Roper Technologies: The Industrial-to-Software Metamorphosis

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

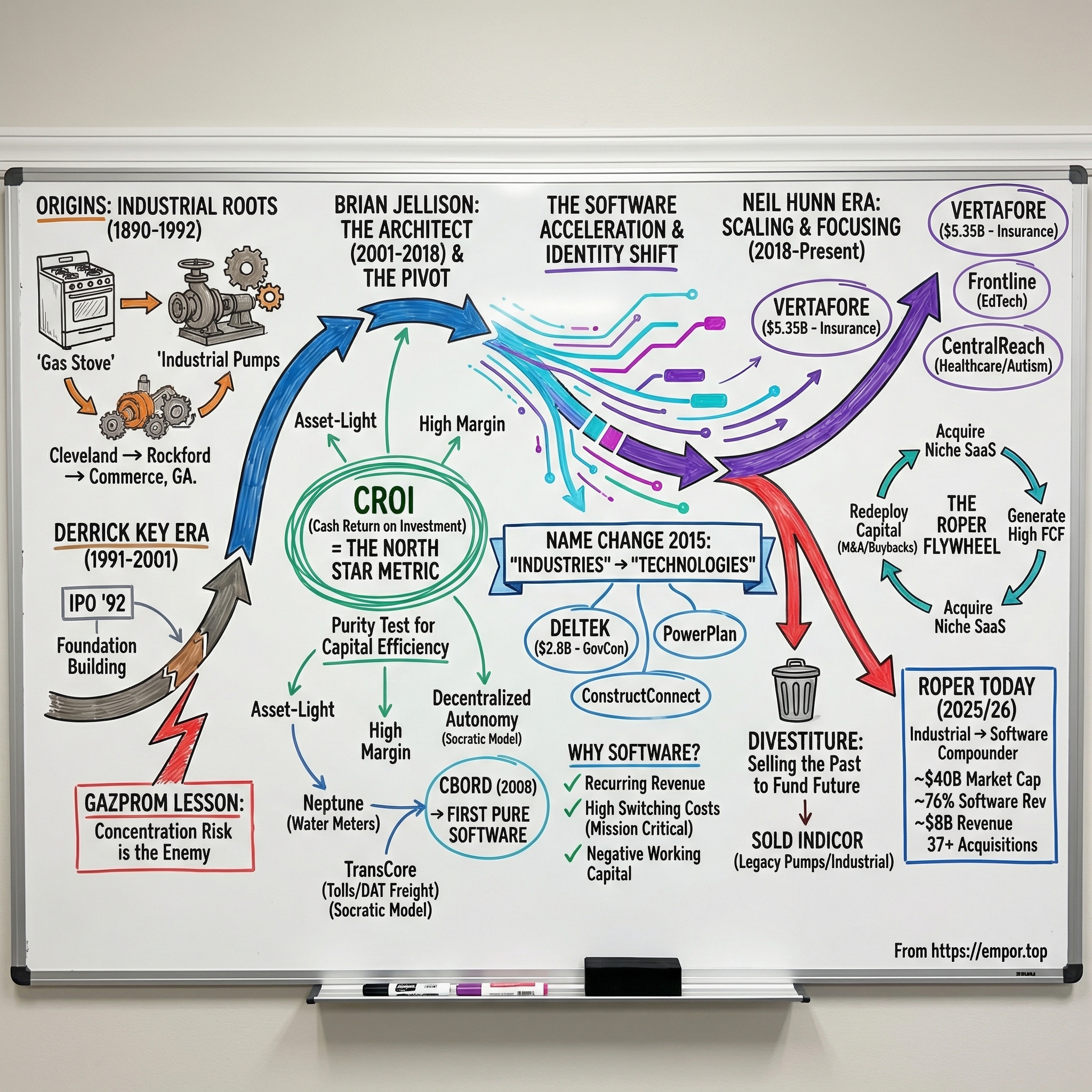

Picture a company founded in 1890 to make gas stoves in Cleveland, Ohio. Now picture that same company, 135 years later, commanding a market capitalization approaching $40 billion, sitting in the Nasdaq 100, and generating nearly $2.5 billion a year in free cash flow from a portfolio of niche software businesses that do everything from managing electronic toll collection to running childcare centers to powering insurance agencies to coordinating autism therapy.

The distance between those two images is the story of Roper Technologies, and it is one of the most remarkable corporate metamorphoses in American business history.

Roper Technologies, traded on the Nasdaq under the ticker ROP, reported full-year 2024 revenue of $7.04 billion, up 14% year over year, with adjusted EBITDA of $2.83 billion. By 2025, revenue climbed further to $7.9 billion. The company's three operating segments tell the story of where it stands today: Application Software contributes 57% of revenues, Network Software another 20%, and Technology Enabled Products the remaining 23%.

Strip away the physical products, and more than three-quarters of Roper's revenue now comes from software, $6.1 billion of $7.9 billion in 2025. That is an extraordinary ratio for a company whose original business was casting iron stove parts.

The central question of this story is deceptively simple: How did a manufacturer of pumps and gas stoves become one of the best-performing software conglomerates of the 21st century? The answer involves three transformative leaders, a proprietary financial metric that rewired how the company thinks about capital, a series of increasingly bold acquisitions, and a willingness to shed the company's own identity when the numbers demanded it.

What makes Roper especially instructive for investors is that it did not stumble into software through a single lucky bet. It evolved deliberately over two decades, building institutional capabilities in acquisition sourcing, due diligence, and integration that now function as genuine competitive advantages. The playbook is replicable in theory but fiendishly difficult in practice, which explains why so few industrial companies have managed a similar transition.

This is the story of the people and decisions that made it happen.

II. Origins: From Gas Stoves to Industrial Pumps (1890-1992)

In 1890, in a Cleveland workshop thick with coal dust and iron filings, George D. Roper purchased a small operation called the Van Wie Gas Stove Company. America was industrializing at breathtaking speed, and the domestic kitchen was the frontline of that transformation. Gas stoves were replacing wood-burning ranges in homes across the Midwest, and Roper saw an opportunity to build a business at the intersection of manufacturing craft and consumer demand. He was an industrialist of the classic Gilded Age mold, hands-on, ambitious, and willing to bet everything on his own judgment. By 1894, he had become sole owner.

Then disaster struck. A fire destroyed the Cleveland facility, the kind of catastrophe that would have ended many entrepreneurial ventures of the era. Roper did not retreat. He rebuilt, relocated to Rockford, Illinois, a thriving manufacturing center along the Rock River, and rechristened the operation as the Eclipse Gas Stove Company. The move to Rockford proved fortuitous. The city offered skilled labor, rail connections, and a concentration of metalworking expertise that would sustain the business for decades. Under his stewardship, the renamed George D. Roper Corporation grew into one of America's leading manufacturers of gas ranges and home appliances, a household name in the Midwest whose products could be found in kitchens from Chicago to Cincinnati.

But Roper was not content with kitchen appliances alone. In 1906, he acquired the Trahern Pump Company, planting a flag in an entirely different market: industrial equipment. This was a consequential decision, one that would echo for more than a century. Pumps were not glamorous, but they were essential. Chemical plants, oil refineries, food processors, and water treatment facilities all needed reliable pumps to move fluids through their operations. A pump failure in a chemical plant did not just mean lost revenue; it could mean an environmental disaster or a safety catastrophe. Customers bought pumps not on price but on reliability, and they developed deep relationships with the manufacturers they trusted.

For the next half-century, the Roper empire operated two fundamentally different businesses under one roof: consumer stoves and industrial pumps. The stoves were high-volume, consumer-facing, and subject to the whims of housing cycles, consumer taste, and retail distribution relationships. The pumps were lower volume, sold to other businesses through technical sales channels, and embedded in industrial processes that demanded reliability above all else. The two businesses shared a name and a corporate structure, but almost nothing else.

By the 1950s, the strategic tension between these two lines became untenable. The appliance industry was consolidating rapidly, with large manufacturers like GE, Whirlpool, and Maytag building scale advantages that smaller players could not match. Roper's stove business, while profitable, lacked the volume to compete with these giants in the emerging era of mass consumer marketing and national retail chains. The stove business was sold in 1957 to Florence Stove Company, and the pump operations were relocated to Commerce, Georgia, where they became the Roper Pump Company. Freed from the consumer appliance business, the industrial side of the house focused on what it did best: specialty gear pumps and progressive cavity pumps for chemical processing, oil and gas, food manufacturing, and other heavy-duty applications.

For the next two decades, Roper Pump operated as a respectable but unremarkable mid-market industrial business, a classic American manufacturer serving a stable but slow-growing set of end markets. The company was profitable, its products were well-regarded, and its customer base was loyal, but there was nothing about Roper Pump in the 1970s that would have predicted what it would become.

Then, in 1981, a leveraged buyout took the company private, restructuring it as Roper Industries, Inc. The LBO was a product of its era, the same wave of financial engineering that was reshaping American industry from steel mills to retail chains. But unlike many LBOs of the period, which stripped assets, loaded debt, and flipped companies for quick profits, the Roper buyout set the stage for something constructive. The new owners recognized that the company had a solid foundation, good products, loyal customers, and reasonable profitability, but it needed new leadership and a new strategic vision to unlock its potential.

That leadership arrived from across the Atlantic. Derrick Key, a British-born executive who had previously consulted for Johnson & Johnson, joined Roper as Vice President in June 1982. Key was methodical, analytically rigorous, and possessed an outsider's willingness to question every assumption about how an American industrial company should be run. He did not come from the old-boy network of American manufacturing. He came from the world of management consulting, where the question was never "how have we always done it?" but rather "what does the data say we should do?"

Key was promoted to President in February 1989 and became CEO in December 1991. His first major act was to take the company public. In February 1992, Roper Industries listed on the New York Stock Exchange, raising capital that would fund a decade of acquisitive growth. At the time of the IPO, Roper was doing roughly $70 million in revenue with $14 million in EBITDA, a small but profitable niche manufacturer with ambitions well beyond its size. The IPO was not a liquidity event for insiders. It was a strategic move to give Roper the currency and capital access it would need to become something much larger.

III. The Derrick Key Era: Building the Foundation (1991-2001)

Derrick Key understood something that many industrial executives of his generation did not: the commodity pump business was a treadmill. You competed on price, fought for incremental share in mature markets, and watched margins compress whenever a new low-cost competitor entered from Asia or Eastern Europe. The global pump market was fragmenting, with established players facing pressure from manufacturers in India, China, and Eastern Europe who could produce comparable products at a fraction of the labor cost. Key's strategic insight was to shift Roper away from commoditized products and toward businesses where performance, reliability, and customer relationships created pricing power. He did not want to sell the cheapest pump. He wanted to sell the pump that customers could not afford to see fail.

To execute this vision, Key introduced the product manager system, assigning P&L ownership to individual managers responsible for their own lines of business. This was a radical decentralization for a company of Roper's size, and it had two effects. First, it created accountability. Each product line had a clear owner who could not hide behind corporate overhead allocations or blame other divisions for shortfalls. If a product line underperformed, there was one person who had to explain why, and that person had the authority to fix it. Second, it created a training ground for the kind of entrepreneurial general managers who would later run Roper's acquired businesses. The decentralized model that became Roper's hallmark under Brian Jellison actually had its roots in Key's era. When people talk about the "Roper way" of managing acquisitions, they are describing a culture that Key began building in the late 1980s.

The early acquisitions were small and disciplined, bolt-ons in pumps, valves, and instrumentation controls that shared the same essential logic: buy businesses with technical moats, install a single accountable leader, and let them operate. In 1990, Roper acquired Amot Controls for approximately $28 million, adding temperature and speed controls for engines and compressors. Amot's products were safety-critical; if a temperature sensor failed on an offshore oil platform, the consequences could be catastrophic. That criticality meant customers did not shop for the cheapest supplier. In 1992, Compressor Controls Corporation came aboard for around $35 million, giving Roper a leading position in turbomachinery control systems. These were the electronic brains that managed gas turbines and compressors in power plants, pipelines, and refineries, another market where reliability commanded a premium. ISL followed in 1994 for $10.5 million, and Gatan, a maker of electron microscopy instruments for scientific research, was acquired in 1996 for approximately $50 million. Gatan was a different kind of business, serving the scientific instrumentation market with products that had gross margins that would make a software company envious.

The results were impressive by any standard. In his first five years, Key quadrupled Roper's sales from $35 million to $147 million. Revenue continued climbing from roughly $70 million at the 1992 IPO to $587 million by 2001, with EBITDA growing from $14 million to a projected $150 million range over the same period. The stock rewarded shareholders handsomely. Key was proving that a disciplined acquirer in niche industrial markets could compound value at rates that rivaled much larger, more glamorous companies. Wall Street was beginning to take notice of the small manufacturer from Sarasota, Florida, where Key had relocated the corporate headquarters.

But there was a vulnerability buried in the portfolio, one that would prove instructive for everything that followed. Roper's Compressor Controls division had won a landmark contract with Gazprom, the Russian gas giant, in 1993. The deal was worth over $128 million across multiple years and was later extended by an additional $150 million. For a company of Roper's size, this was a transformative relationship, the kind of contract that analysts dreamed about. But it also made Roper dangerously dependent on a single customer in a volatile region. At its peak, oil and gas represented roughly one-third of Roper's revenue, and Gazprom alone accounted for approximately 8%.

When the Russian financial crisis erupted in 1998, the ruble collapsed, Russian banks defaulted on their obligations, and the global energy markets convulsed. The Gazprom exposure became painfully visible. Revenue from the relationship became unpredictable, payments were delayed, and Roper's stock suffered as investors recalibrated the risk in its portfolio. It was not a disaster, Roper was diversified enough to survive, but it was a sharp reminder that even the most profitable customer relationships carry hidden risks when they represent too large a share of the overall business.

The Gazprom experience taught Roper a lesson that would shape its strategy for the next two decades: concentration risk is the enemy of a serial acquirer. The best businesses are not just high-margin; they are diversified across customers, geographies, and end markets. A portfolio of 20 niche businesses, each with hundreds of customers, is fundamentally more resilient than a portfolio of five businesses where one customer relationship can move the needle. Key had built Roper from a tiny pump company into a half-billion-dollar industrial conglomerate, and in doing so, he had demonstrated both the power of the serial acquisition model and its limitations. The next phase of the journey would require a different kind of leader, someone who could see beyond the industrial world entirely.

IV. Enter Brian Jellison: The Architect (2001-2018)

Brian Dennis Jellison grew up in Portland, Indiana, a small town in the eastern part of the state where the dominant employers were factories and farms. He earned an economics degree from Indiana University and later studied at Columbia University. His first real job was in General Electric's management training program, the legendary crucible that produced multiple generations of American CEOs. From GE, Jellison moved to Ingersoll-Rand, where he spent 26 years and rose to Executive Vice President, overseeing approximately $4 billion in revenue across the company's industrial and infrastructure segments.

By any conventional career calculus, Jellison had reached the summit. He was a senior executive at a Fortune 500 company, commanding an enormous P&L and surrounded by a sophisticated corporate infrastructure.

But Jellison had grown disillusioned. Ingersoll-Rand's bureaucracy frustrated him. Decisions that should have taken days took months. Strategy was diluted by committee. The thing that had drawn him to GE in the first place, the relentless focus on performance and accountability, had been smothered by the very corporate apparatus that was supposed to enable it.

When Roper came calling in 2001, the offer must have seemed bizarre to outside observers. Here was a top-tier executive leaving a $12 billion industrial giant to run a company with a market capitalization of roughly $1.5 billion, a fraction of the business he had been managing at Ingersoll-Rand. Roper was, in the words of one analyst who covered the company at the time, "a small, irrelevant manufacturer."

But Jellison saw what others did not. He saw a platform: a publicly traded company with a sound acquisition track record under Derrick Key, a decentralized culture that valued operational autonomy, strong cash generation relative to its size, and no bureaucratic baggage. There were no entrenched fiefdoms to dismantle, no legacy IT systems to navigate, no corporate jets to justify. At Roper, he would have the autonomy to execute a vision that Ingersoll-Rand's corporate structure would never have permitted.

It was, in hindsight, the most important career decision in the Roper story. The right leader had found the right platform at the right time.

Jellison became President and CEO in 2001 and added the Chairman title in 2003. What followed was one of the great value creation stories in modern American business.

Over the next 17 years, he would grow Roper's market capitalization from $1.5 billion to over $30 billion. The stock delivered returns of approximately 1,300%, compared to roughly 160% for the S&P 500 over the same period. An investor who put $10,000 into Roper stock the day Jellison became CEO would have seen it grow to approximately $140,000 by the time he stepped down. Harvard Business Review named him one of the best-performing CEOs in the world, and Institutional Investor recognized him as "Best CEO" in 2018.

The intellectual engine of Jellison's transformation was a single metric: Cash Return on Investment, or CROI.

The formula is straightforward but powerful. Take cash earnings, defined as net income plus depreciation and amortization minus maintenance capital expenditures. Divide by gross investment, defined as net working capital plus net property, plant, and equipment plus accumulated depreciation. The result is a purity test for capital efficiency.

A business with a high CROI generates abundant cash relative to the assets tied up in its operations. A business with a low CROI is a capital hog, absorbing resources that could be deployed more productively elsewhere.

CROI became the lens through which every business in the Roper portfolio was evaluated, and its implications were far-reaching. If a division's CROI was declining, management had to explain why and present a plan to reverse the trend. If a potential acquisition target did not meet Roper's CROI threshold, it was passed over regardless of how attractive the strategic fit appeared. Jellison was famous for telling his team, "We don't acquire businesses that dilute our CROI." But the metric did more than just filter acquisitions. It also revealed which existing businesses were destroying value. A pump manufacturing division that required $50 million in working capital and $20 million in plant and equipment to generate $15 million in cash earnings had a very different CROI profile than a software business that required almost no physical assets and turned subscription revenue into cash with minimal friction. Over time, CROI became a sorting mechanism that systematically pushed Roper toward asset-light businesses and away from capital-intensive ones.

To put it in simpler terms: imagine you have two lemonade stands. The first one requires a $100 investment in a fancy cart, refrigeration, and inventory, and it generates $10 a year in profit. The second requires a $20 investment in a card table and some cups, and it generates $8 a year in profit. Most people would focus on the first stand because it generates more absolute profit. Jellison would focus on the second one because its return on invested capital is four times higher. Now multiply that logic across dozens of businesses and billions of dollars of deployment capacity, and you begin to see why CROI reshaped Roper's entire portfolio.

Jellison's management philosophy was equally distinctive and deeply personal. He ran a corporate headquarters of approximately 60 people out of a total workforce exceeding 15,000. Think about that ratio. Sixty people overseeing 15,000. Most companies of Roper's size would have hundreds of corporate employees managing shared services, internal audit, strategic planning, HR policy, IT governance, and countless other functions. Jellison believed those functions belonged at the business unit level, not at headquarters. There were no centralized budgets. Instead of traditional budgeting, where managers negotiate a number at the beginning of the year and then try to hit it, Roper measured leaders on variances from prior periods. Did you grow revenue compared to last quarter? Did you improve margins? Did cash flow increase? This approach fostered a culture of continuous improvement rather than sandbagged targets. There was no incentive to lowball your budget in January so you could beat it in December.

Jellison called this the "Socratic" model. Corporate leadership asked questions and evaluated performance but did not issue directives. Business unit leaders were expected to run their operations as if they owned them, with full autonomy over hiring, pricing, product development, and customer relationships. When Jellison visited a business unit, he did not arrive with a PowerPoint deck of corporate mandates. He arrived with questions. Why did this customer leave? What is your biggest competitive threat? Where do you see pricing power? The conversations were rigorous, sometimes uncomfortably so, but the direction always came from the business leaders themselves, not from Sarasota.

"We hate centralized directives," Jellison once said on an earnings call, a comment that drew approving nods from the decentralization enthusiasts in the investor community. "We don't have any budgets." In another famously blunt moment, he described Roper's acquisition strategy as: "Buy businesses with 40% gross margins from idiots in private equity who don't know how to run them." The comment drew laughs, but it was not entirely a joke. Roper's preferred hunting ground was the portfolio of private equity firms that had purchased niche software and technology businesses, improved their margins modestly, and were now looking to exit. PE firms operate on a cycle, typically three to seven years from acquisition to sale, and when the clock runs out, they need a buyer. Roper offered something PE firms could not: a permanent home where acquired businesses could invest for the long term without worrying about the next ownership transition.

V. The Acquisition Playbook & Early Software Moves (2003-2010)

The first great acquisition of the Jellison era came in 2003 when Roper purchased Neptune Technology Group for approximately $475 to $482 million. Neptune manufactured automated water meters and had an installed base covering roughly 35% of American homes.

Think about that number for a moment. More than one in three households in the United States had a Neptune meter measuring their water usage. Once installed, these meters were embedded in municipal infrastructure for decades. A city does not swap out its water meters on a whim. The installation is physical, involving pipes, connections, and calibration at each point of use. The data integration feeds into the city's billing and management systems. Creating a recurring revenue stream from replacement parts, upgrades, software, and service agreements that was almost impervious to economic cycles. Municipalities did not stop measuring water during recessions. They did not defer water meter maintenance because the stock market was down.

Neptune was a revelation. It showed Jellison and his team what a capital-light, high-recurring-revenue business looked like inside the Roper portfolio. The water meter business required minimal capital expenditure compared to traditional manufacturing, generated strong free cash flow, and had a customer base that effectively could not switch to a competitor without ripping out infrastructure across an entire city. The acquisition price was approximately 2.5 times revenue, a reasonable multiple for a business with those characteristics. Neptune planted a seed that would grow into a strategic conviction: Roper should own more businesses like this and fewer businesses that looked like traditional industrial manufacturing.

The following year, in 2004, Roper acquired TransCore for roughly $600 million. TransCore operated in two seemingly unrelated markets: electronic toll collection and freight matching. The toll collection business was straightforward, providing the technology that allowed cars to pass through toll plazas without stopping, the kind of RFID-enabled transponders that millions of Americans now take for granted.

But the hidden gem was a product called DAT, short for Dial-A-Truck, which had evolved from its origins as a literal phone-based freight matching service into an electronic platform connecting truckers with available loads. In the early days of trucking, finding a load was a manual process. Drivers would call dispatch, check bulletin boards at truck stops, or rely on personal networks. DAT digitized this process, creating a marketplace where shippers could post loads and truckers could find them.

DAT was a network business, and network businesses are the closest thing to a legal monopoly in capitalism. Every additional trucker on the platform made it more valuable to shippers, and every additional shipper made it more valuable to truckers. This is the same dynamic that makes platforms like eBay, Uber, and Airbnb so difficult to displace once they achieve critical mass. By the time Roper acquired it, DAT was already the dominant freight matching platform in North America, but few people outside the trucking industry appreciated its value. It was buried inside TransCore, which was itself presented primarily as a toll collection company.

Over the ensuing years, DAT would grow into one of the most valuable assets in the entire Roper portfolio, a quietly dominant platform business throwing off cash with minimal capital requirements. Roper eventually divested the toll collection business but kept DAT, a decision that speaks volumes about which business had the superior economics. In 2025, Roper continued to strengthen DAT through bolt-on acquisitions like Convoy and Outgo, further cementing its dominance in freight matching.

The selection criteria that Jellison articulated during this period became Roper's North Star for the next two decades. Target businesses should be capital-light, meaning they required minimal physical assets to operate. They should generate high margins, with gross margins above 40% as a baseline requirement. Revenue should be recurring or at minimum reoccurring, creating predictable cash flows. And the businesses should have modest sensitivity to macroeconomic cycles, serving markets where customers could not easily defer purchases because the product was mission-critical to their operations.

In 2008, Roper made what many consider the pivotal acquisition in the company's history: CBORD Group, purchased for $375 million.

CBORD provided campus card systems and food service management software to universities and healthcare facilities. If you have ever used a student ID card to pay for meals in a university dining hall, buy a coffee at a campus cafe, or access a dormitory, you have likely interacted with CBORD's technology.

It was, by any measure, Roper's first pure software acquisition. There were no pumps, no meters, no toll transponders. CBORD was code, sold on subscription, embedded in institutional processes, and virtually impossible to rip out once installed. A university's dining operations, access control, and campus commerce all flowed through CBORD's platform. Switching meant re-credentialing every student, retraining every staff member, and reconnecting every point-of-sale terminal on campus. The CBORD deal demonstrated that Roper could successfully identify, acquire, and operate a software business, building the institutional muscle memory that would enable far larger deals in the years ahead.

Between Neptune, TransCore, and CBORD, Jellison had assembled the proof of concept for what Roper would become. The CROI of these businesses was dramatically higher than the legacy industrial portfolio. They generated free cash flow that could be redeployed immediately into the next acquisition, creating a compounding flywheel.

And because the businesses operated in defensible niches with high switching costs, they were protected from the kind of competitive pressure that squeezed margins in commoditized industrial markets. The transformation was underway, but the acceleration phase was still to come.

VI. The Software Acceleration (2010-2018)

By the mid-2010s, the evidence was overwhelming. Roper's software and technology businesses were outperforming its legacy industrial operations on every metric that mattered: growth, margins, CROI, and customer retention. The legacy industrial businesses were not bad. They were profitable, well-managed, and served their customers well. But they required physical plants, inventory, and equipment. They were subject to cyclical demand in energy and manufacturing. And their CROI was structurally lower than the software portfolio because of the physical assets they needed to operate. The logical next step was to go all in.

In April 2015, the company changed its name from Roper Industries, Inc. to Roper Technologies, Inc. Naming might seem like a trivial detail, but for a company with a 125-year history as a manufacturer, it was a declaration of intent. The word "Industries" connoted factories, smokestacks, and physical production. The word "Technologies" connoted software, platforms, and intellectual property. The name change was a signal to the market, to prospective acquisition targets, and to Roper's own employees that the company's future lay in software and technology, not in industrial manufacturing. It also had practical benefits: when recruiting software executives and engineers, it helped to be called a technology company rather than an industrial one. By this point, Roper had deployed over $4 billion in technology acquisitions since 2010, and the portfolio spoke louder than any name ever could.

The deals that followed were transformative in scale. In 2016, Roper acquired ConstructConnect for $632 million. ConstructConnect operated a cloud-based platform for commercial construction bidding, connecting contractors with project opportunities. With over 800,000 users, it was the dominant platform in its niche, another network-effect business where scale begat more scale. Contractors used ConstructConnect because that was where the projects were, and project owners posted there because that was where the contractors were.

The business was a textbook Roper acquisition: capital-light, high-margin, recurring revenue from subscriptions, and operating in a niche market where the incumbent platform had accumulated such a critical mass of users that displacement was nearly impossible. In the same year, Roper also acquired Aderant, a provider of software for law firms, further expanding its footprint in professional services software.

But the marquee deal of 2016 was Deltek, acquired for $2.8 billion, the largest transaction in Roper's history at the time. Deltek was the leading global provider of enterprise software for project-based businesses, particularly government contractors and professional services firms. To understand Deltek's importance, consider what a government contractor does. When a defense company wins a contract from the Department of Defense, it needs to track every hour worked, every dollar spent, every subcontractor payment, and every compliance requirement. The Federal Acquisition Regulation, or FAR, imposes extraordinarily detailed reporting requirements on government contractors, and failure to comply can result in contract termination, financial penalties, or even criminal prosecution.

Deltek's software was the operating system for this compliance. More than 22,000 organizations in over 80 countries relied on Deltek to manage their operations, from opportunity tracking through project delivery and financial reporting. The switching costs were not just about convenience; they were about regulatory risk. A government contractor that switched away from Deltek had to be absolutely certain that the replacement system could handle every FAR requirement, every cost accounting standard, and every audit trail. Most chose not to take that risk.

Roper purchased Deltek from Thoma Bravo, which had acquired the company in a $1.1 billion take-private in 2012 and had grown recurring revenue by 60% during its four-year ownership. Thoma Bravo's investment thesis had been sound: buy a dominant vertical software business, improve its margins, and grow its recurring revenue base. But PE firms need exits, and Roper was the ideal buyer. Roper expected Deltek to deliver $535 million of revenue and $200 million of EBITDA in 2017. The deal added approximately $80 million to Roper's 2017 free cash flow, including financing costs.

The Deltek acquisition crystallized a pattern that would define Roper's M&A approach: buying proven software businesses from private equity sponsors who had already done the hard work of improving operations, then providing those businesses with a permanent home where they could continue compounding without the pressure of another PE exit cycle. Brian Jellison understood that the best software companies often languished in PE portfolios because the PE model demanded exits on three-to-seven-year timelines, disrupting management teams and creating uncertainty for customers. Roper offered permanence, and that was a powerful recruiting tool when competing against other PE firms for deal flow.

In 2018, Roper continued the pattern by acquiring PowerPlan for $1.1 billion, again from Thoma Bravo. PowerPlan provided financial planning and compliance software for asset-intensive industries like utilities, telecommunications, and transportation. When an electric utility needs to calculate its tax obligations across multiple jurisdictions, plan depreciation schedules for billions of dollars of physical assets, and comply with rate case requirements from public utility commissions, PowerPlan is the software that makes it possible.

The business was expected to generate approximately $150 million in revenue and $60 million in free cash flow. It was another capital-light, high-margin, recurring-revenue business serving customers who could not easily switch providers because the software was deeply embedded in their regulatory compliance and financial planning processes. The complexity of the tax code alone made switching prohibitively risky for PowerPlan's utility customers.

By this point, the transformation was undeniable. Software and technology businesses accounted for more than half of Roper's EBITDA. Free cash flow as a percentage of revenue had expanded from roughly 16% in 2001 to 26% by 2017, a reflection of the portfolio's shift toward asset-light businesses that converted revenue to cash with remarkable efficiency. Roper had deployed over $4 billion in technology acquisitions since 2010, and the returns on that capital far exceeded what the legacy industrial portfolio could generate.

The numbers told a clear story: every dollar Roper invested in software businesses generated more cash, faster, with less risk, than every dollar invested in industrial businesses. The CROI metric, which Jellison had introduced nearly two decades earlier, was doing exactly what it was designed to do, guiding the company toward its highest-return opportunities and away from capital-intensive operations that dragged on performance.

But 2018 also brought loss. Brian Jellison, who had been battling health issues, stepped down from the CEO role in September 2018, handing the reins to his protege Neil Hunn. Less than two months later, on November 2, 2018, Jellison passed away at his home in Sarasota, Florida, at the age of 73, surrounded by his family.

He had spent his final years ensuring the succession was clean, the playbook was documented, and the culture was strong enough to endure without him. The board, the management team, and the investor base all knew what Roper was. The question was whether the machine could keep running without its architect.

VII. The Neil Hunn Era: Scaling the Platform (2018-Present)

Neil Hunn had been preparing for this moment for seven years. His background was different from Jellison's in almost every way, and yet it was perfectly suited to the challenge of scaling what Jellison had built.

A graduate of Miami University of Ohio with a finance and accounting degree, Hunn earned his MBA at Harvard Business School and spent his early career in strategy consulting at the Parthenon Group and Deloitte Consulting. He then moved to CMGI, an internet incubator during the dot-com era, where he served as Vice President of Corporate Development. CMGI was a wild ride through the internet bubble and its aftermath, and the experience gave Hunn a firsthand education in the difference between businesses that generated real cash flow and businesses that ran on hype.

But it was his decade at MedAssets, a healthcare SaaS company, that truly shaped his approach to business. At MedAssets, Hunn served as EVP and CFO, then as President of Revenue Cycle Technology, leading the company's IPO and several M&A transactions. He understood software economics from the inside, having lived through the full lifecycle of building, scaling, and monetizing a SaaS platform. While Jellison had come to software as a brilliant outsider who recognized its superior economics, Hunn was a software native who understood its operational nuances.

Hunn joined Roper in 2011 as Group Vice President of the medical segment. He proved himself as an operator and a dealmaker, and Jellison promoted him to EVP and COO in 2017. He became President and CEO on September 1, 2018, at approximately age 47. He inherited a company that was already mid-transformation, with a proven playbook and a strong pipeline of acquisition opportunities.

The question was whether he could scale the model to a much larger asset base without diluting the returns.

The answer came quickly, and it was not what anyone expected. Hunn's first major strategic initiative was not an acquisition but a divestiture, a series of them, in fact. This was a bold move. Jellison had built Roper by acquiring. Hunn announced his arrival by selling.

In January 2022, Roper sold Zetec, an industrial inspection business, for $350 million. In March 2022, it divested TransCore, the toll collection business that had been part of the Jellison transformation, for $2.68 billion. Importantly, Roper retained DAT, the freight matching platform, which by this point had become far more valuable than the toll collection business it had originally been bundled with.

And in November 2022, Roper completed the most dramatic separation of all: it sold a 51% stake in 16 of its legacy industrial businesses to Clayton, Dubilier & Rice for approximately $2.6 billion. The new entity, called Indicor, encompassed businesses like Roper Pump, the company's original industrial heritage, along with names like AMOT, Cornell, Dynisco, and Struers. These 16 businesses had generated approximately $940 million in revenue and $260 million in EBITDA in 2021. Roper retained a 49% minority stake. The sale was described internally as "the final step in the divestiture strategy."

The divestiture of Indicor was symbolically and strategically profound. Roper was selling its own origin story, the pump businesses and industrial products that George D. Roper had built 130 years earlier. The company that had started by making pumps in Commerce, Georgia, would no longer make pumps.

But Hunn understood that sentimentality had no place in capital allocation. The industrial businesses generated lower CROI than the software portfolio, required more capital expenditure, and grew more slowly. Every dollar of cash flow they generated was a dollar that could be more productively deployed in software acquisitions. By selling them, Roper was not just raising capital; it was sharpening its identity and concentrating its portfolio on the highest-return assets.

The proceeds from the divestitures funded an acceleration of the acquisition engine, but the most important deal of the Hunn era actually predated the divestitures. In September 2020, Roper completed the $5.35 billion acquisition of Vertafore, the leading provider of software to the property and casualty insurance distribution industry. To understand why this deal mattered so much, consider how insurance distribution works in America. Independent insurance agents, the people who sell auto, home, and commercial policies to businesses and consumers, need software to manage their entire workflow: quoting, binding, policy administration, claims, and carrier relationships. Vertafore's software was the operating system for this industry, used by approximately 20,000 agencies across North America.

Vertafore had approximately $510 million in revenue at the time of acquisition and was growing organically as the insurance industry continued its slow but steady digitization. The switching costs were enormous. An insurance agency that had built its entire operation around Vertafore's platform, training its staff, configuring its workflows, connecting to carriers, would face months of disruption and significant risk if it attempted to migrate to a competitor. These are exactly the characteristics that Roper prizes: mission-critical software, high switching costs, recurring revenue, and a fragmented customer base where no single client represents meaningful concentration risk. Vertafore remained the largest acquisition in Roper's history, and its performance since closing validated the thesis.

The pace of dealmaking under Hunn accelerated further in subsequent years. In 2022, Roper acquired Frontline Education for approximately $3.725 billion in enterprise value, adding K-12 school administration software to the portfolio. Once again, the seller was Thoma Bravo, continuing the long-standing pattern of Roper buying from PE sponsors. In 2023, Roper acquired Syntellis for approximately $1.25 billion, adding healthcare financial performance management to its portfolio and combining it with the existing Strata Decision business to create a more comprehensive offering for hospitals and health systems.

The following year, 2024, was a blockbuster: Roper deployed $3.6 billion in acquisitions, highlighted by Procare Solutions for approximately $1.75 billion and Transact Campus for roughly $1.6 billion. Procare was the leading software platform for early childhood education, managing enrollment, billing, attendance, parent communication, and classroom management at childcare centers across the country. It is the kind of business that perfectly exemplifies the Roper thesis: a small childcare center with 50 children and a handful of staff cannot afford to lose its management software, and once it is trained on Procare's system, the hassle and risk of switching is simply not worth the marginal savings from a cheaper alternative. Transact Campus provided campus technology and payment solutions and was combined with CBORD, Roper's original pure software acquisition from 2008, creating a formidable platform serving dining, ID card, and campus commerce operations at universities and healthcare facilities.

In April 2025, Roper acquired CentralReach for $1.85 billion gross, with a net cost of approximately $1.65 billion after tax benefits. CentralReach provided SaaS solutions for applied behavior analysis therapy providers serving individuals with autism and intellectual or developmental disabilities. ABA therapy is one of the fastest-growing areas of healthcare, driven by rising autism diagnosis rates and expanding insurance mandates for coverage. CentralReach's market was growing at more than 20% organically, and the deal was purchased from Insight Partners. In July 2025, Roper added Subsplash for $800 million, a software and fintech platform serving faith-based organizations, purchased from K1 Investment Management. Churches and religious organizations, it turns out, need the same kinds of software tools that businesses do: donor management, event coordination, communication platforms, and payment processing. Subsplash had built a dominant position in this underserved vertical.

Bolt-on acquisitions in 2025 further strengthened existing platforms. Orchard Software, acquired for approximately $175 million, was integrated into Clinisys, Roper's laboratory information systems business. Convoy, purchased for around $250 million, was folded into DAT, strengthening the freight matching platform that had originated with the TransCore acquisition two decades earlier.

By the end of 2025, Roper's portfolio comprised 37 total acquisitions, heavily concentrated in Healthcare IT, Education Technology, Legal Software, Government Contracting Software, and Insurance Technology. Neil Hunn had not changed the playbook. He had scaled it, completing larger and more frequent deals while maintaining the discipline that Jellison had instilled. He had also added new dimensions to the capital return story, initiating Roper's first meaningful share repurchase program and growing the dividend. The Roper machine was running, and it was running faster than ever.

VIII. Business Model & Operating Philosophy

To understand why Roper works, you have to understand three interlocking pieces: the operating model, the acquisition criteria, and the capital allocation flywheel.

The operating model is radical in its simplicity. Each business unit operates autonomously, with its own leadership team, its own P&L, and its own strategic plan. Corporate headquarters in Sarasota, Florida, employs a skeleton crew relative to the company's scale, roughly 60 people overseeing an enterprise with approximately 18,200 employees that generates nearly $8 billion in revenue. There is no centralized procurement, no shared services center, no corporate-wide IT platform. Each business serves a specific niche market with specialized products, and the leaders of those businesses know their customers, competitors, and technologies far better than any corporate executive ever could.

This decentralization is not abdication. Roper's corporate team maintains rigorous oversight through financial reporting, CROI tracking, and regular engagement with business unit leaders. When a business underperforms, corporate knows immediately and engages with the management team to understand the root cause. But the remedies come from the business units themselves, not from headquarters. This model attracts a specific type of leader: entrepreneurial operators who want the resources and stability of a large public company without the bureaucratic constraints that typically come with it. A common refrain among Roper business unit leaders is that they feel like they are running their own company, with the added benefit of access to Roper's balance sheet and acquisition expertise.

The contrast with other conglomerates is stark. At most large holding companies, corporate mandates dictate everything from IT systems to procurement vendors to HR policies. Business unit leaders spend a significant portion of their time managing upward, attending corporate meetings, and filling out compliance reports rather than serving customers and growing their businesses. At Roper, that overhead simply does not exist. The tradeoff is that Roper cannot achieve the synergies that come from centralization, shared procurement savings, common technology platforms, cross-selling between divisions. Roper accepts that tradeoff because it believes the cost of centralization, in terms of lost speed, lost accountability, and lost entrepreneurial energy, exceeds the benefits.

The acquisition criteria have been refined over two decades but remain remarkably consistent. Roper targets market-leading businesses in defensible niches, companies that are number one or number two in their specific vertical. The ideal target has gross margins above 40%, high recurring revenue, low capital requirements, strong management that will stay post-acquisition, and modest sensitivity to macroeconomic cycles.

The business should serve customers for whom the product is mission-critical, meaning the cost of switching or going without far exceeds the subscription price. Think of a childcare center that runs its entire operation on Procare's software: enrollment, billing, attendance tracking, parent communication, licensing compliance. Ripping out that system and replacing it with a competitor would mean weeks of downtime, staff retraining, data migration risk, and the potential for errors that could affect licensing compliance. The same logic applies to a government contractor whose project management, timekeeping, and financial reporting all depend on Deltek. Or an insurance agency whose quoting, policy administration, and carrier connectivity all run through Vertafore. These are not products that get canceled in a downturn. They are too embedded to remove.

The capital allocation flywheel is what ties everything together and creates the compounding effect that has driven shareholder returns. Roper's software businesses generate strong free cash flow with minimal reinvestment requirements. A software business does not need new factories when it grows. It needs a few more servers, perhaps some additional developers, and customer support staff. The marginal cost of serving an additional customer is close to zero. That means the vast majority of incremental revenue falls straight to cash flow. That cash flows upstream to corporate, where it is redeployed into the next acquisition. The acquired business then generates its own cash flow, which flows upstream and funds the next deal. Each turn of the flywheel makes the enterprise larger, more diversified, and more cash-generative.

Roper's capital return to shareholders has also evolved over time. The company has maintained a dividend for over 30 consecutive years. Under Hunn, Roper initiated its first meaningful share repurchase program in 2025, buying back 1.12 million shares for $500 million and authorizing an additional $3 billion in repurchase capacity. This was a notable shift; Jellison had always preferred to deploy every available dollar into acquisitions rather than buy back stock. Hunn's willingness to add buybacks as a tool suggests confidence that the company can simultaneously fund acquisitions, return capital to shareholders, and manage leverage. But the primary use of capital remains acquisitions, which historically have generated higher returns than buybacks at prevailing valuations.

The financial results speak for themselves. In 2024, Roper generated $2.28 billion in adjusted free cash flow, surpassing the $2 billion threshold for the first time. By 2025, free cash flow grew further to $2.47 billion, representing a 31% margin on revenue. Revenue composition tells the software story clearly: recurring software revenue reached $4.48 billion in 2025, representing 57% of total revenue, with an additional $833 million in reoccurring revenue, that is, revenue that recurs predictably but is not technically contractual, $814 million in non-recurring software, and $1.77 billion in product revenue. The gross margin was 69.2%, an extraordinary number for a company that still has a "Technology Enabled Products" segment with physical products.

The question investors naturally ask is: why software? The answer is embedded in the CROI framework, but it also reflects deeper structural truths about the software business model. Software businesses have almost no physical assets. There are no factories to maintain, no inventory to manage, no heavy equipment to depreciate. Once the code is written and the platform is built, the marginal cost of serving an additional customer is close to zero. A new Procare customer does not require Roper to build a new manufacturing line. It requires provisioning an account on an existing cloud platform. Switching costs are enormous because enterprise software becomes embedded in a customer's workflows, data structures, reporting processes, and institutional knowledge. Years of historical data, custom configurations, and trained staff create a moat that no competitor can breach simply by offering a cheaper product.

And the subscription model provides recurring revenue visibility that makes forecasting and capital planning dramatically easier than in project-based or product-based businesses. When 75% of your revenue is under annual or multi-year contracts, you enter each fiscal year with a high degree of certainty about your baseline financial performance. For a company that measures success through CROI and deploys capital based on cash flow forecasts, that predictability is invaluable. Software, in short, is not just a good business. For a company with Roper's capital allocation model, it is the ultimate asset class.

IX. Competitive Analysis & Market Position

Roper Technologies sits within a small but distinguished cohort of companies that have transformed from industrial manufacturers into technology-enabled compounders. The most frequently cited peers are Danaher, AMETEK, and IDEX, but each has followed a meaningfully different path, and the differences are instructive.

Danaher, the $200 billion-plus life sciences and diagnostics conglomerate, was founded by the Rales brothers in the 1980s and represents perhaps the most celebrated serial acquisition story in modern American business. Danaher's secret weapon is the Danaher Business System, or DBS, a kaizen-influenced operating system inspired by the Toyota Production System that standardizes processes across acquired businesses. When Danaher acquires a company, it does not leave it alone. It deploys DBS teams to map processes, eliminate waste, improve quality, and drive continuous improvement. This is the opposite of Roper's approach. Where Roper preserves autonomy and measures outcomes through CROI, Danaher prescribes a specific methodology for how operations should be run. Both approaches work, but they attract fundamentally different types of businesses and management teams. A founder who wants to maintain operational independence would choose Roper. A company that needs operational improvement would benefit from Danaher. Notably, former Danaher CEO Thomas P. Joyce Jr. now sits on Roper's board, suggesting a degree of mutual respect between the two philosophies.

AMETEK, with a market capitalization exceeding $30 billion, has focused on precision electronic instruments and electromechanical devices, targeting 10%-plus return on invested capital by year three of each acquisition. AMETEK's niche is narrow and deep: analytical instruments, process and specialty sensors, electrical interconnects, and specialty electronic components. It has not attempted a software pivot comparable to Roper's, instead maintaining its focus on the physical instruments that generate high margins through technical differentiation. IDEX, at roughly $14 billion in market cap, remains closest to its industrial roots in specialized pumps and fluid handling, the very market that Roper exited when it divested its industrial businesses to CD&R.

What distinguishes Roper from this peer group is the purity and completeness of its software pivot. At 76% software revenue as of 2024, Roper has gone further than any of its industrial-origin peers in shedding physical manufacturing. Danaher still operates complex laboratory equipment and diagnostic instruments that require significant manufacturing capabilities. AMETEK builds precision sensors and motors. IDEX makes pumps and flow control devices. Roper has systematically divested nearly all of its physical manufacturing businesses and replaced them with vertical software platforms. The result is a margin and CROI profile that none of its industrial-origin peers can match.

There is also a useful comparison to be drawn with Constellation Software, the Canadian serial acquirer led by Mark Leonard, which has built a vast empire of vertical market software businesses through hundreds of small acquisitions. Constellation and Roper share the same fundamental thesis, that vertical software businesses in niche markets are among the most attractive assets in the world, but they approach it differently. Constellation focuses on smaller deals, often in the tens of millions, and makes dozens of them per year. Roper focuses on larger deals, typically in the hundreds of millions to billions, and makes a handful per year. Both approaches have generated exceptional returns for shareholders, validating the underlying thesis about vertical software economics.

Myth vs. Reality: The Consensus Narrative on Roper

There are a few common misconceptions about Roper that deserve examination. The first is that Roper is simply a conglomerate that benefits from a favorable accounting treatment. Critics argue that Roper's adjusted earnings exclude significant amortization of intangibles from acquisitions, making the company appear more profitable than it is. This is a legitimate accounting debate. Roper's GAAP net income in 2024 was $1.55 billion, while adjusted net income was $1.98 billion. The difference primarily reflects amortization of acquired intangible assets, a real non-cash expense that GAAP requires but that many investors view as economically irrelevant for software businesses. The amortization of intangible assets was $776 million in 2024. Whether this is "real" depends on your view of whether acquired software assets actually depreciate in value over time, or whether, in many cases, they actually appreciate as the business grows its customer base and pricing power.

The second myth is that Roper is overpaying for acquisitions and surviving on financial engineering. The evidence does not support this. Roper has maintained organic revenue growth in the mid-single digits consistently, which indicates that acquired businesses continue to grow and create value after the transaction closes.

If Roper were simply buying revenue at inflated multiples and watching it deteriorate, organic growth would be negative. Instead, the opposite is occurring: acquired businesses are growing revenue and expanding margins within the Roper portfolio. That is the hallmark of good acquisitions, not financial engineering.

The third myth is that the "Roper premium" is simply a market mispricing that will eventually correct. This view underestimates the structural advantages of owning monopoly-like positions in niche vertical software markets. A 69% gross margin and 32% free cash flow margin are not artifacts of accounting. They reflect a genuine competitive position in markets where switching costs are high, competition is limited, and pricing power is strong.

To evaluate Roper's competitive position through a structural lens, consider the five forces that shape its markets.

Threat of new entrants: Low. Building a competing product for government contractor project management or insurance agency management requires not just software development capability but deep domain expertise, regulatory knowledge, and years of customer relationship building. A startup cannot simply write code and expect to win customers away from Deltek. It needs to understand the Federal Acquisition Regulation, Cost Accounting Standards, and dozens of agency-specific reporting requirements. That expertise takes years to develop.

Supplier bargaining power: Limited. Roper's businesses are primarily software, and the key input is engineering talent. While expensive, software engineers are available in competitive labor markets, and Roper's businesses are not dependent on any single supplier or technology vendor.

Customer bargaining power: Constrained by high switching costs. Once an organization builds its operations around Deltek or Vertafore or Procare, the cost and risk of migrating to an alternative is prohibitive. Years of data, configured workflows, trained staff, and regulatory compliance processes create a moat that no competitor can breach simply by offering a lower price.

Threat of substitutes: Moderate and evolving. The primary threat comes from horizontal software platforms and emerging AI-driven tools. However, mission-critical vertical software has historically been resistant to displacement by generalist platforms because the domain-specific functionality, regulatory compliance, and data structures are too specialized.

Competitive rivalry: Moderate to low. In most of Roper's niches, there is one dominant player, usually a Roper subsidiary, and a long tail of smaller competitors who lack the scale, customer base, or feature depth to win enterprise accounts.

Through the lens of Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers framework, Roper possesses several durable competitive advantages. Its individual businesses benefit from switching costs, the most powerful of the seven forces for enterprise software companies. DAT benefits from network effects, where the platform becomes more valuable as more participants join, a classic two-sided marketplace dynamic. Roper's corporate acquisition capability constitutes process power, an institutionalized method of sourcing, evaluating, and integrating acquisitions that has been refined over 37 transactions and is difficult to replicate. And the company benefits from scale economies in its ability to access capital markets at favorable rates and to attract acquisition targets that prefer a permanent home to another PE cycle.

The "Roper Premium" that the stock commands relative to pure industrial companies reflects the market's recognition that this is not a conglomerate discount situation. It is a portfolio of monopoly-like positions in niche vertical software markets, held together by a capital allocation engine that has compounded shareholder value for over two decades.

Whether the premium is justified at any given price is a question for individual investors, but the structural advantages are real and well-documented across more than 20 years of financial results.

X. Playbook: Investment & Business Lessons

The Roper story distills into a handful of lessons that are easy to articulate and extraordinarily difficult to execute. For investors, strategists, and business leaders, these lessons have implications that extend far beyond a single company's stock price.

The Power of a Consistent Metric

CROI was not a passing management fad or a buzzword deployed in investor presentations. It was a 20-year commitment to a single framework for evaluating business quality and capital allocation. Every acquisition, every divestiture, every internal investment decision was filtered through the same lens. This consistency created institutional clarity. Everyone in the organization, from the CEO to the business unit controller, understood what "good" looked like.

Most companies cycle through strategic frameworks every few years as leadership turns over. A new CEO arrives with new metrics, new priorities, and new initiatives. The organization spends a year learning the new system, another year implementing it, and by the time it is embedded, the next CEO arrives with a different playbook. Roper's refusal to abandon CROI, even as the portfolio evolved from pumps to software, was a competitive advantage in itself. When your entire organization has internalized a single metric for two decades, the speed and quality of decision-making improves dramatically.

Patience in Transformation

Roper's metamorphosis from industrial manufacturer to software conglomerate took more than 20 years. Jellison joined in 2001 and made his first software acquisition in 2008. The name change to Roper Technologies did not come until 2015. The final divestiture of industrial businesses happened in 2022. This was not a pivot; it was an evolution.

The evolution required a board of directors willing to support a multi-decade strategy and a shareholder base that understood what they owned. Most public companies face overwhelming pressure to deliver results on quarterly timelines. Roper's ability to maintain strategic patience in a short-term-oriented market is one of its most underappreciated achievements. The lesson for other companies contemplating transformations is sobering: if you are not willing to commit for at least a decade, do not start.

Decentralized Excellence

The tension between corporate control and business unit autonomy is one of the oldest problems in management theory. Roper resolved it by choosing a side: extreme autonomy within a framework of financial accountability. The approach only works if you hire the right leaders, measure the right metrics, and resist the temptation to meddle when things get uncomfortable.

Jellison's Socratic model, asking questions rather than issuing directives, required a level of self-discipline that most executives find impossible to sustain. When a business unit is underperforming, the natural instinct of a corporate leader is to intervene, to send in a task force, to impose new processes, to take control. Jellison resisted that instinct. He trusted that the right leaders, given the right metrics and the right incentives, would find the right solutions. And if they could not, he replaced them, quickly and decisively.

Succession Planning as a Core Competency

Jellison did not just build Roper; he built Neil Hunn. The seven-year apprenticeship from Group VP to EVP and COO to CEO ensured that the transition was seamless when Jellison's health declined. Many serial acquirers falter when their founding CEO departs because the acquisition skill was personal, not institutional. The deal flow depended on the founder's relationships. The due diligence depended on the founder's judgment. The integration depended on the founder's authority.

Jellison made it institutional, creating processes, criteria, and a team that could execute the playbook without him. The fact that Roper has continued to accelerate its acquisition pace and maintain its return profile under Hunn is the ultimate testament to Jellison's leadership. Building a great company is one achievement. Building one that continues to compound after you leave is a rarer and arguably greater one.

The Willingness to Shed Identity

Selling Roper Pump, the literal namesake business, required a kind of strategic ruthlessness that few management teams possess. Most companies cling to their legacy businesses out of sentimentality, inertia, or fear of what the remaining entity will look like. Boards resist divesting the "core" business because it feels like admitting failure.

Roper sold its past to fund its future, and the shareholder returns validated the decision decisively. The lesson for other industrial companies contemplating software transformations is uncomfortable but clear: you cannot straddle two worlds forever. At some point, you have to choose. And the longer you wait to choose, the more expensive the transition becomes, because the capital tied up in the legacy business is capital that could have been compounding in higher-return assets.

Building Acquisition Capabilities as an Institutional Asset

Perhaps the most underappreciated lesson from Roper is that acquisition capability itself is a competitive advantage. After 37 transactions over two decades, Roper has built an institutional knowledge base in deal sourcing, due diligence, valuation, negotiation, and post-acquisition governance that new entrants to the serial acquisition game simply cannot match.

Roper's team knows which PE firms are likely to sell, when their fund timelines create pressure, which types of businesses thrive under Roper's decentralized model, and which types do not. This pattern recognition, accumulated over hundreds of evaluated deals and dozens of completed transactions, is a form of institutional capital that does not appear on the balance sheet but is arguably one of Roper's most valuable assets.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case & Future Outlook

The Bear Case

The most common concern is acquisition multiples, and it is a legitimate one. As Roper has grown, it has been forced to pursue larger targets, and larger targets command higher prices. The early Jellison-era deals like Neptune and TransCore were acquired for relatively modest multiples of revenue. The Vertafore deal at $5.35 billion represented a much richer valuation, and more recent deals like CentralReach and Frontline Education have been priced at levels that leave less margin for error. In competitive auctions for high-quality vertical software businesses, Roper now faces other well-capitalized strategic buyers, Constellation Software, Tyler Technologies, and others, as well as private equity firms like Thoma Bravo, Vista Equity, and Insight Partners who are armed with billions in dry powder. If multiples continue to expand, the returns on future acquisitions may not match the historic track record, and the compounding engine slows.

A more immediate concern emerged in late 2025 and early 2026: the impact of government cost-cutting initiatives, particularly the Department of Government Efficiency, on Deltek's government contractor customer base. If federal contract spending is reduced or delayed, the government contractors who rely on Deltek's software may face their own revenue pressures, potentially leading to consolidation, downsizing, or subscription downgrades. Management acknowledged this headwind in its 2026 guidance, which does not assume improvement at Deltek's GovCon business and also does not assume recovery in DAT's freight market or at Neptune, where copper tariffs created short-term disruption. The cautious guidance suggests management sees multiple pockets of near-term softness across the portfolio.

The AI disruption risk is also real but nuanced, and reasonable observers disagree about its severity. Generative AI could theoretically make it easier for horizontal platforms to encroach on the vertical niches that Roper's businesses occupy. Consider the following scenario: a government contractor currently pays Deltek a significant annual subscription for project management, financial reporting, and compliance. What if a next-generation AI platform from Microsoft, Google, or a well-funded startup can deliver 80% of that functionality at half the price, with the additional intelligence to handle the regulatory nuances that currently require specialized software? The switching cost moat weakens in that scenario. However, defenders of Roper's position point out that mission-critical enterprise software has historically been resistant to platform shifts because the data, integrations, regulatory compliance requirements, and institutional knowledge embedded in the existing system create barriers that raw functionality cannot overcome. A government contractor's Deltek instance contains years of project data, audit trails, and configured workflows. Ripping that out is not a software decision; it is an organizational one.

Integration risk grows with deal size and frequency. Roper's light-touch integration model assumes that acquired management teams are excellent and will remain motivated post-close. When you are making one or two acquisitions a year, corporate leadership can maintain close relationships with every business unit leader. When you are deploying $3 billion to $4 billion a year across multiple deals, the demands on corporate bandwidth increase significantly. As the portfolio grows to 37-plus businesses, even the Socratic model requires more people asking the right questions. And there is always the question of whether the institutional knowledge that Jellison embedded in Roper's culture will gradually erode as the company grows further from his era. Culture is fragile, and the further you get from the founder's touch, the harder it is to maintain the original intensity.

There is also a financial leverage consideration worth monitoring. Roper's net debt-to-EBITDA ratio rose from 2.6 times at the end of 2024 to 2.9 times by December 2025, a reflection of the $3.3 billion deployed in acquisitions during the year. That level is manageable but leaves the company somewhat exposed if credit markets tighten or if an acquisition underperforms. The company raised $2 billion in new senior notes during 2024 and issued additional debt in 2025 to fund acquisitions, pushing total gross debt above $9 billion.

Roper has historically been disciplined about paying down debt after large acquisitions, and its strong free cash flow generation provides substantial capacity for deleveraging. Between the end of 2016 and early 2018, for example, Jellison reduced gross debt by $1.6 billion while simultaneously making acquisitions. But the combination of larger deals and ongoing M&A activity means that leverage levels deserve ongoing attention.

The Bull Case

The most compelling argument for Roper is the sheer size of the opportunity in vertical software. The total addressable market for industry-specific software runs into the hundreds of billions of dollars, and it remains highly fragmented. For every Deltek or Vertafore, there are dozens or hundreds of smaller vertical software businesses that dominate their niches but have not yet been acquired by a company with Roper's capital and operating model. The pipeline of opportunities is, by management's own admission, large and growing. Recent deals like Subsplash, serving faith-based organizations, and CentralReach, serving ABA therapy providers, demonstrate that Roper continues to find new verticals to enter.

The competitive moats in Roper's existing portfolio are deep and reinforcing. Network effects in businesses like DAT create winner-take-most dynamics that are almost impossible for competitors to overcome. The freight matching platform gets more valuable with every additional trucker and shipper, creating a virtuous cycle that entrenched players cannot easily disrupt. Pricing power in mission-critical applications means that Roper's businesses can raise prices at rates that exceed inflation without meaningful customer churn. When your software is the backbone of a customer's operations, a 5% to 7% annual price increase is a rounding error compared to the cost and risk of switching.

The free cash flow generation, which surpassed $2.4 billion in 2025, provides enormous capacity for continued M&A, debt reduction, and shareholder returns. Roper has also demonstrated that it can create value by combining related businesses within its portfolio, as it did when it merged Transact Campus with CBORD and when it combined Syntellis with Strata Decision. These intra-portfolio combinations are a source of value that is difficult for outside observers to quantify but real nonetheless.

From a 7 Powers perspective, Roper's most durable advantages are switching costs at the individual business level, network effects at DAT, and process power at the corporate level. The process power advantage is perhaps the most underappreciated: Roper has spent 20-plus years building an institutional capability in acquisition sourcing, evaluation, and integration that cannot be replicated by a company that decides tomorrow to become a serial acquirer. It takes years to build the relationships with PE sponsors, the pattern recognition in due diligence, and the post-acquisition governance model that Roper has refined through dozens of transactions.

For those tracking Roper's ongoing performance, two KPIs matter above all others. First, organic revenue growth, which measures the health of the existing portfolio independent of acquisitions. Roper has delivered consistent mid-single-digit organic growth, with 6% in 2024 and 5% in 2025, reflecting pricing power and modest volume growth in its end markets. If organic growth decelerates below 4% for an extended period, it would suggest weakening competitive positions or market saturation in the underlying niches. Second, free cash flow conversion, the ratio of free cash flow to adjusted net income. Roper's ability to convert earnings to cash at a rate consistently above 100% is the foundation of the compounding model. If this ratio deteriorates, it may indicate that acquisitions are consuming more capital than expected, that the portfolio is becoming more asset-intensive, or that management is underinvesting in the existing businesses.

The 2026 guidance of adjusted diluted EPS of $21.30 to $21.55 implies approximately 8% total revenue growth with 5% to 6% organic growth, consistent with the company's long-term trajectory. Management also repurchased $500 million in shares during 2025 and authorized an additional $3 billion buyback, adding a new dimension to the shareholder return story that did not exist during the Jellison era. Roper enters 2026 with the most software-pure portfolio in its history, a proven leadership team, significant M&A firepower, and a 15-year total shareholder return of nearly 984%, a CAGR of approximately 17.2% that meaningfully outpaced the S&P 500's roughly 600% return over the same period.

XII. Epilogue & Reflections

There is something quietly remarkable about a company that began by casting gas stove parts in a Cleveland workshop in 1890 and now generates nearly $8 billion a year from software that manages childcare centers, government contracts, insurance agencies, freight logistics, churches, and autism therapy clinics. The distance between those two realities is not measured in years alone but in the quality of the decisions that connected them.

The transformation did not happen through a single visionary bet or a lucky acquisition. It happened through decades of disciplined capital allocation, a willingness to measure everything through one consistent metric, and the rare corporate courage to sell the businesses that made the company what it was in order to become what it needed to be. When Roper divested Roper Pump, its literal namesake business, the original product that George D. Roper built in the 1890s, it was sending a message that few companies are brave enough to send: the past is less important than the future.

Brian Jellison's legacy extends beyond the financial returns, extraordinary as they are. He demonstrated that an American industrial company could reinvent itself completely, not through cost-cutting, not through financial engineering, not through a flashy merger of equals, but through a superior understanding of business quality and capital deployment.

He created a framework, CROI, that allowed an entire organization to distinguish between businesses that created value and businesses that consumed it. He built a culture that attracts operators who want autonomy and accountability in equal measure, the kind of people who thrive when given full responsibility and measurable goals but chafe under bureaucratic oversight.

And he planned his own succession with the same rigor he applied to acquisitions, ensuring that the playbook would outlast the architect. When Indiana University dedicated the Brian D. Jellison Studio at the Kelley School of Business in September 2022, it was a fitting tribute to a man who had quietly become one of the most influential business builders of his generation.