Southern Copper Corporation: The Integrated Mining Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

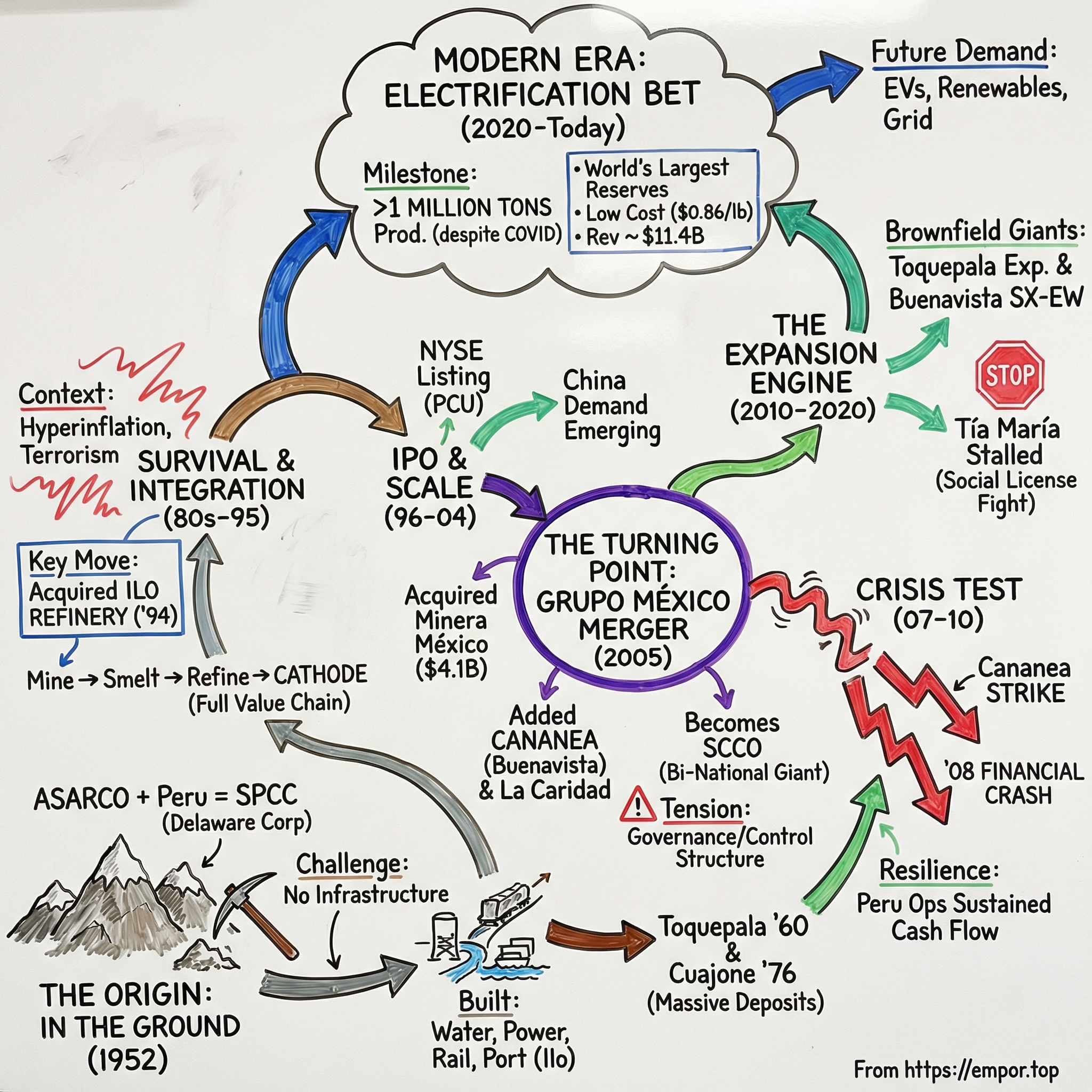

Picture southern Peru in 1952: high desert air, brutal sun, and the Andes rising like a wall above the Pacific. In the Tacna region, a small group of American geologists is hiking across rock and dust, mapping a copper deposit so massive it will end up reshaping an industry. This isn’t a story that starts in a boardroom. It starts in the ground.

Today, that same lineage sits inside Southern Copper Corporation: a copper heavyweight with a market cap north of $67 billion, $11.4 billion in 2024 revenue, and the largest copper reserves on Earth. But the numbers are just the outcome. The real question is the journey: how did a Delaware corporation created to develop a remote Peruvian mine become one of the core assets of a Mexican industrial empire? And why does that origin story suddenly matter again, right as the world starts talking about a “copper supercycle”?

Southern Copper’s history is really three stories layered on top of each other.

First, it’s the relentless pursuit of scale in a business where scale is survival—where costs, logistics, and geology decide who wins.

Second, it’s the uneasy partnership between foreign capital and resource-rich developing nations, with all the politics, labor dynamics, and national priorities that come with it.

And third, it’s about patience: the kind required to build not just mines, but an integrated machine—mining, smelting, refining—across borders and through decades of instability.

In this episode, we’ll follow the arc from ASARCO’s postwar ambition, through Peru’s boom-and-bust years, to the 2005 mega-merger that created the modern company under Grupo México. We’ll hit the moments that tested the whole system—labor strikes, financial shocks, environmental battles—and end in the present, where electrification and renewable energy have made copper strategic again in a way the world hasn’t seen since the first great wave of wiring up cities.

So let’s start where all great copper stories start: deep in the earth, long before anyone knew what the demand curve would look like.

II. The Foundation: ASARCO, Peru, and Early Days (1952–1980s)

In the years after World War II, American industry ran into a quiet but very real constraint: copper. The war had devoured it—shell casings, wiring, radios, communications gear—and the U.S. couldn’t assume its domestic supply would keep up forever. So the search widened. One of the biggest bets landed in an unlikely place: the stark, high-altitude deserts of southern Peru.

Leading the charge was the American Smelting and Refining Company—ASARCO. It wasn’t a scrappy upstart. ASARCO had been built in 1899, in the consolidation era of the American West, and by the middle of the 20th century it had become one of the world’s major non-ferrous metals players. It had the engineers, the capital, and the institutional muscle to take on projects that looked impossible on a map.

In 1952, ASARCO and its partners formed Southern Peru Copper Corporation in Delaware. Delaware was the corporate wrapper—efficient courts, predictable rules. Peru was the reality. Every ton of value would have to be dug, hauled, processed, and shipped from thousands of miles away.

Their prize was Toquepala: a gigantic porphyry copper deposit in Tacna, perched about 3,100 meters above sea level. But ore bodies don’t come with permissions attached. To develop Toquepala, the company needed a bilateral agreement with the Peruvian government—part commercial deal, part diplomatic negotiation—at a moment when countries across Latin America were becoming more insistent that natural resources should fuel national development. Peru wanted jobs, infrastructure, and foreign exchange. ASARCO wanted long-term, enforceable access to a world-class deposit. The agreement that took shape was a trade: mining rights in exchange for commitments on employment, development, and tax revenue.

Even with a deal in hand, the next challenge wasn’t geology. It was everything else.

Toquepala sat in a landscape that didn’t offer the basics an industrial operation needs: reliable water, dependable power, modern transport, or a port. So the company built them. Engineers designed and constructed a water pipeline from Andean snowpack, power generation to run the plant, rail to move concentrate, and a port at Ilo to get copper onto ships headed for global customers. Southern Peru Copper wasn’t just opening a mine. It was assembling an entire industrial ecosystem in a place that had never hosted one.

Commercial production at Toquepala began in 1960, and the timing was perfect. Copper demand was roaring. The Vietnam War pulled metal into military supply chains. Electrification pushed copper into homes and transmission lines. And the consumer boom—cars, appliances, televisions—turned copper into a quietly essential ingredient of modern life. Southern Peru Copper had a giant deposit, fresh infrastructure, and a market eager to buy.

But Peru wasn’t a stable backdrop. Politics could turn fast, and did. After a military government took power in 1968, the country moved toward reform and greater state control, nationalizing some foreign holdings and pressuring others. Southern Peru Copper made it through. Its operations were deeply integrated and technically complex—hard to seize and run cleanly without the expertise that built them. Still, the message was unmistakable: in mining, political risk isn’t an edge case. It’s part of the business model.

The company didn’t stop at Toquepala. It expanded within Peru, developing the Cuajone mine in Moquegua, which began production in 1976. Cuajone gave Southern Peru Copper a second major production center—bigger than Toquepala and higher grade—adding both scale and operational resilience. And the company kept pushing down the value chain, investing in refining so it could do more than ship concentrate. The ambition was clear: not just extract copper, but make finished metal in-country.

Then there were the people. These mines weren’t near cities; they were effectively isolated worlds. The company had to house workers, feed them, and provide services for families—schools, hospitals, stores—because there was nobody else to do it. Mining camps like Toquepala became company-run societies. That paternalistic model created stability and loyalty, but it also created dependency—and when tensions rose, they didn’t stay small. Disputes could turn into strikes, and grievances carried extra weight when your employer also controlled your town.

By the early 1980s, Southern Peru Copper had built what many miners aspire to and few actually pull off: an efficient, integrated operation stretching from open-pit mine to refined output. That integrated model—control across the chain—would become a defining advantage. But the decade ahead would pose a harder question: could any operational edge survive what Peru was about to go through?

III. Expansion and Evolution (1980s–1995)

By the mid-1980s, Peru wasn’t just volatile. It was fraying at the seams. Hyperinflation was ripping through the economy, turning wages into yesterday’s news. The Shining Path was waging a brutal insurgency—bombing infrastructure, assassinating officials, and making daily life unpredictable, especially outside the big cities. For Southern Peru Copper, “operating conditions” stopped being a macro section in a report and became the job itself: keep people safe, keep equipment running, keep production moving.

Inside the company, management faced questions no corporate playbook really answers. How do you pay and retain workers when the currency can’t hold value? How do you protect a remote mine when public security is unreliable? How do you keep critical parts and chemicals flowing when logistics break down? The solutions were often practical and imperfect: more compensation tied to dollars, more on-the-fly sourcing, and security arrangements that were necessary but never comfortable.

And still, the company kept building.

The most important milestone came in 1994, when Southern Peru Copper acquired the Ilo Copper Refinery from the Peruvian government, adding about 190,000 tons per year of refining capacity. It was a strategic win. Refining meant cathodes—finished copper metal, the form that trades as a global commodity. It also fit the moment: Peru, under President Alberto Fujimori, was moving through a wave of privatization, and Southern Peru Copper was ready to step deeper into the value chain.

With Ilo, the vertical integration strategy snapped into place. Ore from Toquepala and Cuajone moved through concentrators, then through smelting into blister copper, and finally into refining—ending as cathodes rather than as a partially processed intermediate. Even byproducts mattered. Sulfuric acid from smelting wasn’t just waste; it became something the company could sell into other industrial uses. The logic was simple: in mining, the more steps you control, the less you’re at the mercy of everyone else’s bottlenecks and pricing.

The 1990s also brought a quiet shift in how copper could be produced. Southern Peru Copper kept investing in technology and process improvements, including the 1995 commissioning of the LESDE plant at La Caridad, which processed 60 tons per day, and a new sulfuric acid plant at Ilo with 140,600 tons per year of capacity. Around the industry, solvent extraction-electrowinning—SX-EW—was changing the economics of copper by making lower-grade ore more workable than it had been under traditional methods.

Then came another force the company could no longer treat as secondary: the environment. In the 1950s and 1960s, mining’s footprint was mostly shrugged off as the price of modernization—smelter emissions, tailings, dust. By the 1990s, that shrug stopped working. Pressure rose from regulators, communities, and the broader international context. Southern Peru Copper responded with investments in pollution controls, better tailings management, and more structured community relations—early steps toward the idea that a mine doesn’t just need permits to operate. It needs permission from the people around it.

By the time the company reached the mid-1990s, it had built something tougher than a set of assets. It had built a capability: running complex, integrated operations through instability, upgrading technology while keeping production steady, and expanding even when the outside world kept trying to pull the floor out from under it. That resilience would matter in the next chapter—because the next opportunity wasn’t in the ground. It was in the capital markets.

IV. Going Public and Finding Scale (1996–2004)

In 1996, Southern Peru Copper stepped into a different arena: the public markets. Its shares began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker PCU, alongside a simultaneous listing on the Lima Stock Exchange. The Lima listing tied the company more directly to Peru. The NYSE listing did something else entirely—it plugged a remote Andean mining system into the deepest pool of institutional capital on the planet.

Going public served three different constituencies at once. For ASARCO and the other long-time owners, the IPO finally created liquidity for a stake they’d held for decades. For the company, it opened a new funding channel—capital for expansion that didn’t depend solely on a parent company’s balance sheet or project-by-project borrowing. And for Peru, a NYSE-listed mining champion was symbolic: a sign the country was re-entering global finance after the disorder of the 1980s.

The market backdrop wasn’t smooth. The Asian financial crisis in 1997 hit demand expectations and dragged copper prices down. But the hangover from that crisis revealed a new reality: China was rapidly becoming the marginal buyer that would set the tone for the entire commodity complex. The industry was still early in that realization, but the implication was clear. If demand was about to grow structurally, the winners would be the producers with big reserves and low costs—exactly the profile Southern Peru Copper had spent decades building.

So in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the company doubled down on execution. Mining is brutally simple in concept—move rock, process ore—but the economics are unforgiving. Small savings per pound compound into real advantage at scale. Southern Peru Copper pushed operational improvement: benchmarking against global peers, investing in bigger hauling equipment, squeezing more efficiency out of processing, and tuning the workforce to match what the system actually needed. Those efforts kept the Peruvian operations consistently in the lowest quartile of global cash costs—an edge grounded in high-quality ore, vertical integration, and hard-earned operating experience.

Then, in the early 2000s, copper began to lift. After years stuck in the same range, prices started climbing toward a dollar a pound and beyond, pulled upward by China’s growing demand. For a low-cost producer, that kind of move changes everything. Cash flow starts arriving faster than projects can absorb it, and management faces the question every cyclical business eventually confronts: do you simply harvest the moment, or do you build for the next one?

Southern Peru Copper’s answer wouldn’t come from another incremental expansion in Peru. It would come from a deal—one that would remake the company’s footprint, shift its center of gravity, and ultimately change its identity. And the driving force behind that transformation wasn’t management in Lima or engineers in Tacna. It was the controlling shareholder: a Mexican industrial group with plans far bigger than one country’s mines.

V. The Grupo México Era: The 2005 Mega-Merger

In April 2005, Southern Peru Copper Corporation announced the deal that would redefine it: a merger with Minera México, a Grupo México subsidiary, valued at $4.1 billion. It was done as a stock transaction—Southern Peru issued shares to Grupo México—and when everything closed, Grupo México owned 88.9% of the combined company. The center of gravity moved. Permanently.

To understand why, you have to understand Grupo México. Controlled by the Larrea family and led by chairman Germán Larrea Mota-Velasco, the group had grown far beyond “a mining company.” It was a Mexican conglomerate with serious interests in mining, transportation, and infrastructure—and a clear ambition to build a copper champion that stretched across the Americas. Southern Peru wasn’t just buying assets. It was becoming the platform.

What Southern Peru got in the merger were three major Mexican units.

La Caridad, in Sonora, was a large copper-molybdenum operation with its own smelting and refining footprint—exactly the kind of integrated setup that Southern Peru already believed in.

IMMSA added more polymetallic capacity.

And then there was the crown jewel: Buenavista del Cobre, better known at the time as Cananea. It was one of the world’s largest copper deposits and, crucially, it came with the longest mine life in the company’s portfolio.

But Cananea didn’t come as a clean spreadsheet. It came with history.

The district had been mined since the late 1800s. It had played a role in the Mexican Revolution. Over the decades it had been nationalized, privatized, and repeatedly contested. By 2005, the opportunity was enormous, but so were the frictions: a massive ore body paired with aging infrastructure and labor relations shaped by years of union militancy.

And now management had to fuse two mining systems—Peru and Mexico—into one company.

That meant operating across different regulatory regimes, different labor traditions, and different internal cultures. The Mexican assets brought different accounting approaches, different union contracts, and different environmental requirements. The job wasn’t just “integrate operations.” It was build a single set of systems for reporting and governance that could roll everything up, while still letting local sites run the way they had to run.

The merger also carried a built-in conflict that investors couldn’t ignore. Minority shareholders questioned whether Minera México’s $4.1 billion valuation was fair. Grupo México effectively sat on both sides of the table, and critics argued the structure looked like a related-party transaction designed to favor the controller. That concern didn’t go away—it lingered for years and eventually became litigation—and it set the tone for how markets would view the company’s governance going forward.

In 2010, the branding caught up with the reality on the ground. Southern Peru Copper Corporation became Southern Copper Corporation and adopted the ticker SCCO. The name change was more than cosmetic. This was no longer a company defined by one country’s mines; it was a bi-national copper giant. It still lived on paper as a Delaware corporation, but its operational identity now spanned the Pacific edge of the Americas.

For investors, the 2005 merger created something new: a bigger, more geographically diversified producer with enormous reserves—paired with a more complicated control structure and a dominant shareholder whose priorities might not always match those of minorities. Those tensions would matter. But first, the combined company would have to survive a brutal stretch that tested mining operations in the most old-fashioned way possible: labor, prices, and the cycle turning hard.

VI. Crisis and Recovery: Labor Strikes and Financial Crisis (2007–2010)

In July 2007, the fault lines at Cananea finally snapped. Miners walked out, kicking off what became one of the longest labor disputes in Mexican mining history. The union—led by Napoleón Gómez Urrutia—said the strike was about safety, pay, and a management culture that, in their view, was cutting costs too aggressively. The mine went dark. And it stayed that way for years, until government intervention forced a path back to operations.

For Southern Copper, the strike was a crash course in how Mexican labor politics could differ from Peru’s. Unions existed in both places, but in Mexico they were intertwined with national history and real political power. Cananea in particular carried symbolism: the local union traced its roots back to the 1906 strike that helped ignite the Mexican Revolution. Gómez Urrutia was just as symbolic—and just as divisive. To supporters, he was a champion for workers. To Mexican authorities, he was a wanted man accused of fraud, pushed into exile in Canada.

The practical impact was brutal. Cananea was the company’s biggest Mexican asset, and now it wasn’t producing. That didn’t mean expenses disappeared. A shuttered mine still has to be maintained, still carries fixed costs, and still ties up capital—while every pound of copper left in the ground earns exactly nothing.

Then the cycle turned. In 2008, the global financial crisis hit, and copper—one of the clearest real-time signals of industrial demand—collapsed with it. Prices that had been above $4 per pound earlier in the year fell to below $1.50 by year-end as the world slammed the brakes on construction and manufacturing. Southern Copper’s stock fell hard too. With Cananea offline and the copper market imploding, the company was suddenly dealing with a two-front war: labor disruption in Mexico and collapsing demand everywhere.

The response wasn’t flashy, but it was effective. Management tightened costs and leaned on the asset base that still worked. Peru kept running, and that mattered: Toquepala and Cuajone were low-cost, integrated operations that could still generate cash even when prices were ugly. Expansion plans were reviewed, reshuffled, and slowed where necessary. The company didn’t try to “solve” a cyclical crash with permanent decisions.

At the same time, the governance controversy from the 2005 merger refused to fade into the background. Minority shareholders sued, alleging the Minera México transaction benefited Grupo México at their expense and undervalued what they owned. The case dragged on for years, with claimed damages of more than $1 billion—an enduring reminder of the tradeoff that comes with a controlled-company structure: you get a powerful sponsor, but limited leverage when you disagree with the sponsor’s choices.

By 2010, the clouds finally began to lift. Cananea restarted under the name Buenavista del Cobre, with security forces protecting workers who crossed picket lines. Copper prices recovered off the crisis lows. And Southern Copper raised $1.5 billion in bonds to finance expansion, taking advantage of low rates and renewed investor appetite for the sector. The company had absorbed the shock, preserved its core, and set itself up for the next phase—not just surviving the cycle, but using it as a runway.

VII. The Expansion Machine (2010–2020)

The decade after the financial crisis was when Southern Copper stopped playing defense and started building like it had something to prove. Copper prices recovered and stayed strong for long stretches, with China’s appetite for metal remaining the main current under the market. With the cycle at its back, the company leaned into a simple idea: don’t just run the mines—expand them.

Buenavista del Cobre became the centerpiece of that push. The company added a third SX-EW plant, lifting capacity by 120,000 tons a year, and built a new concentrator that added another 188,000 tons. This wasn’t a tune-up. It was a re-rating of the Mexican business into a true production engine. SX-EW mattered because it broadened what counted as economic ore, making oxide material viable in a way traditional flotation often couldn’t.

Peru was getting its own upgrade. Southern Copper poured $1.3 billion into the Toquepala expansion, breathing new throughput into a mine that had been producing since 1960. A new concentrator and debottlenecking work meant Toquepala could process more ore and ship more concentrate. In parallel, the Buenavista expansion in Mexico—budgeted at $1.2 billion—kept pushing the complex outward, one major piece of infrastructure at a time.

But the expansion story wasn’t all concrete and copper cathodes. It was also about friction—especially in Peru.

Tía María, a proposed mine in Arequipa, turned into a decade-long referendum on whether mining could win public permission, not just government approval. Farmers feared for water supply. Environmental groups warned about impacts on agriculture. Protests repeatedly stopped progress. The project ricocheted through a familiar loop—approved, challenged, pulled back, reapproved—until it became less a single asset than a symbol of how hard new mines had become to build.

In 2018, Southern Copper added another major bet to the pipeline: Michiquillay. The company paid $400 million for the project, a deposit with potential production of 225,000 tons per year. It was an unmistakable signal that Southern Copper was willing to buy growth, not just build it. The catch was location. Michiquillay sat in Cajamarca, a region known for intense anti-mining activism after high-profile conflicts at other projects. The ore body made the risk worth taking, but nobody was pretending it would be easy.

As the company expanded, it also put more weight behind environmental and sustainability efforts. In 2014, Southern Copper received the Fray International Sustainability Award, highlighting work to reduce emissions and manage environmental impacts. Critics argued that “sustainable mining” was a contradiction in terms, but Southern Copper’s posture was clear: if mining was going to keep its license to operate, environmental performance had to be treated like a core operating system, not a side project.

All of this played out against the backdrop of a long-running demand story. China remained the anchor buyer through much of the decade, and a newer narrative started to harden into consensus: electrification would be copper-intensive. Electric vehicles were scaling, and each one used far more copper than an internal combustion car. Renewables and grid upgrades demanded even more. Analysts increasingly warned that supply would struggle to keep up.

By the end of the 2010s, Southern Copper had become what Grupo México set out to build: one of the world’s most efficient major copper producers, with a reserve base that stretched decades into the future—and a development pipeline designed to keep the growth engine running.

VIII. Modern Era: Breaking Records and Future Bets (2020–Today)

In 2020, Southern Copper crossed a psychological threshold that only a handful of miners ever reach: it produced more than a million tons of copper in a single year, hitting 1,001,369 tons. That put it in rare company—alongside names like Codelco, Freeport-McMoRan, and BHP’s Escondida—operators with the scale to shape supply, not just respond to it.

What made the milestone more telling was the timing. The world was shutting down. COVID-19 introduced a new kind of operating risk: sudden work stoppages, broken supply chains, and the simple reality that you can’t run a mine over Zoom. Southern Copper dealt with it the way integrated miners tend to deal with existential problems—by building procedures and grinding through them. Quarantines, testing, and modified operations became part of daily life. The company maintained that copper production was essential economic activity, and governments largely treated it that way too.

In Mexico, the expansion drumbeat kept going. The Pilares project, completed in 2022, added 35,000 tons of annual production capacity. It wasn’t on the scale of Buenavista or Toquepala, but that was the point: Southern Copper wasn’t just living off mega-projects. It was still converting its pipeline into real output, one project at a time.

And then there was Tía María—long the symbol of how difficult it had become to permit a new mine in Peru. After years of delays and protests, the project finally began moving forward again. The company projected that over a twenty-year life it could generate $17.5 billion in exports and $3.4 billion in tax revenues, which explained why the project never truly went away for either Southern Copper or the Peruvian government. The path forward depended on more than permits: community agreements, environmental monitoring commitments, and employment guarantees were all part of the effort to earn social acceptance, not just regulatory approval.

By 2024, the financials showed what this system could do when prices cooperated and costs stayed disciplined. Revenue rose to $11.43 billion, up 15.5% from the prior year. Net earnings climbed to $3.38 billion, up 39%. And operating cash cost fell to $0.86 per pound of copper, down 9.7% year over year—another marker of why Southern Copper is consistently viewed as a low-cost producer.

The broader narrative powering investor interest was simple: electrification is copper-heavy. Electric vehicles, renewable generation, and grid upgrades all pull more copper into the economy, while new mines often take a decade or more to permit and develop. At the same time, ore grades at many existing operations keep sliding. Put those together and the market starts to look like it could tighten—rewarding companies with large, long-lived reserves and the ability to expand without reinventing themselves.

Southern Copper also sat in a geopolitically unusual spot. It was American-listed, Mexican-controlled, and operated primarily in Peru—meaning its results could be influenced as much by politics and currency as by geology. And with nearshoring pushing more industrial activity toward North America, its Mexican operations had a potential tailwind that many global peers didn’t.

By the mid-2020s, the pitch for Southern Copper practically wrote itself: operational execution, massive reserve depth, and leverage to a structural demand story. Whether the copper thesis would unfold as cleanly as the models suggested was still an open question. But if the world really was entering a copper-constrained era, Southern Copper had positioned itself to be one of the prime beneficiaries.

IX. Capital Allocation & Shareholder Returns

Southern Copper’s capital allocation story lived in the same push-and-pull that defines every resource business: build for the next decade without forgetting the shareholders who have to live through the next downturn. The company tried to do both. It authorized a $3 billion share buyback and, by early 2025, had used $2.9 billion of that to repurchase 119.5 million shares—an unmistakable signal that management was willing to return capital when it believed the stock price didn’t reflect the underlying business. At the same time, it kept paying and growing its dividend, logging five consecutive years of increases and maintaining a yield around 3.3%.

That dividend posture was unusually bold for a miner. In a cyclical commodity business, the standard play is caution: keep the payout steady, avoid overpromising, and above all avoid the public humiliation of a cut when copper turns. Southern Copper went the other way. Dividend growth of roughly 35% in recent years suggested management believed its cash flows were more durable than the sector average—helped by low operating costs and the fact that much of its production came from long-lived, already-built complexes rather than constant, high-risk greenfield reinvention.

On the growth side, the company framed capital spending as disciplined and return-driven. Its $15 billion-plus capital investment program spanned big names in the pipeline—Tía María, Michiquillay, Los Chancas—along with a steady diet of brownfield expansions. The stated rule was simple: projects had to clear internal rate of return hurdles to earn funding, and capital was supposed to flow to the best opportunities, not just the most ambitious ones. In other words, the pitch was that this wasn’t empire-building; it was portfolio management.

But capital allocation at Southern Copper couldn’t be evaluated in a vacuum, because governance shaped everything around it. Related-party transactions stayed a recurring point of scrutiny. With Grupo México in control, Southern Copper routinely did business with other entities in the group—services, transportation, insurance, and other operational needs often ran through affiliates. The company disclosed these arrangements and used committees to evaluate fairness, but for minority shareholders the unease was structural: when the controller sits at the center of the web, it’s hard to ever be completely sure pricing and terms are truly arm’s-length.

That debate went beyond any single contract and into the core question of controlled-company life. When a controlling shareholder owns close to 90%, what real protection exists for the remaining slice? Southern Copper had independent directors and followed NYSE governance requirements, but ultimate authority still ran through Grupo México and, by extension, the Larrea family.

So for investors, the capital allocation takeaway wasn’t just “buybacks plus dividends plus growth.” It was: those policies might be attractive—but they’re executed inside a control structure that changes the risk profile. With Southern Copper, you weren’t only underwriting copper and costs. You were also underwriting who gets to decide what happens to the cash.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Southern Copper’s history is a master class in how vertical integration can actually work in commodities. When you control the chain from ore in the ground to refined metal, you don’t just “capture more margin.” You also gain options. If the mines are constrained but your smelters and refineries can run harder, you can buy third-party concentrate and keep the system utilized. And when markets get choppy—as they always do in copper—having that flexibility matters, because the pricing for intermediate products can swing fast and violently.

Operating in emerging markets also demands a toolkit that goes well beyond geology and engineering. Political risk isn’t something you hedge once and forget; it’s something you manage every day—through relationships with governments, unions, and communities that have to hold up even as administrations change. Currency risk is another constant: aligning revenue and cost bases where possible, and managing mismatches when you can’t. And then there’s community relations, often treated like a “soft” issue until it becomes the whole issue. In mining, social acceptance can decide whether a project gets built at all.

Southern Copper also shows the double-edged reality of conglomerate control. Grupo México brings real advantages: scale, purchasing power, technical depth, and the ability to finance big moves. In Mexico, having a sister railroad company like Ferromex creates obvious logistics synergies. But the same structure that delivers those benefits also creates unavoidable questions for minority investors. When the controller sits on both sides of related-party relationships, interests can diverge—and governance risk becomes part of the underwriting.

Cost leadership, meanwhile, is the bedrock advantage in copper mining, and Southern Copper has worked hard to keep it. Scale helps. Geography helps. Peru has historically offered stronger ore grades than many global peers, while both Peru and Mexico have tended to provide lower labor and energy costs than developed-market operations. None of those advantages are flashy, but over decades they compound into something that is: the ability to stay profitable through downcycles that wipe out higher-cost producers.

Then there’s the cycle—the defining rhythm of every commodity business. One of the hardest disciplines is expanding when conditions feel worst: when copper prices are low, capital is cheaper, and assets can be had at better terms, but confidence is scarce. Southern Copper repeatedly leaned into that playbook, approving and building major projects when the mood in the market would have pushed many competitors into retreat.

Labor relations are another reminder that mining is not a typical industrial business. A strike doesn’t slow you down; it can shut down a world-class asset. And in places like Peru, community opposition can stall a permitted project for years, or indefinitely. The only real “solution” is sustained trust-building—expensive, time-consuming work that rarely shows up in a quarterly earnings call, yet often determines whether the long-term plan survives contact with reality.

The company’s ESG story follows the broader arc of the industry: what started as an afterthought became an operating requirement. Early-era mining prioritized output, and environmental consequences were treated as collateral damage. Today, projects move through environmental impact studies, consultations, and ongoing monitoring that raise costs and complexity—but also reduce the political, legal, and reputational risk that can destroy value just as effectively as a bad ore body.

Finally, Southern Copper sits in the permanent tension at the heart of resource investing: capital discipline versus growth. The industry’s habit is to overbuild when prices are high, flood the market, and then spend the next downturn cleaning up the wreckage. Southern Copper’s stated approach—keep a deep pipeline, but advance only the projects that clear return hurdles—aims to thread that needle. It’s not a guarantee. But it is the right fight: growing without falling into the boomtime trap that has humbled so many miners before.

XI. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

Southern Copper’s biggest advantage is simple and hard to copy: it controls the world’s largest copper reserves—about 44 million tons of contained copper. In a sector where truly “new” tier-one discoveries are getting rarer, and where permitting can stretch for years or even decades, that reserve depth is the closest thing mining has to a moat. It doesn’t just support production. It supports relevance, cycle after cycle.

It also helps that Southern Copper tends to sit in the lowest quartile of global cash costs. That position comes from strong ore bodies and decades of operational tuning across mines, concentrators, smelters, and refineries. In down markets, that cost advantage is survival. In up markets, it becomes torque: as copper prices rise, much of that upside drops straight into earnings.

Then there’s the demand story the market can’t stop talking about: electrification. Electric vehicles use far more copper than conventional cars, and renewables and grid upgrades add still more pull on supply. The concern for the industry is that supply hasn’t been keeping pace—partly because new mines are hard to permit, hard to finance, and slow to build. If that mismatch persists, the setup favors long-life, low-cost producers with room to expand. Southern Copper fits that profile.

The integrated model matters too. Southern Copper isn’t just digging ore and hoping someone else can process it. With mining, smelting, and refining under one roof, it has more levers to pull—shifting throughput, optimizing the chain, and sometimes processing third-party material when it makes sense. That optionality can smooth earnings in a business that’s usually anything but smooth.

Financially, the company has tended to run with a strong balance sheet, manageable debt, and substantial cash generation. That matters in copper, because flexibility is the whole game: you want the ability to keep investing when the cycle turns down, not the obligation to retreat because the balance sheet won’t let you breathe.

And finally, there’s Grupo México. The control structure creates real governance questions, but it also brings practical advantages: scale, shared capabilities, and deep operating experience. In mining, “backing” isn’t just about money. It’s about having a sponsor willing to take long, politically complicated bets.

The Bear Case

For all of its strengths, Southern Copper can’t outrun the central risk of the business: it sells a commodity. Copper prices ultimately decide the company’s earnings power, and copper prices can fall hard and fast. A sustained decline—whether driven by Chinese demand weakness, global recession, or substitution—compresses margins regardless of how well operations are run.

Then there’s governance. Grupo México’s roughly 88.9% ownership means minority shareholders live inside a controlled-company reality. Related-party transactions are a recurring feature, and minorities have limited leverage if they disagree with decisions. The lingering shadow of the 2005 merger litigation is a reminder that these concerns are not theoretical—they’ve been tested in court and debated in public markets for years.

Country risk is also baked in. Peru and Mexico can both swing politically, and mining is an easy target when governments want revenue or symbolism. In Mexico, security risk adds another layer, with organized crime and regional violence affecting operating environments. Nationalization talk may be muted at times, but both countries have histories that keep the risk alive in the background.

Growth itself is not guaranteed, even with great geology. Community opposition can stall projects for years, as Tía María has shown. Permits are necessary but not sufficient; social license can become the binding constraint, and protests can disrupt construction or operations even after official approvals are in hand.

Labor risk remains part of the underwriting, particularly in Mexico. The Cananea strike proved that labor disputes can shut down major assets for long periods, with consequences that cascade into costs, output, and long-term plans.

Environmental liabilities are another long-tail risk. Decades of mining can surface later as remediation costs, claims, or stricter regulatory requirements. The industry has seen how expensive environmental failures can become, and the potential severity makes this category hard to dismiss.

And finally, there’s China. Even with electrification as a tailwind, China remains the single most important swing factor in the copper market. If Chinese consumption slows more than expected—through economic stagnation, policy shifts, or more effective substitution—the global market could loosen faster than the bullish narrative assumes.

Competitive Position Analysis

Southern Copper is typically compared with Freeport-McMoRan, BHP’s copper operations (with Escondida as the anchor), and Chile’s state-owned Codelco. Southern Copper stands out on reserve depth, even if it isn’t always the largest on current production. Freeport brings broader geographic diversification, including Indonesia. BHP’s copper sits inside a diversified portfolio that changes its risk and capital allocation profile. Codelco has enormous scale but operates with the constraints and priorities that come with being state-owned.

On classic industry structure, the picture is familiar for commodities: buyers have limited power because copper is globally priced, new entrants face enormous capital and permitting barriers, and rivalry is moderated by the fact that nobody truly sets price. Substitution is limited but not zero—aluminum can replace copper in some use cases, and technology can shift design choices over time.

Through a Hamilton Helmer lens, Southern Copper’s strengths cluster around the durable kind of advantage mining can actually have. Scale economies show up in processing and logistics. The integrated model is hard for pure-play miners to replicate quickly. And the biggest power of all is the cornered resource: large, long-lived ore bodies that are literally irreplaceable.

KPIs to Track

For ongoing monitoring of Southern Copper, three metrics deserve particular attention:

Cash cost per pound of copper is the clearest read on operational efficiency and resilience. It determines profitability across copper price scenarios and signals whether the company is holding its cost advantage. The 2024 figure of $0.86 per pound is a useful baseline, but the trend matters more than any single number.

Reserve replacement ratio tells you whether Southern Copper is replenishing what it mines. A ratio below one means depletion; consistently below one suggests the company is harvesting its endowment rather than extending it.

Production growth versus guidance is the simplest execution test. Management sets expectations annually; results versus guidance show whether expansions and operations are delivering on schedule—or slipping in the ways that often happen in mining.

XII. Recent News

Southern Copper’s fourth quarter 2025 results extended the same pattern investors had gotten used to: steady execution. Copper production and sales landed at or above guidance, and management used the quarter to underline two points—expansion projects were still moving, and the medium-term demand picture still looked attractive as electrification kept pulling copper into more parts of the economy.

Tía María, the project that has spent years as a proxy battle over “social license” in Peru, kept inching forward through construction. Management reiterated its expected start-up timeline, while also acknowledging the reality on the ground: community programs continued, and so did occasional localized protests—an ongoing reminder that in mining, a permit is a milestone, not a finish line.

In the market, copper itself did what copper always does: it swung. Prices moved through late 2025 and early 2026 as investors reacted to economic signals out of China and shifting expectations around Federal Reserve interest rates. Southern Copper’s advantage wasn’t that it could predict those moves. It was that, as a low-cost producer, it could absorb them with more margin cushion than most of the industry.

Meanwhile, the broader copper narrative only got louder. Analysts continued to warn about a structural supply gap later in the decade—demand rising faster than current production and already-committed projects could plausibly cover. If that view proves right, it reinforces the premium placed on exactly what Southern Copper has spent decades accumulating: reserve depth, integrated capacity, and a pipeline that can turn into real production.

And behind the scenes, the Grupo México ecosystem kept doing what conglomerates are designed to do. Other businesses—especially the railroad operations—continued to generate cash flow, adding flexibility at the group level and strengthening the broader platform Southern Copper sits within.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Materials: - Southern Copper Corporation Investor Relations: annual reports, quarterly results, SEC filings, and investor presentations - SEC filings via EDGAR: 10-K, 10-Q, and 8-K - Sustainability reports and environmental disclosures

Industry Research: - International Copper Study Group: global copper market statistics and forecasts - Wood Mackenzie: copper industry research - CRU Group: copper market analysis - S&P Global Market Intelligence: mining data and project databases

Regulatory and Legal: - Peru Ministry of Energy and Mines: mining regulations, permits, and project approvals - Mexico Ministry of Economy: mining concession information - NYSE corporate governance standards and listing requirements

Historical Resources: - "Mining Latin America" by Marian Radetzki: background on the region’s mining development - ASARCO corporate history materials - Grupo México corporate structure documentation

Market Data: - London Metal Exchange: historical copper prices - COMEX: copper futures data - Historical commodity price databases

Environmental and Community: - Environmental impact assessments for major projects - Community development program materials - Third-party sustainability assessments

Labor Relations: - History of Mexican mining unions - Peru labor law and collective bargaining frameworks in the mining sector - Documentation on major labor disputes, including Cananea

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music