world had never heard of.

The ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge was a simple idea with brutal implications: give a system a photograph and ask it to name what’s in it. Dog. Car. Tree. Coffee mug. Since 2010, teams had been making steady, incremental progress—smart feature engineering, clever tweaks, a few points shaved off the error rate each year.

Then Alex Krizhevsky showed up and blew a hole in the curve.

Krizhevsky was a graduate student at the University of Toronto, working with Geoffrey Hinton—one of the stubborn pioneers who kept believing in neural networks through years when the rest of the field had moved on. Their approach wasn’t a better handcrafted system. It was a deep neural network: lots of layers, trained end-to-end on huge amounts of data.

And the thing that made it feasible wasn’t a new theory. It was compute.

Their secret weapon was NVIDIA GPUs running CUDA. Training a deep network is basically an industrial-scale loop: run images through the model, measure how wrong it is, adjust millions of weights, and repeat—over and over, across an enormous dataset. On CPUs, that kind of workload was painfully slow. Krizhevsky later showed that what would have taken months on conventional hardware could be done in roughly a week on two NVIDIA GTX 580 graphics cards.

When the results came in, they didn’t just win. They embarrassed the field.

Previous ImageNet winners had top-five error rates around the mid‑20s—meaning even with five guesses, they were wrong a lot. AlexNet posted 15.3 percent. It wasn’t an incremental improvement. It was a step-change big enough to force a new conclusion: deep learning worked, and GPUs made it practical.

The reaction was immediate. The computer vision community didn’t debate it for years. It pivoted. Almost overnight, the question shifted from “Should we use neural nets?” to “How do we scale them?” And the most straightforward answer was: buy NVIDIA.

That’s how an academic benchmark turned into an avalanche. Before AlexNet, GPU use in serious AI research was still relatively niche. After it, researchers everywhere were trying to get their hands on NVIDIA cards. By 2014, deep learning had become the dominant paradigm in machine learning research—and “GPU computing” effectively meant NVIDIA.

The technical reason was almost too perfect. Neural networks are built on the kind of math GPUs were born for: massive parallel matrix operations. CPUs are incredible at general-purpose tasks, but they’re optimized for a small number of powerful cores doing sequential work. GPUs, by contrast, bring thousands of smaller cores designed to do the same operation across huge chunks of data at once. For the matrix multiplications at the heart of training neural networks, that parallelism translated into order-of-magnitude speedups versus CPUs.

And here’s the kicker: NVIDIA had already built the on-ramp.

CUDA had been sitting there for years—compilers, drivers, debugging tools, libraries—waiting for a killer use case. When deep learning hit escape velocity, NVIDIA wasn’t scrambling to catch up. It was the only company that could hand researchers both the hardware they needed and the software stack that made it usable. The CUDA investment that looked hard to justify in the late 2000s started to look, by the mid‑2010s, like a lock the industry couldn’t easily pick.

Over the next decade, the demands only grew. Each new breakthrough wanted more data, bigger models, longer training runs. Language models scaled from millions of parameters to billions to hundreds of billions. Training GPT‑4, according to various estimates, required roughly 2.15 × 10²⁵ FLOPS of compute—an absurd figure that doesn’t land emotionally until you translate it into something tangible: around 25,000 NVIDIA A100 GPUs running for roughly three months. At then-current pricing, the hardware bill alone was on the order of $100 million.

Then came ChatGPT.

OpenAI launched it in November 2022. Within two months, it hit 100 million users—one of the fastest consumer adoption curves ever recorded. And behind that chat box, NVIDIA GPUs were doing the work: serving queries, running inference, turning “type a sentence” into “compute a response.”

Financially, this was the phase change. NVIDIA’s stock—around $130 split-adjusted in early 2022—climbed toward $800 by early 2024. The company’s market cap vaulted past $1 trillion and then $2 trillion. For a brief stretch in 2024, NVIDIA even wore the crown as the world’s most valuable company.

But the bigger story wasn’t the stock chart. It was the strategic question the chart forced everyone to ask: was this a durable position, or a once-in-a-generation spike the market was overpricing?

The bull case was simple: AI adoption was still early, enterprises were just beginning, and NVIDIA owned the picks-and-shovels layer with both hardware and software. The bear case was just as clear: competition would arrive, customers would resent the dependency, geopolitics would intrude, and expectations had started to assume perfection.

As of early 2026, the verdict still isn’t final. What is clear is how NVIDIA got here: two decades of compounding bets on accelerated computing—chips, systems, and CUDA—perfectly positioned for the moment AI stopped being a research topic and became the world’s next platform shift.

VII. The Modern NVIDIA: Data Center Dominance & Beyond

Walk into a major data center run by Microsoft, Google, Amazon, or Meta and you’ll see the same pattern repeating: row after row of racks built around NVIDIA. Status lights blinking. Fans roaring. Heat and electricity being converted into something oddly intangible—models, predictions, “intelligence”—one matrix multiply at a time.

The shift NVIDIA spent years setting up is now fully visible. It’s no longer primarily a gaming graphics company that happens to sell into servers. It’s an AI infrastructure supplier that still happens to sell to gamers. Data center revenue, which barely mattered a decade earlier, overtook gaming and became the engine of the business. By fiscal 2024, that segment alone brought in more than $47 billion—sudden scale that would’ve sounded absurd when CUDA launched as a free toolkit.

With that scale came dominance. NVIDIA held roughly 85 percent of the market for AI training chips, and the H100—built on the Hopper architecture—turned into the most coveted piece of silicon in tech. Lead times stretched for months. In the gray market, prices climbed past $40,000 per chip. Entire companies, like CoreWeave, grew by solving a single problem for customers: getting NVIDIA GPUs faster than NVIDIA could.

Then NVIDIA moved the goalposts again. Blackwell, announced in 2024 and shipping in volume through 2025, pushed performance and system design further. Huang started pitching customers on “AI factories”—purpose-built facilities that consume staggering amounts of power and produce trained models the way a traditional factory produces cars or chips. The metaphor wasn’t subtle. NVIDIA wanted AI to be understood not as a line item in an IT budget, but as capital equipment—industrial machinery for manufacturing a valuable output.

The financial profile reinforced that framing. NVIDIA’s data center gross margins ran above 70 percent, which is the kind of number people associate with software platforms, not physical hardware. And that’s the point: those margins aren’t just about silicon. They reflect CUDA and the surrounding stack. Customers aren’t buying a chip. They’re buying compatibility, tools, libraries, and a developer ecosystem that no one else has fully recreated.

Of course, dominance doesn’t go unanswered.

AMD’s MI300 line emerged as the most credible challenge NVIDIA had faced in years, with competitive specs and an ecosystem pitch through ROCm, AMD’s answer to CUDA. Microsoft and Meta publicly committed to deploying AMD accelerators, signaling they wanted leverage—and options.

Intel came at the problem with Gaudi accelerators, leaning on efficiency and the promise of fitting neatly into Intel’s broader data center footprint. It hadn’t broken through in a big way, but Intel’s scale and relationships ensured it stayed on the board.

The more existential pressure, though, came from NVIDIA’s best customers. Hyperscalers increasingly asked a dangerous question: why keep paying NVIDIA’s margins if you can design your own chips? Google’s TPUs already ran much of Google’s internal AI work and were expanding outward. Amazon pushed Trainium and Inferentia as cheaper paths for certain AWS workloads. Microsoft and Meta announced their own silicon efforts too.

NVIDIA’s counterargument was speed. Custom silicon is slow: define the workload, design the chip, tape it out, fabricate it, deploy it, build the software around it. By the time that machine gets rolling, NVIDIA is often onto the next generation—and the ecosystem is still CUDA-shaped.

Then there’s geopolitics. U.S. export restrictions limited NVIDIA’s ability to ship its most advanced chips to China, which had previously been a meaningful market. NVIDIA responded with compliant products that dialed back capabilities, but the broader reality remained: a huge pool of demand was now partially gated by policy, not technology.

And in early 2025, the DeepSeek episode highlighted both how much demand still existed—and how creative teams would get when blocked. The Chinese research lab announced models with competitive performance despite reportedly lacking access to the newest NVIDIA hardware. They squeezed more out of what they had by programming directly in PTX, NVIDIA’s intermediate representation layer, rather than relying on CUDA abstractions—effectively trading convenience for low-level control. Whether that was a durable path away from CUDA or simply an impressive workaround was debated, but the message landed: even NVIDIA’s strongest moat could be probed.

If you’re trying to understand NVIDIA from here, the scorecard gets surprisingly simple. Watch data center growth to see whether AI infrastructure spending keeps expanding. Watch gross margins to see whether competition and customer pushback are finally showing up in pricing. And watch customer concentration, because when a handful of hyperscalers are the biggest buyers, their decisions can swing the entire company. Growth, margins, and concentration—those three signals will shape whether NVIDIA’s dominance compounds for another decade, or starts to crack under its own success.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Strategy Lessons

NVIDIA’s rise from a Denny’s booth to the center of the AI economy isn’t just a hardware story. It’s a strategy story. A handful of choices—made early, reinforced under pressure, and compounded over decades—created the flywheel that competitors still can’t quite stop.

The Platform Approach: Hardware Plus Software

NVIDIA’s most important move was refusing to think of GPUs as “parts” and insisting they were platforms. Because a GPU by itself is just silicon. It only becomes useful when developers can actually do something with it—write code, debug it, optimize it, and ship it.

CUDA is the headline, but the real point is everything that came with it: the libraries, the tooling, the runtimes, the constant tuning that makes the hardware feel predictable and powerful. That’s what turned “a fast chip” into an ecosystem.

And it required a kind of organizational discipline most hardware companies never develop. Hardware teams naturally want to sprint to the next generation. Software teams want to keep expanding capability. NVIDIA kept both moving in lockstep—and kept paying the bill—because leadership understood the compounding effect: every improvement to the platform makes every next GPU more valuable.

That’s why rivals can match spec sheets and still lose the deal. The product isn’t only the chip. It’s the stack around it.

Long-Term Vision Over Short-Term Profits

CUDA looked like a distraction for years.

Gaming was where the money was. Wall Street could model it. CUDA, on the other hand, required years of investment before it produced obvious revenue. Analysts questioned the strategy. Why spend so much building software for a market that barely existed?

Huang’s answer, in practice, was to keep going anyway. NVIDIA treated CUDA as a foundational capability, not a quarterly initiative. The return didn’t show up right away because the use case hadn’t arrived yet. But when deep learning hit, NVIDIA didn’t have to scramble to invent a platform under pressure—it already had one, battle-tested and widely adopted.

Not every company can afford decade-long bets. But NVIDIA’s story shows why they’re so powerful when you can: paradigm shifts don’t reward the fastest follower as much as they reward the company that’s already built the on-ramp.

Surviving Near-Death Experiences

It’s hard to overstate how close NVIDIA came to not existing. The Sega Dreamcast failure wasn’t just a bad quarter—it was an extinction-level event. Earlier product stumbles didn’t help. The company survived only by getting brutally honest, brutally fast.

That’s what crisis does: it strips away vanity strategy and forces clarity. NVIDIA cut more than half the staff. It pivoted toward industry standards. It took Sega’s investment even after the partnership collapsed. None of those moves were pretty, but they were decisive.

And that scar tissue became an asset. Companies that have never been close to the edge tend to optimize for comfort. Companies that have survived the edge tend to optimize for survival—and survival builds a kind of resilience that’s hard to copy.

Creating and Owning a Category

GeForce 256 wasn’t the first graphics card. But NVIDIA didn’t frame it as “another graphics card.” They framed it as something new: the GPU.

That was marketing, yes—but it was marketing built on a real architectural shift. Hardware transform and lighting changed the division of labor inside the PC. The GPU wasn’t just painting pixels; it was doing core computation the CPU used to do. NVIDIA took that truth and wrapped language around it that the market could remember.

Category creation works when two things happen at the same time: the innovation is real enough to justify the claim, and the company is bold enough to name the category before someone else does. NVIDIA did both. And once the world adopted the word “GPU,” NVIDIA positioned itself not as a participant in a market, but as the company that defined it.

Developer Ecosystem as Competitive Moat

NVIDIA’s strongest defense isn’t a benchmark. It’s habit.

Millions of developers learned CUDA. Thousands of libraries and research projects assumed NVIDIA hardware. Entire academic and industry workflows were built around NVIDIA’s tooling. That ecosystem didn’t appear by accident—it was constructed through years of investment in documentation, developer support, education, and making CUDA free so adoption could spread without friction.

And once that adoption takes hold, it compounds. Every new developer makes the platform more valuable for the next one. Every new library makes it harder to switch. Every shipped project reinforces the default choice.

That’s the real lesson: in technology, ecosystems are gravity. Hardware advantages can be competed away. Developer ecosystems, once they reach escape velocity, are much harder to dislodge.

IX. Power Dynamics & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case: AI Is Still Day One

The bull argument starts with a simple claim: we’re still in the early innings of AI adoption.

Most enterprises today are experimenting—chatbots, copilots, small internal pilots—but they haven’t rebuilt their core workflows around AI yet. Bulls believe the real spending wave comes when AI stops being “a tool employees try” and becomes infrastructure companies depend on.

They also point out that training is only part of the story. Over time, inference—running trained models in production—should become the bigger workload as AI features spread into every product and business process. In that world, demand doesn’t just come from a few labs training frontier models; it comes from millions of applications needing real-time compute.

In this view, CUDA is still the trapdoor. There are alternatives, but none with the same maturity: the tooling, the optimized libraries, the battle-tested debugging and performance work, and the sheer size of the developer community built over nearly two decades. Competitors can ship impressive hardware, but the bull case says the hard part isn’t the chip. It’s everything around the chip.

Bulls also argue the hardware cadence is speeding up, not slowing down. Each generation brings big jumps, and Blackwell’s improvements over Hopper—on the workloads customers care about—raise the pressure to upgrade. In a competitive market, waiting can mean falling behind.

And finally, they return to the enterprise point: pilots aren’t production. If even a fraction of today’s experiments become always-on systems, the amount of deployed compute could expand dramatically.

The Bear Case: Competition and Valuation

The bear case starts from the opposite instinct: dominance attracts attacks, and NVIDIA has painted a target on itself.

AMD’s MI300 series is the most credible competitive hardware NVIDIA has faced in years, and major customers have publicly committed to deploying it. Intel, even if it lags near term, has the resources and staying power to remain a threat. But the deeper pressure comes from NVIDIA’s biggest customers: the hyperscalers. Google has TPUs. Amazon has Trainium. Microsoft has Maia. If the largest buyers decide they’d rather build than buy, NVIDIA isn’t just fighting rivals—it’s fighting its own demand base.

Then there’s geopolitics. China used to be meaningful revenue before export restrictions. Those restrictions could tighten, and other governments could impose their own controls. In a world where the product is strategically sensitive, access to markets becomes a policy question, not just a sales question.

And the cleanest bear argument is valuation. NVIDIA trades at levels that assume continued hypergrowth and durable dominance. A lot of optimism is already embedded in the price. If growth slows, if margins compress, or if customers diversify faster than expected, the downside can be sharp.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Michael Porter’s lens is useful here because it forces you to look past “great product” and into “how the industry behaves”:

Supplier Power: Moderate. NVIDIA relies heavily on TSMC for fabrication, which is concentration risk. NVIDIA’s scale makes it a priority customer, but it still can’t conjure capacity out of thin air.

Buyer Power: Rising. Hyperscalers buy in enormous volume, and they’re actively developing alternatives—both to lower cost and to gain leverage.

Threat of Substitutes: Growing. Custom silicon, alternative architectures, and even new computing approaches could peel off specific workloads over time.

Threat of New Entrants: Low. Competing at NVIDIA’s level requires deep technical talent, manufacturing access, and—most of all—a real software ecosystem.

Competitive Rivalry: Intensifying. The market is more contested than it’s been in a long time, driven by AMD’s resurgence and the hyperscalers’ willingness to invest.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s framework highlights why NVIDIA has been so hard to dislodge:

Scale Economies: NVIDIA’s volume helps on cost and access, though the best-funded players can narrow the gap.

Network Effects: CUDA has them. More developers lead to more libraries and applications, which attracts more developers.

Counter-Positioning: NVIDIA sells a full stack. A chip-only competitor has to change its identity—and its economics—to match that.

Switching Costs: Massive. CUDA code, CUDA tooling, CUDA-trained teams—it’s expensive to rewrite, retrain, and revalidate.

Branding: In AI infrastructure, “NVIDIA GPU” has become shorthand for “the standard.”

Cornered Resource: CUDA and its surrounding IP function like a unique asset that’s hard to replicate quickly.

Process Power: Decades of iteration have baked in know-how—optimization practices, architecture choices, system design—that doesn’t transfer easily.

The KPIs That Matter

If you want to track whether the bull story is holding—or the bear story is starting to bite—three indicators matter most.

First, data center revenue growth rate. That’s the clearest signal of whether AI infrastructure spending is still expanding at NVIDIA’s pace, and whether NVIDIA is still capturing it.

Second, gross margin trajectory. Those 70+ percent margins are the tell that NVIDIA isn’t being priced like a commodity chip vendor. If margins start sliding, it usually means competition or customer pushback is finally showing up in the numbers.

Third, customer concentration. When a handful of hyperscalers drive a large share of revenue, their purchasing decisions—and their success in building alternatives—can swing the entire business.

X. The Jensen Huang Factor

Jensen Huang has been NVIDIA’s CEO for the company’s entire life—thirty-three years and counting, an almost unheard-of run in fast-moving Silicon Valley. He was thirty when NVIDIA was founded. He’s sixty-three now, and he still runs the place like the next quarter could make or break everything.

That kind of continuity is rare because the tech industry usually doesn’t allow it. Companies churn through leaders as markets shift. Founders hand the keys to “professional” managers. Professional managers get swapped out when growth slows or the next platform wave arrives. At big tech companies, CEO tenures are usually measured in single-digit years.

Huang has stayed because he’s kept changing what NVIDIA is.

The NVIDIA of 1993 was a scrappy graphics-chip startup chasing PC gaming. The NVIDIA of 2006 was trying to convince the world that GPUs could be used for general-purpose computing. The NVIDIA of 2026 is, for all practical purposes, an AI infrastructure company. Same ticker symbol, same CEO, radically different missions—each one timed to a shift in what computing needed next.

He’s also not a hired operator playing with other people’s money. Huang owns about 3.6 percent of NVIDIA, which both aligns him with shareholders and makes the stakes intensely personal. As NVIDIA’s valuation surged, that stake alone climbed past $100 billion, turning him into one of the wealthiest people on the planet.

What makes Huang especially hard to categorize is how he blends traits that usually don’t come in the same package.

On one side, he’s deeply technical. He still involves himself in architecture discussions and understands the tradeoffs behind chip design decisions. Plenty of CEOs in this industry can talk strategy and outsource the details. Huang can live in the details—and often does.

On the other side, he’s a marketer with real stagecraft. NVIDIA launches aren’t just product announcements; they’re events, with Huang’s leather jacket and a storyline about where computing is going next. He understands that in technology, performance matters—but the narrative around performance can matter almost as much.

Then there’s the tattoo story, which has become part of NVIDIA folklore. Huang once promised that if the stock ever hit $100 a share, he’d get the company logo tattooed on his arm. When it happened, he did it. The photos spread everywhere: a CEO literally branded with his company.

The accolades followed. Fortune named him Businessperson of the Year in 2017. Harvard Business Review ranked him among the best-performing CEOs in 2019. Time put him on its list of the 100 most influential people in 2021.

But the more difficult achievement is internal: keeping a culture intact while the company explodes in size. NVIDIA grew from a few hundred employees into roughly thirty thousand. That kind of scale tends to dilute everything—speed, accountability, engineering sharpness, the sense that decisions matter. Huang has tried to fight that gravity with the same habits that defined the early years: direct communication, fast decision-making, and a willingness to make hard calls.

The open question is succession. At sixty-three, Huang could keep going for a long time. But NVIDIA is tightly intertwined with him—his taste, his intensity, his timing. When he eventually steps back, does the company keep its strategic coherence? Or was this era of NVIDIA, in some essential way, the Jensen Huang era?

XI. Reflections & Future Possibilities

What if Sega hadn’t written that five-million-dollar check in 1996?

NVIDIA was out of runway. The Dreamcast chip had failed. The company was staring at the most common ending in Silicon Valley: a quiet shutdown, a few résumés updated, some IP scattered to the wind. And it’s not hard to imagine the ripple effects. If NVIDIA dies there, the GPU revolution still happens in some form—but maybe it happens slower, under a different flag, with a different software stack. Maybe Intel takes graphics more seriously earlier. Maybe AMD becomes the center of gravity for parallel computing. Maybe deep learning still finds GPUs, but the “default” platform looks nothing like CUDA.

The point isn’t that Sega rescued some inevitable winner. The point is how contingent the whole outcome was.

That investment wasn’t automatic. It wasn’t even especially large relative to what chip development costs. It was a choice—made by executives who could’ve easily decided to cut bait, lawyer up, and walk away angry. Swap in a slightly different boardroom mood, a more adversarial negotiation, or a worse internal read on NVIDIA’s chances, and the company probably ends right there.

That should make anyone cautious about the way we talk about “inevitability” in tech. NVIDIA’s dominance is absolutely the result of real strategic excellence—category creation, relentless execution, and a software moat built over decades. But it also sits on a foundation of timing, luck, and a few moments where the coin could’ve landed the other way.

Looking forward, the next S-curves are tempting to sketch and hard to predict.

Quantum computing could eventually reshape what “compute” even means, though practical timelines are still uncertain. Robotics is the more immediate frontier: autonomous machines need perception, planning, and training in simulated environments, and NVIDIA has been pushing Omniverse and simulation as a way to build and test those systems before they touch the real world. And then there’s the metaverse idea—overhyped as a consumer narrative, but directionally true in one sense: if immersive, persistent 3D worlds ever do become mainstream, they will be hungry for graphics and compute on a scale that makes today’s gaming look small.

So, can anyone catch NVIDIA?

It’s an easy question to ask and a brutal one to answer, because “catching up” isn’t just about shipping a faster chip. It’s about shipping a credible alternative to an entire developer universe—tooling, libraries, workflows, training materials, institutional knowledge, and millions of lines of code written with NVIDIA as the assumption. That ecosystem took close to two decades to build. Beating it quickly would require either extraordinary investment or a genuine platform breakthrough that changes the rules. No one has done that yet.

One of the strangest parts of NVIDIA’s story is how long the opportunity stayed invisible.

For years, GPUs were seen as peripherals—important to gamers, valuable to designers, but not central to the computing world’s future. The idea that they would become the industrial machinery of artificial intelligence sounded absurd. Until it didn’t. And that’s often what the best opportunities look like in real time: narrow, slightly weird, easy to dismiss—right up until the moment they become obvious.

For founders, the lesson is that “small” markets can be wedges into enormous ones. NVIDIA’s beachhead was 3D gaming graphics. The real market turned out to be parallel computation everywhere. The job isn’t to predict the exact destination. It’s to recognize which narrow entry points could open into something far bigger.

For investors, the lesson is patience—and imagination. NVIDIA was investable because gaming graphics was a clear, fundable market. NVIDIA became historic because that market was a stepping stone to something no spreadsheet in 1993 could comfortably model. The best investments often have that shape: understandable enough to back, surprising enough to become legendary.

XII. Recent News

In late February 2025, NVIDIA reported its fiscal fourth-quarter 2025 results—and the same theme kept repeating: the data center business kept growing faster than expectations as more companies moved from “AI experiments” to actual infrastructure rollouts. Blackwell-based systems were starting to ship in real volume, and the limiting factor wasn’t demand. It was supply.

A few weeks later, at GTC in March 2025, Jensen Huang used the conference the way he often does: not just to talk about what NVIDIA could ship today, but to pull the market’s attention toward what comes next. He laid out architecture and system details for what NVIDIA expected to deliver in 2026 and beyond, reinforcing the company’s core weapon in this era—the cadence. Each new generation wasn’t framed as a small step forward, but as a dramatic leap that forces customers and competitors to keep moving.

On the business side, NVIDIA kept widening the surface area of its partnerships, pushing beyond cloud and labs into industries that look less like Silicon Valley and more like the real economy: automotive, healthcare, and telecom. The pitch was consistent: NVIDIA wasn’t just selling chips. It was offering the full stack—silicon, software, and systems—so customers could adopt AI faster than they could by stitching together components from multiple vendors.

The flip side of that success was attention from regulators. Across Europe and the U.S., competition authorities continued examining NVIDIA’s market position and business practices. As of early 2026, those reviews hadn’t concluded with enforcement actions—but the scrutiny itself was a reminder that when a company becomes infrastructure, it also becomes a policy question.

And geopolitics still sat in the background like a permanent constraint. U.S. export restrictions to China remained in place. NVIDIA continued offering products designed to comply with those rules, but China represented a smaller slice of revenue than it had before the restrictions tightened—less a growth engine, more a managed exposure.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings - NVIDIA Corporation Annual Reports (Form 10-K) - NVIDIA Corporation Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q) - NVIDIA Corporation filings on SEC EDGAR

Key Interviews and Presentations - Jensen Huang keynotes at GTC (GPU Technology Conference) - NVIDIA Investor Day presentations - Jensen Huang interviews on the Acquired podcast and the Lex Fridman podcast

Technical Deep-Dives - NVIDIA Technical Blog (developer.nvidia.com/blog) - CUDA Programming Guide - NVIDIA architecture whitepapers (Hopper, Blackwell)

Industry Analyses - Semiconductor Industry Association reports - Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and Bank of America semiconductor research - MIT Technology Review coverage on AI computing

Historical Sources - The Age of AI by Henry Kissinger, Eric Schmidt, and Daniel Huttenlocher - Chip War by Chris Miller - Stanford University Computer Science oral histories

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music