PNC Financial Services: From Pittsburgh Trust to National Banking Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

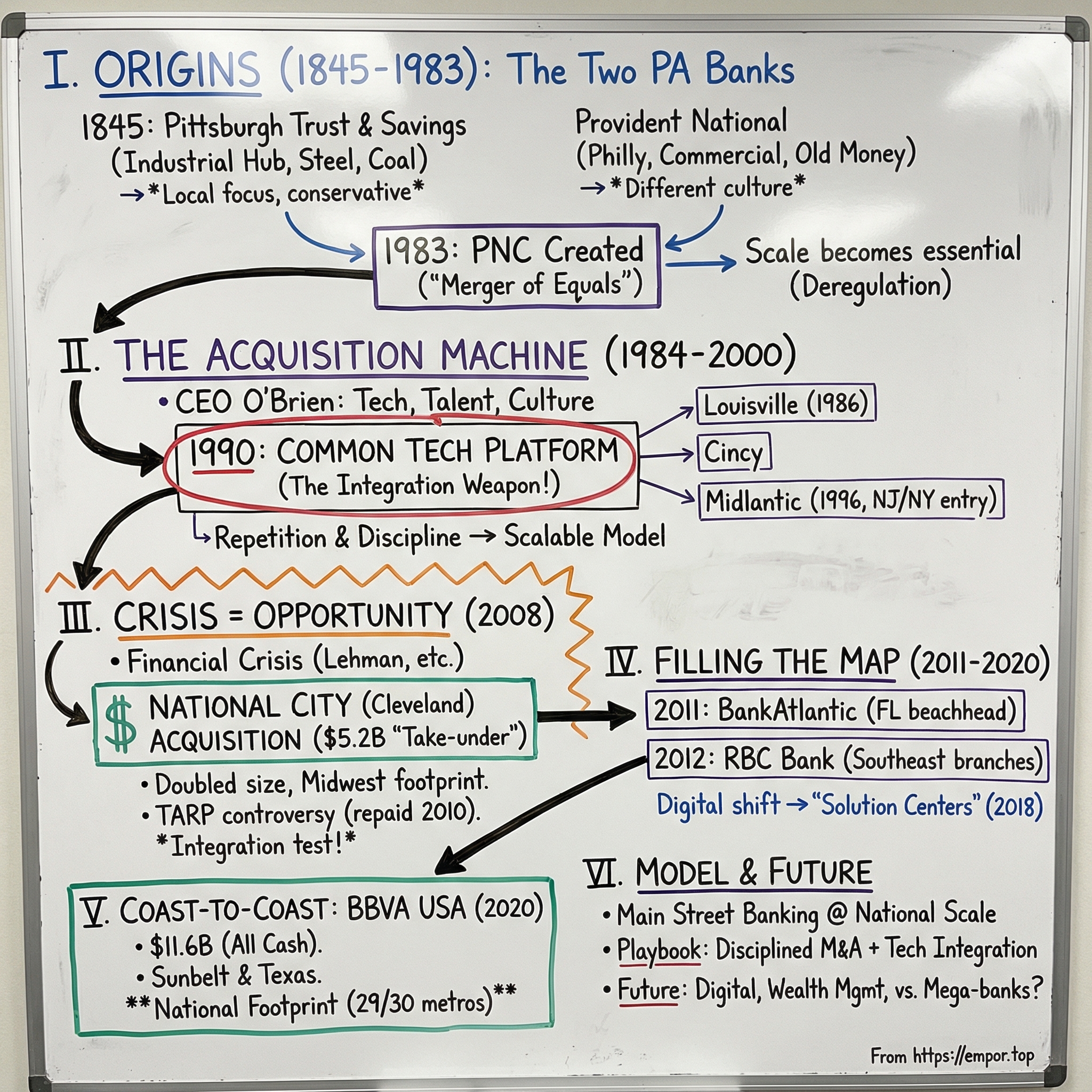

Picture the steel-gray skyline of Pittsburgh in the early 1980s. The city was still reeling from the slow collapse of its industrial base—mills dimming, jobs vanishing, confidence draining out of the region. But inside the boardrooms of two old-line Pennsylvania banks, the mood was different. Executives weren’t mourning the past; they were designing an escape plan. What came out of those rooms would become one of the most disciplined acquisition engines in modern American banking.

Today, PNC Financial Services is America’s fifth-largest bank, with more than $560 billion in assets. It operates across 27 states and the District of Columbia, with 2,629 branches and 9,523 ATMs. That kind of footprint can look inevitable in hindsight—like the natural end state of a successful company.

It wasn’t.

PNC’s national scale was built, deal by deal, through decades of patient consolidation. The core question of this story is simple: how does a bank that began as a Pittsburgh trust company turn into a coast-to-coast financial franchise? The answer is a playbook that’s almost boring in its consistency, and that’s exactly why it worked: be clear about what you’re buying, wait until the timing is right, integrate fast, and don’t overpay.

Over more than forty acquisitions, PNC’s leaders refined that formula into muscle memory. They built scale without abandoning underwriting discipline—an advantage that matters most when the world stops making sense. And PNC had a knack for choosing its moments. In 2008, when the financial system was in free fall, it stepped in and bought National City Corporation. More than a decade later, amid the post-pandemic consolidation wave, it did it again with BBVA USA.

This is a story about strategic patience—and about knowing when patience should end. It includes controversy, including a bruising TARP-era backlash. It includes hard integration decisions and the messy reality of overlapping markets. And it includes something rarer than a big bank getting bigger: a repeatable method for doing it without blowing itself up.

By the end, what you’ll have isn’t just the arc of a banking giant. You’ll have a template for any serial acquirer: how to compound advantages through M&A, how to make technology integration a weapon, how to absorb cultures without losing your own—and how to play offense when everyone else is forced to play defense.

II. Origins & The Two Pennsylvania Banks

The year was 1845. James K. Polk had just taken office as the eleventh President. The Mexican–American War was still a threat on the horizon. And in Pittsburgh—a city already humming with industrial ambition—a group of businessmen signed papers to create the Pittsburgh Trust and Savings Company on April 10.

They were planting a seed for a financial institution that would one day span the country. They just didn’t get the chance to water it.

Pittsburgh in those days was a tinderbox: dense wooden buildings, coal smoke, constant motion. And almost immediately, the city reminded everyone who was really in charge. A massive fire tore through downtown, consuming more than a thousand buildings across 56 acres and leaving the commercial district in ruins. The trust company technically existed—but it didn’t have a functioning place, or a functioning city, to do business in.

It took nearly seven years to recover enough to truly begin. On January 28, 1852, Pittsburgh Trust and Savings finally opened its doors to customers. It’s an almost too-perfect origin story for what PNC would become later: a bank that, again and again, found its moments when things were falling apart around it.

Pennsylvania, meanwhile, was turning into the engine room of American industrialization. Pittsburgh sat at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers—three waterways that made it a natural shipping and trading hub for the interior of the country. Coal from nearby hills powered furnaces and forges. Rail lines spread out like arteries. And all of it—steel mills, railroads, merchants, builders—needed capital.

That demand made banks less like “nice-to-have” businesses and more like essential infrastructure. Manufacturers needed working capital. Railroads needed construction loans. Merchants needed credit to buy and sell across long distances. As Pittsburgh rose, its banks rose with it, financing the industries that would turn the city into shorthand for American steel—and that would make titans like Andrew Carnegie possible.

But PNC’s story was never just Pittsburgh’s.

On the other side of the state, Philadelphia’s financial world grew from a different soil. It was older, more established—shaped by commerce, shipping, and a long-standing money culture that went back to colonial days. The institutions there served a different kind of economy, and they developed different instincts. In 1957, Provident Trust Company and Provident Tradesmens Bank and Trust Company merged to form Provident National Corporation, creating a major force in eastern Pennsylvania.

If you know anything about Pennsylvania, you know the Pittsburgh–Philadelphia rivalry isn’t a footnote. It’s cultural. It’s identity. Pittsburgh was industrial, brash, built fast. Philadelphia was commercial, traditional, built early. Their banks carried that same DNA—different clients, different strengths, different ways of seeing risk and opportunity. And in a twist that would matter decades later, those differences made them a better match than either would have wanted to admit.

You can see the beginnings of a shared philosophy in the 1930s. While banks around the country failed in waves during the Great Depression, Pittsburgh’s major institutions leaned into a more conservative approach. First National Bank of Pittsburgh partnered with Peoples-Pittsburgh Trust Company to finance municipal improvements, keeping money moving when the economy wanted to freeze. It wasn’t charity. It was self-preservation with a civic edge: banks don’t outlast their communities.

By the 1970s, the Pittsburgh and Philadelphia franchises—Pittsburgh National Corporation and Provident National Corporation—had become serious regional powers. But they were boxed in by the rules of the era. Pennsylvania banking law kept operations local, limiting banks largely to their home county and neighboring counties. The regulations were designed to prevent concentration. They also prevented scale—the very thing banking would soon start to demand.

Then the winds began to change. Deregulation was coming. Consolidation was no longer a scary hypothetical; it was the obvious future. The question for these two banks wasn’t whether they’d need a partner. It was whether they’d pick the right one—and whether they’d move before someone else forced their hand.

The stage was set for a merger that would remake Pennsylvania banking, and eventually, reshape PNC into something much bigger than a hometown institution.

III. The Historic 1983 Merger: Birth of PNC

The Garn–St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 hit American banking like a rules change in the middle of the game. For decades, Depression-era restrictions had kept banks small and local. Now the walls were coming down. In Pennsylvania, the old limits that boxed banks into their home counties and a few neighbors suddenly mattered a lot less. Scale wasn’t optional anymore—it was survival.

Inside the boardrooms of Pittsburgh National Corporation and Provident National Corporation, the implications were obvious. If they stayed separate, they risked becoming targets—picked off by a larger rival that could move faster and spread costs across a bigger footprint. If they combined, they could be the consolidator instead of the consolidated.

That’s easy to say. It’s harder when the two institutions come from cities that have spent a century competing for pride, talent, and business. Pittsburgh and Philadelphia didn’t just have different markets; they had different instincts. The negotiations had to bridge that rivalry, align two sets of executives, and reassure two separate customer bases that the new thing would be better than the old ones.

The strategic fit, though, was real. Pittsburgh National brought deep ties to western Pennsylvania and the industrial economy—hard-nosed lending experience and long relationships with manufacturers. Provident National anchored the east, with strong commercial banking in the Philadelphia metro area and complementary asset management capabilities. Together, they would cover the state in a way neither could alone.

In 1983, they made it official. The deal created an institution with $10.3 billion in assets—at the time, the largest bank merger in American history. It was a statement that a new era had arrived, and Pennsylvania wasn’t going to watch it happen from the sidelines.

Even the name was part of the message. Instead of one brand swallowing the other, the combined company took the shared initials of the two holding companies and became PNC Financial Corporation. It wasn’t just a compromise. It was a signal: this was meant to be a merger of equals, with both legacies carried forward into something bigger.

Of course, “merger of equals” is also code for “hard to integrate.” Leadership roles had to be sorted out. Reporting lines clarified. Two technology stacks—two ways of doing everything—needed to be untangled. And then there was the human side: people who had spent their careers competing were suddenly expected to collaborate, and middle management had to figure out where they fit in the new order. In banking, where trust and continuity are the product, even small disruptions can feel existential to customers.

PNC’s early years were defined by working through those frictions without breaking the franchise. Integration moved forward, but not recklessly. The emphasis was on getting it right—building a platform that could hold together—because the leadership understood a painful truth: a merger can create a bigger bank on paper while quietly destroying value in the branches and back office.

Most importantly, the founding deal taught PNC what it would need to become good at. The merger crystallized the principles that would define the next few decades: focus on geographic fit, insist on a clear strategic rationale, and maintain valuation discipline. In other words, growth was welcome—but only on terms that made sense.

By the mid-1980s, the new PNC had found its footing. The Pittsburgh–Philadelphia combination had proven the concept. Deregulation was still pushing the industry toward consolidation, and the landscape around PNC was full of smaller, fragmented banks. With its new scale—and a fresh set of lessons learned the hard way—PNC was ready to stop thinking like a Pennsylvania institution and start acting like an acquirer.

IV. The Acquisition Machine: 1984–2000

By the mid-1980s, PNC was no longer trying to prove the Pittsburgh–Philadelphia marriage could work. It was trying to turn that merger into a growth engine.

In 1985, Thomas H. O’Brien took over as CEO. At 48, he was the youngest chief executive of any major U.S. bank—an unmistakable signal that PNC wanted a faster tempo. O’Brien had lived through the 1983 merger from the inside. He’d seen the value it created, and he’d felt the pain of stitching two banks into one. Now he had the mandate to apply those lessons again and again, but on purpose.

O’Brien’s view of banking was simple and surprisingly modern: technology, talent, and culture decide who wins. Technology let you scale a consistent product. Talent built relationships that actually lasted. Culture—especially credit culture—kept you from chasing the kind of growth that looks great right up until it detonates.

His first big test arrived in 1986, when PNC bought Citizens Fidelity Corporation of Louisville, Kentucky. It was PNC’s first out-of-state acquisition, the kind of move that would’ve been unthinkable under the old regulatory regime. Louisville gave PNC a foothold in a growing market, along with a deposit base and commercial lending franchise that fit neatly with what it already knew how to do.

But the bigger takeaway wasn’t Louisville itself—it was what Louisville taught them. Every new market came with its own competitive realities and its own customer expectations. What worked in Pittsburgh didn’t automatically translate to Kentucky. So PNC started to separate what must be standardized from what should stay local. Risk management, compliance, and core operations had to be uniform. But branches, client relationships, and market-level nuance couldn’t be bulldozed without consequences.

Then came more deals, each one extending the map a little farther. Central Bancorporation of Cincinnati pushed PNC deeper into the Ohio Valley. Bank of Delaware Corporation added a small state, but a strategically placed one. None of these were splashy on their own. That was the point. PNC was learning to acquire the way a great operator learns to build: with repetition, with discipline, and with fewer surprises every time.

The most important move of the era, though, wasn’t a purchase. It was a decision.

In 1990, PNC committed to moving off its patchwork of legacy systems and onto a single common technology platform. For a bank, that’s the kind of project everyone agrees is necessary—right up until it’s time to write the check and accept the operational risk. It was expensive. It was disruptive. And it carried the terrifying possibility that something fundamental—transactions, accounts, trust—could break.

PNC did it anyway.

O’Brien and his team weren’t chasing “modernization” for its own sake. They were building an integration weapon. A common platform meant consistent products across markets, lower costs as the footprint grew, and—crucially—a repeatable conversion process for every bank PNC would buy next. Instead of accumulating systems like scar tissue, PNC planned to absorb acquisitions into one operating model, over and over, getting better with each conversion.

That decision compounded. It made future deals easier, faster, and cheaper to integrate. And it made PNC’s acquisition strategy more scalable than many peers who kept postponing the painful work of technology consolidation.

With that backbone in place, the 1990s became a steady march. Between 1991 and 1996, PNC bought more than ten smaller banks. The pace was brisk, but the philosophy stayed consistent: stick to the criteria, integrate with the playbook, and don’t let growth weaken underwriting standards.

Then, in 1996, PNC went bigger. It merged with Midlantic Corporation—roughly $30 billion in assets, and far larger than anything PNC had taken on before. More important than the size was the geography. Midlantic delivered a major presence in New Jersey and a gateway into the New York metropolitan orbit. Suddenly, PNC’s footprint wasn’t just “out of Pennsylvania.” It stretched from Kentucky all the way to the edges of New York City.

Midlantic also showed that PNC would pay up when the asset was worth it. A high-quality franchise in New Jersey was hard to replicate; building that position branch by branch could take decades. Buying it could be done in one move—if you believed you could integrate it well enough to earn back the premium. PNC’s confidence came from the same place it always did in this period: the operating model. With platform consolidation underway and an integration machine getting sharper, the math looked achievable.

By 2000, the company had grown beyond a pure “bank” identity. PNC changed its name from PNC Financial Corporation to PNC Financial Services Group, a signal that fee businesses—asset management, wealth management, and other diversified services—were now meaningful parts of the mix.

What O’Brien and his successors built in these years wasn’t just a bigger footprint. It was capability: a disciplined acquisition strategy backed by a repeatable integration system, with technology at the center. Plenty of banks tried to grow through M&A. Many got sloppy, overpaid, or let easy times soften credit standards. PNC spent this era doing the opposite—methodically building a machine that would matter most when conditions turned ugly.

And eventually, they did.

V. The National City Acquisition: Crisis Creates Opportunity

By the fall of 2008, American finance wasn’t just wobbling. It was coming apart. Lehman had gone under. AIG needed a rescue. Money markets seized up, and suddenly no one trusted anyone else’s balance sheet. The bill for a decade of loose mortgage credit was arriving all at once.

National City Corporation was right in the blast radius. For generations, it had been a Cleveland pillar, woven into the commercial life of Ohio and the broader Midwest. But in the years leading up to the crisis, it had reached for growth in the most dangerous place possible: subprime mortgages, particularly through its First Franklin Financial subsidiary. When the housing bubble started to deflate in 2007 and borrowers began to default, the losses didn’t trickle in. They cascaded.

By late 2008, National City was running out of runway. Write-downs ate through capital. Depositors started to flee. Its stock had collapsed. The bank needed a buyer, not a strategy memo.

That set off a tense, public-feeling scramble. Wells Fargo showed interest. Fifth Third looked hard enough that it even floated moving its headquarters to Cleveland—an extraordinary offer that showed just how valuable National City’s footprint was, even in a crisis. KeyBank circled too.

PNC, though, was built for this kind of moment. Its acquisition machine wasn’t theoretical; it had been rehearsed for two decades. The common technology platform gave it a cleaner path to conversion than most would have had. And just as important, PNC had avoided many of the subprime excesses that were now dragging competitors under. It had the one thing that suddenly mattered more than ambition: balance-sheet strength.

On October 24, 2008, PNC announced it would acquire National City for $5.2 billion. The price was so low it earned a term of art: a “take-under,” meaning the offer came in below even National City’s already-crushed market value. That wasn’t kindness. It was math. National City’s loan book had become a sinkhole, and any buyer would need a price that reflected the losses still hiding inside it.

Then came the backlash.

Only hours before unveiling the deal, PNC had accepted $7.7 billion in TARP funds from the federal government. Critics pounced: a bank takes taxpayer capital and immediately turns around to buy a weakened rival—while National City itself had been denied TARP assistance. The optics were brutal, and the story wrote itself.

PNC and its defenders pushed back. TARP, they argued, was meant to stabilize the system by strengthening banks so they could keep credit flowing and prevent failures from spreading. A healthy bank absorbing a failing one was the point, not the abuse. And without a buyer, National City could have collapsed outright, potentially doing more damage to its customers, communities, and the regional economy.

The controversy never really disappeared. But the deal did.

Operationally, this was an integration with sharp edges. Cleveland and Pittsburgh are close—about 130 miles apart—so overlap was inevitable. Branch networks collided. Back-office functions duplicated. Layoffs followed in both cities, and in Cleveland the transaction felt less like salvation and more like the loss of a hometown headquarters to its cross-state rival.

Strategically, though, it was a leap forward. National City brought PNC a massive expansion in retail and commercial banking across the Midwest—Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and beyond—along with more than $100 billion in assets. Overnight, PNC moved from “large regional” to a superregional bank with national relevance.

And PNC did what it always claimed it could do: it ran the playbook. Systems migrated onto the common platform. Branches were assessed and consolidated where overlap demanded it. Credit problems were confronted head-on—worked out, written down, or sold. Culture, the hardest part of any crisis acquisition, was managed with the same deliberate, methodical approach that had made earlier deals work.

By 2010, PNC repurchased the stock it had issued to the U.S. Treasury and retired its TARP obligations. To help fund that repayment, it sold its Global Investment Servicing subsidiary to Bank of New York Mellon in July 2010—raising cash while shedding a business that no longer sat at the center of PNC’s strategy.

The payoff was what disciplined acquirers chase: time. National City gave PNC in one transaction what organic growth would have taken decades to build, making it the fifth-largest bank in the country by deposits. In a crisis that forced others into retreat, PNC turned preparation into position—proving a lesson it would lean on again years later: when others are forced to sell, the buyer who’s ready gets to reshape the map.

VI. Geographic Expansion: Building a National Footprint

With National City absorbed and TARP in the rearview mirror, PNC went looking for the next map to redraw. The obvious direction was south. The Southeast was growing faster than the older industrial markets PNC had long called home, and its banking landscape was still fragmented enough that a disciplined acquirer could build real share without paying peak prices.

The question wasn’t whether to go—it was how to get there without breaking the integration rhythm that had become PNC’s edge.

PNC’s answer was to enter the region the way it liked to do most things: deliberately, with targeted moves that added up. In 2011, it bought BankAtlantic’s Tampa Bay area branches, planting a flag in Florida. It wasn’t meant to be a headline-grabber. It was a beachhead—proof of presence in a high-growth market, with room to expand later.

The bigger opening arrived the following year. In 2012, PNC acquired RBC Bank from Royal Bank of Canada, which had decided to exit U.S. retail banking. That kind of strategic retreat is exactly the setup PNC loved: a motivated seller, a real franchise, and a price shaped by the seller’s desire to leave—not by an auction fueled with optimism.

For $3.45 billion, PNC picked up 426 branches across six Southern states: North Carolina, Florida, Virginia, Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina.

It was a clean fit with PNC’s philosophy. RBC’s branches were established and profitable, but they weren’t big enough for RBC to justify the ongoing investment needed to compete. For PNC, scale was the whole point. These locations extended PNC’s reach into fast-growing metros, connected naturally to its Mid-Atlantic footprint, and could be pulled onto the same common technology platform that made PNC’s acquisitions easier to digest than most.

Integration, once again, was the proof. The RBC conversion stayed on schedule. Customer retention hit targets. Savings showed up as redundant functions were consolidated. And with each successful deal, PNC wasn’t just getting bigger—it was getting better at the act of becoming bigger.

All the while, the ground under banking was shifting. Customers were moving online and onto mobile. The branch network that once defined a bank’s identity increasingly looked like a cost structure that needed to be rethought. PNC’s approach was to keep a physical presence where it mattered, but invest heavily in digital capabilities so the franchise could scale with changing customer behavior.

In 2015, the company opened the Tower at PNC Plaza in Pittsburgh—a new headquarters that doubled as a statement. The LEED Platinum-certified building won awards for its environmental features, using natural ventilation, a double-skin facade, and a solar chimney to cut energy use dramatically. Even as PNC expanded outward, it was signaling that Pittsburgh remained the center of gravity.

Then, in 2018, PNC introduced “Solution Centers,” a format built for how customers actually banked now. These locations blended traditional, staffed service with ATM-only convenience. For customers, it meant choice. For PNC, it meant a way to maintain touchpoints while lowering the cost of physical distribution.

None of this was glamorous. That was the point. After the strain of integrating National City and the push into the Southeast, PNC spent the years between 2012 and 2020 consolidating what it had won—strengthening operations, continuing technology investment, and keeping the acquisition machine tuned for the next moment when the industry would hand a prepared buyer an opening.

That opening arrived in 2020. As COVID-19 disrupted the economy, banking entered another consolidation phase. Smaller institutions struggled with remote operations and the sudden acceleration of digital demand. Larger banks started scanning for assets they could absorb at attractive valuations.

PNC didn’t need to rush. It had been building toward this. And when the right target appeared, it was ready to make its most ambitious move yet.

VII. The BBVA USA Acquisition: Coast-to-Coast at Last

In November 2020, BBVA—the Spanish banking giant—announced it would sell its U.S. subsidiary. For BBVA, it was an exit from a long, expensive American experiment. For PNC, it was the kind of rare, map-changing opening that almost never comes up at the right time.

BBVA USA wasn’t a tiny bolt-on. It was a full Sunbelt franchise: more than $100 billion in assets, 637 branches, and real scale in states where PNC had long wanted a presence—Texas most of all, but also Alabama, Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, and New Mexico.

Put the two footprints together and the picture snapped into focus. PNC already owned the East and much of the Midwest. BBVA filled in the fast-growing South and Southwest. Overnight, this wasn’t a “superregional” story anymore. The combined bank would have branches in 29 of America’s 30 largest metro areas—something that starts to feel like a national platform, not a regional patchwork.

PNC agreed to pay $11.6 billion in cash—an expensive price by any measure, roughly 19.7 times BBVA USA’s 2019 earnings. But that premium reflected what PNC was buying: not just branches, but time. Building a Texas-and-Sunbelt presence organically would take years and a lot of wasted spend. Buying it, if you could integrate it, was the shortcut.

The other notable part was how PNC financed it. No new equity. No dilution. PNC funded the deal from its own balance sheet, a choice that broadcast management’s view of the moment: we’re strong enough to do this, and confident enough to pay cash.

Then the world made the logic even clearer. COVID didn’t just disrupt banking; it rewired customer behavior. Digital adoption surged as people avoided branches. Smaller institutions struggled to keep up with remote operations and fast-moving technology expectations. Scale—already an advantage—started to look like the difference between keeping up and falling behind.

PNC’s pitch was straightforward: apply the same integration machine it had been refining since the 1980s, and let the numbers follow. The company targeted more than $900 million in annual cost savings, about 35% of BBVA USA’s estimated annual expenses. The levers were familiar: consolidate corporate functions, sort out overlapping locations, move customers onto PNC’s common technology platform, and cut redundant vendor contracts. The difference this time was the size of the bite.

That scale showed up in October 2021, when the conversion hit. About 2.6 million BBVA USA customers became PNC customers essentially overnight. Nearly 9,000 employees moved into the combined organization. Close to 600 branches flipped to the PNC brand. For something this large, the transition saw remarkably few disruptions—exactly the kind of operational competence that sounds boring until you realize how many bank mergers are defined by the opposite.

PNC also knew the deal would be judged on more than execution. Big bank mergers live and die by regulatory scrutiny, and community impact is always at the center of that conversation. So PNC announced an $88 billion Community Benefits Plan over four years, aimed at low- and moderate-income communities across the expanded footprint. It fit the public narrative of the merger—and it fit the practical reality that regulators want to see tangible commitments, not just synergy slides.

With BBVA USA, PNC completed the transformation it had been building toward for decades. The company that started as a Pittsburgh trust in 1845 now had meaningful presence across virtually every major U.S. market. It wasn’t one bold leap; it was the compounding result of a long strategy—patient buying, disciplined pricing, and an integration playbook that kept getting sharper.

And it sharpened the next question. PNC was now big enough to compete more directly with the national giants—JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo—while still trying to retain the Main Street sensibility of a regional bank. Whether that middle identity could hold, in a world of mega-banks on one side and digital disruption on the other, became the new strategic test.

VIII. Business Model & Competitive Advantages

Walk into a PNC branch in Pittsburgh or Phoenix and you’ll notice something that’s getting rarer in American banking: a bank that still feels local, even though it’s built at national scale. That’s PNC’s positioning in a sentence—Main Street banking, run with the balance sheet and operating muscle of a much bigger institution.

The model follows from that. While the biggest U.S. banks lean heavily on investment banking, trading, and capital markets revenue, PNC has stayed mostly in the classic lanes: taking deposits, making loans, and running the financial plumbing for households and businesses. It’s the kind of “boring” banking that doesn’t grab headlines—until a cycle turns and boring starts to look like a superpower.

Diversification, for PNC, comes less from Wall Street and more from fees that sit adjacent to core banking. Asset management serves institutions and individuals with investment products and advice. Wealth management helps affluent clients with planning and complex financial needs. Treasury management supports corporate customers with cash management, payments, and day-to-day liquidity. And PNC has built a large presence in SBA lending, leaning into the small-business segment that often gets less attention from the mega-banks.

It also has meaningful businesses in credit cards, asset-based lending, and syndicated loans, where PNC can act as lead arranger and bring multiple lenders into a single transaction. Those activities throw off fees, but the bigger win is relationship depth. A company that borrows through a PNC-led syndication may also run payroll, treasury, deposits, and retirement services through PNC. Over time, that bundle becomes hard to unwind—switching banks isn’t just a new loan; it’s ripping out infrastructure.

A huge part of why PNC can make that relationship model work across a wide footprint is technology. The decision in 1990 to move to a single common platform wasn’t just an IT cleanup—it became an advantage that kept compounding. Acquisitions could be converted onto one set of systems, products could be delivered consistently across markets, and operating costs stayed under control. Banks that postponed modernization often paid for it later in messy integrations and higher run-rate expenses. PNC, by contrast, kept building a repeatable conversion machine—and got faster and more confident every time it used it.

Then there’s credit. PNC’s culture has consistently favored underwriting discipline over growth-at-any-cost. It avoided many of the worst excesses of the dot-com era and the subprime mortgage boom, and that caution showed up when stress hit the system. In banking, the real advantage of strong credit isn’t just fewer losses; it’s optionality. When others are forced to retreat or sell, the healthier bank gets to go shopping.

Even the “regional bank” economics have their own quiet strengths. PNC can gather deposits in markets that are often less cutthroat than the ones dominated by the very largest banks, which can translate into a funding advantage. That lower-cost deposit base matters because it flows directly into net interest margin—the spread between what a bank pays for funding and what it earns on loans. Pair that with scale-driven efficiency, and you get a model that can be both simpler than the mega-banks and still meaningfully profitable.

None of this works without risk management, and PNC treats that as a system, not a slogan. Credit risk is only one category. Interest-rate risk, liquidity risk, operational risk, and compliance risk all have to be managed continuously, through playbooks and governance that were built over decades and tested in real crises—from 2008 to the pandemic.

Finally, there’s corporate and institutional banking—the sweet spot where PNC can be big enough to matter and still small enough to care. Mid-sized companies that have outgrown community banks but don’t want to be a rounding error at a mega-bank often find PNC to be a capable middle: sophisticated products, serious balance sheet, and a relationship approach that doesn’t disappear after the pitch. And once a company’s payments, treasury, and lending are embedded in a bank, those relationships tend to stick for a long time—exactly the kind of durable franchise value PNC has spent decades trying to compound.

IX. Playbook: M&A Excellence & Integration

Forty-plus acquisitions teach you things no textbook can. PNC’s integration methodology didn’t appear fully formed—it was built through repetition, missteps, course corrections, and then the steady accumulation of what actually works. Over time, that became a repeatable system, and it’s a big reason PNC has been able to do deal after deal without falling into the trap that catches so many acquisitive companies: announcing synergies and never really capturing them.

It starts long before a deal closes. PNC’s due diligence goes well beyond the balance sheet. The bank digs into the target’s technology systems, the realities of its culture, the people who actually hold the customer relationships, and the operational risks that can turn a “great strategic fit” into a messy conversion. By the time a transaction is announced, the integration isn’t a blank page—teams have already laid out conversion timelines and identified the first-year priorities.

Once the deal is signed, integration moves in deliberate phases, with clear milestones and accountability. The first job is stabilization: customers still get served, employees know what’s happening, and, most importantly, nothing breaks. Only after that foundation holds does PNC move into the harder, more value-creating work—consolidating overlapping branches, migrating systems, and centralizing functions that don’t need to be duplicated.

PNC also treats culture as a real variable, not a line item. Banking is a relationship business, and relationships are carried by people. If you mishandle a newly acquired workforce—through heavy-handed mandates or lingering uncertainty—you don’t just lose employees. You lose the relationships and revenue you thought you bought. PNC’s approach aims to balance the efficiency of consolidation with a level of respect for what made the acquired institution work in its market in the first place.

The signature capability, though, is technology integration. The platform consolidation work that began in 1990 became an asset that kept paying off: converting an acquired bank onto PNC’s common platform is complex, but it’s not improvised. It follows a proven playbook, run by teams that have done it before. That’s why the BBVA USA conversion—moving 2.6 million customers—could happen with minimal disruption. The scale was enormous; the process was familiar.

And then there’s the part that separates operators from storytellers: tracking whether the savings actually show up. PNC monitors cost synergy realization tightly and holds integration teams accountable for delivery. That discipline helps avoid the classic M&A failure mode where optimistic projections get a deal approved, but the organization quietly misses its targets once the spotlight fades. Over time, investors and boards learn which acquirers hit what they promise and which don’t. PNC’s ability to deliver has been a form of currency in its next negotiation.

None of this happens in a vacuum, because bank M&A is as much regulatory as it is strategic. Every significant acquisition runs through federal and state approvals, with regulators assessing competition, financial stability, and community impact. PNC has worked to build a reputation for constructive engagement across multiple administrations—credibility that matters when a complex transaction needs a green light.

Zoom out, and the biggest lesson is judgment: when to press and when to wait. PNC’s most aggressive moves—National City in 2008 and BBVA USA in 2020—came during periods of dislocation, when strong players could buy valuable franchises from weakened sellers at attractive prices. Seeing those moments requires analysis, but acting on them requires something else: organizational readiness, conviction, and the ability to move quickly while everyone else is still hesitating.

Just as important is the willingness to walk away. Serial acquirers often get addicted to deal-making, and the fastest path to destroying value is overpaying because you want to win. PNC has shown a consistent ability to say “no” when a target doesn’t meet its criteria—a discipline that protects shareholders even when competitive pressure or internal ambition is pushing the other direction.

X. Analysis & Investment Case

PNC sits in an unusual sweet spot in U.S. banking. It’s far bigger than the classic regionals, but it’s not one of the four giants that define the industry’s outer edge. That in-between scale shapes everything about the investment case: what PNC can do that smaller banks can’t, and what it avoids that tends to come with being a true mega-bank.

Stack PNC up against JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and Citigroup, and the contrast is mostly about complexity. The biggest banks lean hard into investment banking, trading, and capital markets—businesses that can be hugely profitable, but also add volatility, regulatory burden, and reputational risk. PNC is built around more traditional banking: deposits, loans, and fee-based services tied to day-to-day customers and businesses. It’s a simpler machine, with fewer ways to accidentally end up in the kind of headline spiral that has hit mega-banks before. The Wells Fargo scandals are the cautionary tale here: when a bank gets enormous and complicated, one cultural failure can become a national story. PNC’s Main Street orientation doesn’t eliminate that risk, but it reduces the surface area.

Now compare PNC to smaller regional peers like US Bancorp, Truist, Citizens, and Regions, and the advantage flips: scale. A coast-to-coast footprint allows PNC to serve clients that operate nationally, not just locally. Big technology investments—apps, security, data, compliance tooling—can be spread across a much larger customer base. And the BBVA USA deal created a geographic leap that isn’t easy for other regionals to copy without finding their own rare, map-changing acquisition.

The big swing factor for earnings is interest rates. PNC, like most traditional banks, lives and dies by net interest income. When rates rise, banks often benefit: loan yields tend to reprice higher, while deposit costs can lag—at least for a while—widening spreads. The rate increases of 2022–2023 were a meaningful tailwind. The mirror image is also true. When rates fall, margins compress, and profitability gets squeezed. Any view on PNC as an investment ends up, implicitly or explicitly, including a view on the rate cycle.

Then there’s credit—the ever-present risk that doesn’t look dangerous until the moment it is. Loan losses will happen; the question is how large they get and how fast they arrive when the economy turns. PNC’s conservative credit culture has historically helped it run with fewer self-inflicted wounds, but no bank is recession-proof. One area that warrants ongoing attention is commercial real estate, particularly office exposure as markets adjust to hybrid work patterns.

Management’s capital allocation is the other tell. PNC has returned substantial capital through dividends and share repurchases, which signals confidence in the durability of earnings. But capital is always competing for a home: keep investing for organic growth (especially technology and digital capabilities), keep buying back stock, or hold dry powder for the next acquisition opportunity. BBVA USA showed that PNC will swing when the pitch is right, but management has indicated a preference for organic growth in the near term.

Regulation is the backdrop to all of it. PNC isn’t in the same category as the very largest “systemically important” banks, but regulatory expectations rise with size. Stress testing, supervision intensity, and capital requirements add real cost. And any future acquisition that pushes PNC closer to “too big to fail” territory would likely face tougher scrutiny.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis:

The threat of new entrants is moderate. Banking takes capital, regulatory approval, and a lot of work to build trust and distribution, which keeps random newcomers out. But fintechs have proven they can enter through side doors—payments, lending, and wealth management—competing in profitable slices without carrying the full cost structure of a traditional bank.

Supplier power is limited. Banks largely fund themselves through deposits, where they have meaningful pricing power, and through wholesale markets, where there are plenty of funding alternatives.

Buyer power depends on who the buyer is. Large corporate clients can shop aggressively and push pricing through competitive bids. Retail customers typically face higher switching friction, which often makes those relationships more durable and economically attractive.

The threat of substitutes is rising. Digital payments, peer-to-peer lending, robo-advisors, and crypto platforms offer alternative ways to move money, borrow, and invest. How far that substitution goes depends on technology, regulation, and what customers actually adopt at scale.

Rivalry is intense, but usually rational. Banks compete on rates, convenience, service, and relationships, yet true price wars tend to be self-limiting—everyone knows how quickly they destroy industry economics.

Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers Framework:

Several of PNC’s advantages fit neatly into Helmer’s lens. Scale economies matter: technology, compliance, and marketing costs become more efficient as the customer base grows. Switching costs are real, especially for corporate clients whose treasury, payments, and lending are embedded in a bank’s systems. And process power may be PNC’s most distinctive edge—the integration methodology it’s refined over decades of acquisitions, a capability that’s hard to copy quickly even if competitors understand it in theory.

The bear case is straightforward: margin compression, credit losses, and the slow erosion of “traditional banking” economics. If rates fall sharply, net interest income takes a hit. If the economy contracts, credit costs rise—especially in areas like commercial real estate and consumer lending. And if fintech competition accelerates, banks risk being left with lower-margin relationships while the best niches get picked off.

The bull case is the other side of the same coin: scale, discipline, and a proven ability to capitalize on industry dislocation. PNC’s national footprint gives it a lane to win business that smaller regionals can’t consistently serve. Its integration capabilities create optionality for future acquisitions when opportunities reappear. And its fee businesses—asset management, treasury services, and card income—help diversify earnings beyond pure lending.

Key Performance Indicators:

Two metrics do most of the work in tracking whether the story is playing out.

First, Net Interest Margin (NIM): the spread between what PNC earns on loans and investments and what it pays for deposits and borrowings. It’s the simplest read on the health of the core engine, and it tells you how the rate environment is flowing through to earnings. Watch the trend, and just as importantly, listen to management’s commentary on deposit pricing and loan yields.

Second, the Efficiency Ratio: noninterest expense divided by total revenue. It’s a measure of operating leverage—how much profit the bank can produce from each dollar of revenue. Lower is better. Over time, it reveals whether technology investments are paying off and whether the cost savings promised in acquisitions actually show up in the numbers.

XI. Future Vision & Strategic Options

When William Demchak became CEO in 2013, he inherited a bank that already knew how to buy—and, more importantly, how to digest. His job was to keep that discipline intact while steering PNC through a decade where the rules of competition were changing fast. The BBVA USA deal essentially finished the geographic story that PNC and its predecessors had been writing for decades. Now the question is what comes after “coast-to-coast.”

There are still geographic white spaces on the map, but they’re narrower now. The Pacific Northwest, the Mountain West, and parts of the upper Midwest remain plausible expansion territories. But the payoff from simply adding pins to the branch map has been shrinking for years. As more customers default to online and mobile, physical presence matters less than it used to—and the strategic value of building or buying another big branch network has to clear a higher bar than it did in the 1990s or even the early 2010s.

That puts digital banking at the center of the next decade. PNC has invested heavily in mobile and online capabilities, but the pace keeps accelerating. Fintech competitors can move quickly, unburdened by legacy systems and many of the constraints that come with being a regulated bank at scale. For PNC, staying competitive isn’t a one-time modernization project. It’s a permanent commitment—continuous investment, faster iteration, and the organizational agility that large institutions often find hardest to sustain.

The same logic is reshaping branches. PNC’s Solution Centers, introduced in 2018, are a visible acknowledgment that the old model—fully staffed locations built for routine transactions—is fading. The new model leans into automation for everyday needs while keeping human help available for complex moments: advice, small business needs, bigger decisions. But transforming a network is slow, capital-intensive work, and it requires careful change management as employees shift into different roles and customers adjust to different expectations.

On the M&A front, the hunting has gotten tougher. Many of the best regional franchises have already been scooped up, and the ones that remain often trade at valuations that make a deal hard to justify without heroic synergy assumptions. A true merger of equals—say with US Bancorp, Truist, or a similar large regional—would create instant scale, but it would also invite regulatory complexity and the kind of integration risk that can erase the benefits you’re chasing. For a bank that built its reputation on controlled execution, that’s not a small tradeoff.

A more natural growth lane is wealth management. High-net-worth relationships generate attractive fee income and tend to stick, especially when a bank can serve multiple needs over long horizons. PNC already has a wealth management platform it can expand through organic investment or targeted acquisitions. And the macro tailwind is obvious: the aging of America’s baby boom generation is setting up one of the largest wealth transfers in history, a multi-decade opportunity for any institution that can win trust early and keep it.

Investment banking is a less likely pivot. PNC has historically stayed closer to traditional banking, and the most lucrative capital markets businesses are dominated by firms with entrenched client relationships and deep talent benches—JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley. Replicating that would be expensive, culturally disruptive, and strategically inconsistent with what has made PNC work. The disciplined move is usually the unsexy one: double down on where you already have an edge.

Another expanding arena is climate finance and ESG. For large banks, sustainability is no longer a side conversation—it’s increasingly part of how corporate customers make decisions and how regulators set expectations. PNC has committed to sustainable lending targets and has signaled priorities through actions like green building standards. As climate-related regulation and customer demand evolve, banks that build real expertise can win business that didn’t exist in the same form a decade ago.

Cryptocurrency and blockchain, by contrast, remain more tentative. The volatility and regulatory uncertainty around digital assets make major commitments hard to justify. But the underlying technologies could still reshape parts of banking—payments, settlement, verification—in ways that matter. The pragmatic stance is watch closely, experiment carefully, and be ready to adapt if the infrastructure shifts under the industry.

All of this circles back to the core strategic question: can PNC realistically challenge the Big Four banks for industry leadership? BBVA USA brought PNC to roughly $560 billion in assets—huge by any normal standard, but still less than half the size of Wells Fargo, the smallest of the mega-banks. Closing that gap would likely require something transformative, and transformative moves in banking tend to come with outsized regulatory scrutiny and execution risk.

The alternative is the path PNC has historically preferred: maximize returns from the position it has earned. A national platform with strong regional relationships. A proven operating model. A management team that knows when to swing—and when not to. It’s not as dramatic as trying to topple the giants. It’s also far more consistent with the approach that built PNC in the first place: operational excellence, organic growth where it compounds, and opportunistic acquisitions when the market finally offers the right deal at the right price.

XII. Recent News

As the banking sector moved into 2026, the big macro story was the same one investors had been watching since the Fed’s rapid tightening through 2023: interest rates were no longer in “emergency mode,” but they also weren’t back to the easy-money world that defined the 2010s. For PNC, that environment has been a mix of tailwinds and friction. Higher rates helped lift net interest income, but the other side of that coin has been deposit competition. Customers have gotten more rate-sensitive, and banks have had to work harder—and pay more—to keep funding sticky.

At the top, the leadership picture has stayed steady. CEO William Demchak remained in place, continuing to steer the post-BBVA strategy: protect the credit culture, keep expenses under control, and keep investing in the parts of the franchise that actually compound. At the board level, the mix has continued to evolve, adding perspectives meant to match PNC’s broader national footprint.

On the product side, PNC has kept pushing deeper into digital. Technology partnerships have helped expand mobile banking capabilities and strengthen tools for corporate treasury management—areas where expectations have shifted from “nice to have” to table stakes. The goal is straightforward: make the bank feel as modern as its footprint is large.

Regulation has also kept tightening its grip. Updated capital requirements and climate-risk disclosure rules have forced continued investment in compliance and reporting. PNC’s scale helps it absorb those costs better than smaller banks, but the direction of travel is clear: the bar keeps rising, and no large bank gets to opt out.

Operationally, the BBVA USA integration has continued to look like what PNC promised it would be: stable market share in key regions, retention results that supported the thesis, and cross-selling that started to show up as former BBVA customers gained access to PNC’s broader product set.

Wall Street’s view has remained a balancing act. Analyst sentiment has swung between cyclical worries—recession risk, credit losses, and margin pressure—and the counterargument that PNC’s core strengths are built for exactly this kind of environment. Ratings and price targets have varied accordingly, often telling you less about PNC itself and more about how each analyst sees the next turn of the rate cycle.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings: - PNC Financial Services Group annual reports (SEC Form 10-K) - Quarterly earnings releases and investor presentations - Proxy statements covering executive compensation and governance - BBVA USA acquisition proxy and merger documents - National City Corporation merger filings (2008)

Regulatory Resources: - Federal Reserve filings and stress test results - FDIC banking statistics and historical data - Office of the Comptroller of the Currency reports

Historical Resources: - Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania archives on Pittsburgh banking - Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Philadelphia Inquirer historical coverage - Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland economic commentary

Industry Analysis: - American Bankers Association research publications - S&P Global Market Intelligence banking data - Moody’s and Fitch bank credit research - Federal Reserve Bank research on regional banking consolidation

Books and Long-Form Analysis: - The Bankers: The Next Generation by Martin Mayer - Broke: America’s Banking System by Roland Jones - Academic literature on bank mergers and integration

Technology and Innovation: - American Banker coverage of digital transformation - Bank Technology News - Fintech research from major consulting firms

Economic Context: - Bureau of Labor Statistics regional economic data - Bureau of Economic Analysis GDP and regional accounts - Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) interest rate series

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music