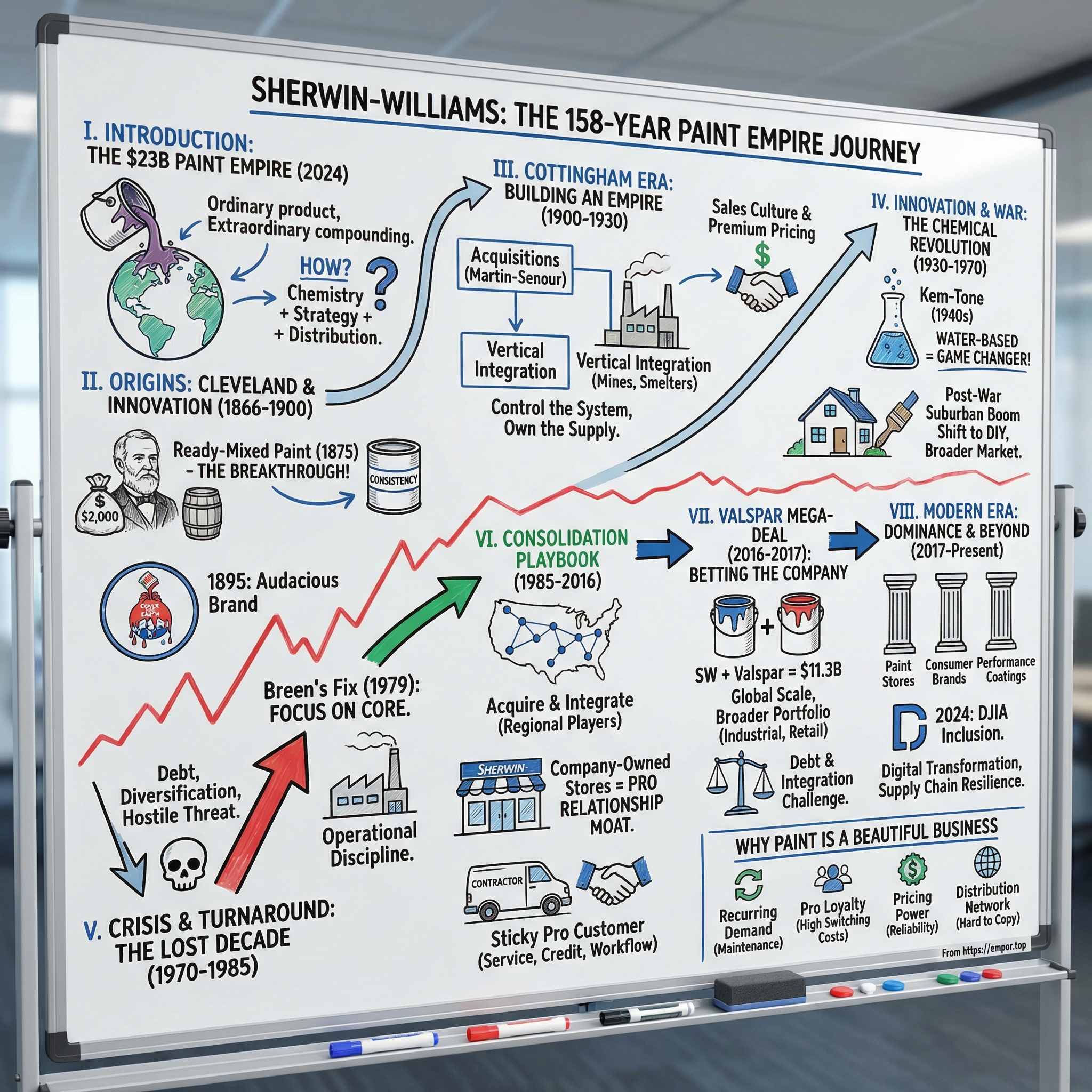

Sherwin-Williams: The 158-Year Paint Empire That Covered the Earth

I. Introduction & Cold Open

In March 2016, John Morikis stepped in front of analysts and dropped a number that made people blink: Sherwin-Williams would pay $11.3 billion to buy Valspar Corporation. It would be the biggest deal in paint industry history. The kind of price tag you expect in software or pharma, not in a business most people file under “hardware store aisle.”

Because paint is… paint, right? It goes on a wall, it dries, and a few years later someone covers it up with more paint. And yet Sherwin-Williams was willing to load up its balance sheet to buy another coatings company. Not to chase a trend, but to double down on the most ordinary product in the world.

That’s the hook. The answer says something important about the quiet corners of capitalism. While the spotlight stayed fixed on the latest tech darlings, Sherwin-Williams spent more than a century getting unbelievably good at one thing: covering surfaces with pigmented liquid, at scale, with reliability, and at a premium price. By 2024, the company based in Cleveland was the world’s largest coatings manufacturer by revenue, with record sales of $23.10 billion. Its market value hovered around $80 billion—bigger than plenty of louder, flashier names.

So here’s the real question, and it’s deceptively simple: How did a small Cleveland paint shop—started with $2,000 in 1866—turn into something that looks an awful lot like a global coatings monopoly?

The answer is part chemistry and part strategy. It’s breakthrough products that changed how paint was made and used. It’s acquisition campaigns that rolled up competitors. It’s a near-death spiral in the 1970s that almost took the whole company down. And it’s a distribution machine so effective that professional painters didn’t just buy Sherwin-Williams—they built their livelihoods around it.

This is a story about the unsexy power of compounding. About why, in commodity markets, distribution can matter more than the product. About doing boring things so well for so long that the results start to look inevitable. And, ultimately, about why some of the best businesses are the ones nobody wants to talk about at a cocktail party.

II. Origins: Cleveland Dreams & Chemical Innovation (1866-1900)

Henry Alden Sherwin arrived in Cleveland in 1860, twenty-three years old and thinking bigger than his wallet allowed. He’d learned the paint trade back in Vermont, standing behind a counter and watching the same scene play out: customers lugging home dry pigments and powders, then spending hours grinding and mixing them with linseed oil. It was messy, slow, and—worst of all—unpredictable. Two batches made from the same “recipe” could look and behave totally differently on the wall.

Sherwin didn’t just see an inconvenience. He saw a market begging for a better default.

After the Civil War, he scraped together $2,000 in life savings and partnered with another Clevelander to buy Truman Dunham & Company, a small oil and paint business. The partnership didn’t last, but Sherwin did. He threw himself deeper into the category—studying chemistry, experimenting with formulations, and treating paint less like a trade good and more like an engineering problem.

In 1870, the next piece clicked into place. Sherwin teamed up with Edward Porter Williams and Alanson T. Osborn to form Sherwin, Williams & Company. Williams brought capital and steady business judgment. Osborn brought salesmanship. Sherwin brought the obsession—and a belief that paint was about to be industrialized the way oil was being industrialized a few miles away, where John D. Rockefeller was turning Standard Oil into a machine.

Their first big move came in 1873, when they acquired Standard Oil’s cooperage, a barrel-making facility Rockefeller no longer needed. It wasn’t just a convenient building. It was their first real factory—close to raw materials, transportation, and the industrial workforce of Cleveland. Most importantly, it gave them room to scale and room to test.

Then came the leap that changed everything.

In 1875, Sherwin-Williams introduced the first commercially successful ready-mixed paint: paint in a can, ready to apply—no grinding, no guessing. That sounds obvious now, but it wasn’t obvious then. Ready-mixed paint had a brutal problem: it separated in the can. Pigment sank. Oil rose. Consistency died before the lid even came off. Plenty of people had tried. Nobody had solved it at industrial scale.

Sherwin did—through relentless experimentation with grinding processes and chemical additives that kept pigments suspended uniformly in oil. The result wasn’t just more convenient. It was reliable. Every can behaved the same way: same color, same coverage, same drying time. For professional painters, that wasn’t a nice-to-have. It meant they could finally promise outcomes to customers and actually deliver them.

Sherwin-Williams moved fast to turn that technical breakthrough into a business advantage. By 1884, the company incorporated, and Osborn exited the partnership, leaving Sherwin and Williams to push expansion harder. They also leaned into what would become a defining strength: distribution through dedicated dealers. Instead of tossing paint into general stores where it fought for attention next to nails and lamp oil, they cultivated paint-focused retailers who could explain this strange new idea—paint you didn’t have to mix—to buyers who didn’t yet trust it.

Out of the same era came one of the most recognizable trademarks in American business. In 1895, Sherwin-Williams introduced the “Cover the Earth” logo: a paint can pouring red over a globe. It was audacious, almost confrontational. A Cleveland paint maker wasn’t just selling cans—it was declaring intent. Not to win a neighborhood, or a state, but the whole map.

By 1900, Sherwin-Williams had grown from a $2,000 bet into a business generating $2.3 million in annual revenue, with multiple factories and a national distribution network. Henry Sherwin’s core insight—convenience and consistency could beat price in paint—had proven right. And the template was set: innovate in the lab, manufacture at scale, and win the market through relationships, not one-off transactions.

III. The Cottingham Era: Building an Empire (1900-1930)

When George A. Cottingham rose to lead Sherwin-Williams in the early 1900s, he didn’t inherit a struggling shop. He inherited a winner. But he wasn’t interested in simply selling more cans. Cottingham wanted control—of the ingredients, the manufacturing, the route to market, and the customer relationship. Where Henry Sherwin had been the tinkering inventor and Edward Williams the steady merchant, Cottingham was the empire-builder who saw paint as a system, not a product.

His acquisition campaign kicked into high gear in 1917 with the purchase of Martin-Senour, a major Chicago-based rival. This wasn’t a bargain-bin deal. Martin-Senour had real brand strength and its own dealer relationships. Cottingham paid up anyway because he understood what the paint business was becoming: as the market matured, share and distribution mattered more than almost anything else. Buy the competitor, keep the dealers, and you don’t just gain sales—you deny them to everyone else.

Then came the financial unlock. In 1920, Sherwin-Williams went public, raising $15 million—serious money for the time. And Cottingham didn’t spend it the way most manufacturers would. Instead of just adding more capacity, he pushed backward into the supply chain. Sherwin-Williams bought into mines producing key inputs like zinc oxide and lead (common paint ingredients in that era), along with smelters to process those materials and linseed oil plants to produce the binding agent that made oil-based paints work.

The logic was simple and ruthless. Commodities were volatile. Supply could tighten without warning. If you could secure your own raw materials, you could keep production running when competitors had to slow down. If you owned more of the chain, you kept more of the profit that would otherwise go to suppliers. And, over time, you made the whole game harder for anyone new to enter. A startup paint company could try to compete on price, but it couldn’t compete against a rival that increasingly controlled the inputs.

By the end of World War I, Sherwin-Williams had become the world’s largest paint manufacturer. Revenue surged from $2.3 million in 1900 to $34.2 million in 1919—growth driven not just by a bigger market, but by a company that was methodically taking territory: buying rivals, folding in their operations, and pulling their dealer networks under the Sherwin-Williams flag.

Inside the company, Cottingham built something just as important as factories and mines: a sales culture. He taught his teams to treat paint like a service business. Salespeople were expected to understand how buildings aged, how maintenance budgets got set, and how remodel cycles worked. And they were trained to obsess over the real repeat customer. A homeowner might repaint every several years. A painting contractor bought paint constantly. If you won the contractor, you won a stream, not a transaction.

At the same time, Sherwin-Williams leaned hard into national advertising to cement a premium image. While many competitors sold paint like a commodity, Sherwin-Williams sold reliability—quality, consistency, and the comfort of expertise behind the counter. The company charged more, and customers accepted it because the brand stood for outcomes they could count on. That pricing power—earned, not demanded—became one of the company’s most durable advantages.

The beauty of Cottingham’s playbook was how tightly it all connected. Control the inputs, protect supply, and keep costs in line. Use the resulting profits to support dealers and advertise the brand. Let the brand justify premium pricing. Use that premium to fund more acquisitions and more integration. Each move made the next one easier.

And by the 1920s, the flywheel was spinning.

IV. Innovation & War: The Chemical Revolution (1930-1970)

If Cottingham’s era was about owning the system, the next chapter was about changing the chemistry.

In the 1940s, Sherwin-Williams landed what may have been the most important product breakthrough in its history—one that would be recognized more than half a century later as a National Historic Chemical Landmark. In a Cleveland lab, the company’s chemists developed Kem-Tone, the first commercially successful water-based paint. And once you can make paint work in water, you don’t just improve paint. You expand who can use it, where, and how often.

For centuries, oil-based paint had been the default for good reasons: it stuck well, dried into a tough film, and held up against moisture. But it came with a list of problems everyone simply tolerated. It smelled awful. It was flammable. It took forever to dry. Cleanup meant solvents, not soap and water. If you were a homeowner painting a bedroom, you aired the place out, lived with the fumes, and hoped you didn’t ruin everything you owned. If you were a professional painter, you lived in those fumes constantly.

Kem-Tone flipped the equation by suspending pigments in water instead of oil. It applied smoothly, dried in hours rather than days, cleaned up easily, and didn’t announce itself to the entire house with a heavy odor. Painting stopped being an ordeal. It became a task. The kind a normal person could take on without special tools, special chemicals, or a tolerance for discomfort.

And the timing could not have been better.

World War II sent demand for coatings through the roof. Military vehicles, ships, aircraft, and facilities all needed protective finishes. At the same time, the workforce thinned as men left for service. Sherwin-Williams factories ran continuously, increasingly staffed by women stepping into industrial jobs they’d never held before. The company’s scale and technical capability made it a serious wartime supplier—and the war years, brutal as they were, forced industry to move faster, produce more, and refine processes under pressure.

Then the war ended, and the market didn’t cool off. It shifted.

The post-war consumer boom created a wave of new homes in expanding suburbs—houses that needed paint right away, and would need it again as families grew, tastes changed, and maintenance became part of middle-class life. Kem-Tone didn’t just win customers; it pulled new ones into the category. Paint was no longer something you hired out by default. It became a weekend project, which meant more volume, more frequency, and a much larger market than “professional painters only.”

In 1996, the American Chemical Society named Kem-Tone a National Historic Chemical Landmark, a rare nod that underlined what Sherwin-Williams had actually done: it introduced water-based technology that would become the standard. Today, in most consumer settings, latex paints outsell oil-based products by a wide margin—an industry reality that traces back to this period.

Sherwin-Williams was also getting bigger in a different way. International expansion picked up as the company followed American business abroad. Its brand footprint grew not just through Sherwin-Williams stores and products, but through a widening portfolio of acquired brands aimed at different customers and geographies.

And the product mix kept moving up the value chain. The company pushed deeper into specialty coatings—industrial applications, automotive finishes, marine paints, and protective coatings for infrastructure. Compared to plain architectural paint, these were more technical, more performance-driven, and often more profitable. They also anchored relationships with customers who cared less about the cheapest gallon and more about what happened when a coating failed.

By 1970, Sherwin-Williams looked less like a single paint maker and more like a coatings conglomerate: broader products, wider geography, more end markets. But the underlying engine was the same one that had powered the company since the beginning—make something meaningfully better, manufacture it at scale, and distribute it through relationships that kept customers coming back and made switching feel risky.

V. Crisis & Turnaround: The Lost Decade (1970-1985)

By the mid-1970s, Sherwin-Williams had a problem it wasn’t used to having: it was losing its edge.

A century of momentum had hardened into bureaucracy. Management chased diversification into businesses it didn’t truly understand, and the core paint operations didn’t get the attention they needed. Even the old strengths started to backfire. The vertical integration that had looked brilliant in the 1920s—mines, raw materials processing, all the way up the chain—was now expensive, complex, and increasingly out of step with what the business actually needed. What used to be a moat was turning into a weight around the ankle.

Then the numbers made it undeniable.

In fiscal 1977, Sherwin-Williams posted an $8.2 million loss on roughly $1 billion in revenue. That alone was jarring for a company that had spent generations treating profitability as a given. But the deeper issue was the balance sheet. Debt had jumped from essentially nothing to $242 million, as the company borrowed to fund its side quests and to plug holes from weak operations. The “Cover the Earth” company wasn’t just stumbling—it was bleeding cash while adding leverage.

And in corporate America, that combination sends up a flare.

Gulf + Western Industries—run by the famously aggressive Charles Bluhdorn—built a 13.47% stake in Sherwin-Williams and signaled it wanted control. Gulf + Western had a reputation for buying underperformers, stripping pieces, and harvesting value. For Sherwin-Williams, a hostile takeover likely wouldn’t mean a gentle new owner. It would mean being carved up: assets sold, operations cut, and the independent Cleveland institution reduced to parts.

The board understood the company didn’t need a new plan. It needed a new operating system. In 1979, it brought in John G. Breen, an executive known for operational discipline and turnarounds. Breen walked into a company in full-on crisis: employees demoralized, creditors wary, raiders circling, and a business that had somehow let itself become less competitive in the one category it was supposed to own.

Breen’s fix was blunt, almost austere: get back to paint, and get rid of the rest.

He sold off the mining operations that had made sense decades earlier. He shut down or divested peripheral businesses. He cut headquarters staff dramatically. And he forced Sherwin-Williams to face an uncomfortable truth: it had become spread out and mediocre, when the only way to survive was to be excellent at the core again.

Keeping the company independent meant beating Gulf + Western on two fronts at once. Breen tightened operations and worked to improve performance so the stock wouldn’t look like an easy bargain. He reshaped the financial picture, and he played the shareholder and political game, too—building support among investors who didn’t want the takeover and drawing backing from Ohio’s leadership that wanted the hometown company to stay whole.

Eventually, Gulf + Western exited, selling its stake without taking control. Sherwin-Williams survived.

But it didn’t walk away unchanged. The episode burned a set of lessons into the company’s DNA: diversification without discipline destroys value; debt creates vulnerability; and in a mature, competitive market, “good enough” is how you die—slowly, then all at once. Under Breen, Sherwin-Williams came out of the lost decade leaner, sharper, and newly serious about focus and operational excellence.

VI. The Consolidation Playbook (1985-2016)

The turnaround saved Sherwin-Williams. Now came the part that would define the modern company: turning survival into dominance.

Starting in the 1980s—and then really accelerating through the 1990s and 2000s—Sherwin-Williams committed to a strategy that sounds straightforward and is brutally hard to pull off: buy competitors, integrate them fast, and keep expanding a company-owned store network until Sherwin-Williams wasn’t just the biggest name in paint. It was the default.

The acquisition cadence became almost mechanical. In a twenty-one-month stretch in 1994 and 1995, Sherwin-Williams completed sixteen acquisitions. These weren’t blockbuster, headline-grabbing deals. They were regional paint makers, specialty coatings businesses, and distribution footprints that expanded the map one chunk at a time. Each one did three things: added customers, removed a competitor, and gave Sherwin-Williams more scale to pour back into the machine.

But acquisitions were only half the play. The other half was distribution—owned and operated, end to end. By 2002, Sherwin-Williams ran more than 2,500 company-owned stores across North America. Not franchises. Not independent dealers. Sherwin-Williams locations staffed by Sherwin-Williams employees, trained on Sherwin-Williams systems, pushing Sherwin-Williams products.

Those stores weren’t just places to buy paint. They were relationship centers. They were technical support desks. They were a contractor’s problem-solving hotline and supply depot, five minutes from the job site.

This was a deliberate contrast to the rest of the industry. Benjamin Moore leaned on independent retailers. Behr won the big-box aisle through Home Depot. Sherwin-Williams largely avoided that channel and bet instead on the customer that mattered most: professional contractors.

Because pros don’t shop the way DIY homeowners do. A contractor isn’t wandering an aisle comparing price tags. Their business depends on repeatability: the paint has to perform the same way every time, across crews and across jobs. When something goes wrong, they need someone who knows their account, understands their workflow, and can help fix the issue now—not after a call center ticket clears.

Sherwin-Williams built its stores around that reality. Contractors got managers who knew them by name, credit that matched the rhythm of their cash flow, and loyalty rewards that recognized volume. Over time, the switching costs became less about the chemistry in the can and more about the system wrapped around it. Changing paint brands meant changing habits, relationships, and operational muscle memory.

Technology made the whole thing stickier. Sherwin-Williams rolled out computerized color matching that could replicate a shade from a sample a customer brought in. Stores could also keep records of prior jobs so contractors could come back years later and match exactly. Today that feels standard. At the time, it was a real edge—and another reason to keep buying from the same counter.

And even as the company consolidated a mature market, it kept pushing innovation. In 2016, Sherwin-Williams launched a paint with EPA-registered microbicidal properties, designed to kill bacteria on dried paint surfaces. That opened doors with customers who cared about performance beyond color and sheen—healthcare facilities, schools, and food processing plants willing to pay for coatings that supported hygiene and safety.

By the mid-2010s, the results were hard to miss. Sherwin-Williams had become the dominant force in North American architectural coatings, with a store network that had grown to more than four thousand locations. In many regions, it controlled more than forty percent of the professional market. Competitors had been acquired, pushed to the margins, or boxed into narrower niches.

Sherwin-Williams had won the ground game. The only question left was whether it could win the air war, too—and that’s where Valspar entered the picture.

VII. The Valspar Mega-Deal: Betting the Company (2016-2017)

John Morikis was a Sherwin-Williams lifer—someone who’d come up through sales, built his career around contractors, and learned the business at the counter and in the field. When he took over as CEO in 2016, he didn’t inherit a company in trouble. He inherited a company that had, in many ways, already won.

And that was the problem.

In North America, the consolidation playbook had largely run its course. Sherwin-Williams already had the stores, the relationships, and the share. If it wanted the next leg of growth, it had two real options: push harder internationally, or make one transformational acquisition that changed the company’s scope overnight. Morikis chose the second path.

The target was Valspar.

Based in Minneapolis, Valspar did about $4.4 billion in annual revenue and fit Sherwin-Williams like a missing puzzle piece. Sherwin-Williams was the king of professional architectural paint. Valspar was strong where Sherwin-Williams was less dominant—industrial coatings, packaging coatings, and wood finishes. Sherwin-Williams skewed North America. Valspar had meaningful international operations. And while Sherwin-Williams largely avoided the big-box channel, Valspar supplied branded paint through Lowe’s, giving Sherwin-Williams a footprint it didn’t really have.

In March 2016, Sherwin-Williams announced an all-cash offer: $113 per share for Valspar, valuing the equity at about $9.3 billion. With assumed debt, the deal clocked in at $11.3 billion—instantly the largest transaction in paint industry history. This wasn’t “add a region” M&A. This was Sherwin-Williams deciding that in a global coatings market, scale and breadth would be the advantage that mattered most—and paying accordingly.

Then came the part nobody gets to skip on deals like this: regulators.

The Federal Trade Commission required significant divestitures before it would sign off. Valspar’s North American industrial wood coatings business had to be sold to address antitrust concerns, and the divestitures reduced the ultimate purchase price to just over $9 billion. The process stretched on, delaying the close until June 2017 and forcing both companies to operate in a long, uncomfortable limbo—employees wondering what would change, customers wondering who their supplier would be, and shareholders watching the calendar.

To finance it, Sherwin-Williams made its own bet. The company raised $6 billion in bonds at a blended interest rate of roughly 3.2%. It was cheap money—an endorsement from the market that Sherwin-Williams’ cash flows were real and durable. But it also flipped the company’s financial profile almost overnight: from conservative to heavily levered, with debt levels that would have sounded like a horror story to the version of Sherwin-Williams that nearly broke in the 1970s.

Management promised $320 million in annual cost synergies, largely from combining purchasing, removing duplication, and consolidating overhead. Publicly, that number served as the clean, accountable headline. Internally, the pressure was sharper: when you pay a record price in cash and load up on debt, integration isn’t a “nice to do.” It’s the whole ballgame.

And integration was where the real work began.

Valspar had been operating independently for more than two centuries, with its own habits, relationships, and sense of identity. Sherwin-Williams, meanwhile, had a very specific playbook: integrate fast, standardize systems, and run the acquired business the Sherwin-Williams way. Some longtime Valspar leaders left. Others stayed and adapted. Either way, the direction was unmistakable—one company, one operating model.

When the dust settled, the coatings industry had a new heavyweight. Sherwin-Williams now had the global scale to compete in more markets, the product breadth to serve everything from house paint to packaging, and the resources to keep consolidating a still-fragmented category.

The only remaining question was the one that always hangs over mega-deals: would it earn its price? Sherwin-Williams had made the bet. Now it had to make it true.

VIII. Modern Era: Digital Transformation & Market Dominance (2017-Present)

The years after the Valspar deal closed were the stress test. Sherwin-Williams had to prove it could absorb a massive acquisition without losing momentum, all while rivals looked for openings. At the same time, raw material costs swung hard—especially titanium dioxide, the white pigment that gives paint its coverage—and just as the integration machine was spinning up, the world changed.

When COVID-19 hit in March 2020, the setup looked ugly. Jobsites shut down. Commercial projects paused. Consumers pulled back on plenty of discretionary spending. Paint, on paper, should’ve been on the chopping block.

Instead, paint became therapy.

Stuck at home, and buoyed by stimulus checks, Americans started fixing, refreshing, and repainting their spaces. DIY demand surged. Professional sales dipped at first, then came back as the economy reopened. For Sherwin-Williams, the pandemic didn’t break the business. It showed what was really underneath it: coatings demand can shift between channels, but it doesn’t disappear.

Of course, the DIY spike didn’t last. A lot of painting got pulled forward, and the comedown followed. By 2022 and 2023, consumer demand had cooled back toward normal levels while professional and industrial volume regained its footing. The ride was volatile, but the takeaway was steady: people may not repaint at lockdown intensity forever, but buildings still age, tastes still change, and every surface still needs protection.

Operationally, Sherwin-Williams settled into the three-part structure that still defines it today: Paint Stores Group, Consumer Brands Group, and Performance Coatings Group. Paint Stores remained the heart of the company—thousands of company-owned locations built around professional contractors and the repeat rhythms of maintenance and repainting. Consumer Brands housed Valspar’s retail presence, including products sold through Lowe’s and other outlets. Performance Coatings covered the industrial engine room: packaging, coil, automotive, and general industrial finishes where performance matters as much as color.

In November 2024, Sherwin-Williams got a kind of corporate knighthood when it joined the Dow Jones Industrial Average, replacing Dow Inc. That move said something subtle but important. Sherwin-Williams wasn’t being treated like a niche specialty-chemicals player anymore. It was being treated like a core American industrial—an all-weather operator in the same conversation as the stalwarts.

Behind the scenes, the company kept building the advantages that were hardest to copy. It committed to a new Cleveland headquarters, reinforcing that the business was still anchored in the city where it began in 1866. It invested in its supply chain, shaped by the chaos of 2021 and 2022, when shortages and logistics snarls punished anyone without scale or strong supplier relationships. And it leaned into sustainability initiatives as customers and regulators raised expectations around environmental impact.

That supply chain period also clarified a modern truth about Sherwin-Williams: in coatings, procurement is strategy. The company’s scale gave it direct relationships with chemical suppliers and better visibility into tightening markets. When key inputs like titanium dioxide spiked, Sherwin-Williams was often better positioned than smaller competitors to keep product flowing and push price increases through without getting crushed.

By the time it entered 2025, Sherwin-Williams stood as the world’s largest coatings manufacturer by revenue, operating in more than 120 countries with products that touch nearly every kind of surface you can name. The Cleveland paint shop story had become something else entirely: a global industrial champion built on chemistry, distribution, and the quiet power of doing the basics better than anyone else.

IX. The Business Model: Why Paint is a Beautiful Business

Wall Street has a habit of yawning at paint. There’s no network effect, no platform story, no viral growth loop. Just pigments, binders, and buckets. And yet Sherwin-Williams has compounded shareholder returns over long stretches in a way that has put plenty of flashier industries to shame. To understand how, you have to see coatings for what they really are: a deceptively elegant business wrapped around a very physical, very recurring need.

Start with the repainting cycle. Paint is not a one-time purchase; it’s a maintenance requirement with a long fuse. A home painted today will need attention again in seven to ten years. Many commercial buildings repaint more often. Industrial facilities are in a constant battle against corrosion and wear. The result is recurring demand that behaves a lot like a subscription—except nobody feels like they’ve “subscribed” to anything. Customers don’t experience a monthly bill. They experience a project every few years. Sherwin-Williams gets the economic benefit of repeat behavior without triggering the customer resentment that sometimes comes with explicit recurring charges.

Then there’s the real moat: the professional contractor relationship.

A contractor who’s bought Sherwin-Williams for years isn’t just buying paint. They’ve trained crews on how it spreads, how it cuts in, how it dries, and how it touches up. They’ve built personal relationships with store managers who know their jobs, their preferences, and their timelines. They’ve established credit terms that match the cadence of getting paid. They’ve accumulated loyalty rewards. Switching to another brand isn’t impossible, but it’s disruptive in ways that matter when your profit comes from labor efficiency and your reputation comes from consistent results. The switching costs don’t live in the can. They live in the workflow around it.

That’s what makes brand power in paint so unintuitive and so durable. On paper, paint looks like a commodity. In practice, trust is everything. Most homeowners can’t explain why one paint might be better than another, but many still believe Sherwin-Williams means quality. That belief was built over generations of consistent product performance and reinforced through relentless marketing. It supports premium pricing, and it holds even when cheaper options sit a few feet away under brighter big-box lighting.

Distribution is where all of this turns from “nice advantages” into something closer to a fortress. Sherwin-Williams operates more than four thousand company-owned stores across North America. That isn’t just reach; it’s proximity. A contractor doesn’t want to drive across town mid-job because they ran short. They want a Sherwin store nearby with the right product, the right color match, and a counter staff that can fix problems fast. Competitors can’t snap their fingers and replicate that footprint. Opening stores takes real estate, inventory, trained people, and, most importantly, local relationships. Those are slow to build and hard to steal.

Layer on pricing power, and you start to see why the model compounds. Raw material costs swing. Sherwin-Williams has shown, repeatedly, that it can push price increases through with minimal volume fallout because its customers are buying reliability and service as much as they’re buying pigment. And when competitors try to discount for share, Sherwin-Williams often resists the race to the bottom, leaning on relationships and convenience to keep business without sacrificing profitability. In an industry fed by commodity inputs, that margin discipline is rare—and incredibly valuable.

Finally, the cash has been handled with the same steady hand. Sherwin-Williams has raised its dividend for more than forty consecutive years, a signal of both confidence and consistency. It has also used share repurchases over time to shrink the share count and concentrate the upside among remaining owners. And while the company has been aggressive in acquisitions, it has also shown a willingness to walk away when the math didn’t work.

Put it all together and the “boring paint company” starts to look different. It’s recurring demand, sticky professional customers, premium brand trust, a hard-to-copy distribution network, and the ability to turn cash flow into long-term compounding. Paint may not be exciting. But as a business, it’s quietly beautiful.

X. Competitive Analysis & Market Position

In North American architectural coatings, Sherwin-Williams doesn’t operate in a universe of dozens of equals. It has a small set of real rivals—PPG Industries, Benjamin Moore, and Behr—and each one is strong in a specific lane. The difference is that Sherwin-Williams is strong in the lane that matters most: pros who buy paint for a living.

PPG is the most obvious comparison because it’s also a global coatings giant, with meaningful businesses in automotive, aerospace, and industrial markets. But in the day-to-day battle for North American architectural share—especially among professional painters—PPG is fighting without Sherwin-Williams’ best weapon: a dense network of company-owned stores. PPG largely reaches customers through independent dealers and hardware stores, which can work, but it’s not the same as controlling the counter, the account relationship, the credit terms, and the service experience. In a head-to-head for pro loyalty, PPG tends to play defense.

Benjamin Moore is a different kind of competitor. It lives at the premium end of the market, with a brand that signals taste and quality. It has a loyal following among interior designers, upscale contractors, and homeowners who want the “good stuff” and like being able to say they used it. But that prestige comes with a structural constraint: Benjamin Moore sells through independent dealers. That limits how much control the company has over the in-store experience and creates natural friction between what the brand might want and what the channel partners need. Benjamin Moore’s ownership—Berkshire Hathaway—brings patient capital, but not necessarily a distribution overhaul or a radically different operating playbook.

Behr sits on the opposite end of the chessboard. It’s a value-oriented brand built for the DIY customer and sold exclusively through Home Depot. That relationship gives Behr enormous reach with homeowners doing weekend projects, and it has made Behr a defining name in the big-box aisle. But it also shapes the brand’s reputation: Behr is often associated with saving money, not delivering the highest performance. That can be perfectly rational for DIY buyers—and a perfectly good business for Behr’s owner, Masco Corporation—but it’s why professional painters rarely specify it.

This is the backdrop for one of Sherwin-Williams’ most debated choices: staying relatively light in big-box retail. Critics say the company is leaving growth on the table by ceding the DIY channel to Behr. Supporters argue Sherwin-Williams is avoiding a channel defined by promotions, price competition, and fickle customer behavior—then reinvesting that focus into the higher-margin, stickier pro market. If you look at Sherwin-Williams’ long-term financial results, the “focus on pros” camp has the stronger case.

Globally, the picture gets tougher. Outside North America, coatings markets can be more fragmented, more local, and more relationship-driven. Valspar helped push Sherwin-Williams deeper into international markets, but it still faces competitors that are deeply entrenched in their home territories—companies like AkzoNobel and Asian Paints, which have their own versions of distribution moats and local loyalty that won’t be easy to pry loose.

One underappreciated battlefield is technology. Sherwin-Williams holds thousands of patents across formulations, application methods, and color systems. Its R&D spending may look modest as a percentage of revenue, but the output is exactly the kind of incremental advantage that compounds in a mature industry: better coverage, faster drying, longer-lasting color, improved resistance to wear and fading. None of those improvements wins the market overnight. But stacked together, year after year, they help explain why Sherwin-Williams keeps taking share—and why its customers keep coming back.

XI. Bear & Bull Cases: The Investment Thesis

The Bull Case

Sherwin-Williams sits in a rare position: it’s not just a paint brand, it’s the default operating system for professional painters across North America. The company-owned store network is the moat. Competitors can make good coatings, but replicating thousands of staffed locations—close to jobsites, stocked with inventory, and run on a single playbook—would take years and billions, and it would still be uncertain. That footprint turns distribution into a long-term advantage, not a line item.

Then there’s the customer relationship. Pros don’t behave like casual shoppers. They build routines. They train crews. They rely on store managers who know their account and can solve problems fast. That loyalty creates recurring revenue without contracts. It’s not a subscription, but it acts like one.

Pricing power flows naturally from that setup. When a contractor’s biggest cost is labor, a slightly higher paint price matters far less than reliability, consistency, and not having to redo work. Sherwin-Williams has spent generations earning the right to charge more, and the brand stands for more than what’s in the can. It stands for outcomes.

On profitability, the story still has room to run. The Valspar deal brought meaningful synergies—ultimately coming in ahead of initial targets—and Sherwin-Williams has kept finding ways to tighten operations in a global, complex footprint. Over time, the mix also improves: more specialty, industrial, protective, and performance coatings means a greater share of revenue comes from products where specs and performance matter more than price tags.

And the long-term demand tailwind is simple: America is old. The housing stock built in the 1970s and 1980s doesn’t stop needing maintenance just because new construction slows. Even in a flat housing environment, repainting and renovation keep coming—quietly, predictably, year after year.

Finally, consolidation isn’t over. Outside North America, coatings markets are still more fragmented, with plenty of regional players. Sherwin-Williams has spent decades building an integration muscle that few industrial companies can match. If management chooses to keep rolling up the market internationally, it has a playbook and a track record.

The Bear Case

The biggest risk is that paint is tied to housing and construction cycles, and those cycles can be brutal. When housing activity slows—rates rise, recession hits, projects get deferred—paint demand usually follows. Sherwin-Williams held up well during COVID’s whiplash, but a long, grinding housing downturn would still pressure volume and could squeeze margins.

Input costs are another persistent threat. Titanium dioxide, resins, and solvents are meaningful components of paint economics, and their prices can swing with global chemical markets and supply disruptions. Sherwin-Williams is generally better than peers at passing costs through, but “better than peers” doesn’t mean immune. If inflation sticks or supply chains tighten again, profitability can get pinched.

There’s also the question of what Sherwin-Williams is choosing not to be. The DIY market has continued migrating toward big-box retailers and value-oriented brands. Sherwin-Williams has intentionally prioritized pros over the promotional, price-driven dynamics of big-box. That focus has worked, but it also means leaving a large pool of demand to others—and limiting optionality if consumer behavior shifts further.

International expansion is its own kind of hard. Different regulations, different customer expectations, and entrenched local competitors raise the difficulty level. The Valspar integration showed that cross-border complexity is real, and scaling globally requires capabilities beyond domestic roll-ups.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low. Scale matters in coatings, brand trust takes decades to build, and distribution is expensive and slow to replicate. Architectural paint hasn’t seen meaningful new entrants in a long time for a reason.

Supplier Power: Moderate. Suppliers are large chemical companies with real leverage, but Sherwin-Williams’ scale gives it negotiating power and better access in tight markets. Some vertical integration also helps reduce exposure.

Buyer Power: Low to Moderate. Pro painters face high switching costs and limited reasons to gamble on a new system. DIY consumers have more alternatives, though brand still matters. Large commercial and industrial buyers can negotiate, but they can’t negotiate away performance requirements.

Threat of Substitutes: Low. Buildings and infrastructure still need protective and decorative coatings. Formulations evolve, but the need doesn’t go away.

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate. There are strong competitors, but they tend to win in channels or segments Sherwin-Williams doesn’t prioritize. The industry generally avoids destructive price wars because everyone knows the outcome.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Manufacturing scale and purchasing leverage lower unit costs and improve resilience when inputs get volatile.

Network Effects: Limited direct network effects, but there are indirect ones: once architects, designers, and contractors standardize on certain colors and specs, the ecosystem starts to reinforce itself.

Counter-Positioning: The company-owned store model is hard for rivals to copy without disrupting their existing dealer or big-box relationships.

Switching Costs: Contractors don’t just switch paint—they switch workflows: crew habits, store relationships, credit terms, and rewards. The costs are behavioral, not contractual, and that’s exactly why they endure.

Branding: Sherwin-Williams sells trust—quality, consistency, and support—more than it sells pigment and binder.

Cornered Resource: Store locations in prime trade areas are a quiet asset. Many were secured decades ago, and equivalent sites aren’t always available anymore.

Process Power: Sherwin-Williams’ ability to integrate acquisitions—systems, procurement, operations—has become an accumulated advantage.

Key Performance Indicators

If you’re watching Sherwin-Williams quarter to quarter, two metrics do most of the work:

Same-Store Sales Growth: With a company-owned store base, comparable-store sales show whether demand is strengthening, weakening, or whether the company is taking share—independent of simply opening more locations.

Gross Margin Trend: Gross margin is the scoreboard for the central fight in coatings: pricing power versus raw material costs. When margins expand, it usually means price and mix are winning. When they compress, input costs or competitive pressure are biting.

XII. Lessons & Playbook Takeaways

Sherwin-Williams’ 158-year run isn’t just a paint story. It’s a case study in how you build an enduring business in a category most people assume should be a race to the bottom.

The Power of Vertical Integration in Commodities

When you sell something others can make, the edge often isn’t the product. It’s everything around the product. Sherwin-Williams’ early move into mines, smelters, and linseed oil processing didn’t magically make paint prettier on the wall. It made the company harder to disrupt. It stabilized supply, reduced dependence on volatile inputs, and captured more of the profit pool that would otherwise sit with suppliers.

Distribution as Competitive Advantage

If Sherwin-Williams has a superpower, it’s distribution. Formulas can be copied. Brands can be challenged. But a dense network of thousands of company-owned stores—staffed by people trained to serve pros, stocked to support jobsites, and run on a single operating playbook—doesn’t appear overnight. In paint, being close, consistent, and dependable often beats being marginally “better” in the can.

Premium Pricing in Commodity Markets

The default assumption about commodities is that price wins. Sherwin-Williams shows the loophole: customers will pay up for outcomes. The brand stands for consistency, the stores deliver service, and the relationships make the whole experience frictionless. That combination supports premium pricing even when cheaper alternatives are sitting nearby. Convenience and trust can be a pricing model.

Acquisition Integration Excellence

Plenty of companies can buy. Far fewer can merge operations without losing what they paid for. Sherwin-Williams has spent decades building an integration muscle: acquire, standardize systems, consolidate purchasing, remove duplication, and keep the customer experience steady. It’s not glamorous, but it turns acquisitions from a one-time growth spike into a repeatable engine.

Surviving and Thriving Through Cycles

Over a century and a half, you don’t get one test—you get many. The 1970s nearly broke the company. COVID reshuffled demand overnight. The common thread is resilience: you survive by staying financially disciplined enough to absorb shocks, and operationally flexible enough to redirect effort when the market shifts. The companies that last aren’t the ones that never get hit. They’re the ones built to take hits.

Building Switching Costs in B2B Relationships

Sherwin-Williams doesn’t lock contractors in with contracts. It locks them in with a better way to work. Over time, switching becomes painful: crews are trained on specific products, store teams know the account, credit terms match the business, loyalty rewards stack up, and problems get solved fast. The strongest switching costs don’t feel like handcuffs. They feel like service.

The Compounding Power of Incremental Improvements

Sherwin-Williams didn’t win because of one heroic moment. It won by stacking small advantages for 158 years—slightly better chemistry, slightly better manufacturing, slightly better service, slightly better logistics, slightly better relationships. None of that makes headlines. But in a mature industry, that’s how dominance is built: not through a single breakthrough, but through relentless accumulation.

XIII. "What Would We Do?" Scenario

Sherwin-Williams headed into 2026 from a position of real strength. It had scale, brand, distribution, and an integration machine that had already digested Valspar. But “dominant” doesn’t mean “done.” The question now wasn’t how to defend the castle. It was where to put the next dollar and the next unit of attention.

The cleanest growth vector was international expansion. North America was mature; many overseas coatings markets weren’t. India, Southeast Asia, and Latin America were growing faster and still full of strong regional players. Sherwin-Williams could lean into what it has always done best: buy footholds, bring them onto its operating system, and steadily widen the map. The tradeoff is obvious. Cross-border integration is harder, local competition can be deeply entrenched, and mistakes get expensive fast. But if the company wanted the next leg of durable growth, this is where the runway looked longest.

Then there’s digital. Sherwin-Williams has invested in tools like color visualization and specification databases, but there’s still room to be bolder—especially with professionals. Better ordering workflows, tighter job tracking, easier reorders, and smarter account tools could deepen contractor loyalty even further. And if the company could make the experience frictionless enough, it might also pick up incremental DIY share that currently defaults to big-box retailers. The risk is channel conflict. The upside is meeting customers where they increasingly live: on their phones, in their project apps, and in online ordering habits that don’t care about industry tradition.

A third path is adjacent expansion—staying close to the coating buyer, but expanding the basket. Many industrial customers who buy coatings also buy sealants, adhesives, and other specialty chemicals. Sherwin-Williams could selectively move into those categories in a way that strengthens existing relationships rather than forcing entirely new ones. Done right, adjacency doesn’t require reinventing distribution. It just gives the salesforce and the customer another reason to standardize more of their workflow on Sherwin-Williams.

Sustainability is another place where “have to” could become “get to.” Lower-impact coatings—reduced volatile organic compounds, more renewable content, more circular manufacturing—are moving from nice marketing to real procurement criteria for customers with environmental commitments. If Sherwin-Williams can lead on performance and sustainability at the same time, it has a shot at turning regulation and customer pressure into premium pricing and share gains. In coatings, small formulation advantages compounded over years can become a moat.

Finally, none of these choices matter without capital allocation discipline. The menu is familiar: dividends, buybacks, debt reduction, and acquisitions. The leverage taken on for Valspar had been substantially reduced, which reopened flexibility. The question becomes timing and selectivity—using the balance sheet to be opportunistic without returning to the kind of overreach that once made the company vulnerable. If history is any guide, Sherwin-Williams will keep favoring returns over growth for growth’s sake—and that may be the most important strategy of all.

XIV. Recent Developments

Sherwin-Williams’ fourth quarter and full-year 2024 results were a clear confirmation of what the Valspar bet was ultimately about: scale, breadth, and staying power. The company posted record full-year revenue of $23.10 billion, with operating performance that reflected a business now fully built for the post-deal world. Looking ahead, management’s 2025 guidance pointed to continued growth, even with the usual macro question marks hovering over interest rates and the housing market.

In November 2024, Sherwin-Williams joined the Dow Jones Industrial Average—an index change that read like a stamp of permanence. This wasn’t just a coatings company getting noticed. It was the market acknowledging that Sherwin-Williams had matured into something closer to an American industrial mainstay. It also meant a new kind of shareholder base, with more passive capital flowing in simply because the company had earned its spot in the club.

On the input-cost front, the pressure that squeezed margins in 2021 and 2022 eased. Raw material costs stabilized through 2024, giving Sherwin-Williams room to recover and expand margins. And the supply chain work the company had been forced to do during the disruption—investments in visibility, sourcing, and logistics—kept paying off by reducing surprises and smoothing out volatility.

Most importantly, the company’s core customer held up. Even as higher rates slowed residential real estate activity, the professional contractor market stayed resilient. Fewer transactions don’t stop homes from aging. The existing housing stock still needs maintenance, repairs, and refreshes—and that work keeps flowing to painting contractors whether houses are changing hands or not.

XV. Sources & Further Reading

Company Filings - Sherwin-Williams annual reports (2020–2024) - Sherwin-Williams SEC filings: Form 10‑K and 10‑Q - Sherwin-Williams investor presentations and earnings call transcripts - Valspar Corporation historical filings (pre-acquisition)

Industry Research - American Coatings Association industry statistics - Global paint and coatings market analysis reports - National Association of Home Builders housing data

Historical Sources - The History of Sherwin-Williams (company archives) - American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmark designation for Kem‑Tone - Cleveland Historical Society archives - Historical trade publications from the paint and coatings industry

Long-Form Articles and Analysis - Fortune and Forbes coverage of the John G. Breen turnaround era - Wall Street Journal reporting on the Valspar acquisition - Bloomberg analysis of coatings industry consolidation - Harvard Business Review case studies on distribution strategy

Competitor Analysis - PPG Industries annual reports and SEC filings - AkzoNobel annual reports - Masco Corporation (Behr) investor materials - Benjamin Moore product and positioning analysis

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music