Truist Financial: When Two Southern Banking Giants Became One

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

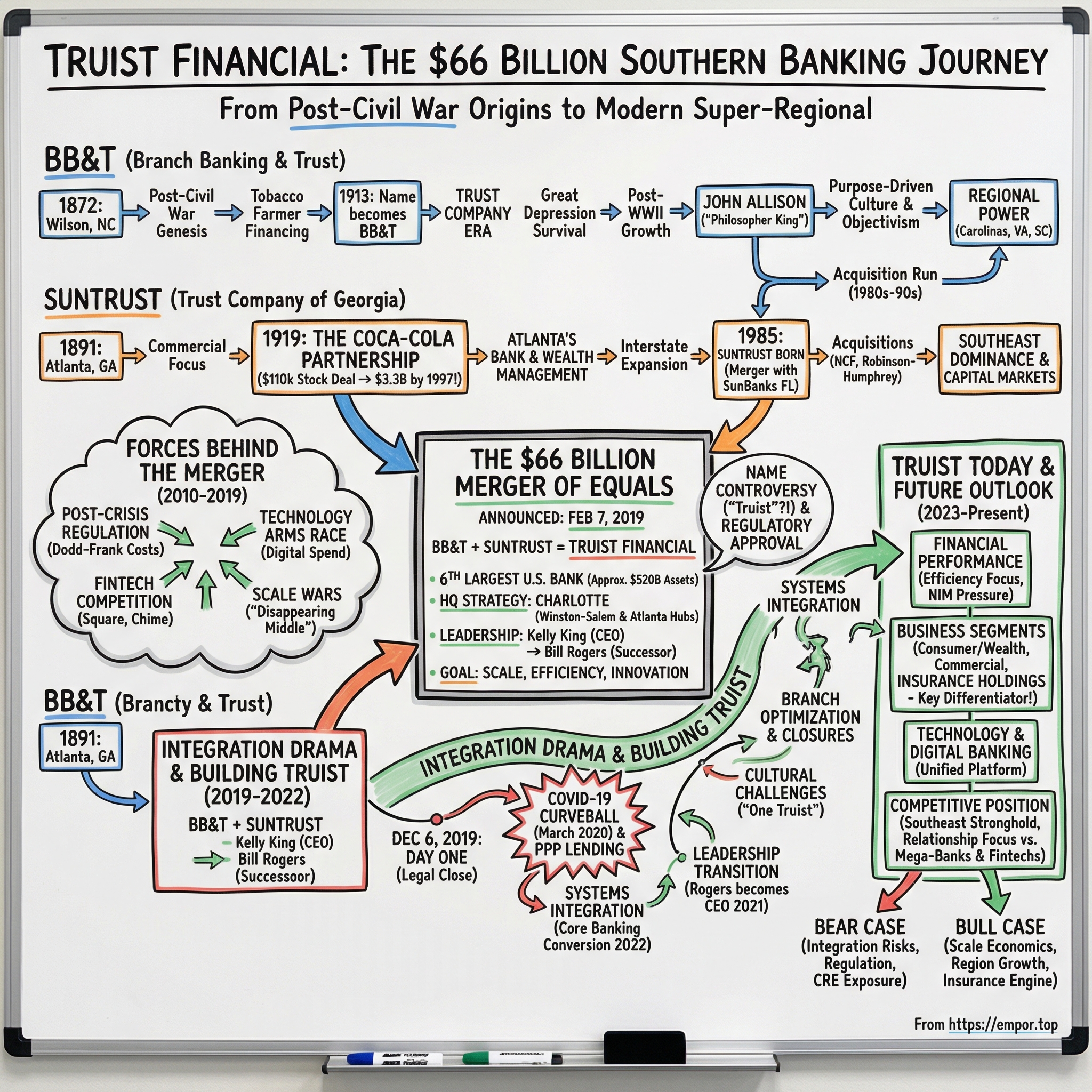

Picture this: February 7, 2019. Two of the South’s most storied banking franchises step up and announce they’re joining forces in a $66 billion merger of equals—the biggest U.S. bank deal since the 2008 financial crisis. On one side: BB&T, long anchored in Winston-Salem, with roots reaching back to Reconstruction-era North Carolina. On the other: SunTrust, Atlanta’s bank, famous for a corporate lineage intertwined with Coca-Cola. Put them together and you get Truist Financial: a new super-regional with more than $520 billion in assets.

But the question at the heart of this story isn’t “why get bigger?” It’s “how do you stay alive?”

Because modern banking is a scale game. The mega-banks—JPMorgan, Bank of America—can spread regulation, technology, and marketing over enormous balance sheets. Meanwhile, fintechs like Square and Chime don’t need branches at all, and they’re happy to chip away at the most valuable parts of retail banking. So what does a proud, century-plus-old regional bank do when the middle starts disappearing?

Then there’s the hard part that doesn’t show up in the press release. A merger of equals isn’t just arithmetic. It’s culture, power, identity—and thousands of decisions about who wins each “either/or.” Which systems survive? Which leaders stay? Which city gets to call itself headquarters? And how do you persuade customers—and employees—that this isn’t a takeover wearing a friendly mask?

This story runs from tobacco country in Wilson, North Carolina, to Atlanta’s financial towers. It includes Confederate veterans earning trust one farmer at a time, a legendary underwriting deal that helped put Coca-Cola on the map, and—eventually—a three-city tug-of-war over what “home” means. And the merger announcement was only the opening scene. What followed was a multi-year integration drama, made vastly harder by a global pandemic, high-stakes technology conversions, and the delicate task of inventing a brand from scratch and convincing the world it belonged.

What emerges is a modern banking case study: why scale has become existential, how regionals try to build defensible moats, and whether the “merger of equals” structure—so often promised, so rarely delivered—can actually work. By the time the dust largely settled in 2022, Truist had become the sixth-largest commercial bank in America, serving roughly 15 million clients across the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic. Getting there required navigating some of the toughest integration terrain any bank has faced.

So let’s rewind. To understand Truist, you have to understand the two institutions that made it—and the long, winding paths that brought them to the same table.

II. The BB&T Origins: From Reconstruction to Regional Power (1872–1995)

Post-Civil War Genesis

It’s 1872 in Wilson, North Carolina—a small town trying to rebuild after the Civil War, in an economy still shaped by the systems that came before it. Two men step into that moment and start a bank. Alpheus Branch and Thomas Jefferson Hadley had both grown up on family farms that relied on enslaved labor. Branch’s father, Samuel, owned 58 enslaved people; Hadley’s father owned 37. Both men served in the Confederate Army, then returned home and, like much of the region, tried to turn upheaval into a livelihood.

Their idea was straightforward: finance the people who kept eastern North Carolina running. Tobacco farmers needed credit to buy seed, cover payroll, and bridge the long gap between planting and getting paid. This was banking before algorithms—relationship banking in its purest form. You lent based on reputation, what you knew about the land, and whether you believed someone would make good on their word.

Fifteen years in, Branch bought out Hadley’s shares and renamed the firm Branch and Company, Bankers. But the playbook stayed the same. The bank grew up alongside the tobacco economy, syncing its fortunes to the seasonal rhythms of planting, harvesting, and selling—an early example of what would become BB&T’s long-running instinct: understand the local economy better than anyone else, and build from there.

The Trust Company Era

By the early 1900s, the business had outgrown its merchant-bank roots. In 1907, it launched a trust department—an important step up the financial ladder. Trust work meant estates, fiduciary duties, and long-term relationships with families and businesses. In 1913, the name caught up with the reality: Branch Banking and Trust Company. BB&T.

World War I brought an unlikely tailwind. Liberty Bonds turned banks into on-the-ground distribution networks for the federal government, and BB&T leaned in. Selling bonds wasn’t just a new line of revenue—it was customer acquisition, civic signaling, and brand building wrapped into one. People who might never have considered themselves “bank customers” suddenly had a reason to walk through the door.

In the 1920s, BB&T broadened the product set again, adding insurance and mortgage lending and opening four new banks across North Carolina. The institution was learning a core lesson of modern banking: once someone trusts you with their deposits, they’ll often trust you with everything else.

Then the Great Depression hit, and banking became a survival sport. In Wilson, every bank shut down—except BB&T. Led by President Herbert D. Bateman, BB&T not only stayed open, it expanded, adding six banks while others collapsed. By the end of the era, assets had climbed to $13.7 million. More than the number, the signal mattered: BB&T had earned a kind of institutional credibility that only comes from staying on your feet when the industry falls down around you.

Modern Banking Transformation

After World War II, BB&T grew steadily but quietly. By the 1970s, it still leaned heavily on agricultural lending—profitable, but exposed to commodity swings and the slow consolidation of small farms. It was a solid regional bank, but not yet a force.

The turning point came with John Allison. He wasn’t a typical banking executive. A philosophy major with an MBA from Duke, Allison approached management like a discipline to be examined, argued over, and systematized. What is a bank for? How should it balance shareholders, employees, customers, and communities? What does “good judgment” look like when you’re allocating capital?

That mindset earned him the nickname “The Philosopher King,” and he made BB&T culturally distinctive in a way few banks ever are. Influenced by Ayn Rand’s objectivist philosophy, Allison pushed ideas about rational decision-making, ethics, and performance into the company’s operating fabric. Employees weren’t just told what to do; they were expected to understand why the company believed what it believed.

To some, it was thoughtful and clarifying. To others, it was off-putting. Either way, it created cohesion—and it coincided with a major strategic shift. BB&T stopped acting like a bank content to sit still.

In 1981, it kicked off a serious acquisition run with the purchase of Independence National Bank in Gastonia, North Carolina. Through the mid-1980s, BB&T stitched together a statewide presence, with branches stretching from the mountains to the coast. Then it crossed the border: a merger with Greenville’s Community Bancorporation brought BB&T into South Carolina for the first time.

The capstone of the era arrived in 1995, when BB&T merged with Southern National Corporation, the fifth-largest bank in North Carolina. It was widely described as a “merger of equals”—language that would take on a familiar resonance years later. The combined company ended up with 437 branches across Virginia and the Carolinas. BB&T kept the name because it was better known, but the deal delivered something more valuable than branding: a bigger footprint, deeper talent, and a platform that could plausibly keep scaling.

By the mid-1990s, the old Wilson tobacco lender had become a multi-state regional bank with real ambition. The open question wasn’t whether BB&T could grow. It was whether its formula—disciplined deals, conservative underwriting, and a culture built on first principles—could keep working as the banking giants got bigger, faster, and harder to compete with.

III. The SunTrust Story: Atlanta's Bank and the Coca-Cola Connection (1891–2019)

The Trust Company of Georgia Foundation

While BB&T was stitching together the Carolinas, another Southern banking story was taking shape about three hundred miles southwest, in Atlanta. In 1891, the Georgia General Assembly chartered the Commercial Travelers' Savings Bank—born in a city still rebuilding from Sherman’s March, but already leaning hard into its commercial future.

The founders quickly decided “savings bank” didn’t capture what they wanted to become. Just two years later, in 1893, the institution renamed itself the Trust Company of Georgia and moved into what Atlantans proudly called the South’s first “skyscraper.” It wasn’t just a new address. It was a statement: Atlanta intended to be a real financial center, not just a railroad stop with ambition.

The trust company model mattered, too. It widened the playing field beyond deposits and loans into estates, trusts, and fiduciary work—the kinds of relationships that stick for decades and pull in the city’s growing class of business owners.

Then, in 1904, the bank found its defining early leader. Ernest Woodruff became president and immediately started playing offense. He was a consolidation-minded dealmaker with deep ties to Georgia’s business elite. Under Woodruff, Trust Company orchestrated mergers that cemented its position as Georgia’s leading financial institution.

But Woodruff’s most famous deal wasn’t a bank deal at all.

The Coca-Cola Partnership

In 1919, Woodruff led a group that bought The Coca-Cola Company from the Candler interests for $25 million—the largest business transaction in the Southeast at the time. The deal didn’t just change who owned Coca-Cola. It helped turn Coke from a regional success into a company ready for the public markets and global expansion.

For its underwriting work in taking Coca-Cola public, Trust Company received Coca-Cola shares valued at $110,000. On the surface, it looks like a footnote—a fee paid in stock.

In hindsight, it became one of the most consequential pieces of compensation in American banking history. By 1997, nearly eight decades later, that original block of stock had grown to $3.3 billion in value.

That kind of windfall doesn’t just boost a balance sheet. It shapes an identity. Trust Company became “the Coca-Cola bank,” with the prestige—and the pipeline of wealthy Atlanta clients—that came with it. If you were part of the city’s corporate establishment, odds were you either owned Coke or aspired to. And the bank most closely tied to Coke became the natural home for those relationships, especially in wealth management.

But the same connection created a long shadow. The bank’s portfolio was heavily concentrated in one stock. Selling large chunks risked major tax consequences and could complicate a relationship that had become synonymous with the institution itself. Coca-Cola was both the crown jewel and the constraint—an advantage that also narrowed strategic flexibility, right up until the Truist merger finally helped unwind that legacy.

Banking Evolution and Interstate Expansion

Like much of American banking, Trust Company rode the consolidation wave of the 1920s, absorbing smaller Georgia competitors. Then came the Depression. It survived, but the rules of the game changed.

The Banking Act of 1933—Glass-Steagall—forced the breakup of the financial conglomerate Trust Company had effectively become, leaving it as a wholly independent institution for the first time in more than a decade. Instead of treating that as a loss, management treated it as a reset: build a pure banking franchise and own the state.

By the mid-1930s, Trust Company had absorbed banks in Augusta, Columbus, Macon, Rome, and Savannah—five of Georgia’s largest cities outside Atlanta. The footprint wasn’t just Atlanta-centric anymore. It was statewide.

Then, in 1985, came the deal that created the name most people would later recognize. Trust Company merged with SunBanks Inc. of Florida, forming an interstate franchise stretching from Atlanta to Orlando. SunTrust was born—an intentionally upbeat name, built for a consumer-facing bank, and a signal that this was no longer a Georgia-only institution.

The SunTrust Era

Under the SunTrust banner, expansion became a habit. Acquisitions pushed the bank outward: Third National strengthened the Tennessee presence, and Crestar Financial opened the door to Virginia, Maryland, and the Washington, D.C. suburbs. Each transaction widened the map and brought in new teams and capabilities.

The biggest swing came in 2004, when SunTrust bought Memphis-based National Commerce Financial Corporation for $7 billion. NCF operated under different brand names across a swath of the South—South Carolina, Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, Georgia, Virginia, and West Virginia. The acquisition gave SunTrust entry into Alabama, the Carolinas, and West Virginia for the first time, while deepening positions in places where it was already competing.

SunTrust also pushed beyond plain-vanilla banking. Buying Robinson-Humphrey, a respected Atlanta investment bank, added underwriting, M&A advisory, and equity research. The company was becoming a broader financial services platform—still rooted in Southeastern consumer banking, still powered in part by that extraordinary Coca-Cola legacy.

By the late 2010s, SunTrust was Atlanta’s dominant bank and a major regional player. But the easy growth was gone. The obvious acquisition targets had largely been swallowed. The national giants were pressing harder into the Southeast. And technology spending was turning into a minimum requirement, not a competitive edge.

So SunTrust arrived at the question that was creeping across the entire regional banking industry: in a world where scale keeps getting more expensive, how do you get big enough to matter—without losing what made you worth trusting in the first place?

IV. The Forces Behind the Merger: Industry Consolidation and Scale Wars (2010–2019)

The Post-Financial Crisis Banking Landscape

The 2008 financial crisis didn’t just topple banks and trigger bailouts. It rewired the rules of American banking. And in the decade that followed, the pain wasn’t distributed evenly.

Dodd-Frank and the wave of post-crisis regulation that came with it landed hardest on the middle of the market. Small banks could lean on exemptions and simplicity. The mega-banks could afford armies of lawyers, compliance teams, and auditors. But mid-sized regionals were stuck in the worst spot: big enough to face the full weight of modern regulation, not big enough to spread those costs across a trillion-dollar platform.

At the same time, banking became a technology arms race. Customers started judging their bank the same way they judged any app: Does it work every time? Is it fast? Is it safe? A modern mobile experience, serious cybersecurity, and data infrastructure for personalization and fraud prevention became table stakes. And crucially, those investments don’t scale neatly. They cost roughly the same whether you’re a large regional bank or a money-center giant—meaning the biggest players could amortize the expense across far more revenue, year after year.

Then fintech arrived to make the squeeze even tighter. Square, Stripe, Chime, and SoFi didn’t need to build everything a bank builds. They could pick the most profitable slices—payments, consumer deposits, targeted lending—and attack with digital-first products and none of the legacy costs of sprawling branch networks. Regional banks felt pressure from both directions: the giants above them, the insurgents below them.

That’s how the industry ended up with what observers started calling “the disappearing middle.” If you were a bank somewhere in the super-regional range, the strategic message was getting louder: find scale—or become someone else’s scale.

BB&T's Position Pre-Merger

At BB&T, John Allison’s era had created a distinct culture and an acquisition-forward mindset. Kelly King inherited both when he became CEO, and he kept the machine running: disciplined deals, conservative underwriting, strong capital, and a steady expansion across the Southeast.

One advantage stood out. BB&T had built one of the largest insurance brokerage operations owned by an American bank. That mattered because insurance throws off fee income that doesn’t depend on interest rates. It also gives you more ways to deepen relationships—another product to sell to the same customer, another reason they stick around.

But the ceiling was getting harder to ignore. BB&T’s technology needed major investment to keep up with what customers and regulators now expected. Its footprint, while strong, was still heavily concentrated in the Carolinas and Virginia. And looming over everything was the same reality facing every regional: the national giants were pulling away on scale, brand, and the ability to outspend everyone on digital.

King had spent his career watching consolidation reshape banking. He understood what BB&T had always done well—and he also understood that the old playbook might not be enough for what came next.

SunTrust's Strategic Crossroads

SunTrust was staring at the same landscape from a different perch. Bill Rogers rose through the company over decades, including time running investment banking operations, and brought a capital markets lens to the CEO job. He knew the advantages of being a powerhouse in a major market like Atlanta. He also knew how quickly a regional franchise could get boxed in.

SunTrust’s dominance in Atlanta was real, but the growth paths were narrowing. Many of the obvious acquisition targets across the Southeast had already been bought. Moving into new regions would be expensive—and would throw SunTrust into fights with entrenched local competitors on their home turf.

Hovering in the background was the Coca-Cola position: enormously valuable, deeply symbolic, and not simple to unwind. It was a cushion most banks could only dream of. But it was also concentration risk, and any major move around it required careful handling given the relationship and the visibility.

Rogers pushed digital transformation because he could see where the puck was going. The problem was the same one BB&T faced: the spending was unavoidable, but the payoff wasn’t guaranteed—and shareholders still expected steady returns along the way.

SunTrust wasn’t failing. It was profitable, respected, and strategically aware. It just faced a brutal question: could it fund the next decade of banking on its own and still keep pace with competitors that were either far larger—or far lighter?

The Deal Takes Shape

By 2018, King and Rogers were talking. The conversations were reportedly built on mutual respect formed over years of crossing paths in the industry. More importantly, they were looking at the same scoreboard.

On paper, the logic was clear. Together, BB&T and SunTrust could create a super-regional neither could reach alone—bigger balance sheet, broader footprint, more resources for technology, and more relevance in a world where relevance was increasingly purchased.

But structure mattered as much as logic. The phrase “merger of equals” wasn’t window dressing; it was foundational. Neither side wanted to be seen as surrendering. Both had real strengths and real pride. Calling it an equals deal made the politics survivable and gave each organization a story to tell its employees, customers, and investors.

The geography helped. BB&T was strongest in the Carolinas and Virginia. SunTrust owned Georgia and had major presence in Florida. Overlap existed, but it wasn’t a head-on collision—meaning the merger could be pitched as expansion, not just consolidation and closures.

And then there was culture. On the surface, BB&T’s purpose-driven, almost academic internal identity could feel worlds apart from SunTrust’s Atlanta establishment heritage. Yet both banks shared something that mattered in banking: conservative credit instincts, relationship-based business models, and a deep commitment to community banking. The open question wasn’t whether they could agree on the PowerPoint version of that story. It was whether those similarities would hold when integration forced thousands of decisions that create winners and losers.

Because once you decide to merge, the theory is over. The real work is choosing what survives.

V. The $66 Billion Merger: Negotiations, Structure, and Announcement (2019)

The February 7, 2019 Announcement

When BB&T and SunTrust went public on February 7, 2019, it landed like a thunderclap across the industry. Winston-Salem’s BB&T and Atlanta’s SunTrust were joining in a merger of equals—creating what they billed as the eighth-largest U.S. bank, and the biggest bank deal since the 2008 financial crisis. The combined company would start life with roughly $440 billion in assets, about $300 billion in deposits, and close to 60,000 employees.

The initial reaction was a careful kind of optimism. On the whiteboard, the rationale was clean: more scale to fund technology and compliance, a footprint that fit together with limited overlap, and a big synergy target to make the math work.

But there was an asterisk the size of a skyscraper: merger of equals.

Banking had seen this movie before. “Equals” can look fair in a press release and still turn into a slow-motion power struggle once you get into the daily decisions that actually define a company. Which credit model wins. Which vendor stack survives. Which leaders get the real seats at the table. The market understood that the strategy might be right—and that the execution could still get ugly.

The $66 billion valuation baked in the classic merger promise: that the combined company could be run more efficiently than the two companies apart. Management projected $1.6 billion in annual cost savings by 2022, coming from the unglamorous but powerful levers of banking integration: consolidating branches, shrinking real estate, and rationalizing technology.

Deal Structure Deep Dive

This wasn’t a cash deal. It was stock-for-stock: SunTrust shareholders would receive 1.295 BB&T shares for every SunTrust share they owned. That ratio was meant to reflect the relative size and value of each franchise while keeping the “equals” framing intact—no obvious winner, no obvious loser.

Legally, BB&T was the survivor. The merged company would keep BB&T’s corporate structure and regulatory licenses, and it would initially carry BB&T’s stock history. In practice, that technical detail mattered far less than the real question everyone inside both banks was asking: when push comes to shove, which institution’s way of doing things becomes the default?

The leadership slate was designed to answer that question with symmetry. Kelly King would be CEO and chairman. Bill Rogers would be president and chief operating officer. And while nobody needed to say it out loud, the structure telegraphed a timeline: Rogers was positioned as the eventual successor. That handoff would, in fact, happen in 2021.

Governance followed the same blueprint. The board and senior management roles were balanced between the two legacies, an attempt to prevent the merger from quietly becoming an acquisition in slow motion. It was a deal built as much for internal legitimacy as for external logic—because in a merger like this, legitimacy is fuel.

The Name Controversy

Then, in June 2019, they stepped into the one part of the merger that would be visible to everyone: the name.

On June 12, BB&T and SunTrust announced the combined company would be called Truist Financial Corporation. And almost immediately, the response made it clear the announcement-day harmony had limits.

The process, at least on paper, was thorough. Interbrand was brought in. Employees were surveyed. Focus groups were run. The goal was a fresh identity that could belong to both banks, not a compromise logo that pleased nobody. “Truist” was meant to signal trust—the core currency of banking—wrapped in something that sounded modern and digital. It was also trademarkable, which matters more than most people realize until they try to name a national consumer brand in 2019.

But outside the research rooms, it didn’t “test.” It hit the public as strange, corporate, and vaguely synthetic. Analysts and customers asked the obvious question: why spend a century building two respected Southern banking names, only to replace them with something that sounded, to critics, like a startup—or a drug.

And the problems weren’t limited to opinion. Truliant Federal Credit Union, also based in Winston-Salem, filed a trademark infringement lawsuit, arguing the names were too close and could confuse customers. The claims were ultimately dismissed in August 2020, but the episode was a useful preview of what integration would be like: even decisions that look tidy in a conference room can create real friction in the real world.

Regulatory Approval Process

Of course, none of it mattered until regulators said yes.

A merger this large had to clear a long list of gatekeepers—the Federal Reserve, the FDIC, and state regulators among them. Final approvals came on November 19, 2019, roughly ten months after the announcement.

One key piece of the regulatory story was a Community Benefits Plan: a commitment to $60 billion of lending and investment in low- and moderate-income communities over three years. It was designed to address a predictable concern with consolidation—that communities most reliant on local branches and local credit can end up with fewer options after big banks combine.

There were also antitrust reviews. In a handful of markets where the combined bank would have too much concentration, branch divestitures were required. The overlap between BB&T and SunTrust was limited enough that this wasn’t a deal-breaker, but for the affected customers and employees, “relatively modest” still meant disruption.

By late 2019, the approvals were in. The closing was next. And while integration teams had been working in parallel—planning systems, org charts, and branding—the truth about bank mergers is that planning is the warm-up.

Once the deal closed, the clock would start on the part nobody can fully simulate: making two banks behave like one.

VI. Integration Drama: Building Truist in Real-Time (2019–2022)

December 6, 2019: Day One

At midnight on December 6, 2019, the merger officially closed. Truist Financial Corporation was born—legally, instantly. Operationally, not so fast.

For roughly 60,000 employees and millions of customers, “Day One” looked a lot like the day before. Clients still banked through their familiar BB&T or SunTrust branches, websites, mobile apps, financial advisors, and relationship managers. That wasn’t hesitation; it was the only sane way to do a merger of this size. In banking, you don’t flip the switch until you’re sure the lights stay on.

The first visible change was small, but it mattered: customers could use either legacy bank’s ATMs without out-of-network fees. It was a modest convenience, yet also a signal. The merger wasn’t supposed to be a spreadsheet exercise. Customers were supposed to feel benefits, too.

Behind the scenes, though, the real Truist was being built at full speed. Integration workstreams multiplied—core systems, risk, marketing, branches, HR, benefits, vendor contracts—each with deadlines, dependencies, and someone whose job was to keep it from slipping. The plan was straightforward to describe and brutal to execute: over the next two years, fuse two massive banking platforms into one so every customer could eventually log into the same Truist experience.

The COVID-19 Curveball

Then March 2020 hit.

Three months into integration, the COVID-19 pandemic slammed the economy and scrambled daily life. For a newly merged bank, it was the worst possible timing—and a very public test of whether this new institution could function under stress.

The immediate impact was operational. Branch plans had to be rethought because many customers still needed in-person banking. Teams that were supposed to be sitting together, hammering through conversion details, suddenly had to coordinate remotely—integrating systems and processes over video calls, with all the friction that implies.

And then came the Paycheck Protection Program. PPP asked banks to move huge volumes of small-business lending at high speed, under evolving rules, while their own teams were stretched thin. For Truist, it was both a strain and an opportunity: a chance to show that the combined bank could deliver when its communities needed it. Truist processed billions in PPP loans, helping thousands of small businesses across its footprint stay afloat.

But the merger timeline still took a hit. In April 2021, Truist said the core conversion to combine the branches would happen in early 2022—about a year later than originally planned. Customers and employees would live longer than expected in an in-between world: BB&T and SunTrust on the outside, Truist taking shape on the inside.

Headquarters and Geographic Strategy

Even before COVID, one issue carried the kind of symbolism that can quietly poison a merger: where is “home”?

Winston-Salem had BB&T’s history and identity. Atlanta had SunTrust’s gravity, the biggest metro in the footprint, and the cultural pull of being a corporate capital of the South. Neither city wanted to be told it was no longer the center of the story.

Truist’s answer was Charlotte, North Carolina—roughly between the two. Pragmatically, it made sense. Charlotte was already a banking hub, with Bank of America headquartered there and major Wells Fargo operations. The talent, infrastructure, and familiarity with large-bank life were already in place.

But the deal couldn’t be seen as stripping the legacy cities of relevance. So Truist kept meaningful anchors in both. Winston-Salem became the headquarters for community banking, preserving BB&T’s connection to its longtime home. Atlanta became the hub for wholesale and retail banking operations, reflecting SunTrust’s strengths and corporate banking heritage.

It was complicated by design. The three-city structure added coordination costs. But in a merger of equals, optics aren’t cosmetic—they’re structural. Geographic balance was part of how the new company kept both sides bought in.

Systems Integration and Technology

If the headquarters question was political, the technology question was existential.

Core banking systems are the plumbing of a bank: the engines that process transactions, track balances, manage accounts, and hold customer data. Converting them isn’t like migrating email. It’s mapping and validating mountains of data, testing every transaction path, retraining employees, and telling millions of customers what will change and when—without breaking trust along the way.

That’s why Truist kept operating under the BB&T and SunTrust names while integration continued. To outsiders, it could feel confusing—was Truist a real bank yet, or just a holding company with a new logo? But inside the building, it was the safest path. You don’t force everyone onto one platform until you’re certain it can handle everyone.

And the fear was rational. Banking conversions have a long history of going sideways in ways customers instantly feel: outages, missing transactions, account access problems. The consequences aren’t just angry calls. They’re headlines, regulatory scrutiny, and reputational damage that lingers long after the systems stabilize.

In 2022, Truist hit the final major milestone of the merger integration: the core banking system conversion. At last, the technology was unified, and customers could access a single Truist digital experience. What began as a February 2019 announcement didn’t become fully real for customers until three years later.

Cost Synergies and Branch Optimization

The merger’s financial logic depended on cost savings—real ones, not theoretical. Management projected $1.6 billion in net cost savings by the end of 2022. But synergies don’t arrive gently. You have to go get them.

The most visible lever was branches. Truist planned to close 800 branches by the first quarter of 2022—an acknowledgment of two realities at once: overlap in the combined footprint, and a customer base steadily moving toward digital. Office consolidation was also part of the plan, with a targeted reduction of 4.8 million square feet of space.

Those aren’t abstract efficiencies. They’re careers and routines and local institutions. Branch teams that had spent years serving the same communities were told their locations would shut down. Back-office groups in both legacy organizations lived with the constant uncertainty of whether their work—and their jobs—would exist after consolidation.

Truist tried to manage the human side with severance, reassignment, and outplacement support. But the core truth of integration remained unavoidable: building one bank out of two meant deciding what would disappear. And for thousands of people, the merger stopped being a strategy and became personal.

VII. Leadership Transition and Cultural Integration (2021–2023)

The CEO Succession

The succession plan baked into the merger didn’t drift. On September 5, 2021, Bill Rogers became CEO of Truist Financial Corporation. Kelly King shifted to executive chairman, setting up his eventual retirement.

By merger-of-equals standards, the handoff was almost suspiciously calm. These transitions often turn into proxy wars—who really runs the company, whose people get promoted, whose strategy wins. Instead, King and Rogers had spent the integration period working shoulder to shoulder, and the relationship they built made the change feel like a continuation, not a rupture. The board stayed closely involved, keeping the timeline intact even as the pandemic forced plenty of other plans to slip.

Rogers also represented a change in tone. King had been steeped in BB&T’s purpose-driven, philosophy-inflected leadership style. Rogers came across more like an operator: execution-minded, metrics-oriented, and focused on competitive positioning. And that shift matched where Truist was in its lifecycle. As the merger moved from “create the new thing” to “run the new thing,” the job called less for vision-setting and more for performance delivery.

Cultural Challenges

For all the spreadsheets and system conversions, the hardest part of merging two century-old banks was always going to be culture.

BB&T’s identity had been shaped for decades by John Allison’s philosophical framework: a clear values hierarchy, a strong sense of purpose, and an unusually explicit way of talking about how a bank should behave. SunTrust came from a different lineage—Atlanta establishment roots, the long Coca-Cola association, and a corporate relationship and capital-markets orientation that felt more traditional and, to some, more urbane.

The gap wasn’t unbridgeable. But it was real. BB&T employees worried their distinctive culture would get diluted into something generic. SunTrust employees worried their approach would get folded into a worldview that, at times, could feel overly ideological.

“One Truist” meant building something that didn’t read like either side’s corporate handbook with the logo swapped. Truist rolled out a new values framework meant to draw from both legacies while standing on its own. The company leaned heavily on the standard integration toolkit—training programs, town halls, internal communications—to reinforce purpose and expectations, and it used employee surveys to track how the cultural merge was landing.

Attrition, of course, came with the territory. Some people left because they couldn’t see themselves in the new identity. Others took the uncertainty as a cue to test the market. Keeping high performers—especially the customer-facing bankers who hold relationships together—became a constant leadership priority, because in a bank merger, losing the wrong people can cost more than any synergy ever saves.

Strategic Pivots Under Rogers

As integration moved toward completion, Rogers started to put his fingerprints on Truist’s direction.

First: a faster push to digital. The pandemic had accelerated customer willingness to bank through apps and websites, and Truist leaned into that shift. Technology spending and digital product development ramped up, and the story the bank told the market increasingly emphasized capabilities and convenience, not just branches and footprint.

Second: more weight on capital markets and investment banking. Rogers’ background made him a believer in fee-based businesses as a way to differentiate and reduce reliance on interest-rate spreads. The platform SunTrust had assembled over time, including through acquisitions like Robinson-Humphrey, became more central to Truist’s broader narrative.

Third: continued focus on insurance. Largely inherited from BB&T, the insurance division had long been a differentiator—recurring fee income, stickier client relationships, and a business line that’s hard for competitors to copy quickly. Under Rogers, it remained a strategic asset, not a side business.

VIII. Truist Today: Performance, Strategy, and Market Position (2023–Present)

Financial Performance Analysis

Judging Truist after the merger means filtering out a lot of static. The early years were full of one-time integration expenses, restructuring charges, and balance sheet cleanups that made the numbers look choppy and made clean year-over-year comparisons misleading.

By 2024 and into 2025, the picture sharpened. Most of the big synergy goals were largely in the rearview mirror, and the cost takeouts started showing up more clearly in efficiency. Return on equity improved from the trough of the integration period, even if it still didn’t match the levels posted by the biggest national banks. And credit quality held up, reflecting the conservative underwriting instincts both BB&T and SunTrust brought into the combination.

Interest rates became another major storyline. As the Federal Reserve raised rates, net interest margin—the spread between what a bank earns on loans and pays on deposits—moved to center stage. Regionals with strong deposit franchises often benefit at first because loan yields can reset faster than deposit costs. Truist’s large retail deposit base helped, but it didn’t make the bank immune. Competition for deposits intensified as customers got more rate-sensitive and banks fought harder to keep funding cheap.

In the market, Truist’s stock performance versus peers told a similar two-part story. The initial post-merger stretch was weighed down by integration risk and the expense of getting to “one bank.” As the conversion work wrapped and metrics stabilized, the stock regained some ground—but it continued to trade with the broader regional bank narrative, including the 2023 industry stress that followed the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

Business Segment Deep Dive

Truist runs as three businesses under one roof, and each one plays a different role in how the bank competes.

Consumer Banking and Wealth is the engine room: branches, digital channels, deposits, and households. It supplies the funding that supports the rest of the company and generates fee income through investment services, credit cards, and mortgages. The fight here is constant—national banks with massive brand budgets on one side, fintechs with narrower, lower-cost products on the other.

Corporate and Commercial Banking is the relationship business at scale. It serves larger companies with lending, treasury management, and capital markets products. This is where continuity matters: corporate clients value bankers who understand their industries and can deliver more than a transaction. The merger expanded Truist’s reach, creating more opportunities to follow clients across a broader geography and offer a fuller menu than either BB&T or SunTrust could on their own.

Insurance Holdings is the differentiator. Largely rooted in BB&T’s long-standing emphasis on insurance distribution, this business brings in fee income that doesn’t hinge on interest-rate spreads. It’s diversification, and in banking, diversification is valuable.

That strategy showed up in a notable deal: Truist Insurance Holdings announced a $3.4 billion purchase of BankDirect Capital Finance from Texas Capital Bancshares. It was the largest acquisition for the old BB&T lineage outside of the Truist merger itself. Truist said the deal would effectively double its premium finance business, add life insurance capabilities, and expand its West Coast presence. Management projected that, once completed, the acquisition would make Truist Insurance Holdings the number two premium finance player in the market.

Technology and Digital Banking

Truist’s technology story is inseparable from its merger story. The 2022 core conversion made it possible to consolidate the customer experience, including bringing everyone onto a unified mobile platform. As with almost any major digital change, the initial reaction was mixed—platform migrations create friction, and customers notice it immediately. Over time, satisfaction improved as users adapted and the bank refined the experience based on feedback.

The scale question still hangs over everything. Truist’s technology spend runs into the billions each year—competitive for a regional bank, but still well below what the mega-banks can deploy. To close that gap, Truist has leaned on a hybrid model: build some capabilities internally, partner for others, and use innovation labs and accelerator programs to stay close to emerging tools without having to invent everything from scratch.

For investors, the issue is simple to ask and hard to answer: are Truist’s technology investments enough to keep pace in a world where customers compare their bank not to the branch down the street, but to the best app on their phone? Progress has been real—but the bar keeps moving.

Competitive Position

By this point, Truist had become the sixth-largest U.S. commercial bank, serving about 15 million clients primarily across the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic. That concentration is both the advantage and the constraint.

The advantage is the region itself. Many of Truist’s core markets have enjoyed strong population growth, business formation, and economic momentum relative to national averages. And Truist isn’t new to these communities—it has decades of relationships, local knowledge, and institutional presence built by both legacy banks. Those ties create real switching costs that aren’t easily replicated by a newcomer.

The constraint is what Truist is not. It isn’t a coast-to-coast branch network like JPMorgan Chase or Bank of America. It doesn’t have the same kind of global investment banking footprint as Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley. Winning the biggest corporate relationships against those players requires either unusually deep local expertise, specialized capabilities, or both.

So Truist has leaned into a clear identity: a relationship-focused alternative to the money-center giants, with a promise of more personal service and more local decision-making than the national banks can reliably deliver. Whether that positioning holds as technology keeps standardizing more of what banking looks like—and as customer loyalty becomes easier to test with a few taps—is still one of the open questions at the center of Truist’s next chapter.

IX. Playbook: Lessons from the Mega-Merger

Merger of Equals: Theory vs. Reality

“Merger of equals” is one of those phrases that sounds fair, orderly, even elegant—until you try to live inside it. Companies attempt it all the time. They pull it off, end-to-end, far less often. The BB&T–SunTrust combination is useful precisely because it shows both what the structure can enable and where reality inevitably leaks in.

In theory, an equals deal lets two franchises combine without the emotional and political baggage of a takeover. Both cultures get a voice. Both leadership teams share power. Both shareholder groups participate in the upside. And ideally, the combined company ends up stronger than either bank could have become alone.

In practice, “equal” has an expiration date. Disagreements still happen, and someone still has to decide. When two teams bring different habits—credit, tech, incentives, talent—one approach eventually becomes the default. The early symmetry of the merger agreement, with carefully balanced board seats and titles, gives way to something more organic: influence flowing to whoever delivers, whoever has the stronger internal coalition, and whoever is best positioned for the moment the company is in.

Truist managed that transition more smoothly than many expected. The CEO handoff from Kelly King to Bill Rogers happened on schedule. The three-city footprint—Charlotte as headquarters, with major roles for Winston-Salem and Atlanta—held together despite the inevitable friction. And while cultural integration was real work, it didn’t devolve into the kind of open factional warfare that can make an “equals” deal quietly fail even if the numbers look fine.

Why did it hold? A few things helped. The geographic fit reduced the number of zero-sum decisions. King and Rogers had a relationship that made collaboration feel modeled from the top, not merely requested. And the external pressures—technology spending, regulatory expectations, and then a pandemic—kept everyone focused on the same uncomfortable truth: the real competition wasn’t inside the merger. It was outside it.

Integration Best Practices and Pitfalls

Zoom out, and Truist’s integration leaves a handful of lessons that travel well.

First: cultural due diligence isn’t a soft add-on—it’s core. BB&T and SunTrust weren’t identical, but they weren’t opposites either. Both were conservative lenders. Both were relationship-driven. Both were rooted in the Southeast, with community banking as a real identity, not a tagline. That overlap gave the integration a foundation many “strategically brilliant” deals simply don’t have.

Second: technology choices shape everything downstream. Core systems, digital platforms, and data architecture aren’t just IT decisions; they become the operating constraints of the entire company. Once you commit, reversing course is punishing. The Truist timeline made that visible: the bank stayed in a two-brand, two-system reality for years because forcing conversion before it was ready would have been far riskier than running in parallel.

Third: communication is a form of risk management. Integration creates uncertainty for employees, customers, and local communities all at once. Clear, consistent updates—what’s changing, what isn’t, and when—don’t eliminate anxiety, but they reduce rumors, attrition, and customer drift. Many integrations break down first in trust, long before they break down in spreadsheets.

Fourth: no integration plan survives contact with the world. COVID-19 delayed Truist’s conversion by about a year and forced the company to operate in “in-between” mode far longer than intended. The skill wasn’t sticking stubbornly to the original schedule; it was adapting—shifting resources to urgent needs, stretching timelines where necessary, and still keeping the core integration moving.

Scale Economics in Modern Banking

At its heart, the Truist merger was a bet on scale economics. And the post-merger reality largely validated why that bet felt necessary.

Technology has a minimum spend now. A competitive mobile experience, modern fraud prevention, and serious cybersecurity aren’t optional. Regulation has a minimum spend too. Meeting post-crisis expectations requires systems, people, and process—costs that are far easier to absorb when spread across a larger platform. Even branding and customer acquisition have scale dynamics: getting attention in a fragmented world takes budgets that smaller banks struggle to justify.

But size isn’t free. Bigger organizations can get slower and more bureaucratic. Decision-making can drift upward. And the relationship banking that built both BB&T and SunTrust can be harder to preserve when the institution feels more like a machine than a local partner.

That leaves the real question Truist was created to answer: is it safer to endure the complexity of being larger, or to risk being “too small” in a world where banking keeps getting more expensive to run? The architects of the deal believed subscale was the bigger danger. Time—and the next full economic cycle—will ultimately grade that call.

The Insurance Diversification Strategy

If Truist has a strategic trait that’s genuinely distinctive, it’s insurance.

Most banks have some insurance activity around the edges. Truist inherited something far more substantial from BB&T: a scaled insurance brokerage and premium finance business that throws off meaningful fee income outside traditional banking.

The appeal is straightforward. Insurance commissions and premium finance income don’t rely on the same interest-rate spreads that drive banking profitability. They can be more stable through cycles. They deepen relationships with business owners. And they’re difficult to replicate quickly—an insurance distribution network is built over years, through relationships and acquisitions.

The BankDirect Capital Finance acquisition underscored that this wasn’t being treated as a side business. Truist put real capital behind the idea, framing it as a growth platform, not just a legacy asset to harvest.

The catch is that “synergy” doesn’t manage itself. Insurance and banking are different businesses with different sales models, cultures, and regulatory demands. Running both well under one roof is harder than running either alone. Truist’s early results in insurance have supported the strategy, but keeping it a true differentiator will require sustained focus—not just deal-making.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case: Truist's Future

Bull Case

The bull case for Truist is, at its core, the bet the merger was designed to make: that the modern banking game has a minimum viable scale, and Truist cleared it.

First, scale is no longer theoretical. BB&T and SunTrust didn’t just get bigger for bragging rights; they created a platform large enough to fund the unglamorous necessities of modern banking—technology, cybersecurity, compliance, and brand—without those fixed costs crushing returns the way they can at smaller regionals.

Second, Truist is anchored in a part of the country that’s been compounding advantages for years. The Southeast and broader Sun Belt continue to attract people, businesses, and capital. Truist doesn’t have to “enter” those markets; it’s already there, with dense coverage and long-standing relationships that can turn regional growth into deposits, lending, and wealth and insurance clients.

Third, insurance remains the most distinctive asset in the story. Fee income that isn’t tied to interest-rate cycles is valuable in any environment, and Truist has a real platform here—premium finance and brokerage capabilities that most banks simply don’t have at comparable scale. The BankDirect acquisition wasn’t just additive; it was a signal that Truist intends to keep leaning into that advantage.

Fourth, technology is shifting from a cost sink to a potential lever. After years of integration work, the core systems are unified and the digital platform is finally one experience. That doesn’t guarantee differentiation—nothing in banking does—but it does mean Truist can spend more time improving products and less time stitching two legacy worlds together.

Finally, a strong capital position gives Truist options. It can play offense when opportunities show up—through acquisitions, share repurchases, or simply investing harder in organic growth—rather than being forced into a defensive crouch when the cycle turns.

Bear Case

The bear case starts with the uncomfortable truth about big mergers: “done” is a legal milestone, not an operational feeling.

Yes, the core conversion is complete. But integration risk doesn’t vanish on conversion weekend. Culture takes longer, and so do the second- and third-order effects: key employees deciding they’re ready to leave, customers quietly moving accounts after one annoyance too many, and process issues that only emerge when the combined bank runs at full speed for a few years.

Then there’s the shifting regulatory environment. The 2023 banking stress episode refocused attention on mid-sized institutions, and the direction of travel has been toward more scrutiny, not less. If capital requirements rise or supervisory expectations tighten, banks like Truist can feel it more acutely than the biggest players who already run with heavy compliance infrastructure.

Commercial real estate is another overhang. Office markets, in particular, have been forced to reprice around post-pandemic work patterns, and that adjustment can surface credit issues even in portfolios that were originally underwritten conservatively. Truist’s exposure doesn’t have to be catastrophic to matter; it just needs to be large enough to keep investors nervous and management cautious.

Competition also isn’t getting easier. The mega-banks can outspend almost anyone on technology and marketing. Fintechs and nonbank platforms can cherry-pick high-value products. Truist sits in the middle—big, but not biggest—which can be a precarious place if differentiation isn’t sharp and consistently executed.

And finally, the Truist identity itself is still settling. Building a new brand on top of two century-old institutions is slow work. Trust, in banking, is earned over years and lost in days—and a brand that doesn’t yet feel “native” to customers can make that trust easier to test.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Porter’s framework helps explain why Truist’s future is so tightly linked to structural forces that no single management team can fully control.

Threat of new entrants is moderate, but it’s not static. A full-service bank charter is still hard to obtain and expensive to operate. But fintechs don’t need to become banks to compete with banks. They can attack specific profit pools—payments, consumer deposits, lending, investing—without carrying a full branch network or legacy cost structure.

Bargaining power of customers is rising. Digital account opening, faster transfers, and constant rate transparency have made it easier to shop around. Deposits, once “sticky,” have become more price-sensitive, and lending relationships that used to feel locked in are easier to contest.

Bargaining power of suppliers is relatively limited. A bank’s “suppliers” are largely depositors and capital markets funding. Neither behaves like a single concentrated vendor with outsized negotiating power, though funding can become more expensive quickly when market sentiment turns.

Threat of substitutes keeps growing. Customers can unbundle their financial lives: a payments app here, a brokerage account there, a specialized lender for one product, a different provider for savings yield. The traditional model of one primary bank owning most of a household’s financial life is harder to sustain.

Competitive rivalry is intense. The products are largely commoditized—deposits, loans, payments—and many competitors are well-capitalized and fighting for the same customers in the same high-growth markets.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Helmer’s lens makes the takeaway even sharper: Truist has real strengths, but most of the classic “moat” powers are limited in banking.

Scale Economies are meaningful in technology and compliance, but less so in day-to-day customer acquisition and relationship management. Truist is big enough to gain some advantage, but still smaller than the money-center banks that set the spending ceiling.

Network Effects are minimal. Banking isn’t like a social network or a payments rail where every new user makes the product better for the next user.

Counter-Positioning exists, but it’s fragile. Truist can credibly position itself as more relationship-driven than the mega-banks, but technology is making “personalized service” easier to deliver at scale, which erodes the uniqueness of that claim over time.

Switching Costs are real but declining. Direct deposits, autopay, and bill-pay create friction, yet the practical steps to move are simpler than they used to be—and customers are increasingly willing to do it for a better digital experience or a better rate.

Brand is still under construction. Truist is not BB&T or SunTrust, and the goodwill from those legacy names doesn’t automatically transfer. Brand building is possible, but it takes repetition and consistency—and it’s hard to accelerate without missteps.

Cornered Resource is where Truist looks strongest. The insurance brokerage and premium finance platform is difficult to replicate quickly and provides a differentiated stream of fee income that’s meaningfully outside standard spread banking.

Process Power could become real if the merger produces repeatable operating advantages—how Truist integrates, cross-sells, manages risk, and serves clients. But process power is earned over time, and it only shows up when execution stays disciplined for long enough that it becomes a habit competitors can’t easily copy.

Key Performance Indicators

If you want a quick, ongoing read on whether Truist is turning merger logic into durable performance, two metrics are especially telling.

Efficiency Ratio captures how much it costs the bank to generate its revenue. It’s the cleanest window into whether the cost synergies and operating discipline are actually showing up in the P&L, not just in integration decks. The direction matters at least as much as the absolute number: is the machine getting more efficient as the “one bank” model matures?

Net Interest Margin is the other heartbeat. It reflects not just the rate environment, but the quality of the deposit franchise and the discipline of pricing loans. For Truist, with a large retail deposit base, the hope is that funding is more stable than at banks that rely heavily on wholesale markets. But in a world where deposit competition can heat up fast, NIM becomes a real-time test of how defensible that advantage is.

Track those two over time, next to peer banks—not just quarter to quarter, but across a full cycle—and you’ll get a clearer answer to the big question Truist was built to answer: did scale make the franchise stronger, or just more complicated?

XI. Recent News

The latest developments at Truist have been less about splashy announcements and more about the unglamorous work of running the machine: finishing what the merger started, tightening performance, and placing a few very intentional bets on where banking profits will come from next.

Across quarterly earnings reports through late 2025, management pointed to steady progress on efficiency, returning again to the cost-synergy commitments that framed the deal from the beginning. Credit quality largely held up, but Truist also acknowledged what the entire industry has been watching: rising provisions tied to the possibility of commercial real estate stress.

On the insurance front, the BankDirect Capital Finance acquisition closed, and Truist said integration was moving on schedule. The pitch stayed consistent with why they did the deal in the first place—effectively doubling premium finance capabilities and widening geographic reach—and Truist positioned it as a clear signal that Insurance Holdings isn’t just diversification, it’s a growth engine.

Leadership-wise, the post-succession chapter has been notably steady. Since Bill Rogers took over, the tone has been execution over empire-building, with the executive team emphasizing organic performance rather than lining up another transformative transaction. At the board level, change has been incremental as some merger-era directors reached retirement age.

Meanwhile, the regulatory backdrop kept shifting. Proposed capital rules tied to Basel III implementation raised the prospect that regional banks could be required to hold more capital—something that can pressure returns or narrow the room to grow. Truist, like its peers, stayed active in the comment process as the industry tried to shape how those rules would land.

And, unsurprisingly, the technology meter kept running. Truist continued to invest in its digital customer experience and cybersecurity, and it also pointed to fintech partnerships as a way to move faster in specific product areas—an acknowledgment that in modern banking, speed and security are no longer separate projects.

XII. Links and Resources

SEC Filings and Investor Materials

- Truist Financial Corporation Annual Reports (Form 10-K)

- Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q)

- Proxy statements and investor presentations, available through the SEC’s EDGAR database

- The 2019 merger proxy statement, which lays out deal terms, integration plans, and the promised synergy math

Historical Resources

- BB&T corporate archives tracing the institution’s evolution from 1872

- SunTrust historical materials, including documentation tied to the Coca-Cola underwriting history

- North Carolina and Georgia banking regulatory records and historical references

Industry Analysis

- Federal Reserve reporting on regional bank consolidation and competitive dynamics

- FDIC research on how branch networks have changed—and what digital adoption has replaced

- Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond research on economic growth patterns in the Southeast

Integration Case Studies

- Academic case studies on bank “mergers of equals,” including work published by Harvard Business School and the Darden School of Business

- Post-merger integration analyses covering common pitfalls, best practices, and what tends to break under real-world pressure

- Consulting-firm perspectives on technology integration in financial services

Technology and Innovation

- American Bankers Association research on digital banking and customer behavior

- Fintech landscape analysis from CB Insights and PitchBook

- Industry benchmarks on bank technology spending from major research firms

Regional Economic Studies

- Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta research on Southeast economic dynamics

- Charlotte Chamber economic development reports

- State banking commission reports from North Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia

Leadership Perspectives

- Published interviews with Kelly King and Bill Rogers on the merger’s strategy and execution

- Industry conference remarks on Truist’s integration approach

- Truist corporate communications on culture, values, and the “One Truist” operating model

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music