Sempra Energy: The Energy Infrastructure Colossus

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

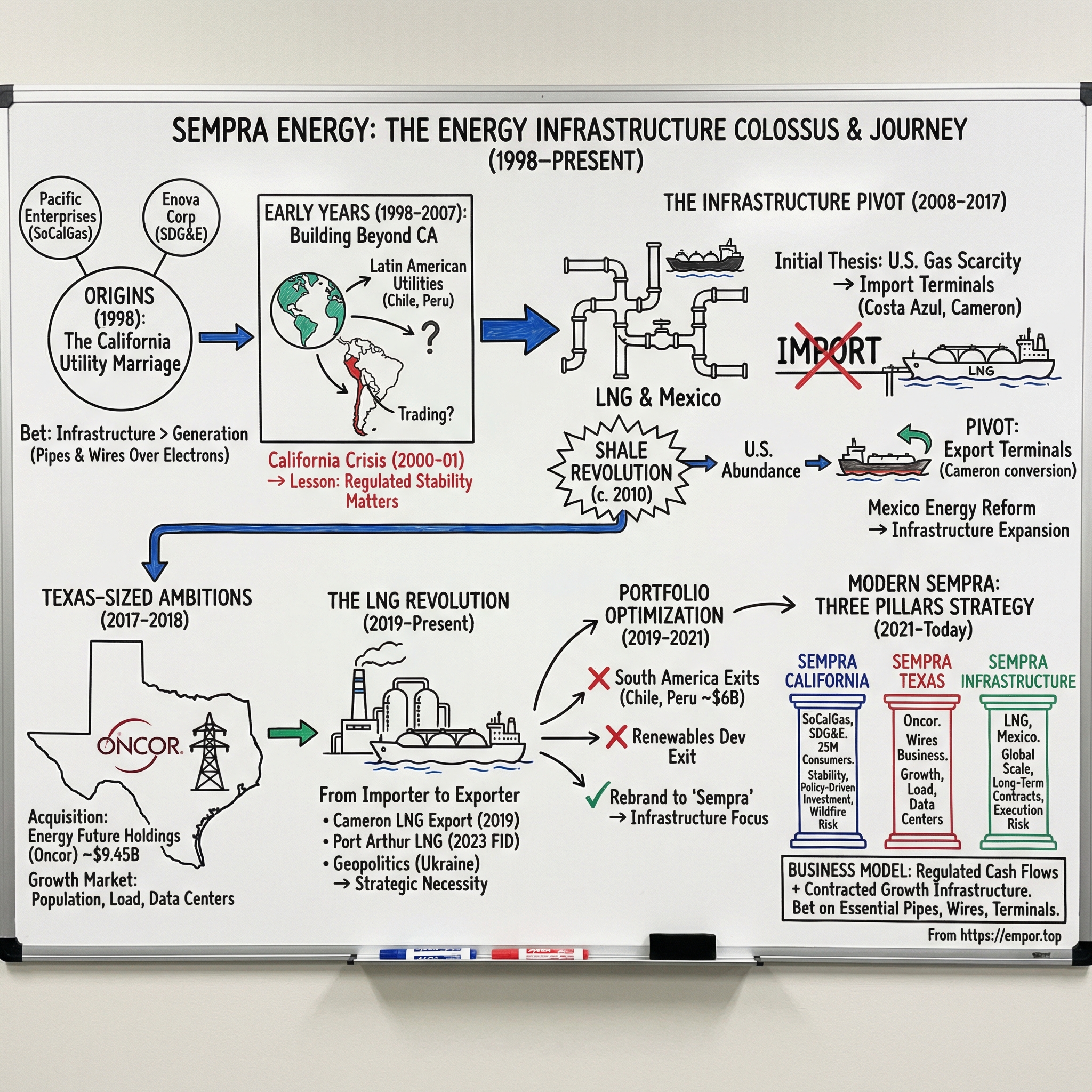

Picture a fluorescent-lit conference room in downtown San Diego, June 1998. Two teams of executives—one from Pacific Enterprises, the other from Enova Corporation—sit across a table, documents spread out, pens poised. They’re about to merge the parent companies of Southern California Gas Company and San Diego Gas & Electric into a single business.

On paper, it looks like a standard utility deal: bigger footprint, shared costs, smoother operations. But the real wager in that room is much more interesting. They’re betting that the winners in energy won’t necessarily be the companies that generate it. They’ll be the companies that control the pipes, wires, terminals, and rights-of-way—the unglamorous infrastructure that makes the whole system work.

Fast forward to today and that bet has compounding written all over it. Sempra now sits north of a $90 billion market cap. It owns California’s marquee gas and electric utilities, controls Texas’s largest transmission and distribution network through Oncor, and operates LNG infrastructure that has become strategically important far beyond U.S. borders. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, American liquefied natural gas turned into a critical supply source for Europe—and Sempra has been positioned right in the flow of that shift.

So how did a California utility merger turn into North America’s premier energy infrastructure company?

The answer is a chain of calculated moves: leaning into deregulation when it created openings, choosing infrastructure over generation, riding the shale revolution, and helping flip the U.S. from an expected natural-gas importer into a global supplier. Along the way, Sempra becomes a case study in regulated utilities, deregulation arbitrage, infrastructure roll-ups, and the LNG revolution that reshaped energy markets.

What makes the story especially compelling for investors is the evolution of the business model. Sempra starts out doing what utilities do—earning steady, predictable returns by moving electrons and molecules to homes and businesses. Then, over the decades, management stretches that stable base into something much bigger: a diversified energy infrastructure platform tied to some of the most consequential energy trends in the world. If you want to understand where North American energy is headed, understanding that transformation is a great place to start.

II. Origins: The Great California Utility Marriage (1990s–1998)

Sempra’s story doesn’t start with a ticker symbol. It starts with streetlights.

Southern California Gas Company traces its roots back to 1867, when investors formed the Los Angeles Gas Company to bring light to a dusty, fast-growing town. Over the next century, through mergers and steady expansion, that early gas business evolved into what became the largest natural gas distribution utility in the United States.

San Diego Gas & Electric had its own long runway. Incorporated in 1881, it grew alongside a port city that was steadily turning into a major metro area. By the mid-twentieth century, SDG&E wasn’t a “utility” in the abstract. It was the region’s physical backbone—electric lines, gas mains, crews, trucks, meters, and the day-to-day work of keeping a modern city running.

Neither company was glamorous. That was the point. They were the infrastructure underneath everything else.

Then the 1990s arrived, and California decided to remake the electricity business. The state launched one of the most ambitious deregulation efforts in the country, aiming to unbundle the old vertically integrated utility model. The promise sounded simple: split generation from transmission and distribution, introduce competition in power production, and lower prices for customers.

In the moment, it felt like the future. In practice, it created a scramble. Utility executives across California suddenly had to plan for a world where parts of their business might become competitive, margins might compress, and regulatory frameworks might shift under their feet.

Pacific Enterprises, the holding company for SoCalGas, and Enova Corporation, the parent of SDG&E, saw a clear move: combine. Together, they could create the largest regulated natural gas and electric utility customer base in the United States—roughly 21 million customers across Southern California. That kind of scale brought operating leverage, a bigger presence in front of regulators, and, crucially, a broader set of “wires and pipes” that would stay essential no matter how deregulation played out.

The merger talks ran right alongside the state’s deregulation drama. Both sides understood what was really happening: generation might become a competitive battleground, but transmission and distribution were still the toll roads. Whoever owned the infrastructure would remain indispensable.

On October 5, 1998, the merger closed. Sempra Energy began trading at a market value of about $6.2 billion. The company set up in San Diego, keeping a direct line of continuity with SDG&E’s local identity and operating culture.

Even the name carried a message. Sempra came from the Latin “semper,” meaning “always”—a nod to reliability, permanence, and the idea that this business would be built to last.

This wasn’t just a defensive marriage of two utilities trying to survive deregulation. It created a platform: a base of regulated cash flows, spanning both gas and electric distribution, that could fund whatever came next. The thesis was simple and, as it turned out, prescient: energy can be chaotic, but the owners of essential infrastructure get paid through the chaos.

And the chaos came quickly. Within two years, California’s deregulation experiment unraveled spectacularly—skyrocketing prices, rolling blackouts, and the eventual bankruptcy of Pacific Gas & Electric. In that environment, Sempra’s emphasis on regulated distribution over competitive generation mattered. While others stumbled in the market’s whiplash, Sempra had positioned itself as part of the infrastructure backbone that would endure, regardless of how the rules were rewritten.

III. The Early Sempra Years: Building Beyond California (1998–2007)

Richard Pygott, Sempra’s first CEO, took over a newly merged company with a dependable core in California—and a big question hanging over it: should Sempra stay home and optimize its regulated base, or follow the late-1990s fashion and go global?

At the time, utility globalization was in full swing. Governments were privatizing electricity systems across Latin America and beyond, and Western utilities were lining up to buy them—convinced their operating playbooks could travel, and that fast-growing markets would do the rest.

Sempra jumped in early. In 1999, it acquired two South American utilities: Chilquinta Energía in Chile and Luz del Sur in Peru. The logic was straightforward and very “1999”: rising demand, regulatory structures that looked familiar to U.S. operators, and assets coming to market at prices that seemed attractive.

Chilquinta served Chile’s Valparaíso region, one of the country’s key economic areas. Luz del Sur supplied electricity to Lima’s southern districts, with a customer base concentrated in Peru’s capital. Compared to California—mature, heavily regulated, and slow-growing—these investments offered something utilities crave: real organic growth as electrification and income levels increased.

Then California reminded everyone what kind of business this really was.

The state’s deregulation experiment didn’t just wobble—it detonated. In 2000 and 2001, the California energy crisis tore through the grid and the political system at the same time. Rolling blackouts became part of life. Wholesale electricity prices didn’t merely rise; they went vertical, surging from normal levels around $30–$40 per megawatt-hour to spikes above $1,000. And later investigations showed that traders—Enron most notoriously—were exploiting the market with schemes that sounded like movie titles: “Death Star,” “Fat Boy,” and others.

Sempra’s seat in the blast radius was… complicated. SDG&E, unlike the state’s larger utilities, had been allowed to pass higher wholesale power costs straight through to customers. That regulatory detail protected the utility’s financial health, but it made San Diego the epicenter of public fury. Electric bills didn’t just go up—they shocked households, in some cases tripling from normal levels. The outrage wasn’t abstract; it was personal, and it landed on Sempra’s doorstep.

For management, the crisis was a crash course in what “regulated” really means. This wasn’t only a story about power markets and procurement. It was a story about governors, legislatures, and regulators improvising in real time—imposing price caps, negotiating long-term supply contracts, and ultimately having the state buy power directly for utilities. Sempra came away with a lesson that would echo through its future strategy: in industries where rules determine returns, political trust and credibility can matter as much as operational performance.

At the same time, Sempra reached beyond the traditional utility model. The company expanded into commodity trading and energy marketing, building a business designed to make money in the very volatility that made regulators and customers miserable. It was an understandable move: trading offered the prospect of higher returns than regulated distribution ever could. But it also introduced a different kind of risk—one that didn’t always fit what utility investors expected when they bought the stock.

By the mid-2000s, Sempra was also formalizing its role in the communities it served. In 2007, it established the Sempra Energy Foundation as a 501(c)(3) private foundation, putting structure around charitable efforts in education, environmental stewardship, and community development. For a company whose economics are ultimately approved by regulators, this wasn’t just generosity—it was part of maintaining the social license to operate.

And the earliest threads of renewables began to show. California’s climate policies were tightening, and renewable portfolio standards were pushing utilities to buy more wind and solar. Sempra started developing projects of its own, signaling it intended to be part of the energy transition rather than simply comply with it.

By 2007, Sempra no longer fit neatly into the “California utility” box. It was a blend: regulated gas and electric operations at home, utility investments in Latin America, a trading and marketing arm exposed to competitive markets, and early renewable development. The strategy was broad—maybe too broad. But it was funded by something powerful: the steady cash flows of regulated California infrastructure, giving Sempra the ability to experiment with multiple paths to growth.

IV. The Infrastructure Pivot: LNG & Mexico (2008–2017)

In the mid-2000s, the natural gas story seemed straightforward: America was running out.

Domestic production from conventional fields was declining, and the consensus view was that the U.S. would become a long-term importer—pulling liquefied natural gas from places like Qatar, Algeria, and Nigeria to keep the lights on and the furnaces running. So companies did what the narrative demanded. They spent billions building LNG import terminals up and down the coasts.

Sempra bought into that future, too. In May 2008, its Energía Costa Azul facility in Baja California began commercial operations. Sitting on the Pacific coast about 30 miles south of the U.S. border, Costa Azul was built to receive LNG cargoes from around the world, regasify them, and push that gas into U.S. and Mexican markets. It was among the first LNG receipt terminals on North America’s West Coast—exactly the kind of strategic beachhead you’d want if the next era of American energy meant tankers arriving nonstop.

Then Sempra added a second gate to the system. In July 2009, Cameron LNG, near Lake Charles, Louisiana, completed performance testing and began commercial operations. The Gulf Coast location plugged directly into the country’s dense pipeline network, making it easy to move imported gas to wherever demand was highest. With Costa Azul in the west and Cameron in the Gulf, Sempra had built real scale in the LNG import business.

And then the script flipped.

The shale gas revolution didn’t merely improve U.S. supply—it rewrote the economics of natural gas. Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, refined in places like the Barnett Shale and then deployed across the Marcellus, Haynesville, Eagle Ford, and eventually the Permian, turned “scarcity” into “surplus.” Production surged. Prices fell. And by around 2010, it was becoming obvious: the U.S. wasn’t going to import LNG at scale after all.

That meant a brutal reality for the industry. Terminals designed for an import-heavy America suddenly looked like stranded assets—massive, expensive facilities built for a world that no longer existed.

But for Sempra, the same shift that broke the original thesis created an even bigger one. If America had abundant, low-cost gas—and overseas markets were willing to pay a premium for LNG—then the opportunity wasn’t bringing fuel in. It was sending it out.

This is where Sempra’s “infrastructure over everything” instinct paid off. Cameron LNG, built to receive shipments, could be converted to liquefy domestic gas for export. That wasn’t a simple switch. It required major new equipment and construction—liquefaction trains, expanded storage, and marine upgrades. But the logic was powerful: buy cheap U.S. gas, turn it into LNG, ship it to higher-priced markets, and earn the spread.

At the same time, Sempra was quietly expanding the other leg of what would become its North American infrastructure platform: Mexico. The country’s 2013 energy reform opened a door that had been locked for decades, inviting private investment into a sector long dominated by the state. For Sempra—already operating near the border and already thinking in terms of pipes and terminals—this was a natural extension. It began building pipelines, power plants, and related infrastructure to meet Mexico’s growing energy demand.

And even as natural gas and LNG took center stage, Sempra started placing early bets on renewables. In 2008, it completed its first renewable energy project: a 10-megawatt solar facility in Nevada. By later standards it was small, but strategically it mattered. The company was signaling that it didn’t want to be boxed into a single fuel. It wanted to own the infrastructure that would be needed regardless of what the grid ran on.

By 2017, the shape of the next Sempra was coming into focus. Commodity trading, once a tempting way to monetize volatility, was being exited or de-emphasized as management recognized it didn’t fit what utility investors signed up for. The South American utilities were still there, but they were no longer the center of gravity. The priority had shifted to North American infrastructure—regulated utilities as the cash-flow engine, and LNG and Mexico as the growth runway.

Which set up the next move: a Texas-sized acquisition that would change Sempra’s scale—and its identity—almost overnight.

V. The Oncor Acquisition: Texas-Sized Ambitions (2017–2018)

The bankruptcy of Energy Future Holdings was one of those corporate blowups that becomes shorthand—a case study in private equity ambition, too much leverage, and timing so bad it looks fictional in hindsight.

Back in 2007, a consortium led by KKR, TPG, and Goldman Sachs bought TXU Corporation, the dominant electric utility in Texas, for about $45 billion. At the time, it was the biggest leveraged buyout ever.

The bet hinged on one big assumption: natural gas prices would keep rising. If that happened, TXU’s large fleet of coal plants—cheap to run relative to gas-fired competitors—would look like a license to print money. High gas would set the market price of power. Coal would deliver power at a lower cost. The spread would do the rest.

Then shale happened.

As U.S. production surged, gas prices collapsed. TXU’s coal-heavy generation went from advantage to anchor, and the debt used to finance the deal stopped looking “aggressive” and started looking impossible. In 2014, Energy Future Holdings filed for Chapter 11—Texas’s largest bankruptcy and one of the biggest in U.S. history.

But inside that wreckage sat the crown jewel: Oncor.

Oncor wasn’t the risky part of TXU. It was the opposite. A regulated transmission and distribution utility—a pure “wires” business—paid to move electricity, no matter who generated it or what the market price was. It served about 3.4 million customers and ran a massive network of more than 140,000 miles of lines, making it the largest electric distribution utility in Texas.

Once the bankruptcy process made Oncor available, bidders swarmed. Hunt Consolidated, controlled by the family of oilman H.L. Hunt, went early. NextEra Energy, already a utility heavyweight, jumped in. And then the plot twist: Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway showed up, bringing the kind of regulatory credibility and patience few firms can match.

Sempra entered the race as the underdog. It was smaller than NextEra and didn’t have Berkshire’s halo. But CEO Jeffrey Martin and his team saw exactly what was on the table: a chance to turn Sempra from a mostly California story into a national utility platform—anchored in what might be the best growth market in regulated electricity.

Texas was booming. People were moving in fast, and the state’s retail electricity structure made the “wires” owner uniquely powerful. Retail providers could compete for customers, but they all depended on the same neutral delivery platform. Oncor earned regulated returns for building and maintaining that platform, while load growth and new development kept expanding the need for investment. For Sempra, it was the ideal profile: essential infrastructure, stable cash flows, and a long runway.

In August 2017, Sempra struck a deal to acquire Energy Future Holdings for about $9.45 billion in cash, securing an 80% stake in Oncor. The other 20% would remain with Texas Transmission Holdings, a consortium that included a state investment fund—an important detail in a state that cares deeply about local control of critical infrastructure.

Regulatory approval ended up being less dramatic than many expected. Sempra didn’t come in promising a remake. It promised continuity—minimal operational disruption, and a ring-fenced structure designed to protect Texas ratepayers from risks elsewhere in Sempra’s portfolio. On March 8, 2018, the Public Utility Commission of Texas approved the transaction.

When the deal closed, Sempra’s scale changed overnight. Combining Oncor with SDG&E and SoCalGas created a utility holding company with the largest customer base in the United States. The regulated asset base nearly doubled, giving Sempra a much larger foundation to invest into—and to grow earnings from—over the coming years.

And Sempra leaned in. In May 2019, Oncor acquired InfraREIT for $1.275 billion, expanding its transmission and distribution footprint. Around the same time, Sempra bought a 50% interest in Sharyland Utilities, tightening its grip on Texas as a core market.

Just as importantly, Oncor rewrote the narrative investors told about Sempra. Before, it looked like a California utility with a set of intriguing—but harder-to-value—LNG and infrastructure bets. After Oncor, Sempra could credibly say it owned essential, regulated infrastructure in two of the country’s biggest state economies. California and Texas don’t agree on much politically, but they share a reality that matters to utilities: huge populations, massive energy demand, and decades of grid investment still ahead.

VI. The LNG Revolution: From Importer to Exporter (2019–Present)

Cameron LNG’s journey—from an import terminal built for a world of U.S. gas scarcity to an export facility feeding the world—became one of the cleanest strategic pivots in modern energy. When the first export cargo left in May 2019, it wasn’t just a ribbon-cutting for Sempra. It was a marker in the larger American energy reversal. The United States, once assumed to be a long-term natural gas importer, was now shipping energy overseas at scale.

The export buildout at Cameron centered on three liquefaction trains, each designed to produce about 4.5 million tonnes per year. And Sempra didn’t do it alone. The project was structured as a joint venture with major global players including Total (now TotalEnergies), Mitsui & Co., and Japan LNG Investment. That structure mattered. Sempra brought U.S. infrastructure know-how and on-the-ground execution; its partners brought global marketing reach and the kind of long-term offtake commitments that make multi-billion-dollar LNG projects financeable. It was a model Sempra would lean on again.

The results were tangible. Since exports began in 2019, Cameron LNG shipped more than 840 cargoes to long-term customers across Asia and Europe. The Gulf Coast location is a huge part of the advantage: access to abundant U.S. gas supply, plus a deep-water channel at Lake Charles that can handle the enormous LNG carriers moving super-cooled gas across oceans.

But Cameron was more like proof-of-concept than endgame.

Sempra’s next bet was Port Arthur LNG on the Texas Gulf Coast, near the Louisiana border. Unlike Cameron—which had been built for imports and then rebuilt for exports—Port Arthur was designed from day one as an export facility. This was Sempra stepping into the LNG era as an intentional exporter, not a retrofitter.

And the scale reflected that confidence. Phase 1 reached final investment decision in March 2023: roughly $13 billion of total capital investment supported by $6.8 billion in non-recourse project financing. When completed, Phase 1 is set to add 13.5 million tonnes per year of liquefaction capacity—making it one of the largest LNG export developments in the industry.

Even more telling than the construction budget was the commercial setup. Port Arthur Phase 1 was fully subscribed under long-term offtake agreements before construction began. ConocoPhillips signed on. So did RWE in Germany, PKN ORLEN in Poland, INEOS in the UK, and ENGIE in France. It was a roster that made the takeaway obvious: this wasn’t a speculative “hope the market is there” project. The demand was already spoken for—and it was increasingly centered in Europe.

Then geopolitics poured gasoline on the trend.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022—and the subsequent squeeze on Europe’s energy supplies—turned LNG from a commodity into a strategic necessity. European countries that had relied on Russian pipeline gas for decades suddenly needed replacement molecules, fast. U.S. LNG became the most credible near-term answer.

For Sempra, this was the payoff for a kind of investing that’s almost boring until it’s not: permitting early, building patiently, and being ready before the world decides it urgently needs what you have. LNG terminals can’t be willed into existence in a crisis. The winners are usually the companies already in motion.

In June 2024, Sempra pushed the Port Arthur story into an even bigger register. Saudi Aramco signed a heads of agreement for 5 million tonnes per year of offtake from Port Arthur Phase 2, along with a 25% equity stake. It wasn’t just a customer agreement—it was a signal. The world’s most influential oil producer was effectively endorsing U.S. LNG export infrastructure as strategically important.

And Sempra’s ambition at Port Arthur wasn’t limited to liquefaction. The company’s broader Port Arthur Energy Hub vision included the potential to add carbon capture and sequestration, hydrogen production, and other lower-carbon technologies over time. The Gulf Coast is a natural canvas for that kind of buildout: dense pipeline networks, existing petrochemical and industrial infrastructure, and a workforce that already knows how to construct and operate complex energy facilities.

Economically, LNG doesn’t behave like a traditional utility. Utilities earn regulated returns—steady and predictable, but capped. LNG facilities, by contrast, are often built around long-term tolling-style contracts where customers pay for liquefaction services. Done right, you can get utility-like visibility with the potential for higher returns. The trade-off is where the risk concentrates: in construction and execution. Building multi-billion-dollar cryogenic facilities on schedule and on budget is unforgiving work.

Stepping back, Sempra’s rise in LNG reinforces a simple truth about infrastructure businesses: timing is everything, and timing is rarely obvious in the moment. Sempra invested in LNG import capacity when that narrative was dominant, pivoted when shale flipped the math, and then found itself positioned as global events made U.S. LNG indispensable. No one was forecasting an invasion of Ukraine when Cameron was being built. But luck tends to favor the companies that already did the hard, unglamorous work—securing sites, permits, contracts, and steel in the ground.

VII. Portfolio Optimization: Exits and Focus (2019–2021)

By 2019, Sempra had grown into something that looked, from a distance, like a classic energy conglomerate: regulated utilities in California, a fast-growing footprint in Texas, LNG and Mexico infrastructure on the rise, and—still hanging around—the South American utilities it had bought two decades earlier.

The question for management was unavoidable. Was Sempra going to be a diversified collection of assets, or a focused infrastructure platform with a clear center of gravity?

Latin America no longer matched the thesis. The company’s future was increasingly North American, built around regulated “wires and pipes” plus LNG terminals and related infrastructure. The South American utilities added complexity—different regulators, different politics, different currencies—and they didn’t reinforce the story Sempra was now telling.

So Sempra sold.

In 2020, it exited Peru by selling Luz del Sur for $3.59 billion to China Yangtze Power International. It also sold its Chilean businesses, including Chilquinta Energía, to China’s State Grid for $2.23 billion. Together, those two deals brought in nearly $6 billion and removed the day-to-day friction of running utilities in foreign jurisdictions far from Sempra’s operating base.

Just as important, the pricing worked. These were strong valuations, reflecting how aggressively Chinese state-owned enterprises were pursuing Latin American infrastructure at the time. And the timing helped: the transactions closed before the full economic fallout of COVID-19 and before rising U.S.-China tensions made cross-border dealmaking even more complicated. Sempra got out cleanly while the window was open.

The tightening didn’t stop with South America. Sempra also sold its U.S. renewable energy development portfolio and other non-core assets. On the surface, selling renewables in an era of booming wind and solar could look like swimming against the current. But the logic was straightforward: this had become a scale game. Utility-scale renewable development was getting more competitive, and Sempra didn’t have the kind of massive portfolio and specialized machine that leaders like NextEra had built. Rather than fight uphill, it chose to recycle capital into areas where it had structural advantages.

Then came the symbolic capstone. In June 2021, “Sempra Energy” rebranded to simply “Sempra.” It wasn’t just cosmetic. Dropping “Energy” was a signal that the company didn’t view itself as a traditional energy business—producing fuel or taking big commodity bets. It was planting its flag as an infrastructure owner: moving and storing energy, and earning returns by being essential.

Around the same time, Sempra formalized the framework that made the story easier to understand and easier to value: three platforms—Sempra California, Sempra Texas Utilities, and Sempra Infrastructure. Each had its own economics, growth drivers, and risk profile, and investors could analyze them separately without getting lost in a muddle of unrelated assets.

The strategy also created a cleaner capital playbook. Asset sale proceeds supported share repurchases, debt reduction, and reinvestment in the core platforms. The message was discipline over empire-building: sell what doesn’t fit, and concentrate the balance sheet where Sempra believes it can win.

By the end of this optimization stretch, Sempra had drawn a bright line around what it was—and what it wasn’t. Not a commodities trader. Not an international utility operator. Not a renewables developer trying to out-muscle specialists. It was a North American energy infrastructure company, anchored by regulated utility cash flows and scaled by long-term, contracted LNG and Mexico assets.

And with that focus in place, the modern Sempra story snaps into view.

VIII. The Modern Sempra: Three Pillars Strategy (2021–Today)

Walk into Sempra’s San Diego headquarters today and you’re not looking at the 1998 merger anymore. The old “utility-plus-a-bunch-of-stuff” profile has been sharpened into three clear platforms, each with its own job to do in the portfolio: California for stability, Texas for growth, and Infrastructure for global scale.

Start with Sempra California—the bedrock. Southern California Gas Company and San Diego Gas & Electric together serve roughly 25 million consumers across one of the largest utility footprints in the country. SoCalGas is the largest natural gas distribution utility in the United States by customers served, with more than 21 million people relying on its system for everything from home heating and cooking to industrial demand. SDG&E supplies electricity and natural gas to San Diego County and southern Orange County—an area with a mild climate, but some of the country’s most aggressive environmental targets.

In a regulated state like California, “growth” looks different than it does in a competitive market. It’s not about winning customers away from rivals. It’s about building what the state requires—and earning allowed returns on that investment. California’s climate policies demand enormous spending: modernizing the grid to handle distributed solar, hardening infrastructure to reduce wildfire risk, and integrating renewables to support the state’s target of 100% clean electricity by 2045. For a utility, those mandates can translate into years of approved capital spending that expands the rate base and drives steady earnings.

But that stability comes with California-sized risk. Wildfires have changed the rulebook for electric utilities. The Camp Fire in 2018 and the Dixie Fire in 2021 were only the most infamous examples of a broader pattern that has produced staggering liabilities across the industry. Pacific Gas & Electric went bankrupt in 2019 largely because of wildfire exposure. SDG&E operates in a different part of the state than PG&E, and it has invested heavily in wildfire mitigation, but the underlying uncertainty doesn’t disappear. California’s inverse condemnation doctrine can hold utilities strictly liable for damages caused by their equipment, even without negligence—an unusually tough legal framework that keeps risk permanently in the background.

Then there’s Sempra Texas Utilities, built around Oncor. This is the purest “wires” business in the portfolio: about 18,324 circuit miles of transmission lines, 1,288 substations, and roughly 4 million electric delivery points across a territory that includes the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex and much of Central and East Texas. Oncor doesn’t generate power and it doesn’t sell it. Retail providers like TXU Energy, Reliant, and dozens of others handle the customer relationship. Oncor’s job is simpler and more durable: deliver the electricity and earn regulated returns for keeping the system reliable.

Texas is where Sempra gets a different kind of tailwind. The state’s population growth and business migration mean new homes, new factories, and new commercial development that all need to be connected to the grid. Add in the surge in demand from cloud computing and artificial intelligence—especially data centers that consume power at industrial scale—and you get a steady drumbeat of load growth. For a wires company like Oncor, that turns into more grid investment, and more regulated earnings opportunity.

Finally, Sempra Infrastructure holds the assets that push the company beyond the traditional utility playbook: LNG and the Mexican energy platform. This segment carries a different risk-reward profile. Instead of regulated returns set by state commissions, LNG facilities typically earn revenue through long-term tolling-style contracts—customers effectively pay for access to liquefaction capacity, often for decades. That contract structure can create utility-like visibility, but it comes with very real development risk: permitting, financing, and the unforgiving work of building mega-projects on time and on budget.

By 2024, Sempra’s scale was showing up in the rankings—#246 on the Fortune 500 and #366 on the Forbes Global 2000—and in investor expectations, with a market capitalization above $90 billion. But the more important story is what those numbers represent: a company that’s become easier to understand, and arguably stronger, by narrowing its focus.

The three-pillar structure gives Sempra built-in diversification. California provides slow-and-steady regulated growth, with policy-driven investment needs. Texas adds faster growth tied to migration and economic expansion. Infrastructure delivers bigger, episodic leaps when projects come online and global gas markets pull demand forward. When one platform runs into turbulence—regulatory friction in California, weather-driven stress in Texas, or a softer LNG market—the others can help steady the overall ship.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Sempra’s rise—from a California utility merger to a North American infrastructure heavyweight—reads like a case study in capital allocation with a clear point of view. The first lesson is the simplest, and the most enduring: know what business you’re actually in. Early on, Sempra leaned into the idea that the real value in energy would increasingly sit in the infrastructure—the pipes, wires, and terminals—more than in the commodity itself. While plenty of peers chased generation assets or tried to manufacture profits in trading desks, Sempra kept building and buying the unsexy assets that stay necessary no matter what fuel wins or what market design comes next.

The utility roll-up is the second lesson: regulated returns can be more than “boring.” They can be rocket fuel—just delivered slowly and predictably. By expanding its base of regulated utility cash flows, Sempra built a balance-sheet engine that could fund larger swings. The California utilities produced the steady earnings that helped support LNG investments. And once those LNG assets came online, they offered something utilities rarely get: the potential for higher returns, but still anchored in long-term contracts. It’s a barbell strategy—stable regulated core on one end, contracted growth infrastructure on the other—that has become a blueprint for modern infrastructure companies.

The Oncor deal is lesson three: patient opportunism beats constant motion. Sempra didn’t manufacture the opening—Energy Future Holdings’ bankruptcy did that. But management recognized immediately that Oncor was a rare kind of prize: a large, regulated “wires” platform in a fast-growing state. They pursued it through a crowded, high-profile bidding process and were willing to pay a fair price for a premier asset instead of settling for something cheaper but weaker. It’s the old idea often attributed to Buffett: wonderful business, fair price—over fair business, wonderful price.

Then there’s the skill that doesn’t show up cleanly in spreadsheets but decides outcomes anyway: regulatory navigation. Sempra has to win in two very different arenas—California and Texas—each with its own politics, priorities, and regulatory instincts. Doing that well takes a kind of institutional discipline: showing up prepared, making credible commitments, and following through after approvals are granted. In regulated infrastructure, trust is an asset. Lose it, and the penalties can be severe enough to overwhelm years of operational progress.

Sempra’s LNG story adds a more uncomfortable lesson: sometimes “early” looks identical to “wrong,” until it doesn’t. The original LNG import terminals were built for an America that was expected to need overseas gas. Shale flipped that thesis on its head and made those investments look ill-timed. But the infrastructure, sites, and experience created the option to pivot—first at Cameron, then into a purpose-built export strategy at Port Arthur. If Sempra had waited until the export opportunity was obvious, it would have been late. And in LNG, “late” can mean missing an entire cycle.

Portfolio management is the next takeaway: knowing what to sell matters as much as knowing what to buy. Exiting South America simplified the company and crystallized value. Selling the U.S. renewables development portfolio was another act of clarity—an acknowledgment that it was becoming a scale game dominated by specialists. Sempra didn’t try to win every arena. It recycled capital toward the platforms where it believed it had structural advantage, especially LNG and North American infrastructure.

Finally, risk management: in capital-intensive infrastructure, the biggest risks are often execution risks. LNG projects are unforgiving—massive, complex builds where cryogenic systems, marine infrastructure, and pipeline connectivity all have to work perfectly together. Sempra consistently leaned on joint venture structures to share costs and risk with experienced partners, rather than trying to carry mega-project exposure alone. That’s not just financial engineering. It’s a recognition that even strong companies can get humbled by complexity—and that disciplined partnership can be a competitive advantage.

X. Analysis: Bull vs. Bear Case

The bull case for Sempra starts with a simple idea: it owns infrastructure that is hard to replicate in the places that matter. California and Texas are two of the most important regulated utility markets in the U.S., and LNG has become one of the most strategically important pieces of global energy supply. Oncor’s grid is the product of generations of buildout; trying to duplicate it would be economically irrational and politically dead on arrival. And LNG terminals don’t spring up overnight. They demand years of permitting, enormous capital, and deep relationships with customers willing to sign long-term contracts. In other words: these are real moats, not momentary advantages.

Next is what utility investors usually pay for: visibility. In both California and Texas, earnings are driven by allowed returns on approved investment. Put capital into the system, grow the rate base, earn the regulated return. It’s not flashy, but it’s unusually dependable. That stability has also supported shareholder returns over time, including a dividend that Sempra has raised annually for more than two decades—less a promise of future performance than a sign of how durable the core cash flows have been.

Then there’s LNG, which gives Sempra something most utilities don’t have: a path to global growth that isn’t capped by a state commission. Many major forecasters—including the International Energy Agency and the U.S. Energy Information Administration—expect natural gas demand to remain meaningful for decades, even in aggressive decarbonization scenarios. Gas plays a dual role: it can displace coal in many markets, and it can provide the flexibility that wind and solar can’t always deliver on their own. For countries trying to balance affordability, reliability, and security of supply, U.S. LNG has real appeal—large resource base, massive infrastructure buildout, and a relatively stable geopolitical backdrop compared with many alternatives.

In that light, the energy transition isn’t only a threat to Sempra; it can also be a demand driver. Electrification of transportation and buildings pushes electricity consumption higher, which benefits wires businesses like Oncor and SDG&E. Meanwhile, as renewables penetrate the grid, systems often lean on gas-fired generation for balancing and reliability—supporting the ongoing relevance of gas infrastructure. And there’s optionality embedded in SoCalGas’s network if hydrogen or renewable natural gas become more commercially and politically scalable over time.

The bear case is just as real—and in a few areas, it’s existential.

Start with California wildfire liability. A single catastrophic event tied to utility equipment can create billions in damages. Under California’s strict liability framework, that risk can attach even without negligence. SDG&E has invested heavily in mitigation—undergrounding, monitoring, and safety shutoffs—but the uncomfortable truth is that nothing reduces wildfire risk to zero. In California, the tail risk is always there.

LNG has its own version of cyclicality risk. A wave of global capacity is under construction, and by the late 2020s that additional supply could change market dynamics. Qatar is expanding. Australia remains a major supplier. Russia may add capacity to the extent sanctions and geopolitics allow. New projects are emerging in Africa. If supply outruns demand, prices and margins across the LNG value chain can compress, and infrastructure can lose some of its perceived scarcity value. Sempra reduces exposure with long-term contracts, but contracts are only as good as counterparties’ willingness and ability to perform.

Capital intensity is another constraint. Between Port Arthur, grid expansion in Texas, and ongoing investment needs in California, the company is committing to a multi-year cycle of very large spending. That means consistent access to capital markets matters. Higher interest rates raise financing costs and can also make utility dividends look less attractive relative to safer alternatives. Sempra’s investment-grade profile helps, but protecting that rating can also limit financial flexibility when the cycle gets choppy.

Finally, there’s the long-range transition risk to natural gas itself. If electrification moves faster than expected, if hydrogen economics improve dramatically, or if policy shifts hard against fossil fuels, then long-duration gas assets can face stranded-asset questions. Twenty- and thirty-year LNG contracts are valuable precisely because they’re long—but that also means they’re betting that customers will still want these molecules well into the future.

If you run Sempra through strategy frameworks, you see why the company can be so attractive—and where the limits are. Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers shows several durable advantages that fit infrastructure unusually well: scale economies in LNG, switching costs in regulated utilities, and “cornered” resources like rights-of-way and terminal sites that are effectively impossible to recreate. Some powers matter less here—branding and counter-positioning aren’t typically what decide outcomes in wires-and-pipes businesses.

Porter’s Five Forces lands in a similar place. New entrants are unlikely because the regulatory and capital barriers are enormous. In regulated utilities, buyer power is muted because customers don’t have real alternatives. In LNG, buyer power is sharper—large counterparties negotiate hard, and the market is global. Supplier power is meaningful because specialized engineering, equipment, and construction capability are concentrated among relatively few firms. Substitution risk varies: renewables can reduce gas demand over time, but they can also increase near-term demand for flexible backup.

For investors following Sempra, two operating indicators are especially worth watching. First is rate base growth in California and Texas, because that’s the engine of long-term earnings in the regulated businesses: invest, expand the rate base, earn the allowed return. Second is contracted LNG utilization, because these are capital-heavy assets that work best when the trains stay busy under long-term agreements. Persistent underutilization—whether from operational issues, customer problems, or shifting market conditions—would be an early warning sign that the infrastructure thesis is under stress.

XI. Epilogue: Looking Forward

Jeffrey Martin, Sempra’s CEO since 2018, has been consistent about where he thinks this all goes. In his view, the future of North American energy infrastructure isn’t defined by one fuel winning and another losing. It’s defined by three demands that never go away: security, affordability, and sustainability. The hard part is that the system has to deliver all three at once—a trilemma that now shapes almost every major energy decision.

Energy security, after years of feeling like a solved problem, is back at the center of the conversation. The war in Ukraine made the lesson painfully clear: energy supply can be weaponized, and long-term dependence can become a lever for geopolitical coercion. In that context, American LNG has turned into something more than a commodity. It’s a market-based alternative to Russian pipeline gas—supply that countries can buy without taking on political strings. Sempra’s LNG facilities sit directly in that equation, not as a talking point but as physical capacity that converts U.S. gas abundance into real-world optionality for allies overseas.

Affordability is the pressure that shows up closer to home. As electrification expands, households that once relied on a mix of fuels start leaning harder on electricity. Electric vehicles, heat pumps, and electric appliances don’t just change what people use—they increase how much they depend on the grid being reliable and reasonably priced. That puts utilities in a familiar bind: customers want lower bills, but the system needs massive investment to meet new demand and higher reliability expectations. California and Texas approach regulation in very different ways, but both ultimately face the same balancing act—protecting ratepayers while still enabling the buildout that keeps the lights on.

Sustainability is the third leg, and it’s only getting more urgent. California’s decarbonization mandates are among the most aggressive in the world, and hitting them requires a rebuild, not a tweak. More transmission to move renewable power from where it’s generated to where it’s used. Distribution systems that can handle two-way flows as rooftop solar and batteries become more common. And possibly, over time, gas systems that can carry different molecules—hydrogen or renewable natural gas—if those markets become real at scale. Sempra’s infrastructure could be a bridge in that transition, or it could end up on the wrong side of it. The direction is clear; the path is not.

The next frontiers are already on the horizon. Carbon capture and sequestration, if it becomes broadly viable, could change the conversation around gas infrastructure by capturing emissions and storing them underground. Hydrogen—especially green hydrogen made from renewable electricity—could create demand for adapted pipeline networks and new storage and handling systems. Sempra has positioned itself to participate as these technologies develop, but the company is operating in the same uncertainty as everyone else: timing, economics, and policy will determine what’s real, and what stays theoretical.

The throughline is that infrastructure doesn’t go out of style. However the transition unfolds, electrons still have to travel through wires. Molecules still have to move through pipes. And in a global market, energy still has to cross oceans on ships. The companies that build, operate, and adapt that connective tissue—reliably, safely, and with enough flexibility to evolve—tend to earn value that survives multiple energy paradigms.

That’s what Sempra has been betting on since 1998. It wagered that infrastructure would matter more than the commodity, that regulated returns could fund contracted growth, and that essential assets would compound through volatility. Nearly three decades later, the bet has worked. The open question is whether the same playbook can keep winning through the next era—an energy transformation that may end up being the biggest shift since society first wired itself for electricity in the first place.

XII. Recent Developments

Sempra’s most recent earnings updates have had a familiar theme: steady progress across all three pillars, with the biggest spotlight on the Gulf Coast. Port Arthur LNG Phase 1 has continued moving through construction, and the company has kept its expectation for first LNG around mid-decade. In parallel, the Aramco partnership tied to Phase 2 has kept advancing through commercial discussions toward what could eventually become a final investment decision. Back in California, the company’s utility rate cases have continued working their way through the regulatory process, shaping what level of infrastructure investment can be funded and how quickly.

In Texas, Oncor has been catching a tailwind that’s hard to miss: load growth. The surge isn’t just more people moving to the state—it’s the type of demand showing up on the grid. Data centers, industrial expansion, and other large electricity users have been scaling quickly, and ERCOT has projected demand growth at a pace Texas hasn’t seen in decades, driven by trends like cryptocurrency mining, artificial intelligence computing, and manufacturing reshoring. For Oncor, every major new connection is the same basic story in regulated-utility language: more system investment, more rate base, and more earnings power over time.

California, meanwhile, remains the market where the upside is paired with the most uncomfortable risk. Wildfire seasons have been less catastrophic than the stretch from 2017 through 2021, but the underlying exposure doesn’t go away in a warming, drying climate. SDG&E has continued building out its wildfire mitigation posture—more weather monitoring, expanded camera networks, and intensive vegetation management—all designed to reduce the odds that utility equipment becomes an ignition source. Even with those efforts, the company has maintained significant insurance and reserves for potential liability, acknowledging the simple truth of operating in California: you manage the risk, but you don’t eliminate it.

Over all of this hangs policy. The debates that matter to Sempra aren’t abstract—they’re the rulebook. Federal decisions on LNG export permitting, government support for hydrogen infrastructure, and California’s evolving regulatory posture toward natural gas utilities are all active questions. And for a company built on long-lived assets with long-lived contracts, small changes in the policy climate can shape the economics for years.

XIII. Links & Resources

Primary Sources: - Sempra annual reports and 10-K filings (SEC EDGAR) - Sempra investor presentations (Investor Relations site) - Public Utility Commission of Texas orders and filings - California Public Utilities Commission decisions and proceedings - Federal Energy Regulatory Commission orders and dockets

Historical Context: - Power Struggle: The Hundred-Year War over Electricity by Richard Rudolph and Scott Ridley - The Smartest Guys in the Room by Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind (background on the California energy crisis and Enron) - The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World by Daniel Yergin

Industry Analysis: - S&P Global Commodity Insights coverage of LNG markets and projects - Wood Mackenzie research on North American LNG - Edison Electric Institute reports on the U.S. utility industry - American Gas Association analysis of the natural gas sector

Regulatory Resources: - California Public Utilities Commission (cpuc.ca.gov) - Public Utility Commission of Texas (puc.texas.gov) - Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (ferc.gov)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music