Southern Company: America's Energy Infrastructure Giant

Introduction & Episode Roadmap

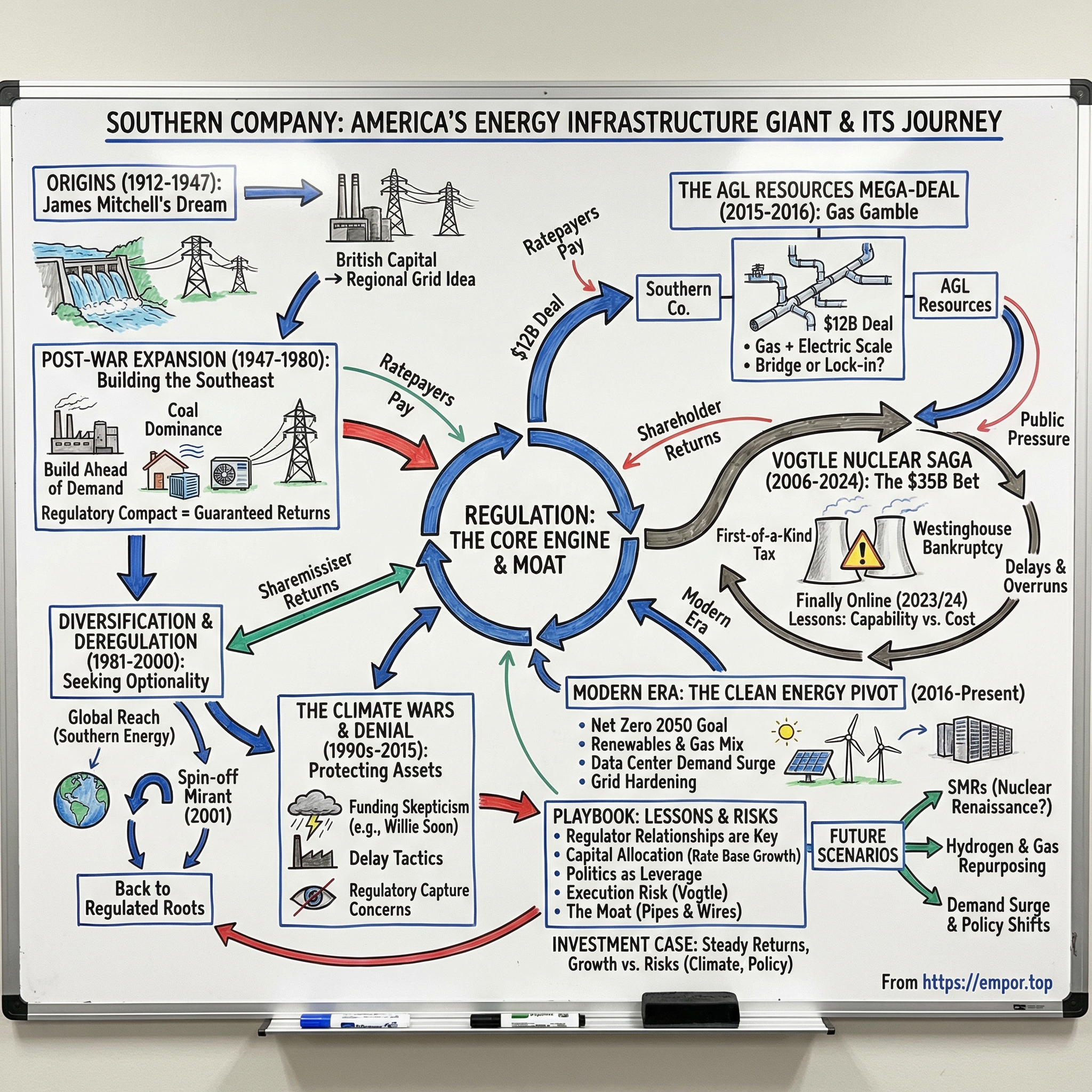

Picture Atlanta in the summer of 2023. Inside Southern Company’s gleaming headquarters, executives were finally getting to do something they’d been chasing for years: celebrate the commercial start of Vogtle Unit 3, the first new nuclear reactor in America in three decades. Outside, environmental groups protested. Shareholders muttered about a price tag that had exploded from an early $14 billion estimate to roughly $35 billion. Utility commissioners took heat from ratepayers staring down higher bills. And yet, against the odds, Southern had crossed the finish line on a project most people had written off as a spectacular, expensive dead end.

That’s the paradox at the center of Southern Company. How did a patchwork of Depression-era Southern utilities grow into the nation’s second-largest utility by customer count? How does a company with a long record of funding climate skepticism also promise net-zero emissions by 2050? And how did management keep regulators, lenders, and the public on board for a nuclear bet that helped drive its lead contractor into bankruptcy?

Today, Southern serves about nine million gas and electric customers across the Southeast through Georgia Power, Alabama Power, Mississippi Power, and its gas businesses under Southern Company Gas. It runs an enormous physical network—roughly 200,000 miles of electric transmission lines and more than 80,000 miles of gas pipelines—employs over 31,000 people, and regularly lands near the top of the Fortune rankings.

But the stats aren’t the story. The story is what those assets and relationships let Southern do—and what they’ve cost. Over more than a century, three threads keep twisting around each other: the electrification of the American South, the hard-edged politics of regulation and environmental policy, and a nuclear saga so complicated it’s become a stand-in for the country’s entire struggle to build big, clean infrastructure.

This is a story about infrastructure as power—in both senses of the word. It’s about the strange economics of regulated monopolies, where your most important stakeholders don’t just live in the market; they sit in state capitols and public service commissions. And it’s about what happens when multibillion-dollar projects collide with construction reality, shifting public priorities, and the unforgiving math of delays.

Origins: James Mitchell's Southern Dream (1912-1947)

In 1912, James Mitchell found a kind of goldmine—except it didn’t glitter. It rushed.

Mitchell, a British-born engineer, had traveled through Alabama and seen what the region’s rivers could do. Water dropping out of the Appalachian foothills wasn’t just scenery; it was stored energy, waiting to be turned into electricity. In a country that was still wiring itself up, he believed the South had one of the best undeveloped hydro opportunities anywhere. The catch was obvious: harnessing it would take real money, real engineering, and patience.

Mitchell’s edge wasn’t that he was the only person to notice the potential. It was that he could finance it. While Wall Street was wary of pouring capital into Southern infrastructure, Mitchell was able to tap British investors in London. And he wasn’t thinking dam-by-dam. From the start, he imagined something bigger: an interconnected power network that could serve customers across state lines, spreading risk, smoothing demand, and making the whole system more reliable.

Southern Company’s own origin marker points back to this moment: it traces its roots to 1912, when the first of a series of holding companies was formed to build a power grid and deliver reliable electricity across the Southeast. But that tidy sentence doesn’t capture how ambitious the idea was. In 1912, much of the South was still rural and agricultural. Electricity was uneven, often limited to city centers and the well-off. Mitchell’s bet was that the region could be electrified at scale—and that doing so would help pull the South into the modern economy.

As the industry matured, the utilities that would eventually make up today’s Southern system—Alabama Power, Georgia Power, Gulf Power, and Mississippi Power—started coordinating operations in the 1920s under a holding company called Commonwealth & Southern. This was the era when utility holding companies were everywhere, and not always for noble reasons. Corporate structures stacked on top of corporate structures could enrich financiers through layers of fees, even as the operating companies—the ones actually building lines and serving customers—were left strained.

Commonwealth & Southern’s most consequential leader was Wendell Willkie, a corporate attorney who would later become the Republican nominee for president in 1940. Willkie believed private utilities could deliver public benefits while still earning a fair return. He pushed to extend service beyond the most profitable urban pockets and supported the broader momentum behind rural electrification.

Then came the threat that changed the industry’s power dynamics overnight: the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Congress created the TVA in 1933 as a federally owned utility designed to bring power and development to the region. That meant direct competition with Commonwealth & Southern’s southern subsidiaries—and an even bigger question hanging over the entire sector: would the federal government step into electricity markets whenever it decided the public interest demanded it?

Willkie fought it hard, taking the TVA to court and arguing that government competition with private enterprise crossed a constitutional line. He lost. After years of litigation, Commonwealth & Southern agreed in 1939 to sell Tennessee Electric Power Company to the TVA for $78 million. It wasn’t just a transaction. It was a signal. The federal government had drawn a boundary—and private utilities would have to operate inside it.

All of this happened against the backdrop of another crackdown: the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935. After the holding-company excesses of the 1920s, the law forced the industry to unwind its most tangled corporate pyramids and divest far-flung subsidiaries. The message was clear: if you wanted to remain a utility powerhouse, you’d need to be simpler, more transparent, and easier to regulate.

Southern Company, as we know it today, was born out of that reshuffling. The company was incorporated in 1946, and the Securities and Exchange Commission approved its current form in 1947—a streamlined holding company that owned the operating utilities directly. Headquartered in Atlanta, it positioned itself as a regional champion for a Southeast that was about to grow fast.

And in those early decades, you can already see the playbook that would define Southern for generations: don’t try to outmuscle regulation—learn it, work with it, and build within it. In a business where prices, profits, and massive capital investments all depend on government approval, relationships with regulators weren’t a side quest. They were the strategy.

Building the Southeast: Post-War Expansion (1947-1980)

In 1945, the American South was still the country’s poorest region: sharecroppers and textile mills, small towns, and a thin industrial base. By 1980, the Sunbelt was booming—pulling in factories, corporate operations, and millions of new residents. Southern Company didn’t just ride that wave. In a very real way, it helped make the wave possible.

The company later described itself as “a catalyst for the broader distribution of affordable electricity,” and this is one of those corporate lines that happens to be true. Before widespread electrification, the South’s growth paths were narrow. Many industries either needed cheap, steady power—or didn’t come at all. Reliable electricity changed the math. It enabled larger factories, modern equipment, and, eventually, the everyday comfort technology that made the region easier to live in and invest in. Air conditioning may not sound like an economic development strategy, but in the South, it absolutely was.

Southern’s postwar play was simple and aggressive: build capacity ahead of demand. Management believed that if they could put power on the grid cheaply and reliably, businesses would follow—and communities would grow into that supply. It was a “build it and they will come” philosophy, and it required constant spending on new plants and new wires. The regulated utility model made that possible. Regulators approved projects, customers paid for them over time through rates, and shareholders earned an allowed return on the capital invested. In the utility world, that arrangement isn’t a footnote. It’s the engine.

Coal was the dominant fuel through these decades. It was abundant, it was inexpensive, and it fit the era’s priority: scale. Southern built huge generating stations and kept pushing for higher efficiency as equipment improved and demand climbed. Those plants, paired with ever-expanding transmission, became the backbone of a region that was trying to modernize fast.

That transmission buildout was its own quiet triumph. Southern constructed a web of high-voltage lines linking major plants to cities, smaller towns, and increasingly rural customers. Interconnection meant the system could shift power to wherever it was needed, making the grid more reliable and reducing the need for each pocket of the region to maintain its own backup generation. The South was no longer a set of isolated electrical islands. It was becoming a network.

But the very structure that enabled this expansion also planted long-term risks. Once a state granted a utility an exclusive franchise, competition largely disappeared. In theory, the “regulatory compact” protected customers: utilities would earn a reasonable, approved return instead of charging whatever they could get away with. In practice, Southern’s regulators often proved sympathetic to the company’s case for more investment, more plants, and higher rates to fund them. For Southern, that relationship was an advantage. For critics, it would later look like the start of a familiar pattern.

The period wasn’t frictionless. As company histories like to put it, Southern dealt with “every conceivable impediment—natural and man-made disasters, hostile takeover attempts, financial challenges.” Hurricanes regularly battered the Gulf Coast. The oil shocks of the 1970s rippled through energy markets and planning assumptions. Environmental rules began to bite, forcing new spending on pollution controls and raising uncomfortable questions about coal’s long-term future.

And then Southern took its biggest leap yet: nuclear power.

The company’s first major nuclear bet was the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant in eastern Georgia, named for a former Georgia Power president. When Vogtle Units 1 and 2 were launched, early cost estimates came in under a billion dollars per reactor. They were Westinghouse pressurized water reactors, each rated around 1,100 megawatts—serious baseload machines designed to run for decades. The units entered commercial operation in 1987 and 1989.

By the time the dust settled, the price tag had climbed to nearly $9 billion—around nine times the initial estimates. Delays piled up. Requirements shifted after the Three Mile Island accident. And nuclear construction proved to be its own category of complexity, with specialized labor, stringent oversight, and unforgiving sequencing. Most of the bill ultimately landed where big utility bills usually land: on ratepayers, spread out through monthly rates. Investors, meanwhile, watched the capital needs balloon and worried about what that meant for returns.

Still, Southern came out of Vogtle 1 and 2 with a very specific takeaway: nuclear was painful, but it worked. It delivered huge volumes of reliable power without the fuel-price whiplash of natural gas and without the smoke-stack politics of coal. If the company could execute better the next time—if it could control construction, align regulators, and avoid the worst surprises—nuclear could look less like a cautionary tale and more like a blueprint.

That belief would be tested more severely than anyone imagined.

Diversification & Deregulation Era (1981-2000)

By the early 1980s, Southern’s leadership was staring at an uncomfortable possibility: the regulated utility model that had powered its postwar rise might not be enough to power its next chapter. The core business was dependable, but it was also bounded—by service territories, by commissions, and by the simple fact that there’s only so much electricity a customer can use. If the South’s growth slowed, would Southern’s growth slow with it?

So Southern went looking for optionality.

In 1981, it became the first electric utility holding company in forty-six years to diversify by forming an unregulated subsidiary. The timing wasn’t subtle. The Reagan-era deregulatory wave was loosening the edges of the industry, and Southern believed it had something valuable to export: the operational know-how of building, running, and financing big energy assets.

That vehicle was Southern Energy, Inc., launched in January 1982. Southern pitched it as a global energy company, and over the next two decades it grew into exactly that—serving ten countries across four continents by building and operating power plants beyond Southern’s regulated home turf. The idea was straightforward: the operating utilities were tightly governed, but the holding company could take its playbook to places where the rules were different.

And the world was inviting it in. Across the 1980s and 1990s, electricity markets opened up as governments privatized state-owned systems and encouraged competition. Southern Energy tried to ride that moment, acquiring assets and developing projects in newly accessible markets, betting that disciplined operations would travel well.

Back at home, Southern was also reorganizing around a lesson it had paid dearly to learn at Vogtle: nuclear isn’t just another generation source—it’s its own profession. In 1991, Southern Nuclear began providing services to the system’s nuclear plants, pulling expertise into one place instead of scattering it across individual utilities.

Then the 1990s arrived, and with them the telecommunications boom. In 1996, Southern Communications Services launched Southern Linc, offering digital wireless communications. The logic was classic utility pragmatism: Southern already controlled valuable rights-of-way and infrastructure corridors for its transmission network. Wireless gear could ride on what the company already owned, while also giving crews a more reliable communications system in the field.

But the biggest pivot came at the turn of the millennium—and it was a pivot back. On April 2, 2001, Southern completed the spinoff of Southern Energy as Mirant Corporation, sending the international generation portfolio out as a standalone company. After nearly twenty years of building a global footprint, Southern decided it didn’t want to be in that business anymore.

Why step away? A few pressures hit at once. The California energy crisis of 2000–2001 bruised the political case for deregulation and made “competitive power markets” sound a lot less like the future and a lot more like a risk. Some international bets didn’t perform as hoped. And management came to a blunt conclusion: Southern’s best, most repeatable advantage wasn’t competing in merchant markets—it was running regulated infrastructure, where returns were steadier and the rules of the game were clearer.

Still, Southern didn’t abandon the wholesale world entirely. The same year as the Mirant spinoff, it formed Southern Power to operate in wholesale markets—owning generation and selling power to third parties, typically under long-term contracts. It was a hedge: participation without a full leap into the volatility that had started to define deregulated power.

From the outside, the message to investors was simple. Southern had tested diversification and liked parts of it—but when forced to choose, it chose the regulated franchise. Build big assets, get them approved, earn an allowed return, repeat. The experiments of the 1980s and 1990s clarified what Southern was, and just as importantly, what it wasn’t.

That focus would matter later. It also wouldn’t stop the next set of storms from forming.

The Climate Wars & Denial Machine (1990s-2015)

Then came the fight Southern couldn’t solve with another plant, another transmission line, or another rate case.

As the climate debate moved from academic journals into public policy, a trail of documents—surfaced through lawsuits and investigative reporting—painted an ugly picture. Between 1993 and 2004, Southern Company paid more than sixty-two million dollars to organizations that promoted climate disinformation. Some of that money backed advertising that insisted climate change wasn’t real, that the science was still “unsettled,” and that cutting carbon would wreck the U.S. economy.

Researchers who tracked corporate influence on climate policy would later describe Southern as a driving force behind climate disinformation. The scale mattered, but so did the style. While ExxonMobil became the household-name villain, Southern’s influence often ran quieter—through trade groups, research funding, and messaging that didn’t always carry the company’s logo. Less visible, same effect: delay.

One of the clearest examples was Willie Soon, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who became a high-profile climate skeptic. Over fourteen years, Soon received more than $1.25 million from Southern and other fossil-fuel interests, with Southern as his largest single donor at $469,560. His work questioning the scientific consensus on climate change later drew scrutiny for serious methodological flaws. But for years, it served its purpose: it gave politicians and industry allies something to point to when they wanted to argue that action could wait.

Southern’s motivation wasn’t mysterious. It was balance-sheet obvious.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, coal supplied most of Southern’s electricity. Those plants weren’t just power sources; they were billions of dollars of invested capital—assets that had been approved by regulators and were being paid off gradually through customer rates. A serious national response to climate change threatened to flip that logic. Coal units could be pushed into early retirement. Or they could be forced to add costly controls, like carbon capture, that weren’t commercially proven at scale.

This is what “stranded assets” looks like in the utility world: customers still paying for plants that can’t—or shouldn’t—run. And the incentives that follow are as blunt as they are powerful. Every year climate policy could be slowed down was another year those plants could keep generating electricity, and generating earnings.

So Southern pressed on multiple fronts. In Washington, it fought climate legislation through trade associations and direct lobbying. In state capitals, it emphasized what carbon regulation would do to power prices and local economies. And by funding think tanks, researchers, and advocacy groups, it helped keep alive the idea that the science itself was up for debate.

At the same time, the company was constantly in court and in hearings. Environmental groups sued Southern repeatedly, challenging air permits and environmental reviews. Southern’s legal teams got very good at the mechanics of delay—dragging proceedings out through procedural battles while the plants in question kept operating.

This was also the era when critics increasingly accused Southern of regulatory capture. State utility commissions are supposed to be the check on monopoly power. But Southern’s operating companies were often among the largest employers and most influential institutions in their states, and executives built deep relationships with commissioners and staff. The revolving door didn’t help the optics: regulators moved into utility jobs, and utility veterans sometimes moved into regulatory roles.

None of this, on its own, was necessarily illegal. Utilities lobby. They donate. They argue their case. But stacked together—political influence, friendly regulators, and money flowing to climate skepticism—it created an ecosystem where meaningful climate action could be postponed for years.

Eventually, the ground shifted. By the mid-2000s, the scientific case for climate change was overwhelming, and public opinion moved with it. Large investors began pressing companies on climate risk. Regulators in some states grew less accommodating. And even without a sweeping national carbon policy, environmental rules started forcing utilities to change how they ran their fleets.

Southern’s repositioning didn’t happen all at once. But by 2015, the company had started to adjust its public posture, even as coal still accounted for a meaningful share of generation. The question hanging over the story wasn’t whether Southern could change its messaging. It was whether it was truly changing its strategy—or just swapping tactics to protect the same underlying business model.

The AGL Resources Mega-Deal (2015-2016)

By 2015, Southern’s public posture was starting to shift. Coal was slowly losing its grip. Renewables were no longer a sideshow. And natural gas—the fuel that had already reshaped American power markets—was looking less like a bridge and more like the main road.

So on August 24, 2015, Southern Company and AGL Resources announced a deal designed to lock that road in place. The acquisition carried an enterprise value of about $12 billion, including roughly $8 billion in equity value. For AGL shareholders, it was simple: each share would be converted into $66 in cash. For Southern, it was a statement that the next era of “energy infrastructure” wasn’t just power plants and transmission lines. It was pipelines, meters, and gas distribution networks.

CEO Tom Fanning didn’t pretend it was a quiet, defensive move. He framed it as an offensive one: Southern would be “positioned to deliver even greater customer and shareholder value by playing offense in developing the infrastructure necessary to meet America’s growing demand for natural gas.” In utility-speak, that was chest-thumping. This wasn’t incremental. This was a bet.

What AGL brought to the table was something Southern didn’t have at scale: a major gas distribution business. AGL, based in Atlanta, ran gas utilities serving customers across multiple states, with particularly strong positions in places like Georgia, Virginia, and Illinois. Together, the combined company would operate eleven regulated electric and gas distribution utilities, serving about nine million customers.

The strategic logic went beyond getting bigger. Gas had become the go-to replacement for coal: cheaper to build than new coal or nuclear, able to ramp quickly to balance renewables, and emitting less carbon than coal when burned for power. By owning more of the gas delivery system—not just buying gas and burning it—Southern was trying to control a larger slice of the energy value chain as the grid evolved.

There was also a quieter, more defensive angle. Electric utilities could see the outlines of a threat: rooftop solar and other distributed energy resources gave customers ways to buy less from the grid. Gas distribution didn’t face the same kind of consumer-level bypass. You can put panels on your roof. You can’t install a personal natural gas field in your backyard. In that sense, gas was a hedge—one more regulated monopoly franchise, protected by pipes in the ground and state-approved returns.

The merger closed on July 1, 2016, and AGL became Southern Company Gas. By the standards of giant utility combinations, integration was relatively smooth, though “synergies” still meant hard choices in staffing and operations. Coming out the other side, Southern had become one of the country’s biggest utility platforms, now spanning both electricity and gas at massive scale.

The physical footprint told the real story: roughly 200,000 miles of electric transmission lines, plus more than 80,000 miles of gas pipelines. This is the kind of infrastructure that’s almost impossible to duplicate. Once it’s built and regulated, it becomes a durable moat—expensive to replace, hard to compete with, and typically allowed to earn a steady return over decades.

But the timing came with a catch. While Southern was digesting AGL, it was also staring down its most punishing challenge: finishing Vogtle Units 3 and 4. The management attention and financial flexibility that might have gone into rescuing a troubled nuclear construction project now had to share oxygen with a major acquisition.

And the optics were complicated. Gas was cleaner than coal, but it was still a fossil fuel. Doubling down on gas infrastructure signaled a belief that gas would remain central for decades. Environmental advocates argued it was a lock-in—that building more pipelines and meters today made it harder to cut emissions fast enough tomorrow.

For investors, though, the takeaway was unmistakable: Southern was willing to spend big to shape its future. Whether the premium paid would prove wise depended less on deal mechanics than on forces no utility fully controls—regulators, climate policy, and the speed of the energy transition.

And while Southern was laying pipe for the long run, the nuclear clock at Vogtle was still ticking.

Vogtle Nuclear Saga: America's Last Big Nuclear Bet (2006-2024)

The story of Vogtle Units 3 and 4 is, in a lot of ways, a story about institutional memory—or the lack of it. When Southern Nuclear began seriously developing the expansion in 2006, leadership believed the hard-earned lessons of Units 1 and 2 could be turned into a repeatable playbook. Pick a design built for easier construction. Lock in regulatory approvals early. Use a fixed-price contract with a major contractor. Build the next two units faster, cleaner, and with fewer surprises.

Almost none of that held.

Southern and its partners selected Westinghouse’s AP1000, a new design built around passive safety—systems meant to keep a reactor safe without relying on layers of pumps, motors, and operator intervention. Pair that with modular construction, where big components are fabricated off-site and assembled more like a kit, and the promise was compelling: less complexity in the field, fewer delays, lower cost.

In reality, the AP1000 wasn’t a mature, proven product. It had never been built before. And that mattered, because “first-of-a-kind” isn’t just a label—it’s a tax. Design work that looked complete on paper kept evolving in the real world. Changes rippled through the project, forcing rework on parts already fabricated or installed. The modular approach that was supposed to simplify the job created its own headaches: modules built in different facilities still had to fit together perfectly on-site, and they often didn’t.

The original expected building cost for the two reactors was $14 billion, with Georgia Power’s share around $6.1 billion. Georgia Power led the ownership group, alongside Oglethorpe Power, MEAG Power, and Dalton Utilities. That structure spread risk, but it also meant more cooks in the kitchen as schedules slipped and the bill climbed.

In February 2012, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved the construction license—making Vogtle the first new nuclear project approved in the U.S. since before Three Mile Island in 1979. The vote wasn’t unanimous. Chairman Gregory Jaczko cast the lone dissent, citing post-Fukushima safety concerns. But the problems that ultimately broke the project’s schedule and budget weren’t exotic disaster scenarios. They were far more ordinary: design churn, quality problems, execution mistakes, and the brutal difficulty of rebuilding a supply chain for an industry that had largely stopped building.

On paper, the contract structure was supposed to protect the owners. Westinghouse guaranteed costs through a fixed-price arrangement. In practice, the fine print still left room for change orders and schedule adjustments. As the overruns piled up, Westinghouse’s losses did too—and eventually the situation became untenable.

In March 2017, Westinghouse filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, driven by losses on its U.S. nuclear projects. That bankruptcy didn’t just embarrass the industry; it detonated the original management plan for Vogtle. Southern Nuclear took over construction oversight and brought in Bechtel as the day-to-day construction manager, replacing Westinghouse’s construction subsidiary.

Then came the moment that revealed just how far the project had drifted. A documentation crisis surfaced: incomplete and missing inspection records left a backlog of more than 10,000 records. In nuclear construction, paperwork isn’t bureaucracy—it’s part of the plant. If you can’t prove a weld, a component, or a process met specification at the time it was done, you may have to treat it as if it never happened. Work already “finished” suddenly had to be re-verified, and sometimes redone. More time. More money. More distrust.

Southern Nuclear was, effectively, forced to relearn how to build a nuclear plant while it was still building one. It hired veterans from other projects, tightened quality control, and built new processes to wrestle the site into something closer to predictable execution. The project did, gradually, come under control. But the learning curve was punishing.

By the end, Vogtle Units 3 and 4 came online roughly seven years late, at a total cost of about $35 billion—more than double the initial estimate. Unit 3 entered commercial operation on July 31, 2023. Unit 4 followed on April 29, 2024. The finish mattered: it was the first new nuclear plant to come online in the United States since the 1990s, proof that the country could still complete a project like this. It was also proof that “can” and “can at a reasonable price and timeline” are two very different things.

As for who paid: Georgia Power ratepayers absorbed major costs through increases approved by the Georgia Public Service Commission. Shareholders took hits as well. The federal government supported the effort through loan guarantees and production tax credits. And Toshiba—Westinghouse’s parent—ended up making billions of dollars in payments to settle claims tied to the construction failures.

Vogtle leaves a set of hard lessons for anyone still serious about new nuclear. First-of-a-kind designs punish optimism, because paper plans can’t fully capture field reality. Fixed-price contracts aren’t truly “fixed” when change orders are inevitable and contractor bankruptcy is on the table. And perhaps most importantly: when an industry goes decades between builds, the talent, the suppliers, and the muscle memory disappear faster than anyone wants to admit.

And yet: the reactors now run. They produce carbon-free electricity around the clock, independent of weather, delivering exactly the kind of firm clean power that renewables-heavy grids increasingly need. If you’re bullish on nuclear as a climate tool, Vogtle is evidence that new builds are still achievable. If you’re skeptical, it’s the case study you point to when you argue nuclear can’t compete on cost and speed with solar, wind, and storage.

Southern’s management argues there’s one lasting asset that came out of this ordeal: capability. After completing one of the most complex construction projects in the American utility industry in decades, Southern Nuclear now holds experience few others have. Whether that becomes a durable advantage—or remains a painfully expensive one-off—will shape what Southern can credibly attempt in the next era of American energy.

Modern Era: The Clean Energy Pivot (2016-Present)

Open Southern Company’s investor deck today and you’ll see the line front and center: the goal is net zero greenhouse gas emissions across its electric and gas businesses by 2050. Coming from a company that spent years helping fund climate skepticism, it’s a dramatic repositioning. It’s also the kind of target that invites skepticism of its own—2050 is far enough away that it still leaves plenty of room for emissions in the meantime.

By the mid-2020s, Southern looked like the sum of every bet it had ever made, both the deliberate ones and the forced ones. As of late 2025, it ranked 163rd on the Fortune 500 and employed about 31,300 people. The generation mix had moved meaningfully toward natural gas, pushed along by coal retirements and reinforced by the AGL acquisition. Renewables were growing, but they were still not the dominant force in the portfolio.

AGL, in particular, did what Southern hoped it would do: it made the business more pipeline-and-meter steady. Gas utilities tend to deliver stable, regulated returns and, at least for now, they face less consumer-level disruption than electricity. And the gas network created a new option set. Southern could plausibly argue that those pipes might someday carry hydrogen or other lower-carbon gases, using much of the same infrastructure with modifications.

On the electricity side, the renewables ramp did speed up—just not overnight. Southern Power, the company’s competitive generation arm, built out solar and wind projects across the country and sold the output under long-term contracts to customers looking for clean power. Meanwhile, the regulated operating utilities added renewables as costs fell and regulators became more supportive.

Then the demand story flipped.

For years, U.S. utilities got used to an unglamorous reality: electricity demand was flat, sometimes even declining, as efficiency improved. That changed with data centers. Artificial intelligence workloads require massive computing power, and computing power consumes massive amounts of electricity. In Southern’s territory, big tech companies signed agreements to buy power from its utilities, and some arrangements involved direct connections to generating plants.

For Southern, the timing couldn’t have been better. Vogtle and other recent additions meant the company wasn’t starting from zero; it had capacity on hand. And compared with nuclear-scale timelines, Southern could add renewables and natural gas generation relatively quickly to chase the new load.

At the same time, the grid itself started demanding more attention—and more money. Modernization and resilience spending became a bigger piece of the capital plan as extreme weather intensified. Southern’s footprint gets hit from every angle: hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, tornadoes across the interior Southeast, and longer, hotter heat waves that push cooling systems and peak demand to the edge. Hardening poles, wires, substations, and control systems takes sustained investment, and regulators have generally allowed the company to recover those costs through rates.

Which brings the story back to the same leverage point it always does: regulation.

Southern’s relationships with state commissions remain a core strategic asset. The Georgia Public Service Commission’s willingness to allow substantial recovery of Vogtle costs from ratepayers, despite the scale of the overruns, was a vivid reminder of what constructive regulatory treatment can mean in practice. Commissions in Alabama, Mississippi, and in the states served by Southern Company Gas have also backed major investment programs.

But the clean energy pivot isn’t a victory lap—it’s a balancing act. Environmental advocates want faster fossil retirements and a sharper move into renewables. Ratepayer advocates argue customers shouldn’t be asked to fund expensive clean-energy projects when cheaper options exist. And shareholders still expect returns on the huge amounts of capital the transition requires.

That’s Southern’s modern challenge in a sentence: it owns some of the most valuable regulated infrastructure in the country, and it should throw off returns for decades. But the transition is rewriting the definition of “durable” assets in real time. Southern’s future depends on whether it can keep building—cleaner, bigger, and more resilient—without losing the regulatory and public support that makes the whole model work.

Playbook: Business & Regulatory Lessons

Southern Company’s history reads like a field guide to how regulated utilities win—and what that style of winning can do to the rest of the system. At its best, the company built essential infrastructure at scale and kept the lights on across a fast-growing region. At its worst, it showed how easily “public service” can blur into politics, and how hard it is to unwind decisions once the concrete is poured and the assets are in rate base.

Start with regulation, because that’s where the whole game is played. Utility commissions are asked to oversee enormously complex businesses with limited time, limited staff, and often limited technical depth. Commissioners rotate in and out. Cases move fast. And the utility typically controls the most detailed information—engineering plans, cost estimates, reliability models, and the thousand assumptions that sit underneath a rate request.

Southern didn’t need to break laws to turn that structure into advantage. The playbook was simpler: be present, be useful, be “reasonable.” Invest in relationships with commissioners and staff. Provide the analysis that frames the decision. Over time, those habits compound. When disputes inevitably show up—storm costs, fuel charges, construction overruns—the utility that has built trust often gets more patience, more credibility, and more benefit of the doubt than the one that shows up only to fight.

That dynamic is why “regulatory capture” is such a loaded phrase here. Not because it requires bribery or obvious illegality, but because the system naturally drifts toward the entity that has the expertise, the continuity, and the incentive to keep showing up.

Then there’s capital allocation, which works differently in a regulated monopoly than it does almost anywhere else. In competitive markets, the big question is whether customers will pay. In regulated utilities, the big question is whether regulators will let customers pay—through approved rates—so shareholders can earn the allowed return. Southern proved the upside of that model by building huge amounts of generation and grid infrastructure to meet growth. It also lived the downside: Vogtle Units 1 and 2 eventually earned returns despite massive overruns, but the sticker shock damaged credibility and raised the bar for the next big ask.

Vogtle Units 3 and 4 drove those lessons into bedrock. “Fixed-price” contracts don’t protect you when change orders are constant and the contractor can’t survive the losses. First-of-a-kind technology carries a tax that even experienced teams underprice. And in industries that build mega-projects only once in a generation, capabilities decay—supply chains shrink, skilled labor thins out, and project management muscle memory disappears. Southern ultimately finished the job, but only after it effectively rebuilt nuclear construction management while the clock and the bill were still running.

Politics, too, wasn’t a side activity—it was a source of leverage. Southern’s advocacy helped shape legislation, regulatory posture, and public narratives around energy. The company’s long support for climate denial shows the sharp edge of that leverage: it was willing to fund messaging that protected coal-era assets, even as the broader social costs of delay mounted. Whatever you think of the motivations, the tactic was consistent with the core incentive of regulated infrastructure: protect the existing base, extend the useful life, avoid disruption that strands investments.

And that brings us to Southern’s moat. Transmission lines and gas pipelines are the purest kind of hard-to-duplicate asset. Once they’re built and regulated, there’s usually no direct competition. The “regulatory compact” creates a path to recover costs and earn a return. But the moat isn’t purely economic—it’s political. It holds as long as commissions and state leaders continue to support the bargain. Lose that support, and the advantage can shrink fast.

Which is why the central management challenge never changes, no matter how the generation mix shifts. Shareholders want returns. Customers want low bills and high reliability. The public increasingly wants cleaner energy and real emissions cuts. Regulators sit in the middle, trying to balance all three while also responding to outages, storms, and headlines. Southern has been unusually skilled at managing those tensions over decades. Critics argue the balance has often tilted toward shareholders and the company’s preferred build-out, with ratepayers carrying too much of the risk.

Finally, crisis management is where the playbook gets stress-tested. Southern’s climate arc—denial, delay, and eventual accommodation—shows how costly it can be to optimize for the short term when the long term is shifting under you. Vogtle shows the other side: even a project that looks doomed can be dragged across the finish line with enough resources, political support, and persistence. But “can be finished” isn’t the same as “should be repeated.”

That’s Southern Company in one sentence: a machine built to construct and operate infrastructure inside a regulatory system—and a reminder that, in energy, the hardest problems aren’t just engineering problems. They’re governance problems.

Analysis & Investment Case

Southern’s financial story starts with the thing that makes utilities feel almost weird compared to most businesses: it doesn’t “win” by outcompeting rivals. It wins by investing—then getting permission to earn on that investment.

That permission comes through rate base. Rate base is essentially the pile of power plants, wires, substations, and pipelines regulators agree the company can pay for through customer rates. Build more approved infrastructure, and that rate base grows. If the projects are executed well and the regulators stay supportive, earnings tend to rise with it. That’s why Southern throws off the kind of cash flow profile that dividend investors love: not flashy, but generally steady, because customers keep paying their bills and regulators keep the system functioning.

Against peers, Southern looks like a classic regulated utility—with a few important twists. NextEra stands out as the outlier: it pushed harder into renewables through competitive generation and, for long stretches, investors rewarded it with richer valuation multiples. Duke and Dominion are closer cousins, running similarly regulated playbooks and facing many of the same tradeoffs: big capital plans, commission relationships, storm risk, and constant fights over what customers should be asked to fund.

The bull case for Southern is basically a bet that the next decade looks like an infrastructure build cycle—and that Southern is positioned to be one of the winners. The U.S. is short on grid capacity and modernized equipment, and utilities are the institutions that actually know how to permit, finance, and operate that kind of long-lived hardware. Then there’s load growth, which utilities haven’t been able to count on for years. Data centers—and the AI compute boom driving them—have changed the conversation from “flat demand forever” to “we might need a lot more power.” In that world, Southern’s territory, scale, and regulator muscle memory are assets that can translate into more capital deployed and more earnings.

There’s also an option embedded in Vogtle that’s easy to miss: capability. If nuclear power truly comes back—through small modular reactors or other advanced designs—Southern would be one of the few U.S. utilities that can credibly say it has lived through modern nuclear construction, survived it, and finished. SMRs are pitched as cheaper and simpler than traditional mega-reactors. Whether that proves true is still an open question. But if a nuclear renaissance does arrive, Southern wouldn’t be starting from zero.

The bear case is about the ways the ground can shift under a regulated monopoly. Fossil assets can become liabilities faster than planned, whether because climate policy tightens, renewables keep getting cheaper, or public tolerance for emissions drops. Distributed energy resources—rooftop solar, home batteries, electric vehicles managed intelligently—could change demand patterns and reduce how much customers buy from the utility. And then there’s political risk. Southern’s regulatory relationships are a strength, but they’re also a dependency. Elections change commissions. Public priorities change. A utility that’s used to constructive treatment can find the tone of oversight shifting quickly, especially after big bill increases or high-profile project mistakes.

If you apply Porter’s Five Forces, you get a picture that’s almost comically favorable on paper. New entrants can’t realistically build a parallel grid. Most customers can’t switch providers. Rivalry is limited because the service territories are carved up. The real pressure comes from substitutes—behind-the-meter solar and storage being the obvious ones—and from the fact that the “buyer,” in practice, isn’t just the customer. It’s the regulator acting on the customer’s behalf.

Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers points at similar strengths. Southern has scale, and it benefits from an interconnected system that becomes more valuable as it expands. Switching costs are real for most customers. And process power matters more than people think: the accumulated capability to operate complex infrastructure, manage storms, navigate rate cases, and execute multi-year capital programs is a form of advantage that doesn’t show up neatly on a balance sheet.

If you want one KPI that captures Southern’s forward momentum, it’s rate base growth. That’s the engine. Faster growth usually means more approved investment and more earnings capacity. Slower growth can signal fewer opportunities, tougher regulators, or projects that are getting delayed. The practical version of this: track what Southern says it plans to build, what it actually spends, and how the regulated rate base is trending across its operating companies.

A second metric to watch is the gap between the allowed return on equity that regulators approve and the return the company actually earns. Utilities don’t automatically hit the allowed number. Outages, bad cost control, construction delays, and disallowed spending can all drag earned returns below what was “permitted.” When that gap widens, it often means execution or regulatory friction is rising.

Finally, there’s ESG—because for utilities, reputation and policy aren’t separate from valuation. Southern’s history of funding climate denial creates a lingering overhang: reputational damage, potential legal exposure, and skepticism that any long-dated net-zero target is more than messaging. The pledge to reach net zero by 2050 may help, but investors who care about it will ultimately judge Southern by the pace of real emissions cuts, the choices it makes about gas infrastructure, and how it manages the tradeoff between reliability, affordability, and decarbonization.

Epilogue & Future Scenarios

The next decade will show whether Southern’s biggest advantage—its ability to build and earn on long-lived infrastructure inside a supportive regulatory system—still works in an energy world that’s changing faster than the last one ever did. A few plausible paths are already taking shape.

One is a return to nuclear, but in a different form. Small modular reactors are pitched as the antidote to the Vogtle problem: smaller units, simpler construction, and, in theory, fewer ways for schedules and budgets to spiral. If the technology matures, Southern is one of the few U.S. utilities that could credibly claim it has the in-house scars and expertise to attempt it. The company has expressed interest in SMRs, and a pilot project within the decade is at least imaginable. The question is whether “modular” actually means repeatable in the real world, or whether it becomes another version of first-of-a-kind risk.

Another path runs straight through the pipes Southern bought with AGL. Hydrogen and other lower-carbon gases are often described as a way to decarbonize parts of the economy that electricity alone won’t easily reach. In the bullish version of this story, Southern’s vast gas network becomes an asset that can be repurposed—moving hydrogen produced from renewable electricity and extending the useful life of infrastructure that might otherwise be politically and economically squeezed. In the bearish version, the economics never quite work, and those same pipes look less like a moat and more like a stranded-asset debate waiting to happen.

Then there’s the demand surge that utilities have been dreaming about for years. Data centers and broader electrification are turning “flat load forever” into “we might need a lot more power, and soon.” Southern’s territory has become attractive to developers, and it isn’t coming into this moment empty-handed. Vogtle and other recent additions mean capacity exists that many peers don’t have. But demand growth is only a gift if it can be served profitably and cleanly. Meeting new load while keeping emissions commitments—and keeping regulators and customers onside as bills change—will be a delicate, high-stakes balancing act.

Which leads to the biggest swing factor of all: regulation itself. Reform could cut both ways. If policymakers push harder toward competition in electricity markets, the protective logic of the franchise can weaken. If, instead, the national priority becomes reliability plus decarbonization plus more grid investment, Southern’s model can look not just viable but essential—more capital deployed, a larger rate base, and a path to steady returns. Historically, politics in Southern’s states have tended to favor incumbent utilities. But that’s a trend, not a law of nature, and big bill increases or high-profile failures can change the mood quickly.

Meanwhile, the weather is getting more expensive. Southern’s footprint is exposed along the Gulf Coast, where hurricanes can erase years of reliability work in a single night, and across a region where rising temperatures push cooling demand and stress grid equipment. Hardening infrastructure against those threats takes sustained capital spending—and while regulators have often been willing to let utilities recover those costs, ratepayers don’t have infinite patience.

Finally, there’s the unresolved question every utility is quietly asking: what happens if the customer starts behaving like a competitor? Rooftop solar and battery storage keep improving. If adoption accelerates, more customers could produce a meaningful share of their own electricity, leaving the grid to serve as backup and balancing system. That can be an opportunity—new services, new tariffs, new ways to orchestrate distributed resources—or it can become a fight over who pays for the wires when fewer people want to buy as much energy through them. The outcome depends as much on regulatory design as it does on technology.

Southern’s story is a reminder of how strange essential infrastructure businesses really are. They provide services modern life can’t function without. They operate under rules that intentionally blunt competition. And they invest on time horizons that outlast political cycles and executive tenures. In that world, companies can become durable wealth creators—or value traps—based on management choices, regulatory relationships, and whether yesterday’s “safe” assets become tomorrow’s liabilities.

Above all, Southern shows that infrastructure is never just engineering. The company became powerful by mastering the political system required to build physical systems. Whether that playbook still works as the energy transition accelerates will decide what Southern looks like in its next century.

Recent News

Southern Company reported fourth quarter 2025 results in late January 2026, and the headline was steadiness: earnings came in largely in line with what analysts expected. Management used the moment to do what utilities do when they want markets to stay calm—reaffirm long-term earnings guidance and keep the capital investment story intact. And that story, increasingly, is load. Southern said its pipeline of data center demand kept growing, with new agreements to supply power to major technology facilities.

On the regulatory front, Southern got another reminder of where its real leverage lives. In December 2025, the Georgia Public Service Commission approved the company’s latest rate case, allowing recovery of ongoing investments in grid modernization and clean energy. Just as important, the decision effectively validated Southern’s capital spending plan through 2028—more visibility into future rate base growth, and more confidence that the buildout can be financed and paid back through customer rates.

At Vogtle, the narrative also shifted from construction trauma to operations. Unit 4 marked its first full year of commercial operation in April 2025, and Southern said performance came in stronger than early expectations, with capacity factors exceeding initial projections. With both new reactors running, Southern Nuclear began studying potential power uprates for the units—incremental output increases of several percent, without building anything new.

And then there’s the reality that now defines every Southeastern utility: weather. The 2025 hurricane season damaged Gulf Coast infrastructure across Southern’s footprint. The company said restoration costs were expected to be recovered through insurance and regulatory mechanisms, and it credited grid-hardening investments with reducing outage duration compared with storms of similar intensity in prior years.

Links & Resources

SEC Filings and Investor Materials

Southern Company files annual reports (10-K), quarterly reports (10-Q), and current reports (8-K) with the Securities and Exchange Commission. If you want the unfiltered version of the story—how management frames the business, what risks keep showing up in the footnotes, and where the money is really going—this is where it lives.

Georgia Public Service Commission

The Georgia PSC maintains public dockets covering Southern Company’s major rate cases and integrated resource plans. The orders and testimony are the clearest window into how the “regulatory compact” actually works: what investments get approved, what costs are recoverable, and how commissioners justify the tradeoffs.

Nuclear Regulatory Commission

The NRC maintains extensive documentation on the Vogtle construction project, including inspection reports, license amendments, and safety evaluations. For anyone trying to understand how a nuclear mega-project goes sideways—or how it gets dragged back into control—these records show the project in the details, not the headlines.

Energy Information Administration

The EIA publishes data on Southern Company’s generating fleet, including capacity, generation, and fuel consumption. It’s the most straightforward way to track how Southern’s mix has evolved over time and how it compares with peers.

Academic Research

Researchers at institutions including Harvard, Brown, and UC San Diego have published work on utility-industry climate denial and disinformation efforts, including Southern Company’s funding of climate skeptic organizations. These studies help map the network of influence—who funded what, when, and to what end.

Industry Analysis

Utility analysts at major investment banks publish research on Southern Company and its peers. Most of it sits behind institutional paywalls, but summaries often surface around earnings, major regulatory decisions, and big project updates—useful for understanding the prevailing “street” narrative, even if it’s not the whole truth.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music