Quanta Services: Building the Infrastructure Backbone of the Energy Transition

I. Introduction & Episode Teaser

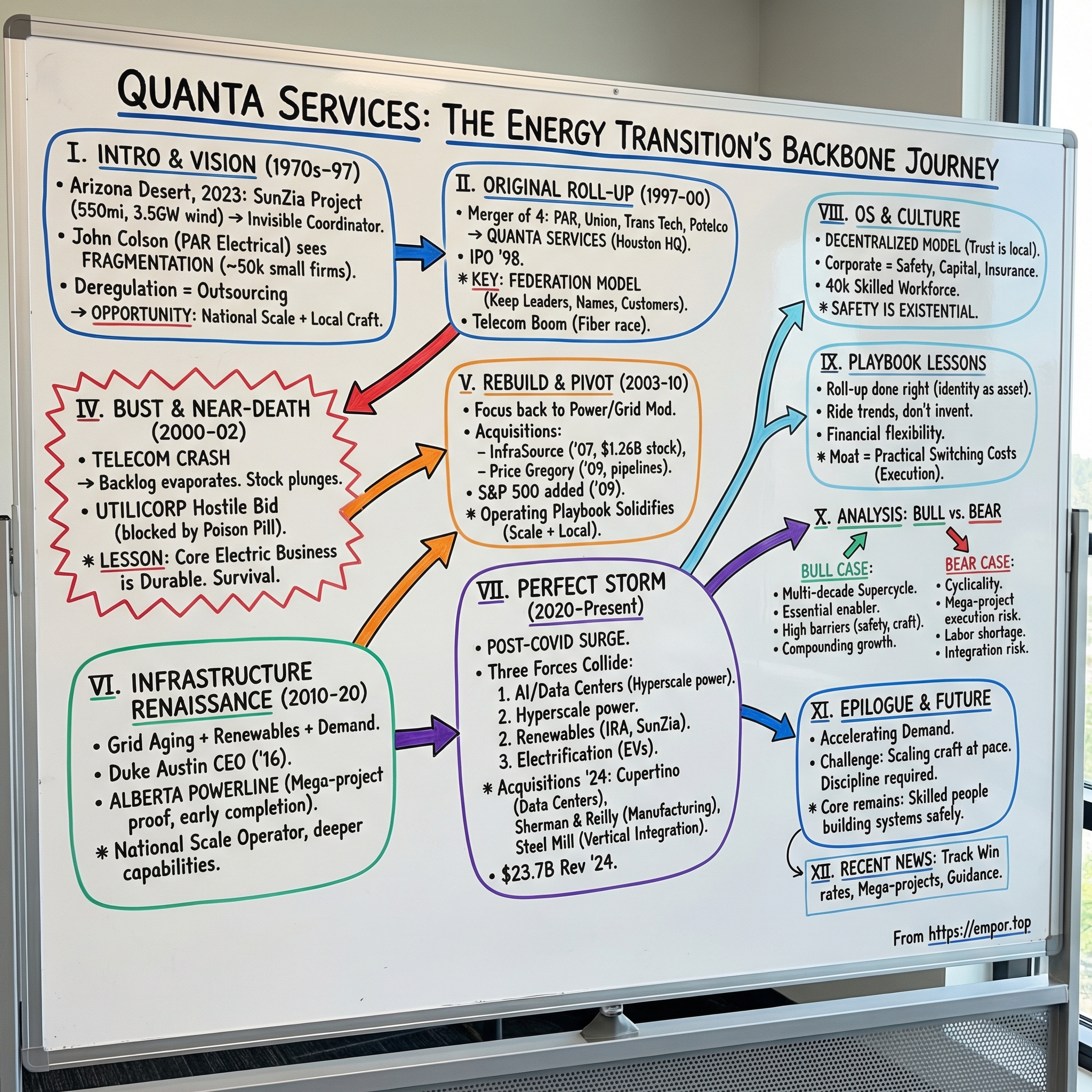

Picture a construction site in the Arizona desert in late 2023. The sun is brutal, the terrain fights you at every step, and cutting across the horizon is the early outline of what’s slated to become the largest clean-energy transmission project in U.S. history: roughly 550 miles of high-voltage lines designed to move wind power from New Mexico to the demand centers of Arizona and California. Crews climb steel towers that will soon carry about 3.5 gigawatts of renewable electricity—power on the scale of millions of homes.

The company coordinating this is not a household name. It doesn’t build wind turbines or sell electricity. It won’t own the lines when they’re finished, and it won’t be the utility sending power bills to customers.

But without Quanta Services, this project doesn’t happen.

Quanta sits in a strange and incredibly important spot in the American economy. It’s a nearly $25 billion-a-year infrastructure contractor growing at more than 15% annually, and it has become a go-to partner for the hardest, most mission-critical work in energy. When utilities need to rebuild and harden aging grids, they call Quanta. When renewable developers need new transmission to get power from remote wind and solar resources onto the grid, they call Quanta. And when the hyperscale data centers behind the AI boom need more reliable power—often fast—the people building that electrical infrastructure are frequently wearing Quanta hard hats.

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the center of this story: how did a roll-up of four electrical contractors become one of the most essential enablers of America’s energy infrastructure?

The answer runs through three decades of relentless acquisition, a couple of genuine brush-with-death moments, and a knack for showing up at exactly the right place in each successive infrastructure wave—then scaling faster than anyone else.

And the timing couldn’t be better. The U.S. is entering what could be the biggest infrastructure buildout of our lifetimes. Three forces are colliding all at once: AI is driving a surge in data center power demand, the energy transition is forcing a massive expansion of transmission, and the grid itself—much of it built generations ago—is overdue for modernization. Quanta didn’t create these trends. But it has built itself into the company that makes them real.

This is a story about vision, consolidation, survival, and transformation. And it starts not in a boardroom, but with a guy who learned the business from the ground up—one job site at a time.

II. The Fragmented Industry & Founding Vision (1970s-1997)

In 1971, John Colson finished his military service and came home looking for his next chapter. He landed in Kansas City, where PAR Electrical Contractors was hiring, and took a job that—at the time—looked like a solid trade career, nothing more.

PAR was exactly what you’d expect in electrical contracting back then: capable, local, and one of thousands. The industry was almost absurdly fragmented—around 50,000 firms, mostly small, owner-run operations with a few trucks, a tight-knit crew, and relationships that rarely extended far beyond a region. These were businesses built on craft and reputation. They were not built for national scale, and they certainly weren’t built for Wall Street.

Colson started on the engineering services side, learning the work from the inside out. But he also had a knack for seeing the whole system—how jobs were won, how crews were deployed, where projects went sideways, and why. He moved up fast: engineering services manager, then vice president of operations, then executive vice president and general manager. By the time he was effectively running PAR day to day, he wasn’t just fluent in the trade. He understood the industry’s constraints—and what would have to change for it to get bigger.

Because for most of the 1980s, the rules were stable. Utilities owned their transmission and distribution networks and kept large in-house workforces to build and maintain them. Contractors like PAR filled in around the edges—overflow work, specialized projects, extra crews when utilities needed them. The utility was the center of gravity. Contractors orbited.

Then the ground shifted.

Starting in the late 1980s and accelerating through the 1990s, deregulation began dismantling the old, vertically integrated utility model. The pitch was efficiency. The impact was outsourcing. Utilities looked at their cost structures and asked a simple question: why keep expensive internal construction crews when you can bid the work out and make contractors compete for it?

To many contractors, it just meant more jobs.

To Colson, it looked like a permanent change in how the industry would be organized. If utilities were going to outsource more and more of their construction and maintenance, eventually they wouldn’t want to manage a chaotic web of tiny vendors. They’d want fewer partners—bigger ones—able to handle complex projects, across wide geographies, with consistent safety standards and execution. The mom-and-pop structure that had defined the industry for generations wasn’t going to disappear overnight. But it was no longer the inevitable end state.

In 1991, Colson acquired ownership of PAR and became president. He kept it profitable and strengthened its reputation. But he also started thinking past PAR. What if you could build a platform—one company that could bring together the best operators in this fragmented world and offer utilities something they didn’t really have yet: national capability with local execution?

Inside Quanta, there’s a story about when the idea stopped being theoretical. On a hunting trip in 1998, Colson and a small group of trusted colleagues debated what it would actually take to build that platform. Going public would give them the currency for acquisitions and the balance sheet to play offense. It would also mean giving up privacy, living with public-market scrutiny, and answering to shareholders.

But the opportunity was sitting right there in the numbers and the structure of the market. Electrical contracting was a massive industry, yet its “leaders” were still regional. If you could consolidate even a small slice of those tens of thousands of businesses, you’d have something new: a company with real scale—purchasing power, broader reach, and the ability to take on bigger, more complicated work. And as utilities outsourced more of their infrastructure build, those capabilities wouldn’t be a luxury. They’d be the price of admission.

Colson’s core insight was simple: the work would always be craft. You can’t outsource away the reality of climbing poles, setting towers, or splicing high-voltage cable. But the business of delivering that craft—the management, the capital, the geographic footprint, the ability to reliably execute at scale—was about to professionalize.

The vision was there. Now came the hard part: turning it into a company.

III. The Original Roll-Up: Creating Quanta (1997-2000)

In 1997, four companies that had competed for years did something almost unthinkable in this business: they decided to join forces. PAR Electrical Contractors out of Kansas City teamed up with Union Power Construction Company, Trans Tech Electric, and Potelco Inc. The new company was called Quanta Services, and it set up headquarters in Houston—close to the energy world, and close to investors who understood big infrastructure bets.

Pulling off that merger wasn’t just paperwork. These weren’t disposable assets; they were proud, founder-led contractors with deep local roots. And the usual playbook—buy the firm, replace leadership, rebrand everything, squeeze “synergies”—would’ve wrecked the very things utilities paid for: trusted relationships, seasoned crews, and a reputation built over decades of showing up and getting the job done.

So Colson and the founding team made a choice that became Quanta’s signature. Companies that joined Quanta would keep their leaders, keep their names, and keep their customer relationships. Corporate would bring capital, shared services, and the ability to pursue larger work—but day-to-day operations stayed with the people who knew the territory. Not a monolithic operator, but a federation: local execution with a bigger balance sheet behind it.

That wasn’t just a nice way to keep everyone happy. It was a practical truth about contracting. In electrical construction, relationships are local and trust is personal. Utilities want the contractor that already knows their system, their standards, and their pain points. A contractor’s value is tied to specific people in specific places. Rip out the leadership or erase the identity, and you don’t “integrate” the business—you hollow it out.

With the structure set, Quanta went to the public markets. In February 1998, it completed its IPO, led by BT Alex Brown, raising $45 million. Later that year, it listed on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker PWR. It was a tidy symbol for a company that intended to make power infrastructure its home field.

Quanta didn’t raise that money to sit on it. From the start, the plan was straightforward: buy excellent regional contractors, plug them into the platform, and keep going. In 1999 alone, Quanta acquired eleven companies with roughly $150 million in combined revenue.

And it couldn’t have picked a more turbocharged moment to get rolling. The late 1990s were full-throttle for telecom and anything internet-adjacent. Fiber networks were going in at a breakneck pace. Cable operators were upgrading plant to deliver broadband. Utilities were modernizing, too. Much of that work lived in the same physical world—utility poles, trenches, rights-of-way—and required the same kinds of crews and equipment.

Quanta’s leadership framed it as a convergence thesis: power, telecom, and cable infrastructure were becoming intertwined, so a contractor with capabilities across all three would be better positioned, less exposed to any single cycle, and more valuable to customers who needed multiple services. The acquisition mix followed that logic, bringing telecom-focused builders into the fold alongside traditional electrical contractors.

Investors bought in. A roll-up in a huge fragmented market, growing fast, using public equity as acquisition currency—this was exactly the kind of story the late-’90s market rewarded. Quanta’s market value climbed as people priced in years of deal-driven expansion.

What almost nobody appreciated was how quickly that convergence could reverse—and how close Quanta would come to losing control of its own fate.

IV. The Boom, Bust & Near-Death Experience (2000-2002)

The telecom boom carried Quanta right through 1999 and into 2000. Work flooded in as carriers raced to lay fiber and connect cities across the country. Backlog grew, crews stayed busy, and the acquisition engine kept turning. For a brief window, it looked like the perfect proof point: take a fragmented industry, roll it up, and ride a once-in-a-generation buildout.

Then the floor gave out.

The telecom crash of 2000 and 2001 was brutal and fast. Companies that had looked unstoppable suddenly ran out of capital. Big names like WorldCom and Global Crossing collapsed, and plenty of smaller players disappeared with them. Fiber that had cost a fortune to install sat unused. And for the contractors who’d built it, “backlog” stopped being a comfort word and started being a question mark.

Quanta wasn’t a pure telecom contractor, but it had real exposure. Projects got delayed or cancelled. Forecasts snapped downward. The stock price fell hard as investors backed away from anything tied to telecom infrastructure.

And just as the business pressure peaked, a corporate threat showed up that could have changed Quanta’s future entirely.

UtiliCorp United, a diversified energy company, had been quietly buying Quanta shares. By 2001 it owned 38.5% of the company—close enough to matter, and uncomfortably close to control. That year, UtiliCorp made a move that amounted to a hostile takeover attempt. The pitch was familiar: Quanta would be “better” inside a larger parent, with more oversight, more structure, and supposed synergies.

Colson and his team saw a different outcome. Quanta’s entire model depended on a delicate bargain: local operators kept running their businesses, and the parent company provided capital and scale without smothering what made each contractor valuable. Fold that federation into a utility conglomerate, and you don’t just change the org chart—you risk breaking the culture and relationships that customers actually paid for.

So Quanta fought back. In October 2001, it negotiated a standstill agreement limiting UtiliCorp’s ability to increase its stake. The next month, the board adopted a poison pill—a shareholder rights plan that effectively blocked any investor from owning more than 39% without board approval. It was a clear message: Quanta intended to stay independent.

Those moves bought time. They didn’t fix the market.

Telecom spending kept sliding. The electric utility side of the business was steadier, but not growing fast enough to fully absorb the telecom hit. Quanta shifted into survival mode: tighten costs, protect cash, and keep the operating companies functioning until demand returned.

In hindsight, the near-death stretch of 2001 and 2002 rewired how Quanta thought about risk and strategy.

One: concentration risk is real. The “convergence” idea hadn’t been wrong, but it had pulled Quanta too far into a single, overheated cycle at exactly the wrong moment.

Two: independence isn’t a given. If you build something strategically important, someone will eventually try to buy it—especially when your stock is down and your industry looks shaky.

And three, the most important lesson: the core business was solid. Even in the worst of the telecom collapse, the electrical side kept doing what it had always done—maintaining grids, building transmission, and generating cash. The need for infrastructure work didn’t vanish. The bubble had just distracted everyone from the durable part of the story.

When the dust finally settled, Quanta was still standing—leaner, more disciplined, and newly clear on what it was, and what it wasn’t. The company that would later define the next wave of American infrastructure had been forged, uncomfortably, in crisis.

V. The Rebuild & Strategic Pivot (2003-2010)

By 2003, Quanta had made it through the worst of the telecom wreckage. Now it had to decide what kind of company it wanted to be on the other side. John Colson, after steering the business through the UtiliCorp threat and the downturn, stepped into the Chairman role. And with a little breathing room, the strategy snapped into focus: telecom might boom, but electric power would endure.

This wasn’t a dramatic exit from communications work. Quanta kept those capabilities because they were still useful. But the center of gravity shifted back to what had proven resilient even in the crash: building and maintaining the infrastructure that keeps the lights on.

Utilities, after years of deregulation-driven outsourcing, were staring at a different problem now—one they couldn’t postpone forever. Much of the U.S. grid had been built in the middle of the twentieth century. Transmission lines, substations, transformers—huge parts of the system were aging beyond their intended service lives. The question wasn’t whether spending was coming. It was when, and whether the industry had enough capable partners to execute safely at scale.

Quanta intended to be that partner.

The acquisition machine kept running, but with sharper aim. Instead of chasing whatever category was hottest, Quanta prioritized businesses with deep utility relationships and real electric transmission and distribution capability. The company wasn’t trying to be everything to everyone anymore. It was trying to be the best in the markets that mattered most.

That focus set up the defining deal of the era. In 2007, Quanta acquired InfraSource Services in an all-stock transaction valued at about $1.26 billion. InfraSource was one of the largest specialty contractors in the country, with strengths in underground infrastructure, gas distribution, and electric transmission. Overnight, Quanta got much bigger—and much harder to ignore. The deal more than doubled Quanta’s scale and pushed it to the front of the pack in electric power infrastructure services.

Just as important was how Quanta did it. Paying in stock, rather than loading up on cash and debt, protected the balance sheet and kept Quanta flexible. It also signaled confidence: management was effectively telling the market that owning more of Quanta’s future was worth more than taking a check today.

In 2009, Quanta widened its energy footprint again with the acquisition of Price Gregory International for roughly $350 million in cash and stock. Price Gregory specialized in large-diameter pipeline construction—exactly the kind of capability that would matter as natural gas infrastructure expanded across the U.S. It was a move into a new segment, but still consistent with the bigger thesis: be essential to the buildout and maintenance of energy infrastructure, wherever investment was headed next.

By the end of that year, the market was treating Quanta differently too. In December 2009, it was added to the S&P 500, replacing Ingersoll Rand. Index inclusion brought more institutional ownership and liquidity, but more than that, it was a public marker of what had happened over the decade: Quanta had moved from a contractor roll-up story to a company with real national significance.

Out of this rebuild, Quanta’s operating playbook solidified. Acquired companies kept their names and leadership. But Quanta layered in the stuff that individual contractors could never justify on their own—safety systems, insurance scale, equipment purchasing power, legal and administrative support. The advantages didn’t come from forcing everyone into one standardized mold. They came from letting local operators keep doing what they did best, while the parent company made them stronger and more competitive.

And by 2010, the pieces were in place. When utilities needed transmission built, Quanta had the crews and gear. When the energy system needed new connections and upgrades, Quanta had the expertise. When pipeline infrastructure demand grew, Quanta had Price Gregory. The company had rebuilt itself—and in the process, quietly positioned itself for the next decade’s infrastructure renaissance.

VI. The Infrastructure Renaissance (2010-2020)

The decade that followed wasn’t about one explosive bet. It was about Quanta steadily getting bigger, more capable, and more central to a grid that was being asked to do things it was never designed to do.

By the early 2010s, the grid modernization imperative Colson had been talking about for years stopped sounding like a thesis and started looking like a work order. Utilities were facing three pressures at once: equipment that was aging out, renewable generation that needed to be connected, and rising demand from population growth and electrification.

The renewables piece made the problem obvious in a very physical way. A wind farm in West Texas can generate plenty of clean energy, but it might as well be on the moon if there’s no high-voltage path to the cities where the power is needed. That means long-distance transmission—hundreds of miles of towers, wire, rights-of-way, and heavy logistics across terrain that doesn’t care about your schedule. This is Quanta’s wheelhouse.

At the same time, the grid’s underlying architecture was shifting. The mid-century system was built for big power plants pushing electricity outward. The new system had to handle power coming from everywhere: wind farms in remote areas, solar on rooftops, batteries sprinkled throughout the network. More complexity meant more upgrades—new lines, rebuilt substations, modernized distribution networks. And every upgrade created more demand for the kind of specialized crews and project execution Quanta had been assembling for years.

In March 2016, Quanta went through a leadership transition that matched the moment. Duke Austin, a long-time Quanta operator who understood both the field realities and the company’s decentralized model, became CEO. The cultural through-line stayed intact—craft, safety, local leadership—but the ambition expanded. Under Austin, Quanta leaned further into larger, more complex projects than it had historically pursued.

Another tailwind arrived in the form of the natural gas pipeline boom in the mid-2010s. As hydraulic fracturing reshaped U.S. energy production, the country needed new pipe to move gas from where it was produced to where it was consumed. Quanta’s earlier move into pipelines—especially through Price Gregory—proved its worth as the company executed major projects across the country and showed it could compete in another critical category of energy infrastructure.

Quanta also started to widen its geographic footprint. Expanding in Canada and Australia brought diversification and exposure to different infrastructure cycles. Canada, in particular, offered attractive transmission opportunities as provinces invested in modernizing their networks.

And then there was Alberta.

The Alberta PowerLine project became a defining proof point for what Quanta was turning into. The job: build roughly 500 kilometers of transmission line to connect Fort McMurray to the Alberta grid. The contract was enormous—about 1.6 billion Canadian dollars—and the conditions were as demanding as the scope. This was exactly the kind of project that smaller contractors couldn’t credibly bid, let alone deliver.

Quanta finished it three months early.

On a project of that size, “early” isn’t just a nice headline. It signals something deeper: that you can manage the complexity, control the risks, coordinate the labor and equipment, and still execute. For customers, it builds trust. For investors, it changes the ceiling on what the company can be. Quanta wasn’t just a roll-up of good contractors anymore. It had become a national-scale operator capable of mega-project work.

By the end of the decade, Quanta had built a platform spanning electric transmission and distribution, pipeline construction, communications infrastructure, and industrial services. It had grown steadily, stayed disciplined, and built a backlog that gave visibility into what was coming next. The company was well positioned—but the next wave would be bigger, faster, and more dramatic than almost anyone expected.

VII. The Perfect Storm: AI, EVs & Energy Transition (2020-Present)

When COVID hit in early 2020, huge swaths of the economy froze. But the grid doesn’t get to quarantine. Electrical infrastructure work was deemed essential, and Quanta kept operating—under stricter safety protocols, but with crews still in the field. Instead of coming out of the pandemic battered, Quanta came out fit, funded, and ready for what was about to happen next.

And what happened next was bigger than almost anyone modeled.

By 2022, Quanta was doing about $17 billion in annual revenue. In 2023, that jumped to $20.9 billion. Then 2024 climbed again to $23.7 billion. For an industry that’s used to grinding out modest growth, Quanta was suddenly putting up numbers that felt almost tech-like. Not because it became a software company, but because the world started demanding more physical infrastructure, faster, all at once.

The reason wasn’t one trend. It was a pile-up.

First: AI. The boom in large-scale computing created a new kind of electricity customer—the hyperscale data center. Training models and running AI at scale takes staggering amounts of power. The campuses being built by Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and others can draw hundreds of megawatts, like a small city turning on overnight. Getting that power to the fence line, safely and reliably, is exactly the kind of high-voltage, high-complexity work Quanta was built for.

Second: renewables. Solar and wind kept getting cheaper, and policy support got stronger. Projects started moving from “good idea” to “let’s build it”—at massive scale. But renewables don’t help much if you can’t move the power from where it’s generated to where people live. That means more interconnections, more substations, and more long-distance transmission. The Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 poured fuel on that fire, pushing more capital into clean energy and grid infrastructure.

Third: electrification. EV adoption was still early, but the direction was clear. As transportation shifts from gasoline to electricity, the grid has to serve a much larger load. Charging infrastructure—at homes, in depots, along highways—doesn’t appear by magic. It gets designed, permitted, wired, and built.

Then there’s the project that makes all of this concrete: SunZia.

Announced in 2023, SunZia is a roughly 550-mile, 525-kilovolt transmission line designed to carry about 3.5 gigawatts of wind power from New Mexico into Arizona and California. It’s the largest clean-energy infrastructure project in U.S. history, and Quanta is the lead contractor.

SunZia is the kind of job where the headline numbers are almost beside the point. What matters is what it demands: years of execution across harsh terrain, a massive workforce, complex logistics, and supply chains that have to hold together under pressure. There aren’t many contractors on earth that can take on a project like this with credibility. Quanta is one of them—and it’s built its brand on delivering.

Quanta didn’t just ride these waves. It spent 2024 upgrading its surfboard.

That year, the company acquired Cupertino Electric for about $1.5 billion. Cupertino was one of the largest electrical contractors in the U.S., and the strategic prize wasn’t just size—it was specialization. Cupertino had built more than 20 million square feet of data center space. In a world where AI is turning power delivery into a competitive constraint, that kind of experience is no longer “nice to have.” It’s a direct line into some of the most urgent, best-funded construction on the planet.

Also in 2024, Quanta bought Sherman & Reilly, a manufacturer of electric power components founded in 1927. This pushed Quanta further into vertical integration—owning not just the crews that build transmission and distribution infrastructure, but some of the equipment that goes into it. That can mean more control over supply, less exposure to bottlenecks, and a better ability to deliver on schedule.

And then came one of the more unconventional moves: buying a steel mill that produces rebar. Contractors don’t typically step into materials manufacturing. But the logic was straightforward: infrastructure consumes enormous amounts of steel, and supply reliability matters when you’re trying to build faster than the system is comfortable with. It was a signal that Quanta wasn’t only thinking about winning projects. It was thinking about controlling the constraints that can make mega-projects go sideways.

Through this stretch, the results backed up the strategy. Growth stayed strong, the company held up amid inflationary pressures, and backlog continued to build. Management’s outlook for 2025 called for continued double-digit growth in revenue, adjusted EBITDA, and earnings per share.

For anyone watching, the question shifted. It wasn’t “will Quanta benefit from infrastructure spending?” That was already happening. The real question became: can Quanta keep executing at the new scale the world is demanding—and is this the start of a sustained supercycle, or just another peak before the next downturn?

VIII. The Operating System & Culture

To understand Quanta’s results, you have to understand how it’s built. This isn’t one giant contractor running everything from a headquarters. It’s an operating system—an organizational design that lets Quanta execute across thousands of job sites while still absorbing deal after deal. And after more than 150 acquisitions, that’s the real trick.

The core idea hasn’t changed since the beginning: decentralization. When Quanta buys a company, it usually doesn’t erase it. The business keeps its brand. The leaders stay in place. The crews keep working with the same customers. So a utility in Kansas that’s trusted the same contractor for twenty years doesn’t suddenly get “integrated” into a faceless corporate machine. From the customer’s perspective, the relationship is intact. The name on the ownership paperwork changes, and that’s about it.

Quanta gives up some textbook efficiencies by doing this. A centralized model could squeeze harder on purchasing, consolidate back-office roles, and standardize operations. But Quanta has repeatedly made the same call: in this industry, the asset isn’t a logo. It’s trust. It’s the superintendent who knows the utility’s system. It’s the crew that’s proven it can do the work safely. And if you break that, whatever you saved on overhead isn’t worth what you lose in relationships and reputation.

Instead, corporate steps in where scale actually matters. Safety programs are consistent across the Quanta universe, which is non-negotiable in work where the hazards are real and immediate. Equipment procurement benefits from buying power that a single regional contractor could never match. Insurance, legal support, and financial reporting sit at the center, so local operating companies can stay focused on what they do best: getting difficult infrastructure built in the real world.

That model is powered by people—about 40,000 of them. And not the kind of workforce you can swap in and out overnight. These are skilled trades: linemen working at height around energized lines, fiber technicians doing precision splices, pipeline welders held to exacting standards. A lot of Quanta’s competitive advantage is simply the depth of capability embedded in that workforce, built over years of training and experience.

Which brings us to the most important cultural pillar: safety. In this business, safety isn’t a slogan or a quarterly initiative. It’s existential. One mistake around high-voltage electricity, heavy equipment, confined spaces, or heights can be fatal. Utility customers know that, and they pay attention. A contractor with a bad safety record doesn’t just risk injury—it risks getting shut out of work, no matter how aggressive the bid is. Quanta’s emphasis on safety training and performance isn’t just good practice; it’s a durable advantage.

Put it all together and you get something like a franchise system for infrastructure. Local companies keep their autonomy, their customer intimacy, and their operational hustle. Corporate provides the scale tools: capital, systems, purchasing leverage, and risk management. The blend is what makes Quanta unusual—entrepreneurial at the edge, institutional at the core.

In recent years, that system has also gotten more tech-enabled. Drones can survey transmission corridors that once required slow, risky ground traversal. Digital project tools help track progress across thousands of concurrent jobs. GIS mapping improves planning and reduces surprises in the field. Quanta isn’t trying to become a technology company; it’s using technology to make the hard physical work safer, faster, and more predictable.

And that predictability is what customers ultimately buy. The clearest proof isn’t a slide deck—it’s execution. Delivering a massive job like Alberta PowerLine early is the output of the whole machine: local craft, disciplined project management, strong safety culture, and enough scale to keep labor, equipment, and logistics coordinated. Over time, that track record becomes Quanta’s real moat. When customers hire Quanta, they’re betting the project will get done safely, on schedule, and for the price everyone agreed to.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investment Lessons

Quanta’s three-decade run isn’t just a story about poles, wire, and pipelines. It’s a case study in how to build a durable company in a messy, cyclical, people-driven industry—without getting seduced by the usual shortcuts.

Start with the roll-up. This is a strategy that’s been tried everywhere, and usually ends the same way: a buying spree, followed by integration whiplash. The parent company standardizes everything, key leaders walk, customers drift, and the “synergies” turn out to be mostly PowerPoint.

Quanta avoided that trap because it treated identity as an asset, not an inconvenience. Keeping a contractor’s brand, leadership, and customer relationships wasn’t a feel-good concession to founders. It was the whole point. In this business, trust is local and earned over years. If you break the human network that wins the work and runs the crews, you didn’t acquire a business—you acquired its equipment and a list of former customers.

The broader lesson is simple: roll-ups work when the parent actually makes the acquired companies stronger. Quanta brought capital, insurance scale, safety systems, purchasing power, and the ability to bid on bigger work—without smothering the operating company with bureaucracy. Just as important, it had the discipline to avoid standardizing for standardization’s sake.

Next: riding secular trends versus inventing them. Quanta didn’t create utility deregulation, renewables, or the AI-driven data center boom. But it positioned itself so that when those waves hit, it was already standing on the shoreline with crews, equipment, and customer relationships. That’s what good strategy often looks like in the real world: not predicting the future perfectly, but building a platform that benefits when structural shifts arrive.

Then there’s capital allocation, which is where cyclical industries make and break companies. Infrastructure spending comes in waves—utilities and energy customers surge, then pause, then surge again. Quanta’s advantage has been staying financially flexible: not overleveraging during good times, and keeping enough capacity to play offense when conditions turn. Downturns are when the best acquisitions tend to appear, because weaker competitors need an exit and stronger ones can buy quality at a reasonable price.

Quanta’s early “convergence” thesis is another useful takeaway. It saw that electric power, telecom, and pipeline infrastructure weren’t separate worlds—they overlapped physically and operationally, sharing rights-of-way, equipment, and field capabilities. Being present across those categories meant Quanta could follow investment wherever it went, and sometimes capture work at the intersections. Today’s version of that convergence is electrification meeting renewables meeting digital infrastructure. The companies that can serve that blended demand stand to win.

And finally, the question every contractor faces: how do you build a moat in a business where every project is bid and every customer can shop you tomorrow?

Quanta’s answer has been to create practical switching costs. Not contractual lock-in, but the kind that shows up in real decision-making: the ability to staff massive projects, a footprint that provides consistent execution across regions, safety performance that lowers customer risk, and long relationships that make the incumbent the least risky choice. None of those are unbreakable. But together, they tilt the playing field—especially when the work is complex and the stakes are high.

All of this only matters if you can survive long enough for it to compound. Quanta has been tested: the telecom crash, the 2008 financial crisis, and the COVID era. Each cycle reinforced the same operating truths—protect the balance sheet, stay flexible, don’t lose focus—and each time, the survivors tended to come out stronger as weaker competitors faded and customers consolidated work with contractors they trusted to endure.

X. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The case for Quanta ultimately comes down to a few big variables: how long the infrastructure spending wave lasts, how intense competition gets as more capital pours in, and whether Quanta can keep executing as projects get larger and timelines get tighter. You can look at the same facts and still land in different places depending on which risks you think dominate.

The Bull Case

The bullish argument starts with the idea that we’re not in a normal upcycle—we’re in the early innings of an infrastructure rebuild that has to happen.

America’s grid is old, stretched, and increasingly asked to do jobs it wasn’t designed for. Renewables add urgency, because the best wind and solar resources are often far from where people actually use electricity, which forces a buildout of long-distance transmission. Layer on the AI data center boom—big, fast-moving loads that need reliable power—and you have another demand shock hitting the system. And over the longer arc, EV adoption and broader electrification push demand higher still.

Any one of those trends would be enough to drive years of work. Together, they point to something closer to a multi-decade investment cycle—one where the limiting factor isn’t the willingness to spend, but the ability to get projects permitted, staffed, and built.

In that world, Quanta looks like one of the best-positioned enablers. It has national scale in a still-fragmented industry. It has long-standing relationships with utilities and developers. It has a skilled workforce that can’t be created overnight. And it has the balance sheet and operational depth to credibly bid, win, and deliver the mega-projects that smaller contractors simply can’t touch. The barriers to entry here—safety performance, specialized equipment, trained labor, and customer trust—aren’t theoretical. They’re the whole game.

Management’s outlook for 2025 and beyond reflects that momentum, calling for continued double-digit growth in revenue, adjusted EBITDA, and earnings per share. If Quanta can grow at that pace without giving back margins, the compounding effect is powerful.

The Bear Case

The bear case doesn’t deny the secular trends. It argues that the path from “needs to be built” to “gets built on schedule, at an acceptable return” is messy—and Quanta is still exposed to cycles and execution risk.

Start with cyclicality. Even with a long-term infrastructure tailwind, spending can pause. Higher interest rates can make utilities more cautious about capital programs, and a weaker economy can slow industrial work. Quanta’s own history is a reminder: in 2000 to 2002, a narrative that felt inevitable reversed quickly.

Then there’s the risk that comes with playing at the top end of the project spectrum. Mega-projects like SunZia are enormous, multi-year undertakings with plenty of ways to go wrong—labor availability, weather, supply chain disruption, permitting issues, design changes, and plain old execution mistakes. A serious delay or cost overrun on one flagship job can hit financial results and, just as importantly, reputation. Quanta’s recent track record has been strong, but the stakes rise with every larger contract it takes on.

Labor is another real constraint. The craft workforce Quanta depends on takes years to develop—training linemen, welders, and high-voltage specialists isn’t something you solve by hiring faster. In a tight labor market, wage inflation can squeeze margins. And if demand accelerates faster than the skilled workforce expands, the bottleneck becomes execution capacity, not opportunity.

Some risks are outside the company’s control. Permitting and regulatory timelines for major transmission can stretch for years. Political opposition, environmental challenges, or bureaucratic delays can stall projects indefinitely, regardless of how ready the contractor is to build.

Finally, there’s integration risk. Quanta has a long history of successful acquisitions, but the recent pace and breadth—Cupertino Electric, Sherman & Reilly, and the steel mill—raises the difficulty level. Even with a strong decentralized model, absorbing new businesses while maintaining safety, quality, and schedule discipline is a real operational test.

Competitive Analysis

One way to pressure-test Quanta’s position is to map the competitive dynamics using Porter’s Five Forces.

Threat of new entrants is low. Getting to Quanta’s scale requires years of investment in people, equipment, safety systems, and customer relationships. You can’t shortcut credibility in high-voltage, mission-critical work.

Bargaining power of suppliers is moderate. Quanta’s scale helps it negotiate, and its push into components and materials reduces dependence on outside suppliers for certain bottlenecks.

Bargaining power of buyers is moderate to high. Big utilities and developers can run competitive bids and have alternatives. But on the largest, most complex projects, the number of contractors that can truly execute shrinks fast—which improves Quanta’s position at the high end.

Threat of substitutes is low. Transmission lines, pipelines, and grid upgrades don’t have a digital substitute. The work has to be done in the physical world.

Competitive rivalry is moderate. There are other large contractors, but Quanta’s breadth and depth often put it in a category of its own for the most demanding work.

Another lens is Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, which helps explain where durability might come from.

Scale economies show up in shared services, purchasing power, insurance, and the ability to take on projects that smaller players can’t staff or finance.

Network effects are limited. This isn’t a business where each new customer automatically makes the product more valuable to other customers.

Counter-positioning may matter. Quanta’s decentralized model can be hard for others to copy without breaking the local leadership and culture that make contractor businesses work.

Switching costs come from qualification hurdles and trust. Utilities don’t casually rotate contractors on critical infrastructure, especially when safety performance and system familiarity matter.

Cornered resources include the skilled workforce and the operational leaders who know how to run this work at scale.

Process power shows up in the operating system: safety discipline, project management, and the ability to coordinate thousands of jobs without losing control.

Branding matters in the practical sense—reputation for safety and reliability reduces customer risk, and in this industry, reducing risk is worth real dollars.

Key Performance Indicators

For anyone tracking Quanta over time, three indicators tend to matter most.

First, backlog—both how it grows and what it’s made of. Backlog is future revenue already under contract, and the mix between steadier maintenance work and larger, longer-duration projects can tell you a lot about visibility and risk.

Second, the book-to-bill ratio—new awards relative to revenue recognized. Sustained performance above 1.0 generally signals growing demand and expanding backlog; sustained weakness can be an early warning sign.

Third, segment margins. Quanta’s profitability varies across its business lines, and margin trends are a window into pricing discipline, labor pressure, and whether execution is keeping up as the company scales.

XI. Epilogue & Looking Forward

In recent communications, Quanta’s leadership has described the company’s moment in big, sweeping language: demand for power and infrastructure solutions is accelerating, the whole industry is being reshaped, and Quanta intends to be at the center of it—as a critical partner building the future of energy and technology.

This isn’t just corporate chest-thumping. The forces pushing infrastructure investment—grid modernization, renewable buildout, AI-driven data centers, and electrification—are tangible, and they don’t look temporary. The more interesting question isn’t whether capital will flow into infrastructure. It’s who can actually turn that spending into completed projects, safely and on time, and what returns they can earn while doing it.

The next decade will test whether Quanta can keep the quality bar high while operating at a pace the industry isn’t used to. Growing this fast in a craft business isn’t like adding servers. It means recruiting, training, and retaining skilled labor. It means scaling project management without losing field-level accountability. And it means making sure the decentralized model—so effective at preserving local relationships and operator ownership—doesn’t strain under the weight of bigger projects, more geographies, and more moving parts.

Competition will matter, too. Other large contractors see the same opportunity and will push to grow into it. Utilities and developers may decide they don’t want to concentrate too much work with any single provider, even a trusted one. And as construction methods and tools evolve, it’s possible that new competitors—from adjacent industries with different capabilities—enter parts of the market.

If you were running Quanta today, the priorities would be straightforward, and brutally hard to execute: keep delivering mega-projects with the reliability that built the brand; invest heavily in workforce development so labor capacity doesn’t become the ceiling; protect the cultural balance between local autonomy and corporate support that makes the acquisition model work; and stay financially disciplined, even when the pipeline of opportunity makes it tempting to chase everything.

For operators, Quanta is proof that “infrastructure” doesn’t have to mean slow, unglamorous value creation. In the right structure, with the right timing and execution, a craft-based business can compound in a way that looks almost unbelievable—because the work becomes more essential as the world changes.

For investors, the questions are the classics: how durable is the moat, how cyclical is the demand really, and can execution keep up as project size and complexity rise? Quanta’s run has been defined by showing up to the right wave with the right capabilities—and then scaling faster than everyone else. Whether it keeps doing that will depend on choices inside the company and constraints outside it.

Out on that Arizona desert job site, the crew stringing wire between transmission towers in brutal heat probably isn’t thinking about AI or the energy transition in abstract terms. They’re thinking about clearances, weather, safety, and whether today’s work gets finished the right way. But multiplied across thousands of similar sites, that day-by-day execution is what becomes the infrastructure that powers whatever comes next.

That’s what Quanta does, and has always done. The scale has changed. The projects are bigger. The stakes are higher. But the work is still the same at its core: skilled people, working safely, building the systems modern life depends on.

XII. Recent News

Quanta keeps stacking up contract wins and making strategic moves as demand for energy and grid infrastructure keeps accelerating. The most useful way to track what’s changing, quarter to quarter, is to watch three things: progress on the company’s biggest projects, any new acquisitions that expand capabilities or capacity, and whether management raises or narrows its guidance as conditions evolve.

If you want the clearest read on all of that, it usually shows up in the quarterly earnings calls—where Quanta tends to get specific about what customers are funding, what’s getting delayed, and where execution risk is rising or falling.

XIII. Links & Resources

Primary Sources: - Quanta Services SEC filings (10-K annual reports, 10-Q quarterly reports, 8-K current reports) - Quanta Services Investor Relations website - Quanta Services earnings call transcripts

Industry Resources: - U.S. Department of Energy Grid Modernization Initiative - Federal Energy Regulatory Commission transmission project filings - Edison Electric Institute infrastructure investment reports

Further Reading: - Reporting on the SunZia transmission project in energy industry publications - Analysis of data center power demand from hyperscale operators - Historical coverage of consolidation in the electrical contracting industry

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music