Omnicell: The Story of the Autonomous Pharmacy

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture it: a hospital room in 1992. Fluorescent lights, that constant hum, and a new father watching nurses rush in and out—opening drawers, checking cabinets, flipping through paperwork—hunting for basic supplies while his newborn daughter lies in a hospital bed.

Randall Lipps wasn’t daydreaming about startups. He was watching a system waste the most precious resource in the building: clinicians’ time. Not because anyone was careless—but because the hospital simply didn’t know, in real time, where things were or what was running low. And for Lipps, that wasn’t just frustrating. It was unacceptable.

This wasn’t a Hollywood “lightbulb moment.” It was anxiety, irritation, and then a cold realization: something fundamental in hospital operations was broken. Lipps went on to found Omnicell in September 1992 after seeing, firsthand, how inefficiently hospitals managed medications and supplies during his daughter’s hospitalization at birth. And he didn’t come at the problem like a healthcare lifer. He came at it like a logistics engineer.

Before Omnicell, Lipps worked in airline operations and logistics—most notably as Assistant Vice President of Sales and Operations for a division of American Airlines. In aviation, you track everything: planes, crews, luggage, fuel, departure times. Systems are designed so you can answer basic questions instantly, because the cost of guessing is enormous. Yet in that hospital room, the simplest version of “Where is it?” didn’t have an answer.

Lipps couldn’t shake the comparison. As he later put it: “We thought it was crazy that somebody could walk into a 7-11 and have a box of cereal scanned at the checkout counter to make sure you were charging somebody the right price. Yet a lot of the same kind of automation and technologies weren't available in hospitals to ensure patients were getting the right drug at the right time.”

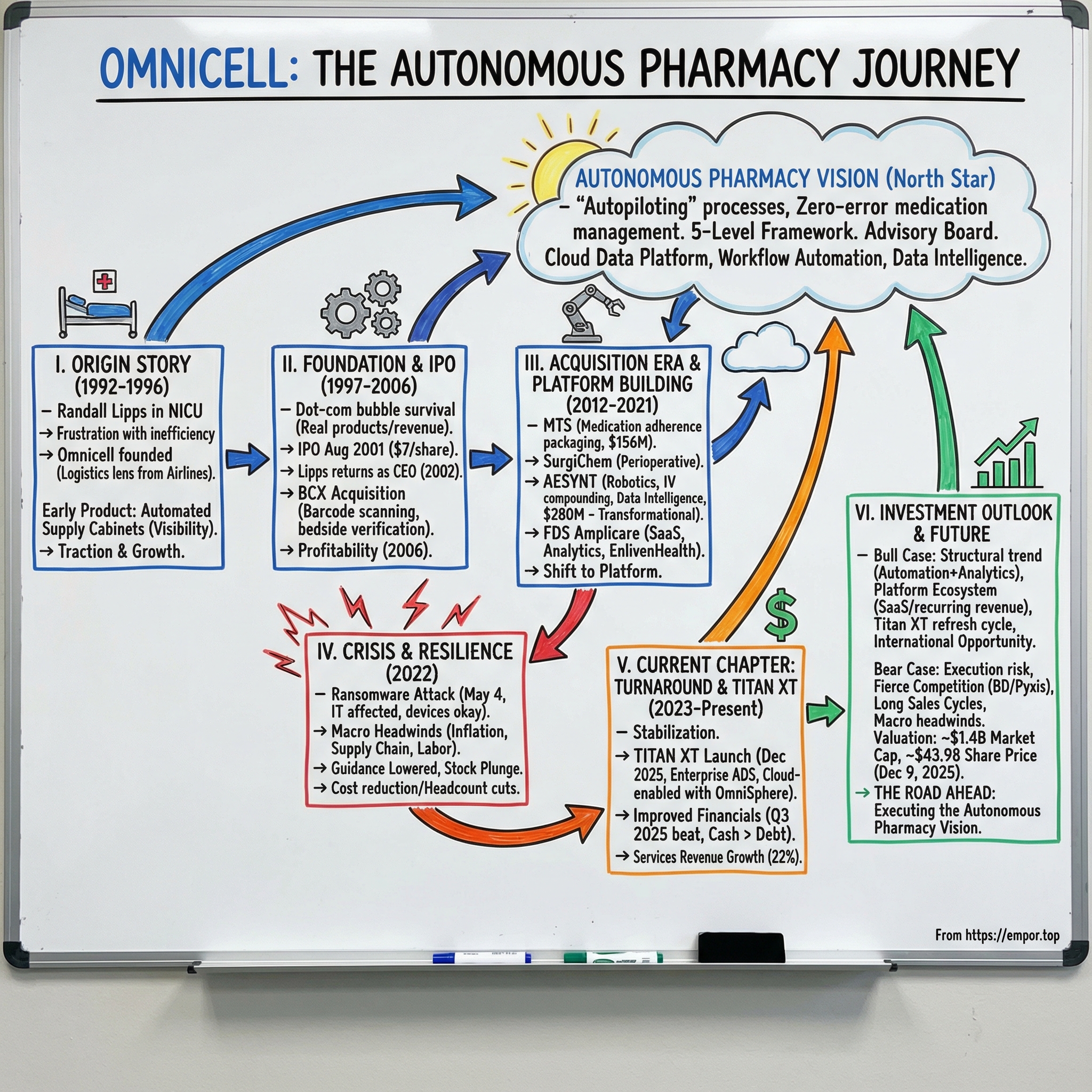

From that insight, Omnicell grew from a single product idea into a broad medication management platform—combining automation, data intelligence, and services—all oriented around a North Star that’s as ambitious as it sounds: the Autonomous Pharmacy, a world of zero-error medication management.

And here’s one of the most unusual parts of the story: the same frustrated father is still at the helm. Lipps has led Omnicell for more than three decades. The company became publicly traded in August 2001, and its solutions are now used in over 5,000 hospitals worldwide and over 40,000 institutional and retail pharmacies.

In late 2025, Omnicell is back on traders’ radar too—helped by a cluster of catalysts: a new flagship product, raised full-year guidance, improving technical momentum, and analyst upgrades. As of the afternoon session on December 9, 2025, Omnicell shares trade around $43.98, giving the company a market cap of roughly $1.4 billion.

This is a story about the hardest kind of disruption: bringing modern automation into an industry that lives and breathes risk aversion. Healthcare doesn’t “move fast and break things.” Healthcare moves slowly—because breaking things can mean breaking patients. And yet, over and over, Lipps convinced hospitals the bigger risk wasn’t adopting new technology. It was continuing without it.

So here’s our roadmap: we’ll go from a bedside observation in 1992, to early product traction, to a platform built through acquisitions, to the Autonomous Pharmacy vision—and the very real crises and constraints that tested the company along the way. Let’s dive in.

II. The Origin Story: From Airline Logistics to Hospital Floors (1992–1996)

It’s 1992, and Randall Lipps is in the neonatal intensive care unit at UCSF with his newborn daughter. Most parents in that moment are fixated on monitors and doctors. Lipps—trained as a logistics engineer—can’t help but notice something else: the system around the care.

Nurses aren’t just nursing. They’re searching. Searching for supplies. Searching for medications. Searching for the right paperwork. The work is urgent, high-stakes, and wildly analog. And the waste is everywhere—not because people don’t care, but because the hospital has no real-time way to answer basic questions like: What do we have? Where is it? Who used it? What do we need next?

Lipps watches the inefficiency and redundancy play out during those long hours at his daughter’s bedside—and he decides it shouldn’t be normal. In September 1992, he forms Omnicell Technologies, Inc. to build the software and hardware that could automate the unglamorous but mission-critical mechanics of medication management: ordering, stocking, tracking, and administering.

The mental model he keeps returning to isn’t healthcare. It’s aviation.

In airlines, you don’t “hope” the right equipment is on hand or “assume” the process will work out. You instrument the whole system. You track. You verify. You build in checks so humans can focus on judgment, not scavenger hunts. Lipps’s ultimate goal becomes an end-to-end chain of custody—moving medications and supplies from the receiving dock all the way to the patient’s bedside with accountability at every step.

To get there, he starts building. Lipps recruits Stanford graduate students and develops an early prototype designed to take mundane, error-prone tasks out of nurses’ hands—and put them into machines and software that never forget, never guess, and always log the transaction.

And remember: this is the early ’90s. There’s no Amazon. No modern cloud. The web isn’t yet the commercial platform it will become. Real-time inventory visibility—outside of highly engineered industries—still feels futuristic. But Lipps has seen complex logistics tamed before. He believes hospitals can be next.

By 1993, Omnicell begins commercial development of its first automated supply cabinets. These aren’t just locked boxes. They track transaction data, inventory levels, expenses, and patient billing—the operational truth that hospitals had been trying to reconstruct after the fact with clipboards and guesswork.

The concept is simple, almost obvious in hindsight: computerized cabinets that act like secure, accountable “vending machines” for medical supplies. A nurse opens a drawer, and the system records who accessed it, what was taken, when it happened, and which patient it was tied to. For many hospitals, this creates something they’ve never really had before: visibility.

In 1993, Lipps begins marketing these supply automation systems to community hospitals, government facilities, and large regional and national healthcare organizations—eyeing the roughly 5,800 acute-care hospitals in the United States.

And the early results are telling. By the end of 1995, sales reach $7.7 million. The following year, revenue nearly triples to $21.5 million—and late in 1996, Omnicell debuts its first pharmacy automation system.

That “nearly tripling” isn’t just a growth stat. It’s evidence of something deeper: hospitals weren’t merely intrigued by automation—they were ready for it. The problem Lipps spotted in the NICU wasn’t unique to one unit or one hospital. It was a systemic gap that everyone had learned to live with.

Omnicell’s early wedge is supply management, but the move into medication dispensing in 1996 is the real unlock. Supplies are about efficiency and cost. Medications are about safety. A missing item is inconvenient; the wrong medication can be catastrophic. The stakes—and the value of getting it right—jump dramatically.

What’s most impressive about this period is how Omnicell gets traction in a market that’s famously hard to sell into. Hospitals are conservative. Decisions are committee-driven. Change is painful. But the pain Omnicell is addressing is immediate and visible—especially to nurses, who become the internal champions because they feel the problem every shift.

By 1996, the foundation is in place: a founder with a logistics worldview, a product that creates accountability and visibility, and clear early product-market fit. Next comes the hard part—scaling through the chaos of the dot-com era, surviving an IPO that doesn’t go as planned, and turning a great idea into a durable platform business.

III. Building the Foundation: IPO, the Dot-Com Detour, and Early Expansion (1997–2006)

By the late 1990s, Omnicell had done the hard first thing: it proved the core idea worked. Hospitals were buying automated dispensing cabinets. Revenue was climbing. The “secure, computerized cabinet” wasn’t a science project anymore—it was a real product in real nursing units.

Now Lipps wanted to widen the aperture. And like every company alive in that era, Omnicell got pulled into the gravity well of the internet.

In September 1999, the company renamed itself Omnicell.com—a move that sounds cringe today, but in context was a signal: Omnicell wasn’t just selling hardware. It was trying to become the network that connected hospital supply and medication workflows.

Two months later came the Omnicell Commerce Network, an e-commerce service built around two web-based applications: Omni-Buyer and OmniSupplier. And OmniSupplier, in particular, fit neatly into Omnicell’s worldview: a secure dispensing system designed for nursing areas that administered supplies, automating the management and dispensing of medical and surgical items right where they were used.

The bet was straightforward: if Omnicell could connect purchasing to point-of-use dispensing—linking web ordering directly to cabinet-level inventory—then the cabinets wouldn’t just track supplies. They’d help run the supply chain.

Then the market turned.

Omnicell filed for an IPO in April 2000, and the timing could not have been worse. The dot-com bubble had peaked on March 10, 2000. By April 14, the Nasdaq Composite fell 9% in a single day, capping a week where it dropped 25%. The IPO window didn’t just narrow—it slammed shut.

And this is where Omnicell’s story diverges from the dot-com wreckage. Unlike the “eyeballs and vibes” companies, Omnicell had what Wall Street suddenly cared about again: real customers, real deployments, and real revenue. Hospitals still needed meds dispensed safely whether the Nasdaq was up, down, or on fire. But even with fundamentals, raising money in that environment was brutal.

Omnicell kept going anyway. In August 2001, the company finally priced its IPO at $7 per share. That same year, it changed its name back—this time to Omnicell, Inc. It wasn’t a flashy debut. It was a survival IPO. But it gave Omnicell what it needed: capital, credibility, and a public-company platform to keep building.

In 2002, Lipps made another pivotal move: he stepped into the CEO role, replacing Sheldon D. Asher. He’d been chairman since the beginning, but now he was back in the operator’s seat—pulling the company harder toward the end-to-end system he’d envisioned from the start.

That vision took a concrete leap in August 2003, when Omnicell acquired BCX Technology, Inc., maker of wireless handheld bar-code scanners. These devices could scan a patient’s wristband and verify a nurse’s ID, helping authorize and track medication administration.

This mattered because the cabinets—powerful as they were—mostly governed what happened at the cabinet. BCX pushed accountability closer to where risk lives: the bedside. Now Omnicell could help verify not just that a medication was removed, but that it was given to the right patient, by the right clinician, at the right time.

After the BCX acquisition, Omnicell held roughly 18% market share—making it the industry’s #2 player, behind Cardinal Health, Inc. (via Pyxis), which dominated with an estimated 60–70% share. That competitive reality shaped everything. Omnicell couldn’t out-scale the leader. So it had to out-innovate, out-serve, and keep expanding the footprint of what its system could do.

Financially, the company was maturing fast. Revenue pushed past $100 million in 2003, rose to $123 million in 2004, and reached $154 million by 2006—a year that also delivered $10.3 million in net income.

And the opportunity ahead was still enormous. Even after more than a decade of category-building by Omnicell and competitors, only about half of U.S. hospitals used automated medication and supply systems. Omnicell’s growth wasn’t just about stealing share—it was about converting an entire industry from manual processes to automation in the first place.

By the end of this period, Omnicell had become something it hadn’t been in 1992: a durable, profitable, publicly traded company with a clear strategic direction. The cabinets got it in the door. The IPO kept it alive. The bedside scanning pushed it closer to “end-to-end.”

But the bigger transformation—from a cabinet company into a platform company—was still to come.

IV. The Acquisition Era: Building the Platform (2012–2021)

Up through the mid-2000s, Omnicell was still largely understood as a “cabinet company”—best-in-class at automated dispensing on the nursing floor, steadily widening into adjacent workflows.

The next phase changed that identity entirely. Between 2012 and 2021, Randall Lipps used acquisitions as a lever to turn Omnicell from a product portfolio into a platform—one that could follow medication from the pharmacy, to the bedside, and eventually beyond the hospital walls.

Key Inflection Point #1: MTS and the Leap Outside the Hospital (2012)

In May 2012, Omnicell signed an agreement to acquire MTS Medication Technologies, Inc.—a global provider of medication adherence packaging systems—for $156 million, and then completed the deal.

This wasn’t just bolt-on revenue. It was a strategic statement: the future of medication management wouldn’t stop at discharge.

The rationale Omnicell put forward was straightforward: healthcare was shifting toward provider organizations that were accountable for patients across the full continuum of care, not just a single inpatient episode. If hospitals and health systems were increasingly responsible for outcomes after a patient went home, then helping ensure patients actually took their medications correctly became part of the job.

And the timing mattered. In the early 2010s, the Affordable Care Act accelerated the move toward value-based reimbursement and accountable care. Suddenly, “med adherence” wasn’t just a pharmacy problem—it was an outcomes problem.

MTS brought a concrete solution: sophisticated blister packaging systems that could sort pills into clearly marked, time-stamped packages. That packaging made it dramatically easier—especially for elderly patients and long-term care settings—to take the right medication at the right time. Just as importantly, it added a consumables component: recurring revenue from the packaging materials themselves.

Non-adherence, after all, is one of the most expensive and dangerous failure modes in healthcare—driving enormous waste each year and contributing to avoidable loss of life.

Operating Room Expansion: SurgiChem (2014)

Two years later, Omnicell expanded again—this time into the operating room—by acquiring UK-based SurgiChem Limited for £12 million. The logic was consistent with the broader strategy: extend automation and inventory control into high-cost, high-variability environments where mistakes and waste compound quickly.

But the truly transformational deal arrived in 2016.

Key Inflection Point #2: Aesynt and the Robotics Moment (2016)

On January 5, 2016, Omnicell completed its acquisition of Aesynt Holding Coöperatief U.A. (announced October 29, 2015). With Aesynt came what Omnicell had been building toward for years: deeper automation in the central pharmacy—not just cabinets on the floor.

At closing, Omnicell said the combined company would support approximately 4,000 acute care facilities worldwide, with annual revenue over $670 million and about 2,200 employees. Lipps framed it as a milestone in Omnicell’s history: expanding technology choice for customers while keeping a singular focus on simplifying medication management across the continuum of care.

The reason Aesynt mattered was simple: robots.

The acquisition added: - pharmacy robots for inventory management - IV compounding robotics designed to reduce human error - pharmacy data intelligence software

In Omnicell’s words, the deal created the broadest medication management product portfolio in the industry, particularly by strengthening central pharmacy and IV robotics.

Aesynt’s own lineage reads like a case study in how great technology can get “lost” inside big companies. The business began in January 1989 as Automated Healthcare, pioneering robotics to automate dispensing and administration of medication in hospital pharmacies—helping reduce errors and lower costs. It deployed robots in hundreds of hospitals, then was acquired by McKesson Automation in 1996.

But inside a massive drug wholesaler, a $150–$200 million automation business could struggle to command attention. In 2013, it was spun out to Francisco Partners and rebranded as Aesynt—a focused company again, ready to scale the technology.

Omnicell became the next focused owner—the one with the strategic incentive to integrate robotics into a broader medication-management platform.

Financially, Omnicell paid approximately $280 million, including repayment of Aesynt indebtedness and after adjustments. The acquisition was funded through cash on hand and borrowings under its Credit Agreement. To support the deal, Omnicell put in place a large, multi-part credit facility with Wells Fargo Securities—a clear signal the company was willing to use leverage to accelerate its push into a wider platform.

Key Inflection Point #3: COVID-Era Shift Toward SaaS (2020–2021)

Then came the pandemic, and with it a sharp pull toward remote operations, digital workflows, and higher-visibility supply chain data. In 2020–2021, Omnicell leaned harder into acquisitions focused on software and services, not just hardware.

Omnicell entered into a definitive agreement to acquire FDS Amplicare for cash consideration (subject to customary adjustments). The deal added a complementary suite of SaaS financial management, analytics, and population health tools into Omnicell’s EnlivenHealth™ division.

Omnicell explicitly positioned the move around the broader trendline that COVID accelerated: care delivery digitizing (including telehealth) and shifting to a wider range of settings, from hospital-at-home programs to local pharmacies.

Strategically, it was a bet on recurring, higher-margin software revenue. Put plainly: rather than depending primarily on hardware refresh cycles, Omnicell was paying for capabilities that could scale through the cloud and produce steadier, more predictable revenue. Amplicare’s tools—and its network of independent retail pharmacies—dramatically expanded EnlivenHealth’s reach.

As Scott Seidelmann, executive vice president and chief commercial officer, put it: with these new capabilities, EnlivenHealth could offer the industry’s most comprehensive suite of digital technology solutions designed to help retail pharmacies and health plans grow in an increasingly digital era.

A Platform—And a New Kind of Complexity

By 2021, Omnicell’s footprint spanned nursing floor automation, central pharmacy robotics, IV compounding, medication adherence packaging, and retail pharmacy software. The arc is clear: cabinets got Omnicell into the building; acquisitions helped it reach the entire medication journey.

But there’s no free lunch here. A platform assembled through M&A comes with a tax: integration risk. Combining that many products, teams, workflows, and customer types—while still shipping new innovation—is extraordinarily hard.

And that difficulty would matter a lot in the next chapter.

V. The Autonomous Pharmacy Vision: Omnicell’s North Star

In any company, there’s a difference between strategy—what you’re doing this year—and vision—where you’re trying to take the whole industry over a decade. For Omnicell, that vision has a name, and it’s the thread that ties together everything we’ve covered so far: the Autonomous Pharmacy.

Lipps’s go-to analogy is the one that shaped him long before Omnicell existed: aviation. Commercial planes used to depend entirely on human pilots for every step of flight. Today, much of flying is handled through automated control systems—an “autopilot” model that makes outcomes more consistent and reduces the chance of human error. Omnicell’s bet is that pharmacy can follow the same arc: automate the repeatable, high-risk parts of the medication journey so clinicians can focus on care, not process.

At its core, the Autonomous Pharmacy is a push to replace manual, error-prone work with systems that are safer, more reliable, and more efficient.

A “Levels of Autonomy” Model—For Pharmacy

Omnicell and its partners didn’t stop at a slogan. They built a framework—explicitly modeled on the Level 1 through Level 5 autonomy scale used for autonomous vehicles—to define what “autonomous” actually means in a pharmacy setting.

The result is a five-level roadmap that spans nine pharmacy work processes, with each level representing increasing technological capability and workflow improvement. The end state is ambitious: near error-free medication management—maximizing the benefit of medication while minimizing harm, waste, and cost.

And importantly, this framework isn’t a solo Omnicell invention. It’s been shaped by the Autonomous Pharmacy Advisory Board: a coalition of health-system pharmacy leaders, nursing leaders, and pharmacy informaticists aligned around the idea that getting to “autonomous” requires more than buying a new machine. It requires a stepwise transformation across enterprise structure, data intelligence, automation, IT infrastructure, and human activity.

Not Just a Vision—A Buying Path

There’s a business masterstroke embedded here: the framework creates a shared language and an upgrade path.

Hospitals can locate themselves honestly—“we’re at Level 1 in these workflows, Level 2 in those”—and then map a practical route forward. For Omnicell, that turns a sprawling transformation into something hospitals can plan, budget, and execute over time. It also positions Omnicell as the long-term partner for the journey, not a one-and-done vendor.

By Omnicell’s account, nearly 50% of the Top 300 U.S. health systems (as defined by Definitive Healthcare) are partnering with the company on this Autonomous Pharmacy roadmap. As Lipps describes it, industry leaders have coalesced around building “a zero-error, fully automated medication management infrastructure” using a combination of hardware, software, and technology-enabled services designed to improve quality, reduce cost, and increase human efficiency.

Proof It Can Work: Texas Children’s Hospital

The vision sounds lofty—until you see what it looks like when a major institution leans in.

Texas Children’s Hospital (TCH), one of the largest pediatric hospitals in the United States, uses Omnicell technology to support medication management for mother-baby and pediatric populations. The outcome TCH highlights is the kind of metric hospital operators actually care about: about 95% real-time visibility into inventory, which helped drive a 16% reduction in medication management costs—annual savings measured in the millions.

The Stack Behind “Autonomous”

A fully autonomous pharmacy isn’t one product. It’s layers:

- A cloud data platform to integrate systems and enable advanced analytics.

- Workflow automation to reduce reliance on manual touchpoints and repetitive tasks.

- Data intelligence to turn automation into better decisions—because automation without intelligence is just faster complexity.

In other words: robots and cabinets are necessary, but they’re not sufficient. The goal isn’t to mechanize today’s messy workflows. It’s to redesign them so errors become harder to make in the first place.

Why This Matters: The Size of the Prize—and the Mess

The medication system is enormous. Medication costs represent roughly one-seventh of all healthcare spending, about $508 billion per year. And the process that governs that spending—ordering, dispensing, administering, tracking—still relies on a web of manual steps that are complex, variable, and inherently error-prone.

One former chief pharmacy officer at the University of Michigan described just how fragmented it can get: an internal audit found the organization was running dozens of separate systems to keep the medication-use process functioning. Very few of them communicated with each other, which meant the “integration layer” was… people. Staff bridging gaps manually—labor-intensive on a good day, risky on a bad one.

That fragmentation is both Omnicell’s opportunity and its hardest execution challenge. The Autonomous Pharmacy vision is compelling. But delivering it means integrating messy environments, changing deeply ingrained workflows, and persuading risk-averse health systems to trust automation in the most sensitive domain imaginable: getting the right medication to the right patient, at the right time.

VI. Crisis & Resilience: The 2022 Challenges

Big visions don’t get a free pass from reality. And for Omnicell, 2022 delivered the kind of reality check that hits from multiple angles at once: cybersecurity shock, macro pressure, and suddenly cautious customers.

The Ransomware Test

On May 4, 2022, Omnicell determined that certain information-technology systems had been affected by a ransomware attack, impacting some internal systems. The company disclosed the incident in an SEC filing, and the market immediately began asking the obvious questions: What broke? What data is at risk? And—most importantly in healthcare—did patient care get disrupted?

Omnicell’s assessment was clear on the most critical point: customer medication-management devices were not disrupted. Automated dispensing systems and robotic equipment in hospitals kept running.

That detail matters. A ransomware event that halted medication dispensing in a hospital wouldn’t just be an IT outage—it could become a patient safety crisis. Even without that worst-case outcome, the attack was still a serious operational and reputational blow, especially for a company whose brand promise is safety, reliability, and control.

Omnicell said it took immediate steps to safeguard the integrity of its IT environment—working with cybersecurity experts, containing the incident, and implementing business continuity plans to restore and support continued operations.

The Worst Timing: Cyber Meets Capital Freezes

The ransomware incident landed in an already deteriorating business environment. On an earnings call, Randall Lipps pointed to broad industry headwinds—labor challenges, health system capital budget freezes, and purchase delays—all of which are poison for a business that still depends heavily on large, complex system deployments.

Then came the market’s verdict.

Shares sold off sharply over the course of the week, falling from the high-$70s into the low-$50s, and briefly touching the high-$40s. Investors weren’t reacting to one issue; they were repricing a stack of risks all at once: security, execution, and demand.

Inflation, Supply Chain, and Lowered Guidance

Underneath it all was the grind of 2022’s macro backdrop. Persistent inflationary pressure—particularly semiconductor and component costs—continued to create challenges, and Omnicell cut its 2022 guidance.

Even while noting execution in a difficult year, Lipps framed the moment as one of endurance:

“Omnicell delivered results generally exceeding our revised outlook for the fourth quarter and full year 2022 in the face of continued headwinds and macroeconomic uncertainty…”

He also highlighted an internal milestone: CFO Peter J. Kuipers had played “an important role” in scaling the company from nearly $500 million in annual revenue to $1.3 billion in 2022.

A CFO Transition, and More Uncertainty

As if the market needed another variable, Omnicell also announced that Peter J. Kuipers would step down as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, effective July 1, 2023. Leadership transitions can be healthy, but in a period of external stress, they often read as one more source of uncertainty.

Weak Demand Rolls Into 2023—and Cost Cuts Follow

The demand softness didn’t magically clear when the calendar flipped. In 2023, Lipps struck a more sobering tone:

“The team delivered strong cost management and operational discipline this quarter. However, I am disappointed with the weakness in demand that we are seeing and accordingly, we have updated our near-term outlook. We are taking actions to manage the business that are intended to reduce our cost structure…”

Those actions turned concrete. On November 23, Omnicell committed to a headcount reduction plan as part of expense containment—broad-based cuts intended to resize the cost structure to match weaker demand.

The Investor Question: Setback or Structural?

By this point, the stock chart told its own story. Over the three-year stretch from the 2022 peak, Omnicell shares fell 74.58%.

For long-term investors, the question narrowed to one fork in the road: was Omnicell experiencing a temporary, macro-driven drawdown—made worse by a one-time cybersecurity event—or were these signs of something more structural?

Because the answer would determine what comes next: a recovery fueled by product cycles and a services transition… or a prolonged rebuild.

VII. The Current Chapter: Turnaround & Titan XT (2023–Present)

By late 2025, the narrative around Omnicell looked very different from the one investors were telling in 2022 and early 2023. The company that had spent the previous chapters managing shocks—cyber, macro, and demand—was showing signs of stabilization. And it was pairing that stabilization with something Omnicell knows how to do well: ship a major product cycle.

On December 8, 2025, Omnicell announced Omnicell Titan XT—a new, enterprise version of its automated dispensing system (ADS). Management positioned Titan XT as “transformational,” designed to combine proven automation hardware with cloud-driven intelligence to support increasingly complex health systems.

Randall Lipps framed the launch as more than a cabinet refresh:

“The introduction of Titan XT marks a significant milestone for Omnicell and the journey to cloud-enabled, autonomous medication management. Starting with nursing floors, we are now focused on integrating every care area into the OmniSphere platform to build what we believe will be the most complete, connected automation ecosystem in healthcare.”

Titan XT: Hardware That Pulls the Cloud Into the Cabinet

Titan XT’s strategic importance is the way it ties Omnicell’s legacy strength—floor-based dispensing automation—to its newer bet: an enterprise cloud platform.

Titan XT is powered by OmniSphere, Omnicell’s cloud-based, HITRUST-certified medication management platform. OmniSphere is designed to unify what historically has been fragmented across units and facilities: user management, task guidance, a global formulary, and perpetual inventory management—all in service of a connected, enterprise-wide medication management ecosystem.

In other words, Titan XT isn’t just “a better cabinet.” It’s intended to be a front-end node in an Omnicell-wide network.

Replacement Cycle, Premium Pricing, and the Rollout Timeline

Titan XT integrates with OmniSphere and is expected to primarily replace older XT systems introduced in 2017—the kind of installed-base refresh cycle that can drive meaningful bookings if customers buy in.

Omnicell said the system would be initially configured for nursing floors, with availability expected to begin in the second half of 2026. The company also indicated it plans to price Titan XT at a premium to current XT systems, pointing to OmniSphere-enabled visibility and tighter enterprise control of medication inventory as the primary value drivers.

Titan XT is available for purchase in the United States, with international purchasing anticipated later in 2026. Omnicell also expects ongoing OmniSphere releases to begin in early 2027.

Wall Street Likes a Clear Product Catalyst

The early market read was constructive. On December 9, 2025, Benchmark reiterated its “Buy” rating on Omnicell and raised its price target—explicitly citing Titan XT as a driver of growth and renewed product momentum.

Financial Momentum: Better Than the Lows

The company’s financial picture also looked healthier than it did at the 2022–2023 trough.

Omnicell’s third-quarter 2025 results exceeded analyst expectations, with earnings per share of $0.51 versus a $0.36 consensus estimate. Management also raised full-year 2025 revenue guidance to $1.177–$1.187 billion, reflecting firmer demand into year-end.

Just as important: Omnicell exited Q3 2025 with more cash than debt. In plain English, the balance sheet wasn’t a looming problem—it was a source of flexibility.

And the business mix was shifting, too. Omnicell’s services business had grown to 22% of revenue, reinforcing the long-term strategy to lean more on recurring revenue streams rather than living and dying by hardware cycles.

The Bull Case: Automation Isn’t a Fad—It’s the Operating System

At a high level, the optimistic view of Omnicell rests on a few converging forces:

- Structural pressure: Hospitals and health systems are being squeezed to reduce costs and cut medication errors.

- Automation + analytics: This is not a trend that cycles out; it’s a multi-decade modernization wave.

- Platform transition: A gradual shift toward recurring SaaS and services—if executed—can mean higher margins and more predictable cash flows.

International: The Long Runway

Outside the U.S., Omnicell sees a market that’s still early—health systems becoming more aware of what automation can do, and governments and private entities investing more heavily in healthcare IT.

Omnicell’s international efforts span Canada, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia-Pacific. And with the international market described as less than 1% penetrated, with only a small number of hospitals adopting medication control systems, management has pointed to expansion abroad as a strategic priority.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape

Zooming out from Titan XT and OmniSphere, it helps to remember a simple truth about Omnicell’s world: this is a market where you don’t win because you have the prettiest UI. You win because hospitals trust you to run one of the most safety-critical workflows they have—reliably, every day, under stress.

That reality shapes the competitive landscape. Pharmacy automation is consolidated at the top—a few giants with deep product portfolios and long customer relationships—then fragmented below, with a long tail of specialists and adjacent IT vendors. One market-share analysis (built from secondary research and validated by primary respondents) ranks players based on revenue from pharmacy automation solutions, product breadth and depth, innovation, and approvals and launches. In that analysis, the top three are:

- Becton, Dickinson and Company (BD) (U.S.)

- Omnicell, Inc. (U.S.)

- KUKA AG (Swisslog Healthcare) (Germany)

These companies lead through scale, installed base, and continuous product investment.

The backdrop is favorable: the global pharmacy automation market is expected to grow steadily, with projections suggesting it could more than double over the coming years.

The BD Behemoth (Pyxis)

The market leader deserves special attention. BD is a global manufacturer of pharmacy automation solutions, and it reinforces its position primarily through organic investment—especially in R&D. BD owns Pyxis, the best-known brand in automated dispensing cabinets, which has historically dominated that category with an estimated 60–70% market share.

In other words: Omnicell isn’t competing with a niche player. It’s competing with a juggernaut that has been embedded in hospital workflows for decades.

Omnicell: The Platform Challenger

Omnicell remains one of the most dominant companies in the sector, with a broad lineup of pharmacy automation systems and strong brand recognition. Strategically, it has leaned heavily on inorganic expansion—using acquisitions to widen the footprint from cabinets to central pharmacy robotics, IV automation, adherence packaging, and software and services.

That breadth is both an advantage and a burden: it increases Omnicell’s relevance across the medication journey, but it also raises the bar on integration, support, and product coherence.

The Wider Field: Big Players, Specialists, and Adjacent Giants

Beyond the top tier, competition comes from a mix of direct automation vendors and adjacent healthcare IT players. Key names include:

- Becton, Dickinson and Company (U.S.)

- Omnicell, Inc. (U.S.)

- KUKA AG (Swisslog Healthcare) (Germany)

- Baxter International Inc. (U.S.)

- Capsa Healthcare (U.S.)

- Oracle (U.S.)

- Yuyama Co., Ltd. (Japan)

- ARxIUM Inc. (U.S.)

- McKesson Corporation (U.S.)

The implication is important: Omnicell is not only fighting “cabinet competitors.” It’s fighting for mindshare and budget inside complex health systems where multiple vendors can plausibly claim to “own” parts of the medication workflow.

Market Structure: Regulation, Regions, and Why North America Leads

North America remains the largest pharmacy automation market, with about 41% share in 2025, helped by large installed bases and ongoing product launches. The regulatory environment also pushes automation forward: in the U.S., bodies such as the FDA, DEA, and HIPAA shape strict expectations around medication handling, security, and data governance—raising the stakes for compliance and nudging institutions toward systems that reduce errors and improve auditability.

Competition Creates Pressure—Especially on Price

Omnicell continues to take share from traditional providers of medication management and supply-chain solutions, but it faces sustained competitive intensity from major players running their own expansion programs. In practical terms, that can translate into pricing pressure and margin compression, especially when customers run competitive procurement processes.

How the Industry Behaves: Porter’s Five Forces

From a Porter’s Five Forces lens, the pharmacy automation industry has a distinctive profile:

Threat of New Entrants (Low to Moderate): Healthcare IT is notoriously hard to break into. Sales cycles are long—often more than a year—because systems are expensive and purchasing decisions involve many stakeholders. Those realities create natural barriers. Still, well-funded technology companies could attempt to enter with new approaches.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Moderate): Large hospital systems can negotiate aggressively. But once cabinets, software, and integrations are deployed—and staff are trained—switching costs become very high, limiting buyer power after the initial purchase.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low to Moderate): Omnicell sources components from a range of suppliers. The supply chain disruptions of 2022 highlighted some vulnerability, but suppliers generally don’t have extraordinary leverage.

Threat of Substitutes (Low): The main alternative to automation is manual process—and that’s increasingly unacceptable given safety, efficiency, and compliance demands.

Competitive Rivalry (High): The leaders fight hard for enterprise accounts, and competition shows up in features, service levels, implementation support, and price.

Why Omnicell Has Staying Power: Helmer’s 7 Powers (The Relevant Ones)

Using Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, Omnicell’s most relevant sources of defensibility are:

Switching Costs: Once a hospital installs Omnicell cabinets, integrates them with its EHR and pharmacy systems, and trains staff, switching becomes expensive, disruptive, and risky—creating meaningful lock-in.

Scale Economies: As the #2 player behind BD, Omnicell benefits from scale in R&D, manufacturing, and service delivery—though not at BD’s level.

Network Effects (Emerging): If OmniSphere connects more customers and generates more data over time, its value could increase through stronger benchmarking and predictive analytics. This is not a guaranteed flywheel, but it is a plausible one.

International: Still Early, Still the Long Runway

The international opportunity remains largely untapped. Omnicell’s international operations include sales efforts across Canada, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia-Pacific. With international adoption described as less than 1% penetrated, and only a small number of hospitals using medication control systems, Omnicell has said it intends to expand into new markets it views as strategic.

Investor KPIs to Watch

For investors tracking whether the turnaround becomes durable, two metrics are especially telling:

1. Services Revenue as a Percentage of Total Revenue

This captures the shift from a hardware-heavy model to recurring revenue. Omnicell’s services business is now 22% of revenue. The trajectory matters as much as the number.

2. Advanced Services Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR)

Within services, Advanced Services (SaaS solutions, analytics, and managed services) is the highest-quality recurring revenue stream. Omnicell has indicated Advanced Services is expected to make up approximately 20% to 30% of total revenue by 2025. Tracking ARR and mix here is a direct read on whether the OmniSphere-led strategy is translating into durable economics.

IX. Investment Considerations: The Bull and Bear Cases

After three decades of building Omnicell into a billion-dollar business, Randall Lipps and his team face the question public markets always ask next: not can you build, but can you compound? In late 2025, the investment case comes down to a handful of debates—about execution, competition, and whether the Autonomous Pharmacy vision turns into durable economics.

The Bull Case

1) The demand drivers are structural, not cyclical.

Hospitals and health systems are under constant pressure to cut costs, improve outcomes, and operate through staffing shortages. Medication automation and analytics speak directly to all three. If anything, the “do more with less” mandate is becoming the default operating condition.

2) Titan XT can restart the flywheel.

A flagship product refresh matters in this category because of the installed base. Titan XT has the potential to trigger a replacement cycle for older XT systems (introduced in 2017) and win new accounts—especially if it delivers on the promise of tighter integration with Omnicell’s cloud and analytics stack.

3) The business mix is moving toward recurring revenue.

Omnicell is steadily shifting toward SaaS and services. If the transition sticks, it can mean higher margins and more predictable cash flows than a model dominated by hardware cycles and one-time deployments.

4) The balance sheet gives them room to operate.

Omnicell exited Q3 2025 with more cash than debt. That liquidity matters: it gives management flexibility to keep investing through downturns, fund product development, and pursue opportunistic acquisitions without being forced into defensive moves.

5) Autonomous Pharmacy creates an upgrade path—at scale.

The Autonomous Pharmacy framework isn’t just a vision; it’s a roadmap that can drive multi-year expansion within existing customers. Omnicell says nearly 50% of the Top 300 U.S. health systems are already partnering on that journey—an installed base with a built-in reason to keep moving “up the levels.”

6) International is a long runway.

With overseas adoption of medication control and automation still relatively low—and the international market described as less than 1% penetrated—growth outside the U.S. could become meaningful if Omnicell executes.

The Bear Case

1) Execution risk is still the headline risk.

A 74.58% stock decline over three years and uneven earnings aren’t just “bad luck.” Since 2022, Omnicell has repeatedly disappointed on guidance, which raises a fundamental concern: can management forecast—and therefore manage—the business with enough reliability to earn a re-rating?

2) Competition is relentless, and BD is a heavyweight.

BD’s Pyxis remains the category leader and continues to invest. In a market where enterprise deals are large and procurement is competitive, that can translate into pricing pressure and margin compression—especially if customers see cabinets as increasingly interchangeable.

3) Sales cycles are long, and visibility is fragile.

Healthcare IT purchasing is committee-driven and risk-averse. Omnicell’s automation deals can take more than a year, which means small shifts in sentiment—macro uncertainty, budget freezes, leadership turnover—can quickly turn into delayed or canceled projects.

4) Macro headwinds can linger.

Inflationary pressure, supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and geopolitical instability haven’t disappeared. Many health systems still face constrained capital budgets, and capital intensity is the enemy of near-term bookings.

5) The SaaS transition isn’t “free.”

The logic of recurring revenue is compelling; the execution is hard. Plenty of historically hardware-led companies stumble when they try to become software and services platforms—especially when customers want the subscription benefits without paying subscription prices.

Valuation Context

As of December 9, 2025, Omnicell’s market capitalization is roughly $1.4 billion. The consensus analyst rating is “Hold,” and the average twelve-month price target from analysts who have covered the stock in the last year is about $43.00.

In other words: the market isn’t pricing Omnicell as a broken company—but it isn’t giving it the benefit of the doubt, either. From here, the next 12–18 months likely come down to execution and margin improvement through 2025–2026. There’s upside if Titan XT and OmniSphere translate into real bookings and recurring revenue growth—but the optimism remains constrained by inconsistent results and persistent margin pressure.

X. Conclusion: The Road Ahead

Omnicell’s story is, at its core, the story of a single observation in a hospital room—and a founder who refused to let it go.

Back in 1992, Randall Lipps watched nurses burn time on scavenger hunts and paperwork because the hospital didn’t have real-time visibility into what it had, where it was, and who was using it. His core insight—that hospital logistics and medication workflows were years behind what other industries already considered table stakes—turned out to be exactly right.

From that starting point, Omnicell grew from a cabinet product into a broad medication management platform serving thousands of hospitals and tens of thousands of pharmacies worldwide. But the path wasn’t smooth. The company lived through the dot-com era, navigated a major ransomware incident, and then ran into the post-pandemic reality of constrained hospital capital budgets and delayed purchasing cycles. Resilience, in other words, has been a constant requirement. The open question is whether that resilience now turns into durable, compounding shareholder returns.

The company’s boldest bet is also its clearest North Star: the Autonomous Pharmacy—a healthcare system defined by zero-error medication management, delivered through a combination of hardware, software, and services. It’s an enormous vision. Whether it becomes industry reality—and whether Omnicell captures the economic upside of enabling it—remains to be seen.

What is clear is that the problem Lipps identified three decades ago is still far from solved. International penetration remains minimal. The market opportunity is real. The competitive dynamics are unforgiving. And execution—product quality, integration, deployments, service delivery, and the shift to a recurring-revenue model—is the whole game.

For investors, the question isn’t whether pharmacy automation matters. It does. The question is whether Omnicell—despite larger rivals—can translate a 30-year head start and a comprehensive portfolio into consistent growth, improving profitability, and a business model that earns a higher level of confidence from the market.

As of the afternoon session on December 9, 2025, Omnicell shares traded around $43.98, giving the company a market capitalization of roughly $1.4 billion.

That’s why Titan XT matters. It’s not just a new product. It’s a potential inflection point—a chance to refresh the installed base, deepen the OmniSphere platform connection, and make the Autonomous Pharmacy feel less like a slogan and more like a roadmap customers are actually buying.

As Lipps put it: “The introduction of Titan XT marks a significant milestone for Omnicell and the journey to cloud-enabled, autonomous medication management. Starting with nursing floors, we are now focused on integrating every care area into the OmniSphere platform to build what we believe will be the most complete, connected automation ecosystem in healthcare.”

Whether that belief turns into shareholder value is the question that will define Omnicell’s next chapter—and ultimately determine how history judges a three-decade mission to automate one of healthcare’s most critical workflows.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music