Palo Alto Networks: The Platform That Ate Cybersecurity

I. Introduction & Cold Open

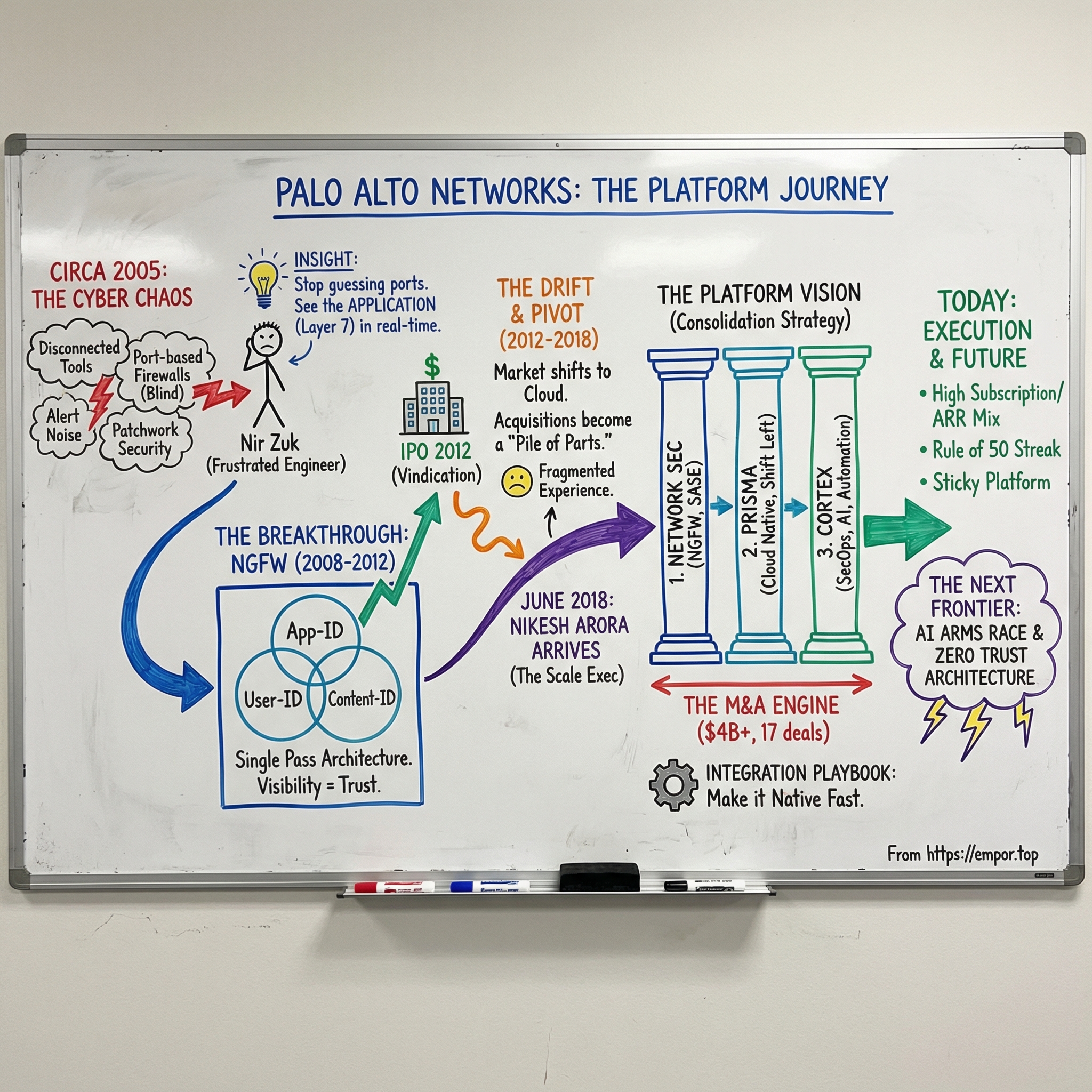

Silicon Valley, summer 2005. Cybersecurity is a mess of disconnected tools: firewalls that can’t tell Facebook from file transfer, intrusion systems that scream nonstop, and security teams buried under alerts they’ll never have time to chase. The industry is growing fast, but it’s growing sideways—more products, more dashboards, more noise.

Into that chaos steps Nir Zuk, a forty-year-old Israeli engineer with a point to prove and a clear belief that the whole category has drifted off course.

Zuk isn’t new to this fight. He was a founding engineer at Check Point, the company that defined the modern firewall. Later, he built what’s often credited as the first intrusion prevention system at OneSecure. But after Juniper Networks bought his second company and his roadmap got swallowed by bureaucracy, he decided he was done waiting for big-company permission.

His new plan was simple and a little heretical for the time: don’t just build another faster firewall box. Build a firewall that can actually see what’s happening on the network—what applications are running, who’s using them, and what data is moving—then enforce policy on that reality, not on outdated ports and protocols.

That sets up the hundred-billion-dollar question at the heart of Palo Alto Networks: how did a late entrant to a “mature” firewall market—one many people thought was already settled and commoditized—turn into the dominant platform in cybersecurity?

The answer is a mix of technical breakthroughs and relentless go-to-market execution. It’s also a story of consolidation: seventeen acquisitions totaling more than four billion dollars, stitched together into a broader vision. And it includes the arrival of a CEO who’d never worked in security at all, but understood platforms—and how to build them—better than almost anyone in Silicon Valley.

Today, Palo Alto Networks serves more than seventy thousand organizations across over one hundred fifty countries. Eighty-five of the Fortune 100 rely on it to protect their networks, their clouds, and the security operations that keep everything running. Its market cap has grown to sit among the largest pure-play security companies ever built, and its next-generation security annual recurring revenue has become one of the industry’s most watched scoreboards.

This is the story of how Palo Alto went from a scrappy challenger with a new kind of firewall to the platform that reshaped how enterprises buy, deploy, and think about security—and what that journey teaches about timing, technology shifts, and the brutal economics of building a category-defining suite.

II. The Nir Zuk Origin Story & Founding Context

In the early 1990s, inside Check Point’s offices in Ramat Gan, Israel, Nir Zuk was doing the kind of work that doesn’t look flashy in the moment, but ends up shaping an entire industry. Check Point had pioneered the stateful inspection firewall—technology that looked at the context of network traffic, not just raw packets, and decided what belonged inside a corporate network and what didn’t. Zuk helped write the code behind it. And as the product spread through enterprises, his fingerprints spread with it.

People who worked with him came away with the same two impressions: he was exceptionally good, and he was exceptionally sure of it. That combination would fuel nearly everything that came next.

Zuk, born in 1971, had served in Israel’s Unit 8200, the country’s elite signals intelligence group and a kind of unofficial farm system for cybersecurity founders. That experience wired in a specific mindset: security isn’t a checklist, it’s a contest. Attackers adapt. Defenders have to adapt faster. Many security companies would build for compliance and stability; Zuk would build for adversaries.

At Check Point, he rose quickly—becoming the company’s fifth employee and one of its most productive engineers. But by the late 1990s, he thought Check Point was drifting. In his view, it had become too comfortable shipping incremental updates instead of rethinking the architecture for what the internet was becoming. When he pushed for more ambitious technical moves, he ran into organizational drag and risk aversion.

So in 1999, he left and started OneSecure, built on a simple but inconvenient observation: firewalls were good at blocking known bad traffic, but they weren’t built to catch new attack behavior as it happened. What the market needed was real-time inspection that could identify intrusion attempts by behavior, not just by matching signatures. That idea became the intrusion prevention system—IPS.

OneSecure gained traction quickly enough that NetScreen Technologies, then a fast-growing firewall rival to Check Point, acquired it in 2002. For Zuk, this looked like the opening he’d been waiting for: a chance to marry firewalling and intrusion prevention into one cohesive system instead of a pile of disconnected appliances. He stayed on and pushed hard to integrate IPS into NetScreen’s firewall products—one box, one view, one policy brain.

Then in 2004, Juniper Networks bought NetScreen for four billion dollars, and the ground shifted under his feet. Juniper was a networking company first. Security wasn’t the center of gravity. Zuk watched the focus drift toward hardware economics and router-adjacent strategy. His push for deeper security innovation—and especially his early next-generation firewall concept, a firewall that understood traffic at the application layer instead of just ports and protocols—didn’t find much oxygen.

He resigned, frustrated but not defeated. If the companies he’d joined couldn’t—or wouldn’t—build what he thought was obvious, he’d build it himself.

And the timing was perfect, in the worst way.

Cybersecurity in 2005 was a patchwork. Enterprises might run a firewall from Check Point or Cisco, intrusion detection from ISS or Sourcefire, web filtering from Websense, VPN gear from someone else entirely. Each came with its own console, its own alert stream, its own philosophy. Security teams weren’t defending so much as refereeing a chaotic stack of tools.

Worse, the underlying assumptions were breaking. Applications learned to hide inside web traffic. Skype, BitTorrent, and a growing swarm of other programs tunneled through port 80—the same port used by ordinary browsing—making traditional firewalls effectively blind. Personal devices were showing up on corporate networks. Early cloud services were starting to pull data and workflows outside the neat, defendable perimeter that firewalls were designed around.

Zuk’s thinking crystallized into three big convictions.

First: the network security market wasn’t going away. Threats were getting more sophisticated, regulations were multiplying, and companies were becoming more dependent on software and connectivity every year.

Second: virtualization was going to reshape how applications ran and where they lived. Security would have to follow workloads, not just guard a static edge.

Third: software would beat hardware. The winners would be the companies that could ship new capabilities in software quickly, not the ones protecting margins on boxes.

With that, he incorporated Palo Alto Networks in 2005 and began pulling together a founding team—engineers who shared the same frustration with where security had ended up, including people he’d worked with at NetScreen and Check Point. The company set up in Santa Clara. And yes, the geography carried some intention: Zuk wanted to build close to the ecosystem he came from, and close to the incumbents he now believed were vulnerable.

But conviction doesn’t fund a company.

The early years were rough. Investors in 2005 and 2006 were cautious about security after a run of underwhelming outcomes. And Zuk’s reputation didn’t make the pitch easier. Even supporters would describe him as technically brilliant and relentlessly demanding—a perfectionist with little patience for bad thinking. Plenty of investors passed, pointing to a “crowded firewall market” and worrying about whether this was just another box in a category that already felt mature.

The investors who leaned in saw something else. The next-generation firewall wasn’t a faster firewall. It was a different firewall. Traditional products looked at ports and protocols; Zuk wanted to identify the actual application no matter what port it used, tie traffic to real users instead of just IP addresses, and inspect content in real time for threats. It was the unified, application-aware security brain he’d been trying to build for years—now rebuilt from scratch, on purpose.

Greylock Partners led Palo Alto Networks’ Series A in 2005. Sequoia Capital and other top firms followed. They weren’t just betting on a product idea—they were betting that Zuk’s stubbornness, the same trait that made him hard to work with, was exactly what it would take to out-innovate entrenched incumbents.

Now the hard part began: turning a dense, ambitious architecture into a product enterprises would actually trust at the center of their networks.

III. Building the Next-Generation Firewall (2005-2012)

Palo Alto Networks spent its first three years doing something almost old-fashioned: building in silence. In an industry where “stealth mode” often means fundraising plus a lot of buzzwords, Zuk and his team stayed quiet because they weren’t ready to talk. They were trying to make something work.

When the PA-4000 series shipped in 2008, it wasn’t a prototype or a promise. It was a deployable next-generation firewall—something you could rack in a data center and put in the line of fire on day one.

The breakthrough was architectural. Traditional firewalls made decisions at layers three and four of the OSI model, using IP addresses and port numbers as their worldview. Port 80? Must be web traffic. Port 443? Must be encrypted web traffic. That logic held when applications behaved themselves and stayed in their lanes.

By 2008, applications had stopped playing by those rules. Skype could slip through almost any open port. BitTorrent could dress up like ordinary HTTP. Malware could talk to command-and-control servers over encrypted sessions that looked, from the outside, a lot like normal banking traffic. In that world, the classic firewall wasn’t really “security” anymore. It was closer to a speed bump.

Palo Alto flipped the model by pushing inspection up to layer seven—the application layer. Instead of guessing based on ports, the firewall looked at the traffic itself and identified applications by behavior. It sounds obvious now, but it was brutally hard to do at real network speeds. Deep inspection at wire speed demanded custom silicon, highly optimized software, and a set of design choices that prioritized performance without giving up accuracy.

They named the core capability App-ID, and it became the foundation of everything that came next. Security teams could finally write policies in plain language: block BitTorrent; allow Salesforce but log all access. And the visibility was often uncomfortable. Companies deploying Palo Alto firewalls routinely found hundreds of applications running inside their networks that no one had known—or admitted—were there.

Then came User-ID, which tied that traffic to real people. By integrating with Active Directory and other identity systems, Palo Alto could tell you not just that some internal IP was behaving oddly, but that a specific employee was doing it. “John in accounting is using a file-sharing app to move documents” is a very different conversation than “10.1.1.47 is connecting to something weird.”

Content-ID completed the trio, layering in threat prevention, URL filtering, and data loss prevention on the same traffic stream. Instead of stacking separate appliances and consoles, the firewall could identify malware, block malicious sites, and prevent sensitive data from leaving the network—consolidated into a single device.

Palo Alto’s go-to-market was just as intentional as the product. Enterprise security was a relationship business, dominated by incumbents like Check Point and Cisco. This wasn’t a market you won by checking feature boxes. You won by showing CISOs something they couldn’t unsee.

So Palo Alto popularized a move that became famous in the industry: the visibility assessment. A salesperson would offer to drop a Palo Alto firewall into a prospect’s network for a few days, free, in monitoring mode. It wouldn’t block anything. It would just watch. Then they’d come back with a report: every application in use, every user reaching for cloud services, and every suspicious connection the existing defenses had missed.

The results were often jarring. Companies that believed they had tight control discovered unauthorized cloud storage, shadow IT systems talking to the outside world, and sometimes active malware infections that had been sitting there undetected. The assessment didn’t just sell a firewall. It created urgency—because it turned a vague fear (“we should probably upgrade security”) into a concrete, network-specific problem (“this is what’s happening inside your walls right now”).

By 2011, the momentum was visible from the outside. Gartner included Palo Alto Networks in its Magic Quadrant for enterprise network firewalls—and put it in the Leaders quadrant despite how young the company was. Against Check Point, Cisco, and Juniper, that was a major signal to buyers who used Gartner as a kind of permission slip to consider a new vendor.

Revenue grew quickly, though Palo Alto stayed private and kept details tight. What did surface suggested a classic hockey-stick: from essentially nothing when the product shipped to real enterprise scale just a few years later. More importantly, the customer list started to include the hardest logos to win—large enterprises, government agencies, and financial institutions with zero patience for security theater.

In early 2012, the IPO window cracked open, and Palo Alto ran through it. On July 20, 2012, the company debuted on the New York Stock Exchange, raising $260 million and landing as the fourth-largest tech IPO of the year. The offering priced above the expected range, and when trading opened the stock jumped—ending the first day up 42 percent. By the close, Palo Alto was valued at nearly $3 billion.

For Zuk, it was vindication. The “mature” firewall market that so many investors had shrugged off had produced one of the most successful security IPOs in years. And for Check Point—the company he helped build, then left in frustration—the message was sharper: this wasn’t just another competitor.

The next-generation firewall wasn’t merely a product. It was the start of a new security control plane—one that, over time, would reach far beyond the network edge.

IV. The Platform Vision Takes Shape (2012-2018)

The IPO glow didn’t last long before Palo Alto ran into a harder truth: even if you won the firewall market, the firewall market was starting to move out from under you. Workloads were drifting into the cloud. Employees were bringing their own devices and working from everywhere. And attackers were getting good at slipping past anything that relied too heavily on known signatures.

Palo Alto’s leadership could see where this was headed. If the company stayed “just” a network firewall vendor—even the best one—it risked becoming less central to how security got done. The question was how to expand without losing the thing that made Palo Alto special in the first place.

From 2014 through 2017, the company started reaching outward with a string of smaller acquisitions: technology for behavioral analytics, malware sandboxing, and endpoint protection. These weren’t massive, headline-grabbing deals, and none of them delivered an immediate step-change in growth.

The issue wasn’t that the products were bad. The issue was that they didn’t feel like Palo Alto.

The next-generation firewall had earned its reputation by behaving like one system: App-ID, User-ID, and Content-ID working together in a single control plane. The acquired products, by contrast, arrived as separate tools with separate consoles and only partial ties back to the firewall. Customers could see the ambition, but many hesitated to go all-in. It looked less like a platform and more like a growing pile of parts.

Still, one deal in that stretch mattered more than it looked at the time. In 2017, Palo Alto acquired LightCyber for $105 million. LightCyber focused on behavioral analytics—using machine learning to flag unusual activity that might signal a breach, especially the kind that slips past traditional prevention. It fit naturally alongside the firewall’s strengths. And just as importantly, it brought in a team steeped in machine learning, a capability that would become increasingly valuable as Palo Alto pushed into new categories.

At the same time, Palo Alto was building another asset that couldn’t be bought off a shelf: credibility. The company stood up Unit 42, its threat intelligence and research group, to investigate active attacks, track threat actors, and publish detailed write-ups that security teams actually trusted. Unit 42’s reporting on nation-state operations, ransomware campaigns, and new techniques helped Palo Alto become something more than a vendor with a good product. It became a source of signal in a noisy industry.

In 2014, Palo Alto also joined Fortinet, McAfee, and NortonLifeLock to form the Cyber Threat Alliance, a consortium designed to share threat intelligence. On the surface, it was a “rising tide lifts all boats” move. Strategically, it also did something else: it put Palo Alto on the same stage as the biggest names in security, reinforcing that it belonged in the top tier.

Financially, the company kept growing—strongly. Revenue climbed from roughly $600 million in fiscal 2014 to more than $2 billion by fiscal 2018. That’s a huge run. But it wasn’t yet the kind of transformation that turns a category leader into a category-defining platform. Palo Alto was dominating firewall deals, but its broader suite still felt like a work in progress.

What it needed was a leader who understood platforms as a craft—someone who had watched world-class tech companies evolve from one killer product into an ecosystem, and who knew how to use acquisitions to build something coherent rather than crowded.

That person arrived in June 2018.

His name was Nikesh Arora.

V. The Nikesh Arora Era & Transformation (2018-Present)

Nikesh Arora was an unusual pick to run a cybersecurity company. He wasn’t a career security operator or a lifelong product technologist. He was, first and foremost, a scale executive.

Born in Ghaziabad, India, Arora followed a path that mixed engineering, business, and finance: an engineering degree from the Indian Institute of Technology, an MBA from Northeastern University, and a finance degree from Boston College. He worked across Deutsche Bank, Putnam Investments, and T-Mobile before joining Google in 2004.

At Google, he rose to chief business officer, helping build the partnerships and sales engine behind the company’s advertising business and its international expansion. During his time there, Google grew from roughly $3 billion in annual revenue to more than $75 billion. Arora understood how distribution becomes a moat—and how platforms compound once they get leverage.

In 2014, he left for SoftBank as president and COO, working alongside Masayoshi Son on major technology investments. It was a crash course in tech at every altitude: startups, scale-ups, and giants, across markets around the world. When he departed SoftBank in 2016 amid succession questions, his reputation only got sharper: one of the most capable executives in Silicon Valley who still hadn’t taken the top job.

Palo Alto’s board went after him hard. The company had a dominant position in next-generation firewalls and a growing presence beyond them, but it still didn’t feel like a single, integrated platform. Nir Zuk remained CTO and the company’s technical north star, but the next chapter required an operator—someone who could turn ambition into an execution machine. In June 2018, Arora joined as chairman and CEO.

He moved fast. Arora laid out the organizing idea that would define Palo Alto’s strategy for the next several years: cybersecurity would consolidate, and Palo Alto would be the consolidator—built around three integrated platforms.

Network security would stay the foundation. Cloud security would protect workloads across AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud. Security operations would unify detection, investigation, and response across everything.

Then he started buying the missing pieces.

In March 2018, just before Arora officially took over, Palo Alto acquired Evident.io for $300 million. Evident specialized in cloud security posture management—finding misconfigurations and policy violations in cloud accounts. It became the nucleus of what would be branded Prisma Cloud.

In February 2019 came Demisto for $560 million. Demisto was a SOAR company—security orchestration, automation, and response—and it was built for a reality every security team recognized: too many tools, too many alerts, and not enough humans. Demisto automated repetitive workflows and coordinated actions across products, turning incident response from improvisation into something closer to an assembly line. Inside Palo Alto, it became Cortex XSOAR, a cornerstone of the security operations platform.

A few months later, Palo Alto added Twistlock for $410 million and acquired PureSec. Twistlock focused on container security as enterprises moved to Docker and Kubernetes. PureSec targeted serverless security for services like AWS Lambda. With Evident.io already in hand, Palo Alto suddenly had credible coverage across the modern cloud stack.

And Arora kept the tempo.

RedLock joined for $173 million. Zingbox, an IoT security company, came for $75 million. Aporeto, focused on microsegmentation, cost $150 million. CloudGenix—an SD-WAN leader—was acquired for $420 million.

Individually, these could look like a shopping spree. The point was the framework. Under Arora, every deal had a place to land.

Network security broadened beyond the firewall into SD-WAN, SASE, and cloud-optimized next-generation firewalls. Prisma Cloud expanded into workload protection, container and serverless security, infrastructure-as-code scanning, and API security. Cortex combined SOAR, XDR, threat intelligence, and attack surface management into a single security operations story.

The biggest swing came in late 2020: Expanse. Palo Alto announced it would buy the company for $800 million, later increased to $1.25 billion. Expanse had pioneered attack surface management—continuously scanning the internet to map an organization’s exposed assets and vulnerabilities. Strategically, it gave Palo Alto something it didn’t have before: an outside-in view of risk, complementing the inside-out visibility coming from firewalls and endpoint agents.

By the end of 2021, Arora had spent more than $4 billion on seventeen companies. The integration task was enormous. Every acquisition brought its own stack, its own culture, and its own customers. Some products clicked into place quickly; others took years of engineering work to approach the seamless experience Palo Alto was selling.

But the bet was straightforward: Palo Alto already had tens of thousands of firewall customers. If it could actually integrate these capabilities into platforms—and sell them as platforms—it could turn a product beachhead into a broader control plane for enterprise security.

That’s what started to happen. Firewall customers began adopting Prisma Cloud and Cortex. Spend per customer rose as organizations consolidated point solutions into fewer, more integrated systems. Growth reaccelerated, and the business mix shifted further toward subscription and support revenue.

The numbers reflected the momentum. Fiscal 2022 revenue reached $5.5 billion, up 29% year over year. Fiscal 2023 rose to $6.9 billion, another 25% increase. The company also hit its “Rule of 50” metric—revenue growth plus free cash flow margin above 50%—for five consecutive years, an outcome that’s rare at Palo Alto’s scale.

By this point, the identity had changed. Palo Alto Networks was no longer a firewall company that also sold other security tools. It was a cybersecurity platform—one that just happened to have started with the firewall.

VI. The M&A Machine & Integration Playbook

Seventeen acquisitions in less than five years would strain almost any company. For Palo Alto Networks, that pace created a knife-edge tradeoff: the chance to assemble a portfolio no competitor could easily match, and the risk that a messy mash-up of products would frustrate customers and erase the value of the deals.

So Palo Alto built a repeatable acquisition and integration system, and it got sharper over time.

The first rule was strategic fit. Every deal had to land cleanly inside one of the three platforms. Internally, the team kept a capability map that tracked what they already had, what customers were asking for, where attackers were heading, and where competitors were getting strong. Potential targets weren’t judged only on whether the tech was exciting, but on whether it filled a specific gap and could become part of the larger whole.

The second rule was keeping the builders. Security acquisitions often fail for a simple reason: the people who understand the product best leave. Palo Alto tried to prevent that with earnouts and retention packages designed to keep key talent engaged for three to four years after closing. Demisto became the template. When the team came over, the founders stayed on to lead what became Cortex XSOAR, preserving momentum in both product direction and customer trust.

The third rule was making the product feel native—fast. Palo Alto pushed acquisitions toward shared building blocks: common authentication, unified policy frameworks, and centralized management. The objective was straightforward: within roughly eighteen to twenty-four months, customers shouldn’t feel like they were operating another standalone tool with another console. It should feel like Palo Alto.

Expanse showed both how hard that could be and why it mattered. Its attack surface management was powerful, but it arrived with its own data models and interface, built as an independent product. Turning Expanse into something that worked naturally with Cortex XSOAR—so an exposed asset could trigger an automated investigation and response—took real engineering effort.

When it worked, it created the kind of “platform moment” Arora had been promising. A security team could spot an exposed server through Expanse, connect it to firewall traffic, check for vulnerabilities through Prisma Cloud, and kick off remediation through Cortex—without stitching together a half-dozen vendors. That end-to-end workflow, as an integrated experience, was the point.

Of course, not every deal landed perfectly. Some technologies were harder to absorb than expected. Some teams struggled to adapt to Palo Alto’s culture and processes. A few products were eventually deprecated or repositioned as the market shifted and their original value became less central. Those misses weren’t free—but they did tighten the company’s diligence and integration playbook.

The newer acquisitions followed the same pattern: add a capability that was becoming essential, then make it part of the platforms customers were already buying. Bridgecrew expanded into infrastructure-as-code security, catching issues before cloud resources were ever deployed. Cider Security added software supply chain protection as attackers moved upstream into the development pipeline. Dig Security brought data security posture management to reach deeper into the data layer. Talon Cyber Security added enterprise browser technology, rounding out the secure access service edge vision.

Over time, the sum of all this became its own advantage. Palo Alto wasn’t just buying companies; it was building an engine that could find the right teams, move quickly, and fold them into distribution at scale. For founders, that meant a clear path from great technology to global impact. In a market full of potential buyers, that made Palo Alto an unusually compelling home.

For customers, the promise was even simpler: the platform kept expanding with the threat landscape. When a new category surged—supply chain attacks, cloud misconfiguration, data posture—Palo Alto could add credible coverage through acquisition instead of waiting years to build from scratch.

The question, for investors and customers alike, was how long the engine could run at full throttle. Integration debt builds when deals land faster than engineering can fully absorb them. And as Palo Alto gets bigger, it becomes harder to find acquisitions that materially move the company. Leadership argued the market was still large enough to keep expanding—but over time, the tempo would inevitably slow.

And that set up the next part of the story: whether all this consolidation translated into durable financial performance—and a defensible position in a security market where giants and specialists were both coming for the same budgets.

VII. Financial Performance & Market Position

Under Arora, Palo Alto’s financial story stopped being “fast-growing firewall leader” and became something closer to “security infrastructure company.” When he arrived in 2018, the business did about $2.2 billion in annual revenue. By fiscal 2025, ending in July 2025, that figure had reached $9.2 billion—an expansion that’s hard to pull off at enterprise scale, and even harder in a market where customers are constantly tempted by shiny point solutions.

The more important shift, though, wasn’t just how much Palo Alto sold—it was what it sold. Over these years, the company methodically pushed its revenue mix toward subscriptions and support: stickier, more predictable, and generally higher margin than one-time product sales. In fiscal 2025, subscription and support made up the vast majority of billings. Next-generation security ARR reached $5.6 billion, growing 32% year over year even on a much larger base. That’s the platform thesis showing up in the math: once the firewall relationship is in place, Palo Alto can land more of the security stack over time.

Investors also started watching a metric that matters a lot for this kind of business: remaining performance obligation—contracted revenue that hasn’t hit the income statement yet. By the end of fiscal 2025, RPO stood at $15.8 billion, up 24% from the prior year. In plain terms, customers were not just renewing. They were committing, signing longer deals, and effectively pre-ordering years of Palo Alto’s platform.

Profitability improved right alongside the growth. Palo Alto posted consistent non-GAAP operating margins above 20% while still spending heavily on R&D and on the sales force required to sell large, multi-product enterprise agreements. Free cash flow stayed strong, helping fund acquisitions and support share repurchases that reduced the dilution impact of equity compensation.

All of this played out against a competitive landscape that got more intense, not less. Check Point—the original firewall king and the company Zuk helped build—lost ground as Palo Alto kept taking big enterprise wins. Fortinet remained a real force, especially in the mid-market, with a model that leaned into hardware economics and aggressive pricing. Cisco, while enormous, continued to struggle with what customers increasingly demanded: fewer tools that actually feel like one system.

Then there’s the modern generation of security contenders—companies born cloud-first, not appliance-first. CrowdStrike became a powerhouse in endpoint security and a direct rival to Cortex XDR. Zscaler defined cloud-delivered security and went head-to-head with Palo Alto’s SASE push. Wiz emerged as a breakout cloud security company, attracting valuations that signaled it could become a serious challenger to Prisma Cloud.

And looming over everyone is Microsoft. Microsoft’s advantage is structural: it owns the operating system, the identity layer, and a huge and growing cloud platform, which lets it bundle security into existing licenses and make “good enough” the default option for many buyers. Palo Alto’s answer has been consistent: large enterprises don’t live in a single-vendor world, and security can’t be strongest where it’s most convenient. They argue the winning solution has to work across heterogeneous environments—multiple clouds, mixed endpoints, and sprawling networks—without being tied to any one ecosystem.

As performance improved, valuation followed. Palo Alto’s stock rose multiple times from its IPO level, with the volatility you’d expect from a growth company operating through turbulent market cycles. It traded at levels that looked expensive by old-school standards, but reflected a newer bet: that Palo Alto wasn’t just winning categories—it was steadily absorbing them.

That’s what makes the “Rule of 50” streak so important. For five consecutive years, Palo Alto managed to keep its combined revenue growth rate and free cash flow margin above 50%. It’s a shorthand for something rare: growing fast without burning the business down to do it. Maintaining that balance is harder as a company gets bigger, the market gets noisier, and competitors get richer.

But if Palo Alto’s platform strategy was real, this was exactly how it would look: larger contracts, longer commitments, expanding share of wallet, and profitability that held up even as the company kept investing to stay ahead.

VIII. Technology Evolution & AI Revolution

By the time Palo Alto’s platform strategy clicked, the technology underneath it had already undergone its own quiet reinvention. The company started with a box in the data center—specialized hardware running innovative software. It evolved into something closer to a cloud-delivered system, where machine learning and automation sit in the critical path of detection and response.

In 2020, Palo Alto introduced what it described as the first machine learning-powered next-generation firewall. The point of the claim wasn’t marketing flair. It was a shift in philosophy: move beyond defenses that depend on humans writing signatures and rules after the fact, and instead catch threats the system has never seen before. That matters most in the ugliest category of all—zero-day attacks—where there is no signature to match because the vulnerability and exploit are new.

Old-school detection is inherently reactive. Analysts obtain a malware sample, reverse engineer it, extract identifying traits, publish a signature, and then customers finally get protection. Even when that process is fast, there’s still a window where the threat spreads.

Machine learning aims to shrink that window. Instead of waiting for a known “fingerprint,” models can flag suspicious behavior patterns as they happen and stop them before they become an incident that needs cleanup.

Of course, security isn’t like image recognition or autocomplete. The adversary learns. Attackers probe what gets blocked, then iterate until it doesn’t. A model that’s brilliant against yesterday’s techniques can look naïve against tomorrow’s. Palo Alto’s answer was to treat ML as a living system: continuously retraining models and feeding them fresh signals from its global footprint so protections could update across customer deployments as threats evolved.

This is where the platform architecture starts to matter. Palo Alto’s three pillars—network security, cloud security (Prisma), and security operations (Cortex)—each contain plenty of individual products. The promise, though, is that they don’t behave like a pile. They share data, they share context, and they can act together.

Picture a modern attack chain. It starts with a phishing email. A user clicks. Malware lands on an endpoint. The attacker moves laterally through internal systems, looking for credentials and high-value data. Then the data gets pushed out—often to something that looks legitimate, like a mainstream cloud storage service.

If you only see one slice of that story—just endpoint activity, or just network traffic—each step can look almost normal. The real signal shows up when you connect the dots.

Palo Alto’s platform is designed to do that correlation. Cortex XDR pulls telemetry across endpoints, network sensors, and cloud environments, then uses analytics and machine learning to spot patterns that match real attack behavior. When something crosses the line, Cortex XSOAR is there to take action automatically: isolate the endpoint, block the outbound connection, kick off response workflows, and generate the ticket trail analysts need. Prisma Cloud watches for suspicious behavior and risky conditions in cloud environments. And the network firewalls can cut off command-and-control traffic that would otherwise keep the intrusion alive.

Then generative AI arrived and turned the temperature up again.

On the upside, it created a new kind of leverage for defenders. Palo Alto began weaving AI into the experience of running security: letting analysts ask questions in natural language instead of writing complex queries, summarizing noisy alert storms into clearer narratives, and using automation to reduce the human effort it takes to investigate and respond.

On the downside, attackers got the same tools. Phishing got harder to spot because it no longer needed broken English or obvious tells. AI could produce more convincing lures at scale. And it could help churn out malware variants faster than traditional signature pipelines can keep up. The industry moved into a more explicit arms race: both sides using AI, both sides accelerating.

Alongside that shift, Zero Trust became a core architectural theme. The old model—trust what’s inside the corporate network and scrutinize what’s outside—collapsed as the perimeter dissolved. Cloud workloads, mobile devices, and work-from-anywhere didn’t just blur the boundary; they made it irrelevant.

Zero Trust flips the assumption. Trust nothing by default. Verify every request. Decide access based on identity, device health, and context—not on whether something happens to be “on the network.” Palo Alto pushed Zero Trust across its platforms by tying together user identification, behavioral analytics, and adaptive access controls that can enforce policy consistently across networks, clouds, and users.

The deeper change here is philosophical: security is shifting from being geography-based—where are you connecting from?—to identity-based—who are you, what are you trying to do, and should this system allow it right now? Palo Alto’s early obsession with knowing the real application and the real user ended up being more than a firewall feature. It was a down payment on how the rest of enterprise security would need to work.

IX. Playbook: Strategic Lessons

Palo Alto Networks’ rise—from an upstart firewall company to a cybersecurity platform—offers a playbook that travels well beyond security. Strip away the acronyms and the breach headlines, and what you’re left with is a set of decisions that show up again and again in enterprise software: where to focus, when to expand, how to buy, and how to keep the whole thing from collapsing under its own weight.

The first lesson is about platform strategy. Palo Alto didn’t start life with a grand “platform” manifesto. It started with a single product thesis: build a firewall that could actually understand what was happening on a network. The platform came later, as customer reality caught up: security teams were drowning in point tools, and they were tired of stitching together visibility, policy, and response across systems that didn’t talk to each other. Palo Alto’s advantage was recognizing when the market had shifted from “best product wins” to “best integrated system wins,” and then pushing hard into consolidation before everyone else could.

Platforms work when they remove complexity for customers while quietly raising the cost of switching. Palo Alto’s three-platform model does both. Customers get a more unified view of risk and a simpler operational workflow. Meanwhile, the deeper they deploy—across network, cloud, and SecOps—the more their day-to-day security processes start to run through Palo Alto’s management layer, integrations, and data. At that point, replacing one component isn’t just swapping a tool. It’s rewiring how security gets done.

The second lesson is the build-versus-buy call. Palo Alto’s biggest breakthroughs were built: the original next-generation firewall and the App-ID foundation behind it. But the threat landscape kept widening faster than any internal roadmap could cover. So the company used acquisitions to fill gaps, bring in teams with hard-won expertise, and compress time-to-market in categories that were becoming urgent.

The difference is that Palo Alto treated acquisition as the beginning of the work, not the end. Enterprise software history is packed with deals that “made sense” on paper and then failed in practice because the products stayed fragmented. Palo Alto’s approach—clear landing zones inside the platforms, retention of key builders, and a push toward shared infrastructure—was how it bought aggressively without letting the portfolio become a junk drawer.

The third lesson is about technical debt—especially the kind you inherit. Every software company accumulates debt. It ships fast, makes tradeoffs, and later pays the price in complexity. Palo Alto felt that pressure even more acutely because acquisitions arrive with their own architectures, assumptions, and tooling. Left unmanaged, that becomes a tax on every future feature and every customer deployment.

The answer wasn’t glamorous, but it was decisive: invest in the connective tissue. Shared authentication, unified policy frameworks, consistent APIs, common management experiences. Customers rarely cheer for that work explicitly, but it’s what makes a platform feel like a platform instead of a bundle of logos.

The fourth lesson is timing. Palo Alto won early because Nir Zuk bet on application-layer inspection before incumbents fully accepted that ports and protocols were no longer enough—and he delivered a working product while competitors were still debating the premise. Later, the company made similarly important timing bets around cloud security as enterprise workloads moved off-premises.

In technology markets, timing is often the real differentiator. Arrive too early, and you spend years educating customers who aren’t feeling the pain yet. Arrive too late, and you’re fighting entrenched vendors with budgets, references, and distribution. Palo Alto’s edge has been a repeated ability to step into transitions while they’re still forming—and then execute fast enough to define what “good” looks like.

The fifth lesson is how moats actually form in cybersecurity. They’re rarely permanent, and they’re almost never based on a single feature. They come from stacked advantages: better telemetry from a large footprint, stronger threat intelligence from broader exposure, trust built through research and incident response credibility, switching costs created by integration, and the sheer R&D capacity that comes with scale.

Palo Alto built moats across those dimensions. Unit 42 strengthened credibility and improved intelligence. The platform increased switching costs by connecting products into workflows. Scale made it possible to keep investing even as the product surface area expanded. Over time, those advantages compound—and that compounding is what makes a leader hard to dislodge.

The final lesson is the balance between growth and profitability. Palo Alto spent aggressively—on R&D, on go-to-market, and on acquisitions—without treating profitability as an optional someday goal. The company’s Rule of 50 streak became the shorthand for that discipline: it managed to keep investing for expansion while still generating meaningful cash.

That balance doesn’t happen by accident. It requires tradeoffs—saying no to growth that’s too expensive, insisting that acquisitions fit both strategically and financially, and building a model that can scale without breaking. Palo Alto’s story shows that in enterprise software, the best long-term outcome isn’t growth at any cost. It’s growth that makes the business stronger as it gets bigger.

X. Bear Case vs. Bull Case

Any honest assessment of Palo Alto Networks has to hold two ideas at once: this is one of the best-positioned companies in cybersecurity, and it’s also running a strategy that leaves very little room for mistakes.

The bear case starts with the most obvious risk: integration. Seventeen acquisitions don’t just add features—they add codebases, product philosophies, sales motions, and cultures. Even with a disciplined playbook, that’s a lot of moving parts to keep aligned. Some technologies won’t age as well as expected. Some integrations will take longer than planned. Some key builders will leave, retention packages or not. And as the portfolio expands, the danger isn’t merely that products don’t connect—it’s that the organization slows down under its own complexity right when the threat landscape demands speed.

Then there’s competition, especially from cloud-native specialists. Wiz has been growing explosively in cloud security with a product that many customers perceive as simpler and more focused than Prisma Cloud’s broad platform. CrowdStrike has shown how far a company can go with relentless execution in endpoint security, putting real pressure on Cortex XDR. If Palo Alto gets bogged down in platform integration while these players keep shipping quickly, the incremental growth at the edge of the market can drift away.

The hyperscalers are a different kind of threat—structural, not tactical. Microsoft, Amazon, and Google can bundle security capabilities into the platforms customers already use. For organizations that standardize heavily on one cloud, “native” tools can feel good enough, and they’re certainly convenient. Microsoft’s security business has been growing fast enough to make this concern feel concrete, not theoretical.

There’s also the risk that “platform” becomes synonymous with “too much.” Palo Alto’s pitch is that consolidation simplifies operations. But deploying and running three interlocking platforms across dozens of products still takes expertise, time, and change management. Some customers may decide that, for their particular environment, best-of-breed point solutions are easier to adopt and easier to master—even if that brings back the very tool sprawl Palo Alto is trying to eliminate.

Finally, valuation is its own form of risk. Palo Alto is priced like a company that can keep growing strongly while expanding margins. If growth slows—because the market saturates, competition intensifies, or execution gets choppy—multiples can compress quickly. And the stock has shown it can be volatile when markets get nervous.

The bull case is the mirror image: Palo Alto is positioned to benefit from the most important buyer behavior shift in the industry—consolidation. Cybersecurity spend is massive and historically fragmented across hundreds of vendors. CISOs have learned the hard way that fragmentation creates blind spots, integration costs, and operational drag. Palo Alto’s claim is simple: fewer tools, better connected, with a real shot at improving outcomes. And among the companies attempting that, Palo Alto has one of the broadest platforms and the clearest track record of pulling pieces together at scale.

The strongest proof point is next-generation security annual recurring revenue. Growing at 32%, it signals that the future products—Prisma Cloud and the Cortex suite—are not just theoretical add-ons to a firewall base. Customers are buying them, renewing them, and expanding with them. That’s what you want to see if the platform thesis is real: adoption beyond the original beachhead.

The business model also helps. Subscriptions and long-term contracts create visibility that point-product businesses often struggle to match. Remaining performance obligations of $15.8 billion represent committed future revenue—business that competitors would have to pry away deal by deal, over years, while Palo Alto is still shipping and still bundling value across the platform.

AI could deepen the moat. Palo Alto’s scale—more than seventy thousand customers—means a huge flow of telemetry and threat signals. That data can feed machine learning systems in a way smaller competitors can’t easily replicate. If better models lead to better outcomes, and better outcomes attract more customers, you get a compounding loop: scale improves detection, and improved detection reinforces scale.

And then there’s the simplest enterprise reality of all: switching costs. The deeper a customer goes—network security, cloud security, and SecOps—the more Palo Alto becomes embedded in workflows, playbooks, integrations, and team training. Replacing that isn’t just a procurement decision. It’s an organizational rewrite. Most enterprises avoid that unless the pain is unbearable.

If you want a framework view, traditional competitive analysis points to why Palo Alto has held up so well. Buyer power is meaningful but limited at the high end: large enterprises can negotiate, but there aren’t many vendors that can credibly cover this much surface area. Supplier power is low because the platform is primarily software. New entrants face steep barriers—data, distribution, and R&D investment. Rivalry is intense, but increasingly concentrated among a small set of heavyweights.

And on the “durable advantage” side, Palo Alto has several forms of compounding power: scale-based threat intelligence, switching costs from integration, economies of scale in R&D, and process advantages from a repeatable M&A engine.

Going forward, the simplest scorecard is the one Palo Alto itself has trained the market to watch. Next-generation security ARR growth tells you whether customers are buying into the platform beyond firewalls. Remaining performance obligation growth tells you whether customers are committing to that platform for the long haul. If both stay strong, the bull case stays intact. If they wobble, the bear case has somewhere real to land.

XI. The Future of Cybersecurity

The cybersecurity world Palo Alto Networks will face over the next decade barely resembles the one it entered in 2005. The threats are more professional, the attack surface is vastly larger, and the tooling on both sides has been reshaped by AI. Security is no longer just “protect the perimeter.” It’s “protect everything, everywhere, all at once”—and do it faster than humans can reasonably keep up.

That’s where the AI arms race turns from buzzword to reality.

Attackers are already using large language models to write more believable phishing emails, automate reconnaissance, and generate malware variants designed to slip past yesterday’s detection. Defenders can’t answer that with more analysts staring at more dashboards. They need systems that can spot patterns at machine speed, connect signals across network, cloud, identity, and endpoint, and then act—automatically—before an incident becomes a business outage.

Palo Alto has a real advantage here: scale. It sees massive amounts of telemetry, and that data can make models smarter over time. But it’s not an unassailable lead. AI capabilities are moving quickly across the industry, and strong competitors can narrow the gap. The winners won’t just be the companies with impressive models; they’ll be the ones that can operationalize them across messy, real enterprise environments. That tends to favor platform vendors, because they’re the ones already sitting across enough of the surface area to collect context and execute responses.

At the same time, cloud-native transformation keeps changing what “security” even means.

Enterprises aren’t simply migrating old workloads into AWS or Azure. They’re rebuilding applications around containers, serverless, infrastructure-as-code, and continuous deployment. Those shifts create security problems that don’t map cleanly to traditional tools—because the environment is dynamic, ephemeral, and defined by code. Prisma Cloud has expanded to cover these modern architectures, but the pace of cloud innovation guarantees that the goalposts will keep moving. New services, new abstractions, and new developer workflows will keep creating new categories of risk.

Another shift that’s becoming unavoidable is the convergence of IT operations and security operations. For decades, they were separate tribes with separate tools, and the seams between them became the weak points—misconfigurations, delayed patching, ownership confusion, slow incident response. The modern model pushes security into the operational fabric of the company: DevSecOps, automated remediation, and policy-as-code. That’s exactly the direction Palo Alto’s platform strategy is designed for, but making it real requires more than product breadth. It requires workflows that work, across teams that don’t naturally share incentives.

Then there’s the macro backdrop: geopolitics and regulation.

Nation-state attackers aren’t just targeting governments. They’re targeting critical infrastructure, intellectual property, and the supply chains that modern economies run on. The line between financially motivated crime and state-sponsored campaigns keeps getting blurrier, and many enterprises now have to defend against adversaries with budgets, patience, and sophistication that dwarf traditional cybercriminals. That reality supports demand for high-end security platforms even when other IT spending gets squeezed.

Regulation adds another layer. Privacy regimes like GDPR and CCPA, plus industry-specific standards in healthcare, financial services, and critical infrastructure, keep raising the minimum bar for security controls. Compliance doesn’t guarantee safety, but it does create a spending floor. Even in downturns, many organizations can delay projects—just not the ones that keep them out of trouble.

So what does “winning” look like for Palo Alto five to ten years from now?

It looks like being the default security control plane for large enterprises—network, cloud, and security operations—where customers don’t just buy products from Palo Alto, they run their security program through Palo Alto. It looks like AI that doesn’t merely generate better alerts, but meaningfully reduces the time and labor required to prevent and contain real attacks. And it looks like the company continuing to add new capabilities—whether built or acquired—without the platform collapsing under its own complexity.

Because the counter-scenario is also plausible. Complexity can become a tax. Cloud-native competitors can keep winning the incremental workloads. Hyperscalers can keep bundling security until large chunks of the market accept “good enough” as the default. In that world, Palo Alto doesn’t lose overnight—it just loses the right to be the center.

The next chapter comes down to execution: integrating what it has bought, shipping AI that creates measurable customer value, and sustaining the innovation velocity that got the company here in the first place.

XII. Outro & Final Thoughts

Palo Alto Networks is, at its core, a story about platforms—and about showing up at the exact moment a market’s old assumptions stop working.

Nir Zuk saw that the “mature” firewall category wasn’t actually mature at all. It was stuck. Incumbents were defending a worldview built on ports and protocols while the internet was busy rewriting the rules. Palo Alto won early not by polishing what already existed, but by changing what a firewall could be: a system that could see applications, users, and content clearly enough that customers could prove the difference inside their own networks. That obsession with visibility and control—and a culture that demanded technical excellence—created a wedge strong enough to crack open a market people thought was already settled.

Nikesh Arora saw the next problem: winning firewalls wasn’t the same thing as winning security. As cloud, endpoints, and SecOps became where breaches lived and died, Palo Alto needed to become more than a product company. Arora pushed the platform thesis, built around network security, cloud security, and security operations—and then moved at a pace few large companies can match. The acquisition strategy wasn’t random; it was a way to assemble a full-stack security footprint faster than competitors could build, while keeping enough financial discipline to fund the journey and maintain investor confidence.

If you build enterprise software, the transferable lessons are clear. “Mature” markets often hide opportunities for architectural reinvention. Integration can be a product in itself—and when it’s done well, it creates switching costs that no single point solution can replicate. M&A can compress time, but only if you treat integration as the real work, not the closing dinner. And timing is everything: arrive too early and you’ll preach to an empty church; arrive too late and the distribution advantage is already gone.

Cybersecurity, meanwhile, isn’t going anywhere. As long as organizations run on digital systems, adversaries will keep finding new ways in—and defenders will keep needing infrastructure that can adapt. Palo Alto has made its bet: that the future belongs to platforms that can cover the whole attack surface and turn mountains of telemetry into action.

Whether it holds that position will depend on what always decides the winners in security: shipping fast enough to keep up with the threat, integrating well enough to stay coherent, and staying valuable enough that enterprises keep choosing the platform over the pile.

XIII. Recent News

In February 2025, Palo Alto Networks reported a strong fiscal second quarter. Revenue came in at $2.289 billion, up 15% year over year. Next-generation security annual recurring revenue reached $4.8 billion, growing 28% from the prior year. Management raised full-year guidance, signaling confidence that customers were continuing to adopt more of the platform, not just renew the core.

Deal-making continued too. In late 2024 and early 2025, Palo Alto announced additional acquisitions aimed at expanding its cloud security footprint and building out AI-related capabilities. Meanwhile, the less glamorous work—absorbing what it had already bought—kept moving. Integration of prior deals, including Talon Cyber Security’s enterprise browser technology, stayed on the timeline the company had laid out.

The competitive pressure didn’t ease. CrowdStrike’s continued expansion and acquisition activity, plus Wiz’s rapid growth in cloud security, put real heat on key segments. Microsoft’s security business kept gaining as enterprises leaned into bundled, “already in the license” security tools. Palo Alto’s response was consistent with its strategy: lean harder into integration as a differentiator, and keep accelerating AI features that make the platform more operationally useful, not just broader.

And then there’s the spending backdrop, which remained uneven. Some enterprises stretched out procurement cycles and took a harder look at vendor consolidation and renewals. Others maintained—or even increased—security budgets, treating cybersecurity less like discretionary IT spend and more like business continuity. Palo Alto’s reliance on multi-year contracts helped smooth some of that volatility, giving it a degree of insulation even when buyers slowed down around the edges.

XIV. Links & Resources

Company Materials - Palo Alto Networks annual report and SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, 8-K) - Investor Relations presentations and earnings call transcripts - Unit 42 threat research publications

Industry Analysis - Gartner Magic Quadrant for Network Firewalls - Gartner Magic Quadrant for Cloud-Native Application Protection Platforms - Forrester Wave reports on security platforms

Acquisition Documentation - SEC filings tied to major acquisitions (including Demisto, Expanse, and Bridgecrew) - Palo Alto Networks integration case studies and post-acquisition materials

Technical Resources - Palo Alto Networks documentation on next-generation firewall architecture - Zero Trust implementation guides - Prisma Cloud and Cortex platform technical overviews

Leadership Insights - Nikesh Arora interviews on platform strategy - Nir Zuk presentations on the evolution of security architecture - Keynotes from Palo Alto Networks Ignite events

Market Context - Cybersecurity Ventures market sizing reports - McKinsey and BCG research on enterprise security spending trends - Venture capital reporting on cybersecurity startup activity

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music