Ouster: The Quest to Give Machines Eyes

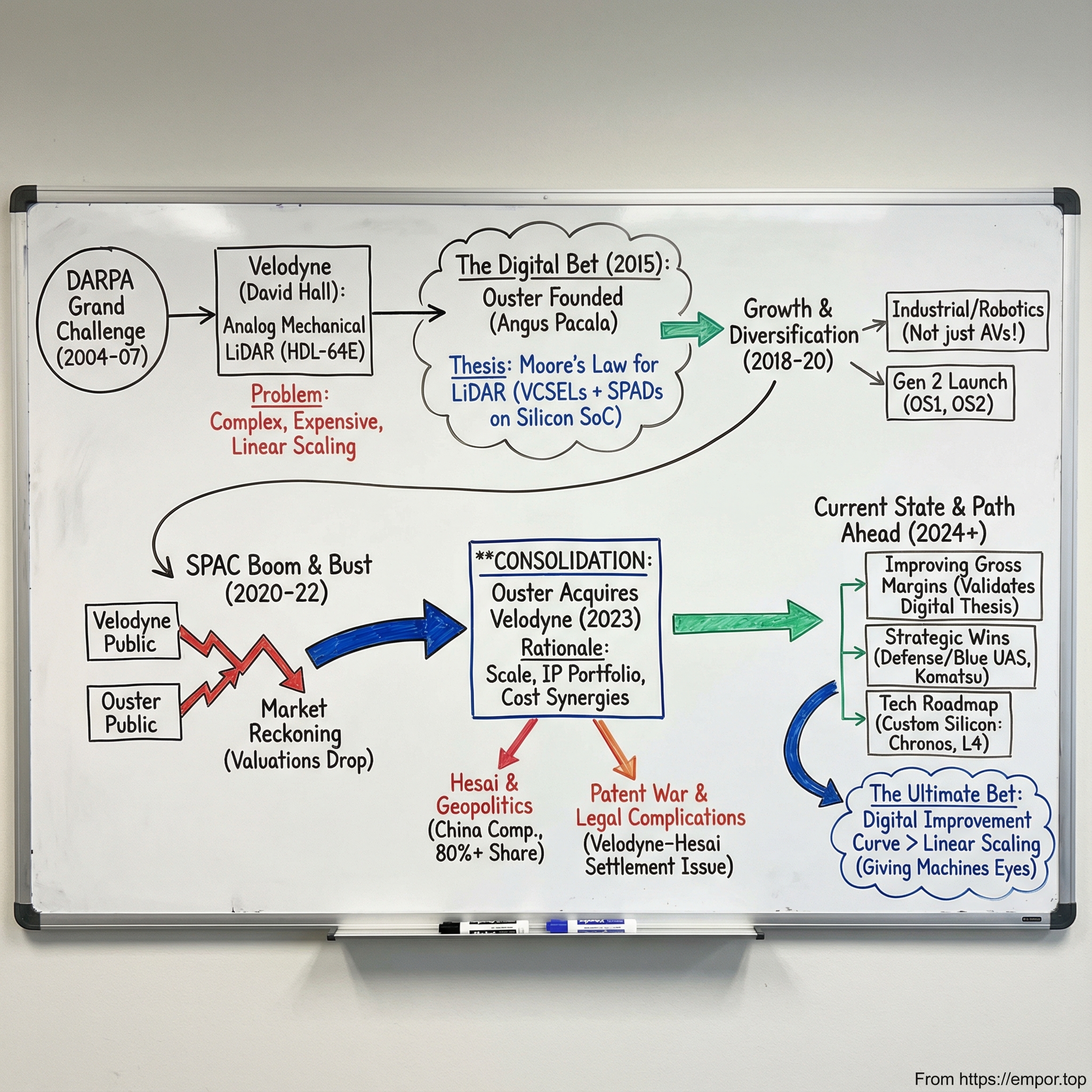

Introduction: A Tale of Digital Disruption

In the spring of 2023, something almost impossible happened in the lidar world. Ouster, a startup founded in 2015 by engineers who’d walked away from a rival lidar company, completed its acquisition of Velodyne—the company that had helped define modern, real-time 3D lidar for autonomous vehicles. In an industry that spent a decade crowning kings, Ouster didn’t just compete with the incumbent. It swallowed it.

By 2024, Ouster had grown revenue meaningfully versus the prior year. More importantly, it had become one of the last pure-play lidar companies still trading on a U.S. exchange—still standing after a brutal shakeout that included failed bets, bankruptcies, and the emergence of powerful Chinese competitors.

So how did we get here? How did a technology that proved itself in a desert robot race end up at the center of autonomous vehicle dreams, patent battles, and geopolitical tension—while also riding one of the most dramatic SPAC boom-and-bust cycles in recent memory?

This is a story about sensors: the hardware that lets machines perceive the world in three dimensions. It’s a story about an old fight—analog versus digital—playing out in a new arena. It’s about Moore’s Law trying to break into a category that had been dominated by mechanical complexity and high prices. And it’s about what happens when a young company looks at an entire industry and decides the fundamentals are wrong.

At the center is Angus Pacala, a Stanford-trained engineer who believed lidar should be built like a chip product, not a bespoke mechanical instrument—and was willing to bet Ouster on that conviction.

The arc is bigger than one company. We’re going to trace the DARPA roots that kicked off the modern autonomy era, the “Moore’s Law moment” that promised to change lidar economics, the SPAC wave that poured fuel on the fire, and the consolidation that followed when reality arrived. Along the way: boardroom drama, patent wars, and the question that refuses to go away for anyone building autonomy—can machines ever truly see?

The Prehistory: How Lidar Became the Eyes of Autonomy

The DARPA Grand Challenge and a Subwoofer Inventor's Epiphany

To understand Ouster, you first have to understand the company it would eventually absorb. And to understand that company, you have to start with a subwoofer.

David Hall founded Velodyne in 1983, building high-end audio equipment for serious listeners. For years, he was the guy who made bass feel like physics. But Hall wasn’t just an audio entrepreneur. Over time, his curiosity pulled him into adjacent worlds—robotics, semiconductors, automation—and even hands-on combat-robot competitions like Robot Wars, where sensors stop being theoretical and start being the difference between working and failing.

Then DARPA lit the fuse.

In 2004, Hall joined the first DARPA Grand Challenge, a U.S. Defense Department-backed competition daring teams to build a vehicle that could drive itself roughly 150 miles through the Mojave Desert. The prize money was real—$1 million at first, later $2 million for the 2005 race—but the real objective was bigger: push autonomous ground vehicles forward fast.

Hall initially leaned on stereo cameras, like many teams did. But the desert has a way of exposing weak assumptions. After talking with other competitors and living through the limitations firsthand, he shifted his attention to lidar. Cameras could see, but they couldn’t reliably measure depth in all conditions. Hall later summed up the problem bluntly: StereoVision wasn’t enough. An autonomous system needed a sensor that could see in 360 degrees, work day and night, and do it in real time.

Hall decided to build it.

The 2005 Grand Challenge became the forcing function. He got the idea to enter early that year, and by September he had installed a first prototype—an early version of what would become Velodyne’s breakout product, the HDL-64E.

The spark came from a surprising place: bicycle racing. Hall described watching a finish-line camera that captured motion through a narrow slit, turning time into a crisp linear image. He realized the same trick could work for perception: collect distance measurements in a line, then sweep that line across the world to assemble a full picture.

Velodyne’s approach became a mechanical-electrical hybrid. Instead of one beam, it used a stack—16, 32, or 64 lasers—capturing range data simultaneously while a spinning housing swept those beams around the vehicle to create a 360-degree view in real time.

In 2007, Hall filed a patent for that design: 64 lasers in a rotating unit spinning at up to 900 revolutions per minute. It was a huge leap for autonomy. Suddenly, a machine could map its surroundings continuously without leaning so heavily on GPS. The catch was the price: the early sensor cost around $80,000. But in the DARPA world, it didn’t matter. It worked—and everyone noticed.

At the 2007 DARPA Urban Challenge, Velodyne’s system became the obstacle-detection workhorse. The Hall brothers sold their lidar as a steering input to five of the six teams that finished the race. The winning vehicle, Carnegie Mellon’s BOSS, used the HDL-64E.

Velodyne hadn’t just built a sensor. It had built the “eyes” of autonomy.

From Government Race to Commercial Gold Rush

Once the DARPA era proved what was possible, the 2010s turned it into a commercial obsession.

As autonomous vehicle programs exploded—first in research labs, then in Big Tech and well-funded startups—Velodyne became the default choice. Waymo, Uber, Apple: if you were running an AV test fleet, you probably had Velodyne units perched on top. Those spinning cylinders became the symbol of self-driving itself, showing up in endless demos, headlines, and investor decks.

In 2016, Velodyne’s lidar business was spun out from Velodyne Acoustics into Velodyne Lidar. The timing looked perfect. Autonomy was the hottest story in tech, and Velodyne owned the sensor that made the story believable.

But the same design that made Velodyne famous also carried a built-in ceiling.

Velodyne’s products were built on analog lidar—a mechanically complex system packed with discrete components. Each additional channel didn’t just add performance; it added parts: an emitter, a laser driver, a receiver, an analog-to-digital converter, and more. Going from 16 to 32 to 64 channels meant scaling complexity right along with resolution. That translated into expensive manufacturing, hard reliability problems at scale, and a dependence on mechanical motion that was difficult to escape.

The lidar gold rush was on. But a growing group of engineers believed the industry was mining the wrong deposit entirely.

One of them was a young engineer named Angus Pacala. At the time, he was working at a Velodyne competitor called Quanergy—and he was starting to form a conviction that would eventually define Ouster: if lidar was going to scale, it couldn’t be built like a precision instrument. It had to be built like silicon.

Ouster's Founding: The Digital Lidar Bet

The Stanford Engineer's Revelation

Angus Pacala came out of Stanford with exactly the kind of training you’d want for a hard hardware problem: mechanical engineering, then a master’s focused on mechatronics—the messy intersection where software meets motors, optics, and physics.

After school, he landed at Quanergy, one of the early lidar startups aiming to do the seemingly obvious thing: get rid of Velodyne’s spinning drum and build a solid-state sensor instead. Pacala rose to Director of Engineering, a role he held from late 2012 to early 2015.

And that’s where the unease set in.

From his vantage point, the industry felt trapped. Traditional analog lidar was an explosion of discrete parts and finicky mechanics—powerful, but expensive and hard to manufacture reliably at scale. Solid-state alternatives promised elegance, but they struggled to hit the performance autonomy demanded. Everyone was pushing, but it looked like they were pushing on the wrong things.

Pacala’s unlock didn’t come from automotive at all. It came from consumer electronics.

By 2015, vertical cavity surface emitting lasers, or VCSELs, and single photon avalanche diodes, or SPADs, were already being made by the millions. Smartphones and other mass-market devices were adopting them for depth sensing—Apple’s Face ID would later become the most famous example. These components were cheap, reliable, and, crucially, they lived on the kind of improvement curve that only consumer scale can buy.

Pacala later described the bet like this:

"What we saw back in 2015 was an opportunity to design a lidar sensor that could ride a wave of innovation in VCSEL and SPAD technology, combined with one of our key breakthroughs: new micro-optics that use light more efficiently, to build a high-resolution digital lidar that could meet customers' required specifications. The result of our work is a low-cost integrated digital lidar sensor. Because VSCELs and SPADs have improved in the intervening years, we have sensors today that are affordable, highly reliable, have the highest resolution available, are capable of 200+ meter range, and have many years of improvement ahead."

In other words: stop building lidar like a bespoke instrument. Build it like silicon. Put the complexity on chips. Let the broader semiconductor ecosystem do what it always does—drive cost down and capability up.

Building the Digital Lidar Architecture

Pacala co-founded Ouster in July 2015 and became CEO from day one.

The technical thesis was radical mostly because it was so clean: every Ouster sensor would be built on the same core “digital lidar” foundation, centered on a simple two-chip architecture. Where analog lidar could require hundreds to thousands of discrete components, Ouster wanted to replace that sprawl with semiconductor integration.

One piece of that foundation was a custom system-on-a-chip built around SPAD detectors. Ouster designed it in-house and had it manufactured in a standard silicon CMOS process. The chip produces a natively digital output—essentially ones and zeros indicating whether photons were detected—and it also runs the sensor’s logic and signal processing.

The other key piece was the light source: a VCSEL array. Compared to the edge-emitting lasers common in analog lidar, VCSELs offered practical advantages—smaller, lighter, faster, and more durable. But the bigger advantage was economic. You can pack many lasers into a dense array, and the cost doesn’t rise in a simple one-for-one way with every extra laser. On Ouster’s current sensors, that meant fitting 128 lasers into an area about the size of a grain of rice—high resolution in a compact package, with room to scale.

The dream, of course, is straightforward: if you can consolidate the critical functions of lidar into standard CMOS semiconductors, you can put lidar onto a fundamentally different price-performance curve than analog designs, or other approaches like MEMS or silicon photonics. It sounds inevitable.

It wasn’t. It was hard.

Ouster developed tightly integrated VCSELs and an ASIC incorporating SPAD arrays. As Pacala put it, "Ouster is the first company to commercialize a high performance SPAD and VCSEL approach."

And there was a third ingredient that made the whole thing viable: Ouster’s patented micro-optics, designed to use light more efficiently and push performance—especially range—beyond what VCSELs and SPADs could achieve on their own.

Early Years and Stealth Development

Ouster started quietly, raising seed funding and building in stealth. In December 2017, the company emerged with a $27 million Series A and its first commercial sensor, the OS1.

Those early years were about proving that “digital lidar” wasn’t just a nice architecture diagram. Plenty of skeptics argued that VCSELs couldn’t deliver the range needed for serious autonomy. And, in the beginning, that skepticism was warranted. In 2015, the state of detectors and lasers would have produced a sensor with a range of only a few meters. Over time, as the underlying components improved, so did the product. Eventually, the OS2 reached a range of over 200 meters—with the expectation of continued improvement.

This was the Moore’s Law thesis, applied to lidar: start with an approach that scales, even if the earliest versions aren’t perfect, because the curve is the point. If you’re on the right curve, you don’t have to win on day one. You have to win over time—while everyone else is stuck wrestling with parts counts, calibration, and mechanical constraints.

For investors, it looked less like a single sensor company and more like a platform bet. The question wasn’t whether Ouster’s first products were the best in the market. The question was whether the architecture would compound faster than the alternatives. In hardware, that difference is everything.

Growth and Product-Market Fit (2018-2020)

The Strategic Pivot Away from Automotive-Only

By the late 2010s, the lidar industry had developed a familiar rhythm: everyone pitched autonomous vehicles as the inevitable endgame, even as timelines kept slipping. The market was always “five years away.”

Ouster made a different call. Instead of building a company that lived or died on AV adoption, Pacala and team went looking for customers who needed lidar immediately—and would pay for it.

In 2019, Ouster raised another $60 million in a round led by Runway Growth Capital, with participation from Silicon Valley Bank, Cox Enterprises, Constellation Tech Ventures, Fontinalis Partners, and Carthona Capital. Around the same time, the company expanded internationally, opening offices in Paris, Shanghai, and Hong Kong.

Then the deployments started stacking up in places that didn’t look like the glossy AV demos everyone associated with lidar.

Ouster sensors showed up on Postmates’ Serve delivery robots rolling along Los Angeles sidewalks. Kodiak tested Ouster lidar on autonomous trucks in Texas. And in the 2019 DARPA Subterranean Challenge—something of a spiritual successor to the Grand Challenges that helped launch Velodyne—Ouster’s sensors were mounted on drones flying through the coal mines of Pennsylvania.

This wasn’t random experimentation. It was a strategy.

Pacala’s thesis was simple: autonomous vehicles might be the biggest prize, but they were also the most delayed. Meanwhile, robotics, mapping, mining, and industrial automation were real markets with real constraints—and they valued exactly what Ouster was trying to productize: reliability, consistent manufacturing quality, and a price-performance curve that got better over time.

The Second Generation Launch

In January 2020, Ouster put its “Moore’s Law for lidar” argument on the shelf for customers to pick up.

The company launched its second generation of sensors: three new 128-beam models that expanded the OS lineup and made a clear statement about where the platform was headed. OS0 targeted ultra-wide views for tight spaces like warehouses and dense urban environments. OS1 handled the mid-range use cases, with a range of about 120 meters and a 45-degree field of view. OS2 pushed into long-range sensing, reaching beyond 200 meters for higher-speed automation.

The market response was strong. Bookings jumped sharply year over year, and Ouster’s revenue trajectory started to look like the kind of curve that public-market investors chase.

The external validation was there, too. In 2019, Ouster was named a CES Innovation Awards Honoree for its OS-1-128, recognized for delivering high-resolution 3D imaging with 128 channels at a competitive price point. The sensor produced 2.62 million points per second—enough data density to unlock applications where “rough detection” wasn’t enough, and detailed mapping mattered.

But just as the business was finding its stride, the world shifted. COVID-19 disrupted supply chains and customer timelines. And in the markets, something else was forming: the SPAC boom—an accelerant that would turbocharge lidar ambitions, then punish them just as quickly.

The SPAC Era: Going Public in the Boom (2020-2021)

The Lidar SPAC Wave

Looking back, 2020 and 2021 barely feel real. Lidar had become the perfect SPAC narrative: a critical technology for a once-in-a-generation shift in transportation, huge potential markets, and just enough real deployments to make the future sound imminent. Company after company skipped the traditional IPO path and went public through special purpose acquisition companies, often at valuations that assumed autonomy was basically around the corner.

Velodyne kicked off the wave. On July 2, 2020, it merged with Graf Industrial Corp. and began trading as a public company. Then came the rest of the pack—Luminar, Innoviz, AEye, Aeva, and more—each pitching a slightly different sensor architecture, all selling the same underlying story: scale was close, and the ramp would be massive.

Ouster joined in March 2021, completing its merger with Colonnade Acquisition and listing on the New York Stock Exchange. It was perfect SPAC-era timing: enough momentum to command attention, enough ambition to justify big projections, and enough capital needs to make the public markets feel like the obvious next step.

For hardware-heavy companies that weren’t profitable and had long development cycles, the SPAC model had real appeal. Traditional IPOs demanded either profits or a clear path to them. Venture capital could fund R&D, but it wasn’t always built to carry expensive manufacturing and multiple generations of hardware all the way to scale. SPACs offered something different: quick access to large pools of capital, with valuations often tied more to forecasted revenue than demonstrated earnings.

The downside was embedded in the same mechanism. Those forecasts assumed autonomous vehicles would deploy at scale within a few years. As the realities of full autonomy became harder to ignore—and as the broader market environment shifted—those assumptions started to look less like confidence and more like wishful thinking.

The Sense Photonics Acquisition

Even as the SPAC machinery spun at full speed, Ouster kept building the business it wanted to be.

In October 2021, Ouster agreed to acquire Sense Photonics in an all-stock deal valued at around $68 million at the time. Sense brought solid-state flash lidar technology aimed squarely at automotive use cases—exactly the part of the market Ouster had strategically avoided betting the company on early, but still couldn’t ignore forever.

Once the deal was completed, Ouster created a new business arm, Ouster Automotive, led by Sense CEO Shauna McIntyre. The goal was clear: expand beyond Ouster’s core spinning digital lidar sensors and add capabilities tailored for automotive ADAS.

It was a classic move from the modern tech playbook: use newly liquid public stock as currency to buy complementary technology and a team that could accelerate your roadmap. The strategic logic was solid. The timing was the hard part. This was all happening as investor sentiment began shifting from “growth at any cost” toward a much less forgiving question: when does this become a real, sustainable business?

Velodyne's Unraveling

While Ouster was adding tools and building optionality, Velodyne—the company that had defined the category—was coming apart at the seams.

In January 2020, David Hall stepped down as CEO. Anand Gopalan, the former CTO, took over, while Hall initially stayed on as chairman and remained the company’s largest shareholder.

A year later, the conflict moved from behind the scenes to center stage. In January 2021, Velodyne removed Hall as chairman and terminated the employment of his wife, Marta Thoma Hall, amid a dispute in which both sides accused the other of misconduct.

Then, in November 2021, Velodyne replaced Gopalan with Theodore “Ted” Tewksbury, the former CEO of Eta Compute.

It was a stunning reversal. The founder who helped invent modern real-time 3D lidar for autonomous vehicles was now locked in open conflict with the company bearing his legacy. Stock prices fell. Leadership churn piled up. And the uncertainty wasn’t academic—every quarter spent fighting internally was a quarter not spent winning customers, improving manufacturing, or staying ahead of fast-moving competitors.

To public investors, it was a familiar cautionary tale: founding a company and running a public one are different jobs. Hall had built extraordinary technology. But Velodyne now needed stability, execution, and focus—exactly the things its governance crisis was draining away.

Inflection Point: The Velodyne Merger (2022-2023)

The Industry Reckoning

By late 2022, the lidar industry hit the part of the cycle where the story stops being about promise and starts being about survival.

The SPAC-era optimism had drained out of the market. Valuations cratered. Customer rollouts slipped. And an uncomfortable reality set in: there were far too many lidar companies chasing far too few dollars in the near term. Consolidation wasn’t a theory anymore. It was inevitable.

Ouster and Velodyne were both feeling the squeeze. Their stock prices had fallen hard, neither was profitable, and the cost of staying in the race—R&D, manufacturing, go-to-market—wasn’t getting cheaper.

Then came the cautionary tale everyone could understand. Quanergy, a lidar maker that had gone public via a SPAC just 10 months earlier at an implied $1.4 billion equity value, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. For the industry, it was a flashing warning light: this could go from “future of autonomy” to bankruptcy court in under a year. For Pacala personally, it was even sharper. Quanergy was where he’d learned, firsthand, how brutal the fundamentals of lidar manufacturing could be.

Against that backdrop, the deal that would reshape the category came together. In November 2022, Ouster and Velodyne announced they would merge in an all-stock transaction—an explicit bet that the only way forward was together.

The Deal Structure

The companies framed it as a merger of equals: shareholders on both sides would end up with roughly half of the combined company. And on February 10, 2023, the merger officially closed.

Leadership followed the same balance. Ouster CEO Angus Pacala would run the combined business. Velodyne CEO Ted Tewksbury would become chairman of the board.

The financial pitch was straightforward: scale the revenue base and cut the duplicated cost structure. When the deal was announced, the companies projected about $75 million in annual savings, expected to be realized within the first nine months after closing. Pacala suggested the savings could end up higher—but acknowledged the obvious tradeoff: getting there meant layoffs.

The combined company kept the Ouster name and continued trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker OUST. The ambition was to emerge with a broader customer footprint across automotive, industrial, robotics, and smart infrastructure, supported by deeper engineering and commercial teams—and then run the whole thing with a much leaner headcount, headquartered in San Francisco.

Opposition and Strategic Rationale

Not everyone at Velodyne saw the merger as clean or fair. Former chairman Michael Dee resigned from the board and publicly raised concerns about how the deal was structured, urging shareholders to think twice.

But in the end, shareholders approved it, and the logic that won the day was less about elegance and more about arithmetic.

Pacala told CNBC the merger was “a major step toward profitability for Ouster.” The key detail: gross margins. Ouster’s sensors had been selling for more than they cost to make for some time, and Pacala said Velodyne’s gross margins had turned positive as well after changes to its contract-manufacturing arrangements. In Pacala’s words: “This is huge for the merger and for the strength of the combined business. Not only are we increasing the revenue base of the two companies by merging, but it’s all positive margin.”

Layer on top of that a combined intellectual property portfolio built over more than 20 years of lidar innovation, plus the cost synergies, and the strategic bet comes into focus: this wasn’t just about getting bigger. It was about buying time and runway—enough to outlast the shakeout and make it to sustainable economics.

Pacala also made it clear this wasn’t simply an autonomous vehicle story. He told TechCrunch, “I keep saying this and people think I’m crazy, but there’s a good chance that smart infrastructure becomes our biggest vertical by a long shot in the next five years. The reason is because if you look at the established revenue base for traffic systems, for security systems, it’s immense. It’s way larger than the revenue generated from camera and radar companies in automotive.”

From a distance, the playbook was classic consolidation: combine complementary customer bases, eliminate duplicate costs, concentrate IP, and extend the runway to profitability. But investors knew the other side of the equation, too. Mergers come with integration risk, talent attrition, and inherited baggage. And in this case, there was a particularly sharp example of the last one: Velodyne’s prior patent settlement with Hesai—an agreement that could follow the combined company and complicate what came next.

That concern would prove timely.

The Hesai Patent War and Geopolitical Dimensions (2023-2024)

Filing the Lawsuit

Just two months after completing the Velodyne merger, Ouster went on the offensive against its most formidable competitor.

It filed a patent infringement complaint at the U.S. International Trade Commission against Hesai Group, the Shanghai-based lidar maker, and related entities. The request was for a Section 337 investigation under the Tariff Act of 1930—the kind of process that can end not just with damages, but with import bans. In parallel, Ouster also sued Hesai in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware, seeking an injunction and monetary damages.

The core allegation was straightforward and high-stakes: Hesai was unlawfully importing lidar sensors that infringed five patents Ouster said were valid and enforceable, covering lidar technology.

Ouster framed the dispute as a defense of American innovation. It said its patents reflected substantial U.S. investment across both rotating and non-rotating, solid-state lidar systems, and argued that after the market shifted toward Ouster’s digital lidar approach, Hesai copied patented technologies and embedded them into competing products.

And this wasn’t Hesai’s first brush with U.S. patent litigation. Back in 2019, Velodyne sued Hesai too. That case ended with Hesai settling—paying millions upfront and agreeing to ongoing royalties.

Zoom out, and the lawsuit was about more than a handful of patents. It sat at the intersection of three pressures hitting lidar all at once: brutal market competition, anxiety over intellectual property protection across borders, and escalating U.S.-China tension in strategically important technologies.

The Settlement Agreement Complication

But Ouster’s legal strategy ran into a problem that was, in a way, self-inflicted—created by the very merger that had just given the company scale and heft.

Hesai announced that the ITC had terminated the investigation Ouster had initiated. On October 10, 2023, the ITC Commissioners affirmed an initial determination from August 24, 2023 by the presiding Administrative Law Judge granting Hesai’s motion to terminate the ITC action.

Hesai’s argument was essentially: you can’t sue us like this, because your new combined company inherited Velodyne’s old commitments. Specifically, Hesai pointed to a patent cross-licensing and settlement agreement it had signed with Velodyne in 2020—years before Ouster and Velodyne merged in February 2023. In Hesai’s telling, that agreement bound the combined Ouster/Velodyne entity, and Ouster’s ITC filing violated it.

The Administrative Law Judge agreed—at least procedurally. The recommended termination was meant to give arbitrators time to decide whether Ouster was required to arbitrate based on that prior settlement agreement. Importantly, the initial determination wasn’t a ruling on the merits of Ouster’s patent claims. It was a ruling about process: whether Ouster could even bring the fight in this venue, given what Velodyne had already signed.

The irony was sharp. One of the biggest prizes of the merger was Velodyne’s long history of lidar IP. But Velodyne’s earlier settlement with Hesai—signed before Ouster had any say—now risked limiting what Ouster could do with that portfolio.

The Competitive and Geopolitical Dimensions

All of this was unfolding while the competitive landscape was shifting under everyone’s feet.

A Yole Group report, “Lidar for Automotive 2025,” noted that Hesai captured 33% of the global market by revenue in 2024. In the broader automotive lidar market, the report said Hesai led, followed by RoboSense, Huawei, and Seyond—four Chinese companies that together controlled 89% of the total market.

Passenger-car lidar demand was surging, driven largely by rapid ADAS adoption in China. And Hesai was scaling in a way that underscored how fast the market there was moving: in December 2024, the company said it became the first lidar maker to ship more than 100,000 units in a single month.

For Ouster, the implication was uncomfortable. Chinese competitors had reached scale in the world’s largest EV market, often with cost advantages from vertical integration and government support. Ouster’s route to winning looked narrower: dominate markets where Chinese suppliers faced restrictions, or build enough technological differentiation to justify premium pricing.

Then there was the geopolitical overlay. Hesai drew scrutiny from U.S. regulators and lawmakers concerned about Chinese-made technology being deployed in critical infrastructure. Ouster—and lobbyists aligned with it—were vocal about potential security risks from Chinese lidar. Hesai pushed back, emphasizing that its sensors don’t store data and that it had been certified for cybersecurity compliance.

For investors, the Hesai fight became a kind of prism: it showed how valuable patent portfolios can be, how messy mergers become when legacy agreements come along for the ride, and how geopolitics can simultaneously create opportunity and amplify risk. The dispute’s ultimate resolution remained pending, and with it, a lingering layer of uncertainty over how aggressively Ouster could compete—especially against the most scaled player in the market.

The Current State: Building Toward Profitability (2024-2025)

Financial Progress

By the end of 2024, Ouster was no longer talking like a company trying to survive the shakeout. It was talking like a company trying to win it.

The business showed real forward motion: fourth-quarter revenue rose meaningfully both year over year and quarter over quarter, and Ouster shipped thousands of sensors. Just as important, GAAP gross margin improved sharply versus both the prior year and the prior quarter—exactly the kind of metric that tells you whether a hardware company is climbing toward sustainability or sliding away from it.

Management leaned into that momentum on the year-end call:

"The fourth quarter capped off a year of consistent execution, record financial results, and delivering increased value for our customers. In 2024, we grew OS sensor volumes by over 50%, increased our software-attached bookings by over 60%, and deployed sensors at iconic events like the Paris Olympics. We also reached major milestones in the development of our next-generation custom silicon chips and new tools to accelerate lidar adoption."

The balance sheet added to the story. Ouster ended fiscal year 2024 with substantial cash reserves and no debt—rare oxygen in an industry where many competitors had been forced into desperate financings or worse.

Then, heading into 2025, the company pointed to continued execution in the first quarter:

"Our strong first quarter results demonstrate continued operational execution. We generated revenue of $33 million and gross margin of 41%, winning multimillion dollar deals across all four of our verticals."

If there was one operational achievement that mattered most here, it was margin. In lidar, it’s easy to ship impressive tech. It’s much harder to ship it profitably. Ouster’s improving gross margin was the clearest evidence yet that its digital architecture wasn’t just elegant—it could support a durable business.

Strategic Partnerships and Defense Applications

Those financial improvements weren’t happening in a vacuum. They were being pulled forward by wins that looked a lot like the strategy Pacala had been describing for years: diversify beyond robotaxis, and go where lidar solves expensive problems right now.

One of the biggest examples was mining. Ouster was selected as the lidar supplier for Komatsu’s suite of autonomous mining equipment offerings, signing a multimillion-dollar agreement to equip Komatsu machinery with Ouster’s 3D digital lidar sensors.

As Komatsu’s Matt Reiland, Technical Director, Automation Innovation, put it:

"Ouster's products developed through this partnership can withstand the shock, vibration and temperature constraints while delivering the enhanced range and spatial awareness necessary to operate in harsh mining environments,"

For Ouster, that’s the point of industrial autonomy: harsh environments, real budgets, and clear ROI. Mining doesn’t need a science-fair demo. It needs sensors that keep working.

And in 2025, Ouster landed a validation that carried a different kind of weight—literally national security weight. The company announced that its OS1 digital lidar had been vetted and approved by the Department of Defense for use in unmanned aerial systems. After a review of components and cybersecurity testing, the Defense Innovation Unit approved the OS1 and added it to the Blue UAS Framework—an approved list of interoperable, NDAA-compliant UAS components and software used to help the DOD rapidly vet and scale commercial drone technology.

Ouster emphasized the significance of that placement:

"The Ouster OS1 is the first high-resolution 3D lidar sensor approved under the Blue UAS Framework and offers superior performance in weight, power efficiency, and reliability under rugged conditions compared to previously approved 2D lidar solutions."

CTO Mark Frichtl tied it directly to supply chain and security—two themes that were becoming inseparable from the product itself:

"Ouster is committed to the responsible development of its products and has taken significant steps to secure its supply chain," said Ouster CTO Mark Frichtl. "As a result, our OS1 sensor was officially added to the Blue UAS list, providing drones and other UAS with access to industrial-grade, high-fidelity spatial awareness for advanced perception and autonomous operation. Ouster is proud to be the leading supplier of 3D lidar sensors for U.S. defense applications."

From an investor perspective, Blue UAS wasn’t just a badge. Defense-related deployments can come with higher-margin profiles, longer-lived customer relationships, and the possibility of multi-year procurement. And in a world where geopolitical tension was reshaping vendor choices, NDAA compliance gave Ouster a structural advantage in government and defense-adjacent markets—exactly where Chinese competitors could be constrained.

Technology Roadmap

Underneath the partnerships and margins, Ouster kept pushing the same long-term lever it bet the company on in 2015: silicon.

In the second quarter of 2024, Ouster taped out its automotive-grade custom silicon chip, Chronos. The company expected to integrate Chronos into its solid-state digital flash DF sensors in the following year. In parallel, development of its next-generation custom silicon, the L4 chip, continued, with validation testing underway. Ouster positioned both Chronos and L4 as key enablers—expanding into new verticals and improving performance, reliability, and manufacturability across the portfolio.

Chronos, in particular, was framed as an extension of Ouster’s core thesis: digital lidar should improve the way mass-market semiconductors improve—steadily, predictably, and with compounding benefits.

The company said Chronos would bring improved memory, dynamic range, and detection accuracy, and expected it to be the most powerful SPAD-based lidar chip produced to date.

And Ouster made the implication explicit. The next product cycle wasn’t just another incremental sensor refresh—it was positioned as a market expansion moment:

"The product portfolio transformation we have planned in 2025 will result in the largest increase in Ouster's addressable market in our history."

Bull and Bear Case Analysis

The Bull Case

Technology Moat Through Digital Architecture: Ouster’s core bet—digital lidar built around VCSELs and SPADs—looks increasingly validated. As its gross margins expanded, the company showed something that’s notoriously hard in hardware: the economics can actually improve over time. That’s the Moore’s Law-style flywheel Pacala talked about from the beginning. And because VCSEL and SPAD development is being pushed forward by massive players in consumer electronics, Ouster benefits from that broader innovation curve without having to fund all of it alone.

Diversified Revenue Base: While many lidar companies built their entire identity around autonomous vehicles, Ouster built a business where lidar already solves real problems. Industrial automation, robotics, and smart infrastructure aren’t as headline-grabbing as robotaxis, but they create demand today—and that diversification helps stabilize revenue while automotive timelines stretch.

Defense and Security Opportunity: Blue UAS approval doesn’t just add another vertical; it opens doors in a market where compliance requirements can function like a moat. NDAA alignment can make it harder for Chinese competitors to win certain contracts, and with the Pentagon pushing expansion programs for drones and unmanned systems, Ouster is positioned to supply a critical piece of the stack: perception.

Intellectual Property Portfolio: The combined Ouster-Velodyne footprint brings one of the stronger patent portfolios in the industry, built over decades of lidar innovation. In a category where differentiation is constantly under pressure, that IP can serve as both shield and sword—protecting product designs and potentially creating leverage through licensing.

Path to Profitability: The story Ouster is trying to tell the market is straightforward: grow revenue, expand gross margins, and keep operating expenses under control. With improving margins and ongoing cost discipline, the company argues it’s tracking toward profitability—one of the few outcomes that ultimately matters in a post-SPAC hardware landscape.

The Bear Case

Chinese Competition: In automotive lidar, the competitive reality is blunt. Hesai led with 33% market share, followed by RoboSense, Huawei, and Seyond—and together those four Chinese companies controlled 89% of the total market. They have scale, cost advantages, and deep traction in the world’s largest EV market. If that momentum carries into Western markets, Ouster could face punishing price pressure.

Autonomous Vehicle Timeline Risk: Even if Ouster has wisely diversified, the biggest long-term prize for lidar is still autonomy at scale. And that timeline keeps sliding. If full autonomy remains another decade away, Ouster must keep compounding in industrial and robotics markets that may be meaningful, but could be smaller than the autonomous endgame many investors once underwrote.

Technology Substitution Risk: Lidar’s role is still debated. Some autonomy developers—most notably Tesla—argue cameras alone can get to full self-driving. If that view wins, the top-end market for lidar shrinks. At the same time, 4D radar continues improving and could encroach on use cases where lidar is currently seen as the premium option.

Patent Litigation Uncertainty: The Hesai dispute highlights both the power and fragility of IP as a strategy. The outcome remains unresolved, and the earlier Velodyne settlement agreement showed how a merger can drag in legal constraints you didn’t design. Even with strong patents, enforcement is never guaranteed—and the forum matters as much as the claim.

Capital Intensity: This is still a hardware company. It needs ongoing investment in R&D, manufacturing, and inventory. Ouster’s balance sheet has been a strength, but sustained losses eventually force a choice: reach profitability, or raise more capital—potentially diluting shareholders.

Framework Analysis

Porter’s Five Forces: - Supplier Power: Moderate. VCSEL and SPAD supply comes from a relatively limited set of vendors, even if the components are becoming more standardized over time. - Buyer Power: High in automotive, where OEMs have enormous negotiating leverage; more moderate in industrial markets, where demand is fragmented across many customers. - Competitive Rivalry: Intense. The field includes multiple well-funded players, including Chinese competitors with scale advantages and government support. - Threat of Substitutes: Moderate. Cameras and radar can substitute in some applications, even if lidar provides capabilities that are hard to replicate. - Barriers to Entry: High. The category demands deep R&D, hard-won manufacturing expertise, and lengthy customer integration cycles.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers: - Scale Economies: Emerging, as sensor volumes rise and manufacturing efficiency improves. - Network Effects: Limited. There aren’t strong direct network effects, though a software ecosystem could create ecosystem pull and higher switching costs over time. - Counter-Positioning: Strong. Ouster’s digital approach is a clear counter-position to legacy analog architectures, and incumbents couldn’t easily pivot without walking away from prior technology and manufacturing bets. - Switching Costs: Moderate. Customers that integrate Ouster sensors often build workflows, software, and training around them. - Branding: Strengthening, especially in industrial and defense contexts where reliability and compliance matter. - Cornered Resource: Potentially the patent portfolio, though its real value depends on enforceability and the constraints created by prior agreements. - Process Power: Possible, if Ouster keeps turning manufacturing execution and supply chain discipline into a repeatable advantage rather than a one-time improvement.

Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re tracking Ouster from here, three KPIs matter most—and together they tell you whether this is becoming a durable hardware business or just a great demo with a shrinking runway.

1. Gross Margin Trajectory: This is the cleanest read on whether Ouster’s digital lidar thesis is actually compounding. Improving gross margin suggests the company is getting the manufacturing, pricing, and product mix right—and that it’s capturing the kind of Moore’s Law-style economics it’s been promising since day one. The key question now is whether margins hold up as volumes grow and competition pushes pricing: do they stabilize, keep expanding, or start compressing?

2. Revenue Growth Rate: Ouster has put a bold growth framework out in the open. Hitting it consistently would signal real market pull and staying power with customers. Missing it—especially repeatedly—would suggest either tougher competition, slower adoption in core verticals, or that the near-term market is simply smaller than the industry once assumed.

3. Book-to-Bill Ratio: This is your “demand versus delivery” gauge. When bookings run ahead of revenue, it usually means demand is building and backlog is forming—fuel for future quarters. When they don’t, it can be an early sign that customer urgency is fading, projects are getting delayed, or budgets are tightening.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

For investors, the next phase of Ouster’s story isn’t just about sensors and margins. It’s also about the rulebook—who can sell where, who can sue whom, and what happens when technology becomes a policy issue.

Several regulatory and legal threads matter most:

Hesai Litigation: The patent dispute with Hesai remained unresolved, and the range of outcomes was wide—from a negotiated settlement to a long, expensive court fight. The bigger wrinkle was structural: Velodyne’s prior settlement agreement introduced real uncertainty about how freely the combined Ouster could enforce parts of the inherited patent portfolio against Hesai.

NDAA Compliance: Ouster positioned itself as NDAA-compliant, a practical advantage in U.S. government and defense-adjacent markets. But it’s not a “set it and forget it” label. Maintaining compliance means continuous diligence around suppliers, components, and supply chain security—especially as parts availability and sourcing shift.

Export Controls: With U.S.-China tensions rising, export control regimes hung over the entire lidar category. Regulatory changes could cut both ways: they might restrict Chinese competitors and create openings for Ouster, or they could add new compliance burdens and limit how, where, and to whom Ouster could sell.

Autonomous Vehicle Regulations: Finally, even if the technology is ready, deployment still moves at the speed of regulators. Autonomous vehicle rollouts depended heavily on evolving rules across countries and states—and any acceleration or delay in those frameworks would flow directly through to lidar demand.

The Road Ahead

Ouster’s story still doesn’t have an ending. The company made it through the SPAC bubble, merged with the category’s original pioneer, and started to show what looks like a real path toward profitability. But the hard part of the movie is rarely the escape. It’s what happens after.

The center of gravity in lidar has moved, and it has moved toward China. Hesai and other Chinese manufacturers have reached a level of scale that U.S. and European competitors have struggled to match. Meanwhile, the biggest prize—the automotive lidar market tied to full autonomy—keeps drifting further into the future as “right around the corner” turns out to be much harder than the decks promised.

And yet Ouster isn’t walking into that fight empty-handed. It has a differentiated technical approach—digital lidar—with economics that have improved in the real world, not just on paper. It has revenue spread across multiple verticals instead of hinging everything on robotaxis. It has access to defense and government-adjacent markets where compliance and supply-chain constraints can matter as much as raw performance. And it has a deep patent portfolio that can be protective, and sometimes even offensive—if legacy agreements don’t blunt the edge.

So the investor question isn’t whether Ouster has advantages. It’s whether those advantages compound faster than the industry’s pressures grind them down. Digital architecture can be a structural edge in cost and performance improvement. But it only wins if the improvement curve stays steeper than what competitors achieve through scale, pricing power, and vertical integration.

Ouster’s thesis is basically a bet on silicon doing what silicon always does. By collapsing the complexity of traditional lidar into a digital, CMOS-based system-on-a-chip approach, the company believes it can keep getting better while getting cheaper—like processors and digital cameras did before it. If lidar really can ride that kind of curve, it stops being a luxury sensor reserved for a few high-end programs and starts looking like something that shows up everywhere.

That’s the wager: that digital lidar follows the same trajectory as digital cameras, and Ouster is the company positioned to ride that curve into leadership. It’s a classic technology-market bet—exponential improvement beating linear optimization.

For Angus Pacala and his team, going from walking away from Quanergy to ending up with Velodyne under the Ouster banner is a kind of validation. But markets don’t pay you for being right early. They pay you for building something durable.

Machines are learning to see. The only question left is whose eyes they’ll use.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music