Regeneron Pharmaceuticals: The Science-Driven Biotech That Became a Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Framework

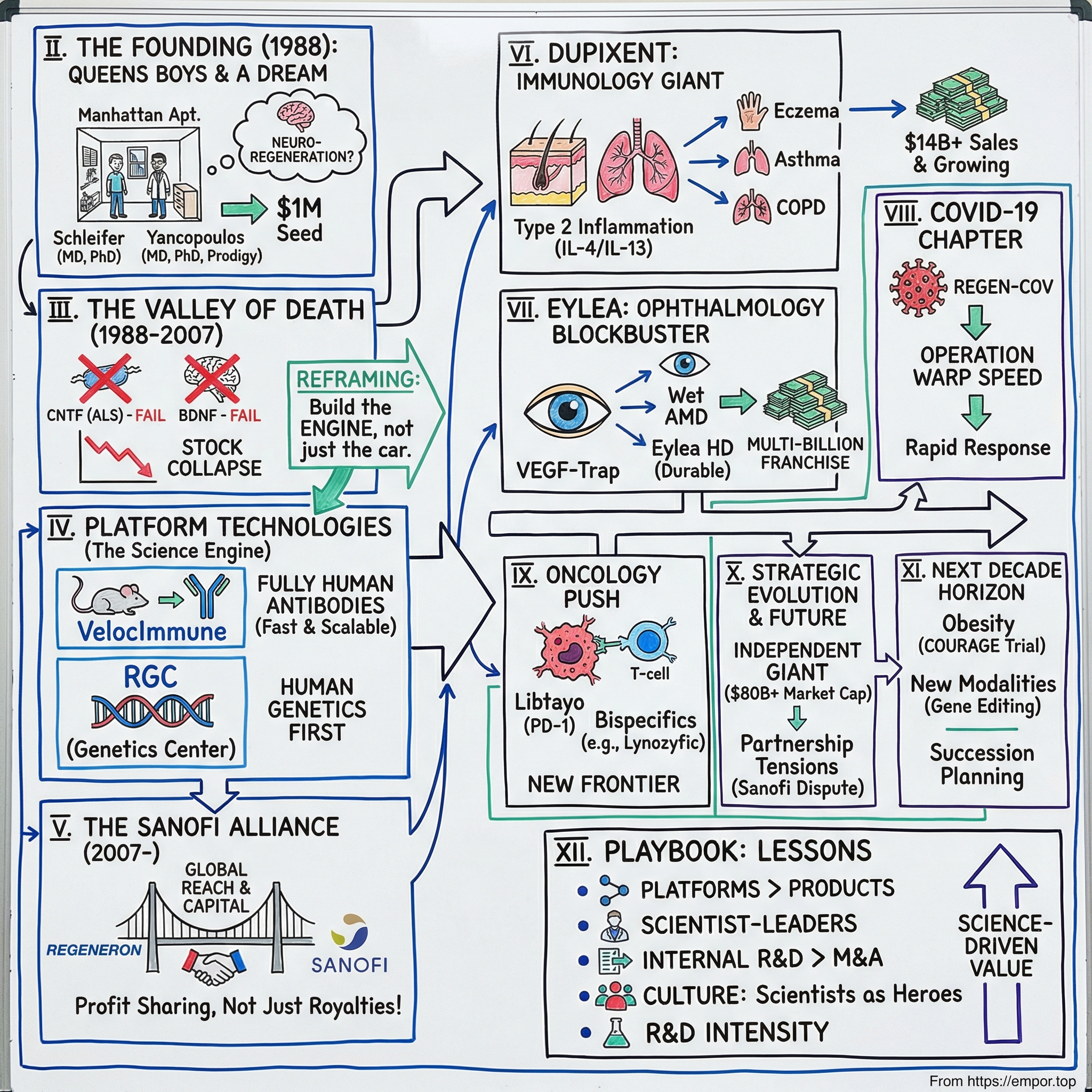

Picture a cramped Manhattan apartment in 1988. Leonard Schleifer, a 35-year-old physician-scientist, has just walked away from his professor job at Weill Cornell to start a biotech company. He has about $1 million in seed money, a name that sounds like science fiction, and a conviction that medicine is about to be reinvented.

To the outside world, it looks like career suicide. Big Pharma is a fortress—Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson—companies with global sales forces, deep pockets, and decades of institutional muscle. The idea that a neurologist from Queens could build a company to compete in that arena feels, at best, wildly optimistic.

Jump to early 2026, and Regeneron stands as one of biotech’s most improbable giants. It has grown into a business with more than $14 billion in annual revenue, a market cap north of $80 billion, and multiple blockbuster medicines—drugs that changed standards of care in eye disease and inflammatory conditions, and that briefly became household names during COVID-19.

But the detail that really separates Regeneron from the rest of the biotech hall of fame is this: it didn’t become huge by buying innovation. Unlike most large biotechs, where the biggest products often come from acquisitions or in-licensed molecules, almost everything that matters at Regeneron was invented inside its own labs in Tarrytown, New York.

So how did that happen? How did two physician-scientists from Queens—Leonard Schleifer and George Yancopoulos—build a company that not only survived biotech’s brutal odds, but did it while keeping discovery in-house? How did they make it through two Phase III failures that could’ve ended the story? And how did they create platform technologies so valuable that a French pharma giant paid billions for the privilege of using them?

This is a story about a company that treated science as the strategy. About putting researchers at the center of the organization, not as a cost line to be managed, but as the engine of everything. It’s about partnerships—structured carefully enough to fund ambition without surrendering control. It’s about two decades of grinding through the “valley of death” before the world saw the payoff.

The central question we’ll keep coming back to is simple: in an industry where most drugs fail and most biotechs run out of money, how did Regeneron not only survive, but compound success into a repeatable machine? The answer sits at the intersection of culture, platforms, and an almost stubborn refusal to become “just another pharmaceutical company.”

II. The Founding Story: Two Scientists from Queens

The story starts with a neurologist watching medicine come up short.

Leonard Schleifer was building a strong academic career at Weill Cornell, studying the neurons that control breathing. But in the clinic, he kept meeting the same brick wall: Parkinson’s, ALS, Alzheimer’s—diseases where doctors could diagnose, monitor, and comfort… but rarely change the outcome. Meanwhile, the labs were exploding with discovery. The gap between what science seemed to be learning and what patients could actually receive started to feel unbearable.

Schleifer didn’t look like a future corporate titan. He grew up in Queens, New York. His father was a sweater manufacturer and a World War II codebreaker. The family didn’t have money, but they treated education like a non-negotiable. Schleifer earned his undergraduate degree at Cornell University, then went on to an MD-PhD at the University of Virginia, where he trained under Alfred G. Gilman, who would later win the Nobel Prize for his work on G-proteins. Still, academic medicine wasn’t giving Schleifer the thing he wanted most: a direct line from discovery to real treatments.

In the mid-1980s, he became obsessed with what was happening 3,000 miles away. Genentech—founded less than a decade earlier—was proving that small biotech companies could do something that used to require a pharmaceutical empire: make important drugs. Recombinant DNA had already delivered human insulin and synthetic human growth hormone, and the industry’s center of gravity was visibly shifting.

But Schleifer noticed a glaring absence. None of the pioneering biotechs were taking on neurological disease—his world, and arguably the biggest, messiest set of unmet needs in medicine.

His leap was simple, and radical: if Genentech could marry molecular biology to endocrinology, why couldn’t someone do the same for neurology?

The brain was more complex, sure. But neuroscientists were uncovering fundamental rules of how nerves grow, survive, and die. And a new class of proteins—neurotrophic factors, molecules that promote nerve cell survival and growth—seemed, for a moment, like the missing lever. If you could deliver the right factors, maybe you could keep neurons alive. Maybe even restore function. Maybe “degenerative” didn’t have to mean “inevitable.”

So in 1988, Schleifer started Regeneron. He rented an office in a Manhattan apartment building and persuaded George Sing, a venture capitalist at Merrill Lynch, to back the idea with $1 million in seed funding. He stacked the scientific advisory board with three Nobel Laureates—instant credibility for a company that, otherwise, was little more than ambition and a lease.

But Schleifer still needed the other half of the equation: a scientist who could turn frontier neuroscience into actual drug candidates. Not a hired gun. A true architect.

That person was George Yancopoulos.

Yancopoulos was another Queens kid—Woodside, specifically—the son of Greek immigrants. His father, Damis George Yancopoulos, bounced through jobs like furrier and insurance salesman, while his mother ran the household and made academic excellence the family’s north star. George delivered. He went to the Bronx High School of Science and graduated valedictorian. Then he went to Columbia University and did it again—valedictorian again.

At Columbia’s College of Physicians & Surgeons, he pursued both an MD and a PhD, doing doctoral work under the renowned geneticist Fred Alt. His research on immunology and antibody diversity would become so influential that, in the 1990s, he was ranked the eleventh most highly cited scientist in the world—and notably, the only one on that list working in industry rather than academia.

Schleifer and Yancopoulos were a perfect mismatch in the way great founding pairs often are: one was a driven physician-entrepreneur with a problem to solve, the other a scientific prodigy with the ability to build entirely new tools. Two ambitious sons of Queens, seeing the same future.

But before Yancopoulos would bet his career on a startup no one had heard of, there was one more gatekeeper: his father.

Damis insisted on meeting Schleifer himself. He had his own template for what a Greek-American scientist could become: P. Roy Vagelos, another son of Greek immigrants who rose from academic research to become CEO of Merck—at the time, the most admired pharmaceutical company in the world. If George was leaving academia, it had to be for a path that could plausibly lead to that kind of impact.

Schleifer got the meeting. He passed the interview. And in 1989, George Yancopoulos joined Regeneron as its scientific architect.

Even the company’s name told you what they were betting on. “Regeneron” was a nod to regeneration—the hope that neurotrophic factors could revive damaged nerve cells and, with them, the lives of patients. It was an audacious first mission, in one of the hardest domains in all of medicine, taken on by two young physician-scientists with far more conviction than track record.

From the beginning, they set out to build a different kind of biotech. At most pharma companies, science ultimately reports to business. At Regeneron, science would be the business. The company would be led by physician-scientists. Basic research wouldn’t be treated as a luxury. Scientists would be the heroes, not the back office. And everyone—bench to boardroom—would be pointed at the same endpoint: helping patients.

That philosophy would get stress-tested for years. What no one could see in 1989 was that the regenerative dream that gave Regeneron its name would eventually collapse—and that the company’s greatest successes would come from technologies that didn’t even exist when Schleifer signed that first lease in Manhattan.

The Queens boys were heading straight into biotech’s valley of death.

III. Early Years: The Valley of Death (1988-2007)

The neurotrophic factor idea was clean, elegant, and—on paper—almost irresistible.

During development, the nervous system produces more neurons than it will ever keep. Then nature runs a ruthless selection process: neurons compete for scarce survival signals, called growth factors. Get enough of the factor, you live. Miss out, you die—by design. Regeneron’s bet was that neurodegenerative diseases like ALS or Parkinson’s were, in part, that same process gone wrong. So what if you could flood the system with the right growth factor and pull neurons back from the brink?

In the lab, the story looked phenomenal. Regeneron poured its early years into two candidates: brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF, and ciliary neurotrophic factor, CNTF. In animal models and dish experiments, they seemed to protect neurons and even help regenerate connections. The papers were thrilling. The biology felt like destiny.

Then the company hit the part of biotech that doesn’t care about beautiful hypotheses: humans.

CNTF was first to run into the wall. Regeneron pushed it into Phase III for ALS—Lou Gehrig’s disease—one of the most unforgiving diagnoses in medicine. ALS progressively kills motor neurons. Patients often remain mentally sharp while losing the ability to move, speak, swallow, and breathe, with life expectancy commonly only a few years after diagnosis. If CNTF worked, it would be genuinely transformational.

The pivotal ACTS trial enrolled 730 patients. And the readout was brutal: no statistically significant difference versus placebo. The molecule that looked like a savior in preclinical work didn’t move the needle in people. Regeneron laid off about a quarter of its workforce. The stock collapsed. Analysts started writing the kind of notes that sound like eulogies.

Worse, the next test was the one that mattered most inside the building.

BDNF wasn’t just another program. It was the flagship—the neurotrophic factor with the strongest rationale, the one that represented what Regeneron had been founded to do. If it failed, it wasn’t just a product failure. It was an identity crisis.

BDNF failed too. When the results became public, Regeneron’s stock dropped 43% in a single day. Two late-stage defeats. The company’s core thesis in shambles. The outside verdict was straightforward: it was over.

For most biotechs, it would’ve been. Two Phase III failures can erase years of credibility, capital, and morale in a week. There’s a common playbook at that moment: cut science, bring in operators, pivot into whatever investors want to hear.

Regeneron did something different. Schleifer and Yancopoulos didn’t replace the scientists. They kept them—and tried to learn their way out.

The postmortem was sobering. The proteins didn’t get where they needed to go. They couldn’t cross the blood-brain barrier effectively. They were cleared too quickly. The doses that were safe weren’t enough to deliver a meaningful therapeutic effect. The biology might have been real, but the treatment wasn’t.

And then came the crucial reframing: even if the neurotrophic factor dream was collapsing, the company had built real capabilities along the way—molecular tools, experimental systems, and a team trained to chase hard biology. Those assets could be pointed elsewhere.

By 1997, even as the neurotrophic programs were falling apart, Yancopoulos and his group had started shifting toward a new opportunity: antibodies.

Antibodies are the immune system’s precision instruments—proteins evolved to bind targets with extreme specificity. If you can make therapeutic antibodies, you can design drugs that latch onto disease-driving molecules and shut them down. The promise wasn’t just a new product. It was a new way of building products.

But antibodies had their own problem. The standard approach at the time was messy and slow. Many antibody drugs started as mouse antibodies, which then had to be “humanized”—a painstaking, bespoke engineering process to reduce the chance the human immune system would reject them. It worked, sometimes. But it didn’t scale like an engine.

Yancopoulos proposed a cleaner solution: don’t humanize mouse antibodies. Build mice that make fully human antibodies in the first place.

The concept was deceptively simple. The execution was anything but. To pull it off, Regeneron would have to re-engineer key parts of the mouse immune system’s genetic code—swapping in human antibody sequences—while preserving normal immune function. The animals had to stay healthy, mount real immune responses, and reliably generate fully human antibodies against whatever target you introduced.

That technology became VelocImmune. It took years of patient, unglamorous genetic engineering. But the payoff was profound: instead of crafting each antibody by hand, Regeneron could industrialize antibody creation. By 2006, the first fully human antibody made through VelocImmune entered clinical development.

If you’re counting, that’s nearly two decades after the company was founded.

From 1988 to 2006, Regeneron lived in what investors call the “show-me” zone: lots of scientific promise, no products, constant cash burn, and an unforgiving market that doesn’t fund patience forever. The company’s first FDA approval—Arcalyst, for a rare autoimmune disorder—wouldn’t arrive until 2008. For most of this stretch, Regeneron was surviving, not winning.

But here’s the twist: the wilderness years weren’t wasted. They created the thing that would eventually make Regeneron exceptional.

VelocImmune would become the foundation for drugs like Dupixent and Praluent, and a pipeline that could keep producing shots on goal. Meanwhile, another thread of research—into how blood vessels form—led to the VEGF-trap technology that would become Eylea, a blockbuster in ophthalmology. The early failures didn’t just toughen the company up; they forced it to build platforms, not one-off miracles.

And they forged a culture that’s hard to fake. Companies that win early often develop swagger. Companies that almost die, repeatedly, tend to develop discipline. Regeneron’s scientists learned the harsh gap between lab success and patient benefit. They learned that clinical trials humble everyone. And they learned persistence—the kind that matters more than brilliance when the data comes back and doesn’t care what you hoped would be true.

Regeneron hadn’t reached the promised land yet. But it had built the engine that would eventually get it there.

IV. The Sanofi Alliance: A Game-Changing Partnership (2007-2017)

By late 2007, Regeneron finally had what Big Pharma craves: a repeatable way to make drugs.

VelocImmune—and the broader VelociSuite of technologies around it—meant Regeneron could generate fully human antibodies faster and more reliably than the industry’s usual, painstaking process. But there was still a hard truth lurking behind the science: discovery alone doesn’t get medicines into millions of patients. Global trials, regulatory muscle, manufacturing at scale, worldwide commercialization—Regeneron wasn’t built for that yet.

They needed a partner. And they found one in Sanofi-Aventis.

On November 29, 2007, the two companies announced a sweeping, global collaboration to discover, develop, and commercialize fully human therapeutic antibodies using Regeneron’s platform. The roles were cleanly divided. Sanofi would bring capital, development horsepower, and a worldwide commercial footprint. Regeneron would bring the engine that could keep producing shots on goal.

The terms made it clear how highly Sanofi valued that engine. Sanofi paid $85 million upfront and committed up to $475 million in research funding over five years, with the potential for another $250 million in sales milestone payments if products hit certain revenue thresholds. And then came the move that mattered strategically: Sanofi boosted its ownership in Regeneron from roughly 4% to about 19% by buying 12 million newly issued shares at $26 per share.

Just as important as the money was the structure. This wasn’t a typical “big company owns the program” arrangement. Schleifer and Yancopoulos negotiated profit-sharing that let Regeneron keep real upside: 50% of U.S. profits on collaboration products. Outside the U.S., profits would be split on a sliding scale that favored Sanofi, reflecting Sanofi’s lead role in international commercialization. The deal gave Regeneron financial oxygen without turning it into a captive R&D shop.

And it worked—quickly.

Within a few years, the alliance had pushed four antibodies into clinical development and lined up a fifth behind them. The targets spanned very different diseases: the interleukin-6 receptor for rheumatoid arthritis, nerve growth factor for pain, and Delta-like Ligand 4 for cancer. That breadth was the point. Regeneron wasn’t just proving it could produce one good antibody. It was proving it had built a platform.

In 2010, the two companies doubled down. Sanofi increased its annual funding commitment from $100 million to $160 million starting that year, extending the collaboration through at least 2017. The bet wasn’t only on the molecules. It was on the way Regeneron operated—deeply science-led, but with hard-earned respect for what clinical failure looks like and what it takes to build real medicines.

Then, inside this flood of targets and trial starts, one program began to separate from the pack: dupilumab, an antibody targeting the interleukin-4 receptor.

At the time, the biology looked sensible—IL-4 and IL-13 were known drivers of allergic inflammation—but the initial focus, atopic dermatitis, didn’t scream “blockbuster.” Dermatology was not where people expected a biotech revolution. Severe eczema was treated with a patchwork of topical steroids and other symptomatic fixes, and the category wasn’t considered a glamorous frontier.

But dupilumab would become Dupixent. And Dupixent would go on to reshape immunology—showing efficacy not just in atopic dermatitis, but across asthma, nasal polyps, and eosinophilic esophagitis, and later earning approval in September 2024 for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults with an eosinophilic phenotype. What looked like a straightforward allergy antibody became something far bigger: a product that kept expanding into new diseases, like a pipeline hiding inside a single molecule.

The original antibody discovery collaboration ran through its planned endpoint. On December 31, 2017, Regeneron stated simply that the discovery agreement with Sanofi would end without extension.

By then, the balance of power had changed. Regeneron wasn’t a scrappy platform company looking for validation anymore. Dupixent was on its way up. Eylea was already a multibillion-dollar franchise. Regeneron had the resources to stand on its own in many areas. And yet, the relationship with Sanofi didn’t fade away—because Dupixent was too important, too intertwined. The partnership would remain the foundation of a massive business, and eventually, a source of tension as both sides fought over control, visibility, and economics.

Still, looking back, the Sanofi decade did something even bigger than fund a few programs. It validated Schleifer and Yancopoulos’s core thesis: that a biotech could keep discovery at the center, build a platform that compounds, and partner with Big Pharma without surrendering its identity. In an industry where partnerships often end with the smaller company being absorbed, this one became a blueprint for staying independent—while using scale as leverage instead of a trap.

V. The Dupixent Revolution: Creating a Multi-Billion Dollar Franchise

In the early Dupixent trials, one patient had lived with atopic dermatitis for decades. Her skin was chronically inflamed—cracked, raw, sometimes bleeding. She’d cycled through the standard arsenal: topical steroids, systemic immunosuppressants, anything a specialist could reasonably throw at severe eczema. Nothing really held. The disease didn’t just sit on the surface; it ran her life. The itching. The stares. The nights spent awake, scratching until she couldn’t.

Then she got her first injection of dupilumab. And for everyone watching—patient, doctors, Regeneron, Sanofi—there was no guarantee this would be different.

But it was. Within weeks, her skin began to clear. The inflammation fell away. The itching quieted. And something that sounds small until you’ve lost it: she slept through the night.

Across the Phase II program, investigators started seeing versions of that story again and again. Not incremental improvement. Not “maybe this helps.” Dramatic responses that were hard to miss, even in a field where people had learned not to get their hopes up.

Dupixent worked because it went after the core wiring of what’s known as Type 2 inflammation—the immune program that sits underneath many allergic diseases. Broadly speaking, the immune system deploys different “modes” depending on the threat. Type 1 responses are built to fight bacteria and viruses. Type 2 responses evolved for parasites, like worms. The problem is that in modern, parasite-free environments, that Type 2 machinery can misfire. It starts reacting to harmless triggers—dust mites, pollen, foods—and the result is the spectrum of atopic disease: eczema, asthma, and more.

Two signaling proteins, interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, are central to this system. They act like master switches, driving the downstream effects patients actually feel: itch, inflammation, mucus, tissue remodeling.

Most older treatments didn’t distinguish between good immune function and bad. Steroids and other immunosuppressants can calm symptoms, but they do it by pressing down on the immune system broadly, which can leave patients more vulnerable to infection and other complications—especially with long-term use.

Dupixent took a different approach. It blocked the IL-4 receptor alpha chain, a shared component both IL-4 and IL-13 need to signal. That one decision—hit the shared receptor instead of chasing each cytokine separately—let Dupixent dial down the pathological Type 2 response while preserving other immune pathways.

And that precision showed up where it mattered most: safety. Instead of the “works, but at a price” tradeoff that’s haunted immunology for decades, Dupixent proved remarkably tolerable for long-term use. Patients could stay on it for years without accumulating the toxicities that made older systemic therapies so fraught. That combination—striking efficacy plus a clean safety profile—set the stage for everything that followed.

In March 2017, the FDA approved Dupixent for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. For Regeneron, it was a long-delayed vindication: nearly three decades after founding, and about two decades after the neurotrophic factor failures that nearly ended the company. The launch wasn’t an overnight sensation in pure sales terms—no drug is, at first—but the clinical impact was obvious to dermatologists, and adoption accelerated as word spread: this was the first treatment in a long time that consistently changed patients’ lives.

By the end of 2019, Dupixent had become a major product, generating $2.5 billion in annual global sales.

But the real engine wasn’t just dermatology. It was expansion.

Because Dupixent targeted a fundamental pathway, it wasn’t a one-disease drug. The same IL-4 and IL-13 biology that drives severe eczema shows up across a wider Type 2 landscape—especially in respiratory disease. That meant each successful trial wasn’t merely “line extension.” It was proof that the molecule could travel.

The asthma approval arrived in October 2018. Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps followed in June 2019. Eosinophilic esophagitis came in May 2022. And then, in September 2024, the franchise crossed a psychological boundary: Dupixent received FDA approval as an add-on maintenance treatment for adults with inadequately controlled COPD and an eosinophilic phenotype—the first biologic ever approved for that COPD population.

That COPD decision mattered not just because it was another label. COPD is one of the largest, most burdensome respiratory diseases in the world. Standard therapies—bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids—can help symptoms, but they don’t fundamentally rewrite the trajectory for many patients. Dupixent offered a new strategy: target the underlying inflammation in the subset of COPD patients whose disease is driven by eosinophilic biology.

The business results followed the medicine.

In full-year 2024, Dupixent global net sales (recorded by Sanofi) reached $14.15 billion, up 22% versus 2023. By full-year 2025, that climbed to approximately $17.8 billion, a 26% increase. By that point, Dupixent had become the most widely used innovative branded antibody medicine in the world, with more than 1.4 million active patients globally.

What’s unusual is how those sales show up on paper.

Sanofi leads global commercialization and records Dupixent sales on its income statement. In the United States, profits are split 50/50 between Sanofi and Regeneron. Outside the U.S., Regeneron receives mid-teens royalties on net sales. The model gives Regeneron enormous economics—without requiring it to build a full global commercial machine for every market—while Sanofi gets what large-pharma investors love: reported revenue scale and broad patient reach.

But the closer a partnership gets to printing money, the more every detail matters. And Dupixent eventually brought that reality to the surface.

In November 2024, Regeneron sued Sanofi, alleging its marketing partner violated terms of the Dupixent collaboration by failing to provide full access to sales materials, including contracts with pharmacy benefit managers, payers, and specialty pharmacies. Regeneron said Sanofi had “stonewalled” repeated requests for full access to PBM agreements, and alleged the issue was tied to bundling arrangements involving other Sanofi immunology products.

The dispute illuminated the core friction point in shared-economics deals. When profits are split, each partner effectively pays for half of the rebates and discounts negotiated with payers. Regeneron argued it was entitled to transparency into how those concessions were being traded—especially if Dupixent discounts were being used to benefit products Regeneron didn’t share in. As of early 2026, the litigation was still ongoing, adding a layer of uncertainty to one of the most lucrative collaborations in biotech.

Even with that backdrop, the runway remained long. Analysts projected Dupixent could surpass $22 billion in annual sales by the end of the decade. More indications were moving through regulators, including allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, with an FDA decision date in February 2026, and bullous pemphigoid, with a European decision expected in the first half of 2026.

Zoom out, and the Dupixent arc is a master class in how drug value is really created. Start with fundamental biology. Build a selective mechanism that patients can stay on. Prove it in one major disease. Then expand methodically across every adjacent condition that shares the same underlying pathway.

What began as an eczema drug became something much bigger: a Type 2 inflammation franchise that reshaped dermatology, respiratory medicine, and gastroenterology—and turned Regeneron’s platform-first philosophy into one of the most valuable products in modern biotech.

VI. Eylea: The Ophthalmology Blockbuster

An elderly patient noticed a dark spot creeping into the center of her vision. Reading became a strain. Faces looked smudged. When she finally saw a specialist, the diagnosis landed with a thud: wet age-related macular degeneration.

In wet AMD, abnormal blood vessels grow beneath the retina and leak fluid, damaging the tissue responsible for sharp, central vision. Left untreated, patients can lose meaningful sight frighteningly fast. Not long ago, that decline was close to inevitable. AMD was the leading cause of blindness in people over sixty-five, and ophthalmologists had little to offer beyond coping tools.

Then anti-VEGF therapy changed everything.

VEGF—vascular endothelial growth factor—is one of the body’s key “build blood vessels” signals. That’s useful when you’re healing a wound. In the retina, in diseases like wet AMD and diabetic eye disease, it’s a disaster. Too much VEGF triggers fragile, leaky vessels in exactly the wrong place. Stop VEGF, and you can often stop the bleeding and swelling—and sometimes even claw vision back.

Regeneron’s path into ophthalmology didn’t come from its antibody platform. It came from a different piece of biology, built into a different kind of molecule: the VEGF-trap.

Working with Sanofi-Aventis—later shifting ophthalmology commercialization outside the U.S. to Bayer—Regeneron developed aflibercept. Unlike a standard antibody that simply binds VEGF, aflibercept was engineered as a fusion protein: a decoy receptor made from pieces of two VEGF receptors stitched together. The idea was to mimic the body’s natural VEGF-binding sites, but make them better. If VEGF was the key, aflibercept was designed to be the lock that grabs it first and holds on.

The practical payoff was binding strength and durability in the eye. It wasn’t just “another anti-VEGF.” It was a different architecture built for the job.

That mattered because Regeneron was walking into a market that already had winners.

Genentech’s Lucentis had established anti-VEGF therapy as the standard of care and was doing billions in sales. And then there was Avastin, Genentech’s cancer drug that doctors discovered worked nearly as well for eye disease when split into tiny, repackaged doses—at a fraction of the cost. Off-label Avastin created a permanent shadow over the category: any new entrant had to justify why it deserved premium pricing.

In November 2011, the FDA approved aflibercept—branded as Eylea—for wet AMD. It launched into the teeth of Lucentis and the Avastin workaround. And yet, Eylea’s advantage became obvious in the way that matters most in medicine: it made life easier while keeping outcomes strong.

Clinical data showed Eylea could match Lucentis’s vision results with less frequent dosing—every eight weeks instead of monthly injections after the initial loading period. For patients, that meant fewer needles in the eye. For caregivers, fewer trips. For retina clinics, a different rhythm of care. In a chronic disease where treatment can stretch for years, convenience isn’t cosmetic. It’s adherence, outcomes, and quality of life.

Eylea’s adoption was fast, and the franchise broadened. Beyond wet AMD, it expanded into diabetic macular edema, diabetic retinopathy, and macular edema following retinal vein occlusion. By 2022, Regeneron was reporting record revenue for Eylea alongside Dupixent—a one-two punch that turned the company into a cash-generating machine and helped fund a much bigger R&D ambition.

Structurally, Eylea also gave Regeneron something it didn’t fully have with Dupixent: control.

Bayer handled commercialization outside the U.S., but in the United States, Regeneron recorded Eylea sales directly and kept the bulk of the economics. Bayer earned milestone payments and royalties internationally. It was a global partnership, but it didn’t dilute Regeneron’s ownership of the core franchise in its most important market.

Then the clock ran out—because in pharma, it always does.

Eylea’s patents began expiring in 2024. Biosimilars followed. The FDA approved multiple aflibercept biosimilars in 2024 and 2025, including interchangeable versions from Biocon Biologics and Samsung Bioepis. Once you have true substitutes, the game shifts from “best product wins” to “how much share can you defend, and at what price.”

Regeneron’s answer was a classic lifecycle move, executed with real technical substance: Eylea HD.

Approved in August 2023, Eylea HD was a higher-dose formulation—8 mg of aflibercept versus 2 mg in standard Eylea. The goal wasn’t just more drug for the sake of it. It was time. If patients could go longer between injections without losing efficacy, that convenience would be compelling enough to keep many of them on the branded franchise even as cheaper biosimilars arrived.

The PULSAR and PHOTON trials supported the strategy, showing that Eylea HD could maintain vision outcomes with dosing intervals that could extend as far as every 16 weeks for appropriate patients. In the real world, that kind of reduction in treatment burden can be the difference between “I can stick with this” and “I can’t keep doing this.”

By full-year 2025, the transition was showing up in the numbers. Eylea HD U.S. net sales reached $1.6 billion, up 36% versus 2024. And while biosimilars were now in the market, total U.S. net sales for the combined Eylea franchise stayed relatively stable—evidence that Eylea HD was doing what it was designed to do: protect the economics by upgrading the product.

Fourth quarter 2024 U.S. net sales for Eylea HD and Eylea together totaled $1.50 billion, including $305 million from Eylea HD.

Zoom out, and Eylea is a case study in how a biotech graduates into a durable pharma business.

First, it shows the power of being meaningfully better in a specialty market—especially when “better” translates to fewer procedures and fewer appointments. Second, it shows that even when patents expire, incumbents aren’t helpless; improved formulations can shift the battlefield. And third, it highlights why ophthalmology is such an attractive arena: a concentrated prescriber base of retina specialists, a clear treatment paradigm, and outcomes patients can actually feel.

Now, the franchise faces its most serious test. Biosimilar pressure is real and will intensify as more entrants arrive. Regeneron’s defense depends on how quickly Eylea HD becomes the default, how aggressively biosimilars compete, and whether further improvements keep widening the convenience gap (including a prefilled syringe version that was expected in 2026).

The drug that helped fund Regeneron’s transformation is no longer just a blockbuster. It’s a fortress under siege—and a live demonstration of whether Regeneron can defend a franchise the way it once built one.

VII. The COVID-19 Chapter: REGEN-COV and Operation Warp Speed

When early reports began leaking out of Wuhan in 2020—an unusual pneumonia, a new coronavirus—Regeneron didn’t treat it like just another headline. Inside the company, it looked like the kind of scenario they’d been quietly preparing for.

Back in October 2017, years before anyone had heard the term “SARS‑CoV‑2,” Regeneron struck a deal with the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, BARDA. The logic was straightforward: the U.S. government would cover 80% of the cost to develop and manufacture antibody-based medicines for emerging infectious diseases, and Regeneron would keep control of production and pricing.

At the time, that sounded like abstract preparedness. In 2020, it became one of the most consequential public-private arrangements of the pandemic era.

Once the virus’s genetic sequence was published, Regeneron moved with the confidence of a company that already had the machine built. Using VelocImmune, its scientists generated thousands of potential antibodies in a matter of weeks. The workflow was brutally practical: expose humanized mice to the SARS‑CoV‑2 spike protein, harvest the antibodies their immune systems produced, then rapidly screen for the ones that neutralized the virus most effectively. What normally took years could happen in months—because the platform wasn’t being invented in real time. It was already there.

By summer 2020, Regeneron had narrowed the field to a two-antibody combination: casirivimab and imdevimab. The “cocktail” design wasn’t marketing flair. It was a hedge against evolution. Each antibody bound to a different, non-overlapping region of the spike protein, so if the virus mutated to escape one, the other could still land its punch. In a pandemic caused by a rapidly replicating virus, that kind of redundancy was the difference between “promising” and “usable.”

Then came the government’s bet.

In July 2020, under Operation Warp Speed, Regeneron received a $450 million contract to manufacture and supply its experimental therapy—then called REGN‑COV2—even as clinical trials were still underway. The U.S. government pre-purchased 300,000 doses. It was an extraordinary level of conviction, not just in the science, but in Regeneron’s ability to manufacture at scale under crisis conditions.

The moment the public remembers came a few months later.

In October 2020, President Donald Trump tested positive for COVID‑19 and was admitted to Walter Reed. His doctors administered REGN‑COV2 under compassionate use—an emergency pathway that allows access to an experimental therapy outside trials. Trump recovered quickly and went on to praise the treatment publicly, calling it a “cure” in a White House video.

For Regeneron, the attention was immediate and global—and also messy. The treatment became tangled in the politics of 2020. Awareness soared, but so did controversy, and the drug’s reputation inevitably picked up partisan baggage that no clinical dataset can fully scrub off.

On November 21, 2020, the FDA granted emergency use authorization for REGN‑COV2—now renamed REGEN‑COV—for high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID‑19. The fine print mattered: the therapy was meant for patients early in infection, before hospitalization or oxygen requirement. That’s when antibodies can still do their job—neutralize the virus before the disease becomes less about viral replication and more about the body’s inflammatory overreaction. In severe, late-stage illness, the benefit was much more limited.

Regeneron scaled manufacturing aggressively. By the end of November 2020, it had produced about 80,000 doses, increased that to 200,000 by early January 2021, and reached 300,000 by the end of that month. Facilities in Tarrytown and a network of manufacturing partners ran at full tilt to meet demand.

And then the virus changed the rules.

Variants arrived in waves—Alpha, then Delta, then Omicron—and the advantage of a precisely targeted biologic became its vulnerability. REGEN‑COV had been designed against the original Wuhan strain. As the spike protein accumulated mutations, binding weakened. By January 2022, with Omicron dominant in the U.S., the FDA revised REGEN‑COV’s authorization to effectively sideline it against that variant. The drug that had looked like a defining therapeutic tool early in the pandemic had been outmaneuvered by viral evolution.

The business story whipsawed with the science. REGEN‑COV generated major revenue in 2020 and 2021, then dropped sharply as susceptibility vanished and demand dried up. Regeneron had built and expanded manufacturing capacity at enormous expense—and suddenly that capacity wasn’t needed. Pandemic response had forced them to build for the peak, and when the peak moved on, the company was left absorbing the aftermath.

It was the promise and peril of platforms, in one chapter.

VelocImmune proved it could produce potent neutralizing antibodies at speed. But infectious disease doesn’t reward one-time development victories. It’s a moving target. The real requirement for future outbreaks wasn’t just rapid antibody discovery—it was continuous variant surveillance and the ability to update therapies as the pathogen changed.

The BARDA arrangement also reopened an old argument that pandemics make unavoidable: what does “fair” mean when taxpayers fund most of the development and a private company controls pricing? Critics argued that the 2017 terms allowed public money to support private enrichment during a crisis. Regeneron’s counterargument was that commercial control is what makes companies willing to keep expensive readiness capabilities alive in the quiet years between outbreaks. Remove the upside, and few organizations will carry the cost of preparedness.

And COVID wasn’t Regeneron’s only infectious-disease proof point.

In October 2020, the FDA approved Regeneron’s Ebola antibody cocktail, Inmazeb, as the first approved treatment for Ebola virus disease. In the PALM trial, which was stopped early because of its results, mortality was 33.8% with Inmazeb versus 51% for the control treatment. In 2022, the World Health Organization issued its first-ever Ebola therapeutics guidelines, strongly recommending Inmazeb. Regeneron donated the drug at no cost to countries experiencing outbreaks—an approach that recognized the public-health imperative while underscoring the difficult economics of therapies for rare, unpredictable crises.

The debate about incentives, access, and preparedness didn’t end with REGEN‑COV. But one thing did become unmistakable: Regeneron had built a science engine that could turn a brand-new threat into a real therapeutic option in months. In a world where the next outbreak is a question of when, not if, that capability isn’t just a product story. It’s strategic infrastructure.

VIII. Platform Technologies & The Science Engine

In most pharmaceutical companies, R&D is treated like a cost line—necessary, expensive, and judged by how many approvals it can crank out per dollar. Regeneron has always worked from a different premise. For Schleifer and Yancopoulos, scientific capability isn’t a means to an end. It is the asset. The thing you build, protect, and compound over decades until it becomes the advantage no competitor can simply buy.

That’s what the “platform” idea really means at Regeneron. Not one breakthrough. An engine.

At the center of that engine is still VelocImmune: the genetically engineered mice that can produce fully human antibodies after immunization. It’s easy to say in one sentence and hard to appreciate in practice. To make it work, Yancopoulos’s team had to replace large sections of the mouse antibody gene regions with human sequences, without breaking the mouse immune system in the process. The animals had to remain healthy, mount normal immune responses, and reliably generate diverse, high-affinity antibodies that could be developed directly into drug candidates—without the usual rounds of re-engineering.

Before VelocImmune, the standard antibody workflow was slow and bespoke. Companies would immunize mice, identify a promising antibody, and then “humanize” it—essentially rebuilding it so the human immune system wouldn’t reject it. Every program became its own custom engineering project, with its own surprises, delays, and failure modes.

VelocImmune erased that step. The antibody comes out human from the start.

That didn’t just shave time off a schedule. It changed the shape of the company. If you can make high-quality antibodies faster, you can run more programs in parallel. You can take more shots. You can afford to be ambitious about targets. And over time, you get something that’s even harder for outsiders to copy than the mouse itself: institutional muscle memory. Regeneron learned, across program after program, what immunization strategies worked, how to screen efficiently, what properties tended to predict success downstream, and how to manufacture antibodies at scale. Even as patents age and others develop or license similar approaches, that accumulated know-how remains a moat.

VelocImmune was never meant to stand alone. It sits inside the broader VelociSuite—an integrated toolkit designed to take a target from hypothesis to candidate faster than traditional R&D allows. VelociGene enabled precise genetic modifications in mice, both to build the humanized systems that made VelocImmune possible and to create disease models for testing. VelociMab supported the characterization and selection of antibodies with the properties you actually want in a drug. The through-line is integration: the tools are designed to feed into one another, so discovery, validation, and optimization aren’t separate silos—they’re a pipeline.

Then Regeneron made another bet: that the next big unlock wouldn’t come from better mice, but from better humans.

The Regeneron Genetics Center, or RGC, was built around a brutal truth of drug development: many drugs fail not because they miss their target, but because the target wasn’t truly causal in human disease. Biology that looks convincing in cells and animal models can collapse when it meets the complexity of real patients. The RGC’s answer was to start closer to the source—to use human genetics to validate targets before the company poured years and billions into clinical trials.

By early 2026, the RGC had sequenced nearly 3 million human exomes, the protein-coding portion of the genome—one of the largest datasets of its kind. The ambition was to push that into the 5-to-10-million range, because scale is the whole point: the rarer the variant, the more people you need to find it, and the more confidence you can have in what it’s doing.

The payoff is what geneticists call “experiments of nature.” If some people are born with variants that effectively reduce or eliminate a protein’s function, and those people end up healthier in a specific way, that’s powerful evidence that blocking that protein could make a good drug.

The RGC had already produced that kind of signal. Its researchers found that rare mutations in a gene called GPR75 were associated with meaningfully lower obesity risk. Carriers weighed, on average, about 12 pounds less than matched individuals without the variants, and had roughly half the odds of being obese. That doesn’t automatically create a medicine—but it gives Regeneron a compelling hypothesis with something drug developers crave: human validation.

This genetics-first logic reflects a broader evolution in R&D strategy. Traditional drug discovery leaned heavily on animal models that often fail to predict human outcomes. The industry’s infamous statistic—roughly 90% of drugs that look promising before clinical trials ultimately fail in humans—exists for a reason. Human biology is different in subtle ways that matter enormously, and what “works” in a mouse can be irrelevant, or unsafe, in a patient.

Regeneron’s approach doesn’t eliminate that risk. It tries to shift the odds by choosing targets where human biology is already pointing in the right direction. If naturally occurring loss-of-function variants are tolerated—and even beneficial—that’s a strong hint that a therapeutic inhibitor might be both effective and safe enough to use chronically.

The RGC also strengthened Regeneron’s position at the deal table. A partner wasn’t just getting access to an antibody factory; they were potentially getting access to target selection insights rooted in one of the world’s largest genetic datasets. And like any dataset-driven advantage, it compounds: the more people sequenced, the more rare signals you can detect, and the more valuable the entire resource becomes.

All of this is enabled—and amplified—by culture. Regeneron’s leadership includes Nobel Laureates and eight members of the National Academy of Sciences. Yancopoulos, decades after co-founding the company, stayed deeply involved in research strategy as Chief Scientific Officer and President of Regeneron Laboratories. The physician-scientist model isn’t branding; it’s how decisions get made. Scientists aren’t just consulted. They’re in the chain of command.

That has practical consequences. It helps Regeneron keep exceptional talent in a field where the best researchers can choose academia, startups, or bigger paychecks elsewhere. People who want to build long arcs of discovery tend to gravitate to places where the work is respected—and where basic research isn’t treated as a luxury that gets cut the moment a quarter looks ugly. Regeneron earned credibility on that front by investing in science even during the years when it didn’t yet have blockbuster products to fund it.

The platform mindset shows up in capital allocation, too. Rather than leaning on acquisitions or paying premiums for late-stage external assets, Regeneron mostly invested in internal R&D and in making its platforms better. It’s a slower, more patient strategy. Platforms take years to mature, and the early spending can look like stubbornness.

But when it works, you don’t just get a drug.

You get a machine that keeps making them.

IX. The Oncology Push and Pipeline Evolution

In oncology, the scoreboard is brutally public. Data goes up on a slide, and within seconds everyone in the room knows if your drug belongs in the conversation—or if it’s another footnote.

For Regeneron, that pressure was the point. After building two giant franchises in immunology and ophthalmology, the company turned toward the hardest proving ground in medicine: cancer. If its science engine was truly a machine, it should be able to produce meaningful oncology medicines too—not just clever molecules.

The first real test was Libtayo (cemiplimab), Regeneron’s entry into the PD-1 inhibitor class. PD-1 is one of the immune system’s “brakes.” Tumors exploit that pathway to hide in plain sight. Block PD-1, and the immune system can sometimes recognize the cancer and attack it.

The catch is that by the time Regeneron arrived, the PD-1 market had already been claimed. Merck’s Keytruda and Bristol Myers Squibb’s Opdivo had raced ahead, stacking up indications and building multi-billion-dollar franchises. Competing head-on, in the biggest tumor types, would have meant fighting incumbents with years of clinical momentum.

So Regeneron took a different angle: start where others weren’t looking.

In September 2018, Libtayo won its first FDA approval in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC). CSCC is common—around 700,000 cases a year in the U.S.—but most patients are cured with surgery. The real unmet need sits with the small subset whose disease becomes advanced or metastatic. For those patients, options used to be thin.

In that setting, Libtayo delivered something that got oncologists’ attention: response rates around 50% in trials. Not a marginal improvement—real tumor shrinkage in patients who didn’t have many places left to go. From there, Regeneron broadened Libtayo’s footprint into basal cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and cervical cancer, building both commercial scale and clinical credibility.

By October 2025, Libtayo reached an important milestone: FDA approval as the first and only immunotherapy for adjuvant treatment of CSCC, meaning it could be used after surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence in high-risk patients. In the Phase 3 C-POST trial, Libtayo reduced the risk of disease recurrence or death by 68% compared to observation alone. At 24 months, disease-free survival was 87.1% for patients receiving Libtayo versus 64.1% for placebo.

The business started to reflect that traction. In full-year 2024, Libtayo global net sales reached $869 million, up 50% versus the prior year. It wasn’t a Keytruda-sized juggernaut. But it was real revenue, and more importantly, a foothold.

Still, Libtayo was only the opening act. The bigger swing was about what comes after PD-1: bispecific antibodies.

Bispecifics are engineered to bind two targets at once—often one on the tumor and one on an immune cell. In plain terms, they can act like a molecular tether, physically bringing T cells into contact with cancer cells and forcing an attack. It’s a step beyond classic single-target antibodies, and it offered Regeneron a path to differentiation in a crowded oncology landscape.

Regeneron advanced several bispecific programs. Linvoseltamab (called Lynozyfic in some markets) targets BCMA on multiple myeloma cells and CD3 on T cells. The European Commission granted conditional marketing authorization in April 2025, and the FDA granted accelerated approval for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma in patients who had received at least four prior therapies. Another candidate, odronextamab, targets CD20 and CD3 and moved through development for non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Then there was REGN7075—arguably the most conceptually ambitious of the group. It’s a costimulatory bispecific that targets EGFR on tumors and CD28 on T cells. Instead of flipping T cells fully “on” by itself—which can trigger dangerous, uncontrolled immune activation—this approach aims to provide an extra signal that strengthens an immune response in the context of tumor engagement. In Phase 1/2 trials, combining REGN7075 with Libtayo showed anti-tumor responses in microsatellite stable colorectal cancer, a notoriously immunotherapy-resistant disease.

That colorectal signal mattered because it points at one of oncology’s biggest locked doors. Microsatellite unstable colorectal cancers can respond well to PD-1 inhibitors. But most colorectal cancers are microsatellite stable and typically don’t benefit from checkpoint blockade. REGN7075 suggested a possible way to reach that much larger population—though it was still early, and the development work ahead remained substantial.

As the science evolved, so did the Sanofi relationship in oncology. Sanofi and Regeneron had entered an immuno-oncology collaboration in 2015, with Sanofi committing up to $2.17 billion, including $640 million upfront plus potential milestones. But by 2021, Regeneron wanted control—real control—over its cancer strategy.

The companies restructured the deal: global rights to Libtayo transferred entirely to Regeneron. Sanofi received $900 million upfront and an 11% royalty on worldwide Libtayo net sales. For Regeneron, this was the point of the transaction: the ability to set priorities, run trials, and build a commercial oncology presence without needing partner alignment on every decision.

By 2026, oncology assets made up nearly half of Regeneron’s pipeline, reflecting how central cancer had become to the next chapter of the company. Regeneron also partnered with ModeX Therapeutics to develop multispecific antibodies, while continuing to push internal programs across both solid tumors and blood cancers.

The strategic logic was obvious. Oncology is the largest opportunity in pharmaceuticals, with global spending exceeding $200 billion a year and rising. If Regeneron could build a durable oncology franchise, it would have a third pillar to stand beside Dupixent and Eylea—and a new proving ground for its platform advantage.

But the battlefield was unforgiving. Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, and others weren’t just competitors; they were incumbents with decades of infrastructure, relationships, and clinical experience. Regeneron’s counterposition was the same one that had worked before: don’t buy your way into relevance. Invent your way into it. Bet on internal R&D, new mechanisms, and platforms that can keep generating candidates faster than rivals can.

Whether that would translate into meaningful oncology market share was still the open question. In cancer, timelines are long and failure is common. If the payoff came, it likely wouldn’t be immediate. But Regeneron had made its choice: it was going to try to win oncology the same way it won everything else—by building the science, then trusting the machine.

X. Partnership Dynamics & Strategic Evolution

In late 2024, a letter from Sanofi’s lawyers landed at Regeneron’s headquarters. It was a response to the lawsuit Regeneron had filed weeks earlier, and it revolved around something that sounds painfully inside-baseball: access to pharmacy benefit manager contracts for Dupixent.

But those contracts are where the money lives. They govern rebates, discounts, and the real net price of a drug. In a 50/50 profit split, that means they can determine—quietly—who’s effectively paying for what. A partnership that had helped transform both companies was now, at least in part, being argued through legal filings.

To understand how it got here, you have to appreciate how far the power dynamics had swung since 2007. Back then, Regeneron was a small biotech with a brilliant platform and a terrifying problem: it needed capital and global muscle. Sanofi’s funding wasn’t just helpful; it was oxygen.

By 2024, Regeneron was a very different animal—generating more than $14 billion in annual revenue, with a market capitalization above $80 billion. The company that once needed Sanofi to reach the world could now credibly compete with Sanofi in the world.

That long history also left a visible artifact on the cap table. Sanofi still owned 20.6% of Regeneron, a legacy of the equity investments that accompanied the original alliance. It created a strange dual role: Sanofi was both partner and major shareholder, benefiting from Regeneron’s overall success, not just the collaboration drugs. But it also created an overhang. If Sanofi ever decided to sell, the market would have to absorb a lot of stock.

In late 2024, that’s exactly what Sanofi signaled it intended to do. It announced plans to reduce its stake, selling about 12.8 million shares from its roughly 23.2 million-share position. Some would go through a public offering, and Regeneron agreed to repurchase $5 billion of its own stock to help absorb the supply. The message was clear: Sanofi was dialing down its financial exposure even as the commercial partnerships stayed in place.

The lawsuit itself put a spotlight on the fragile mechanics of profit-sharing. When two companies split profits equally, they also split the cost of every payer concession—every rebate, every discount. If Sanofi negotiated bundled discounts that used Dupixent rebates to improve access for other Sanofi products—products Regeneron didn’t share economics on—then Regeneron would, in effect, be helping finance Sanofi’s broader portfolio strategy. Regeneron alleged that this was exactly the risk, and that Sanofi had refused to provide full transparency into PBM agreements that could confirm it.

Sanofi wasn’t Regeneron’s only major partner, of course. Bayer continued to commercialize Eylea outside the U.S., while Regeneron kept U.S. rights and manufacturing. Roche partnered with Regeneron on certain development programs. Intellia Therapeutics collaborated with Regeneron on gene-editing approaches that could eventually reshape how diseases are treated—potentially even challenging the antibody-centric paradigm Regeneron helped define.

What ties these relationships together is a philosophy Regeneron learned the hard way: partner to accelerate, but don’t give away the future.

Regeneron tended to license technologies rather than simply selling programs. It pushed for structures that preserved long-term economics—profit-sharing where it could, not just a small royalty stream. And it built internal capabilities so it could keep developing and manufacturing even if a partnership ended. That last point matters more than it sounds. If you can’t carry a program yourself, you can’t negotiate like an equal.

This is where Regeneron’s model diverged from the typical biotech path. A small biotech with a promising molecule often takes the standard deal: some cash up front, milestones if everything goes right, and single-digit royalties if the drug becomes huge. It’s not irrational—it’s survival. But it also means most of the upside leaves the building.

Regeneron tried to avoid that trade. The Dupixent structure shows why: U.S. profit-sharing turned into billions of dollars of economics that would have looked dramatically smaller under a conventional royalty deal. The tradeoff was obvious too: co-development means paying your share. It’s capital-intensive, and in the early years, Regeneron couldn’t have done it without Sanofi’s funding.

That’s the irony at the heart of the Sanofi story. The very partnership that kept Regeneron alive also helped Regeneron stay independent long enough to become powerful—and once it became powerful, it became more willing to challenge its partner when incentives didn’t line up.

As power shifts, old terms start to feel different. What you tolerate as a dependent company can feel unacceptable as an equal. Regeneron’s decision to litigate reflected a level of confidence that would have been unthinkable in 2007.

Looking forward, the strategic question isn’t “partner or not.” It’s where partnerships still make sense. Regeneron had proven it could develop and commercialize drugs on its own in the United States. International infrastructure was still less built out. And as the industry moved into new modalities—gene therapy, cell therapy, and other next-generation approaches—the right partnership structures might look very different from the classic antibody playbook.

By early 2026, Regeneron expected to fully repay obligations to Sanofi under prior restructuring agreements, which would unlock additional revenue growth. The company that once relied on Big Pharma to survive was now throwing off billions in operating cash flow. The alliance that saved Regeneron had evolved into something more complicated: still valuable, still intertwined—but no longer existential.

XI. Playbook: Business & Scientific Lessons

Regeneron’s arc—from a Manhattan apartment to one of biotech’s most formidable companies—doesn’t read like a lucky streak. It reads like a set of choices, repeated over decades, that created advantages that compounded.

Platform Technologies Over Product Hunting

Most biotechs live and die by a single molecule. They pick a lead program, bet the company, and hope the next clinical readout is a miracle instead of a funeral. Regeneron built itself the other way around: not around one drug, but around tools that could keep generating drugs.

VelocImmune is the clearest example. It wasn’t a clever trick to make an antibody for a specific disease. It was a repeatable system for producing fully human antibodies against almost any target that made biological sense. That matters because platforms change the math. Instead of one coin flip, you get a portfolio of experiments, all benefiting from the same underlying infrastructure and accumulated know-how.

The catch is that platforms demand patience—exactly what public markets tend to punish. They don’t show up as clean “catalysts.” They require years of spending before they generate products, much less revenue. Regeneron spent roughly two decades building VelocImmune before it became the engine behind the company’s biggest medicines. Most teams never get the time, capital, or internal conviction to see a bet like that through.

Physician-Scientist Leadership

Regeneron also organized itself in a way that’s still unusual in large pharma: the people at the top could actually argue the science.

Schleifer was a neurologist. Yancopoulos trained as an MD/PhD and stayed deeply engaged in research. Nobel Laureates weren’t just names on a brochure; they were part of how the company anchored credibility and judgment. When Regeneron made big calls—what biology to bet on, when to kill a program, when to double down—it didn’t outsource that thinking to a layer of professional managers. Scientific judgment sat at the center of strategy.

That governance model changed incentives, too. Leaders who came up through science, and who became wealthy by turning science into medicines, tended to optimize for long-term outcomes rather than near-term optics. The company’s willingness to walk away from failed ideas while continuing to fund unproven platforms looked less like conventional corporate discipline and more like the scientific method applied to business.

Internal R&D Over M&A

While much of Big Pharma has relied on acquisitions to refill pipelines, Regeneron stayed stubbornly homegrown. Nearly every major product in its portfolio started in its own labs.

That choice came with a trade. It meant slower, more uncertain growth in the early years—especially when the neurotrophic factor programs collapsed. But it also created something harder to copy than any individual asset: institutional capability. Regeneron built deep internal expertise in antibody discovery, manufacturing, and clinical execution, and that expertise improved with every program.

Acquisitions can buy molecules, but they rarely buy the muscle memory required to keep producing them. Acquirers also tend to overpay for late-stage assets, effectively transferring value to sellers. Regeneron avoided a lot of that by building rather than buying—keeping both the economics and the learning inside the building.

Partnership Structure: Preserving Independence

Regeneron didn’t shun partnerships. It used them—carefully.

The Sanofi and Bayer relationships solved a real problem: how to fund massive development efforts and reach global markets without giving away the company’s future. The key was structure. Regeneron pushed for profit-sharing where it mattered, not just royalties. That single distinction is the difference between “nice upside” and “generational economics,” especially when a drug becomes a franchise like Dupixent.

Those deals also preserved optionality. When Regeneron wanted to take full control of Libtayo, the partnership could be reworked. When the antibody discovery collaboration ended in 2017, Regeneron didn’t collapse; it kept going. The partnerships provided resources and reach, but they didn’t turn Regeneron into a dependent R&D vendor.

Culture: Scientists as Heroes

“Scientists are the heroes” is the kind of line companies love to say. At Regeneron, it has been closer to an operating principle.

They invested heavily in research facilities, recruited top-tier talent, and created career paths where scientists could rise and be recognized without needing to become pure administrators. That matters because biotech is a talent business. If you can consistently attract and retain people who could have stayed in academia—or gone to the highest bidder—you’ve built an advantage that shows up years later in the pipeline.

The culture also shaped how the company handled failure. Scientists expect most experiments not to work. The question is whether you learn fast enough to move to a better hypothesis. Regeneron’s ability to survive two Phase III collapses, then pivot into antibodies and build platforms, is exactly what that mindset looks like when it’s embedded across an organization.

Capital Allocation: R&D Intensity

Finally, Regeneron spent like it meant it.

The company consistently invested more than 20% of revenue back into R&D—well above typical pharma levels. That’s not just an accounting choice. It’s a declaration of what the company believes creates durable advantage: not squeezing an extra point of margin from today’s products, but building the discovery engine that produces tomorrow’s.

Plenty of companies can look brilliant for a few years by optimizing commercialization and trimming research budgets. Regeneron made the opposite bet: that sustained leadership in science would deliver better long-term returns than near-term margin maximization. The result is what we see in the story as a whole—blockbusters that fund platforms, platforms that create pipelines, and a pipeline that keeps the company from ever being a one-product miracle.

XII. Analysis: Bull and Bear Cases

Bull Case: The Platform Advantage Compounds

The strongest bull case for Regeneron is that it isn’t really a “two-drug company.” It’s a drug-making machine that happens to have two huge winners right now.

VelocImmune and the broader VelociSuite have already produced multiple blockbuster medicines, and they keep turning new targets into clinical candidates at a pace that looks more like manufacturing than traditional biotech R&D. Every program that reaches the clinic is, in effect, a new option: most won’t become the next Dupixent, but the point of a platform is that you don’t need most to. You need a few to hit—and the machine keeps taking shots.

Dupixent still has room to grow. The pattern has been consistent: prove the biology in one major Type 2 inflammatory disease, then keep walking outward into adjacent conditions that share the same immune wiring. As more indications arrive in 2026 and beyond, the addressable population expands, and Dupixent becomes harder to dislodge—not because it’s the only answer, but because it’s the default answer across more and more of the Type 2 landscape.

Eylea HD is the other major pillar of the bull case: a credible lifecycle defense in the face of biosimilars. It offers a benefit that’s immediately legible to both doctors and patients—fewer injections—so the choice isn’t just “brand versus cheaper.” It’s “less treatment burden versus cheaper.” In ophthalmology, that difference can be decisive. Regeneron also benefits from years of deeply embedded relationships with retina specialists, which creates real friction against rapid switching.

Then there’s the pipeline. Regeneron has late-stage programs across oncology and other major areas, plus earlier work in cardiovascular, obesity biology, and rare disease. The argument isn’t that every program will work. It’s that with enough high-quality shots on goal, a few will. And the Regeneron Genetics Center adds another layer: by using human genetics to validate targets, Regeneron is trying to push more of its risk to the front end of R&D—before it spends years and billions in Phase 3.

Bear Case: Competition and Concentration Risk

The bear case starts with a simple fact: the business still leans heavily on two franchises. Dupixent and Eylea drive the majority of earnings power. That’s great when both are climbing. It’s painful when either one stumbles.

Eylea is walking into the classic post-patent grind. Biosimilars are here, more are coming, and interchangeability can accelerate substitution. Even if Eylea HD is clinically attractive, payers may force the cheaper option, especially in more price-sensitive settings. If the market turns into a price war, durability alone may not fully protect the franchise’s economics over the next several years.

Dupixent has a longer runway, with patent protection into the early 2030s—but that doesn’t mean it’s untouchable. Competitors are building around Type 2 inflammation with different targets and potentially different formats, including approaches that could be more convenient than an injectable biologic. And the ongoing Sanofi litigation adds another kind of risk: even if the medicine keeps winning, disagreement over transparency and deal economics can create friction inside the partnership that underpins the franchise.

Oncology is the other core bear point. Regeneron has done real work—Libtayo is a legitimate product—but it’s fighting in the industry’s most competitive arena. Keytruda’s dominance sets the terms of engagement for PD-1, and bispecific antibodies are a hot battleground with many well-capitalized competitors. Regeneron’s science engine gives it a chance, but meaningful, durable oncology market share is not guaranteed.

Finally, valuation matters. At roughly 18 times trailing earnings, the stock price bakes in continued execution: more Dupixent expansion, a strong Eylea defense, and pipeline progress that produces new revenue pillars. If any of those weaken, the multiple has room to compress.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Supplier Power: Low to moderate. Regeneron manufactures much of what it sells, which reduces reliance on outside contract manufacturers. Biologics still require specialized inputs, but most are not controlled by a single chokepoint supplier.

Buyer Power: Moderate and rising. PBMs, insurers, and large health systems have significant leverage, and they’re increasingly aggressive about rebates and formulary positioning. That pressure is real. At the same time, specialist-driven biologics with strong clinical value can retain pricing power when alternatives are limited or clearly inferior.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate. Over time, new modalities—gene therapy, cell therapy, potentially oral small molecules—could replace chronic injectable biologics in some indications. The threat isn’t immediate across the board, but it’s part of the long-term landscape.

Threat of New Entrants: Low in mature biologics markets, higher in the “next wave.” Manufacturing and development are still capital-intensive, which keeps barriers high. But the specific advantage of “we can make antibodies” is no longer rare across top-tier biopharma.

Competitive Rivalry: High in oncology, moderate in immunology and ophthalmology. Cancer is a knife fight. In Type 2 inflammation, Dupixent has had more breathing room, but that space tends to attract competitors as markets grow and the prize becomes obvious.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Meaningful in manufacturing and development infrastructure. Once you have large fixed-cost facilities and the volume to utilize them, your unit economics improve—and smaller competitors struggle to match that efficiency.

Network Effects: Limited. This isn’t software; Regeneron doesn’t get stronger simply because more people use its drugs, at least not in a direct network-effect sense.

Counter-Positioning: Strong. Regeneron’s science-first, platform-led model is structurally different from the acquisition-heavy approach many incumbents rely on. It’s not easy to copy quickly because it requires years of culture, talent, and tooling—not just a strategy memo.

Switching Costs: Moderate. In ophthalmology especially, familiarity with dosing patterns and patient response creates inertia. The same is true in chronic immunology care, where a stable patient on an effective therapy is not casually switched.

Cornered Resource: Historically, VelocImmune fit this category more tightly; today, similar capabilities exist elsewhere. The better candidate is the Regeneron Genetics Center dataset, which could become increasingly unique as it scales and continues generating human-validated targets.

Process Power: Strong. The cumulative know-how of repeatedly turning biology into clinical programs—plus the integration between tools, models, screening, and manufacturing—creates an advantage that rivals can’t replicate overnight.

Branding: Moderate. Regeneron’s brand is powerful with specialists in ophthalmology, dermatology, and immunology. Consumer recognition exists—especially through Dupixent—but the company’s real brand equity lives in prescriber trust.

Key Performance Indicators

For anyone tracking whether the story is staying on the rails, two metrics do most of the work:

-

Dupixent patient growth: Dupixent is central to Regeneron’s economics, so patient additions are an early signal of franchise health. The drug surpassed 1.4 million active patients worldwide by early 2026. The question is whether that base keeps expanding as new indications come online—and whether growth remains durable rather than plateauing.

-

Eylea franchise retention: Biosimilars make the Eylea question brutally simple: can Eylea HD preserve share and economics as cheaper substitutes spread? Watching combined Eylea plus Eylea HD share in anti-VEGF therapy—currently around 45%—gives a direct read on whether the defense is holding.

XIII. Epilogue: The Next Decade

The boardroom in Tarrytown still looked like it always had—more practical than polished, built for people who care about data more than décor. Leonard Schleifer, now in his early seventies and still CEO, looked over the priorities in front of him. Regeneron had survived its long valley of death, turned partnerships into leverage instead of dependency, and grown into one of biotech’s most successful independent companies.

Now came the hardest kind of question: what does the next decade look like when you’re no longer the underdog?

Succession planning, inevitably, sat near the top of the list. Schleifer and George Yancopoulos had been running Regeneron since the beginning—an almost unheard-of stretch of continuity in an industry where leadership often turns over every few years. They didn’t just lead the company; they built its operating system: the science-first culture, the platform mindset, the instinct to keep invention in-house. The challenge ahead wasn’t simply finding new executives. It was proving that the culture could outlive the people who created it.

At the same time, the technology frontier was shifting. Gene editing held out the promise of curing diseases permanently instead of treating them chronically. Cell therapies were rewriting what was possible in cancer and immunology. Regeneron had already put money and effort into partnerships and internal work in these areas, but its core advantage—the thing it had compounded for decades—was still rooted in antibodies and the platforms that produce them. The next era would test whether Regeneron could extend that playbook into new modalities, or whether the industry’s center of gravity would move away from what it did best.

There was also a geographic question. Regeneron’s commercial strength remained most developed in the United States, while partners handled much of the rest of the world. Building a larger direct international presence could improve long-term economics and control, but it would take time and heavy investment. For now, the company’s posture still looked strongly domestic, underscored by a roughly $7 billion capital commitment to U.S. manufacturing and research capabilities that was part of its 2026 planning.

And then there was obesity—an opportunity so large it was pulling the entire biopharma industry toward it.

Regeneron’s COURAGE trial, which combined GLP-1 receptor agonists with novel muscle-preserving therapies, produced promising Phase 2 results. The combination preserved about half of the lean mass that’s typically lost during GLP-1-driven weight loss—an effect that could matter enormously if it holds up in larger studies. In a market that was rapidly becoming one of the biggest in all of medicine, that kind of differentiation could be the seed of a new franchise.